Chapter 28: On the Northern Flank

When the Syrian campaign opened it was only in the Middle East that German and Italian troops were in action; in the Western Desert they had been halted, but in Greece and Crete a victorious German army and air force seemed to be poised for a new thrust eastward into Asia. When the Syrian campaign ended, however, three-quarters of the German Army – nearly 150 divisions – was locked in a struggle with Russia. The Middle East, for nearly a year the centre of the conflict, had moved into the background.

As we have seen, in the second quarter of 1941 Hitler was engrossed with the coming campaign in Russia, and he allotted only token support to the revolt in Iraq, and agreed to the airborne attack on Crete with but moderate enthusiasm. In May and early June, however, it was natural that British leaders should be anxious lest the Germans attack Cyprus and Syria. Indeed, confident that Russia would swiftly be defeated, the German staffs in July issued preliminary instructions for operations that were to follow – a three-pronged thrust through Libya, Turkey and Persia. The British staffs also believed that Russia would rapidly be overcome and the victorious German armies might soon be advancing through the Taurus and the Caucasus towards Suez and the Persian Gulf. By the end of August, however, it seemed that Germany’s success was now to be less swift than in Poland or France. In the north the Russians still held Leningrad; in the centre the German advance towards Moscow had come to a standstill; only in the south, where the German army had isolated Odessa and reached the Dnieper, was it making notable progress. It seemed that Russia would not be overthrown as easily as German and British – and American – leaders had expected. “In general,” said a British Intelligence summary of 24th August, “there is as yet no sign that Russian resistance is anywhere nearing a collapse. ... The further developments in the German plan are now unfolding. The present phase appears to be a desperate drive, before autumn sets in, to reach Rostov and thus isolate the Caucasus. This would deprive Old Russia of some 80 per cent of her oil supply and seriously weaken her ability to carry on a long campaign.”

Meanwhile, during the first half of 1941, Britain’s own strength had greatly developed. Her own and the Dominion factories had vastly increased their output, and Lend-Lease supplies from the United States (which in March President Roosevelt had proclaimed to be “the arsenal of democracy”) were being delivered in mounting volume. It was predicted that American factories would produce 17,000 aircraft during 1941, of which three-quarters would go to Britain. A measure of the growth of the British Army is that it now contained seven armoured

divisions, and Canada and Australia were each forming one. In August Roosevelt and Churchill met in mid-Atlantic, and afterwards announced the Atlantic Charter, which stated the common principles on which the two leaders based “their hopes for a better future for the world”.

In the Middle East an immediate effect of German preparations for the invasion of Russia had been the withdrawal of German aircraft, particularly from Sicilian airfields whence Malta had been sorely blitzed during the early months of the year. Air Marshal Tedder reacted swiftly, and by the end of June had established a considerable air force on the island with the intention of making severe attacks on the German-Italian sea route to Africa.

The new military commander, General Auchinleck, when he arrived in July, took over an army considerably stronger than Wavell’s had been in the critical early months of the year, despite the heavy losses of April and May. That army now included one armoured division and nine infantry divisions (most of which, however, held far less than their quota of vehicles and other equipment). A second armoured division – the 10th – was being formed, and an infantry division – the 50th (Northumbrian), re-formed after its losses in France – was arriving. It would be the first United Kingdom infantry division to reach the Middle East since the outbreak of war. The decisive defeat of the Italians in Abyssinia, where only one strong centre of resistance remained, enabled strong forces to be switched to the Western Desert. In May, June and July the 1st South African and 4th and 5th Indian Divisions were transferred north (as we have seen, a brigade of the 4th fought in Syria), leaving the two small African divisions, chiefly of native infantry, to complete the conquest of Abyssinia.

Some of the burden of responsibility that Wavell had carried was removed from Auchinleck’s shoulders by the arrival of Mr Oliver Lyttleton as Minister of State to coordinate British activities, political, military and economic, in the Middle East. Lyttleton presided over a Middle East War Council, mainly concerned with political problems, and a Middle East Defence Committee, on which the three Commanders-in-Chief sat to deal with major military questions.

After the Syrian campaign Auchinleck considered that he must reckon with the possibility of a German attack through Turkey or the Caucasus in September or October. On 18th June the control of operations in Iraq had been returned to the Commander-in-Chief in India (who for the following fortnight had been Auchinleck himself) and consequently Auchinleck’s present responsibility in this area was limited to the western part of the Turkish frontier1 – thus in yet another respect his task was lighter than Wavell’s.

While Auchinleck was attempting to build up his force in Syria new demands arrived from farther east. The British and Russian Governments

were disturbed at the presence of active groups of Germans and Italians in Persia whose ruler, Riza Shah, in his efforts to free his country of the influence of Russia and Britain, had encouraged German and Italian firms and technicians, and at the same time had drawn closer to Turkey, Iraq and Afghanistan, whose rulers shared his desire to avoid European entanglements. In Persia were oilfields and refineries on which Britain greatly depended, and the road and railway from the Persian Gulf was the only route along which Russia might receive Allied supplies from the south. When the British and Russian Governments sought the expulsion of German and Italian citizens from Persia, Riza Shah refused to reverse his settled policy at the demand of traditional enemies. Finally, on 24th July, General Wavell was informed that the British Government had approved “the application of Anglo-Soviet diplomatic pressure backed by a show of force on the Iranian Government in order to secure the expulsion of Axis nationals from their country; should diplomatic pressure fail force was to be used”.2 General Wavell instructed General Quinan to concentrate forces on the frontier ready to advance in the second week of August.

