Chapter 9: The Capture of Tobruk

Before Bardia fell General Wavell had decided that Tobruk also should be taken, partly because the possession of that port would ease his supply problems. Lack of vehicles and the consequent shortage of food, water, ammunition and petrol in the forward area was a cause of anxiety to the British staffs. To an extent the advancing army was living on the country; it was employing captured vehicles and consuming captured petrol and rations, but these were dwindling assets and if the harbour of Tobruk was secured most of the needed supplies could be carried forward from the base in Egypt by sea. It was with the object of advancing swiftly on Tobruk as soon as Bardia had fallen that General O’Connor had sought to keep the 19th Australian Brigade out of the fight there and ready to move forward promptly with the armoured division.

However, within a few days after the fall of Bardia Wavell received a warning from London that a halt might soon be called to the advance through Cyrenaica. On 6th January Mr Churchill wrote for his Chiefs of Staff an appreciation of “the war as a whole.”1 In the course of it he said that when the port of Tobruk had been taken it should become a main supply base for the force in Cyrenaica, and land communications with Alexandria dropped “almost entirely.” For a striking force in Cyrenaica, he wrote, “the 2nd and 7th British Armoured Divisions, the 6th Australian Division, the New Zealand brigade group, soon to become a division, with perhaps one or two British brigades ... should suffice to overpower the remaining Italian resistance and to take Benghazi ... With the capture of Benghazi this phase of the Libyan campaign would be ended.” It would suffice for the general strategy if Benghazi was occupied “at any time during March.” In other words Churchill considered that a force twice as large as that already deployed in Cyrenaica would be needed to take Benghazi, and beyond Benghazi there should be no further advance. Churchill now had information from Madrid that it was unlikely that Spain would ally herself with Germany and he had informed Marshal Petain, the head of the Vichy French Government, that if France resumed the war against Germany using her North African colonies as a base, Britain would reinforce her with up to six divisions and naval and air forces. Two other irons were in the fire: the British Chiefs of Staff were studying a plan for the invasion of Sicily and, Churchill said, should the Greeks be checked in Albania there would probably be immediate demands from that quarter for more aid. He continued:

All accounts go to show that a Greek failure to take Valona will have very bad consequences. It may be possible for General Wavell, with no more than the forces he is now using in the Western Desert, and in spite of some reduction in his Air Force, to conquer the Cyrenaica province and establish himself at Benghazi; but it would not be right for the sake of Benghazi to lose the chance of the Greeks

taking Valona, and thus to dispirit and anger them, and perhaps make them in the mood for a separate peace with Italy. Therefore the prospect must be faced that after Tobruk the further westward advance of the Army of the Nile may be seriously cramped. It is quite clear to me that supporting Greece must have priority after the western flank of Egypt has been made secure.2

On 8th January, after learning from the Foreign Minister, Mr Eden, that it appeared that the Germans were hastening preparations to invade Greece, the Defence Committee in London agreed that “in view of the probability of an early German advance into Greece through Bulgaria it was of the first importance, from the political point of view, that we should do everything possible, by hook or by crook, to send at once to Greece the fullest support within our power.”3 On the same day, Churchill records, the veteran and influential South African leader, General Smuts, expressed to him the opinion that the advance in North Africa should terminate at Tobruk, and steps be taken to assemble a strong army against a possible German advance through the Balkans.

On 6th January Churchill had contemplated concentrating the equivalent of four divisions in Cyrenaica for a leisurely advance on Benghazi during the following two or three months. On the 8th, however, “the Chiefs of Staff warned the commanders in the Middle East that a German attack on Greece might start before the end of the month”, and added that as soon as Tobruk had been taken all operations in the Middle East were to be subordinated to sending the maximum help to the Greeks. The Middle East commanders were to inform the Greek Government of this decision and offer them a reinforcement. Wavell and his colleagues in the Middle East submitted that the German concentration in Rumania might merely be a bluff designed to cause them to halt the advance in Libya. Churchill thereupon, on 10th January, sent Wavell a cable repeating that his information indicated that the Germans would move through Bulgaria before the end of January and requiring Wavell’s “prompt and active compliance” with the decisions of himself and the Chiefs of Staff.

The aid which the Chiefs of Staff proposed to offer the Greeks at this time – a force of not more than one squadron of infantry tanks, one regiment of cruiser tanks, ten regiments of artillery and five squadrons of aircraft – was so small and ill-balanced that it is difficult to comprehend, first, why they believed it might achieve any effective results in Greece, and, second, why its subtraction from the forces in Africa and Palestine should necessitate halting the advance in North Africa at Tobruk. However, Wavell and Longmore hastened to Athens to make the offer. There, on the 14th and 15th, they conferred with the Greek leaders, who declined the proposed contingent on the grounds that “while hardly constituting any appreciable reinforcement for the Greek forces, would, on the contrary, if known to the Germans, provide the latter with a pretext for attack and hasten their advance through Bulgaria with a view to assailing us.”4

In consequence of this refusal Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff decided to continue the advance to Benghazi and on the 21st January informed Wavell that the capture of that place was now of the highest importance.

–:–

During these exchanges, which thus proved sterile, General O’Connor’s preparations to capture Tobruk continued. Documents captured at Bardia and interrogation of prisoners had given him a fairly clear picture of the garrison of Tobruk. On 15th January it was estimated to comprise 25,000 men, including General della Mura’s 61st (Sirte) Division, two additional infantry battalions and 7,000 garrison and depot troops with some 220 guns, 45 light and 20 medium tanks, the whole force being under the command of General Petassi Manella, the commander of the Italian XXII Corps. Farther west (he believed) was the XX Corps, with the 60th (Sabratha) Division probably at Derna, an armoured force under General Babini at Mechili and, perhaps, the 17th (Pavia) Division in the Benghazi area.

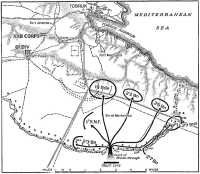

Two main routes led westwards from Bardia to the Tobruk area. As close to the sea as the deep coastal wadis would allow travelled the straight bitumen road to Tobruk itself. Some ten miles farther inland, and above an escarpment that rose about 500 feet above sea level, ran the track from Capuzzo to El Adem, an airfield eight miles south of the Tobruk defences. General O’Connor ordered the 7th Armoured Division to

advance along the Capuzzo track, and the 6th Australian to move parallel to it along the main road. Consequently, on the morning of 5th January, before resistance had ceased at Bardia, the 7th Armoured Brigade had moved westward, occupied the airfield at El Adem without opposition, and probed to Acroma seeking a suitable area in which to cut the enemy’s communications. The 4th Armoured Brigade followed as far as Belhamed; the Support Group to a concentration area south of the Capuzzo track about twenty miles farther east.

Next day patrols of the 7th Armoured Brigade reconnoitred the Tobruk defences and were shelled by Italian guns; twenty miles south of El Adem

the 11th Hussars found the Bir el Gubi airfield unoccupied and patrolled thence to Bir Hacheim. A regiment of tanks and a company of infantry occupied Acroma, at the top of an escarpment leading down to the main road west from Tobruk, which was then virtually encircled.

In Bardia, while the last Italian prisoners were being collected and the booty was being counted, Mackay ordered the 19th Brigade, with his cavalry squadron, two artillery regiments and the Northumberland Fusiliers to advance to Tobruk. Reconnaissance parties moved forward on the morning of the 6th and established touch with the British armoured force astride the main road, and in the evening the main infantry column advanced, being carried in trucks of the 4th New Zealand Motor Transport Company. Before midday on the 7th the infantry had deployed opposite the eastern face of the Tobruk defences, the 2/4th Battalion on the right with its right flank about 1,000 yards from the coast, the 2/8th in the centre and the 2/11th on the left. There they came under sharp artillery fire, the enemy using air-burst shells. On the night of the 8th the three battalions of the 19th Brigade moved forward until the 2/4th was on the western bank of the Wadi Sidi Belgassem; that night a patrol of the 2/11th reached the anti-tank ditch in front of the Italian posts.

