Chapter 12: Defence of Retimo

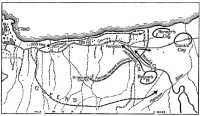

ROUND Retimo the mountains, sloping steeply down to the sea, were cut at every mile or so by deep gullies which ran out into a coastal shelf varying in width from 100 to 800 yards and terminating in a shingle beach. About five miles east of Retimo, a compact town with a population of about 10,000, lay the airfield, which was about 100 yards from the beach and parallel to it Immediately overlooking the airfield was a narrow ridge varying in height from 100 to 200 feet.

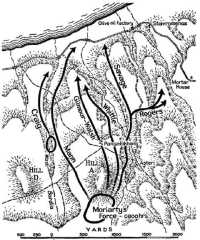

To understand the problems facing Lieut-Colonel Ian Campbell, who became the commander of the force defending Retimo airfield, it is necessary to see this ridge in some detail. A spur, which the Australians named Hill “A”, jutted to within 100 yards of the sea, commanding the eastern end of the airfield; about 1,000 yards east of Hill “A” was the small village of Stavromenos whose main building was an olive oil factory with a 50-foot chimney The ridge itself, separated from the main mountain system to the south by a narrow valley sheltering the villages of Pigi and Adhele, blended into the mountains about two miles east of the airfield, but, to the west, terminated abruptly just short of the village of Platanes, where the road from Kirianna through Adhele joined the main coast road. From the south the landing ground was dominated by Hill “D”, which rose between the Wadi Bardia1 on the east and the Wadi Pigi on the west. Between the Wadi Pigi and the Wadi Adhele the ridge continued. Beyond the Wadi Adhele lay Hill “B” which broadened out at its western end overlooking Platanes. To the west, overlooking Perivolia, was Hill “C”. Olive trees covered the whole area except the coastal plain, the inland valley near Pigi and the seaward slopes of Hills “A” and “B”. On these northern slopes were vineyards in full leaf, offering good cover. All the hillsides were terraced in steps up to 20 feet high, and thus men could move round the spurs without being seen by those higher up.

Since 30th April, when Campbell’s 2/1st Battalion arrived to take over the defence of the landing ground from Greek troops, the force had been steadily built up, until by 19th May there was the equivalent of a brigade group disposed to defend the air strip.2 Although the Australian infantry

was adequately equipped with small arms, ammunition for them was limited. There were only five rounds for each anti-tank rifle, eighty bombs for each of the four 3-inch mortars. The medium machine-gunners had but sixteen belts of ammunition to a gun. Uniforms and boots were in need of repair and few men received any replacements in Crete.

Unlike the defenders at the other two landing grounds, where there was both heavy and light anti-aircraft artillery, the force at Retimo had none, nor had they armour-piercing small arms ammunition. Consequently German bombers and fighters would be able with relative safety to fly low over the area and only their thin-skinned troop carriers would be in danger from the defenders’ small arms fire. The 2/1st Battalion had no signalling equipment except three telephones and some cable brought by the gunners; these Campbell used to link his headquarters with Hills “A” and “B”. Except for a few runners and the men required to maintain these three telephones, all signallers became riflemen. The 2/11th had a telephone for each company but very little cable. Communication between the two battalions was by runner. Enough barbed wire was received to make it possible to fence the whole front and the airfield.

There were rations enough to last ten days, but four days’ supply had been moved to the end of the road to Mesi so that the force could fall back there if it was pushed off the ridge above the airfield. The food supply was supplemented by buying pigs, vegetables, eggs, and goats’ milk from the farms and villages; the West Australians of the 2/11th Battalion hired milking goats and kept them in their lines.

Because the olive trees masked the southern slopes of the ridges the field guns and all but two of the medium machine-guns were placed well forward on Hills “A” and “B”, whence there was a clear field of fire north, east and west. The remaining two machine-guns were sited on the ridge above Hill “B”. On Hill “A” Campbell placed one company of the 2/1st, two 100-mm and four 75-mm guns and a platoon of machine-gunners. The remainder of the battalion occupied Hill “D” and the slopes over-looking the landing ground from the south. Here were four companies, the headquarters group having been converted into a rifle company because it lacked its normal equipment – mortars, vehicles, signal and pioneer gear and all except two carriers – and on a forward spur of this hill, whence he could see the whole coastal plain from Hill “A” to Retimo, Campbell placed his headquarters. The 4th Greek Battalion was stationed on the ridge between the Wadi Pigi and the Wadi Adhele with the remaining three Greek battalions in reserve among olive trees south of Pigi village.

The 2/11th Battalion (Major Sandover) occupied the ridge from the Wadi Adhele to its western end at Hill “B” with three companies forward facing north. Initially the role of the 2/11th was to form a reserve to the 2/1st Battalion in defence of the airfield. One company was held in the

rear ready to reinforce the 2/1st if required; the battalion’s reserve was the transport platoon. On Hill “B” which jutted towards the sea, were also two 100-mm guns and one platoon of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion (Lieutenant McKerrow)3 less one section at the eastern flank of the battalion near the Wadi Adhele. The two tanks were stationed under olive trees in the Wadi Pigi, whence they could issue forth to counter-attack if an enemy force obtained a foothold on the landing ground. The infantrymen were in weapon pits under olive trees or otherwise concealed so that they could be seen from neither the ground nor the air. Proof of the effectiveness of the camouflage – and guidance in improving it – had been obtained on the 16th when a very low-flying German reconnaissance aircraft crashed near the landing ground and in it were found aerial photographs dated the 8th – before the 2/11th arrived – showing that only one of the defenders’ positions had been located. It was forthwith altered.

Campbell put the town of Retimo out of bounds because in the early days a few men on leave there drank too freely of the potent local wine, and he was rightly anxious that nothing should upset the cordial relations with the Cretans. Small parties of provosts were placed in Retimo and all the villages.

