Chapter 1: Britain and Greece

This volume is chiefly concerned with three short campaigns fought in the Middle East in the spring and early summer of 1941. In each of them a relatively large Australian contingent took part and in two of them an Australian commanded the main force in the field during a crucial phase. Never before had Australian political leaders been so closely involved in decisions affecting the conduct of military operations, nor had Australian military leaders borne such heavy independent responsibility in the field. At every level, problems of enduring interest to smaller partners in an alliance were encountered. To the Australian infantry these campaigns brought their first experience of large-scale mountain warfare and of large-scale operations in which the enemy dominated the air.

In March 1941 when this phase opened, the British armies in Africa and the Greek army in Albania had inflicted a series of defeats on the Italian army, but, except for some recent skirmishes with a few German units newly arrived in Africa, and some commando raids in western Europe, there had been no contact between the British and German armies since June 1940. It was evident, however, that the German army would soon intervene both in North Africa and the Balkans, either in pursuance of Hitler’s own long-range plans or in support of Italy.

When Italy had invaded Greece on 28th October 1940 she intended a lightning campaign which would soon leave her master of the southern Balkans and the Aegean. Instead, to the annoyance of her senior ally, she started a chain of events which was to make Greece briefly a battleground for the two main antagonists – Britain and Germany. An immediate Greek reaction to the Italian invasion had been to invoke a long-standing guarantee that Britain would support Greece if she were attacked without provocation. Promptly a British air force contingent was flown to Athens, and soon four squadrons and part of another were operating from Greek airfields against the Italians in Albania. In November a weak British infantry brigade group was landed in Crete, and about 4,200 anti-aircraft gunners, air force ground staff and depot troops were sent to Athens.

At that time the British Commonwealth stood alone against Germany and her European satellites. Italy’s attack on Greece made Greece an ally of Britain against Italy but not against Germany. In the last quarter of 1940 Britain had two main military pre-occupations – the defence of the British Isles against invasion by an otherwise unemployed German army, and the defence of the Middle East against the Italians. The Greeks then neither sought nor needed military reinforcements on a large scale. They promptly defeated the Italian thrust into Greek territory from Albania and themselves took the offensive, with immediate success. When January opened fourteen Greek divisions faced nineteen Italian

divisions on a front about 100 miles in length and from 20 to 30 miles within the Albanian border.

The Greeks had thus demonstrated that they could defend their territory against the Italians; but Germany was master of Hungary and Rumania, and should she march southward into Greece through Bulgaria Greece would undoubtedly be overpowered. In January the Germans were known to have twelve divisions and a powerful air force in Rumania. Greece on the other hand had only four divisions left on the Bulgarian frontier, and one of these was due soon to move to Albania. This was the situation when on 6th January the British Foreign Minister, Mr Eden, informed the Prime Minister, Mr Churchill, that

a mass of information has come to us over the last few days from divers sources, all of which tends to show that Germany is pressing forward her preparations in the Balkans with a view to an ultimate descent upon Greece. The date usually mentioned for such a descent is the beginning of March, but I feel confident that the Germans must be making every effort to antedate their move. Whether or not military operations are possible through Bulgaria against Salonika at this time of the year I am not qualified to say, but we may feel certain that Germany will seek to intervene by force to prevent complete Italian defeat in Albania.1

A month earlier the British forces in North Africa had opened an offensive, driven the Italians out of Egypt, and on 3rd and 4th January had overcome the Italians’ fortress of Bardia in eastern Cyrenaica. On the 8th the Chiefs of Staff in London decided that no effective resistance could be offered to a German invasion of Greece but, nevertheless, on the 10th, after considering Eden’s submission, Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff decided that once their army in Cyrenaica had taken the fortress of Tobruk, which was then invested, all other operations in the Middle East must have second place to sending the greatest possible help to the Greeks. Consequently General Wavell, Commander-in-Chief of the British army in the Middle East, and Air Chief Marshal Longmore, Commander-in-Chief of the British air forces there, went to Athens to

offer to the Greek dictator, General Metaxas, a small immediate reinforcement – a squadron of infantry tanks, a regiment of cruiser tanks and some regiments of artillery,2 In informal discussion Wavell told the Greek leaders that, in addition to these units, two or three divisions could be dispatched within two months.3

Metaxas declined these offers on the grounds that the contingent of artillery and armour would not effectively reinforce the Greek Army and might provide the Germans with a pretext for attacking Greece; he considered that even two or three divisions would be quite inadequate to the task presented by a German invasion. General Papagos, the Greek Commander-in-Chief, said that to establish “a good defensive position and a reasonably strong front” on the Bulgarian frontier reinforcement by nine British divisions with suitable air support would be needed. He wrote later that he advised Metaxas in private that the limited aid which Britain was proposing to give to Greece

would not only fail to produce substantial military and political results in the Balkans, but would also, from the more general allied point of view, be contrary to the sound principles of strategy. ... In fact, the two or three divisions which it was proposed to withdraw from the Army in Egypt to send to Greece would come in more useful in Africa.4

After the Athens conference Wavell told the Chiefs of Staff in London that he himself regarded the proposal to send a few units as “a dangerous half-measure”.

In a formal note sent to the British Government on 18th January Metaxas said that he would agree to the disembarkation of a British force in Greece as soon as German troops entered Bulgaria. He informed the Yugoslav Government of his replies to Britain, and later told Papagos that he knew that the Yugoslav Government had passed the information on to Germany.

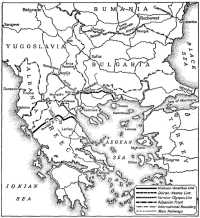

Because of their uncertainty about the policy which Yugoslavia would follow if the German Army invaded Greece, Metaxas and Papagos faced a most difficult politico-military problem. If Yugoslavia joined Britain and Greece against German attack, the port of Salonika should be held because this was the only effective means of supplying the Yugoslavs; in that case the Anglo-Greek force should hold the well-designed frontier fortifications, named the Metaxas Line, with an eastern flank preferably on the Nestos River. If Yugoslavia remained truly neutral, a withdrawal from this line protecting Salonika to a shorter and stronger line on the Vermion Range, through Edessa to Mount Olympus would be desirable. If Yugoslavia allowed German troops to pass through her territory, however, they could outflank the Vermion passes by way of the Monastir Gap, and Papagos considered that, in that event, the best defensive line would be one through the Olympus passes, along the Aliakmon River

and the Venetikos River and thence to a shortened front against the Italians in Albania.5 These three lines – the Doiran-Nestos position, embracing the Metaxas Line; the Vermion-Olympus line; and a line along the Aliakmon – were to be frequently under discussion in the following weeks.

Three days after receiving Metaxas’ note declining help the British Chiefs of Staff instructed Wavell and his fellow Commanders-in-Chief to continue the advance in Cyrenaica as far as Benghazi. At the same time they ordered him to seize Rhodes and other places in the Italian Dodecanese so as to forestall the possible arrival of a German air force in those islands, which lay close to the line of communications with Greece

and Turkey. They also instructed him to form a reserve of four divisions for possible service in the Balkans.

