Chapter 10: The Problem of Crete

THERE were good reasons why the Germans should attempt to advance southward through the eastern Mediterranean and occupy Crete. It was desirable for them to rob their enemy of potential air bases only 700 miles from the Rumanian oilfields, and by so doing gain for themselves bases which lay only 250 miles from North Africa, and from which, as from Rhodes and the Dodecanese, they could harass British shipping. To attempt a purely seaborne invasion of Crete would be hazardous in view of the unreliability of the Italian Navy; however, the German Army possessed a large force of paratroops and had already used them with success in Holland and at Corinth. If these could seize one or more of the Cretan airfields, other troops might be landed from the air, and perhaps still more troops, with heavier equipment, be ferried in small ships from southern Greece.

In March the defence of Crete against heavy airborne attack had been exercising the minds of leaders and staffs in Cairo – as in London. During April, however, other demands had been pressing upon the British Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East, and it is impossible to appreciate their problems without knowledge of the calamitous events which had been occurring in other areas.

During the campaign in Greece an Axis army had been rapidly advancing through Cyrenaica. It was the threat offered on this western flank that led to the decision not to send the 7th Australian Division and the Polish Brigade to Greece but to retain them to reinforce the army in North Africa. There, in the early days of April, the 2nd Armoured Division and the 9th Australian Division had been thrust back.1 Three British generals, including O’Connor, had been captured. By 11th April the 9th Australian Division, a brigade of the 7th, and the 3rd Armoured Brigade had been isolated in Tobruk. On the 13th, German and Italian forces attacked Tobruk but were repulsed; farther east, they took Salum and Halfaya Pass. At these points the advance was halted, but the British forces which were holding at Tobruk and east of the Egyptian frontier were perilously weak.

It was fortunate that, early in April, the Italian army in Abyssinia was decisively beaten, and, as a result, General Wavell would soon be able to bring reinforcements northward from that theatre. On the other hand disturbing events were occurring in Iraq on his remote eastern flank – events which in their ultimate effect were to govern the future operations of a large part of the Australian force.

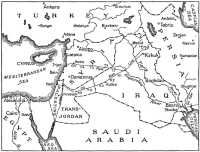

From the beginning of the war the British leaders had to take into account the possibility that the nationalist leaders in Iraq would seize the

chance to expel the British garrison, which had been reduced to a shadow – an air force school and depot equipped with training aircraft and a few troops to guard them. Nevertheless, it was vital to Britain that Iraq should remain under the control either of rulers well-disposed to Britain, or failing that, of a British army. The oil from Persia was piped to Basra in Iraq, the oil from Iraq to Haifa. It would have been calamitous if these supplies had been cut off; and, if Iraq was in the hands of a pro-German clique, the Germans might be tempted to march through Turkey to Iraq and establish themselves and their submarines and aircraft on the shores of the Indian Ocean.

The anti-British movement in Iraq was headed by Rashid Ali, who had been Prime Minister from April 1940 until January 1941. He was strongly supported by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, a vigorous leader of the Arab Nationalist movement and an enemy of Britain. The Grand Mufti in September had approached the German Government with a plan for stirring up anti-British movements in Iraq, Syria and Transjordan, but the German Government had then been unenthusiastic.

Because Iraq had virtual independence and possessed an army of more than 50,000 men – trained and equipped by Britain and commanded by Iraqi officers who had passed through the British staff college – Arab nationalists throughout the Middle East looked to Baghdad to raise their banner at an opportune moment.2 In January the Germans began to

reconsider the Grand Mufti’s proposal and to seek means of trickling arms into Iraq. Early in April Rashid Ali became Prime Minister, and the Amir Abdul Illah, uncle of the infant King and a supporter of British influence, who was acting as Regent, having learnt that the new Prime Minister intended to arrest him, fled to Basra and thence to Transjordan.

Thereupon, the British Government decided to land a force at Basra, calling upon its treaty right to pass limited numbers of troops through Iraq. A brigade group of the 10th Indian Division which was then embarking at Karachi for Malaya was diverted to Basra where it landed without incident on 18th April. Responsibility for control of the force in Iraq was then transferred to the Commander-in-Chief in India, who, since January 1941, had been General Sir Claude Auchinleck.3

The new Iraq Government declared that no more British troops must enter Iraq until the brigade at Basra had moved on. On 28th April, however, the British force at Basra was slightly reinforced. The following day two infantry brigades of the Iraqi army supported by armoured cars and

artillery – twelve 18-pounder guns and some howitzers – surrounded the British cantonment at Habbaniya and trained their guns on it.

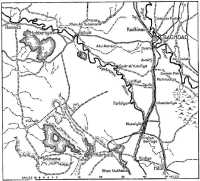

Habbaniya, on the south bank of the Euphrates 50 miles west of Baghdad, contained the headquarters of Air Vice-Marshal H. G. Smart’s Iraq Command of the Royal Air Force, No. 4 Flying Training School (about 1,000 men of the R.A.F. in all), a company of eighteen armoured cars of the R.A.F., and five companies, totalling 1,000 men, of Assyrian (Christian) and Kurdish troops led by twenty British officers. The area was surrounded by a fence along which, at intervals of 500 yards, were fourteen blockhouses, but was overlooked by a plateau.

The eighty training aircraft in the flying school were hastily formed into four squadrons manned by instructors and students. Smart could also call on some Wellingtons that had been flown to Shaiba, where there was also an army cooperation squadron, No. 244, supporting the force at Basra. On the 30th 350 men of a British battalion were flown in from Basra.

When asked to withdraw, the Iraqi commander replied that he would open fire on troops or aircraft leaving the camp. Thus the situation remained until dawn on 2nd May when, on Smart’s orders, all the available training aircraft were loaded with bombs and took off from the airfield. Within a minute the Iraqi artillery opened fire. The aircraft bombed and strafed the Iraqi gun positions, in three days silencing more than half of them; but this did not dissuade the Iraqis from continuing the siege. The garrison was outnumbered and had no artillery except two old 18-pounders. Nevertheless it patrolled vigorously by night and, on 5th May, achieved such success that the Iraqis began to withdraw to a safer distance. Next day the British troops and Iraqi levies defeated an enemy rearguard and cleared the plateau, capturing more than 400 men and much useful equipment.

On the fifth day the Iraqis were on the defensive. Four Blenheim fighters had reinforced the squadrons at Habbaniya, and Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac, now commanding the air force in Palestine and Transjordan, had established a base at the “H.4” Pumping Station near the Iraq frontier to prevent the enemy, whether Iraqi or German, from landing aircraft at “H.3” or at Rutba.4

Lieut-General Quinan5 arrived from India on 7th May to take command. He was informed that he was to develop and organise the port of Basra “to any extent necessary to enable such forces, our own or Allied, as might be required to operate in the Middle East, including Egypt, Turkey, Iraq and Iran, to be maintained”, to secure control of all communications in Iraq, and be ready to protect the Kirkuk oilfield and the pipe-line to Haifa, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s installations, and the R.A.F. depots at Habbaniya and Shaiba. He was informed that his force would be increased to three infantry divisions and possibly one armoured division.

