Chapter 4: At Bay: The Easter Battle

On 21st January 1941 a small group of officers watched the assault on Tobruk by the 6th Australian Division. One was Brigadier Morshead, just arrived in the Middle East from Britain; another was Lieut.-Colonel T. P. Cook, who had been appointed to take charge of the base sub-area to be established there; a third was Lieut.-Commander D. V. Duff, who was later to be Naval Officer-in-Charge at Derna during the “Benghazi Handicap” and still later in command of the schooners and other small craft running supplies to Tobruk during the siege.

Brigadier Morshead spent several days, after Tobruk’s fall, inspecting the defences of the fortress. Thus he acquired a knowledge of their quality. Later, when the 9th Division’s withdrawal from the Jebel country of Cyrenaica had become inevitable, it was invaluable to Morshead, foreseeing that the division would have to stand at Tobruk, to know what its defences had to offer.

Lieut.-Colonel Cook’s task of course involved his remaining in Tobruk. The base sub-area staff (which had been recruited mainly from the AIF staging camp at Amiriya) moved into the town as soon as the harbour was captured. On 29th January Brigadier Godfrey, who had been appointed area commander,1 established his headquarters in the town area and delegated the task of establishing the base to Cook. Within a fortnight, Godfrey was recalled to Palestine and Cook succeeded him as area commander.

The speed with which the fortress was organised into a working base and provisioned during the next month was remarkable. The stocks of food and other supplies then built up were soon to stand the fortress in good stead. In the first fortnight two excellent water-pumping stations, one in the Wadi Sehel just outside the perimeter, the other in the Wadi Auda, which, though mined by the Italians, had not been demolished, were repaired, the electrical power system was put in working order and the bulk petrol storage system repaired: most of this work was done by the 2/4th Field Company. In addition, in the first fortnight of February, 8,000 of the 25,000 prisoners taken at Tobruk were removed. Much other work was done.

Soon after his appointment as area commander, Colonel Cook became very concerned at the number of rumours circulating through the fortress – some of them harmful to morale. The way to counter falsehood, he decided, was to publish the truth. Sergeant Williams2 of the Australian Army Service Corps was commissioned to publish a daily news sheet, under the title Tobruk Truth or “The Dinkum Oil”. Though unpretentious, it served its purpose well, publishing news culled from BBC broadcasts together with items of local interest; like most daily newspapers it was “printed”

(in fact, roneoed on a captured Italian duplicator) in the very early hours of the morning so that it could be sent to the depots for issue with the daily rations. It was a going concern when the siege began and continued throughout the siege; when later the duplicator was wrecked by bomb-blast, other means of continuing publication were quickly found. To cater for its wider public, it increased its circulation to 800 copies a day; every unit and detachment received a copy. Sergeant Williams did almost all the work lone-handed.

On 8th March, Colonel Cook issued an “appreciation” on the problem of defending Tobruk. Points in his plan were:

to organise the defenders into three components – a mobile striking force, a mobile reserve, and the rest of the garrison; to withdraw “all troops who are outside the inner perimeter closer to the town”; and “to place control posts at all roads through the inner perimeter and reconstruct the Italian road blocks”.

Tobruk Fortress Operations Order No. 1, embodying this plan, was issued two days later.

On 17th March and succeeding days the 26th Brigade arrived in Tobruk, to be followed on 26th March by the 24th Brigade with two battalions, the 2/28th and 2/43rd. On 25th March, the 24th Brigade, which Brigadier Godfrey now commanded, took over duties from the 26th Brigade as the latter moved out to join Morshead’s division on the escarpment above Benghazi.

Godfrey, with his operations staff officer, Major Ogle,3 made a detailed reconnaissance of the defences, after which he suggested to Cook (on 31st March) that the defence plan should be modified by the occupation of part of the perimeter defences. In the next few days the situation in Cyrenaica deteriorated. By 6th April the perimeter defences in the west had been occupied in a wide arc from the Derna Road to Post R19. All available troops were used: Australian Army Service Corps men, unemployed because of the shortage of vehicles, took over prisoner-of-war guard duties, freeing a company of the 2/23rd Battalion.

In the story of the defence of Tobruk, a place of honour will always be reserved for the “Bush Artillery” – those captured Italian guns in great variety of size, vintage, and reliability, that infantrymen without gunner training manned and fired in a manner as spirited as the fire orders employed were unorthodox. The bush artillery was born before the siege began.

When General Neame issued his “Policy for Defence of Cyrenaica” on 20th March, he included a paragraph providing for the organisation of the Tobruk defences which contained the sentence: “Italian field guns will be placed in position for anti-tank duties.” Colonel Cook found that most Italian guns at Tobruk were not usable because of corrosion through exposure to the weather or damage before capture. He brought a large number of Italian 40-mm anti-tank guns from Bardia (in contravention of instructions issued by Neame’s headquarters) and gave the workshops

the task of reconditioning them and the few usable field guns left in Tobruk. Cook next organised a school to train the infantry in their use. It was run by the Nottinghamshire Sherwood Rangers, who were manning the coastal defence guns.4 The object, as Cook later said, was “to run half-day classes in how to load, aim and fire an Italian gun with the least risk to the firer and the maximum to the enemy ... they did learn something from this, using lanyards of telephone wire 100 feet long, chocking wheels to gain elevation”. Brigadier Godfrey cooperated enthusiastically. As the reconditioned guns left the workshops, he allotted them to units and saw to it that they were well manned and sited. The 2/28th Battalion war diary has an interesting entry on 7th April:–

Personnel of No. 6 Platoon5 did a good job on previous night which was pulling into position of five Italian 75-mm field pieces together with ammunition for the same. This brought total to 8 all manned by 4 Platoon.6

On 7th April the 18th Brigade (Brigadier Wootten) arrived, some parties coming by road, but the main body by sea. Brigadier Wootten was appointed commander of the force in Tobruk, Lieut-Colonel J. E. G. Martin taking over acting command of the brigade. Wootten decided that, with the larger number of troops, the whole perimeter should be occupied, the 24th Brigade, with its two battalions and attached troops in the western sector, the 18th Brigade in the eastern sector, with two battalions on the perimeter and one in reserve. These positions were being taken up when, on the morning of the 8th, General Wavell and General Lavarack flew in.

–:–

Wavell had foreseen, after he had returned to Cairo from Neame’s headquarters on the evening of 3rd April, that the abandonment of Cyrenaica could not be long delayed. He knew the time for deciding whether an attempt should be made to hold Tobruk was imminent Having advised the Chiefs of Staff that the plans for operations in Greece and the Dodecanese would have to be modified, he lost no time in sending to the desert front all reinforcements he could muster. An improvised tank force comprising the 1st Royal Tank Regiment with 11 cruiser and 15 light tanks, the 107th RHA, the 14th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, the 11th Hussars (less one squadron), the 3rd Royal Horse Artillery (whose “J” Battery was already with the 2nd Armoured Division) and the 4th Royal Horse Artillery were ordered on the 4th to move next day to the desert. The 7th Australian Division (Major-General Lavarack) was at this time preparing to move from Palestine to Greece; General Lavarack and a nucleus staff had already received orders to proceed to Alexandria, arriving on 5th April for embarkation on the 6th. Passing through Cairo on 4th April, Lavarack received a message directing him to report to General Headquarters. There, in the evening, Wavell received him. Lavarack later reported the gist of the conversation:–

General Wavell consulted me on the question of sending my 18th Infantry Brigade to Tobruk together with 2/ 4th Australian Field Company, 2/5th Australian Field

Ambulance and a British Army field regiment in an endeavour to forestall the danger to 9th Australian Division’s flank and rear. This consultation was probably more formal than real, as something had to be done in any case to assist 9th Australian Division and the troops named were the only ones available. I agreed. I was also informed that the move of my division to Greece would probably be cancelled and the division employed in an endeavour to stabilise the situation in the Western Desert.7

After the conference, at 6 p.m., orders were given by telephone to the commander of the 18th Brigade to move his brigade to Tobruk next morning, in part by road, but mainly by ship. General Wavell telegraphed these intentions to General Sturdee, Chief of the Australian General Staff, in a message the text of which was repeated to General Blamey, then in Greece. In this, after indicating the current situation of the 9th Australian Division in Libya, Wavell said:–

18th Australian Infantry Brigade has been ordered to proceed at short notice to Tobruk. Remainder 7th Australian Division is in Palestine and I hope to send it to Greece but may be compelled to send it to Cyrenaica. ... Am keeping Blamey in touch situation and much regret necessity to alter plans. Have explained situation personally to Lavarack and C.I.G.S. approves change of plan.

