Chapter 14: Retreat and Embarkation

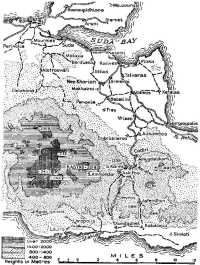

BY the morning of 28th May the force at Suda had disengaged and was already distributed along the road which climbed over the island to Sfakia. That road wound up and across Crete’s backbone, reaching a height of 3,000 feet. Some seven miles from Sfakia it passed through the upland plain of Askifou, a basin about one mile in width and two in length. Farther on, the road ended a mile and a half from the little beach at Sfakia, and thence only foot tracks led down to the sea. The task of General Freyberg’s fighting troops was to hold a series of rearguard positions astride this mountain road, along which a densely-packed column was now retreating, and finally to disengage and embark.

In the morning of the 28th General Freyberg, whose headquarters were now established in the Askifou plain, sent General Weston an order placing all troops in the western sector of Crete under his command. Freyberg informed Weston that 1,000 men were to be embarked that night, 6,000 on the 29th–30th, 3,000 on the 30th–31st, 3,000 on the 31st-1 st; the 4th Brigade was to hold a position at the northern entrance to the plain of Askifou until darkness fell on the 29th; an improvised Marine battalion to hold a position south of the plain until darkness on the 31st – the night on which the 5th and 19th Brigades were to embark. Next day the marines and Layforce were to form a final rearguard.

At dawn on the 28th the 5th New Zealand and 19th Australian Brigades, each little stronger than a battalion, were deployed along the Sfakia road from Beritiana, which was only half a mile from Suda Bay, to Babali Inn, about six miles inland. A company of Layforce and two companies of the Maori battalion were astride the road at Beritiana. The 5th Brigade was grouped round Stilos with the 23rd Battalion forward and the 21st, 19th, remainder of the Maori and 22nd echeloned behind. The 19th Brigade was about Neo Khorion, with the 2/8th Battalion astride the road leading up from Kalives and the 2/7th in rear of the New Zealanders on the Stilos road. At Babali Inn, some two miles south of Neo Khorion, was the remainder of Layforce. The two brigades were to withdraw that night.

By 6 a.m. on the 28th the Germans reached the commandos and Maoris at Beritiana and had them under fire; in two hours they surrounded these rearguard companies and were streaming past them towards Stilos. The surviving commandos withdrew through the Maoris’ positions at 11 a.m. and at 12.30 Captain Royal1 began to withdraw his Maoris. They succeeded in fighting their way back to their unit. At 6.30 the German attack reached the 5th Brigade; there it was stopped with severe loss, probably fifty being killed or wounded.

About 8 a.m. a large procession of Italian prisoners had moved along the road from the south toward the New Zealand rear carrying white flags. Brigadier Hargest allowed them through his lines in the hope that they would embarrass the enemy. When they reached Stilos they came under German mortar fire and scattered.

About 9 a.m. Hargest and his battalion commanders held a conference (which Brigadier Vasey attended) at which it was decided that their men were not fit to fight all day

and march all night, and therefore should begin to move back that day. Vasey agreed, and it was arranged by him and Hargest that, while the 2/7th acted as rearguard, the 5th Brigade headquarters (about 140 men including the band) would march south to Babali Inn and reinforce the line Layforce was holding there. The battalions would then pass through this line to Vrises at the junction of the Georgioupolis and Suda roads, where Hargest hoped to hide his men during the heat of the afternoon. The forward units thinned out and withdrew in good order, the men marching in single file on either side of the road with sections well spread out.

When the 2/8th arrived at Babali about 2 p.m. it took position with Layforce, and Hargest’s headquarters moved on to Vrises, followed by the 5th Brigade and the former rearguard, the 2/7th Battalion, which left Babali in the afternoon after having been held in reserve there for some hours. The enemy followed fast and at 1.35 p.m. attacked the Babali rearguard. Until dusk Layforce was under intermittent machine-gun fire, though, throughout the day, for the first time since the 20th, air attack was inconsiderable, probably because the German aircraft were concentrated over Heraklion.

At 9.15 p.m. this rearguard began to withdraw to Vrises. There the 5th Brigade and the remainder of the 19th had assembled early in the afternoon and thence, after a few hours’ rest, the New Zealand battalions at 6 p.m. had moved on with the intention of reaching Syn Ammondari, 12 miles away, that night. This necessitated an exacting march up hill to the top of the pass. The men were footsore and very weary. Near Cadiri

engineers blew up the road before the rearguard had passed and caused a galling delay to the infantrymen who had to make a difficult detour round the demolition. The 4th Brigade was already deployed at the entrance to the Askifou plain, the 23rd Battalion having established a covering position at Amygdalokorfi.

The 2/7th had marched back to the Askifou plain where it took position just north of Askifou village itself. It was in good heart and in perfect order. As it was marching that night, dispersed in sections on each side of the road, a German aircraft dropped a flare. Walker sent a spoken message along the column that if a flare was dropped again he would blow his whistle and every man would lie face downward off the road. The message was repeated swiftly back along the column and forward again. Another flare was dropped, the whistle blown, and instantly every face was on the ground (where they would not catch the light), every body motionless, and the flare illuminated only an empty road.

The 2/8th was now wearily marching towards the Kerates area, where it arrived about 5 a.m. Layforce followed, withdrawing to Imvros south of the plain.

According to the German report, in the morning of the 28th May, the 85th Mountain Regiment after “bloody hand-to-hand fighting” had destroyed two British “medium tanks”, captured Stilos, and “made prisoners a British battalion” [evidently a large part of “A” Battalion of the commandos]. It continued the pursuit towards Sfakia, but was held for the remainder of the day. The German commander considered that the defenders would withdraw at dusk, and decided to await this event and continue his advance next morning.

On the 27th and 28th General Ringel, not realising that the main body of the defending force was in retreat southwards towards Sfakia, had ordered the three mountain regiments to thrust eastward towards Retimo. Even on the 29th he detached only the 100th Mountain Regiment to take up the pursuit towards Sfakia while the 85th and 141st Regiments pressed on towards Retimo.

Meanwhile, round Sfakia, General Weston had been preparing for a series of embarkations. Early on the afternoon of the 28th he went to Imvros, where Major Burston2 commanded a group which included the headquarters of the 2/3rd Field Regiment and other detachments. Weston arranged that Burston should organise about 60 men of the 2/3rd Field Regiment to guide units from the top of the escarpment to the beach. Burston and Captain Forbes3 reconnoitred the escarpment and disposed their men along a track winding across the Komitadhes ravine and through Komitadhes village, and that night these guides kept the flow of traffic moving steadily to the beach.4

At Sfakia that night (the 28th) four destroyers embarked 230 wounded and 800 British troops, including the men of the air force. It was on this

night also that three cruisers and six destroyers took off practically the entire force at Heraklion. The misfortunes of the Heraklion convoy, already related, greatly influenced the decisions that followed these fine achievements. At 9 p.m. on the 28th a force consisting of the cruisers Phoebe and Perth, Calcutta and Coventry, the transport Glengyle, and three destroyers left Alexandria to embark troops at Sfakia the following night – the 29th–30th. Major-General Evetts who was to “coordinate the embarkation” – a large task for a newcomer – flew from Alexandria to Cairo on the 29th where he discussed the plans with General Wavell. After consulting also General Blamey and Air Marshal Tedder,5 Wavell informed Admiral Cunningham that he considered that the Glen ships and cruisers should not be risked, but that embarkation in destroyers should continue. Thereupon Cunningham consulted the Admiralty, recapitulated his mounting losses, but said that he was ready to continue the evacuation as long as a ship remained. The Admiralty ordered that the Glengyle be turned back but the other ships continue. However, this order did not arrive until 8.26 p.m., when the force was approaching Sfakia; Cunningham decided that it was then too late to recall Glengyle and informed the Admiralty that instead he was sending three additional destroyers (Stuart, Jaguar and Defender) to meet her and to rescue troops from any ship damaged by air attack.

