Chapter 26: Administering the Armistice

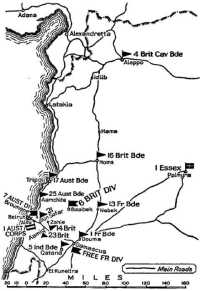

After the capitulation, the territory from the Damascus–Beirut road northwards was placed under the control of I Australian Corps. The 7th Australian Division would occupy the coastal zone and the western slopes of the Lebanon watershed; the Free French Division an area east of the watershed of the Anti-Lebanon and including Damascus and Nebek; the 6th British Division the area between the Lebanons and the Anti-Lebanons, and the desert area surrounding the Free French zone and including Horns, Hama and Palmyra; Habforce, now placed under General Lavarack’s command, was to occupy north-eastern Syria west of the Euphrates. The area beyond the Euphrates in the far north-east was occupied by the 10th Indian Division.

The Syrian armistice agreement – the Acre Convention as it was named – contained two provisions that were later to come into dispute: first that Allied prisoners, including those transferred to France, were to be set free, the British authorities reserving the right to hold as prisoners an equal number of French officers of similar rank until the Allied prisoners had been released; secondly, that the alternatives of joining the Allies or being repatriated were to be left to the free choice of the individual Vichy Frenchman, all who wished being repatriated.

To the convention had been added a confidential protocol in which General Wilson and General de Verdilhac agreed that there should be “no personal contact between French and Allied individuals in order to influence the free choice of French military personnel”; that the Allied authorities might use pamphlets, wireless and loud speakers “for dissemination of their point of view”; but that “the choice of alternatives” should be made without any sort of pressure, and the assistance of British officers might be invoked by the French (meaning Vichy French) authorities if considered necessary.

The supervision of the Acre Convention was entrusted to a commission of control headed by Major-General Chrystall,1 a former commander of the Transjordan Frontier Force. It included Lieut-Colonel Fiennes;2 a representative of General Catroux, and two representatives of General de Verdilhac, with a third British officer as secretary. The commission was to establish its office in the Beirut area. Under it were created a number of committees to supervise various departments of its work; one was to deal with problems concerning prisoners and was presided over by Colonel Blackburn, a South Australian lawyer in civil life, whom we last met leading the advance into Damascus.

Dispositions, 31st July

The situation in Syria after the armistice was peculiar and delicate. Five distinct groups were involved – British, Vichy, Free French, Syrian, and Australian – each with its own aims and ambitions. The most powerful group was headed by Mr Oliver Lyttleton3 (who had recently been appointed Minister of State in the Middle East) and General Auchinleck, and represented British political and military strength in the Middle East. It had entered into a confidential agreement with the Vichy army, its recent enemy, to protect that army against the probable efforts of the Free French, its allies, to use pressure to persuade Vichyites to join General de Gaulle. The British objective was to remove General Dentz’s army from Syria rapidly and without disturbance.

General de Gaulle and General Catroux, on the other hand, were chiefly interested in establishing their prestige and authority in Syria, and, as a means to that end, in persuading as many Vichyites as they could to join them. They hoped thus to form two full divisions, equipped with French arms, in place of their half-division lacking in artillery and other technical equipment.

The third group – the Vichyite leaders and practically all their men – detested the de Gaullists and wished to return to the relative peace and security of France.

The army occupying most of Syria (the fourth group) was principally Australian and led by an Australian general. In common with the British, the Australian leaders were anxious to see the terms of the convention carried out smoothly, but they were uninterested in a variety of political considerations that the British leaders could not ignore. They had a warm fellow feeling for the Vichyites – at the armistice General Lavarack had ordered that “all possible courtesy and consideration” be shown to a defeated enemy who had “put up a very gallant defence”.4 They felt

a little coolness towards the Free French, whom they considered had misled them before the campaign and played an undistinguished part during it.

The fifth group comprised the Syrian peoples. They had welcomed the British troops with some enthusiasm but impressed the Australians as being doubtful whether the change of government would hasten the time when they would gain independence of European rule.

