Chapter 4: To the Middle East

The tradition that Britain should maintain a naval supremacy in the Mediterranean so as to augment her power in Europe and protect her trade routes to Asia and beyond was established at the Battle of the Nile, though its origins lay farther back. The construction of the Suez Canal provided an additional reason for preserving that supremacy. In pursuit of it she occupied Egypt, Palestine, Cyprus and Malta, piped oil from Iraq to Haifa, cultivated a strong influence in the Arab world, and opposed whatever nation, whether Turkey, France, Russia or Italy, threatened to become master of the eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. In 1939 as in 1914 it was evident that Britain should endeavour to maintain the shorter and more economical sea route to the East, and even if German and Italian aircraft compelled her partly to abandon this route (and her leaders were convinced that she would have to divert much shipping via the Cape if Italy entered the war), she yet must try to prevent the European enemies from by-passing her naval power and marching into Asia and Africa.

The British leaders recognised that if Britain’s military resources were preoccupied in a conflict with Germany, Italy might seize the opportunity to extend her influence in Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. So long as France was at Britain’s side, with a fleet equal to Italy’s and with armies in North Africa and Syria, the security of the Mediterranean demanded no great subtraction of power from the principal tasks – the blockade of the German Navy, the protection of the Atlantic routes, and the reinforcement of the French Army. By increasing the contingent of Indian troops in Egypt and by using Egypt and Palestine as training camps for Australian and New Zealand formations on their way to the French front, Britain could insure against Italian entry into the war without robbing the main theatre.

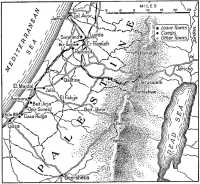

In order to give the military command in the Middle East a structure that would the better enable it to cope with large-scale operations, the British Government, in August 1939, had appointed General Sir Archibald Wavell1 to control all its military forces in Egypt, Palestine and Transjordan, the Sudan and Cyprus. Hitherto there had been independent commanders of the British garrison in Palestine (Lieut-General Barker2), in Egypt (Lieut-General Maitland Wilson3), and in the Sudan (Major-

General Platt4). These became subordinate to Wavell, whose responsibilities ran parallel to those of the Naval Commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean (Vice-Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham5) and the Air Commander-in-chief (Air Marshal Sir William Mitchell6). A British Dominion force, for example, arriving in the Middle East, would be commanded not directly by Wavell but by the commander of the area to which it was allotted.

–:–

The advance party of the Australian force had reached Egypt a few days before the convoy carrying the 16th Brigade sailed from Sydney. Brigadier Morris and Colonel Vasey travelled to Cairo and conferred with General Wavell and the British Ambassador, Sir Miles Lampson,7 and thence went on to Jerusalem where General Barker outlined his plan for disposing the Australian force in camps in southern Palestine, with the Australian overseas base and the headquarters of the 6th Division side by side in Gaza. Morris decided, however, that the base could not be adequately housed at Gaza, and at his request office space was found in Jerusalem.

The voyage of the main Australian-New Zealand convoy was spent in hard training, with a break at Colombo where the men were given a day ashore. For all but a few it was their first experience of Asia and of a city crowded with dark-skinned people. The arrival of the Australians and New Zealanders in an Eastern country on this and later occasions caused some anxiety to both the local authorities and their own officers. The European soldier, coming from countries where class distinctions are more rigid, and the American, brought up in the presence of a Negro population, are conditioned to accept the castes and poverty of the East more easily than does the Australian, who habitually treats the Asiatic in a friendly and jocular style. To the end of the war most Australian soldiers had not acquired that remote and autocratic manner towards Asians then considered essential to the maintenance of European prestige in the East – a manner imitated by Europeans from that adopted by Asian people of rank and wealth towards their inferiors. However, in spite of misgivings, and apart from the fact that many of the Australians handed their haversack lunches to importunate native beggars, their deportment on this occasion appears to have evoked little criticism from the local officials. None were absent without leave after Colombo.

On 12th February the ships arrived at Ismailia in the Suez Canal, where the Secretary for the Dominions (Mr Eden8), who had come from

England to welcome the first Dominion troops to arrive in the Middle East, Sir Miles Lampson and General Wavell boarded the leading transport – the Otranto – in which were Brigadier Allen and his staff. On the night of the 12th–13th the Australian brigade disembarked at Kantara and entrained for Gaza and El Majdal, whence buses took them to the tented camp awaiting them at Julis. There they were welcomed by groups from two British9 regular battalions of the Palestine garrison – the 2/Black Watch and 1/Hampshire Regiment, who had pitched tents for the newcomers.

Brigadier Allen established a nucleus divisional headquarters at Qastina, five miles from Julis where Colonel Wootten temporarily commanded the 16th Brigade group, 3,500 strong. The camp at Julis was on green farmland, with the blue Mediterranean to the west and a pleasant grassed valley to the east. As soon as the Australians arrived they began to improve the camp. Sanitation, which was still defective, was made adequate; roads and paths were cut and gravelled; tents were furnished with tables and cupboards made from packing cases, and bordered with white stones and sometimes beds of flowers; trees were planted; familiar names were given to roads and living quarters – “Wagga”, “King’s Cross”, “Ingleburn” and the like. Later the camps were subdivided into sections or “lines” each of which was named after a general of the 1st AIF; thus the five sections at Julis were named Monash, Goddard, Gellibrand, Hobbs and Leane. Indeed Julis saw the beginning of the new Australian soldier’s habit of giving a neat and homely air to camps in remote and unpromising places.

