Chapter 7: The Embarkation from Greece

While the rearguards were travelling south from the Thermopylae line on the night of 24th–25th April the first of the three big embarkations provided for in the plans of “W” Group was carried out.1 At Porto Rafti the embarkation of the 5th New Zealand Brigade Group and other units totalling about 5,750 was achieved without a hitch, under the direction of a team of Australian officers led by Major Sheppard,2 the legal officer of the 6th Division. The troops lay under cover until after dark, when they were marched to .the beach and ferried to Glengyle and the cruiser Calcutta in two landing craft. The ships took them aboard at the rate of 1,500 an hour until, about 2 a.m., there were some 5,000 in the transport and 700 in the cruiser and they sailed.

The evacuation from Navplion and Tolos Bay proceeded less smoothly – on this and later nights – partly because there the men were drawn largely from a variety of base units and were less well-organised than those of the fighting formations. Embarkation was controlled by Lieut-Colonel Courage;3 Major O’Loughlin4 was in charge of the dispersal area. There was an Australian staff at Tolos and a British at Navplion. At 6.30 a.m. on the 24th O’Loughlin found the little town of Navplion crowded with men and vehicles. Having selected eight dispersal areas and placed officers and NCOs in charge of them he sent the officers into the town to find unit commanders and instruct them to lead their units out to one of the dispersal areas. By 10 a.m. the town had thus been emptied of most organised bodies and their vehicles, and contained only small groups, stragglers and abandoned trucks. A section of the 2/2nd Field Workshop Company was given the task of moving abandoned vehicles out of the town, and the stragglers were assembled into a single party and led to one of the dispersal areas, each of which had been chosen with the object of housing about 1,000 men and 150 vehicles.

Between 7,000 and 8,000 men collected in the Navplion area during the 24th, though only 5,000 had been planned for. After dark in bands of fifty they marched through the streets, which had been bombed and machine-gunned during the day and were strewn with glass; and at 10.30 began to embark in barges and ships’ boats. All went well until the transport Ulster Prince ran aground at the harbour entrance. She was refloated but ran aground again near the wharf. However, by 3 a.m., despite the loss of the Ulster Prince, 6,600 men (1,600 more than the pre-arranged

number) had been embarked in the ship Glenearn, the cruiser Phoebe, the destroyers Stuart and Voyager, and the sloop Hyacinth.5 The troops who embarked included Australian Corps headquarters, 6th Australian Divisional headquarters, the 4th Survey Regiment, 16th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery, base troops, and about 150 Australian and New Zealand nursing sisters who were carried in Voyager. There was no embarkation from Tolos that night.

Meanwhile, an effort to embark troops from Piraeus that day had ended disastrously. On the 24th the large yacht Hellas arrived at that devastated port. Her captain said that she could carry 1,000 passengers; she took on board some 500 British civilians, mostly Maltese and Cypriots, and about 400 wounded and sick men from the 2/5th Australian General Hospital, and about as many from the 26th British General Hospital. At 7 p.m. German aircraft attacked, hit her with two bombs and set her on fire. Passengers and wounded men were trapped in burning cabins; the only gangway was destroyed, and eventually the ship rolled over. Estimates of the number who died range from 500 to 742. Among them was the mortally wounded Colonel Kay,6 commander of the 2/5th Hospital, who was organising the embarkation of patients.

During the night of the 24th–25th Allen Group moved out from Megara under orders to go to the Argos area for embarkation. At 1.30 a.m., as the long column was passing over the Corinth bridge, Brigadier Savige was stopped by a staff officer from Brigadier Lee with a request that he detach a battalion to Lee’s force to help guard the area against possible attack by German armour from the north or against paratroops. Savige ordered his staff captain, Major Bishop, to halt the 2/6th Battalion and instruct Lieut-Colonel Wrigley to detach a force for this task, and himself went on to meet Lee who “seemed to have little information about the plan of embarkation”. It was finally agreed that three companies of the 2/6th plus two platoons should be deployed on tasks nominated by Lee.

In consequence Captain Dean’s7 company was halted and placed on the north side of the canal in defence of the bridge, under command of Colonel Lillingston of the 4th Hussars; and Captains Jones’8 and Carroll’s9 companies with two platoons of the remaining rifle company were halted by

Lee near the two adjoining airfields north of Argos. Lee ordered Jones, who was senior to Carroll, to place one of these companies to defend the airfields and send another to join the 4th Hussars at Corinth; it was to travel in one-ton vans so that parties with their own transport could be attached to scattered detachments of the Hussars. Jones took his own company back; having obtained twelve vans from his battalion at Argos, he drove forward, and about 5.30 arrived at the edge of Corinth where he was halted by General Freyberg, bound for a new headquarters near Miloi. Freyberg informed him that Corinth had been bombed and the road was out of action and beyond repair. After hearing of Jones’ task, Freyberg said that the object of the force at Corinth was to ensure the withdrawal of 6,000 troops to the Peloponnese, and the Australians could best serve this purpose by clearing a detour through the town, otherwise there would be a traffic jam and the stationary column would be bombed. Jones set his men to work under attack by German aircraft flying low above the roof-tops.

Later Colonel Lillingston allotted Jones the task also of defending a ridge running parallel with the road south of the canal against low-flying aircraft and paratroops. Jones returned to Corinth and found that his men, in spite of fatigue and frequent attacks by aircraft, had almost completed the new route. He left small parties to finish and maintain the work, and took the remainder out of the town, leaving it about 9 p.m. “just as the leading vehicles of the withdrawing column reached the beginning of the detour”. The company was in position by midnight and spent the remainder of a second almost sleepless night digging weapon pits.

In order to avoid heavy loss of ships as a result of air attack against vessels operating off the beaches near Athens, the staff of “W” Group radically amended the plan of evacuation with the objects of guarding the beaches of Attica and the Peloponnese against attack from the north and north-west, and embarking more men at beaches farther south. Inevitably this necessitated prolonging the period of embarkation.

As noted above the embarkations on the 25th–26th and 26th–27th were to have been:

25th–26th: 19th Brigade and others, from Athens beaches;

26th–27th: 6th Brigade and armoured brigade from Athens beaches, 4th Brigade from Megara. Various units from the Argos beaches. 16th and 17th Brigades and others from Kalamata.

The new orders by Group headquarters now required the 4th Brigade to hold at Erithrai 24 hours longer and move to the south bank of the Corinth Canal on the 26th–27th; and the 6th Brigade to move from the Athens area to Tripolis in the Peloponnese, there to block the roads leading north-west and south-west. In eastern Attica Brigadier Charring-ton was ordered to establish a rearguard including the 1/Rangers, part of the New Zealand Cavalry, eight New Zealand 25-pounders, and twelve New Zealand anti-tank guns, to hold the high ground north of Tatoi, thus guarding the Athens beaches from the north, until dusk on the 26th, and

then withdraw to Rafina for embarkation on the 26th–27th. That night 8,000 troops of many units were to embark at Kalamata and a similar number at the Argos beaches. The withdrawal of New Zealand troops after the night of the 26th–27th (when the 4th Brigade and Isthmus Force would be on the south bank of the Corinth Canal and the 6th Brigade round Tripolis) was to be “directed with all possible speed on any or all of the following”: Monemvasia, Plytra, Githion and Kalamata – all on the south coast of the Peloponnese.