At 9 a.m. on the 20th the troops at Retimo saw fourteen fat troop-carrying aircraft approach the airfield but wheel right towards Canea. The long-awaited assault had begun. At 12 o’clock twenty troop carriers flew east past Retimo towards Heraklion. At 4 p.m. about twenty fighters and bombers arrived over Retimo and bombed and machine-gunned the area round the airfield. It was evident the camouflage was so thorough that the air crews could see no definite targets, and only two or three men were hit. However, the raw 4th Greek Battalion, although no bombs had fallen in their area, began moving back up the ridge. Australian NCOs were sent from the left of the 2/1st and right of the 2/11th, and they steadied the Greeks, led them forward to their original front line and stayed with them there. (One of these NCOs, Corporal Smallwood,4 not only led the Greeks back to their positions but later took forward a large patrol of them to the main road capturing some twenty prisoners.)

After this ineffective strafing had continued for a quarter of an hour, twenty-four troop-carrying aircraft appeared. They came from the north towards Refuge Point, some miles to the east, then turned west, flying parallel to the coast, slowly, at about 400 feet. Other groups of troop carriers followed until 161 had been counted. One force of paratroops jumped when they were east of the airfield and floated down in an area three miles long and half a mile wide from east of the Olive Oil Factory to the eastern end of the airfield. A second force landed in sections along the coastal shelf from the western end of the airfield to the outskirts of Retimo itself. The landing was completed in thirty-five minutes. The

Situation at Retimo

slow-flying, flimsy transport aircraft were a relatively easy target, and every weapon on the ground blazed at them as they passed across the front at a range of little more than 100 yards. Seven troop carriers and two other aircraft were shot down, most of them crashing in flames near Perivolia at the western end of their run. Other aircraft were on fire as they flew homewards.

On Hill “A”, the vital ground overlooking the eastern end of the air-field, a considerable number of paratroops landed right on the closely-defended area – a hill about 200 yards by 300 – held by one company of infantry (Captain Channell’s5), six guns and four Vickers machine-guns. There followed a bitter series of fights between sections or platoons of Australians on the one hand and, on the other, such groups of paratroops as survived long enough to organise and go into action. On the east of the line paratroops landed on top of one platoon of infantry, the 75-mm guns, and the two Vickers guns, under Lieutenant Cleaver.6 Crew after crew of the Vickers guns were shot down, and the guns were finally put out of action by a German mortar bomb. The surviving gunners of the 75’s, who had no small arms except three pistols, withdrew to the battery headquarters farther up the ridge, carrying their breech-blocks with them. There they fought on, using some captured weapons, and held their positions until a concerted German attack about 9 p.m. Of the crews of the remaining two machine-guns farther west, few survived, but three isolated infantry posts still held out on the northern slopes, and the remainder of Channell’s company was across the neck of the hill. Campbell sent two platoons (Lieutenants Craig7 and Kiely8) from his central company, which was not engaged, to prevent the Germans from advancing west from Hill “A”, and they moved across the Wadi Bardia under fire. Although the Germans possessed most of the top and eastern side of “A”, it was dangerous for them to advance out of the vineyards and down the western slopes because they were under observed fire from Captain Travers’ company on the spur west of the Wadi Bardia. Campbell also sent a platoon to reinforce Channell on Hill “A” and to clear the vine-yards on the north-west side of the hill. This platoon reached Channell’s headquarters about 6.30 but was unable to advance across the north-west slopes, where paratroops were now firing from excellent cover among the vines and terraces. During this fight, because so many of the paratroops had landed in the midst of the defenders, the supporting German aircraft at first were helpless and flew round looking for targets on which they could fire without endangering their own men.

Meanwhile, at 5.15 p.m., Campbell had ordered the two tanks to advance down the Wadi Pigi and swing right across the airfield and then along the road to attack the Germans east of Hill “A”. However, one tank stuck

in a drain on the north side of the airfield and the other, after passing east of Hill “A” and firing a few shots, fell into a wadi eight feet deep.9

Farther to the left the few paratroops who landed in front of the main body of the 2/1st Battalion and the 4th Greek Battalion were soon all killed or captured, as were the few who came to earth within the 2/11th’s wired area on Hill “B”. Other groups came down among the vineyards north of the 2/11th under a searching fire and were killed or forced to seek cover among the vines and huts before they had time to organise.10 Many Germans were dead when they landed. In one party of about twelve who descended compactly between two sections on the left of the 2/11th, every man had been riddled with bullets as he floated down. However, strong parties, estimated at 500 by Captain Honner, commanding the left company, were seen moving westward toward Perivolia beyond the range of the West Australians’ machine-guns.

Sandover ordered a quick northward advance along his whole line to mop-up the Germans on the low ground before dark. There was considerable opposition in places and by nightfall the main road had not been reached at all points along the front. While daylight lasted the West Australians had the advantage of overlooking the enemy, but after dark the enemy, concealed in the vineyards, could inflict disproportionate casualties on the patrols. Sandover decided to withdraw his companies within the wire for the night, but to send out patrols, particularly on the left, to stop the Germans moving towards Retimo. By 10.30 p.m. the battalion had collected eighty-four prisoners and “a mass of captured arms”. The night patrols had difficulty in finding the scattered Germans hiding among the vines and terraces, but only a few were believed to have escaped from the area which was combed. Sandover, who could speak German, questioned the prisoners, most of whom expressed the comforting opinion that no more paratroops would be landed. He also translated a captured code of signals and, as a result, his men next day laid out on the ground the sign calling for mortar bombs, and a German supply aircraft obediently dropped some.

On the first evening Campbell, unaware of what was happening elsewhere on the island and knowing that the Germans controlled most of the vital Hill “A”, sent a request to General Freyberg, by wireless, for reinforcements11 and, at dusk, issued orders for two attacks at dawn next morning, the 2/1st to clear the enemy from Hill “A”, and the 2/11th to clear them from the low ground between it and the sea, each Australian battalion being assisted by one Greek battalion which would strike north against the southern flank of the German force opposing each Australian battalion. With the eastern Greek battalion Campbell sent his second-in-

command, Major Hooper,12 while Major Ford13 of the Welch Regiment, who was liaison officer with the Greeks in this sector, was to accompany the western force.14

However, during the night the Germans on Hill “A” anticipated such an effort so far as it affected their position by pressing forward against the remaining Australian posts on that hill. They overran one section of the isolated platoon, the remainder of which withdrew on to the company headquarters. The Germans advanced on to the airfield and captured the crews of the stranded tanks; most of these Germans withdrew by dawn, but about forty remained behind the bank of the beach. Thus at dawn, when the attack was to begin, only one section of Channell’s company (Corporal Johnston15), though surrounded and overlooked by Germans, was still holding out, very gamely, on the forward slopes of the hill; the remainder of the company, now reinforced by two additional platoons, was across the neck of Hill “A”.