Within a few weeks batches of officers and men from every unit were doing courses at British army schools – the weapon training school at Bir Salim, the Bren carrier course at Sarafand, the recruit training depot, the cipher course in Jerusalem and others.10 Meanwhile, on 1st March, the

units began a three months’ course of training which was to culminate in three weeks during which battalions would exercise as battalions. Later new weapons were issued on a scale which made training possible – seventeen Brens, six anti-tank rifles and four 2-inch mortars to each battalion – and these were learnt under the instructions of the officers and NCOs who had gone to Palestine in December with the advance party.

All units are hard at work (wrote one diarist on 9th March) . At night offices are a blaze of light. ... Everyone realises that this is a dress-rehearsal before we play our role in the grim drama now being staged in Europe. Hence all are anxious to learn how to play their part and be ready for their cue at any moment.

The twenty-three British infantry battalions in the Middle East belonged to the regular army and, in the eyes of the Australians, were masters of a trade they themselves were busily trying to learn. The newcomers were happy to find that a battalion of the Black Watch had been given the task of fostering them when they arrived in Palestine, and were flattered when these British regulars praised their drill. Allen and his battalion commanders took pains to establish close associations with this regiment and with the 16th British Brigade. He arranged for a platoon of Australians

to be attached to the Black Watch for training, and later organised exercises in which both British regulars and Australians took part, so that to the high spirit of his force and the exacting tradition it had inherited from the First AIF would be added the technical skill and smartness of British regulars. In Palestine the Australians soon received frequent reminders of the traditions they inherited from the First AIF

Palestine had never known Australians as anything but soldiers (wrote one observer later). The awe in which the local Arab population, with memories of the Light Horse, held Australians had an excellent effect on the troops’ bearing and morale. Vernacular newspapers, both Jewish and Arab, hailed the AIF’s arrival in extravagant terms. One leading Jewish journal for example, under the heading, “Pride of the British Army”, wrote: “If you ask a British general who are the best soldiers in the British Empire he will answer without hesitation: The Anzacs. ...”11

To travel is one of the soldier’s chief compensations for a life that has more than its share of danger, discomfort, separation of lovers, and subjection to authority. To Australians the opportunity of seeing the world has a special appeal because they live in comparative isolation yet are possessed by exceptional curiosity about the world’s affairs, those of their own country seeming insufficiently varied and picturesque to satisfy their restless minds. To successive contingents of them, Palestine, and in particular Jerusalem with its cosmopolitan people and its sacred antiquities, and even Tel Aviv, were objects of intense interest. From the outset the commanders helped particularly by Major Goward12 of the Comforts Fund organisation, and with the cooperation of the well-equipped YMCA in Jerusalem, had taken pains to make tours so cheap that all could afford them.13 The intention was partly to keep the men out of trouble – always a particular anxiety of leaders of lively, relatively well-paid Dominion troops. The senior leaders knew from the experience of twenty years before that many of the British, Egyptians and Palestinians were convinced that Anzac troops were habitually ill-disciplined, and they were anxious to prove these critics wrong. Consequently steps were quickly taken also to provide sporting gear, to arrange bathing beaches where life-saving teams on the Australian model were established, to build cinemas, and equip clubs.

The discipline of Dominion troops did, in fact, raise special problems. From the outset very heavy fines were imposed on men who had been absent without leave. And in April Brigadier Allen had felt it necessary to issue an instruction on discipline that included examples of “discreditable behaviour” such as excessive numbers riding in gharries, eating and drinking in streets, scattering small coins, directing traffic, riding donkeys in the streets, collars undone, hands in pockets, obscene language. The

opening in May of a new brick theatre with seats for 1,000 brought forward again the question, persistent in a Dominion force, of the extent to which class distinctions, natural in a European army, should be applied to Dominion troops. There was a rowdy demonstration outside the theatre by men – “an irresponsible element” said the diarist of the 16th Brigade – who objected to the seats being divided into three grades, 80 mils (2s) for officers, 60 for NCOs and 30 for others. “The demonstrators,” added the diarist, “claimed this to be a class distinction grading, and that any person ... who could afford the best seats should be allowed to occupy them. They also disapproved ... marching the men to their seats. The demonstration began with catcalls and boos and later ... some men began hurling oranges and stones through the windows. ... The disturbance was eventually quelled by officers.”

