Chapter 18: Across the Litani

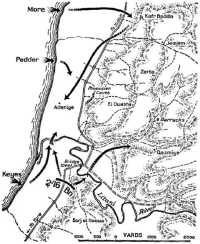

ON the evening of the 8th Brigadier Stevens, commanding in the coastal sector, faced a problem very like the one that had confronted him the day before. His engineers had repaired the road at Iskandaroun, but the Litani bridge lay ahead – another frontier to cross. He now knew that the sea had been too rough to permit the landing of the commando battalion early on the 8th, and that a second attempt to land them would be made on the 9th. He had been instructed that, if his own men crossed the Litani before 4 a.m. on the 9th, they were to fire four Very lights to warn the commandos, then out to sea, not to land; if no lights were seen, the commandos would come ashore at 4.30 a.m. and try again to save the Litani bridge.

On the afternoon of the 8th Stevens had ordered Lieut-Colonel MacDonald of the 2/16th Battalion to launch an attack at 5.30 a.m., but only if the commandos had been unsuccessful. MacDonald allotted the task of saving the bridge to Captain Johnson’s company to which a fourth platoon was attached to carry canvas boats forward in case they were needed. A second company was to follow Johnson’s across the river, and a third (Major Caro’s) was to move out to the coastal flank to give supporting fire for the commandos – if they landed.1

What had happened to the commandos? The unit (twenty officers and 400 men) had sailed from Port Said in the transport Glengyle on the 7th, with a naval escort, and arrived off shore about four miles west of the Litani before 1 a.m. on the 8th. Assault landing craft were lowered and filled with troops. In the moonlight a heavy surf could be seen, however, and the naval commander decided that the craft would capsize before they were beached. The men re-embarked in Glengyle, which returned to Port Said. At 3.15 a.m. on the 9th Glengyle was again off the Litani escorted by a cruiser and two destroyers. For the landing the commando unit was divided into three groups: one under Major Keyes2 was to lead the attack on the position north of the river; a second (Captain More3) was to cut off this area from the north; the third formed a reserve. Unhappily a sandbank obscured the mouth of the river and, at 4.50 a.m., Keyes’ group landed half a mile south instead of north of the river and south of the flanking company of the 2/16th. Nevertheless they advanced to the attack.

The river was from 30 to 40 yards wide and flowed fast between steep banks lined with poplars. The road travelled round the foot of the hills about 1,000 yards from the coast and crossed the river on an arched stone

bridge. North of the river the road travelled through flat land planted with fruit trees and corn for about 500 yards. This flat land was dominated, north of the river, by a steep hill about 500 feet in height into which the main French defences were dug.

A few seconds before the attack by the 2/16th Battalion towards the bridge was to begin, a scout, who had been sent out to reconnoitre, shouted the news that the bridge had just been blown up. Thereupon the plan, whereby one platoon would rush the bridge covered by the fire of another, had to be scrapped. The

only course was to cross in the boats. The men of the leading company took what shelter they could from heavy enemy fire which opened a: soon as the bridge was blown – chiefly among the headstones of a graveyard near the river bank. In a few minutes the boat-carrying parties arrived. Johnson decided that the river was flowing too fast – about five knots – to paddle the boat: over, and Captain Hearman,4 his second-in-command who was in charge of the boats, e man of uncommon physical strength and great confidence ordered the men to cut the painters from the boats and to cut telephones wires from The crossing of the Litani river the poles along the road and knot them into a long rope. With this rope Corporal Haddy,5 who declared that he was the strongest swimmer, waded into the Litani, and, though hit by a fragment of a mortar bomb, swam on and struggled to attach the rope to a tree on the opposite bank. Seeing that Haddy was becoming weak Lance-Corporal Dusting6 swam across to help him, while Hearman collected volunteers to take the first boat over. Corporal Walsh7 and eight men of Lieutenant Sublet’s8 platoon manned the boat – Privates

