Chapter 21: Damascus Falls

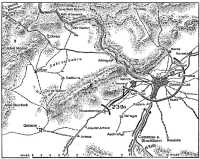

Convinced that the best means of countering the French forays across his lines of communication would be to press on to Damascus, Brigadier Lloyd had issued orders for a renewed attack before he knew even that Kuneitra had been recaptured from the enemy. On his right the Free French contingent was to advance along the Deraa road to Kadem, as a first step towards entering Damascus from the south. On the left the 5th Indian Brigade, on the night of the 18th–19th, would move on foot along the Kuneitra road to Mezze and cut the road from Damascus to Beirut, now the defenders’ main lateral artery. The French marines and two detached companies of the Indian brigade were to form a defensive flank from Artouz to Jebel Madani. The enterprise to which Lloyd committed the main body of the Indians was bold in the extreme, and typical of the irrepressible leader who conceived it. The Indian brigade had lost its British battalion at Kuneitra; on the 17th when he gave the order the enemy was astride one of the two roads behind him, and was close to the other; his remaining battalions were below strength as a result of casualties and detachments; they were fatigued and were outnumbered by the defenders. Notwithstanding, Lloyd proposed to make a night advance of about 12 miles, and seize a vital position for which the enemy would certainly fight hard. But if all went well – and Lloyd was evidently one of those who assumed that a determined stroke would win success – the French would have only one line of retreat, namely the road leading north-east to Horns.

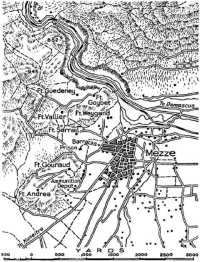

Lloyd’s order was elaborated by Colonel Jones, whose detailed plan provided that one company of the Punjab, the leading battalion, would deal with any opposition encountered on the way and that when his column reached the road just south of the heights overlooking Mezze from the south-west, another company of the Punjab would seize them. When Mezze was entered, the Rajputana would block all roads into the area and hold on.

The Indian column began to move at 8.30 on the night of the 18th, the men on foot following a route just west of the road with their twelve vehicles on the road itself. While the battalions were moving off in pitch darkness the area was heavily shelled and some men lost their way. At 10 p.m. the column came under heavy fire from Mouadammiye, which was set among many trees. Throwing grenades and shouting to one another so as to keep in touch in the darkness, the Sikh company of the Punjab attacked, while the main column marched on, keeping level with the flashing of grenades on their right. The Sikhs encountered and set fire to several tanks, useless in the darkness. There was a long fierce fight in the woods and only some 270 men reached the far edge, but the attackers had broken up a strong enemy post and the advance was able to continue.

By 11 o’clock the head of the column was through the enemy’s first line. However, it was difficult for the leading men to keep in touch, and the trucks, outstripping the troops, ran into a French road-block guarded by an anti-tank gun. The gun opened fire and disabled some of the trucks, and the surviving vehicles were eventually sheltered in olive groves where they were pinned down by the fire of enemy guns. They did not rejoin the battalions. Meanwhile the infantry, overcoming some posts and bypassing others, moved on past the aerodrome and at 4.15 in the morning were at Mezze “after a 12-mile march, against opposition, over unreconnoitred country and in utter darkness ... a military feat of outstanding brilliance”.1

The attack on Mezze itself began at 4.30 a.m. Soon the Indians were fighting among the square white buildings, and for an hour a street battle was waged in which infantrymen with Tommy guns knocked out the crews of several field guns sited to fire along the road, and yet another tank was set on fire. A company of the Rajputana moved round the village and on to the Beirut road, set fire to a petrol dump, turned back a train, beat off an attack and caused some alarm in Damascus. When daylight came, however, they themselves were attacked by five tanks and retired to Mezze.

At that village the remainder of the brigade were busy preparing defence against an inevitable counter-attack by infantry and tanks.

Roadblocks were built with timber, stones and wire. Brigade and the two battalion headquarters and a company of each battalion were established in and round a large square, two-storeyed house with a walled garden – Mezze House – on the northern edge of the village, and the wall was loopholed; the other companies took up positions in the village.2 About 9 a.m. French tanks appeared and opened fire. The Indians’ small arms kept off the enemy infantry but tanks, against which they had no effective weapon, cruised round the village firing through the walls and windows of the house. The village was shelled persistently.

All day the fight went on. At 4 p.m. one isolated company surrendered. Resistance was then concentrated in and round Mezze House; the house itself had become a hospital in which an increasing number of wounded were collecting. Medical stores were exhausted and wounded were bandaged with strips torn from sheets found in the building. The men were hungry and had no food, and ammunition was running short – because they had lost their trucks. Lieut-Colonel Greatwood3 of the Punjab was mortally wounded. At 8.45 Jones sent a jemadar and two English officers to reach Lloyd’s headquarters and report the situation. They crawled through a hole in the wall, swam a stream, clambered through a garden, over the roofs of several houses and through cactus hedges, and at 5.30 a.m., nearly exhausted, reached the headquarters of the force and made their report.

The Indian brigade had been one prong of a two-pointed attack, the other being formed by the Free French contingent on the Deraa road. The French attack on the 19th had failed completely. The Free French troops were tired and disheartened, so much so that General Legentilhomme told General Evetts, commander of the 6th British Division then coming in on the Damascus flank, that nothing would set his men moving again except the sight of British troops. Lloyd considered that the failure of the Free French attack on the night of the 18th–19th was “possibly the main cause of the heavy losses suffered by 5 Indian Infantry Brigade at Mezze”. (“Heavy losses” was a euphemism; the brigade had been virtually extinguished.) “There is good reason to believe,” he added, “that the Vichy French, threatened by the cutting of their line of retreat by the thrust at Mezze, had begun to withdraw from Damascus; but the failure of the Free French attack now allowed them to concentrate heavy forces against Mezze. ... The Free French could not mount a new attack until the afternoon of 20th June after they had been reinforced by two British anti-tank guns and an anti-aircraft gun which drove off the three Vichy tanks which had been holding up the advance.”

Early on the 20th, after the three officers from the force besieged at Mezze House arrived at his headquarters, Lloyd had sent the remaining

companies of the Punjab and two companies of French marines with the 1st Field Regiment, all commanded by Major Bourke,4 to relieve the beleaguered brigade. The gunners advanced boldly, sometimes ahead of the infantry, but, at the end of the day, they were still hotly opposed by French tanks and had not succeeded in reaching their objective.

The advance to Mezze had an influence on the conduct of the campaign that was out of proportion to the local gains or to its immediate effect on the defenders of Damascus; partly as an outcome of that advance a decision was made again to swing the main effort from one flank to the other. On the 19th General Evetts took command of all British troops east of the Merdjayoun sector and “control” of the Free French forces. Late on the 19th, General Lavarack, having learnt that further British troops might be added to his command, decided that some additional units at Damascus might turn the scale there, and asked General Wilson to alter his decision made the previous day to add the 16th British Brigade to the 7th Australian Division for the advance to Beirut, and re-allot it to the Damascus sector. Wilson agreed, but urged that the Damascus operations should be completed before the time arrived to thrust towards Beirut. At the outset Evetts’ force was in four groups: one small contingent guarding the lines of communication from Deraa north to Kiswe; the 5th Indian Brigade advancing, with the Free French, on Damascus; the 16th Brigade with one battalion-2/Queen’s – at Kuneitra and the 2/Leicesters at Rosh Pinna (the third battalion having been detached to the 21st Australian Brigade); and Lieut-Colonel Blackburn’s force. Evetts’ headquarters were at Rosh Pinna and those of Lloyd and Legentilhomme at Khan Deinoun, eight hours’ drive away.