Another step towards providing his men with comforts in a strange land was taken by Allen when, early in March, he called the three war correspondents together and suggested the establishment of a newspaper. It was to differ from most of the AIF magazines of 1914–18 in being a complete newspaper – one which would be a serious journal and not merely a magazine of local gossip and satire. He appointed to edit the newspaper Sergeant Roland Hoffman, the Sydney newspaperman who had been writing his brigade’s war diary. Goward agreed that the cost of producing the newspaper should be paid from the Australian Comforts Fund and, on 15th March, the first issue of a paper eventually named AIF News appeared, with four cyclostyled pages of Australian and local news. Through the war correspondents, newspapers in Australia agreed to contribute a brief news service and the correspondents themselves wrote most of the local news.14

Of all amenities enjoyed by an army far from home mail is the most important, and the irregularity of the air mail and the infrequency of the sea mail was a genuine hardship. The rate was 60 mils (1s 6d) for a letter, 30 mils for a card – a heavy charge for married men receiving only 1s a day and allotting the remainder to their wives.15

Soon after its arrival the Australian force possessed its own canteens at which the men could buy beer, food and other luxuries and necessities. These had been established by the energy of Mr G. L. Gee,16 a Sydney

merchant who had served in the Pay Corps in the First AIF. He had been told by the Quartermaster-General, Major-General Smart,17 in December, that, if he wished, he would be considered for appointment as deputy director of canteens, and was asked to draft proposals for an Australian canteens service overseas. Smart at first considered that the Australian deputy director should be a liaison officer with NAAFI,18 the British canteens organisation, which should also serve Australian troops. Gee, however, argued that it would be necessary to obtain for Australian troops the kind of goods that they were used to, that greater profits would be made if the canteens were under Australian control than from a sharing agreement with NAAFI, and those profits would be immediately available to provide amenities. After having elaborated his proposals Gee was appointed to control AIF canteens with the rank of major. He was informed that £2,000 would be allocated to finance the service, but decided that this would be far too little and, with the support of Brigadier Allen, persuaded the committee of the Sydney Lord Mayor’s Patriotic Fund to lend an additional £3,000. Gee thereupon bought goods valued at £8,217 13s 4d, partly on credit. He had completed these transactions in time to ship the goods in the Otranto before it sailed with the first convoy. Gee then flew to Palestine where he was informed by Brigadier Morris that, after all, the canteens in Australian camps were to be conducted by NAAFI and that Gee would act as liaison officer. Again, however, Gee was able to persuade his senior to alter the decision. The outcome was that the Australian service took over from NAAFI the canteens in the Australian area, including their goods and equipment.

Thus Allen and Vasey, with the help of exceptionally keen and able officers who, in the cases of Goward and Gee, had experience of similar work in the previous war,19 laid firm foundations for a generous system of amenities destined to grow to considerable size.

Allen not only administered command of the nucleus headquarters of the AIF, the 6th Division and the Overseas Base, but was appointed by General Barker to be commandant of the Gaza–Beersheeba area, and thus became responsible for law and order, and partly for general civil administration in approximately one-fifth of Palestine. To this extent the nucleus Australian force was playing a part in the garrisoning of the Middle East.

–:–

For the present the British leaders in London were confident that Germany would not move into the Balkans in the spring, and that neither Italy nor Russia (then regarded as a potential enemy) would soon enter the war. The Chiefs of Staff informed the Australian High Commissioner

(Mr Bruce) that it was not intended to employ the Australians in policing Palestine, though their presence there would have a salutary effect. If, when the Australian forces in the Middle East were fit to take the field, the situation there was quiet, they wished them to complete their equipping in France or England and eventually join General Gort’s20 British Expeditionary Force in France, which was being increased as fast as Britain’s slow-growing store of equipment would allow.

When war broke out the British regular army in the United Kingdom had included five infantry and one armoured division; and a second armoured division was planned; the Territorial Army was being doubled, the object being to attain a strength of 450,000, with eighteen infantry, six motorised, two armoured and seven anti-aircraft divisions (the latter for the anti-aircraft defence of the United Kingdom). However, there was yet only enough equipment to enable fewer than one-third of these to take the field. By April thirteen British divisions were in France, and three of these were only partly-armed. One Canadian division was arriving in England. In the minds of the British leaders was a picture of a new Western front, with the French Army on the right and the British, including Canadian, Australian and New Zealand divisions, on the left. The main problem was to find enough weapons to arm this force, particularly such weapons as guns and tanks.21

But although the Middle East seemed not to be immediately threatened General Wavell and his fellow commanders-in-chief faced delicate political and military problems there. Wavell had high and varied qualifications for carrying out perhaps the most complex task of the three. Much of his service during the thirty-eight years since he had joined the army as an infantry subaltern in the South African War had been in the Middle East or the countries bordering it – India before 1914, Russia in 1916 and 1917, a senior staff post in Palestine in the last year of Allenby’s campaign, the command in Palestine in 1937–38. He had long been considered one of the leaders of British military thought, had written a short history of the Palestine campaigns of 1916–18, a biography of Allenby, and a series of papers on generalship and soldiering that were both original in substance and engaging in style. These, like his speeches and writings during the war, were patently the fruit not only of varied experience and shrewd observation but of reading in a field far wider than most soldiers permit themselves. In these writings he emphasised the importance of knowledge of “topography, movement and supply”. “These,” he wrote, “are the real foundations of military knowledge, not strategy and tactics as most people think. It is the lack of this knowledge of the principles and

practice of military movement and administration – the “logistics” of war, some people call it – which puts what we call amateur strategists wrong, not the principles of strategy themselves, which can be apprehended in a very short time by any reasonable intelligence.”

