Chapter 6: Victory at Sidi Barrani

The stage was now set for the opening of the desert battle which General Wavell and his subordinates had discussed before the Italian invasion of Greece. Thus far the new theatre of war had made relatively small demands on Wavell’s and Longmore’s forces, and the Italian Army’s failure to overcome the Greeks lowered an already low estimate of its efficiency. Although Western Desert Force was still greatly outnumbered by General Bergonzoli’s army, it had received useful reinforcements. It will be recalled that in October two tank regiments from England had joined the 7th Armoured Division, bringing its two armoured brigades each to their proper strength of three regiments; and the 7th Royal Tank Regiment had arrived, equipped with heavy “Matilda” tanks to be used with infantry to break into strong defensive positions. In September the 4th Indian Division had been completed by adding to it the 16th British Brigade; in November its own third brigade arrived. In the Matruh Fortress was assembled a force equal to two infantry brigades. The 4th New Zealand Brigade, had, since September, been in reserve either at Daba or Bagush; and on the edge of the Delta were the 6th Australian Division, now more or less complete, and the Polish brigade. Thus in three months the forces west of Alexandria had increased from two weak divisions to three at full strength or close to it, plus four infantry brigades; and within a few weeks the New Zealand and the 7th Australian Divisions would be complete, in units if not equipment, and the 2nd Armoured Division would have arrived.

In the desert throughout October and November mobile columns of the Support Group of the armoured division had continued to harass the enemy, who showed little disposition to press farther forward. There were few heavy clashes, the largest in this period being on 19th November when some 100 enemy troops were killed, eleven captured and five enemy tanks destroyed for a loss of three killed and two wounded.

Meanwhile the tactics to be employed in the coming battle had been set out in a memorandum issued by General Wilson: a rapid advance, a break-in by heavy tanks supported by carriers, a mopping-up by infantry who would be carried in vehicles as close as possible to the point of entry. On 4th November the brigade commanders had been informed that the attack would open on the 14th, but on the 12th it was decided that, because the building up of supply dumps was proceeding too slowly, and because of the loss of troops and aircraft to Crete, the attack would be postponed until the second week in December, when the moon would again favour a night attack. A realistic training exercise was carried out in the desert on 25th and 26th November. Elaborate steps were taken to ensure secrecy and surprise and it was not until 2nd December that brigade staffs and unit commanders were told the full reason for the

preparations that were being made around them. Planning was complicated by the fact that, while it was in progress, Wavell informed the field commanders that the 4th Indian Division was to move to the Abyssinian front soon after the attack, being relieved in the Western Desert by the 6th Australian Division.

Moreover, on 28th November, Wavell had sent Wilson an instruction enlarging the possible scope of the coming battle, the aim of which, it will be recalled, had been to cut up the Italian force and then withdraw on to Mersa Matruh again:–

I know that you have in mind and are planning the fullest possible exploitation of any initial success of Compass operation (he wrote) ... The difficulties, administrative and tactical, of a deep advance are fully realised. It is, however, possible that an opportunity may offer for converting the enemy’s defeat into an outstanding victory. It is believed that a large proportion of the enemy’s total strength in tanks and artillery is in the forward area, so that if a success in this area is achieved the enemy reserves in the rear area will have comparatively little support ... I am not entertaining extravagant hopes of this operation, but I do wish to make certain that if a big opportunity occurs we are prepared morally, mentally and administratively to use it to the fullest.

The problem that faced General O’Connor was, with a force numerically inferior but more spirited and expert and probably stronger in tanks,1 to defeat an enemy deployed in an arc of circular camps consisting of stone sangars and with an anti-tank obstacle round them. The Italians had a two-to-one superiority in artillery, but their camps were distributed across fifty miles of desert from the sea to the escarpment, and there were wide gaps between them. O’Connor believed that this arc was manned by one Italian and two Libyan divisions and that, between it and Bardia inclusive, there were four Italian divisions, arranged in depth. It was believed that these divisions were deployed thus:–

Sofafi and Rabia, 7,000 troops of the 63rd (Cyrene) Division, 72 medium and 30 light tanks.