At 11 a.m. on the 20th Evetts sent a message to Lavarack that heavy fighting continued at Mezze, and added:

We are optimistic of success but I wish to point out that should the action go against us the 5 Inf Bde will be seriously depleted in both personnel and material and reduced to approx one Bn. Other portion of 5 Inf Bde are just about to start operations to clear front of Free French forces in neighbourhood of Aachrafiye; if successful Free French will probably be in a position to advance towards Damascus. I still consider and am supported by [Legentilhomme and Lloyd] that it is essential to move up the 16 la Bde Gp as soon as possible by the Kuneitra-Damascus road. Hope you have been able to arrange this as any cessation of pressure on our part will in my opinion prejudice the whole success of the operation.

Lavarack promptly telephoned Brigadier Rowell, his chief staff officer, who was at General Allen’s headquarters, informing him of the decision to divert the main effort temporarily to Damascus and to send the 16th British Brigade there. He asked him to find out whether Allen could hold his positions without the 16th Brigade (though he would retain one of its battalions – the 2/King’s Own). A few minutes later, while waiting for a reply, Lavarack was telephoned by Wilson who said that General Catroux had given him a gloomy picture of the force attacking towards Damascus.

Lavarack replied that Evetts was confident but was asking for the 16th Brigade and he intended to let him have it provided Allen would spare it. Allen declared that by active patrolling he could hold his positions with two brigades; consequently his division was given a defensive role. That evening Lavarack informed Evetts that the central and coastal sectors had been denuded of infantry reserves to enable him to capture Damascus; but, as soon as he had done this, the 16th Brigade – and the Australian 2/3rd and 2/5th Battalions which he had also placed under Evetts’ command – should be ready to move “elsewhere”.

At length, by the night of the 20th, Evetts’ force had been increased until it included two brigades (5th Indian and 16th British) and three additional battalions (2/3rd and 2/5th Infantry, and 2/3rd Machine Gun); and, for the time, attention was concentrated on the effort, already in full swing, to take Damascus.

Late on the 18th June, the day on which the Indian brigade had begun its bitter fight at Mezze, the 2/3rd Australian Infantry Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Lamb) had begun entraining at Majdal in Palestine for Deraa where it was to form a “stop” on the Damascus-Deraa road. A week earlier, one of the battalion’s four rifle companies had been sent to Sidon for garrison duty, and, on the 18th, the battalion had transferred 100 men to help to re-form the 2/1st Battalion which had lost all but a handful of its men in Crete. As a result of these subtractions the 2/3rd possessed only 21 officers and 385 men, and some of these men had not fully recovered from privations in Greece and Crete.

The journey to Deraa took seventeen hours. From Haifa the men travelled in eight cattle trucks through the stifling heat of the Jordan Valley – the temperature at Samakh was 130 degrees – and on to Mzerib. There the grade was too steep for the engine to haul the train up in one piece and, consequently, the train was divided into two parts. When the engine was returning for the second section its brakes failed and it crashed into the trucks, injuring three men. At Deraa at dusk on the 19th the battalion boarded civilian buses and was joined also by its own few vehicles which had travelled from Julis by road. Thence the little column drove all night and, along a road that was broken in many places by bomb craters, little more than a walking pace could be achieved. Two of the trucks overturned during the 50-mile journey. At Khan Deinoun, where the column arrived in the early morning of the 20th, Lamb was informed that his battalion was to join the depleted 5th Indian Brigade, replacing the 1/Royal Fusiliers as the British battalion in that brigade. The leading Australians moved forward in trucks to Mouadammiye on the Kuneitra road at 11 a.m., and dispersed and dug in on the right of the road about one mile south of the aerodrome under sporadic shell-fire. Ahead of the Australians a battery of the 1st Field Regiment was firing – it was part of Major Bourke’s column vainly trying to relieve the remnant of the Indian battalions in Mezze.

General Evetts was convinced that the Free French units were weary and disheartened; this day he wrote to Brigadier Rowell that they had “little or no desire to go on killing their fellow Frenchmen and it is doubtful whether they can be persuaded to advance even against feeble resistance”. Evetts summoned Blackburn to his headquarters at Rosh Pinna and gave him orders to assist the Free French forward to Damascus. As a result, Blackburn, whose “battalion” comprised one company (Captain Gordon’s), one platoon of another company and five anti-tank guns, advanced to Colonel Casseau’s Free French force at the Jebel el Kelb. At Casseau’s headquarters (where Brigadier Lloyd was urging Casseau to push on so as to relieve the pressure on his brigade at Mezze) Blackburn learnt that the Free French troops were very weary after eleven days of fighting in the heat and sand and had come to a standstill; the Vichy force had tanks and armoured cars and they had none. He told Casseau that his little force was fresh and eager and (which particularly pleased Casseau) that it possessed anti-tank guns. At Blackburn’s urging Casseau agreed to advance at 5 o’clock that afternoon, whereupon Blackburn ordered Gordon to deploy his four platoons astride the road and inspire the French to attack boldly. Gordon promptly placed most of his company in the French line on the heights east and west of the road and sent one platoon forward 1,000 yards ahead of the French infantry on the road itself. So far as Gordon could discover the Free French advance was being opposed only by the fire of one field gun and a small force of infantry – perhaps a weak battalion.

Half an hour later Casseau’s infantry, mostly Africans, began to advance, with Casseau himself driving his car slowly along the road level with the leading men. However, when the infantry drew up to the machine-gunners they halted, and it was not until Blackburn had sent his men to a new position 300 yards forward, and they opened fire again, that the Free French troops moved forward. In this fashion progress continued, the machine-gunners leading the tired and dispirited African infantry until they had advanced three miles and were on the outskirts of Damascus. Here there was stronger opposition from Vichy troops occupying a large building and sniping from among the trees in the plantations, and some Vichy tanks appeared. The advance was halted for the night, and Gordon’s company withdrew to a position behind the infantry to form a reserve line in case the French troops were forced back during the night.

Meanwhile, in the afternoon of the 20th, Lloyd had ordered Lamb of the 2/3rd Infantry to attack over the high ground on the left of the road, that is to say on the left of the Indians and the gunners advancing towards Mezze. He did not then know that the Indians in Mezze had been overwhelmed. All night of the 19th–20th the Vichy French had continued to attack Mezze House and, from 1.30 p.m. on the 20th, they shelled it with field guns at point-blank range. An attack which followed this bombardment was driven off, but when it was over the Indians’ ammunition was exhausted. The defenders could then hear the fire of their own troops to the south and, hoping to delay the attackers until help arrived, they

sent out an emissary to ask for an armistice so that they could remove the wounded. However, when the French saw the white flag advancing, they assumed it meant surrender and rushed the building. News of this set-back reached Lloyd later in the day. It signified that the force astride the Kuneitra road consisted only of a handful of Indian infantry, some French marines (who had not succeeded in winning Lloyd’s confidence) and part of the 1st Field Regiment. In fact the 5th Indian Brigade had now been reduced to little more than a few depleted companies of British and Indian infantry, and the newly-arrived Australian battalion, which was at less than half strength. Unperturbed, Lloyd decided to continue to attack, but with the Australian battalion spread more widely across his front. His new orders were that one company of Australians was to cut the Damascus-Beirut road, while the remainder of the battalion advanced on to the steep bare heights which overlook the Kuneitra road from the west.5

This ridge, one of the foothills of Mount Hermon, is a huge wedge thrusting towards Damascus from the south-west. On the east it falls steeply into the plain along which travels the Kuneitra road; on the north it forms the southern wall

of the Barada Gorge along whose narrow floor run the road and railway to Beirut. On top of it the French had built a group of stone forts and had given them the names of distinguished soldiers – Andrea, Gouraud, Goybet, Vallier, Weygand, Guedeney, Sarrail.

