Chapter 6: The Thermopylae Line

General Wavell arrived in Athens on the 19th April and immediately held a conference at General Wilson’s quarters. Although an effective decision to embark the British force from Greece had been made on a higher level in London, the commanders on the spot now once again deeply considered the pros and cons. The Greek Government was unstable and had suggested that the British force should depart in order to avoid further devastation of the country. It was unlikely that the Greek Army of Epirus could be extricated and some of its senior officers were urging surrender. General Wilson considered that his force could hold the Thermopylae line indefinitely once the troops were in position.1 “The arguments in favour of fighting it out, which [it] is always better to do if possible,” wrote Wilson later,2 “were: the tying up of enemy forces, army and air, which would result therefrom; the strain the evacuation would place on the Navy and Merchant Marine; the effect on the morale of the troops and the loss of equipment which would be incurred. In favour of withdrawal the arguments were: the question as to whether our forces in Greece could be reinforced as this was essential; the question of the maintenance of our forces, plus the feeding of the civil population; the weakness of our air forces with few airfields and little prospect of receiving reinforcements; the little hope of the Greek Army being able to recover its morale. The decision was made to withdraw from Greece.” The British leaders considered that it was unlikely that they would be able to take out any equipment except that which the troops carried, and that they would be lucky “to get away with 30 per cent of the force”.

This British discussion was followed by a conference at the Greek King’s palace, attended, as on the previous day, by the King himself, Sir Michael Palairet, General Papagos, General Wilson, Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac and Rear-Admiral Turle; but, on this occasion, also by General Wavell and by General Mazarakis, a leader of the Venizelist Republican party to whom the King had suddenly offered the Prime Ministership.

Wavell, who spoke first, said that the British Army would fight as long as the Greek Army fought. On the other hand it would embark if the Greek Government wished. Papagos then said that the morale of the Greek Army had been shaken. The Epirus Army had now to be supplied along a single road (through Yannina) and the vehicles available were too few to maintain that army in the field. Some of the senior officers wished to cease fighting. The King, the Government and the high command had had to order them to fight on. Greece would be devastated if the armies continued fighting for another month or two. Palairet then read a telegram from Mr Churchill to the effect that if the British force left Greece it must

be with the full consent of the Greek King and Government. Mazarakis said that “he had been called in too late to retrieve the situation and that evacuation was the best solution”.3 It was decided that the British force should be embarked and that

the Greek forces in Epirus should continue fighting as long as possible, or at any rate as long as [required for] the withdrawal of the British forces. ... The war was of course to continue in the islands with all the means and the naval forces available, since Greece was indissolubly bound up with Britain and her resolve was to fight to the end by the side of the British Empire.4

The belated effort to bring the Venizelists into the Government failed. They had been obliterated from Greek public life after 1935, when Metaxas established his dictatorship. In 1935, and later, large numbers of republican army officers had been dismissed. When the Italians invaded Greece some relatively junior officers of republican leanings were allowed to rejoin the army but none of the rank of colonel or above was recalled.5

These republican officers considered the monarchists generally to be half-hearted about the war and inefficient. They thought that, as soon as Italy attacked, a coalition government should have been formed and the compulsorily-retired republican officers recalled. Now, at the eleventh hour, the King proposed to form a coalition government. Mazarakis agreed to lead a coalition on condition that M. Maniadakis, the Minister for Internal Security, who controlled the police force, was excluded.

As this matter affected security (wrote Wilson afterwards) it was referred to my headquarters for decision as to the advisability of a change at this juncture; in view of the impending evacuation we were unable to agree to any step which would tend to loosen the control exercised by the police in Athens. (Two years were to elapse before a Venizelist entered the Greek Government.)6

It was ironical that, as a result of a British decision, the followers of the great Greek liberal who had been a devoted ally of Britain and France in the first world war should thus have been excluded from the Greek Government in this crisis.

Although, on the 18th, Mr Churchill had issued a directive about the principles that should govern the evacuation, on the 20th, evidently encouraged by news that the British force was successfully falling back to the Thermopylae line, he wrote to Mr Eden in an optimistic vein.

I am increasingly of the opinion that if the generals on the spot think they can hold on in the Thermopylae position for a fortnight or three weeks, and can keep the Greek Army fighting, or enough of it, we should certainly support them, if the Dominions will agree ... every day the German Air Force is detained in Greece enables the Libyan situation to be stabilised, and may enable us to bring in the extra tanks [to Tobruk]. If this is accomplished safely and the Tobruk position holds, we

might even feel strong enough to reinforce from Egypt. I am most reluctant to see us quit, and if the troops were British only and the matter could be decided on military grounds alone I would urge Wilson to fight if he thought it possible. Anyhow, before we commit ourselves to evacuation the case must be put squarely to the Dominions after to-morrow’s Cabinet. Of course, I do not know the conditions in which our retreating forces will reach the new key position.7

It was too late, however, for such a change of heart and change of plan. That day there was a meeting of Greek generals in Epirus. With the support of the Bishop of Yannina, General Tsolakoglou (whom we last saw driving westward from Kalabaka leaving his troops behind him) and his two fellow corps commanders, removed General Pitsikas, the leader of the Epirus Army, from his post, and opened negotiations for surrender with the commander of the “Adolf Hitler” Division, then nearing Yannina. Next day at Larisa, Tsolakoglou signed an agreement to surrender. When Papagos learned of Tsolakoglou’s preliminary negotiations he sent a signal to Pitsikas ordering him to dismiss Tsolakoglou immediately, but Pitsikas had already been deposed.8

That day the gallant little British air force struck its last blow. About 100 German dive bombers and fighters attacked the Athens area. The fifteen Hurricanes which were still serviceable went up to intercept them and reported having brought down twenty-two German aircraft for certain, and possibly eight others, for a loss of five Hurricanes.

Meanwhile, at 2 o’clock on the morning of the 21st, Wavell arrived at Blamey’s headquarters and informed him that the force was to be evacuated as soon as possible. At that stage it was considered that embarkation would not begin before 27th April; but, at a conference between Wilson, Blamey, and Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman9 (in charge of the naval arrangements ashore) on the roadside near Thebes the following night, Wilson informed Blamey that as a result of the surrender in Epirus he had decided to accelerate the program. It would be Blamey’s task to deliver the first troops to the beaches by dawn on the 24th, for embarkation on the night of the 24th–25th.

In the meantime the Anzac Corps had gone into position on the Thermopylae line. By sunrise on the 19th it had succeeded in placing some 40 to 50 miles of cratered roads and demolished bridges between itself and the German advance-guard. The Germans were not then in Larisa, where police of the 7th Australian Division’s provost company were still coolly directing the few vehicles straggling behind the main columns. The 6th New Zealand Brigade group was in Volos; the divisional cavalry and a company of the 25th Battalion occupied a rearguard position across the

roads leading into that town. Stragglers of the 21st Battalion and the 2/2nd

from Tempe arrived at Volos during the morning; other parties from those

battalions and the 2/3rd were dispersed in the hills to the north and west.

At dawn the retreating Anzac column on the main road from Larisa to Lamia was still more than 10 miles in length, the vehicles closely spaced and an easy target for air attack. The day again was fine but, luckily for the long convoy, German aircraft did not appear in force until some hours after daylight, and by then the vehicles were moving steadily south. There were heavy attacks by groups of up to twenty-seven aircraft from 7 a.m. to 8.30, then a lull, a second attack by twenty-one at midday, and another lull until about 2 o’clock. In the early afternoon the Domokos rearguard and the road south of it were attacked continuously for two hours and a half. The tail of Savige Force was then some miles past Domokos.10

The column was making painfully slow progress and most of the troops spent the whole day packed in their vehicles under fire from an enemy against whom they could not hit back. A typical experience was that of the 2/1st Battalion. At dawn it was 10 miles north of Lamia in the middle of a congested column. It did not pass through Lamia until 10 a.m.; then the column was halted under air attack on the straight road, the trucks almost head to tail and, in places, two abreast. At length the column began to move again, but it was 5 o’clock before this battalion reached its positions in the Brallos Pass.