“Pud” Graffin,9 Len O’Brien,10 All Ryan,11 “Chook” Fowler,12 “Bobby” Wilson,13 “Blue” Moloney,14 “Chummy” Gray15 and Frank Moretti.16 All of them, like the remainder of the platoon except the commander and his sergeant, McCullough,17 had come from Kalgoorlie, and had been to school together. They had never been in a boat before and each was laden with all his gear and 300 rounds of ammunition. With difficulty the men persuaded Hearman not to enter the boat; there was very little freeboard, and the addition of so heavy a man, they thought, might have sunk it. Once they were out in the stream the machine-gun fire went over their heads, although mortar bombs were bursting on the water. They were hauled across without casualties. They landed on the north bank, spread out and advanced, bombing French posts concealed in bamboo thickets.

As the remainder of Sublet’s men crossed, mortar bombs were falling among the men on the south bank. One bomb killed Johnson and wounded Hearman and the two remaining platoon commanders, N. B. G. Meecham18 and W. G. Symington.19 Although he was hit in four places, Hearman carried on until he was hit again. Sublet, the only surviving officer in the company, then – about 6.30 – had his whole platoon plus a few other men of the boat-carrying party on the north bank, whence they moved briskly through the bamboo and into orchards beyond, driving the defenders before them until they held a bridge-head about 400 yards in depth. Because of the heavy casualties among officers, and because the French fire on the crossing place now became intense, there was a long delay before more men crossed to join Sublet. A second platoon of this company under Sergeant Phillips20 crossed first increasing the number of men on the north side to about fifty.

MacDonald had now ordered Horley’s company forward, and the men charged down to the river at the double through the mortar and machine-gun fire. Using Sublet’s boat Horley led the way with six men, and the remainder followed six at a time until seventy were across. Soon

afterwards two French destroyers stood close inshore and shelled the Australians north and south of the river until guns of the 2/4th Regiment began to reply, whereupon they threw out a smoke screen and hurriedly departed.

The French destroyers were the Guépard and Valmy. Admiral King led his squadron in search of them but they had gone when it arrived. He left four destroyers off the coast and, in the afternoon, these saw the Guépard and Valmy off Sidon. In a running fight the British destroyer Janus was hit and the faster French ships made off to the north.

While Sublet’s men, who had come under the naval fire, engaged French posts forward of the bridgehead, Horley sent his platoon commanders back to MacDonald to report how matters stood and ask for artillery and mortar fire to support a flanking attack by his company. (By this time Signalman Bright,21 working under fire, had got telephone lines across the river.) Captain Gaunt,22 with Lance-Bombardier Murphy23 and three other men of the 2/4th Field Regiment, had established an observation post overlooking the river, and effective fire was directed against enemy positions. Early in the afternoon, after an artillery concentration lasting ten minutes, Honley’s two platoons across the river – Lieutenant Atkinson’s24 and Lieutenant Elphick’s25 – attacked with swift success. The supporting artillery fire, by six 25-pounders, was very accurate, and in spite of the fact that the advance was over ploughed land offering no cover and against well-wired enemy posts, there were few casualties. One of those who were hit was Private Colless,26 who was severely wounded while cutting the wire in front of the French positions but finished his job. Corporal Wieck27 and Corporal Duncan28 went forward and cut the wire blocking their sections. In twenty-five minutes the West Australians had overrun the enemy positions (they were manned by Algerians) on the ridge dominating the river, killed about 30, taken 38 prisoners and captured 11 machine-guns at a cost of 3 men wounded.

Encouraged by this success Horley decided to work left along the ridge against the French posts with which Sublet’s men were exchanging fire. After a brief artillery bombardment his men again advanced and captured these posts, taking twelve more prisoners, a 75-mm field gun,

and two machine-guns. One of the prisoners declared that a fresh company of his battalion of the 22nd Algerian Regiment was on the next ridge, whereupon Horley and Sublet (whose platoons were now led by sergeants or corporals, among whom McCullough had been “an inspiration”) placed their men ready for a possible counter-attack. It was then 4 o’clock in the afternoon.

