Chapter 1: The “Minimum Possible Force” Guards Cyrenaica

In February 1941 Greece was at war with Italy, but not with Germany. The British Commonwealth was at war with both Axis powers. Of the other nations of the world, though few were unconcerned and some had aligned themselves closely with one or other belligerent group – as Russia had, for example, by the Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact – none was committed to fight. When it came to fighting, Britain’s only allies outside the Commonwealth were the handful of governments-in-exile of already vanquished nations and the homeless people who still gave them allegiance And although by day and by night the naval and air forces of both sides were carrying on the struggle on all seven seas and under them, and in all skies within their reach, British Commonwealth ground forces were in action in one theatre only, the Middle East.

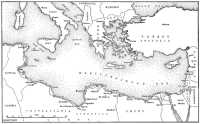

The Mediterranean, though one sea, comprises two distinct basins linked by a sea passage through the Sicilian Narrows. In 1940 and 1941 the Axis powers were well disposed to dominate both basins by deploying their preponderant air power across the Narrows from Italian airfields in Sicily and North Africa. Isolated Malta, alone still challenging Axis supremacy there, could surely be neutralised and, if need be, overcome. For complete mastery of the Mediterranean, however, more was needed: first, control of its three gateways – the western gateway at Gibraltar and the two gateways to the eastern basins, the Suez Canal and the Dardanelles – and then domination or neutralisation of the whole littoral to sufficient depth to protect the seaways from sustained air attack. This in turn would necessitate gaining control of the territories on the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean then held by British forces. Of utmost strategic importance on the North African coast was Tunisia, which afforded the shortest sea-route between Europe and Africa across the central Mediterranean; yet in the peace terms imposed on France Hitler had been content to leave this territory under French control.

Even while the German High Command had been pressing forward with preparations to invade England, Hitler had considered the possibility of German participation in land operations in North Africa. An offer of collaboration by German forces had been made to Italy, but the Italians had not immediately accepted.

When later the German High Command had turned with misgiving from the project of invading England, the Chief of the German Naval Staff, Admiral Raeder, had lost no opportunity to impress upon Hitler the importance of the Mediterranean theatre. The seizure of Gibraltar with Spanish collaboration, an advance through Syria with the acquiescence of Vichy France, and a thrust by the Italian forces in North Africa into western Egypt had then been proposed by Hitler as first steps towards

bringing the Mediterranean completely under Axis control. Later, when Italy’s attack on Greece, mounted without consultation with her ally, complicated German plans, and by its first failures threatened to weaken the Axis position in the eastern Mediterranean, Hitler determined to occupy the Greek peninsula with German forces.

But no sooner had the German leader outlined a pattern for action in the Mediterranean theatre than he was induced to change it. Early in December 1940 Franco made it known to the German High Command that Britain would have to be reduced to the point of collapse before Spain would actively participate in war against her. Having no wish to add to the number of his enemies, Hitler ordered the discontinuance of preparations to seize Gibraltar. About the same time, General Sir Archibald Wavell’s desert army began an advance which soon threatened the Italian forces in Africa with total destruction. Finally Hitler took the most fateful decision of an evil career when, on 18th December, he issued a directive which set his armed forces that most formidable task: the overthrow of Russia. “The Army,” stated the directive, “will have to employ for this purpose all available troops, with the limitation that the occupied territories must be secured against surprise.”

The intention to subordinate military effort to this single, paramount aim was clearly stated. Mediterranean operations, except to the extent that they involved the security of the southern flank of Germany’s eastward thrust towards Russia, now fell into a place of secondary importance in Hitler’s thought and strategy. The conquest of eastern Europe would be completed, the northern Mediterranean seaboard firmly held. But henceforward German policy for operations across the Mediterranean, whether in Africa or in Asia, was to be marked by opportunism and inconstancy. The High Command adhered to no fixed purpose, but with each change of fortune changed its policy. If Axis forces in Africa were advancing – if the Suez Canal and the Middle Eastern oilfields seemed prizes within easy reach – aims became more ambitious, plans bolder. If their advance was checked, or if military power in Africa seemed for the moment to

be in the balance, interest waned; limited objectives were set. If disaster threatened, the greatest efforts were made to retrieve the situation.

Of just such an opportunist character was the German decision taken early in 1941 to revive the shelved plans for sending a German force to Africa1 and yet to assign to the force only the very limited tasks of securing the defence of Tripolitania and possibly later taking part in a short advance to Benghazi.

The British War Cabinet, on 7th February 1941, immediately after the capture of Benghazi, directed General Wavell that his “major effort” should go into lending all possible aid to Greece, that he should press on with plans for occupying the Italian Dodecanese, and that he should hold the western flank of the Egyptian base at the frontier of Cyrenaica and Tripoli. Immediately Wavell had to regroup the forces under his command. In addition to the tasks laid down by the War Cabinet’s directive, he was committed to operations in Eritrea and East Africa, the early conclusion of which would set free forces greatly and urgently needed for use elsewhere.

The forces Wavell had available were:–

In the Western Desert:–

7th Armoured Division 6th Australian Division

In Egypt:–

2nd Armoured Division

6th British Division (in process of formation) New Zealand Division

Polish Brigade Group

In Palestine:–

7th and 9th Australian Divisions (less one brigade and other units still in transit from England, and one battalion still in Australia)

In Eritrea:–

4th and 5th Indian Divisions (engaged in front of Keren)

In East Africa:–

1st South African Division

11th African Division

12th African Division (about to begin operations against Kismayu)

Of the two armoured divisions, the 7th had been fighting continuously for eight months and was mechanically incapable of further action, while the 2nd was not at full strength: it had only two cruiser regiments and two light-tank regiments. Moreover, when the latter division had arrived in Egypt its commander, Major-General Tilly2, had told Wavell that his cruiser tanks were in appalling mechanical condition. The engines had already done a considerable mileage, the tracks were practically worn out. It had been intended to fit fresh tracks specially made in Australia when the division arrived in the Middle East, but these proved “practically useless” and the old tracks were retained. Writing afterwards, Wavell said

that it was hoped that the old tracks “would give less trouble in the desert than they had at home3”. Yet there were no tank transporters in the Middle East in those days. Even if these tanks were to be shipped to Tobruk or, still farther, to Benghazi (in the event, they were shipped to Tobruk), there would remain great distances over rough ground to be traversed on their outworn tracks to reach a front where they would be required to operate over very broken country. To hope for a reasonable performance was to be unreasonably optimistic

Of the infantry, the divisions engaged in East Africa and Eritrea were committed to other tasks. If, however, operations there proved as successful as hoped, one Indian division might become available in about two months and possibly one South African division – provided that the Government of South Africa would agree to its employment so far afield. The African divisions of native troops, however, were not suitable for employment in the operations required by the War Cabinet’s directive.