The general of his ideal would spend as little time as possible in his office, as much as possible with the troops (a particularly useful principle for the commander of an army drawn from many peoples and scattered among several fronts). Similarly, he advised the soldier to read not outlines of strategy but biographies, memoirs and historical novels, wherein he would get “the flesh and blood of it, not the skeleton”. Above all, the commander must possess robustness of mind to enable him to stand the strain of the appalling responsibilities he must shoulder in battle; character was of greater importance than brains or experience; and he must be willing to take risks. At the end of his lectures on generalship he spoke for a majority of the keen and able British commanders of his generation who had been trained in the mud and blood of 1914–18 when he said: “Let us add one more altar, ‘To the Unknown Leader’, that is, to the good company, platoon, or section leader who carries forward his men or holds his post and often falls unknown.” If Wavell was not endowed by nature with all these gifts there can be no doubt that he strove to cultivate them, yet it was his nature to conceal his virtues beneath a genuinely reserved and unassuming exterior and an uncompromising honesty which forbade him to try to cover up a mistake but rather compelled him to confess it – a rare quality in a soldier.

But, since both from Cairo and in later posts, Wavell was destined to command armies which were made up very largely of Dominion troops, it was unfortunate that he had not had any close association with a Dominion before – unlike, for example, General Dill22 who had served on the staff of an Australian division in 1917, General Brooke,23 who had served on a Canadian staff, or General Montgomery,24 who had spent his childhood in Australia. It was rare for a British officer clearly to understand the independent status of the young nations, common for them to refer to the Dominions as colonies and to think of them as such, and difficult for them to accept the fact that Dominion governments had responsibilities towards their own troops no less telling than those borne by the Ministers in Whitehall • towards theirs. It was difficult also for the general run of British commanders to appreciate that the Dominions had military traditions derived from their own national characteristics and so firmly established that they were to be judged on their own merits and not entirely by the standards of the British Army. To men of the Dominions who were closely in contact with the British Army during the

war it was a rare and gratifying experience to encounter a British soldier whose view of the Australian or the New Zealander was not expressed more or less in the words: “Fine fighter, but overruns the objective; undisciplined when he’s out of the line.” To a majority of the British commanders whom the Australians encountered, the spontaneous, equalitarian Dominion citizen was a problem child. For example, Wavell, in his address to the 16th Brigade at Gaza in February – his first address to Australians – referred in his opening words to the Australian reputation for lack of discipline and returned to the subject later in his speech, saying that the Egyptians had “lively apprehensions of what Australians might do in Cairo and elsewhere in Egypt.” “I look to you,” he added, “to show them that their notions of Australians as rough, wild undisciplined people given to strong drink are incorrect. The Egyptians, generally speaking, are a kindly and peaceable people, very easy to get on with. They have good manners themselves and very much appreciate good manners.” These were not the happiest words with which to welcome a force of British volunteer citizen soldiers. Later, when an Australian force arrived from England, Wavell’s welcoming speech contained a complaint about the discipline of the 6th Division in Libya – a subject on which he had been wrongly informed.25

The problem which Wavell and his fellow commanders faced – the defence of British interests in the Middle East – had been carefully considered by the Committee of Imperial Defence. Before the Russo-German agreement of August 1939 British planning was aimed at countering attack by Italy, and staff talks on this subject had been held with French commanders. The British staffs hoped that conflict with Italy would be avoided, and consequently that commitments would not occur in the Balkans where such a conflict might easily arise, but plans were prepared not only to meet an Italian attack but to take the offensive against her. After the Russo-German agreement the military planners took into account the possibility of attack also by Russia. This possibility gave added importance to Iraq and Turkey. In October 1939 Britain and France (who were already under an obligation to support Greece against oppression) signed a military convention with Turkey, though in the staff talks that followed, the British and French representatives were able to offer only limited help.

General Wavell’s headquarters and a great part of his army were in Egypt, an independent kingdom of whose support in war Britain could not be certain. Her relations with that country were defined in a treaty, of 1936, which provided that for the following seven years British troops might remain in the neighbourhood of Alexandria with freedom of move-

went for training, in war or in an “apprehended international emergency”. Thus the British army in Egypt was occupying a foreign land whose Government, though it broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, seemed likely to avoid committing itself more deeply to the Allied cause. When the war began that army included the 7th Armoured Division, one of only two which Britain possessed, and it consisted of two brigades each of only two instead of three regiments;26 one brigade group of the 4th Indian Division, four artillery regiments and eight battalions of infantry. In Palestine were ten battalions of infantry, two cavalry regiments but no artillery. Thus, though there were infantry enough to form two divisions, there was little artillery (only sixty-four field, forty-eight anti-tank and eight anti-aircraft guns) and not one complete division, either armoured or infantry. Yet it was estimated that in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica there were, in December 1939, fourteen Italian divisions (which had nevertheless to take into account a French army of about the same strength on their western flank), and in Abyssinia some 140,000 men, fairly well provided with artillery and tanks. To watch the frontiers of Italian East Africa Wavell had, in the Sudan, little more than a brigade; and, in Somaliland, some 500 men of a native camel corps (there were about 5,000 French native troops in Jibuti). In Kenya were some battalions of African troops with British officers.

