Chapter 8: Last Counter-Attack and a Controversial Relief

The men of the Tobruk garrison had always thought that the term of their confinement would be the time taken to drive off the besiegers. In the midsummer month of July when the prospect of relief by a frontier offensive seemed indefinitely remote, General Blamey proposed another kind of relief: relief by sea. His request provoked a strong disagreement between the British and Australian Governments; but confidences were so well kept that to all but one or two of the Australians who were in the fortress the first intimation that their going thence had been the subject of controversy was the publication after the war of Sir Winston Churchill’s The Grand Alliance, in which he gave his own account of the dispute. There he declared that it gave him pain to have to relate the incident, but to suppress it indefinitely would have been impossible. “Besides,” he wrote, “the Australian people have a right to know what happened and why.”1 For that very reason it was unfortunate that, in relating the differences between the two Governments, Sir Winston Churchill quoted extensively from his own messages to successive Australian Prime Ministers but did not disclose the text of their replies.

If the Australian people had depended solely on Sir Winston Churchill’s account for knowledge of what happened and why, they might have been left with some erroneous impressions. In particular it might have been inferred that when Mr Fadden’s Government insisted that the relief of the 9th Division should proceed, it did so not because of a strong conviction based on broad considerations advanced by its military advisers but because it had been induced by “hard pressure from its political opponents” to turn a deaf ear to Churchill’s entreaties. That this was Churchill’s opinion is evident from a message sent by him in September 1941 to the Minister of State in Egypt in which he said:–

I was astounded at Australian Government’s decision, being sure it would be repudiated by Australia if the facts could be made known. Allowances must be made for a Government with a majority only of one faced by a bitter Opposition, parts of which at least are isolationist in outlook.2

The political aspects of the controversy have been discussed in another volume of this series.3 It will suffice to say here that no Australian Government was influenced to the course it took by its political opponents. On the contrary the three successive Prime Ministers (who were the leaders of the three political parties in the Commonwealth Parliament) and their governments were in entire agreement. Throughout the controversy the three party leaders sat together on the inter-party Advisory War Council,

to which the question was referred on several occasions. In the course pursued without deviation through two changes of government, the Australian political leaders were guided at each step, indeed impelled in most instances, by the representations of their military advisers – principally by General Blamey himself. The problem was military in origin; if it had political implications, they arose because the British and Australian Governments were in conflict on a military issue.

The conditions upon which the AIF served under the operational command of the Commanders-in-Chief of overseas theatres of war were set out in General Blamey’s “charter”, of which the first operative paragraph read:–

The Force to be recognised as an Australian force under its own Commander, who will have a direct responsibility to the Commonwealth Government with the right to communicate direct with that Government. No part of the Force to be detached or employed apart from the Force without his consent.4

Before this document was issued, the British Government had been informed of the principles to be embodied in it, and had accepted them. The first volume of this series gave earlier instances of General Blamey’s reliance on its terms to resist moves to employ parts of the AIF in detached roles.5 The Australian Government itself had already twice reminded the British Government (in November 1940 and April 1941) of the importance it attached to the concentration of the AIF into one force under a single command. Furthermore Mr Menzies, when in London, had informed the Chief of the Imperial General Staff of his Government’s concern at the dispersion of the AIF. On the same day (19th April 1941) Menzies cabled the Australian Government:–

I have told Dill that it is a matter of imperative importance from Australia’s point of view that all Australian forces should as soon as possible be assembled as one corps under the command of Blamey.

On 1st May 1941, General Blamey cabled Mr Spender, the Australian Minister for the Army:

On returning Egypt (from Greece) I find the AIF distributed among several forces and ten different areas. This distribution was made to meet the emergency that arose mainly through the Italo-German advance in Libya as sufficient other troops were not available. ... It will not be possible to collect the AIF into single force for a considerable time and this is dependent on development of situation in Middle East.

A substantial part of the 6th Division was then in Crete, the 9th Division and one brigade of the 7th in Tobruk, the 7th Division less one brigade at Mersa Matruh, the 7th Divisional Cavalry Regiment in Cyprus; and there were also numerous smaller AIF detachments throughout the Middle East.