Thus the infantry available in the near future consisted of one New Zealand division, three Australian divisions, one British division and the Polish Brigade; but of the five divisions only three were completely equipped. Field guns and other supporting arms were scarce. The artillery regiments of the British division and of one Australian division had not yet received their guns.

Wavell decided to split his only available armoured formation, sending part – the better part – to Greece and retaining the rest for Cyrenaica. To the Grecian expedition and the assault on the Dodecanese he allotted all his available infantry except one division and more than half of the armoured division; the remaining infantry division and the rest of the 2nd Armoured Division would have to suffice for holding the western frontier of Cyrenaica. But would it suffice? To every available formation under his command he had allotted an operational role. Patently there was a danger that compliance with the War Cabinet’s wishes might involve his having forces committed to combat simultaneously in Greece, Cyrenaica, East Africa and the Dodecanese; unless this could be avoided he would be left with no general reserve.

In effect, Wavell had decided that “the minimum possible force” then necessary to secure his western flank was an armoured force of the strength of one very weak armoured brigade operating with one battalion and a half of motorised infantry and one division of static infantry, and with artillery support on about the normal scale for an infantry division. He had plans for some early strengthening of this force, but not to any substantial extent.

Even before it had been split between two theatres, the 2nd Armoured Division with its outworn cruisers had had but two-thirds of the normal number of tanks of an armoured division. To augment the tank strength of what now remained Wavell decided to provide an additional tank battalion and to equip it with captured Italian medium tanks. He also

The Eastern Mediterranean

planned to make available the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade (of three motor battalions) as soon as its training had been completed. But no other reinforcements were contemplated in the near future.

Wavell “estimated that it would be at least two months after the landing of German forces at Tripoli before they could undertake a serious offensive against Cyrenaica, and that, therefore, there was not likely to be any serious threat to our positions there before May at the earliest”. He calculated that it would be safe to garrison Cyrenaica with comparatively unequipped and untrained troops so long as they could be made ready for battle by May, when, he hoped, reinforcements of at least one Indian division would also be available from the Sudan4.

Wavell originally intended that the battle-tried 6th Australian Division, already in Cyrenaica, should be the western-frontier force’s infantry division and that the Australian contingent for Greece should comprise the 7th and 9th Divisions. Lieut.-General Sir Thomas Blamey (G.O.C. AIF Middle East) insisted, however, that the 6th Division should be one of the two to go to Greece, for he was determined that the contingent for so hazardous an expedition should be formed of his best-trained troops. Wavell was therefore obliged to relieve the 6th Division with one of the other Australian divisions, a change in his plans which involved relying on a raw and partially-equipped formation to provide the infantry component of the frontier force.

To enable the best-trained Australian units to be sent to Greece General Blamey carried out an extensive reorganisation and regrouping of the AIF in the Middle East. The formation that constituted the 9th Division before this reorganisation and the formation that emerged from it as the 9th Division, assigned to the task of garrisoning Cyrenaica, were very differently composed. Of its original three brigades, but one remained with it; of the battalions now comprising its infantry, not one had originally been raised for the 9th Division.

Since its fortunes over a period of almost two years will be the principal concern of this volume, it will be worthwhile to review the division’s origins and to see of what units it was now composed and what degree of training they had achieved.

The decision to form a fourth AIF division, to be known as the 9th Australian Division, was made by the Australian War Cabinet on 23rd September 1940. But many of the units of which it was to be constituted had already been formed: most of them were originally raised for either the 7th or the 8th Division. Already three complete AIF infantry divisions with normal complement of supporting arms and two additional infantry brigades without supporting arms, had been raised. These were the 6th Division in Egypt and Palestine, the 7th and 8th in Australia, and in England the 18th Brigade (the headquarters and battalions of which had originally belonged to the 6th Division before that division was reduced in size from twelve to nine battalions) and the 25th Brigade, which had

been formed in England mainly by a reorganisation of troops who had arrived there in the same convoy as the 18th Brigade. Two additional field regiments and two medium regiments had also been formed in Australia as corps troops for the I Australian Corps.

It was decided that the two brigades in England would form the nucleus of the new (9th) division and that its commander would be Major-General H. D. Wynter, then commanding the force in England. To provide the artillery for an additional division three field regiments would be required. These were to be found by utilising the two corps field regiments and by converting one of the corps medium regiments to field artillery. To complete the division, an additional infantry brigade, an anti-tank regiment and engineer, medical, and supplies and services units would be raised in Australia. It was intended that the new division should be assembled in the Middle East, together with the 6th and 7th Divisions.

When General Blamey was advised of these decisions, he criticised the policy of combining the two brigades in England – composed of some of the first-enlisted and best-trained troops in the AIF – with units yet to be raised whose training would take a considerable time to complete. He insisted that the new division should be made up from units already formed. It was therefore decided to take the 24th Brigade, the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment and the field companies from the 8th Division to bring the 9th Division up to strength, and to use new units to be raised to replace the transferred units in the 8th Division which, bound for Singapore, had less prospect of early operational employment. Thus the infantry of the 9th Division was to comprise the 18th and 25th Infantry Brigades, then with Major-General Wynter in England, and the 24th Brigade then in Australia.