Channell led his men into the attack at dawn, the plan being to move round the sides and over the top of the hill. It appeared to the Australians that the Germans had arranged to attack almost simultaneously and under an intense barrage of mortar bombs. Into this fire Channell’s men advanced 60 to 100 yards; Channell and Lieutenant Delves16 were wounded, and the company was driven back until it was clinging to a line on the western edge of the neck of the hill.

Captain Moriarty’s company and the carrier platoon (though without carriers) arrived about 6 a.m. from Hill “D” to give support if it was needed and found that the attack had failed. Thus at 6.15 there were at the neck of Hill “A”, where Moriarty took over command, the survivors of nearly half of Campbell’s battalion; and the Germans were pressing hard. Moriarty telephoned to battalion headquarters that the position was “very desperate”, whereupon Campbell led one of the companies still in hand along a sheltered route across the Wadi Bardia, and leaving part of it round the wadi, took the remainder on. He reached Moriarty about 7 a.m. and ordered him to manoeuvre the enemy off Hill “A” as soon as possible. About this time the Australians were cheered to see a German bomber drop six bombs on the German front line on the neck of Hill “A”.17

Moriarty organised his force – now including platoons from four companies – into four groups and, about 8 a.m., attacked northwards. The attack was carried out with dash and succeeded brilliantly. On the right Lieutenant Rogers with four platoons (including the pioneers and the carrier crews) advanced along the eastern slope of the hill, then turned

east down the slope, took twenty-five prisoners and moved on to the hill east of “A”, while one of his platoons under Lieutenant Savage18 advanced north to the road. In the centre Lieutenants Whittle19 and Gilmour-Walsh20 (each with two platoons) advanced and occupied the eastern and northern face of Hill “A”, recapturing the 75’s. On the left Lieutenant Mann21 moved round the terrace on the west of the hill and, having taken thirty-four prisoners, joined Savage on the road. Meanwhile Lieutenant Craig in the Wadi Bardia also moved forward to the main road. The Germans who survived escaped round the spurs south of the road to the shelter of the beach. Thus, eighteen hours after the landing, the one German force that had succeeded in occupying a height commanding the airfield had been driven off, and only scattered parties of paratroops survived in the six miles of coastal plain between Perivolia and Hill “A”. However, some of these surviving groups, though small, were enterprising and aggressive. Early on the 21st several of them filtered round the rear of the Australian positions and one, twenty strong, entered the dressing station at Adhele, ordered the men there to surrender and then moved on north towards the 2/11th, but were rounded up there by a party of West Australians. Two of these Germans were killed while changing into Greek uniforms. Other Germans, moving east behind the 2/11th, pushed on through Pigi and thence down the road towards the aerodrome. They captured Lieutenant Willmott,22 whom Campbell had sent to stir the Greeks on the east into action, but the captors were themselves ambushed and captured by the engineers and transport sections, and Willmott was released.

During the day the 2/1st and 2/11th cleared the few remaining Germans from the coastal plain between Hills “A” and “B”.23 These enemy

parties were under fire from the Australians’ machine-guns above them and had been pinned down behind such cover as the low ground offered. Among the prisoners taken by the 2/11th was Colonel Sturm, commander of the whole German force. He carried his orders with him, and from these it was learnt that the plan had been to land one battalion of his regiment east and one west of the airfield, about 1,500 men in all. (By error two companies intended for dropping west of Hill “B” had been dropped east of Hill “A”.)

Of the Greek battalions sent to each flank, the one accompanied by Major Ford reached the ridge south of Perivolia by nightfall on the 21st, but round Perivolia the Germans had collected in considerable strength, though they were loosely contained by the 2/11th on Hill “B” and by the Greeks in the hills to the south and the sturdy force of 800 Cretan police who had ejected all Germans from Retimo and were astride the road between the town and Perivolia. The 2/11th was not aware that Greeks would be moving west, and there was an exchange of fire between the westernmost Australian platoon and a Greek force. The other Greek battalion, on the right, cleared small parties of Germans from the village south of the Olive Oil Factory, but by night had not reached the crest of the ridge there whence they could have threatened the Germans on the coastal plain below. Campbell relieved Channell’s battered company on Hill “A” with Captain Embrey’s. His field gunners, now plentifully supplied with German small arms, were back at their guns. He sent a message to Freyberg’s headquarters reporting that the situation was well in hand.

However, although the airfield and the positions commanding it were secure, two strongly-established groups of Germans remained, one on the east, in and round the Olive Oil Factory, astride the road to Heraklion; the other at Perivolia across the road to Suda Bay. Campbell ordered that on the 22nd each of these should be driven out. The 2/11th was to thrust west towards Perivolia, and two companies of the 2/1st east towards the factory. Near the factory the advancing Australians were joined by the Greeks from the south and found Germans strongly ensconced in the thick-walled buildings there. Moriarty’s company, advancing along the ridges, made good progress and Campbell ordered an attack about 10 a.m. if fifteen minutes’ artillery bombardment by Captain Killey’s24 guns on Hill “A” seemed effective. The guns fired what ammunition Killey considered they could afford, but already the gallant Moriarty, while reconnoitring, had been shot dead by a German rifleman, and Lieutenant Savage – the only other officer of his company – had been wounded. The attack did not start.

Campbell then planned a converging attack, to be made at 6 p.m. after artillery and mortar bombardment: 200 Greeks would move secretly down one wadi and forty Australians would crawl down another, and then charge, while the remaining troops of Captain Travers’ company fired down into the factory from the heights overlooking it 100 to 200 yards away.

