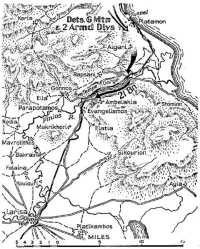

Chapter 5: The Critical Days

Early on 16th April the situation of the Anzac Corps was transformed by a realisation that the main threat was to its own eastern flank and not the western flank where the Greeks stood. Hitherto it had appeared that the Olympus passes could be held without great difficulty long enough to enable the Anzac force to disengage in good order, but there had been keen anxiety lest the Germans should advance rapidly through the mountains, along the Grevena road and descend on the plain of Thessaly before the corps had withdrawn through Larisa. From the 14th onwards, however, a series of disturbing reports reached Anzac Corps headquarters from the 21st New Zealand Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Macky1) at the Platamon tunnel on the coastal pass east of Olympus, particularly a message that 150 tanks could be seen and the German attack was being pushed hard.

The battalion was attacked by motor-cycle troops during the 15th but repulsed the enemy with heavy loss. A German armoured regiment arrived on the evening of that day. The coastal and the inland flank of the battalion was attacked but held its ground. The Germans were reinforced during the night of the 15th–16th until (as we now know) they had assembled a tank battalion, an infantry battalion and a battalion of motor-cycle troops. Infantry attacked the left New Zealand company at dawn and the tanks attacked along the coast at 9 a.m. When his left company had been out of touch for some time, and two companies farther down the hill were being fired on from the flank and rear, Colonel Macky gave the order to retire. The withdrawal was covered by the reserve company, which was on a ridge south of that pierced by the tunnel. Soon after 10 a.m. Macky reported by wireless to corps headquarters (he had been placed directly under General Blamey’s command so that General Freyberg would be freer to organise the withdrawal of the remainder of his division) that he could no longer hold; the battalion’s wireless set was then destroyed and most of the telephone cable abandoned.

Already, at 1 a.m., Blamey had ordered his artillery commander, Brigadier Clowes, a cool and experienced regular soldier, to visit the 21st and take any action he considered necessary. Clowes drove during the night to Freyberg’s headquarters and thence to Larisa, but there were delays on the road and it was after 8 a.m. before he set out from Larisa towards Platamon. About 11 a.m. he reached a ferry at the eastern end of the Pinios gorge,2 found the New Zealand battalion there and learnt

from Macky that one company and part of another were missing. Macky had intended to hold a new position about one mile south of Platamon, but this was found to be impracticable, and the retirement had continued to the mouth of the gorge. At that point the only way across was by a flat-bottomed barge pulled by hand between banks from 20 to 30 feet high. Clowes instructed Macky that it was “essential to deny the gorge to the enemy till 19th April even if it meant extinction”, and that support would arrive within twenty-four hours. He ordered him to sink the ferry-boat when all his men had crossed, and hold the western end of the gorge to the last, paying special attention to the high ground north of the river. He predicted that sooner or later the enemy would move along these slopes and outflank any troops in the gorge. He advised Macky, if the broke through the gorge, to fall back to a position astride the point where the road and railway crossed seven miles south of the western exit.

It was late in the afternoon before Macky’s men had been ferried across. The four guns with their tractors and limbers were too heavy for the barge, but the heavy vehicles were driven over the railway bridge. The guns swayed too much to be towed across and were man-handled down the bank to the ferry and hauled up the opposite bank. The ferry was then sunk, “but not before a large flock of sheep and goats and their two shepherdesses had been ferried across”.

After Clowes had been sent off to take charge of the threatened flank the next problem of Blamey and his staff was to find reinforcements to stop the gap there. The last reserve, Savige’s brigade, had been used

partly to form the flank guard at Kalabaka and partly to supplement Lee’s force astride the road at Domokos. When, still in the early hours, other disturbing signals had arrived from the right flank, Brigadier Rowell ordered, from Blamey’s headquarters, that the first available battalion of the 16th Brigade be stopped on the road so that it could be sent to the Pinios Gorge. Consequently, when the weary men of the 2/2nd Battalion arrived at the main road at 10 o’clock that morning, after marching since 2 a.m., many on blistered feet and most with worn-out boots and torn clothing, Lieut-Colonel Chilton was met by a liaison officer with orders to report to corps. There Rowell told him that the 21st Battalion’s final signals had been disquieting and he did not know whether any of the battalion would be left. Brigadier Clowes, he said, had gone out to discover what had happened and had not yet returned.3 A battery of field artillery, a troop of three anti-tank guns and the carriers of two battalions (the 2/5th and 2/11th) would be placed under Chilton’s command, and he would go to the Elatia area south-west of the gorge and take steps to hold the western exit possibly for three or four days. Chilton was greatly impressed and encouraged by the air of calm and cheerful efficiency at corps headquarters.

Chilton set off in a car. Near Larisa he met Clowes returning and learnt that the 21st Battalion was withdrawing into the gorge. After having left his adjutant, Captain Goslett,4 to collect his battalion’s vehicles and arrange for guides through the town – for the roads were crowded with trucks and some of the streets in Larisa were blocked by craters and rubble – Chilton went on to Tempe with his carrier platoon. At dusk he met Colonel Macky, who told him that his men, who were very fatigued, were bivouacked in the village with one platoon covering the road three miles forward in the gorge. His battalion, he said, had suffered only thirty-five casualties at Platamon but had lost much equipment there, including all the signal gear. During the night the remainder of Chilton’s weary battalion and the artillery arrived in their vehicles.

Meanwhile Blamey had decided to send Brigadier Allen to take command of a brigade group, consisting of two of his own battalions (including the 2/2nd), the 21st New Zealand, and artillery and other detachments, in the Pinios Gorge. On the 16th Allen was in the foothills of Olympus gaining touch with his 2/1st Battalion, and it was 2 a.m. on the 17th before he arrived at corps headquarters for orders. There Rowell “who was endeavouring to get some sleep under a tree, with the aid of a torch and map, gave Brig. instructions to move on to Pinios Gorge”.5 Allen would take command of all troops there. Eventually these were to include the 2/2nd, 2/3rd and 21st Battalions, 4th Field Regiment (less a battery), a troop of New Zealand 2-pounders, seven carriers of the 2/5th Battalion and four of the 2/11th. His task was to prevent the enemy taking Larisa

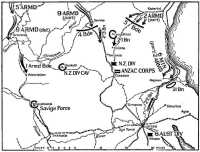

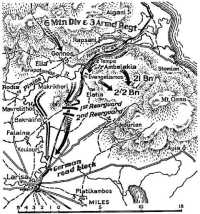

Sketch made by Brigadier Rowell on 16th April before writing the orders for the withdrawal to Thermopylae

from the east. At this stage Allen’s 2/3rd Battalion was still marching out of the mountains but due to reach the main road that night; its orders were to rendezvous at a point west of Larisa, so, after leaving Rowell, Allen had to go to this point to pass on the new orders. The 2/1st was still at Levadhion high on Olympus, with its vehicles on the Katerini–Olympus pass road nine arduous miles away; on arrival there it came directly under the divisional commander.

Meanwhile the plans for the withdrawal of the corps were elaborated. In an order late on the night of the 16th Blamey defined the division of responsibility between Generals Mackay and Freyberg during the leapfrogging move back to Thermopylae. Mackay would protect the flanks

of the New Zealand Division as far south as an east-west line through Larisa and would control the withdrawal through Domokos to Thermopylae of Savige Force and the Zarkos Force, and finally of Lee Force; the 1st Armoured Brigade would cover the withdrawal of Savige Force to Larisa and thereafter the withdrawal of the 6th Division under whose command it would come; Freyberg would control the withdrawal of Allen Force which was to move along the same route as the New Zealand Division. Blamey further decided to place all engineers under corps control and a conference was held at the junction of the Katerini and Servia roads between Brigadier Steele and Colonel Lucas (Australian) and Colonel Clifton6 (New Zealand). Blamey hoped that the enemy could be delayed sufficiently to enable the force to conform to the following time-table: 4th New Zealand Brigade to vacate Servia Pass and 5th New Zealand Brigade to vacate Olympus Pass on the night of the 17th–18th, 6th New Zealand to vacate the Elasson position on the night of 18th–19th;7 Savige Force to withdraw the main bodies to Zarkos on the 17th–18th leaving delaying parties at Kalabaka during the 18th. The final withdrawal of Savige and Allen Forces was to be arranged between Freyberg and Mackay.8

Between the force which Allen was to assemble on the south bank of the Pinios, and the right flank of Brigadier Hargest’s9 5th Brigade, 20 miles away in the Olympus Pass, rose the snow-capped heights of Mount Olympus. Hargest was on its northern slopes; the force at Tempe was in the gorge which bounds the mountain on the south. On a large-scale map Olympus seemed an impassable barrier, but in fact several tracks wound over its slopes and one of these – the track from Skala Leptokarias on the coast, by way of Karya and Gonnos to the Larisa road10 – offered a

promising line of advance for German mountain troops. Similarly on the left of the New Zealanders in the Olympus Pass another main track led over the northern buttress of the mountain through Skoteina and Levadhion. (It was along this track that the 2/1st Battalion had withdrawn.) Thus the German mountain troops might decide to advance not only through the main passes, but also along these lesser tracks, one south one north of Hargest’s brigade.