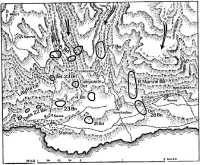

Meanwhile plans based on previous arrangements were being made on shore for the first large-scale embarkation from Sfakia. At 2 p.m., at a conference at Vasey’s headquarters, Weston ordered that the 4th Brigade, after having held the Askifou rearguard position until nightfall on the 29th, should withdraw to the beaches. By dawn on the 30th, the 19th

Brigade, comprising the 2/7th and 2/8th Battalions, with the marine battalion, and supported by two guns of the 2/3rd Field Regiment, were to occupy a final rearguard position, covered by a rear party comprising the remaining three light tanks of the 3rd Hussars and three carriers of the 2/8th. The rearguard position was near Vitsilokoumos in the hills covering Sfakia. Vasey would probably be responsible for holding this position until the night of the 31st-1 st, but there was a possibility that the embarkation would be hastened and the rearguard could embark on the night of the 30th. ‘The 5th Brigade should move to the dispersal area above Sfakia, and Layforce to Komitadhes to cover the exits of a ravine along which the enemy, by-passing the road, might approach the beach from the west.

On the morning of the 29th the 23rd Battalion was holding the entrance to the Askifou plain. At 7.15 a.m. large numbers of Germans were seen advancing towards it. The battalion had been reduced to the strength of only about a company. It had only five officers and, at the end of the day, was commanded by a lieutenant, R. L. Bond.6 The men were weary, hungry and short of water. Hargest’s brigade major, Dawson,7 solved the water problem by collecting all the glass bottles and other containers he could find in Sin Kares, filling them and sending them forward in a truck.

During the afternoon the enemy edged forward but the battalion with-drew without incident, and from Sin Kares the men were carried back in trucks, of which a few remained By 9 p.m. they had passed through the 4th Brigade’s main rearguard position on the southern edge of the Askifou plain and the 4th had begun to move back. Between 10 and 11 p.m. on the 29th, the 5th, and at daylight on the 30th, the 4th reached the end of the tarred road above Sfakia. In this dispersal area were crowds of men, chiefly base troops, who had lost their units. “The place was literally swarming with men of all sorts,” wrote Hargest later, “and nearly all (of) units who had straggled and were now at a loose end, eating up rations and using water that fighting troops needed. Down below on the sea coast it was supposed to be worse.” The lack of food and water was now crucial.

During the 29th Burston and Forbes of the 2/3rd Field Regiment had improved their traffic control organisation along the Komitadhes track and had converted it into a “sheeprace”, so that “once a man got into the flow of traffic he just could not (and was not allowed to) stop”. Later, men who dispersed in the scrub to the west of the ravine during air attack found an old track connecting Sfakia and Askifou and thenceforward a proportion of the men moving down to the beach used this track, but most of them streamed through Komitadhes.

The naval squadron arrived off Sfakia at 11.30 p.m. on the 29th. Men were ferried to the ships in the Glengyle’s landing craft (three of which she left behind for use in later embarkations) and in two landing craft carried

in the cruiser Perth. By 3.20 a.m. on the 30th about 6,000 men had been embarked, including 550 wounded, and the squadron sailed. It had been hoped to take more but the small size of the beach, the absence of an extensive dispersal area and faulty control slowed embarkation. On the return voyage the ships were attacked from the air; Perth was hit and a boiler room put out of action, but she was not disabled. Puttick and most of his staff were embarked that night. An order from Wavell to Freyberg to embark arrived in time for Freyberg to leave on the 28th, but, as in Greece, he decided that he should not go away until most of the force had been evacuated.

In the rearguard position Vasey had the 2/7th forward astride the road, the weak 2/8th holding a large wadi on the left flank, and the marines in reserve. In support were the two 75-mm guns of the 2/3rd Field Regiment under the resolute Captain Laybourne-Smith8 – these were the only guns to cross the mountains – and two machine-guns of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion under Lieutenant Bolton.9 The brigade was to hold this position during the 30th and 31st and to embark that night. Forward of the infantry and about a mile north of Imvros the three light tanks of the 3rd Hussars commanded by Major Keith covered a detachment of the 42nd Field Company which was to crater the road in four places when the tanks drew back.

At 5 a.m. the three carriers of the 2/8th Battalion under Sergeant Trethowan10 joined the tanks. The German advance-guard was attacking as the carriers arrived and one of the tanks had been disabled by a shell. A lively rearguard action followed. Keith told Trethowan that their task was to hold the enemy until 5 p.m. that day. In the pass north of Imvros, Trethowan and three men dismounted and engaged the advancing Germans until Keith ordered him to retire to the village as the enemy’s machine-gun fire outranged his. At Imvros a new position was taken up by the tanks and carriers, with two machine-guns under Trethowan forward of them beside the road. After an exchange of fire with a number of German groups, the tanks, carriers and dismounted men moved back beyond a sharp turn and took up a position on the road and on a hill above it and again awaited the Germans.

The enemy came into range with troops in trucks followed by walking personnel (reported Trethowan afterwards). They were an easy target, and the first column when fired upon scampered for cover while their trucks tore down the road and gained cover. ... The enemy began searching fire with mortars and machine-guns but failed to locate us. A column of marching troops came into range on the road soon after and we dealt with them in a similar manner.

German mortar fire at length forced the dismounted Australians off the knoll from which they had been firing, but, accompanied by a tank, they advanced again around a bend in the road and surprised and dispersed a hostile party. Thereafter the enemy ceased to advance along the roads but moved over the hills on the west, whence he fired on the rearguard. At 4 p.m. orders arrived to go back to the beach. In the withdrawal along a road now swept by enemy fire from the left flank two of the little party of Australians – Sergeant Cooper11 and Private Marshall12 – were wounded. The carriers were wrecked by their crews on reaching the end of the road, after they had passed through the positions held by the 2/7th.

About 3 p.m., while this action was in progress, men of the 2/8th saw troops advancing dressed in dark jackets and khaki shorts, looking like men of the Greek air force. It was eventually decided that they were Germans and they were fired on and dispersed. A patrol identified the corpses of twenty-five Germans.13 Further patrols were fired on during the night, and next day more than 100 dead were counted. During the day German patrols, again infiltrating round the western flank, reached to within a few hundred yards of Freyberg’s headquarters; against them was sent a platoon of the 20th Battalion under the heroic 2nd-Lieutenant Upham, which silenced a machine-gun and killed 22 Germans.