It was 5.30 p.m., and the Australian companies were already forming up for the attack arranged earlier in the day, when Lamb arrived with these new orders. The change of plan caused some delay and it was dusk before the companies set off. On the right Captain Parbury’s,6 which was given the task of cutting the Beirut road, moved

forward astride the tributary road leading to that objective and was soon out of sight. Of the remaining companies Major McGregor’s was ordered by Lamb to take Goybet,7 the northernmost of the forts, Captain Ian Hutchison’s company to take Vallier, which lay south-west of Goybet, and the headquarters company to take Sarrail. Lamb had been informed at Lloyd’s headquarters that the Indians held Gouraud and Andrea.

As they approached Goybet after a steep climb McGregor’s men were met by fairly heavy fire and were pinned down. Hutchison, however, on his left, found Vallier empty, though there were signs of recent occupation. These included a litter of clothing and some blood-stained bandages, which the Australians took to be evidence of the effectiveness of the fire of the British artillery which had been shooting at the forts during the afternoon; and a rope made of sheets hanging over the northern wall, suggesting that the occupants had made off towards Goybet. McGregor sent a message to Hutchison asking for help, and Hutchison sent two platoons towards Goybet; in the darkness they could not find McGregor’s company but only two wounded Australians who said that they thought the rest of the company had withdrawn.

Meanwhile the pioneers, carrier crews and the signallers of Lamb’s headquarters company under Captain Mackinnon8 had occupied Fort Sarrail where Lamb established his headquarters about 10 p.m. Thus, at midnight Hutchison’s company was posted round Vallier, McGregor’s was to the north, having failed to take Goybet, Lamb and Mackinnon were in Sarrail and had posted a platoon under Lieutenant Gall9 about 800 yards from it on the road leading south-east. Parbury’s company was still out of touch.

After midnight Captain Mackinnon led a patrol out from Sarrail and almost immediately ran into a French force that was moving in the opposite direction. Fire was exchanged. Mackinnon tried to move forward to join Gall but his men were held by the fire of the French troops who moved round them and attacked Sarrail. In the melee which followed Lieutenant Perry10 and several NCOs11 were wounded and eventually the Australians in the fort were overpowered and led off along the road as prisoners. On their way they encountered Gall’s platoon, but the prisoners were between him and the French so that he could not fire, and at the same time another strong party of enemy troops appeared on the slope above and covered him; consequently Lamb, who was among the prisoners, ordered Gall and his men also to lay down their arms. Moving on, still in the half light, the party came upon a carrier manned by Indian troops. Lamb tried to tell the Indians that there were Australians in the party

but they did not understand and opened fire killing two and wounding Lamb himself and one other. Thereupon French troops in Fort Weygand opened fire, revealing to the Australians that the French still held this fort, close to their headquarters area. When this firing ceased the wounded colonel and some of the other Australian prisoners were escorted into Weygand and the remainder were held some distance outside it.

Thus, though the forward companies of the 2/3rd had made some progress across the fortified ridge and held one of the “ouvrages”, a French counter-attack coming in behind them had made prisoners of their commanding officer and most of his staff and headquarters company. Not all of it, however, was captured for Lieutenant Ayrton,12 who had a small party in an outpost about 400 yards from Fort Sarrail, had not been involved, yet had been a distant spectator of what had happened, and at dawn, when Lieutenant J. E. MacDonald, whom Lamb had appointed as his liaison officer at brigade headquarters, arrived and was fired on by what he imagined to be his battalion’s headquarters, Ayrton hailed him and told him what he knew. MacDonald hurried to brigade headquarters with the news that the staff of his battalion had been captured, and that he did not know where the rifle companies were.

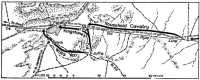

When Parbury had set out the previous night along a road of which he knew little (for his map ended short of the road junction) except that it joined the Beirut road a mile or so ahead of him, he believed that the Indian battalions were holding out somewhere to the west of Damascus and was not surprised when he encountered no opposition on the first stage of his advance. Near the road junction, however, he came under fire from French troops in some buildings there, and from the heights on the left. The company vigorously engaged the enemy. Lieutenant Murdoch13 and two men ran to one of the houses and threw in grenades, and Corporal Badans14 did the same at another house. Scouting ahead, Parbury found a track which brought him to a point whence he looked down on a wide ribbon of road – his objective. He broke off the engagement and led his company forward along it.

Darkness had just fallen when the leading platoon reached the main road along which were rows of shops and houses. Warrant-Officer MacDougal who led this platoon saw a light in one shop and the door being slammed. He raced across the road and pushed a bayonet through the door. An old Frenchman and his wife were the only occupants; no French troops were to be seen. Promptly the Australians cut down two telephone poles, placed them across the road, deployed along the sides of the road and awaited developments. Soon French vehicles began to arrive from the direction both of Damascus and of Beirut. In the darkness they pulled up at the road-block and the occupants were hustled out by the

Australians. There were occasional scrimmages, but generally the French were completely surprised. Soon Parbury and his ninety men had twenty-six vehicles jammed head to tail on the road, two cars across the railway line to block it, and held eighty-six prisoners, about one-fifth of whom were officers. The prisoners who were herded into a house and a shop beside the road were an embarrassment, and therefore Parbury, who was anxious both to be rid of them and to send back news of his progress, dispatched a trusted young sergeant, Copeman,15 to the headquarters of the 5th Indian Brigade to ask for an escort. However, it was not until Copeman had returned with information that no men could be spared, and Parbury himself had gone back to headquarters to plead more vigorously, that an officer and four men (of the 1/Royal Fusiliers) went forward and escorted the prisoners back.

Firing could be heard to the east of the Australians and there was still some fire from the heights above them; this fire, Parbury considered, was likely to make it impossible for him to hold his road-block when dawn came and the French could see more clearly. Therefore he decided to leave one platoon (commanded by Lieutenant Murdoch) on the road, while he himself led the remainder of the men up the side of the ravine to drive the French off the summit. Parbury did not know that there were fortifications there.16

It took the Australians two hours to scale the slippery side of the steep cliff in the half light. As they were climbing, an armoured car appeared on the road from the Damascus side and opened fire on them until they turned their Bren guns on to it and drove it off. Eventually they reached a ledge near the summit, whence, 150 yards ahead, they could see a formidable fort and two pill-boxes, surrounded by barbed wire. MacDougal led an advance against one pill-box and found it unoccupied, but when the main fort was approached brisk fire broke out from it. In addition occasional shells were falling round the fort, evidently from the British guns to the south. The men were very tired after the long climb; they had been hungry when the engagement began and now had no rations left and very little water. They had not eaten a hot meal since they had entrained at Julis in Palestine, two days and three nights before, and they took cover to rest. It was at this stage that Hutchison’s company appeared approaching Goybet from the south-western side.

When, about 7 a.m., Major Stevenson,17 the second-in-command of the 2/3rd, had arrived at brigade headquarters from the rear where he had been organising the battalion’s transport, Major Bourke, now temporarily in command at Lloyd’s headquarters, gave him the disturbing news that

his battalion headquarters had been captured, Parbury’s company was vaguely known to be somewhere in the direction of the Barada Gorge, and the regimental aid post was nowhere to be found (it was with Parbury). Bourke told Stevenson that the brigade commander wished Stevenson to capture Goybet as soon as possible, and it was agreed that an attack would be made after the artillery had fired on the fort from 9 to 9.30. Stevenson hoped that Parbury’s company would be found by that time. Meantime he had sent out Corporal Hickson,18 a gallant and capable member of his Intelligence section, who roamed about and by 9.15 had discovered two men lying wounded by the road and learnt the whereabouts of Parbury’s company and of the imprisoned battalion headquarters. Stevenson decided that when Fort Goybet had been taken he would attack south along the ridge and release the prisoners in Weygand.