The policy of concentrating the AIF into one force had been complicated by another development. In March, after the composition of the

expeditionary force for Greece had been determined, Mr Menzies proposed that the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions and the New Zealand Division, all allocated to the expedition, should be formed into an Anzac Corps.6 The suggestion was not immediately adopted; but, when the campaign in Greece brought the 6th Australian Division and the New Zealand Division together under the command of Blamey’s I Australian Corps, the corps was renamed “Anzac Corps”. The conclusion of that campaign and the piecemeal evacuation of the force from Greece dispersed the formation and dissolved the organisation; but then consideration was given to re-establishing the Anzac Corps as soon as regrouping became possible. On 8th May the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs informed the Australian and New Zealand Governments that General Wavell had welcomed the suggestion that, on being re-equipped, the 6th Australian Division and the New Zealand Division should again be formed into an Anzac Corps; the British Government, he said, favoured the proposal and Wavell recommended that General Freyberg should command the corps. Mr Fadden, the Acting Prime Minister of Australia, telegraphed the proposal to General Blamey but pointed out that, on 18th April, the Government had telegraphed the Dominions Office asking that “subject to over-riding circumstances” the Australian troops should be reassembled as a complete corps under Blamey’s command. He commented:–

The proposal now made would result in a splitting of the Australian force. The 6th Division would, with the New Zealand Division, have the right to be termed Anzacs which they so nobly earned in Greece together ... but the 7th and 9th Divisions would presumably be excluded from this privilege, which may cause some heart-burning.

He sought Blamey’s recommendations both on the reconstitution of the corps and on the appointment of General Freyberg to command it.

Blamey replied that efforts were being made in the Middle East to bring about a more permanent grouping of higher commands: the tentative proposals contemplated one corps headquarters generally for each two infantry divisions. He was strongly of the opinion that to group the three Australian divisions and one New Zealand division in two corps would strengthen their fighting value. He recommended that the 6th Division and the New Zealand Division should be grouped together as Anzac Corps; if this were agreed to, he would recommend that the 7th and 9th Divisions should form Australian Corps when they could be released from the Western Desert. He recommended that General Freyberg, “a bold, skilful and tireless commander”, should command Anzac Corps, General Lavarack Australian Corps.

On 7th June, in a letter to Mr Menzies, General Blamey said that he had been troubled over the extent to which organisations in the Middle East had been broken up; but he recognised that necessity had forced the position from time to time. “I feel,” he said, “that if we could get two corps established, Australian Corps and an Anzac Corps, and pull them together, it would help to establish the principle of working in fixed

formations. This is the main reason for supporting the recommendations. ...”

Meanwhile the Australian Government had become very concerned to discover that the 7th Division’s cavalry regiment was in Cyprus. This disposition had been made without General Blamey’s knowledge while he was in Greece; nor had the Australian Government been informed. In a cable sent on 13th June Mr Menzies reminded Blamey of the importance attached by the Government to the principle that AIF units should serve in their own formations in the Australian Corps under Australian command, and stated that, while it was realised that the Commander-in-Chief might be taxed in the disposition of his forces to meet all contingencies, it appeared rather unfortunate that this small group of Australians should have been placed in Cyprus. Blamey immediately referred his Government’s representations to Wavell, who agreed to arrange the earliest possible relief of the Australian unit.

On 17th June Blamey followed up this request with a memorandum addressed to the Commander-in-Chief in which he quoted the Prime Minister’s telegram, referred to 10 other AIF units (not including units serving in Tobruk) distributed in commands other than Australian and requested their return to AIF formations. The staff of General Headquarters promptly made plans for the relief of these units, which it was proposed to complete by mid-July. General Smith, Wavell’s chief of staff, submitted to Blamey the proposed reply of General Headquarters to his request and pencilled on it a note:–

Deputy C-in-C – Do you approve of suggested reply in para 4 to GOC 2nd AIF?!7

On 26th June General Blamey telegraphed to Mr Menzies a reply to a series of questions from him, including one on the future policy with regard to Tobruk. “Are you satisfied,” Mr Menzies had asked, “that garrison at Tobruk can hold out? Should we press for evacuation or for any other and what course?” Blamey replied that he was satisfied that Tobruk could hold out for the present. He assured Mr Menzies that the problem of evacuating Tobruk, should it become necessary, was being considered; the navy was of the opinion that evacuation was practicable. There was no need to press for action since he had already asked for a plan. Colonel Lloyd, then in Cairo, did not feel any immediate anxiety.

