Chapter 23: Hard Fighting At Jezzine

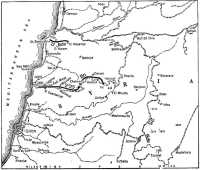

IN the long fortnight between the launching of the French counter-attack and the relief of the Australians at Merdjayoun the struggle for the heights commanding the road leading north from Jezzine had gone on. The French attacks on the 17th and 18th June had ended in a stalemate. On the Australian side two depleted and weary companies of the 2/31st were forward astride the French line of advance. One, only sixty-five strong, was on Hill 1377 holding a front of 1,500 yards, and one across the main road to Beit ed Dine and the ravine through which it ran. On the left the Cheshire Yeomanry were protecting Jezzine against a possible enemy advance through the mountains by way of Machmouche. The French, with two companies of the II/6th Foreign Legion, one battalion of Senegalese (the II/ 17th) and some African cavalry, held forward posts within rifle shot of the Australian positions, which they shelled and mortared intermittently, and their patrols moved both by day and by night in the rugged area between the Australian positions on Hill 1377 and the town. Through this country it took the Australian ration parties and their mules two hours and a half to reach the store at battalion headquarters and six hours to climb back again. One party, with three mules laden with bully beef and biscuits, had a skirmish with a French patrol and two mules were shot before the French were driven off. Despite such forays, however, the enemy showed no signs of renewing the attack, though his guns continued to shell the Australian area heavily.1 Indeed, both the Australians and their adversaries were tired out, and, though still enterprising and aggressive, neither had the strength to do more than hold what they had.

It will be recalled that one effect of the French attacks at Jezzine and Merdjayoun had been a decision to reinforce Brigadier Cox’s one-battalion brigade at Jezzine with the 2/14th Battalion from the coast. Lieut-Colonel Cannon of the 2/14th received orders late on the 17th to move to Jezzine with his battalion and a tail of supporting detachments.2 This little force travelled along the precipitous road from Sidon to Jezzine on the 18th and, as it climbed into the mountains, saw for the first time the lie of the land their division was fighting over – the lofty, steep-sided heights of the Lebanon with its pine forests and terraced farm land, the steep descent to the west and now, far below them, the narrow coastal plain from which they had climbed, and the sea at its edge. After travelling either in trucks or on foot for a night and a day, the 2/14th went into position on the right of the 2/31st, on a line through the Wadi Azibibi. The Victorians had not been fully rested since their fighting on the coast, and the

night-and-day move, a long march on the following night, and the sudden transference to high altitudes left them utterly worn out.

When describing this night the historian of the 2/14th Battalion wrote of “the perpetual fatigue which weighs down the infantryman between battles” (including as infantry those other soldiers who move and fight on foot).

In battle (he declared) weariness slips away, but when the main need is over, dragging fatigue, the protest of the body against will-power, begins again. Mental and nervous reaction coupled with physical overstrain take their toll. In addition, many nights’ sleep are lost altogether while the remainder are broken by sentry-go and patrolling. Even ... the engineers ... who frequently plod with the infantry ... cannot fully comprehend this aching lassitude. It fills the infanteer’s veins with mud and covers his brain with a fog through which he can see only the words “I must keep going”. The airman or the sailor when the battle is over has the one his camp stretcher and the other his bunk (and Heaven knows they deserve them!). The infanteer drops in the mud or among the rocks, to be roused an hour or so later by an NCO saying, “Your turn as sentry”, or an officer saying, “We’ve got to go out on a patrol”.3

The arrival of the 2/14th, however, gave Cox the power to attack again. How should he use it? To thrust through the precipitous country on the left was impossible; to advance along the road, overlooked by the enemy positions on top of the escarpment to the east, would demand tanks and air support; a move through the hills on the west would need pack-animals to carry mortars and machine-guns, and of these he had few. On this flank, however, a 5,000-foot mountain, Kharat, rose above the surrounding ridges and overlooked the escarpment, which in its turn commanded the road. Cox decided to employ part of the new battalion in a flanking attack by night from Kharat across the intervening valley against the French positions on the two main peaks – Hill 1332 and Hill 1284 – on top of the escarpment.