Nibeiwa, Maletti Group (2,500 Libyans and 12 field guns).

Tummar and Point 90, 2nd Libyan Division (including 1,000 Italians).

Maktila and Sidi Barrani, 1st Libyan Division (including 1,500 Italians).

Coastal area west of Sidi Barrani, 1st (25th March) Division.

Azzaziya, 72 medium and 30 light tanks.

Buqbuq–Capuzzo, 2nd (28th October) Division.

Escarpment Sofafi to Halfaya, remainder of 63rd Division.

Bardia, probably 3rd (21st April) and 62nd (Marmarica) Divisions.

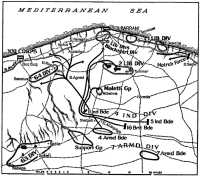

On 4th December a final conference at General Wavell’s headquarters was held, and on 6th December General O’Connor issued his orders. His

intention was, firstly, to destroy or capture enemy forces in the Nibeiwa–Tummar area, and to advance northwards through the gap towards Sidi Barrani, thus isolating Maktila; secondly, if the situation was favourable, to raid the enemy’s communications and dumps in the Buqbuq area; and, thirdly, to exploit towards Buqbuq and Sofafi. The task of the Matruh Force (Brigadier Selby) was to ensure that the garrison of Maktila camp did not move to the assistance of the Tummar camps. Accordingly the first objective of Major-General Beresford-Peirse’s2 4th Indian Division (to which the 16th British Brigade and 7th Royal Tank were attached) was Nibeiwa camp, whence they would advance to Tummar West, Tummar East and Point 90 camps and be prepared to advance northwards to cut off Maktila. The 7th Armoured Division would with its armour protect the deployment of the 4th Indian, and with its Support Group protect the left flank of that division; it would ensure that the enemy did not deliver a counter-attack from the Sofafi area; and, if the attacks succeeded, it would advance through the twenty-mile gap between Sofafi and Nibeiwa towards Buqbuq. Finally it would cover the withdrawal of the Indian division to Mersa Matruh – for it was still part of the plan to withdraw this main part of the force after the battle had been won. Naval ships were to shell the Maktila positions on the night before the attack; air support was to be given by No. 202 Group (Air Commodore Collishaw3) which included three squadrons and one flight of fighters, three squadrons and two flights of day bombers and three squadrons of night bombers. Two army cooperation squadrons (including No. 3, RAAF) were directly under O’Connor’s command.

So wide an area separated the two forces – the bulk of the armoured division was along the Matruh-Siwa road, some sixty miles from the enemy’s line – that O’Connor decided to move forward the attacking troops to positions about thirty miles from the enemy on the 7th–8th, to make a further advance on the 8th–9th, and attack in the early morning of the 9th. The first move was accomplished smoothly, and during the 8th the force was deployed motionless in the desert, half expecting discovery and air attack which did not come.

On the bitterly cold night of the 8th, in the moonlight, the 7th Royal Tank and the 1/6th Rajputana Rifles (of the 11th Indian Brigade) moved forward to a rendezvous five miles south of Nibeiwa, the sound of their vehicles being drowned by aircraft flying low overhead. At 4.45 a.m. on the 9th a second Indian battalion, the 4/7th Rajput Regiment, opened fire on Nibeiwa camp from the east, to distract the enemy’s attention. During the morning a second battalion – the 2/Camerons – joined the tank regiment. At 7.15 a.m. the artillery of the Indian division opened fire and the tanks, which had moved north to a point about four miles west of the camp, wheeled and advanced on its north-west corner where

The attack on Sidi Barrani, 9th December 1940

there was a gap in the minefield. As they neared it they came upon about twenty Italian medium tanks warming their engines outside the perimeter. These they disabled, and at 7.35 a.m. the attacking tanks lumbered into the camp and ranged about it silencing batteries and infantry posts.