The Government’s curt reminder to General Blamey of its policy that all AIF units should serve in the Australian Corps was further discussed by him in a letter written on 27th June to the Minister for the Army. He told Mr Spender that he hoped soon to have all the AIF under Australian command. Existing conditions, he said, prevented its complete assembly in one force, but he hoped to have it in four main groups – Syria under Lavarack – Tobruk under Morshead – and the rest in Palestine (fighting organisations under Mackay and the remainder under Base Headquarters) “with the long view of ultimately getting it all together in Palestine or Syria”. He said that, as Deputy Commander-in-Chief, he was having a

very definite influence in restoring a proper sense of formation organisation, not only in the AIF but in all the forces in the Middle East. Referring to the proposal to establish an Anzac Corps, he commented that it would be difficult to ensure that the AIF would be kept under one command if the second corps were formed. Although this could be made to appear as an objection to “implementing” a second corps for some time, it need not be so at all: there was no longer any real objection to placing other Imperial forces under an Australian commander.

Some progress was made in terminating the small detachments of Australian units, but in mid-July it had still not been found possible to assemble in one place even one of the three Australian divisions with all its units. Their training as complete formations could not be undertaken.

It is clear from Blamey’s communications to the Prime Minister and Mr Spender in the last week of June that he was not then contemplating an early relief of the 9th Division nor is there any evidence that he had considered requesting its relief until his senior medical adviser, Major-General Burston,8 represented to him that there had been a physical decline in the condition of the Tobruk garrison.9 Burston’s opinion appears to have been based in the first place on his own observation that a few men from the garrison whom he had encountered in Cairo appeared to be considerably underweight; but investigations confirmed the impression. When General Morshead visited Cairo from 2nd to 8th July Blamey sought his views; Morshead told him that the garrison’s capacity to resist a sustained assault was diminishing. Morshead’s diary indicates that he lunched with General Burston and Colonel Fairley10 on 3rd July. It is probable, though concrete evidence is lacking, that Blamey made up his mind to request the relief about that time. The fact that the Syrian campaign was drawing to its close – the armistice was initialled on 12th July – may have made the moment seem most opportune for drawing the AIF together.

General Blamey’s decision should be regarded against the background of the current war situation in the Middle East and elsewhere. If a seaborne relief were to be effected, it was desirable to undertake it at a time when the garrison was not under threat of imminent assault. The drive of the German armed forces into Russia continued unchecked. Hitler, it seemed, had taken in the flood a tide in the affairs of nations that led on to fortune. Not even the British Chiefs of Staff expected that onslaught to be long withstood; indeed not until the British winter offensive to relieve Tobruk was under way would any reliable sign be discerned of Russia’s capacity to block the German armour’s onrush and throw the intruders back. If Russian resistance broke, no longer would Germany be restrained from reinforcing her army and air forces in the Middle

East theatre by the exigencies of providing for commitments on the Eastern front. Whether the British would succeed in building up, before the threat to Tobruk was renewed, a sufficient superiority of force in the desert to take the initiative; if so, when the new offensive would be launched; whether it would then succeed: these were questions to which the answers could not be wrested from an enigmatic and comparatively distant future. On the other hand it seemed unlikely that in the immediate future either side would be able to assemble the resources for a major operation. If the present opportunity to effect a seaborne relief were not seized, no definite limit could be set to the 9th Division’s expectant term of front-line service and incarceration.

On 18th July, in a letter to General Auchinleck of which the full text is set out below, General Blamey proposed that the Tobruk garrison should be relieved. It will be noticed that the first paragraph propounded an argument for relief of the entire garrison on the ground of the troops’ physical decline, while the second paragraph advanced an additional reason for the relief of the garrison’s Australian component.

1. It is recommended that action be taken forthwith for the relief of the Garrison at Tobruk. These troops have been engaged continuously in operations since March and are therefore well into their fourth month. The strain of continuous operations is showing signs of affecting the troops. The Commander of the Garrison informs me he considers the average loss of weight to be approximately a stone per man. A senior medical officer, recently down from Tobruk, informs me that in the last few weeks there has been a definite decline in the health resistance of the troops. Recovery from minor wounds and sicknesses is markedly slower recently.

It may be anticipated that within the next few months a serious attack may be made on the Garrison, and by then at the present rate its capacity for resistance would be very greatly reduced. The casualties have been considerable and cannot be replaced.

It would therefore seem wise to give consideration immediately for their relief by fresh troops and I urge that this be carried out during the present moonless period. The relief requires movement of personnel only.