Although the embarkation on the 29th–30th had taken away some 6,000 men, including many wounded (though hundreds remained), the greater part of the New Zealand Division was still in Crete. Determined to do all he could to save his men, Freyberg, still disobediently on Crete, sent a signal through the British Embassy at Cairo to the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Mr Fraser, who was there: “Can you get more ships to evacuate us tomorrow night. Urgent.” He received the following signal from Cairo in reply:

Confirmed destroyers are coming tonight Friday. Everything possible is being done to rescue you and risks more than justifiable are being taken. Fraser and Blamey are being fully consulted and are behind all decisions. Vasey is to embark tonight if possible. Both Sunderlands arrive tonight 30-31 May weather permitting. Sunder-lands being sent tonight dusk but may be stopped by weather. Do not therefore lose opportunity of coming in warship tonight.

It was learnt from other signals from Cairo and the navy that only four destroyers would arrive that night, and only 2,000 men could be picked up. Weston selected the 4th and 5th Brigades to go. These together comprised more than 2,000 men, and it was therefore decided that one battalion must stay. Hargest chose the 21st – the strongest – and it was placed under Vasey’s command. Later Captain Morse, the naval officer in charge, announced that only 1,000 could be embarked, and at length it was decided to send off 230 men from each battalion of the 4th Brigade and the Maori

battalion; the 5th Brigade would remain, and at length the 21st Battalion was placed under its command.

The thousands of non-combatant troops awaiting embarkation were now grouped in three main areas: some still on the hillside between what Weston described as the “top storey”, where the rearguard was in position, and the “bottom storey”; others collected in the Komitadhes ravine; some grouped round Sfakia itself. In the ravine Major Bull14 of the New Zealand artillery controlled some 3,000 men including New Zealanders of several units and many stragglers. By arrangement with Burston he organised the stragglers into fifties, and perhaps a dozen such groups were embarked this night.

Four destroyers had duly sailed from Alexandria at 9.15 a.m. on the 30th to continue the embarkation, but at 12.45 one of them, Kandahar, developed a mechanical defect and was ordered to return; at 3.30 three aircraft attacked and damaged Kelvin, which also was recalled. It was evidently as a result of these losses that Weston was informed that only 1,000, not 2,000 would be embarked; but by 3 a.m. on the 31st the remaining destroyers – the Australian-manned Napier and Nizam – had embarked some 1,510 troops, including the reduced 18th, 19th, 20th and 28th Battalions. At 11 p.m. Freyberg, Captain Morse, and selected officers of Freyberg’s and Weston’s headquarters, the British and Greek air forces, the navy and the marines had left for Egypt in two Sunderland flying-boats.

At least a nucleus of one of the two New Zealand brigades on Crete had now been embarked; three battalions remained. Of the five Australian infantry battalions on Crete, however, two had been captured and two more remained on the “top storey” above Sfakia. It was estimated that the total force round Sfakia now included some 1,200 New Zealand, 1,250 Australian and 1,550 British infantry (including some 900 improvised from artillery and marine detachments), and some 5,000 depot troops and scattered detachments.15 All the rations had now been issued, the men were hungry and thirsty, and for that reason atone it would be impossible for the force to offer a prolonged resistance. No adequate plan had been made to provide reserves of food and ammunition. In addition it required much labour to supply the rearguard on the top storey with water. Twelve men working for eight hours were able to carry to the 2/7th and the Marines only 250 gallons.

Weston had informed Hargest at 7.30 a.m. that probably 2,000 would be embarked that night (31st May–1st June) and they would be allocated thus: 5th Brigade, 950; 2/8th Battalion, 200; British troops, 850. Commanders should, however, be prepared to increase those numbers at short notice. Weston informed Middle East Command that its plan would necessitate leaving 5,400 troops behind. Later he learnt from Wavell that Admiral King had been authorised to increase the number embarking to

3,500.16 Weston thereupon increased the allocation of New Zealanders to 1,400, and, climbing the hill, informed Vasey that an additional 500 Australians should be embarked that night. His intention was to allot the places proportionately among British, Australian and New Zealand troops. This made it possible for Vasey to arrange for the embarkation not only of the 2/8th but the 2/7th and his own headquarters. He ordered that his headquarters and the Marines should move to the beach at 9 p.m., the 2/7th at 9.15.

Weston informed Middle East Command that it would still be necessary to leave more than 5,000 troops behind, and that, if they were not supplied with rations, they would have to surrender. He asked for instructions; but before his request could be answered the wireless batteries were exhausted and communication with Cairo ceased.

In Cairo General Blamey, perturbed at the small number of Australians who had been embarked, asked that a ship be sent to Plakias, on the south coast between Sfakia and Timbakion, where he believed that a number of Australians were waiting – he knew that two of the Australian battalions could not be at Sfakia. Cunningham said that it was then too late to alter the destination of the ships.

After the slaughter of their advance-guards on the 30th the Germans made no attack on the 19th Brigade on the 31st, apparently contenting themselves with firing on the positions held by the 2/7th and the Marines. There were no air attacks until evening when three Messerschmitts bombed the troops forming up to embark. Vasey was confident that his men on the heights could hold their rearguard position until the night of the 1st–2nd June if necessary, provided the vulnerable beach area with its thousands of leaderless men was also held. Yet it could be seen that Sfakia was being systematically encircled. The enemy had an observation post on a hill on the right rear of the 2/7th, out of range of Laybourne-Smith’s Italian guns. In the course of the day it was learnt that enemy patrols were between Frangokastelli and Sfalda and were moving on Loutro from the west. Layforce, a new unit flung late into the fight, was relieved at Komitadhes by the remaining part of the Maori battalion and moved to the area immediately about Sfakia.

The 5th Brigade now formed an inner perimeter round Sfakia: the 28th at Komitadhes, the 21st in the ravine in the centre, the remaining men of the 4th Brigade (now called the “4th Battalion”) west of the ravine, the 23rd farther west, and the 22nd on tracks west and north of Sfakia. Within this double line of weary, hungry, but still dogged and disciplined soldiers was assembled a mere crowd of ill-organised men; the vigorous Hargest, who had placed a cordon round the beach to control this throng, wrote:

There were hundreds of loose members, members of non-fighting units and all sorts of people about – no formation, no order, no cohesion. It was a ghastly mess. Into all this I was hurtled with no knowledge of it and with my hands already full. What had happened was that men had straggled; small units like searchlight detachments had walked off when their job was done; isolated troops of gunners, engineers, field ambulance, with no one to look after them. But the stragglers were the worst, lawless and fear stricken. At night they rushed for water and ravaged the food dumps and crept back into caves at dawn – a hopeless lot – Greeks, Jews, Palestinians, Cypriots helped to swell the total. My mind was fixed. I had 1,100 troops – 950 of the brigade and 150 of the 20th Battalion. We had borne the burden and were going aboard as a brigade and none would stop us. All day I answered pleas to be allowed to come. ...

