Chapter 12: The Capture of Giarabub

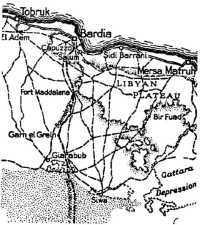

The advance through Cyrenaica had by-passed the Italian force at the now-lonely oasis of Giarabub, 150 miles south of Bardia and near the southern end of the 12-feet wide wire fence which the Italians had built along the frontier. In that stronghold were isolated some 2,000 Italian and Libyan troops under a Colonel Costiana.

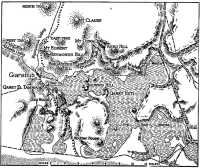

Giarabub is twenty miles beyond the Egyptian frontier at the western end of the westernmost of the chain of oases which lie along the southern edge of the Libyan plateau. Eastwards from the little town extends a marshy depression, lower than sea level, and about thirty miles from west to east. On the north this basin is bounded by the crumbling edge of the plateau which breaks away in a series of escarpments and shelves until it reaches the floor of the depression; to the south and west lie the smooth dunes of the Great Sand Sea. In the depression a few small knolls rise from the marshy bottom; the town itself stands on a shelf of higher ground about 100 feet above sea level. In it is the mosque and tomb of Mahomed Ben Ali el Senussi, a religious reformer whose teaching, in the ‘forties of the last century, won over the tribes which inhabited the Cyrenaican desert, united them and brought them peace and relative prosperity. The mosque is reverenced by the followers of the Senussi and it was impressed upon British troops who served round Giarabub that no damage should be done to it.

Facing Giarabub from sixty miles away on the Egyptian side of the frontier is the larger and more populous oasis of Siwa, the ancient home of an oracle so revered that Alexander the Great visited him, after a laborious pilgrimage. It lies between a jumble of bare and grotesque hills to the north and the glistening dunes of the Sand Sea to the south, and forms a wide expanse of brilliantly green plantations of date palms, lucerne and barley, dotted with translucent, blue pools into which sub-artesian water wells up from below. Though it may not rain for years on end the climate is steamy and tropical. In this fertile area lived some 4,000 Berbers who paid for the few goods that were brought from the outside world by exporting dates.

In July 1940 a British force was sent out across the desert to capture Giarabub but, when it was only a day’s journey from the objective, heat

and shortage of water caused the column to halt, and at length it withdrew. Later General Wavell decided to place a force at Siwa which could deny that oasis to the Italians and at the same time keep Giarabub under observation. Consequently, in September, a company of the 1/King’s Royal Rifle Corps was detached from the 7th Armoured Division and sent to Siwa where it dug and wired defences across the routes from the west; in November it was decided to replace it with a squadron of the 6th Australian Divisional Cavalry, thus enabling the company to rejoin its battalion for the Sidi Barrani battle. The 6th Cavalry was then in training with its division at Amiriya.

Siwa offered water and limited quantities of meat and vegetables, but other military supplies had to be transported across the desert from the coast. Consequently the first task of the Australian force was to establish a store of food and equipment there. Along the track to Siwa there were occasional stretches of hard smooth sand, but mostly the desert was scattered with small boulders or treacherously rutted by the wind. Even in the midst of a military campaign in which tens of thousands of troops were engaged farther north, the tracks to Siwa were generally lonely. Perhaps the men of a convoy would see a herd of camels grazing at one of the rare patches of thorny scrub with a group of Bedouins squatting in a circle nearby; perhaps a few slender gazelle would run across the track; probably crows would cruise overhead searching for desert carrion – when Alexander the Great lost his way to Siwa, the divine oracle (he believed) sent out crows to guide him, and though the hall of the oracle is now empty the crows are still there to inform the desert traveller when he is nearing the oasis. Over this route once a week for five weeks during November and early December a convoy of seven trucks travelled from Mersa Matruh to Siwa; on 3rd December Captain Brown’s1 squadron of the Australian regiment arrived. At Amiriya the unit had been partly equipped with machine-gun carriers and some obsolescent tanks, but before the detached squadron set out for Siwa it was given 30-cwt and 15-cwt trucks which could travel faster than carriers and would not wear out so quickly.