2. With reference to the Australian portion of the Garrison; the agreed policy for the employment of Australian troops between the British and Australian Governments is that the Australian troops should operate as a single force.

Because the needs of the moment made it necessary, the Australian Government has allowed this principle to be disregarded to meet immediate conditions. But it nevertheless requires that this condition shall be observed, and I therefore desire to represent that during the present lull in active operations, action should be taken to implement this as far as possible. This is particularly desirable in view of the readiness the Australian Government has so far shown to meet special conditions as they arose.

3. The Australian Corps is probably the most completely organised body in the Middle East and will certainly be required for operations within the next few months.

The 6th Australian Division has been sorely tried, having fought continuously through Libya, Greece and Crete, and a considerable proportion of its units had to be detailed for Syria.

The 7th Australian Division has just completed the campaign in Syria and has suffered losses which have to be made good. It cannot be completed until 18th Australian Infantry Brigade, now in Tobruk, is relieved to join its own division and the 7th Australian Cavalry Regiment is freed from Cyprus.

The 9th Australian Division at Tobruk has been continuously in operations since March and has suffered considerable losses.

The drain on reinforcements has been heavy.

This Corps probably will be required in a month or two for further operations. If it is to render full value in accordance with the wishes of the Australian Government and as agreed by the British Government, it is necessary that action be taken early for its re-assembly in order that the formations and units may be thoroughly set up as quickly as possible.

4. The New Zealand Division has been through one campaign and is up to full strength.

The South African Division, under existing law, is confined to operating in Africa. It has had a prolonged rest from active operations.

I can see no adequate reason why the conditions agreed between the Australian and United Kingdom Governments should not now be fulfilled.

5. A copy of this memo is being despatched to the Prime Minister of Australia.

Blamey told Mr Menzies, in a cable sent the same day, that, in view of the garrison’s continuous front-line service since March, he was of opinion that its fighting value was now on the decline and he was pressing for its relief by fresh troops, which could be made available “if will to do so can be forced on Command here”; he was also pressing for the collection of the AIF in Palestine, to which the only real obstacle that could not be overcome was unwillingness to do so. It was most desirable, he said, that after any series of operations the troops involved should be given a respite to refresh them and to provide an opportunity to restore discipline and re-equip them. He suggested that Mr Menzies should take strong action to ensure the collection of the AIF as a single force.

Mr Menzies cabled Churchill on the 20th:–

We regard it as of first class importance that now that Syria Campaign has concluded Australian troops in Middle East should be aggregated into one force. This would not only give an opportunity refreshment, restoration of discipline and re-equipment after strenuous campaign but would also give immense satisfaction to Australian people for whom there is great national value and significance in knowing that all Australian soldiers in any zone form one Australian unit. This principle was fully accepted by both United Kingdom Government and ours when troops first despatched to Middle East. Problem has a particular bearing on garrison at Tobruk which has engaged in operations since March and is therefore in position of a force with continuous front-line service over a period of months, a state of affairs which must result in some decline of fighting value. If they could be relieved by fresh troops, move of personnel only being involved, reaggregation and equipment of Australian Imperial Force in Palestine would then present no major difficulty. I would be glad if you could direct British High Command in Middle East along these lines. The comparative lull now obtaining in Libya seems to make this an ideal time for making above move to which we attach real and indeed urgent importance.

The Chiefs of Staff telegraphed the text of Mr Menzies’ communication to General Auchinleck with the comment:–

Full and sympathetic consideration must clearly be given to the views of the Australian Government. At the same time we realise, as no doubt does the Australian Government, that the grouping and distribution of divisions must be subject to strategical and tactical requirements and to what is administratively practicable.

General Auchinleck replied that the two questions – the relief of the Tobruk garrison and the concentration of the AIF – were under consideration.

He fully agreed as to the desirability in principle but there were many difficulties, which he hoped might be overcome.

General Auchinleck had succeeded General Wavell in the Middle East Command on 5th July. Almost immediately he found himself subjected to pressure from Mr Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff to resume offensive operations in the desert at the earliest possible moment. Wavell had advised that no offensive would be practicable for three months but this was overlooked as soon as he was replaced by the commander who had struck Mr Churchill as more forward in outlook. One of Auchinleck’s first decisions – the choice of the 50th Division to garrison Cyprus (which was associated with the promised relief of the 7th Divisional Cavalry Regiment) – caused Churchill much annoyance. On 15th July Auchinleck informed the Chiefs of Staff that he doubted whether it would be possible to hold Tobruk after September. On 19th July the Chiefs of Staff replied that they assumed therefore that any offensive to regain Cyrenaica could not be postponed beyond that month. Churchill added his own comment.