Stevenson ordered Hutchison to make the attack on Goybet. When Hutchison and his men were cautiously reconnoitring they encountered Parbury – not at the bottom of the gorge but on the summit of the ridge, also planning to attack the fort. At length the artillery19 opened fire but, by the wrist watches of the infantry on the heights, the fire ceased ten minutes too early and, after waiting for it to continue, they attacked late, being in doubt whether to move forward or not. In the face of brisk fire Corporal Morgan20 with two men climbed to within 30 yards of the walls and tried to throw grenades through the firing slits while the French machine-guns fired over his head. A gallant veteran of the war of 1914-18, Private Scott Orr,21 was killed at the foot of the wall firing his Bren gun, and it soon became evident that the only way into the fort was through the gate. Morgan brought his men out and both companies began firing on the fort in preparation for a new attack, when, to their surprise, a French soldier emerged carrying a white flag. The nearest platoons of Australians rushed through the gate and took the surrender of about seventy-five European troops. Their commander, a captain, was dead and the only other officer, a lieutenant, wounded. The survivors said that they had surrendered because, seeing the leading Australian parties withdraw, they feared that the guns would open fire on them again. It was then about 10 a.m.

There was no need for Stevenson to carry out the second part of his plan – to face about and attack Weygand with the object of releasing the prisoners – because a company quartermaster-sergeant, Carlyle Smith22 (an enterprising soldier whose nickname was “Beau Geste”), had already

led out from Mezze a party of three armed with sub-machine-guns to accomplish this purpose. They had been in charge of a kitchen truck and had been held up by enemy fire. They crept upon and shot the unwary sentries who were guarding Lieutenant Gall and some of his men outside Weygand, whereupon Gall led five men at Weygand itself, captured it and released Lamb and the remainder of the prisoners. Thus, between 8 o’clock and 10, an extremely tangled situation was unravelled, and the heights overlooking Mezze and the gorge were in Australian hands.

Murdoch, however, with his “platoon” of nine Australians and three Free French, was still at the road-block at the bottom of the gorge. He had placed eight men under Corporal Norcott23 on the left of the road facing towards Beirut, while he and Sergeant Copeman took up a position on the steep slopes overlooking the road on the northern side. Here they held the road for twelve hours against intermittent forays by tanks and armoured cars which attempted to break through both from the east and the west. Some twenty French troops who were supported by two tanks advanced from the large barracks that lay on the Damascus side of the barrier and made a brave attempt to clear the road. In the fight that followed, Copeman, from his position on the side of the gorge and having no better anti-tank weapon, threw three mortar bombs (which did not explode) on to the tanks, and he and Murdoch fired at the tanks’ eye slits at a range of a few yards. The French attackers did not give up, however, until seven of them had been killed. Thenceforward attacks from Damascus ceased, though first an armoured car and later three tanks tried to break through from the western end of the gorge, but again without success. There was now a platoon of Australians in the gorge, a company in Goybet and another in Vanier. About 4 p.m. a company of Indian troops which had been placed under Stevenson’s command arrived with antitank rifles, drove the French tanks away and took up a position 200 feet above the road-block on the northern side of the gorge.

A French report states that the counter-attack towards Mezze on the 19th was made by the 7th Chasseurs d’Afrique, and freed the Damascus-Beirut road. The Chasseurs took 150 prisoners. However the Indian troops continued to infiltrate, and a second mopping-up of Mezze on the 20th was ordered, and an additional 150 prisoners taken. That night the French withdrew to a line from Fort Gouraud on the west through Kafr Suss, Zamalka and Kaboun. Thus they were on this line when the 2/3rd Australian Battalion attacked and cut the Beirut road. The final French counter-attack on Mezze, Forts Weygand and Sarrail was made by Colonel Plantard’s III/24th Colonial Regiment with three companies. It advanced guided by a sergeant of the III/6th Foreign Legion east from Kafr Suss at 12.30 a.m. on the 21st; about 3 a.m. one company (Captain Bousin) was on the southern outskirts of Mezze, another (Captain Harant) in Mezze, and a third (Captain Martinet) in the vicinity. Harant (on whose report, captured later, this account is based) was surprised to find the Mezze gardens full of Indian and Free French troops, some of them sleeping. Confused fighting with rifles and grenades followed. Harant lost six men and tried to move to the right but met hot fire in that direction. “A frightful stench of death fills the lane, and a soft body is under my hand and knee at the foot of the wall,” wrote Harant. “This terrifies me and I decide to

leave anything rather than stay near these bodies, to be killed with these dead without being able to reply. ... We must therefore attack.” Harant tried to urge his men on with shouts, “kicks and punches”, with little success. He then veered to the right and attacked Forts Weygand and Sarrail. At 4.45 a.m. about thirty men entered Weygand, which was unoccupied; but near it they took thirty Australian prisoners and escorted them into the fort. About the same time another group took Sarrail after an exchange of fire in which one Frenchman was wounded, one Australian killed and three wounded. Fifty-nine Australians were captured “including a colonel and a captain”.

When the Indian carriers attacked the French and their prisoners, several were killed including Sergeant Comte who had played a leading part throughout. After the attack there were, in the French force, only seven Europeans and twenty-two natives left unwounded. “From 8 a.m. onwards” British guns bombarded Weygand and at 11 a.m. Goybet also. About midday Goybet was taken and at 1.30 Australians entered Weygand where they captured seventeen Europeans and twenty-two natives.

Although the Australians holding the road-block in the Barada Gorge did not know it at the time, the reason why, after 11 o’clock, no further attempts were made to break through their barrier from the direction of Damascus was that, chiefly as a result of their success, Damascus had fallen.

In the morning of the 21st Colonel Casseau’s force on the Kiswe–Damascus road had resumed its advance through the outskirts of the city. Vichy troops continued to fire from the barracks where they had held up the advance the previous evening, until Colonel Casseau ordered a gun forward to bombard it at a range of 1,000 yards. Farther forward his guns, firing from close behind the leading troops, demolished a concrete pill-box from which a damaging fire was coming. Gordon’s company of Australian machine-gunners were now on the right near Kadem guarding against a possible counter-attack through the plantations beyond the railway, which was to the east of the road; and the Free French infantry were advancing on the left and in the centre.

About 11 o’clock Casseau, believing that all opposition had ceased, sent two armoured cars forward. They had not gone far before there appeared travelling towards them a procession of motor-cars led by one which was flying a white flag. Casseau and Blackburn drove forward and, after a long discussion in French which Blackburn could only pretend to understand, he and Casseau re-entered their cars and drove into the city, the mayor and his officials leading the way. They proceeded to the Town Hall where Casseau and Blackburn (as the senior British officer present) accepted the formal surrender of the city and the police force. There were polite speeches and then a formal luncheon.

About 4 p.m. a more picturesque procession led by General Legentilhomme entered the city in cars escorted by a detachment of Colonel Collet’s Circassian cavalry, and was received by the Syrian Cabinet. On its way this cavalcade was passed by a platoon (Lieutenant Clennett’s24)

of Gordon’s company which had been ordered to find its way through the city and take up a position on the northern side astride the road to Homs.25

That afternoon two companies of the 2/3rd Battalion were on the heights above the Barada Gorge and the third company (McGregor’s with which the fighting troops of the headquarters company had now been combined to make one weak rifle company) was at the road-block on the Beirut road. Brigadier Lloyd’s plan was now to make an immediate advance westwards astride the Beirut road and over the heights whose eastern end the 2/3rd were occupying, but Stevenson asked that his men, who were near the end of their endurance, be given a rest and some hot food, and make the attack next morning. Lloyd, a hard-driving leader whose clear planning and quick decision had quickly won the admiration of the Australians, agreed to this request, and the men had an afternoon and a night of comparative rest, and some hot meals. At 9 o’clock next morning the new attack was launched, Stevenson standing on top of Fort Goybet with a signaller who sent messages to the companies with an improvised flag. On the right a depleted company of Indians, advancing along the heights north of the road, covered that flank while McGregor’s moved along the floor of the gorge until, beyond the railway crossing, it came under machine-gun fire. The men crossed the canal at this point using a swing contrived with rifle slings and, to avoid the enemy snipers posted along the gorge, climbed thence to a protected position on the heights on the northern side.