However, the Greek troops did not move at the appointed time, though the forty Australians, gallantly led by Mann, rushed forward with a yell from their wadi. Many fell, and the survivors took shelter behind a bank about 40 yards from the factory. Campbell, who was near by, called to Mann not to move until the Greeks attacked. Corporal Thompson25 shouted back that Mann had been seriously wounded26 and that he (Thompson) was now in command of the few men who remained. Campbell then decided that the attack could not be pressed, and ordered the Greeks to keep the factory under fire but not to advance. At dark, when the Australians, pinned down near the factory, were able to withdraw, he sent his two companies back to their original positions overlooking the airfield, leaving the Greeks to contain the Germans in the factory.

On the left the last of the small parties of Germans in the rear of the 2/11th withdrew during the night and in the afternoon the left flanking company (Captain Honner) advanced without opposition through Cesmes to the wadi through Platanes, where they came under fire from houses farther west. On previous days the West Australians had used German signals to mislead the enemy, and now, just east of the Wadi Platanes, Honner laid on the ground a signal calling to German aircraft for bombs on Perivolia, and the German aircraft obeyed.27 Sandover ordered Honner to advance astride the road to the creek west of the road fork at Perivolia. Honner’s men, supported by a captured German mortar and one of their own, attacked and occupied the group of houses on the small ridge about half way to the objective with a loss of one man killed and two wounded. Beyond the houses the land sloped downwards and further advance would be observed by the Germans, strongly established 1,000 yards ahead on the edge of Perivolia in buildings, behind stone walls and in the Church of St. George, whose churchyard was surrounded by a stone wall, and which overlooked the ground across which the 2/11th was to attack. His 100 men were under fire from mortars, machine-guns and light artillery.

It was then late in the afternoon and when a runner arrived to report that Captain Jackson’s company was moving forward to support him, Honner (who was the senior company commander of the battalion) decided to make a leap-frogging attack in the darkness with both companies between the road and the coast, where three parallel ditches spaced at intervals of a few hundred yards and about two feet deep offered some cover. As the light faded Jackson advanced to the second of these without difficulty. Honner was following with his own company when Sandover arrived. Sandover understood that the Greeks were about to attack the Church of St. George. This seemed to him to be a vitally-important position,

but he was anxious to avoid a further unfortunate clash with the Greeks. The volume of German fire made it appear doubtful whether a frontal attack would succeed across the open ground ahead, and he ordered the two companies to remain where they were and dig in. They heard much noise and shooting around Perivolia. It appears that, in the night, the Greeks advanced, captured some prisoners, and withdrew.28

On the 23rd Campbell received an encouraging wireless message from General Freyberg: “You have done magnificently”; and later in the day came word that a company of the 1/Rangers was advancing from Canea to clear a way through Perivolia. It will be recalled that, before this news arrived, Campbell had sent off Captain Lergessner westwards with instructions to carry a message to Suda; he was also to take a mule train to Retimo to collect food. Lergessner could not get the mules over the steep hills but he himself scrambled to Retimo where he met the company of the Rangers, and (as noted above) failed to dissuade them from attacking.

When mopping-up east of the airfield, the Australians had captured the paratroops’ medical aid post and, on 23rd May, the medical officer of the 2/1st arranged with the German medical officers, first, that these should remove their wounded from the aid post in no-man’s land west of Stavromenos to the Australian dressing station in the valley near Adhele, where henceforward Australian and German medical officers and orderlies worked side by side;29 and, second, that there be a three hours’ truce so that both sides could collect these and other wounded lying between Hill “A” and the factory. About half an hour later Captain Embrey led in a blindfolded German officer from the factory with a message demanding that the Australians surrender, on the grounds that the Germans had succeeded at the two other landing places and the Australians’ position was hopeless. Campbell refused and punctuated his decision by spending a few more of his precious shells on the factory when the truce was over.

On the left the Greeks promised Sandover that on the 23rd they would drive the Germans from St. George’s Church. Accordingly during the morning the West Australians shelled the church with a captured anti-tank gun until the Germans abandoned it; but the Greeks failed to follow up. That afternoon about fifty German aircraft appeared and, evidently obeying signals from the Germans in Perivolia, attacked the area between that village and Platanes for five hours. Jackson’s company, nearest the

Germans, escaped with nine casualties,30 but Honner’s and the mortar platoon next to them lost three men killed and twenty-seven wounded. Where the bombardment was hottest Privates “Slim” Johnson31 and Symmons32 kept a Bren gun in action though both were wounded, and refused to move to a safer position where they would have a less clear view. For a time the aircraft circled round setting fire to houses and crops. At sunset the Germans on the ground attacked from Perivolia, but were beaten off. “Our forward troops,” wrote an Australian, “stood up and shot them down like rabbits.” When the attack was over the survivors of Honner’s company were replaced on the left by Captain McCaskill’s, which made ready to attack with Jackson’s as soon as the Rangers appeared, but nothing was seen or heard of them.33

The reoccupation of Hill “A” and the coastal plain had placed Campbell again in possession of the two tanks. Carrier crews of the 2/1st found that they were undamaged and discovered how to drive them. At dawn on the 24th one tank thus recovered by the efforts of Lieutenant Mason of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps was used to reconnoitre the Olive Oil Factory, and later in the morning Mason drove it along the road past the factory to a house where Germans had been collecting. The Germans sheltered in the house and remained there.

That night Campbell guided this tank to the road junction west of Hill “B”, and just before dawn handed it over to Sandover to support a new attack towards Perivolia. The tank moved forward at first light on the 25th but a Blenheim aircraft flying low overhead alarmed the inexperienced driver and caused him to blunder over a culvert into a creek. It was hastily camouflaged to hide it from patrolling aircraft and rescued towards evening. Next morning (the 26th) it again advanced towards St. George’s Church, but when it was nearing the objective a German shell hit the turret, jamming it and stunning the commander (Lieutenant Greenway34) and again the attack was abandoned.35

Meanwhile the 2/1st, using a captured mortar, had, on the 25th, bombed some thirty Germans out of the house on the extreme right. This greatly heartened the Greeks, who forthwith occupied the house, but the Germans in and round the factory were well armed and aggressive and kept the Australian gunners under heavy and accurate mortar and machine-gun fire. At 9 o’clock on the 26th, hearing that this fire had diminished, Campbell sent a tank and a platoon of Embrey’s company to explore. Embrey himself led the infantry which reached the outskirts of Stavromenos, covered by the tank and by fire from the 75-mm guns on Hill “A”. Having gone so far without meeting opposition he decided to attack, and the artillery fire was stopped as he and his men jumped the wall and captured the factory, taking forty-two wounded and forty unwounded Germans. From these they learnt that at 3 a.m. the three surviving officers with thirty men had made off eastwards.36 There were now 500 German prisoners penned in a cage under the southern side of Hill “D”.