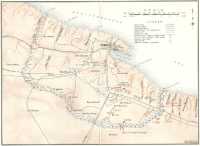

At Tobruk as at Bardia the flat hard floor of the desert slopes down towards the coast in a series of low escarpments lying from east to west. The coast itself is broken by deep north-south ravines two to four miles in length and so close to one another that the intervening land is often a mere ridge. Near Tobruk the Bardia road, skirting the ends of these coastal wadis, enters the fortress area about two miles and a half from the sea. Except for scattered clumps of camel bush the flat desert is bare of vegetation though near the mouths of some wadis a few palm trees grow.

As at Bardia the Italian defences consisted of a semicircle of concreted underground posts behind barbed wire entanglements five feet high. Outside this was an uncompleted anti-tank ditch; patrols were to discover that for four miles east of the El Adem road it was very shallow and on the western face of the defences there was no ditch at all, though a deep wadi served the purpose. Again the posts were two deep, each inner post being midway between two outer posts, and each outer post protected by its own anti-tank ditch and wire. The outer posts were generally 600 to 800 yards apart and the inner line 500 yards behind the outer. Whereas there were eighty posts along the seventeen-mile perimeter at Bardia there were 128 along the thirty-mile front at Tobruk. Thus, as long as the armoured division could fend off the Italian forces to the west – and so far the Italian commanders had seldom attempted a counter-attack – the task of the Australian division at Tobruk might be easier than at Bardia the line being longer and the garrison smaller.

But the attack could not be launched immediately, because it would take at least a week to bring up enough ammunition and other supplies to ensure success, and O’Connor would not risk his lightly-armoured tanks against the Italian guns and mines lest the consequent casualties rob him of his already-dwindling mobile striking force which would be needed

later.5 The destruction of the isolated garrison would again have to be carried out by the infantry, with the support of the greatly-reduced battalion of heavy tanks.

The advance to Tobruk had been fast enough to outstrip a rabble of Italians who had escaped from Bardia and set out to walk to the next fortress, marching by night and hiding in the coastal wadis by day. Between the 7th and 10th, for example, engineers of the 2/8th Field Company at work behind the 19th Brigade collected twelve Italian officers and 650 men. The 17th Brigade, in reserve from 10th to 17th January, was given the task of systematically searching the wadis, and there found more fugitives. Others were rounded up by Bedouins sheltering their flocks in the wadis. They stripped the Italians of their weapons and any other useful possessions they carried and, having no more use for them, marched them to Australian posts along the main road, and particularly to a conspicuous road house near Gambut where No. 3 Squadron RAAF had its headquarters. As late as 9th January the 2/4th collected in the Wadi Ueddan twenty-nine prisoners who, having walked seventy miles, were only a mile short of the imagined safety of the Tobruk posts. On the following day patrols of the 17th Brigade brought in fifty-three Italians, and on the 12th January five more. These last said that they had left Bardia two days after the battle ended.6

The campaign was going so well that senior officers became worried by signs of what Mackay described as a “picnic spirit”. In a sharp message to the units he said: “Civilianism is beginning to break out”, and he complained of “promiscuous firing of rifles and exploding of bombs”, of “dressing in articles of Italian uniform like clowns and not like soldiers”, of “collecting of dogs and looking after dogs instead of men” and of “fraternisation with prisoners.” “We must keep our heads and maintain perspective and poise,” he concluded. “If we do not we shall quickly lose efficiency and slip to the level of the foe we are hoping to defeat.”7

Mackay was a stern moralist, intolerant of any lapse from the highest standards of soldierly conduct. It was true that the men were experimenting and sometimes played dangerously with captured weapons and vehicles (one battalion complained of its neighbour’s “over-enthusiastic tendency to shoot gazelles”), but on the other hand it was also true that this very curiosity increased the men’s knowledge of unfamiliar equipment and added to their armoury, because they were now using a useful quantity of

captured gear, including even mortars and anti-tank guns. There had been some waggish wearing of Italian clothing, but the reason that, in some companies, half the men were wearing Italian boots, and Italian groundsheets were prized, was that the men had worn out their own boots and the light Italian groundsheet served as a useful tent.

The men (as Mackay and his staff were aware) were living under extremely arduous conditions. They slept in holes dug in the stony ground, and these were their only protection against intermittent shell fire and the wind and dust. As at Bardia the thermos bombs which the Italians had scattered round the perimeter were a constant anxiety. The nights were not so cold as at Bardia, but the dust storms were far more severe. Water was rationed to half a gallon a man daily, until a supply of washing water was found at El Adem and each man was allowed three-quarters of a gallon a day for washing himself and his clothing.8 Mess and kitchen gear had to be cleaned with sand. No “canteen goods” were available to vary the monotonous food, but there was tobacco and some units had supplies of captured tinned tomato and tinned veal. “Desert sores” began to appear on hands and faces. Fleas and, in a few units, lice picked up in the ill-kept Italian dugouts at Bardia were a minor torment. In these weeks a few men chose to wound themselves rather than continue to endure the discomforts and dangers.

The 16th Brigade went into the line on the left of the 19th on the night of the 9th–10th January. Each night, on the five-battalion front9 extending nine miles from the coast to the neighbourhood of the El Adem road (whence the 7th Armoured Division took over) each battalion would send out one or two patrols to find and measure the anti-tank ditch or perhaps to creep beyond it to the wire entanglements. Sometimes the Italians would see the scouts (the moon was full on 13th January and rose at 5.50 p.m.) and a patrol might have to lie still under furious fire for half an hour before making its way home.

On the 9th Brigadier Robertson ordered Lieut-Colonel Dougherty of the 2/4th Battalion to advance by night from the Wadi Belgassem, try to penetrate the defences with strong fighting patrols and, if he succeeded, follow up with the remainder of the battalion, except one company left in reserve. However, after a night advance over very rough country, the fighting patrols were halted by very heavy fire as they approached the Wadi Zeitun on whose far bank were the Italian posts.

On the night of the 11th–12th a patrol of the 2/1st, led by Lieutenant Rogers, stalking cautiously towards the ditch near the left of the line, set off some booby traps, and Rogers and one of his men, Private Pearson,10 were wounded. The survivors managed to carry the wounded men off under cover of a scurry of dust before an Italian patrol reached them, but this incident revealed a hazard not present at Bardia. The following

Italian booby traps

night a patrol from the neighbouring battalion, the 2/3rd, also ran into booby traps. Corporals Best11 and Doyle12 were scouting 300 yards ahead of twenty men commanded by Lieutenant Gibbins13 when there was an explosion and they were hit in the legs. There was much artillery fire at the time and the main body of the patrol did not know that anything was amiss until they heard Best calling for help. Two men crept forward and the wounded men were carried back 1,200 yards on stretchers improvised by slinging coats over rifles. The following night a party of engineers went out with a patrol of the 2/3rd to find the traps and discover how they worked. They found a line of booby traps about 100 yards in front of the anti-tank ditch, the traps ten feet apart and joined by a green trip wire six inches above the ground. When kicked, the trip wire pulled a trigger and detonated an explosive in a cannister measuring ten inches by two and a half and filled with small fragments of metal. The engineers brought some of these booby traps back and discovered that they could be made safe – “deloused” was a favourite term – by putting a small nail through a hole in the firing pin to keep it in place and then removing the firing cap.14

On the night of the 15th–16th Lieutenant Eckersley15 of the 2/8th Field Company led a three-man patrol against the Italian line opposite the 2/11th Battalion. When they reached the anti-tank ditch there was a series of explosions and they believed that they were being attacked with grenades. Sapper Kendrick16 was wounded mortally; the other three, though wounded, managed to get back. After the battle Kendrick’s body was found and there were signs that the damage had been caused not by grenades but booby traps.

Thenceforward leading scouts would move forward cautiously as they neared the ditch, holding in front of them a thin stick with which to feel the trip wire without setting off the traps. Patrols discovered a continuous

line of these devices for 6,000 yards along the front, including the area of Posts 55 and 57 where the anti-tank ditch was shallow. Finally, on the night of 15th–16th January, two engineer lieutenants, Beckingsale17 and Gilmour,18 were sent to plot accurately the position of these posts, the wire, the ditch and the minefield in the vicinity. They spent the night making careful measurements and taking bearings.