Viewed from the south these hills presented a formidable obstacle. From the 2/31st Battalion’s area round the Azibibi wadi

the mountain rose 1,000 feet in a series of cliffs and rocky shelves. The bridle path that led up the face of this feature was steep and winding to the extent that even the peasants’ donkeys employed to take supplies and ammunition to companies on Wadi Azibibi were rapidly exhausted. The crest of this mountain was covered by a succession of rocky terraces up to six feet high and had a backbone of rock running from Wadi Azibibi north to the blockhouse on the summit. Loose stones and boulders were strewn everywhere although few of them gave effective cover against mortar fire. Only one or two tracks to the blockhouse existed and as can be imagined these were completely ranged by the enemy.4

Two companies of the 2/14th were to assemble on the lower western slopes of Kharat on the night of the 21st–22nd and advance due west across the valley, in which young wheat was growing. The advance was to begin at 4 a.m. and the intention was that, at dawn, the two companies

should attack Hill 1284 and that after that attack had succeeded one company should exploit towards 1332. The 2/31st which had a company astride the road and one on Hill 1377 would feign an attack on 1284 from the south.

The information which General Allen received of Brigadier Cox’s plan late that night made him fear that there was to be no artillery support, and he cancelled it. Later it was learnt at Allen’s headquarters that artillery support had been arranged, and at 10.15 p.m. Cox was informed that the attack might proceed, but it was then too late for the infantry to reach their positions that night and Cox postponed the operation. Later that night he was ordered to report to Allen next morning. He did so and from Allen’s headquarters at 3 p.m. the next day – the 22nd – Cox telephoned to Bertram,5 his brigade major, his final instructions for the attack. The artillery plan provided that the 2/6th Field Regiment would fire for ten minutes on 1284 and then lift to 1332 for twenty minutes, after which fire would again be concentrated on 1284.

That night the two attacking companies of the 2/14th set out through the mountain country for the distant start-line. At 3.50 a.m. the artillery opened fire and carried out its program. When daylight came, and after the night mist cleared, the men of the forward companies of the 2/31st gazed anxiously northwards over the valley towards the two heights the French had held so long. Soon after 5 a.m. their leaders reported to Colonel Porter that they could see no sign of the 2/14th. In fact the march through the fog and the rugged country had been so slow that the attacking companies had not linked at the start-line until long after the artillery fire on 1332 had ceased and the company commanders – Captains Landale6 and Russell7 – decided that it would be fatal to attack. Cox ordered that the attack should be renewed on the following day. In the meantime the cold and weary infantrymen – they still wore only the shirts and shorts that had sufficed on the warm coastal plain – assembled to the south of Hill 1377 to await a second night of marching, with an attack to follow.

Meanwhile Captain Robson, commanding the company of the 2/31st south of 1284, had sent out a fighting patrol of six sections to test the enemy’s strength on that feature and if possible to push him off. The enemy withdrew and the patrol gained the hill to within 100 yards of the blockhouse. The French, however, had craftily withheld their fire until their enemy had declared his intentions and assembled on the summit; now they opened fire from hitherto concealed posts on the front and flanks, and their artillery was brought down on the southern face of 1284 and on Hill 1199, between it and Jezzine. Finally Robson decided to withdraw along the sheltered edge of the escarpment to the south-west. The

withdrawal was gallantly covered by Lance-Corporal Ferguson8 who fought off the enemy with his Bren mounted on a ledge 50 yards from their positions, and Private Murray Groundwater, who ran forward covered by Ferguson’s fire, silenced an enemy post with grenades, and having seized a box of grenades, used them to defend the position against the advancing Frenchmen. Robson was wounded by a mortar bomb that afternoon.