At this stage control of operations in Iraq were transferred from Auchinleck to Wavell, who could not, however, send help on the scale envisaged. It was important to crush the Iraqis quickly before the threatened attack on Crete opened. A flying column which eventually included an incomplete mechanised cavalry brigade (the 4th), an incomplete artillery regiment, 250 men of the Transjordan Frontier Force, part of the 1/Essex Regiment and a company of armoured cars of the R.A.F., was assembled at H.4 and sent across the desert. Having recaptured Rutba on 10th May, it arrived at Habbaniya on the 18th. On the 19th the Habbaniya garrison made a cleverly-organised attack on Falluja, across the Euphrates, now the main Iraq position in the area, and captured it. Thence the column from Palestine assisted in defeating a determined counterattack and drove the Iraqis back to Baghdad where an armistice was signed by the Mayor on 31st May and a friendly government was established.6 Rashid Ali, the Italian Consular staffs and the Mufti of Jerusalem had fled to Persia. By this time the two other brigades (the 21st and 25th) of the 10th Indian Division had arrived at Basra.

At the time, the revolt appeared to British leaders to be part of a coordinated German offensive against Crete and Iraq. But we know now that during May the German air force in the eastern Mediterranean was concentrated against Crete, and the flimsy help that Hitler was willing to spend in Iraq was confined to the supply of French weapons from Syria and a “limited” air force, which was to be “an agent for promoting greater self-confidence and will to resist among the Iraq armed forces and civilians”.7

Such efforts as the Germans and Italians made to help the Iraqis were belated and parsimonious. After discussions lasting for the five weeks which followed Rashid Ali’s coup, Rudolph Rahn, a vigorous member of the foreign propaganda department of the German Foreign Office, was sent to Syria (in the second week of May) to organise the sending of supplies to the Iraqis; and a Major von Blomberg flew to Damascus to reconnoitre airfields in Syria and Iraq with the object of flying two squadrons in. Iraqi anti-aircraft gunners mistakenly shot down Blomberg’s aircraft when it appeared over Baghdad, and he was killed.

Nevertheless, from 13th May onwards German aircraft based at Mosul and Erbil were in action in Iraq, and later in the month Italian aircraft took part. On 16th May three Heinkels attacked Habbaniya and did severe damage – more than the Iraqi artillery and aircraft had done in five days. By the 28th, however, only one German fighter and one bomber were still serviceable.

Rashid Ali and his followers were bitter about the failure of Germany and Italy to give substantial help. Rahn had sent from Syria some captured French arms but they proved useless; the Germans had delivered no gold – an essential ingredient of an Arab revolt. The Chief of the

German General Staff, General Halder, wrote in his diary on 30th May that “owing to deficient preparation and the impossibility of sending effective support, the Iraq show, which is more in the nature of a political rising than a conscious fight for liberation, must eventually peter out. Whatever the outcome, however, it did force the British to spread themselves critically thin, both during the Crete operations and at a time when our situation in North Africa was rather precarious”.

Even this was an over-estimate of the effect of “the Iraq show”. It was a source of great satisfaction to the British Commanders-in-Chief that before the attack on Crete opened the Iraq army had been defeated. By bold action and at remarkably little cost, the British forces had asserted their control of Iraq and its oilfields, the pipe-line to Haifa, and the outlet of the Persian oil. The effort had involved merely a brigade from Palestine and two brigades of Indian troops destined for Malaya. The success of British arms and the weakness of Axis support for Iraq restored British prestige in the Arab world, affecting the attitude of nationalists not only in Iraq but in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine.

Meanwhile in an effort to halt the German-Italian offensive in Africa, Mr Churchill on 14th April had ordered that the Mediterranean Fleet must make the port of Tripoli unusable. Admiral Cunningham objected to a proposal that the battleship Barham be sunk at the entrance to the harbour, but at length, on 21st April, he bombarded the port and emerged with his fleet unscathed. Later in April, on Churchill’s orders, a convoy of five ships carrying 240 tanks, including 180 infantry tanks, was sent through the Mediterranean to help re-equip Wavell’s armoured regiments. On the night of the 8th–9th May one ship of the convoy struck a mine when nearing the narrow passage between Sicily and Tunisia and sank, but the others continued. Encouraged by this success Churchill suggested that one ship should unload a few tanks in Crete on the way eastwards but the Chiefs of Staff “deemed it inadvisable to endanger the rest of the ship’s valuable cargo by such a diversion”.8 Churchill then suggested that twelve tanks should be shipped to Suda Bay as soon as the main cargoes had been discharged at Alexandria, and this was ordered. Wavell replied, however, on 10th May that he had already arranged to send six infantry and fifteen light tanks to Crete.

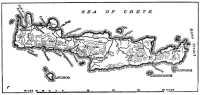

The steep and narrow mountain range which forms the backbone of Crete falls sharply into the sea along most of the south coast, but in the north are three largish areas of flatter land where cereals, vines and olives were cultivated on terraced slopes or on small pockets of level ground. Of these the westernmost was round Suda Bay and Canea, the capital, which had a population of 36,000; the next had its centre at Retimo about 30 miles east of Canea. The easternmost was at Heraklion, the largest town and port, and with a population of 43,000.

Near each of these towns an airfield had been made, and there were no other airfields on the island. Only one road that could be used by motor vehicles travelled the island from east to west and for most of its length it ran close to the northern shore. Five secondary roads crossed the island from north to south: one joined Maleme, the airfield near Canea, to the south coast; another climbed over the range from Suda Bay towards Sfakia but degenerated into a goat track five miles from that village; a third and fourth linked Retimo and Heraklion with Timbakion; and at the extreme eastern end of the island a fifth travelled over the narrow isthmus of Ierapetra. Suda Bay was the only port that could accommodate large freighters and it had only one jetty and no crane. From the defenders’ point of view Crete “faced the wrong way with its three aerodromes, two harbours and roads all situated on the north coast”.9

After a British garrison, including two infantry battalions of the 14th Brigade and a substantial contingent of anti-aircraft artillery, had been landed in Crete in November 1940, the Greeks had sent their 5th (Cretan) Division to fight in Albania, leaving only training units on the island. When late in November a proposal to add an Australian brigade to the garrison was abandoned, a commando unit, 385 strong, was temporarily stationed in Crete; the British force on the island then totalled 3,380; the Greek 3,733 with only 659 rifles.10 In this period the policy was to maintain a garrison of one British and one Greek brigade, but to build up a base able, if necessary, to accommodate a full division and some ancillary units. In December Mr Churchill urged that “many hundreds of Cretans” be employed enlarging and improving the aerodromes. In February 1941, the 14th Brigade was brought to strength by the addition of a third battalion, but in the meantime the Greek troops had been reduced to fewer than 1,000.