The new plan required that the New Zealand troops and those attached to them should embark at these southern beaches on the 28th–29th and 29th–30th “in approximately equal proportions”. Those left over at the Argos beaches on the 26th–27th were to “proceed as quickly as possible” to Monemvasia, Plytra or Kalamata. On the 25th–26th the 19th Brigade Group would be embarked from Megara and not the Athens beaches.

As a result of these orders Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell was informed on the 24th that the numbers to be embarked would be:

25th–26th: 5,000 from Megara;

26th–27th: 27,000;

27th–28th: Nil;

28th–29th: 4,000 from Githion and Monemvasia;

29th–30th: 4,000 from Kalamata, Githion and Monemvasia.

Thus a program which was to have been completed with the lifting of five brigades and thousands of unbrigaded troops on 26th–27th was now to be extended for three more nights. It provided that, on the night of the 26th–27th, Freyberg, having withdrawn his 4th Brigade and Isthmus Force to the south bank of the Corinth Canal, would blow demolitions there to impede the pursuit. Freyberg was to take command in the Peloponnese as soon as he passed south over the canal on the 25th. He ordered the remaining squadron of his cavalry regiment with the carriers of the 22nd and 28th Battalions to the Corinth Canal to help hold the bridge.

Meanwhile, at the Argos airfields, Lee had assembled a force consisting of one company and two platoons of the 2/6th Battalion (mentioned above), a squadron of the 3rd Royal Tanks, the men of the 2nd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment (their guns having been destroyed) and two anti-tank guns.10

In accordance with this revised plan the only formation to be embarked on the 25th–26th was the 19th Brigade Group from Megara. About midday Wilson’s staff had decided that this brigade group plus the 1,100 wounded at Megara could not all be embarked there that night, and Major Spry,11 an Australian liaison officer, was sent to tell Vasey to retain enough vehicles to carry the surplus men to the Marathon beaches. When Spry

arrived most of the vehicles had been destroyed (in accordance with earlier orders from Wilson’s staff) but enough remained to carry 300. The men of the 19th Brigade Group had slept under the olive trees during the day. That night, carrying rifles, sub-machine-guns, Brens, and anti-tank rifles, they were ferried to the transport Thurland Castle, the cruiser Coventry, and the destroyers Havock, Hasty, Decoy, Waterhen and Vendetta. From a beach where there were two jetties all the 19th Brigade Group12 were taken aboard, but at the neighbouring beach where there were 2,000 sick and wounded men and technical troops, only 1,500 had been embarked by 2.30 a.m. when the last lighter departed. The troops embarked here included the remaining nurses – forty Australian from the 2/5th Australian General Hospital and forty British from the 26th General Hospital – carrying only haversacks and a blanket each.13 Altogether 5,900 troops were taken off, and some of those who remained were taken in trucks to the Marathon beaches. The Thurland Castle, on which were the nurses, most of the 2/11th Battalion, and others, was dive-bombed several times on the way to Crete, but was not hit, though several men were wounded by splinters.

The detachment sent on 23rd April to guard the left flank-2/5th Battalion, one troop 2/1st Field Regiment, and a depleted company of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion – had arrived at Megara on the 25th but, finding that no arrangements had been made to embark his force there, Lieut-Colonel King pushed on to join his own brigade, which he did at Miloi that afternoon. One company of the 2/5th had been left to cover a demolition near Delphi and followed the battalion at a distance. A man in this company wrote an account of its withdrawal:

The movement from then on was blind; we proceeded on, asking MPs for the embarkation beach; they sent us on. We arrived at Corinth and met members of the 2/6th Battalion, who sent us on. We refuelled there as we were told that we had a further 30 miles to go .... We arrived at Argos; again we were sent on. By this time we moved as controlled; we had no idea where we were going or where the battalion was in position. We arrived at Tripolis at approximately 0600 hours and were again told to go on. By this time we were in convoy of mixed troops. We met officers from other units, but they could give us no information. They did not know where they were going. We continued on the road and occasionally met MPs who sent us on. The Greeks at various villages were wonderfully kind and gave us bread, fruit and water. At approximately 1100 hours, 26th April, we arrived at a village eight miles from Kalamata ... We were told that the 2/5th Battalion was at Kalamata.

This isolated company was pursuing Allen Group – the largest single force now moving south – which had arrived at Miloi from Eleusis early on 25th April and again dispersed for the day. In the afternoon Allen

received orders, forecast the previous day, to move that night through Tripolis to Kalamata. The column moved off at 8 p.m.14 For the third consecutive night this column of 600 vehicles containing 6,000 men had a journey of 90 miles by the map – farther in fact – this time along winding mountain roads.

The march throughout was an exceedingly good one (wrote Allen afterwards15) and the M.T. drivers are to be commended for their sterling work. In the darkness, driving from dusk to daylight, using only dim lights, it was no easy task. ... 6 Aust Div Provost gave valuable assistance.

At Eleusis the group had been ordered to collect an additional seven days’ rations and plenty of oil and petrol, and did so. This enabled it to supply many British, Palestinian, Cypriot and Yugoslav troops who joined the column or were encountered at Kalamata, where the group arrived after daylight on the 26th.

On the night of the 25th–26th General Wilson left Athens to set up his headquarters at Miloi. He crossed the Corinth bridge about two hours before dawn. At that stage the outlook seemed encouraging. Two brigade groups – one New Zealand and one Australian – and some 7,000 base troops had been embarked; and the whole force, except the 4th New Zealand Brigade Group, the rearguard drawn from the 1st Armoured Brigade, and some other detachments were south of the Corinth Bridge.

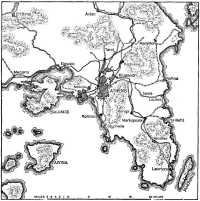

A flat sandy isthmus only three miles wide at its narrowest point links the Peloponnese with the remainder of Greece; through that isthmus had been cut a canal 70 feet in width and 26 or more in depth capable of floating ships up to 5,000 tons. Across the canal ran a bridge carrying the road and railway which passed through Corinth, which is on the coast south-west of the canal. Fear of paratroops, known to be with Field Marshal List’s army, had now led to the assembly in the Corinth area of a small patchwork force of all arms. On the north and south banks of the canal were a detachment of the 4th Hussars, a squadron of New Zealand divisional cavalry, the carriers of 22nd and 28th Battalions, Major Gordon’s16 company of the 19th New Zealand Battalion, Captain Dean’s company of the 2/6th Battalion, a section of 6th Field Company of the New Zealand Engineers, some British engineers, and a section of Bofors guns of the 122nd Battery. The New Zealand engineers assisted by Lieutenant Tyson17 of the British engineers had prepared the bridge for demolition and the ferries had been destroyed. At Corinth and on the flat ground south of the canal was the headquarters of the 4th Hussars, but the three squadrons of the regiment were dispersed along the south shore of the

Gulf of Corinth as far as Patras, 70 miles to the west, and only thirty men and four tanks remained with Colonel Lillingston. Jones’ company of the 2/6th was deployed on high ground south of the canal, overlooking its eastern end; Dean’s company on the north side. In the area were three 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns, eight 3-inch, and sixteen Bofors, the latter dispersed along the route from the canal to Argos 30 miles south.