One may surmise that Wavell chose to make the decision without seeking General Blamey’s prior consent and to announce it in the way he did because he intended to leave no opening for disagreement with the arrangements.8 Although Wavell told Sturdee that he was “keeping Blamey in touch”, it would appear that this very message was the first intimation to Blamey of any question of diverting to the desert some of the forces previously allocated to Greece, including one of his own divisions.

The Australian Government was very disturbed. Mr Spender, the Minister for the Army, cabled General Blamey seeking his comments on General Wavell’s communication and his assessment of its effect on the Greek expeditionary force. He told Blamey that the Government was “greatly concerned and unwilling”.

General Blamey’s reaction was such as Wavell might have feared. He cabled Wavell on the 5th (and repeated the cable to Australia) suggesting that full advantage should be taken of the desert and of British amphibious power to increase the enemy’s maintenance difficulties in North Africa and that the retention of Libya was not vital to the defence of Egypt, however much its loss might affect British prestige; with all of which Wavell would probably have fully agreed. Blamey added that the Imperial forces in Greece would shortly be in grave peril if not built up to adequate strength. But Blamey, it should be observed, while stressing the danger to the Grecian expedition, did not seek to limit Wavell’s freedom to dispose the Australian formations as he thought best. In the field in Greece, Blamey was in no position to assess the complete situation. This incident points the difficulties that may arise if the commander of a Dominion expeditionary force of which the component formations are engaged on two

or more fronts exercises field command on one of them, and raises the question whether such a commander should not always be so placed as to be in close touch with the theatre commander directing all the operations in which (except for minor detachments) the Dominion formations are engaged.

Replying to Blamey, Wavell said that he fully sympathised with his views about the 7th Division and much regretted the necessity of moving the 18th Brigade to Tobruk; but Blamey would realise the importance of a secure base in Egypt on which the successful maintenance of the forces in Greece depended. Wavell said that the situation in Cyrenaica was now slightly better and that he still hoped to send the other brigades of the 7th Division to Greece and later, when he could make other troops available, the 18th Brigade also.

If the situation was “slightly better” on the 5th, it was incomparably worse on the 6th when Wavell learnt in turn of the German advance into Greece, the outflanking move against Mechili and the withdrawal of the 9th Division to Gazala. While the news of events in the desert was being telegraphed to Cairo on the afternoon of the 6th, a conference was being held at General Headquarters to decide future policy in relation to Tobruk. As well as the commanders-in-chief of the three Services in the Middle East, Mr Anthony Eden and Sir John Dill were present. General de Guingand has described the conference:–

The atmosphere was certainly tense. The subject was Tobruk. I noticed Eden’s fingers drumming on the table; he looked nervous. ... After the problem had been discussed from each service point of view, Wavell was asked to give his views. I admired him tremendously at that moment. He had a very heavy load to carry but he looked calm and collected, and said that in his view we must hold Tobruk, and that he considered that this was possible. One could feel the sense of relief that this decision produced.9

So the conference decided that an attempt would be made to stabilise the desert front at Tobruk. It was thought that this might involve holding the Tobruk defences for the next two months, after which, it was hoped, sufficient armoured forces would be available to launch a counteroffensive.

General Wavell determined that the rest of the 7th Australian Division should be sent to Mersa Matruh instead of to Greece and that the bulk of the 6th British Division should also be diverted to the Western Desert from the Nile Delta, where it had been training for a projected operation against Rhodes. He also decided that General Lavarack should succeed General Neame as commander-in-chief in Cyrenaica. In the immediate future the main burden of the attempt to stabilise the front at Tobruk would have to be borne by the four Australian brigades already with Cyrenaica Force and, for the time being, the remainder of the 7th Australian Division would constitute the main force available for the defence of Egypt. It was therefore natural that consideration should have been given to placing the force under an Australian commander. In Lavarack,

Wavell had chosen for the appointment a senior professional soldier who had not only had extensive operational experience in the first world war but also had served for four years between the wars as Chief of the Australian General Staff.

No time was lost in acting upon these decisions. That evening the 22nd Guards Brigade with supporting field and anti-tank artillery set out from Cairo for the frontier area. General Lavarack was summoned to Wavell’s headquarters.

Meanwhile Wavell had learnt of the capture of Generals Neame and O’Connor and Brigadier Combe. General de Guingand has written that Wavell was greatly affected. He received Lavarack at midday on the 7th, proposed to him that he should take over the Cyrenaican command, and sought his concurrence in the cancellation of the embarkation of the rest of the 7th Division (the 18th Brigade had arrived in Tobruk that morning). Lavarack agreed to both arrangements. Wavell decided to fly with Lavarack to Tobruk next day to install him in his new command. The 7th Division was warned to move immediately from Palestine to Amiriya, for forward movement to Mersa Matruh.

Wavell reported the current situation to the Chiefs of Staff and General Sturdee (and to General Dill and General Blamey in Greece) indicating his intention to fly to Tobruk on the morrow with Lavarack “who will probably take over command of all forces in Cyrenaica”. His current intentions and his contemporary estimate of the enemy are both revealed in the two messages sent by him on this day to London and Melbourne. In the first, he announced that it was hoped to stabilise the front at Tobruk and that he estimated that the German force in Cyrenaica might consist of all or part of one armoured and two motorised divisions. In the second, his perhaps unduly sanguine comment was that, although the situation in Cyrenaica remained obscure, the general impression of the enemy was rather more of a series of raids by light forces than large-scale attacks.

Meanwhile Mr Churchill, ceaselessly striving to imbue the British forces with his own spirit of aggression and defiance was exhorting his commander-in-chief in the Middle East to stop the retreat and fight back. “You should surely be able to hold Tobruk,” he told Wavell in a message sent on the same day, “with its permanent Italian defences, at least until the enemy brings up strong artillery forces. It seems difficult to believe he can do this for some weeks.” He pointed to the risk the enemy would run in masking Tobruk and advancing upon Egypt, and added: “Tobruk therefore seems to be a place to be held to the death without thought of retirement.”

When General Wavell and General Lavarack landed at the Tobruk airfield at 10 a.m. on the 8th, the khamsin which that morning had heralded the German attack on Mechili was blowing fiercely; almost an hour elapsed after their landing before their reception party found them amidst the swirling sand and dust. As soon as they arrived at command headquarters, Wavell held a conference with Brigadier Harding and other senior staff

of Cyrenaica Command, at which Captain Poland,10 the Senior Naval Officer, Inshore Squadron, and Group Captain Brown, the Royal Air Force commander, were present, and at which, as we saw, General Morshead soon afterwards arrived. Wavell heard Harding’s and Morshead’s reports, briefly studied a map of Tobruk and announced that Lavarack would take over command of all British forces in Cyrenaica. There were no forces between Tobruk and Cairo, he said, but a stand was to be made at Tobruk; it might have to be held for about two months while other forces were assembled. He then wrote out in pencil on three sheets of note-paper the following instruction to General Lavarack:–

1. You will take over command of all troops in Cyrenaica. Certain reinforcements have already been notified as being sent you. You will be informed of any others which it is decided to send.

2. Your main task will be to hold the enemy’s advance at Tobruk, in order to give time for the assembly of reinforcements, especially of armoured troops, for the defence of Egypt.

3. To gain time for the assembly of the required reinforcements, it may be necessary to hold Tobruk for about two months.

4. Should you consider after reviewing the situation and in the light of the strength deployed by the enemy that it is not possible to maintain your position at Tobruk for this length of time, you will report your views when a decision will be taken by G.H.Q.

5. You will in any case prepare a plan for withdrawal from Tobruk, by land and by sea, should withdrawal become necessary.

6. Your defence will be as mobile as possible and you will take any opportunity of hindering the enemy’s concentration by offensive action.