Indeed, in December and during the first three months of 1941 few preparations were made to meet a possible invasion. The garrison was placed where administration was easy, water plentiful, and malaria absent. Six officers in rapid succession held command. Brigadier Tidbury11 was replaced by General Gambier-Parry on the 8th January; General Gambier-Parry went away to take command of the 2nd Armoured Division and Lieut-Colonel C. H. Mather (52nd L.A.A. Regiment) – the senior officer then remaining – commanded from 2nd to 19th February. Thereafter Brigadier Galloway commanded until the 7th March, when he was appointed to General Wilson’s staff in Greece, and Mather again took over temporarily. Brigadier Chappel12 (newly appointed to the 14th Brigade) next commanded, from 21st March to 26th April. Then Major-General Weston13 of the Royal Marines, who had recently arrived from England, took over. He had already visited Crete and made a reconnaissance.

The arrival of Weston was partly the result of a decision made on 1st April by the Commanders-in-Chief to make Suda a fleet base and not merely a fuelling station. This decision was in tune with the action of the Chiefs of Staff in London in ordering to Crete, in January, the “Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisation”, which Weston commanded. The M.N.B.D.O. had been initiated a few years after the previous war with the object of providing the fleet with a base which could be rapidly established in any part of the world; doubtless it was considered most improbable that the commander of this organisation would be placed in a situation where he would be called upon to conduct operations against an invader.

The M.N.B.D.O. included a landing and maintenance group whose task was primarily to build a naval base, including buildings, jetties and roads; a defence group, including coast, anti-aircraft, anti-tank and searchlight batteries; and a land defence force including rifle companies, light artillery batteries and machine-gunners. Its total strength was 8,000, but only the landing and maintenance group, a searchlight regiment, one anti-aircraft regiment and some other specialists – about 2,000 men in all – would arrive in Crete before the invasion began. At the time of the evacuation from Greece the anti-aircraft batteries on Crete were: 151st and 234th Heavy; 159th, 156th, and 7th (Australian) Light Batteries; and 304th Searchlight Battery. As a result of the arrival of M.N.B.D.O. units, and of other additions from Egypt, the anti-aircraft defences on Crete late in May included sixteen 3.7-inch, sixteen 3-inch, thirty-six 40-mm guns, and twenty-four searchlights. (The Chiefs of Staff had in November accepted in principle that at least fifty-six heavy and forty-eight light guns and seventy-two searchlights were needed.)

As a result of the failure in Greece, Crete ceased to be the site of a relatively sheltered naval station and became the foremost Allied position facing the German advance through the Balkans. Indeed, a week before Weston took command, the intention to hold an Allied front in Greece had been abandoned; and, two days before, the first large-scale embarkation from Greece took place and troops from Greece were being hastily landed in Crete in their thousands so that the ships could hurry back for more.

Eleven days before he actually assumed command General Weston had made a report on the defence of Crete. He said that he considered that if Greece was overrun a major invasion by sea would become possible. He decided that one brigade group was needed at Suda–Maleme, and another at Heraklion with a detachment at Retimo. Three days later General Wavell warned Weston of the possibility of attack by airborne troops. On the 24th April, Wavell’s joint planning staff reached the conclusion that airborne attack would probably be delayed until it could be sustained by sea – perhaps three or four weeks after the mainland had been overrun – and that, ultimately, a garrison of three brigades would be required. In the meantime the existing garrison should be increased to two brigades, all fresh troops; any troops arriving from Greece should be taken to Egypt; three fighter squadrons should be based on Crete. After having considered these reports, and apparently expecting that he would have about a month for preparation, Wavell decided not to send additional troops (except one mountain battery when available) until the embarkation from Greece was finished. Two months’ supplies for two brigades were to be landed as soon as possible.

Thus, although the possibility of an evacuation from Greece had been in mind since early in March, plans and preparations to defend Crete against a major attack were not initiated until the middle of April. Much that could have been done in the meantime – reconnaissance, shipping of vehicles, improvement of roads and harbours, the equipment and training of Greek forces, and the establishment of effective liaison with them – remained undone. The responsibility rests not with the succession of local commanders, whose role was to administer a small garrison, but higher up, whence came no directions to begin effective preparation to defeat invasion.

When Weston took command one of his most pressing responsibilities was to accommodate and feed perhaps 50,000 men rescued from Greece. Already on the 17th April (four days before the embarkation from Greece was ordered) tents, clothing and blankets for 30,000 men had been asked for from Egypt. A trickle of troops and civilian refugees began to arrive from Greece on the 23rd April. On the 25th, in the first large-scale shipment from Greece, some 5,000 troops were put ashore at Suda Bay; and, in the succeeding days, transports and warships disembarked 20,000 more. There were no tents to shelter the new arrivals. They were guided to bivouac areas among the olive trees, where, lacking even blankets and greatcoats, they had to sleep on the ground with no covering but their clothes. Some had no mess gear. In the first few days there was little for

many to do except rest under the olive trees, forage for food and equipment, eat – and perhaps get into trouble. The men, used to drinking beer, found the heavy Greek wines treacherous. Even fighting units which had landed organised and more or less complete in numbers lacked tools with which to dig field works. “Officers and men on arrival from Greece were sent, as far as possible, to any of their unit who had arrived previously and had been organised under an officer. ... The only cooking utensils were petrol tins; a very large number of men fed out of tin cans as there were no mess tins, knives, forks or spoons available in ordnance in large quantities.” Meat-and-vegetable tins were used as pannikins, herring tins as dixies, and spoons and forks were whittled out of wood.

It was hard to get clean clothes and lice appeared (wrote an Australian). We had a long fight with them – the boys would do a day in underpants while the women washed their clothes, and they are great washerwomen; but until the great day when we were given a shirt and shorts each, the lice were always with us. I had a blanket and greatcoat, but for a week or more shared the blanket with three others. We would sleep in a row with greatcoats on and the blanket over our feet. ... I slipped into Canea and bought a brush and razor. Except for a table knife that was all my equipment.

“Conditions very peaceful in the pleasant waiting existence,” wrote the diarist of a New Zealand unit concerning these first days, “parties bathe in the Mediterranean and bask in the sunshine: the area is fertile with vineyards, cornfields and vegetable patches, and orange vendors ply a steady trade.”

The arrival in Crete of officers from Greece who were senior to Weston accelerated the rate at which the command of the garrison changed hands. When General Wilson arrived, it was to him, as senior officer, that General Wavell sent a signal that Crete must be denied to the enemy, that until they could be moved to Egypt all troops from Greece were available to defend the island, and that the air force could not send more aircraft “for some time to come”. “In view of our present shortage troops, British element garrison should be kept to essential minimum and fullest use should be made of reliable Greek troops,” he added. It seems that Wavell and his staff then had little conception of the condition of the units arriving from Greece or the general disorganisation on the island as a result of the rapid unloading of tens of thousands of ill-equipped troops. General Wavell asked General Wilson, in conjunction with General Weston and General Mackay, to examine the problem of what should be the essential permanent garrison in Crete. (Mackay had departed for Egypt, however, on the 29th April, believing that the greater part of his division was there.)