The area had been attacked from the air at intervals during the previous four or five days, and on the evening of the 25th aircraft had silenced some anti-aircraft guns. Early the following morning the attack was resumed. About 6.30 a.m. a flight of bombers approached flying low and hit and destroyed a heavy anti-aircraft gun on the slopes south-east of the canal. About 7 a force of some 120 medium and dive bombers and fighters arrived and began a thunderous attack, the dive bombers leisurely circling to find their targets – chiefly guns and groups of vehicles – and then diving on them. Throughout the attack fighters systematically machine-gunned the area. At length the fire of the anti-aircraft guns was subdued. About 7.15 there appeared many large aircraft of a type new to the defenders. They flew in groups of three very slowly at about 300 or 400 feet. From the outer aircraft of each group dropped a descending line of men in parachutes, and from the inner machine canisters of stores. In half an hour a force variously estimated by the defenders from 800 to 1,500 men was dropped astride the canal and near Corinth.

In a few minutes the German paratroops had occupied the bridge and were rounding up prisoners, largely depot troops. Lieutenant Tyson who had helped to prepare the bridge for demolition and Captain Phillips,18 in charge of traffic movement at Corinth, fired at the charges with rifles. One of their shots is believed to have detonated a charge, and the bridge was completely destroyed.

The defenders opened fire on the paratroops and the strafing aircraft as soon as the drop began.

The German aircraft had heavily machine-gunned the positions held by Dean’s company. Two bombs dropped in one platoon area showered sand into the air so that it covered the weapons and the automatics could not be made to fire again. The paratroops who landed round this company vastly outnumbered the Australians. The platoon which had been bombed was soon overcome and it was not long before the remaining platoons (Lieutenants Richards19 and Mann20) were hard pressed. Two gliders each carrying twelve men landed in Richards’ area, but he and his men promptly killed or wounded all their occupants. However, this platoon was later overcome and the survivors captured.

An aircraft-load of paratroops floated down into the area held by Mann’s platoon. The Australians shot some of them as they came down. “Some of the enemy were firing as they descended but most were too busy

swinging about,” wrote an Australian afterwards. Mann’s platoon was soon under fire from paratroops on bare mounds of clay immediately overlooking it. Seeking cover Mann was wounded and several of his men killed.

Company headquarters were closely attacked. Several grenades were thrown into the trench which the headquarters occupied but were thrown out again by Private Coulam,21 the company clerk, until one exploded in his hand and wounded him seriously in the face. Warrant Officer Stevenson,22 the company sergeant major, fought on with great determination here, and he and others beat off the enemy for about three hours. At first this handful of men fought on hoping for the arrival of the tanks of the Hussars which Colonel Lillingston had said would cover their withdrawal if it became necessary; but at 11.45, and when no ammunition remained except a few rounds for a pistol, this group capitulated. Not till then did they learn that the bridge had been blown up and, for that reason alone, the tanks could not have come to their assistance. In the course of the action ten men of the 2/6th Battalion were killed and two officers (Lieutenants Mann and Hunter23) and eleven men wounded. Some New Zealanders in the neighbourhood fought on for another quarter of an hour and then were overcome.

No Germans landed in the area of Captain Jones’ company south of the canal but before long paratroops supported by machine-gun fire were advancing towards its position. Jones decided that there was nothing for it but to withdraw towards Argos while he could. Enemy transport aircraft evidently mistook the Australians for their own men advancing south and dropped weapons and supplies in their path. The Australians, joined by Captain Phillips and Lieutenant Tyson and an officer of the Hussars, fell back into the hills south-east of the isthmus. About 9 p.m. they were overtaken by two companies of the 26th Battalion which had been sent north to help to extricate Isthmus Force. This battalion lent vehicles to the Australians, who remained with this unit until embarkation. Meanwhile an officer of the New Zealand engineers had organised remnants of the Isthmus Force, including the New Zealand cavalry squadron, and they withdrew to Tripolis. Of the troops who had been left at Megara some 500 were intercepted by the German paratroops on their way to Corinth; some made their way back to Athens; some joined the 4th New Zealand Brigade and embarked with them; a few sailed from Megara in a caique.

The attack on Corinth was made by the regimental headquarters, two battalions, and an attached heavy-weapons company of the 2nd Parachute Rifle Regiment (Colonel Sturm). The regiment lost 63 killed, 158 wounded and 16 missing, but captured 21 officers and some 900 men of British, New Zealand and Australian units and 1,450 Greeks.

For a time Wilson’s and Freyberg’s headquarters, both now at Miloi, heard only vague reports of the action at Corinth. The first information

suggested that it was on a minor scale, and Brigadier Barrowclough was ordered merely to send two companies northwards to save the bridge (across which the Erithrai rearguard was to pass that night). Later, when it became apparent that the enemy held the canal strongly, Barrowclough was ordered to defend the pass north of Argos that night to cover the embarkation from the Argos beaches; thereafter he was to defend the road about Tripolis until the 27th–28th and then withdraw to Monemvasia. He placed the 26th Battalion in the pass north of Argos, the 24th Battalion at Tripolis to defend that vital road junction, and the 25th in defence of the western approaches to Miloi. Lee’s patchwork force at the Argos airfields was ordered to move south that night and prepare to defend the embarkation area at Monemvasia.

The parachute attack had cut the British force into two main sections: first, the main force from Argos southwards; second, the rearguard forces – the 4th New Zealand Brigade and the 1st Armoured Brigade detachment – astride the roads north-west of Athens, and the artillerymen awaiting embarkation at the Marathon beaches. Having placed infantry across the roads leading from north and west into the southern Peloponnese, Freyberg sent orders by wireless to the 4th Brigade Group that it should embark from the Athens beaches on the 27th–28th.

Wilson informed Freyberg that he (Wilson) would embark that night and Freyberg would then take command of all troops in the Peloponnese and embark himself from Monemvasia on the 28th–29th. Thus for the next two days Freyberg would be the only general officer in Greece. At this stage two brigades were cut off north of Corinth – one in action with the enemy, and one awaiting embarkation; in the Peloponnese were the 6th Brigade at Tripolis, the 16th and 17th at Kalamata. In addition there were some 8,000 ill-organised depot troops and others at Kalamata or on the way there, and 6,000 round Argos.