On the night of the 15th–16th (while the 21st Battalion was being heavily attacked at Platamon) men in the forward posts of the 22nd Battalion, the centre battalion of Hargest’s brigade, astride the road through the Olympus Pass, heard Germans calling out in English. Thinking it was a ruse to draw fire they remained silent but in the morning found that these Germans had been cutting their wire and lifting mines. Soon after dawn the 22nd was lightly attacked; but the German infantry withdrew when artillery and mortars fired on them. Behind them were many waggons and tanks. Under cover of this attack the Germans had brought up mortars and infantry guns, which were very troublesome. The commanding officer of the supporting field regiment, Lieut-Colonel Fraser,11 came forward and directed fire which silenced a particularly well-sited mortar.

The Maoris on the left could now see vehicles crowding the road for 14 miles back, as far as Katerini, the first three miles of the column consisting mainly of tanks, troop carriers and motor-cycles. About 8.30 a.m. the leading vehicles swiftly moved forward. The New Zealand artillery observer boldly dropped his range by 800 yards and broke the attack. Soon fourteen vehicles, including two tanks, had been destroyed. From 11 a.m. until 3 p.m. rain and mist made it impossible to see more than a few hundred yards. When the weather cleared the Maoris saw Germans streaming into the deep ravine of the Mavroneri towards the left flank, and beyond effective range.

On the right the 23rd Battalion was in heavy mist. Enemy parties tried to move round the right flank but were thwarted by the defending infantry and gunners until late in the afternoon, when their advance in this direction threatened to hamper the withdrawal. However, reinforcements arrived and drove the enemy back. On the Maoris’ sector the enemy had now moved across to the front of the left company and, in the twilight, were forming up in strength on the far side of a ravine through which ran the road to Skoteina. The slopes on both sides were covered with scrub and stunted trees and immediate fields of fire were not more than twenty yards, though the opposite bank could be covered. Suddenly enemy troops began to swarm on to the road and dash along it. They were fired on and fell back, but in a few moments the forward Maori section was

Dusk, 16th April

sharply bombarded with mortar bombs, grenades and bullets, and the German mountain troops clambered up the hill and, at heavy cost, overran the foremost Maori posts. However, the enemy – probably two companies – had lost heavily and the survivors were gradually pushed back into the ravine. This flank was reinforced and the situation became stable, but the battalion was an hour and a half late in beginning to withdraw along greasy tracks in pitch darkness.

The other battalions withdrew more or less according to plan. The route of the 23rd climbed to 2,000 feet above the pass over a shoulder of Mount Olympus and the track was deep in mud. The nine 2-pounders supporting them had been doomed when the action began and after an effort to man-handle them out, were reluctantly tipped over cliffs. Ten carriers and twenty trucks were also abandoned. Craters were blown in the road and the new position was occupied astride the top of the pass seven miles to the south-west (through Ayios Dimitrios and Kokkinoplos) where the brigade was to hold until its withdrawal to the Thermopylae position the following night. As an additional precaution during this withdrawal Freyberg had on the 16th established a force of anti-tank guns, machine-guns, and three platoons of carriers under Lieut-Colonel Duff12 to cover the withdrawal from the Servia and Olympus Passes.

It took up positions north of Elasson near the village of Elevtherokhorion where the road from Servia joins that from Katerini. Next day two squadrons of the divisional cavalry regiment, which, since the 15th, had been about Deskati guarding a side road which entered the Anzac area from Grevena, took over the role of Duff Force. The carriers of the third squadron remained about Deskati and the armoured cars of the squadron were ordered south to join Allen.

In the Servia Pass the enemy, after the failure of his ill-managed attempts to rush the pass on the 15th, made no further infantry attacks on the 16th, though the artillery duel and the aerial bombing continued. In the morning of the 16th the 2/2nd Field Regiment pulled out its guns and withdrew to join the flank guard at Zarkos. Its orders were to travel by the Servia Pass but, in response to a warning by a New Zealand officer that any vehicles moving along the exposed stretch of road near Prosilion immediately came under accurate fire from the German guns, this regiment (and also some detachments of Vasey’s brigade) made a long detour through Karperon and Deskati – an action of which Mackay strongly disapproved. In spite of this the 2/2nd arrived at Zarkos early in the afternoon. After dark on the 16th the 2/3rd Field Regiment withdrew to Elasson to support the 6th New Zealand Brigade in its rearguard position there. In the night drive up the zigzag road one gun fell over the cliff and had to be abandoned – the third gun the regiment had lost since the fighting began. Puttick’s left battalion – the 20th – was withdrawn on the night 16th–17th to a position astride the road at Lava to cover the retirement of the brigade the following night, and the 19th swung its left flank south of Prosilion.

Meanwhile Savige, perched in the mountains on the left flank, had deployed his force at Kalabaka. On the 15th he had examined the defensive position allotted to him near the snow line west of the junction of the Grevena and Metsovon roads and rejected it on the grounds that it was in country which offered cover and easy movement to enemy tanks and infantry and could be outflanked. He decided instead to hold a line two miles and a half west of Kalabaka where his left would be on a wide stream – the upper Pinios River – his front covered by a narrower stream and his right, though “tender”, could be defended in depth.

In the course of his visit to Savige on the afternoon of the 15th General Wilson had told him that his force might have to get away from Kalabaka in a hurry and that he would need enough vehicles to lift all his men at once. He advised him to keep in touch with the British convoy of motor trucks which was bringing Greek troops into his area from the west. Savige did so and arranged that he should receive eighty vehicles from this source. On the 16th, however, at the urgent request of liaison officers from corps headquarters he handed thirty of these to corps. It was from these officers that he first learnt of the general withdrawal.

The town of Kalabaka was now in turmoil. It nestles between a big cliff “remarkably like Gibraltar in appearance” and the Pinios River. The British medium artillerymen were established at the eastern end of

the town and at the foot of the cliff. At night clusters of dwellings on the cliff face were lit up and the lights flickered on and off as doors or curtains were opened or shut. The gunners began to interpret these lights as signals by a Fifth Column, and constant challenges were given ands occasional bursts of Bren gun fire directed at the cliff dwellers.

Savige did not have enough troops to police the town and

the straggling Greek troops, without food, took what they could from the shops and houses (he wrote afterwards). The locals no doubt fired some shots, and possibly some of the few Greek troops with rifles joined in the fun. I believe that, while Greek troops were intent on robbing civilians, the civilians raided the depots to collect rifles and ammunition to protect themselves. Kerosene was particularly short and civilians took their current and reserve needs from the now-unprotected dumps, from which Greek troops had fled to join the procession eastwards.

So far Savige had had no direct contact with the 1st Armoured Brigade, farther north. On the 16th a liaison officer from Wilson’s headquarters, returning from a visit to that brigade informed him that the head of its column would pass through Kalabaka that day on the way to Larisa. During the afternoon its leading vehicles began to move through the town. Savige had some anxiety whether the bridge over the Venetikos River, just south of Grevena, would be blown – a responsibility of the armoured brigade. He picked a resolute-looking subaltern named Hughes of the 292nd Field Company, a British unit in his area, and asked him to collect some volunteers to go forward and ensure that the bridge had been blown. Hughes found the bridge intact but the charges ready for firing. He fired them and destroyed the bridge, returning next day.13

At 9 p.m. Colonel Wells14 arrived at Kalabaka from Blamey’s headquarters with instructions that Savige Force would hold its positions until midnight on the 18th–19th, and that the 1st Armoured Brigade would cover its withdrawal, the senior of the two brigadiers to command the combined force.