In the meantime, on the flat coastal strip on the left, Keyes’ group of commandos had advanced to the river where they came under intense fire. Men of Caro’s company of the 2/16th set out to carry boats forward to them. In the heavy fire, which had caused severe losses – about 25 per cent – among the commandos and the boat parties, only one boat reached the bank, and with it a gallant lance-corporal, Dilworth,29 and Private Archibald30 ferried two boat loads of commandos and Australians across. There, about noon, they captured a strong redoubt commanding the river and took thirty-five prisoners. By the middle of the afternoon Keyes and his men and one of Caro’s platoons were across. About 4 p.m. Stevens sent Captain Longworth,31 a forward observation officer of the 2/4th Field Regiment, to Caro with orders that Caro should attack and capture the high ground on the right of the coast road just north of the river, with artillery support directed by Longworth. After seeing Caro, whose men were now extremely fatigued, Longworth agreed, as an initial move, to take his party across the river to support the force already on the other side.

On our way to the mouth of the river (wrote Longworth) we passed what remained of portion of the gallant S.S. Battalion which had been met by a murderous hail of steel and H.E. from French 75’s, mortars and heavy machine-guns. Their dead literally littered the beach.32

On the other side of the river Longworth found Keyes “nonchalantly perched ... in full view of the enemy”, and his signallers strove, at first without result, to speak to their guns by wireless. Caro had now brought the remainder of his company across the river; about 5.30 p.m. Longworth’s signallers got through to their command post, and later learnt that a general attack, with artillery support, was to be made at 9.30 p.m.

Colonel Pedder’s commando group, of which Keyes’ group was a part, had landed about a mile and a half north of the river in the midst of well-sited French positions. After confused fighting in which Pedder and two other officers were killed, one party surrendered; another, having captured prisoners, worked its way back to the Litani to join the Australians. More’s group, after landing two and a half miles north of the river, was

engaged in confused fighting round Kafr Badda and finally surrendered at Aiteniye early on the 10th. The commando landing had experienced bad luck, but also it was ill-arranged. Stevens had seen Pedder for only a few minutes at Nazareth and they had then had no time to coordinate their plans, and each was left with a feeling of uneasiness. The position was now such as to cause Stevens some anxiety. The only link with the half-battalion on the north side of the river was the flimsy ferry, and the engineers could not bridge the stream except under cover of darkness. At 6.45 p.m. Stevens issued orders (referred to above) that from 9.30 the 2/16th, with a company of the 2/27th, should clear the high ground ahead of its leading companies, while his engineers built a bridge of folding boats across which the remainder of the 2/27th would cross, occupy the ground north-east of the road and push on as opportunity offered.

In the meantime Horley had been pressing on. About 6 p.m. a third company of the 2/16th, hitherto covering the crossing from high ground overlooking the south bank, began to cross. Its commander, Captain Hopkinson,33 had been wounded early in the morning, and Captain Mackenzie34 now led it. When it reached the north bank Horley sent it into a new advance whose aim was to overcome the French posts on the western side of the ridge. The men moved off at 7.30, but were soon stopped by heavy machine-gun fire which killed one man and wounded a platoon commander, Lieutenant Langridge;35 but Horley himself and Corporal Sadleir36 stalked to the rear of the French machine-gun post and captured the six men manning it. By dark the attackers had reached the top of the ridge at a point about 500 yards south of “the Barracks”, a large building right of the road, having taken seventy prisoners including five officers.

Unfortunately at this stage the telephone failed with the result that Horley could not inform MacDonald where he had got to. He knew that, at 9.30, the artillery would fire on the heights in preparation for an attack on a position he already partly occupied, and yet he had no means of stopping that fire. Consequently he withdrew his leading men to the foot of the hill, intending to reoccupy the slopes next morning. He then hastened back to the headquarters of his battalion, where he was told that the planned attack must go on. In the confusion, and with such flimsy communications, the extent of the success of the men across the Litani was probably not fully appreciated by those on the south bank. Soon afterwards British ships mistakenly bombarded the ridge, necessitating a further withdrawal of Horley’s force.37