Frightened, dazed or desperate Italians erupted from tents and slit trenches, some to surrender supinely, others to leap gallantly into battle, hurling grenades or blazing machine-guns in futile belabour of the impregnable intruders. Italian artillerymen gallantly swung their pieces on to the advancing monsters. They fought until return fire from the British tanks stretched them dead or wounded around their limbers. General Maletti, the Italian commander, sprang from his dugout, machine-gun in hand. He fell dead from an answering burst; his son beside him was struck down and captured.4

At 7.45 Brigadier Savory5 ordered the Cameron to follow through the gap. They moved in trucks to within 500 yards and then advanced on foot, being followed at 8 a.m. by the Rajputana Rifles. Half an hour later the camp had virtually been taken, though isolated posts held out until

10.40. Two thousand prisoners and thirty-five medium tanks were captured; the attackers lost only fifty-six officers and men, but six of the twenty-eight Matilda tanks that went into the attack were disabled on a minefield when leaving the camp after its capture. Italian officers said that they had no inkling that an assault was coming until about 5 a.m. when they heard the tank engines humming to the west of them.

Meanwhile the 5th Indian Brigade (Brigadier Lloyd6) had followed the 11th through the gap south of Nibeiwa. There it turned north to a point west of the Tummar camps, where it arrived at midday and awaited the arrival, soon after, of the 7th Royal Tanks which were to lead the Indian brigade into Tummar as they had led the Camerons into Nibeiwa. The supporting artillery opened fire at 1.30 and, the tanks, now reduced to twenty-two, advanced in a dense dust storm against the north-west corner of Tummar West. The Italians fought well, particularly the gunners, but again were quickly overcome. Twenty minutes after the tanks the 1/Royal Fusiliers were driven forward in the lorries of the 4th New Zealand Reserve Motor Transport Company, whose drivers abandoned their vehicles and charged forward with the Fusiliers. They were followed by the 3/1st Punjab. At 4.20 the third battalion of the brigade – 4/6th Rajputana Rifles – attacked Tummar East, but before they reached it they encountered a strong enemy column advancing thence to counter-attack towards Tummar West. There was sharp fighting in the course of which the Rajputana killed about 200 and captured 1,000 Italians and, at dusk, the battalion went into leaguer 500 yards north-east of Tummar West. Next morning they occupied Tummar East without meeting resistance. In the two Tummar camps 3,500 to 4,000 men had been captured.

Having broken through the semicircle of camps at Nibeiwa and Tummar General O’Connor decided that the Indian division should move north during the night and attack the Sidi Barrani area next day. The 16th Brigade, which had come forward to a position just west of Nibeiwa, the 11th Indian Brigade, the 7th Royal Tank (now with only eight of its original fifty-seven tanks in working order) and the artillery of the Indian division were ordered forward. The plan was that the 11th Indian Brigade, moving up behind the 16th, should prevent the enemy from escaping southwards, and the 16th and the tanks should cut the main road leading west.

One task of the 7th Armoured Division7 had been to protect the assaulting formations from interference by the strong enemy reserves in the Buqbuq-Sidi Barrani area and in the Sofafi-Rabia Camps. These were believed to include the Tank Group, the 63rd and a Blackshirt division (supposed to be the 1st, actually the 4th). The plan was that the 4th Armoured Brigade should destroy the Tank Group at Azzaziya and engage the enemy’s infantry reserves, while the 7th Brigade was held

in reserve; the Support Group was to engage the attention of the Sofafi–Rabia camps.

At 6.10 a.m. on the 9th the 4th Brigade advanced north-west from the Bir el Allaquiya area, passed to the south and west of Nibeiwa, fanned out and cut the road between Sidi Barrani and Buqbuq. At Azzaziya where 400 Italians surrendered to the 11th Hussars no tanks were found. The headquarters of the brigade were established at El Agrad.