Many vehicles were hit but few disabled. One officer who was towards the rear of the column remembers having seen only six abandoned vehicles between Larisa and Lamia. It seems certain that more vehicles were lost as a result of being bogged, breaking down, or running over the edges of the narrow roads than as a result of direct damage by air attack. In men, to take two instances, the 2/5th Battalion lost thirteen killed and twenty-four wounded during the day, and the 2/11th Battalion four killed and eleven wounded; these appear to have been the heaviest casualties inflicted on Australian battalions by air attack in any day in this campaign.11 Attacks with light bombs and machine-guns against troops dispersed in defensive positions were ineffective, and everywhere the softness of the ground limited the effect of the bombs. For example, the 2/6th, deployed beside the road at Domokos, reported that its area had been attacked by twenty to thirty aircraft at 7.30 and again at 12.15, and, later in the afternoon, by relays of aircraft for two hours and a half; yet its only losses were one officer (Lieutenant Williams12) killed, and two men wounded. Mackay’s driver was wounded here. Farther north the driver of Lieut-Colonel Louch of the 2/11th was killed and their car run off the road, Louch being badly shaken. Brigadier Savige’s driver had his foot broken by a great clod of earth thrown up by a bomb. Dive bombers made an effective attack on Brigadier Steele’s engineer headquarters group at the foot of Brallos Pass.

His medical officer, Captain Weir,13 and a sapper were killed, and his adjutant, Captain Reddy, and two others wounded.

It was impossible for commanders to control the slowly-moving column in which their cars were merely links in the long chain. By the roadside, during a halt, Steele and Savige met and agreed with each other that it was inadvisable for staff cars to weave their way forward when the column was halted, to discover what was causing the delay, because of the risk that the troops might interpret this as signifying that officers in staff cars were “beating it”. These leaders, like Mackay, Freyberg and other senior officers, made themselves conspicuous at the roadside, or went calmly about their duties at their headquarters, setting an example of cool behaviour under fire.14

Mackay spent the 19th, from 7.30 until about 4 p.m., at the Domokos rearguard position, so that he could see for himself the problem facing Brigadier Lee there. Lee’s force had originally included four battalions-2/4th, 2/8th, 2/6th and 2/7th – a company of the 2/5th, and artillery and engineers. On the 18th Lee had decided that it was unlikely that he would be hard pressed by the enemy before the remainder of the New Zealand and Australian divisions had passed through Lamia. He therefore ordered the 19th Brigade (2/4th and 2/8th Battalions) to withdraw to the Thermopylae position, but retained one company of the 2/4th.15 Mackay approved this decision when he arrived at Lee’s headquarters on the morning of the 19th.

That morning it was discovered that a train-load of petrol, ammunition, gun-cotton and ammonal was standing at a railway siding two miles north of Domokos. Lieut-Colonel Walker of the 2/7th decided that so valuable a cargo should be driven back to Athens, and the ubiquitous Corporal Taylor, the same who had made up a train at Larisa and carried the battalion back to Domokos, went forward early in the afternoon with Corporal Edwards16 and six other volunteers, all Victorian railwaymen, to drive the train to safety. A squadron of German aircraft saw the steam rising and circled overhead bombing and machine-gunning the station and train. Taylor was in the engine alone, with his team lying under cover awaiting his signal to jump aboard, when the trucks exploded with a shattering roar and a huge mushroom of smoke rose into the air. The blast was so powerful that men in the infantry positions two miles away

felt the force of it. It thrust the engine violently along the rails, and thus its power was cushioned. Taylor survived, and, to the astonishment of those in the pass who had given the railwaymen up for dead, he arrived back at the battalion, leading his men, his hair singed but otherwise unharmed.17

Late in the afternoon Mackay decided that Lee’s force would soon have done its job – to ensure that the New Zealand and Australian brigades withdrew through Lamia without interference by German troops. He therefore ordered Lee to pull out the main part of his force at dusk, and himself moved south to his new headquarters beyond Brallos. Lee, who had understood that he would have to hold the Domokos Pass until the night of the 21st–22nd, had already sent Captain Luxton out to ascertain when the New Zealand troops moving along the Volos road would have passed through Lamia. At dusk Luxton returned with information that the New Zealanders were clear of Lamia, but that Brigadier Allen did not know the whereabouts of his brigade. Thereupon, at 9 p.m., Lee ordered the main portion of his force to withdraw forthwith, but organised a small rearguard to hold astride the road 10 miles farther south. This was at the southern exit from the range separating Lamia from the plain of Thessaly, whereas Domokos was at the northern exit.

Meanwhile at 7 p.m. the road had been blown in several places. In error some demolitions were made behind positions held by the 2/6th and as a result two anti-tank guns had to be destroyed and abandoned. Worse still, at 8 p.m. several vehicles appeared on the road forward of the Domokos force and men climbed from them

and began to repair the demolitions. On Lee’s orders the gunners fired at them until it was discovered that these were trucks loaded with British engineer and ordnance men and Cypriot pioneers, who had been left behind. A patrol was sent out to bring them in and to destroy their trucks. The withdrawal from the Domokos position was completed by 10.30.

Lee appointed Major Guinn18 to command the new rearguard position and instructed him to delay the enemy until the last Australian and New Zealand forces had passed through Lamia. Guinn was not informed of his role until early in the morning on the 20th, and when he arrived at the Lamia Pass his little force – a company of the 2/6th, a company of the 2/7th, a company of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion, a detachment of anti-tank guns, and five tanks – had already been placed in position in the dark by Lieut-Colonel Wells of the corps staff.19 When daylight came Guinn decided that some of the infantry were too exposed to observation from the air, and that if he was to avoid air attack and to surprise the enemy’s troops when they appeared, he must conceal his positions. This was done and troops and guns were well concealed before any scouting aircraft arrived.

The company of the 2/7th was deployed astride the road and to the right of it; the company of the 2/6th on the left and the tanks in a small copse about a mile forward and a mile to the right of the road. About 11 a.m. a German troop-carrying aircraft landed near the village of Xinia on flat land about three miles from the Australian positions, and at the same time vehicles began to move down the slopes from Domokos. Lieutenant Morris20 commanding one of the platoons of the 2/7th collected three NCOs and led them downhill to capture the aircraft. The company commander, Lieutenant Macfarlane, called to them to come back and the NCOs heard and returned, but Morris went on and eventually himself was taken prisoner.

About 2.15 p.m. a group of four German motor-cycles with side-cars appeared, followed at 500 yards by a fifth cycle. The rearguard had been so well concealed on the scrubby slopes that several reconnaissance aircraft which flew low over the pass during the morning and fired into patches of undergrowth evidently failed to detect any of the positions; and the four leading motor-cyclists rode right into the Australian area, where all were killed or wounded by a sudden burst of fire. A little later the fifth motor-cyclist advanced along the road at high speed, saw the wrecked cycles on the road, made a sharp skid turn and got away. At this stage the officer commanding the tanks withdrew his tanks from the wood, where they had been lying concealed and ready to counter-attack.

Later one tank was moved forward to each of the northernmost knolls to engage such German tanks as should appear. An armoured car coming into view was hit by a shell from one of them. A German tank next

appeared, was fired on, and made off in reverse. A rain-storm lasting about half an hour then enabled the Germans to bring forward several mortars which fired until silenced by the Australian machine-guns. Thus far all had gone well. The rearguard was concealed and the enemy came under accurate fire as soon as he appeared across the flat ground at the foot of the pass. At 4.30 p.m. a message arrived from Lee stating that all New Zealand and Australian convoys had passed through Lamia; Guinn was to decide when he would withdraw.