At 9.30 the planned artillery fire descended on the high ground beyond the river; in half an hour the guns fired 960 rounds. On the right Horley’s force reoccupied the positions it had gained early in the day. On the left Major Isaachsen’s38 company of the 2/27th had been brought forward, and the men ferried across the river six at a time in the single folding boat that was available. When two platoons were across they attacked into sharp mortar and machine-gun fire. After a prolonged fight a whole company of Algerians surrendered to the South Australians, who rescued some twenty of the commandos. In the “Phoenician Caves”, dug into the cliffs above the road about a mile beyond the river, large quantities of food, weapons and ammunition were found. The river was bridged during the night by engineers of the 2/6th Field Company under Lieutenant Watts39 helped by eighty infantrymen working as labourers. At 5 a.m. on the 10th, men and vehicles of the 2/27th began to cross this pontoon bridge, 400 yards east of the demolished stone bridge.

Stevens’ orders for 10th June were that the 2/27th should advance along the main road with Lieutenant Mills’ squadron of the 6th Cavalry probing ahead, while the 2/16th cleared the hills on the right. The Cheshire was still moving forward in the rugged hills farther inland from Srifa towards Kafr Sir which they entered, after a skirmish, that day. Mills’ carriers crossed the pontoon bridge at 6 a.m. and whirred north. One troop was sent inland along the road to Imsar, while another led the advance along the main road. This troop met and dispersed a party of Spahis with a line of pack mules, and then came under fire from French armoured cars which were driven off with anti-tank rifles. By 10 a.m. the carriers were among the buildings south-west of Adloun and had been fired on by light guns and their crews had sighted two tanks. Mills brought forward a 2-pounder to deal with the tanks but, when they did not return the fire, he drove forward and found that four French tanks lay abandoned though apparently in good condition. However, when a troop drove forward to locate a gun which had fired from a position between the road and the sea, the leading carrier unwittingly ran to within a few yards of the anti-tank gun and a machine-gun and two members of the crew were killed and the third wounded and captured. Sergeant Stewart40 in the next carrier astern poured about 2,000 rounds into the French position from his Vickers gun, and, pursued by shells, the surviving carriers withdrew.

Lieutenant Glasgow’s41 troop of three carriers which had turned off towards Imsar met fifty white French troops with two idle field guns at Kafr Badda, only half a mile from the main road. After the cavalrymen

had fired a few bursts the enemy gave up the fight, half of them making off and half surrendering. When the captives had been handed over to provosts, Glasgow drove back along the road and overtook the remainder of the Kafr Badda party, but could not capture them because they ran for the shelter of rocky hills where carriers could not follow. Thence the carriers continued to Imsar, where the head man of the village said that the French had departed the evening before.

In spite of such evidence as the cavalry had seen of a withdrawal north of the Litani, the French posts during the morning were still holding out firmly in the hill positions just east of the coastal road, south of the cavalry patrols, and both the 2/16th and 2/27th were meeting opposition and suffering casualties. (Sublet was wounded here.) The enemy was still in strength particularly at El Ouasta, where a patrol reported that the enemy had thirteen machine-guns emplaced, and whence the 2/16th was being enfiladed. However, this area was heavily shelled both by the field artillery and by the ships off shore and at length the enemy abandoned it. At the end of the day the enemy had been cleared from the coastal plain as far as a line astride the road south-west of Adloun, but was evidently in some strength there and at Innsariye; the lateral track had been explored as far as Imsar; and the British horsed cavalry were at Kafr Sir and that day made contact with the 21st Brigade at Qasmiye.

After the battle the West Australians reached the conclusion that if they had been holding the strong natural defensive line of the Litani and the French attacking it, the attack would have failed. Their achievement was one on which they could look back with justifiable pride. Despite the demolition of the bridge and the failure of the ill-planned and costly landing by the commandos, the coolness and enterprise of their leaders and the skill and dogged courage of the men had forced a crossing and breached cunningly-concealed, well-manned enemy positions armed with many mortars and machine-guns. A weakness that was discerned in the French defence here and later was their failure to deny the attackers the approaches to the obstacle they were defending and adequately to defend the area on the seaward side of the road, probably for fear of naval bombardment.