Wynter was appointed to command the division on 23rd October 1940. He sailed from England on 16th November for the Middle East, where the division was to be assembled; in the same convoy was one of his brigades, the 18th. At Capetown he left the convoy and flew to Cairo, arriving on 18th December. Immediately he commenced consultations to settle arrangements for the assembly of the division and the reception of the various units as they reached the Middle East. On 24th December he opened divisional headquarters at Julis in Palestine. Colonel C. E. M. Lloyd, who had already been appointed his chief staff officer (GSO1), joined the headquarters on the same day.

Two field regiments and a field company in Palestine were the only units of the division already in the Middle East but about one-third of its strength, including the 18th Brigade, was then at sea and due to arrive at the end of the month. On 3rd January 1941 two more convoys set sail: from England came the 25th Brigade and some other units; out of Fremantle sailed the 24th Brigade (less one battalion) and most of the divisional troops raised in Australia. The 24th Brigade began to arrive in the Suez Canal area at the end of January. The 25th Brigade did not arrive until the second week in March, by which time it had been transferred to the 7th Division.

General Wynter was never to exercise command of the 9th Division as an effective formation. In mid-January 1941, Brigadier L. J. Morshead’s 18th Brigade was detached for duty in the desert (and to prepare for operations against Giarabub) and the divisional engineers were sent to Cyrenaica where, together with the 2/4th Field Company, they were employed on maintenance and construction work, initially in the area from Tobruk to Derna. Before either of his other two brigades had arrived in the Middle East, Wynter fell seriously ill. It soon became clear that he would not be fit for operational employment in the foreseeable future and would have to be relieved of his command. Brigadier Morshead was appointed to succeed him, yielding command of the 18th Brigade to Lieut.-Colonel G. F. Wootten. It was fitting that Wynter’s mantle should fall on Morshead, who had loyally served under Wynter although the latter had superseded him to command the force in England5.

Morshead was informed of his appointment on 29th January. After handing over his brigade to Brigadier Wootten at Ikingi Maryut and reporting to General Blamey at corps headquarters in Cyrenaica, he arrived at divisional headquarters at Julis on 5th February and assumed command6. While Morshead had been reporting to Blamey, the 24th Brigade and other divisional units from Australia had been disembarking in the canal zone and moving to camps in Palestine. For the first three weeks after his appointment, Morshead was mainly concerned with arrangements for their training.

–:–

It was on 18th February that Wavell gave Blamey the outline of the plan to send a force to Greece, and it was probably also at this meeting that Blamey advised Wavell that the 9th Division, not the 6th, should be assigned to Cyrenaica Command.

On 19th February, Mr Anthony Eden, the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and General Sir John Dill, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, arrived in Cairo to take charge of negotiations with the Greek Government. On 23rd February the Greek leaders accepted the British offer to send an expeditionary force. The planned regrouping of Wavell’s forces, which had already been put in train, now proceeded swiftly. On 24th February, Blamey’s I Australian Corps headquarters left

Cyrenaica, handing over operational command there to Cyrenaica Command. On the same day, a battalion of the Support Group of the 2nd Armoured Division – the 1st Battalion, Tower Hamlets Rifles – arrived in Tobruk; on the next, the Support Group of the 7th Armoured Division left for Egypt. On 26th February, Lieut.-General Sir Philip Neame arrived at Cyrenaica Command headquarters at Barce to take over the command (on the 27th) from Lieut.-General Sir Maitland Wilson, who had been appointed commander of the expedition to Greece.

General Neame was a British regular officer who had had a varied and successful career marked by gallantry in the first world war, during which, after serving in the front line with distinction and being awarded the Victoria Cross, he held a number of staff appointments, finally becoming senior staff officer of a division. When the second war was about to break out, Neame was at first chosen to be Chief of the General Staff to the British Expeditionary Force but eventually went to France as Deputy Chief of Staff. In February 1940 he was transferred to the Middle East to command the 4th Indian Division and in August of that year was appointed General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Palestine and Transjordan. He experienced some disappointment at not receiving command of the Western Desert Force in Wavell’s first campaign; he had a claim for consideration on the ground of seniority7. Thus it was natural that this professionally eminent commander with a gallant record should now be chosen for appointment to the Cyrenaican command.

On 26th February, the day on which Neame arrived in Cyrenaica, Blamey gave directions for the reorganisation of the AIF in the Middle East. The detailed orders were issued at Headquarters British Troops in Egypt at a staff conference called by the I Australian Corps, just arrived from Cyrenaica. The 18th and 25th Brigades, the original nucleus of the 9th Division, were to be transferred to the 7th Division, the 20th and 26th Brigades from the 7th to the 9th Division. The infantry of the 9th Division would now comprise the 20th, 24th and 26th Brigades, the artillery, the 2/7th, 2/8th and 2/12th Field Regiments and the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment. The regrouping was to be effective forthwith “as a temporary expedient only”. The 9th Division, less its field artillery which was not yet equipped or fully trained, was to be prepared to move to Cyrenaica immediately to relieve the 6th Division. The 20th Brigade, which would go first, was warned to be prepared to move within 24 hours. It was intended that this brigade, which had been formed two months earlier than the others and had been longer in the Middle East, should take over in the forward zone while the remaining brigades would be employed on garrison duties in the Derna–Tobruk area and undergo further training.

The division was one infantry battalion short of full strength. Only two of the three battalions of the 24th Brigade had arrived: the third, the 2/25th, had remained on garrison duty at Darwin when the brigade had sailed from Australia and was not due to arrive until the end of April.

Thus General Morshead found himself in command of an infantry division composed of brigades selected by the test that they were the least trained or most recently enlisted, and now destined for garrison duty on a frontier where the enemy was in contact. That the division might become heavily engaged in two or three months was not merely possible, but likely. Morshead’s urgent task was to move his division to Cyrenaica, see to its training and equipment, and build it into a team before the enemy could interfere. There was much to do to fit the division for war.