Meanwhile Brigadier Selby had brought forward his detachment from Matruh Force. He had vehicles enough to transport only part of the Matruh garrison-1,773 troops. They moved in three columns: one, which he himself commanded, included the 3/Coldstream Guards, six field guns, three light tanks and a company of machine-gunners; the second included a rifle and machine-gun company, one field gun and eight dummy guns; the third, detachments of infantry and artillery and sixty-five dummy tanks. On the night of the 8th–9th the third column established a “brigade” of dummy tanks, to mislead the enemy into the belief that strong forces were concentrating in the north and rejoined the other columns, which had advanced during the night to a line running north-east to southwest through El Samn. Thence the columns advanced and by 11 a.m. had reached a wadi four miles east of Maktila. At 3.22 p.m. on the 9th Brigadier Selby learning that Nibeiwa had fallen and the 7th Armoured Division was nearing Buqbuq, ordered his little force to cut the road leading west of Maktila. There was little daylight left and it was not until the following morning that the Coldstream reached the main road, and by 10 o’clock it was evident that the Maktila garrison had withdrawn during the night. The Coldstream, with a tank troop allotted to Matruh Force, set off in pursuit.

On the morning of the 10th the 4th Armoured Brigade was lying like an arrowhead between Sidi Barrani and Buqbuq, facing on the west a series of Italian camps and strong points from El Rimth to Samalus and south of it; astride the road near Hamid (there the point of the arrow lay); and facing Sidi Barrani to the east. The 7th Hussars attacked the enemy’s posts round El Rimth but they were too strong to take without costly losses and by early afternoon the main strength of the brigade had been sent eastwards against the 4th Blackshirt and 1st Libyan Divisions, the 6th Royal Tanks joining Matruh Force (and eventually coming under the command of the 4th Indian Division) and the 2nd Royal Tanks attacking, also with the Indian division, astride the main road towards Sidi Barrani.

Although the Indian brigade and the tanks had not then arrived, the 16th Brigade had attacked towards Sidi Barrani alone at dawn on the 10th. Advancing over open country in a dense dust storm it was met by effective artillery fire and was held. However, during the morning, the 11th Brigade with the artillery of the 4th Indian Division and the tanks arrived and the advance continued. Finally a concerted attack late in the afternoon broke the enemy’s resistance, and by 4.40 Sidi Barrani had fallen.

That morning the Coldstream, advancing from Maktila had come under fire at El Shireisat, just east of Sidi Barrani. There they were joined at 4 p.m. by the 6th Royal Tanks and, in the failing light, an attack was launched on what appeared to be a small perimeter camp. The advancing tanks came under sharp artillery fire and some were hit but not abandoned; at 5.40 they withdrew. Learning from a captured Italian officer that the entire 1st Libyan Division, which had left Maktila on the night of the 9th, was in the camp, and that the men were in low spirits, Selby ordered the 6th Royal Tanks, now with only seven cruiser and six light tanks in action, to attack again, though without artillery or infantry support. This attack also ran into effective fire from anti-tank guns and the tanks eventually withdrew.

Thus, by nightfall on the 10th December, Sidi Barrani had been captured, though east of it the 1st Libyan Division was still an effective force and had repulsed the attacks of Selby’s men. The only enemy camp north of Sofafi still untaken was that at Point 90. On its left flank the 4th Armoured Brigade faced strong enemy forces in the Khur–Samalus camps. Farther south the Support Group had exchanged fire with the enemy outposts in the Sofafi–Rabia area and one tank regiment of the 7th Armoured Brigade (8th Hussars) had advanced to Bir Habata on the southern edge of the Sofafi-Rabia camps, but had been ordered, before it had achieved any results, to return to its brigade, still in reserve.

On the night of the 10th–11th the 11th Indian Brigade took up a north-south position south-east of Sidi Barrani with the 16th Brigade continuing the line to the coast, thus cutting off the enemy withdrawing from Maktila. The Central India Horse (the mechanised cavalry regiment of the 4th Indian Division) hemmed in the retreating enemy from the south. The Matruh Force was still to the east of this remaining enemy pocket. Late on the 10th Caunter8 had ordered that next morning his 7th Brigade should relieve his 4th, attack the Samalus–El Rimth positions and advance west, while the 4th moved south to the Bir Shalludi area, then west to beyond Sofafi to stop the enemy withdrawing from that area.