Many of the troops – particularly those to whom Hargest here refers – were now starving and plagued by thirst. There was no water supply on the south coast except from one insanitary well, and no adequate plans had been made to provide stores of food or ammunition for the thousands who were assembling round Sfakia. Some stragglers were so hungry that they ate snails. The long march had brought most men close to the limit of endurance.

At 7 p.m. Vasey’s brigade major, Bell, informed Walker of the 2/7th that he was to withdraw to the beach that night. Walker fixed the time to begin withdrawal at 9 p.m. and his adjutant, Lieutenant Goodwin,17 wrote the following order:

1. Cancel all previous orders.

2. MONT [code name for 2/7 Bn] will move tonight.

3. First elements 2100 hrs.

4. Last 2115 hrs.

5. Bn H.Q. closes 2100 hrs.

6. Assembly area at foot of track. Guides will direct from main road. Coys will form up in this area.

7. Silence. Movement must be swift and catlike. It must be impressed on all ranks that accurate timing, pace and SILENCE will make successful move.

Howard K. Goodwin, Adj.

At 9.30 Weston handed to Colonel Colvin of Layforce a written order pointing out that the wireless set would soon give out, no rations were left, and no more embarkations would take place after that night.

I therefore (he concluded) direct you to collect such senior officers as are available in the early hours of tomorrow and transmit these orders to the senior of them. These orders direct this officer to make contact with the enemy and to capitulate.

Meanwhile at 6 a.m. on the 31st Admiral King with Phoebe, Abdiel, Hotspur and Jackal sailed from Alexandria for the final embarkation. Small though it was, this squadron comprised a substantial part of the fleet now left to Cunningham, who had warned the Admiralty that, assuming no more ships were damaged, he would be left with only two battleships, three cruisers, the minelayer Abdiel, and nine destroyers fit for service in the whole Mediterranean Fleet.

Having been informed by Weston that there would be no further embarkation after the 31st Burston instructed Forbes to have his guides at the embarkation point by 9 p.m. He himself then went across country to the beach to try to preserve control there. He wrote later that

by nightfall organisation had completely broken down at Sfakia and troops were reaching the beach by the alternative route [to the west of Komitadhes] or just across country in small batches. With the withdrawal of the guides and their organisation from Komitadhes and the track the situation became hopeless, but Captain Forbes managed to get his men to the beach about 0100 hrs ... as a disciplined unit. All were embarked on the last boat to leave the island.18

The ships had arrived off Sfakia at 11.20 p.m. The three landing craft which had been left on the beach were ready loaded and promptly went alongside. The 5th Brigade was in a dense column whose head was on the beach. Through a cordon it had formed passed the 21st, 22nd and 23rd Battalions, the remainder of the 20th and 28th, and the 2/8th (203 men) – but only 100 of the Marines, 27 of Layforce, and 16 of the 2/7th. When the ships sailed at 3 a.m. about 4,050 had embarked.

Thus the 2/7th Battalion and most of the Marines and Layforce had been left behind. The reasons why the 2/7th was not embarked are set out in Vasey’s report:

The route lay along a wadi and a very narrow track which ended up winding through the village of Sfakia. When some little distance from the beach it was found

that this road was blocked with men sitting down and many officers challenged anyone approaching wanting to know what they were. Other officers represented themselves as MCO’s (Movement Control Officers) and eventually one of these said only single file was allowed through from that point and that 19th Aust Inf Bde would have to wait. With the exception of myself and two staff officers, who went . forward to see what the situation was in front, 19th Aust Inf Bde remained in this position for some time. On arrival at the beach I found the embarkation proceeding smoothly and troops filling the boats brought in from the ships reasonably quickly. Not long afterwards, however, it was noticed that troops were not available on the beach when boats came in and there was considerable delay in getting the boats filled and away to the ships. I sent my two staff officers back to investigate the reason for this and to see if brigade HQ and the 7th Battalion had got through and down to the beach. They were absent some considerable time but the rate of movement of troops on to the beach had improved.

19th Aust Inf Bde [headquarters] arrived on the beach at about 0215 hrs and they reported that they had been continually hampered in their movement forward ... through lack of control in the area behind the beach.

Later Vasey was informed that the commanding officer of the 2/7th had arrived on the beach, and, concluding that all was well, he embarked with his staff. He did not learn the truth until he arrived at Alexandria.

When the 2/7th had begun to withdraw at 9.30 p.m. its leaders knew from their experience in Greece that it was a race against time. Later, in a German prison camp, Major Marshall, the second-in-command, who was with the last company, wrote:

I could have no mercy on them and I had to haze them and threaten them and push them into a faster speed. We crossed the road and stumbled on after Atock19 (of the Intelligence section) who was guiding us down the centre of this rocky valley. Falls were numerous but I would permit no delay as I knew that time was against us. One of the “A” Company men fell and refused to get up, wanting to be left where he fell and not caring if he were captured or not. ... I pulled him up and supported him for the next five miles; every time we stopped he sagged and pleaded to be left.

At length this last company caught the remainder of the battalion, but just short of Komitadhes village there was a halt. Marshall went forward and found Lieutenant Lunn with another company; Lunn said that the remainder of the battalion had moved off on a different route to the one he had reconnoitred and he dared not abandon the company that he was guiding. Sergeant Thomas20 of the Intelligence section thereupon guided the two companies over “nightmare country” in pitch darkness until the weary column reached the beach road, and heard the voices of others of their unit; some were so tired that they fell to the ground and slept.

When its turn came the column moved on slowly down the cliffs above the beach itself. The path was jammed with unarmed men. The head of the 2/7th reached the beach and Colonel Walker immediately sent a few of his men on to a landing craft waiting there. The craft departed and the battalion, drawn up in order on the beach and the road, waited for

it to return. An officer on the last barge watched the battalion standing there “quiet and orderly in its ranks”.

Then came the greatest disappointment of all (wrote Marshall, who was on the beach). The sound of anchor chains through the hawse ... I found Theo [Walker] and we sat on the edge of the stone sea wall. He told me that things were all up and that the Navy had gone .... All our effort and skill wasted.

In the dark early hours Walker and Marshall discussed the possibility of fighting a way along the coast in the hope of being picked up by naval ships. Later some of Walker’s men came to him and said that officers and men on the beach were flying white flags. “Shall we shoot them?” they asked. Walker went down and found Colonel Colvin and another, who asked him the date of his promotion, and, learning that he (Walker) was the senior, handed him Weston’s order, quoted above. Walker decided that resistance was hopeless. He told his men to destroy their equipment and escape if they could. Hundreds of unarmed men were waving white flags, and soon German aircraft began shooting at them. With Goodwin, his adjutant, Walker climbed to Komitadhes, where he met an Austrian officer and surrendered to him. “What are you doing here, Australia?” asked the Austrian in English. “One might ask what are you doing here, Austria?” replied Walker. “We are all Germans,” said the Austrian.21

German reports record that by the afternoon of 29th May the 100th Mountain Regiment was two miles south of Alikambos. Next day, after having thrust back “strong enemy detachments” (the small party of tanks of the 3rd Hussars and carriers of the 2/8th), it met the British rearguard near Imvros. Its position near the end of the made road was so strongly held that the German commander was compelled to make flanking attacks, sending one company east and two west of the road. These companies failed to find the British flank, and, later on the 30th, one company was dispatched on a wider outflanking move through Asfendhon towards the coast some four miles east of Sfakia and another along the heights well to the west of the road. The Germans now occupied Hill 892 east of the road, and thence their observers saw the British troops crowded round Sfakia and Komitadhes. They made no attack that day but waited for the flanking moves to encircle the force (these were observed by the British rearguard). On the morning of the 1st June four dive bombers and four fighters arrived and attacked the Sfakia area, and a light gun that had been hauled on to Hill 892 began shelling the enemy. White flags were raised. Thereupon the I and 11 Battalions of the regiment advanced to Komitadhes and Sfakia; they at length took prisoner (according to their reports) some 9,000 British and 900 Greek troops. The German commander seems to have had no inkling that, the night before, a flotilla had arrived off shore and embarked 4,000 men.