Since the invasion began Campbell had received from Freyberg’s headquarters only such news as could be sent to him by wireless in clear language, and he knew that if any secret plans were proposed – an embarkation, for example – news of them would have to be sent to him by other means. On the 26th Lergessner arrived from Canea, bringing the first news of the failure of the Rangers on the 24th; but he added that there was no talk of evacuation at Force headquarters.

The second tank was now in working order and, during the night of the 26th–27th, Campbell guided it to Sandover to support yet another attack towards Perivolia, this time by two companies. Before daylight Honner’s company, only sixty strong until reinforced by some transport drivers, and that of Captain Gook37 (who had succeeded McCaskill), had moved stealthily forward to the farthermost ditch, only 75 yards from the German positions, and there waited for the tanks to arrive. At dawn the two tanks appeared, each commanded by an Australian infantry officer. Lieutenant Lawry’s38 on the left was near the German line when it was hit by a shell and set on fire. The crew of the other (under Lieutenant Bedells39), unaware that the infantry had crawled to the farthermost ditch, opened fire in the dim light causing two casualties. The infantrymen had to wave signals back to the tank and thus betrayed their presence to the Germans. Thirty yards beyond the ditch the tank struck a land mine which knocked off a track. It lurched on for a few yards and was bogged in sand. A mortar bomb blew the top of the turret open and as Bedells was trying to close it a second bomb severed the fingers of one hand and a third disabled his guns, which had been kept in action to the last.40 Lawry and one of his men, wounded and scorched, crawled back to safety. Bedells and his crew remained in the tank until nightfall.

Honner had just decided that with both tanks out of action it would be useless for the infantry to attack, when Gook wormed his way into the ditch and announced that his forward platoon (Lieutenant Roberts41) could not be found. After further reconnaissance Gook returned to say that the missing platoon must have attacked and broken into the Perivolia position. In an account written after the campaign Honner described what followed:

That left me only one thing to do – attack to help Roberts out of trouble or to complete the success he had started. I knew I’d have to lose men but I couldn’t lose time. A section from 14 Platoon – nine men – was ordered to move to a low stone wall fifty yards ahead round a well about twenty-five yards from the German line, to cover with Bren fire our attack across the open. They raced along the low hedge to the well. The leader, Corporal Tom Willoughby,42 was nearly there before he fell. The man carrying the Bren went down. Someone following him picked it up and went on until he was killed, and so the gun was relayed until it almost reached the well in the hands of the last man, and he too was killed as he went down with it. Eight brave men died there – Corporal Willoughby, Lance-Corporal Dowsett,43 Privates Brown,44 Elvy,45 Fraser,46 Green,47 G. McDermid,48 and White.49 The ninth man, Private Proud,50 was hit on the tin hat as he jumped up, and fell back stunned into the ditch. As the first man fell a stretcher-bearer dashed out, went down beside him, saw he was dead, decided that the others were probably dead also, and lay there until rescued an hour or so later. Then we tried the other side. Lieutenant Bayly51 headed a party (along a forward leading tributary of the ditch) but he was the only one in the leading group not hit. Private “Blue” Pauley52 was hit here and so was young Fitzsimons53 who had been wounded on the 23rd but got away from the dressing station to rejoin his company when he heard it was going into action again. This time he was stopped with hits in the arm, chest and legs. Gook’s runner was also hit; and then Gook came along the ditch from the left to say Roberts’ platoon was lying doggo along the far end of it. I wrote a hurried report of the situation. ... Snipers occupied the houses overlooking us and it seemed that it would be difficult to leave the ditch but safe to stay all day (to protect the tank crew). Everyone leaving the ditch since daylight, except the stretcher-bearer, had been hit, but I wanted to get my message back and I wanted to direct the putting down of smoke (we had none) to cover a party to bring in our wounded (we did not know they were dead).

Honner decided to carry the message back himself, reasoning that there was no need for him to remain now that the attack had ceased; and he was anxious to receive fresh orders personally. He tied the message to his wrist and arranged for two men to follow him at intervals of five minutes to ensure that the message went through. Under hot fire from Perivolia Honner “crawled, wriggled, rolled and zigzagged” across the half mile of open country between the ditch and the nearest houses unscathed; the two who followed him – Warrant Officer Anderson54 and Private Donaldson55 – were both hit.

No smoke was nearer than three miles away (wrote Honner) so the R.M.O., Ryan,56 who was at the houses [after consultation with Sandover] decided to go out again with a Red Cross flag. Out he marched with his stretcher-bearers using the German light-running, wheeled stretchers--and the enemy ceased firing while he made his half-mile march forward, a bit doubtful whether the Germans would allow him as close to their trenches as our casualties were. He found Willoughby’s men all dead ... looked into the German line and saw it bristling with machine-guns as they waved him away; and brought back our wounded.

As the loss of the two tanks and the shortage of artillery ammunition made a successful daylight attack against Perivolia impossible, Campbell ordered Sandover to assault the village that night.

By this time the 2/11th had exhausted its mortar ammunition and many men were using captured small arms. Sandover planned an attack by two companies astride the road leading into Perivolia from the south-east. Captain Jackson’s was to capture the crossroads and exploit to the sea; Captain Wood’s to seize the houses east of the road junction and, when it could, to exploit boldly. Lieutenant Royce’s57 platoon was to follow Wood and guard his left and Honner and Gook were to carry out offensive patrols on their own front and attack machine-gun posts on the right, but to with-draw from this exposed position at dawn.