–:–

These patrols were an outcome of a decision announced to the brigade commanders at a conference on 13th January to attack near Post 57. Two days earlier Mackay and Berryman had indicated a special interest in the Bir el Azazi area. Allen had been ordered to extend his line to the left, and to move it forward to about 3,000 yards from the perimeter, with a defended locality about 1,000 yards from the enemy’s posts near Bir el Azazi. Both forward brigades were instructed to explode two Bangalore torpedoes in the Italian wire each night, but not to do so near Post 57. At the same time, also to deceive and weary the enemy, five-minute bombardments were fired at various parts of the Italian line each night.

General O’Connor was anxious to use his armoured division to advance to Mechili. The Support Group now occupied a line from Acroma to the sea with the 4th Armoured Brigade protecting its right and the left of the 6th Division; the 7th Armoured Brigade and the 11th Hussars guarded against an enemy approach from the west along either the northern or the southern road. From 15th January onwards armoured patrols had found Bomba and Tmimi unoccupied and had approached Mechili which appeared to be occupied by a force about 400 strong. When it became apparent that supplies and fuel needed for a move against Mechili could not be assembled before 20th January, and in response to Mackay’s request that the armoured division should press in on Tobruk from the west while he attacked in the south and that its artillery should assist in the bombardment, O’Connor agreed to postpone the advance on Mechili until after the attack. Henceforward, the commanders believed, the speed and extent of the advance would be governed less by the resistance of the enemy than by the corps’ ability to keep its vehicles in working order and to bring supplies forward. Spare parts for vehicles of all kinds were short, and the Australian trucks were being maintained by a process which Mackay named “cannibalisation”. Within a few hours of a vehicle breaking down and being abandoned by the road it would be dismantled by passing drivers, one removing a wheel, another a spring, another a piston and so on until only a skeleton remained. It was a rough-and-ready system and was sharply criticised by staff officers who were unaware of the extent of the shortage, of the high pressure under which drivers were working, and the degree to which the force was then compelled to rely on captured transport.

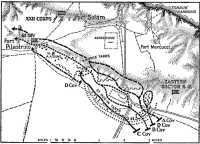

Again General O’Connor’s plan for the capture of the fortress was that the armoured division should demonstrate but not commit itself while the infantry division attacked, split the Italian perimeter and fanned out within it. When the infantry had taken Tobruk, the armour, its dwindling strength conserved, could thrust towards Mechili and farther west, the infantry division making the best speed it could on the coastal flank. After discussions with O’Connor and his staff, whose headquarters had been at Gambut since the 7th, and with Creagh of the armoured division, Mackay assembled his brigadiers and Jerram of the 7th Royal Tanks on 17th January, and outlined a plan of attack. The first move, he said, would be to form a bridgehead so that the tanks could enter the perimeter. He wished to “bite deeply into the defences and get at the enemy artillery early” (failure to do this had been one cause of the local set-back at Bardia). At the same time he wished to capture the sectors to the east of the tank bridgehead in order to make additional entrances on that flank, and particularly along the main road.

Again, he said, one battalion of the 16th Brigade would establish the bridgehead. It would then swing west, supported by a troop of tanks. A second battalion, with more tanks, would capture the perimeter up to the Bardia road, and the third, with tanks and cavalry carriers, would penetrate deeply and overcome a number of field and anti-tank batteries in the area between the Bardia and El Adem roads. The 17th Brigade was to mop up the eastern sector, and the 19th Brigade to move into the perimeter through the 16th and advance northward deep into the fortress area. At the end of the day, the 19th Brigade was to be on the forward slope of the escarpment overlooking Tobruk with the 17th on its right and the 16th facing west on its left. General O’Connor had decided that the role of the armoured division would be to demonstrate against the western half of the defences, where, for four days before the attack opened, the Support Group would carry out a program of harassing fire with artillery and small arms. At this conference Jerram spoke frankly about the employment of his tanks at Bardia, saying that some had been improperly used to carry out wounded and for other non-essential tasks and this had hampered their use in support of the 17th Brigade.

Thus, in its main features, the plan resembled that employed at Bardia – penetration of the line by a dawn attack on a small front to open a gate through which infantry and tanks could enter and fan out within the Italian area; both plans provided for pressure on the enemy’s left flank in order to suggest that attack was to come from that direction; a stealthy night movement to the left of most of the artillery on the eve of the attack. The point of attack was to be at the junction of two sectors (as revealed on captured maps) in the hope that, in the early stages, the enemy commander, receiving reports that two sectors were under attack, would conclude that the advance was on a wider front than was actually so.

General O’Connor had instructed General Mackay that the attack be made on the 20th, but Brigadier Allen asked that it be postponed until the 21st to allow him more time for his preparations and because an additional

day might enable the 7th Royal Tanks to put more of their tanks in working order – on the 17th Jerram could promise that only thirteen of them would be fit for action on the 18th. O’Connor agreed to the postponement, although for two main reasons he was anxious to press on: firstly, because fresh Italian divisions were believed to be arriving at Tripoli and secondly, because he knew that plans were being made to send reinforcements to Greece, and it was likely that this venture would reduce the already inadequate trickle of supplies to the desert force.

The estimate of the Tobruk garrison was not materially altered between the 5th and the 20th: 25,000 troops, including the 61st (Sirte) Division, the artillery regiment of the 17th (Pavia) Division and two additional battalions; 232 heavy, medium and field guns, 48 heavy anti-aircraft guns, 24 anti-tank guns, 25 medium and 45 light tanks. It was believed that the headquarters of the 17th and 27th (Brescia) Divisions were at Derna and the 60th Division was assembling there; at Mechili was a brigade of some 60 medium tanks. Most of the 17th Division was believed to be at Benghazi and the other formations remaining in Tripolitania – 25th (Bologna) and 55th (Savona) Divisions were believed to be moving towards Cyrenaica. Thus, unless the advance was hastened, there might soon be four fresh enemy divisions and an armoured brigade deployed between Derna and the Gulf of Sirte. Meanwhile O’Connor’s armoured strength was declining. On 16th January there were only 69 cruiser, 126 light, and 12 infantry tanks ready for action. Between 17th and 20th January the 3rd and 7th Hussars and 1st and 2nd Royal Tanks were brought up to strength by taking over the tanks of the 8th Hussars and 6th Royal Tanks, whose men were withdrawn from the forward zone, again reducing each armoured brigade to two instead of three regiments.

Detailed orders for the attack provided that the following units would be added to Allen’s command in the initial stage: 2/6th Battalion, 1/Northumberland Fusiliers (minus one company), three troops of the 6th Cavalry, “J” Battery Royal Horse Artillery, and the 2/1st Field Company. Before moonrise (1.10 a.m.) engineers would move forward and disarm the anti-personnel mines on a front of 800 yards. At 5.40 the artillery barrage would begin and the 2/3rd Battalion with the 2/1st Field Company would cross a start-line 1,000 yards from the Italian posts. The engineers, with the infantry pioneers, would blow holes in the enemy’s wire and begin making five lanes for vehicles over the ditch and through the wire. At 6.5 a.m., when the barrage lifted, the 2/3rd would advance and take Posts 57, 55, 56, 54 and 59. Thenceforward, at short intervals, tanks, cavalry, artillery and infantry would advance through the gap until, within three hours, eight battalions, all the tanks and cavalry and several troops of artillery would be within the perimeter. Thus, at 6.45 a.m., one troop of tanks would pass over the crossings in the anti-tank ditch to support the 2/3rd in an advance westward along the perimeter posts, the 2/1st Battalion would enter and, with a second troop of tanks, would march along the perimeter to the right. Then the 2/2nd Battalion would cross the ditch, and, with three troops of tanks, would advance

The plan of attack

north-east, north and north-west to capture the Italian batteries on the flat ground between the Bardia and El Adem roads. By 7.30 the 2/6th Battalion, machine-gunners, cavalry and artillery would be fanning out within the perimeter; and at 7.55 the 19th Brigade would enter to thrust northwards quickly, occupy the edge of the escarpment leading down to the town and be ready to exploit westwards.

