Chapter 2: Defence Based on Mobility

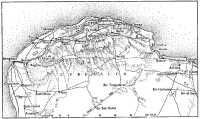

For two years and a half, from the summer of 1940 to the winter of 1942, the British and Axis armies in Africa fought each other across a strip, about 600 miles long, of comparatively passable land bordered on one side by the Mediterranean, hemmed in on the other by hardly traversable sand seas and partially closed at both extremities: by salt lakes near El Agheila, and by the morass of the Qattara Depression south and west of El Alamein. On the inland flank were important oases – Gialo, Giarabub and Siwa – and Kufra deep in the desert – which attracted and supported subsidiary operations, but the crucial battles were fought within 50 miles of the sea, some much closer. Problems of supply compelled the armies to hug the coast for most of the time, their occasional sweeps inland being no more prolonged than their tactical purposes necessitated. Apart from the railway to Mersa Matruh, later extended to Tobruk, a single main road along the coast, which linked Egypt with Tripolitania and Tunisia, served as the primary supply line to both armies.

The armies and their supply columns trundling back and forth across this arid coast land had by no means an unobstructed passage. Salt lakes, sand dunes, cliff-faced wadis1 and escarpments constricted movement in many places. In much of the desert over which the 9th Australian Division fought, a long, steep escarpment was the dominant feature. In western Egypt the main escarpment emerged from the desert near the Qattara Depression and ran westward parallel to the coast, becoming gradually steeper, until it turned north into the sea near Salum. Here, at the pass of Halfaya, the main coast road tortuously climbed up from the maritime plain to the plateau. “Bottleneck” is a good metaphor to describe this western outlet of Egypt.

Across the Libyan border the northern scarped edge of the plateau ran from Bardia through the Tobruk perimeter to Gazala, the southern edge from near Fort Capuzzo through Sidi Rezegh, Ed Duda and El Adem to the Rigel and Raml Ridges (overlooking what was to become the battlefield of Knightsbridge): farther west the ridges became less distinct and the southern edge gradually converged on the northern. The part of the northern escarpment enclosed by the Tobruk perimeter divided above the harbour so as to form two escarpment lines that parted and rejoined within the perimeter. The southern perimeter posts of the fortress were south of the escarpments and looked out across the plateau.

West of Gazala, about midway between Tripoli and Alexandria, lay the “hump” of Cyrenaica, where the “Green Mountain”, the Jebel Achdar, rose from the desert, gathering winter rain to water its slopes. Girdled by the walls of two escarpments, the mountain rose precipitously in three

The Jebel Achdar

terraces: from the sea in the north, where the bottom escarpment fronted the shore, and from a maritime plain in the west towards Benghazi. From the south (or inland) side the ascent was less abrupt; but the Jebel’s shoulders here were rough and scarred, and dissected by many gorges. Hence the southern slopes formed a flank more easily ascended than traversed.

South from Benghazi the Jebel Achdar’s rain-giving influence was lost: the maritime plain rapidly became arid. The escarpment, a wall of limestone, hemmed the plain in, running parallel to the coast for about 60 miles and gradually diminishing. There was a cleft in the escarpment at Esc Sceleidima, where it was ascended by the track and telegraph line leading to Msus. Beyond Antelat it became lost in the desert.

Along the shores of the Gulf of Sirte, from north of Agedabia to west of El Agheila, sand dunes and chains of salt lakes and marshes fringed the coast whilst the country inland was a desolate waste. Some of the salt lakes were very large, particularly those west and south of El Agheila – where Rommel had noted that they formed an ideal defensive position – and at Marsa Brega, now held by the 20th Brigade.

Several tracks, but no formed roads, traversed the Cyrenaican hinterland south of the “hump”. From El Agheila the Trigh el Abd, an age-old caravan route led across the desert to the oasis of Bir Tengeder whence one track branched off northwards to Mechili whilst the main track continued northeast to link with the caravan routes coming out of Egypt. From Mechili other tracks led north (to Giovanni Berta and to Derna) and east (to the Gulf of Bomba and to El Adem).

The lie of the land had certain tactical consequences not all of which appear to have been sufficiently taken into account. The hill country

of Cyrenaica was very favourable to the defence; but although a force ensconced there could threaten the flank of an army crossing the desert to the south, its own supply line would be very vulnerable. There were only two ports within the protection afforded by the Jebel Achdar’s ramparts – the tiny harbours of Derna and Apollonia; these did not have the capacity to sustain a large force. So an army on the Jebel had to be sustained by road from either Benghazi or Tobruk and could only maintain itself on the mountain massif if it dominated the approaches to its supply port and line of communications. Thus it could be compelled to give battle in the desert. It must either defeat the armour of a hostile force in open warfare or block it at some defile, if a suitable one could be found.

The defile at El Agheila, which could not be outflanked except by a long march through difficult terrain, was the only place on the western approaches to Cyrenaica where overland movement was substantially constricted, so that to defend Cyrenaica from the west it was necessary either to hold the hostile force on the El Agheila line or to win a battle of manoeuvre in open country. In such a battle, infantry would be of little account: the armour would determine the issue.

When the British forces halted on the western frontier of Cyrenaica at the conclusion of Wavell’s first campaign, a plan to defend the captured territory against attack from the west was made, which rested on the concept of engaging the enemy at the southern outlet of the Benghazi plain. General Wilson, writing after the war, described it thus:–

The escarpment follows the coast from east of Benghazi southwards ... and loses itself gradually as it nears Antelat where there is easy rolling desert offering excellent scope for a tank battle: nearer the frontier the country is too flat and marshy while to the south difficulties with deep sand are encountered. I recommended that the defence of Benghazi should be from a flank pivoted on the end of the escarpment and that for this the line of supply to Msus and thence south of the Green Mountain should be maintained2.

Later the plan was modified, at General Blamey’s suggestion, by advancing the line to Marsa Brega. Wilson’s scheme of defence was evolved when the superiority of the British armour over any the Italians could field was incontestable. Its hypothesis was that the armour could invite and win a battle in the open country between Antelat and Agedabia: both El Agheila and Marsa Brega were regarded as only outpost lines. But the concept of pivoting the defence on the Antelat escarpment lingered on in later plans developed after the situation had vastly changed. On 23rd February, the day before first contact was made with German ground forces, Cyrenaica Command headquarters instructed General Mackay (then in command of the force on the frontier) that the role of the forward troops in the unlikely event of the enemy’s adopting the offensive would be to delay him until reinforcements could be brought up, and that, in accordance with this policy, the 3rd Armoured Brigade would assemble at Antelat while the remainder of the 6th Division

(that is, other than the brigade at Marsa Brega) would be brought up east of the Antelat-Sceleidima escarpment; from this area both formations would attack the enemy in flank or rear should he continue his advance3. The instruction was not changed when the arrival of German forces was confirmed, nor when their strength was ascertained.

When General Morshead succeeded to General Mackay’s responsibility, he lost no time in acquainting himself both with the units committed to his command and with the territory to be defended. He visited, in turn, the forward infantry, the armour in the forward area and the army-cooperation squadron operating from the airfield at Agedabia (No. 6 Squadron, RAF). He viewed the situation he found with some apprehension. The aircraft of the cooperation squadron reported a constant increase of enemy vehicles near the frontier while other aircraft, investigating at longer range, disclosed considerable shipping activity in Tripoli Harbour, also ships moving to the small ports east from Tripoli. German aircraft were becoming increasingly aggressive; Morshead’s own headquarters were compelled by bombing attacks to execute a short move. The armoured cars of the King’s Dragoon Guards were being persistently bombed and machine-gunned. Their patrols continued to report increased ground activity near the frontier, though on 13th March a patrol reported that Marada oasis appeared to be unoccupied. On the same day, Lieutenant MacDonald4 of the 2/15th Battalion, with a sergeant and eight men, and an escort of two armoured cars from the King’s Dragoon Guards, travelled about 45 miles into the desert and patrolled the south-western approaches to El Agheila. Although they met no enemy they saw trails left by reconnoitring tanks. Australian engineer patrols of the 2/3rd Field Company led by Lieutenant Bamgarten5 which were reconnoitring for water to the south-west deep into the desert, even beyond Marada, brought back similar reports. On the 14th, the King’s Dragoon Guards captured a lone German airman in the desert who contended that he had parachuted from a plane that crashed into the sea. From him it was learnt that the enemy had laid a deep minefield astride the coast road about 15 miles west of El Agheila.