Jackson’s company set off in the darkness at 3.20 a.m. on the 28th, but had not gone 400 yards when Greeks opened fire on St. George’s, despite a request that they should not fire during the advance Immediately the head of the Australian column came under heavy fire at short range. However, the company pressed on, gained the crossroads and penetrated along the wadi towards the sea. Wood’s company advanced and bombed the houses on the main road, but ran into heavy grenade and mortar fire which wounded Wood, and two platoon commanders, Lieutenants Bayliss58 and Lee.59 The responsibility had been placed upon Wood of deciding

whether the attack could continue or not. At 4.33 Lieutenant Scott,60 the only unwounded officer, on the orders of Wood, who lay mortally wounded, fired two green Very lights – the signal that the company was withdrawing, and repeated the signal a few minutes later.

The depleted companies to the east of Perivolia were now caught by machine-gun fire on fixed lines.61 They withdrew before dawn, but of Wood’s company only forty-three came back.62

Some of Jackson’s men told him that the signal to withdraw had been fired, but neither he nor any of his officers had seen it and he decided not to act on the reports, thinking that perhaps a German signal had been seen. It being then too late to withdraw under cover of the darkness, he decided to occupy houses in Perivolia west of the crossroads and behind the German line, and remain during daylight on the 28th.

There were no Germans in the houses they occupied, although they found signs that some had departed not long before. Soon after dawn a German ran into one house and was captured.63 An enemy anti-tank gun shelled another, causing the platoon in it to withdraw to a third.

Early in the afternoon the enemy severely bombed one house but no attack followed; all the occupied buildings were kept under frequent machine-gun fire from St. George’s Church and the seaward flank, but although the walls were perforated and men were half-choked with dust, none was hit by this fire. Jackson decided to withdraw after dark not west or south, as he thought the enemy would expect, but along the wadi to the beach and thence break through the enemy line eastwards along the beach. Jackson had no means of communicating with battalion headquarters, but that headquarters could assess where he was by the firing which had gone on all day. Sandover judged that he would try to break out in the darkness, and, accordingly, the artillery opened fire on the forward German posts as soon as it was dark – and used up most of its remaining ammunition on this task. About 9 p.m. Jackson’s company moved off with one wounded man on a stretcher and others walking in the middle of the column. They reached the beach undetected and moved along it crouching until the leaders neared a wrecked aircraft which the enemy used as a strong point. There two machine-guns opened, and the Australians took cover by lying in the water under shelter of a slight bank.

After a quarter of an hour this fire ceased. Jackson decided that he would lose many men if he continued to advance eastward with enemy machine-guns on his flank; he would therefore turn about and withdraw through the rear of the German area. They moved west, coming under fire only once, until they reached the outskirts of Retimo where, now extremely weary, they took shelter in a large villa for the night. Next morning two of the wounded, including Sergeant Hutchinson,64 who afterwards died, were too ill to move, whereupon Jackson left them at the villa with a medical orderly, Private Whyte,65 and one other man who was to seek medical aid from Retimo; the others crossed the road, bringing their prisoner with them, moved into the foothills and circled round the south of the German area, reaching their battalion about midday on the 29th. Of some seventy men who had gone into the attack about twelve had been wounded.

After the failure of this attack, Campbell decided that he had not enough men to risk another thrust against enemy troops who were so far from the airfield, the protection of which was his main task. It was on the night of the 2/11th’s attack (27th–28th) that the lighter arrived from Suda Bay under Lieutenant Haig, carrying two days’ rations for the Retimo force. Haig, who was known to the force at Retimo, having ferried supplies there before the attack, had orders to march across country to Sfakia after delivering the rations; but it will be recalled that he had left Suda before receiving Freyberg’s message to Campbell that the whole force was to withdraw. When Freyberg asked Cairo to have a message dropped to the garrison, the following was written:

We are to evacuate Crete. Commence withdrawal night 28-29. Leave parties to cover withdrawal and deceive enemy. If liable to observation move only by night and lie up by day. Embark Plaka [Plakias] Bay east end night 31st May-1st June. Essential place of embarkation be concealed from enemy and therefore you should be in embarkation area and concealed by first light 31st May. Make best arrangement you can for wounded. Most regrettable we can do nothing to help you in this respect. Hand prisoners over to Greeks. You and your chaps have done splendidly. Evacuation is due to overwhelming enemy air superiority in this sector. Cheerio and good luck to you.

On the 28th aircraft dropped some cases of food and ammunition at Retimo and may have dropped this message too. If so it was not picked up. On the 29th, presumably in the dark, a slang message understandable by Australians, was dropped to the Retimo force ordering the garrison to fight its way out to the south coast.66 Later a second message was sent – the Hurricane that carried it did not return. None of these missives reached the force at Retimo, where no friendly aircraft appeared in daylight after 25th May. The No. 9 wireless set at Retimo was working perfectly on the 28th and 29th but the sets at Freyberg’s headquarters appeared to have gone off the air.

After dusk on the 29th Major Hooper, who had been with the Greeks on the eastern flank, reported to Campbell that the Greeks declared that a large German force was advancing from the east – the direction of Heraklion. Soon afterwards the Greeks learned that Maleme and Heraklion were in German hands and the four Greek battalions began to withdraw into the mountains. Having received no permission to leave his post, Campbell at once ordered the whole of the 2/11th to occupy the position the 4th Greek was abandoning, but at Sandover’s request he agreed that one company (Honner’s) be left on the ridge overlooking the Germans in Perivolia, and that the artillery be left on Hill “B”. German light artillery began ranging on the Platanes road junction in the late afternoon. At midnight Greeks brought news that Germans were arriving from the west and that 300 motor-cyclists had entered Retimo.

Campbell’s only source of news from outside his own area was now the BBC, which announced that the situation on Crete was “extremely precarious”. There was only enough food to last one more day. In the hope that naval vessels would arrive and remove his force, Campbell had ordered the patrol that policed the beach at night to signal the letter “A” out to sea every twenty minutes, but there had been no reply. Next morning at 6 o’clock Honner’s company, again on the left flank watching Perivolia, reported that they could hear what sounded like many motorcycles, warming up beyond Perivolia, and that the ridge they held was under artillery and mortar fire. About 9.30 three tanks appeared on the left of the 2/11th followed by a procession of about thirty German motorcyclists, accompanied by some light field guns. A little later Campbell

was informed that German tanks were behind the 2/11th and in the valley behind Hill “D”.