Meanwhile, late in January, the Italians, who now had twenty-one divisions in Albania, opened a counter-offensive. It failed utterly after a few days. Thereupon Papagos decided that the Greek armies – which had been strengthened by the capture by their own troops of much Italian equipment and also by considerable instalments of British and captured Italians arms and vehicles from Egypt – should attack the shaken Italian force in the hope of taking Valona. Loss of that port would greatly slow down the maintenance of the Italian force in Albania, and a further Greek offensive might then drive them out of the country. At the least the capture of Valona would shorten the Albanian front before the Germans attacked in the spring; and the Greek leaders were now convinced that the Germans would do so as soon as the winter ended and the drying of the Balkan roads made large-scale military movement possible. At the request of the Greek King and Papagos, Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac, who commanded the British air force in Greece, agreed to allow his squadrons to be used in close support of the troops in this offensive, to encourage them to endure the bombing by Italian aircraft and the rigours of a winter campaign in bitterly cold and inhospitable mountains. The offensive was opened with great dash early in February but Italian reinforcements had been hurried to Albania where twenty-six Italian divisions had now been identified, and the efforts of these, combined with exceptionally heavy snow and rain, halted the attack.6

Greece had thrown nearly all her resources into this offensive. Her army now contained twenty-one divisions and had the support of a small but efficient British air force. All but six of the Greek divisions were now engaged in the Albanian campaign, and those six, held in reserve or on the Bulgarian frontier, were far below strength.7

Meanwhile, on 29th January, General Metaxas had died. The King appointed M. Alexander Koryzis to succeed him as Prime Minister. On 8th February (two days after Australian troops had taken the surrender of Benghazi) Koryzis sent a note to the British Government reaffirming Greece’s determination to resist a German attack, repeating that a British force should not be sent to Macedonia unless the German Army entered Bulgaria, but suggesting that the size and composition of the proposed force should be determined

so that the British Government may be in a position to judge whether, despite the sacrifices which Greece is prepared to make in resisting the aggressor with the

weak forces which she has available on the Macedonian front, the British force to be dispatched will be adequate together with the Greek forces to frustrate the German aggression and at the same time to encourage Yugoslavia and Turkey to take part in the struggle.8

Three days later Churchill and his Chiefs of Staff, adhering to their policy of concentrating on help to Greece and Turkey, decided that the British advance in Cyrenaica must be halted. On the 12th Mr Churchill conveyed this decision to General Wavell, who was informed that Mr Eden and the Chief of the General Staff, General Dill, were due in Cairo on the 14th or 15th February.

Having surveyed the whole position in Cairo and got all preparatory measures on the move (wrote Churchill to Wavell) you will no doubt go to Athens with them, and, thereafter, if convenient, to Angora. It is hoped that at least four divisions, including one armoured division, and whatever additional air forces the Greek airfields are ready for, together with all available munitions, may be offered in the best possible way and in the shortest time. ... In the event of its proving impossible to reach any good agreement with the Greeks and work out a practical military plan, then we must try to save as much from the wreck as possible. We must at all costs keep Crete and take any Greek islands which are of use as air bases. We could also reconsider the advance on Tripoli.9

Churchill told Wavell that he should not, however, delay the capture of Rhodes “which we regard as most urgent”. The occupation of Rhodes was to be the first step in the achievement of the British Government’s intentions, which were to help Greece, draw both Turkey and Yugoslavia into the Allied camp, and thus build up a battle front in the Balkans.

We know now that on 12th November 1940 Hitler had ordered his staff to plan the occupation of northern Greece, and had allotted an army of about ten divisions to this task. Later in November the German objective was enlarged to include the whole of Greece, and on 13th December Hitler decided that the invasion would probably take place in March. At this stage, partly as a result of the impression made on Hitler and his staff by the British successes in North Africa and the Greek successes in Albania, a larger German army was allotted to the coming invasion of Greece. The purpose to be attained was to secure Germany’s southern flank in preparation for the invasion of Russia, timed to begin some time after 15th May, and in particular to preclude attack on the Rumanian oilfields by British bombers based in Greece.

The size of the army which Hitler could afford to employ against Greece was limited only by the capacity of the Balkan roads. No German formations had been engaged since June 1940, and since then the size of the German Army had been increased and its equipment and training improved. On the other hand Wavell had only two armoured divisions (one now lacking equipment) and eight infantry divisions (not including two small and lightly-armed African formations). Three of the infantry

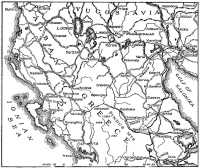

divisions were engaged against the Italians in Abyssinia, and a fourth – the 6th British – had been allotted to the attack on Rhodes. The 7th Armoured Division would not be available until its tanks, worn out after eight months of fighting in North Africa, had been overhauled or replaced. Consequently the divisions available for the garrisoning of Cyrenaica and the proposed expedition to Greece were the 2nd Armoured, 6th, 7th and 9th Australian and the New Zealand. Thus if one armoured and three infantry divisions were to be offered to Greece, as Churchill wished, the greater part of that force would of necessity consist of Australians and New Zealanders.

The cruiser tanks of the 2nd Armoured Division, which had arrived in Egypt in January, were worn, and no tracks were available to repair them except some which had been made in Australia and which “on trial proved to be practically useless”.10 Wavell decided to separate this division into two parts, send the headquarters and one brigade to eastern Cyrenaica and retain the second brigade for possible use in Greece. He planned to leave the seasoned 6th Australian Division in Cyrenaica and prepare to send to Greece first the New Zealand Division and then the 7th Australian Division and a Polish Brigade (formed from Poles who had escaped to the Middle East after the German invasion of their country). Finally he proposed to replace the 6th Australian Division in Cyrenaica with the relatively raw and ill-equipped 9th Australian and send the 6th to Greece.

This would mean that at least one fully equipped and seasoned division would be available for the defence of Cyrenaica for the first month or so, since it was calculated that the dispatch of the total force to Greece would take 10 weeks to complete. General Blamey ... insisted, however, and as it proved rightly so, that the 7th Division was not sufficiently trained or equipped and that the 6th Division must be the first to proceed. This involved relieving the 6th Australian Division at once by the 9th Australian Division, which was only partly trained and equipped.11

The 18th and 25th Australian Brigades having now arrived in the Middle East from England, whither the 18th Brigade had been diverted in June 1940 and where the 25th had been formed, the 7th and 9th Divisions had been reorganised. The 18th Brigade, formed in 1939, and the 25th, formed in June 1940, and both relatively well-equipped, were transferred from the 9th to the 7th Division, which seemed likely to be in action before the 9th. The 21st Brigade remained in the 7th Division. The 9th Division was allotted the 20th, formed in April 1940, and the 24th and 26th, formed in July. The 8th Division, divided between Malaya and Australia, included the 22nd, 23rd and 27th Brigades.

The Australian Prime Minister, Mr Menzies, had arrived in Egypt on 5th February on his way to London for conferences with the British Cabinet. He was in North Africa until the 13th and had discussions with

General Wavell about the general proposal to offer a force to Greece. After these discussions General Wavell had sent a telegram to Mr Churchill on the 12th February in which he said: “We have naturally been considering problem of assistance to Greece and Turkey for some time. My [telegram] of 11 February to Chief of the Imperial General Staff gave estimate of available resources but hope may be able to improve on this especially if Australian Government will give me certain latitude as regards use of their troops. I have already spoken to Menzies about this and he was very ready to agree to what I suggest. I will approach him again before he leaves.” Menzies had also met General Blamey, the commander of the AIF in the Middle East, but Churchill’s directive to Wavell was received only the day before Menzies’ departure, and Blamey, who was with his I Australian Corps headquarters in western Cyrenaica, had not yet learnt of the proposal to send his corps to Greece; it was not discussed between him and Menzies.