At 5 o’clock the enemy opened fire with four light guns. Guinn had given orders that when the enemy opened fire with artillery the rearguard should withdraw. The tanks began to move out, but one was hit and abandoned in the fields east of the road. The officer commanding the company of the 2/6th on the west of the road then ordered his platoons to withdraw, but told Lieutenant Hayes21 to remain in position near the road until Lieutenant McCaffrey’s22 platoon on the knoll to the left had come in. The company commander had ordered the infantrymen to hurry; and as the men began to move in some haste and confusion up the slopes to the road, the German mortar crews, hitherto unable to find any definite target, saw them and bombs began to drop among the hurrying clusters and amid the machine-guns, which were hot and easily distinguished by the steam rising from their water jackets. Two cruiser tanks held the road while the infantrymen withdrew. After some of the infantry had already embussed Lieutenant Austin’s23 machine-gunners came out, leaving one gun to cover the engineer party which was to set off the charges in the road. Macfarlane’s company of the 2/7th on the right had withdrawn in good order, and when Guinn was told by his officers that all their men had come in he reported to Lee, who had now arrived. Lee told him to go back to Vasey’s brigade. The last of the trucks then withdrew.24

From Allen’s force during the 19th and 20th small parties of the 2/2nd and 2/3rd Battalions arrived in the Brallos area. Colonel Lamb (2/3rd) reached divisional headquarters near Gravia at 3 p.m. on the 19th and reported that he had not seen Allen since early that morning and did not know where the bulk of his battalion was. On orders from Colonel Sutherland, Mackay’s GSO1, he established at Amfiklia a collecting post for any more of his men who might come in. Major Edgar,25 second-in-

command of the 2/2nd, had already established a “straggler post” between Amfiklia and Levadia (whither Blamey’s headquarters had moved on the 18th) and during the day 7 officers and 297 men of that unit had collected, including Hendry’s company and sundry officers and men of the headquarters company. Most of the 2/3rd Battalion’s vehicles after ploughing along the tracks east of Larisa during the night made their way to Lamia either through Volos or by rejoining the main road south of Larisa. By the 20th the 2/3rd had reached a strength of about 500.

Several parties of New Zealanders and men of the 2/2nd and 2/3rd whose vehicles had bogged in the country east of Larisa on the night of the 18th managed by hard marching over the foothills of Mount Othrys to reach the New Zealand Division before it finally withdrew from the Thermopylae position. One party of nine, under Sergeant-Major Le Nevez, reached Volos and there bailed up a car and drove to Lamia. Along the roads followed by these men and by others who escaped to Crete or Turkey, the village women, sometimes in tears, gave them food and the men acted as guides and kept them informed, not always accurately, of the Germans’ progress. Brigadier Allen himself had driven eastward, making for the Volos road, but went along the dead-end road. There he found fifty or sixty men. Leaving one of his officers, Lieutenant Hill-Griffiths,26 with this party with instructions to keep moving south, he himself drove back to the main road, skirting Larisa in daylight. Another small party marched and hitch-hiked for four days and reached Akladi on the north shore of the Gulf of Lamia. There they seized a boat and, with Germans visible in the village and the New Zealand artillery firing registering shots overhead, they rowed across the gulf and on the 23rd joined the New Zealand Division.

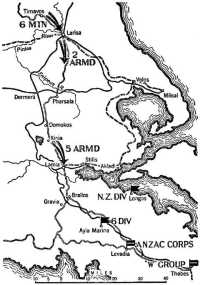

Meanwhile, in the Thermopylae line, the British force awaited the German columns In a message written at Corps headquarters late on the 19th and received by Mackay at 10.15 a.m. on the 20th – the twelve hours delay indicating the congestion on the roads and the difficulty of night driving – the new tasks were defined. General Wilson’s headquarters were at Thebes, Corps headquarters at Levadia, Freyberg’s near Longos. Mackay was ordered to move his headquarters back from near Gravia to near Ayia Marina – a decision of which Mackay disapproved on the ground that it removed his staff 20 miles from the forward troops at Brallos.27 Freyberg was given the task of defending the coastal pass, Mackay the Brallos.

The Thermopylae position was at the neck of the long peninsula embracing ancient Locris, Phocis, Boeotia, and Attica. A watcher standing at the top of the Brallos escarpment and facing north looks down on the large town of Lamia in the plain 4,000 feet below through which the

Sperkhios River runs into the sea. From Lamia the straight main road travels due south across the flats and then zigzags up the face of the escarpment to Brallos and the rolling uplands beyond; a second road branches at Lamia across the Sperkhios and travels eastwards between the foot of the escarpment and the sea.

It was along this coastal route that the army of Xerxes the Persian advanced on Athens, and on a coastal road south-east of Lamia that Leonidas and a gallant company of Spartans were outflanked and overwhelmed by a Persian force which followed a goat track over the foothills and descended in their rear. The silting of the Sperkhios delta in the succeeding centuries had thrust the coastline some five miles to the east, but for “Thermopylae” write “Molos”, and a modern defender of the pass is in a position like that on which Leonidas stood.

The area between Molos and the Brallos Pass covered only one-third of the neck of the peninsula; to the south-west between Brallos and the Gulf of Corinth lay a tangle of mountains rising to 6,000 feet, entered from the west by secondary roads at Gravia and Amfissa. Even if the two passes were held, there would be danger of the defenders being outflanked on both the east and the west – on the New Zealand side by an advance along the island of Euboea, on the Australian either by local flanking movements up the mountain tracks west of Brallos, or by a wider move down the road leading from Epirus, and thence along the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth to Amfissa. Indeed the front was too long to be defended by two divisions – as was pointed out to General Wilson by General Blamey in a message sent on the afternoon of the 20th; Blamey did not then know that a decision to embark had been reached the day before.

On the New Zealand sector the 5th Brigade was deployed along the coast road, the foothills south of Lamia, and the Sperkhios River. The 4th Brigade was on the right where it had established coast-watching patrols, the 6th was in reserve. In the forward brigade the 22nd Battalion, on the right, was on a ridge west of Molos with three companies forward. The 23rd, on the left, had one company on high ground overlooking the coast road, one forward at the bridge over the Sperkhios, another at the bridge over a tributary stream half a mile to the south, and a fourth on the high ground to the south-west linking with the Australian position.

The first Australian infantry to arrive in the Brallos area had been Vasey’s incomplete 19th Brigade – the 2/4th and 2/8th Battalions, the latter far below strength. In the course of 19th April the 2/1st and 2/5th were placed under Vasey’s command, and that day and during the early hours of the 20th the 2/11th rejoined the brigade for the first time since its arrival in Greece.

Early in the afternoon Mackay issued orders for the defence of the new line. He instructed Vasey, with his five battalions, to hold an area from the 1399-metre hill east of the road to the railway tunnel west of Brallos (five miles). Vasey had already placed the 2/5th on the extreme right, to link with the left of the New Zealand Division, the 2/1st astride the

loop in the main road and the 2/4th on the left over the railway tunnel; thus his forward positions were well in advance of the area he was now ordered to hold. In immediate reserve at the top of the pass he placed the depleted 2/8th, and astride the road north of Brallos his main reserve – the 2/11th, a company of the 2/1st Machine Gun, and carrier platoons of the 2/1st and 2/5th Battalions.

The 1st Armoured Brigade which had been resting at Atalandi was now ordered to Thebes. Its 102nd Anti-Tank Regiment, however, was sent forward to Freyberg, who placed it with his machine-gun battalion at Longos, facing the western end of Euboea. The tank regiments had now worn out more of their few remaining tanks – the 4th Hussars had been forced to abandon seventeen on the Lamia Pass. General Wilson ordered the 3rd Royal Tanks to Athens for local defence, and sent the 2nd Royal Horse Artillery to join the New Zealand Division, thus reducing Brigadier Charrington’s brigade at Thebes to one infantry battalion (the 1/Rangers), the Hussars, and the ancillary troops. On the 21st the brigade was further dispersed. The Hussars were sent south to Glyphada, near Athens, under the command of Force headquarters. Because of reports that the enemy had landed on Euboea, whence he might move on to the mainland by way of Khalkis and cut the communications of the British force at Thebes, the Rangers were sent to Khalkis

That day the New Zealand Division’s front was adjusted. The 6th Brigade moved forward to just east of Molos and took over the 28th Battalion’s sector, the 24th taking position north of Molos with its right on Ayia Trias to protect the anti-tank guns on the coast road, the 25th covering the road from Alamanas bridge to Molos, and the 26th remaining in reserve. The 5th Brigade moved the 22nd Battalion to the left of the 25th and the 23rd brought in the company on the heights towards the Brallos road when these were taken over by the 2/5th. Three troops of the 64th Medium Regiment, the thite field regiments of the division, one battery of the 2nd Royal Horse Artillery, the New Zealand anti-tank regiment and the 102nd were in support of the two brigades, and seventeen guns of the 5th Regiment were forward with the infantry to deal with tanks.