Morshead laboured under a number of disadvantages. The foundations for a divisional esprit de corps were lacking. They would have to be laid. He had a most competent assistant in Lloyd, his senior staff officer, but as yet only a skeleton staff. In the case of only one of the brigades (Brigadier E. C. P. Plant’s 24th) had there been any personal contact between Morshead and the brigade commander or between Morshead’s headquarters and the brigadier’s staff, and then only for a period of less than a month. Within a week Plant departed to take charge of the newly-constituted Rear Echelon Headquarters of the AIF in the Middle East. Two of Morshead’s brigades, Brigadier Murray’s8 20th Brigade and Brigadier Tovell’s9 26th Brigade, had just been divorced from their parent formation, the 7th Division, to which they felt they belonged. Their pride had been hurt. Just as a soldier who had enlisted early in the war would distinguish himself from one who joined later by his lower “army number”, so men cherished the honour of belonging to a low-numbered unit, units the honour of belonging to a low-numbered division. The 18th Brigade, for example, retained their 6th Division colour patches until the end of the war. To be transferred from the 7th to the 9th Division seemed to the 20th and 26th Brigades like demotion. It was moreover unfortunate that the brigade commanders and heads of other arms and services in the division should have been told that the regrouping would be effective as a temporary expedient only, as they were in the notes circulated by Lloyd summarising the conference on 26th February at which the new organisation was laid down. A belief in the permanency of the arrangements was needed to foster in the transferred units a sense of belonging to the division, solid achievement to foster their pride in so belonging.

The 20th Brigade, formed in May 1940, had been in Palestine three months, the 26th Brigade, formed in July 1940, about two months, and the 24th Brigade, also formed in July, less than one month. Not one unit had been issued with its full complement of arms; but although “mock-up” weapons had been used for much of the training, each unit had fired automatic weapons in range practice. Individual training of the men was well advanced and there had been some sub-unit training, but battalions

and regiments had not yet been exercised as units. Hence the training of the brigades as battle groups had not even begun. The state of training may be inferred from statements of two of the brigadiers at a conference called by Major-General J. D. Lavarack (who was then their divisional commander) on 14th January. “I shall be ready,” said Murray, “to go on with battalion training during the week after next,” and Tovell commented: “We will have completed platoon training by 14th February, when company training will be commenced.” In short, the soldiers had been trained to fight but the officers and staffs had yet not been trained in battle management.

The responsibility, laid on Morshead, of swiftly moulding these raw units into a division fit for the vital role of frontier defence was not light; but he was qualified to bear it. He was not a professional soldier, yet had been soldiering all his life, in peace, and in war. As a young man he had made soldiering his consuming hobby when, before the first world war, he began his civilian career as a schoolmaster. He was a captain at the Gallipoli landing, saw heavy fighting on the first day and the six months that followed, was wounded and invalided to Australia, but not out of the army. He was soon appointed to raise a new battalion, the 33rd, which he trained, took to France and commanded with distinction until the armistice. Dr Bean has described him in those days as a battalion commander marked beyond most others as a fighting leader

in whom the traditions of the British Army had been bottled from his childhood like tight-corked champagne; the nearest approach to a martinet among all the young Australian colonels, but able to distinguish the valuable from the worthless in the old army practice ... he had turned out a battalion which anyone acquainted with the whole force recognised, even before Messines, as one of the very best10.

Between the wars Morshead combined success in business – he became the Sydney manager of the Orient Line – with continued interest in soldiering. He commanded a militia brigade for seven years; once he devoted part of a business vacation to visiting army training schools and attending manoeuvres in England. When war again broke out in 1939, he was chosen – at 50 years of age – to be a brigade commander of the 6th Division. There could have been few generals in 1941 able to match his experience of front-line warfare and in the exercise of command.

Morshead was every inch a general. His slight build and seemingly mild facial expression masked a strong personality, the impact of which, even on a slight acquaintance, was quickly felt. The precise, incisive speech and flint-like, piercing scrutiny acutely conveyed impressions of authority, resoluteness and ruthlessness. If battles, as Montgomery was later to declare, were contests of wills, Morshead was not likely to be found wanting. He believed that battles and campaigns are won by leadership – leadership not only of senior but of junior commanders – by discipline, by that knowledge begotten of experience –

knowing what to do and how to do it – and by hard work. And above all that, by courage, which we call “guts”, gallantry, and devotion to duty11.

Unsparing, unforgiving, outspoken in criticism, he was yet quick to commend and praise when he thought men had fought as they should; such men he respected, admired and honoured. “Ming the Merciless” was the unduly harsh nickname by which he first came to be known in the 9th Division; softened later to just “Ming”, as a bond of mutual affection and esteem grew up between the general and his men.

Morshead’s task would have been harder, particularly in the early days, when his headquarters were short staffed, if he had not had the competent assistance of Lloyd as chief of his headquarters staff. Lloyd was well described by Chester Wilmot12:

Big and bluff, Lloyd has a manner that is a strange mixture of bluntness and friendliness. His initial bluntness springs from a dislike of humbug and a desire to come straight to the point; but those who stand up to him and have something to say find him most approachable. He is no respecter of persons and is essentially a realist who sees a job to be done and goes about it in the most direct way13.

Lloyd was a regular soldier, commissioned in 1918, but his interests extended beyond soldiering as he proved by later taking a degree in law at Sydney University. Possessed of organising ability and always willing to accept responsibility, he was well qualified to carry out the primary function of a chief staff officer: to ensure that the commander’s intentions are carried out and that he is not troubled with inessential problems.

–:–

The 20th Brigade (2/13th, 2/15th and 2/17th Battalions) was the first to move to Cyrenaica. On 27th February, the day after the brigade’s transfer to the 9th Division had been announced, the first road convoy bearing Brigadier Murray’s headquarters set out from Kilo 89. The first train left at 7 p.m. on the same day with the 2/13th Battalion on board. Within two days the whole brigade was moving westwards, mainly by train, across the Suez Canal and to Mersa Matruh where the desert railway terminated. On 2nd March, a bleak day of cold and rain, brigade headquarters and the 2/13th Battalion both reached Mersa Matruh, closely followed by the 2/15th and 2/17th. There for the first time the men saw the transformation war can cause. The little Mediterranean port was ringed by a wired perimeter and anti-tank ditch, dug defences and minefields; its buildings bore the scars of bombing; many were empty shells.