By the end of the 22nd June less than nothing had been achieved, because the French had now been enabled to conclude that the Australians were bent on attacking. On the following night at 1 a.m. the two Victorian companies, on the east, again began marching forward to their start-line; this time the infantry were to give the signal for the artillery to open fire. They reached the start-line at 3.50 a.m., ten minutes before zero hour, and at 4 o’clock Landale fired two red Very lights into the sky to inform the artillery that he was ready – and thus perhaps indicated to the French the general direction from which the attack might be expected. Instantly the guns flickered on the southern horizon, and the infantry began scrambling fast down the lower slopes of Kharat. After they had advanced a few hundred yards, the French, who also had been sending flares into the sky and seemed uncertain of the exact direction of the attack, opened fire and men fell wounded. The leading platoons of. Russell’s company and one platoon of Landale’s went on, but the men behind were held back under increasingly heavy fire from mortars and machine-guns. At dawn, however, the leading men of the forward company were at the foot of 1332, but there were only about forty of them – one platoon and part of another (Lieutenant Whittaker,9 its commander, was killed at this stage). One platoon of Landale’s company was moving up 1284 farther to the left.

Meanwhile Lieutenant Kyffin had led two of the remaining platoons forward. They reached to within 300 yards of a flanking platoon under Sergeant Ralph Thompson,10 who, though wounded, continued to command. Kyffin and others were wounded. These men, exposed to fire from well-sited posts on three sides, fought on until, about an hour after daylight, their ammunition was exhausted. Among them Privates von Bibra11 and Chris Walker12 and a stretcher-bearer of Greek descent, Private Vafiopulous,13 who was critically wounded while attending the fallen men, showed outstanding courage. At last the survivors – eleven in all and most

of them wounded – surrendered to the Senegalese, who were close around them.14

On the left Lieutenant Christopherson’s15 platoon had advanced fast under fire from well-sited machine-guns and mortars and from riflemen behind the rocks on the base of the steep hill. Low on the slopes of 1284 one man was killed and two wounded, one mortally. Where they fell Lance-Corporal Russell McConnell,16 who ran back to help them, set up his Bren on low ground overlooked by French machine-gunners and fired back at them. This action drew the enemy’s fire towards this lonely figure and away from the others who, led by the resolute Christopherson, were clambering quickly up the terraced hill finding cover among the growing wheat. Soon afterwards McConnell was killed carrying a fatally-wounded sergeant, Dossetor,17 to cover.

Christopherson was only three terraces from the summit when, about 6.30, Captain Russell, who had accompanied this platoon, saw that the platoon that was to have followed them was not in sight (Landale had held the third platoon of his company on Kharat where it drove off a French patrol which moved on to Kharat from the north early that morning) and that he and his handful of men were isolated. He ordered Christopherson to move his platoon farther round the left flank of 1284 to lessen the effect of flanking fire from 1332. Later he decided that Christopherson’s platoon could not continue the assault alone and ordered him to move out along a near-by wadi. In batches the men dashed for the cover of this wadi, and there Christopherson found to his dismay that of the twenty-five he had led into action only thirteen remained, and learnt for the first time that his sergeant was missing and others had been killed or wounded following him up the slope. He went back to discover whether he could see any more of his men but only one came in – a wounded corporal, Blair,18 with news that another wounded man, Private Dower,19 lay 50 yards behind. Christopherson took four men back and together they carried Dower to shelter. During the morning the survivors were drawn back southwards in dead ground toward Hill 1377.

Thus the attack across open country against a steep-sided ridge strongly held by a well-prepared enemy force ended in failure.

Meanwhile about 7.15 a.m. a runner had reached Lieut-Colonel Cannon from Russell’s company with news that the attack was failing. Cannon

ordered a platoon under Lieutenant O’Day20 to advance on to 1284 from the south to reinforce the attack. O’Day and his men passed through the left company of the 2/31st, whose forward post was on the lower slopes of the hill, and by 9.30 were climbing them. His instructions were to capture the French position on 1284, the same position which the 2/31st had been unable to hold on the 22nd, though O’Day knew nothing of that. Hill 1284 was in effect a small fortress consisting of machine-gun emplacements surrounded by a 6-foot rock wall enclosing an area 50 yards in diameter, and with a pill-box outside this wall, the whole perched on top of a high, steep hill whose western side was a precipice broken by occasional ledges. There O’Day was to remain, he was told, until the 2/31st reinforced him from the south and he was joined by the attacking companies of his own battalion from the north and west.