Wavell was not entirely happy about the plan. On 17th February he issued some notes in which his perplexity is evident:

Owing to the political hesitations of our Greek and Turkish allies, to say nothing of the Yugoslavs, we have been placed in a most difficult situation. Our military objective in the Balkans is purely defensive, for the present at any rate. Personally I can never see much prospect of the Balkans becoming an offensive military front from our point of view. Therefore we want to employ the minimum force to secure our object. ... On the other hand the Balkans may well become an offensive theatre from the air point of view, since there is a vital objective to the enemy in the Rumanian oilfields ... If we can put a sufficient force into Macedonia to ensure the safety of the port of Salonika and to hold its principal passes from Bulgaria, we shall have fulfilled our object. ... Unfortunately our forces available are very limited and it is doubtful whether they can arrive in time.

He added that another course would be to help the Greeks to hold a line on the Aliakmon River. There was also a fear at Wavell’s headquarters (as Menzies was informed when he was in Cairo) that the Greeks would not resist when the time came, a fear which the assurances of Koryzis had not wholly dispelled.12 Meanwhile, the strength of the air forces in the Middle East was actually waning. Longmore pointed out afterwards that aircraft were arriving from Britain and America in insufficient numbers to replace losses; in the three months to 31st March, for example, losses were 184, arrivals 166. The army in the Middle East would not be substantially increased in the near future. Although convoys were arriving from England at regular intervals they were loaded principally with depot units, equipment and reinforcements. Except for the ill-equipped 2nd Armoured Division, no effective fighting formation had reached the Middle East from England since the fall of France, though plans were then afoot for sending the 50th British Division round the Cape.

Eden and Dill arrived in Cairo on the 19th, having been delayed by bad weather. At a meeting there on the 20th Wavell described the force he could make available and (in spite of his doubt that an adequate force could be got there in time) advised proposing to the Greeks that an attempt be made to defend Salonika. Both Admiral Cunningham, commanding the Mediterranean Fleet, and Air Chief Marshal Longmore were doubtful about this feature of the plan. Later Cunningham wrote about the expedition as a whole:

I gave it as my opinion that though politically we were correct, I had grave uncertainty of its military expedience. Dill himself had doubts, and said to me after the meeting: “Well, we’ve taken the decision. I’m not at all sure it’s the right one.”13

After this meeting Eden cabled to Churchill that his present intention was to tell the Greeks of the help they were prepared to give them and urge them to accept it as fast as it could be shipped. “There is a fair chance that we can hold a line in Greece,” he said. What line should it be? Eden reported that “present limited air forces available make it doubtful whether we can hold a line covering Salonika, which General Wavell is prepared to contemplate. C. in C. Mediterranean considers that he could supply the necessary protection at sea to enable Salonika to be used as base, but emphasises that to do this he will need air protection, which we fear would prove an insuperable difficulty.”

In a second cable sent the following day he added that it was a gamble to send forces to the mainland of Europe to fight Germans at that time, but that it was better to suffer with the Greeks than make no attempt to help them, though none could guarantee that they might not have “to play the card of our evacuation strong suit”.

At these meetings it was decided to offer command of the proposed force to General Maitland Wilson, who had commanded the British army in North Africa in the opening stages of the offensive there, and was now Military Governor in Cyrenaica. Wavell sent a telegram to Wilson asking him to meet him at El Adem airfield near Tobruk next morning. Wilson was there when two aircraft arrived carrying Eden, Dill, Wavell, Longmore and their staffs to Athens. While the aircraft refuelled Wavell took Wilson aside and told him of his proposed appointment.

Later on the 22nd the delegates reached Athens. Before the military talks opened Koryzis assured the British envoys that in any circumstances Greece would resist German aggression. At a meeting attended by the British and Greek political and military leaders Eden said that Britain could offer three infantry divisions, the Polish Brigade, one armoured brigade and perhaps a second armoured brigade – a total of 100,000 men with 240 field guns, 202 anti-tank guns, 32 medium guns, 192 antiaircraft guns and 142 tanks. The British force would arrive in three instalments: first, one division and one armoured brigade; second, a division and the Polish Brigade; third, a division, and a second armoured brigade if required. Perhaps five additional air squadrons would be added

by the end of March and two of those already in Greece would be re-equipped with Hurricanes. (Actually one of the two single-engined fighter squadrons in Greece was already being equipped with Hurricanes.14)

General Papagos explained that the Greek army east of the Axios River, that is, in the area south of the Bulgarian frontier, included four divisions – the 12th in Thrace east of the Nestos River, the 18th between the Nestos and the Struma, the 7th and 14th west of the Struma. Together they comprised the Eastern Macedonian Army. Papagos added that if the Yugoslavs were willing to fight it would be fatal to them for the Greeks to abandon Salonika because only through that port could the Yugoslav Army be supplied. However, if Yugoslavia was neutral or allowed the German Army to march through her territory, only fortress troops should be left in eastern Macedonia and a line through the passes of Olympus, Veria and Edessa should be manned. To withdraw the Greek

troops to this line would require at least twenty days. After such a withdrawal there would be thirty-five Greek battalions in the Vermion–Olympus line, and a motor division in reserve at Larisa. He considered that eight divisions with a ninth in reserve would be needed to hold the proposed line.

Dill and Wavell considered that this Greek force – comprising, after certain new formations had been raised, five or six divisions, together with the four (or their equivalent) from Egypt – “appeared to offer a reasonable prospect of establishing an effective defence against German aggression in the north-east of Greece”. It was decided that Eden should send a telegram to Prince Paul of Yugoslavia seeking his views on the threat to Salonika, and it was agreed that “preparations should at once be made and put into execution to withdraw the Greek advanced troops in Thrace and Macedonia” to the Vermion-Olympus line.

At the conference, which continued until 3 o’clock in the morning, the Greek leaders finally agreed to accept the British offer.15 The Greeks welcomed the appointment of General Wilson to command the British force.

From Athens the delegation travelled to Cairo and thence to Ankara, where they arrived on 26th February. There Eden told the Turkish leaders that Britain was sending about four divisions to Greece and consequently had none to offer Turkey. The Turks said that they lacked adequate military equipment and were unwilling to forgo their neutrality and join in forming a Balkan front until they were better equipped. In any event they regarded the Yugoslav Government as unreliable.

The Turkish leaders feared both Russia and Germany, and Russia more than Germany, and, after the fall of France, seem to have been resolved to keep out of the conflict if they could. Even if they had ardently wished to enter the struggle, the soldiers who ruled Turkey were unlikely to imagine that war could be waged successfully without efficient equipment. In addition, the British defeats of 1940 made a particularly deep impression on the Turks because they themselves had been defeated by British armies in 1918. How powerful must be the German Army! Nevertheless, both Government and people were very friendly towards Britain (as many Australians were later to discover).16

On 1st March, while the conversations at Ankara were in progress, a report arrived that the German Army had begun to enter Bulgaria.17 The British envoys returned to Athens next day. There Mr Ronald Campbell,18 the British Minister at Belgrade, informed Mr Eden that the Yugoslav Government was frightened of Germany, but there was a chance that “if they knew our plans for aiding Greece they might be ready to help”.19 Major-General Heywood, head of the British Military Mission in Greece, told the British delegates that General Papagos was unwilling to order the withdrawal of his troops from eastern Macedonia to the Vermion–Olympus line until the Yugoslavs had defined their attitude, and that Papagos now said that it was too late to do so, the Germans having entered Bulgaria.