On 3rd March, the brigade moved in four convoys, with brigade headquarters in the van, to Buq Buq; on the 4th to Tobruk. Next day the troops were permitted to explore the fortress, littered as it was with the debris of war; but a searing sandstorm blew up, blotting out the sun

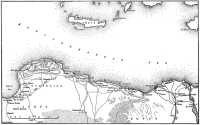

The Western Desert

and discouraging all except the most determined ramblers. The opportunity would come later.

On 6th March the brigade moved out to west of Derna. In the morning the 9th Division suffered its first war casualties. The convoy bearing the 2/13th Battalion was attacked for half an hour by five Heinkel aircraft: two were killed and one wounded, and some damage was done to vehicles. In the afternoon, the convoys descended by the magnificent Italian-built road, the Via Balbia, from the high escarpment to the small port of Derna, a town of white houses and flowering shrubs, but climbed the escarpment again by a zigzagging pass to the west of the town, and there camped for the night. Next day the brigade continued on to Tocra, leaving the desert to pass through a land of wooded hills and green plains. Italian settlers still toiled in the fields, as if the war had never been.

On 8th March the brigade, in the final stages of its journey, passed the outskirts of Benghazi along an avenue of Australian gum-trees, then drove south out into the desert to the Agedabia area. The 2/13th was detached and sent to the coast near Beda Fomm, less one company which was left at Barce as a security guard for the headquarters of Cyrenaica Command.

Divisional headquarters arrived at Tobruk on the same day. On 7th March, Morshead and Lloyd had flown from Cairo to Cyrenaica Command headquarters at Barce. Morshead was to take over responsibility forthwith for the fighting troops in western Cyrenaica from Major-General Sir Iven Mackay (commanding the 6th Australian Division), upon whom their command had devolved when Blamey’s headquarters had left for Cairo on 24th February. On arrival at Barce, Morshead learned from Neame that his responsibility for the forward troops would be of limited duration. It was intended that on or about 19th March the headquarters of the 2nd Armoured Division should take over command in the frontier area from the 9th Division and that, while the 20th Brigade would stay in the forward zone, Morshead’s headquarters should move to Ain el Gazala to exercise command of the remainder of his division and supervise its training. Thus one brigade of Morshead’s division would assume a major operational role by providing the main infantry component of the frontier force but would not be under his command. Morshead told Neame that he was “not impressed with this arrangement14”.

On 8th March Morshead and Lloyd arrived at the 6th Division headquarters to take over command from Mackay, who flew to Cairo on the 9th to prepare for the move to Greece. And on the 9th Brigadier Murray arrived at Brigadier S. G. Savige’s headquarters to arrange for the 20th Brigade (which had arrived the night before) to relieve the 17th Brigade.

At the time of the relief the frontier force comprised Savige’s experienced infantry brigade group and the lighter elements of one inexperienced armoured brigade. Savige’s brigade held positions near the small haven of Marsa Brega, in dunes and rolling ground surrounded by marshes. The

area was naturally strong in defence but vulnerable to encirclement from the south. The protection of the southern flank was the responsibility of the 3rd Armoured Brigade (Brigadier Rimington15) and had been left to a shadow force consisting of the 3rd Hussars (with an effective strength of 32 aged, light tanks) and an infantry support group of two motorised companies of the 1st Free French Motor Battalion. Forward reconnaissance to the frontier at El Agheila and to the south was being carried out by the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards (Lieut-Colonel McCorquodale16), an armoured-car regiment recently converted to a reconnaissance role. To the rear a squadron of the 6th Royal Tank Regiment was being equipped with captured Italian M13 tanks at Beda Fomm, while the 1/Tower Hamlets Rifles, a motor battalion (which with the two Free French motorised companies constituted the half-strength Support Group of the 2nd Armoured Division17) was guarding prisoners of war at Benghazi. The 1/Northumberland Fusiliers, a machine-gun battalion, was similarly employed. The Tower Hamlets was a highly mobile unit but not suited to holding ground in prolonged defence, since it could place only about 250 men on the ground.

The main tank strength of the one armoured brigade was at El Adem, south of Tobruk, some 400 miles distant from Marsa Brega by the desert route (500 miles by the well-built coast road). Here were the 5th Royal Tank Regiment, with its outworn cruisers, and the 6th Royal Tank Regiment (less the squadron at Beda Fomm) reorganising before moving to Beda Fomm where it was to equip itself with the captured Italian tanks.

In artillery – the only arm that could stop tanks – the force again was at half strength. Instead of six or seven field regiments – normal complement of a corps of two divisions – the frontier force had three; instead of two or three anti-tank regiments, it had only one battery. The 1st Royal Horse Artillery arrived on 10th March. The other two field regiments (104th Royal Horse Artillery and 51st Field Regiment) and the anti-tank battery (“J” Battery, 3rd Royal Horse Artillery) did not come forward until the last week of March. The 51st was equipped with first-world-war 18-pounder guns and 4.5-inch howitzers, a number of which were in workshops18.

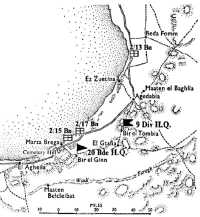

The relief of Savige’s brigade by Murray’s was completed before midnight on 9th March Immediately after dusk, Lieut-Colonel Marlan’s19 2/15th Battalion and Lieut-Colonel Crawford’s20 2/17th Battalion moved up to the Marsa Brega area. The 2/15th Battalion relieved the forward companies of the 2/5th and 2/7th Battalions half a mile north-east of

11th March 1941

Marsa Brega while, some ten miles farther back, the 2/17th relieved the main body of the 2/7th Battalion. Lieut-Colonel Burrows’21 2/13th Battalion (less the company at Barce), as brigade reserve, remained in the Beda Fomm area near the coast some 13 miles south-west of the town and was ordered to provide detachments to guard important road centres. On 11th March 9th Division headquarters arrived at Bir el Tombia to relieve 6th Division headquarters, and command passed to the 9th Division on the 12th. But when the relief was completed Morshead had in Cyrenaica only one of his infantry brigades; the other two were still in Palestine.