Morshead knew that in the estimation of Wavell’s headquarters it was probable that a complete German armoured brigade had arrived in Tripolitania, including a regiment of tanks (at least 150 tanks, probably 240), and that it was thought new arrivals might possibly bring the German formation up to the strength of a complete armoured division6. Moreover the appreciation of Middle East headquarters was that the enemy was likely to initiate an early offensive reconnaissance against El Agheila and seize it, if he found the opposition weak, as an advanced base for future operations. Morshead’s own strength near the frontier was a light-tank

regiment, an armoured car regiment, and an infantry brigade, with another tank battalion in process of equipping itself with captured Italian tanks of doubtful value. This force, observed Lloyd, his chief staff officer, in a report written a week later, was “completely without hitting power”. It lacked the strength even to fight for information by aggressive reconnaissance. In weapons of passive defence (excepting field artillery) it was no better provided: there were only 15 anti-tank guns (nine 2-pounders and six Bredas) and 19 light anti-aircraft guns (16 Bofors and 3 Bredas) in the whole frontier region. Moreover the vital defile west of El Agheila had not been secured nor were any ground troops holding El Agheila itself. Major Lindsay7 of the King’s Dragoon Guards took an armoured car patrol up to the fort at El Agheila each morning at first light but retired at dusk.

There was much else to concern Morshead. Not only was the frontier force too small; in every branch there were deficiencies of equipment. Every unit, every service was short of motor transport and the deficiencies were becoming progressively worse because the few vehicles possessed were overworked and spare parts were lacking to maintain them. “Two lorries sent to Tobruk ... several days ago to get essential spares came back with a speedometer cable only,” wrote Lloyd, on 26th March. Because of enemy bombing, Benghazi had not been used as a supply port since 18th February: all supplies had now to be brought up by road from Tobruk, a distance of over 400 miles from the forward area. In second-line transport the division had been provided with only one echelon of a divisional supply column8: this, it was thought, should suffice for the daily requirements of an estimated force of one brigade (with divisional troops). However, the task involved a turn-around of 150 miles a day, half of it made in the dark hours and half in the daylight when attack from the air was likely – and no day passed without a strafe along the Benghazi–Agedabia road, called “bomb alley” by the Australians. The strain was telling, not only on the vehicles, but on the men.

Just as serious was the lack of equipment for the signals sections. Colonel C. H. Simpson, the Chief Signals Officer of I Australian Corps, had told Lloyd in Cairo that the situation in the forward area could be dealt with by the signal sections of the infantry brigades and a small detachment for divisional headquarters. On arrival it was found that in the provision of signals equipment (as in the case of motor spares) the requirements of the force for Greece had been given absolute priority. “We arrived,” Lloyd reported, “with a detachment of No. 1 Company consisting of one officer and 12 other ranks possessing three W/T sets, six telephones, three fuller-phones9, two switchboards and one mile of cable. These stores were obtained mainly by theft.” The battalions had also left Palestine without signals equipment. But the personnel of signals

sections did not lack initiative; each battalion section had “acquired” much essential equipment. In a note written in Tobruk about two months later, one commanding officer remarked: “There has never been a phone issued to the battalion, yet we have over 20 miles of wire and 16 sets of phones working (all Italian), found, repaired and installed by my own personnel10.”

The methods of unauthorised acquisition were various. At Tobruk, near Derna, and north of Agedabia, large quantities of abandoned Italian equipment littered the countryside, much of it collected into temporary dumps pending removal to depots, some of it lying where the original owners left it. As the units of the division paused at these places on their westward journey to the frontier, “scrounging” parties scoured the country and the dumps, searching for, and appropriating to themselves, not only personal perquisites but essential fighting equipment. The diarist of the 2/17th Battalion wrote of his unit’s halt near Agedabia on 9th March, where it was waiting until the fall of darkness would permit its forward move to Marsa Brega: “The day is spent by the battalion fossicking in the area of the dumps. ... Valuable equipment is secured here to assist the battalion, which is alarmingly ill-equipped – three motor-cycles, some hundreds of camouflage sheets, several Breda and Fiat guns, ammunition, tools and many odds and ends.” A less commendable method of drawing stores is revealed in the diary kept by a member of a unit responsible for repairing vehicles and equipment close to the front. The setting is Benghazi:–

The RAOC were on the job sorting out the spares that were of value to the army and had a huge stock neatly labelled and stacked in bins ready for removal to the base. Here was a God sent opportunity for the boys and did they avail themselves of it. It was a common thing for one to keep the Tommy in charge in conversation or otherwise keep him occupied while several others raided the store. ... It was all in a good cause and the unit was much better fitted up than most others.

Lloyd meanwhile was doing his best to remedy the deficiencies in the proper manner, but without immediate success. He made strong representations to AIF headquarters at Alexandria. He could draw little consolation from their reply that the shortage of motor spares would be relieved “by shipment on water from Australia”, nor from the action taken to provide signallers. The personnel of the divisional headquarters signals section were sent to Cyrenaica, but without signals equipment or motor transport or even cooking gear. Their war equipment reached Mersa Matruh by ship on or about 26th March! In the meantime, the best that could be done was to billet them in the rear, near Gazala. In the infantry the deficiency of mortars and anti-tank weapons was serious. Some shortages were made good with captured weapons but to what extent cannot be determined.

Although the plans of Cyrenaica Command prescribed only delaying actions at Marsa Brega as a prelude to giving battle on the plains before Antelat, Morshead believed that the El Agheila defile was the key to the defence. When he visited the 2/17th Battalion on 16th March, he expressed

the opinion (as the diarist of that unit noted) that the forward infantry were too far from the enemy. He was also very worried that means were, not available to prevent encirclement of his battalions, nor to move them if threatened with encirclement. In the meantime he had been ordered to hand over command in the forward area to the 2nd Armoured Division, but to leave Murray’s brigade at Marsa Brega and Beda Fomm under the armoured division’s command. He committed his thoughts to paper. In a memorandum written on 17th March and addressed to General Neame (but never delivered, for reasons which will appear) he reviewed the current situation and defence policy, and requested that the 20th Brigade should be relieved. The brigade’s armament, he pointed out, was far from complete. Against a mobile armoured enemy it would be practically immobile. If a German armoured formation advanced, the brigade’s presence in the forward area would only embarrass the 2nd Armoured Division by restricting its mobility and liberty of action. He submitted that it should be moved to the Benghazi-Barce area to execute work on defences already contemplated there. In addition he made pertinent comments on the defensive policy of Cyrenaica Command:–

The capture and retention of the defile on the Tripolitanian frontier ... I consider to be the basis of the successful defence of the present forward area. ... I understand that administrative considerations precluded the occupation of this defile in the first instance but I am of opinion that it may not be too late now to consider its execution. ...

Cyrenaica Command Operation Instruction No. 3 ... contemplates a defensive battle in the area between Agheila and the general line Ghemines–Soluch. I am of opinion that having regard to the force available the area in question is unsuitable for a defensive battle. The instruction proceeds ... to direct troops in the forward area to delay and harass the enemy without becoming seriously committed. For the reasons set out above 20 Aust Inf Bde cannot avoid being seriously committed if retained in the forward area.

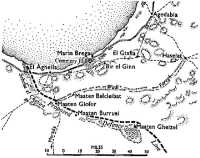

On the very day that Morshead wrote this memorandum he was unexpectedly summoned to meet General Dill and General Wavell, who had flown to Neame’s headquarters and with him were motoring down the coast road towards the frontier. As soon as Dill and Wavell met Morshead at the pre-arranged point near Beda Fomm, Wavell asked him for his appreciation. This he gave in the terms of the memorandum he had just composed, urging that the frontier defence should be based on the line of salt lakes from El Agheila to Maaten Gheizel and requesting that his unmotorised infantry should be withdrawn. Dill commented that he understood that the Marsa Brega position was well suited to the defence. Morshead replied that there were no more features in the surrounding country than on a billiard table. Wavell, turning to Neame, asked him to relieve the 20th Brigade in accordance with Morshead’s request. Neame said that it could be arranged in about a week. “In a week,” Morshead replied, “it cannot wait a week. Not a day can be lost11.” Back in Cairo next day, Dill telegraphed similar views to London. The outstanding

Morshead’s proposed defence line

fact, he said, was that between El Agheila and Benghazi the desert was so open and so suitable for armoured vehicles that, other things being equal, the stronger fleet would win; there were no infantry holding positions.