At 1.30 a.m. on the 16th, however, Brigadier Charrington’s brigade major had left General Wilson’s headquarters with entirely different orders for that brigade: that it should withdraw into reserve behind the Thermopylae line at Atalandi.

The main body of the 1st Armoured Brigade had reached Velemistion that evening having travelled some 20 miles in nine hours along a narrow, cratered road deep in mud, crowded with refugees, and strewn with abandoned vehicles and weapons. Rain and mist had concealed the column from German aircraft, but progress was slow because of the congestion and because detours had to be dug round stretches of road that were otherwise impassable. On the morning of the 17th the brigade continued to move through Kalabaka.

At this stage a misunderstanding developed as to the role of the armoured brigade. Brigadier Charrington’s brigade major, when he arrived at Kalabaka, received a message telling him to remain there until the brigade arrived. He spent the 16th there and in the afternoon was asked whether he could arrange with Brigadier Charrington that the armoured brigade should cover the withdrawal of Savige Force. In his opinion it was impossible in view of the orders he had received from General Wilson for the whole brigade to cooperate, but he finally agreed that it should detach a small party to guard the bridge and cover the withdrawal.

About 10 a.m. on the 17th Brigadier Charrington arrived, and, after some discussion, this arrangement was confirmed. The result was that the detachment – a carrier platoon (Rangers), a troop of anti-tank guns, a platoon of New Zealand machine-gunners and two troops of the New Zealand Cavalry – remained at the Velemistion bridge forward of Savige’s position, and the armoured brigade as a whole continued to withdraw. At this stage (10 a.m. on the 17th) neither Charrington nor Savige had received Blamey’s written order of 6 p.m. on the 16th, but, as mentioned above, Savige had been told by the liaison officer the previous afternoon that the armoured brigade was to cover his withdrawal, both brigades coming under the command of the senior brigadier.15 The written order reached him at 12.30 p.m. on the 17th; that afternoon he informed corps headquarters that the armoured brigade was already withdrawing.

The armoured regiment of Charrington’s brigade had been sorely tried by the mechanical faults that developed in their worn tanks and by defective tracks with which these were fitted. The break-down of most of the tanks that survived the rearguard actions in the Florina Valley was largely due to “W” Group’s faulty decision to withdraw the brigade over a rough mountain road which had not been reconnoitred, instead of down the main road. This laborious journey had wearied the men, and the fact that for days the brigade had struggled along a road crowded with retreating Greeks and Yugoslavs had depressed their spirits.

It was on the 16th that General Wilson met General Papagos at Lamia and informed him of his decision to withdraw to Thermopylae. In Athens that day the Metropolitan Bishop of Yannina, a power in the land, urged the Prime Minister, M. Koryzis, to give up the struggle. Since the 14th senior commanders in Epirus had been making the same proposal.16 On the 15th indefinite leave had been given to Greek troops in rear areas and many of these were now wandering round the streets of Athens. That morning General Wavell had sent a message to Wilson that “we must of course continue to fight in close cooperation with Greeks but from news

here it looks as if early further withdrawal necessary”. Further withdrawal could only mean embarkation from Greece.

In most of Thessaly the 17th of April, like the 16th, began with drizzling rain and mist, so that again the crowded traffic on the main road was often concealed from German aircraft, and the clouds lying low on the hills made flying dangerous; in the afternoon, however, the sky cleared in some areas and German aircraft attacked the columns of trucks. The road was packed with vehicles – fighting troops moving back to the Domokos position (the weary men lying sleeping, packed on the floor of each vehicle), depot units withdrawing to Thermopylae and a few, very few, Greek trucks, cars and aged omnibuses crowded with troops. Against this stream were moving the vehicles which were carrying supplies forward. Frequently the two processions became locked and movement ceased until the tangle had been straightened out. Where the narrow road zigzagged over the pass – between Elasson and Tirnavos, or at Pharsala or Domokos – trucks were packed head to tail for hours on end, the procession moving for a mile or two, then stopping, then moving on, then stopping again. The machine-gunning of vehicles on the 14th and 15th had made many of the drivers nervous, and the appearance of an aircraft in the distance – sometimes a Greek or a British machine – would cause a convoy to halt while drivers and passengers jumped from the trucks and ran off the road to temporary cover in the fields. Beside the road plodded an ever-increasing number of Greek soldiers, shabby and weary, and heavily laden with kit. Some wore cloth caps, some Italian helmets, some British helmets. There were Greeks riding donkeys and Greek cavalrymen with their cloaks shining in the rain riding tired horses whose heads drooped. Occasionally would be seen a civilian car loaded with refugees, a pair of carts being dragged by a farm tractor, a farm cart carrying a whole family and perhaps the bodies of a few fowls dangling at the back. Here and there were well-cared-for and neatly-uniformed Greek police with motor-cycles and side-cars.

Larisa, the largest town on the road, through which all must pass, was now in ruins, the damage having been caused partly by earthquake and partly by air attack. Notice boards marked spots where unexploded bombs had buried themselves. The bridge across the Pinios at the northern entrance to Larisa was witness to the improbability of a bomber hitting a smallish target. Within a hundred yards a dozen bomb craters gaped, yet it was still intact.

Larisa was the site of a well-stocked British canteen whose staff had abandoned it. This might have had serious consequences. On the night of the 16th and during the 17th many truck-loads of Anzac and British troops each loaded on a case of beer. Some drivers drank a bottle or two and, being extremely weary and hungry, went to sleep farther along the road and could not be wakened.

Not only were the roads becoming dangerously congested but the railways were disorganised. The confusion can be illustrated by the

experiences of the two battalions of the 17th Australian Brigade on their move from Athens to Thessaly. The train carrying the 2/6th stopped south of Pharsala for nine hours on the night of the 14th–15th because the crew feared that it might be attacked from the air. The train bearing the 2/7th was under a prolonged attack from the air near Larisa on the following night, and the crew disappeared. However, in the early hours of the morning some Victorian railwaymen led by Corporal “Jock” Taylor, who had shown himself in the fighting in Cyrenaica to be an outstandingly cool and intrepid leader, Corporal Melville,17 and Private Naismith,18 fired one engine and left it with the fire-box door open as a decoy to delude the German aircraft and, while bombers were attacking it, manned another engine 500 yards away and made up a train into which the battalion was loaded and taken to Domokos.

In the front line, however, the 17th passed relatively quietly. This comparative calm demonstrated how effectively a retiring force moving back by carefully-planned stages into well-picked positions, and demolishing roads and bridges behind it, could delay an advancing army. Before the enemy could locate and counter the defending artillery in the Servia and Katerini Passes, the defenders had moved from the foot to the top of each pass, cratering the road. The Germans had then to probe forward and find the new positions, to repair the road and bring up their guns – because, where they could not deploy their tanks, they could do nothing without their guns.

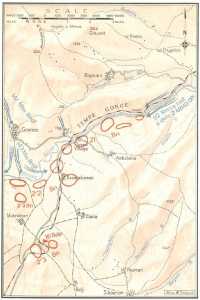

In the Pinios Gorge during the 17th Colonels Chilton, Macky and Parkinson19 were able to prepare their defences with relatively little interruption, although there was no time for elaborate reconnaissance or planning, nor time to move farther forward astride the defile if that had been considered desirable. Before Allen arrived the young veteran Chilton had deployed the force, Macky agreeing to his proposals for siting the New Zealand battalion. The narrow, steep-sided gorge was about five miles long. The river running through it was from 30 to 50 yards wide and fast-flowing. The railway travelled along the north side of the river, the road along the south. At the western end of the gorge the railway crossed the river and turned south towards Larisa. The Australian decided that the first necessity was to prevent enemy tanks from emerging from the defile. He arranged for a new crater to be blown in the road and for the New Zealand battalion to be disposed east of Tempe at the exit from the defile to cover it. He deployed his own battalion to protect the left flank against attack by infantry across the river from Gonnos and to give depth to the defence of the defile – although, if the New Zealanders were

Dispositions, 17th April

thrust aside and the enemy tanks able to fan out on the flats the position of the 2/2nd would be precarious. Thus the 21st New Zealand was disposed with one platoon at the road-block, and the remainder of the forward company, with one anti-tank gun, astride the road a mile to the west; one company on the slopes overlooking it; and two companies with two anti-tank guns in echelon across the road at Tempe, with a flank on to the slopes above. Chilton’s companies were placed along and astride the western exit, at intervals of about 1,000 yards, covering road, railway and river flats. The right company, with one anti-tank gun, was placed astride the road, and on the river flats where the stream bends deeply to the west; another company astride the road and railway forward of the village of Evangelismos, and a third round the southern edge of this village. A platoon from one of these companies was placed on a 1,005-metre hill above Ambelakia, the summit of the ridge overlooking the Pinios. At the suggestion of Brigadier Allen, who arrived at 1 p.m., Chilton extended his flank by placing his fourth rifle company on the high ground overlooking the river a mile west of the road.20 The gap of some 3,000 yards between this company and the next was covered by the carriers assisted later by a platoon of the 2/3rd.