In Palestine, from 1936 until the outbreak of war, the Arabs had been in rebellion against the continuance of Jewish immigration and the transfer of land to the Jews. However, just before war broke out Dr Weizmann, the leader of the moderate Zionists, told Mr Chamberlain that the Jewish community would stand with Britain and the democracies; and, a few days later, leading Arabs assured the British High Commissioner, Sir Harold MacMichael,27 of their loyalty. Both Jews and Arabs volunteered for national service. Nevertheless, although influential leaders both Arab and Jewish called a truce there was still a bitter dispute unsettled, and restless men at large. Immigration of refugee Jews beyond the agreed quota continued28 and, a fortnight after the arrival of the Australians and New Zealanders, the Palestine Government published regulations putting into effect a policy announced nearly a year before, which divided the country into three zones, in one of which purchase of land by Jews was prohibited, in another restricted and in the third free. The enforcement of these regulations led to demonstrations and strikes by Jews in Jerusalem, Haifa and Tel Aviv.

In February 1940 Wavell’s responsibility was extended to include British land forces in East Africa and, if need be, the Balkans, and he was

instructed that, in an emergency, the command of the troops in Iraq and Aden (in each of which an air officer was in command) would be included. Wavell’s task demanded not only the qualities needed in a general able to control operations over a wide area, but much tact and political adroitness. In addition, there was no theatre in which greater care was needed to ensure cooperation between the three Services. Coordination of plans was maintained by a Joint Planning Staff of which the senior staff officer of each commander-in-chief was a member; and a Middle East Intelligence Centre was established under Colonel Cawthorn29 with a staff drawn from the three Services and civilians.

Before the 16th Australian and 4th New Zealand Brigades arrived in February Wavell’s force had been increased only by one more Indian infantry brigade for the 4th Indian Division and a battalion of British infantry from China. In March the 1st Cavalry Division (horsed), a British Yeomanry formation, incomplete in training and equipment, arrived in Palestine. Thus six divisions were then represented – the 7th Armoured, 6th British, 1st Cavalry, 6th Australian, New Zealand and 4th Indian – but none was at full strength and fully equipped, and four were only nucleus formations.

–:–

What danger had there been in the early months of 1940 of Italy entering the war on Germany’s side? Although the British staffs did not fully realise it, Italy was little better prepared for war in 1939 than in 1914. Her people and a group among the leaders disliked and mistrusted the Germans; she lacked raw materials; and her army was ill-equipped, poorly-led and in low spirits. Of her forty-five divisions only ten were fully-armed and ready for action. Before Germany attacked Poland, Mussolini, aware of his country’s economic and military weakness, informed Hitler that he would not be ready for war until 1942. The Russian march into Eastern Poland further depressed the Italian leaders, particularly because they feared the spread of Russian influence in the Balkans where they, in common with the Germans, hoped to gain power and territory. Count Ciano, Mussolini’s Foreign Minister, wrote on 25th September, probably quoting his leader: “They (the Russians) have two weapons that make them still more terrible: pan-Slavic nationalism, with which they can bring pressure on the Balkans, and Communism, which is spreading rapidly among the proletariat all over the world, beginning with Germany itself.”30

However, on 18th March 1940 Mussolini met Hitler at the Brenner Pass and affirmed his intention of entering the war on Germany’s side, but said that he would choose his own time. Britain’s partial blockade of Italy infuriated Mussolini but not sufficiently to cause him to take the plunge. Then came the second climax of the war. The German success in overrunning Denmark and Norway excited the Italian leader. The

Norwegian campaign was still in progress when, at 5 a.m. on 10th May, the German Ambassador in Rome visited him with the news that the German Army had invaded Holland and Belgium.

On 15th May the Dutch surrendered. On the 19th, Churchill, who had replaced Mr Chamberlain as Prime Minister on the 10th, encouraging the people with his thunderous oratory and buoyant faith, declared that Britain might look forward with confidence to the stabilisation of the front in France. But on the 21st the British and French Armies as well as the Belgian were in full retreat. M. Reynaud, the new French Prime Minister, spoke of “incredible mistakes which will be punished”, and admitted that “our classic conception of the conduct of war has come up against a new conception.” On the 25th twenty-five French generals were removed. On 28th May Belgium capitulated and the British Expeditionary Force was being embarked at Dunkirk.

On 30th May Mussolini, who had appointed himself supreme commander of all the Italian forces, informed Hitler that he proposed to declare war on 5th June unless Hitler considered that date inconvenient. Hitler expressed enthusiasm but asked for a postponement of a few days because, he said, he proposed a decisive attack on French airfields and feared that Italian action might alter the French dispositions. Italy entered the war at midnight on the 10th–11th; but it was not until the 21st that Mussolini ordered his army to attack the French, who were then discussing an armistice with their German conquerors.

In the four months between the departure of the first Australian convoy for Palestine and the opening of this calamitous episode in western Europe some cautious progress had been made with Australia’s military preparations. On 1st January General Squires had revived the proposal, originally made by the British Chiefs of Staff in November, that a 7th Division be raised which, with the 6th, would form an Australian corps. Attack by Japan now seemed less likely, he said, and added:

It is apparent that the safety of the Empire and of Australia depends on the defeat of Germany and also that the resources of the Allies must be used to the limit of practicability in resisting the German attacks that are almost certain to commence in the European spring. The Maginot Line may well be secure, but a successful attack through Holland and Belgium could turn the main Maginot defences, apart from giving the enemy possession of ports which may well mean the difference between success and failure in his attacks at sea.