At that time one battalion of the garrison (2/Black Watch) was at Heraklion and the remainder of the 14th Brigade in the Suda Bay area. The air force under Group Captain Beamish14 included four depleted squadrons from Greece – No. 30 with from six to eight serviceable

Blenheims, Nos. 33 and 80 with six Hurricanes between them, No. 112 with six serviceable Gladiators – and one squadron from Egypt (No. 203) with nine Blenheims. At Maleme was also No. 805 Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm.

Wilson reported that the enemy would not improbably attempt a combined seaborne and airborne attack in the near future. His estimate of the necessary garrison somewhat exceeded those of Weston and the joint planners: three brigade groups each of four battalions and one motor battalion distributed between the Suda Bay area and Heraklion. He concluded: “I consider that unless all three Services are prepared to face the strain of maintaining adequate forces up to strength, the holding of the island is a dangerous commitment, and a decision on the matter must be taken at once.” Here he indicated a basic problem: how was a defending force to be maintained? There was a limited store of supplies and limited equipment for a garrison of one brigade totalling some 5,000 men; this store was in process of being increased to 90 days’ supplies for 30,000 men. From Greece, however, had come perhaps 25,000 men, who, besides being fed, needed to be largely rearmed and reclothed, and who possessed no vehicles or heavy weapons and little ammunition. Ships carrying supplies from Egypt had to make a hazardous voyage to ports on the north coast and use ill-equipped harbours where unloading was slow. The problem of supply was complicated by the presence on the island of a population exceeding 400,000, partly dependent on imported grain, and of 14,000 Italian prisoners of war captured by the Greeks.

On 28th April M. Tsouderos, the Greek Prime Minister, whose Government was now established at Canea, presided at a meeting which Generals Wilson and Weston, Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac, Rear-Admiral Turk, and Group Captain Beamish attended. The Greek representatives explained that the Greek forces under General Skoulas consisted of 2,500 gendarmes, 7,500 soldiers, and 1,000 reservists, organised into eleven battalions none of which was well equipped. They asked that a British general be appointed to command the Allied forces on the island, and that the Greek troops be armed with British weapons.

In London that day the Joint Intelligence Committee had estimated that the Germans had aircraft enough round the eastern Mediterranean to enable them to land from 3,000 to 4,000 paratroops or airborne troop:. on Crete in a first sortie, and might make from two to three sorties in a day from Greece and three or four from Rhodes. This estimate was immediately passed on to Cairo; and, the same day, Churchill sent Wavell the following message:

It seems clear from our information that a heavy airborne attack by German troops and bombers will soon be made on Crete. Let me know what forces you have in the island and what your plans are. It ought to be a fine opportunity for killing the parachute troops. The island must be stubbornly defended.15

Wavell replied that in addition to the original garrison of three battalions and the anti-aircraft and coastal batteries, Crete now contained

some 30,000 men evacuated from Greece. “It is just possible,” he added, “that plan for attack on Crete may be cover for attack on Syria or Cyprus, and that real plan will only be disclosed even to [their] own troops at last moment.”

Churchill proposed that General Freyberg, for whose courage he had great admiration, should be placed in command in Crete, and General Wavell agreed.

On the 29th April the convoy carrying Freyberg and his staff and the 6th New Zealand Brigade reached Suda Bay. Freyberg went ashore with his chief of staff, Colonel Stewart, and senior administrative officer, Lieut-Colonel Gentry,16 thinking to obtain a passage by air to Egypt, where he understood his division would be assembled and reorganised, and to visit his 5th Brigade which he knew was staging in Crete (he did not know that other New Zealand troops were on the island). It was arranged that he should set off for Egypt early next morning in a flying-boat, but, when morning came, he was instructed to remain and attend a conference at Canea a few hours later. In his report Freyberg described the meeting:

We met in a small village between Maleme and Canea and set to work at 11.30. General Wavell had arrived by air and he looked drawn and tired and more weary than any of us. Just prior to sitting down General Wavell and General Wilson had a heart-to-heart talk in one corner and then the C-in-C called me over. He took me by the arm and said “I want to tell you how well I think the New Zealand Division has done in Greece. I do not believe any other Division would have carried out those withdrawals as well.” His next words came as a complete surprise. He said he wanted me to take command of the forces in Crete and went on to say that he considered Crete would be attacked in the next few days. I told him that I wanted to get back to Egypt to concentrate the division and train and re-equip it and I added that my Government would never agree to the division being split permanently. He then said that he considered it my duty to remain and take on the job. I could do nothing but accept.

It was in the course of their “heart-to-heart talk” that Wavell had told Wilson that he wished him “to go to Jerusalem and relieve Baghdad”. To Wilson this

came as a surprise as I had no idea what had been happening outside Greece for the last three weeks.17

At the conference it was decided that the likely scale of attack was by 5,000 to 6,000 airborne troops and possibly seaborne troops also, launched against Maleme and Heraklion airfields; no additional air support could be provided. Freyberg took Wavell aside and told him that there were not enough men on Crete to hold it, and that they were inadequately armed; and he asked that the decision to defend the island be reconsidered if aircraft were not to be available. Wavell, however, said that the scale of the probable attack had possibly been exaggerated, that he was confident

that the troops would be equal to their task; efforts would be made to obtain fighter aircraft from England. He told Freyberg that in any event Crete could not be evacuated because there were not enough ships to take the troops away.

The main defence problems which faced me in Crete were not clear to me at this stage (wrote Freyberg afterwards). I did not know anything about the geography or physical characteristics of the island. I knew less about the condition of the force I was to command. Neither was I aware of the serious situation with regard to maintenance and, finally, I had not learnt the real scale of attack which we were to be prepared to repel.

Freyberg received the estimate noted above of the possible scale of a German attack on 1st May. He decided that the sooner he “introduced a little reality into the calculations for the defence of Crete the better”, and immediately sent a telegram to Wavell stating that his forces were “totally inadequate to meet attack envisaged”, and that unless the fighter aircraft were increased and naval forces made available he could not hope to hold out with a force devoid of artillery, with insufficient tools for digging, inadequate transport, and inadequate reserves of equipment and ammunition.18 He urged that if naval and air support were not available, the holding of Crete should be reconsidered, and announced that it was his duty to inform the New Zealand Government “of situation in which greater part of my division is now placed”. Thereupon he cabled to his Prime Minister describing the position and adding:

Recommended you bring pressure to bear on highest plane in London either to supply us with sufficient means to defend island or to review decision Crete must be held.

Two days later Wavell sent a message to Freyberg stating, reassuringly, that he considered the War Office estimate of the scale of attack exaggerated, and informing him that naval support would be given, efforts were being made to provide air support, and artillery and tools would be sent. “I am trying,” he added, “to make arrangements ... to relieve New Zealand troops from Crete and am most anxious to re-form your division at earliest opportunity. But at moment my resources are stretched to limit.”