Parbury, in the centre, moved across the heights, losing some men as a result of hot fire from artillery, mortars and machine-guns both from positions forward of him and on the heights north of the gorge26 – these were also holding up the Indians. At one stage this fire threatened to hold the advance but Private Donoghue,27 a courageous and expert Bren gunner, worked his way forward and shot the crews of three French machine-guns at a range of 500 yards. From the objective on the heights south of Doummar Copeman led a patrol down the slopes towards that village, where he saw some armoured cars and gained the impression that the enemy, despite his intermittent artillery fire, was withdrawing his rearguard west along the Beirut road.

Hutchison on the left of Parbury, with an Indian second-lieutenant and twenty men on his left flank, had advanced sooner than Parbury and, using a covered approach, had advanced about a mile from Fort Vallier and seized two small pinnacles from which the artillery observer was able to direct effective fire against the French positions, while the infantry used their Brens at long range.

Thus the foothold on the heights was enlarged, but the position of the thin line of perhaps 400 men spread across a front of more than two miles was by no means secure. Throughout the day the French guns shelled Mezze repeatedly, setting fire to the ammunition dump there, and later hitting the 2/3rd’s regimental aid post and killing some Indian patients. The shelling of the Kuneitra road was so frequent and so accurate (the French gunners were firing over ground which they knew intimately) that vehicles were compelled to use the roundabout route through Kiswe and, as he was moving from his northern company to his southern companies, Stevenson was wounded in the side by a machine-gun bullet, but carried on. The difficulty of distinguishing friend from foe and the fact that there were not enough troops to thoroughly mop up so wide an area added to the problems of the Allied troops, who included not only Englishmen, Australians and Indians, but Free French of several races and nationalities, wearing a confusing variety of uniforms. On several occasions Australians were (and still are) at a loss to know whether troops seen in their neighbourhood were Indian or Free or Vichy French, and more than once shots were exchanged with troops later believed to be friendly. In the course of the afternoon a skirmish took place on the outskirts of Mezze with two tanks which had been allowed to approach in the belief that they were Free not Vichy French.

It was the loss of the Beirut road rather than the pressure from the south that persuaded Colonel Keime to abandon Damascus. He ordered the establishment of road-blocks at Qatana and Doummar to prevent the advancing force cutting the road behind the French at Merdjayoun. The weary Damascus force of six battalions – V/1st Moroccan, I and III/17th Senegalese, III/24th Colonial and I and III/29th Algerian – withdrew westward through the mountains on the 21st and 22nd and concentrated in the area Souq Wadi Barada, Kafr el Aouamid, Houssaniye, Deir Kanoun – that is, round the Barada Gorge north of the Damascus-Beirut road, which emerges from the gorge about five miles west of Damascus. During this movement the eastern part of the Barada Gorge was held by a force of armoured cars and a company of the 24th Colonial Regiment.

In the afternoon of the 22nd Lloyd and Stevenson surveyed the ground from the elevated Fort Goybet, and Lloyd told the Australian battalion commander that General Evetts’ plan was to occupy a defensive line from Doummar, north of the road, along the Jebel Chaoub el Hass, the towering feature two miles in length and rising more than 600 feet above the level of the Barada River. Stevenson pointed out to Lloyd that his battalion consisted of only three depleted companies, 21 officers and 320 men in all, whereupon Lloyd, to lighten the Australians’ task, decided that only patrols would be established on the Jebel and these would withdraw to the positions the main part of the battalion then held if the Jebel was attacked by the French. Thus, during the 23rd the line remained where it was, though patrols moved forward beyond Doummar.28 In the

afternoon Lloyd informed Stevenson that his battalion was to be transferred to the 16th (British) Brigade, Brigadier Lomax,29 now taking over the defensive line. (Thus the 2/3rd would replace in the 16th Brigade the 2/King’s Own which was still in the Merdjayoun sector.) The brigade had occupied Qatana that day and was advancing northward to the Beirut road. The 2/3rd was to move along the Beirut road – that is to say, across the face of this advance – and join its new brigade about six miles to the west where a branch road travelled south to Yafour. To support him on this advance along a road still, perhaps, held by the enemy, Stevenson was given a battery of field guns, and placed two of them forward to deal with tanks. He asked for a loan of three captured tanks but these were refused; instead he was lent three carriers but was told they were “not to be used in battle”.30 That evening Stevenson learnt that Sabbura had been taken but not Yafour, and realised that his battalion would therefore arrive at the rendezvous before the remainder of the brigade.

The Free French were now deployed covering Damascus on the east and north, while Evetts’ “division” (it consisted of little more than two British battalions, one Australian and the few survivors of the 5th Indian Brigade) faced north-west.31

At 5 a.m. on the 24th the Australian column had moved off in trucks along the Beirut road. The three carriers led, followed by a “tank-hunting” platoon whose only anti-tank weapons were a .5-inch rifle and a Very light pistol which the commander, Lieutenant Murdoch, carried. The Australians knew that the Leicesters were to advance towards the road from Sabbura, and the Queen’s from Yafour and thus both were moving forward at right angles to their own line of advance. As the 2/3rd approached the rendezvous they encountered heavy shell-fire. After having deployed astride the road they came under small arms fire and replied until they discovered that they were exchanging it with the Leicesters.

With the commanding officer of the Leicesters Stevenson agreed that the 2/3rd would help to take eminences which the enemy was holding north of the road, which passes through a defile at this point, and would then move into reserve and remain at the rendezvous to block the road there. The enemy was shelling the road heavily and with accuracy – the heaviest fire that these Australians had encountered in three campaigns. With Parbury’s company leading, the 2/3rd advanced astride the road, widely dispersed and moving fast to lessen the risk of casualties. The platoon on the south side of the road reached the hill which was its

objective with only one casualty, and then was attacked by two French tanks. The Australians north and south of the road set upon these tanks with a strange collection of weapons. Sergeant Hoysted32 hit the tanks with smoke bombs from a 2-inch mortar, firing until they were only 10 yards from him. Murdoch fired at and hit the tanks with Very lights. MacDougal, who lay firing an anti-tank rifle, had his pistol and holster shot off by one of the tank’s machine-guns. Private Donoghue lay behind a rock and fired at close range with his Bren. Evidently bewildered by this fusillade which, though it was incapable of harming the tanks, was extremely spectacular, the tanks retreated. The intense shelling continued, directed, the Australians decided, by observers from Jebel Mazar, which towered some 1,600 feet above the road about four miles to the southwest, and whence the observers could look down on the guns, men and vehicles below as if from an aircraft. The two British guns were put out of action, all but three men of their crews being killed or wounded, but not before they had dispersed a considerable force of French cavalry which was concentrating on the heights ahead of them.

Meanwhile, as an outcome of operations that will be described in the following chapter, the French had at last, on the night of the 23rd–24th, abandoned Merdjayoun. On the 24th, Lavarack agreed to a proposal by Evetts that he should press on to Zahle, secure the Rayak airfield, and cut off the retreat of the forces north of Merdjayoun – a difficult task which entailed mastering the heights dominating the Damascus–Zahle road.

Early in the afternoon Brigadier Lomax ordered Stevenson to withdraw his battalion to Adsaya except for one company which was to remain with the Leicesters; the Leicesters were to form a flying column which was to thrust along the main road as soon as Jebel Mazar was taken. The task of capturing Jebel Mazar, which Lomax believed unoccupied, was allotted to one company (Hutchison’s) of the 2/3rd; the remainder of the battalion was to hold a defensive position. Despite the intensity of the shelling and the long period the battalion had spent under fire the casualties for the day were only ten, a result which the Australians attributed to their dispersion, and their swift movement over any country which offered no cover. Even these casualties, however, were a serious loss to the depleted battalion and Stevenson was compelled again to amalgamate two companies – Hutchison’s and McGregor’s – which together totalled only five officers and eighty-three men. Thus the battalion now had only two rifle companies instead of four and each of these was far below normal strength. That day, however, when General Lavarack had visited the battalion at Adsaya, Stevenson asked him to allow the company of the 2/3rd which was doing garrison duty in the coastal zone to rejoin the battalion, and Lavarack agreed.