Since the opening of the invasion of Russia Quinan’s main task, like Wilson’s in Syria and Palestine, had been to prepare against a possible German advance from the north; he had been instructed to develop facilities in Iraq for a force of up to ten divisions and thirty air squadrons, and to have forces ready to safeguard the oilfields.

For the present, however, in southern Iraq Quinan had little more than one division, the 8th Indian, one of whose brigades did not arrive from home until the 10th August. Next day the 9th Armoured Brigade (formerly the 4th Cavalry Brigade of Habforce – despite its new title it had no armour) arrived at Kirkuk and Khanaqin where the 2nd Indian Armoured Brigade (with little armour) was already assembled. The 10th Indian Division (Major-General Slim) in north-eastern Syria was also transferred to Quinan’s command. Riza Shah on the other hand possessed an army of about ten small divisions varying in strength from 5,000 to 7,000, with some 524 guns and 280 aircraft. About half the army was believed to be facing the Iraq and half the Russian frontier.

An Anglo-Soviet ultimatum was presented to Riza Shah on 13th August; the reply was considered unsatisfactory and, after some delays, orders were given for a combined advance into Persia on the 25th August. That day, in the early hours, a brigade of the 8th Indian Division landed at Abadan, from naval craft, found most of the Persian troops asleep, and by 5 p.m. had captured the refinery; next day the whole island was occupied. On the 25th a naval force, including the cruiser Enterprise, aircraft carrier Hermes and the oiler Pearleaf, escorting two companies of the 3/10th Baluch Regiment on board the Australian armed merchantman Kanimbla, occupied Bandar Shapur, port and terminus of the railway from Tehran to the Persian Gulf. Soon the oilfields had been occupied

and Slim was advancing on Kermanshah. On the 28th the Persian army surrendered. In the four-days’ operation, the Indian-British force lost twenty-two killed (including sixteen Indians) and forty-two wounded.

Quinan decided to occupy the line Hamadan-Kermanshah-Shahabad, and to post a force at Ahwaz, thus guarding both oilfield areas, and to withdraw all troops not required for this task into Iraq; because of his shortage of vehicles he was unable to maintain troops forward of Hamadan.3

In spite of the danger of a German march through Turkey it had been decided that as soon as Syria had been occupied the main effort in the Middle East should be concentrated on driving the enemy from North Africa, and that the northern flank must be occupied by a minimum force. At the same time the advance into Syria was considered to have given added importance to Cyprus, garrisoned since 5th May largely by the 7th Australian Divisional Cavalry Regiment.4 It will be recalled that because of their losses on Crete the German leaders decided that they would not attempt an airborne invasion of Cyprus, but suggested to the Italians a seaborne attack by night from the Dodecanese. Nothing came of this

suggestion. The German leaders believed in June that the island’s garrison would soon be reinforced. In fact, in July Auchinleck decided to send to Cyprus the 50th Division, then arriving from England, and to replace the 7th Australian Cavalry with an Hussar regiment. This movement was completed on the 29th August.

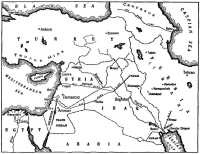

By mastering Syria and Iraq Britain had advanced the ground on which she might have to defend the Canal and the Middle East oilfields by 300 to 500 miles. On the eastern flank the German attack might come, by exploitation of a victory in Russia, through the Caucasus and into Persia and Iraq, or through Turkey. On either route an invading force would be severely limited by the small capacity of the Turkish roads and railways. Once he had reached the. Syrian frontier the enemy would have three main lines of advance: the coastal road through Latakia, Tripoli and Beirut, the route east of the Lebanons through Aleppo and Damascus, and the route along the Euphrates, south-east to the Persian Gulf. Auchinleck’s first task in Syria was to plan a defence against an army advancing south from the Taurus mountains; in addition he had to be ready to send a force into Turkey if she was attacked, the British attaches in that country having been instructed by their Government to tell the Turks that by December at the latest an Allied army of four divisions would be available to help them.

Whatever opinion the British staffs held about the ability of the Russians to withstand the German onslaught, they could derive much comfort from the fact that each week during which Germany failed to win a decisive victory made it the more unlikely that she would attempt an advance through the mountains of Turkey in 1941. On 15th August General Blamey told the Australian Government that he considered that it was already too late for the Germans to attack before the spring of 1942.

It was accepted by the British commanders that if a German army advanced through Turkey and the Turks resisted the best course would be to move a British force northward and occupy the mountain passes of southern Turkey. On the other hand the Turks might let the Germans through, or might not permit a British advance into their territory; or it might be impossible to bring adequate British forces forward in time to meet the enemy in the passes. Once an invading army reached the plain of northern Syria it would be in country through which armoured formations could move with ease, and it had to be assumed that the German force would be stronger in armour than the British. Consequently General Wilson decided that the solution to his tactical problem was to prepare a main defensive line through the rugged country of southern Syria. This line travelled from Tripoli, past Baalbek and south-east to the lava-strewn country of the Jebel Druse and Transjordan.

The defence plan pictured the use of mobile forces based on a series of fortresses astride the main routes. The northernmost fortress would be round Tripoli and manned by one division. The others would be on or south of the Damascus-Beirut road. One, manned by two divisions, would

be in the area Zebedani-Dimas; another with one division in the Djedeide area; another round Merdjayoun; the Free French would be in the AM Sofar area on the Beirut-Damascus road. It was estimated that a total of two armoured and five infantry divisions would be required for the combined Syria-Iraq area.