Again Savige’s brigade was to be split up. The 2/6th would be under Allen’s command in the early stages19; the 2/7th was to enter the perimeter and relieve the 2/1st on its objective, when it and the 2/6th would revert to Savige’s command. His third battalion, the 2/5th, would be in support just south of the Bardia road. To enable Savige’s battalions to be thus concentrated nearer the battle, the right of the Australian line was left occupied only by a company of machine-gunners and a few small detachments of the 2/5th, whose task was to make much noise with machine-guns, rifles and captured mortars, to fire Very lights and generally to give the impression that the area was strongly held.

Thus the role given to each brigade resembled that allotted in the earlier battle. To Allen’s rugged 16th which had been longest in the Middle East

was again given the task of punching a hole in the Italian line; Robertson’s 19th was to move fast and far and deliver a final blow; Savige’s again was to be used piece-meal, its component parts dispersed over a wide area.

For the coming battle Mackay, though he was weaker in infantry tanks, having eighteen as against twenty-eight at Bardia, had more artillery and an additional battalion of English machine-gunners – the 1/Cheshire. As well as his own two field regiments, the 2/1st and 2/2nd, plus one battery of the newly-arrived 2/3rd, he had one British medium regiment (the 7th) and a battery of another (the 64th), one field regiment (the 51st), the 104th and one battery of the 4th Royal Horse Artillery. From 5.40 a.m. eighty-eight guns of various calibres would concentrate on the enemy posts from 52 to 59 on a front of less than 2,500 yards. At 6.5 a.m. the fire would lift from Posts 55, 57 and 59 while the infantry attacked them, and concentrate on 53 and the posts in the inner line. After 6.20 a.m., for more than an hour some of the guns would fire on the Italian artillery, some would form a box of fire round the bridgehead and some would place a moving barrage in front of the infantry.

The advance by the 19th Brigade was to have formidable artillery support (lest the set-back to the second phase of the battle at Bardia be repeated). It would be assisted by the fire of fifty-two 25-pounders, sixteen 4.5-inch guns, two 60-pounders and eight 6-inch howitzers. Sixty-six of these guns would provide a preliminary barrage from 8.20 to 8.35; and from 8.20 until 9.35 fire was to be brought down on Italian battery positions and posts ahead and on the flanks. Each battalion of this brigade was to be accompanied by an observer from a supporting field regiment (or, in the case of the 2/8th, from “F” Battery, Royal Horse Artillery) so that fire could be concentrated on new-found targets. With the help of captured maps, aerial photographs and flash-spotting (taking bearings on the flashes of enemy guns and recording the time of flight of their shells) Brigadier Herring’s gunners had fixed the positions of the Italian batteries to ensure that accurate fire could be brought down on them on the critical day.

On the two nights before the attack squadrons of Wellingtons and Blenheims, which raided Tobruk regularly, dropped a total of twenty tons of bombs on the fortress. During the day of the attack Blenheim bombers of three squadrons were to make constant sorties over the enemy-held areas. Based at Gambut near O’Connor’s headquarters and directly under his command were No. 200 (Army Co-operation) Squadron, a flight of No. 6 (Army Co-operation) Squadron and No. 3 Squadron RAAF, which were to give close support.

As one consequence of the postponement of the attack not only were eighteen infantry tanks (not thirteen as had been feared) in working order on the 21st, but a small reinforcement of the division’s fighting vehicles came from another quarter. Before Bardia had been taken O’Connor had ordered that “A” Squadron of the 6th Australian Cavalry should equip itself with some captured Italian tanks. With great labour, because the Diesel engines of these vehicles were unfamiliar, sixteen

The attack on Tobruk. Situation at 11 a.m. 21st January

medium (“M11” and “M13”) tanks, each armed with a light gun and machine-guns, were put into working order and brought forward, and the single squadron, reinforced with men from the carrier platoons of infantry battalions, was expanded into three, one with six tanks and two each with nine carriers.20

An accident on the night of the 17th had made it additionally fortunate that Allen obtained a postponement. His newly-appointed brigade major, Knights,21 with Captain Hassett,22 adjutant of the 2/3rd, and other officers, and with Lieutenant Bamford’s23 platoon of the 2/3rd to protect them, had gone forward to mark a starting-line for the attack. The desert was almost featureless and, as at Bardia, the only way to ensure that the start-line was the correct distance from the objective was to find the Italian wire and carefully pace a line at right angles from it. After a long, stealthy march in the darkness all but two of Bamford’s men were left behind and they and the officers moved forward towards the Italian line. When they thought that they were still 300 yards from the booby traps there was a flash and two explosions; in quick succession, Knights, Hassett, Bamford and the two scouts (Privates Armstrong24 and Smith25) were wounded, leaving only three of the party unhurt. The wounded were brought in, but the start-line remained unlaid.

The following day (the 18th) Major Campbell, Allen’s brigade major at Bardia, and now on Mackay’s staff, returned to the brigade to lead the final patrols and lay out the starting-line as he had done at Bardia. On the night of the 18th–19th he went forward with three engineers under Sergeant Johnston who had taken charge of the bangalore party at Bardia and blown gaps in the wire for the infantry and tanks to pass through. When these four had marched by compass to within about 300 yards of the antitank ditch opposite Post 57, Campbell instructed the engineers to feel for the booby-trap string. After probing forward for about 150 yards the string was found and some traps disarmed without mishap. The patrol advanced to the ditch and along it to a point half way between Posts 55 and 57 (the gateways of the intended breach). Thence Campbell led the party back into no-man’s land, broke the line of booby traps again and moved 1,000 yards from the perimeter. Pieces of rifle-cleaning flannel were tied to a camel bush there to mark the centre of the start-line, and thence they moved back on a compass bearing for 2,000 yards, marking a bush every twenty-five yards or so with flannelette, until they reached the area chosen for the assembly of the assaulting force. There was no time to

delay as they had to be well away from the perimeter before the moon rose about 11 p.m. Although the Italians were unusually alert and fired bursts of machine-gun fire across no-man’s land they did not discover this vital patrol.

–:–

On 18th January the wind had blown so fiercely that it would pick up empty petrol tins and bowl them along, and dust made it impossible to see more than a few feet. On the 19th the dust was still thick but the 20th was clear and sunny. That night the 19th Brigade which had been relieved in the eastern sector by the 17th Brigade and had a day of rest and bathing, was concentrated east of the El Adem road, the 2/6th Battalion was moved in trucks to join Allen’s brigade, and the 2/5th moved to its area south of the Bardia road. The three battalions of the 16th Brigade concentrated in the darkness south of the point where they were to break through.26

Early in the night one group after another set off in the cold starlight towards the Italian line. About 11 p.m. Campbell led a party forward to mark with tapes the 2,000-yard route from assembly area to the centre of the start-line. Captain Buckley’s27 company of the 2/2nd Battalion accompanied them to protect the start-line, when marked, against possible Italian patrols. A section of engineers, under Lieutenant Cann, followed, and passed the start-line to clear booby traps on an 800-yard frontage. Campbell’s party and Cann’s stealthily withdrew when they had done their jobs, leaving Buckley’s company on guard.

The leading battalion, the 2/3rd, began to move forward from the assembly area at 3.30 a.m., with the engineers of the 2/1st Field Company who were to blow gaps in the wire and dig crossings in the ditch for the tanks to pass over. The engineers had been organised by Lieutenant Davey into five parties each of four of his own sappers and three men of the 2/ 3rd’s pioneer platoon. Each party was given three Bangalore torpedoes, two to use and one in reserve. Each torpedo was carried by two men, the seventh man in each team being an emergency. When, at 5.40, the guns opened fire and the leading platoons of the 2/3rd Battalion advanced from the start-line in single file, the engineers led the way, spaced so that they would meet the wire about fifty yards apart.