In the afternoon, Wavell set off to fly back to Cairo and Lavarack fare-welled him at the airfield. But after a false start the aircraft had to return for repairs. It was dusk before it took off again. Within a short time it developed engine trouble and was forced to make a night landing in the desert some distance out from Salum; the machine was wrecked. For six anxious hours General Headquarters, Cairo, feared that, following on the capture of Generals Neame, O’Connor and Gambier-Parry, there had occurred, to cap all, an even greater misfortune, the loss of their commander-in-chief. But a patrol found Wavell’s party in the desert that night and brought them into Salum. Early next morning Wavell flew on in a Lysander11 to Cairo.

There, on the 9th, Wavell sent a cable to London and Melbourne describing the situation in Tobruk and western Egypt. He added:–

I have put Lavarack, G.O.C. 7th Australian Division, in command in Cyrenaica for the present. Am considering re-organisation of command placing whole western desert defences from Tobruk to Maaten Baggush under one command Although the first enemy effort seems to be exhausting itself I do not feel we shall have long respite and am still very anxious. Tobruk is not a good defensive position. Long line of communication behind is hardly protected at all and is unorganised.

From this message it is apparent that General Wavell still tended to underestimate the extent to which General Rommel could surmount his

administrative and supply difficulties and hoped not only to halt the enemy’s advance at Tobruk but to keep the land route to Egypt open as a supply line, a plan to which (as General Auchinleck was to observe some nine months later) the configuration of the coast did not lend itself. That intention, however, had been less clearly expressed in his unpremeditated orders to General Lavarack. It also appears that, in appointing Lavarack to the Cyrenaican command “for the present”, Wavell was deferring until later, when the situation had become less fluid, a decision on the final form of organisation for the desert command and the choice of the commander. General Wavell wrote to General Blamey on the same day and told him of his visit to Tobruk. The trouble in Cyrenaica, he explained, had been mainly caused by mechanical failures in the 3rd Armoured Brigade. He commended the part played by the 9th Australian Division, and continued:

I am very sorry to have had to use part of the 7th Division without reference to you, but the need was urgent and I had the support of the C.I.G.S. and Eden, who was acting as the P.M’s Emissary out here. ... I know you did not altogether approve of the decisions taken, but in the circumstances I think they were perhaps inevitable; anyway in the circumstances that arose I felt bound to take the decision I did and am fully responsible for it.

As a postscript to the typewritten letter, doubtless written, as he said, in great haste, he added the following sentence in his own handwriting:

As you probably know, Neame and O’Connor disappeared during the retreat. I have put Lavarack in command at Tobruk and enclose a copy of the instructions I gave him yesterday.

Wavell’s decision to send one additional brigade (the 18th) from the 7th Division to Tobruk indicated that he had decided that the size of the force with which he would attempt to hold Tobruk would be approximately four infantry brigade groups plus a small tank force – all the tanks he could muster. Subsequent experience indicated that a force of this size was just adequate for the task but gave no safety margin. In later months the garrison was strengthened in various minor respects but its size was not materially increased.

General Wavell’s concept had been to use the garrison force to establish a stronghold at Tobruk while utilising the mobile forces, mainly the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade and the reinforcements from the 7th Armoured Division sent forward to strengthen the Support Group, to harass the enemy in the desert. Brigadier Gott had just arrived in the Tobruk area to take command of these, an appointment which, as we saw, General O’Connor had suggested to General Wavell. But the prospective strength of the mobile force, parts of which had been battered in the Marsa Brega–Agedabia phase, had been critically reduced by further losses sustained around Derna, followed by the capture that very morning of most of the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade at Mechili. The 1/Tower Hamlets could muster only one strong company.

–:–

General Lavarack’s urgent tasks were to acquaint himself with the considerable but unintegrated forces committed to him, to give them an

ordered system of organisation and command, to reconnoitre the terrain and defences and to report in due course, as Wavell’s instruction to him required, whether it would be practicable with the forces available to attempt to hold Tobruk for two months.

In detail the composition and location of the forces placed under Lavarack’s command on the 8th were as follows. At Acroma, west of Tobruk, were the 20th and 26th Brigades with the 1st RHA, the 51st Field Regiment and the 1/Royal Northumberland Fusiliers in support. In Tobruk were the 18th and 24th Brigades with the 104th RHA, what was left of the Support Group and the 3rd Armoured Brigade, anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery units, and the newly arrived 1st Royal Tank Regiment. The 107th RHA was due to arrive by sea on the morrow. In addition there were the normal complement of troops of the various Services, three Libyan refugee battalions and three Indian pioneer companies. On this day the 11th Hussars were moving up to El Adem from the frontier and the 3rd RHA and other minor units destined for the Support Group arrived in Tobruk by road.

The 18th (Indian) Cavalry Regiment was at El Adem, where it was joined that day by Captain Barlow’s squadron, followed, in the next 24 hours, by other elements of the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade, Major Eden’s anti-tank battery and most of the 2/3rd Australian Anti-Tank Regiment – all having broken out of Mechili.

General Lavarack decided to divide his combatant forces into three groups. The first group, being the main force, was to be responsible for the defence of Tobruk fortress. General Morshead would command it and would be appointed fortress commander. Its main components would be the 9th Division with its eight infantry battalions, the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion, and other attached troops, the four British artillery regiments, the 1/Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (medium machine-guns) and the 1/King’s Dragoon Guards (as a reconnaissance regiment). The second group would be the mobile force, under Brigadier Gott’s command – a reorganised Support Group strengthened by some units just arrived in the forward zone of which the most important were the 11th Hussars (less one squadron) and the 4th RHA (less one battery): it was to operate outside the perimeter. The third group, which would constitute Cyrenaica Command’s force reserve, would comprise the 18th Brigade with a battery of anti-tank guns (“J” Battery, 3rd RHA) and an improvised armoured force containing all the available tanks.

The adoption of this organisation involved freeing the 18th Brigade from its task of occupying part of the Tobruk perimeter and using the whole of the 9th Division for the perimeter defence. Lavarack visited Morshead on the afternoon of the 8th to inform him of these intentions. He instructed Morshead that the rest of the division was to be withdrawn within the perimeter and arranged with him to reconnoitre the perimeter defences next day.

What remained of the 2nd Armoured Division was split up amongst the three main groups. The only tanks the division had brought back

into Tobruk were one light tank of the brigade headquarters recovery section and two cruisers (presumably those two which, separated from the main body, had come to the 9th Division’s assistance at Tmimi) But the 1st Royal Tank Regiment had just arrived with 11 cruisers and 15 light tanks, and there were in the Tobruk workshops 18 serviceable light tanks and some 26 medium undergoing repair. Lieut-Colonel Drew took charge of all armoured units on the 8th and organised them into a formation to be known as the 3rd Armoured Brigade, in which initially there were two tank units: the 1st Royal Tanks, and a composite unit of 3rd Hussars and 5th Royal Tanks personnel. The composite unit was immediately equipped, out of the workshops, with 4 cruisers and 18 light tanks.

Units from the 2nd and 7th Armoured Divisions’ Support Groups were variously allocated. The 1/King’s Dragoon Guards were, as mentioned, allotted to the 9th Division. The French motor infantry were directed to Salum. The 1/King’s Royal Rifle Corps (less Mason’s company, which had been cut off at Derna) was sent to rejoin Gott’s force together with a composite motorised company organised from what remained of the 1/Tower Hamlets Rifles. On the other hand, the 18th Cavalry Regiment (whose carriers were used to equip the 1/KRRC) was to be brought into Tobruk and placed under command of the 9th Division. The role of Gott’s force was defined. It was to harass the enemy south of the main coast road.

The 9th Division had come to Cyrenaica without its artillery12 and therefore the headquarters had no staff to control the four regiments allotted to it.13 The task of forming a command organisation was given to Brigadier Thompson,14 who had recently arrived from Palestine to take up the appointment of senior artillery officer with Cyrenaica Command. One of the most urgent tasks was to allot the anti-tank artillery, which comprised the 3rd RHA, the 2/3rd Australian Anti-Tank Regiment (less the two rearguard troops lost at Mechili, and one battery at Mersa Matruh), and the four Australian brigade anti-tank companies. Of the three batteries of the 3rd RHA immediately available, one (“M” Battery) was allotted to the fortress command, one, “D” Battery – made up to strength at the expense of “J” Battery – to Gott’s force, and one (“J” Battery) to the reserve.