In the evening of the trying advance along the Beirut road, and after only such rest as they were able to get during the truck journey through

Qatana, Hutchison’s company debussed at Yafour and set off to scale Jebel Mazar. This spur of Mount Hermon, rising 1,600 feet above the surrounding country, commands a long stretch of the Damascus-Beirut road which skirts its northern edge, and overlooks to the east the relatively flat area round Qatana in which now lay the left flank of the 16th Brigade. As the French were proving, artillery observers on the summit of Mazar could direct fire accurately over most of the area through which the British force was advancing, from guns invisible to the attackers behind the lofty ridge.

Hutchison’s company, with an artillery observer and a line party, left Yafour at 8.30 p.m. on the 24th led by a native guide. In the darkness the weary men climbed westwards. By 9.30 the guide had led the Australians to the top of a hill which, he said, was their objective. Hutchison and the artillery officer examined their map by striking matches and shielding the light with a blanket and decided that they were not on the summit The map was on a scale of four miles to an inch, and thus was not detailed enough to guide troops making a night march up an unfamiliar mountain cut with wadis, but nevertheless Hutchison decided to make a second attempt. When daylight came he found that he was still 600 feet below the summit facing a steep, high bank, and that a number of his men were missing, having become lost in the darkness. He and his sergeant-major, Hoddinott, tried to find a way up the hill but failed, and then for two hours or so the men slept.

About 8 o’clock under a blazing sun the climb was resumed, but soon the leading sections came under fire from machine-guns and a heavy mortar and took cover. At that point, some 500 feet below the summit, the handful of Australians – now only thirty-five strong – built sangars for protection and waited for darkness. The heat was intense (though the snow could be seen on distant Hermon) and one of Hutchison’s platoon commanders was overcome by it and collapsed. The men were short of water, which they drew from a creek nearly two-hours’ journey away, and extremely weary after a day and a night with little rest or sleep.

Brigadier Lomax learnt nothing of the fate of the attackers until nearly 5 p.m. on the 25th, when it was reported that they were unable to reach the objective because of fatigue and lack of water. Later Stevenson asked for permission to relieve them with a new company – Captain Murchison’s, which was fresh, having just arrived from Sidon. It was 110 strong – equal to the other two rifle companies of the battalion put together – and was thus a notable reinforcement. Lomax agreed to the proposal that it should renew the attack and Stevenson ordered Murchison to replace the weary company already on the upper slopes of the Jebel and advance to the summit in its stead.

Guided by the same Syrian who had misled Hutchison, the new company set out in the darkness, were led too far to the left and finally were told by the guide that he did not know where he was. By 5.30 in the morning (the 26th) they had reached the eastern edge of the ridge that runs southwards from the summit and where they expected to find

the company they were relieving, but there was no sign of it there. Nevertheless Murchison decided to continue the climb to the summit, which, he had been told, was being used only as an observation post and would not be strongly held. The company set off in single file but, about 9 a.m., while still well below the top, the head of the column was halted by mortar and machine-gun fire from French troops who were among the rocks close ahead of them. The leading platoon, in which several men had been killed, withdrew. Its commander, Lieutenant Maitland,33 fell and sprained his ankle and, with Corporal Spence34 and several others who were covering the withdrawal, was taken prisoner.35

Soon after this set-back Murchison found Hutchison’s company on the far side of the ridge up which he was advancing and, after discussing the situation, they decided that both companies would assemble there, and when it was dark Murchison’s company, reinforced by a platoon of Hutchison’s – actually the remnants of “B” Company under Lieutenant Brown36 – would again attack towards the summit.

While the two company commanders were thus planning a third attack on Jebel Mazar, Lomax ordered the withdrawal of all three of his battalions to defensive positions – the Leicesters to the Beirut road, the Queen’s to a ridge east of Yafour and the 2/3rd to Col de Yafour, in reserve, but Stevenson persuaded him to allow another attempt to take Jebel Mazar. At 7 p.m., as Murchison’s company was preparing to advance over the ridge to join Hutchison, a sentry gave warning that the French were attacking. Their approach had been made stealthily and in a few moments fire was being exchanged at short range and grenades were being thrown. Murchison divided the company into two parts, led one at the enemy himself while his second-in-command, Lieutenant Dennis Williams, led the other. The Australians advanced, firing as they went, and forced the French in the direction of Hutchison, whose Bren gunners caught them unawares at a range of 30 yards. The survivors clambered back the way they had come leaving behind more than 20 dead and wounded and 12 prisoners out of a company of perhaps 100 men.

Murchison then led his company to Hutchison’s position and, at 1 a.m. – it was now the 27th June and the first attack had begun on the evening of the 24th – the men began to climb in single file – the only possible formation on such a slope – towards a ridge on the left of Hutchison’s position, which had been chosen as the “start-line” of their night attack. They left behind their packs and each man carried only his weapons, haversack, water-bottle and 150 rounds of ammunition. Because, when the sun rose, it would be very hot they wore only shorts and shirts and their steel helmets. As they were approaching this line Murchison who

was leading suddenly shouted “There they are!” The Australians advancing stealthily up the hill in the darkness were close below a French outpost, several of whose sentries they could see silhouetted against the sky on the two steep-sided knolls above them. The wind which was now whistling strongly had covered the sound of their approach, and Murchison could see the sentries peering forward. Immediately Murchison shouted orders to one of his leading platoons to charge the right hand knoll and the other the left. A fierce mêlée followed in which Brens, rifles and sub-machine-guns were fired, grenades were thrown and bayonets crossed. The French were on the higher ground but the Australians could see them against the sky-line yet could not be clearly seen themselves. One Australian grasped a Frenchman’s rifle and pulled him stumbling down the slope. In five minutes Murchison, seeing that the Frenchmen had been overcome, called a halt. More than thirty prisoners were collected and six of the Frenchmen had been killed, several of them with the bayonet. Two Australians had been wounded.37

Leaving Lieutenant Gidley King38 and fifteen men, though he could ill spare them, to take the prisoners back to Hutchison, Murchison led the remainder of his company on. The right wing of his advance now consisted of Brown’s remnants of “B” Company which Hutchison had allotted to him – perhaps thirty men – his left of a platoon under Lieutenant Hildebrandt,39 and his reserve of seven men of company headquarters under Williams. The ground was very broken and so steep that the men had to sling their rifles over their shoulders so that they could use their hands for climbing. Soon Murchison found that Williams’ party was missing and then that Hildebrandt’s could not be found. He continued the climb with only Brown’s platoon. During a ten-minute halt most of the men fell asleep sprawling on the rocks; it was their second night of marching and fighting. About 400 yards from the summit, the noise of their advance still drowned by the howling of the wind, they saw a French machine-gun post against the sky-line. Again taking advantage of the fact that they could see the shadowy outlines of the Frenchmen while the Frenchmen could not see them, they stealthily climbed the hill until they were higher than the guns and then charged down on them from above. One gun was quickly overrun, but the second opened fire when the attackers were still 30 yards away. Murchison advanced towards it firing his pistol until, from his side, Private Melvaine40 ran forward with his bayonet fixed. As the machine-gunner traversed his gun Melvaine seemed for a moment to be moving forward with tracer bullets flashing first on one side of him and then the other, but when, still unharmed, he was within a yard, the gunner – an African – leaped up and ran. Still under fire from more distant

machine-guns they climbed another 400 yards and there the hill began to level out, and the attackers knew they had reached the crest. There were no casualties during this final stage because the attackers could see the direction of the tracer bullets in the darkness and there were large boulders for cover.