As the fighting force which would remain under Freyberg’s command by dawn on the 27th (if the embarkations were successfully carried out that night) would amount to approximately one division – chiefly the 4th and 6th New Zealand Brigades and what remained of the 1st Armoured Brigade – it was evidently considered appropriate that a divisional commander should take control. On the other hand, when the dispersion of Freyberg’s brigades and the presence in Greece of more than 10,000 often ill-organised base troops are taken into account, the decision on the 26th to close Group headquarters seems as precipitate as the decision on the 24th to send out Blamey and Mackay. Afterwards Freyberg considered the situation on the morning of the 27th “chaotic”. As described below, about 19,000 men were embarked on the night of the 26th–27th. On the morning of the 27th, however, one of Freyberg’s brigades was at the Marathon beaches cut off by the German force at Corinth; another was in the Peloponnese; he had not been informed that there were some 8,000 troops at Kalamata, including about 800 of his own New Zealand reinforcements, or that there were perhaps 2,000 troops round Navplion.

The embarkation of about 39,000 men was ‘a fine achievement – better than Wavell and Wilson had believed possible at the outset – but the 39,000 included only one-third of the New Zealand Division. Failure now would be a national calamity in that distant country – and deeply distressing to Australia, practically all of whose fighting units had been embarked under the protection of the two New Zealand rearguards.

It remains to record the events in the outlying areas during the 26th April. The three squadrons of the 4th Hussars which had been dispersed along the south shore of the Gulf of Corinth assembled at Patras at midday, moved out from Patras at 2 p.m. and travelled south over the mountains by way of Kalavrita.

Of the troops north of Athens and now cut off from their commander in the Peloponnese, the 1st Armoured Brigade detachment and the artillerymen at Rafina were already under orders to embark on the night of the 26th–27th. The armoured brigade detachment had been in position north of Tatoi during the day. Nothing was seen of the enemy, but a rumour – ill-founded – was heard that German troops had entered Athens in the evening, presumably from Corinth. Consequently a company of the Rangers was sent to block the roads from Athens to Kephissia and Porto Rafti. After dark the rest of the battalion and the New Zealand cavalry drove to Rafina where the rearguard company joined them later in the night

The 4th Brigade at Erithrai lay concealed, and in the early morning was not detected by scouting aircraft. At 11 a.m. a closely-spaced German column of about 100 vehicles led by tanks and motor-cars began to climb up the road from Thebes. When the tail of the column was in range, accurate fire by the Australian guns dispersed them. The German troops were seen to scatter and then board their trucks again and drive back to Thebes leaving eight vehicles on the road. About midday came the expected attack by German aircraft, the rearguard having now revealed its position, and soon after 1 o’clock German artillery began firing. An artillery duel continued all the afternoon, tanks occasionally probing forward. A tank was directly hit late in the afternoon and infantry moving towards the left flank were dispersed by machine-gun fire at 3,000 yards. During the afternoon enemy vehicles were seen streaming east along the road towards Skhimatarion. News of the paratroop landing at Corinth had arrived at 2 p.m. and the orders to embark at Porto Rafti at 7. At 9 o’clock the brigade began to embus and soon was rolling along the road at 30 miles an hour, the engineers blowing a series of craters behind it. Knowing nothing of the rumour that the Germans were in Athens, Puttick (who had sent a platoon to guard the road junction west of Eleusis) took his force through Eleusis and Athens to Porto Rafti.

As noted above three large-scale embarkations were to take place on the night of 26th–27th: from the Athens beaches, the Argos beaches, and Kalamata. The troops at the Athens beaches included Brigadier Miles’ big

artillery group at Porto Raid, and the depleted 1st Armoured Brigade at Rafina.

At Porto Rafti the single landing craft, which was the only means of loading, had first to go to Kea Island to bring in 450 men whom it had landed there on the 24th–25th. This delay was likely to prevent the program being carried out. When Brigadier Miles learnt of this, he ordered the 102nd Anti-Tank Regiment and the 2nd Royal Horse Artillery to Rafina. The gunners had brought to the beaches all the equipment that could be carried, even heavy No. 11 wireless sets, and it was a shock to learn that when the 5th Brigade had embarked on the 24th–25th the naval beach-master had ordered that all arms and equipment be discarded. Miles ordered that all the equipment which the men were carrying and also the 2-pounder guns must be taken on board. However, when the time came this was found to be impossible.24

At both Rafina and Porto Rafti the embarkation was carried out as coolly and efficiently as on the 24th. The Glengyle and Salween were loaded and some 2,720 were embarked in the cruiser Carlisle and destroyers Kingston and Kandahar, but when Glengyle sailed from Rafina at 2 a.m. 800 of the 1st Armoured Brigade, including Charrington’s headquarters, 250 of the 1/Rangers, and 117 of the 102nd were still on the beach. Major Sheppard had intended to embark his staff that night according to his orders, but at 1.30 a.m. on the 27th he learnt that the 4th New Zealand Brigade had now to be embarked from the Marathon beaches the following night. He ordered half his staff to embark, and hurried towards Athens by car to find and guide Puttick’s column, meeting Lieut-Colonel Russell25 and the 2/1st Field Ambulance moving along the Athens–Markopoulon road. By daylight Puttick’s force was lying under cover. At 9.25 a.m. on the 27th German troops entered Athens.

It had been intended to send the landing ship Glenearn to Navplion on the 26th–27th but she was bombed and disabled that evening,26 whereupon Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell took his flagship (HMS Orion) and the Australian cruiser Perth to Navplion (where another cruiser, four destroyers and two transports were assembled). He detached HMAS Stuart to Tolos.

Stuart (Captain Waller) began embarking troops at Tolos beach at 11.15 p.m., the men wading to a landing craft which ferried them to the ship. Soon Stuart reported that she was full. She transferred her troops to Orion, asked for the help of a cruiser, and returned with Perth to Tolos. Again and again the landing craft was stranded temporarily on a sand bar about 30 yards from the shore. The naval beach-master had warned Colonel Courage, the area commander, against this bar but had failed to persuade him not to use this beach. At 4 a.m. about 2,000 had been embarked and some 1,300 were still ashore. Four officers of the Australian

embarkation staff had been embarked leaving only O’Loughlin, Major MacLean and Captains Bamford and Grieve.

At Navplion the Ulster Prince, which had now been bombed and burnt out by German aircraft, obstructed the little harbour and made it impossible for destroyers to come alongside the quay. A choppy sea rendered it dangerous to embark men in small boats and, in the darkness, a number were washed overboard and drowned. Finally, at 4.30 a.m., dangerously late, the ships sailed with about 2,600, having left 1,700 ashore. Having departed so late the Slamat, carrying about 500, was still within easy range of German aircraft at dawn. She was discovered and at 7.30 a.m. was sunk. The destroyers Wryneck and Diamond picked up the few survivors.27 Later the two destroyers were themselves sunk. Only one naval officer, forty-one ratings and about eight soldiers were rescued. Of those left at Navplion 400 moved down the coast in a tank landing craft, later bombed and sunk; and 700, including the Australian Reinforcement Battalion, were sent to Tolos where they hid for the day. At intervals during the day German aircraft arrived overhead and cruised round dropping small bombs and machine-gunning at so low an altitude that the men lying in the shadow below could see the pilots and gunners clearly and could scarcely believe they themselves were not seen. The air crews were evidently trying to provoke retaliation or movement by the men below but they lay motionless.