Meanwhile the anti-aircraft artillery, destined to play a leading role in the defence of Tobruk, was being strengthened as guns came back from Cyrenaica and outlying airfields and others arrived by sea. Its main strength, when the investment began, consisted of 16 heavy (3.7-inch) guns.

While Lavarack’s force, with its four brigade groups, its few tanks and its light harassing detachment, was being organised at Tobruk, other

forces were moving towards the frontier. The 22nd Guards Brigade was already in Mersa Matruh, whence one of its battalions with a squadron of light tanks of the 7th Hussars was moving forward to Salum. A second brigade of the 6th British Division was moving towards Mersa Matruh. To provide some further insurance, arrangements were being made to ship the 4th Indian Division from the Sudan to Egypt; the first brigade was due to arrive on the 11th.

To the west of Tobruk, on the morning of 8th April, the exhausted troops of the 9th Division were improving their positions astride the main coast road at Acroma and keeping the best watch they could, through thick dust, for the enemy’s approach. News of the most recent reverse – the fall of Mechili – reached them in the morning. During the day battalions were sorted out, exchanged positions and reverted to their normal brigade commands. The 26th Brigade held the right from the road to the sea, while the 20th Brigade watched and guarded the open desert flank. For the first time for two days, a hot evening meal was served. Between the Australian infantry and the British troops supporting them mutual regard and trust had already developed. “We still have the 1/Northumberland Fusiliers with us (and our fellows swear by them),” wrote the diarist of the 2/48th, adding that the defences were now well organised and that everyone was “praying for the Hun to ‘have a go’.”

The enemy ground forces took no offensive action that day, although in the early afternoon a few German armoured cars reconnoitred on the fringe of the 2/17th Battalion. Some stragglers escaping from Derna reported that the British prisoners captured there, including the two generals, were being held in a wadi near the town and very lightly guarded. Morshead arranged with Brigadier Murray to send out a patrol that night to attempt their rescue. Major Allan15 was appointed to command it and the 1/King’s Dragoon Guards were instructed to provide four armoured cars as protection. Their commanding officer, Lieut-Colonel McCorquodale, protested to Morshead that the task was a misuse of armoured cars because of their vulnerability at night when confined to roads. Morshead had his way, but the patrol left late, was delayed by demolitions made the previous day near Gazala and, being then unable to reach Derna in the night hours, returned with its task unaccomplished.

On 9th April, General Lavarack, in company with General Morshead, Brigadier Harding and Brigadier Wootten, made an extensive reconnaissance of the fortress area – a very good reconnaissance, Morshead later called it. Wavell had suggested to Lavarack that the outer perimeter of the fortress, which was some 28 miles in length (the total length of the “Red Line” defensive works was 30 miles and a quarter), was too extended to hold with the forces available and that the defence should be based on the “inner perimeter”. Wavell may have derived the notion that there was an inner perimeter at Tobruk from reading Colonel Cook’s appreciation, but Lavarack soon discovered that no real inner defence

perimeter existed. There were a few rudimentary weapon-pits and ineffective tank traps behind the “outer” perimeter, but no connected or useful system of defence. Lavarack had quickly concluded that there was no practicable alternative to holding the developed perimeter defences, protected as they were in great part by wire, anti-tank mines and ditches. The purpose of his reconnaissance was therefore to determine brigade sectors, to site a second line of defence, and to establish a “last-ditch” line surrounding the harbour area; also to decide on a location for the reserve brigade.

Lavarack desired to bring the 9th Division within the perimeter immediately. Morshead, on the other hand, was anxious to spare his men the fatigue of an intermediate move before arrangements could be made for them to occupy their allotted sectors. But, after a quiet morning, an enemy column approached the Acroma positions in the early afternoon and reports from the air force, which came in soon after Lavarack’s reconnaissance had been completed, indicated that about 300 vehicles were approaching Tobruk from the west while other columns of vehicles were setting out eastwards from Mechili. The withdrawal of the two brigade groups from exposed positions outside the perimeter had become urgent. Morshead ordered them to retire from Acroma that night. The fortress had meanwhile received two important reinforcements by sea – the 107th RHA (bringing the fortress’s field artillery up to four regiments) and portion of the 4th Royal Tank Regiment, with four infantry (heavy) tanks.

The enemy column that had approached Acroma in the early afternoon halted just out of range of the British guns. German armoured cars nosed forward as though to determine the limits of the ground held. There were signs that an attack was being prepared. Towards sundown an enemy gun to the west opened up and lightly shelled the 26th Brigade – for many of the men their first experience of battle-fire – while enemy vehicles appeared over the skyline. The 51st Field Regiment replied at once; soon afterwards the 1st RHA, having turned their guns through an arc of 125 degrees, joined in the bombardment. The enemy vehicles hastily retreated, the 51st pushed forward a troop to engage them, and the enemy replied with mortars. Firing continued till after dark. As soon as the enemy had ceased firing, the 1st RHA moved back to Tobruk and took up a position in the Pilastrino area, facing south. One by one the other units at Acroma followed during the night; the 2/48th Battalion, which stole away at 4 a.m., was the last to move.

–:–

The impetuous Rommel’s purposeful organisation of the German and Italian forces had been marked by an extreme degree of improvisation. New groupings and new commands were set up almost every day. Each of the major formations – the German 5th Light Division and the Italian Ariete and Brescia Divisions – was split into a number of independently operating groups. The 5th Light Division had been organised in three main columns, the Schwerin Group (from which the Ponath and Behrend

detachments had been sent to Derna), the Streich Group, and the Olbrich Group. The former two had been directed on Mechili by the Trigh el Abd route; the latter had been sent by the northerly route through Msus, and had not reached Mechili in time to take part in the assault. The Ariete Division, broken up into numerous groups, had taken the Trigh el Abd route, while the main body of the Brescia Division, under the direction of Major-General Kirchheim, had pushed east by the two roads across the Jebel Achdar in the wake of the withdrawing 9th Australian Division. The 3rd Reconnaissance Unit, which had encountered the 2/13th Battalion at Er Regima, appears also to have travelled by this route. Meanwhile the first units of the Trento Division had reached Agedabia.

After the capture of Mechili on the 8th, General Rommel ordered the Italian formations in that region to garrison the fort while the Streich Group (the main body of the 5th Light Division) was detailed to protect it from attack from the north and west. Meanwhile the other two German groups (Schwerin and Olbrich) were directed to Derna, where the 3rd Reconnaissance Unit and the Brescia Division were also arriving on the 8th. Rommel himself drove thither in the evening.

General Kirchheim had been wounded, but Major-General Prittwitz, the commander of the 15th Armoured Division, who was on a reconnaissance tour of Africa, had just arrived at Rommel’s headquarters. Although that division was not due to reach Africa until May, arrangements were being made to fly in some of its lighter units immediately. Rommel at once pressed Prittwitz into service in place of Kirchheim, appointing him to command the northern group of German forces now converging on Derna. These consisted in the main of a reconnaissance unit, one machine-gun battalion and a half, a battalion of field artillery and an anti-tank battalion.

On the 9th Rommel directed the pursuit to be resumed with the object of encircling the British at Tobruk. He ordered a deployment around Tobruk: Prittwitz Group to the east and south-east of Tobruk, Streich Group to the south-west, Brescia Division to the west. Early that day, the Ponath detachment, in the van of the Prittwitz Group, arrived 50 miles east of Derna. When this was reported to Rommel, he directed the Prittwitz Group to advance into the area south of Tobruk and ordered the Brescia Division to approach the British force west of Tobruk, stir up as much dust as possible, and subject the British formations to fire from artillery and other heavy weapons so as to contain the force there until the Prittwitz and Streich Groups could attack from the south-east.

The German commander then returned to the Mechili area to spur on the Streich Group and the Ariete Division (some units of which were still more or less immobilised on the track to Mechili) and hasten their arrival. “It was now of great importance,” Rommel wrote afterwards, “to appear in strength before Tobruk and get our attack started as early as possible, for we wanted our blow to fall before the enemy had recovered his morale after our advance through Cyrenaica, and had been able to organise his defence of Tobruk.”

On the morning of 10th April, Rommel issued a statement of his intentions.

