Chapter 8: Escapes to Crete and Turkey

AFTER destroyers had embarked the last parties, and the Germans had rounded up their prisoners – chiefly at Kalamata and Navplion – there were many British soldiers at large in Greece, some hundreds of whom contrived to escape to Turkey and elsewhere in the following months and eventually to rejoin their units. It is within the scope of this narrative to record the fate only of the larger Australian parties and of some individuals who were typical of other determined and enterprising escapers.

The largest such groups of Australians belonged to Lieut-Colonel Chilton’s 2/2nd Battalion, most of which was cut off in the Pinios Gorge. During the night of the 18th–19th (ten days before the last large embarkation) that battalion was thrust into the hills above Tempe. Next day many of its scattered parties collected in the foothills of Mount Ossa; at the end of that day Major Cullen,1 of Chilton’s headquarters company, had twelve officers and 140 others, including some of the 21st New Zealand Battalion, under his command. Chilton, however, and the headquarters men who had been with him at dusk the previous day were not among them. Cullen marched his force to the coast near Karitsa hoping to find a naval vessel, but, after two days, the group, by mutual agreement, broke into small parties; the villages were small places of only from six to twenty houses and unable to provide food for large bodies of troops. Cullen had distributed some 200,000 drachmae belonging to the regimental funds among the officers in charge of the small parties and they were thus able to buy food, particularly sheep and pigs – though generally the villagers refused to accept payment.

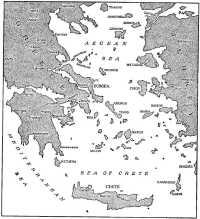

Most of these men went south, and on 25th April the majority, having reassembled, were ferried by Greeks to Skiathos, whence in stages they sailed in luggers to Chios. Here the people were most hospitable; the women provided a free meal in the public school, and a Greek shipowner, Mr D. G. Limos, lent Cullen and Captain Trousdale2 of the 21st New Zealand Battalion 150,000 drachmae. The Turkish coast was only 10 miles away but, fearing that they would be interned in Turkey, they arranged to join a 150-ton vessel which was leaving for Crete carrying 400 Greek officers and men. On the night of 29th April the ship sailed from Chios amid the cheers of a crowd on the waterfront. It went from island to island, and two days later met a vessel containing another large party including Captain Jackson. Jackson had been captured after the rearguard action at Tolos, mentioned above, but had escaped and reached the coast. There he and others seized a steamer at pistol point, and eventually collected a party of about 280, including about 100 Australians, 100

Greeks, and some Communists and Jews. On 4th May both ships sailed for Heraklion in Crete where the passengers landed on 5th May.

Because there was no room for them in the ship, a party of 97, later increased to 133, had been left behind at Chios, under Captain King, of the 2/2nd. The Greek Commandant, the Harbour Master and the Mayor (who had taken over responsibility for the British troops who remained) regretfully told King that there was not enough oil on the island to take a caique to Crete, but they could arrange a caique to Turkey. After making further efforts to obtain a vessel that could make a longer voyage they sailed, with Mr Noel Rees, British Vice-Consul at Chios, to Cesme in Turkey where, after a little hesitation, they were warmly welcomed. With the devoted help of Rees, Colonel Hughes3 – an Australian – and others, they obtained a Greek yacht, the Kalamara, and in it King’s party and another ten officers and men from Mytilene led by Lieutenant Harkness4 sailed through the Italian Dodecanese islands and arrived in Cyprus on the 7th May. Hughes had spent many years in Turkey as an officer of the Imperial War Graves Commission, was persona grata with the Turks and well qualified to take part in the delicate task of organising the escape of prisoners through this neutral, though friendly, country.