It was inevitable that in such circumstances political problems should soon arise. On 21st July General Wilson informed his subordinate commanders that General Catroux had asked for a wider distribution of Free French troops so as to place his units not only in Damascus but in Beirut, Tripoli, Aleppo and Horns. Wilson added that, although he had agreed to allow two French battalions to go to Beirut, he would permit no other changes until the repatriation of the Vichyites had been completed “because of the danger of clashes between the two”. Nevertheless other Free French units were in fact moved; and on 30th July Lavarack ordered the commander of the Free French Division not to act on orders from anyone else without Lavarack’s sanction. Two days later, when Wilson called for fuller information about the general situation, Lavarack replied:

Situation satisfactory. Large numbers French would join British but marked hostility to Free French. Security situation deteriorating owing growing hostility to French taking control. This reduces security for which we invaded Syria. French equipment particularly anti-tank and anti-aircraft and tanks available replace and fulfil deficiencies in troops under my command reserved for Free French future needs. Such material could be used for training now and if necessary returned Free French when fighting troops otherwise equipped. Wide scattering Free French troops for political reasons is tactically and administratively unsound in area seized for our own protection. In general Vichy apparently carry out terms of convention though most officers appear admire Nazi whilst faithful Main. Direct Free French political interference occurring and has caused military move to Soueida of Free French troops under my command without my knowledge. Under orders General Catroux Sûreté arrested Captain Bordes while acting correctly on parole under Australian arrest. Release secured but Colonel Barter5 says Free French intend re-arrest in spite full explanation situation.

On 3rd August Lavarack reported that “despite two telegrams and personal interview with Corps Commander, Legentilhomme still fails acknowledge receipt written order”, and that the Free French alleged that, operations having ceased, their civil administration was paramount. On the same day he wrote to General Blamey that the Free French were acting on orders from Catroux on “the openly-admitted grounds of showing that the Free French and not the British control Syria”. He added that the relations of his force with the Vichy French were “correct but cordial”, the Vichy French having more than carried out their side of the convention, but there had been breaches of the convention by the Free French. He considered that cooperation between the two French groups was practically impossible, that they were trying to delay the repatriation

of the Vichyites, were no less unpopular with the Syrians than the Vichyites, and their assumption of control was leading to a deterioration in the local security problem.

I would be most pleased (he concluded) if you could find time to come here quickly so as to see for yourself. ... In Australia the political repercussions .. . might be serious if our troops are denied equipment which they need and which they helped to capture and if military security ... is destroyed ... for political motives between Great Britain and Free France.

In short the Australian commander wanted two assurances: first that the Free French should stay put and not complicate a touchy police task, and second that his corps should be able to replenish its equipment from the stores it had captured, the better to carry on with the fight against Germany. General Lavarack quoted a report by Colonel Blackburn in which Blackburn pointed out that, in spite of the protocol to the Acre Convention, Free Frenchmen were about to try personally to persuade Vichyites to join de Gaulle, that there was to be no free choice among civilians, that officers’ personal arms were to be confiscated and certain senior officers were not to be repatriated until the very end. Blackburn said that the Vichyites trusted the Australians and, if the convention was broken, the Australians concerned would be branded with dishonour in the eyes of the Vichy army. He therefore suggested that Australians be no longer employed supervising the choice of Vichy French whether to join de Gaulle or not.

De Gaulle had objected to the terms of the armistice on the grounds that they did not provide sufficient opportunity for his subordinates to rally the French to his cause, and did not sufficiently safeguard the political position of Free France in Syria. His protests led to discussions with Mr Oliver Lyttleton at which it was agreed that civil authority in Syria should be in the hands of the Free French, but the French forces would be under the command of General Auchinleck for operational purposes, and in the British military zone the civil authorities would carry out the wishes of the military commander. It was agreed also that the confidential protocol to the Acre Convention be cancelled; that is to say, the Free French were to be allowed to enter Vichyite camps. Lavarack’s response was to order, on 6th August, that no British or Australian troops under his command should take part in “such entry or propaganda” nor be used to enforce it.