Next morning (the 11th) attacks were delivered by Matruh Force, the 11th Indian Brigade group and tanks, and during the day one group after another of the 1st Libyan and 4th Blackshirt Divisions surrendered; at 1 p.m. contact was established between Matruh Force and the 4th Indian Division. Meanwhile the 1,500 to 2,000 men in Point 90 camp had surrendered on the approach of the 3/1st Punjab and five infantry tanks, which had been under repair at Tummar West.

While these isolated survivors of the leading enemy corps – the group of Libyan divisions – were being overcome, it was discovered that, during the night the enemy had withdrawn from the Khur–Samalus and the Sofafi-Rabia camps. Early in the morning patrols crossed the main road east and west of Buqbuq on a wide front. Later the 7th Armoured Brigade took up the pursuit. A squadron of the 3rd Hussars, following the

retreating enemy along a track four miles west of Buqbuq came under heavy fire, bogged in a salt pan, and ten of its tanks were knocked out before another squadron overran the guns. However, the 3rd, 8th and 11th Hussars continued the pursuit and by nightfall had taken 14,000 prisoners – including many from the 64th (Catanzaro) Division whose presence at Samalus and Khur had not been known to the attackers – and sixty-eight guns, for a loss of thirty-six officers and men and eighteen tanks. It seems probable that the 2nd Blackshirt Division was broken in this pursuit.

However, although part of the 2nd Blackshirt and of the 64th Division failed to escape, the 63rd from Sofafi and Rabia succeeded in doing so. The orders to the 4th Armoured Brigade to change places with the 7th, issued at 11 p.m. on the 10th, did not reach it until the following day. At 6.30 that morning a patrol of the Support Group had found that Rabia camp had been abandoned. An infantry company reached Sofafi at 1.10 p.m. and found that it too was empty. Not until nightfall on the 11th was the 4th Armoured Brigade in the Shalludi area organising for a pursuit. The leading troops of the Support Group were then in contact with the retreating enemy. The 7th Armoured Brigade was beyond Buqbuq collecting prisoners.

The battle was over. Although the enemy division on the inland flank had been allowed to escape, the victory had been decisive and spectacular. Along the fifty-miles-wide battlefield and astride the road leading west lay a fantastic litter of abandoned trucks, guns and tanks, piles of abandoned arms and ammunition, of food stores and clothing, and of the paper which a modern army spends so profusely. It was some days before all the enemy dead had been found and buried. Long columns of dejected prisoners in drab olive-green and khaki streamed eastwards. In the whole battle 38,300 prisoners, 237 guns and 73 tanks were captured. Four generals were taken: Gallina of the Group of Libyan Divisions, Chario of the 1st Libyan Division, Piscatori of the 2nd Libyan, Merzari of the 4th Blackshirt. The 4th Indian Division, on whom nearly all the casualties had fallen, lost 41 officers and 394 men, of whom 17 officers and 260 men were lost in the 16th Brigade which had made the unsupported attack at Sidi Barrani.

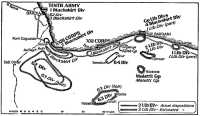

We know now that in December Graziani’s Tenth Army in Cyrenaica consisted of eleven divisions.9 He had hoped to launch an offensive between 15th and 18th December, but was forestalled. The Italian force in the Maktila-Sofafi-Buqbuq triangle had been considerably stronger in infantry than the British Intelligence staffs realised;10 instead of one Italian division and a half, two Libyan divisions and a strong tank group, there were three Italian divisions and two Libyan – but no concentrated tank group. The 4th (not the 1st) Blackshirt Division was at Sidi Barrani and not west of it, as had been believed. The presence of the 64th Division in a group of camps in the Khur–Samalus area had not been known. The whole 63rd was in the Sofafi camps. The forward Italian divisions – 1st and 2nd Libyan and 4th Blackshirt – comprised the Group of Libyan Divisions, the equivalent

Italian dispositions at Sidi Barrani

of a corps. Echeloned behind it was the XXI Corps, with the 64th Division at Samalus–Khur and the 63rd at Sofafi-Rabia; and, farther west, the XXIII Corps (1st and 2nd Blackshirt and 62nd Divisions).