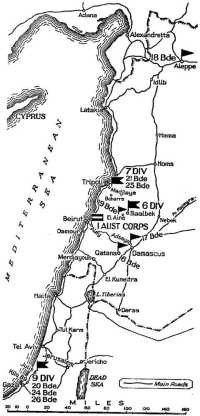

There was little prospect of four full divisions being available for the Syrian area in the near future, but in the meantime the formations in Syria could begin the work of siting, surveying and digging a defence system for an army of that size. At the end of July the garrison consisted chiefly of I Australian Corps (with headquarters at Aley). Under its command were the 7th Australian Division in the Tripoli area; the miniature Free French Division and 5th Indian Brigade round Damascus and Nebek; the 6th British Division at Baalbek with its brigades at Zahle, Horns and near Aamiq on the western wall of the Bekaa; and the 4th Cavalry Brigade at Aleppo. Outside this defence scheme was the 10th Indian Division which occupied that part of Syria east of the Euphrates,5 and thus stood astride the line of advance from Turkey to the Persian Gulf.

In the western zone, only the 7th Australian Division was complete in itself, but the 6th British Division’s lack of cavalry, artillery, engineers and machine-gunners was remedied by attaching to it a number of Australian units: the 9th Divisional Cavalry, 2/9th and 2/11th Field Regiments, the 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment, 2/15th Field Company, and two companies of the 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion. The 2/9th and 2/11th Artillery Regiments were “corps troops” and thus could be spared without depriving any Australian division of its guns. The reforming of a division of British regular infantry supported chiefly by Australian technical troops underlined the wisdom of including a full allocation of corps troops in the AIF – and the error of retaining in the Middle East large numbers of British regular battalions without sending there the artillery and other technical units needed to form them into effective fighting formations.

In the Tripoli area preparations were based on the assumption that the roads and railways leading from Turkey would support an enemy force of eleven divisions plus airborne troops. It was considered that the principal attack would be made along the axis Aleppo–Homs–Damascus–Lake

Tiberias, with a wide flanking movement through Palmyra; but that it was possible that the enemy might advance also along the coast. The Tripoli fortress was therefore to be prepared for all-round defence; General Allen considered that the performance of this task (in addition to the maintenance of a mobile force for counter-attack) would require two infantry divisions and one armoured. His division set out to construct a fortress area for a force of that size. Hope that a larger force would be allotted to the Tripoli area was dispelled, however, in October when General Auchinleck inspected the defences and informed General Allen that no troops would be added except possibly one tank battalion. Thereupon General Allen amended his plan to provide a shorter perimeter.

General Blamey disagreed with General Auchinleck’s plans for the defence of Syria. He considered that the “box” plan was static and fundamentally unsound and, in particular, that his troops digging these defences were being converted into mere labourers. He arranged with General Wilson that they should dig only two days a week and train on the other days. General Auchinleck, however, countermanded this arrangement. General Blamey protested strongly. At length a considerable force of civilian labourers was added.

Blamey’s protest on this occasion was symptomatic of a strong and fundamental difference of opinion with first Wavell and then Auchinleck. Blamey was convinced that the Middle East commanders had been unwise in frequently breaking up established corps and divisions and as frequently having to improvise new ad hoc formations. It was the period of “Jock columns” – brigade groups, or battalion groups, or even company groups – which had been appropriate enough in the kind of guerilla warfare which had preceded the Western Desert offensive in December 1940, but which, in Blamey’s opinion and that of other Dominion soldiers, were now of small value in themselves and a menace to sound tactical doctrine.6

At this time the doctrine which General Blamey criticised was receiving commendation from Mr Churchill. On 3rd July Churchill wrote to the Secretary for War and the Chief of the Imperial General Staff: “It is highly questionable whether the divisional organisation is right for armoured troops. A system of self-contained brigade groups ... would be operationally and administratively better. ... However, where divisional formations have grown up and have been clothed with armed reality the conditions of war do not permit the disturbance of a change. ...”7 Blamey expressed his opinion in the course of a cable to the Minister for the Army on 3rd August:

Outstanding weakness in past of Middle East has been failure to maintain organisation, even disregard of provisional organisation. If we have to meet

Germans in Turkey or Syria next spring essential organisation in army corps be foreseen and provided now. It is urged that for Australian Corps this should include air forces.

Events were to demonstrate that Blamey was right, but a year would pass and a new commander-in-chief and a new field commander would arrive in the Middle East before the principles he advocated would be adopted.

Blamey’s tactical doctrine ran parallel with his responsibility for realising the hope of the Australian Government that its oversea force should be grouped together under its own commander. By August, although single Australian divisions or brigades had fought in North Africa, Greece, Crete and Syria, and Australian Corps commanders had directed the field force in two of those campaigns, no two Australian divisions had been in action together. At the beginning of that month the 9th Division and a brigade of the 7th was besieged in Tobruk; some Australian units were in the Western Desert of Egypt; one unit was in Cyprus; the 6th Division was in Palestine; the 7th, brought up to strength with units of the 6th, in Syria, where several Australian units were now included in a British division. The 8th Division, less one brigade, was concentrating in Malaya. Each effort to assemble the corps had been defeated by the need hurriedly to send improvised forces to meet some new emergency.