Wavell reported to the Chiefs of Staff (on 20th March) that an attack on a limited scale on the frontier seemed to be in preparation. He said that, if the advanced troops were driven from their present positions, it would be of no use to hold positions south of Benghazi. For administrative reasons, only a limited enemy advance was likely12.

Preparations were meanwhile well advanced for the assault on Giarabub, a desert oasis south of Salum where an Italian garrison, bypassed by the earlier British offensive, still held out, receiving supplies by air. The 18th Australian Brigade (Brigadier Wootten) was poised to deliver

the final blow. On his return from Cyrenaica Wavell authorised the attack to proceed. On 21st March Giarabub was captured13: the last offensive action the British would take in the desert for many days.

General Wavell’s departing instructions to General Neame had been to the effect that if the enemy attacked he was to fight a delaying action to the escarpment east of Benghazi without permitting his forces to become committed; he was even to evacuate Benghazi if the situation demanded, provided that he held on to the high ground on the escarpment to the east for as long as possible14.

Major-General M. D. Gambier-Parry, who had in February been recalled from command of the British troops in Crete to take charge of the 2nd Armoured Division, had already arrived in the forward area. At midday on 20th March he took over responsibility for the frontier troops from Morshead, who then moved his headquarters to the vicinity of El Abiar, an inland village on the plateau above Benghazi at the southern end of the Barce plain. The relief Morshead had requested was then arranged. The Support Group of the 2nd Armoured Division was to relieve the 20th Brigade. The 1st and 104th Regiments, Royal Horse Artillery, were allocated to the forward area while the 51st Field Regiment was allotted to the 9th Division. To conceal the change of dispositions from the enemy and safeguard the troops from air attack, the relief was to take place at night. Wireless silence, already imposed, would be continued.

The 1/Tower Hamlets Rifles was brought forward from Benghazi and on the harshly-cold moonless night of 22nd March the three Australian infantry battalions were taken back in draughty trucks to the plateau east of Benghazi. The convoy to lift the 2/13th Battalion overshot the meeting point, attracted enemy attention, was heavily attacked from the air, and got back to the battalion only just before dawn, which necessitated a dangerous but uneventful journey back by day. Simultaneously the 51st Field Regiment began moving up from Gazala to join the 9th Division and on 24th March the 104th RHA (less one battery already at Marsa Brega) moved forward from Tecnis to join the Support Group in the forward zone.

Meanwhile other movements were taking place to build up both divisions. The 9th Division’s engineers, who had been employed directly under Cyrenaica Command since mid-January, were placed under Morshead’s command and began rejoining the division: the 2/7th Field Company from the Agedabia area and the 2/13th from Maddalena. The 2/3rd Field Company remained temporarily in the forward zone. The 2/4th – from the 7th Division – was to move back to Mersa Matruh to join the 18th Brigade15. The headquarters and two battalions (2/24th and 2/48th) of the 26th Brigade, less one company of the 2/48th detached for garrison duty at Derna, were meanwhile encamped at AM el Gazala, while the third battalion (2/23rd) had remained at Tobruk. The 24th Brigade (two battalions only) arrived at Mersa Matruh from Palestine on 24th March. Brigadier A. H. L. Godfrey, who had succeeded Brigadier Plant to its command, joined it there. On the 26th it arrived in Tobruk. On that day Brigadier Tovell’s headquarters, the 2/24th Battalion (Major Tasker16, temporarily in command), and two companies of the 2/23rd Battalion (under Captain Spier17) left AM el Gazala to join the division in the forward area. Another company of the 2/23rd went to Derna, while the remaining company and the 2/48th Battalion were engaged in guarding (and evacuating) prisoners of war at the cages at El Adem and Tobruk. Meanwhile the 5th Royal Tank Regiment, the only battalion of the armoured brigade equipped with cruiser tanks, was dispatched from El Adem to the front, some 400 road-miles distant. “The latter of course should have been forward all the time,” wrote Lloyd on 26th March, “and may possibly not get up on time18.”

As the 5th Royal Tank Regiment moved up, its worn-out cruisers broke down at an alarming rate. The light tanks were in scarcely better shape. A technical officer reported that it was hardly worth while putting new engines into most of them, because the gear boxes and transmissions were so badly worn. The 3rd Hussars had now about 30 light tanks

but it was planned to withdraw some from this unit to equip one squadron of the 6th Royal Tank Regiment. The aim was to equip these two units as follows:

3rd Hussars – 2 squadrons of light tanks, one squadron of Italian M13’s.

6th Royal Tank Regiment – 1 squadron of light tanks, 2 squadrons of M13’s.

In the meantime one squadron was withdrawn from the 3rd Hussars to exchange its light tanks for M13’s, and as each squadron of the 6th Royal Tank Regiment received its equipment of Italian tanks it was placed under command of the 3rd Hussars. The process of equipment with captured tanks was not completed when the crisis arose and this dubious, improvised organisation was still in force.

By contrast, the Marmon Harrington armoured cars of the King’s Dragoon Guards, driven by their 30 horse-power Ford V8 engines, were mechanically reliable, though their springing was not equal to the strain of cross-desert running. But they were weakly armed and armoured. Their only weapons, for a crew of four, were one Bren light machine-gun and one Boyes anti-tank rifle (.55-inch) and one Vickers medium machine-gun mounted for anti-aircraft defence: their only protection, 6-mm armour. Such light protection left them almost defenceless against either low strafing aircraft or enemy armoured cars. Writing on 19th March of the German reconnaissance cars, the diarist of the King’s Dragoon Guards commented:–

These 8-wheeled armoured cars are faster, more heavily armed with a 37-mm gun and more heavily armoured than our armoured cars. Their cross-country performance is immeasurably superior to ours over rough-going.

The weakness of the British on the ground was matched in the air. This reflected a grave shortage of aircraft throughout the whole Middle East command. There was no ideal solution to the problem of aircraft distribution. In a global war it may be beyond human power to avoid seeing problems with a local perspective. The Middle East commanders-in-chief believed that their requirements had not been sufficiently regarded. While they were not in a position to assess their theatre’s needs against needs elsewhere, it may be questioned whether those who made the decisions were not unduly biased in favour of calls to meet the deficiencies closer to them.

The consequences of the provision made, whether right or wrong, were both an appalling shortage and an inferiority in quality. Gladiators and Blenheim fighters were matched against Italian CR.42’s, Hurricanes against Me.110’s. Headquarters Cyrenaica (Group Captain L. O. Brown) had only 30 aircraft: a squadron of Hurricanes at Bu Amud for the defence of Tobruk (No. 73 Squadron RAF), a squadron of Hurricanes (only four) and obsolescent Lysanders at Barce and Agedabia for army cooperation, and a bomber squadron at Maraua. The airfield at Agedabia, which alone was in close reach of the forward troops, could not safely be used at night, a fact soon discovered and exploited by the enemy, who flew many sorties at first and last light. The Germans alone had

90 Messerschmitt fighters and more than 80 bombers in Africa, with other aircraft in Sicily on call. The Italian Air Force was by no means negligible. On 22nd March Group Captain Brown, perturbed at the ground situation, issued warning orders to prepare for a rearward move.