It took O’Day’s thirty-two men two hours to climb the rocky slope, which was so steep that until they neared the top they were invisible to the French. Near the summit he sent a Bren gunner, Private Smith,21 and two others to crawl round a narrow ledge leading up the western side of the hill, while he led the remainder on to a ledge 40 feet below the fort. The French were now firing down at them, but they charged forward among the rocks and took the pill-box, which was manned by only two Frenchmen.

The main body of the defenders were now firmly established in their rock-walled fort, with the Australians within a few yards of them on two sides, shooting from behind rocks, some of which were 15 feet high. For an hour the Australians and French (white troops, evidently of the Foreign Legion) fought it out with light machine-guns, rifles and grenades. A party of Frenchmen sallied out moving round a ledge under cover. Corporal Wilson,22 one of three brothers in this platoon,23 crept upon them and with grenades killed six men and drove the few survivors back into the fort. Corporal Lochhead24 and Private Uren25 moved close enough to the wall to kill the crew of a machine-gun with grenades, but not before Uren had been shot by the machine-gunners at a range of a few yards. After about an hour the Australians had almost exhausted their ammunition. One man whom O’Day sent back for more was wounded on the way; at 11.45 he sent back another. At 12 the French opened fire with a heavy mortar which searched the sheltered places behind the rocks, and at the same time some twenty Frenchmen, each carrying haversacks filled with grenades, ventured out on the right and, moving from rock to rock,

began hurling their bombs. The Australians shot six of these men and the remainder withdrew into the fort; but O’Day’s force was being steadily reduced. The well-aimed mortar bombardment against which the rocks gave no protection had wounded four of Corporal Wilson’s men, and the remainder had fallen back to the pill-box; men in other sections had been hit, including Privates Avery,26 who was wounded by a grenade in an affray in which he shot four Frenchmen with his “Tommy gun”, and Deeley,27 who had played an outstanding part in the attack.

Soon after midday O’Day decided that his position was hopeless. One third of his men had been killed or wounded; they had used their last grenade and one of the Brens had been damaged; there was no sign of reinforcements, and another party of enemy grenadiers, about thirty strong, had emerged from the sangar and was moving forward from rock to rock. O’Day first sent one of his sections (Corporal McLennan’s28) to find the small group of the 2/31st on the lower slopes, but they had gone.29 Next he sent out Wilson’s section, now only four unwounded men, carrying the wounded. The seven men who covered the withdrawal maintained an accurate rifle fire on the French grenadiers, and after five of these had been hit and seen to fall the rest sought cover. Thereupon O’Day decided to withdraw while he could. However, 80 yards from the pill-box the little rearguard found three of their men lying wounded, including Corporal Wilson. Thereafter O’Day, Sergeant Mortimore30 and Corporal Lochhead kept the enemy at bay, moving back from ledge to ledge down the terraced hill, while the others toiled ahead of them carrying the wounded. They reached the forward posts of the 2/31st Battalion at 2 p.m.

Meanwhile Private Smith and the two men with him were doggedly clinging to their ledge on the western face of the peak. Smith and Private Le Brun,31 having sent the third man back, held the French off with their Bren until late in the afternoon when, having shot six Frenchmen, they slid down the hillside and clambered back to the 2/3 1st’s position. Of O’Day’s thirty-two men eighteen came out unwounded.32

If the attack westerly from Kharat had surprised the French and if the Victorians had been able to reach the top of the ridge in darkness it might have succeeded. But the French were well prepared for a blow from that quarter, and their Senegalese troops were on familiar ground and care-

fully deployed; that so many survived out of fewer than 100 Victorians who reached the upper slopes facing Kharat was evidence only of the skill of the individual infantrymen in taking advantage of the cover offered by terraced hillsides and rock-strewn crests. General Allen had been anxious lest Cox should plan an attack with inadequate artillery support, yet the company officers who led the assaulting troops were convinced that artillery fire was not effective against good defenders on those steep, rock-strewn peaks; mortars, which could be used at short range and could search behind the rocks and below the terrace walls, were more useful weapons, and it was chiefly the French mortars, which seemed to possess inexhaustible supplies of bombs, that had defeated both recent efforts to hold a position on Hill 1284.