A small but important unit did not share in the general relief of the 6th Division: the 16th Anti-Tank Company remained to give support to the foremost troops. The company had left Tobruk at the end of February for the frontier region, where it had been placed under the command of the 3rd Armoured Brigade. The 2/1st Pioneer Battalion was another unit to remain: its headquarters were at Derna with companies engaged in engineering and repair work throughout Cyrenaica, at Benghazi, Tmimi, the Wadi Cuff and Tobruk. Also in western Cyrenaica, now engaged in engineering work from the Barce plain, north-east of Benghazi, to the frontier zone, were the 9th Division’s engineers and the 2/4th Field Company.

To hold so important a frontier, though but temporarily, with only one untried infantry brigade and a few light tanks, and to plan further to hold it for a prolonged period with little more while the main force of the 9th Division completed its training, were bold decisions, typical of Wavell’s strategy and military direction. They were based on a reasoned, and indeed reasonable, appreciation. “My estimate at that time,” Wavell told Churchill a month later, “was that Italians in Tripolitania could be disregarded and that the Germans were unlikely to accept the risk of sending large bodies of armoured troops to Africa in view of the inefficiency of the Italian Navy22.”

In the field of Intelligence, as in every other respect, Wavell was short of the means to provide a fully effective service. In obtaining information of enemy activity in Tripolitania he was handicapped in two respects: first, because the provision of Intelligence from this area had been regarded as a French responsibility until the collapse of France, for which reason the British had not established their own network of clandestine agents before hostilities opened, and second, because the increasing superiority of the German Air Force in this region severely hampered, and to a degree prevented, British reconnaissance from the air. Yet, however much Wavell and his staff may have been assailed by doubts and uncertainties, and even though they may have momentarily erred, in retrospect what is remarkable is the accuracy of their assessments of enemy strengths and the almost exact correspondence of Wavell’s appreciations with the actual intentions of the German High Command. There was occasionally a time lag in obtaining information, but not a great lag; there were at times wrong estimates but not gross miscalculations of enemy strength. The real and great lack was not Intelligence but the means to counter the risks Intelligence revealed.

In one important instance, however, the time lag may have vitally affected the whole course of the war in the Middle East. On the day on which Greece accepted the British offer of an expeditionary force (23rd February), Headquarters Cyrenaica Command stated in an operational instruction addressed to General Mackay:–

At present there are no indications that the enemy intends to advance from Tripolitania. His principal effort will probably continue to be made in the air.

On the very next day, 24th February, Lieutenant Williams’23 and Lieutenant Howard’s24 troops of the King’s Dragoon Guards and Lieutenant T. Rowley’s troop of anti-tank guns of the 16th Australian Anti-Tank Company were ambushed near Agheila by a German patrol of tanks, armoured cars and motor-cycle combinations. Three prisoners, including Rowley, were taken by the Germans25. This was the first contact on the ground between British and German, forces in Africa. The Germans could not have timed it better.

Other evidence of the arrival of German and Italian reinforcements quickly accumulated and on 2nd March, while Morshead’s headquarters and Murray’s brigade were travelling post-haste to Cyrenaica to take over the defence of the frontier from the 6th Division, Wavell told the Chiefs of Staff that the latest information indicated that two Italian infantry divisions, two Italian motorised artillery regiments and German armoured troops estimated at a maximum of one armoured brigade group had recently arrived in Tripolitania. Wavell’s comment was:–

Tripoli to Agheila is 471 miles and to Benghazi 646 miles. There is only one road, and water is inadequate over 410 miles of the distance; these factors, together

with lack of transport, limit the present enemy threat. He can probably maintain up to one infantry division and armoured brigade along the coast road in about three weeks, and possibly at the same time employ a second armoured brigade, if he has one available, across the desert via Hon and Marada against our flank26.

In fact Wavell was now acknowledging the possibility that he might be faced with a German armoured force twice as strong as any he himself could field. He tended, however, to underrate the danger. He gave his appreciation thus:-

He may test us at Agheila by offensive patrolling, and if he finds us weak push on to Agedabia in order to move up his advanced landing grounds. I do not think that with this force he will attempt to recover Benghazi.

Wavell added that eventually two German divisions might be employed in a large-scale attack but, because of shipping risks, difficulty of communications, and the approach of the hot weather, he thought it unlikely that such an attack would develop before the end of summer He did not yet know who was the commander of the German force in Africa; but within a week he learned that his opponent was General Rommel, a fairly junior commander with, however, an impressive record as a tactician in both infantry and armoured warfare.

It is idle to conjecture whether Churchill, Eden, Dill and Wavell would have still offered to lend aid to Greece if they had known earlier of German intentions to send a strong armoured force to Africa, or to consider how they might then have deployed their forces. The important fact is that when the new hazards became apparent they did not change their plans. The Australian Government was not informed of the danger that now appeared to threaten one of its divisions. The oversight is easy to understand, though less easy to justify. Churchill and Wavell, and Blamey even more so, were preoccupied with the seemingly greater risks looming up in the path of the British expedition to Greece. Moreover Blamey had not at this stage adopted the practice of proffering independent advice to his Government27.