At Kalamata from 18,000 to 20,000 troops were now assembled, about one-third being of Allen Group (the 16th and 17th Brigades and corps troops) and most of the remainder a medley of base troops, Yugoslavs and others. The survivors of the 4th Hussars and the New Zealand Reinforcement Battalion were on their way to Kalamata.

Brigadier Allen had urged upon Brigadier Parrington, who was in command of the embarkation area, that fighting men, being the most valuable, should be embarked first. Parrington issued an order late in the afternoon stating that the men were to be divided into four groups. The first included Allen’s two brigades; the second, under Colonel Lister,28 comprised all troops north-east of Kalamata; the third, under a Major Pemberton, those who had arrived by train; and the fourth, under his camp commandant, those not elsewhere included. All these were divided into parties of fifty each and each party was allotted a serial number. Allen’s force was given numbers one to 150, Lister’s 151 to 300, Pemberton’s 301 to 400. The troops were to march to the beach or quay and report to a control post there, where a ship would be allotted to them. It was essential, wrote Parrington, that “the highest standard of discipline be observed in accordance with Imperial traditions”. Allen, Savige and their staffs allotted serial numbers within their own force. Medical units came first, then artillery, engineers, infantry and so on. The men were in good

heart, though weary and disappointed; the Australian leaders resolved to ensure that their units left Greece as a disciplined force, the more so because a majority of the men at Kalamata were now officerless and disorganised and there was evident danger of a panic among them. Allen ordered the commanding officers to take “active measures to prevent troops other than Australian and British troops under the command of Allen Group from filtering on to the ships”. He ordered his provosts on the 26th to shoot any man who “fired a shot, lit a fire or panicked”. In a written order Lieut-Colonel Walker of the 2/7th said:

The C.O. directs that every effort be made to present a soldier-like show and he expects every man from private upwards to do his bit towards concluding this effort successfully. On the march, step, dressing and general discipline must be maintained. Stragglers cannot be catered for and can only be left behind.

In the evening the men began to damage or bury their kits. In the course of the 26th it was agreed in conference between Allen and Parrington that the method to be employed to destroy vehicles would be to drain oil and water and run the engines until they seized – as had been done at most beaches. Allen, however, was instructed not to destroy his vehicles until ordered by Parrington’s headquarters, in case they were needed to carry his force to yet another place of embarkation. It was decided to hand the vehicles to Parrington for use by the remaining troops; but later that night “at a most inconvenient time”, as Allen wrote later, he was ordered to destroy the vehicles, but not to use the method of running the engine$ without oil and water. Instead tyres were slashed and engines smashed with axes or hammers.

About 10 p.m. the troops saw lights out to sea, coming closer and closer to the shore. Orders were given and the lines of waiting men began to march forward, in threes and in step, carrying weapons and spare boxes of ammunition. As the head of each column neared the shore they could see the dim shapes of destroyers in the bay and an occasional light flashing on the wharf where soon two destroyers were tied up with gangways at bow and stern. The men filed quietly aboard, and, when a destroyer was loaded and cast off, those who remained sat on the wharf in their ranks and waited for the next. There is one recorded incident of leaderless troops attempting to rush a ship. A crowd from the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps which was recruited from Cypriots and Palestinians tried to press forward to the destroyer Hero, but a platoon of the 2/2nd Battalion thrust them back with rifle butts.

The behaviour of the troops was outstandingly good and orderly (wrote Savige later). The column had moved, in several heads, to the road which led to the quay. Ranks were maintained and threes were unbroken. Everybody was exhausted but the unit job was always well in hand. Not only were the troops acting splendidly, but there was an atmosphere of complete faith in their officers and NCOs. In checking passing units, to ascertain who they were, the reply always quoted their serial number. Their sense of security was so great that, on the approach of a body of troops, I would ask where their officer was. I would make myself known to him, and only thus could I obtain the identity of each unit. When they reached the quay, men stood fast in their tanks. Naval officers, who

were present at Dunkirk, expressed their surprise at all troops carrying their weapons and equipment, and spare boxes of S.A.A.

Savige received the new instruction about destroying vehicles about 9.15 p.m. The vehicles of three of his battalions-2/5th, 2/6th and 2/7th – and of the 2/2nd Field Ambulance were still on the far side of Kalamata. Savige gave Captain Gray29 the task of organising the destruction of the vehicles and arranging the transport of the drivers to the beach. About 11.30 the drivers had not arrived. Savige pointed out to Gray that he alone knew where their various rendezvous were and the routes along which they would reach them and asked him to go back and try to get them forward in time.

About 2.15 a.m. Savige found that his 2/7th, 2/8th Battalions, his engineers and field ambulance had embarked, and his 2/6th Battalion, 2/1st Field Regiment and brigade headquarters were drawn up beside a destroyer which was then berthing. The 2/5th Battalion was missing. It was found behind the solid mass of troops waiting to embark after Allen’s force, and was led forward and embarked.

It was then about 2.45, and Allen had just been informed that no more destroyers would pull in that night but that ships would return the following night. Gray and the drivers had not arrived and therefore Allen decided to leave two of his staff officers, Captains Woodhill30 and Vial, ashore to collect these men and embark them next night. Believing that all except these drivers had embarked, Allen and Savige boarded the last destroyer, but it had just swung away from the wharf when Captain Tyrrell,31 in charge of the men of 17th Brigade headquarters, called from the quay; his men were standing there in their ranks.

In fact it turned out that several other groups from Allen’s force had been left behind – a detachment of the 2/1st Field Regiment and the commanding officer, Lieut-Colonel Harlock,32 who was trying to ensure its embarkation; the Yugoslav anti-aircraft gunners; and some others. The total number embarked is uncertain but certainly exceeded 8,000 – by far the largest number taken off one beach on a single night.33

One man who waited in vain that night described the scene:

We just came, in straggling dozens and scores, to a line of figures in the darkness, all facing to the left. We tried to move around them, and saw that they were in a queue. It was quite unreckoned for, and shocking. We got to the end and there, with the light coming off the water, we could see it and it was up to twenty men deep and two hundred yards long, a great packed rectangle of thousands of men. They stood very still, not talking, not smoking; there was an occasional cough, and over the top of the block there played a continual little motion as men raised themselves off their heels to look to the front ...34

On the 27th Admiral Pridham-Wippell was near the end of his resources. Suda Bay was crowded with ships packed with troops. All available transports were filled and it was likely that any future embarkations must be carried out by naval vessels. He decided to send his laden transports Glengyle, Salween, Khedive Ismail, Dilwarra, City of London, and Costa Rica – not to Crete but to Alexandria, escorted by one force of cruisers and destroyers and protected from the north-westward by another. Soon after dawn the air raid alarm sounded in the ships of the Kalamata convoy.