On 11th December, two days after the opening of the battle at Sidi Barrani, Brown received orders to move out across the desert and attack Garn el Grein, one of the small enemy frontier posts between Giarabub and the sea. In two hours the Australians, ninety-six strong, were driving north in the moonlight. They travelled all night in bitter cold, and at 7 o’clock passed the low stone columns that mark the frontier. A quarter of an hour later they came in sight of the post – a building of stone and mud with a triple barbed-wire fence, and a semi-circle of guns in position on the eastern side. Libyan troops could be seen. Brown sent one troop to cut the wire fence and the telegraph line to the north of the post; another to cut its way through the fence a mile south, pass through, and attack from the west; and a third to advance to a position 1,000 yards east

of the post and fire with Vickers guns. The Italians responded with vigour. After having cut down some of the telegraph posts and made a gap in the wire fence, the northern troop of Australians withdrew on the approach of Italian infantry in trucks. About half an hour later the Vickers gunners, who were being briskly shelled, were attacked by three Italian fighter aircraft which dived on them repeatedly until apparently their ammunition was exhausted,2 while the cavalrymen fired back with Brens and rifles. At the same time the Italian guns shelled Lieutenant Cory’s3 troop attacking from the west, and Brown’s headquarters. After an hour Brown decided that his small force could not effectively continue the attack and withdrew.4 In the afternoon Lieutenant Ryrie5 led his troop forward again to investigate, again came under sharp artillery fire, and saw about 100 troops in trucks enter the post. In the evening the little column set off for Siwa.

An intercepted Italian wireless message provided another task for the Australians when, on 16th December, Brown was ordered by Western Desert Force to attack a convoy expected to leave Garn el Grein at 4.30 p.m. that day. During the day the cavalrymen drove 123 miles across the desert and took up a position across the track leading north from Garn el Grein. The convoy appeared at 7.30 and for an hour and a quarter the Australians kept it under fire from Vickers and Brens, the Italians replying with machine-guns and an anti-tank gun. The cavalrymen then withdrew, having destroyed two trucks and caused the Italians to abandon four others, which the Australians added to their own equipment.

The following day Colonel Fergusson with the headquarters of the regiment and Major Abbott’s6 squadron arrived at Siwa. The cavalry regiment of the 6th Division had attracted many young country men who were anxious to enlist in the unit which seemed most closely to resemble the light horse in which the fathers of some of them had served in the previous war. The role they were now being given was one which suited their temperament and training. A group of outstanding leaders, and particularly the commanding officer, had trained the unit well, and inspired it with their own high standards of personal conduct and technical efficiency. Fergusson was a country man, firm and austere, with a varied military experience. He had been invalided from Gallipoli as a young gunner and wounded in France as an artillery subaltern, and between the wars had served in the militia in both artillery and cavalry.

When he and the second squadron arrived the main part of the Italian desert army had been isolated in Bardia. Unwilling to maintain the smaller frontier posts against such raids as the Australians had been subjecting them to, the Italians abandoned Fort Maddalena and Garn el Grein. The first news of these moves came from the Egyptian frontier post opposite Garn, and when Fergusson sent detachments to each post the Italians had gone, leaving useful quantities of equipment and supplies. Thenceforward the Australians’ task was to keep only Giarabub under observation and to ensure, if they could, that no supplies reached it. Wavell expected that thus the Italians’ supplies would be exhausted and they would have to surrender.

The force allotted to Fergusson to carry out this task was extremely slender. The Italian commander had 2,000 men and a substantial number of guns; he occupied a well-prepared position which could be approached only over bare country offering little cover. At the outset the Australian had 200 men (omitting those who were maintaining the base at Siwa), no guns and no aircraft. One of Fergusson’s tasks was to suggest a plan of attack. At intervals he proposed such plans and asked General Wilson (under whose command he now came) for modest reinforcements to enable him to carry them out. On 29th December, for example, satisfied that his knowledge of the Italian strength was accurate, and confident that it was a simple task to capture the fort, Fergusson submitted to General Wilson’s headquarters an estimate of the reinforcements he would need to do so – two infantry companies, the armoured squadron of his regiment, and some artillery, engineers and supply troops.

Such reinforcement was not given to him but, bit by bit, the little force grew. First a troop of Bofors guns arrived, then a detachment of engineers, but for the time being no field artillery and no infantry. Fergusson was ordered for the present not to commit his force to an attack. He sought, by driving in the enemy’s outposts, to make it possible to confine the enemy to a small area so that his own reconnaissance and raiding parties could be reduced in size and the distances they would have to travel would be shortened; thus he would reduce the strain on his supply line. He considered also that frequent excursions to the edge of the bare and crumbling plateau overlooking Giarabub would cause the enemy to consume ammunition which he might not be able to replace.