On the 1st June thousands of British troops were still at large in Crete, and in the succeeding months perhaps 600 of them made their way back to Egypt in landing barges, fishing boats and submarines.

The three motor landing craft22 that had been used to ferry men to the warships remained at Sfakia and it was one of these that carried the largest

party to escape after organised embarkation ceased. On the 1st it set off containing five officers (including Major Garrett of the Royal Marines; Lieutenants K. R. Walker,23 2/7th Battalion, and Macartney,24 2/2nd Field Regiment) and 135 others, including 56 Marines. That day it reached the island of Gaydhapoula, eighteen miles from the coast, where the engines were overhauled and rations collected; that night it started for Africa. The petrol was exhausted next day, and the craft drifted on the 2nd, 3rd (a despondent Palestinian soldier shot himself that day), and 4th. On the 5th a sail was made by lacing seven blankets with bootlaces and the barge got under way, though when she veered out of the wind the fit men had to go over the side and push her into it again. That day the ration was reduced to half a biscuit covered with bully beef and half a cup of water per man. On the 6th there was no wind. On the 7th a man died of exposure. By the 8th all the men were very weak; Garrett held a church service, “which did a lot to help us along”. ‘That evening land was seen; and “with expert handling of sail by Corporal Nugent25 and Private Legge,26 and wonderful knowledge of sailing by Major Garrett eventually beached at 0230 hours on 9th June. ... Position approximately nineteen miles west of Sidi Barrani”.

Lieutenant Day27 of the Welch Regiment took charge of another landing craft at Sfakia on 1st June and put to sea with a company of forty-four including men of his regiment, marines, commandos, five Australians and a Greek. They stopped at a small island to collect food and water, and on the evening of the 1st when they set a course for Derna they had eighty gallons of petrol, one tin of biscuits, nine of beef, four of meat and vegetables, two of bacon, one of fruit and “the unexpended portion” of a sheep given by the Greeks on the island.28 The petrol was exhausted at midday on the 2nd. A sail was made for the barge with two blankets, and Day with seven men of his regiment and Driver Anstis29 and Private Green30 boarded a long boat they had been towing and set off, using an improvised sail and four oars, to obtain help. No more was seen of them by the men in the barge, but they eventually reached Egypt. Private Hansen31 took control of the landing craft. “He said he was able to navigate as he had knocked about a lot,” wrote Horne.32 “From 2nd to 5th June we had biscuits only to eat but these gave out on the 5th. From then on

we had nothing to eat but were able to keep to our ration of water (four spoonsful night and morning). ... About 8th June some of the commandos started to drink sea water. Hansen had a Tommy gun and told them that if they did not stop he would take severe action. This threat effectively stopped them.” They reached land near Sidi Barrani on the 10th having had no food for five days.

An enterprising private of the 2/11th Battalion, Harry Richards,33 “rescued” a third invasion barge, 96 SD 15, and concealed it in a cave. It had eighty gallons of petrol and Richards decided that he could take off fifty men and sail them to the African coast, calling at Gavdhos Island on the way to replenish food, water and fuel. The barge started at 9.20 p.m. on 1st June. As it moved noisily into open water Germans opened fire with two machine-guns but Richards and his engineer, Taylor,34 soon had it moving at top speed. Just before dawn next morning it ran aground on Gavdhos. There the passengers filled the water containers. Finding that only fifty-five gallons of petrol remained and food was short, Richards appealed for volunteers to remain on the island and so give the others a reasonable chance of reaching Egypt. Ten men stood aside, and at dusk the barge set sail, now with two officers and fifty men including one Greek. On the afternoon of the 3rd MV Leaving, as Richards named his craft, met another barge sailing south; at 5.30 he wrote in his log: “Here is where we want a lot of luck as now our petrol is all used up and still have over 100 miles to go.” On the 4th and 5th the barge sometimes drifted, sometimes moved at “a fair speed” with a sail made by Richards from four blankets. On the 5th the food was practically exhausted and for the next three days consisted of only some tins of margarine and cocoa which Richards mixed and issued in small quantities, with hot cocoa made with water. On the morning of the 8th the men were very weak. Richards wrote in his log:

Sunday 8 Jun 0900 hrs. Flat calm – more cocoa and margarine – all hands very weak and conditions becoming worse hourly. At this stage I have had to address some of the members in words I cannot write – just the same moaning few.

1000 hours. I have called all members together and we held a service which was conducted by [an English sergeant]. I might mention here that every man on the boat put his heart and soul into this service.

1030 hrs ... I have sighted land but am afraid for the time being to announce this as it might be trick of imagination, but no – as I creep nearer I distinguish land clearly.

For fourteen more hours the barge drifted towards land and grounded near Sidi Barrani at 2.30 a.m. next day. Richards’ “care for us was beyond description”, wrote one escaper. “He exercised his command in a most masterly manner and inspired every one of us to keep his spirits up.”

To turn to the experiences of men left elsewhere in Crete: as mentioned above, Major Sandover and Captain Honner, on the 30th, had set out to lead two large parties of the 2/11th Battalion from the Retimo area

to the south coast. By 4 p.m. next day the leading parties were 10 miles north of Ayia Galini. Next day they reached the village and found there about 600 troops, including 300 of the Argyll and Sutherland from Heraklion, some of the Black Watch, and parties of naval and air force men. During the day about 200 Australians, chiefly of the 2/11th, 2/1st Machine Gun and 2/ 3rd Field Regiment came in. The senior officer there was Major McNab,35 and the group included Major Ford who had been liaison officer with the Greeks at Retimo, and Major Hooper, Campbell’s second-in-command, who had also been with the Greeks.