At least as early as November 1940 General Blamey had a clear picture in his mind of the eventual size and shape of the Second AIF On the 15th of that month, having read an announcement by the Chief of the General Staff, General Sturdee, that the four infantry divisions would be Australia’s complete army effort, he wrote a long and wise letter to Mr Menzies in which he expressed the hope that this announcement had not been sponsored by the Government. “The reason given in the version that reached here,” Blamey added, “was the limitation of manpower having regard to other demands. ... I think Harold Holt [Minister for Labour and National Service] will find that this is not by any means the limit of our capacity in manpower. The details worked out by the Manpower Committee in my time there would correct this, and I am sure Sir Carl Jess has had it more completely worked out ere this.

“Looking forward I think we may take it for granted that when the armies clash ultimately in this war, the conditions of long drawn out attrition of the last war, with the consequent slow wastage in manpower, are not likely to be repeated. With modern armoured formations it is difficult to see long drawn out lines protected by wire, pill-boxes, etc., facing one another for long periods. The conditions of the present war will not give time enough to build suitable works – it can only be done in peace time as was the Maginot Line.

“It would seem that our whole aim as far as the army is concerned should be to have ready, when the time comes, the maximum of power for the series of land struggles that must determine the issue.

“Wishful thinking leads many into the error of believing that the war will be won by a combination of the blockade and air attack. Powerful as the blockade may be, it will take a long time before its effect is fully felt unless history’s teaching is false. The Germans are endeavouring to make its stranglehold less effective this time by playing up to Russia. We may be sure that their eyes are on the metal and food supplies of the Ukraine, and the oil of the Caucasus, in whatever propositions they are putting to Russia during Molotov’s present visit to Berlin.

“The Germans, too, have come to see that the air war can never finally determine the issue. They have learned this from the steadily increasing effectiveness of London’s defences. The German air force is being driven ever higher into the upper air and bombing becomes increasingly haphazard in its results. These limitations will gradually become more obvious, and the bombing of a large fixed area like London, or of vessels lying in the harbour, should not deceive us. As time goes on the Germans will protect their own production centres more and more effectively. While there can be little doubt that the RAF saved England from invasion and while meticulous care is taken to ensure that results of air conflicts are not exaggerated, personal experience during the last war makes me doubtful as to the results claimed from our bombing of German production centres. The claims of young and optimistic pilots as to destruction by night in Germany are not so subject to check as they are in air battles over England.

“For these reasons I am sure that there is only one wise policy for us, and that is to endeavour to develop our maximum striking power with all possible rapidity ready for the clash that must come. It is a question of numbers, organisation and equipment after the attrition period, i.e., the period of naval blockade and air destruction. The time will come to force the issue on land, and it does not seem possible that British military force alone without active American assistance can develop sufficient strength to overwhelm the Germans.

“It would seem that ultimate victory depends upon two prime factors; the first is the entry of America into the actual field, and the second the development, while time permits, of the armed forces of the Empire to their maximum strength for the struggle.

“If international developments, for example in the Balkan countries, do not force us into the extremely dangerous position of participating piecemeal in land warfare, we must spend all our energies between now and the summer of 1942 in preparation. I would press the point that we should determine our maximum possible effort now and plan for it.

“From this view I would stress that four divisions do not by any means represent Australia’s maximum, and nothing else will save us. I would urge that consideration be given to building this force up by the addition of at least two armoured divisions as soon as practicable.

“It will take time to accomplish, and therefore it should be begun systematically now. The men are the best material in the world for the task. The equipment could be planned for, and if it could be made

available before the end of the next northern summer, it would allow a few months for training.

“Our AIF is organised as a Corps of four infantry divisions. It can only be a completely self-contained force if it has its due proportion of armoured formations, and both for this war and looking to our national future, we should be a force fully organised.

“New Zealand has already recognised the realities of the position and her expeditionary force will now consist of one division and one armoured brigade.

“We have stuck to the infantry divisions probably because the AIF of the last war was composed of infantry divisions. Is it not the effect of looking backward? Surely it is time for a little forward thinking!”

On the 1st January 1941 the Government, having in July approved plans for making tanks in Australia, had authorised the formation of one armoured division as part of the AIF.8

Before the invasion of Syria a plan had been on foot not only to collect the Australian force together but to form in effect an Anzac Army. The grouping of the 6th Division with the New Zealand Division to form the “Anzac Corps” in Greece had awakened a desire for a closer association between Australian and New Zealand forces. In addition General Blamey felt that the welding of the formations would add strength to the whole military organisation in the Middle East. The project had been discussed by Generals Wavell, Freyberg and Blamey, and on 7th May, soon after Blamey’s appointment as Wavell’s deputy, the Australian and New Zealand Governments were informed by the Dominions Office that Wavell “would welcome the suggestion which had been made” that an Anzac Corps consisting of the 6th Australian and the New Zealand Divisions should again be formed, and placed under the command of General Freyberg. General Blamey cabled his approval of this proposal, which he elaborated by recommending that the 7th and 9th Australian Divisions be formed into an Australian Corps under General Lavarack.9 He explained that the tentative policy was to group pairs of infantry divisions into corps and attach armoured formations to them according to tactical requirements.