Meanwhile Colonel Chilton and three men who were with him in the Pinios Gorge at first attempted to reach the 2/3rd Battalion but, having concluded that it had withdrawn, they began marching south-west. They passed through Sikourion and, farther south, came upon abandoned Australian and New Zealand lorries bogged in the plain east of Larisa and took tins of bully beef from them. Chilton’s small party was joined by other groups. Tramping chiefly by night, avoiding the roads along which German convoys were streaming, and guided by devoted Greeks, they reached Euboea where they were joined on 7th May by Captains Buckley, Green5 and Brock,6 Lieutenant Bosgard7, and five others who had also tried to walk back to their own force south of Lamia, and eventually, after days of arduous trudging in the hills, had reached this island. On the 8th May, they obtained a boat and sailed to Skyros by way of Skopelos. There they met a party of sixteen men, including Sergeant Peirce of their own battalion, who had news of the escape of Cullen’s large party.

Peirce’s party, after much wandering, had been landed on Skyros by a . Greek sea captain on the 7th May. In his diary Peirce wrote an account, typical of many, of the kind of warm welcome which Greek peasants and fisherfolk gave to the fugitives:

Eventually about 5 p.m. (on the 25th April) we arrived at Zagari amidst much weeping by the fairer sex and were taken to a house where we were more or less put on exhibition. Most of the people who visited us left something for us to eat and within a short while we had each partaken of three eggs, half a glass of goat’s milk with plenty of bread and cheese. ... Blankets arrived and soon we adorned the floor in slumber again. At 10 p.m. we were awakened for another feed consisting of three more eggs each, with bread, olives and a sip of milk. We were then told to pack up and we were taken to another house about a mile away where an old codger thought he could speak English and we had some fun with him till another meal arrived. Two low tables were placed together and cloths put on, then dishes of vegetables, mostly potato, two dishes of fried eggs, one of olives and one of small fish like sardines.

On the 10th this party was awakened by a Greek soldier who was with them and told that a boatload of Germans had landed. The “Germans” were Colonel Chilton and his group, now sixteen strong. After some

narrow escapes from detection by German aircraft, since the enemy now occupied Chios and Mytilene, the combined party reached the Turkish coast near Smyrna.

On the way down to Smyrna we met two elderly Turkish colonels (wrote Chilton later). Both had been wounded by Australians during the first war, and they were very proud of it. They said they had squarely beaten us at Gallipoli, even though we made up for it later. They appeared to have the greatest admiration for the Australians of those days – in fact, they echoed sentiments I have heard expressed by our chaps about the Turk. The first man we saw at Smyrna was Colonel Hughes. What a joy he was – and imagine our surprise at being greeted by such a typical Australian. We were quartered in the barracks, but he had laid on everything – hot baths, haircuts, underclothing, food, beer, cigarettes, sweets and goodness knows what else. We also learned for the first time what had been happening in the world. We were delighted to know that Tobruk was holding out.

Sergeant Tanner and another group of eighteen men of the 2/2nd were already in Hughes’ care at Smyrna. In civilian clothes, and with instructions to tell anyone who asked questions that they were “English civilian engineers”, they all went by train to Alexandretta and thence by Norwegian tanker to Port Said where they arrived on 24th May. On this ship, the Alcides (7,634 tons) there were some 250 refugees, including 66 Norwegians who had escaped by way of Russia. It was not until he reached Gaza that Chilton learnt the answer to the question that had worried him from the time that his battalion had been forced back by German tanks whether his battalion had delayed the enemy long enough to enable the remainder of the force to get through Larisa safely.

Corporal Irvine8 of the 2/2nd Battalion with two other men of his unit and one of the 21st New Zealand, after having failed to obtain a boat, decided to walk to Turkey by way of Salonika, but, after two days, met a Greek who offered to obtain them a passage to one of the islands. On the 11th May they were taken to Skiathos and thence to Skopelos. There they, found it difficult to obtain a boat since “the islands were constantly patrolled by sea and air, oil and benzine were unprocurable, and all serviceable boats were commandeered to take Germans to Crete”. Eventually a friendly Greek who had been in touch with the British consuls in Greece helped them to obtain a passage to Cesme in Turkey where they arrived on 2nd August and whence, after ten days in quarantine, they were sent to Syria.