Brigadier Plant arrived at Jezzine on the afternoon of the 24th to replace Brigadier Cox in command of 25th Brigade. Allen was convinced that Cox was too ill to carry on. Cox was reluctant to leave his post, but subsequent medical examination revealed that he should be in hospital, and he was sent to one. Plant, a buoyant and cheerful leader who had seen long and distinguished service as a young infantry officer and brigade major in the previous war, took over a depleted force. The men of both battalions were very weary, though some dogged parties from the 2/14th had strength enough left to spend the night of the 24th and the following day searching the wheat-fields for their dead and wounded.33 The attacking companies of this battalion had lost about forty-eight men including ten killed, the loss falling mainly on Russell’s company and O’Day’s platoon. The men of the 2/31st, now numbering only 545, were also showing signs of extreme fatigue. “This is noticeable today when not noticeable yesterday,” wrote a company commander (Lieutenant Hall34) on the 24th, “several are suffering from slight shell-shock.”35 The French were no less worn out, and, on the 24th, ten deserters from the Foreign Legion surrendered; they complained of the heavy casualties the Australian artillery fire was causing.

The Australians believed that the dejection of the enemy troops and the desertions were the results partly of a ruse. Having heard an unfamiliar voice speaking on the wireless telephone they decided that the enemy was listening in. Thenceforward Porter addressed each of his four company commanders as “adjutant” hoping that the enemy would conclude that he commanded four battalions and not four companies. The success of

this subterfuge was perhaps confirmed afterwards when the French sector commander complained to Brigadier Plant: “What could I do with my three battalions against your four?”

General Allen instructed Brigadier Plant that it would be futile to attempt more attacks on the heights dominating the road and that he should blast the enemy off the rock-strewn summits with artillery fire and take command of the ground on his front by aggressive patrolling. “The country was as bad as Gallipoli and worse,” said Plant later. “The hills were bigger; there were more boulders and, in the Kharat area, no scrub at all.” The ruggedness of the country made it necessary to man more artillery observation posts than normal and these were often separated from the guns by deep valleys. Consequently the gunners were often near the end of their supplies of signal wire, and sometimes had to borrow it from the infantry The 11th Battery at one stage had 35 miles of wire in use; often the distance of observation post to guns was more than 7,000 yards.

On the 26th June Allen informed Plant that he proposed soon to relieve the pressure on the Jezzine brigade by a thrust in an entirely new direction. He would send a small and mobile column from the coastal sector through the mountains by way of Aanout and Rharife towards Beit ed Dine. When the effect of this drive had become apparent, but not until then, Plant was to press on and join the 21st Brigade – at Beit ed Dine it was hoped. For this new thrust through the mountains on the left were chosen the Queenslanders of the 2/25th, who had fought first on the central sector, then on the coast, and now were to undertake an operation in the mountain spine between those sectors.

It will be remembered that on the 18th June General Lavarack had ordered the 21st Brigade not to advance any farther until the position at Merdjayoun had been stabilised. Consequently Brigadier Stevens’ units confined themselves to aggressive patrolling. On the 19th, for example, his cavalry squadron (of the 9th Australian Cavalry) had been ordered to move forward, locate some land mines believed to be in the coast road near Ras Nebi Younes and push on to Sebline. At 8.35 a.m. these newly-arrived cavalrymen were at the Wadi Zeini and had reached a road-block of whose existence they had learnt from a prisoner picked up at Rmaile. Fifty yards beyond the block a French anti-tank gun, 150 yards away in a clump of cactus, fired on the leading Australian tank. The second shot penetrated the engine and later shots jammed the turret. Lieutenant Langlands36 was killed but the driver and wireless operator crouched on the floor unharmed. Trooper Bryne37 who was following Langlands in a carrier put his vehicle under cover and went forward carrying an anti-tank rifle with which he silenced the French gun. He then directed the fire of his squadron’s tanks on to suspected enemy positions. After returning to

squadron headquarters to report what he had done he went forward again to help extricate the damaged tank.