The Australian War Cabinet deferred a decision until Mr Menzies returned from London, and in the meantime asked General Blamey how many additional troops would be required to carry out the project, adding that difficulties were being encountered in Australia in finding men both for the munitions program and the fighting forces. Blamey’s proposal evidently suggested to the Ministers that he had in mind an Anzac Army10 consisting of two infantry corps to which British armoured formations would be attached if needed. “Is it intended,” Blamey was asked by the

Minister for the Army, “to set up any additional headquarters establishment which would form an additional Australian commitment such as an Army Headquarters to control both ... corps?”

Blamey replied on 30th May that the geographical separation of the divisions and lack of equipment for troops from Greece would make it impossible to concentrate the Australian and New Zealand divisions in one area as a complete force “for many months”. For the present his proposals aimed only at having the available divisions grouped into corps. He then elaborated his suggestion: The Anzac Corps would include an Australian aid a New Zealand division and 19,462 corps troops, of which 8,096 would be from New Zealand; the Australian Corps would be similarly constituted, but all Australian. In addition Australian base troops totalling 13,251 would be needed. Blamey listed the additional Australian units that would be required to provide corps troops for both corps, allowance being made for the provision of certain units by New Zealand. They included five artillery regiments (medium, anti-aircraft and survey) and a number of engineer, signals and service units with a total strength of 9,612; he suggested that all additional fighting troops be available by 1st December, all service units by 1st February. Each year 39,218 reinforcements would be required for the expanded Australian force in the Middle East – 45 per cent of its total strength of 87,152. There were then 77,660 Australian troops in the Middle East,11 10,017 in Malaya and the islands, and 44,279 of the AIF in Australia or at sea (including the armoured division and part of the 8th).

The adoption of Blamey’s proposal would have produced a force resembling the Australian-New Zealand contingent of 1916, when an Australian and an Anzac corps were formed comprising five Australian divisions and one New Zealand. Then Australia and New Zealand provided few of their own base and corps troops; on the other hand the population of each country had increased by about 40 per cent since 1916.

In May 1941 the shape of the AIF was being discussed also by Mr Menzies and the Chiefs of Staff in London. Menzies had asked the Chiefs of Staff to indicate the strength of the overseas force at which they considered that Australia should aim. In reply it was recommended that a fifth Australian division should be raised (making one armoured and five infantry divisions), which with the New Zealand Division would complete an Anzac Army of two corps each of three divisions; and that Australia should provide a number of ancillary units. The Chiefs of Staff stated that Australia, in common with other Dominions, was, broadly speaking, providing complete divisions, while corps and base units were being provided from British sources (a statement that, although true concerning base units, might in the ministers’ minds somewhat have exaggerated the proportion of corps troops which Britain was providing in the Middle East, where Australia was maintaining her due quota of them).

At this time the strength of a division was 17,500; the proportion of army, base and lines-of-communication troops to each division was 12,500. The proposal was made in London that, for each infantry division, Australia should furnish 3,500 of the 12,500 base troops, in addition to reinforcements and 6,000 corps troops, Britain providing the remainder; and that for the armoured division Australia should provide (in addition to the division of 14,000 men) 14,000 corps, army, and base troops. Thus, allowance being made for first reinforcements, the initial needs of each new division would be 29,000 men.

Menzies had been informed in London that the ultimate composition of the army in Britain was to be thirty-two divisions (including four Canadian). Until the autumn of 1941, only two of these divisions could be spared for service overseas – the 50th to the Middle East, the 5th to Northern Ireland. In the winter two more British divisions would be sent to the Middle East, if they could be spared from the defence of Britain and were not needed elsewhere. By the spring of 1942 there might be seventeen infantry divisions in the Middle East – six Indian, four (including the 8th) Australian, four British, two South African and one New Zealand.12 Acceptance of the British proposals would have necessitated increasing the AIF to 229,000 during the remainder of 1941.

Meanwhile the New Zealand authorities had considered the administrative problems involved in the initial proposal to re-form the Anzac Corps. On 25th June General Freyberg informed Army Headquarters at Wellington that the New Zealand Prime Minister, Mr Fraser, then in Egypt, had discussed the proposal with Generals Wavell and Blamey and himself and all favoured it. “It only requires the Commonwealth Government’s agreement to bring it into existence,” he added.13

When, after Menzies’ return, the Australian War Cabinet considered Blamey’s larger proposals, it decided that they should not be adopted until a complete review of manpower had been made. It had resolved to maintain the militia at 210,000; it was committed to raising a further 12,000 men to complete the armoured division; the Chief of the General Staff, Lieut-General Sturdee, considered that for some time ahead 7,000 a month would be needed to maintain units in the Middle East and 400 a month to maintain units in Malaya. In April, however, only 4,746 recruits had entered the AIF, and though the rate of enlistment increased (for example 4,467 were accepted in the fortnight which ended on the 10th May), the Cabinet decided on 2nd July that for the present the existing divisions of the AIF, including the armoured division, were all that

Australia could maintain in view of her other commitments – particularly to the Empire Air Training Scheme.

The Army staff in Australia based their calculations on higher casualty rates than the force had in fact suffered (or was to suffer) in the Middle East. In April there were 6,000 unallotted reinforcements in the Middle East, 7,300 were ready to embark from Australia in April, and 14,500 in May. Thus enough men were available to make possible the expansion which Blamey planned, and volunteers were coming forward in more than sufficient numbers to provide the reinforcements that he had asked for-39,000 a year, compared with Sturdee’s estimate of some 84,000. Indeed, in May they had enlisted at a rate equivalent to more than 100,000 a year.