For example, a few days after the arrival of the main part of the regiment, Brown’s squadron drove a detachment of a dozen or so Libyan troops from an outpost at Melfa eighteen miles east of Giarabub, and next day (Christmas Day) the same squadron moved down the track leading into Giarabub from the north-east along a wadi which the Australians named Pipsqueak Valley – so named because it was commanded by an Italian 44-mm gun which the men nicknamed pipsqueak. They soon came under sharp fire from field artillery and machine-guns. At night an attempt was made to raid the gun positions, but the Italian sentries were vigilant and the raiders withdrew without loss, though later in the

night one of the raiders, Sergeant Walsh,7 missed his way, was wounded and captured. Again, on 26th December, Abbott’s squadron, using anti-tank rifles with effect against the sangars, drove an Italian detachment from a well in the south-eastern lobe of the Giarabub depression. This was the last Italian outpost at the eastern end of the oasis and the cavalry-men were able to concentrate on Giarabub itself. Thenceforward raids and reconnaissance became almost daily affairs, each being pressed a little farther than the last. The Italians ceased to emerge beyond their wire defences, while the sight of a single Australian vehicle on the escarpment drew extravagant Italian fire from field and machine-guns.

It was apparent, however, that the plan to starve the Italians out of Giarabub or to exhaust their ammunition was uncertain of success, because large aircraft were landing on the airfield at regular hours and intervals and, presumably, were ferrying supplies. As soon as Fergusson realised this he had asked for a fighter aircraft and had a landing ground prepared at Garn el Grein but no aircraft was given to him. The intention, however, was still to attack sooner or later, and General Wilson ordered the Australians to establish an advanced base at Melfa and there to store rations, petrol and 25-pounder ammunition.

The Melfa base was established – a laborious process because the local water was considered unfit for drinking and supplies had to be trucked from Siwa. Using Melfa as their depot, but camping well forward of it, the cavalrymen – sometimes both squadrons, sometimes one, sometimes a smaller detachment – continued to scout towards Giarabub almost daily and draw the fire of the Italian artillery; just as regularly one or two aircraft were seen in the distance landing at the Italian airfield and taking off again after a few minutes. A reconnaissance on the last day of December, made with the objects of photographing the fort and advancing close enough to the aerodrome to damage the supply aircraft, led to a brisk engagement in which two men8 were killed by artillery fire, two, including the photographer (Corporal Riedel9), were wounded, and three vehicles disabled.

After this engagement Brown’s squadron returned to Siwa to rest and wash, having been out in the desert almost continuously for three weeks. The winter days had generally been clear and not uncomfortably hot and the men had fed comparatively well, often having a meal brought forward to them in hot-boxes from kitchens established at Melfa. The principal discomforts were the intense cold at night, frequent dust-storms, and the strict rationing of water, every pint of which had still to be carried from Siwa; and every few days a raid would be made towards Giarabub under the eyes of Italian artillery observers posted on knolls on the southern edge of the tableland where it began to descend to Giarabub. There were compensations, however: the starlit silent nights, the clean dry air, and the austere beauty of the desert.

Into this remote world the first week of January brought news of two further reinforcements and promise of a break in the monotony. First the Australians learned that a detachment of the Long Range Desert Group10 had been given the task of patrolling west and north-west of Giarabub, watching the tracks leading to Gialo, the next Italian outpost, 180 miles to the west across soft-sand desert in which only the men of the long range group with their special equipment and training could operate effectively.11 They were to pass information back by wireless to the Australians who task was now defined as to observe Giarabub, and harass the withdrawal of the Italians (if they chose to withdraw). At the end of January, Wilson’s headquarters promised, a force would capture Giarabub. On the 4th January an even more welcome reinforcement arrived: a troop of four 25-pounder guns of a British regular regiment, under Captain

O’Grady.12 The strength of Fergusson’s force was now 200 cavalrymen in the mobile force, 109 at his rear base at Siwa and forward base at Melfa and in his signal section and “light aid detachment”, 115 artillerymen with the field and Bofors guns, and 32 engineers.

A clearer picture of the Italian garrison had now been pieced together by the Intelligence staffs. It included, they believed, 1,200 Italian troops of whom 840 belonged to six machine-gun companies; there was an uncertain number of guns; there were 755 Libyan troops, who comprised an engineer battalion and part of an infantry battalion. On 20th December Colonel Costiana had put the force on half rations and had estimated that his supply of food for Italian troops would be exhausted by the end of December, for Libyans by 15th January. Since then, however, several aircraft had brought in supplies. Thus the Italian garrison outnumbered Fergusson’s force by more than four to one and outnumbered the men he could deploy forward of Melfa by eight to one. Fergusson was able to reflect with some satisfaction that his efforts to convince Costiana that he had a larger force must have succeeded; and he believed that he had convinced the enemy that an attack when it was made would come from the north.