In the cove two landing craft were stranded. The naval officer in charge said that they could not be got into the water but Private McDonald36 and Corporal Lee37 of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion collected a party which grew to fifty officers and men and after two days of labour succeeded in launching one. Captain Fitzhardinge,38 a leader in this party, then took three men in a small sailing boat to Timbakion to collect provisions. While they were there German motor-cyclists arrived and opened fire on them. They dashed to the boat and two men lay in the bottom while Captain Fitzhardinge and Private Mortimer39 swam and towed it from the beach. The boat was repeatedly hit and Lieutenant Bedells40 was wounded in three places; but they reached Ayia Galini. The landing craft was provisioned and it set out at 8.30 p.m. on 2nd June carrying eleven officers and sixty-six other ranks, with Fitzhardinge in command and Sergeant McWilliam of the South African Air Force as engineer. At 3 a.m. an Italian submarine stopped the craft and took off nine (all except two) of the officers (including three Australians – Fitzhardinge, Lieutenant Morish,41 and Ryan, the gallant medical officer of the 2/11th). These officers were taken to Italy. On 5th June the landing craft, with Sergeant McWilliam in command, beached at Mersa Matruh, close to the positions of the 2/7th Field Regiment, in which a brother of Fitzhardinge and a brother of Morish were serving.

Meanwhile British aircraft had appeared and given signals at Ayia Galini, and the remaining men were filled with hope that a vessel would be sent to take them off. None came, however, and on 6th June a party of Germans arrived and demanded surrender. “Everyone was very hungry, cold and beginning to despair, some were bootless and nearly all chucked it in,” wrote Sandover later. He himself, however, and five of his officers, were bathing in the river some distance away and they made for the hills again.

Meanwhile one of the West Australians had made a single-handed

escape. He was Private Carroll42 who took a sixteen-foot Greek fishing boat which lacked even rowlocks or oars. He used a six-foot piece of driftwood as a mast, a fishing spear as a boom and a piece of bamboo as a peak, and made a sail from a piece of light and ancient canvas found in a flour mill. He set sail on the night of the 11th June. Next morning he was fired on by a German reconnaissance aircraft. He had intended to sail along the coast and find some companions, but after coming under fire at each attempt to return to the coast he set off alone for Egypt. He had six tins of chocolate and two gallons of water; the African coast was 350 miles away and he estimated that in a medium breeze his speed would be three knots. Carroll made slow progress for six days. He wrote afterwards:

At dawn on the seventh morning a strong north-wester blew up and by 1000 hours had developed into a gale. I was obliged to alter my southerly course and run before the wind. Up till then I had used [for a guide] a pen knife mounted on a piece of board. When the blade cast a fine shadow I knew I was heading due south. Sailing by night I used the north star as a guide. For more than twenty-four hours I ran before the wind, surfing the waves which must have been twenty or thirty feet high. My eyes were giving me a lot of trouble, the left being badly affected gave me a blind side making it difficult to judge the waves. A little after sunrise I could see a haze in the sky away to the south. Taking a chance I pushed the boat across the waves, it was quite a battle holding her against them, they were striking me broadside on. The mast being a misfit began to kick from side to side. Twice I took a risk and left the tiller to brace it with floor boards but was nearly swamped. Hoping the planks would hold out long enough, I kept on and sighted land about 0800 hours. I gave her every bit of canvas she had, not caring a hang what happened now. About 1000 hours she began to leak badly, forward on the port side. With still a good distance to go the water commenced to beat me; trying to bail and steer at the same time was impossible, I couldn’t keep my feet. Land appeared to be only a few miles off but it must have been nearer ten.

When the boat filled and overturned and the mast smashed a hole in the bottom, my dreams of sailing into Alexandria went with it. Tying my tunic to the rudder clamps I fixed the water tin, almost empty now, across my shoulders and struck out for the shore. It took me seven hours to reach land, swimming, floating and surfing. From the crest of the waves I could see the breakers pounding on the rocks and dashing spray feet into the air. This was about the closest call I’d had up to date and I had a terrific struggle to try and keep from being carried on to the rocks and retain my hold on the tin. If I couldn’t find a place to go in, I thought it might serve to take the impact, giving me a chance to scramble clear before the next wave hit me. Fortunately I was able to work my way along to a small patch of sand and came ashore, the breakers spinning me around in all directions. I had to crawl on my hands and knees, feeling too giddy to walk.

I drank most of the water I had left, wrung the water out of my trousers, the only article of clothing I had, and started inland. I knew the road ran somewhere near the coast. The ground was too rough on my bare feet, so I returned to the beach and headed east along the sand-hills. After walking for about an hour I came across an air force listening post. The very dark chaps wearing blue peaked caps made me think I was in enemy territory but they turned out to be Maltese. A message was sent to control and next morning I was taken to Mersa Matruh.

When he arrived in Egypt Carroll gave information that small parties of Australian and British troops were still at large round Ayia Galini. As

a result Lieut-Commander F. G. Poole, who had lived at Heraklion before the war, was landed in the area from a submarine late in July. He soon met Captain Jackson of the 2/11th who had led a party of five other officers and nineteen men of his unit to the south coast, and next evening the submarine--HMS Thresher – took off this party and as many other Australian, New Zealand, British and Cypriot troops as could be gathered in the time.43

Poole remained on Crete when Thresher sailed, but it was arranged that a submarine would return on 18th August, by which time he was to collect another submarine-load of soldiers. Poole sent messages by trusted Greeks to several parties of troops learnt to be hiding in central Crete. To Sandover, whom his information caused him to mistake for an English archaeologist from Heraklion (who had in fact been captured at Ayia Galini), he sent the following cryptic (but effective) message: “Do you remember the young lady who swam naked to the Elafonisos Islands. The man who entertained you then is waiting to greet you now. Follow this guide, he can be trusted.” Sandover reached Poole after an 11-hour journey and was instructed to bring any parties he could find to Prevali. There on the nights of the 18th, 19th and 20th August, more than 100 troops were taken off in the submarine Torbay. Altogether 13 officers and 39 other ranks of the 2/11th Battalion who had fought at Retimo escaped.44

Private Buchecker,45 an Australian, and two New Zealanders, Privates Carter46 and McQuarrie,47 stole a boat on the night of the 15th–16th July, and sailed south-east and south until they reached Sidi Barrani on the night of the 19th. On 17th September Captain Adonis of the Greek Navy brought out a party of eleven, including five Greeks, two Scots, one Australian,48 two Cypriots, and an “Austrian refugee” in a fishing boat which was intercepted by the destroyer Kimberley forty miles from Bardia on 20th September.

On 3rd July Captain Embrey of the 2/1st with Private Hosking,49 2/11th, and Gunner Cole,50 2/3rd Field Regiment, escaped from Maleme prisoners’ camp and walked south into the hills. There they lived in an area where “every village had from two to five ‘English’, and planned escape. Embrey estimated that at this time about 600 Australians and 400 New Zealanders were living in villages in western Crete. Under 5th July

Hosking’s diary of this escape says: “Met Greek. Said ‘Kalimera’ (Good Day) in best Greek. Reply: ‘Hullo, George’ despite Greek clothing.”

Embrey made many plans to escape but there were few boats and they well guarded. Late in July he met Lieut-Commander Vernacos, a Greek in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. Vernacos who had been busy organising refuge for British troops in the villages now persuaded Embrey and two officers of the Notts Yeomanry to join him in an attempt to escape and organise British help for a revolution in Crete. After the failure of many plans these four sailed to Greece by night in a Greek caique and thence, after many privations, they reached Turkey on 4th September.