During the 21st, on the Australian front, the 2/11th relieved the 2/5th in the rugged, scrub-covered country on the 19th Brigade’s right. At midday on the 20th Savige, whose brigade then included only the 2/6th and 2/7th Battalions, the 2/5th being in Vasey’s, had received orders from Sutherland to guard four road and track exits from the mountains to the west of the Brallos position and cover the Lamia–Brallos road in depth from a point one mile north-west of Brallos. The effect of this would be to echelon the 17th Brigade behind the 19th and protect the left flank. At dusk, however, Savige received new orders, issued to him by Rowell in Mackay’s presence. These were to take over part of Vasey’s left flank and occupy a line covering the gorge through which the railway ran and extending along high ground about one mile to the west of Oiti (Gardikaki) . In addition his left flank was to be refused for a further distance of about a mile and a half. His total front would be about six miles

measured on the map. The road and track exits on the west were now made the responsibility of the 16th Brigade (two weak battalions). In conference on the 21st Savige and Vasey agreed that Savige should take over all the ground which Vasey then held west of the Lamia–Brallos road.

The country on this flank was extremely rugged. A road marked on the map as leading into the area was found to peter out, but another practicable road was found which was not on the map. By dusk on the 21st the 2/7th Battalion was in position from the main road about four miles forward of Brallos to the railway and just beyond, with the 2/6th extending the line for about four miles to the west. That day the 2/5th Battalion returned to Savige’s command and went into reserve just west of Brallos.

Thus, as deployment continued, the disadvantages of the new position became increasingly apparent. Each of the two main roads needed at least a division to defend it, and although the New Zealand Division was still “reasonably complete”, three battalions of the Australian had been greatly reduced in strength.28 It seemed probable that the enemy would make a flanking move along the island of Euboea. The New Zealand Division’s positions could be shelled by guns concealed in the rolling country across the strait, whereas its own guns were in exposed positions on the face of an escarpment or at its foot. The plain of Thebes offered the enemy an excellent field in which to land paratroops in the rear of the defending force, which could spare only a few carriers and other troops to protect that area. The left flank was open to attack by an enemy force moving from Epirus towards Amfissa and the Delphi Pass. This danger was underlined by the news that the “Adolf Hitler” Division had reached Yannina, the Greek Army of Epirus had surrendered, and the way to the Gulf of Corinth lay open.

The last account of the German operations left the head of the 40 Corps at Kalabaka. Thence, in obedience to List’s order, General Stumme ordered the “Adolf Hitler” Division to swing west through the Metsovon Pass towards Yannina against General Pitsikas’ Greek Army of Epirus. It was approaching Yannina on 20th April when Tsolakoglou, to the surprise of both German and Italian leaders, sent his written offer to capitulate to the commander of the advancing German division. Tsolakoglou was flown to Larisa next day and there he surrendered to List’s chief of staff, Greiffenberg. “In recognition of their brave bearing,” wrote Greiffenberg in 1947, “all Greek officers retained their side-arms, and the men were not looked upon as prisoners of war but were to be demobilised at once by the Greek Command and repatriated.”29

On 19th April, after the capture of Larisa, the 5th and 2nd Armoured and 5th and 6th Mountain Divisions followed the retiring British force along the main road to Lamia, German aircraft “repeatedly and successfully” attacking the retreating columns in the Thessalian plain; Volos was entered on the 21st. Cratered roads delayed the German advance.

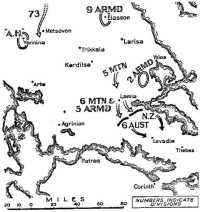

It is evident that at this stage the German commanders had more troops than they could move with reasonable speed. Their maps show that, at dusk on the

21st, from south to north along the Lamia–Larisa road, were strung out the 5th Armoured, 6th Mountain, 2nd Armoured and 5th Mountain Divisions, the 9th Armoured remaining in the Elasson area.

By nightfall on the 20th April no hint that the British forces would be embarked had reached the corps in the field. Mackay and Freyberg had been impressing on their subordinates that there would be no more withdrawals. “I did not dream of evacuation,” said Mackay afterwards. “I thought that we’d hang on for about a fortnight and be beaten by weight of numbers.” Brigadier Vasey commanding the force astride the Brallos Pass had given an order: “Here we bloody well are and here we bloody well stay,” which Bell,30 his brigade major, translated: “The 19th Brigade will hold its present defensive positions come what may.”

As mentioned above, Wavell arrived at Blamey’s headquarters about 2 a.m. on the 21st and informed him that Tsolakoglou had surrendered, and that the British force was to be embarked. Later in the day Wavell gave Wilson a written order to embark the force on the basis of the plan prepared by the joint planning staff, and in cooperation with Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman. Wilson was given liberty to fix the starting day. Subject to the prior needs of the troops under his command he would, as far as possible, embark “any Greek personnel, etc., desired by the Greek Government”. Every soldier must bring out as much equipment as he could carry. The order continued:

Should part of the original scheme fail or should portions of the force become cut off, they must not surrender but should endeavour to make their way into the Peloponnese or into any of the adjacent islands. It may well be possible to rescue parties from the Peloponnese at some considerably later date. You should bear in mind the possibility of later being able to evacuate transport, guns, etc., from the Southern Peloponnesian ports or beaches.

After the conference between Wilson, Blamey and Baillie-Grohman at the roadside near Thebes on the night of the 21st, Blamey returned to Levadia arriving there before dawn on the 22nd. About 8 a.m. Mackay with Sutherland and Colonel Prior, his senior administrative officer, arrived for orders, and were given an outline of the plan. Freyberg’s headquarters were so distant that a liaison officer (Wells) carried the news to him.

Wilson’s detailed order confirming his plan for withdrawal from Greece was not issued until the morning of the 23rd, after Blamey and Freyberg had issued orders based on his verbal instructions. Wilson’s order stated that the force was now organised into Anzac Corps, 80 Base Sub-area, 82 Base Sub-area (formed from the 1st Armoured Brigade), and the following group of units directly under Wilson’s command: 4th Hussars, 3rd Royal Tanks, New Zealand Reinforcement Battalion, Australian Reinforcement Battalion. Those units were in the Athens area; thus not only was it convenient for Force headquarters to control them, but they provided some fighting troops whom it could employ in an emergency.

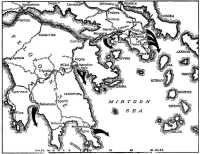

Wilson’s order added that one New Zealand brigade would occupy a covering position on the ridge south of Kriekouki (Erithrai),31 south of Thebes on the Athens road, and named four beaches or pairs of beaches from which embarkation would take place. It also specified the staffs which would be in charge of these, the groups to be embarked, and the nights of their embarkation. The first were to leave on the 24th–25th, the last on the 26th–27th. The embarkation areas were Rafina (“C” Beach), Porto Rafti (“D” Beach), Megara (“P” Beach), Theodora (“J” Beach), Navplion (“S” and “T” Beaches).32 The order added that as many guns as possible were to be brought out; those remaining were to be made useless by removing the breech-blocks, and all gun sights and such technical equipment as could be carried were to be brought away. No fires were to be lit. Certain stores and workshop equipment were to be handed over to the Greeks. Officers and men must wear full equipment but not packs; they might carry hard rations in greatcoat pockets, but no other articles would be allowed aboard the lighters.

Blamey’s order to the corps, issued at 4 p.m. on the 22nd, stated that the covering force at Erithrai would include the 4th New Zealand Brigade, 2/3rd Field Regiment, one Australian anti-tank battery, 2/8th Australian Field Company, and one company of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion. “Except in the case of the move of the covering force to its covering position, only optical and technical instruments, personal arms and equipment that can be carried on the man, automatic weapons and machine-guns, together with what ammunition can be carried on the man will be moved,” it added. “Otherwise technical vehicles not being used for troop-carrying and guns will be destroyed.” This entailed the destruction of all guns except those of the regiment and battery mentioned above – a precipitate step in view of the complications that might ensue. It will be seen that this part of the order was later countermanded.

In daylight on the 22nd reconnaissance parties and certain unessential units were to move south in small columns. That night (22nd–23rd) the covering force should take up its position astride the Athens road, which it must deny to the enemy until early on 26th April. On the 23rd–24th one brigade group from each division, having thinned out during the day, was to move to its concealment area near its place of embarkation, the Australian brigade group to Megara, the New Zealand to Marathon. On the night of the 24th–25th these two groups would embark and the remaining brigade group of each division (the depleted 6th Division having been divided into only two groups) would each move to their allotted

The embarkation beaches

concealment area. On the 25th–26th these groups would embark. The covering force would embark on the 26th–27th. At 8 p.m. on the 23rd Blamey’s headquarters was to close and make its way to its point of embarkation; Wilson’s headquarters would thenceforward directly control all operations.