On the right of the line as it reached a point a few yards from the ditch there was a vivid flash and a series of explosions. Evidently men on that flank had veered too far to the right and the trip wire of a group of booby traps had been kicked.28 “It was quite a beautiful sight,” said one of the infantrymen afterwards. “In the flash you could see twenty or more men peeling back like a flower opening.” Three men were killed and

Lieutenant Donegan29 and seventeen others wounded, leaving only a section (under Sergeant Sayers,30 who was wounded but carried on) where there had been a platoon. One of the engineer parties was caught in this series of explosions (which they and the infantrymen at the time believed to be a salvo of shells from their own guns dropping short).31 Sergeant Williams32 of the engineers was killed and others were hit or thrown to the ground, including Private McBain,33 one of the infantry pioneers who, though dazed and wounded, struggled to his feet and alone dragged a torpedo forward to the ditch. Thus the torpedoes were carried forward on time to the twenty-foot wide wire and were slid under it. Then sappers and pioneers moved back into the ditch except five sergeants or corporals who crouched at the wire ready to light the fuses.

Suddenly a bugler blew a call at one of the Italian posts perhaps 400 yards away. Some feared that this was giving the alarm, but the call died away and there was no sign that the enemy, only fifty yards away, realised that it was more than a routine bombardment. The leading infantrymen were now in the ditch or sheltering behind the parapet on the southern side, tense and eager to begin the assault. Davey fired a red Very light as a signal to his engineers to light the fuses and hurry back into the ditch. Men of the two leading companies heard four bangalore torpedoes explode; then a fifth loud explosion. Shells were bursting at rapid intervals, some very close to the wire; the noise and the darkness combined to create a sense of confusion. Davey was moving along the ditch urging the men to keep under cover but Lieutenant Dennis Williams, a high-spirited young platoon commander, shouted: “Go on you bastards” and began to climb out of the ditch. Major Abbot shouted: “Dennis, come back.” The men heard and were in the ditch again when Colonel England appeared, saw some indecision, and shouted: “Go on, C Company!” Abbot hurried over to him and explained that the final bangalore had not exploded. “Come back, C Company,” shouted England. The engineers had now gone forward and made sure that clean gaps had been blown in the wire – but only four of them – and Davey gave the word to advance. Then the men literally ran forward. At Bardia they had been laden with greatcoats, leather jerkins, and at least fifty pounds of equipment, rations and ammunition; now they wore only jerkins over their uniforms, and carried only their weapons and ammunition and a filled haversack.

The survivors of the platoon which had lost more than half of its men on the booby traps, led by Sergeant Sayers, were on top of Post 57 before the Italians had emerged from their shelters and took the post without a shot being fired at them. At Bardia leaders and men had learned the value

of speed and they moved so fast that here and there they surprised not only the Italians but their own neighbours. Within a few minutes some confused firing was taking place round Post 56 between two platoons of Abbot’s company, each of which had overrun a forward post, a party from company headquarters under Sergeant-Major McGuinn34 and, least dangerous, the Italians themselves, about forty of whom were captured there. A section from Williams’ platoon advanced beyond the inner line and took more than 100 prisoners at a supporting position there. On the left Captain McDonald35 attacked Posts 55 and 54. As Lieutenant MacDonald’s36 platoon approached 55, which was 200 yards from the gap in the wire through which they had come and proved difficult to find in the darkness, he shouted “Mani alto!” and one of his men fired. These Italians were ready for action, however, probably because of the minutes MacDonald had lost finding his way in the darkness, and they began firing with all the array of weapons each Italian post possessed. Immediately the Australians charged forward. The leaders, including MacDonald, Sergeant Hoddinott37 and Corporal Foster38 ran on to the post’s anti-tank ditch, which was partly covered with thin planks, fell through them, and scrambled out again. Foster was killed and MacDonald wounded in the stomach but he (until he collapsed) and Hoddinott continued throwing grenades, until five more men in the platoon had been wounded by Italian fire. Hoddinott withdrew the twenty survivors about forty yards from the post, reorganised them and then led them forward again running as fast as they could and firing as they ran. When they reached the post they kicked aside the planks covering the manholes and dropped in grenade after grenade. Twenty-one dead Italians were counted in the post and three more were captured unwounded. The fight for Post 55 lasted more than half an hour.

Meanwhile Captain McDonald with Lieutenant Stanton’s39 platoon advanced to the inner post, 54. They found no sign of life there and had dropped in a few grenades when a runner arrived to report the set-back at 55. McDonald sent Stanton’s platoon to help at 55, but it was still so dark and so difficult to keep direction that these men, after cutting their way through a belt of wire and stumbling into a ditch, discovered that they had cut their way right out of the perimeter and were in the main anti-tank ditch outside it. Post 54 was evidently cleared eventually by Abbot’s company, which found every Italian still sheltering below ground except two who were dead – probably killed by Stanton’s grenades.

By 6.45 the 2/3rd had taken five posts round the bridgehead and, in the grey dawn, the leading troop of tanks began to lumber through the ditch followed by the leading companies of the 2/1st Battalion. Again the flank of one of the leading companies ran into Italian booby traps which disabled almost every man in the outer platoon. In half an hour the battalion formed up and was advancing eastwards along the perimeter, Captain Hodge’s company along the line of outer posts and Captain Miller’s40 along the inner, with the remaining rifle companies following to mop up. The attackers moved with the tanks at a steady two and a half miles an hour, subduing heavy fire at some posts, meeting no resistance at others. The tanks set the pace, and if the leading companies found a post slow to surrender they would drop grenades into it and leave the “mopping-up” to the following companies. At Post 74 they had to wait for the barrage to move on; thenceforward they were under fairly constant Italian artillery fire. At 9 o’clock they took Post 81, their objective, having advanced four miles and a half and taken twenty-one posts in two hours and a half. In their haste the rear companies failed to mop up one strong post – No. 62. The 2/6th Battalion, coming along about half an hour later, met heavy fire from this post, which contained the headquarters of the Bir Iunes sector. The Italians continued to fire despite bombardment by tanks and machine-guns until Lieutenant Clarke41 and his pioneer platoon, advancing cautiously, poured a mixture of crude oil and kerosene into the post and lit it. Eleven dead men were found and thirty-five surrendered. It showed (wrote one diarist) “what could happen if the enemy was determined”.

The 2/2nd Battalion, the next to move through the gap, had a difficult role, an improved version of that allotted to the unfortunate 2/5th at Bardia. It was to fan out after entering the perimeter, deal with three groups of Italian guns in the triangle formed by the perimeter, the Bardia road and the El Adem road, and thus remove a threat to the flank of the 19th Brigade which would follow. Mackay and Berryman, who realised the dangers, allotted Chilton of the 2/2nd a troop of tanks and arranged a series of artillery concentrations on successive battery positions timed to conform with the infantry’s rate of advance. Chilton, an exceptionally careful planner who liked to leave nothing to chance, had seen to it that his men had been instructed in their task on sand-table models. One rifle company had to advance along each of three lines of guns, and each company therefore had an independent role; in the absence of wireless communications within the battalion (the only means of communication was by dispatch riders mounted on captured Italian motor-cycles) little control could be exercised by the commanding officer once the battle started.

By the time the 2/2nd entered, a cloud of dust whipped up by bursting shells and the wheels and caterpillar tracks of trucks and tanks hung over

the gap in the Italian line. Into this fog the 2/2nd moved at a fast walk with the tanks following, and marched north for 2,500 yards. In the dust and the dim light, tanks and infantry failed to link at their pre-arranged rendezvous within the perimeter, and each advanced independently. Because of accurate artillery fire on the Italian batteries, the support of the tanks, and because the Italian gunners seemed less cool and determined than at Bardia, resistance was relatively light.42 Either tanks or infantry overran one battery after another until they had captured ten in all and, having marched and fought 3,500 yards in two hours and a half, tanks and infantry met on their objectives at 9.10 a.m., three of the infantry companies on the Bardia road, one on the El Adem road with, at that stage, a wide gap between.43 The 2/6th, entering behind the 2/2nd, came in on their right and, by 11 a.m., had advanced across the Bardia road and were in position between Points 121 and 116. Next a force consisting of the 1/Northumberland Fusiliers (minus two companies) with three troops of cavalry and one of the 3rd Royal Horse Artillery entered, took over the ground held by the left companies of the 2/2nd Battalion and filled the gap between it and the 2/3rd. Soon after 11 a.m. the 2/7th, which had marched into the perimeter at 8.25 a.m., near Post 65, with a company of the Cheshire (machine-gunners) replaced the 2/1st at Posts 81 and 85 on the right flank of the 2/6th.