Wavell had sent a cable to Dill on the 2nd in which he said that “at least three brigade groups” and a “considerable number of anti-aircraft units” were required to garrison the island effectively. He described the existing garrison as comprising three British regular battalions, six New Zealand battalions, one Australian battalion, and two composite battalions of details evacuated from Greece. He added that the troops from Greece were weak in numbers and equipment and there was no artillery; and the scale of anti-aircraft defence was inadequate. “Air defence,” he added, “will always be a difficult problem.” This estimate implied, however, that if arms and equipment were sent to Crete the garrison on the ground would be adequate. Moreover, it was evidently so difficult to ascertain what forces were on Crete that Wavell’s list of the units there had considerably under-

stated them. There were seven, not six, New Zealand battalions (not including part of a machine-gun battalion); four Australian battalions, not one (not including a full machine-gun battalion and half of a fifth infantry battalion).19

General Blamey, now in Cairo as Deputy Commander-in-Chief, agreed with the current estimates of the force needed to hold Crete. In response to a request from the anxious Australian Cabinet, Blamey cabled, on 6th May, that he considered that Crete should not be abandoned without the sternest struggle. A possible scale of attack would be by one airborne and one seaborne division, the first sortie being made by one-third of an airborne division. (It will later be seen that the British Intelligence estimates were remarkably accurate.) The troops required to defend the island were three infantry brigade groups with coastal and harbour defences and a “reasonable air force”: the forces available were the 14th British Brigade and troops from Greece who were adequate in numbers but had no artillery. He considered that the 16th British Brigade, more artillery and fighter squadrons should be sent. “Situation far from satisfactory,” he added, “but everything possible being done to improve it.” He expected that most of the AIF would be withdrawn as soon as the 16th British Brigade could be sent in.

Meanwhile, on the 3rd May, Churchill had followed Freyberg’s message to the New Zealand Government with one of his own to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Mr Fraser, then in Cairo, in which he said that every effort would be made to re-equip the New Zealand Division, particularly with artillery “in which General Wavel1 is already strong”.20 From New Zealand, the acting Prime Minister cabled to Freyberg on the 4th that his government had made urgent representations to the United Kingdom Government on the lines he had indicated. Next day Freyberg sent a cable to Churchill in the course of which he said that he was “not in the least anxious about an airborne attack” and added:

I have made my dispositions and feel that with the troops now at my disposal I can cope adequately. However, a combination of seaborne and airborne attack is different. If that comes before I can get the guns and transport here the situation will be difficult. Even so, provided the Navy can help, I trust that all will be well.

Freyberg sent a message to Wavell that day urging that about 10,000 men who were without arms “and with little or no employment other than getting into trouble with the civil population” should be evacuated.

Freyberg had established his headquarters in dug-outs in the foothills east of Canea and was at work reorganising and redeploying his force. As chief staff officer he retained Colonel Stewart; his senior administrative officer was Brigadier Brunskill, the British officer who had occupied a similar post on Wilson’s staff in Greece; his artillery commander was Colonel Frowen of the 7th Medium Regiment, the same who had played

a leading part in making the artillery plan at Bardia. The filling of staff posts was a difficult problem because Freyberg had brought only two of his divisional staff ashore, yet had to create, in effect, a corps staff, and also a new staff for the New Zealand Division now commanded by Brigadier Puttick.

The garrison of Crete – about which, in the confusion, the leaders in Cairo and London were somewhat ill-informed – now included five main contingents: the 14th British Brigade and other troops of the original garrison; the incomplete New Zealand Division; a number of Australian units and detachments from Greece; part of the 1st Armoured Brigade and some personnel of other British units from Greece; some 10,000 Cretan recruits, very raw.

The New Zealand Division on Crete included the 4th and 5th Brigades, with seven infantry battalions-18th, 19th, 20th, 21st, 22nd, 23rd and 28th (Maori) – and a majority of the divisional troops.21 The 6th Brigade Group, which had sustained small losses on Greece, had called at Suda Bay, but, on naval orders, had been sent on to Alexandria. The Australian contingent consisted principally of three groups fortuitously landed on Crete. First there was the 19th Brigade Group (at that time including the 2/1st, 2/4th and 2/11th Battalions, half the 2/8th Battalion and the 2/2nd Field Regiment), which had been embarked from Megara on the 25th–26th; then those Australians who had been taken off the sinking Costa Rica and carried to Suda Bay in destroyers (among these were the 2/7th Battalion, the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion, and about half of the 2/8th); finally there were the 2/3rd Field Regiment (which had embarked with the 4th New Zealand Brigade) and other units and detachments.

After the departure of General Mackay and his staff, Brigadier Vasey, as senior Australian officer in Crete, found himself not only in command of an Australian brigade group but bearing a responsibility for a total of some 8,500 troops, including almost-unarmed units equivalent to a second brigade, besides parties of varying size belonging to about thirty other separate units. There was no other Australian brigadier on the island. Vasey, like Freyberg, was anxious to send his unarmed men to Egypt, and on the 5th May he dispatched a message through Freyberg’s headquarters to AIF headquarters recommending the removal of some 5,000 such troops and stating that he had organised four battalions (2/4th, 2/7th, 2/8th and 2/11th22) with the 2/8th Field Company, a company of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion, and the 2/7th Field Ambulance for garrison duties. The implication was that other units and detachments should be removed.

Having received no reply to this signal Vasey, on the 12th, sent a letter to Brigadier Rowell, now senior at Australian Corps headquarters, by an officer who was returning to Egypt. In it he explained that the 2/4th Battalion was then at Heraklion, that he commanded four battalions and

an artillery regiment in the Retimo sector, and that there was an Australian composite battalion in the Suda Bay area. His first problem, he said, was the dispatch of troops from Crete. General Freyberg had ordered that no troops with an operational role should depart until replaced. He had heard that it was intended to re-form the 17th Brigade as soon as possible, but he was sure that Freyberg would resist sending any armed infantry from Crete. Vasey pointed out also that no letters had arrived in Crete (he himself had received none since he left Egypt for Greece in March). “Every time I go round and see any of the troops,” he added, “the first question is ‘When is the mail coming?’ “ He asked also for a pay staff and a canteen and pointed out his shortage of medical supplies, and hats. Every man then had a blanket and he hoped each would soon have a groundsheet and greatcoat.

On the whole (he wrote) the discipline of the unarmed and more or less unemployed personnel is fair. There have been a few major incidents including an alleged murder, but so far we have always been able to apprehend the culprits. I have taken to myself the power to convene FGCMs (field general courts martial) and cases are proceeding apace. ... I hope the Legal Staff Officer will review the proceedings of the courts martial with a kindly eye.

The British contingent included, in addition to the fresh 14th Brigade (in Freyberg’s words) “four weak and improvised battalions from Rangers, Northumberland Hussars, 7th Medium Regiment, 106th Royal Horse Artillery”, the units of the mobile naval base, all the coast artillery, nearly all the anti-aircraft artillery, and a number of base units.