The General Headquarters Middle East were of opinion that the enemy was likely to attempt a limited advance in the second week of April. General Neame felt that he had been given an impossible task. On 20th March he set out what, in his opinion, were the minimum reinforcements required (“within six weeks, or less if possible”) to enable him to discharge his responsibilities. He asked for two motor transport companies, additional signallers, a squadron of infantry tanks, a regiment of cruiser (medium) tanks, another motor battalion, additional artillery (field, anti-tank and anti-aircraft) and more air support, “also, if and when available a fully equipped and mobile division to replace 9 Aust Div who should garrison Tobruk and train there until fully equipped”. Major-General Arthur Smith, Wavers chief of staff, replied next day that before the end of the month or in early April a regiment and two batteries of field guns and the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade with two equipped battalions would be provided, to be followed by additional transport, but that no further reinforcements would be available in the immediate future. In reply Neame pointed out that the scheme of defence depended entirely on mobile operations by the 2nd Armoured Division which was not a mobile formation because it lacked transport, maintenance facilities and spare parts. Any large moves would involve a rapid wastage of tanks.

Neame was meanwhile doing everything possible to make the armour as mobile as possible. Since transport was short, a chain of dumps was being built up, from which it was hoped that the armour could be supplied at short range. Supplies were already available at Benghazi and Magrun and dumps were being established at Martuba, Tecnis, Msus and Mechili. This task was given first priority in the allotment of motor transport.

On 20th March, when the 2nd Armoured Division took over the forward area from the 9th Division, Neame issued a statement of policy for the defence of Cyrenaica based on the altered dispositions. It was not to be expected, he said, that the enemy would advance in force before the first week in April. If an advance were made, there were two possible routes the enemy armour might take: north, by the coast, to Benghazi; or eastwards across the desert south of the Jebel Achdar. The former was the more likely but the desert route could not be entirely ruled out; in any event, an advance by the desert would have to be accompanied by an advance through Benghazi and Derna to obtain use of the coast road for supply. The first task of the 2nd Armoured Division was to hold the Marsa Brega line and deny the area between there and the frontier to the enemy for as long as possible by active patrolling. If the enemy advanced in force, he would be delayed as much as possible; the 3rd Armoured Brigade would manoeuvre on his eastern flank “with the object of shepherding him into the plain between the sea and the escarpment running north from Antelat” and, if he continued towards Benghazi,

would keep him to the plain. The 9th Division would then deny the enemy access from the plain to the escarpment east and north of Benghazi “from inclusive Wadi Gattara to the sea at Tocra”, while the 2nd Armoured Division would prevent supplies from reaching him by road, block him if he attempted to move out of the plain to approach Barce or Derna in rear of the 9th Division, and protect the 9th Division’s left flank. Thus if the enemy could not be held at Marsa Brega, it was intended to allow him access, if need be, to Benghazi and the surrounding plain; but the escarpment was to be held so that he would be contained in the cul-de-sac formed by the convergence of the escarpment on the coast to the northeast of Benghazi. The armour meanwhile, pivoted on Antelat, would harry his flank and rear.

This was an evolution of Wilson’s scheme, but with the emphasis on evading rather than seeking an armoured engagement. The concept of “shepherding” the enemy armour had a wishful ring. Its postulate was ability to deploy armour in sufficient strength to compel a hostile force to conform: the paramount fact, in the situation as known, was that such strength was lacking. If the armour could not block the enemy at Marsa Brega, it could hardly prevent him from bypassing the Antelat position by the Trigh el Abd route, provided that he could muster the supply facilities to use it.

Whether, as Morshead proposed, the defile at El Agheila could have been effectively defended was not put to the test. Wavell wrote later that he had given orders for it to be occupied (to whom, or when the orders were given is not stated); but he added that it proved impossible to carry out the maintenance of the force there19. It was true that Neame’s whole force could not be maintained at El Agheila. Nor could less than the whole have done much to block a determined German thrust. But the problem was not whether a decisive engagement with the entire force committed should be sought there or elsewhere; it was whether the attempt to establish an effective if only temporary block should be undertaken at El Agheila or Marsa Brega. El Agheila fort is 25 miles south-west of Marsa Brega; the defile through the salt lakes (so narrow that only a small part of the force could have been stationed there) another 15 miles: 40 miles in total. The distance from Tobruk, the supply port, was some 450 miles by the coast road. Was this extension of the supply route critical? There were other factors: wastage through greater exposure to air attack; the difficulty, if the 2nd Armoured Division’s supply line were to be thus extended, of building up dumps in rear against a possible withdrawal; a greater danger that the escape route might be closed. In the outcome no force of consequence was placed at El Agheila. The armour was tied to supply dumps farther back. The enemy came through the front gate of Cyrenaica while the frontier watch-dog was chained at Marsa Brega.

Nevertheless Neame and Gambier-Parry took steps to establish a permanent outpost at El Agheila. The force operating forward from Marsa Brega consisted of the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards (stationed two

miles east of Marsa Brega with a squadron to the south at Bir el Ginn), with under command, three guns of the 2/3rd Australian Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, three guns of the 37th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment and two guns of the 16th Australian Infantry Anti-Tank Company (Lieutenant Simpson20). They kept a northern patrol in the El Agheila area and a southern patrol near Maaten Giofer, each comprising one armoured car and one gun of the anti-tank company. Larger patrols were from time to time organised for specific tasks. On 20th March Gambier-Parry arranged for a platoon of the 1/Tower Hamlets Rifles (then ensconced in the Marsa Brega position) to guard El Agheila fort by night. Lieutenant Cope21, whose platoon had been selected, reconnoitred the area and recommended that the patrol should be stationed south of the fort, to keep watch on the Giofer track and prevent the enemy’s approach from that direction. Cope took his platoon out to this position on the 21st. A plan was then worked out to establish an ambush on ground west of the fort, close to the defile through the salt lake; two troops of the King’s Dragoon Guards were to cooperate with Cope for the operation, which was set down for 24th March. Accordingly on 22nd March Major Lindsay’s “C” Squadron of the Dragoons relieved Cope’s platoon, which, however, left one section to guard the southern approach.

On 23rd March Lieutenant Weaver22 of the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards patrolling near Giofer with two armoured cars and an anti-tank gun of the 16th Anti-Tank Company manned by Corporal Kennedy’s23 section surprised at breakfast a small German force which was on the way to Marada oasis. Two or three armoured cars, two or three tanks, four field guns and from fifteen to twenty motor vehicles were seen. The British patrol was at first not sure whether this force was friend or enemy, but when Kennedy fired a round over their heads, the reaction dispelled the uncertainty. The anti-tank gunners then opened up, firing at about 1,000 yards’ range, and knocked out two vehicles in about a minute while Weaver’s two armoured cars parted and attacked the enemy at speed from either side. The Germans mounted their vehicles and made off. The Australian gunners, continuing to engage, knocked out a third vehicle at an extreme range of about 2,500 yards although the sights of their 2-pounder gun were calibrated to only 1,800 yards. Some enemy armoured cars later turned and stalked the British patrol; but Weaver succeeded in evading them and remained in the area until the afternoon.

–:–

The Axis forces also had designs on El Agheila but were planning a larger operation than the British. The German staff now knew that “green” formations had replaced the British forces that had routed Graziani’s army. From the recent imposition of wireless silence and other

signs they had surmised that the British were withdrawing part of their force from the forward area. On 18th March Rommel left Africa by air to report to the German High Command; but before leaving he ordered that plans should be made for an operation to seize the eastern outlet of the El Agheila defile on 24th March. On the 19th he saw Hitler, General Brauchitsch and the Chief of the General Staff, General Halder, at Hitler’s headquarters. He told Hitler that the British were thinking defensively and concentrating their armour near Benghazi, intending to hold the Jebel Achdar area. He asked for reinforcements, contending that it would not be possible to bypass the hump of Cyrenaica by attacking along the chord of the arc in the direction of Tobruk without first defeating the British in the Jebel Achdar. Hitler and Brauchitsch replied that the 15th Armoured Division, due to be dispatched in May, was the only reinforcement Rommel could expect. When it arrived he was to make a reconnaissance in force to Marsa Brega, attack the British around Agedabia and possibly take Benghazi; but he was to adopt a cautious policy in the meantime. The German High Command had its eyes on other commitments: Greece and Crete. And Russia. Rommel later recorded that he “pointed out that we could not just take Benghazi, but would have to occupy the whole of Cyrenaica, as the Benghazi area could not be held by itself.”