When we left the 2/3rd Battalion at the bridgehead its leading companies had taken five posts-59 to 55 – and, with the engineers, had opened the gate for the tanks and the 2/1st and 2/2nd Battalions to enter. At this stage fresh companies, McGregor’s on the right and Lieutenant Fulton’s on the left,44 with a troop of tanks, passed through the now-depleted companies that had fought for the bridgehead. The tanks helped to take Post 52, and then McGregor’s company deployed and advanced north-north-west on a 700-yard front leaving the inner line of posts on their left. They moved forward without great opposition, capturing 300 Italians, until they were overlooking the El Adem road from relatively high ground, where they remained until the early afternoon sniping at Italian batteries on the opposite side of the road. Meanwhile Fulton’s company which had one tank to support it quickly took Post 53. The tank then moved against the inner posts and the infantry took 51 and 49 alone.

Thence McDonald’s company took over with two tanks to help it. At the next two posts the tanks subdued the Italian fire and the infantrymen, following close behind, threw in grenades or fired a few rounds from a Bren gun. If the Italians did not then climb out, their hands over their

heads, an infantryman jumped down into the post with a warning shout45 to ferret the garrison to the surface, whereupon the loose planks covering the trenches flew apart and twenty or thirty Italians clambered out. At 9 a.m., McDonald, when nearing Post 45, came under accurate artillery fire from guns beyond the road. One shell broke the track of a tank; McDonald withdrew his men round Post 44 (which was his objective), and the infantry and damaged tank remained under intermittent fire from artillery and posts ahead for four hours.

–:–

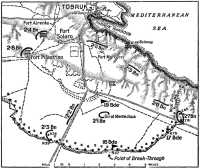

While the battalions under Allen’s command were fanning out, the 19th Brigade marched through the gap which they had made and drove deeper into the Italian position. It moved from its start-line some 5,000 yards within the perimeter at 8.40 a.m. The crust of the defence had been broken and in its first phase Robertson’s advance went precisely according to plan. Behind the fire of seventy-eight guns from 25-pounders to 6-inch howitzers, the three battalions moved fast and in open order. The barrage advanced 200 yards each two minutes and the men had been schooled to keep close to it. On the right the 2/11th Battalion reached its objective on the top of the escarpment beyond the Bardia road without a casualty. As it neared the road, the 2/4th, which advanced with a detachment of the divisional cavalry on each flank and was forward of the other battalions, came under machine-gun fire from Italian positions near the road junction. Captain Pinniger,46 commanding the left forward company, was hit and both his legs were broken, but he ordered stretcher bearers to carry him forward to catch up the battalion. They did so, but when they reached Dougherty’s headquarters he ordered that Pinniger be taken back to the field ambulance. The Vickers guns with the battalion temporarily subdued the enemy fire and the battalion went on, captured the sector headquarters which was established in dugouts about 1,000 yards beyond the road and established itself on the upper shelf of the escarpment while patrols descended on to the next shelf.47

The fire from the left, however, hit the 2/8th Battalion far harder, and before the Victorians had reached the road it was apparent that any serious trouble encountered by the brigade would come from that quarter. Aerial photographs and captured maps had shown that an anti-tank obstacle had been thrown round the eastern side of the road junction and west of it was a strong group of batteries. The map suggested that the Italian commander, in preparation for a possible break-through east of the El Adem road, had begun a second line of defence protecting the road junction, his own headquarters at Fort Solaro, the sector headquarters at Fort Pilastrino and the town itself.

The 2/8th Battalion advance on Fort Pilastrino, January 1941

The troop of cavalry with carriers and one tank which was leading the 2/8th on the left came under this fierce fire and answered it. Campbell’s48 “C” Company following behind swung left towards the fire while the other three rifle companies kept moving to the objective. At first Campbell thought that he was tackling a small group of machine-gun posts, but soon could see that he faced ten or more stationary tanks which had been dug into the ground and were firing with the twin machine-guns they carried in their turrets. The company lay waiting for an artillery concentration to be brought down on the tanks, but seeing a platoon from “D” Company (Smith’s49), which had become split during the left wheel, going straight into the attack on the right so that artillery fire was impossible without endangering them, Campbell attacked too. There followed a series of fierce fights between the infantrymen with their small arms, anti-tank rifles and grenades and the Italian tank-blockhouses. Lieutenant Gately’s50 platoon took three of them, then lay and fired while Lieutenant Anderson’s51 platoon leap-frogged forward and overran another group. Lieutenant Russell’s52 platoon on their left fired two anti-tank rifles with

good effect. Thence Gately and Anderson attacked in turns along the line of tanks, each fifty to 100 yards from the other, the line extending west for about 1,500 yards and evidently intended to meet attack from the south not the east.53 In each fight the crews fought with determination, and did not give in until the attackers were at close quarters. Sergeant Burgess54 ran forward to one of the tanks and was trying to heave up the lid to drop in a grenade when he was hit by several bullets. “His last effort before he died,” wrote one diarist, “was to struggle to put the pin back and throw the grenade clear of his comrades.” Fourteen tanks were stormed, few prisoners being taken, and the remaining eight surrendered. Captain Robertson55 and Lieutenants Anderson and Russell were wounded, Anderson mortally; only one sergeant in the company remained unwounded when the fight was over.

The remaining two companies (Major McDonald56 and Captain Coombes57), which had wheeled and were now in the centre of the battalion’s advance, came under fire from dug-in tanks on the right of those Campbell’s company had attacked and began to suffer casualties. They fired on the tanks until the Italians closed down their firing slits, and then they charged with bayonet and grenade. McDonald’s company had overrun a large building near the road junction. Coombes’ company crossed the El Adem road, captured a group of mobile tanks and reached the edge of the first escarpment leading down to Tobruk. Here they encountered a group of machine-guns in sangars. Lieutenant Phelan,58 the impetuous leader of the carrier platoon, led some carriers round the right flank here and took a sand-bagged emplacement at pistol point while the rifle company, supported by skilfully-directed overhead fire from a platoon of the ubiquitous machine-gunners of the Northumberland Fusiliers, pressed on and took the remaining positions. Before the attack had lost its impetus the leading men had captured some concrete dugouts which were discovered to be an artillery headquarters and from which emerged General Umberto Berberis and his staff. Coombes’ company had now taken more than 1,000 prisoners. The battalion had reached the edge of the escarpment from a point north of the road junction to a distance of two miles to the west. Coombes, his men having almost exhausted their ammunition, decided that he was dangerously far ahead of the company on his right and halted until a truck carrying 5,000 rounds reached him. The main body of Smith’s company had followed this advance and run right into by-passed Italians who were just recovering their breath. It too had some hard fighting.

As soon as the 2/8th became committed to this long fight Robertson decided to carry out the second phase of his advance – to exploit westward to Forts Pilastrino and Solaro. The 2/8th was to take Fort Pilastrino, the 2/4th Solaro, and the 2/11th to seize the escarpment overlooking Tobruk Harbour from the south. The renewed attack would begin behind artillery fire at 2 p.m.

Lieut-Colonel Mitchell of the 2/8th now divided his battalion into two groups: “A” and “B” Companies on the right under Major McDonald, and “C” and “D” (“D”, which had been divided, was now concentrated on the right flank) on the left under Major Key.59 The right column would move along the edge of the escarpment, the left over the flat ground with the road as its axis of advance, and both would thus converge on the Italian headquarters of Pilastrino.