On 22nd April General Freyberg chose his 5th Brigade to move first to the point of embarkation; it was to go along the coast to Ayia Konstantinos on the night of the 22nd–23rd, and to the Marathon beaches the following night. On the night of the 24th–25th the 6th New Zealand Brigade was to withdraw. Whereas the corps order had implied that only the covering force would retain heavy weapons – and only as far as the covering position – Freyberg ordered units to “retain all their fighting equipment until embarkation”.

Mackay decided that his first brigade group, to withdraw .on the 23rd–24th, should consist of Allen’s depleted brigade (less the 2/1st Battalion), Savige’s brigade, and part of the 2/8th Battalion; it would be named “Allen Group”, Allen, as senior brigadier, being in command. On the 24th–25th Vasey’s brigade – including the 2/1st, 2/4th, 2/11th Battalions, two companies of the 2/8th, the 2/2nd Field Regiment, a battery of the 2/1st, and the 2/1st Field Company – would follow.

While these orders were being issued the artillery duel was becoming hotter along the whole front. The weather was still clear, and German

vehicles were seen moving along the road north of Lamia and small groups of tanks and infantry moved south of that town. As the day went on, however, it became apparent that although three days had elapsed since the enemy had entered Larisa he was not yet ready to attack, presumably because the cratered roads were delaying guns and vehicles.

When the 2/2nd Field Regiment was climbing the Brallos Pass, Brigadier Herring, commanding the 6th Divisional Artillery, had ordered that two guns be pulled out and sited on the forward slope of the escarpment about two-thirds of the distance up the slope to cover the demolished bridge over the Sperkhios River. They were placed 15 feet apart on a mere ledge at the side of the road in the area held by the 2/4th Battalion and with them was an Italian Breda anti-aircraft machine-gun manned by a British crew. About 6 p.m. on the 21st the first German vehicles emerged from Lamia and began moving south along the straight road on which the guns had been carefully ranged. The gunners opened fire at 10,900 yards and, in three rounds, hit and stopped the leading truck, whereupon the remainder hastily retired to Lamia.

Throughout the night these gunners, and observers perched 400 yards farther up the slope, saw the lights of seemingly hundreds of vehicles moving down the pass into Lamia. On the morning of the 22nd four enemy guns – evidently mediums – opened fire from a wood south-east of Lamia well beyond the range of the Australians’ 25-pounders, and a column of vehicles again began moving south towards the Sperkhios. Each time these vehicles came within range the Australian guns opened fire and as regularly the German medium guns replied, their shells bursting closer and closer until they were landing within 15 feet of the gun pits. One German shell hit a truck carrying smoke shells which exploded and covered the area round the Australian guns with smoke for half an hour. A trailer carrying high-explosive shells was set on fire and the shells began to explode. A dump of charges was hit and exploded, setting the scrub ablaze. Some enemy field guns which had been brought forward to the Sperkhios now began to fire, and the Australian guns replied.

By 1 o’clock in the afternoon one Australian gun was out of action through oil leaking from the recuperator. At this stage Lieutenant Anderson,33 the young officer in command, saw that about twenty trucks had come forward to the foot of the escarpment on the left and were unloading infantrymen there. He and his men lifted the trail of the gun on to the edge of the pit so as to depress it enough to fire down the face of the hill and, using a weak charge lest the recoil should cause the gun to somersault, fired more than fifty rounds into the enemy infantry. This drew heavier shelling from the German medium guns. The Australian crews took shelter, and when they returned found that the carriage of the remaining gun had been hit and would not operate. It was then 4 p.m. The duel had lasted eight hours, and although more than 160 shells had burst round

Morning, 24th April

the two exposed guns and dozens of rounds of their own ammunition had been set on fire or exploded and trucks smashed, not a man on the scarred and smoking ledge had been hit. Anderson sent half his men back up the hill with the sights and breech-block of the damaged gun and with his two sergeants, Ingrain34 and Lees,35 and the remaining crew tried to put the other gun into action. The German guns now opened fire with deadly accuracy. One man was killed and another wounded on the hillside some distance above the guns; then, at the guns, five men were killed and three wounded, one fatally, leaving only eight unwounded, including Anderson. At dusk, after the wounded men had been carried out, Anderson and Gunner Brown36 returned to the guns and brought away the sights and striker mechanism, and the discs and paybooks of the dead.

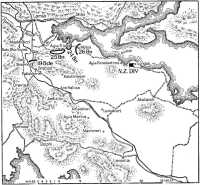

It will be recalled that, in consequence of the decision to embark, the defence of the Thermopylae Pass was left to Barrowclough’s 6th Brigade. The four companies of the 25th Battalion were in position overlooking the road and the river, the 24th astride the road at Ayia Trias, and the 26th in rear of it astride the road at Molos. Seven artillery regiments (four field, one medium, and two anti-tank) were in support – a formidable array. Forward were sixty men of the 22nd in “skeleton positions” on the left of the main position, sixty of the 23rd at the bridge over the Sperkhios and the carriers of the 5th Brigade which were to patrol the flats north of the road at night. On the night of the 22nd the 5th Brigade, having destroyed much of its heavy gear, moved to Ayia Konstantinos, and the 4th Brigade to the covering position at Erithrai.

On the 6th Division’s front the rearward guns of the 2/2nd Field Regiment continued firing at the Sperkhios bridge. In the course of 22nd April German patrols had moved on to high ground west of the road and overlooking the position occupied by the 2/1st Battalion and overlooked by the 2/4th. Because his forward posts were so far from the road Vasey decided to withdraw them about two miles to a more compact position just north of Brallos. The vehicles did not arrive at the right time and on the night of the 23rd–24th the 2/11th Battalion had to make an arduous climb back to the position it had left not long before.

On the 21st and 22nd the troops deployed in and behind the Thermopylae line were attacked from the air as heavily as before.37 On the morning of the 21st a reconnaissance aircraft was flying low over the area occupied by the 2/1st Field Company when Sapper Atkinson38 – a noted marksman – put a Bren gun to his shoulder and fired a burst into the plane which

seemed to stop in mid-air (wrote the unit’s diarist), nosed over, hit the ground and exploded in a burst of flame and thick oily smoke.

The 23rd April again was fine. During the day it was reported that the enemy had landed on Euboea. Reconnaissance aircraft saw no movement on the island but nevertheless Wilson’s staff were anxious about the safety of the crossing at Khalkis. Freyberg was ordered to take what action he could to reinforce the 1/Rangers there, and Charrington to hold the crossing until 9 p.m. on the 25th when the 6th Brigade would be well south of it. He was told that the 6th would leave a rearguard on the high ground north of Tatoi until the Rangers had passed through. Thereupon the Rangers withdrew a company that had been placed on the Euboea side of the crossing and blew charges on the bridge.

In the Thermopylae sector during the 23rd the British medium guns, under intermittent attack by dive bombers, engaged German artillery east

of Lamia. In the evening a German advance towards the Sperkhios bridge was stopped by the detachments of the 22nd and 23rd Battalions (which withdrew during the night, the infantry to Molos and the carriers to a rearguard force under Colonel Clifton at Cape Knimis) Thinning out had continued during the day. The 4th Field Regiment, less a battery, withdrew and joined the 5th Brigade, which moved during the night to its concealment area near the embarkation beach at Marathon.39

On the 23rd the 19th Brigade withdrew to its new position at Brallos. A rearguard was formed by two companies of the 2/1st Battalion on top of the pass overlooking the Lamia plain. After having put these companies in position Colonel Campbell reconnoitred a circuitous mountain road along which they could withdraw next day.

Meanwhile the possibility of the enemy cutting across the line of retreat by way of the Delphi Pass was causing uneasiness at Wilson’s headquarters. Greek headquarters ordered a detachment of infantry and anti-tank guns to Navpaktos and a battalion (the Reserve Officers’ College Battalion – perhaps the only competent unit left to them) to Patras with some field guns, the task of the two forces being to prevent an enemy advance along either the north or south shore of the Gulf of Corinth. General Wilson sent also to Patras the 4th Hussars, its fighting vehicles now reduced to twelve light tanks, six carriers and an armoured car, and most of its men organised in rifle troops. In the morning the air force reported that there was no significant movement along the road leading from Yannina, but early in the afternoon a report reached Blamey’s headquarters that hundreds of vehicles were streaming south from that town. Rowell calculated that they might reach Delphi next day, and informed Blamey, who decided to demolish the road at Delphi and establish a force covering it.