Restless and impetuous though he was, there is no evidence that when Rommel flew back to Africa with instructions to bide his time, he contemplated undertaking instead an immediate general offensive or that he even thought he was strong enough to do more than exploit a local disparity of strength. In fact he was using dummy tanks to create an illusion in his opponents’ minds of a strength that he lacked. (Neame was doing likewise.) It is hardly likely that Rommel assumed that an enemy which, during his absence in Europe, had attacked and taken Giarabub, would not stand and fight. The German Africa Corps’ estimate of the British battle order in the Marsa Brega-Agedabia area was of a force not materially differing in strength from the German component of Rommel’s force. The estimate, though inaccurate in detail24, was in summation a reasonably close approximation to its actual strength, though the British formations had weaknesses not ascertainable until they were engaged.

But Rommel was not one to stand idly by while waiting for the 15th Armoured Division to arrive. His planning had heretofore been complicated by two divergent aims: attacking the British position near Marsa Brega, and preparing an operation to relieve the Giarabub garrison. The fall of Giarabub had left him free to concentrate on the frontier operations. The 5th Armoured Regiment’s tanks had arrived: 90 medium and 45 light tanks, all in the forward area. Enough petrol was held for an advance of about 400 miles. On his return to Africa on 23rd March, Rommel immediately ordered the attack on El Agheila to proceed on the following day. Its capture would both provide him with a forward

base for a later general offensive and alleviate his immediate water-supply problems. The task was assigned to the 3rd Reconnaissance Unit, supported by artillery and machine-gun detachments and a company of tanks.

The 24th March, it will be remembered, was the day on which the British command had planned that Cope’s platoon should occupy an ambush position west of El Agheila. On the 23rd, the RAF discovered that the enemy had brought into use a new landing ground in the forward area, at Bir el Merduma. The pilots also reported having seen a large enemy force moving eastward near El Agheila, including armoured cars, 20 medium tanks (reported as Italian) and artillery. That night Lieutenant Williams’ troop of “C” Squadron 1st King’s Dragoon Guards and Cope’s platoon, with one of Simpson’s anti-tank guns, spent the night 1,000 yards west of the fort. The plan was that Cope should report the fort clear of the enemy at 6 a.m. and then push a section forward. Meanwhile Lieutenant Whetherly’s25 troop (of “A” Squadron, King’s Dragoon Guards, which was to relieve “C” Squadron that day) would patrol to the intersection of tracks 12 miles to the south and report it clear. When Cope’s report was received, Williams’ patrol was to move up to the ground secured by Cope’s section. A troop of “B/O” Battery of the 1st Royal Horse Artillery was to give support.

Accompanied by Williams’ patrol, Cope approached El Agheila fort at first light in a truck, dismounted and went forward towards the fort on foot. Suddenly he saw that it was occupied by the enemy. “He shot two and ran for his life, reaching his truck to get away in a hail of bullets,” wrote “C” Squadron’s diarist later. Guns from the fort then opened fire on Williams, who had just observed tanks approaching from the south. Williams withdrew his car behind a mound and brought the anti-tank gun into action. An enemy armoured car topped the rise: both cars and the gun opened fire simultaneously. The enemy car was hit and put out of action; but the Australian gunner was killed and the corporal wounded.

Williams withdrew his patrol to squadron headquarters, obtained another anti-tank gun, and moved out to a position covering the squadron. Whetherly had meanwhile reported 10 enemy tanks and 20 motor vehicles just east of the fort. Soon afterwards the Italian flag was hoisted there. And that evening the King’s Dragoon Guards’ squadrons retired to the Marsa Brega area. The gateway between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica was in Rommel’s possession. “This rather altered arrangements,” commented the diarist of the 1st RHA.

In the occupation of this most important position, the only losses suffered by the enemy were those inflicted by Cope himself, the armoured car, and the anti-tank gunners, and damage caused to two tanks that ran on to mines.

The enemy exploited no farther forward for several days; but the landing ground at El Agheila was brought into immediate use. The Marsa

Brega position, which had now become the British foremost line of defence, had several weaknesses. It was overlooked by a feature known as Cemetery Hill, which was beyond the salt lakes that gave frontal protection to the line. Rolling sand dunes near the shore provided a covered approach to its right flank while the left flank could be encircled not only immediately to the south of the salt lakes but also by a wider turning movement in the desert south of the Wadi Faregh, where the going was good for vehicles. The front, which was eight miles wide, was to be held by one battalion and one company of motorised infantry. The minefield in front was now primed and the armoured cars of the King’s Dragoon Guards came in behind it. The armoured brigade guarded the left flank at the edge of the salt lakes while, farther south, a squadron of the Dragoon Guards established a standing patrol at Maaten Gheizel to watch for a deep turning movement from Marada.

For a few days there was no contact with the enemy. There were frequent “khamsins” – dust-charged windstorms that swept off the Sahara, blotted out both sky and sun, and sometimes reduced visibility to a few feet. A khamsin raged on the 26th, on the 27th the wind blew harder; on the 28th it subsided. The first ground contact with the enemy after the loss of the frontier occurred on the 29th at Maaten Belcleibat, on the Wadi Faregh outlet from El Agheila, where Lieutenant C. F. S. Taylor’s troop of the Dragoon Guards encountered two German eight-wheeled armoured cars. The stronger German vehicles gave pursuit and in the running fight one of Taylor’s cars was knocked out. Enemy tanks were also seen that day at El Agheila and the German Air Force’s strafing and bombing were severe. A dive-bombing attack near Soluch completely destroyed a petrol train – a serious loss.

–:–

While at El Agheila, Marsa Brega and Beda Fomm the khamsin had reduced both desert armies to immobility, events of some importance had taken place in Europe. On 25th March, the Government of Yugoslavia had signed the Tripartite Pact; but on the 27th that government was overthrown and another, favourable to the Allies, installed under the youthful King Peter. The German Government at once ordered a simultaneous invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece. On the same day, in Eritrea, General W. Platt’s forces captured the key Italian port of Keren, and in Abyssinia, General A. G. Cunningham’s army occupied Harar – except for Addis Ababa the largest town in Abyssinia – so bringing closer the day when Indian divisions could be transferred from that front to the desert. The reoccupation of British Somaliland had been completed three days before. On the 28th, Vice-Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham’s battle fleet, with Royal Air Force support from Greece, intercepted an Italian fleet near Cape Matapan, sinking four cruisers and three destroyers and damaging other ships. The victory had a powerful moral effect, which probably contributed to the later failure of the Italian Navy to intervene effectively with surface vessels in the evacuations from Greece and Crete.

Wavell’s written instructions confirming his oral orders to Neame were dispatched from Cairo by air on the 20th but did not reach Neame until the 26th. Their underlying concept was that Neame should strive to keep his force intact rather than treat any ground as vital. “The safeguarding of your forces from a serious reverse,” he wrote in the first paragraph, “and the infliction of losses and ultimate defeat on the enemy, are of much greater importance than the retention of ground. The reoccupation of Benghazi by the enemy, though it would have considerable propaganda and prestige value, would be of little military importance, and it is certainly not worthwhile risking defeat to retain it.” He directed Neame to consider whether the position held on the frontier might be improved by advancing to the defile formed by the salt marshes west of El Agheila. Whatever the decision, Neame was to retain there only mobile covering forces, which must be able to manoeuvre rapidly in retreat if necessary. If a withdrawal became necessary, a small mobile force of infantry and guns should withdraw down the road to Benghazi, delaying the enemy and inflicting loss on him without becoming seriously engaged, while the armoured troops were to manoeuvre on his flank, taking up a position near Antelat so as to be able to keep on his flank whichever way he went. Neame was to consider whether a defensive position could be found immediately south of Benghazi; if not, he was to hold the defiles through which the railway and two roads leading east from Benghazi mounted the escarpment to the first plateau and the Barce plain.

The salient feature of these instructions was that the first phase of the defence should be an action of manoeuvre, harassment and quick disengagement, a role in which the 2nd Armoured Division with its obsolescent tanks was still ill-starred. Wavell afterwards wrote that he did not become aware of the dangerously poor mechanical state of these tanks till a few days before the enemy attack, which is comprehensible in the light of the many responsibilities he was shouldering26. Nevertheless he had been forewarned when the tanks had first arrived in Egypt.