I am convinced that the enemy is giving way before us. We must pursue him with all our forces. Our objective, which is to be made known to all troops, is the Suez Canal. In order to prevent the enemy breaking out from Tobruk, encirclement is to go forward with all available means.

That morning, leaving Mechili in the early hours, he drove back to the Tobruk front. On the main coast road west of Tobruk he encountered the Prittwitz Group. Finding that it had not yet commenced the ordered encircling movement to the south, he instructed General Prittwitz to launch an immediate attack with part of his force astride the main coast road and directed the 3rd Reconnaissance Unit to move around the right flank on El Adem. Prittwitz ordered Lieut-Colonel Ponath’s 8th Machine Gun Battalion to lead the Brescia Division in the frontal attack and Ponath’s column set off along the road towards Tobruk at 9 a.m., but without its supporting artillery, which had not arrived. Soon its forward company reconnoitring the route encountered fire from British armoured cars.

The German forces, reaching the neighbourhood of Tobruk so unexpectedly soon, were to suffer from the disadvantage that they knew nothing of the defences and fieldworks there. Not for several days were their Italian allies able to provide them with a map. Groups which in the meantime reconnoitred towards the port or skirted the Tobruk defences brushed up against anti-tank obstacles and wire in unexpected places and found them hotly defended.

–:–

Having arranged with General Morshead on 9th April that the 9th Division would hold the perimeter defences, General Lavarack sent General Wavell a message telling him of this arrangement and of the decision to keep the 18th Brigade and the armour in reserve. He also told Wavell that he had decided to hold the original Italian perimeter in order to take advantage of the existing wire and obstacles until an inner and shorter perimeter had been constructed. The time factor made it essential, he said, to make use of the existing defences; but to hold them with his present force would leave him with insufficient reserve in depth. He was therefore strongly of the opinion that the rest of the 7th Division should be sent up to Tobruk without delay.

General Wavell did not reply immediately. He was on the point of going to Greece to review operations on that front with General Wilson and General Blamey. Probably one reason for Wavell’s visit was that he wished to explain personally to Blamey why he had diverted the 7th Australian Division from Greece to the desert, an action with which Blamey appeared to have been very displeased. The officer who first conveyed the decision to Blamey is said to have reported his reaction thus: “When the General read that telegram, he blew up.”16 Before Wavell left for Greece, he told the Chiefs of Staff in London that he had decided to hold Tobruk, to place a mobile force on the Egyptian frontier and

to build up the defences of Mersa Matruh: the distribution of his force so as to gain time and yet not risk defeat in detail would be a difficult calculation; it would be a race against time. That message reached London just as another exhortation from Mr Churchill urging that Tobruk be held was about to be dispatched: it was not transmitted.

General Lavarack sent for Brigadier Gott on the morning of 10th April to settle with him the policy for the future employment of the mobile forces. The main question to determine was what the Support Group should do in the likely event that enemy forces in strength should threaten to embroil it in its present position at El Adem. Lavarack decided that if this happened the mobile force should operate from the frontier rather than risk being bottled up in Tobruk. He instructed Gott that if it was pressed by the enemy, it was to retire towards the Egyptian frontier. For the aim, expressed in Wavell’s orders, of holding the enemy’s advance at Tobruk Lavarack had substituted an intention to hold Tobruk against an encircling force, encirclement being regarded as almost inevitable.

The 10th April, for many men of the 9th Division their first day in Tobruk, began quietly. Mobile patrols going out at first light from the 18th Cavalry Regiment and the 1/King’s Dragoon Guards had nothing to report. A patrol of the 18th Cavalry mounted the escarpment overlooking the Derna Road along which the enemy’s first approach was expected but saw nothing. As the sun rose, a searing wind-storm blew up, concealing the landscape beneath a stream of dust and sand, which reduced visibility to a few feet: “the filthiest day ever,” one unit diarist called it. Units moved out to take up their allotted positions along the perimeter but the men could not see the terrain; as they shovelled sand from trenches, the wind relentlessly replenished them. The khamsin caused intense anxiety to the artillery officers striving to keep the approaches to the perimeter under observation while the posts were being occupied, and to the infantry commanding officers endeavouring to acquaint themselves with the areas they were to defend. Reports that the enemy was approaching under cover of the dust heightened the tension.

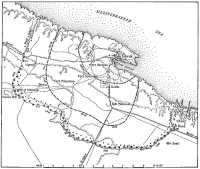

The perimeter on which Lavarack had decided to base the forward defence ran in a wide but not perfect arc some 28 miles in length. The chord of the arc was a bare 17 miles – that was the distance, as the crow flies, separating the two headlands in the east and west at which the perimeter touched the coast. The average radius – or average distance of the perimeter from Tobruk town – was about 9 miles. The bay provided a deep and well-sheltered natural harbour, the best in Italian North Africa, but now fouled by several sunken ships. The coast, except near the harbour, was broken by a succession of narrow inlets between high headlands. There was a plain about three miles wide west of the town. It was bounded on the south by an escarpment, at the top of which was a ledge of land leading to a second escarpment. Southwards from the top of the second escarpment the country flattened out towards the perimeter, except in the south-west where it swept up towards a dominant point on the skyline, Ras el Medauuar, which was surmounted by a blockhouse. In the east the

Tobruk defence lines

plain narrowed to nothing as the two escarpments converged on the coast near the perimeter boundary.

The 28 miles of perimeter were to be taken over on this day by the three brigades of the 9th Division – from right to left, the 26th, 20th and 24th Brigades – using six battalions to man the perimeter line. One regiment of field guns was allotted to each brigade sector and, pending the development of a communications network to enable the artillery to be coordinated from fortress headquarters, the regiments were placed under the command of the infantry brigades. In the southern sector (20th Brigade) the 107th RHA was superimposed on the 1st RHA

The 2/24th Battalion plus one company of the 2/23rd Battalion was ordered to occupy the right-hand sector, from the coast to the escarpment, a distance of six miles. It would thus be placed astride the main coast road coming in from Derna and the west by which the division had just entered the perimeter, and along which the Axis forces could be expected to follow. There the defences were sighted near the crest of the slopes of a huge gorge, the Wadi Sehel, which cut right across the plain from the sea to the coast road and, continuing, cleft the escarpment to the south of the road. To the left of the 2/24th, the key western sector, which

included Ras el Medauuar, the highest point on the perimeter, was allotted to the 2/48th Battalion. On its left again the 2/17th Battalion was to guard the southern approaches to Fort Pilastrino, in which area were sited the old Italian headquarters, now taken over by Morshead’s headquarters. Next would be the 2/13th Battalion, astride the El Adem Road, then the 2/28th Battalion, and, to complete the arc, the 2/43rd Battalion occupying the eastern sector from the main east-west road to the coast.

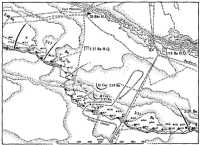

Before these positions were occupied, and while battalion commanding officers were reconnoitring the areas allotted to them, reports were received that the enemy was approaching. Soon after 9 a.m. Lieutenant Bamgarten of the 2/3rd Field Company demolished the bridge over the wadi at the western gateway of the perimeter just as the first troops of Ponath’s column, which had been pursuing a look-out patrol of the King’s Dragoon Guards, came down the road towards it. The German column consisted of about two companies of infantry, with machine-guns, some light field guns and seven light tanks.

About 500 yards behind the wire where the Derna Road entered the perimeter was dug in one of the bush artillery guns of the 2/28th manned by Corporal Tracey-Patte.17 “C” and “E” Troops of the 51st Field Regiment, whose guns were also sited close to the perimeter behind the roadblock, engaged the German vehicles as they came into sight through the screening dust-storm, causing them to withdraw and deploy, and Tracey-Patte’s gun joined in. Captain Jackman18 of the 1/Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, reconnoitring the area at this moment, saw the enemy approaching and called up two platoons of machine-gunners, who engaged the enemy at a range of two miles as they deployed. Some of the vehicles moved south of the road, mounted the escarpment by a track and turned in towards Tobruk above the escarpment, only to bump into the perimeter defences at Post S17, where they were engaged by another bush gun manned by a crew commanded by Sergeant Rule.19

As Prittwitz’s main column set off down the main road, attempting by the speed of its thrust to take the defenders by surprise, three armoured cars had ascended to the plateau in search of a way into Tobruk by a route which would bypass whatever blockage might have been set up across the direct route. These made for the high ground at Ras el Medauuar, where Lieut-Colonel Lloyd,20 commanding the 2/28th Battalion, had set up his headquarters in a location where he would be likely to be the first to see any approaching enemy, if not to engage them. That honour, however, appears to have fallen to two of his bush guns, under the spirited command of his transport officer, Lieutenant Lovegrove.21 One gun, the blast of which was alarming and damaged

the gunpit, “proved more menacing to the Don Company personnel in the vicinity than to the German armoured cars”,22 but the other, commanded by Corporal Warren,23 assisted by the expert advice of an amused senior British artillery officer who happened to be there, was quickly firing so close to the mark that the armoured cars made off.