The men came up on to the deck with a spontaneous rush (said one of them later) and ran to pick gun positions. It was one of the finest things I’ve seen – the way these worn-out men sprang to the defence of the ship.

On the City of London, for example, eighty-four Vickers, Brens and Hotchkiss machine-guns and anti-tank rifles were mounted and fired at the attacking aircraft. A near miss brought an avalanche of water over the forecastle of Costa Rica, from whose decks every Vickers gun and Bren on board was in action thickening the fire from the cruiser and destroyers. There were further attacks during the morning but without effect, though seven enemy aircraft were shot down. At 2.40 p.m., however, an enemy aircraft was seen, too late, gliding out of the sun. Its bomb struck the water 7 or 8 feet from the Costa Rica, whose engines stopped immediately. At 3 o’clock water was coming in fast through gaps in the plates on the port side. The troops were ordered to fall in. There was room for some of the 2,500 on deck, but most lined the alleyways or stood along the lower deck in darkness, silently on parade. The destroyer Defender came alongside. At this stage four men of the ship’s crew came on deck, threw a few rafts overboard and shouted “Every man for himself”, whereupon about twenty soldiers left the ranks and jumped overboard. This delayed the destroyer Hero which was coming along the port side and whose crew had to pull these men from the water. The Costa Rica was rising and falling 18 or 20 feet in the water and men had to swing down the side on ropes and jump for the deck of the Defender. When she was filled the destroyer Hereward came alongside. Among the last to jump on to her were those manning machine-guns, who had been ordered to remain in case the aircraft attacked again. Finally, when Costa Rica was listing so steeply that a man could step off the lower bridge on to the deck of a

destroyer, the Hero replaced the Hereward and the Dutch ship’s officers and about twenty soldiers who remained jumped on to her deck. The trans-shipment took forty-five minutes. The troops aboard included the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion, the 2/7th Battalion, part of the 2/8th, and a company of the 2/1st.

Thus, on the night of the 26th–27th about 19,000 troops embarked. Of the transports employed two had been sunk by German aircraft before they were out of range – the Slamat with a loss of nearly all on board, the Costa Rica without the loss of a man. Two destroyers had been sunk. It was not a heavy price for such an achievement. There remained in Greece the 4th Brigade Group and part of the armoured brigade near the Athens beaches, about 2,500 men at the Argos beaches, the 6th Brigade Group at Tripolis, several units and detachments at Monemvasia, and more than 8,000 men at Kalamata.

While the 4th New Zealand Brigade was moving to a defensive position about 500 yards east of Markopoulon on the Athens–Porto Rafti road, it was detected about 11 a.m. by some twenty-three German aircraft and severely machine-gunned. This fire exploded a shell in an ammunition waggon of the 2/3rd Field Regiment, which again produced other explosions and soon shells were bursting everywhere, vehicles burning, and the ripe crops in the fields and the trees in the pine woods blazing fiercely. Nine guns of the 2/3rd or the anti-tank battery attached to it were destroyed, and six artillerymen and a larger number of New Zealand infantrymen were killed by the explosions; about 30 were killed or wounded in the 20th Battalion. Into the blazing woods squadrons of German aircraft poured bombs and machine-gun fire at intervals. By 1 p.m., however, the 18th and 20th Battalions were in their intended position forward, the 19th in reserve and the 2/3rd Field Regiment in support, with some guns well forward in an anti-tank role.

In Markopoulon the Greek villagers crowded at their doors to watch the troops move up to the line. Though they knew the campaign had been lost and that soon Germans and not New Zealanders would be marching through the village street, and although some stood glum and silent, others threw roses to the marching men and strewed them on the road at their feet. Women and girls ran forward with cups of water and old men gave the thumbs-up sign. The woods and the crops were still blazing and a cloud of smoke hung over the countryside.

About 3 p.m. a column of 50 to 100 German vehicles, most of them light tanks, were seen moving into Markopoulon. The guns did not fire on the village, but whenever German tanks emerged from it they were met by a heavy concentration of fire from guns and mortars, and throughout the afternoon the tanks remained in the sanctuary the village offered. Many of the German vehicles passed across the front towards the little port of Loutsa, where they perhaps expected to find the main force. The attack, expected hourly, never came, though there was more strafing from the air. At 6 o’clock the brigade began destroying its remaining trucks, and at 8.45 the guns. At 9 o’clock the men in the forward positions marched back into a perimeter which the reserve battalion, the 19th, had formed about 1,000 yards from the beach. The troops were embarked from Porto Rafti in the cruiser Ajax (2,500 men), and destroyers Kimberley (700) and Kingston (640).

It will be recalled that there remained at Rafina, 10 miles to the north, Brigadier Charrington and about 800 of the armoured brigade. All guns had been destroyed. During the 27th this force had taken up a concealed defensive position round the beach, the Rangers, about 250 strong, on the left, the anti-tank gunners and New Zealand cavalry regiment in the centre and on the right. Early in the day German aircraft bombed the wrecked vehicles on the hills north of Rafina and the village itself, and flew low over the hidden troops but without seeing them. In the morning a party of the anti-tank regiment under Lieutenant Pumphrey,35 who knew

classical Greek, took possession of a caique in the harbour; if no ship arrived at Rafina that night – and none was expected – the caique would be useful.36 About 250 men were allotted to her and at 6 o’clock Charring-ton and the remaining 600 began to move towards Porto Rafti, where it was known that an embarkation would take place that night.37 Later he decided that the enemy between Rafina and Porto Rafti was too strong; and meeting liaison officers from the 4th Brigade who said that a ship would be at Rafina that night, he turned back to rejoin the 250 in the caique. In the meantime the owner of the caique – a pro-German the villagers declared – had disappeared, having first ensured that his ship’s auxiliary engine could not be started. Nevertheless the caique was loaded with men and was preparing to set off under sail when at 1.15 a.m. the dim shape of a destroyer appeared off shore. It was the Havock whose captain, Lieut-Commander Watkins,38 had learnt that men were left at Rafina and had steamed from Porto Rafti to pick them up. Brigadier Charrington and the main body of troops had now returned, and by 4 a.m. the 800 were aboard the destroyer and on the way to Crete.

There had been no embarkation from the beaches of the Peloponnese that night (27th–28th April). The transports used on the 26th–27th were then at Alexandria; four cruisers and twelve destroyers had been engaged escorting or protecting them.

Meanwhile at Miloi and Tripolis the 6th Brigade saw no signs of the enemy except in the air. Freyberg ordered Barrowclough to hold till dark and then move back to Monemvasia as fast as he could. Consequently at midday he began thinning out his troops. The 26th Battalion moved south under air attack, which though frequent, caused only three casualties. The remainder of the brigade, with Freyberg’s battle headquarters, moved at night, and by daylight on the 28th had travelled 120 miles and was concealed within the defensive line at Monemvasia.