The question of the disposal of Vichy equipment was still unresolved. At a conference on 8th August attended by General Wilson, Major-General Spears,6 General Catroux and others it was underlined that all French war material belonged to the Free French, but that after they had satisfied their immediate needs they should supply the British army with anything it asked for. The Free French were to police the districts in which Vichy troops were concentrated. It was decided that after the Vichyites had been embarked, two British corps would be in position in

northern Syria, one west and one east of the Anti-Lebanon, with the French troops in reserve between Beirut and Damascus, and occupying most of the principal towns – Beirut, Aleppo, Damascus, Horns, Tripoli and Soueida – each with one battalion. When General Catroux asked for information about the British order of battle General Wilson was hesitant “in view of the present unsatisfactory state of affairs as regards security”, but finally agreed that it should be shown to Catroux and one other French general and to them only.

That day General Lavarack obtained an interview with Mr Oliver Lyttleton, who said that he had taken steps to ensure that General de Gaulle modified his intolerant attitude towards British control in Syria and the British forces, and that the supremacy of the British military command had been made quite clear. Lavarack protested against the denouncing of the confidential protocol, and added that Australians felt keenly that their honour was involved. Lyttleton said that there was ample justification for denouncing the whole convention if it was desired. As a result of conversations between Free French officers and British members of the Spears Mission it was agreed, on the 12th, that three days’ notice was to be given of any moves by Free French into the Australian Corps area, which was defined as all Syria north of the Damascus-Beirut road but not including those towns. Meanwhile on the 7th August Mr Lyttleton and General de Gaulle exchanged letters in which Lyttleton gave an assurance that Britain had no interest in Syria and Lebanon except to win the war; but pointed out that both Free France and Britain were pledged to the independence of Syria and Lebanon. De Gaulle noted that Great Britain admitted “as a basic principle the pre-eminent and privileged position of France” in Syria and Lebanon.

Meanwhile the repatriation of French troops proceeded. Eight convoys, three hospital ships and one “gleaner” ship sailed for France between 7th August and 27th September carrying 37,500 people, of whom some 5,000 were civilians and the remainder troops. Of 37,700 Vichy soldiers only 5,668 chose to join the Free French forces.7 General Catroux had anticipated forming a second French division. In fact he did not receive enough volunteers to bring his one division to full strength and, late in August, the “1st Free French Division” ceased to exist and the French army in Syria was divided among three “district commands” with headquarters at Aleppo, Damascus and Beirut.

While these problems were still unsettled a new difficulty arose in the relations between British authority in Cairo and Jerusalem and the Australian commanders on the spot in Syria. Some British, Australian and Indian prisoners of war – thirty-nine officers and thirteen NCOs – had

been sent to France, and eighteen were in Italian hands at Scarpanto in the Dodecanese. The Allied members of the Control Commission demanded of General de Verdilhac that they be returned by 5th August and declared that, if this was not done, fifty senior Vichy officers would be detained.

Consequently General Allen was instructed that Brigadier Savige should arrange for General Dentz to go to General Lavarack’s house, and that two colonels should similarly arrest Generals Arlabosse and Jennequin at the same hour. With these instructions were delivered three pairs of letters, signed by General Chrystall, which were to be handed to the French generals if necessary. The first letter of each pair stated that the time limit for the return of the Allied prisoners had expired and requested each general within one hour to accompany the officer presenting the letter, taking with him an A.D.C., two servants, and “bedding, baggage and sufficient food for twelve hours”; because of failure to return the prisoners, the terms of the armistice could be considered null and void. The second letter (to be used if the general concerned refused to accompany the officer sent to detain him) stated that that officer was to use force to compel him to do so. Allen was instructed that “besides tne officers in charge and an interpreter, three other officers shall accompany each party in case it is necessary to use force on the officer concerned whose rank requires that he shall not be man-handled by other ranks”. Allen was not happy about these proposals, and was convinced that the task could be carried out with no show of force; indeed that a show of force might lead to bloodshed. Allen summoned Savige and Plant (in whose area General Arlabosse lived) and obtained their agreement that armed parties were not necessary. He sought an interview with Lavarack and asked for a free hand as to method, and Lavarack agreed.