This news greatly disturbed the British leaders, because they had imagined that this withdrawal had already begun. At a meeting with Koryzis and Papagos, Dill said that he thought that it was understood at the previous conference that the movement was to begin at once. Papagos said that his understanding was that the movement was to await a reply from Yugoslavia; he had asked General Heywood each day whether a reply had been received from Belgrade and the answer was always no. Eden and Dill then urged Papagos to withdraw his divisions to the new line forthwith. Papagos replied that he could not now do so, because it would take fifteen days to carry out the move and, as the Germans had now entered Bulgaria, they might attack while the Greek troops were retiring. He added that transfer of troops from Albania was impossible, and proposed that the British force be disembarked at Salonika and sent forward to help his four divisions to hold the passes in Macedonia and defend Salonika. The British staff thus found themselves faced with a plan which they considered unsound and likely to result in the available forces being defeated in detail. At these meetings Eden and Dill found Papagos “unaccommodating and defeatist”20 At the request of Eden and Dill, Wavell hastened to Athens, arriving on 3rd March.

The British delegates decided “to enlist the aid of the King in this crisis” and on 4th March, at a meeting which the King attended, Papagos proposed as a compromise that the forces in eastern Macedonia (including the 7th, 14th and 18th Divisions) should remain in the Metaxas Line along the Bulgarian frontier, but that forces in western Thrace be withdrawn except for the garrisons of two forts and a few outposts; and that the 12th Division from western Thrace and the 20th and 19th, his only general reserve, should join the British force on the Vermion-Olympus position. In this way, if Yugoslavia fought, the troops in that position could move forward into the Metaxas Line. If Yugoslavia was neutral the three weak divisions and other smaller groups in eastern Macedonia (they possessed only twenty-one battalions between them) would hold the Metaxas Line as long as they could and then attempt to withdraw to the rear line. The British delegates considered that they now were faced with the choice of accepting Papagos’ plan “of attempting to dribble our forces piecemeal up to the Macedonian frontier”, or accepting his compromise, or withdrawing the offer of military support altogether. They decided that the first course would be disastrous for military reasons and the third disastrous for political reasons and agreed to the second, with some misgivings. (To adopt the third course would have entailed turning back the first large convoy of British troops, which was due at Piraeus, the port of Athens, on the 7th.) A condition of acceptance of Papagos’ compromise plan was that General Wilson should command the whole force on the Vermion-Olympus line. To prevent further misunderstanding the agreement was put in writing.

Thus the British delegates considered the “new and disturbing situation” which faced them on 2nd March so different from that which had been envisaged a week earlier that they contemplated abandoning the whole enterprise. In the telegrams sent to London at the time and in later writings by the participants too much seems to have been made of the facts that during these seven days no Greek soldiers were moved from the thinly-manned line on the Bulgarian border, and that once the Germans entered Bulgaria Papagos was unwilling to move his frontier force back. At least partial acceptance of Papagos’ contention that the forces should not be withdrawn from the line forward of Salonika until Yugoslavia’s policy had been clarified was implied by Eden on the 5th when he sent the Yugoslav Regent a letter urging him to join the Allies, and instructed the British Minister in Belgrade to inform the Regent that the defence of Salonika would depend on Yugoslavia’s attitude.21

On the same day Eden cabled to Churchill:

While recognising the dangers and difficulties of this solution, the military advisers did not consider it by any means a hopeless proposition to check and hold the German advance on this [the Vermion-Olympus] line, which is naturally strong

and with few approaches. A fighting withdrawal from this line through country eminently suitable for rearguard action should always be possible at the worst.22

On the British side the decision had been made and there could be no turning back; and in the minds of the Greeks the impending invasion was stirring ancient memories, and producing a mood, half mystical, half fatalistic and wholly heroic. In the right-wing newspaper Katherimne, for example, on 8th March, the day after cruisers had disembarked a few thousand men in British khaki at Piraeus, George Vlachos, an Ajax defying the lightning, wrote an open letter to Hitler in the course of which he said:

It appears – so the world is told by wireless propaganda – that the Germans want to invade Greece. We ask you why. If the operation against Greece was essential to Axis interests from the start ... Germans and Italians would have attacked us side by side. It is clear therefore that the attack on Greece was not a necessity for the Axis. Why is it so now? To prevent the creation of a front in the Balkans against Germany? But neither Serbia nor Turkey has any reason to let the war spread.

It is perhaps to save the Italians in Albania. But would not the Italians be finally and irrevocably defeated the moment even one German soldier sets foot in Greece? Would not all the world assert aloud that 45,000,000, after attacking our 8,000,000 were now begging for the help of another 85,000,000 to save them? Perhaps you will say ‘What about the British?’ We reply that we did not bring them here. It is the Italians who brought them to Greece. Do you wish us to bid them begone? Even so, let us tell them to go. But to whom should we tell this? To the living? For we hardly can tell the dead, those who fell in our mountains, who landed wounded in Attica while their country was burning at home, came here and fell here, and found tombs here. ...

What will your army do, your excellency, if, instead of divisions of infantry and artillery, Greece sends to garrison the frontiers a force of 20,000 wounded, legless, armless, bloody and bandaged to welcome it? Will your army strike at such a garrison? Small or great, the free army of Greeks will stand in Thrace as it stood in Epirus. It will fight. It will die there too. In Thrace it will await the return of that runner from Berlin who came five years ago and received the light of Olympia, and changed it into a bonfire, to bring death and destruction to a country small in size, but now made great, and which, after teaching the world how to live, must now teach it how to die.

What steps had been taken to inform and consult the Governments of Australia and New Zealand about the expedition? As mentioned above Mr Menzies and General Wavell had discussed the plan in general terms in Egypt about 12th February. Mr Menzies had been in London while the Athens conferences were held. He attended a Cabinet meeting on the 24th February – the day after that on which the Greek leaders accepted

the British offer. After the Cabinet meeting (at which Menzies noted an inclination on the part of the subordinate ministers to accept any proposal of Churchill’s without question) he sent a cable to the acting Prime Minister, Mr Fadden,23 outlining the plan and saying that the feeling in London was unanimously in favour of the expedition although it was realised that it would be risky and an evacuation might have to occur; in that event, Churchill considered, “the loss would be primarily one of material and that the bulk of the men could be got back to Egypt”. Menzies added that he would not favour the proposal if it was only “a forlorn hope”; but it was being undertaken on the advice of Wavell and Dill who were “able and cautious”. Churchill had said that, if Japan attacked, “adequate naval reinforcements would at once be dispatched to Australian waters” – an opinion which, Menzies considered, “must be a little discounted”.

Allowing for all these things (he concluded) though with some anxiety my own recommendation to my colleagues is that we should concur.

On the same day a cable which reached Fadden from the Dominions Office gave further details of the plan and added:

It was felt that we must take this only remaining chance of forming Balkan front and persuading Turkey and possibly Yugoslavia to enter the war on our side. From the strategical point of view the formation of Balkan front would have advantages of making Germany fight at the end of long lines of communication and expending her resources uneconomically, of interfering with Germany’s trade in the Balkans and particularly oil traffic from Rumania and of enabling us to establish platform for bombing of Italy and Rumanian oilfields. ... Finally from the political point of view, failure to help this small nation putting up a gallant fight against one aggressor and willing to defy another would have grave effect on public opinion throughout the world and particularly in the United States.