When Brigadier Morshead arrived in Egypt from England in late December with the 18th Australian Brigade, he had been warned by General Blamey that his brigade would be required to capture Giarabub towards the end of January. It was the best trained and best equipped of any Australian brigade outside the 6th Division, of which it had originally formed a part. On 9th January when Morshead arrived at Siwa to reconnoitre, news reached Fergusson from Cairo that an intercepted Italian message indicated that a force from Benghazi was moving to Costiana’s assistance. The cavalry set off into the desert scouting on a twenty-mile front, leaving Giarabub besieged by one troop. Aircraft were summoned and they halted and destroyed the convoy. On the 9th and 10th Morshead went forward with the cavalry to examine the lay of the land. On both days the Italian artillery and machine-gun posts fired briskly, and on the 11th three Italian aircraft took part in the daily skirmish. On each of the following five days detachments drove forward and drew artillery fire, on one occasion escorting O’Grady’s guns which shelled the aerodrome and destroyed an aircraft. Thenceforward the aerodrome was not used, but the aircraft continued to supply Giarabub by dropping their cargoes on the soft sand behind the fort.

With such raids the little force continued its task. It was encouraged to learn from two Libyan deserters that the Italian garrison was convinced that it was surrounded by a large force with much artillery, and interested to be told that the Italians had four “big” guns and twenty smaller artillery weapons. In the second week in February, after the news of the fall of Benghazi, small groups of deserting Libyan soldiers began to appear, either walking north towards the coast or towards Siwa. These batches of

deserters increased in size until, on 15th February, 218 were rounded up and it was concluded that all of Costiana’s native troops had abandoned him. Three weeks later an Italian deserter reported that the daily ration was one biscuit and one small tin of meat, but that there was no talk of surrender. Aircraft, generally two a day, were still dropping supplies, he said. The Australians still had no definite news of the arrival of the force from 18th Brigade (which Morshead had handed over to Brigadier Wootten on 1st February, when he himself took command of the 9th Division).

On 7th March Fergusson, with O’Grady and three Australian war correspondents, went forward in his car towards Giarabub along a track13 through a gully which had been named O’Grady’s Dell. Having seen two Italian aircraft manoeuvring low in the depression Fergusson decided to go forward on foot with his companions to discover whether they were dropping supplies, landing supplies or loading troops. No aircraft had landed since the gunners had destroyed one on the aerodrome, and the Australian commander, who had recently visited his third squadron at Benghazi, was anxious to know whether troops were arriving or being withdrawn. He considered that this was a matter of more than local importance because if troops were being withdrawn it might mean that no counter-attack at El Agheila was contemplated; but if Giarabub was being reinforced such an attack was likely. However, the Italian artillery opened fire and Fergusson was seriously wounded. Thus, five days later, when Wootten arrived with orders to assault and capture Giarabub, not Fergusson but Abbott was in command, and Wootten was unable to learn what had been in the previous commander’s mind.

–:–

Both Wootten’s brigade and the 6th Cavalry were to form part of the force to go to Greece, and General Wavell decided to capture Giarabub in order to free them for their new role. Wootten had received his instructions from General Blamey and General O’Connor (who had then left XIII Corps and was commanding “British Troops in Egypt”) on 10th and 11th March. The amount of transport available limited his force to one battalion plus one company, with enough supplies to last ten days. The operation must be carried through successfully in that time. O’Connor informed Wootten that no tanks would be available (although the enemy’s defences included strong-points protected by wire and there were considerable numbers of field guns, automatic guns and machine-guns), and artillery ammunition and petrol would be limited (another consequence of the shortage of vehicles). When Wootten asked whether there would be air cooperation or support, O’Connor replied: “Please don’t ask me for any planes. I have only two Wellington bombers with which to prevent Rommel bringing his reinforcing units and supplies into Tripoli. If I give you one, I will have only one left.”14 Thus Wootten had to complete the

task and bring the detachment back to Mersa Matruh by 25th March, though the 6th Cavalry might be left a few days longer if necessary. He planned to spend three days moving to Giarabub, four on the reconnaissance and capture of the position and three returning to Matruh. He regretted that it was not possible for his whole brigade to gain battle experience, particularly as he understood that it would soon go to Greece, but the limitation of the force was unavoidable.

After a reconnaissance Wootten decided that the first necessity was to examine the marshy area south of Giarabub to discover whether an attacking force could cross the depression and attack Giarabub from the south in the area west of the frontier wire, between the depression and the Sand Sea. He preferred this to a thrust from the north where the Italians expected attack and where they held posts arranged in depth up to 5,000 to 6,000 yards north of the town.