When he was asked by the ministers what the strength of such a force would be, Squires replied that it would need either 48,650 or 41,978, according to whether the Australian or the smaller British establishments were adopted, and that probably from 36,000 to 46,000 reinforcements

would be required each year. On 28th February the War Cabinet decided to form the new division and the necessary corps troops, first recommended four months earlier, but on the British establishment; thus the three surplus battalions of the 6th Division could be used in forming the

7th.31 Also, in response to a request from the British Government for companies of experienced railway constructors and foresters, it was agreed also to form three railway construction companies, a railway survey company and two forestry companies, which, with a small headquarters for the railway group, would total 1,243 officers and men.

An interesting aspect of the appointments to the new division was that two brigadiers (including Brigadier Milford,32 the artillery commander), one battalion commander, and the commanders of several of the corps units were officers of the Staff Corps, whose members had been grievously disappointed when none were allotted commands in the 6th Division. Robertson,33 the commander of the 19th Brigade which was destined to join the 6th not the 7th Division, was considered an outstanding leader and a particularly able trainer. He had served in the light horse on Gallipoli and in Palestine, and between the wars had left his mark particularly as chief instructor at the Small Arms School, as Director of Military Art (senior member of the teaching staff) at the Royal Military College, and later in command of the garrison at Darwin. He was a confident commander, sure of himself and of any troops he had trained. He believed that physical hardness was one of the first necessities of military efficiency; he took special pains to insist on smartness of dress and deportment. Some successful commanders have been unassuming and inconspicuous, others have striven to present their men with a picturesque figure to look up to and talk about, perhaps to emulate. Robertson was of the latter type, just as definitely as Mackay, for example, was of the former. He was ambitious and was criticised for making no secret of it, but this ambition was with him more than a personal affair, and embraced the men he commanded.

Plans for the formation and training of the new force were still being elaborated when, on 3rd March, General Squires died after having given nearly two years of service in the Australian Army. He was replaced by calling back from retirement the distinguished soldier who (C. E. W.

Bean had written) played “the outstanding part” in building the First AIF – General Sir Brudenell White. No one more learned in the problems that faced the leaders of a Dominion expeditionary force could have been found. White, although then only 38, had been the senior general staff officer at Army Headquarters when war broke out in 1914 and, after that, successively chief of staff of the 1st Division, and to Birdwood at Anzac and in France. He had been Chief of the General Staff from 1920 until 1923, when, at the age of 46 years, having occupied the highest post the Australian Army could offer, he resigned to become chairman of the Commonwealth Public Service Board. It was one of White’s first acts to recommend that Blamey, who had succeeded him as chief of the Australian Corps in 1918, should be given command of the new corps.

Blamey’s promotion again brought forward the question of Lavarack’s employment. Mr Street, after taking the advice of White, recommended to the War Cabinet that Lavarack be appointed to command the 6th and Major-General Mackay, who commanded the 2nd Division of the militia, the 7th, but the Cabinet, after consulting Blamey as well as White, reversed the order and appointed Mackay to the 6th and Lavarack to the 7th.34

The staff of the new corps, like that of the 6th Division from which a number of its officers were promoted, was of exceptional quality. Again there was a large field of thoroughly-trained officers to choose from; at that time the Australian regular officer corps could have staffed a far larger force (although only by gravely depleting the headquarters and schools in Australia). The new staff was led by Rowell, who had been Blamey’s “G1” in the 6th Division and now became his “BGS” (Brigadier, General Staff). To the general staff were added a group of picked staff college graduates, including Lieut-Colonels Rourke35 and Irving36 and Major Elliott;37 in the succeeding weeks two capable non-professional officers, Majors Rogers38 and Wills,39 were appointed to the Intelligence, a branch which, peculiarly, had little appeal for professional staff officers (though there was never a lack of highly-qualified regular officers for appointments in ordnance and other services). Rogers, an industrial scientist and business executive, had served in the ranks and as a young battalion, divisional and corps Intelligence officer in the previous war; Wills, a

leading business man of Adelaide, had served in a British infantry regiment in the earlier war. General Wynter dropped a step in rank and became senior administrative officer (Deputy Adjutant and Quartermaster General), a post somewhat smaller than his exceptional experience and talents deserved but the highest the overseas force could offer in the field in which he was outstanding. Next to him was Colonel “Gaffer” Lloyd,40 considered one of the ablest of the group of particularly promising officers who had been at Duntroon in 1918 and graduated into the Staff Corps in the years immediately following the war. As commander of the artillery Brigadier Clowes,41 senior among the Duntroon graduates, and until recently chief instructor at the School of Artillery was chosen; most of their contemporaries considered that he or Rowell would be the first Duntroon graduate to fill the highest post in the Australian Army. To command the medium artillery Colonel Ramsay,42 a schoolmaster who had been in the ranks in 1918 but had won rapid promotion in the militia, was promoted from the command of the 2/2nd Regiment; the senior engineer (Steele), signaller (Simpson43), and medical officer (Burston44) of the 6th Division were similarly promoted. The senior ordnance officer was Brigadier Beavis who, like Wynter, was qualified to hold considerably higher appointments in his branch than the best the corps offered. All these staff officers were considered fit for rapid promotion, and since the force would expand, as the first AIF had done, they were likely to attain it.