Numbers of men taken prisoner in the Peloponnese escaped from prison camps, from trains or from columns of marching prisoners farther north. Such an escape was made by Warrant-Officer Boulter,9 captured at Kalamata on 29th April. Next day the prisoners were taken by train to a camp at Corinth where, he was told, about 10,000 British prisoners were assembled, including 350 officers. There were also 4,000 to 5,000 Italians who had been captured by the Greeks, released, and rounded up again

by the Germans. Sanitation was bad and there was much dysentery. While at Corinth the prisoners watched aircraft taking off for Crete and returning bullet-riddled or with broken wings. On 5th June began a move of all prisoners to Germany. Because railway bridges had been destroyed the prisoners were marched to Lamia.

Boulter escaped on 7th June by jumping into some low scrub beside the road and lying there until dark. That evening he obtained clothing from a Greek and for some days worked in the fields in return for food and shelter. Thence he was sent to a remote and self-contained mountain village on Mount Oiti near Lamia where he was joined by two other Australians, a British pilot, and a Pole. They decided to make their way to Euboea and thence from island to island to Turkey. They left the friendly villagers, crossed the railway and main road, climbed the Kallidromon mountains and reached the coast where, on 22nd June, a fisherman ferried them to Euboea. Here, among Greeks they listened to the BBC broadcasting the news that Germany had invaded Russia. The Greeks made the fugitives so comfortable that all but Boulter decided to remain where they were. He walked through the hills to the east coast of Euboea and then along it seeking in vain for a passage. He could now speak “quite a little Greek”, and he eventually reached a monastery, where (as always at the monasteries) the priests treated the fugitive with great sympathy, and the bishop arranged with a fisherman to take him to Skyros, first stage in the escape of many Allied soldiers. He walked across the island to Skyros town, and there met a Greek who had already been paid by the Consul at Smyrna for ferrying escapers thither. They reached Smyrna on 25th July after three days at sea, and sailed to Haifa on a Greek tramp about ten days later.

Gunner Barnes,10 2/1st Field Regiment, was taken prisoner at Kalamata on 30th April, jumped from a train 80 miles north of Salonika, and wandered through northern Greece. He was helped by Greeks for about six weeks, when he sailed with Greeks from the Mount Athos peninsula to Turkey, and thence rejoined his unit.

Fugitives were still at large in 1942 when the resistance movement in Greece had developed in strength. Lieutenant Derbyshire11 of the 2/2nd Battalion escaped from a prison camp near Athens with three other officers. At length they separated, Derbyshire establishing himself in Athens where he met Greeks who were active in the resistance movement, and he took part in sabotage exploits. Like other fugitives at large in Athens, he saw and suffered the famine that followed the German-Italian occupation. Long afterwards when commanding a forward company at Dagua in New Guinea he said:

The peasants did not feel the pinch as much as the people in the cities where the poorer classes lived in dreadful poverty. Few had work and, because of inflation, those who did received about enough in a month to get enough food for a day. Men,

women and little children starved to death and died in the streets. Little kids of three or four, with old faces, fought in the gutters with the few stray dogs left for small scraps of food or bone. For meat we used horses, donkeys, dogs and cats and all kinds of shell-fish.

In the winter of 1942 Derbyshire joined a party of ten Britons and Greeks who had arranged to embark in a caique on the east coast of Euboea. After five days of walking and climbing they joined the caique and crossed to Turkey, and thence, with the help of the Consulate-General, travelled by railway to Syria.

The experiences of only some Australians who escaped have been described. Other Australian, New Zealand and British soldiers had equally exacting journeys and exhibited similar fortitude. A number of Australian officers and men who escaped survived to hold important posts or give long regimental service. For example, in 1945, Chilton was commanding the 18th Brigade in Borneo, Cullen the 2/1st Battalion in New Guinea, Green the 2/11th, Buckley the 2/1st Pioneer, Jackson the 2/28th; Miller died of scrub typhus in New Guinea in 1942 after leading the 2/31st Battalion through the Owen Stanleys campaign.