Campbell decided that he could now carry out his task – to deny the airfield to the enemy – for only an hour at the most and only at heavy cost. The fact that Lieutenant Haig had been ordered to Sfakia suggested that Sfakia was the embarkation point; it was three days’ journey away and his force could not possibly reach it. His men had been on half rations for three days and now had food only for that day, and it seemed to him unfair to make for the mountains and rely on the Cretan villagers to feed so large a force, specially as the Germans had dropped leaflets threatening to shoot any who helped the British. “The only hope,” he wrote later, “would be every sub-unit for itself, which would, I knew, result in many being shot down, because, though olive trees are excellent cover from aerial observation, their widely dispersed bare trunks offer little protection against ground observation. I considered that the loss of many brave men to be expected from any attempt to escape now, and the dangers and penalties to which we must expose the Cretan civilians, were not warranted by the remote chance we now had of being evacuated from the south coast.”

Campbell told Major Ford and Major Bessell-Browne,67 his artillery commander, that he proposed to surrender, and they agreed. He then telephoned Sandover, told him that further resistance would result in useless waste of lives and asked his opinion. Sandover, who had not heard that the Germans were advancing from Heraklion, asked whether there was news from there, because, if Retimo surrendered, the Germans advancing from the west might surprise the force at Heraklion. Campbell said that he thought “the show had packed up there”. Sandover said that he pro-posed to tell his men to destroy their arms and make for the hills During this conversation heavy fire was being exchanged between the German force and Honner’s company blocking the road from Perivolia.

With his company only some forty strong Honner had been ordered, on the evening of the 29th, again to take over the position on the western ridge; he was given some men of the anti-aircraft platoon under Lieutenant Dundas68 to increase his numbers. As Sandover had ordered him to with-draw if attacked by overwhelming forces, Honner left his group in the Platanes wadi, with a Bren gun guarding the bridge, to cover his line of withdrawal. The remainder – his headquarters men, one platoon of twelve men under Corporal Cunnington,69 and the anti-aircraft men under Lieutenant Dundas – he led forward to the ridge and deployed in the houses and between these and the sea. When the German tanks and infantry attacked after an hour’s bombardment, Corporal Young70 and three

men posted on the road on the left flank held their fire until the tanks were close, then blazed at them with their Bren gun so fiercely that the tanks swerved off the road on to the hillside to the south where a line of motor-cycle machine-gunners were now pouring fire into the Australian position. The Germans began to advance south of the road towards the Wadi Platanes. Seeing that he might be cut off Honner ordered a withdrawal, led his headquarters and the anti-aircraft men east along the beach and ordered Cunnington to fight his way back to the remainder of the company; this they did “leap-frogging in perfect tactical style, one group blazing at the Germans (who were held on the hill south of the road) while another streaked past to the next patch of shrubbery”. After Cunnington’s men reached the Wadi Platanes the whole company withdrew through the dust and smoke of the bombardment by artillery, mortars and machine-guns.

When Honner at length reached battalion headquarters Sandover was conferring with the other company commanders, having just spoken to Campbell on the telephone and told him that he was in favour of making for the hills The spirited resistance offered by the handful of men in the Platanes-Perivolia road had delayed the enemy advance but two tanks were approaching the front of the battalion; those men who still had ammunition were firing at them. Sandover instructed his officers

that all men should be told there was no known chance of rescue nor source of food, and then be given the choice of surrendering or going. If they wanted to go they’d better go quickly as the back road might be cut.

He added that the sector commander had been informed of this and had wished them good luck. “I am going myself,” said Sandover, “we’ll think what to do when we get out of this.” The battalion area was now under heavy fire from the tanks – although most of it went over the heads of the forward troops. The German gunners were shouting: “The game’s up, Aussies!”

Major Heagney,71 the second-in-command of the battalion, who, though still in poor health, had managed to rejoin the battalion from hospital, and a number of other officers decided to remain Sandover then left with a party of officers and other ranks. This group halted in a gully behind the Greeks who were concentrating south of the Adhele road. Here others, including Honner, caught up.

My party (Homier wrote) must have been the last organised group to leave the battalion area. It included three men wounded in the morning fight and we were joined by Private Shreeve,72 wounded in the arm eight days earlier, who left the dressing station with his arm in a sling to be with us. When we caught up the main body I found I was the only man with a map – a Greek map and it was our standby for the next three months.

Among those who arrived at this stage was Lieutenant Murray,73 whose pioneer platoon had been working in Retimo when the attack opened and who had led it back through the hills to the battalion. While in Retimo he had heard a naval officer speak of landing craft at Ayia Galini on the south coast. Sandover distributed regimental funds and a few biscuits and the men then split into two main groups, one led by himself and one by Honner.

Campbell on Hill “D” had ordered Lergessner to make a white flag and display it, and at the same time he sent messages by telephone or by runner to all units and sub-units informing them of the surrender and telling them to display white flags and assemble at the north-west corner of the airfield. A quarter of an hour later, as the German fire continued, he himself tied a towel to a stick and walked down the track towards the airfield. At the time of the capitulation some 500 German prisoners, including their force commander, were held by the Australians, but were then liberated. The Australians had lost about 120 killed;74 but some 550 Germans had been buried and it was believed that their total loss considerably exceeded that number.

As the defenders had learnt when Colonel Sturm was captured, the German force that attacked Retimo consisted of the 2nd Parachute Rifle Regiment with two instead of its normal three battalions. Its task was to capture the harbour and landing ground. Sturm, a paratroop leader of 52 years, who had commanded the regiment in the attack at Corinth, divided his force into three groups. Major Kroh with the I/2nd Battalion less two companies, but with a machine-gun company and heavy weapon detachments added, was to land east of the airfield and capture it; Sturm and his headquarters would come down with one company and two platoons between the airfield and the Wadi Platanes; Captain Wiedemann with the III/2nd Battalion, two troops of artillery and a company of machine-gunners would land between the Wadi Platanes and Perivolia and take Retimo.