The wind which had been fierce before was now a howling gale. Seeing that the French posts on his objective were only 100 yards ahead Murchison shouted to the thirty or so men who were with him to fix bayonets and charge. The men numbed with fatigue began to stumble forward into the French fire. Murchison cried out to them to yell as they had been taught to do and, with shouts and curses, they began to run forward; as they approached, the startled Frenchmen and Africans took panic and ran.

On the summit Murchison pulled out his Very pistol and fired a light into the sky as a signal of success to the men below. Surprised by this brilliant light some of the fleeing Frenchmen stopped and put up their hands in surrender. Five French dead were found and twenty prisoners were taken. Murchison considered that about 100 more escaped down the slope, and that in its three fights his company had driven a depleted French battalion off Jebel Mazar. It was then 4.30 and dawn was breaking.

The Australians found that. Jebel Mazar was capped by two small knolls 200 yards apart. Murchison posted some of his men on one of them and some on the other, and they took up positions in the sangars and shallow connecting trenches the French had abandoned. He was inspecting the area in the half-light when he saw what he thought was a crumpled groundsheet lying on the hillside with a helmet beside it. But the helmet rose and below it appeared the head of a French officer who was sheltering in a small trench. Murchison thrust his pistol towards him.

“Ha!” said the Frenchman. “There are no Germans here.”

“What of it?” said Murchison.

“Then why are you fighting?” asked the Frenchman.

“Because I’ve been told to,” replied Murchison, adding after a little hesitation, “because you are collaborating with the Huns.” And in this style there was a brisk argument on the rights and wrongs of the campaign. The French officer was the artillery observer who had been directing fire on the British positions below.

As the light increased the Australians were able to appreciate the value of the position they had taken. On the plain below them to the west they could see three French batteries, six tanks, troops moving about and many vehicles. But possession of Jebel Mazar was of small value without an artillery observer to direct the fire of the British guns on these targets, and the observing officer who was to have joined Murchison had not done so. At 7 o’clock this officer arrived. The targets were pointed out to him, but he told Murchison that he had left his wireless set 1,000 yards down the hill at the foot of the final steep slope. Murchison told him to go and

get it and he set off down the hill leaving his pistol and an excellent oil compass behind him; but the Australians did not see him again.41

During the morning the parties who had lost touch in the night attack began to arrive. First Hildebrandt’s platoon reached the summit. Later Williams and King appeared leading a larger party than they had set out with. Advancing in darkness over an unknown and rugged mountain and lacking even a compass Williams and his small party had lost touch. On the way they had encountered a strongly-sited French sangar from which two machine-guns opened fire. They returned to Hutchison’s company where they collected some more men and led them forward carrying food and water. Next came an unexpected reinforcement – a Sergeant Mountjoy of the Queen’s with seventeen men. Mountjoy, an imperturbable soldier, announced that he had been sent out to clear the ridge that runs north from the summit of Jebel Mazar, a ridge which the Australians, from their point of vantage, now estimated was occupied by perhaps a battalion of French troops and from which a brisk fire was being directed. Murchison told Mountjoy that he could try to capture the ridge if he liked but, if he stayed where he was, he would have a French battalion to the right, one to the left, and six tanks and much artillery forward of him. Mountjoy decided to remain with the Australians.

As soon as the light was clear enough, and before the whole company had arrived on the summit, the French opened a galling fire from positions 1,000 yards to the right and 1,000 yards to the left and, with medium machine-guns and field guns, from the front. During the first prolonged bombardment the French artillery observer who had been captured succeeded in escaping down the hill dodging for cover among the rocks, carrying with him full knowledge of the weakness of the force on the summit At 7 a.m. the French began advancing up the hill from the Australian right. From then until midday five determined attacks were made by groups of French troops thirty to fifty strong, climbing up the hill using the boulders as cover, but they were not coordinated nor was there effective supporting fire by the artillery. After the first attack the Australians, already anxious lest they should exhaust their ammunition, waited until the attackers were 10 to 20 yards away and then destroyed the attack with a sharp, accurate burst of fire. In one of these attacks Private Atkinson,42 whose comrade had just been shot through the head beside him, jumped out of his sangar with a bag of grenades and disdaining cover made a single-handed counter-attack on the French and drove them off. Early in the afternoon, however, a considerable number of Frenchmen were holding on among the rocks only 200 to 300 yards

from the summit and snipers had worked their way into positions from which they could fire across the reverse slope of the hill.

About 2 p.m. a man carrying a white flag appeared on the southern end of the ridge and was conducted to Murchison by Hildebrandt. The envoy was one of the Australians who had been captured with Maitland and he carried a note addressed to Murchison by name and announcing that he was surrounded and if he did not surrender by 5 o’clock, he would be blasted off the hill by artillery and heavy mortars. Murchison scornfully sent the envoy back with a verbal reply: “If you want to get us off come and do it.”

Murchison, though a leader of uncommon courage and coolness, was nevertheless impressed by the apparent hopelessness of his situation. He had no artillery observer and could reply to his attackers only with small arms fire from a dwindling supply of ammunition. His ammunition would have been exhausted already had it not been that his men had used three Hotchkiss machine-guns which the French had abandoned, and French rifles and grenades. His only signal gear – a heliograph – had been lost during the night. His men had little food and water. A French regiment was steadily encircling him; to the extent that they were firing across the eastern face of the hill, they had already done so. He had watched an attack on Hutchison’s company and seen them driven off the hill far below – too far away for him to be of any help. However, he was not yet completely cut off for during the day runners had carried a few messages up to him and he had sent messages back. One of these increased his problem; it was a message from the brigadier saying “Congratulations. Hold on at all cost.”

Soon after 5 p.m. the French tried to carry out their threat to blast the Australians off the summit, but their artillery fire was ineffective, either striking the cliff-like face of the hill below them or over-shooting the ridge and falling far behind. The mortars, on the other hand, lobbed their bombs accurately, soon began to cause casualties and drove the left platoon out of its position. This bombardment was followed by a half-hearted attack by infantry which was dispersed. Murchison could now see that the Queen’s, to the east, were withdrawing, and that Hutchison’s company, having been driven from its position by a strong French attack across the lower slopes of the Jebel, was no longer in sight. Murchison pondered deeply as to what he should do. He knew his battalion had no reserves with which to counter-attack. He knew also that the French had at least two battalions with ample artillery and mortars, whereas his men had very little water left and an average of only twelve rounds of rifle ammunition a man. On the other hand if he withdrew just as his battalion was preparing to attack that attack must fail; his presence on the summit would give such an enterprise its only hope of success. At length he decided that he would hold on until dark and, if he received no message by that time, and saw no indication that an attack was in progress, he would withdraw. He would climb down the steepest part of the hill, because that would

be least likely to be held by the French, and he would count on the noise of the night wind to conceal the sound of his departure.