On the 26th the New Zealand Government (which had not yet received a copy of Eden’s cable about the Athens Conference of the 22nd) concurred in the expedition on the understanding that its division was fully equipped and accompanied by an armoured brigade. It added that it was

a matter of great satisfaction that the 2nd NZEF was ready to play the role for which it was formed, and that Australian and New Zealand forces were chosen to stand together.

Fadden cabled to Menzies on the 28th that the Australian War Cabinet concurred in the employment of two Australian divisions in Greece but added that consent “must be regarded as conditional on plans having been completed beforehand to ensure that evacuation, if necessitated, will be successfully undertaken and that shipping and other essential services will be available for this purpose if required”. This cable was repeated to the New Zealand Government.

In the following week, however, the news from the Middle East – the misunderstanding with Papagos, the closing of the Suez Canal as a result

of dropping of mines by enemy aircraft, the failure of a British attack on the island of Castellorizo in the Dodecanese,24 the identification of German aircraft over western Cyrenaica, and a rumoured landing of German armour at Tripoli – was causing alarm in London. On 4th March, Menzies asked that the Greek plan be re-examined. (Advanced elements of the Australian part of the force were due to sail on the 6th.)

On the 6th Churchill sent a gloomy cable to Eden. It contained the following passages:

Situation has indeed changed for worse. Failure of Papagos to act as agreed with you on February 22, obvious difficulty of his extricating his army from contact in Albania, and time-table of our possible movements furnished by Wavell, together with other adverse factors recited by Chiefs of Staff – e.g., postponement of Rhodes and closing of Canal – make it difficult for Cabinet to believe that we now have any power to avert fate of Greece unless Turkey and/or Yugoslavia come in, which seems most improbable. We have done our best to promote Balkan combination against Germany. We must be careful not to urge Greece against her better judgment into a hopeless resistance alone when we have only handfuls of troops which can reach scene in time. Grave Imperial issues are raised by committing New Zealand and Australian troops to an enterprise which, as you say, has become even more hazardous. We are bound to lay before the Dominions Governments your and Chiefs of Staff appreciation. Cannot forecast their assent to operation. We do not see any reasons for expecting success, except that of course we attach great weight to opinions of Dill and Wavell.25

Churchill added that he was reconsidering re-planning to the extent of concentrating on an advance on Tripoli.

Eden replied that “in the existing situation we are all agreed that the course advocated should be followed and help given to Greece. We devoutly trust therefore that no difficulties will arise with regard to the dispatch of Dominions forces as arranged.” At this stage, as Wavell wrote later, “there were practical difficulties in any reversal of plan; the troops were on the move and a change would have caused confusion”.26

The Chiefs of Staff informed Wavell on the 7th that “Cabinet decided to authorise you to proceed with operations and by doing so Cabinet accepts for it full responsibility. We will communicate with Australian and New Zealand Governments accordingly.”

Menzies then cabled to Fadden about the “changed and disturbing situation” in Greece on the return of Eden and Dill from Turkey and the written agreement with Papagos which had followed. He said that the Cabinet’s military advisers discounted the possibility of a successful thrust by a German armoured force in North Africa and believed that Benghazi could be held. He then underlined two considerations: first, that Eden and Dill had made a written agreement, and second, that Eden, Dill and Wavell considered that the “adventure” had “reasonable prospect of success”.

I pointed out to Cabinet (he continued) that while Australia was not likely to refuse to take a great risk in a good cause, we must inevitably feel some resentment at the notion that a Minister, not authorised by us, should make an agreement binding upon us which substantially modifies a proposal already accepted by us.

Menzies added that, as an outcome of this protest, Churchill had cabled to Eden that he must be able to tell Australia and New Zealand that the campaign was being undertaken not because of commitments made by a British Cabinet Minister in Athens but because Dill and the local commanders-in-chief were convinced that there was a “reasonable fighting chance”. Menzies reported that the Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East reaffirmed their belief in the proposal and that Generals Blamey and Freyberg (the commander of the New Zealand Division) were “agreeable”; and he added that it was important in relation to the world at large and particularly America not to abandon the Greeks “who have of all our Allies fought the most gallantly”. However, as will be seen later, neither Blamey nor Freyberg had been asked specifically whether they agreed or not.

Thus it was puzzling for the Australian Ministers when, on 9th March, a cable from General Blamey reached Mr Spender,27 the Minister for the Army, in which Blamey asked permission to submit his views before the AIF was committed; the Ministers knew that the AIF was already committed, and had been informed that Blamey was “agreeable”. Spender instructed Blamey to express his opinion, whereupon the leader of the AIF sent the following cable from Alexandria on the 10th:

British Forces immediately available consist of the 6th Australian Division, 7th Australian Division, New Zealand Division, one Armoured Brigade and ancillary troops. 7th Australian Division and the New Zealand Division have not been trained as complete divisions. Available later at unknown date one armoured division. Practically no other troops in the Middle East not fully engaged. Arrival of other formations from overseas indefinite owing to shipping difficulties. Movement now under orders will be completed probably in two months.

The Germans have as many divisions available as roads can carry and capacity can be greatly increased in two months. It is certain that within three or four months we must be prepared to meet overwhelming forces completely equipped and trained. Greek forces inadequate in numbers and equipment to deal with the first irruptions of the strong German Army. Air forces available 23 squadrons.28 German Air Force within close striking range of the proposed theatre of operations and large air force can be brought to bear early in the summer. In view of the Germans’ much proclaimed intention to drive us off the continent wherever we appear, landing of this small British force would be most welcome to them as it gives good reason to attack. The factors to be weighed are for:

(a) The effect of failure to reinforce Greece on opinion in Turkey, Yugoslavia and Greece; and against

(b) The effect of defeat and second evacuation if such be possible on opinion of the same countries and Japan.

Military operation extremely hazardous in view of the disparity between opposing forces in numbers and training.

Wavell had outlined the plan to Blamey on 18th February.29 When Blamey had said that it must be referred to Australia, Wavell replied that he had already discussed the proposed expedition to Greece with Mr Menzies. He did not ask for Blamey’s opinion.

In a discussion with Dill and Wavell in Cairo on the 6th March Eden, who had just received Churchill’s cable mentioned above, said that a “really disturbing question was the possible reluctance of the Dominions to engage in the venture”. Wavell said that he had informed Freyberg of the latest developments and Freyberg was prepared to go ahead, but Blamey had not yet been consulted. Consequently, later that day, Blamey was summoned to meet Dill and Wavell. In a letter to Spender written on 12th March, Blamey said that at this interview his views on the Greek expedition were again not sought. “I felt that I was receiving instructions,” he wrote. When Blamey asked what additional formations would be available he was told that perhaps one more armoured division would be added at an unknown date. Blamey reported that he had said to Wavell that he considered the enterprise most hazardous. In his letter he added that he considered that Dill and Wavell did not give enough weight either to the German capacity rapidly to improve communications in Greece or to German strength in the air. “As it would appear that it will be held that the operation must take place,” he concluded, “I beg to urge most strongly that vigorous action be taken to ensure that adequate forces for the task are provided at the most rapid rate possible.”30

It has been seen above that Blamey understood at this time that twenty-three air squadrons were to support the force. Menzies, however, had been told in London that there was accommodation in Greece for only thirteen though this might be increased by seven in two or three months. This was an optimistic estimate. Seven squadrons were then actually in Greece.31

After the interview with Blamey, Dill cabled to the Secretary for the Dominions that Wavell had explained to Blamey (and Freyberg) the additional risks involved in the venture in Greece and both had expressed their willingness to undertake the operations under the new conditions. Both Blamey and Freyberg, however, did not consider that Wavell had consulted them about the expedition. Freyberg said afterwards that he was only “given instructions to get ready to go”. In one capacity Blamey, like Freyberg, was a formation commander who had been and would be subordinate to one or other of Wavers army commanders in the field. But in another capacity each was the leader of a national force and a principal military adviser of a government. It was in this capacity that

Blamey and Freyberg were expected to advise their Governments on forthcoming operations – and, as will be seen below, were incurring the disapproval of those Governments for not being sufficiently swift and outspoken in their comments on the plans of their superior officers.