He ordered Brigadier Steele to damage the road so thoroughly that the enemy would be delayed for twenty-four hours even if the demolitions were not defended. Steele collected a party of sappers and took them some 30 miles towards Amfissa. As they returned they destroyed bridges and culverts and cratered defiles Finally Steele reconnoitred a site covering the last demolished bridge about three miles east of Levadia. The force to occupy this position was detailed by General Mackay and consisted of the 2/5th Battalion (Lieut-Colonel King) with a troop of field guns and a company of machine-gunners. King’s column drove throughout the night with lights on40 (German aircraft had rarely attacked at night) and by dawn was in position three miles west of Levadia covering demolitions in the road.

On the 22nd the German Air Force again attacked the Athens aerodromes in force and Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac had sent the remaining Hurricanes to Argos, where on the 23rd the Germans struck again and

destroyed thirteen of them on the ground. D’Albiac ordered the remainder to Crete.

At Athens the King of Greece announced that he would transfer his government to Crete and continue the fight there. The officers of the British Base Sub-area in Athens paid all outstanding accounts, the supply depot was handed over to the Greeks,41 the canteen stores to the American Red Cross, and the Pioneer Corps companies (mostly Palestinians, Arabs and Cypriots under middle-aged British officers) were taken by train to Argos and Navplion. A party of New Zealand nurses and 400 walking wounded were sent to Argos, and other wounded to Megara.

At 3 a.m. on the 23rd Colonel Rogers, Blamey’s senior Intelligence officer, and six other officers42 appointed by Blamey to report at Wilson’s headquarters for embarkation duties, had arrived at Athens. Searching for an officer of Wilson’s headquarters who could give him instructions, Rogers at length found Major Packard43 of Wilson’s staff who appeared to be coordinating all arrangements with the navy. Packard said that the Australians’ role would be to provide beach parties for Rafina, Porto Rafti and Tolos. Rogers appointed these parties, and detailed officers to establish liaison with the New Zealand and the Australian divisions and to ensure that the groups knew the routes they should follow.44

On the night of the 23rd–24th the withdrawal of the 17th Brigade from its position on the left of the line and the movement of the combined 16th and 17th Brigades to Megara to await embarkation were achieved remarkably smoothly. Savige’s orders provided that the 2/6th Battalion on the left would begin thinning out at 7 p.m. and hold its forward posts until 9, the 2/7th would begin thinning out at 8.30 and hold its forward posts until 9.30. Despite the fact that the forward battalions were deployed over a six-mile front and had to scramble out of extremely rough country, the time-table was adhered to. At daybreak Colonel Prior of Mackay’s staff halted the column at Eleusis, where there was good cover and, all that day (the 24th), the men of “Allen Group” lay concealed and resting in olive groves on each side of the Athens road. The diarist of the provost company of the 6th Division underlined the wisdom of Mackay’s order that lights (dimmed) should be used in the withdrawal.

Orders were that Div troops would pass starting point at the junction of the Atalandi–Athens roads 15 minutes after N.Z. troops had passed through about 0000 hrs, and 16 Bde about 0300 hours. The N.Z. troops and vehicles coming through had no lights and march discipline was poor, consequently there was considerable delay ... and the end of the column did not pass until 0130 hrs ... much congestion at Levadia due to Greek troops trying to cut in. From then on only trouble occasioned by odd groups of vehicles. Traffic control excellent and an average speed of 20 M.I.H. (miles in the hour) was maintained until camping area was reached near Eleusis. Distance covered [by 6 Div troops] was 72 miles and all troops reached their destination by 0700 hours . ... A very remarkable performance considering the heavy traffic on the road, entirely due to good traffic control.

The operation order for the embarkation was the last which Anzac Corps issued. At 8 p.m. on the 23rd, Corps headquarters closed at Levadia and opened at Mandra. It ceased to function at midnight on the 23rd–24th. At that time General Blamey reported to General Wilson in Athens and was ordered to embark next morning in a flying-boat for Alexandria, where he was to see Admiral Cunningham “and press on him the urgency of their position”. Blamey then returned to Mandra and informed Rowell of this order. He told him also that Wilson had said that it would now be impossible for troops to embark from the Athens beaches as arranged and that the plan would have to be revised to provide for embarkation of larger numbers from beaches in the Peloponnese. Rowell protested that, in view of this changed situation, Anzac Corps headquarters should remain, but Blamey replied that he had been ordered to go.

Blamey arrived at Alexandria at midday on the 24th and immediately saw Cunningham who (in Blamey’s words) “had not till then been fully impressed with the full seriousness of the position, and immediately sent out all available vessels to assist”. On the other hand Cunningham had been informed on the 22nd that the first day of the embarkation had been advanced to the 24th, and enough ships to carry out the first embarkation had been sent out.

When he reached Egypt Blamey was appointed Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in the Middle East. On 26th February he had informed Mr Menzies that he had suggested to General Wavell that, since Australians were to form the largest contingent in Greece, he (Blamey) should command the whole force. This suggestion, which was later raised by Mr Menzies at a meeting of the British War Cabinet, was not accepted. In April, however, the Secretary of the Australian Defence Department, Mr Shedden, who was with Menzies in London, suggested that Blamey be considered for the Western Desert Command. On 19th April Menzies discussed Blamey’s future with Dill, who consulted Wavell. Wavell recommended that Blamey be appointed his deputy, the Australian Government concurred, and Blamey took up the new appointment as from 23rd April – thus, incidentally, becoming senior to the commander under whom he had just been serving in Greece.

When Anzac Corps headquarters closed direct control of the embarkation passed to Wilson’s headquarters. On the afternoon of the 24th both

Mackay and Freyberg received an order from that headquarters that they and their staffs were to embark that night. In consequence of this order the officers and men of Mackay’s headquarters set off for the Argos area, their appointed place of embarkation, late that afternoon. Mackay and his aide-de-camp embarked in a flying-boat and were flown to Crete early next morning. The remainder had sailed in a cruiser during the night.

Freyberg, however, disregarded the order to embark. When it arrived his forward troops were in the midst of a hard fight against German tanks at the Thermopylae Pass. Freyberg wrote later:

I cabled back to G.H.Q., Athens, and told them I was being attacked by tanks, fighting a battle on a two-brigade front, and asked who was to command the New Zealand troops if I left. I was given the answer of “Movement Control”. I naturally went on with the battle. After that I never received an order as to my disposal.

At this stage three Australian brigades, three New Zealand brigades, one British brigade, and the throng of base units, labour battalions and Yugoslavs were still in Greece. If Freyberg had obeyed the order to embark only Wilson’s staff would have remained to control seven fighting formations, several detached units, and a multitude of base troops.

On the 24th (as Wilson had forecast to Blamey) the plan of embarkation was revised with the object of moving farther south, reducing the numbers to be lifted from Theodora, Argos and Navplion, and making more use of destroyers and of the comparatively distant beach at Kalamata. Finally Theodora was abandoned and Brigadier Parrington45 was sent to take command at Kalamata. Arrangements were made also to take aboard there about 2,000 Yugoslav soldiers and refugees who had retreated down the Greek peninsula. Under the revised plan one of the largest groups, Allen’s combined 16th and 17th Brigades, would not embark from Megara on the 24th–25th but would move to the Argos area and possibly make a further move to Kalamata and not embark until the 26th–27th. The embarkation would now probably be made as follows:–

| April | Athens Beaches | Megara | Navplion | Tolos | Kalamata |

| 24th–25th | 5 Bde | – | Corps, R.A.F. etc. | – | – |

| 25th–26th | 19 Bde, part 1 Armd Bde | – | – | – | – |

| 26th–27th | 6 Bde part 1 Armd Bde | 4 Bde | Base details, 3 R Tanks, 4 Hussars | Base details | 16 Bde, 17 Bde, 4,000 base |

The error of ordering the corps and divisional commanders from Greece was now clearly revealed. Under the new plan Allen Group would embark

not that night from Megara, at the same time as its divisional staff embarked from Navplion, but two nights later, and probably from a beach more than 100 miles away. Allen’s staff consisted only of his brigade major (Hammer); his Intelligence officer, Captain Lovell;46 and two young junior officers from the divisional staff (Captain Vial and Lieutenant Knox47) ; yet the strength of his group approached that of a division – it included seven battalions and two artillery regiments.48 He organised it into four sections: the 16th Brigade and attached troops under Colonel Lamb; 17th Brigade and attached troops under Brigadier Savige; a section including the machine-gun and anti-tank unit under Lieut-Colonel Gooch;49 and a section including the corps engineers and signallers and others under Lieut-Colonel Kendall.50

The revision of the plan of embarkation made it necessary to take new defensive measures especially against possible German paratroop attack at Corinth and in the Peloponnese. A small force of New Zealand engineers and infantry and British anti-aircraft artillery (“Isthmus Force”) was sent to Corinth to prepare demolitions and keep the roads open. In addition Brigadier Lee was appointed area commander in the Peloponnese with the special task of guarding the now-abandoned airfields.