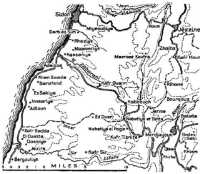

In the Merdjayoun sector the deadlock persisted. On the afternoon of the 8th, having learnt that the 25th Brigade was meeting determined and

skilful opposition; Lavarack had offered Cox from his divisional reserve the remainder of the 2/25th Battalion, of which Cox already held two companies, and suggested that at dawn on the 9th he use this reinforcement, with the 2/33rd Battalion, in an effort to take Merdjayoun from the east. There was little time, however, to bring up the new battalion and organise an attack so soon. The 2/25th had assembled in the Dafna area, whence one company had already gone forward to Metulla on the night of the 8th–9th; next morning, with two companies, it moved up to the right of the 2/33rd south of and 1,000 feet below Ibeles Saki.

Meanwhile early on the 9th Cotton’s company had advanced against Fort Khiam, after a sharp artillery concentration ordered by Brigadier Berryman, Lavarack’s artillery commander, and found it abandoned. Cotton moved past the fort into the village, but was held at the northern end until about 5 p.m. when French shells set fire to haystacks in a threshing area there just behind his leading men, causing such heat and smoke that they withdrew to the southern end of the village. Throughout the day the 2/31st was still held by enemy fire from Khirbe and west of it.

It was on the morning of the 9th that the first news arrived at Porter’s headquarters of Sergeant Davis’ patrol, whose task, it will be recalled, had been to save the bridge over the Litani south-west of Merdjayoun. The patrol itself did not arrive until that evening. At midnight on the 7th Davis, with four riflemen, two engineers and two Palestinian guides had set out from Metulla. After having climbed into French territory across country for more than three hours without being detected, the patrol passed a telephone line, which Davis cut. Twice they were close to French posts or sentries but were not detected. When they were only a few hundred yards from their objective one of the guides accidentally pulled the trigger of his revolver and wounded himself in the hip, but evidently this shot was not heard by the French. The wound was dressed, and the Palestinian marched on. “I go on,” he said, “show you the bridge. You (he made the motions of bayonetting), then I lie down.”

At 4.30 a.m. the patrol reached a small bridge over the Litani river about 400 yards south of the main bridge. Here a dog began to bark, and a sentry walked on to the road. The Australians flattened themselves on the ground. Davis decided to overpower the sentry without opening fire. However, when he and his men were about 10 yards away, the Frenchman called out loudly, slipped a round into his rifle, and after standing with it at his shoulder for a few tense seconds with visibly trembling hands, fired at the advancing Australians, who were then only two or three yards away. His shot missed. Almost simultaneously Lance-Corporal Hopkins42 fired, and then five others. The sentry staggered across the road, and, with two other French soldiers who had run out to join him, disappeared in a gully.

After a brief exchange of shots, Davis led his men charging with fixed bayonets towards a rough shelter which served as a guard but on the eastern end of the main bridge. In the doorway of the but were two French soldiers in pyjamas hastily thrusting a magazine into a light machine-gun. They surrendered, and Davis with one man ran across the bridge to a blockhouse at the other end of it where two more men hurried out and surrendered after Davis had tossed in a grenade.

Davis and the two engineers found the wire that led to the demolition charges in the bridge, disconnected it, and threw wire and detonators into the river. He then led the patrol, with its four prisoners, and with a captured machine-gun and five captured rifles, to the side of a steep hill overlooking the bridge from the west. It was now a little after 5 a.m. Davis’ plan was to hold high ground from which to launch an attack on the bridge when his battalion approached. By this time the invasion proper had begun. Lying on the hillside they could hear the whistle of shells, the continuous rat-tatting of machine-gun fire, the drone of aircraft engines. In the valley below they could see “countless civilians” hastily moving north away from the battle, and French troops moving south towards it. To mislead the French below into believing that he had a considerable force, Sergeant Davis, a born soldier, made his men crawl from one rock or bush to another and allow themselves to be seen now and then. By 6.30 a.m. fifty-seven French vehicles were lined up along the road. These vehicles turned and departed. About 7.30 a.m. the French stationed eight men on the ridge east of the river, evidently to defend the bridge against attack by Davis’ patrol, and later more French troops were moved on to the high ground above the bridge. At 3 p.m. the French demolished the small bridge and at 4 p.m. the main bridge.