Savige then obtained Allen’s permission to substitute an Australian subaltern who spoke French for Lieut-Colonel Fiennes of the Commission of Control who had been sent forward to assist him. (Savige did not speak French and therefore felt himself greatly dependent on his interpreter.) He also chose Lieut-Colonel Stevenson of the 2/ 3rd to deal with General Jennequin. Fiennes, when he arrived, protested strongly that his orders were to accompany Savige at “the ceremony of arresting Dentz”; and, when Savige refused, Fiennes asked to be allowed to telephone his superiors. Savige forbade this and gave Fiennes a written statement that he had decided that Fiennes should instead accompany Stevenson to detain Jennequin.

At 3.45 on the afternoon of the 7th Savige, accompanied by a British officer as interpreter, called upon Dentz, who had been suffering from an attack of fever said to be dengue, and presented the first of the two letters to him. Dentz expressed indignation both at the arrest and at the order that he carry bedding and rations. Savige did his best to blunt the edge of this indignity by explaining that there might be a breakdown on the long night journey to Jerusalem and that, in fact, he had brought a hamper of food for Dentz’s use. Dentz then said that he felt the need of a night’s rest because of his illness and would be available for the

journey at 9 o’clock next morning. Savige countered this proposal by suggesting that his own senior medical officer (Lieut-Colonel Lovell8) examine Dentz in the presence of Dentz’s own medical officer. This was done, and at length Lovell expressed the opinion that Dentz was able to make the journey without risk. Dentz still refused. Savige, determined to do all he could to avoid presenting the second letter, asked the general to reconsider the decision in the light of his rank and dignity. This nonplussed the old French general who rose from his reclining position on the couch and said “Yes, you are right; how long will you allow me to get ready?”

At 9.30 that night Savige and Dentz, who rode in his own car driven by his own driver without an escort sitting with him, arrived at the headquarters of General Lavarack. Lavarack was out, but next morning received Dentz, and “was most charming in his attitude towards [him], which had a most appreciable effect on the general”. It was agreed that Dentz was unfit to travel farther immediately. Next morning, as Savige and Dentz departed, a guard paid compliments to the French general.

General Jennequin was away from Beirut when the officers arrived to detain him Road-blocks were established across the routes along which he might escape but he was eventually found in Tripoli, and at length, though at first he objected, he was escorted to Jerusalem by Colonel Stevenson. General Arlabosse was at Djournieh. Brigadier Plant, who was on very good terms with him, found him understanding, and Plant escorted him to Lavarack’s headquarters. When they arrived at Jerusalem Dentz and his colleagues, thirty-five in all, were placed in quarters guarded by armed sentries.9

The Allied prisoners (including four Australians) had arrived at Toulon on 4th August, having been flown to Athens, taken by sea to Salonika and thence by railway. It was not until 9th August that they were placed aboard a ship travelling to Beirut, where it arrived on the 15th; the prisoners from Scarpanto did not return until the 30th. In September Dentz and his senior officers were allowed to leave for France.

What had been the attitude of the people of Syria and Lebanon towards the invading and the defending armies? Most of them sided actively with neither one nor the other, but patiently waited for the battle to pass by, and adopted a friendly policy to whichever side occupied their town or village – a policy no doubt deeply ingrained in the people of a country which had been for centuries a battleground. Arms, probably abandoned on the battlefield or by fleeing French troops, were found in some homes; during the campaign there was some traffic through both British and French lines; there were reports that civilians were observing for French artillery and cutting British telephone lines, but no evidence of substantial

sabotage; some of the inhabitants were more friendly than others; a few seemed hostile; the gendarmerie were almost always cooperative. General Dentz averred at his trial in 1945 that throughout the campaign there was no rioting, and no telephone line of his was cut nor railway line damaged.