It appeared (he wrote afterwards) that the ground vital to the enemy’s defence of Giarabub was the (Tamma) heights (approximately 200 feet) situated 400 to 600 yards south of the village. These dominated the whole of the defences. The enemy’s main defences lay to the north, north-east and north-west of this and within approximately 1,500 yards. Any advance by us from these directions by day would be under direct observation from the heights mentioned. ... Any attack from the north, north-east or north-west would have to penetrate the outposts, then deal with the defence in depth and then finally with the southern heights which were themselves a tough object to attack owing to their being wired and fortified and to their steepness and inaccessibility. Such an attack would probably have necessitated a large expenditure of artillery ammunition, a further attack at dawn on the second day to get the high ground and would have resulted in heavy casualties. On the other hand the vital ground was not protected by any depth from the south and its altitude would obviously very largely defilade any attack from the south from fire from the ... north. ... There was also another high feature (Ship Hill) south-east, some hundred yards from the vital ground and outside the enemy’s wire, which if occupied by us would give good observation to support an attack from the south. ... Subject therefore to the ground to the south proving suitable ... and to being able to get the necessary infantry, guns etc. into position ... the commander decided upon this course.

Consequently, on 16th March, he ordered Abbott to examine the country south of the marshy depression which lay between the cavalry-men’s familiar ground north of the oasis and the tracks leading into Giarabub from the south, along which Wootten proposed to attack. That night the detachment from the 18th Brigade reached Bir Fuad, 100 miles north of Siwa.

Brown’s squadron drove across the swamp that night using a track which it had found a little to the east of El Hamra (Brown’s Hill) and thence, at 5 a.m., moved south-west on an Italian post at a building which it named “Wootten House”. It was unoccupied, but at 8.30 a.m. two Italian trucks appeared in the north, evidently containing a party which normally occupied Wootten House by day. The cavalrymen opened fire, killing two Italians and capturing fifteen, including two officers, one of whom described the Italian position and indicated the site of each gun.

Lieutenant Taylor,15 the Intelligence officer of the cavalry regiment, passed this information on to Wootten’s headquarters. From Wootten’s the cavalry advanced northwards towards “Daly House” (after Wootten’s brigade major,16 who was with the squadron), a post about 5,000 yards south-east of the town. Here they came under fire from some forty Italians with an anti-tank gun and machine-guns. Lieutenant Wade’s17 troop advanced, drove off the Italians and occupied the area, but were themselves forced out by the fire of two guns which the Italians brought forward on trucks. As the morning continued the Italian artillery fire became hotter and, at 1.50, the cavalrymen withdrew, having accomplished their task: the crossing of the swamp and the examination of the track leading into Giarabub from the south.

The force which had now arrived to carry out the attack included the 2/9th (Queensland) Battalion, a company of the 2/10th, the mortar platoon of the same battalion and some other infantry detachments. In addition to O’Grady’s troop of 25-pounders there was a battery of the 4th Royal Horse Artillery, making sixteen guns in all. Wootten’s initial instructions to Lieut-Colonel Martin, of the 2/9th, were that he was, with two companies, to make a reconnaissance in strength and secure, first, a line running north-east to south-west astride a track about 1,000 yards forward of Daly House and, secondly, by dawn on 20th March, a parallel line from the centre of the western lobe of the Giarabub depression to Tamma, which would place him about 1,000 yards from the edge of Giarabub town. Martin and Daly reconnoitred the ground on the evening of the 18th.

However, on the 19th, Lieut-Colonel “Jock” Campbell, the commanding officer of the 4th Royal Horse Artillery, told Wootten that he had grave doubts whether the guns could get through the swamp area to the southern track by the present route, which was proving difficult even for trucks. Wootten himself was also perturbed because of his lack of knowledge of the approaches along which he proposed to attack. To test them, there-fore, he decided to attack and capture the first line (1,000 yards ahead of Daly House) in daylight and exploit thence to the Tamma knolls. At the same time the cavalrymen were to make a demonstration north of Giarabub all the afternoon and until late at night to distract the attention of the defenders.

In the afternoon of the 19th the leading companies of the 2/9th set out along the same treacherous route in 30-cwt and 3-ton trucks. The disturbing doubt whether it would be possible to pull the guns through the swamp was ended when the energetic battery commander, Major Geoffrey Goschen,18 and his men hauled two guns across the marsh in the wake of

the infantry and put them in position about 1,000 yards south of Daly House. The remaining guns were dragged across with the aid of Italian tractors captured earlier by the cavalry. Vehicles carrying the infantry bogged and soon the column was strung out along several miles. Both in the swamp and from Wootten House onwards the infantry had often to jump from the trucks and push them, but they succeeded in arriving at Daly House by 3 p.m. The Italian gunners began to shell them but not accurately, and there was machine-gun fire, but it fell short. ‘The first objective was found to be unoccupied by the enemy. Time was pressing. At Daly’s suggestion Martin decided to send the leading company, Captain Berry’s,19 still in its trucks, straight on past this first objective to Tamma, and there Berry arrived about 5 p.m. The men were still west of a belt of wire – a continuation of the frontier fence – which ran north and south along the east side of the track separating Tamma from Ship Hill. Immediately ahead they could see the cluster of knolls into which were dug the main southern defences of the Italian fortress, and beyond them the white buildings and palm groves of the little town. Berry sent one of his platoons – Lieutenant Lovett’s20 – towards Ship Hill whence it could give covering fire while the remainder of the company moved forward on the left among sandhills which offered some protection from the Italian fire.