At Monemvasia Lee already had his force in position; and Colonel Clifton and the New Zealand engineers had placed in the road depth-charges from a Greek destroyer which was aground in the harbour. The rear party of Group headquarters, including Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman, was established near by, and Colonels Quilliam39 and Blunt40 (the military attaché at Athens) had collected the local caiques in case of need. The inhabitants had been induced to go to villages in the hills so that the town would appear to scouting aircraft to be deserted.41

At the Argos beaches – Navplion and Tolos – there were now more than 2,000 troops, many without rations, and the number was increasing as parties of stragglers arrived. Enemy aircraft were overhead during the day machine-gunning and bombing. A rearguard force was organised from the Australian Reinforcement Battalion and some 200 men of the 3rd Royal Tanks, the only fighting detachments in the area. Destroyers were expected on the night of the 27th–28th but none arrived, and at 3 a.m. the troops who had assembled ready to embark dispersed to spend another day in hiding. At 4 a.m. Major O’Loughlin gave Major MacLean 150,000 drachmae (about £250) from a fund of 250,000 issued at Servia a fortnight earlier for hire of donkeys, and sent him and a naval officer along the coast to collect small boats to speed the embarkation on the next night, and caiques in case no ships arrived. Sixteen boats were found but when the Greek owners learnt that the Germans were near they were unwilling to provide them at any price.

At Kalamata about 6,000 out of more than 8,000 men were unarmed and largely leaderless base troops, Palestinian and Cypriot labourers of the pioneer corps, Greeks, Yugoslavs, and Lascar seamen from ships sunk off Greece. The only organised fighting troops were the New Zealand Reinforcement Battalion (about 800 men under Major MacDuff42), a force of 380 Australians (including about 70 of the 2/1st Field Regiment and the transport detachments of the battalions of the 17th Brigade, all under Lieut-Colonel Harlock43), and about 300 men of the squadrons of the 4th Hussars who arrived that day. At dusk on the 27th, as the troops were forming up to march to the beach and the quay again, about twenty-five bombers came over and, making their runs at no more than 500 feet, for an hour dropped sticks of bombs across the already battered town. When they had gone the men patiently formed up again and stood waiting for the ships as they had done the night before. But no ships appeared off Kalamata that night, and at 1 a.m. the troops dispersed to their lying-up places among the trees. The 4th Hussars were given the task of providing an outer defence for Kalamata; the New Zealand battalion was to be in position at 7.30 p.m. to cover the hoped-for embarkation on the night of the 28th.

Of the groups which remained in Greece on the 28th only one – the New Zealand brigade at Monemvasia – was a substantial, armed and disciplined fighting force (but without artillery weapons). The plan was to embark it in a cruiser and four destroyers that night, to send two cruisers and six destroyers to take off an estimated 7,000 men at Kalamata (actually there were more than that) and to send three sloops to Kithera Island whither some 800 had been transported in caiques and a landing craft.

That night the men on Kithera were ferried to the sloops in the landing craft, and then taken to Suda Bay, the sloop Hyacinth towing the landing craft. Embarkation went smoothly at Monemvasia. The destroyers Isis and Griffin arrived at 10.30 p.m. on the 28th and the cruiser Ajax and destroyers Havock and Hotspur about 1 a.m. The troops, having destroyed their vehicles, were ferried out to them in barges and local fishing boats. By 4 a.m. on the 29th the whole force including General Freyberg and Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman were embarked.

Meanwhile the Germans had been thrusting deeper into the Peloponnese. On the morning of the 28th reports had arrived that German parachute troops were near Navplion; whereupon the senior officer, Colonel Courage, announced that officers and men were free to make for the hills, and that he himself was doing so.

The group at the Tolos beach near by included a rearguard of the “Australian Composite Battalion” organised from troops in the Athens area. It had arrived at Argos before dawn on 26th April. It received an order to move to Kalamata prepared to fight a rearguard action. While in the Tripolis Pass it had been attacked by bombers and fighters, the road was made impassable, and one half of the battalion, under Major J. Miller and Captain D. R. Jackson, took up positions near Tripolis. There Jackson received orders from Brigadier Lee to cover the embarkations at Navplion and Tolos – the Argos beaches. The half-battalion, about 130 strong, took up a position covering Tolos beach, Navplion having then been abandoned. On the morning of the 28th, when all officers of the force round Navplion were instructed that those who wished to do so might break away, Miller and Jackson elected to fight on in an attempt to deny the beach to the enemy for another night. Jackson’s group was deployed left of the road to Navplion and Miller’s right of it. Early in the afternoon they engaged a column of Germans in trucks and captured carriers. After a fight lasting some three hours the little Australian force was overcome.

During the afternoon news was spreading among the troops round the beach that the force had surrendered. Most of the men did surrender, but in the confusion many parties from Tolos escaped, some in boats seized on the spot, some walking south along the coast until they found serviceable caiques.44

At Kalamata Parrington had organised his motley assemblage of troops into four groups ready for embarkation that night. First to embark were

to be the wounded and their stretcher-bearers; next Pemberton Force, 1,400 men chiefly of the 80th Base Sub-Area; then Harlock Force, now comprising the Australians and New Zealanders; then Lister Force – some 2,400 British troops chiefly from depot units, 100 Indian mule drivers, about 2,000 Palestinian and Cypriot labourers; and lastly perhaps 2,000 other labourers, Yugoslavs and Lascars.

About 4 o’clock in the afternoon the Hussars patrolling north of Kalamata reported that they had been 25 miles from the port and made no contact with the enemy. Two hours later, however, as the troops were moving down to the beach to be ready to embark, German troops, having overrun the Hussars, drove into the town and to the quay, and captured the naval beach-master. Furious firing broke out round the quay. Harlock and other officers hurried parties of troops to the scene. MacDuff’s New Zealand battalion fixed bayonets and charged towards the quay.

The fighting that followed was extremely confused. Only 70 of the 400 Australians under the command of Captain Gray could be used in this attack because of shortage of weapons. Gray divided these into two platoons, one of which joined the New Zealanders, while Gray led the other in an attack along the sea front. A concerted attack began about 8.15 p.m. By 9.30 the quay had been recaptured, two field guns which the Germans had established there had been taken, and about 100 of the enemy had been made prisoners.

The attacking German force consisted of two companies with two field guns. It was drawn from the 5th Armoured Division. The Germans lost 41 killed and “about 60 wounded”.