However, the odds were not so greatly against the attacking force as a bald listing of the formations suggests. The Indian division, with its added brigade of British regulars, had the infantry strength of two Italian divisions; the two Libyan divisions were weak in numbers and fire power and of poor quality; and whereas O’Connor possessed a full armoured division and a battalion of heavy tanks the Italian tanks were dispersed and used ineffectively. In the Maktila-Buqbuq-Sofafi triangle it was (in British terms) a battle of one armoured and the equivalent almost of two infantry divisions against the equivalent of three infantry divisions. The attackers were well-led, confident and expert and possessed a weapon of surprise – tanks which need not fear the enemy’s guns. The defenders were clumsy, timid and unenterprising. A determined counter-attack by the reserve divisions might have stopped the attack, but the four divisions at Sofafi and west of Buqbuq – a stronger force than that actually engaged – made no effort to intervene, but were in haste to withdraw behind the fortified line at Bardia. The escape of the 63rd Division was a result rather of the errors of the attackers than of the skill of the Italian commander. The Support Group was not used to prevent its withdrawal on the 9th or 10th; on the 10th the Hussars were on the southern fringe of the Sofafi camps and were withdrawn, though they were given no other role that day. The late arrival of orders for the 4th Armoured Brigade delayed its pursuit south of the escarpment, but even if the orders had arrived in time the brigade could not have reached Sofafi before the Italians had withdrawn.

In brief, the attacking force succeeded in slicing off the leading corps of the Italian army, pinning them against the sea and destroying them; in the pursuit one of the supporting divisions was practically destroyed; the remaining divisions, some gravely battered, retired towards Bardia, where the 1st Blackshirt was already stationed. After the battle the Italians considered that of the eight divisions deployed from Bardia eastwards, the 64th and the 4th Blackshirt, 1st and 2nd Libyan were virtually destroyed, leaving four and remnants of others to defend the fortress. (But at the time the extent of the damage done to the enemy at Sidi Barrani was over-estimated by the British Intelligence staffs and the force withdrawn to Bardia correspondingly under-estimated.)

It will be recalled that General Wavell had decided before the battle began to open an offensive against the Italians in Abyssinia early in the coming year, using both the 5th Indian Division and the 4th, which would be replaced in the desert by the 6th Australian. As soon as the 4th Indian Division had completed its role in the Sidi Barrani battle he decided to send it to the Sudan as soon as possible, leaving the armoured division and the 16th Brigade to carry out the pursuit. Difficulties of supply would have prevented the Indians joining the pursuing force immediately and, unless they departed soon, they could not reach the Sudan in time for an offensive timed for early February. Therefore, on 14th December the 4th Indian Division left the battlefield for Maaten Bagush, leaving the 16th Brigade in occupation of Sidi Barrani.

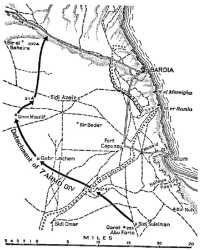

Meanwhile the 7th Armoured Division, with no more infantry than its Support Group contained, continued to press the retreating enemy. On the 12th December the headquarters of the division was eight miles east of Sofafi, its 7th Brigade in the Buqbuq area, the Support Group in the Sofafi area, and the 4th Brigade, pursuing the enemy north-west, had reached Bir el Khireigat. The armoured cars of the 11th Hussars were in contact with the Italians on a line from Halfaya Pass to Sidi Omar, where an enemy rearguard was resisting strongly.