Blamey’s opinions greatly disturbed the Australian Cabinet. On the 18th March Fadden submitted the Greek problem to the Advisory War Council, but the Opposition members of that body declined to offer any opinion. The Opposition Leader (Mr Curtin) said that the decision had been made by the Government; if the Labour policy had been followed there would be no Australian troops in the Middle East.32 However, he added, failure to support Greece would have had a bad effect on Spain and on public opinion in the United States.

On 27th March Fadden cabled to Menzies:

My colleagues and I feel resentment that while some discussions appear to have taken place with the High Command, Blamey’s views as G.O.C. of the force which apparently is to take the major part in the operations should not have been sought and that he was not asked to express any opinion. This not only deeply affects the question of Empire relationship but also places us in an embarrassing situation with the Advisory War Council and with Cabinet, particularly as I have there stressed ... that General Blamey had agreed to the operation.

When Menzies sought a further assurance in London that there was a reasonable chance of success, Churchill informed him that the “real foundation” for the expedition was the estimate made on the spot of the “overwhelming moral and political repercussions of abandoning Greece” – a statement differing from that received earlier from the Dominions Office, which had suggested that the first consideration was a desire to establish a front in the Balkans. At the same time (on 29th March) Menzies cabled to his colleagues in Australia that Blamey knew his powers as G.O.C., AIF and should not have hesitated to offer his views. On the other hand Wavell had informed Blamey at the outset that he had discussed the plan with Menzies (before Blamey had heard of it) and that Menzies had already agreed. In a letter written to Menzies on 5th March Blamey had given his Prime Minister more than a hint of his dilemma – the choice between criticising his superiors’ policy and remaining silent despite his fears. He had written:

The plan is, of course, what I feared: piecemeal dispatch to Europe. I am not criticising the higher policy that has required it, but regret that it must take this dangerous form. However, we will give a very good account of ourselves.

So far as Blamey’s actions were concerned, Menzies’ attitude was modified when he knew more of the facts. At a meeting of the Advisory War Council in November 1941 he said that “quite frankly” he felt that some pains had been taken to suppress the critical views of Blamey about the proposed operation in Greece. It now appears, however, that Blamey

had not expressed to Wavell on 6th March such strongly-critical views as he expressed to Spender on the 12th.33

Freyberg also received a rebuke for not having spoken to his government sooner and more frankly. In June the New Zealand Prime Minister, Mr Fraser,34 cabled from Cairo to his acting Prime Minister:

I ... am surprised to learn now from Freyberg that he never considered the operation a feasible one, though, as I pointed out to him, his telegrams to us conveyed a contrary impression. In this connection he has drawn my attention to the difficulty of a subordinate commander criticising the plans of superior officers, but I have made it plain to him that in any future case where he doubts the propriety of a proposal he is to give the War Cabinet in Wellington full opportunity of considering the proposal, with his views on it, and that we understood that he would have done so in any case.

Both Dominion Governments reaffirmed their concurrence in the expedition to Greece, in spite of the disturbing news and opinions they now received. When the cables describing the situation which faced the British envoys on their return to Athens on 2nd March were repeated to the New Zealand Government it replied (on the 9th) that to abandon the Greeks to their fate “would be to destroy the moral basis of our cause and invite results greater in their potential damage to us than any failure of the contemplated operation”. It urged, however, the provision of the strongest possible sea and air escort for transports, and a “full and immediate consideration of the means of withdrawal both on land and at sea should this course unfortunately prove to be necessary”. Finally the New Zealand Government said that it assumed that the operations would not be undertaken unless the full British forces contemplated could “clearly be made available at the appropriate time”.

As a result of these representations about planning a withdrawal, which echoed those in the Australian cable of 28th February, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Pound,35 cabled to Admiral Cunningham on 24th March that:

Both the Australian and New Zealand Governments when agreeing to the use of their forces in Greece asked that adequate arrangements might be prepared in advance to withdraw their forces should this be necessary owing to the Greeks who are in line with our forces failing to hold up a German advance. The Chiefs of Staff are very reluctant to send a telegram on this subject, which might have a wide distribution, whilst forces are being put into Greece. It was decided therefore that I should send you, who are chiefly concerned, a personal telegram asking you to confirm that you have this possibility in mind in order that we may be able to reassure the Australian and New Zealand Governments.

Cunningham replied:

This problem has never been far from my thoughts since decision was reached to move into Greece. The question of evacuation must evidently depend upon the

military situation at the time which will obviously dictate what troops can be evacuated and part from which the evacuation can take place as well as type of ship that can be used. The simplest way to ensure an [amphibious] operation is to detain a large number of personnel ships in Mediterranean so as to have them immediately available. Such action appears to me to be a short-sighted policy, however, in view of shipping situation. I can only guarantee that everything possible will be done to withdraw the Dominion troops with British.36

Meanwhile Menzies in London and Blamey in Egypt had, each independently, raised another question: whether leadership of the force to be sent to Greece should not be given to the Australian commander. In the last week of February Blamey had suggested to Wavell that he, Blamey, should command the force because a majority of the troops were from the Dominions. On the 26th he reported this in a cable to Menzies. The Secretary of the Australian Department of Defence, Mr Shedden, who was accompanying Menzies, had already suggested to his leader that since most of the fighting strength of the force would be Australian, or certainly Dominion, Blamey should command. Consequently, on 1st March, Menzies made the proposal at a meeting of the British War Cabinet, but was informed that the bulk of the force would be United Kingdom troops. On the 5th March Blamey wrote to Menzies confirming his earlier cable and adding that he had raised the question of command “as a matter of principle and not as a personal matter”. He added that despite an estimate by Wavell that Australia would contribute only one-third of a force of 126,000, the Australian contribution was actual, the British largely a forecast, and some of the British units included were not even in existence. “Past experience,” he added, “has taught me to look with misgiving on a situation where British leaders have control of considerable bodies of first-class Dominion troops while Dominion commanders are excluded from all responsibility in control, planning and policy.”

As a senior staff officer in the old AIF Blamey had seen the gradual “Australianisation” of that force, in which, as late as December 1917, the corps commander, most of his staff, and the commanders of three of the five infantry divisions had been British officers; he knew that the replacement of these and other British senior officers had been achieved only as a result of political pressure. Blamey now controlled a corps of three divisions – the strongest single fighting formation under Wavell’s command; he, like Freyberg, was a very senior and experienced soldier; yet every front was commanded by a British general with a British staff: in the Western Desert first Wilson, then O’Connor, and later Neame; in the Sudan, Platt; in East Africa, Cunningham; and soon Wilson in Greece. No immediate change was made in the allotment of commands as a result of Blamey’s suggestion – Wilson had been in Athens preparing to take command since 4th March – but Menzies persisted with his proposal that

Blamey be promoted to a larger command, with results which will be recorded later.