When Churchill learnt that the Germans had taken El Agheila, he asked Wavell for an appreciation of the situation. Churchill’s telegram expressed concern at the “rapid German advance to El Agheila”:–

It is their habit to push on whenever they are not resisted. I presume you are only waiting for the tortoise to stick his head out far enough before chopping it off. It seems extremely important to give them an early taste of our quality27.

Wavell replied on the 27th that there was no evidence yet that there were many Germans at El Agheila. The force was probably mainly Italian with a small stiffening of Germans. Wavell admitted to having taken a considerable risk to provide the maximum force for Greece, with the result that he was weak in Cyrenaica; moreover no reinforcements of armoured troops, which were his chief need, were available. The next month or two would be anxious; but the enemy had a difficult problem. He was sure that their numbers had been exaggerated.

Meanwhile, on the plateau east of Benghazi, the 9th Australian Division was making ready to defend the escarpment and its passes and to deny the enemy access from the plain, should he choose to advance that way. From Benghazi two roads led up the first escarpment, climbing through passes at Er Regima and near Tocra to the intermediate plateau. Two roads also mounted the second escarpment through passes near Barce and near Maddalena. Both roads proceeded to traverse most of the tableland by winding but approximately parallel routes, then converged, and from the junction one trunk road led on to Giovanni Berta. Thence the main coast road proceeded to the port of Derna, descending the escarpment to the harbour and mounting it again just beyond by two steep and tortuous passes. From the top of the eastern pass it led south-east to Ain el Gazala and to Tobruk. But the Derna passes could be bypassed by a rough track that went out from Giovanni Berta into the desert and rejoined the main road near Martuba.

On 24th March Morshead’s headquarters issued written orders defining the division’s task as being to hold the escarpment from the sea at Tocra to the Wadi Gattara and setting out the method by which this was to be done. The escarpment was to be defended and the passes blocked. The right sector was given to the 26th Brigade with the task of blocking the road pass near Tocra; the left sector to the 20th Brigade with the main task of blocking the road and railway at the Er Regima pass. Each brigade was to be given one composite battery of the 51st Field Regiment, comprising six 18-pounders and six 4.5-inch howitzers, and nine 47-mm Italian anti-tank guns “to be transported and fought portee”. The 2/13th Field Company (less one section) was allotted to the 26th Brigade, the 2/7th (less one section) to the 20th.

On the 26th, Brigadier Murray made an aerial reconnaissance of the escarpment with his three battalion commanders, after which he allotted defence sectors to his battalions: to the 2/17th the right flank north from Er Regima, which consisted of about 20 miles of steep escarpment, ascended here and there by rough foot-tracks; to the 2/13th (which was still without one company, on security duty at Benghazi), the Er Regima pass and, on the left flank, the Wadi Gattara; to the 2/15th Battalion a defensive position near El Abiar, where an inland track led into the rear of the area occupied by divisional headquarters. Next day the three battalions took up these positions.

On the 28th Brigadier Tovell’s headquarters, the 2/24th Battalion and two companies of the 2/23rd Battalion arrived from Gazala. Tovell’s headquarters went to a position near Baracca, west of Barce, and the 2/24th Battalion to the Tocra area. The two companies of the 2/23rd were directed to Barce, where Captain Spier was installed as Town Major. As soon as the 2/24th arrived Lieutenant Serle28 and the Intelligence section of the 2/24th Battalion reconnoitred the escarpment from Tocra to Tolmeta and established that it was not feasible for vehicles to ascend

the escarpment except by three passes: one at Tolmeta, one at Tocra, and a central one between these two. The battalion was therefore disposed with three companies forward, one covering each pass, and the fourth company stationed in reserve near battalion headquarters, just behind the Tocra pass. While the 2/24th was getting ready to block the northern passes, the engineers were putting down a field of about 700 mines in the Er Regima pass and laying charges beneath the road and railway.

The escarpment line, east of Benghazi, which had a total length of 62 miles, was thus held by three battalions, with a fourth battalion disposed on the southern flank; there were no reserves at all within close call.

On 26th March, Neame’s headquarters issued a most secret instruction to Morshead informing him what positions were to be occupied if it should become necessary to withdraw from the lower escarpment. In that event the intermediate plateau was to be yielded but the defence was to be conducted from the tableland above to a plan aimed at blocking the enemy advance at two defiles. Of the two roads leading eastward from Barce and across the tableland one was to be denied to the enemy by holding the scarp and pass east of Barce; the other (northern) route, however, which was the main road, was to be blocked, not at the escarpment line but some 55 miles farther east, at the Wadi Cuff – the “valley of caves” – at a point where the road was carved into a steep hillside and crossed the watershed through a steep and wooded defile. This plan involved holding two defensive positions which, as the instruction pointed out, were tactically disconnected; it suffered from the “textbook” defect that the line of communications ran parallel to the front. The instruction also provided that if a further withdrawal became necessary, the 9th Division would fight the enemy on the general line of the Wadi Derna.

Cyrenaica Command also ordered the creation of a “military desert” in front of the line to be held by the 9th Division. At Benghazi, Magrun, Agedabia, and Msus and in the surrounding country, all military stores, wells and installations were to be prepared for demolition. Both English and Australian engineers were busily engaged on the work.

Morshead’s forward units were now 100 miles from the armoured division. His complete lack of motorised troops for reconnaissance was a continual worry, and he asked to be given the 6th Division’s cavalry regiment – a request that could not be granted. Moreover his only troop-carrying transport was being employed away from his control on the establishment of dumps at Msus and Tecnis. On the 27th he made representations to General Neame about these deficiencies. Neame informed him that two motor battalions of the 7th Armoured Division’s Support Group were soon to arrive in Cyrenaica and that the first to come would be allotted to the 9th Division.

Morshead also pressed Neame to arrange for the early evacuation of all civilians, both Arabs and Italian colonists, from the region the 9th Division was preparing for defence. There were political difficulties in

agreeing to this. After consultation with his senior political officer, Neame adopted a compromise solution of declaring certain limited areas to be prohibited zones.

On 28th March, Morshead and Lloyd inspected the left (southern) flank of the division’s area and, finding the approaches open, decided to place the 1/Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (less one company with the 2nd Armoured Division) and the 24th Anti-Tank Company immediately at Bir es Sultan, astride the track leading in from the south. On the 29th it became clear that the enemy knew something of the new positions held, for the 2/13th Battalion was attacked by aircraft; five bombs were dropped on the battalion. Also on the 29th the cutting and stealing of signal wires by Arabs seriously interfered with the battalion’s communications. Morshead saw the Mukhtar of the adjoining native village next day and charged him with the responsibility to have the pilfering stopped. It is doubtful whether the motive had been sabotage. The leaders of the Senussi sect, to which most Libyan Arabs belonged, were openly allied to Britain. They had raised a Libyan force of several battalions which, fighting under its own flag, was serving with the British. Libyan units were being employed at Giarabub, Tobruk and elsewhere29.

The division’s two most serious and embarrassing shortages – of signals equipment and of motor transport – had not been in any way relieved. The headquarters signals section was still at Gazala. So serious was the deficiency of signals equipment that to a large extent use had to be made of the civilian telephone lines, which passed through the civilian-manned exchange at Benghazi. As for motor transport, the shortage made it impossible for Morshead to employ more than five of his eight battalions and even restricted the movement of those. The 2/48th Battalion was waiting at Gazala until vehicles could be found to move it up to the 26th Brigade’s defence-sector. Because the division had been issued with first-line transport for only five battalions, the 24th Brigade was grounded at Tobruk30.

–:–

The behaviour of a garrison force towards the civilian population is commonly a matter of concern for force commanders and of worry for their staffs dealing with civil affairs, who have to endure the criticism, complaints and resulting from each instance of misbehaviour. It is only too easy to identify the character of whole units and formations with that of a few offenders and to project anger on their commanders and officers.