The 2/2nd’s tools arrived during the morning and weapon pits were dug. In some places were low stone walls which could be incorporated into the hastily-prepared defences. A treasured hoard of Italian signal wire captured in Libya made it possible to link the dispersed companies. There was no barbed wire nor any anti-tank mines, though mines would have transformed the situation. In the afternoon sappers of the 2/1st Field Company placed some naval depth charges in the culverts on the pass, to be blown after the last troops had gone.

The 2/3rd – Allen’s third battalion – had reached the main road south of the Servia Pass at midnight on the 16th–17th, marched for two hours to reach their vehicles, and driven through Larisa to the Pinios area. When the battalion reached its destination one company was employed patrolling the roads to Sikourion and Ayia along which the enemy might make a flanking move against Larisa from north-east and east. The three remaining rifle companies were below strength because, on the way through Larisa, the drivers of several trucks mistakenly followed the main stream of traffic towards Lamia and lost touch with the battalion.

Allen, anxious about the left flank, ordered Lieut-Colonel Lamb21 of the 2/3rd to extend it still farther by placing one company (Captain Murchison) on high ground north of Makrikhori looking across the river towards similar high ground at Gonnos and left of and higher than the company which Allen had already ordered Chilton to place on the heights west of the road. The remaining two companies of the 2/3rd were in reserve astride the road some four miles south of the 2/2nd Battalion’s

position. Because it had been forced to jettison much of its equipment at the Veria Pass before marching out across the hills, the 2/3rd had few tools, no barbed wire, no anti-tank mines, and so little signal wire that Lamb had to keep in touch with his companies by runner. The men of both battalions were extremely weary; beginning on the night of the 12th they had spent every night but two in long marches and on those two they had been sleeping with only blanket and greatcoat to protect them against intense cold.

Before the companies settled in their new positions, the leading German patrols appeared. In the afternoon of the 17th small bodies of men with pack animals were seen on the ridge above Gonnos and Very lights were fired from these heights when German aircraft flew overhead. The New Zealanders reported that they were being fired on from high ground to the east. During the evening a line of men with mules was seen entering Gonnos. After dark Captain Hendry, commanding the left company of the 2/2nd, sent a platoon under Lieutenant Colquhoun22 across the river in a punt to explore Gonnos and eastwards to the river at Tempe. This patrol reported that there were Germans in Gonnos, and small bodies of men with pack animals were moving west towards Elia. At 11 p.m. a party of Germans attacked three of Colquhoun’s men left guarding the ferry and in the affray, and before the Germans made off, a German was killed and an Australian wounded.

Meanwhile, on the Australian right, Lieutenant Arnold23 and Sergeant Tanner24 in the afternoon had led a platoon of the 2/2nd along the earth road through the gorge. They passed through the New Zealand posts and continued, believing the German advance-guard still to be far away. As they drew level with a railway tunnel (on the other side of the river just ahead of the forward posts) there was a burst of fire from about 150 yards away on the other side of the stream. Two men, including Corporal Lyon,25 a section leader, fell seriously wounded and two others were hit. The leading Australians took cover and they and a New Zealand platoon returned the fire of a party of German infantry and a tank which had run along the railway as far as the tunnel (which had been blocked). The duel lasted for two hours, until dusk, when Arnold and Tanner led their men out. Men of the 21st New Zealand later brought in two wounded Australians.

It will be recalled that Blamey’s orders required the New Zealand Division to withdraw along the Larisa–Volos road, leaving the section of the main road between Larisa and Lamia to Mackay. The road to

Volos, however, was little better than an earth track, classed as a third-grade road even on Greek maps. It travelled over flat country and the rain had made it very boggy. Freyberg wrote to Blamey on the 17th to inform him that he had arranged with Mackay that morning to use “his road”.26 Having made this arrangement Freyberg ordered his 5th Brigade to begin embussing in the afternoon. Two battalions were now astride the top of the pass three miles south of Ayios Dimitrios, while the third, the 23rd, rested at Kokkinoplos with one company forward covering the muddy track leading through the village. The craters blown in the road delayed the Germans so effectively that none were seen on the front until 6 p.m. when a small body of infantry appeared at Ayios Dimitrios. The withdrawal was then well under way, and the Germans were dispersed by the fire of a troop of guns which, with two companies of infantry, formed the rearguard. The trucks carrying this brigade followed the crowded main road – the Australian division’s road – only to Pharsala and thence joined the eastern road at Almiros.

Similarly in the Servia Pass there was no infantry fighting during the 17th, though the artillery fired intermittently during the day. The New Zealand guns were withdrawn late in the afternoon; the infantry were not to begin embussing before 8 p.m. The rearguard under Lieut-Colonel Kippenberger27 of the 20th, who was to control the demolitions, was to be out of the pass by 3 a.m. on the 18th. The 19th Battalion was out before midnight, and on the road moving south, its vehicles well-spaced and travelling at good speed. The 18th had a difficult and arduous withdrawal and at 3 a.m. two of its companies had not arrived at the point where Kippenberger was waiting to order the first demolition. One company arrived at nearly 4 o’clock, the other soon afterwards, and Kippenberger ordered Captain Kelsall,28 the engineer officer with him, to demolish the road Immediately after the explosion there were cries from a few New Zealanders still on the other side. They and still later stragglers were awaited. It was 6 a.m. before Kippenberger ordered the final demolition. Except for this rearguard (whose later experiences are described below) the hazardous withdrawal from the Servia Pass was complete. The road was now covered by Brigadier Barrowclough’s29 augmented 6th Brigade Group back at Elasson.

Next to the left – but 35 miles away as the crow flies and 80 miles by road – lay Savige Force round Kalabaka. Between the late afternoon of the 16th and early afternoon of the 17th he had received four visits from liaison officers. The first discussed administrative arrangements, the

second (mentioned above) conveyed the order from Anzac Corps that Savige Force was to hold its positions until midnight on the 18th, when its withdrawal would be covered by the 1st Armoured Brigade. The third arrived at 12.30 p.m. on the 17th with the written Corps instruction, which provided that Savige should withdraw his main bodies to Zarkos during the night 17th–18th but leave a rearguard at Kalabaka during the 18th. An hour and a quarter later a liaison officer (Captain Grieve) arrived from the 6th Division with instructions to withdraw that night covered by the 1st Armoured Brigade. Grieve also brought the disturbing information that the road between Trikkala and Larisa was jammed with vehicles of the armoured brigade and vehicles, mules and men of the Greek Army, and that the bridge over the Pinios east of Zarkos had been demolished and a by-pass road, through Tirnavos, was very boggy.

The mishap to this bridge occurred when some engineers exploded a test charge. They were doubtful whether the commercial gelignite (or dynamite) which was the only explosive they had, would be satisfactory for cutting the steel trusses. To test it they exploded a small charge on a bridge member considered to be redundant, but the impact unsettled one whole truss, of some 90-feet span, and dropped one end of it into the river. Soon afterwards Lieutenants Gilmour and Nolan30 of the 6th Division’s engineers found that Larisa could be reached by two alternative routes: the first a short detour over another bridge a few miles north of the bridge which had been accidentally destroyed, and the second a much longer detour by a side road to Tirnavos and thence south to Larisa.