–:–

The 7th Division was still being formed when, on 1st May, the British Government had warned the Australian Prime Minister of the possible entry of Italy into the war, and, as the Mediterranean would be a theatre of war, advised that the second and third convoys of the AIF (chiefly the 17th and 18th Brigades) be held at Colombo and Fremantle respectively. The second convoy had sailed from Melbourne on 14th and 15th April, the third was to depart from Melbourne on 5th May. On the 8th advice was received from the British Chiefs of Staff that the two convoys should continue their voyage, and the War Cabinet agreed to this, though its members were critical of the paucity of the information they were receiving from London, feeling strongly that, particularly while such large forces were at sea, at least the Prime Minister should possess

“documentation relating to Allied activities and the growth of their efforts, and critical reviews or intelligence reports as to parallel enemy action”.

The German invasion of France had begun when, on 15th May, the Australian Government received a cable from the Dominions Office that shed a little light into the darkness. It said that plans were being made to divert the third convoy to Cape Town and suggested that it travel thence to England. Always anxious to prevent the splitting up of the force, even in those days of tension, the War Cabinet asked whether it would not be possible for the force concerned to complete its training in the north-west of India or in South Africa, whence it would be easier for it to rejoin the remainder of the division in Egypt. The Ministers decided that, in the meantime, General Blamey, who was due to leave for Palestine on 25th May, should remain in Australia (part of his staff, including his chief administrative officer, Wynter, was in the third convoy) ; and eventually that the third convoy should go to England.45 Already the War Cabinet (on 22nd May) had approved the formation of a third division of the AIF, to be numbered the 8th, although, at that time, only 6,000 men had been enlisted for the 7th Division and corps troops, which together would require 30,400.46

On 4th June the Ministers in the War Cabinet, who still were awaiting the arrival from London of a detailed summing-up of the new situation, decided that General Blamey should go to Palestine. This decision was recommended by General White who contended that General Mackay was inexperienced in the “higher administration and political principles relating to the control of the AIF”; he expressed the opinion that the next strong German effort would be made against the French and that the AIF should be sent to the front there by way of Marseilles, because “it was of great military and psychological importance to have Australian troops in France”. A week later, however, the Ministers summoned the Chiefs of Staff to advise on the situation resulting from the entry of Italy into the war which had taken place the previous day. It was already apparent that France was on the verge of defeat. The First Naval Member, Admiral Colvin,47 said that if France was overcome Britain would have to withdraw from the Mediterranean except for the use that could be made by entry through Port Said; Air Chief Marshal Burnett48 considered that it would be impossible to use the Red Sea until the Italian air forces in East Africa had been rendered ineffective. Nevertheless General White advised that Allied naval strength was such that the local defence of Australia should be considered secondary to Empire cooperation, and he urged that the AIF formations in Australia be sent overseas as soon as possible, arguing, incidentally, that the Australian was “a much more manageable soldier when separated from his family and political and other

influences”. At meetings during the following five days, when White and his colleagues of the navy and air force presented detailed proposals, it was decided to form a fourth AIF division if the British Government agreed and equipment was available, and at the same time to train and equip a home defence force of 250,000 men, including the 30,000 to 40,000 of the AIF who were likely to be under training in Australia. It was estimated that there were then 75,000 in militia units, 37,000 men of the AIF in Australian camps, and about 38,000 in the “returned soldiers’ reserve” and the militia reserve.

The graver the news from France the more rapidly the number of recruits for the AIF increased. The former doubts whether the war would be decided without bitter fighting on land had vanished.49 By 6th June recruits for the new formations reached 25,000, by the 27th 50,000, by 25th July 82,000 and 13,000 were awaiting medical examination – though only 1,836 officers had applied and been accepted to fill 2,429 vacancies.50 Thus the ranks of the two new divisions had been filled and there were 50,000 men over, more than enough to form a fourth and fifth division. The Cabinet decided to suspend recruiting for the time being.

Gross enlistments from the militia to the AIF (said Mr Menzies in a public statement on 19th July) have left the militia divisions for the moment considerably below strength and it is necessary now to bring the militia up to its proper strength. In the view of the Government its next task will be to raise the militia force to greater strength, and to make arrangements for equipping such a force and giving it adequate camp accommodation. This task will come before the formation of additional AIF units.51

Thus the Government again found itself being pulled in two directions in consequence of the existence of two armies – the volunteer overseas force and the (chiefly) conscript militia – and of two objectives – to contribute forces to the British pool and to build up an army to meet possible attack by Japan. After a lag of a few weeks while men who had already offered were enlisted-32,524 are recorded as having completed their enlistment in August – the numbers fell spectacularly. Only 1,049 enlisted in September, 995 in October, 1,028 in November, and most of these were evidently men who had offered themselves in July or earlier and been deferred.