In the area of Neapolis at the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese had gathered other parties of Australians, some of them from Crete, who wandered from village to village and sought a means of sailing to Africa or Turkey. One party, including Private Hosking and Gunner Cole above mentioned, and with Sergeant Redpath51 as leader, decided to seize one of the fishing boats, which they had noticed sheltering in the bay of Agia Elias on the south coast of Greece. Accordingly one night three of them swam out 400 yards, detached the caique’s dinghy and towed it ashore. Seven men then rowed out in the dinghy, woke the crew of the caique and “explained to them roughly the idea”. The captain of this vessel deceived the Australians into allowing him to return to his home for stores and equipment and eluded them. The same men then repeated their tactics and captured a second caique. In this vessel they sailed from Greece on 10th October and landed west of Mersa Matruh on the 17th, having been bombed at by both British and German aircraft on the way.52 By 1st September 317 Australians had escaped from Crete, including 23 officers.

Even after September resolute escapers were still trickling back to their units in the Middle East. One of these who wrote a particularly full account of his experiences was Lance-Corporal Welsh53 of the 2/6th Battalion, who served in Crete in the 17th Brigade Composite Battalion. Welsh escaped from a prison camp at Skines in the hills south-west of Canea early in June. With another Australian he took a rowing boat and set out for Cyprus, but, 500 yards from the shore, they were attacked by two aircraft, which chased them to the shore and there destroyed the boat. Welsh returned to Skines and re-entered the prison camp without his absence having been noticed. Early in July some 3,000 prisoners including Welsh were shipped to Salonika and placed in a verminous and disease-ridden prison camp there.

About 13 July 1941 I made another attempt to escape, this time in company with many others (he wrote later). There were three main blocks of latrines and wash

houses in the camp, and from each of these led a drain which discharged into a pit which was about 6-ft deep, 6-ft in diameter, and was covered by a 2-ft manhole with a concrete lid. From this pit a main sewer ran for about 200 yards, under the wire, and discharged into a small creek outside the wire. This sewer was about 2-ft 6-in. in diameter to start with, but got smaller as it ran outwards. A party had got out of the sewer earlier that night. Our party consisted of 30 and we decided to go at 11 p.m. divided into three smaller parties of ten each, allowing a few minutes intervals between parties. This ... would give us some air in the sewer which was very foul with gas, and secondly searchlights played over the camp at intervals and there was more chance for smaller parties. My party of ten went first, and I led the party, followed by Hadwell,54 and two other Australians. I crawled along on my hands and knees, but as the drain grew smaller I had to wriggle. Some of the men who had gone before me had discarded garments in the sewer, which made passage more difficult. The bottom of the sewer was running with liquid and the sides covered in filth. The whole of our 30 got into the sewer all right, but when I reckoned that I was only about 30 yards from the exit and under the wire the pipe bent a bit and I came upon the body of a Cypriot. He must have been overcome by the fumes in the drain and had collapsed and died; his head was half under. I tried to crawl past him, but this was impossible, then I tried to dislodge him or push him in front of me, but not being able to kneel up I could not do so. I told Hadwell that we would have to get back but he urged me to have another try. After violent efforts to dislodge him I failed, and then tried to dislodge the bricks of the sewer, but this only broke my nails. I was sweating hard and breathing heavily and thought for a moment that I was going to go out with the foul gas. It was, of course, pitch dark in the sewer. The people behind could not understand what was happening and were pushing to get on, although Hadwell had passed word back what was happening. Finally we told them that the Germans were in front of us, which was not true, but had the desired effect, and we all started back up the drain cray-fishing all the way because we were unable to turn around. Our pockets got filled with filth. Fifteen of the men got back all right, climbed out through the man-hole and dispersed to their quarters. Each man had to wait and dodge the searchlight. Unfortunately, as the fifteenth got out he let the heavy cement lid drop with a bang on the man-hole, the guard heard the bang and flashed his torch upon him, opened fire, called out the guard and rushed in and prevented us from getting out. Guards were sent to the other end of the drain to capture anyone escaping, and also were ordered to fire up it, and they did so. Luckily for us in the drain there was a bit of a bend, where the Cypriot was stuck, and most of the bullets lodged in his body and a few ricochetted on, but no one was hit. Next day when the Cypriot’s body was removed I was told he had six bullets in him. The guards shouted to us to come out, or they would throw bombs down the man-hole. As each man emerged from the man-hole he was subjected to a brutal attack by the guards who hit, kicked or struck with the butts of their rifles at any portion of the body that opportunity offered to them. Getting out, my friend Snowy Hadwell slipped and fell back into the pit. The guards thought he was trying to get away and fired into the pit and a bullet wounded him in the right thigh. I helped Hadwell to get out of the pit and was then kicked on the leg with a jack-boot, and was unfortunate enough to be struck on the head with a rifle butt and passed out.

When I regained consciousness, which I think was about an hour later, I was lying on the floor in the guard room. A Cypriot who had been shot trying to run away, was lying on a stretcher screaming for water, the other twelve were lined up around the wall with their hands in the air, and guards were standing close to them pointing bayonets at their stomachs. A German officer, who was the Camp interpreter, and who wore a white uniform and a funny little dress sword, was abusing the guards and asking questions of the prisoners. He wanted to know how many had got out,

where we were going to if we had succeeded in getting out, and above all, who was the ringleader of the attempt. He did not get any information from anyone.

After five days in hospital Welsh was interrogated by two Gestapo men who attempted in vain to discover who were the ringleaders among those who had tried to escape and whether the Australian medical officers were helping men to escape.

Welsh was still determined to get away. In August, having obtained a complete outfit of Greek clothing, he slipped out of the camp with a large working party of prisoners who were employed grooming horses. He hid in a forage store, removed his uniform, revealing his Greek workman’s clothes, and walked out past the guard. In Salonika he went to the poorer part of the city.

I thought my best chance of making a contact and not being given away, was to find some woman with a large family .... I saw a fat woman with a lot of children playing in the front garden. ... I walked straight up to her and told her I was an Australian soldier. She whipped me into the house and sent for her husband, but I could not make myself understood very well. However they immediately gave me food and were most kind.

The Greeks led Welsh to a house where six other soldiers were hiding. Friendly Greeks guided Welsh and another Australian, Walter Sicklen,55 of the 2/1st Battalion, south-east to Athos where they at length met a priest and obtained a boat to take seven escapers who had assembled there to Turkey. After several attempts to make the voyage had been defeated by stormy weather, they reached the Turkish island of Imbros, where the priest landed them and then set off for Athos to bring more prisoners over. In Turkey they joined thirteen other escaped prisoners. At Adana “the German Consul complained to the Turkish Government about the passage of British prisoners of war, but was reminded gently about German and Vichy escaped prisoners and soldiers who were in Turkey awaiting pass-ports to Europe”. On 10th October this group of prisoners crossed the Turkish border into Syria (which had meanwhile been occupied by British troops).