The problem which faced Savige on the afternoon of the 17th was a ticklish one. The road behind him was packed with vehicles, a bridge on the only reasonably good road back had been broken, and he still needed time to complete demolitions aimed at delaying a German advance from Grevena. The armoured brigade had departed and could not cover his withdrawal. The task of covering the western flank of the whole force until next day appeared to him still to be important. He decided that the right course was to remain where he was until the road was clear behind him, even though that entailed disregarding the latest order. He sought the views of his unit commanders and they agreed with him. Thereupon he gave Grieve a written statement for General Mackay setting out the reasons for his decision and saying that he would thin out on the 18th, if he could, and that he anticipated being able to remain where he was until the night of the 18th–19th. That evening a plan of withdrawal was worked out.31

At 1.30 a.m. on the 18th Grieve returned to Kalabaka with orders from Mackay that Savige should begin withdrawal during the night, reconnoitre the Zarkos position, concentrate round Syn Tomai (just beyond the demolished bridge), inform the division of his expected disposition at 5 p.m. on the 18th, and keep the 1st Armoured Brigade informed of his withdrawal. It was evident that, when these orders were given, Mackay’s staff still did not know that the armoured brigade had already withdrawn – the head of its column was then at Pharsala. Savige informed Grieve that his withdrawal would begin immediately – he had already sent out his British medium artillery and his New Zealand battery less one troop – and that he expected to be in the Larisa area not later than 5 p.m., possibly earlier if the state of the roads allowed.

During the 17th Brigadier Lee’s rearguard force at Domokos was assembled. From the north arrived the 2/4th and 2/8th Battalions, the 2/8th now 533 strong but short of weapons. The men of the newly-arrived 2/1st Field Regiment, who had been carried forward by train to Larisa, though their guns were halted at Domokos, arrived late that night. The 2/6th Battalion had arrived at Domokos by train on the 16th; the 2/7th, in the train its own men had made up and driven, arrived from Larisa whither they had been carried on, on the morning of the 17th. By nightfall on the 17th the 2/6th Battalion (plus a company of the 2/5th which had travelled from Athens with it) was in position on the right of the road on the foothills north of Domokos, the 2/7th on the left. The depleted 2/4th and 2/8th were in reserve.32

Thus by midnight on the 17th four of the seven brigades in the British force, hidden from enemy aircraft by the providential rain and mist, had passed safely through the Larisa bottleneck and were in either the Domokos or the Thermopylae positions or strung out along the road to Lamia. One of the two critical days was over, but the more hazardous task still lay ahead: to extricate the three remaining brigades (two of which were certain to be hard pressed throughout the day) along three roads converging at Larisa, and thence along a single crowded road across the plain of Thessaly, over one pass at Pharsala, over another at Domokos, and to the escarpment overlooking Lamia.

By 18th April there were signs that organised Greek resistance would not last much longer. Greece was a police state, as was Germany, and the political ideals of some of the Greek political and military leaders were closer to those of Germany than of Britain, and, in the eyes of these men, Germany carried immense prestige. It would not be difficult for the Germans to find a distinguished quisling if she needed one.

The Macedonian armies of Tsolakoglou had virtually disappeared. The retreating Epirus Army was under constant air attack and a great part

of the force had to withdraw across a single bridge which had now been twice destroyed and twice repaired. Its supply difficulties, in Papagos’ words, “were practically insuperable”.

On the 16th, after Wilson’s conference with Papagos at Lamia that day, Wavell had sent a telegram to Mr Churchill informing him what had been said, including Papagos’ proposal that the British force should leave Greece. Churchill replied on the 17th:

We cannot remain in Greece against wish of Greek Commander-in-Chief, and thus expose country to devastation. Wilson or Palairet33 should obtain endorsement by Greek Government of Papagos’ request. Consequent upon this assent, evacuation should proceed, without however prejudicing any withdrawal to Thermopylae position in cooperation with the Greek Army. You will naturally try to save as much material as possible.34

That day General Wilson hastened to Athens where he attended a conference with the King, General Papagos, the British Minister (Sir Michael Palairet), Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac and Rear-Admiral Turle.

The discussion which ensued (wrote Wilson later) revolved round the following: whether it was possible to carry on the war; whether it would be advisable for the British-Imperial Forces to hold on or evacuate, and the possible effect of the latter on the civil population; the danger of disintegration of the Greek Army in Albania; the prospect of the British sending more reinforcements, army and air; the collapse of Yugoslavia, who the day previously had passed under German domination, all organised resistance having ceased after eleven days of war resulting in the possibility of further German forces being directed against Greece.

The military situation was gloomy enough, but I was shocked at what came to light concerning the political position that the Greek Government had drifted into. The bad feeling in Athens had alarmed the Government, who were now thinking of leaving that city for the Peloponnesus but feared, if it did so, resistance would cease and that the troops would realise the critical situation; already at Yannina there had been an indiscretion and men had been sent on leave under the impression that the war was over; the propaganda of the Greek Government was having no effect in countering that of the Germans with the result that defeatism was now getting widespread. I informed the conference that I would bring all that had been discussed to the notice of Wavell, who was arriving in Athens next day.35

That evening the Prime Minister, M. Koryzis, “after telling the King that he felt he had failed him in the task entrusted to him” committed suicide.36

In London an evacuation was now considered inevitable and imminent. On the 18th Churchill issued a directive to the Chiefs of Staff and Commanders-in-Chief instructing them that they “must divide between protecting evacuation and sustaining battle in Libya. But if these clash, which may be avoidable, emphasis must be given to victory in Libya.”

Crete will at first only be a receptacle of whatever can get there from Greece (he added). Its fuller defence must be organised later. In the meanwhile all forces there must protect themselves from air bombing by dispersion and use their bayonets against parachutists or airborne intruders if any.37

Although an eventual embarkation was now a foregone conclusion, Wavell, on this day, instructed Wilson not to hurry it. In a message to him he said:

If you can establish yourself securely on Thermopylae line see no reason to hurry evacuation. You should engage enemy and force him to fight. Unless political situation makes early withdrawal imperative you should prepare to hold Thermopylae line for some time. This will give more time for defence of Crete and defence of Egypt to be strengthened as well as arrangements for evacuation to be made without too much haste.

None of this was known to the Anzac divisions in the field, now approaching what seemed likely to be the critical hours of the campaign. The 18th April was clear and fine. In the Pinios Gorge – still the danger spot – about 7 a.m. German troops were seen moving down the slopes from Gonnos south-east towards the river. They increased in numbers until it appeared that a battalion was deployed there, and another battalion (or so it seemed) was moving west from Gonnos along the tracks leading towards the main road between Elasson and Tirnavos. Captain Hendry, commanding the left company of the 2/ 2nd Battalion, reported that the enemy battalion moving west presented a good artillery target. No artillery observer had yet been established on this hill, but until one arrived Hendry, by telephone, directed fire on the enemy across the river. It was still early in the morning when, from the high ground, a trickle of men were seen moving south along a track from Parapotamos. The watchers thought at first that these dun-clad figures were Greek refugees – they had seen many such during their long marches north of Olympus. However, about 9 o’clock Hendry sent Lieutenant Watson’s38 platoon down the hill to see what was happening in the village and to destroy a boat that had been used to ferry small parties of men across. As the patrol approached Parapotamos it came under sharp fire, and a long fight began in which a corporal, Baker,39 was mortally wounded and two others wounded.

Meanwhile, in response to Hendry’s report that enemy troops were moving round his left and out of range, Chilton sent out his carrier platoon to intercept them. Lieutenant Love40 led six of his carriers forward towards the river, and when they reached the exposed side of the hill concealed them beside the track and sent a section forward on foot to a point whence they could see the boat and, within light machine-gun

range, German mortars firing. Love then brought the carriers forward but they immediately came under hot fire from the mortars which killed one man, mortally wounded Love and wounded four others of his platoon, and also Watson who had withdrawn his men in this direction. Sergeant Stovin41 and Private MacQueen42 silenced a German mortar with Bren gun fire while Corporal Lacey,43 deliberately exposing himself to create a diversion, organised the rescue of the wounded and withdrew the carriers to sheltered ground. Stovin then established his platoon, dismounted, on this flank.