About an hour after the last explosion an Australian soldier appeared on the road below Davis’ party, walking unconcernedly along with an anti-tank rifle on his shoulder. Davis hurried down to the bank to speak to him. It was Corporal Feltham,43 of Davis’ battalion, who had been hit on the head in front of Khirbe the night before, had become separated from his unit, and was now, he thought, marching forward to rejoin it. Davis told him he was far behind the French lines and called to him to go downstream to find a crossing. At dusk Davis moved his men, and his prisoners, to a point on the hills about three-quarters of a mile below the bridge. Next morning they crossed the river and moved south along the main road. At length they saw Feltham, now with five other Australians on the other side of the river. One of Davis’ men swam the river carrying 50 or 60 feet of the heavy gauge telephone wire which Davis had cut two nights before. It was secured to a tree and, using it for support, Feltham and his men crossed. The imperturbable Feltham reported that, after having failed to find a ford across the river the previous day, he had spent the night on its banks and eventually found his way back to his battalion, and there obtained permission to lead out a party to rescue

Davis and his party and guide them home. Together the Australians, still with their prisoners, made their way along the Litani, across the northern slope of the hill on which Deir Mimess stands (where they came under some mortar and machine-gun fire) and onwards, round the edge of the battle, to the road junction where Colonel Porter had his headquarters.

The events of the 9th had emphasised the difficulties faced by Cox’s brigade: his battalions were on ground that offered little cover, and at night from 11 o’clock onwards the moon was bright. A handful of infantry tanks could have carried the attack forward, but his light tanks were very vulnerable to the fire of French anti-tank guns. On the other hand the French possessed a force that seemed as strong as his own and were in prepared positions well supported by artillery. Their posts were carefully sited to give enfilade fire and were defiladed from the front. Scattered over the area were small cairns of stones erected to mark the range for the French gunners and mortarmen. Even to send food to the forward infantry companies was laborious and dangerous.

Lavarack had watched Berryman’s effective artillery concentration which had subdued the garrison of Fort Khiam and, that afternoon, he withdrew the 2/6th Field Regiment from Cox’s command and placed Berryman, with the 2/6th and 2/5th Regiments under his control, in support of Cox’s infantry for a set-piece attack on Merdjayoun, not next day but on the 11th, to give time for systematic preparation.

On the 10th one attempt seriously to test the enemy’s strength was made, and that on Porter’s front. Early in the afternoon, at Berryman’s suggestion, a detachment of the 6th Cavalry consisting of one light tank and six carriers under Lieutenant Millard was ordered to advance towards Khirbe to draw their opponents’ fire. The plan was that Lieutenant Florence44 should lead a troop of three carriers along the road on the Khirbe ridge until the ground allowed him to deploy, while Millard led his carriers forward and deployed on Florence’s right, and Sergeant Groves gave supporting fire from a light tank hull-down near an observation post whence artillery fire could be directed against the French when they revealed themselves.

Without opposition Florence’s troop reached the foot of the hill on which Khirbe stands. Millard’s carriers were deploying when the French opened with machine-guns, mortars and an anti-tank gun. In the first burst Corporal Oswell,45 Millard’s wireless operator, was wounded in the arm and could not send out his orders. Millard gave the hand signal to retire. Florence’s troop retired under heavy fire while Millard shot at the French positions with his Vickers gun. As he turned to run back to a more sheltered position the track of Millard’s carrier was blown off by a mortar bomb. Under hot fire Millard and his crew dashed for the cover of a low stone

wall. The driver, Corporal Limb,46 ran back to the damaged carrier, manned the wireless and tried to call for artillery support but the set had been put out of action by the explosion. The Australian artillery had rapidly and accurately begun shelling the positions round Qleaa and Khirbe knocking out the French anti-tank gun.