There were four wounded men, two of whom could not walk.43 After darkness had fallen and no message had reached them the company began to assemble for the withdrawal. All were stealthily brought in except Hildebrandt and Corporal Wilson44 and his section who could not be found despite much searching.45 It had become bitterly cold for men wearing only shirts and shorts when, at 10.30, the survivors, assuming that Hildebrandt and Wilson had withdrawn by another route, set off in single file down the eastern slopes of Jebel Mazar, Williams and Mountjoy leading the way and Murchison bringing up the rear. Two of the wounded men were carried down the steep slopes by men who held them at the knees and armpits. The other wounded men, whose legs were sound, walked. At the last moment firing was heard near by and Private Everett,46 anxious lest it meant that some of his mates had been left behind, went back to investigate. When he rejoined the company he had a wounded arm but had seen no sign of Australians on the summit. Mountjoy guided the company to his battalion’s former position but there was nothing there but some abandoned packs. They marched wearily on to Yafour where they found nobody, and took refuge in two large caves and slept. At daylight – on the 28th – they found a truck belonging to the Queen’s and with it drove back a mile or so and picked up one of the wounded who had been left there exhausted. The truck carried out the wounded, while the fit men slept that day and night and marched out at dawn next day, eventually rejoining their battalion.47

In the meantime Hutchison’s company had been strongly attacked during the afternoon (as Murchison had seen) but, under the cover of a party skilfully led by Sergeant-Major Hoddinott, he had extricated the company and withdrawn it about 800 yards towards the east. About 4 o’clock Stevenson arrived with a party carrying 16,000 rounds of ammunition hoping to send it to Murchison. When he saw that this could not be sent forward across a plain swept by intense and accurate artillery fire he ordered Hutchison to hold fast until 9 p.m. to cover the withdrawal of the Queen’s and the artillery and then to retire to Yafour. At the headquarters of the Queen’s he asked the commanding officer, Lieut-Colonel Oxley-Boyle,48 to lend him a company with which to try to hold on, but Oxley-Boyle pointed out that he had already lent a platoon, and Lomax was ordering him to withdraw to a defensive position. Both Stevenson and

Hutchison believed that Murchison’s company had been overwhelmed and, even if they had considered there was a chance of saving it, the only force available to make the counter-attack was Parbury’s depleted company, little stronger than a platoon, which could not have advanced to the foothills of the Jebel until darkness because of the well-directed artillery fire on the flat country west of Yafour. In the night Hutchison withdrew. Stevenson had ordered trucks to remain at Yafour until 3.30 a.m. because of the possibility, which he considered remote, of the missing company reappearing, but they had gone a few minutes before the survivors from Jebel Mazar arrived.

It had been a disappointing experience for the Australians who were convinced that if they had had an artillery observer in communication with the guns below them they could have not only held the summit but driven the French from the slopes beyond. The report of this action by the 16th British Brigade says: “Unfortunately essential parts of the O.P. wireless set had been lost on the way up and the O.P. was unable to make contact with the battery. Had this support been available there is little doubt that the objective would have been held.”49

On Evetts’ orders the 16th British Brigade had withdrawn out of the Sahl es Sahra, which was commanded by French guns, to a line from Deir Kanoun to Yafour; the remnant of the 5th Indian Brigade was on the Col de Yafour. The attack on Jebel Mazar was not resumed for ten days.

After Murchison’s company had taken Jebel Mazar the French counter-attacked with a company of the 1/17th Senegalese. This failed. At 2 p.m. a company of the V/1st Moroccan and a company of the I/24th Colonial counter-attacked. The war diary of the Southern Syrian Command says that “at the cost of many casualties and enormous efforts demanded by the nature of the ground these units reached a position 50 metres from the point. Night fell, and the situation remained unchanged owing to the exhaustion of both sides. Hardly any further progress was made with the operation for the recapture of Jebel Mazar during the night because of the uncertainty of our units as to the exact situation, the tiredness of our troops, the nature of the ground, and the cold”.

Early in the morning a troop of Moroccan Spahis “although suffering some casualties ... took seven prisoners”. It was not until about 9 a.m. on the 28th that the French, now reinforced, discovered that the main body of the defenders had withdrawn; they reported taking ten more prisoners.

The French reached the conclusion that the force which had taken Jebel Mazar had been a special “storming party”. “It is to be noted,” stated an Intelligence report

on this action, “that British storming parties number on the average about 50 men with well-trained officers and NCOs and plentifully supplied with machine-pistols and grenades. Men have been found with rubber-soled shoes.”

Meanwhile the column advancing from Iraq had reached a deadlock similar to that at Jebel Mazar. On the 13th June Major-General Clark,50 commanding Habforce (the 4th Cavalry Brigade and other units including the 1/Essex from Iraq and 350 men of the Arab Legion from Transjordan), had been ordered to move into Syria, occupy Palmyra, and thence advance and cut the road from Damascus to Homs. At that time Habforce was widely scattered at Mosul, Kirkuk, Baghdad and elsewhere, but its relief by the 10th Indian Division was about to begin. By the 17th the main body was concentrated at pumping station H3, some 140 miles south-east of Palmyra, while one regiment assembled at T1 on the branch pipe-line to Tripoli to mislead the enemy into believing that an advance would be made up the Euphrates. On the 18th Generals Wavell and Auchinleck agreed on a plan whereby two additional brigades, drawn from the 10th Indian Division, should advance into Syria from Iraq.

Habforce began its advance on the 21st with the object of capturing Palmyra that day. The main body of the 4th Cavalry Brigade (Brigadier Kingstone)51 advancing from H3 included the Wiltshire Yeomanry and Warwickshire Yeomanry, each lacking one squadron.52 South of the ruined city lies a great salt pan reported to be impassable by vehicles. High rocky ridges dominate it on the south-west, north and north-west where lies an ancient fortress called the “chateau”. The garrison was known to consist of two companies of the Foreign Legion and a Light Desert Company. The plan was that the Wiltshire should seize the hills west of Palmyra and the chateau, while the Warwickshire moved east of it by way of T3 on the Iraq-Haifa pipe-line and attacked and entered from the

north. The column of cars and trucks crossed the Syrian frontier at dawn. About 25 miles from Palmyra French bombers attacked, and some vehicles of the Warwickshire were hit, but by 1 p.m. the leading squadron was approaching the south-western edge of Palmyra, where machine-gun fire from the plantations checked it. The remainder of Kingstone’s force advancing from Juffa, found T3 strongly held and was halted under repeated air attack. During the day Clark with the 1/Essex and the remaining artillery of the force from H3 and the Household Cavalry (Major Gooch53) from Ti arrived in the area. At T2, held by a detachment of the Foreign Legion, one of Gooch’s squadrons was left to watch the station (whose garrison surrendered that afternoon) while the others advanced under attack by aircraft.

Next day Clark signalled to Jerusalem an urgent request for protection against the persistent attacks by French aircraft; nine Gladiators arrived at H3 later in the day but because there were no facilities for defence of a forward landing ground were withdrawn. The air attacks became heavier on the 23rd and 24th and so many vehicles were hit that supplies ran short.

A force led by Fawzi el Kawakji, the Arab nationalist leader, and reinforced by French armoured cars lay in wait for supply columns near T3, where one troop of the Warwickshire now watched the garrison. Here on the 24th six armoured cars approached the British troop and, when the yeomanry (who claimed that one vehicle was flying a white flag) emerged from their shelters, the cars opened fire and killed or captured twenty-two men. Later in the day a British convoy was waylaid and captured here. In this fight or the earlier one Fawzi el Kawakji was wounded. Brigadier Kingstone collapsed on the 24th his place being taken by Major Gooch.54

The attacking force continued doggedly to press forward round Palmyra. On the 28th they were greatly heartened by the spectacle of a bombing attack on the enemy and six French bombers being shot down by the escort of nine Tomahawks of No. 3 Squadron R.A.A.F. The 1/Essex captured the chateau that day, but the defenders of Palmyra itself still resisted strongly. Meanwhile the 10th Indian Division in Iraq, commanded by General Slim,55 a rugged leader who had commanded a brigade of the 5th Indian Division in Abyssinia, was preparing an advance by two brigades along the Euphrates to Aleppo.

The day after the fall of Damascus, an event occurred which transformed the situation in every theatre of war. On the morning of the 22nd June German armies advanced into Russia. For a time the threat of substantial German intervention in Asia Minor would be remote.

On the 24th Wavell had sent a summary of the Syrian situation to Dill. He said that the plan then was that Habforce should take or by-pass Palmyra and advance to Homs; the Free French secure the Nebek-Homs road. The 16th British Brigade was to take Rayak, the Australians to clear up the situation at Merdjayoun and advance on Beirut. He reported that another brigade of the 6th Division – the 23rd – was on its way to Syria from Egypt.