As the infantrymen advanced the Italians began firing at them with 20-mm guns, whose tracer shells “bounded all over the desert”. Just at dark the leading platoon reached the barbed wire at the south-eastern corner of the Italian defence area. Berry, whose company was now 600 yards ahead of the nearest support, decided to investigate the Italian positions still further, and went on through the wire alone “snooping round” until an Italian sentry challenged him and fired a shot. He then turned back, found Lieutenant Forster’s21 platoon, and sent one section through the wire to fire across the knoll the Italians were occupying, while, with the other two sections, Berry and Forster advanced on to the knoll itself. While Berry was quietly giving these orders the Italians threw some grenades from their sangars, not more than twenty yards away. When the men advanced, however, not a shot was fired – the Italians, probably six or seven of them, had abandoned the post (Post 42) leaving a machine-gun behind them.

All was going well. Berry left Forster’s platoon in the post with orders to exploit and explore while he returned to Lovett’s platoon which also had moved up to the knoll, and was soon joined by a second company and a machine-gun section. Berry then returned to Martin’s headquarters and told him where his men were. It was now 10 p.m.

Meanwhile Forster, “exploring and exploiting”, found Post 36, manned by one Italian and armed with a 44-mm gun. They made the Italian a

prisoner, overturned the gun and sent the Italian back to Martin’s head-quarters for interrogation, carrying a wounded Australian. Little fire was coming from the Italians because, it was decided, they were bewildered by the Australians’ impudent tactics. However, at 2 a.m., after the moon had risen, and while the company commanders were finding a position in the sand hills south of the Italian posts to withdraw to before light, a strong Italian patrol attacked the men on the knoll. In the skirmish three men were wounded and Forster withdrew his platoon through the wire in obedience to Berry’s orders not to become involved in “anything serious”. When it was over two men were missing.

At dawn on the 20th a fierce wind blew up a layer of moving sand over the depression. All the automatic weapons – the Brens and Thompson guns – in the forward companies were clogged with sand. Berry, on the morning after his first clash with an enemy but as confident as if he were an old campaigner, telephoned Martin that he would have to move farther back and would appreciate support from the artillery (the nearest company was 800 yards away). The artillery fire came down promptly and sounded encouraging, and mortars arrived and began bombing the Italians, whose artillery fire was falling in the area held by the company next behind. Berry went back to Martin’s headquarters twice during the day through the blowing sand “along a good covered way parallel to the Italian barbed wire”. The men in the sand dunes discovered that in a few hours their signal wire – the only sure guide from battalion headquarters to company or from company to platoon – in places was buried six feet deep in blown sand.

Thus the exploratory attack, whose objective was a line 1,000 yards beyond Daly House, succeeded beyond expectations. Martin’s decision to continue the advance and the determination with which Berry and his men carried out the orders had taken the Australians into the fringes of the main Italian defences whence, at their own time, they had withdrawn to ground in which they had some protection against the enemy’s fire and could renew the attack when ordered. During the night Lieutenant Burt’s22 squadron of the cavalry had demonstrated from the north to such good effect that, although they withdrew at 11 p.m., the Italians continued firing all night; at dawn Brown’s squadron occupied a line through Point 76 on the northern side of the depression, whence it could cover the passage of the swamp by the remainder of the force.

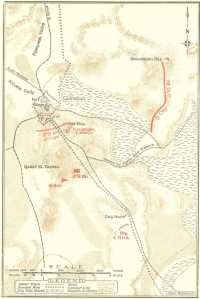

Wootten’s orders to Martin for the capture of Giarabub were simple. The 2/9th, increased by machine-gunners of the 2/12th and mortarmen of the 2/10th, would attack at dawn on the 21st from a start-line 400 yards south of the wire round the fortified knolls and would capture these. Thence they would advance to the second objective – the town itself. The engineers would blow gaps in the Italian wire to let the infantry through. The artillery would fire on the fortified knolls for ten minutes after zero and then lift to the second objective. The cavalry’s role was to advance

from the north-east to the airfield north of the town. To enable the cavalry to be concentrated in this area Wootten’s reserve company (of the 2/10th) was to take over the whole of the line on the heights north of the depression. As the attack developed this company would advance along the track Melfa-Giarabub and the high ground to the north to protect engineers who were to develop a track across the narrow neck of the marsh and thus shorten by seven miles the roundabout and boggy route by which troops and supplies were reaching the front line. The capture of Tamma enabled the brigadier and the battalion commander to move their headquarters forward to within a mile and a half of the start-line under the southern and protected side of that feature.