There was another factor favouring the appointment of Blamey. Blamey’s staff had been carefully selected from a large field of highly-trained officers and was a team, having been in existence for nearly a year; Wilson’s had been hurriedly improvised in a theatre where the shortage of competent staff officers was acute, and in his own words was not “a going concern”. It had been collected after the Greeks had accepted the offer of British reinforcements in the last week of February. As his senior general staff officer Wilson obtained Brigadier Galloway, who had served him in a similar capacity when Wilson had commanded the army in Egypt. Galloway was then commanding the British brigade in Crete. As his senior administrative officer, he had Brigadier Brunskill,37 then serving in Palestine.

The imminent transfer of I Australian Corps to Greece faced Blamey with the immediate necessity of reorganising the administration of the AIF In his dual capacity as commander of the AIF as a whole and of the Australian Corps which was part of the AIF he had two separate tasks and two separate staffs to help him perform them. Some of his subordinates considered that steps to depute to a senior officer control of the Australian base organisations were overdue. In Greece he would be far separated from those organisations and unable to deal personally with day-by-day problems of administration affecting those parts of the AIF which were not in his corps. He chose Brigadier Plant,38 a regular officer hitherto leading the 24th Brigade, as commander of the “Rear Echelon, Headquarters of the AIF in the Middle East”, with the temporary rank of major-general. This appointment took effect from 5th March.

Meanwhile the trickling of the expeditionary force into Greece had continued. The air force, which by the end of February consisted of seven squadrons, was increased during March by one more squadron of Blenheim bombers, and early in April by one army cooperation squadron. It was now divided into three groups: one wing, eventually to include four squadrons, was in support of the forces that were preparing to resist the German invasion, another wing of two squadrons was in support of the Greeks on the Albanian front, and a third force of three squadrons and parts of two others was based in the Athens area under Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac’s direct command.39 In addition a handful of Swordfish aircraft

of the Fleet Air Arm arrived in Greece in March and were stationed at Paramythia whence they carried out raids on Durazzo and Valona, the Italians’ main supply ports in Albania.

On 5th March, in accordance with the pre-arranged plan, part of the 1st Armoured Brigade and advanced parties of I Australian Corps, and of the New Zealand and 6th Australian Divisions embarked for Greece in the cruisers Gloucester, York and Bonaventure. By 27th March the 1st Armoured Brigade, all but a few units of the New Zealand Division, and one brigade of Australians had landed in Greece. So far no weighty effort had been made by the Germans and Italians to interfere with the movement; only two small cargo ships had been sunk by German aircraft. Admiral Cunningham considered it likely, however, that the Italian fleet would eventually attack the convoy route, and on the 27th a report from the crew of a flying-boat that three Italian cruisers and a destroyer were 80 miles east of Sicily and steaming towards Crete suggested to him that some ,of the Italian heavy ships were at sea. He immediately took up the challenge. A convoy which was on its way to Piraeus was ordered to steam on until dusk and then reverse its course, and the Mediterranean Fleet sailed from Alexandria as soon as darkness fell. At dawn on the 28th an aircraft from the carrier Formidable reported four Italian cruisers and six destroyers; and a few hours later Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell’s40 Cruiser Squadron (the British cruisers Orion, Ajax and Gloucester and the Australian Perth) which was ahead of the main fleet sighted them. The Italian cruisers withdrew with Pridham-Wippell in pursuit and Cunningham and the battleships hastening after him. At 11 a.m. the cruisers sighted an Italian battleship, which was attacked by aircraft from the Formidable. It made off to the north-west. Meanwhile five cruisers and five destroyers were sighted 100 miles to the north. After further air attacks on the Italian battleship – now identified as the Vittorio Veneto – its speed was greatly reduced. An Italian cruiser, the Pola, was also hit by bombs. Darkness fell before Cunningham’s slow battleships could reach the Italian ships. At 10.25 p.m., however, the battleships suddenly came upon the Italian cruisers Fiume and Zara and promptly sank the Fiume and damaged the Zara. In the confused night fighting which followed, the destroyers, commanded by Captain Waller,41 R.A.N., in Stuart, finished off Zara and Pola and sank two destroyers; but the damaged Vittorio Veneto managed to increase her speed and escaped. The battle of Matapan, as it was later named, was a notable success. It was unlikely that the Italian fleet would venture out again for some time, and control of the eastern Mediterranean was to be of crucial importance to British fortunes in the next two months.

On the 8th March, the day after the first contingent of “Lustre Force”, as the force for Greece was named, reached Athens, a “Mr Hope” arrived there to see a “Mr Watt”. “Mr Hope” was Colonel Peresitch, an officer of the Yugoslav General Staff; “Mr Watt” was General Wilson, who, at the request of the Greek Government, was wearing plain clothes and using an assumed name lest the presence of a British commander in Greece should anger the Germans.42 The arrival of the Yugoslav officer was in belated response to repeated British requests for talks which would lead to a coordinated plan of action by the three Balkan states which the Germans had not yet overrun – Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia; hitherto the Yugoslav Government had not dared to arrange even Staff talks.

At that time what likelihood remained of realising the expectation that Yugoslavia might enter the alliance? Prince Paul, due to be Regent until the young King became 18 in September 1941, had succeeded in creating only a precarious balance between the powerful and antagonistic groups within the kingdom. Paul, a well-meaning but ineffective dictator, was acutely aware of the military weakness which the incompetent and corrupt administration had created and of its shortage of arms, particularly since Germany had acquired the Skoda munition factories in Czechoslovakia on which Yugoslavia had formerly relied. Above all he feared a crisis which would provide the radicals, and particularly the Communists (who had been ruthlessly suppressed since 1921) with an opportunity to unseat him. He decided to try temporising with Hitler. As soon as the Bulgarian Premier, on 1st March, signed the agreement with Germany which made Bulgaria a German dependency, Prince Paul paid a secret visit to Berchtesgaden. It was after his return that Colonel Peresitch visited Athens. It now seems evident that Peresitch’s task was to collect information which would help Paul to decide whether it would be Safer to throw in his lot with the Germans or the Allies.

From the Allied point of view Peresitch’s mission was unproductive. He emphasised the importance of maintaining communications with Yugoslavia through Salonika should Yugoslavia join the Allies – “proof,” wrote Papagos later “that the evacuation of Eastern Macedonia and the abandonment of Salonika were inadvisable as long as the hope of Yugoslavia coming in had not entirely disappeared.”43 But Peresitch was not communicative and he had no power to commit the Yugoslav General Staff to a plan.

At this stage Wilson was disturbed by the possibility of the German attack descending before his force had been concentrated. Major-General Arthur Smith, who was General Wavell’s Chief of Staff, had come to Athens for the talks with Peresitch, and Wilson discussed this possibility with him and

asked for a team of officers whose job would be to reconnoitre positions on to

which we could fall back, if necessary, having none to spare from our own troops on whom innumerable calls were being made.44

While these talks were in progress in Athens the Italian army in Albania, on 9th March, opened a large-scale offensive in the central sector of the front. In the next sixteen days the Italians employed twelve divisions in a series of attacks against six Greek divisions without gaining any ground. At this stage about one-third of the fighting formations of the whole Italian Army had been committed in Albania against a Greek army inferior in numbers and vastly inferior in equipment.