The advance was being resumed when the line ran into a well-organised counter-attack by nine medium tanks followed by some hundreds of Italians on foot. The infantry fought back with anti-tank rifles and stopped several of them. Private Neall,60 in Campbell’s company on the left, knocked out the three leading tanks with an anti-tank rifle, causing the remaining six to circle defensively, but not before they had overrun a section of the company and forced it to surrender. The remainder of the company took shelter in such shallow trenches and dips as the country offered. Under sharp fire Private Passmore61 also engaged enemy tanks with an anti-tank rifle and disabled some of them. Colonel Mitchell who was close to the forward troops and had some British anti-tank guns nearby, sent them forward and they hit two more tanks, but the situation was still dangerous when two infantry tanks arrived. The Italians, seeing these formidable machines advancing, turned about and fled, and the entire front line of the battalion charged forward in pursuit. In the affray Captain Campbell, the very gallant leader of the company, was fatally wounded, and Lieutenant Van Citters,62 a fine young Englishman who had brought his pioneers into the thick of the battle, was killed. Only Lieutenant Gately, one sergeant, one corporal and nineteen men then remained. With this handful Gately reported to Coombes and they became part of that company for the remainder of the battle.63

The other companies, too, were becoming seriously depleted and orders had now been given that fit men were not to be sent back with prisoners or wounded, but that the wounded were to be left where they fell, their position being marked by a rifle with bayonet fixed set upright in the ground beside them. Although the Italian counter-attack had been dispersed,

the fire from front and flanks became hotter and Mitchell delayed further advance for about an hour, when it abated, probably because of the success of the 2/4th against the Italian artillery on the right flank.

Continuing the advance, McDonald’s companies fought their way with Bren and grenade, under continuous artillery and mortar fire, from sangar to sangar along the edge of the escarpment. At one stone wall the Italians threw grenades until the last yard, then flung up their hands; and one threw a grenade from among his surrendering comrades and killed an Australian. A Bren gun was fired into the others killing twenty (according to one observer). In the advance Lieutenant Trevorrow64 and Sergeant Duncan,65 an outstanding leader, were wounded; two of the platoon commanders had bullet holes in their clothing or equipment. A battery of twelve guns was rushed and then, after “F” Battery of the Royal Horse Artillery, with a lucky shot, had hit the magazine of a specially troublesome battery of anti-aircraft guns and blown crews and guns to pieces, Coombes’ company on the right and Smith’s which had been advancing parallel to it on the left charged and entered the low white buildings of Fort Pilastrino, under fire from other Italian positions farther on. It proved to be not a headquarters but a collection of barrack buildings surrounded by a wall. On the right Captain Challen’s66 company moved forward and, in the dusk, a duel began between the infantrymen and Italian guns about 600 yards beyond Pilastrino. Some hours after darkness fell the firing ceased as though both sides were too weary to continue. The men of this battalion had marched twenty miles since 4.30 that morning and had fought their way for five of them against an enemy who outnumbered them greatly and resisted with unusual determination.67

It had been provided that as soon as the 19th Brigade had crossed its starting-line, the 2/2nd Battalion would come under the command of Robertson, whose battalions would then be between the 2/2nd and Allen’s headquarters. Thus, as a preliminary to his afternoon attack, Robertson had ordered Chilton to move across the battlefield to cover the area on his left, where part of the 1/Northumberland Fusiliers was already in position.

–:–

At 10.20 a.m. Brigadier Savige had moved his headquarters forward to Post 75 but before doing so he had instructed Lieut-Colonel King68 of the 2/5th to reconnoitre the area bounded by Posts 65 and 75 so as to be ready to lead his battalion within the perimeter as soon as possible. At 11.55 he ordered King to move into the perimeter but, because of wireless

defects, the message did not reach him until 1.15, when he began to advance. As the 2/5th was moving forward Savige received a delayed order from divisional headquarters that it was to enter the perimeter astride the Bardia road, advance, and come under Robertson’s command. Its task would eventually be to protect Robertson’s right rear. This entailed changing direction half right. Savige wrote afterwards:

They were extended beautifully and moving at a steady rate under continuous shell fire with King leading in his car as he controlled the movement of his battalion. ... Without halting a moment the whole battalion veered half right without bunching or losing a beat in their resolute and steady march. It was the most thrilling spectacle I ever saw in battle, and despite the enemy shell fire, they suffered two casualties only.

The Australian left wing was further strengthened when, soon after midday, Allen ordered the 2/1st to move west to Bir el Mentechsa where it would be in a position to extend or reinforce his right flank if need be. Thus during the afternoon seven of the nine battalions were on or in reserve to the western flank, leaving Savige with two battalions holding the eastern end of the Italian fortress.

–:–

Meanwhile, in accordance with the orders mentioned above, the advance of the 2/4th and 2/11th Battalions had also begun at 2 p.m. On the right the 2/11th Battalion, widely dispersed, moved north-west to the edge of the escarpment overlooking Tobruk harbour from the Wadi Umm es Sciausc on the right to the road on the left. Ahead of the infantry Lieutenant Mills had already taken some of the cavalry carriers to the edge of this escarpment and had fired on the cruiser San Giorgio which lay aground on the far side of the harbour and near the entrance. This fire brought no reply (though later the cruiser fired on the cavalry carriers as they crossed the aerodrome with the 2/4th).

On the left of the 2/11th the 2/4th marched west along the wide shelf between the first and second escarpment with the aerodrome and Fort Solaro as its objective. Robertson impressed upon Dougherty that he was particularly anxious to take Solaro and perhaps capture the commander of the Tobruk garrison there. Behind fire from guns of two regiments – the 2/3rd Australian and the 104th Royal Horse Artillery – and with two anti-tank guns travelling with the leading companies (Captain Conkey’s69 on the right and Captain Rolfe’s70 on the left) the battalion reached the road and crossed it without mishap. A group of Italian tanks approached from the left but were driven off by the anti-tank guns. On the aerodrome the leaders came under point-blank fire from anti-aircraft guns on their right, and halted. Dougherty, who was moving from company to company in a carrier, ordered the artillery to fire on these guns and then told Lieutenant Mackenzie71 to send one platoon out on the right to take them,

which they did. The leading companies, after a twenty-minute halt, moved on towards Solaro. As they neared the buildings Conkey saw six Italian trucks making off in the direction of Tobruk, whereupon he and Private Wright72 mounted captured motor-cycles and sped forward to cut them off. They halted the trucks, but a machine-gun fired at them from a building on the outskirts of Solaro; Wright rode at it, hurled a grenade through the window, and established himself in this building – a kitchen – and fired on the fort. When the remainder of the company arrived they occupied the buildings (which did not deserve the pretentious name “Fort Solaro”) and rounded up some 600 prisoners. It was evident, however, that the Italian headquarters were not there.

Rolfe’s company on the left was being fired on from positions farther to the west and continued to advance towards them; and Dougherty, anxious to find the fortress headquarters before dark, sent McCarty’s73 company forward of Conkey’s to deal with four machine-gun posts sited where the track from Airente to Pilastrino climbs the escarpment. McCarty’s men subdued these posts by firing with anti-tank rifles, which at this stage the Australians were often using against sangars and gun positions because of the moral effect produced when the heavy bullets splintered the rocks. McCarty found that the posts he had taken surrounded the entrances to tunnels which housed what was evidently a large headquarters. The Australians began to drive the occupants from the tunnels as they had done from similar caves and dugouts here and at Bardia, when an Italian officer appeared and told McCarty in English that “the commander” was inside and would surrender only to an officer. He sent Lieutenant Copland74 into the tunnel. Copland was led to an Italian general who asked: “Officer?” “Oui, officer,” said Copland. Both saluted, and the general drew his pistol and handed it to Copland, while tears welled from his eyes. “C’est la guerre,” said Copland. “Oui, c’est la guerre,” said the general. This was General Petassi Manella, commander of the XXII Corps and the Tobruk garrison. Manella, “an old man, dignified and quiet, and very tired”, his captors decided, with his chief of staff, General de Leone, and his artillery commander were led to Dougherty, who took them to brigade headquarters, making the journey in a captured gun tractor, the only available vehicle. Robertson had instructed Dougherty to advance to Fort Airente if it seemed feasible and necessary after he had taken the Italian headquarters. Dougherty now decided not to do so. His men were tired, he had taken the Italian commander, he had no tanks; he could not call up artillery fire because the artillery observer’s wireless set was out of action, and he had 1,600 prisoners to guard.