Seeking to rescue the crew of the disabled carrier Florence drove his own one forward down the road leading to the village. He ran the last 100 yards down the centre of the road towards the abandoned carrier (which was still under heavy fire) brandishing and firing his revolver and calling out to the crew. Finding it abandoned he returned to his carrier, while Sergeant Martin,47 who had driven his carrier behind a rise, advanced the last couple of hundred yards across open ground under fire to the wall where Millard and his men had now been sheltering for an hour and a half. He guided Millard and his crew, including the wounded Oswell, along the wall to a position whence it was possible to reach cover by making only a short concerted dash across the open. All but two of Millard’s six carriers were hit and six men out of the eighteen in the carrier crews were wounded. At 9 p.m. Cox informed Millard that he wished him to adhere to an earlier order to support the infantry attack planned to begin at 2 o’clock next morning. Millard pointed out that he now had only one tank and one carrier fit for action, and eventually was released from the task.

It will be recalled that on the night the invasion began the right company of the 2/33rd (Captain Bennett’s) had been sent through the hills to occupy Ferdisse. Since then it had been out in the blue; little was learnt about Bennett’s company by battalion headquarters, and Bennett knew less of how the battle was going round Khiam and Merdjayoun. On the first night Bennett and his men had difficulty in finding the track to Chebaa and it was not until daylight that they were sure where they were. All that day, without seeing a French soldier, they marched into Syria over the rock-strewn hills, and came within sight of Hebbariye some hours after nightfall. The plan was that Bennett’s company would take four hours to reach Hebbariye; in fact it took twenty-four. Outside the village Bennett met some native Syrians who had lived in America, and they told him that French cavalry had been in Hebbariye that night but evidently did not know of his presence in the area. Bennett’s scouts probed round the village in the dark, and, at 8 a.m. on the 9th, he moved off to occupy Ferdisse, and in accordance with his orders establish his company astride the main road to the west of it.

Approaching Ferdisse his men were fired on by a machine-gun sited to the north of the village, so Bennett decided to move on with two of his platoons, leaving one covering his rear in the Hebbariye area. The two platoons advanced into Ferdisse under fire, and then Bennett ordered his

remaining platoon forward over the hill south of Ferdisse. As they reached the summit they saw a dozen Frenchmen with machine-guns loaded on pack mules moving south towards Ibeles Saki. Still under fire from distant French machine-guns Bennett moved his men towards the main road and established them on the high ground each side of the track just short of its junction with the main road.

Next day (the 10th) Bennett still faithfully awaited the arrival of the rest of his battalion, which was in fact four miles away to the south. A French force, which he estimated to be a company, came leisurely down the main road from Hasbaya, deployed and attacked the platoon dug in on the northern side of the track. Three attacks were made, one at 10 a.m., another at midday and a third at 4 p.m. Each time Lieutenant Copp,48 a cool and skilful young regular soldier, let the advancing Frenchmen – all white troops – attack up hill until they were within 50 yards of his posts, then opened fire, and drove them back leaving dead and wounded men behind. As the final French attack was sent in, a body of about fifty horsed cavalry attacked Bennett’s rear at Ferdisse (evidently having come over the hills from Hasbaya). They were within 200 yards of his men round the village and had dismounted before they were seen by a section posted just south of the houses. This section opened fire and routed the Frenchmen, some of whose horses bolted and went thundering along the valley towards Bennett’s main position.

Next morning (11th June) Bennett’s force was subjected to two more attacks from the main road. In the course of one of these the French forced an entry into Ferdisse, cutting off his only supply of water and capturing his six wounded men and the stretcher-bearer who was with them. The rear platoon stayed where it was, overlooking Ferdisse from north and south. Bennett now had French troops on the main road in front of him and in the village behind him. At this stage a Syrian came to his headquarters and announced that the French commander wished to see him. Bennett sent back a message that if the French commander wished to see him he could come to his headquarters, and under escort. There was no reply.