The Germans did not try to assault across the wadi near the Derna Road but took up positions on the far side and, reinforced by the forward elements of the Brescia Division, brought machine-guns, mortars and light artillery into action. Desultory firing continued throughout the day. Growing more intense in the early afternoon, it interfered with the 2/24th Battalion’s occupation of the sector and eventually forced the two troops of field guns to withdraw. Two gunners and one infantryman were killed; more than 30 men (including 19 gunners) were wounded. The enemy also suffered casualties. Major-General Prittwitz himself was killed.

During the morning Brigadier Gott’s Support Group reported from near El Adem that 40 armoured fighting vehicles were moving north-east from about 10 miles south of the perimeter. Meanwhile, the German 3rd Reconnaissance Unit, feeling its way round the British flank, had a brush with a patrol of the 18th Cavalry Regiment. Pushing on, they came up against the perimeter wire in the western sector, where the defences were still held by the 2/28th Battalion. Several local engagements were fought. Lieut-Colonel Crellin’s24 bush artillery had their first operational shoot, landing some shells amidst the leading enemy vehicles. Guns of the 1st RHA quickly engaged the enemy columns, causing them to disperse. Soon afterwards a British truck was halted by enemy fire as it attempted to leave the perimeter in the southern sector by the El Adem Road. For more than an hour there was no further indication of the enemy’s presence but just before 1 p.m. five enemy tanks were seen in the south-eastern sector from an observation post of the 107th RHA

In the early afternoon the 20th Brigade occupied the perimeter in the southern sector. Soon afterwards men of the 2/13th Battalion discerned a party of enemy infantry about 400 yards to their right front and engaged them with small-arms fire. The enemy went to ground and made off under cover. But in the section of the western sector where the perimeter defences climbed the second (or higher) escarpment, the enemy stayed close and dug in machine-guns opposite the perimeter defences. As the afternoon wore on reports accumulated that the enemy was augmenting his strength in that sector, while other enemy groups, including one of 10 tanks,25 were seen moving round to the south-east.

Meanwhile, the pilots of scouting aircraft reported that three columns, each of 200 vehicles, were approaching El Adem from the direction of Mechili. About 5 p.m. one of these groups encountered Gott’s force some 12 miles south-west of the perimeter. Approximately 150 enemy vehicles

assembled there and were attacked by the Royal Air Force. Towards nightfall they were shelled by a battery of the 4th RHA and forced to disperse. Three German officers were captured.

During the afternoon Gott had reorganised his force. An independent column under Lieut-Colonel J. C. (“Jock”) Campbell was detached to operate against any enemy advancing along the roads leading to the frontier: a precursor of the “Jock” columns that were to set the pattern for much of the desert fighting in the next 18 months.

Firing continued in the western sector for the rest of the afternoon and evening. A company of the 2/48th Battalion relieved portion of the 2/28th Battalion on the perimeter south-west of Medauuar. But even after dark enemy activity continued to be heard to the west in front of part of the perimeter still held by the 2/28th Battalion to the north of Medauuar; after 9 p.m. enemy troops, estimated to number between 600 and 1,000, seemed to be assembling on what appeared to be a start-line for an attack on the battalion’s front; but none developed. The men of the 2/28th stood to arms until the early hours of the 11th, when the rest of the 2/48th Battalion, after an exhausting night march, arrived to take over the sector from them. The 2/28th then moved across to the south-east and arrived in its new sector just as the next day was breaking.

In the evening of 10th April Lavarack had placed the 1st Royal Tank Regiment under Morshead’s direct command, stipulating, however, that his own approval should be obtained before it was committed. A liaison officer from the General Headquarters had arrived at Lavarack’s headquarters during the day; his mission had been to inform Lavarack that it was Wavell’s intention to merge Cyrenaica Command into a Western Desert Command and to confirm that his policy was to conduct an active defence at Tobruk and the frontier for two months, after which he would attack. That night the liaison officer returned to Cairo bearing Lavarack’s reply. Lavarack urged that if Tobruk were to be used as a base for offensive defence with frequent sorties, a garrison of two complete divisions would be required. He requested that this submission should be placed before Wavell for decision and suggested that the rest of the 7th Division should be used to build up the garrison strength to two divisions.

The khamsin that had raged in the early morning of 10th April was subsiding in the afternoon. Next day, Good Friday – a week since the Australians had first encountered the Germans on the escarpment above Benghazi – dawned bright and calm and clear. The men of the 9th Division surveyed the land they had come to live in and defend. From the perimeter defences they looked out across ground that was soon to become the no-man’s-land between two static defence lines. Except at the perimeter’s eastern and western extremities, where the wire descended the escarpments to link with the cliff walls of the Wadi Sehel and Wadi Zeitun (these wadis were deep chasms eroded out of solid rock), the perimeter defences traversed a plateau some 400 to 500 feet above sea-level. Beyond them the terrain was ridged to the west and south-west, but almost flat to the south and south-east, where the ground stretched towards an inland escarpment

visible from points of vantage within the perimeter but not from ground-level at the wire. It was arid, desert country – mottled in parts with a sparse, dwarf shrub-growth (colloquially known as “camel-thorn”), in parts quite bare – and treeless except for a few solitary fig-trees near desert wells, which stood out in their barren environment as remarkable landmarks.

Each day’s first light etched the desert scene in clear outline but as the summer day warmed, a mirage would subtly transform it. The change was scarcely apparent at a casual glance: the colour, the broad masses, were unaltered. But a more intent examination would fail to reveal the detailed configuration of remembered features, which tantalisingly shimmered in eddies of sun-scorched air, as though seen through a watery glaze. That occurred every day unless cloud or dust had blotted out the sun. The mirages soon imposed a degree of regularity on siege artillery programs, for only in the early mornings or late evenings could guns be ranged onto targets by observation, or the effectiveness of their fire be gauged. As each new day dawned, the guns of both sides saluted it; as it departed before the oncoming night, they saluted again.

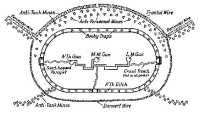

At the eastern and western extremities, the defences in the two comparatively short lengths of perimeter between the road and the sea to the north of it were for the most part sited just below the lips of the wadi walls, which were in general effective obstacles to tanks; there the layout of the defences varied to take advantage of the favourable terrain. But the wide arc of perimeter south of the coast road ran through terrain that did not aid defence, neither hindering frontal assault nor providing concealment to obstacles and weapon-pits. The Italians had surrounded almost the entire perimeter with an excellent “box” wire obstacle; where this had not been completed, concertina wire had been employed. Outside the wire a deep anti-tank ditch, designed to link with the wadis near the coast, had been partly excavated – hewn in solid rock – but not completed. In the apex of each “dog-leg” in the perimeter wire, was sited a perimeter post. These frontal posts were spaced at intervals of about 750 yards; about 500 yards behind them, covering the gaps between each two, was a second row of posts. The perimeter posts were numbered consecutively, the odd-numbered being on the perimeter wire, the even-numbered behind.

The perimeter wire was purely frontal, not extending round the posts. Much of it had fallen into disrepair; some had been removed. The anti-tank ditch had been completed for only about one-fifth of the perimeter south of the coast road. Most of the uncompleted parts were covered by a comparatively ineffective belt of concertina wire. A thin line of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines had been laid in front of the wire, but many of these had been removed since the Italian occupation.

A typical frontier post contained three concrete circular weapon-pits sited at ground level and interconnected by concreted subterranean passages, which led also to bomb-proof subterranean living and storage quarters. But the protection thus afforded was in large part illusory, for while a post might shelter many, few could fight from its three weapon-pits.