Hendry was now, about 11 a.m., for the first time in touch with Murchison’s company of the 2/3rd on his left rear. Because some of its trucks had missed the road at Larisa this company had a strength of one officer and about fifty men but increased bit by bit during the day. It had no tools with which to dig in, but took up its position as best it could.

Meanwhile, early in the morning while it was still misty, about forty Germans appeared on the bank of the river opposite Buckley’s company – the right flank of the 2/2nd. The Germans were bunched in a way that puzzled the Australians, who fired on them and “wiped them out”.

Throughout the morning German activity on the front of the 21st Battalion increased and by midday a heavy attack was in progress. The Germans cleared away the road-block and their tanks came through. The first tank knocked out the nearest 2-pounder gun and the second tank advanced past it. These and other tanks farther back and German infantry across the narrow gorge fired on the exposed positions of the 21st on the bare forward slopes of Mount Ossa.

The foremost platoons were pushed back and the anti-tank crews out in front of them waited and watched. Three tanks moved slowly along the road below. When the nearest was almost under the noses of the nearest gunners they fired. Two tanks were knocked out and the third hit several times; the gun fired 28 rounds all told. But by now enemy infantry had crossed the river behind the gunners and called on them to surrender. One gun crew escaped and squads of infantry with machine pistols crept close to another gun while mortars across the river concentrated on it; the crew was driven off or captured. The tanks were then engaged by indirect fire from the field guns and they stopped for some hours. With tanks a stone’s throw below, scorching the hillsides with machine-gun fire, and large bodies of infantry just across the gorge, the remaining 21st Battalion positions on the bare slopes south of the river became less and less tenable. Platoon by platoon the unit fell back. Over the crest of the main ridge (on which stands the village of Ambelakia) were innumerable gullies in which it was impossible to collect the scattered fragments of the battalion. Elements continued to hold out higher up the ridge but the battalion was losing its cohesion.44

At 11 o’clock small parties of New Zealanders had begun to withdraw through Buckley’s position declaring that German tanks were advancing along the road behind them and, at 11.30, the crew of the anti-tank gun in his area was missing. During the morning Chilton had several telephone conversations with Macky, who told him that Tempe village was under heavy mortar fire and his men were engaging enemy troops across the river. Then, about midday, the telephone to Macky became silent. Soon afterwards more small parties of New Zealanders began to move through the Australian positions, most leaderless, though one complete platoon under Lieutenant Southworth45 reported to Chilton and was put into position near Evangelismos The greater part of the New Zealand battalion had moved south and south-east up the slopes of Ossa. Just before Macky’s telephone was cut off, however, his Intelligence officer had spoken to Allen’s headquarters saying that German tanks were in Tempe and the battalion was withdrawing to the hills

Soon after losing communication with the 21st, Chilton was telephoned by Buckley and told that New Zealand troops retiring along the road were saying that the German tanks had reached Tempe. Chilton told Buckley to warn the anti-tank gun in his locality to cover the exit from the village, but Buckley reported that the crew of this gun had gone, taking the breech-block with them.

After the withdrawal of these New Zealanders the Australian battalion was not heavily pressed for more than two hours, though the whole area was under intermittent mortar and machine-gun fire. As we have seen the German tanks were halted round Tempe, under artillery fire. So far the Australians had lost about forty killed and wounded. Then at 3 p.m. a concerted attack began. First thirty-five aircraft appeared and for half an hour circled Makrikhori railway station near which Allen’s headquarters were established, dropping bombs, one of which smashed the little railway station.

The foremost platoon of the 2/2nd was Lieutenant Lovett’s, about 400 yards forward of Buckley’s headquarters. A tank drove through its position and, with the tank between them and company headquarters, most of the platoon fell back across the road to the slopes on the south side, Lovett himself being wounded and later made a prisoner. At this stage an Australian anti-tank gun in Buckley’s area was disabled and the crew put their hands up, but were shot at by the advancing tanks of which there were now three on the road.

Meanwhile a heavy infantry attack had been made on Captain Caldwell’s company next to the left.46 What appeared to be a German battalion began to wade the river on his left, supported by machine-gun fire from the slopes above. As they moved across the river and on to the flats they were met by intense and accurate fire from the Bren gunners not only of this company but of the next to the left and from battalion head-

quarters, and were showered with bombs by Sergeant Coyle’s47 two 3-inch mortars. In an hour and a half, firing until the barrels were “almost red hot”, the youthful Coyle, Corporal Evans48 and their team lobbed 350 bombs with deadly effect among the advancing Germans as they reached the rushes on the south bank of the river, and on the rafts on which they were crossing. The infantrymen saw broken rafts and many dead bodies floating down the stream. This fire and the fire of the Bren guns broke the attack across the river, but the tanks continued to press forward along the road.49

At 5 p.m. the telephone line to both Buckley’s and Caldwell’s companies was broken. Private Thom50 rode forward under fire on a motorcycle, found the break and brought back a message from Caldwell; whereupon Lance-Corporal Steadman51 and two others laid a new line to Caldwell’s company under brisk fire, and arrived at their destination only in time to find the company withdrawing and their retreat cut off.

On the left Hendry had reported to Chilton by telephone at 4 p.m. that the enemy was steadily moving round his left flank and digging in south of Parapotamos. Chilton ordered him to withdraw his platoon from the river bank and with Sergeant Stovin’s carriers make a counter-attack against the Germans on the flats to the west. After this the line to Hendry’s company was broken. Hendry was organising the counter-attack when Murchison arrived with an order, timed 3.45 p.m. and signed by Captain Walker,52 adjutant of the 2/3rd, stating that “B” Company of the 2/3rd was “now withdrawing” and Murchison would coordinate his withdrawal with that of the company of the 2/2nd nearest to him. It was then 4.30. Hendry, a schoolmaster by profession, was somewhat puzzled by this order, and advised the younger man, Murchison, to make sure that he did not lose it because, he said, sometimes questions were asked afterwards about withdrawals. Thus at 4.45 the two companies began to withdraw platoon by platoon, the last platoon of Hendry’s company being covered by Stovin’s carriers which took the last infantrymen out. Mortar bombs were bursting on the hill but the German infantry were not pressing hard. The Australians marched to Makrikhori where they boarded their trucks and drove south to brigade headquarters and the reserve companies of the 2/3rd. Chilton knew nothing of this withdrawal or the order which

produced it, but when, between 4.30 and 5, firing ceased on the Makrikhori slopes he concluded that the companies there had been overrun.53

Buckley’s company, on the slopes above the road, was now firing down from 100 yards’ range at a group of German tanks. Each tank was dragging a trailer carrying seven or eight infantrymen while other infantry followed, the men on the tanks waving them on. As they neared Caldwell’s company one tank was hit and stopped by a shell from one of the two forward 25-pounders, then three more were hit; none of the crews emerged and the tanks were assumed to have been destroyed. Other tanks followed up. For about forty minutes these “milled round firing madly and moved on the flats north of the road”. Ten tanks, closely followed by infantry, broke into Caldwell’s position. It was then 6.5 p.m.

Caldwell withdrew his headquarters, first 150 and then 400 yards from the road, whence, like Buckley’s company on his right, his men watched about eighteen tanks move forward; as they emerged from the defile the tanks deployed and moved south astride the road. Infantry and, at a short distance, another six or eight tanks, followed.

Supporting infantry were not energetic in mopping up (wrote Caldwell later), and no patrols or flank guards moved in the hills to the east of the road which entered Evangelismos from the north-east.

Shortly after 4 p.m. General Freyberg had spoken to Chilton on the telephone seeking news of his 21st Battalion, and asking Chilton whether he could get a message to them. Chilton said that would be impossible. Freyberg asked whether Chilton thought that he (Freyberg) could reach Chilton’s headquarters. Chilton replied that the way was still open but it seemed likely that tanks would soon block it. Chilton described the situation; Freyberg asked him to do what he could to collect any stragglers. “You’ve a fine man up there,” said Freyberg to Allen, “he’s as cool as a cucumber.” He said good-bye to Allen and wished him luck. Allen assured him that all would be well. Soon afterward’s Chilton’s line to Allen’s headquarters died. Allen and his brigade major, Hammer,54 then wrote a detailed order for the withdrawal of the force (Hammer had outlined this order to Chilton while the telephone was still in action), and at 5.30 handed it to Lieutenant Swinton, one of the liaison officers, to deliver to Chilton and Parkinson. Swinton set out in a carrier along a road congested with men and vehicles. When he reached the forward artillery positions he was informed, wrongly, that Chilton’s headquarters had been overrun by tanks; he could see men in the hills to the east. He handed Parkinson’s order to the officer commanding the guns and drove up the slope, hoping to find Chilton among the troops on the slopes, but the carrier could not climb through the gullies and he returned to brigade headquarters.