During the day Berry’s platoon lay among the sandhills, while, in a mild sandstorm which helped to conceal their movements, trucks carried across the marsh and along the track through Daly House the additional forces that were to take part in the attack next day. Some German aircraft appeared at intervals but did not look for targets in the south, evidently still believing that the thrust was coming from the north and east and not knowing that already the attackers had reached Tamma. During the after-noon and evening Captain Reidy’s23 company of the 2/9th arrived (bringing a hot meal to help Berry’s weary men, dressed only in shirts and shorts, through a second cold night on the sandhills) and took up a position on the right ready for the attack. The Australian positions were so close to the Italian redoubt that the Italians in some places were only 100 yards or so distant. For example, during the day Lieutenant Noyes24 of Reidy’s company went cautiously forward to visit a man who was alone among the sandhills as “marker” for a platoon which had not yet arrived. Noyes found that the man had inquisitively moved forward and, as Noyes arrived, he pointed to a figure not far away and said: “Who’s that chap over there?” “He’s a Dago,” said Noyes. “Good ! I thought he was one of our blokes. I was just going over to have a yarn with him.”

The Italian position which was the objective of the first phase of the attack was, in effect, a fortress about 300 yards wide by 600 yards surrounded by barbed wire. It was sited on a rocky hill about 100 feet high and very steep, into which a system of trenches and numbered machine-gun posts had been dug. Martin’s plan was that Reidy’s company on the right would attack the eastern half of the fortified area, and Berry’s in the centre would attack the western half frontally, while a third company attacked the western flank of the position. In the second phase this company (Captain Loxton’s25) and a fourth one would take the lead and advance into the town itself. Major Wearne26 was placed in command of the two forward companies for the first phase. To strengthen the supporting

The 2/9th Battalion Attack: position at dawn 21st March

fire Martin placed on and round Ship Hill six 3-inch mortars and six Vickers guns27 – Wootten having wisely brought to Giarabub all the 3-inch mortars and belt-fed machine-guns the brigade possessed. He ordered the company commanders to advance in three bounds, the first to be finished twenty-five minutes after zero, which was fixed at 5.15 a.m. Thus the attack would open in faint moonlight and daylight would come at the end of the first phase and after the most dangerous part of the advance.

During the night an ice-cold wind began to blow and by one o’clock in the morning it had raised a denser sandstorm than even the cavalrymen had experienced in their three months in the desert. The wind dropped somewhat in the early hours of the morning, but as dawn approached the dust was still so thick that in the front line it was impossible to see farther than fifty yards. Reidy, anxious to be as close as possible to the Italian positions when the barrage ceased, moved his men forward in the sand-storm until they were within fifty yards of the Italian wire, and they lay there for ten minutes or more waiting for guns. Then the guns opened fire.

Our artillery landed right among us (said Noyes afterwards). I yelled to them to scratch into the sand which they did. We had no word of 8 platoon or the OC who was with it. As soon as the barrage ceased we got up and into it.

In blowing sand the two companies advanced. Very little fire was coming from the Italian positions. Noyes’ men found that the Italians were in caves dug into the side of the hill, protected by parapets of stones and sandbags, and generally with blankets curtaining the entrance so that the attackers had to pull them aside before throwing in grenades. Before the first of the two knolls had been passed there were no grenades left – each man had set out with only two – and all weapons were clogged with sand except the anti-tank rifle. The artillery fire was now falling on the farther knoll, so Noyes, having told his men to wait until this fire lifted, tried to find the platoon which should have been on his left, but failed. Finally, without waiting for the barrage to lift, Noyes’ platoon advanced. At the foot of the knoll they met the right platoon of Berry’s company. This company had had three men wounded in the attack, but had found the Italians apparently too stunned by the bombardment to fight effectively.

The second knoll caused more trouble than the first because the Italians were deeply dug in on the northern side and the attackers came under accurate fire from the fort and the plantation beyond. The Italians in these caves, though they were being subjected to a galling fire from the mortars and machine-guns on Ship Hill, were more determined than those farther forward, and several Australians were killed here by Italian grenades.28 However, soon after 9, all real resistance had ceased, though the grenading of Italian dugouts and the shooting of every Italian who appeared continued. Berry said that they should encourage the Italians to surrender

and, as soon as the Italians perceived that prisoners were being taken, dozens appeared from within the honeycombed knoll. About 200 prisoners were taken here; about the same number had been killed. Not until the advancing troops reached this second fortified knoll did they establish touch with the remainder of Reidy’s company and learn that, when the barrage fell among the men on the start-line, Reidy himself and eleven others had been killed and about twenty wounded.29