If these few were intimidated or subdued – a role for which tanks were admirably suited – the rest of the garrison, trapped below, was at the attackers’ mercy. On the other hand, the siting of the posts was excellent. If there were too few weapon-pits, their field of fire was good. And the perimeter wire was well placed, zigzagging in dog-legs out from one post and in to the next. A forward post could in most cases perfectly enfilade by fire both arms of the perimeter fence leading out from it; which fire would form a beaten zone forward of the next post.

Behind the thin line of perimeter posts, no well-planned arrangement of defences in depth existed. Numerous unsubstantial sangars and shallow weapon-pits were scattered aimlessly about. The so-called “inner perimeter” had consisted of nothing more than a few ineffective anti-tank ditches and breastworks on the main axes of approach.

From the first day of occupation the garrison set about strengthening the defences. This was most arduous work because in most places rock was encountered beneath the surface soil at a depth of less than a foot. The destruction of the two road bridges by which the main coast road traversed the anti-tank obstacle at the western and eastern entrances to the perimeter, and the creation of effective road-blocks on all other roads leading into Tobruk, were the first measures taken. Priority was then given to mining the cross-country approaches to the perimeter in sectors where the anti-tank ditch was not effective, and repairing or restoring the perimeter wire. In the first few days most of the combatant troops were engaged in improving their own local defences; but the burden of the main works fell upon the field engineers, who were allowed no rest after their labours during the withdrawal. The 2/3rd and 2/13th Field Companies began mining the gaps in the anti-tank ditch and restoring the perimeter wire on the night of the 10th.

Notwithstanding the enemy activity opposite the western sector during the night of the 10th, a patrol of the 18th Cavalry, which early next morning went out in four open 15-cwt trucks onto the escarpment overlooking the Derna Road, reported that no enemy could be seen. Farther out, however, in the desert south of the coast road, a column of Gott’s force shelled an enemy column about 12 miles west of the Tobruk perimeter.

It was apparent that enemy columns were leaving the coast road some distance to the west of the perimeter, mounting the escarpment and moving into the desert to the south, just skirting the defences. In mid-morning about 50 vehicles appeared near the western sector on the right of the 20th

Brigade’s front; they were shelled by the garrison’s artillery and dispersed. Lieut-Colonel Crawford sent out a platoon with an artillery observation officer to continue harrying them. On another occasion a patrol of seven enemy tanks was seen, but soon withdrew. Meanwhile the Support Group had reported that about 40 tanks were approaching the El Adem sector of the perimeter from about 10 miles to the south, in which region about 300 vehicles had assembled. At 11.30 a.m. these split into two columns, one of which began moving east along the Trigh Capuzzo.

By noon it was apparent that the enemy was astride the El Adem Road opposite the southern sector in considerable force and was continuing to move east to complete the encirclement. At 12.20, 10 enemy tanks approached Post R59, on the 24th Brigade’s front, and came within 1,000 yards of the post; the 24th Anti-Tank Company engaged them, putting five out of action and forcing the rest to withdraw. Towards 1 o’clock between 20 and 30 trucks appeared outside Post R63. Guns of the 104th RHA forced them to disperse. But other vehicles continued to appear, moving round towards the Bardia Road; they were engaged by the 104th as they went. A platoon of enemy infantry, which had dismounted from their vehicles, then attacked R63 on foot. They were repulsed, but two Australians were wounded, one mortally. A similar fray took place near the boundary of the 2/28th and 2/43rd Battalions. Meanwhile the enemy had cut the Bardia Road. The siege had begun.

At 1.30 p.m. Gott ordered his mobile forces to withdraw to the frontier, communicating this decision to Lavarack by means of an agreed code word. The group’s supply vehicles, which happened to be within the Tobruk perimeter when the road was cut, were compelled to remain there.26 To Morshead’s annoyance, Gott took with him to the frontier the seven antitank guns of “D” Battery of the 3rd RHA In doing so, however, he was acting in conformity with Lavarack’s instructions.

By 1 p.m. 50 vehicles had crossed the Bardia Road. Soon another column of about 40 vehicles came up and, under fire from the British guns, discharged troops astride the road about two miles east of the perimeter, who then moved forward to within half a mile of the defences and there began to dig in. More vehicles followed. Later the 2/43rd Battalion reported that a force of about the strength of one battalion, with supporting arms, armoured cars and a few light tanks had taken up a position between the main road and the coast in mid-afternoon.

Meanwhile, about 3 p.m., enemy infantry had begun advancing towards the perimeter in front of the 2/13th Battalion. The Australians and the British machine-gunners supporting them at first held their fire, but when the enemy were within 400 yards, opened up with all arms. The enemy went to ground. Soon afterwards six enemy lorries drove down the El Adem Road towards the perimeter. The 1st and 104th RHA brought down concentrations which forced their withdrawal. A group of seven tanks then appeared in front of Post R31 and began to advance towards the perimeter, but were hotly engaged by the guns of “B/O” Battery.

About a quarter of an hour later, at 4.15 p.m., artillery observers reported that deployed infantry were advancing towards the 2/17th Battalion positions near R33 from about a mile to the south. Major Goschen27 of the 1st RHA engaged them with 25 rounds of gunfire, which put a stop to the infantry advance. But 20 tanks passed through the barrage and made straight for the perimeter in front of Captain Balfe’s28 company. Captain Balfe later described the action:–

About 70 tanks came right up to the anti-tank ditch and opened fire on our forward posts. They advanced in three waves of about twenty and one of ten. Some of them were big German Mark IV’s, mounting a 75-mm gun. Others were Italian M13’s and there were a lot of Italian light tanks too. The ditch here wasn’t any real obstacle to them, the minefield had only been hastily re-armed and we hadn’t one anti-tank gun forward. We fired on them with anti-tank rifles, Brens and rifles and they didn’t attempt to come through, but blazed away at us and then sheered off east towards the 2/13th’s front.29

About this time, communication between Lieut-Colonel Crawford’s headquarters and Captain Balfe was cut. Crawford, watching the action through binoculars from his command post, saw three tanks that appeared to him to move quickly down the escarpment in rear of Post R32 (Balfe’s headquarters) and reported to Brigadier Murray that a penetration of the perimeter by tanks had occurred. When this was reported to fortress headquarters, the 1st Royal Tank Regiment – with its two squadrons, one of cruisers, and one of light tanks – was placed under Murray’s command. Murray directed them to Crawford for orders. But when the light tanks reached Crawford’s headquarters, he had ascertained that no penetration had occurred. Crawford sent them, and the cruisers which followed later, in the direction in which the German tanks had last been observed.

The German soldiers, who had been taught by their experiences in Europe to believe that boldness and a disregard of risks alone would suffice to carry them to their objectives, were soon to shed their illusions before Tobruk. Encouraged by seeing their tanks firing at point-blank range into the Australian positions without coming to harm, the German infantry came forward again – about 700 men in all – advancing in a mass, shoulder to shoulder. Although the British gunfire fell right among them, still they came on. The Australians in the perimeter posts saw them and waited. “The infantry are still holding their fire,” reported an artillery observation officer, as the enemy closed on Balfe’s company.

When the infantry were about 500 yards out (Balfe said later) we opened up, but in the posts that could reach them we had only two Brens, two anti-tank rifles and a couple of dozen ordinary rifles. The Jerries went to ground at first, but gradually moved forward in bounds under cover of their machine-guns. It was nearly dusk by this time and they managed to reach the anti-tank ditch. From there they mortared near-by posts heavily. We hadn’t any mortars with which to reply and our artillery couldn’t shell the ditch without risk of hitting our own posts.30

Meanwhile the 1st Royal Tank Regiment, with its 11 cruiser tanks, was moving up towards the El Adem road-block. The enemy tanks, after they had left the 2/17th Battalion front, had moved along the 2/13th Battalion’s perimeter, shelling the forward posts as they went. Near the El Adem Road, men of the 2/13th’s mortar platoon, who were manning two Italian 47-mm anti-tank guns, knocked out one Italian medium tank and hit several others. An Italian light tank disabled by small-arms fire was knocked out by one of the anti-tank guns and its crew captured.