On 24th April the capitulation of the Greek Army had been confirmed. General Papagos resigned. One of the last orders to the Greek troops had been to keep off the roads of southern Greece to facilitate the movement of the British force. That day King George and some of his Ministers left Athens in a flying-boat for Crete to re-establish the government there.

It will be recalled that in the Molos bottleneck the 24th Battalion was on the right, the 25th on the left and the 26th in reserve. The junction of the forward battalions was the main road, whence the front of the 24th ran north-east to the sea, and of the 25th westward along the road to within three miles of the Alamanas bridge. The gap between the 25th’s left and the right of the Australians in the Brallos Pass could not be effectively covered by fire. The dried marshes to the north were passable by tanks and it seemed clear that an effective tank attack on the Molos position could come only from that direction and that a tank attack along the road could easily be dealt with. Consequently the field guns were sited where they could fire most effectively on the marshes. The two battalions were supported by a medium regiment, four field regiments (three New Zealand, one Royal Horse Artillery), two anti-tank regiments and a light anti-aircraft battery.

The fight began in earnest about 2 p.m. on the 24th, when two German tanks moving across the swamp land in front of the 25th were knocked out at long range by field guns. No other tanks attempted to cross the marshes. Motor-cyclists and cyclists, followed by four tanks, then drove along the road. The infantry moved into the hills south of the road when the 25th Battalion fired on them; soon the left of that battalion was under heavy fire from the hills west and south-west and was gradually pushed back. About 3 p.m. the main German attack opened. A group of tanks pushed along the road followed by lorry-loads of infantry and more tanks. Heavy and accurate artillery fire was brought down, but within an hour tanks were getting close to the 25th. One thrust at 4 p.m. was pushed back, but another heavier one followed and tanks advanced into the infantry positions. Numbers of these were hit by field gunners of the 5th Field Regiment, the foremost troop of which was largely in front of the infantry. One gun under Lieutenant Parkes51 hit tank after tank at ranges from 400 to 600 yards. With burning hulls in front of them and behind them, some of the surviving tanks tried to get away but mostly failed to manoeuvre past the derelicts blocking the road. They were shielded, however, by tanks knocked out in front and screened by smoke and turned their fire on to the 25th Battalion, which suffered heavily.

By 5.15 p.m. fourteen tanks had advanced almost to the extreme right of the 25th. Two more then advanced but the leader was quickly destroyed by the guns when it reached a little bridge on the right boundary of the 25th. For six miles westward from the bridge wrecked tanks were smoking. At least fifteen were knocked out during the day and many others damaged. One gun, whose layer was Bombardier Santi,52 had set nine tanks on fire; this gun and another destroyed a total of eleven between them.

At this stage Brigadier Miles,53 commanding the artillery, ordered defensive fire by three regiments on the road by Thermopylae and this defeated all further attempts to bring tanks forward. Towards the end of the day, however, penetration to the rear of the 25th became threatening. It was countered by sending two carrier platoons into the hills and two companies, one from the 26th and the other from the 24th, to extend the 25th’s flank. After dark, drivers drove boldly along the road past the destroyed German tanks and picked up the gallant crews of those guns that were now in front of the infantry. During the day enemy air attack had little effect on the fighting, though it made movement difficult behind the front.

In the afternoon Freyberg had received the disturbing news that the trucks of the ammunition column which were to carry out some of the infantry could not be found. He immediately told Miles that as many of the infantry as possible were to be carried on the artillery vehicles, and the remainder would march. After dark the enemy infantry pressed forward

with determination and the artillery duel continued. At 9.15 p.m. the good news arrived that the ammunition vehicles were on the way, and soon afterwards the troops began to thin out and board them. The medium and field guns were destroyed, the last of them – guns of the 2nd Royal Horse Artillery – at 11.50. By midnight the last vehicles were clear of Malos and the long column was moving south through the rearguard at Cape Knimis and thence to Atlandi. Thenceforward they drove with full lights on, down the main road and through the main rearguard at Erithrai.

By midday the column had travelled 100 miles and was passing through Athens. Miles had been sent forward to Athens to arrange for Force headquarters to picquet the street corners and guide the column through, but he arrived at the Acropole Hotel only in time to meet the last two officers of Wilson’s staff leaving it. Consequently he had to determine a route, return to the head of the column, meet the leading trucks, and post at street corners utterly weary men who had fought the previous day and travelled that night and half the next day.

In Athens the long column of battered, muddy trucks, many bearing the scars of battle, had “a most pathetic, touching reception”.

No one who passed through the city with Barrowclough’s brigade will ever forget it. Nor will we ever think of the Greek people without the war recollection of that morning-25th April, 1941. Trucks, portees and men showed plainly the marks of twelve hours battle and the 160 miles march through the night. We were nearly the last British troops they would see and the Germans might be on our heels; yet cheering, clapping crowds lined the streets and pressed about our cars, so as almost to hold us up. Girls and men leapt on the running boards to kiss or shake hands with the grimy, weary gunners. They threw flowers to us and ran beside us crying: “Come back – you must come back again – Good-bye – Good luck.”54

“They appeared heart-broken,” wrote Freyberg, “that our efforts to help them had brought disaster upon our force.”

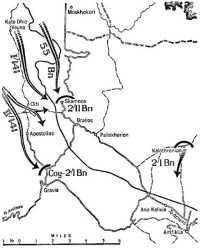

Meanwhile on the left flank, high in the hills, the 19th Brigade had also felt the weight of the German attack. Astride the main road, the 2/11th Battalion now commanded by Major Sandover,55 Colonel Louch having been invalided out, was deployed with one company (Lieutenant McRobbie) to the east of the road, two (Captain Jackson56 and Captain Wood57) west of it and one company in support. The battalion did not finish arriving in its new position until 5 a.m., after a long night march from its former position in the hills on the right. To the right of the 2/11th and under its command was a group of one officer and 48 men of the 2/8th. The 2/1st Battalion (less two companies) was covering the tracks leading through Kalothronion to the right rear of the 2/11th’s position.

One company of the 2/1st, under Captain Embrey, was detached to cover demolitions in the defile at Gravia through which ran a road from Amfissa, toward which, as mentioned above, German troops from Epirus were reported to be advancing. The 2/4th Battalion was in position astride the road five miles south of Brallos. Vasey ordered that the 2/1st was to retire on to the main road during the 24th, arriving there about 6 p.m.

The gun positions of the 2/2nd Regiment had been severely attacked by air- craft on the 23rd; foreseeing other raids, the commanding officer, Colonel Cremor, ordered that the guns be moved at night to new positions 1,000 to 1,500 yards to the rear, but that camouflage nets be left over the old pits. These pits were in the area now occupied by the 2/11th Battalion, which adjusted its positions to keep well clear of them. In the morning 65 dive bombers came over and in two hours made 125 bombing attacks on the abandoned positions then occupied by Captain McPherson,58 observing for the regiment, and four men.