The 10,000 Greek troops were organised in three garrison battalions – one each at Canea, Retimo and Heraklion – and eight recruit battalions. As noted above the 5th (Cretan) Division had long since been sent to Albania, and now had been captured there. The recruits on Crete had been given only a few weeks’ training; although five types of rifle were in use some men had none; there were only about 30 rounds a rifle; few men had fired a shot. Freyberg was anxious to reorganise and rearm the Greeks. On the 5th he informed Wavell that the King of Greece had placed what remained of the Greek Army under his command, and that he intended to lend to the Greeks Brigadier Salisbury-Jones23, and a number of other British officers to help with their training. Four days later he wrote to Wavell’s chief of staff, Major-General Arthur Smith, that the Greeks were pressing him to raise a Cretan militia, but that that was dependent on receiving arms and settlement of a policy for the future of the Greek Army. “I am impressed with the Greek rank and file,” he wrote, “but a great deal of dead wood must go, especially officers. ... I am certain that one division could be raised at once, and two divisions eventually, if the problem is tackled at once before they become despondent from lack of equipment and employment.” On the 11th Freyberg informed Smith that the Greek leaders had agreed that the Greek troops should be

organised on British war establishments and brigaded with British troops. The immediate aim would be to raise and arm twelve battalions and three field batteries.

It is evident, however, that the political disunity of Greece and the weakness of the leadership placed immense difficulties in the way of rapid and effective organisation of a Cretan army on the lines pictured by Freyberg.

On the 3rd May, Freyberg issued an instruction defining the organisation and role of “Creforce”, as it had been entitled since November. The infantry allotted to the Heraklion sector (Brigadier Chappel) comprised the 14th British Brigade (two battalions), the 2/4th Battalion,24 the 7th Medium Regiment armed with rifles, and two Greek battalions; to the Retimo sector (Brigadier Vasey) four Australian battalions (2/1st, 2/7th, 2/11th and 2/1st Machine Gun25) and two Greek; to the Suda Bay sector (Major-General Weston) the M.N.B.D.O., the 1/Welch, the 2/8th, and one Greek battalion; to the Maleme sector the New Zealand Division comprising the 4th Brigade (now commanded by Colonel Kippenberger), the 5th (Brigadier Hargest) and three Greek battalions.26 The 1/Welch and 4th Brigade (less one battalion) were in Force reserve, but administered by their sector commanders. Those commanders were instructed to dispose one-third of their troops on or round the landing grounds and two-thirds “outside the area which will be attacked in the first instance”. The attack would probably take the form of intensive bombing and machine-gunning of the airfields and their vicinity, a landing by paratroops to seize and clear the airfields, and finally the landing of troop-carrying aircraft. In addition seaborne attack, probably on beaches close to the aerodromes and Suda Bay, must be expected.

On 8th May it was estimated that the original garrison of Crete numbered 5,300, and the troops from Greece 25,300. It was hoped that by 15th May the original garrison would have been increased to 5,800 and other contingents reduced to: New Zealand 4,500; Australian 3,500; other British 2,000. A policy was adopted of using ships returning empty after landing supplies, to take away men, chiefly of service and base units, for whom there was no role in Crete, but the ships could take only limited numbers. The navy had lost ships in the embarkation from Greece and was fully occupied. As the weeks passed and air attacks on Suda Bay and shipping increased, it became evident that it would not be possible to remove all the unwanted troops who had arrived from Greece. Of these some 3,200 British (including Palestinians and Cypriots), 2,500 Australians and 1,300 New Zealanders were sent on to Egypt; by 17th May

the garrison included about 15,000 British, 7,750 New Zealanders, 6,500 Australians, and 10,200 Greeks.27

Unneeded men of the R.A.F. were also moved to Egypt, many being ferried by No. 230 Squadron, which itself returned to Egypt on 30th April. There were then the following squadrons on the island:

| Station | Aircraft | |

| 30 Squadron | Maleme | 12 Blenheims |

| 33/80 Squadron | Maleme | 6 Hurricanes |

| 112 Squadron | Heraklion | 12 Gladiators |

| 805 Fleet Air Arm Squadron | Maleme | 6 Gladiators and Fulmars |

General Freyberg was anxious to arrange the departure of the King of Greece and his Ministers, who were at Canea. Almost every day the Canea area was being bombed. “It seemed to me,” wrote Freyberg afterwards, “that in the circumstances the front line – and Canea during the middle of May was certainly very much in the front line – was not the right place for the King and the National Government. ... I did not see any reason to expose those important and gallant people to the risk of being killed or wounded or, far worse, captured.” Freyberg received a cable from the Foreign Office stating that the Greek political leaders were not to be exposed to undue risk and that he was to be the judge of what undue risk was, but emphasising that their presence in Crete was having an important effect at home and in neutral countries and that the King should remain until the last possible moment. Consequently, on the 9th May, Freyberg reached an agreement with the King that he and the Government should depart on the 14th and the decision be explained to the people of Greece. However, soon afterwards, he received a cable that the British War Cabinet felt very strongly that the King and Government should stay, even if the island was attacked. Thereupon Freyberg informed the King and M. Tsouderos that for the moment, there was no reason for them to go. Freyberg invited them to go into quarters within the defended area, but it was finally agreed that they should live in houses in the foothills well south of the perimeter ready to move farther south into the mountains if need be. Freyberg provided a platoon of the 18th Battalion under Lieutenant Ryan28 as a guard and asked Cairo to provide a warship or flying-

boat to take the King and his party away if necessary. Colonel Blunt, the British military attache, was put in charge of the whole group.

Another embarrassment was the presence on Crete of the 14,000 Italian prisoners of war. After prolonged negotiations with the Greeks, who feared that to hand over these prisoners might be contrary to international law, it was agreed that they should be taken to Egypt and thence India, but they were still on the island on the 20th May.

Meanwhile a trickle of equipped troops and of arms and supplies for the men from Greece was reaching Crete. During May part of the M.N.B.D.O. – some 2,200 marines equipped principally with coast and anti-aircraft guns and searchlights – a troop of mountain artillery armed with 3.7-inch howitzers, a troop of sixteen light tanks, six infantry tanks, and two infantry battalions (2/Leicesters and 1/Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders) arrived from Egypt. The 2/Leicesters were landed at Heraklion on 16th May from the cruisers Gloucester and Fiji; the 1/Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and two infantry tanks were landed by the Glengyle at Timbakion on the south coast on the 19th.29 It was Wavell’s intention that this battalion group should form a reserve to the Retimo and Heraklion forces.