What had happened was that when the tanks fanned out in the Evangelismos area Lieutenant Moore,55 commanding eleven carriers (some from the 2/5th and 2/11th Battalions), formed the vehicles up, hull down, astride the road and railway to cover the withdrawal of the infantry. Here a point-blank duel took place between the tanks and a New Zealand 25-pounder sited about 100 yards west of Chilton’s headquarters. Two tanks were hit and set on fire, and the gun crew and a leading tank then exchanged shots until a shell from the tank destroyed the ammunition limber; thereupon the crew coolly withdrew, carrying the breech-block with them. In accordance with Parkinson’s order the other guns were hauled out, one troop covering the withdrawal of the two others as they leap-frogged back at 1,000-yard intervals. This left only one 2-pounder in a defiladed position near Chilton’s headquarters; about 6.30 this gun and its crew were withdrawn without orders from Chilton. A dense cloud of smoke was rising from the burning tanks and drifting south-west, making a smoke screen under cover of which more tanks and infantry moved on the flat west of the road. At this time runners at length arrived from both Buckley’s and Caldwell’s companies announcing that those companies had retreated up the slopes of the hill – the first news of these companies for more than an hour, the time taken by the runners to climb round the hills to the headquarters of the battalion.

The German tanks, their crews made cautious by their losses on the road, and evidently not knowing that no guns remained, took up hull-down positions and fired briskly. Their fire forced out the carrier platoons, Lieutenant Gibbins’ platoon of the 2/3rd, and Lieutenant Southworth’s of the 21st New Zealand, which were in the neighbourhood of battalion headquarters.56

The signal truck had been under fire and Chilton ordered Lieutenant Dunlop,57 his signals officer, to withdraw to cover. While he was doing so the truck was disabled by a tank shell. Corporal Hiddins,58 however, returned, jumped on the truck and began to drive it to cover. He was about to start the vehicle when a tank appeared in the lane ahead, whereupon he backed the truck and turned into a ploughed field and was half way across when it was hit by a shell and burst into flames. The brave Hiddins was not injured and escaped to shelter.

Tanks and infantry were now moving from the north, north-west and south-west on to the area south of Evangelismos where battalion headquarters and Captain King’s59 company were in position. At 6.45 Chilton decided that King’s company would soon be surrounded and could not delay the advance of the tanks or infantry along the flat country west

of the road. He ordered it to withdraw. It moved out in good order and Chilton followed.

A section commanded by Corporal Kentwell60 covered the withdrawal of Chilton’s little headquarters, firing with anti-tank rifle and Bren until tanks were 50 yards away and then dribbling back to take up another position farther up the hill. Thenceforward until dark the parties of 2/2nd Battalion men climbed up into the hills taking what cover the land offered from the brisk fire of German tanks and infantry below.

At 5.45 Hendry’s and Murchison’s companies began to arrive at Allen’s headquarters, and the New Zealand guns which had been in support of the 2/2nd were moving through the area. It was evident that the 21st and 2/2nd (except one company) were cut off. Allen’s orders from Freyberg were to deny the enemy a line through the Tempe–Sikourion road junction until 3 a.m. He told Lieut-Colonel Lamb of the 2/3rd to stop the gunners and place them in a covering position where road and railway crossed.

Allen moved his own headquarters back to this position. He was confident that he could hold the enemy on this line until after dark, when the task would become much simpler. There were several places between that point and Larisa where successive rearguard positions could be held in the darkness with few troops. In the new position one company of the 2/3rd was on a hill on the right of the road, Murchison’s company of the 2/3rd and Hendry’s of the 2/2nd on low ground on the left with carriers extending the flank and more carriers and a third company of the 2/3rd, only some thirty strong, in reserve.

Allen now had a considerable collection of carriers. There were the carrier platoons of three Australian battalions, the 2/2nd, 2/5th and 2/11th (each of the 2/5th and 2/11th about half strength), and some carriers of the 21st New Zealand; and, in the course of the afternoon, two armoured car troops and a carrier troop of the New Zealand divisional cavalry arrived. His infantry strength, however, had been reduced to one company of the 2/2nd and two of the 2/3rd, both reduced in numbers by the fact that some of the trucks that had lost their way on the night of the 16th–17th had not yet rejoined.61 The whole area had been bombed and strafed intermittently during the day by aircraft attracted by the collection of vehicles and men, and some trucks hit earlier in the afternoon were still burning. About 7.30 p.m. five German tanks appeared, moving astride the road, and were met by a hail of harmless fire from rifles and Brens. Two of the New Zealand 25-pounders were moved up into the line and swung into action in the open, firing at the tanks at close range. Later one of the infantrymen described the scene:

The officer stood out in the open directing the fire, the crews crouched behind the shields and fed and fired the guns while everything the enemy had was being pelted at them. ... They looked like a drawing by someone who had never been to a war, but the whole thing was unreal. They got two tanks, lost one gun and pulled the other gun and their wounded out, having done what they could. There was nothing to stop the tanks then, and they formed up and came on.

A squadron of aircraft then appeared from the direction of Larisa and made strafing runs across the area at the infantry and carriers who fired back with rifles, Brens and even anti-tank rifles. On the left the tanks pressed forward in the dusk firing until they were in the midst of Hendry’s men.

At one stage (wrote Hendry) a group of fifteen to twenty men were round a tank firing rifles and L.M.G.s to no apparent effect. This tank crushed two men,62 Privates Cameron63 and Dunn.64 The feeling of helplessness against the tanks overcame the troops and they began to move back in small parties to the trucks.

This movement rapidly spread along the line. “By this time,” wrote a sergeant commanding a platoon in Murchison’s company, “Arthur Carson,65 a D.C.M. from the last war, was beside our platoon with his pioneers and I asked him if any orders had come through. ‘Some are going back,’ said Arthur, ‘but we have no orders to withdraw.’ Arthur spoke in his usual quiet manner, as though he was back in camp and a fatigue party hadn’t arrived to dig a drain for him. I sent a man back to find out what was doing, and it appeared that we were left like a shag on a rock and the rest were on the trucks withdrawing.”

Murchison signalled his platoons to withdraw to the road and board the trucks. Lamb had already ordered Major McGregor’s company on the right of the road to withdraw. There was then little daylight left and when Lamb halted the vehicles and began forming the infantrymen and carriers across the road 1,000 yards farther south it was dark. The new line was in the shape of a tilted “L” with its shaft across the road and its base beside the railway line on the left, and the men lying close enough together in the darkness to be able to touch one another.

This time we really did think it was the end (wrote the platoon commander quoted earlier). I started to get the platoon together more for sentiment’s sake than for usefulness, for the colonel was telling them to go down wherever they were, but Arthur, who turned up again beside me, said: “We’re not platoons here. We are the AIF”

In a few minutes the leading tank appeared. A man who was standing waist high in the turret of one of them peering out was riddled with

bullets and slumped forward. Lamb shouted to the men to make every shot tell and that the tanks could not fight in the dark. The tank stopped and fired shells and tracer bullets at random and fire appeared to be coming from other tanks behind it; an ineffective hail of rifle and machine-gun fire answered this. The tank withdrew. Allen then ordered Lamb to take the force back to a point where the road crossed a swampy area north of Larisa. Allen and his staff remained to see the position cleared; New Zealand armoured cars covered the withdrawal.

It was a fantastic battle (wrote Allen afterwards). Everybody was on top (no time to dig in), and all in the front line, including artillery, Bren carriers, infantry and various unit headquarters, with unit transport only a few hundred yards in rear. Some confusion could be expected with every weapon firing and aircraft strafing from above. If you saw it at the cinema you would say the author had never seen a battle. We had to hold this position until after dark and thanks to the morale of the force it was done. As expected the pressure eased after dark – but I have often wondered why the enemy did not follow up his success if only with infantry patrols.