Major Kroh’s battalion was landed on the coastal plain east of the airfield except for himself and his headquarters and one company who were put down three miles to the east, beyond Refuge Point, on ground so rocky that many men were disabled while landing. Two companies landing close to the airfield immediately came under fire from well-concealed positions on Hill “A”. All the officers of one company were killed and both companies lost very severely before the men could reach the weapon

containers. Kroh hurried west with the company landed near Refuge Point, and collected the remnants of the machine-gun company and two companies (10th and 12th) of the III/2nd Battalion which had been dropped wrongly in this area. “These elements (of III/2nd Battalion),” states the German account, “found themselves among strongly occupied enemy positions [the company of 2/1st Battalion, platoon of 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion and gunners of 2/3rd Field Regiment on Hill “Al and, fighting in small groups against superior forces, were mostly destroyed.” With this force – what was left of his own battalion and about half of Wiedemann’s – he had by about 6.30 p.m. a firm foothold on Hill “A”. He planned to attack the airfield next day.75 (It seems probable that the survivors of the German companies who clung on to Hill “A” were chiefly responsible for the success; and that the arrival of Kroh’s group only confirmed it.)

Of Wiedemann’s III/2nd Battalion only 9th and 11th Companies, the artillery troops and the heavy weapons were landed correctly. Wiedemann collected these and advanced west under “constant flanking fire from the heights south of the road”. He occupied Perivolia and thrust into the outskirts of Retimo. The German account states that he was strongly counter-attacked from the south-west and was fired on by artillery from that direction (actually there were no guns there). Withdrawing his detachments from Retimo, he organised a “hedgehog” position about Perivolia and beat off the enemy. It therefore appears that it was chiefly the Cretan police who repulsed the western battalion of the German force and confined it in Perivolia.

The escort of Sturm’s headquarters – 2nd Company of Kroh’s battalion and heavy weapon detachments – mostly jumped into strongly-held positions (those of the 2/11th), and was “completely destroyed”. Sturm himself with a few men landed north of the road and was unable to get into touch with the other groups.

At 5 a.m. on the 21st (according to the German account) Kroh on Hill “A” experienced a strong British attack from the west – the Wadi Bardia – but beat it off. (This was Channell’s attack; the starting time was actually 5.25 a.m.) About 9 a.m. he was attacked again (by Moriarty’s force), his flank was enveloped and he was forced to retire east to the Olive Oil Factory where he reorganised and beat off repeated attacks. The German account adds: “In a daring storm troop undertaking, 56 parachute riflemen captured by the British were rescued from captivity.” (It has been impossible to discover any foundation for this report.) Wiedemann’s group, though severely bombed by its own aircraft, extended its defensive position at Perivolia and repulsed “enemy counter-attacks and shock troop operations” (evidently by the 2/11th Battalion).

Thus the remnants of the III/2nd Battalion were penned in the solid houses of Perivolia, and those of the I/2nd in the equally strong Olive Oil Factory. A supply point for the troops in the factory was established on hilly ground near the coast five miles to the north-east, with a detachment to defend it against “Greek troops and guerillas” who were active there and wherever else the Germans ventured inland. (The German account does not record the expulsion of the Kroh group from the Olive Oil Factory, and the surrender of most of the survivors of that group.)

On the night of the 27th–28th a force consisting of a motor-cycle battalion, several detachments of artillery and one mountain reconnaissance detachment, commanded by Lieut-Colonel Wittman, set off from the Suda area towards Retimo. It broke the resistance of strong rearguards at Meg Khorafia but made slow progress until other mountain troops had taken Vamos. It reached Retimo on the afternoon of the 29th and, driving off strong enemy forces (Cretan police and Greek infantry) east of the town, joined Wiedemann’s group at Perivolia. That evening Wittman was reinforced by two tanks (of the II/31st Armoured Battalion). On the 30th it attacked “a strong enemy group” (actually a platoon and a few more of the 2/11th) east of Perivolia. “As the result of the artillery bombardment and of the advancing tanks and motor-cycle rifles some 1,200 Australians surrendered”; and Kroh “surrounded by the enemy at the factory” was “liberated”. (In fact, as already mentioned, Kroh and some officers and men had slipped away from the factory on the night of the 25th–26th, and the factory and the eighty officerless men remaining had been in Australian hands since the 26th.)

The Germans found the Australians “not in any way dispirited. They are friendly and calm and simply declare: ‘We do not want any more,’ just as if they had given up a sporting test match.” A German account records a conversation between an “excellent colonel” (Campbell) and a German major who “led the conversation into other fields” – the German cause and why kindred nations should fight. Campbell’s cool and tactful replies persuaded the ardent German that “it was hopeless; the fight must be carried to a finish; God’s iron plough, war, must tear up man’s earth before the seed of the future can grow”.76

At Retimo two highly-trained parachute battalions floated down on ground occupied by two somewhat depleted but high-spirited and expert battalions of Australian infantry, which were supported by about 3,000 Greeks, mostly ill-armed and untrained but including a fine improvised unit of 800 Cretan police. The German landing was muddled, with the result that the attacking force was in confusion early on the second day, its elderly commander and his plans captured, and a large number of his men killed or made prisoner. The surviving Germans were in two groups – one to the east grimly on the defensive, the other penned between the

left Australian battalion and the resolute Cretan police. In retrospect it seems that the afternoon and night of the 21st were critical. If on that day more coordinated use had been made of the valiant but ill-organised Greeks and the attack had been pressed, not frontally along the open road but along the foothills, the small force of Germans in Perivolia would probably have been overcome. Possibly Campbell would have achieved fuller coordination if he had set up a brigade headquarters and not, devotedly, given himself the double task of commanding both the force as a whole and his own battalion. To have overcome the Germans in Perivolia and opened the road to Suda would not have affected the out-come in Crete, but it would have enabled the Retimo force to receive news from Freyberg, and perhaps to have marched to the south coast for embarkation.

The differing responses of the two commanding officers when defeat was certain are specially interesting in view of later experiences of other parts of the AIF Campbell, the regular soldier, kept his unit together and surrendered it as an intact body of troops still under his command. Sandover, the citizen soldier, advised his men to scatter and try to escape, and as a result 13 officers and 39 other ranks of his battalion reached Egypt; it seems that 2 officers and 14 others of the 2/1st Battalion escaped. In other connections the propriety of each course of action has been discussed at length, and in any group of soldiers there will probably always be some who would approve one course and some another.