What enemy forces had in fact arrived in Tripolitania? And what were the German and Italian plans for the coming months? The considerations that led to the German High Command’s decision to intervene in Africa and the steps taken early in 1941 to do so have been related earlier in this series28. Early in January, a formation to be known as the 5th Light Motorised Division was improvised for employment in Africa by detaching units from the 3rd Armoured Division: lacking medium or heavy tanks, it was similar to the support group of a British armoured division. Later the division’s establishment was revised and strengthened, the most important addition being two battalions of medium and light tanks. For a brief period in early February, as the British westward advance in Africa continued unchecked, the Germans hesitated to proceed, fearing that their forces might arrive in Africa too late; but on 3rd February, while

apparently not committing himself irrevocably to the dispatch of the whole force, Hitler directed that the move should commence; and even while the hesitancy persisted, and while the 5th Light Division was still in process of formation, he decided that, if this formation were sent, a complete German armoured division would later be added to the force. He so informed Mussolini on 5th February. On 6th February the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Field Marshal von Brauchitsch, instructed General Rommel to take command of the expeditionary force. His first task would be to make an immediate reconnaissance in Libya. Rommel saw Hitler on the same day and was informed that Hitler’s chief adjutant, Colonel Schmundt, would accompany him on his reconnaissance

Swift action was taken to get the German force moving. On 8th February the unloading party of the 5th Light Division sailed from Italy; on the 10th, the first transport echelon sailed; other convoys followed in the next few days. Meanwhile the British advance had come to a halt on the Cyrenaican frontier. Anxiety lest the German division might be attacked before its assembly at Tripoli could be completed was soon allayed.

This German decision to intervene in Africa was no translation from realms of fantasy into action of Hitler’s summer dream of assaulting the Middle East simultaneously from the north (through the Caucasus and Syria) and the west (through Cyrenaica). The ambition to conquer Russia had caused that grandiose project to be shelved. The intervention was made simply to stave off the danger of imminent conquest of Tripolitania by Wavell’s desert force; though doubtless, when the German High Command decided to retain a foothold in Africa, it envisaged the destruction of British power in the Middle East as the eventual, if distant, outcome.

The Italian forces then in Tripolitania consisted on paper of four infantry divisions and an armoured division. But the infantry divisions comprised little more than their infantry battalions (six to a division), almost all their supporting arms having been lost in the campaign just ended, and the armoured division, 132nd (Ariete) Division, though it had some 80 tanks, lacked anti-tank weapons, partly because of shipping losses. A fifth infantry division – 102nd (Trento) Motorised Division – was in the process of arriving at Tripoli.

The composition of the German force to be transferred to Africa was laid down in orders issued by the Army Command on 10th February. Its fighting component was to be the 5th Light Division, which had now become an armoured formation, but weaker than a normal German armoured division. Moreover, the German command, preoccupied with the problem of finding equipment for the coming invasion of Russia, and assuming that the division would have the comparatively passive role of constructing and holding a defensive position, had made a one-third reduction in its allocation of motor transport. Nevertheless by British standards this was a formidable formation, far stronger than the depleted 2nd Armoured Division it would oppose. It consisted of a headquarters, a tank regiment, a machine-gun regiment, a reconnaissance battalion, an

artillery regiment, two anti-tank battalions, an anti-aircraft battery, an air reconnaissance unit, and supply, maintenance and other services. The tank regiment comprised two battalions, and had some 150 tanks, more than half of which were medium tanks armed with either 50-mm or 75-mm guns. The machine-gun regiment had two fully motorised battalions, each with its own engineers. One of the anti-tank or tank-hunting (Panzer-Jäger) battalions was armed with the 50-mm anti-tank gun, the other with the versatile 88-mm anti-aircraft gun, to be used in a ground-to-ground role, certainly the most effective tank destroyer used in the fighting in Africa. Again, the eight-wheeled armoured cars of the reconnaissance battalion outmatched, as the British were soon to discover, the Marmon-Harringtons of the King’s Dragoon Guards in both hitting power and cross-country performance. Field artillery was the only major armament in which the German formation was not stronger than the British force opposing it. Moreover the German combatant units drawn from the 3rd Armoured Division had had operational experience in Poland and France.

It was laid down that Marshal Gariboldi, who had just replaced Graziani as Italian commander in Libya, was to be Commander-in-Chief, North Africa. Rommel, though empowered to offer “advice” to the Italian commander, was to be subject to his tactical direction, but responsible to the German authorities in other respects. It was stipulated, however, that German formations were to be employed only in self-contained units of at least divisional strength under German command. On paper Rommel’s responsibilities were similar to those of the commander of a Dominion contingent under Wavell. Rommel, however, was not one to measure and define his authority by referring to the wording of a staff instruction.

Rommel’s character was the one decisive factor in the enemy situation that Wavell failed to appreciate correctly. Although in his fiftieth year, Rommel’s vitality still burned with a scorching flame. A professional soldier who had known no other profession, nor any other interests except his home life, he had chosen the army for a career at the completion of his schooling and thereafter devoted himself to his profession with complete absorption. In the first world war, as an infantry officer, his career was distinguished by exceptional initiative and endurance. After the war he was one of the professional officers selected for retention in service when the Treaty of Versailles reduced Germany’s army to a strength of 100,000 effectives and 4,000 officers. Between the wars he became an instructor at an infantry school, the commander of a mountain battalion, an instructor at a war academy, an adviser to the Hitler Youth Organisation, the commandant of another war academy, and finally the commander of Hitler’s bodyguard. It is said that Hitler chose him for this appointment after reading Infantry Attacks, a manual on infantry tactics of which Rommel was the author and which was based on his lectures at the infantry school. Rommel held this position when the war broke out and during the campaign in Poland. Later Hitler gave him command of the 7th Armoured Division, which he led with success in the campaign in France, adding to his reputation not only by excelling

in the “lightning war” principles of mobile operations but also by his habit of personal command and leadership in the forefront of the battle.

The British Intelligence service knew the outline of his military career. When, about 8th March, it was learnt that he was the commander of the German Africa Corps, enough was known to conclude that here was an audacious, indeed impetuous, and able commander and a good tactician, with a flair for flank attacks. These were not unusual characteristics for a man selected to command a detached force. But the exceptional drive, the bent for taking risks, the flair for seizing opportunities and exploiting success were yet to be revealed; and if these qualities were not fully appreciated, another could scarcely have been foreseen: a penchant for acting independently of higher formation that would impel him to exceed his own personal authority, transgress the explicit orders of the German High Command and overstep the limits it laid down for the employment of his forces. So Wavell, while correctly judging what the German command intended, misjudged what their subordinate might do.