The deliberations in Belgrade which followed Prince Paul’s visit to Germany and Peresitch’s to Athens lasted until 24th March. At length the Yugoslav leaders decided to throw in their lot with Germany. On the 24th the Premier, M. Cvetkovic, and the Foreign Minister, M. Cincar-Markovic, left for Vienna where they signed an agreement to adhere to the Tripartite Pact between Germany, Italy and Japan. This news became known in Belgrade two days later. That night a group representing elements which detested Germany, Italy, and Prince Paul and his clique, took swift action. They arrested Cvetkovic, Cincar-Markovic and other senior members of the Government, proclaimed King Peter’s accession, and eventually sent Paul and his family into exile.45 The party which had achieved this coup d’état was led by younger officers of the air force and army, and was supported by students and many of the staff of the university, the Orthodox clergy, and the Serbian parties generally. The new Cabinet, headed by the Serb General Simovic, who commanded the air force, was widely representative.

When the news arrived in Athens that Yugoslavia had joined the Axis, plans were discussed between Papagos and Wilson for hurriedly bringing the Greek divisions on the Bulgarian frontier and the Nestos River – the Doiran-Nestos line – back to the Vermion-Olympus line. Soon, however, news arrived of the possibility of a coup in Yugoslavia, and thereupon Papagos urged that the whole Allied force should be advanced to the Doiran-Nestos line. Wilson replied that this was not possible. He explained to the Greeks that “to advance all the troops ... into Eastern Macedonia (a distance averaging 125-150 miles) with the British element only partly concentrated in face of the hourly expected German attack was to court disaster”. When news arrived of the actual coup in Belgrade, Wilson was making a reconnaissance in northern Greece.

The coup in Yugoslavia vastly increased Churchill’s optimism; so much so that, on 30th March, he cabled to Fadden in Australia that renewed hope could be cherished of forming a Balkan front with Turkey, and “comprising about seventy Allied divisions from the four Powers concerned”. (This was in spite of the fact that the Turks had made it clear that they would remain neutral unless attacked.)

The maintenance of such a front demanded the holding of Salonika and the roads and railways leading from Greece into Yugoslavia. As a result of Papagos’ tenacity there was still a substantial Greek force on the Bulgarian frontier, and, although the British troops were being deployed on a line west of Salonika and of the railways leading into Yugoslavia, Greek troops were still forward of them, so that in renewed discussions with the Yugoslavs their supply through Salonika could be discussed as a practical proposal.

With the object of renewing efforts to obtain Yugoslav cooperation, Eden and Dill, who had been delayed at Malta on the way home, flew to Athens, where they conferred with Wilson on 28th and 30th March and agreed that if the Yugoslavs would join the Allies it would probably be essential to hold at least the line covering the Struma River and the Doiran Gap, through which the road and railway from Salonika entered Yugoslavia. At a meeting with the Greek leaders it was agreed to tell the Yugoslavs that if they would attack into Bulgaria and Albania when the Germans advanced into Greece, the Allies would reinforce the line of the Bulgarian frontier and the Nestos River. Papagos informed the British leaders that the Yugoslavs had 24 divisions of infantry and three of cavalry. It was this potentially powerful army that he had always wanted to have on his northern flank. With its help he could swiftly dispose of the Italians in Albania and then might reasonably hope to bog down the Germans on the eastern flank.

On 31st March General Dill flew to Belgrade where he met the Yugoslav leaders. He informed them that the British force in Greece would ultimately reach 150,000 and was then “somewhere near the halfway mark”.46 When the Yugoslavs asked whether the British force would concentrate in the Doiran Gap Dill replied that the Allies had contemplated holding the line of the Bulgarian frontier and the Nestos but meanwhile were established on the Vermion-Olympus line. They could not advance to the forward line without assurances of Yugoslav cooperation. The Yugoslav leaders said that they could not sign any undertaking to help Greece without first consulting the Government as a whole. General Dill said that Britain would give Yugoslavia what help she could. It was arranged that a staff talk between Papagos, Wilson, D’Albiac and General Jankovic, the Yugoslav director of military operations, should be held near Florina in Greece on the 3rd.

This military staff meeting, begun on the night of the 3rd and finished some time before dawn next day, was held at the Kenali railway station just north of the Greek frontier. Jankovic said that possession of Salonika was vital to Yugoslavia. He proposed that the Greek forces east of the Struma and in the Metaxas Line should remain on the defensive, gaining time for the Yugoslavs (who had only four divisions in the south) and the British force to strike the right flank of the German advance in the Struma Valley; the British force would thus form a link between Greek

and Yugoslav armies in the area of Lake Doiran-Struma. Jankovic and Papagos also discussed and were in agreement on a plan whereby Yugoslav forces should cooperate with the Greeks in a converging attack on Tirana and Valona in Albania, which, if successful, would expel the Italian army from that country. When Wilson explained that although the British force would finally include three divisions and an armoured brigade, at the moment it comprised only one division, part of a second and an armoured brigade, Jankovic said that General Dill had mentioned four divisions and an armoured brigade. Jankovic’s disappointment was evident. Wilson said that he could not reinforce the Doiran area without reconnaissance. He urged that the Yugoslavs, who had few anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons, should fight the Germans in the mountains. He wrote afterwards that Jankovic

gave one the idea that the Yugoslav Army was already in a defeatist mood at the idea of a blitz attack by the Germans and it was evident that its organisation was pretty confused.47

Discussing this meeting in the train as it was travelling back to Athens Papagos and Wilson agreed that the situation remained as before and that they should make sure of the Vermion-Olympus line. When enough Australian troops had arrived to relieve the 12th Greek Division in that line, that division should be moved forward to the left of the Doiran-Nestos line, but this could not be done for eight days.

The discussion with Jankovic made Wilson very doubtful of the value of the Yugoslav Army and he “began to think more and more about the Monastir Gap” through which the Germans could advance into Greece across the rear of the Vermion-Olympus line if the Yugoslavs collapsed.

On 31st March Blamey, now in Greece, where he had reconnoitred the Vermion-Olympus line, sent a cable to the Australian Government which was more in tune with Wilson’s worried reflections than with Churchill’s hopeful cable of the previous day picturing a Balkan front of 70 divisions. Blamey said that the weakness of the position was in the north where an advance through Yugoslavia or the Edessa Pass would entail the loss of Florina and give the Germans access to the area south from Florina to Servia, which was suitable for armoured units. “The only line of communication available is the railway Athens-Larisa and thence forward by road. In both cases these are defiles which can be subjected to intense air attack at vital points. Air and ground anti-aircraft defences hopelessly inadequate and serious dislocation of lines of communication likely. Can only be met by building up reserves in forward area.” He pointed out that the Germans had from twenty-three to twenty-five divisions in Bulgaria, could concentrate from eleven to thirteen of these against the four Greek divisions on the frontier, then turn with from six to seven against the Vermion-Olympus line, which was held by one armoured brigade, the New Zealand Division and two Greek divisions.

Thus by 4th April hope of enlisting Yugoslavia in a coordinated plan seemed slender. About half of the small part of the Greek Army which was available for defence against a German invasion was on the frontier; the other half was going into position on a line some 120 miles to the rear. Of the three British Dominion divisions which were to help man this rearward line only one and a half had yet arrived in Greece. Papagos who would command the whole Allied force had contended that a total of nine British and Greek divisions with full air support would be needed to establish a “reasonably strong front”; he had eight divisions, of which six were far below strength, and weak air support. Wilson, who commanded the British and Greek force in the rearward position, had asked for a staff to reconnoitre lines of withdrawal, and plans were already being made to embark the British force if necessary. Blamey, commanding the main part of the British expedition, considered it would meet “overwhelming” German forces.