While this fighting was in progress the cruisers Perth and Phoebe and the destroyers Nubian, Defender, Hero, Hereward, Decoy and Hasty were approaching Kalamata. Hero, which was sent on ahead, arrived off Kalamata at 8.45 p.m., and received a signal, flashed from the harbour, that the Germans were in the town. Hero closed the beach and landed her first lieutenant. She then wirelessed Perth, whose captain, Bowyer-Smyth,45 was senior officer of the squadron, that the Germans were in the town but British troops were to the south-east of it. At 9.10 p.m. Perth and the rest of the force, then 10 miles from Kalamata, saw tracer fire and a big explosion. At 9.30 Hero’s first lieutenant reported that the beach was suitable for evacuation, and Hero signalled Perth accordingly, but because of a wireless defect this message did not reach Perth until 10.11 p.m. Meanwhile, acting on the earlier signal, Bowyer-Smyth, at 9.29 p.m., turned his force about and retired at 28 knots, ordering Hero to rejoin. By the time he received Hero’s second signal Bowyer-Smyth was well on his way south and decided to continue retirement. Hero, joined later by the destroyers Kandahar, Kimberley and Kingston, remained until about 3 a.m., when they sailed, having taken on board some of the wounded and about 300 others.

As soon as the destroyers had gone Parrington assembled all troops on the beach, summoned the officers and told them that the navy could do no more because of enemy naval action and that he proposed to send a message to the enemy that he would surrender at daybreak. Those who did not wish to surrender should be out of the area by 5 a.m., when it would be becoming light. Some of Parrington’s listeners received the impression that commanding officers should consider it their duty to remain. Colonel Harlock, in command of the Australians and New Zealanders, said that he would remain. Parrington then sent an officer with a German prisoner who could speak English to the German headquarters to say that no resistance would be offered after 5.30 a.m.

That night there were probably 8,000 troops at Kalamata (not all British), perhaps 2,000 at Navplion and Tolos. No plan was made to embark the men at Navplion where it might be expected that the German advance-guard would arrive (as it did) that day. At Kalamata, however, the planned embarkation, if it had not been upset by the alarm caused by the arrival of a German detachment which the defending force dealt with, might well have removed most of those who remained.

After the 28th–29th Admiral Cunningham instructed Admiral Pridham-Wippell to attempt to bring off troops who might be straggling along the coast south of Kalamata. The destroyers Isis, Hero and Kimberley picked up 33 that night and 202 the next, when Hotspur and Havock also embarked 700 who had collected on the island of Milos. Among the Australians picked up south of Kalamata were Captains Woodhill and Vial, mentioned above, and Lieutenant Sweet46 with a party of five of the 2/5th Battalion.47

There remained in Greece one organised Australian unit – a detachment of the 2/5th General Hospital commanded by Major Brooke Moore48 and including six other officers and 150 other ranks. It was charged with the care of 112 patients, all too ill to be moved, and other casualties who might arrive. On the morning of the 27th the Germans came and placed a guard over the hospital area, which was at Kephissia, near Athens, but the Australians were allowed to continue their work unhindered. On 1st May Germans took the hospital’s portable X-ray machine to replace one of their own, which had broken down, and next day took some of the hospital’s reserve of rations.

On the 7th, on German orders, the hospital began to move to Kokkinia, a suburb of Athens; on the 10th, the day after the completion of the move, 29 wounded, with 9 New Zealand medical and 4 dental officers arrived from the south. On the 13th 50 patients arrived from the detachment of the 26th British General Hospital which had remained at Kephissia, and in the next few days 140 more, accompanied by rations and equipment. The British hospital was thereupon disbanded by the Germans, most of its medical staff being distributed to prison camps in the Peloponnese; but some medical officers went to the 2/5th Hospital. By the 20th, the strength of the 2/5th had risen to 28 officers and 188 other ranks, and in their care were more than 600 patients.

Late in May casualties began to arrive from Crete, and within a fortnight 1,500 patients had been admitted. Most of them had been severely wounded, many had received no medical attention since their first treatment in the field and were virtually without clothing. By the end of the month the hospital was overflowing and a hospital annexe for walking wounded had been opened. There the accommodation was poor and draughty, the sanitation primitive. Early in June the number of patients had increased to 1,590, and from time to time batches were sent to Salonika on the way to Germany Gradually the numbers of patients dwindled. The convalescent section was closed in September and the whole hospital in December, when the staff of the unit was moved to Germany. The hospital had treated 3,026 military and 50 civilian patients. The Germans had been generally friendly and helpful, and, when stocks of dressings and drugs had dwindled, had replenished them.49

The losses of the German Twelfth Army in Greece were 1,160 killed, 3,755 wounded and 345 missing; these figures were announced by Hitler soon after the campaign ended.

The total strengths of the British, Australian and New Zealand contingents in Greece were: British Army 21,880, Palestinians and Cypriots

4,670, R.A.F. 2,217, Australian 17,125, New Zealand 16,720. So far as they can be ascertained, the losses suffered by the contingents were:50

| Killed | Wounded | Prisoners | |

| British | 146 | 87 | 6,480 |

| R.A.F | 110 | 45 | 28 |

| Australian | 320 | 494 | 2,030 |

| New Zealand | 291 | 599 | 1,614 |

| Palestinian and Cypriot | 36 | 25 | 3,806 |

After the Anzac Corps withdrew from the Thermopylae–Brallos position the German columns slowly progressed along the cratered roads to Athens where, as we have seen, the first troops to arrive came from Corinth on the morning of the 27th. The “Adolf Hitler” Division at Yannina with an open road before it did not begin to advance south to outflank the Anzac rearguard position until the 26th. (The 73rd Division remained in Epirus to police the surrender of the Greeks.) The “Adolf Hitler” reached Patras on the 27th, and remained in that area until the organised embarkation was over. The fast-moving 5th Armoured Division,

however, pushed into the Peloponnese on the 28th, reaching Argos, Navplion and Tripolis that day and Kalamata that night.

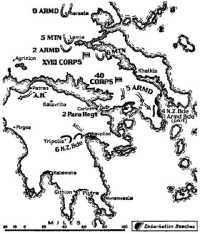

On the 28th April ten German divisions were in Greece and they were deployed thus:

| Peloponnese | 5th Armoured, “Adolf Hitler” |

| Athens–Lamia | 2nd Armoured, 5th and 6th Mountain |

| Thessaly | 9th Armoured |

| Grevena–Yannina | 73rd |

| Katerini | 72nd |

| Salonika | 50th |

| Eastern Macedonia and the Aegean | 164th |

Three infantry divisions (50th, 72nd and 164th), two mountain (5th and 6th) and the 2nd Armoured had fought the Greeks in eastern Macedonia. Two infantry divisions (“Adolf Hitler” and 72nd), two mountain divisions (5th and 6th) and three armoured divisions (9th, 2nd and 5th) had been engaged against the Anzac Corps. Three divisions of Field Marshal List’s Twelfth Army (46th, 76th and 198th) were still relatively idle in Bulgaria and southern Yugoslavia when the fighting in Greece ended. Thus, if a prolonged resistance had been offered on the Thermopylae line, List, without calling for help from the three armoured, two mountain and eight infantry divisions of the Second Army in central and northern Yugoslavia, could have deployed against the Anzac Corps, three armoured, two mountain, and eight infantry divisions.