It has been mentioned that on 2nd May Wavell reported that there was no field artillery on Crete; on the 6th Blamey in a cable to the Australian Government emphasised that the troops landed on Crete from Greece had no artillery, and on the 3rd Churchill had cabled to Fraser, the New Zealand Prime Minister, then in Cairo, that every effort would be made to re-equip the New Zealanders particularly with artillery, in which Wavell was “already strong”. On the 7th Wavell had sent a cable to Freyberg in the course of which he said that he was trying to arrange the dispatch of about half a dozen infantry tanks and some light tanks and that he could make the 16th (British) Infantry Brigade available if ships could be found but “probably better to complete equipment of fighting units now without arms”. He asked Freyberg to cable his principal requirements. Freyberg replied:

First. Agree not desirable at this juncture to attempt to land 16th Inf Bde and broadly speaking do not require additional personnel of any arm as a first priority. Prefer concentrate on landing essential equipment and stores. Second. Agree infantry tanks with crews and light tanks valuable also carriers. Third. Ample artillery personnel available also sights and directors without stands. 25pr ammunition could be unloaded off Runo if guns available. Otherwise hasten despatch of 75 mm guns. Tractors and artillery signal equipment will also be needed. Fourth. Other weapons required. Vickers guns and belts complete at least 24. Tripods for existing guns 30. Bren guns with magazines all possible to meet existing shortage of 300 and magazines for existing 300 guns. Rifles and bayonets 5000 for British plus 500 for Greeks. Mortars 2-inch and 3-inch as many as possible. Fifth. Hasten despatch of 20 cars and of motor-cycles already asked for but increase from 30 to 100. Also expedite 70 15-cwt trucks and balance of one reserve MT Coy predicted in fourth of your [signal] of 3rd May as part of next convoy. Sixth. Ammunition. .303 inch bandoliers

5 million carton 2 million stripless belts half million. ATK rifle 10000. Mortar ample supply with weapons you send. Thompson sub-machine gun 100000. Grenades H.E. 3000. Seventh. Signal equipment repeat demand of 4th May plus major items of ... equipment ]on the establishment of] three infantry brigade signal sections. Eighth. Workshops and personnel and spares and ammunition and POL for any tanks sent. Ninth. Diesel oil 6000 gallons. Tenth. No shore installations here capable of lifting heavy tanks.

The 6th Australian and the New Zealand Divisions had lost their guns in Greece, and so had the three British field or medium regiments there. The British formations in the Middle East generally had always been short of field artillery, and that was a factor which operated against organising into divisions the considerable number of well-trained regular infantry battalions in Egypt and Palestine. The Australian force, however, possessed a considerable pool of trained field artillery regiments. Of the 9th Division’s three such regiments only one – the 2/12th – was in Tobruk; two others – the 2/7th and 2/8th – were in reserve in Egypt. There were also the three regiments of the 7th Division-2/4th, 2/5th and 2/6th. Two regiments of “corps artillery”, not attached to any particular division, arrived from Australia in May, but had no guns.

On the 20th May five Australian field artillery regiments in Egypt – 2/4th, 2/5th, 2/6th, 2/7th and 2/8th – were equipped with guns. The guns of these five regiments included 36 modern 25-pounders, 59 old 18-pounders (some in poor condition), and 24 4.5-inch howitzers. In the last week of May the 2/4th and 2/6th between them drew 24 additional 25-pounders from the depot at Tel el Kebir. Thus, by the end of the month the Australian regiments in reserve at Mersa Matruh and Ikingi Maryut held 60 25-pounders. To have withdrawn these guns from the idle Australian regiments and sent them to Crete would have enabled each of three regiments there to be armed with 20 guns – almost their full establishment. The presence on Crete of 60 25-pounders would have transformed the situation. In the event no 25-pounders were sent to Crete. Among the shipments of arms which did arrive from Egypt were forty-nine Italian and French field guns.30 These enabled some artillery units to be partly rearmed but there were not enough, even of guns such as these, to equip all the artillery regiments, and several (including 102nd Anti-Tank, part of the 106th Royal Horse Artillery, the 7th Medium, and 2/2nd Australian) were armed as infantry.

In his report Freyberg wrote that evidently 100 guns were dispatched. “Sufficient to say that many did not arrive, others came without their instruments, some without their sights, some without ammunition, and some of the ammunition without fuses. ... The gunners ... were either British Regular Army, Australians or New Zealanders; men of infinite resource and energy; they set to work and one lot made a sighting appliance out of wood and chewing gum. Another lot of gunners made out charts which enabled them to shoot without sights or instruments. Nobody groused .. . and everybody got on with the job.” Some of the Italian guns were 75-mm

and some 100-mm. The rifles and machine-guns which were landed included American and Italian as well as British weapons.

While these plans were being made the defenders were under constant air attack. Shipping in Suda Bay had been regularly attacked from the air even before the embarkation from Greece began. There were particularly heavy air raids during 3rd May, and on the 4th the labour troops who had been unloading the ships were replaced by volunteers, chiefly from Australian engineer units and the 2/2nd Field Regiment, and commanded by Major Torr31 of the Australian engineers. These carried on unloading except when aircraft were directly attacking the ship they were working on. One of their best achievements was to retrieve a number of Bren carriers from a sunken ship with its upper deck several feet under water.32

At length the air attacks were causing such heavy loss that it was decided to use only ships fast enough to enter the danger area after dark, unload and be out of the danger area next morning. This could be done only by vessels of about 30 knots speed, and necessitated arriving at the pier about 11.30 p.m. and departing at 3 a.m. From 29th April to 20th May, 15,000 tons of army stores were unloaded from fifteen ships, eight of which were sunk or damaged. This rate of supply was less than half that considered necessary to maintain such a force – quite apart from the needs of the 400,000 Cretans. The reduction in the number of supply ships arriving in Crete made it apparent that the island could not be held indefinitely if air attack continued to be as heavy as it was during the first three weeks of May. By 19th May thirteen damaged ships lay in Suda Bay. The use of a port on the south coast would have greatly simplified the problem, but there was no unloading equipment there and much improvement of the roads would have been needed to bring equipment landed in the south to the garrisons in the north.

On the 14th May the organisation of the New Zealand Division was expanded by the formation of the 10th Brigade,33 consisting of the 20th Battalion, a composite battalion of artillery and army service corps men, and the 6th Greek Battalion. Colonel Kippenberger was given command of this new formation, Colonel Falconer34 taking the 4th Brigade until the 17th, when he was replaced by Brigadier Inglis35 who had been commanding the 9th Brigade in Egypt.

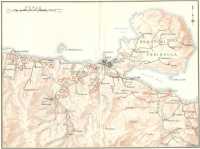

What steps had been taken to deploy the increased force then in Crete? West of Canea, in the Maleme sector, the problem was to defend the air-

field and a long beach. Brigadier Puttick placed his 5th Brigade to cover Maleme and the near-by beaches; the 10th occupied a position facing west astride the coastal plain and west of Galatas; the 4th Brigade was in the area east of Galatas under orders to be prepared “to move at short notice in any direction in a counter-attack role”, perhaps with the 1/Welch under its command.

Farther west at the little port of Kastelli was the 1st Greek Regiment of 1,030 men nearly all recruits aged 20 and 21, ill-clad, poorly officered and possessing only 600 rifles. Major Bedding36 (19th Battalion) and thirteen other New Zealand officers and NCOs were attached to them. There were also forty-five gendarmes and a well-organised and high-spirited home guard of about 200 with a variety of arms, including shotguns.