Next day plans were made to cut the road from Bardia to Tobruk and thus isolate the garrison. An advance-guard of the division, consisting of part of the ubiquitous 11th Hussars, part of the 4th Royal Horse Artillery and a squadron of tanks, advanced through Qaret Abu Faris, Gabr Lachem, Umm Maalif, crossed the Trigh Capuzzo (the track parallel to the main road and about fifteen miles south of it) at Point 211 and by 10 a.m. on the 14th its patrols were overlooking the Bardia-Tobruk road from Bir el Baheira, and cut telephone wires along it. By nightfall a strong detachment of the 4th Armoured Brigade, including the 2nd Royal Tank, had patrols on the main road. In the course of the day bodies of Italian troops were found by the 4th Armoured Brigade and the Support Group to be in Fort Capuzzo, Salum, Sidi Suleiman, Halfaya and Sidi Omar (which was surrounded).

On the 15th the enemy still held Sidi Omar, Fort Capuzzo and Salum. On the western flank the 7th Hussars found the Gambut airfield abandoned, but the 7th Brigade, advancing northward between Capuzzo and

Sidi Omar, reached the Trigh Capuzzo east of Sidi Azeiz, but their efforts to get astride the Capuzzo-Bardia road were held by strong artillery fire from a flank-guard evidently posted there to enable the forces in Capuzzo and Salum to reach Bardia. That night the 7th Brigade was on a general line Sidi Suleiman–Boundary Post 42–Bir Beder–east of Sidi Omar.

Thus, while the advance-guard was meeting little opposition from ground troops west of Bardia (though it was being subjected to frequent air attacks), in the Bardia-Capuzzo-Salum triangle the enemy was holding his ground. So severe became the air attacks and so difficult the supplying of the advance-guard that, on the 16th, 11th Hussars were withdrawn into reserve south of Sidi Suleiman, and the 4th Brigade took over the task of capturing Sidi Omar, which was taken that evening. Meanwhile, during the day the enemy withdrew from the Salum–Capuzzo–Marsa Er Ramla triangle into Bardia, followed by patrols of the Support Group; and at the same time he abandoned his posts along the frontier between Sidi Omar and Giarabub.11 By the night of the 16th he was concentrated within the Bardia fortress on the coast and at Giarabub far to the south on the edge of the Great Sand Sea.

–:–

It will be recalled that during October and November Hitler had continued to seek an agreement with Spain whereby she would cooperate in an attack on Gibraltar. In the opening days of December the German intentions for the late winter and early spring were to capture Gibraltar, then overrun Greece; later in the year they would take Egypt. However, on 7th December the wary Franco announced definitely to a German envoy that he could not take part in an operation against Gibraltar on 10th January, as planned; he feared that, if he did so, Britain would occupy his African colonies; he lacked supplies, and his forces were unready. Thereupon Hitler cancelled the orders for the Gibraltar operation and advised Italy to go on the defensive in North Africa, where she had

planned to resume her advance towards the end of December. Thus, when the British offensive in the Western Desert opened, Hitler’s plans were again in the melting pot. The opening of that offensive was followed by a rapid series of German decisions. First, on 10th December, Hitler ordered (Directive No. 19) that plans be made to occupy Vichy France; secondly, on 13th December, he ordered (Directive No. 20) that the invasion of Greece was to take place probably in March; thirdly, on 18th December, he issued Directive No. 21 (“Barbarossa”), which required that preparations “to overthrow Soviet Russia in a rapid campaign” should be completed by 15th May. A decision to attack Russia in the spring of 1941 had been made by Hitler on 31st July 1940. The issue of Directive No. 21 was a further step in a program already arranged.

The British and Greek successes greatly disheartened Hitler’s naval advisers, who had persistently urged that an Axis offensive in the Mediterranean was essential (and were alarmed by the decision to attack Russia). On 27th December Admiral Raeder reported to Hitler:–

The enemy has assumed the initiative at all points and is everywhere conducting successful offensive actions – in Greece, Albania, Libya and East Africa. ... The decisive action in the Mediterranean for which we had hoped is ... no longer possible.