The Larisa road, which was narrow, with ditches each side, was now crowded with moving vehicles. When, about 10 p.m., the leading lorry reached the level crossing two miles from Larisa it was halted at a railway truck that had been pushed across the road. There was a burst of fire which killed or wounded nearly every man in the vehicle, including Captain Flashman,66 medical officer of the 2/3rd. Sergeant-Major Hoddinott, with some others, jumped from the lorry and, lying by the road, he saw a party of (it seemed) about fifty Germans firing, throwing grenades and calling for surrender. Four New Zealand carriers appeared. Their commander decided that they should force their way through the Germans, the trucks following them. Lieutenant Johnson,67 who had commanded the Australian anti-tank guns at Tempe, and who was with the carriers, wrote afterwards:

Upon proceeding 100 yards the leading carrier ran into what I presume was a land mine, slewed across the road and blocked any further movement forward. The efforts of approximately six men failed to roll the carrier off the road, it still being under continual machine-gun fire and sniping, and the troops were told to take cover off the road. [I and Gunner Aldridge68) contacted a second lieutenant of the N.Z.E.F. who had with him several of his own men. He expressed his determination to attack the machine-gun nest on the left of the road and wanted personnel to accompany him. Bombs were obtained from one of the carriers and we attempted to encircle the nest. During this time fire from the enemy was still kept up. As far as I can ascertain it took us nearly an hour to overrun this position. It was situated between the rails and sangared in with stones. Four men were in the post .... All four men were killed. After destroying the gun we withdrew back on to the flat ground. During the operation several New Zealanders received wounds. Owing to the casualties it was decided not to attack the other machine-gun post but to make our way round Larisa.

Johnson and Aldridge went back among the vehicles to find others of their men, but, failing to do so, they and some of those round about split into small parties and skirting the remaining German post, made towards Larisa.69

Meanwhile the column behind had halted well short of the ambush, where tracer fire and flares could be seen, and a rumour had run back along the line that the Germans were in Larisa. Lamb decided to divert the column to the left to the Volos road (as he thought) and, one after another, the crowded trucks and carriers turned left off the main road on to the boggy tracks or into the fields and set off south-eastwards. In fact the first road they would meet did not lead to Volos but was a dead-end road to a village on the coast south of Mount Ossa.

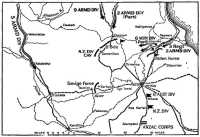

Thus, at dawn, most of what remained of Allen’s force was dispersed in small groups of vehicles ploughing along boggy farm tracks east of Larisa; part of it was finding its way through Volos to Lamia. The 21st New Zealand Battalion had been pushed into the hills above Tempe; most of the 2/2nd into the hills above Evangelismos.70 The force had carried out its orders to deny the Tempe–Sikourion road junction until 3 a.m., but a party of German troops – its strength unknown to Allen or Lamb – had moved round its left flank and cut the road to Larisa.

It will be recalled that, on this critical day, three rearguard forces were to withdraw through the Larisa bottleneck – Allen’s from the Pinios, Barrowclough’s from Elasson and Savige’s from Kalabaka. Each held a position astride one of the three main roads leading south, but between those roads were a number of tracks through the hills For instance, from Gonnos, on the heights which Allen’s force overlooked, fanned three tracks, one to Elasson, one to the Tirnavos area, and a third to a point on the main road between the two, and all day Allen’s men had watched German troops moving west and south-west along them towards the New Zealand rear. Early in the afternoon Allen’s left company had been briskly engaged with Germans established on the southernmost of these tracks where they were well situated to move either to Tirnavos or Larisa without interference.

At dawn on the 18th the New Zealand Cavalry Regiment with two of its squadrons and two anti-tank troops under command was guarding the junction of the roads from Servia and Katerini. The rearguard for the 4th Brigade had been thinned out until it consisted only of Colonel Kippenberger, his driver and batman, some sixty sappers and three Bren carriers. As mentioned above, this rearguard had delayed several hours to collect stragglers.

The foremost cavalry squadron had one detachment with one 2-pounder portee (gun mounted on a vehicle) astride the road to Servia and another with three portees on the Katerini road. The second squadron was just south of the junction with four anti-tank guns dug in. While the men on the Katerini road were getting breakfast they were surprised to see four tanks and some motor-cycles coming down the road from Katerini. They had expected the demolitions to delay the enemy’s vehicles for some days. They went into action, knocked out two tanks and drove the motorcyclists back. The detachments then withdrew behind the rear squadron. Kippenberger’s rearguard from Servia arrived in the midst of this engagement and before they quite knew what was happening the engineers and carrier crews were being fired on at short range by German tanks. The men either took to the hills or were killed or captured. Kippenberger led one party out on foot over the hills to the south and after some hours reached the 25th Battalion.

Meanwhile the German tanks attacked again, this time along both roads, but the anti-tank gunners quickly knocked out at least four tanks, two armoured cars, and a lorry. When word arrived that all other troops were behind the defences of the 6th Brigade this rearguard withdrew.

The 6th Brigade was deployed south of Elasson where two roads lead to Larisa, one over the steep Menexes Pass to the south-east and the other south-west by an easier but longer route. The 24th Battalion guarded the eastern route, the 25th the western; the 26th was in reserve round Domenikon. The infantry was supported by the 2/3rd Field Regiment (with twenty 25-pounders), and with a troop of the 64th Medium Regiment under command; two groups (eight 25-pounders) of the 5th New Zealand Regiment in an anti-tank role behind the 25th Battalion; a battery (twelve 25-pounders) of the 5th Regiment in reserve at Domenikon; and seven 2-pounders dug in and four mobile in the 25th Battalion area. Thus there were no guns near the 24th Battalion but the steepness of the pass, demolitions and mines were thought to provide an adequate protection against tank attack in its area, and the country in front of the infantry could be brought under fire from the field guns to the east.

German tanks closely followed the withdrawal of the New Zealand cavalry, and by about 10.30 the medium guns were firing on enemy vehicles bunched in the hills north of Elasson. The field guns of the 2/3rd caught groups of enemy tanks at ranges up to 10,000 yards and hit numbers of them. This accurate fire and the difficulty of putting vehicles across the river prevented the Germans concentrating for a serious attack until late in the day. Dive-bombers passed overhead in groups of from forty to sixty at regular intervals to harass the columns farther south, but only one bomber attacked the 6th Brigade. The medium guns ran out of ammunition early in the afternoon and withdrew, but by a fortunate accident the Australian gunners were lavishly supplied with ammunition. Before the withdrawal from the Katerini Pass the 5th New Zealand Regiment had been ordered to carry one load of ammunition from the 4th’s positions at Ayios Dimitrios to the position south of Elasson. The order

Late afternoon, 18th April

was misunderstood; the drivers worked all night on wet and crowded roads and moved back all the considerable dump of ammunition that had been stored at Ayios Dimitrios in readiness for a prolonged stand in the pass. After the medium guns were withdrawn most of the firing was done by the 2/3rd. The artillery observers gave the batteries such targets as “15 cruiser tanks”, “30 tanks”, “12 vehicles”, “5 tanks”, “6 tanks”. “Exciting day,” wrote the diarist of the 2/3rd Australian, “in which 6,500 rounds were fired by the regiment. Tanks appeared in the early morning and troops formed up but the consistent shooting of the regiment stopped the enemy and the infantry made no contact.” Indeed, all day the advance of what was evidently a powerful enemy force, with a battalion or more of tanks advancing over open, rolling country, was held chiefly by demolitions and the fire of twenty-four field and medium guns.

Just before dusk, however, when the rearguard was beginning to thin out, the enemy attacked. Shells fell in the 24th Battalion’s position and a column of lorries, led by tanks, advanced up the road to the Menexes Pass. Leading tanks struck mines and soon the 2/3rd Field Regiment was pumping shells among the tanks. German infantry dismounted and advanced against the forward positions of the 24th as it was withdrawing in accordance with the plan, but the attackers succeeded only in delaying the withdrawal for a time. On the eastern flank the Australian guns were pulled out troop by troop and the infantry thinned out until only a troop of New Zealand field guns, four anti-tank guns and small parties of infantry were left. The field guns fired heavily until 11.30 p.m. when

the force moved back swiftly, blowing culverts on the way. It reached Larisa about 3 a.m. The 24th and 25th Battalions took the road to Volos; the 26th Battalion travelled from Larisa by train.71