General Weston, who commanded the force in the Suda Bay–Canea sector, had to protect the harbour and the base. Improvised Australian battalions were deployed east of Suda Point, other improvised units were on a line south of Canea to prevent enemy paratroops who might land in the olive groves from advancing into the town, and a detachment was placed on the Akrotiri Peninsula. The improvised Australian battalions in the Suda Bay force were grouped under Lieut-Colonel Cremor, and included his 2/2nd Field Regiment (employed as infantry), two weak battalions – the 16th Brigade Composite Battalion and the 17th Brigade Composite Battalion – and a detachment of engineers and another of artillerymen.37 Gradually these units were armed, the 16th, for example, at length receiving American rifles for all its men, six Brens, but each with only one magazine, one Vickers gun without a tripod, two Hotchkiss guns with improvised mountings and three mortars without base plates.

Next to the east, in the Retimo sector, Brigadier Vasey had two main tasks: to defend the harbour and airfield of Retimo and the adjacent beaches, and to prevent a seaborne landing in Georgioupolis Bay whose eastern end was some seven miles to the west. He allotted two Australian battalions (2/1st and 2/11th) to Retimo, two (2/7th and the weak 2/8th) to Georgioupolis. At Heraklion were four British, one Australian and three Greek battalions. The principal formations and units in each sector were:

Maleme Sector:

New Zealand Division (Brigadier Puttick)

5th Brigade (21st, 22nd, 23rd and 28th (Maori) Battalions and N.Z.E. composite infantry unit, 327 strong). Total strength, 3,156.

10th Brigade (20th Battalion, Composite Battalion, detachment of New Zealand Cavalry, 6th Greek Regiment, 8th Greek Regiment). Total strength, 1,989 New Zealand troops, and 2,498 Greeks with 36 New Zealanders attached. The 20th Battalion was nominally in the 10th Brigade, but was not to be employed without the approval of the New Zealand Division. The field artillery included ten 75-mm guns and six 3.7-inch howitzers; there were two infantry and 10 light tanks.

Force Reserve:

4th New Zealand Brigade (18th, 19th Battalions). Total strength, 1,563. 1/Welch, 854 strong

Kastelli Sector:

1st Greek Regiment (1,030 strong)

Suda Sector: (Major-General Weston)

M.N.B.D.O.

1/Rangers

102nd Anti-Tank (as infantry)

106th R.H.A. (as infantry)

Cremor Force

2/2nd Field Regiment (as infantry)

16th Australian Composite Battalion

17th Australian Composite Battalion

Group “A” (600 men of R.A.A.)

Group “B” (600 men of R.A.E.)

2nd Greek Regiment

The Australians in this group totalled 2,280 officers and men. The several anti-aircraft units and detachments in the Suda sector possessed sixteen 3.7-inch, ten 3-inch, and sixteen Bofors guns. There were eight coast defence guns of various calibres.

Retimo Sector: (Brigadier Vasey)

19th Australian Brigade (2/1st, 2/11th, 2/7th, 2/8th Battalions)

Three Greek regiments (each of battalion strength).

One battery of the 2/3rd Field Regiment with fourteen guns of various models was in this sector. There were two infantry tanks at Retimo.

Heraklion Sector: (Brigadier Chappel)

14th Brigade (2/Black Watch, 2/York and Lancaster, 2/Leicester, 2/4th Battalion, 7th Medium Regiment – with rifles).

Three Greek regiments (each of battalion strength).

There were thirteen field guns in support, ten light and four heavy anti-aircraft guns, four infantry tanks (including two landed at Timbakion on the 21st) and six light tanks. On the 19th the 1/Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders were also at Timbakion waiting to move to Heraklion.

On 13th May systematic large-scale bombing of the defended areas had begun.38 The British fighter aircraft were flown nightly to Retimo airfield to avoid the bombing at Maleme and Heraklion. On the 16th Intelligence reports predicted that Crete would be attacked on the 17th, 18th or 19th by the XI German Corps including the 22nd Airborne Division, 25,000 to 35,000 men coming by air and 10,000 by sea. The objectives would be Maleme, Canea and the valley south-west of it, and Retimo. There would be a sharp attack by some 100 bombers and fighters and then 600 troop-carrying aircraft would drop waves of paratroops.

While Creforce as a whole was preparing for this coming invasion, the anti-aircraft gunners were in action every day and often many times a day against German aircraft. The ships in Suda Bay were the principal target. On the 19th a new fire system was put into effect whereby an “umbrella” of bursting shells was put up over the pier when ships discharging cargo

Dispositions, Suda–Maleme Area. 19th May

were attacked. Thereafter no bomb hit either a discharging ship or the jetty. Nevertheless the batteries round Suda, armed with a total of 16 modern 3.7-inch guns, and 10 older 3-inch guns, with 16 light Bofors guns, were not strong enough to give adequate protection against heavy air attack. At Retimo there were no anti-aircraft guns; at Heraklion four 3-inch and, initially, 10 Bofors. In the period up to 20th May, however, no anti-aircraft gun was irreparably damaged and the total casualties to the gunners were 6 killed and 11 wounded.

Although the equipment received was far less than was needed to refit them, the units deployed it with skill and enterprise. As the preparations continued, Freyberg’s confidence increased, and late on 16th May he sent the following cable to Wavell:

I have completed plans for the defence of Crete and have just returned from a final tour of defences. I feel greatly encouraged by my visits. Everywhere all ranks are fit and morale is now high. All defences have been strengthened and positions wired as much as possible. We have 45 field guns in action with adequate ammunition dumped. Two infantry tanks are at each aerodrome. Carriers and transport still being unloaded and delivered. 2nd Battalion Leicesters have arrived and will make Heraklion stronger. I do not wish to seem over-confident but I feel that at least we will give an excellent account of ourselves. With help of Royal Navy I trust Crete will be held.

On the 18th the following message reached Freyberg:

All our thoughts are with you in these fateful days. We are glad to hear of reinforcements which have reached you and strong dispositions you have made. We are sure that you and your brave troops will perform in deed of lasting fame. Victory where you are would powerfully affect world situation. Navy will do its utmost. Winston Churchill.

It was evident that there would be little air support in the coming battle. On 24th April Air Chief Marshal Longmore, after a visit to Crete, reported to the Chief of the Air Staff in London that a squadron of Hurricanes, with 100 per cent reserve of pilots and a generous rate of replacement, should be able to defend the Suda Bay naval base, but he doubted whether such a squadron could be kept up to strength because of the demands of North Africa and the probable heavy losses in Crete. In fact, on 19th May only four serviceable Hurricanes, three Gladiators and two Fulmars remained in Crete. That day one Hurricane was shot down over Maleme and the last Fulmars destroyed on the ground. Up to that time it was believed that the handful of defending fighters had shot down 23 enemy aircraft and possibly 9 others. Freyberg told Beamish that “it would be painful to see these machines and their gallant young pilots shot down on the first morning”, and with the agreement of Mr Churchill the few machines that remained were sent to Egypt. General Freyberg wished to mine all airfields, but was not allowed to because it was intended that fighters should return as soon as possible. All three fields had to be preserved.