Meanwhile a troop which was forward on the right had been firing on the enemy at 100 yards and less, driving them down into the wadi itself. Sergeant Carstairs38 left his vehicle and, under fire, fetched tow ropes from this troop, returned to the road and with Bryne moved forward in a carrier and towed the damaged tank out. Nine shells had hit it, but the two surviving members of the crew were still unharmed. The cavalrymen directed artillery fire at the Frenchmen in the wadi forcing them to withdraw to the north-east abandoning their gun. The 2/16th Battalion, following the cavalry, attacked and took Jadra village overlooking the Wadi Zeini, where some forty prisoners were collected. That afternoon the 2/27th Battalion moved to the El Ouardaniye-Sebline-Kafr Maya area.

Mills’ veteran squadron of the 6th Australian Cavalry, now equipped with four captured 11-ton French tanks, two British light tanks, and eight carriers, relieved the squadron of the 9th Cavalry on 20th June and patrolled forward on the coast road and inland along the Kafr Maya road. On the following day the 2/27th Battalion patrolled to Kafr Maya and Sebline. Such patrolling was continued for the following few days by the 2/16th astride the coast road on the Jadra ridge, the 2/27th strung out guarding the lateral roads and tracks for a distance of five miles to the south, and the Cheshire Yeomanry farther back astride the lateral roads from Jezzine and Merdjayoun. Thus, throughout this period, two of Stevens’ three units were employed protecting his area against possible thrusts across his lines of communication from the Lebanons.

It was at this stage that General Allen, anxious about the evident presence of substantial French forces in Beit ed Dine and the other mountain towns along the winding roads that led south from it, decided to send the 2/25th into this country. These French forces formed a wedge between Plant’s 25th Brigade north of Jezzine and the 21st Brigade on the coast. The success of this expedition would remove a threat to the 25th Brigade and would reduce the number of troops employed watching the roads leading east and west through the Lebanons between the Jezzine road and the coast.

On the 25th Stevens ordered the 2/27th and 2/16th Battalions to move forward to the El Haram ridge and to send out patrols thence to Er Rezaniye on the right and Es Seyar and Es Saadiyate on the left. At the same time, in accordance with Allen’s plan, he ordered the 2/25th, which had arrived at Sidon from the Merdjayoun sector on the 24th, to clear the enemy from Chehim, Daraya and Aanout, to send patrols thence to El Mtoulle and Hasrout, and occupy Hill 832 overlooking Hasrout if it gave good observation to the north. This would close a lateral road to Beit ed Dine and remove the threat of a counter-attack from that direction. He instructed Lieut-Colonel Withy of the 2/25th to pay special

attention to the southern flank where on two successive days patrols of the 6th Cavalry had seen enemy forces moving.

Late that afternoon the 2/16th, on the coast, with two companies forward, set out for its objective. They had a long march over country cut by several deep wadis and it was 11 p.m. before the left company reached the El Haram ridge, and 4 a.m. before the right company, which had tougher country to cover, was in position. There was some artillery fire but otherwise no opposition. On the right of the 2/16th one company of the 2/27th marched to El Haram itself, where it arrived at 8 p.m. after six hours and a half over very difficult country. It bivouacked near the village that night and, at dawn, began to move in. There was a little firing by a party of French troops but as the men of the 2/27th advanced a patrol of the 2/16th arrived from the western side and between them they captured eight prisoners and a machine-gun. That evening the two leading companies of the 2/16th moved forward to the ridge through Es Saadiyate without opposition. The French guns shelled them at intervals during the night but caused no casualties.

For the expedition to Chehim and Aanout, Brigadier Stevens allotted WI-thy one anti-tank gun and a detachment of engineers of the 2/6th

Field Company. He arranged that after the 2/25th had occupied Chehim an artillery observer would be attached to the force with wireless communication to a troop of the 2/4th Field Regiment, whose guns could fire from positions on the coastal plain at targets in the hills, Chehim being only about five miles from the coast as the crow flies.

After its losses at Merdjayoun the 2/25th Battalion had been reorganised by distributing the men of one of the rifle companies among the other three. From Sebline after dark on the 26th two companies commanded by Captain Marson, an outstandingly cool and trusted leader, marched along the road through Kafr Maya to a point short of Mazboud and thence (by-passing Mazboud where a patrol of the Cheshires had been fired on) over the hills past Mteriate and along a ravine towards Chehim. The mules on which the mortars were loaded could not negotiate the rugged country and were left behind at Mteriate.