On the fourth day (the 12th) there were no attacks on Bennett’s beleaguered company, though the French surrounding him fired at intervals during the day and horsed cavalry patrols probed round his area. About 11.45 one horseman – an African native – rode, perhaps unknowingly, right into Copp’s position. Copp allowed him to come close and then shot the horse. Corporal Marshall49 ran out to capture the rider, but the native resisted and a fierce wrestle began while the Australians cheered their champion. Marshall broke away, whereupon his opponent advanced on Private Norris50 who shot him.

Bennett had now held his position overlooking the road for four days. He had no news from battalion headquarters since he had spoken to them by wireless from Hebbariye on 8th June, though he had sent three runners back.51 When he set out his men had had twenty-four hours’ rations and full water-bottles, but since 9th June, and it was now the 12th, the men had had nothing to eat but a little local “mungaree”.52

Bennett decided to retire on to the remainder of his battalion after dark that night. He instructed Copp and Dwyer53 to take their platoons south-wards across country, moving separately on compass bearings, while Lieutenant Marshall’s54 covered the withdrawal. Thus while Copp and Dwyer steered their way southwards on parallel courses, Marshall “some-how managed” to march out along the track on which he had come; and Bennett and his headquarters went through Rachaya el Fokhar and Kheibe. The moon was just rising as the headquarters party set off. As Bennett crossed the track a French patrol came along the road and sat down a few yards from him and his batman. The Australians sat quietly for a while, then crept up the hill among the rocks, unobserved. The head-quarters party camped below Rachaya el Fokhar that night, marched all next day and, after dark, reached Monaghan’s headquarters where they found that the three platoons had arrived during the day. All Bennett’s men returned safely except the six wounded men and stretcher-bearer captured in Ferdisse. Monaghan’s use of this company had been very bold – perhaps too bold in view of the rawness of the troops and the lack of signal communication. Bennett was given a task that would have better fitted a whole battalion.

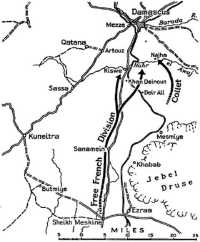

On the desert flank Colonel Collet’s cavalrymen, having followed the 5th Indian Brigade to Sheikh Meskine, advanced into the volcanic boulder country to the east where horses were more useful than vehicles, and on the 10th reached Najha on the Nahr el Awaj where he captured some prisoners. He then encountered a force of Senegalese infantry with armoured cars and tanks, and fell back about six miles to a good defensive position. There he was attacked on the 11th but, with his one anti-tank gun, succeeded in checking the enemy.

The leading troops of the main Free French column went through Sheikh Meskine on the morning of the 9th, the vanguard consisting of marines and Senegalese; Lloyd lent them a battery of the 1st Field Regiment and a troop of light anti-aircraft guns to compensate for their shortage of artillery. By nightfall General Legentilhomme had occupied Khan

Deinoun and Deir Ali and was in touch with the Vichy outposts. There he awaited reinforcements during the 10th; and on the 11th, with a Senegalese battalion, attacked towards Kiswe which was defended by Moroccans about equal in strength to the attackers.

General de Verdilhac was greatly disturbed by the rapid Free French advance towards Damascus and decided to give battle on the Nahr el Awaj position. He ordered the 6th Chasseurs d’Afrique with their tanks and the II/6th Foreign Legion into that area on the 9th, and on the 11th added the 7th Chasseurs d’Afrique and the I/6th Foreign Legion. Thus by the 12th six battalions including two of the Foreign Legion, the most valued infantry, and most of the tanks were in the area between Mount Hermon and the desert. Three additional battalions, mainly Tunisian, were in the Jebel Druse area.

The enemy force defending the Litani area appears to have included part of the 24th Colonial Regiment, sent south from Tripoli, and companies of the 22nd Algerian and the 6th Foreign Legion, supported by seven batteries of artillery. De Verdilhac sent the IV Battalion of the Foreign Legion to the coastal sector on the 10th.

Indeed, in the opening days, de Verdilhac deployed in each sector a force stronger in infantry than that of his opponent; in addition he had a substantial reserve of armour; and, whether he chose to defend or attack, the terrain would favour him rather than the invader.