The crisis had brought an ardent response also from the veterans of the old AIF In May and June, at the suggestion of the Returned Soldiers’ League, the Government extended its army reserve to provide that the league should organise a Returned Soldiers’ League Volunteer Defence Corps on the lines of the British Home Guard.52

On the 16th June the French Government asked for an armistice, and on the 18th the last British troops embarked from France. The British Army had to leave nearly all its guns, tanks and vehicles behind. It became evident that for many months the British factories on which Australia had hitherto relied for the future supply of all but a few types of weapons would be fully and strenuously employed re-arming the forces in Britain. White informed the War Cabinet that although Australia had “a few” medium guns, and the old 18-pounder field guns and 4.5-inch howitzers – but not in great quantities53 – and a fair equipment of medium and light machine-guns, she had none of the new 25-pounder guns, no anti-tank guns, no tanks, few carriers, and few anti-tank rifles. Each week 170 rifles54 and twenty Vickers machine-guns were being delivered, but no Bren guns would come from the Australian factory before the end of the year. There were thirty 3-inch anti-aircraft guns of an out-dated type, but the new 3.7-inch guns were now coming from the factory at Maribyrnong at the rate of one a week. All engines and chassis for army vehicles had to be imported, only bodies and some spare parts were made in Australia.

–:–

From the beginning of the war a multitude of problems had proceeded from the fact that Australia was unable to equip her armies from her own factories. The size of her expeditionary force, the organisation of that force and of the militia, the AIF’s destination, and many of the problems its commander was to face in the Middle East derived from a fundamental flaw in Australian policy, namely failure to recognise that effective defence depended on a nation’s ability to manufacture arms. It needed this crisis to bring home the fact that, until this foundation had been laid, Australia’s ability to defend herself must steadily diminish in relation to the military power of an enemy which did possess adequate factories; and that any overseas force she formed could consist only of men who must be equipped by her allies. In the sudden excitement of impending danger the tendency of the Government of a nation unprepared for war is to fill the ranks of its forces, to vote larger sums for the fighting Services, perhaps to take a census of men and wealth and materials. Until many months have been spent on planning and training, experiment and manufacture, such measures produce little more than lists of figures which, though they may comfort the citizens of the undefended nation, are likely to make no impression upon the probable aggressor, who knows how laborious has been his own progress towards military efficiency. In Australia even the shock produced by the outbreak of war had been insufficient to seriously disturb habits of thinking about defence acquired during twenty years. It has been shown above that after September 1939 there was still a tendency to seek methods of defence that would not be over-expensive in men and money; to leave the manufacture of arms

chiefly to Britain, from whom Australia would buy only what she needed; to give a few months’ training to the army and then allow it to disperse to its peaceful occupations; and to limit equipment to a training scale. The German invasion of France and the Low Countries produced a notable change in policy, though it was not until the nation had been at war for two years and two months that it began to take the step which most European nations had taken as a matter of course, year by year, in time of peace, namely to establish a full-time conscript army.

The Ministers, now realising that their modest plans for manufacturing munitions would not meet the demands of the new situation, on 21st May had appointed Mr Essington Lewis,55 chief general manager of the Broken Hill Pty Ltd which with its subsidiaries controlled Australian iron and steel production, to be Director-General of Munitions Supply with “the greatest possible degree of freedom from ordinary rules and regulations”. In the meantime the Government was doing what it could to send equipment to England from its meagre store. On the 14th May it had decided to dispatch 35,000,000 out of its reserve of 90,000,000 rounds of small arms ammunition, and, later, to send another 35,000,000 rounds of small arms ammunition and some hundreds of thousands of four types of shells and mortar bombs which were being made in Australia.56 In response to a later appeal from London Mr Menzies informed the High Commissioner there on 13th June that Australia could provide for the Second AIF, Vickers machine-guns, rifles, a number of articles of clothing, and certain engineer and signal equipment; from August, 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns would be delivered at the rate of four a month until a total of fifty was reached, 3-inch mortars would be supplied from November, carriers – deliveries of Australian-made carriers had begun in March – would be provided for the 7th and later divisions and, within a year, 100 Bren guns a month.

A disaster occurred on 13th August when an aircraft carrying to Canberra the Vice-President of the Executive Council (Sir Henry Gullett), the Minister for the Army (Mr Street), for Air (Mr Fairbairn57), the Chief of the General Staff (General White) and six others crashed and all were killed. This accident robbed the Ministry of White’s exceptional wisdom and experience and took three members whose knowledge of warfare was practical and wide: Gullett who had been a soldier and a war correspondent in the earlier war and, after it, had written a brilliant military history; Street who had followed distinguished service as a young infantry officer in 1914–18 with senior militia appointments between the wars; Fairbairn who had served as an air force pilot. A Ministry which in 1939, when

R. G. Casey was also a member, had been exceptionally rich in leaders with military experience became unusually weak in such men.58

In January when the first convoy sailed Australia’s military contribution to the Allied strength in Europe had been fixed at only one division. It had now been expanded to a corps of four divisions. This was a far smaller force than Australia had maintained in France and Palestine in 1916, 1917 and 1918. On the other hand, if all of it was sent promptly to the Middle East, it was likely to form the strongest single contingent in that theatre, on the Allied side.