The total strengths of the British, New Zealand and Australian contingents on Crete on 20th May were: British 17,000, New Zealand 7,700, Australian 6,500. About 16,500 were embarked. The losses suffered by these contingents were:56

| Killed | Wounded | Prisoners | |

| New Zealand | 671 | 1,455 | 1,692 |

| British Army | 612 | 224 | 5,315 |

| Australian | 274 | 507 | 3,102 |

| Royal Marines | 114 | 30 | 1,035 |

| Royal Air Force | 71 | 9 | 226 |

Thus the effort to hold Crete cost the British force about 15,900 men, of whom about 4,000 were killed or wounded; the Germans claimed also 5,255 Greek prisoners, and they released 14,000 Italians. The German Fourth Air Fleet reported the loss of 3,986 killed or missing, of whom 312 were air crew; and 2,594 wounded; 220 German aircraft were destroyed.57 The German force employed totalled 23,000. The German troops who were killed were almost all highly-trained fighting men, more than 3,000 of them from the 7th Air Division – a crippling loss to this skilled formation. The British soldiers who were captured belonged mostly to base units; in fighting units the heaviest loss was the Australian – three infantry battalions as well as parts of other fighting units. For gallantry on Crete the German mountain troops were awarded 5,019 Iron Crosses of various grades, and 971 War Service Crosses.

Could Crete have been held? It is now evident that from November onwards useful time was lost because of the failure of the higher staffs to define a policy and appoint a senior commander who would remain on the island and carry that policy out. In 1941 an Inter-Services Committee was appointed to report on the campaign. Although the evidence before it was not comprehensive, some of its judgments remain valid. “Six months of comparative peace,” it decided, “were marked by inertia for which ambiguity as to the role of the garrison was in large measure responsible. ... There was a marked tendency at one time to regard Crete as a base for offensive operations against the Dodecanese without any apparent regard to the advisability of being able to operate from a secure base.”

It was axiomatic that Crete would be attacked only if the enemy commanded the air, in which case sea communications would be precarious. It was desirable therefore that large supplies should be stored on the island before strong air attack developed. A garrison preparing to meet airborne attack could have been given one telling advantage over its adversary – possession of heavy weapons which could be landed in

quantity from ships, whereas the enemy would have to depend on such weapons and ammunition as aircraft could carry. If the tank, artillery and infantry units retained on the island had been fully equipped with efficient heavy weapons – tanks, guns and mortars – the initial German attack would probably have been beaten in every sector. To have provided this equipment would have necessitated boldly denuding units in reserve in Egypt and Palestine; a middle way was followed of sending to Crete a few tanks, but not enough to be effective, and some captured guns most of which were incomplete and all inferior.58 Crete was lost.

The problem of supply which was certain to become acute sooner or later could have been greatly lessened by removing from the island all except strong and fully-equipped or re-equipped units. The eventual removal of about 16,000 troops in four nights demonstrated that the embarkation of all ill-armed or inessential detachments could have been carried out much earlier by employing similar methods.

General Freyberg’s position was unenviable. Greater foresight on the part of Wavell and his staff would have placed on Crete a commander and staff who, at least since the decision to send a force to Greece, might have devoted themselves to planning the defence of the island, and incidentally to the problems of withdrawal from Greece to Crete. But Freyberg had not been on Crete until he landed on the 29th April, weary after commanding the rearguard in the Peloponnese; he inherited no comprehensive plan; he had to improvise a staff (and by so doing depleted the staff of his old division) ; at the outset a large number of his men lacked even light weapons and personal gear. When the attack opened his troops, though in good heart, were still often poorly equipped, particularly his artillery. He had no motor road to a port on the south coast, and Suda Bay was a dangerous harbour, to be entered only at night by fast ships, of which few could be spared.

Once an airfield was firmly in German possession there was no longer any hope of defending Crete. A swifter and stronger counter-attack by the reserve on the night of the 20th or 21st might have recaptured the Maleme field. This would have prolonged the resistance of the garrison; but whether it would have caused General Lohr to cut his losses and accept defeat can only be guessed.59 If he was resolved to order his troops to hold their ground and his air force to isolate the British garrison, he was sure to win eventually – if only because the garrison’s supplies would be exhausted and the navy would be unable to afford the losses involved in preventing invasion by sea. In the fight for Crete the Mediterranean Fleet lost the

cruisers Gloucester, Fiji and Calcutta, and the destroyers Juno, Greyhound, Kashmir, Kelly, Hereward, and Imperial. Two battleships, an aircraft carrier, two cruisers and two destroyers were damaged so severely that they could not be repaired at Alexandria; three cruisers and six destroyers were less severely damaged. About 2,000 naval men were killed. In addition, during the operations in and round Greece and Crete from 6th March to 2nd June 315,000 tons of British and Allied merchant shipping were lost. Lohr’s aircraft losses could easily be replaced, but each British naval ship sunk or damaged gravely reduced the narrow margin by which Admiral Cunningham held the eastern Mediterranean. (In addition, from 23rd to 27th May, the German battleship Bismarck was at large in the Atlantic; on the 24th she had sunk the Hood and damaged another British capital ship.)

However, the disastrous losses suffered by the German airborne division in Crete dissuaded Hitler from ordering a similar attack on Cyprus, then slenderly held by less than a brigade.

The German decision that they should not attempt airborne attack on Cyprus was promptly taken. A proposal to capture it with a seaborne force sailing by night from the Dodecanese was substituted, but was never carried out. It can justly be said that the resolute resistance offered by the garrison of Crete saved Cyprus from a similar attack, which must have succeeded. The garrison of Cyprus then comprised the 7th Australian Cavalry Regiment (Lieut-Colonel Logan60), 1/Sherwood Foresters, “C” Special Service Battalion (commandos), a battalion of Cypriots and a troop of field artillery.

Cyprus remained a source of acute anxiety to the British leaders for the following three weeks, however. On 6th June General Blamey reported to the Australian Government that the estimated scale of attack on Cyprus was by 450 German transport aircraft, which could land 7,000 to 8,000 troops in 48 hours; and that the force required to ensure the safety of the island should include four infantry brigades, two regiments of light tanks and one squadron of heavy tanks, and supporting units. “Position is one of acute anxiety to Middle East Commanders,” he added, “but no prospect increasing garrison for next two to three months.”

When he received this cable, the Australian Prime Minister, Mr Menzies, sent a message to the High Commissioner in London, Mr Bruce, on the 8th June that “another forced evacuation, particularly if accompanied with great losses, will have serious effect on public opinion in America and elsewhere, whilst in Australia there are certain to be serious reactions which may well involve the Government”. He offered the opinion that there were two alternatives: either to garrison Cyprus with a sufficiently strong force or to abandon it.

Soon, however, the fears about Cyprus were submerged in other anxieties, and, in a fortnight after Menzies’ cable, the invasion of Russia would begin.

It was perhaps fortunate from a British point of view that the German forces persisted with the attack on Crete and took the island without great delay, accepting the heavy losses which dissuaded them from undertaking a similar attack on Cyprus. If the airborne invasion of Crete had failed and a struggle had developed between a German air force on the one hand and the Mediterranean Fleet and air force on the other, the one loyally attempting to supply and support the garrison of Crete, the other determined to isolate it, Britain would probably have been by far the heavier loser in a costly campaign of attrition. As it was, Admiral Cunningham described the twelve-day battle for Crete as “a disastrous period in our naval history”.