Early in the morning of the 24th German trucks were seen in the distance crossing the repaired bridge over the Sperkhios and tanks moving south along the road and then wheeling eastwards against the New Zealanders. At 11.30 machine-gunners (of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion) attached to the 2/11th began firing on advanced enemy infantry on the near side of the railway line; there was intermittent fire throughout the day until at 4.50 the enemy began showering mortar bombs on the left company of the battalion, killing or wounding the commander (Wood), all the section leaders and eight others in one platoon, and disabling one of the supporting Vickers guns. This bombardment was the prelude to a determined attack. At 5.40 after exchanges of fire in which Germans were shot on the edge of the scrub at 30 yards’ range, the forward companies were withdrawn. Sandover brought his reserve company (Captain

McCaskill59) forward to a hill to the south of the vacated ground which it and the attached machine-gunners covered with fire.

By this time the 2/1st had withdrawn to the main road, as planned, and was facing the mountain road along which it had come. On the western flank, however, German infantry had appeared to the west of Gravia about 6 p.m., and there Captain Embrey’s detached company of the 2/1st exchanged fire with them until dusk. Also about 6 o’clock Vasey, fearing a break-through on the 2/11th’s front, decided to accelerate the withdrawal by ordering the 2/1st, 2/4th and the attached troops to embus at 8 p.m., not 8.30 as planned; and told Sandover that he need hold his positions till 9 p.m. only, not 9.30 p.m.

After Vasey had withdrawn the 2/1st, except for Embrey’s company, the German infantry were firing on the right company of the 2/11th and on the detachment of the 2/8th Battalion on high ground on the right flank. Sandover withdrew the latter to Brallos village and reinforced his left company with two carriers. Meanwhile Captain Honner, his second-in-command, had organised a new position placing survivors of Wood’s company on a line to the left of the road to the rear of the forward companies. Jackson’s company was now withdrawn to the new position. The battalion was firmly in position but in danger of attack on either flank. However, the German infantry seemed to tire, and whereas at 8 o’clock they were still thrusting hard, half an hour later there was no real pressure on the West Australian posts. Sandover ordered the two forward companies to begin withdrawing at 8.50 and abandon their positions at 9, falling back through the companies deployed astride the road to the rear.

Originally the 2/2nd Field Regiment had been ordered to destroy its guns at Brallos, but later in the afternoon Cremor was ordered to preserve them and move them south, each with thirty rounds of ammunition. At that stage there were not thirty rounds a gun remaining, and they were still in action. So that some shells would be left, firing was reduced to one round from each gun every five minutes – enough merely to remind the enemy that they were still there. At 8.30 p.m. the guns were withdrawn. The only road that would carry heavy and concentrated traffic was the main road through Brallos. On Vasey’s orders the 2/1st Field Company, equipped only with hand tools, air compressors and a limited quantity of explosive, had made a track some three miles long from Brallos north-east over very rough country to the gun positions. This was used to withdraw the 2/2nd Field Regiment, and then was demolished by the engineers who had so recently made it.

At 9 p.m. McCaskill’s company of the 2/11th withdrew along the main road and McRobbie’s round the right flank. Just as McRobbie’s last platoon was leaving its position Corporal Brand60 was badly wounded and the

platoon returned to its posts for ten minutes to ensure that he was carried safely to the rear.

Meanwhile the 2/8th detachment had been sent back to Brallos to embus and Embrey’s company of the 2/1st had been called in. There was now no pressure on the main rearguard position. When the road behind the rearguard was clear Homier, whom Sandover had left in command of the forward companies while he supervised the embussing at Brallos, started a leap-frog withdrawal, one company moving back a few hundred yards and the other then moving through it. The embussing was slow because each vehicle had to reverse down a side track to turn. While it was in progress Bell, Vasey’s brigade major, appeared and said that Vasey was anxious lest the enemy troops who had been moving round the western flank and appeared to be in Gravia should reach the Ano Kalivia road junction before the brigade had passed it. Bell at once left with three carriers with the intention of blocking the southern road. At 10.15 as the last trucks moved off south-east along the road, the men kneeling in the vehicles with their automatic weapons pointing outwards, German Very lights were rising 500 yards south of Brallos.

There remained one other rearguard to the north of the force at Erithrai – King’s 2/5th Battalion group in position just west of Levadia covering the road leading through Delphi. As mentioned earlier it had been placed there on the 23rd because of reports that German vehicles were moving along the road from Epirus in the direction of Delphi and might cut the Athens road. In fact they were probably Greek vehicles. The German advance from Yannina had not yet begun. Untroubled, the 2/5th moved out from its positions at 3 a.m. and drove south to rejoin (it hoped) the 17th Brigade to which it belonged. Thus, by the early morning of the 25th the whole of “W” Group had moved through the rearguard at Erithrai and, again, miles of cratered roads separated it from the advancing German army.

On 20th April the four German divisions which had been in action in the Aliakmon–Olympus area were bunched between Elasson and Larisa, and the pursuit of “W” Group was taken up by the 5th Armoured Division. This formation had made a remarkably rapid march: from Sofia, which it left on 7th April, it had advanced north-west to Nish in Yugoslavia, helped to disperse the defending forces there, swung south in the wake of the corps which was moving down the Florina Valley, and reached Monastir on the 13th. Three days later it was at Grevena, and, on the 18th, was approaching Kalabaka, whence, travelling through Karditsa not Larisa, it cut in and reached the Larisa–Lamia road ahead of the 2nd Armoured Division. It advanced to Lamia, where the 6th Mountain Division joined it on the 23rd. The attacks on the Thermopylae position were made by these divisions and part of the 72nd. The German plan was to send a mountain regiment through the hills west of the Brallos Pass towards Gravia, while the main force attacked along the coast road towards Molos.

The force which was to encircle the Anzac left flank at Gravia included the I and II Battalions of the 141st Regiment and a dismounted motor battalion of the 5th Armoured Division. It reached Kato Dhio Vouna early on the 22nd and thence found it very heavy going. At 2 p.m. it reported seeing “English outposts” withdrawing south and east. By nightfall the troops of the motor battalion were “completely exhausted”, and from 11.30 p.m. onwards they were shelled, and got little

Dusk, 24th April

rest that night. The next day was spent resting and reorganising. The Commander, Colonel Jais, decided to attack toward Brallos at 6 a.m. on the 24th. On the morning of the 24th the German commanders learnt that the main body of the defending force had withdrawn. In consequence the II/141st Battalion was ordered to advance south-east and cut the road about five miles south of Brallos while the remainder of Jais’ group attacked towards Brallos. At 7.30 a.m. dive bombers attacked the Australian positions. The main thrust against the 2/11th was made by three companies of the 141st Mountain Regiment and two of the 55th Motor Battalion, with a machine-gun platoon and a heavy mortar section attached to each company. The 55th was effectively shelled and at 11.30 was pinned down by artillery and machine-gun fire. “It seemed almost impossible to get out of the zone of fire and advance,” the battalion reported. “Any movement, even by individual men, was seen by the enemy and engaged at once with HMG fire. We lost one killed and several wounded. It took several hours for the troops to approach the enemy and reach the northern slope of the heights just west of Skamnos.”

Later the I/141st on the right drew level with the 55th at midday and the enemy artillery fire was switched on to it. During the afternoon the Germans continued to press forward and about 6 p.m. came under fire from heavy machine-guns which were well camouflaged and had not fired before. At this stage, however, their heavy mortars arrived forward and these silenced one Australian post after another. According to the German account, the attackers then “stormed” Skamnos at 7 p.m. and the positions south-west of it about 8 p.m. (This is an exaggeration; the forward Australian companies were still in position at 9 p.m. and the German pressure slackened about 8.30.) At 8.30 the leading company of the 11 Battalion was a few hundred yards from the Brallos–Gravia road. About midnight the leading Germans reached Paliokhorion.

The attack towards Molos on the New Zealand front was opened by a reconnaissance unit, a cavalry squadron, two cycle squadrons and an infantry battalion. These made insignificant progress and in the afternoon a company of 18 tanks, including four Mark IV’s armed with 75-mm guns, advanced. Twelve of these became total losses, and, of the 70 who manned them, 7 were killed and 22 wounded. The other units appear to have suffered about 70 casualties.

This was the second time within a fortnight that German armoured forces, hitherto seemingly invincible, had been halted with heavy loss by resolute infantry and artillery. At Tobruk on 11th April an attempt to break into that fortress had been defeated, the Germans leaving 17 wrecked tanks on the field. About the same number were knocked out at Thermopylae, though the Germans regarded only 12 as total losses. On 1st May a similar attack would be defeated at Tobruk, with even heavier casualties.