At dawn on the 27th the little column reached the road immediately south of Chehim. Lieutenant Macaulay,39 who was leading, had just crossed the road with three men, when a burst of fire came from two armoured cars on the road to the north. When the rest of his platoon tried to cross men were hit. Marson sent another platoon (Lieutenant White’s) under cover along the side of the hill where it reached a position north of the cars and engaged them, but they could not be damaged by bullets.

Macaulay decided that he could break the deadlock and with his three men – two “runners” and one Bren gunner – he moved around the slope overlooking the little town to the northern side, surprising and capturing a French signaller on the way. There, at 7 a.m., he and his men, undetected, piled stones across the road and he sited the Bren gun and his two riflemen on a terrace overlooking this road-block. Soon a French motorcyclist raced out of the town, pulled up at the wall of stones and surrendered. Then two armoured cars appeared on the road coming from the east, each with ten or more troops clinging on to the vehicles. The leading car stopped at the little wall of stones and a French officer sauntered up to it swinging a cane. Macaulay shouted to him to surrender but he ran back to the cars and the men deployed and began climbing the terraces towards Macaulay’s post. The odds were too great; two of Macaulay’s men were captured and he and the third man made off the way they had come, eluding the pursuers.

Meanwhile Marson and his two companies had surprised and knocked out the two armoured cars with sticky bombs and moved to the north-west of the town, whence he called down artillery fire on the town itself, using a telephone line that had been laid from battalion headquarters. As soon as the shells began to fall in the town two French cars drove off to the north-east carrying about twenty-five French troops with them. The townspeople were assembled in the market square where they wailed miserably until ordered back to their homes. By midday a patrol had found the road through Mazboud to be clear and Withy had sent four

carriers through to Chehim. The French retaliated with intermittent artillery fire, but later the 2/25th marched on to Daraya, and through Aanout to Hill 781 before meeting other opposition. There an advance-guard of carriers came under mortar and machine-gun fire from Hasrout, and for the time being the advance petered out. Thus the inland flank was secured and the force on the coast was moved forward to a line from which it could begin reconnoitring for an attack on Damour.

At Jezzine Brigadier Plant carried out the sage policy of pounding Hills 1284 and 1332 with artillery fire. This prolonged bombardment proved successful. On the night of the 28th–29th a patrol of the 2/31st found 1284 abandoned, although when the patrol began to establish itself the French sent over heavy mortar and machine-gun fire from positions farther north in the Wadi Nagrat, and on 1332, and the patrol withdrew. Next day Captain Muir40 (of the brigade staff who had taken over Robson’s company) led a fighting patrol of two sections forward under orders from Porter to make a mock attack and cause the enemy to reveal himself.41 The patrol climbed to the boulder-strewn crest, and there orders were shouted as though for a battalion attack, Very lights were fired, and supporting sections fired heavily over the heads of the advancing men. The French opened fire, but Muir pressed on with fourteen men past 1284, which the French had abandoned, and on to 1332, which the patrol held until nightfall when it was relieved by another company. Hill 1284 bore evidence that persistent artillery fire had made it untenable. The rocky crest was scarred in a close pattern for many yards. Bodies of men spattered the stone emplacements, and shattered remains of arms and equipment were strewn everywhere.

Throughout the 25th Brigade’s area patrolling became more vigorous and ambitious as the troops’ spirits and strength were refreshed. On 28th June, for example, two fighting patrols of the 2/14th under Corporals Osborne42 and Waller43 climbed Kharat before dawn, took two machine-gun posts and captured nine Senegalese (of the II/17th Battalion). The battalion then occupied the reverse side of Kharat and, in the afternoon, a mortar detachment under Lance-Corporal Booth44 engaged machine-gun posts on that mountain. Because the ground was too hard to place aiming posts and no suitable aiming mark could be found Private Douglas45 stood up in the open and, stretching out his arms, was used as an aiming post.

Later that afternoon the same detachment knocked out three machine-gun posts on the forward slopes of the mountain.