At brigade headquarters Brigadier Robertson demanded of Manella that he order his men to cease fighting, but the Italian refused to do so, saying that they had their orders to fight to a finish.

–:–

On the perimeter three miles to the south the 2/3rd was still meeting determined opposition. With the intention of breaking the deadlock at Post 45, England decided to reopen the attack on that flank on a three-company front at 1.30 p.m. and take the Italian posts for about a mile and a half beyond the El Adem road. A fresh troop of tanks was obtained and artillery support was organised. In the early afternoon the battalion moved forward, McGregor on the right reaching a line beyond the road. Sergeant Stone’s75 platoon of Abbot’s company was sent wide to the right to deal with machine-gun fire from that direction and, as it breasted the rise north of Post 42, it came within sight of eighteen Italian field guns on the plain beyond. They were firing well over the heads of the advancing infantry, and before either side had recovered from its surprise British shells began to fall closely and accurately round the Italian guns. This combination of events – concentrated artillery fire and a line of infantrymen coolly advancing towards them (though there were now only a dozen or so men in the platoon) – convinced the Italians that they were beaten and they stopped firing. The handful of Australians collected prisoners at each of three batteries and from dugouts in the neighbourhood more and more Italians, probably technical troops, poured in until, when Abbot arrived in a carrier, giving a little added show of strength, there were several hundred either already herded or on their way towards the Australians waving white rags. Abbot, knowing how weak was his hold on the area, ordered that a grenade be exploded in the barrel of each gun lest the enemy should recapture them.

Meanwhile McDonald, on the perimeter, with two newly-arrived tanks, had taken Post 42. Here one of the tanks had to withdraw to refuel and the other’s gun jammed, but the infantrymen kept the attack moving taking Post 43 and, after a ten-minute duel with grenades, 40, the first post beyond the road. At this point “A” Company took over. Fulton had been wounded and Warrant-Officer MacDougal assumed command of the company, handing his platoon to a corporal, Broadhead.76 Post 41 was firing strongly, but, after an exchange of fire, MacDougal gave a loud shout and led the men in a 200-yard charge. The Italians fired and threw grenades until the Australians were standing above the post with MacDougal throwing grenades into the entrances.77 By 3 p.m., Posts 39 and 36 had been taken by Abbot’s company which now took up the

advance (leaving MacDougal at Post 40, McDonald forward of Post 38). From 36 Williams’ platoon (the only platoon in the company which still possessed an effective strength) came under fire from Post 34 and England ordered them to go no farther that night. However, Williams had sent first one of his sections (Corporal Benson’s78) and then another (Corporal Begent’s79) towards Post 37, which they took, but when Italian artillery and the garrison of Post 35 concentrated fire on 37 Benson withdrew his men to 36 where the rest of the platoon were attempting to silence Post 34 with the aid of a mortar.

–:–

For the battalions that had been ordered to move west to reinforce the 19th and 16th Brigades or to protect the flanks, it was a day of much weary and seemingly profitless marching. After an arduous advance from outside the eastern edge of the perimeter, the 2/5th arrived in the 19th Brigade’s area in the middle of the afternoon, whereupon Robertson ordered Lieut-Colonel King to swing northwards and occupy a position along the escarpment with his right on the Wadi Cheteita, and the 2/11th Battalion on his left. King reached this position at dusk and, having arrived there by this roundabout route, was placed under Savige’s command again. Thus at the end of the day Savige’s battalions were across the heads of the deep wadis from Zeitun to a point four miles to the west, the 2/7th on the right, 2/6th in the centre and 2/5th on the left. Next to the left lay the 19th Brigade on a wide arc from the Wadi es Sciausc through Solaro to Pilastrino, whence the line bent back to Post 39.

When making his plans before the attack opened Savige had decided that enemy troops and guns in the Cheteita area might prove troublesome and had ordered Godfrey to allot a company to the task of capturing this fortress area after he had rejoined 17th Brigade. Rowan’s was selected. At 7.45 p.m. (anticipating that he would again be called upon to reinforce Robertson) Savige gave orders that the 2/7th should relieve the 2/6th which would move into reserve except for Rowan’s company; this company would capture the Cheteita fortress area. The 2/7th was to hold the front with only two companies, and keep two available to clear the enemy from the wadis at dawn.

To most of the weary men in the forward companies it seemed that the battle was won. At Bardia the Italian guns were firing vigorously at the end of the first day; at Tobruk they were now almost silent. Over the harbour black plumes of smoke were rising. Ahead of Solaro and Pilastrino there was no sound except of rumbling explosions as the enemy blew up stores of ammunition and fuel. Along the line of Australian outposts the desert was lit up eerily after darkness fell by the fires that blazed in the west and by intermittent flashes from burning dumps, bright enough to make patrolling difficult. Farther south a cluster of fires showed where

Position at dusk, 21st January 1941

some 8,000 Italian prisoners who had been herded along the road to a fenced enclosure three miles north of El Adem were trying to keep themselves warm. Late at night, while the line of battle was still, a squadron of Italian aircraft, in futile response to Tobruk’s appeals for help, saw the fires, and dropped their bomb loads on them. The number of prisoners killed was reported at various figures between 50 and 300; the Italians were huddled together and the effect of the bombs was appalling.80

–:–

That night Mackay gave orders for a final blow the following day. On the right one battalion of the 19th Brigade would clear the escarpment on the south side of the harbour, while the other two battalions would advance from Solaro to the coast and enter the town from the west. Again the 17th Brigade would be drawn upon to assist a neighbouring brigade; on this occasion the 2/6th Battalion was ordered at 2.45 a.m. to be at

Sidi Mahmud at 9 a.m. under the command of the 19th Brigade.81 Allen was instructed to advance westward next morning to Post 19, and also to take over the Pilastrino area. He gave orders to his battalion commanders the 2/2nd on the right, 2/1st in the centre and 2/3rd on the left – to advance on a wide front.

Certain that his company would lead the advance along the perimeter next morning, Abbot had asked Williams in Post 36 to try to take the two next posts during the night. These were being defended with uncommon stubbornness, and Abbot feared that they might delay the advance next morning. Having anticipated this request, Sergeant Long had placed sticks on the ground pointing from 36 towards 37 and 34, since there were no landmarks and he had no compass, and, with six volunteers, he moved out towards Post 37. Although dumps of stores and ammunition which were burning in the Italian lines ahead lit up the desert, it took two hours of cautious movement to find the post. There was no one in it so the raiders threw away the breech-blocks or bent the barrels of the guns and returned to 36. At dawn next morning Long went out against 34 and 35. The forty men in the first post surrendered without a fight and, as the attackers approached 35, the garrison suddenly raced out and the post blew up behind them.

About the same time two Italian officers approached the 2/8th’s lines three miles to the north-west with news that General della Mura of the 61st Division (whose headquarters were not in Pilastrino but in the wadi just beyond it) wished to surrender. Lieutenant Phelan and two of his men went forward to escort the Italian general in to the Australian lines. The general protested in so surly a fashion at being expected to surrender to a junior officer that Major Key was sent for. Della Mura protested that Key also was too junior to take the surrender of a divisional commander, but his complaints had to be disregarded. Behind their commander followed a procession of several thousand officers and men.

Thus, with its senior commanders captured, and more than half of the fortress in the hands of an attacker who was close enough to fire a rifle shot into the town itself, the Italian garrison was not in the mood to offer even a token resistance to the full-scale attack planned for this second day. From dawn onwards came reports from all along the front that the Italians were intent on surrender. In accordance with his plan outlined the previous evening Savige sent companies of the 2/7th, each reinforced by carriers, a mortar and a machine-gun platoon of the Cheshire, into the