The increase in recruits, so marked in May, and probably an outcome of the heavy fighting in April – news of such fighting usually caused a rush of recruits determined to help their fellows overseas – did not continue in June and July; in August, Sturdee, still basing his calculations on a far higher casualty rate than Blamey expected, informed the War Cabinet that the intake was not enough to maintain the AIF and, unless it increased, a reduction of the number of divisions would have to be considered.14 On the 13th August, the War Cabinet decided specifically that Australia could not agree either to the formation of two corps (of three Australian divisions and one New Zealand) in the Middle East or to the War Office’s proposal that Australia should maintain a corps of five infantry divisions, one armoured division and an armoured brigade, with ancillary troops. It decided that it would endeavour to increase the size of its existing divisions in accordance with recent changes in the British establishment (this would entail adding 7,000 to the strength of the whole force) but that it might later be necessary to abolish one of the infantry divisions in the Middle East and maintain there a corps of one armoured and two infantry divisions.15

In accordance with this prediction and because recruiting still lagged, the new Ministry of Mr Fadden16 on 17th September decided to convert the force in the Middle East into a corps of three divisions less one brigade group, but including an Army tank brigade, and to maintain only the armoured portion of the armoured division – the tank regiments but not the artillery, infantry and other units which such a division included. While that division remained in Australia these were to be

supplied by the militia; if it went to the Middle East they would be provided by breaking up one of the infantry divisions there. The decision was confirmed by the new Ministry led by Mr Curtin which took office on 7th October.

It is doubtful whether either Cabinet realised the full gravity of its decision – and improbable that Cabinets which included a quota of men who had seen extensive service in the old AIF would have agreed to it. In 1918 the breaking-up of Australian units for lack of reinforcements had led to mutiny, and it would be impossible to carry out the Ministers’ new plan without breaking up units with fine records and an intense esprit de corps, and converting others.

In the opinion of General Blamey the proposed reductions were not necessary. By October the divisions in the Middle East were at full strength or near it. There were reinforcements ready in the training units. Only one division – the 9th – was in action and it was soon to be relieved. In Australia were some 36,000 men of the AIF.17 As mentioned above, Sturdee, in his advice to the War Cabinet a few months before, had said that 84,000 men would be needed each year to maintain the AIF at its existing strength; Blamey that 39,000 a year would be enough. In fact, in the six months from April to September 38,300 men enlisted – nearly enough to meet Sturdee’s estimate of the requirements, and enough, according to Blamey’s estimate, to maintain for a year the expanded force which he had recommended. By December all units in the Middle East had been brought to full strength and there were still 16,600 men in the reinforcement pool.

At his own suggestion General Blamey was brought to Australia to confer with the new Curtin Ministry. He left Egypt early in November and at a meeting of the War Cabinet on the 26th he pointed out bluntly that he had not been consulted before the Ministers’ decision had been made and that he opposed it. He said that disbandment or conversion of units would damage morale, that there was no need for the AIF to maintain an armoured brigade, that the units needed to complete the armoured division should be raised either in Australia or the Middle East from reinforcements or by allotment of corps units, that the estimated scale of reinforcements was too high, and that there were enough reinforcements in the Middle East to ensure that the corps could be maintained during operations in the spring of 1942. A table of figures presented to the Cabinet predicted that enough volunteers would be received to maintain the AIF until late in 1942 when a shortage might occur. The Ministers reversed their decision, resolved that no change be made in the AIF organisation, and that the armoured division be completed with AIF

units. It recorded, however, that “ultimately” the number of infantry divisions would have to be reduced.18

Meanwhile on 20th September the New Zealand Government was still awaiting the Australian Government’s views on the re-establishment of the Anzac Corps. That day Freyberg cabled to his Prime Minister that the corps could not yet be formed because the 6th Australian Division was not yet re-equipped and trained and the 9th was in Tobruk.

The visit to Australia gave Blamey an opportunity of advising the Ministers on a subject that might soon become urgent. Although in most respects Turkey was observing a careful neutrality, British and Turkish staff officers (as mentioned above) had been discussing what action should be taken if the Germans attacked Turkey, as well they might. It was now considered certain that the Turkish leaders would keep out of the war as long as they could, but would resist invasion. If forces were sent to Turkey to help her meet a German invasion, it was almost certain that they would include Australian divisions now in Syria. Consequently, on 11th October, General Blamey had taken steps to warn his Government of the new possibility. He advised that, if asked to agree to the dispatch of the AIF to Turkey, the Government should make its agreement subject to the conditions that there should be a properly-devised plan and time to carry it out, properly-organised lines of communication and “a realistic order of battle and not one made up on paper, consisting largely of units that never existed, as was done for Greece”. Blamey told the Advisory War Council, at a meeting which he attended in November, that he considered that Germany would wish to by-pass Turkey and would favour an attack by way of the Caspian and the Caucasus, cutting off India. On Blamey’s advice Curtin agreed that the AIF might be moved into the Taurus mountains, provided that the operations had been adequately planned and prepared.