On the 29th about twenty-five men under Lieutenant Crook46 of the 2/31st Battalion set out to raid Hill 1066. Crook took his men along the road to the Sagret Fellah whence they climbed up a goat track in single file and, on the open plateau on top, re-formed and attacked in extended order. The little force advanced 400 yards and took about thirteen prisoners before Crook decided to withdraw so as to be clear of the area before daylight.

The same day a patrol of the 2/14th under Lieutenant McGavin47 attacked a blockhouse near Machrhara. After a long climb they moved forward, using the rocks as cover, to a point about 100 yards from the blockhouse and the machine-guns round it. There McGavin put down two of his sections to give covering fire while he and Lance-Corporal Burns48 charged, McGavin shouting in French to come out. They reached the blockhouse unhurt, took ten prisoners there and were just emerging when a machine-gun opened fire from the cover of vines only twenty yards away. McGavin and Burns with their prisoners hurried back into the blockhouse while the rest of the platoon engaged the French machine-gun, whose crew surrendered when they saw that their comrades in the blockhouse were captured. By 6.30 p.m. McGavin was back in his platoon area with fourteen prisoners who said that they were from a Foreign Legion battalion recently at Damascus. The patrol suffered no serious casualty.

The 2/14th now learnt that they were to be relieved on 1st July and to return to their own brigade on the coast. By the 30th the brigade was holding posts from Toumat on the right through Kharat and Hill 1377 to Hill 1332 – a front of 10 miles. Merely to live in the outposts on the 4,000-foot ridges along this line was a hardship, leaving out of account the intermittent bombardments and arduous patrolling.

Meanwhile a lively action had been fought on the right wing beyond Damascus where the Free French had thrust far to the north. On 30th June the force at Nebek consisted of the 2nd Free French Battalion supported by four British field guns and some anti-tank guns. The infantry was deployed astride the road north of Nebek. At 4.55 a.m. the enemy’s guns began firing a heavy creeping barrage and at 5.35 seven tanks attacked from the east. They advanced very slowly but in two hours had reached orchards east of the village. Seven more tanks then appeared advancing down the main road, but were driven back by the artillery. The tanks on the east, now supported by lorry-borne infantry, pushed on to the south-eastern edge of the village, where, however, they came under fire

from anti-tank guns and one field gun; three tanks were destroyed, one captured and the remainder hastened away. Nevertheless the Vichy infantry dismounted and pressed on steadily and were near the village when, about 1 p.m., the Free French counter-attacked and drove them off. The defenders lost 8 men, the Vichy French left 40 dead and 11 prisoners.49

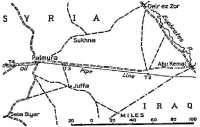

Farther east, Habforce, still under heavy attack by French aircraft, continued its attacks on Palmyra. On the 29th the defenders struck back and drove the Wiltshire Yeomanry from a ridge above the town; next day the 1/Essex counter-attacked and regained part of it, and on the 1st July observed the defenders withdrawing from the outlying gardens to the inner defences.

Firmly held at Palmyra and under frequent attack from the air the British force was being harassed also by French raiding parties based either on Seba Biyar to the south or Sukhna and Deir ez Zor to the north-east. On the 26th General Clark of Habforce gave Major Glubb and his Arab troops a task well suited to their temperament and experience: to take and hold Seba Biyar and Sukhna and thus protect his supply lines. On the 28th Seba Biyar was surrendered to Glubb’s Arabs by a French warrant-officer who declared that he was a keen de Gaullist. Next day Sukhna was found to be empty of French troops; a squadron of the Household Cavalry was sent there to reinforce the Arabs. The origin of the raiding parties was revealed on 1st July when a column of French vehicles unexpectedly approached along the Deir ez Zor road. The French deployed and attacked but were routed by an impetuous attack by Glubb’s Arabs; eleven of the enemy were killed and eighty men and six armoured cars captured. It was found that this force comprised one of three French light desert companies of which two had now been virtually destroyed at Sukhna or Seba Biyar and one was in Palmyra. “After the action at Sukhna,” wrote Glubb, with pardonable exaggeration, “the Syrian deserts were entirely cleared of enemy troops.”50