Berry, who was carrying on in spite of a wound received in the advance to the first objective, led two of his platoons on to the fort and reached it about the same time as Loxton’s company, which had made a wide flanking movement on the left, meeting considerable fire and suffering some fifteen casualties. Martin had delayed the advance of the company which was to be on the right in the second phase because for some time Loxton’s had been out of touch and he feared lest they might collide. At 10 a.m., however, it began to advance towards the plantations on the north-eastern edge of the town, slowly because a minefield lay across its path and the mines had to be disarmed. There was no opposition now. The Italian flag was pulled down and the black and blue banner of the 2/9th was hauled up in its place. By 2 p.m. some 600 prisoners had been collected and sent marching south over the sand. Among the captured Italians was Colonel Costiana, who had been slightly wounded by a grenade at his headquarters in the redoubt.30

Meanwhile the minor enterprises had gone according to plan. By 8 o’clock the shorter route through the marsh had been opened. The cavalry-men had moved forward from the north-east and, gaining some concealment from the blowing sand and using their machine-guns to strengthen the artillery barrage, had taken a series of machine-gun positions, and at 10.30 (shortly after resistance had ceased in the redoubt in the south) reached and occupied the hangars, where Wootten ordered them to remain because he feared that in the sandstorm they might clash with the infantry-men advancing in the opposite direction. At 9.30 a German aircraft had appeared and had bombed Abbott’s headquarters and his vehicles, and the rear echelon of the 18th Brigade, but without causing any casualties.31

The attackers lost 17 killed and 77 were wounded, all but 10 of the casualties being in the 2/9th Battalion.32 It was estimated that 250 Italians were killed, but the exact number will probably not be accurately fixed and was probably fewer than this. After the fighting ceased the wind was

still blowing so strongly that the bodies of the dead were quickly covered by sand. Going forward through the redoubt Martin counted sixteen Italian corpses on one slope, but when he returned two hours later, all but two had been completely covered. The prisoners were estimated at 50 officers and 1,250 men of whom about 100 had been wounded. There were 26 guns of 47 to 77-mm calibre and 10 smaller guns. The Rome radio reported that night that Giarabub had fallen after “the last round had been fired.” Actually 1,000,000 rounds of small-arms ammunition and 10,000 shells were still unexpended.

The day after the battle, while the cavalrymen and a platoon of Senussi which had been organised at Siwa remained to salvage captured equipment, the troops of the 18th Brigade set off on their return journey.33 Wootten and his staff arrived at Ikingi on 24th March, and the troops arrived by road and rail on the following four days. On the 30th the cavalry regiment also reached Amiriya, and joined its third squadron which had recently returned from Benghazi.

–:–

Because of the failure to pursue and complete the defeat of the opposing army the campaign in Cyrenaica produced a relatively small strategical gain – the destruction of one Italian army and the temporary occupation of some territory. On the other hand it attracted the forces of Italy’s more efficient ally into Africa.

On the credit side was the fact that the British force, though small, had gained valuable experience of mobile warfare in a desert which for the next two years was to remain a major battlefield. Leaders, men, equipment, tactics and staff work had been tested in a way which would not have been possible if Western Desert Force had spent the winter watching the three Italian army corps at Sidi Barrani. The campaign had demonstrated that battles are not won entirely with machines but that a small, well-trained and aggressive force could defeat a far larger and more strongly-equipped one; and that infantry and artillery could break through defensive lines on which steel and concrete had been lavishly spent.

For the Australian soldiers the experience was of special value because it would seep so quickly through the whole of the growing Australian force assembling in the Middle East. Leaders and staffs had gained in confidence and wisdom. Fears expressed by Australian staff officers in Palestine and Alexandria that the division would be spoiled by easy victories not only underestimated the strenuousness of the campaign and the bitterness of some of the fighting but underrated the leaders. As soon as

the operations were over, commanding officers were ordered to resume training “to overcome (as one divisional order said) weaknesses noted during the campaign and recapitulate operations in which the units have not been fully tested, e.g. air action.” Mackay was fully aware that in later campaigns attack from the air was likely to be severe. “The German,” said a brigade instruction, “will exact heavy payment if some of the gross errors (skylines, etc.) witnessed at Bardia and Tobruk are repeated.” Mackay, in an instruction to officers denounced the “ambiguity, inaccuracy, vagueness, irrelevancy and sometimes exaggeration” which he had observed in their messages and reports.34 ‘There were no signs of self-satisfaction. Then, and later, the end of a campaign was a time for learning its lessons, “smartening up” and retraining. Indeed, the men themselves were so keen and so anxious to acquire knowledge and test it by experiment that it was not likely that, in any event, the success in Libya would have deadened their ambition to master the trade they had newly adopted. Success gave them increased confidence in their officers, in themselves and their training, and from among the younger men were emerging out-standing leaders whom we will meet again in later battles.