Meanwhile in Syria the garrison had increased in size, and the troops had continued surveying, digging and wiring defensive positions in preparation for this possible German incursion from the north. In September the X Corps headquarters moved into Syria. That month the 18th Brigade having been withdrawn from Tobruk rejoined the 7th Division. In October the 6th Australian Division, restored and re-equipped after its losses in Greece and Crete, and now commanded by General Herring, General Mackay having been recalled to Australia to command the Home Forces, replaced the 6th British Division (which, in its turn, renamed the “70th Division’, was to replace the 9th Australian Division in Tobruk). On 1st November the “Palestine and Transjordan” Command ceased to exist and General Wilson became commander of a new Ninth Army, embracing all troops in Syria and Lebanon, and with its headquarters at Broumane in the mountains above Beirut. The new army was chiefly Australian, and on 5th November twelve Australian officers, including a lieut-colonel of

Location of AIF, December 1941

the general staff (Barrett19), of the signals (Kendall) and the medical service (Saxby20), were appointed to its headquarters, and five to Palestine Area headquarters. The new army was a top-heavy organisation, with headquarters enough to control three times as many fighting formations as it possessed – an arrangement perhaps justified by the probability that if Syria was invaded several more divisions would be hurried into that country.21

In Syria there was a new outbreak of complaints about Australian indiscipline. Ten days after the cease-fire General Auchinleck received a copy of a note written by General Spears in which he said:

The Australians are already greatly feared by the natives. Their behaviour, with the exception of some specialised units which are well disciplined, would be a disgrace to any Army. They are alleged to have stolen Vichy officers’ wedding rings and to have deprived prisoners of their water-bottles. At Mezze aerodrome, by way of contributing their quota to the efficient conduct of the war, they stole and smashed vital parts of the Air France wireless installation which was the most efficient and most powerful post on French territory between France and Indo-China.

Auchinleck passed this on to Blamey, and at length it was investigated and reported on by Colonel Rogers, the senior liaison officer of I Australian Corps who had happened to be liaison officer with the formations on the Damascus front from 17th June to 16th July. Rogers made a careful inquiry and reached the conclusion that the accusations were unfounded, also, in one respect, “grossly libellous, mischievous and irresponsible”. Only two specific charges had been made against Australians since the campaign began: one of assault and robbery by an Australian and an English dispatch rider in company, and the other a charge not yet substantiated of theft of some equipment from Rayak and Aleppo airfields. On the other hand false rumours about Australian indiscipline had been numerous. He pointed out that as soon as it became evident that Australians were coming into disrepute in Damascus, and unjustly, Colonel Bastin, commander of the 9th Australian Cavalry, the largest Australian unit in the area, stopped all leave to that city, and was the first Allied commander to do so.

On 11th October General Wilson wrote the following letter to General Blamey:

I regret to say that I have had many cases brought to me recently of brutal assaults by Australian soldiers, either against other soldiers (British or French), police (military or civil) or civilians. I am taking this up with your Commanders as I feel that exemplary punishments will have to be given to put a stop to it, and I am asking your Commanders to let it be known that in future all cases of assault must be tried by General Court Martial. Perhaps if they get a whack of penal servitude with the first two years to be done in the Middle East it might have a deterrent effect.

I will not bother you with the details, but in some cases it has been due to neglect of picquets accompanying leave parties. Trouble has, however, occurred in Beirut, Damascus and Jerusalem. I thought you had better be aware of what is happening, and would be very glad of any advice you can give me as to how to deal with it.

Blamey replied recalling how earlier accusations against Australians had been proved baseless and adding: “It is a very convenient form of excuse for any happening to lay it on to broad Australian shoulders. But when it is not in accordance with fact it does an immense amount of harm to the relations between the various Empire forces.” He concluded: “I am afraid that the question of discipline of the AIF is entirely one for my action”; and enclosed a copy of relevant passages from his instructions from the Government.

In reply Wilson sent Blamey a list of two cases of fracas in cafes in Jerusalem, one involving two and the other seven Australians, and a note of a charge pending against an Australian who on 29th September had allegedly attacked a lieut-colonel and a nursing sister as they were leaving a hotel in Damascus.

A report which Blamey obtained from Corps headquarters stated that since the end of the operations in Syria, two months before, the following charges had been made against men of the Corps and its two divisions: assaults on other troops, 17; on police, 4; on civilians, 27. In 15 cases

the guilt of an Australian had been established; 33 cases were awaiting investigation or decision.22

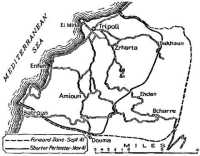

As winter approached, General Blamey, who had ski-ed in Australia, persuaded General Allen that ski troops should be trained to operate in the Taurus mountains soon to be snow-covered; he considered also that skiing would provide a pleasant recreation during this period of garrison service. There were at corps headquarters several officers who were accomplished ski-runners, among them Major Savage,23 of the Signals, who was also a leader of the bush-walking movement in Australia. In October he was instructed to prepare plans, and the following month was appointed to form and conduct a ski school. When instructors were sought, hundreds of enterprising soldiers applied but few had reasonable qualifications. Savage proposed that outstanding Australian skiers (including Captain Mitchell,24 serving in Malaya with the 8th Division, and Sergeant Jack Thomas25) be flown to Syria. When this proposal failed, he obtained, from the Spears Mission, Major James Riddell, who had ski-ed for Britain at the Olympic Games of 1936; Lieutenant E. D. Mills26 of the 6th Cavalry Regiment who was a Tasmanian langlauf champion; Bombardier Stogdale,27 who had won Australian championships; Sergeant Abbottsmith,28 a former instructor at Mount Kosciusko, and others.