The belief current on the British side during the war that the German troops destined for Africa had received special adaptive training is not supported by the evidence29. There were some unfruitful experiments to devise ways of improving the wading capacity of vehicles through sand, but the only problem that appears to have received much study was the loading, unloading and transportation of armoured fighting vehicles. The first vehicles intended for Africa were not fitted with diesel engines (which desert experience later proved to be the most practical) because it was feared they might overheat; motor vehicles had twin-tyres, which caused considerable trouble because stones lodged between them. The first tanks were not equipped with oil filters. The importance of fresh food was overlooked. These and other mistakes were speedily corrected; much other improvement of equipment was undertaken in the light of experience; but the Germans did not arrive in Africa with perfected equipment. Nor had they received any special training or acclimatisation for desert conditions. On the other hand their well-tested and robust equipment was not likely to need much adaptation, nor was it likely that troops well trained in an established battle-drill and already tempered by practical experience in war should have any difficulty in accustoming themselves to a new terrain.

Rommel arrived in Rome on 11th February to consult with the German military attaché, General von Rintelen, and the Italian authorities. There he announced that the first line of defence would be at Sirte – some 150 miles west of the British advanced positions at El Agheila – and the main line at Misurata, midway between Sirte and Tripoli. Doubtless Rommel was echoing Brauchitsch’s instructions.

On 12th February Rommel flew to Tripoli. “I had already decided,” he wrote afterwards, “in view of the tenseness of the situation and the sluggishness of the Italian command, to depart from my instructions to confine myself to a reconnaissance, and to take command at the front into my own hands as soon as possible, at the latest after the arrival of the first German troops30.” The first battle units of the German force – the reconnaissance battalion and one of the anti-tank battalions – arrived there on the 14th, only two days later. Rommel immediately ordered them forward to Sirte. On the same day, he told the German Army command that it was his intention to hold Sirte, to carry out reconnaissance raids immediately to acquaint the British with the arrival of the German force and to conduct an offensive defence with air cooperation. On 16th February, the first detachments of the X Air Corps arrived. It had a strength in serviceable aircraft of 60 dive bombers and 20 twin-engined fighters and in addition could call on German long-range aircraft based on Sicily. Its task was to move the airfields up as close to the front as possible and to attack both air and ground forces of the British in the forward area. On 19th February the High Command directed that the German military force in Africa should be known as the Africa Corps.

By the end of the month, the advanced force of the 5th Light Division was well forward of Sirte in the En Nofilia area, with forward reconnaissance units at Arco dei Fileni, later known to the British as Marble Arch. There in the middle of the desert Air Marshal Balbo had erected a huge florid archway supporting two giant statues of the legendary Phileni brothers, to commemorate in one monument both his own construction of the Via Balbia, the magnificent coast highway spanning Italian North Africa from Tunisia to Egypt, and the patriotism in ancient times of the Phileni, whose self-sacrifice in agreeing to be buried alive, according to the legend, enabled a frontier dispute between Carthage and Cyrene to be peaceably settled. “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.” What sentiment more fitting for a Fascist to extol! Arco dei Fileni was some 40 miles from the frontier at El Agheila. Spaced at intervals along 200 miles of coast road behind the advanced forces were the Bologna and Pavia Divisions (infantry), the Ariete Division (armoured), and the Brescia Division (infantry). Another division (Savona) and other garrison troops were in Tripoli.

Rommel had now acquainted himself thoroughly with his problem. On 1st March he issued an appreciation. It is clear that he was still thinking only in terms of resisting a resumed offensive by the British, but it is interesting to note his appreciation of the ground and how clearly he perceived the dominant tactical importance of the salt lakes west of El Agheila. The line from Marada (a desert oasis 75 miles south of El Agheila) to the salt lakes south-west of El Agheila was, he said, the ideal defence position against any attack from the east. In the north the only ground requiring to be held was a strip of land on either side of the road, which could be defended by a reinforced battalion. If a battalion

were placed in Marada, the enemy would have to use tanks to make an attack. If he attempted to thrust across the difficult terrain south of the salt lakes, he could easily be halted by a formation of the strength of the 5th Light Division with good support from the air. “Since I cannot count on the arrival of reinforcements for several weeks,” he wrote, “it appears to me to be essential (a) to occupy the coastal strip west of El Agheila at the most favourable point and to defend it resolutely, employing mines and mobile forces; (b) to occupy the area south of the salt lakes in order to interfere with enemy ground reconnaissance and, in close cooperation with the air force, to halt the advance of larger enemy forces. As yet it seems too early to occupy Marada, since the forces there are still insufficient.” He added that the ultimate aim should be to occupy the El Agheila salt lakes – Marada line with about two static divisions and strong artillery and to assemble the mobile troops – “e.g. 5 Light Division, 15 Panzer Division, Ariete and motorised divisions” – behind them for offensive defence.

On 1st March General Leclerc’s Free French forces, operating from Chad Territory, took Kufra oasis. On 3rd March Rommel moved forward the advanced force of the 5th Light Division and began the construction of a defence line in the pass 17 miles west of El Agheila, between the salt lakes and the sea; to prevent this position from being bypassed, other defences were constructed to the south. By 9th March, the day on which Murray’s brigade relieved Savige’s brigade at Marsa Brega, Rommel felt that the immediate threat to Tripolitania had been eliminated; on that day he suggested to the German Army Command (OKH) that it might be possible to pass to the offensive before the hot weather started. He suggested three objectives: first, the reoccupation of Cyrenaica; second, northern Egypt; third, the Suez Canal. He proposed 8th May as the starting date and detailed the reinforcements he would need.

On 11th March the 5th Light Division’s armoured regiment, equipped with its tanks, completed its disembarkation at Tripoli. On the 13th Rommel moved his headquarters forward to Sirte, and on the same day ordered the occupation of Marada (on the inland flank of the El Agheila position), which reconnaissance had shown to be unoccupied. Two days later he dispatched a force south into the Fezzan, partly to allay Italian fears engendered by Leclerc’s capture of Kufra oasis, but mainly to test the performance of German motorised equipment in long marches across the desert.

Meanwhile Wavell’s “minimum possible force” guarded the frontier.