On 31st March Neame wrote Morshead a long letter about the conduct of Australian soldiers in towns. Alleged disorderly conduct by Australians

was a long-standing grievance of Cyrenaica Command, which had been nurtured since the beginning of the occupation. After the capture of Derna, General R. N. O’Connor had written to General Mackay charging Australian soldiers with looting and the commission of serious civil offences. The allegations were discussed earlier in this series, where it was pointed out that although some looting by small parties had occurred the town had already been looted on three separate occasions before the Australians reached it and on the other hand had been effectively policed immediately after their entry31. In subsequent months Cyrenaica Command made further allegations of misconduct by Australian troops to Mackay’s headquarters and, in turn, to Morshead’s, of which Neame’s letter was the culmination. The discipline of Australian troops being a matter of internal administration, Australian commanders were responsible for its enforcement to the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the AIF not to the local British commander32.

The only reasonably effective way of controlling soldiers in towns when not in formed bodies is to employ military police; but Morshead had none. When Neame wrote his letter, the division’s provost company was in Tobruk. Transport to bring it forward had been requested but not provided. In the course of the letter, Neame said:–

I now have to bring to your notice the fact that since I was forced to withdraw the Tower Hamlets picquets at Benghazi for urgent operational reasons, parties of Australians have entered Benghazi presumably without leave, at least I hope so, and cases of Australian drunkenness have again occurred there.

Since 20 Inf Bde of 9 Aust Div was moved to Regima area, numerous disgraceful incidents have occurred in Barce, drunkenness, resisting military police, shooting in the streets, breaking into officers’ messes and threatening and shooting at officers’ mess servants, even a drunken Australian soldier has come into my own headquarters and disturbed my staff. This state of affairs reached a climax yesterday Sunday 30th March, when the streets were hardly safe or fit to move in; officers of my Staff were involved in endeavouring to support the action of the military police. ...

As I have told you in a previous letter on this subject, I consider it disgraceful that I and my Staff should have our attention and time absorbed by these disciplinary questions at a time when we have to consider fighting the Germans and Italians. ...

I am at a loss for words to express my contempt for those who call themselves soldiers who behave thus. They have not learnt the elements of soldiering among the most important of which are discipline, obedience of orders, and soberness. And their officers are equally to blame, as they show themselves incapable of commanding their men if they cannot enforce these things.

I did not mention it the other day, but I must tell you now that the C.I.G.S. and C. in C. when visiting me here were accosted in the street by a drunken Australian soldier. I myself have had the same experience in Barce. ...

Your Division will never be a useful instrument of war unless and until you can enforce discipline. ... And all the preparations of the Higher Command may be rendered useless by the acts of an undisciplined mob behind the front.

I must hold you responsible for the discipline of all Australian troops in this Command, as I have no jurisdiction in the matter.

Unless an improvement can be rapidly achieved, I shall be forced to report the whole case to G.H.Q. for transmission to the Commander AIF

These were strong words to use to Morshead. Angered though he was by the threat that an adverse report would be made to Blamey and by the manner in which Neame presumed to lecture him on the importance of military discipline, Morshead’s main objection to the letter was that Neame, by the tone in which he wrote and the use of such phrases as “Australian drunkenness” and “undisciplined mob” had displayed a palpably anti-Australian attitude and had gone beyond the justifiable censuring of specific cases of misbehaviour to impugn generally, in immoderate, contemptuous words, the quality, and military virtue of the officers and men whom Morshead commanded. “Why don’t British MPs arrest these men? We must have identification and charges,” Morshead wrote in his diary, to which he confided his thoughts as follows:–

Without in any way condoning any offences I cannot help feeling that it is the same old story of giving a dog a bad name. And we rather sense the cold shoulder in Barce. ...

Take the case of the Australian pte who entered the officers’ mess at Barce. He was accompanied by two British ptes. What has happened to them?

That day Morshead had asked to see Neame’s senior administrative officer on another matter. Neame himself came and Morshead took the opportunity to protest. He told Neame that he objected to his anti-Australian attitude, that the same attitude had permeated to Neame’s staff, and that he was forwarding the letter to General Blamey and considering forwarding it to Australia, if not to Wavell33.

Nevertheless Morshead caused a message to be sent immediately to all formations and units under his command placing all towns, villages and native camps out of bounds. Next day he called his senior commanders to a conference on discipline, after which a staff instruction was issued repeating earlier orders, providing a system of passes for men required to proceed to Benghazi or Barce on duty and stressing the need to restore discipline by firmness and adequate punishment.

If some censure was on this occasion deserved, it was a lapse from a high standard previously set and afterwards maintained. The formations and units then in Cyrenaica had come there with a record of good behaviour in towns and on leave.

Neame, writing after the war in his autobiography, was able to make a different assessment of the 9th Division, its commander, its officers and its men, which one may willingly suppose was as sincere as it was generous. After mentioning that the division was only half-trained and half-equipped, he added:–

Let me say at once that the 9th Australian Division fought magnificently, and was splendidly led by Morshead and his Brigadiers; and well served by its staff. I could have had no better fighting troops under me in the fighting near Benghazi34.

General Rommel meanwhile was less concerned with what was happening in the 9th Division’s area than with what the 2nd Armoured Division

was doing immediately in front of El Agheila, at Marsa Brega. “It was with some misgivings,” he wrote later, “that we watched their activities, because if they had once been allowed time to build up, wire and mine these naturally strong positions, they would then have possessed the counterpart of our position at Mugtaa35, which was difficult either to assault or to outflank from the south. ... I was therefore faced with the choice of either waiting for the rest of my troops to arrive at the end of May – which would have given the British time to construct such strong defences that it would have been very difficult for our attack to achieve the desired result – or of going ahead with our existing small forces to attack and take the Marsa Brega position in its present undeveloped state. I decided for the latter36.” Again, the problem of water-supply was a second but important reason for attacking. “An operation against Marsa Brega,” he wrote, “would give us access to plentiful water-bearing land.” In the meantime the German Army command suggested an operation to capture Gialo oasis. This was planned as an airborne operation by a reinforced machine-gun platoon.

Preparations for an attack on Marsa Brega were put in hand. The 8th Machine Gun Battalion was brought forward to El Agheila so that the 3rd Reconnaissance Unit would be freed for preliminary reconnaissance. On 28th March the 5th Light Division (with the I/75th Artillery Regiment) reached the area round En Nofilia, and on the 30th Rommel gave orders to its commander, General Streich, to take Marsa Brega on the next day. German reconnaissance had established that the salt marsh (on either side of the main road) near the British position was not passable but that there was a track through high dunes about six miles south of the road by which the defended area might be cut off. The plan was to advance in two columns. On the right, a small column consisting of the 2nd Machine Gun Battalion and an anti-tank battalion was to advance by the track while the main force, consisting of the 5th Armoured Regiment, the 8th Machine Gun Battalion and the 3rd Reconnaissance

Unit, with artillery and anti-tank support, would advance along both sides of the main road. Two days later an attack on Gialo was to take place37.

–:–

–:–

On perusing Wavell’s tardily-received instructions for the conduct of the defence, Neame concluded that they required no change in his own orders. In general, the written instruction was but an elaboration of the instructions Wavell had given to him orally. One elaboration was a direction that a small force of infantry and guns should hinder and delay any enemy advance by the coast to Benghazi. If this became necessary, Neame would be hard put to it to find an infantry force of sufficient strength to be effective; the entire Support Group, even if intact, would be small for the task. On 30th March Cyrenaica Command issued an

operation instruction defining the roles of formations and laying down code words for the evacuation of Benghazi and the demolition of stores and installations there. The instruction was concerned with what to do if the enemy advanced but stated that there were no signs that, having taken El Agheila, he was preparing to advance farther, nor was there conclusive evidence that he intended to take the offensive on a large scale in the near future or would be in a position to do so. An Intelligence summary issued by G.H.Q. had been separately circulated in which the German force in Libya had been estimated as a divisional headquarters, a reconnaissance unit, a lorried infantry brigade, a machine-gun battalion and possibly two tank battalions. Neame was careful to impress on his commanders and forward units that, while they were to execute a withdrawal rather than become committed, they were not to withdraw unless forced to do so: orders taxing forward commanders with perhaps too fine a discrimination.