With much difficulty equipment was obtained – skiing was a comparatively new sport in the Lebanon – and a Mount Kosciusko manual was reprinted. The school took over a hotel and barracks above Bcharre in the Lebanons at 6,500 feet, and there an initial class of some seventy officers and men were trained; it included artillery officers and signallers whose task would be to occupy observation posts above the snow line.

The intention was to form a ski company of about 200 men for each Australian division.29 Their role would be to patrol, on skis in winter and as mountain troops in summer, the lofty mountains between the 7th Division round Tripoli and the 6th round Baalbek and Damascus. The snow which blanketed Syria and the Lebanon that winter was said to be the heaviest for thirty years, and for three weeks no vehicles were able to reach the school. Injured men were taken to hospital on sleighs made of galvanised iron sheets turned up in front – Major Savage remembered having read of such sleighs being used by the Australian light horse in the sand of Sinai in 1916.30 Hard training and many experiments were carried out, but before the course was completed the men were ordered to rejoin their units.

Throughout the AIF lack of equipment was not now a serious problem. No longer was it desirable for units partly to equip themselves at the expense of the enemy; indeed it was no longer permissible. A postscript to the period of persistent shortages is provided by a file of letters concerning an incident in the history of the 2/16th Battalion. It was reported to headquarters in Jerusalem that on the 6th October two aircraft flying over the area of the 2/16th in Syria had been fired on by a Breda heavy machine-gun; the aircraft were British. Brigadier McConnel,31 chief of staff of British Forces in Palestine and Transjordan, sternly asked I Australian Corps to explain whether that battalion or any other battalion had Breda machine-guns and by what authority. At length the enquiry reached Colonel Potts of the 2/16th who explained that aircraft, flying low, failed to give recognition signals and were engaged – with two Bredas which men of his battalion had assembled from parts salvaged at Mersa Matruh in April and May, and had used with good effect against enemy aircraft in the Syrian campaign. Might not they be retained? Brigadier Stevens supported the request, as did General Allen. Lieut-Colonel Elliott on Corps staff was sympathetic. The correspondence had then occupied twenty days. In the meantime the Ninth Army had come into being. Its chief of staff was Brigadier Baillon,32 who had been on exchange to the

Australian Army when war began, and had come to the Middle East as a major on the staff of the 6th Division. Baillon’s reply, though recognising the “initiative and enthusiasm shown by 2/16th Australian Infantry Battalion” was firm; the guns must be returned to Ordnance. It marked the end of a phase.

In October and November the German advance in Russia continued, although more slowly. They pressed nearer to Moscow, took Kharkov, entered the Crimea. To the men digging and training in Syria the possibility that they would next meet a German army advancing from the mountains of Asia Minor seemed not remote. In mid-November came encouraging news from their old battleground in the Western Desert. The Eighth Army (more imposing title of what had formerly been “Western Desert Force”) under General Cunningham attacked towards Tobruk. Bardia was retaken and Tobruk relieved. Almost on the same day Gondar, the last main stronghold of the Italians in Abyssinia surrendered. By the end of November it was evident that the German advance in Russia had been checked and the Russians would have a winter during which to recover. The outlook in Russia and the Middle East was relatively bright when, on the 8th December (Australian time), the news sped round the world that the Japanese had attacked Hawaii, Malaya, and the Philippines.

One immediate outcome of Japan’s entry into the war was a request from General Sturdee in Australia that certain senior officers be sent back from the Middle East to fill key appointments in Australia. Two valued leaders, General Mackay and Brigadier Rowell, had already been sent home to pass on experience gained on active service. In the course of the discussion about the reinforcement of the AIF General Blamey had advised in October that Brigadiers Savige and Murray should return to conduct a recruiting campaign. On 11th December General Sturdee asked also for Brigadiers Plant (25th Brigade), Vasey (19th Brigade), Clowes (C.R.A. of I Corps), Robertson (commanding the Reinforcement Depot), and a group of senior technical officers and others. The four brigadiers (four of the five regulars who had commanded infantry brigades, or corps or divisional artillery, in action in the Middle East) were promptly sent, as were Savige and Murray.33

Soon the question of sending reinforcements from the Middle East to the Far East was being keenly discussed; and on the 3rd January a message arrived at Canberra from the Dominions Office stating that two divisions and one armoured brigade were being sent to Malaya, and two divisions to the Netherlands Indies. Two of the four were to come from the Middle East, to be replaced later from England; it would be of the greatest assistance if the Australian Government would agree that the divisions sent to the Netherlands Indies should be Australian. On the 6th the Australian Government informed the British Government that it agreed

to the sending of the 6th and 7th Divisions, with the corps headquarters, corps troops and base units to the East.34

The men of the AIF in the Middle East seem not to have been greatly stirred by the Japanese attack. Relatively few of the unit war diaries recorded it. One battalion historian wrote that it was “not treated seriously at that time”, another that the Japanese problem then had “no sense of urgency for us”; there seem to have been few who considered that Australia itself might soon be threatened.

The day following that on which the Australian Cabinet agreed that a corps of two Australian divisions be sent to the Far East the 9th Division was ordered to relieve the 7th in Syria, and on the 15th January the advanced headquarters of the 7th moved from Tripoli in Syria to Julis in Palestine. Between the 21st and 28th small parties of officers, including Generals Lavarack and Allen set off by air to Java. The Corps which was to follow totalled 64,151. The 6th Division was 18,465 strong, the 7th 18,620; there were 17,866 corps troops and 9,200 base and lines of communication troops. From the 30th January onwards this force set out in a procession of convoys for the Far East.