At the El Adem Road the enemy tanks encountered a minefield the engineers had laid on the preceding night and were turning away from the perimeter just as the tanks of the 1st Royal Tank Regiment arrived. There was a skirmish at long range between the British tanks and the last wave of 10 enemy tanks. Three light and one medium Italian tanks were knocked out by the British tanks and a German medium tank was destroyed by gunfire; two British medium tanks were lost.31 The enemy force then withdrew.

Meanwhile a detachment of mortars under Sergeant O’Dea32 had succeeded in bringing down fire on the anti-tank ditch in front of Balfe’s company. Later, strong fighting patrols from the 2/17th’s reserve company found that the enemy had departed.

After darkness fell, several enemy tanks probed along the anti-tank ditch in front of the 2/13th Battalion, looking for a crossing. After they had withdrawn, a standing patrol in front of the battalion’s wire reported the approach of a strong enemy party. The patrol engaged the enemy with such good effect that they fled. Other patrols failed to make contact. The intercepted party’s task had apparently been to make a breach in the antitank ditch and wire, for it abandoned demolition charges, Bangalore torpedoes, tools and a pack radio transmitter.

The day’s events had revealed that the enemy was both ignorant and optimistic. It seemed that he had hoped to find some approaches to Tobruk unguarded and to exploit through the gaps towards the harbour area; it was obvious that he was closing all routes of exit, and hoped to capture the entire garrison.

–:–

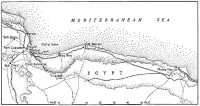

Wavell’s orders and messages had required the development of two main lines of resistance: one at Tobruk, the other at Mersa Matruh, where his counter-offensive force was to be assembled. Between them a mobile force was to be placed on the frontier; but Wavell had not prescribed a “do or die” defence of the crucial Salum-Halfaya bottleneck.

As Rommel’s forces were closing the ring round Tobruk, the jejune preparations to meet his advance at the frontier envisaged a delaying withdrawal rather than a determined attempt to stop it there. A weak company of the French Motor Battalion was guarding the Halfaya pass-head. On the morning of the 10th the 3/Coldstream Guards with a squadron of the 7th Hussars and a battery of the 8th Field Regiment came

The Egyptian frontier area

forward from Mersa Matruh. In the late afternoon they took up a position west of the frontier wire near Capuzzo, astride the north-west approaches of Salum, while Lieut-Colonel Campbell’s detached column (one company of the 1/KRRC with a troop of field guns and a section of anti-tank guns in support) was ordered to operate in the Musaid area, with the task of delaying any enemy advancing along the Trigh Capuzzo or the Bardia Road. That evening a battery of the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment arrived at Salum; it was followed later by Lieutenant Shanahan’s33 troop of the 2/2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, which left Mersa Matruh the same night for Salum, providing anti-tank protection to a column of the 1/Durham Light Infantry coming up to the frontier.

Of the batteries of the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, the 10th and 11th Batteries had fought at Mechili and were now in Tobruk, except some sections lost at Mechili, the 9th Battery had reached Tobruk just before the Axis ring closed round it, and the 12th Battery, the last to move, had set off to make Tobruk by road but had been stopped at Salum because the road had been cut. Commanded by Major Argent,34 it had left Palestine on 5th April, drawn weapons and other equipment while at Amiriya on the 7th, departed for “Cyrenaica” on the night of the 9th, reached Mersa Matruh at 1.30 a.m. next morning and six hours later had set off for Salum. Having passed through Sidi Barrani in the early afternoon of the 10th the battery arrived at the Salum staging camp at 6.30 p.m. that evening. Major Argent at once sought out the town major who instructed him to report to Brigadier Erskine35 (commanding the 22nd Guards Brigade) at the barracks above the Salum Pass.

The battery had almost “to fight its way up the pass” against a stream of eastward-hurrying vehicles, a number with wounded aboard. Major Argent found Brigadier Erskine in conference with Brigadier Gott, who told him that the enemy had cut the road to Tobruk.36 Argent then placed himself under their orders, which were cheerful enough: that the Salum and Halfaya Passes were to be held “at all costs” for 36 hours, until units of the Guards Brigade took over the local defence.

Gott, as we saw, had conferred with Lavarack in Tobruk that morning. His forward columns were operating at that time south-west of Tobruk, in which region three enemy columns of 200 vehicles were proceeding eastwards along the Trigh Capuzzo. At nightfall, however, the head of the Axis force was still not as far east as the western fringe of the Tobruk perimeter. To have attempted to pass Argent’s battery into Tobruk next day would have been unjustifiably hazardous. By one day the battery thus failed to rejoin its regiment and its division. There was no haste to send the battery on by other means; four months later it was still on the frontier. Gott needed it there, but Morshead also needed it in Tobruk. This was only one of many examples of the Middle East Command’s tendency, which General Blamey trenchantly criticised, to allow improvised arrangements to persist and detachments to become permanencies .37

At first light on the 11th Argent’s battery headquarters and two troops (commanded by Lieutenants Rennison38 and Kinnane39) occupied positions in the Fort Capuzzo-Salum Barracks area, covering approaches to the Salum Pass, while Lieutenant Cheetham’s40 troop took up a position covering the company of the French Motor Battalion at the Halfaya Pass.

The forward elements of the two enemy columns on the Trigh Capuzzo, which had begun moving eastwards at 11.30 a.m., had a brush soon afterwards with the Support Group’s right-hand column. About midday, as we noted, another enemy force of tanks and mobile troops operating closer to Tobruk cut the Bardia Road about 8 miles east of the perimeter. By 1 p.m. the enemy columns advancing towards the frontier were almost due south of Tobruk and had crossed the Tobruk-El Adem road, whereupon (at 1.30 p.m.) Gott (as he informed Lavarack) ordered the Support Group’s columns operating outside Tobruk to come back to the frontier. General Headquarters, Middle East, then assumed command of them.

The column of the 1/Durham Light Infantry (Lieut-Colonel E. A. Arderne), with which was Lieutenant Shanahan’s anti-tank troop, reached the Halfaya Pass in the late morning. In the afternoon Colonel Arderne took command of the area above the passes. A defensive position based

on the Halfaya Pass was then organised, with one company of the Durham Light Infantry (and Lieutenant Kinnane’s troop in support) at the top of the pass. Fort Capuzzo, Fort Salum and the Salum Passes were not to be defended. The 12th Anti-Tank Battery’s positions in the Fort Capuzzo-Salum area were abandoned about 5 p.m. and the guns were then sited defensively in the coast sector two miles in rear of brigade headquarters, where the battery was joined by Lieutenant Shanahan’s troop. About 10 p.m. the withdrawn desert columns reached the top of the pass. Later “C” Troop of the 2/2nd Anti-Tank Regiment relieved Shanahan’s troop. On the succeeding two nights, Australian anti-tank guns accompanied British patrols probing forward.

When Major-General Prittwitz was killed Colonel Schwerin took over command of his group. General Rommel was at the Tobruk front on the whole of the 11th directing operations by personal order in the field. On his orders the Schwerin Group had closed the perimeter to the east blocking the coast road. In the early afternoon, when it was reported that Gott’s force was withdrawing towards the Egyptian frontier Rommel ordered the 3rd Reconnaissance Unit, with reinforcements, to proceed along the main road to Bardia, which it was ordered to reach that night. He also directed that a special force be formed from units of the 15th Armoured Division, just arrived by air in the forward area, to join in the pursuit to the frontier by the inland track through El Adem.41 This force was ordered to be ready to depart by dawn on the 12th with Salum as its objective. The group comprised a motor-cycle battalion, an anti-tank battalion, and two batteries of anti-aircraft artillery (one light and one heavy). It was to be commanded by Lieut-Colonel Knabe.

The German component of the tank force that had attacked the 2/17th Battalion was the regimental headquarters and the II Battalion of the 5th Armoured Regiment, with 25 tanks. The regimental commander, Colonel Olbrich, concluded his report on this operation with the comment: “Reports given to the regiment had led it to believe that the enemy would retire immediately on the approach of German tanks.”42 The Brescia Division still held the Derna Road sector. The Fabris and Montemurro detachments had arrived – these probably provided the Italian tanks for the afternoon’s attack; but other German and Italian units had yet to arrive from Mechili.