Cyrenaica Command had received several reinforcements since the fall of Agheila. The largest was the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade, now at El Adem and patrolling deeply – to Mechili (where the dumps were guarded by a company of Senussi), Bir Tengeder, and Ben Gania along the Trigh el Abd. The brigade had three motor battalions, which were equipped with a full complement of vehicles but armed only with light weapons. Wavell warned Neame of the danger of exposing them to combat with armoured troops. “A” Squadron of the Long Range Desert Group was another reinforcement. It had left Cairo on the 24th and arrived at Barce on the 30th, where its role was to watch for enemy movement eastwards, on the desert flank towards Gialo and Giarabub. Neame ordered it to establish its headquarters at Marada. Accordingly the commander, Major Mitford38, sent out a patrol on the next day (31st) to make a complete circuit of the oasis as a preliminary reconnaissance.

Meanwhile, as Rommel had observed, the position at Marsa Brega was being strengthened. On 26th March a company of the 1/Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (machine-gun battalion) was brought forward from Benghazi and placed under the command of the 1/Tower Hamlets Rifles (a platoon being placed in support of each forward company). On the 28th the 1st Company of the French Motor Battalion was moved forward to the left flank of the Tower Hamlets, where it replaced “A” Squadron of the King’s Dragoon Guards, who were now freed for their normal operational role of reconnaissance. On the 29th “J” Battery of the 3rd Royal Horse Artillery arrived, providing some solid, if rather scanty, close gun-defence against tanks at Marsa Brega.

The 5th Royal Tank Regiment had arrived in the forward area; but owing to severe losses from mechanical breakdown on the way, there remained of its full complement of 52 cruisers, only some two dozen, all of which had covered at least 15,000 miles (some 20,000) and reached the end of their life expectancy. The process of equipping squadrons of the other two tank units with captured tanks was still proceeding.

The Italian M13’s were proving most unsatisfactory; the engines boiled every 10 or 12 miles, which restricted their daily radius of movement to 48 miles. The division’s total strength in serviceable and semi-serviceable tanks of all kinds was 68. Moreover, as now constituted and equipped, it was a completely unexercised formation. This was particularly serious with respect to its intercommunications, for almost all of its original signallers had been given to the portion of the division sent to Greece.

By 30th March the newly-arrived units had settled down. On the right, the Support Group (Brigadier Latham39) held the eight miles of front within the Marsa Brega salt marshes with the Tower Hamlets (less one company) and the 1st Company of the French Motor Battalion, and with the 104th RHA under command. An infantry outpost (one company of the Tower Hamlets with two sections of machine-guns) was sited on Cemetery Hill, to the front, covering an artillery observation post. One company (“D”) of the Tower Hamlets was preparing a position in rear, about a mile north of Agedabia. On the left flank, the ground for about five miles south of the road was inaccessible to tanks Beyond this, the 3rd Armoured Brigade (Brigadier Rimington) was echeloned to the north-east. Foremost were the 3rd Hussars (26 British light tanks and Italian M13’s) organised into four squadrons (two manned by 3rd Hussars and two by 6th Royal Tanks personnel) with whom was Lieutenant Weir’s40 platoon of the 16th Australian Anti-Tank Company. Behind was the 5th Royal Tank Regiment. With each regiment was a battery of the 1st RHA and two light anti-aircraft guns. The 6th Royal Tank Regiment was to the rear at Beda Fomm with one squadron of 6th Royal Tank Regiment personnel already manning M13 tanks and one squadron of 3rd Hussars personnel in the act of taking over their complement.

In front of the armour, patrols of armoured cars from the King’s Dragoon Guards kept watch. “A” Squadron (from behind the infantry positions at Marsa Brega) sent forward two patrols daily to the El Agheila area. Another squadron guarded the left flank at the Wadi Faregh, keeping a patrol farther out at Maaten Gheizel at the end of the chain of salt lakes.

Major-General Gambier-Parry’s orders to the armoured division were to the effect that if attacked in force it should withdraw on the axis Agedabia-Antelat-Msus41. In brief, a firm attempt to bar entry into Cyrenaica was not to be made, but the armoured brigade and the Support Group were to conform in a delaying withdrawal to a position behind Agedabia; separate withdrawal axes were prescribed for each formation and intermediate lines of resistance laid down, each with its allotted code name

On the morning of 31st March, the northern El Agheila patrol of

the King’s Dragoon Guards was under command of Lieutenant Budden42, the southern of Lieutenant Whetherly. The latter patrol was to be accompanied by Major Pritchett’s43 squadron of the 5th Royal Tank Regiment with its four cruiser tanks – all that remained to the squadron after the rigours of the march from El Adem. At Marsa Brega, the Support Group’s program for the day was one of offensive patrolling forward of the marsh, with both infantry and carrier patrols.

Pritchett and Whetherly intended to set an ambush near Maaten Giofer for some enemy tanks seen on the previous day. At first light, near the road north of Giofer, they suddenly encountered a group of German tanks. There was a brisk engagement, in which one of Pritchett’s cruisers suffered damage; but more German tanks, going down this road, threatened to encircle the British patrol, and it was seen that they were followed by many lorries and several guns. Pritchett and Whetherly withdrew – with the German tanks in pursuit; there was another short engagement near the salt marsh east of El Agheila; then the German tanks turned south along the marsh, leaving the British patrol to return unmolested. Budden, however, remained out near El Agheila, among the dunes, whence he reported to headquarters the eastward movement of a huge German force rolling past him towards Marsa Brega.

It was at 7.45 a.m. that the infantry near Marsa Brega first saw the enemy. The outpost at Cemetery Hill observed, about 5,000 yards to the south-west, 5 enemy tanks and 2 trucks, from which 20 to 30 men dismounted. Budden’s reports, and others from the pilots of scouting aircraft – who had seen 200 tanks and armoured cars, with swastika markings, moving east about seven miles from the British positions – left no doubt that the German advance in force, predicted by Neame’s headquarters for the first week in April, had already begun.

At 9 o’clock, outposts of the 1/Tower Hamlets Rifles (Lieut-Colonel E. A. Shipton) saw this force cautiously drawing near. After much obvious reconnoitring, groups of tanks, armoured cars and lorries were seen to deploy; some were observed at a mosque to the front, others farther north and again a small group about six miles to the south. About 9.30 a.m. the enemy began to advance and the British infantry patrols came in, but the carrier scout platoon stayed out in front, keeping watch. About 10 o’clock the enemy brought up a gun, covered by four tanks, to a ridge some four miles to the west, pressed forward and drove the scout platoon back to the outpost at Cemetery Hill; the company there was then withdrawn with the exception of the machine-gunners and one platoon of riflemen. The carrier platoon remained to give them support. The gunners of the 339th Battery, directed by the observation post at Cemetery Hill, went into action: they were to have a busy day.

Half an hour later, enemy infantry preceded by two motor-cycle combinations and ten tanks began to close on Cemetery Hill from the south. The outpost called on the gunners for defensive fire, which the 104th

RHA put down, and the infantrymen and machine-gunners came back behind the forward defences to a position on a ridge astride the road. The scout platoon, however, remained with its carriers behind the hill and later confounded the enemy by engaging his approaching tanks at a range of 300 yards. It was not until 11.30 a.m. that the Germans occupied Cemetery Hill; by that time they had worked round the flank of the position. The scout platoon then withdrew. At midday, as the enemy showed signs of renewing the advance, the Tower Hamlets closed the road-block. Eight-wheeled armoured cars then approached and fired on the forward infantry, but were engaged and driven off by a troop of the 104th RHA whose observation post was under heavy enemy fire.

The main column of Rommel’s thrust seemed to have been brought to a halt; the British armour waited unmolested on the left flank, while to the far south, on the Wadi Faregh, “C” Squadron of the King’s Dragoon Guards reported no enemy seen. (Rommel’s southern column had been delayed by “bad going”; they were not seen all day and arrived too late to affect the battle.) The Support Group at Marsa Brega were confident. The battery commander with the Tower Hamlets reported to his commanding officer that the infantry were quite happy and intended to stay where they were.