If we do not use the lull accorded us by the German entanglement in Russia to restore the situation in Cyrenaica, the opportunity may never recur. A month has passed since the failure at Sollum, and presumably another month may have to pass before a renewed effort is possible. This interval should certainly give time for training.

Auchinleck refused to be hustled. Churchill was perturbed by the “stiffness of his attitude” and decided that the stimulation of personal contact was required to impart a less cautious mood.

On 23rd July (the day on which the Chiefs of Staff telegraphed to Auchinleck the text of Mr Menzies’ message) the British Prime Minister invited the Middle East commander to come at once to London to “have a talk”, adding that Blamey could act for him in his absence. Knowing that in London he was to be faced with strong pressure to mount in September another operation to relieve Tobruk by land, Auchinleck, even if he had so wished, could hardly have acceded, on the eve of his departure, to Blamey’s request that the entire Tobruk garrison should be relieved by sea. Such a relief could not have been completed before late September. Auchinleck agreed, however, that as a first step the 18th Brigade might be brought out, thus enabling both the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions to be reconstituted as complete formations, and also that the possibility of a more extensive relief should be studied. By good fortune to replace the 18th Brigade there was available an eager, excellently trained brigade of Polish troops, the 1st Carpathian Brigade. Originally allotted to the expedition to Greece, this formation had been held in reserve since the loss of Cyrenaica.

General Auchinleck arrived in London on 29th July. On 1st August he telegraphed Blamey that General Sikorski, head of the Polish Government in exile, agreed to the use of the Polish contingent as part of the Tobruk garrison, but subject to certain conditions; if these could not be fulfilled Blamey was to wire alternative proposals. Blamey replied on the 2nd that the conditions would be fulfilled; the meeting of the Commanders-in-Chief

on that day had decided that a relief of the Tobruk garrison by the 6th British Division and the Polish contingent would be carried out during the moonless periods of August and September, two brigade groups being relieved each period. On 4th August, however, Blamey telegraphed Auchinleck again to say that, after further discussion with Admiral Cunningham and Air Marshal Tedder, he had agreed that the relief would be deferred till September, when a greater scale of air protection would be available.

Meanwhile Mr Menzies, who knew nothing of these interchanges, was perturbed that he had received no response from Mr Churchill to his telegram of 20th July. He telegraphed again on 7th August, asking for an early reply. After mentioning the Australian War Cabinet’s concern at the Tobruk garrison’s decline in “health resistance” and recalling that all three Australian divisions had latterly been much engaged in operations – the 9th at Tobruk continuously since March – he concluded:

As fresher troops are available I must press for early relief of 9th Division and re-assembly of Australian Corps.

The text of this message was telegraphed to General Blamey, who hastened to reassure the Australian Prime Minister. “Policy agreed to and plans prepared,” he replied. “As scale air protection available not yet sufficient have felt obliged to agree to postponement to September, which will also give advantage of longer nights.” From London the response was also reassuring. Viscount Cranborne, the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, replying in the absence of Mr Churchill (who had gone to the Atlantic meeting with Mr Roosevelt) told Mr Menzies that General Auchinleck had been directed to give full and sympathetic consideration to Menzies’ first telegram. Auchinleck was now in London and Menzies’ second telegram had been discussed with him. “We entirely agree in principle that the AIF should be concentrated into one force as soon as possible,” he said, “and General Auchinleck has undertaken to see to this immediately on his return. He does not anticipate any difficulty except in regard to Tobruk. He is as anxious as you in this connection to relieve this garrison.”

–:–

By the end of the third week of July Morshead, as yet uninformed of these negotiations, was contemplating further operations to pinch out the enemy’s salient. He intended that Godfrey’s brigade should attack and capture both shoulders of the Salient simultaneously. The ultimate object, according to the divisional report, was to exploit their capture and thrust the enemy from the perimeter, but this final development had not been planned as an immediate follow-up operation.

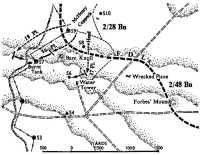

It is not certain when Morshead reached the decision that Godfrey’s brigade should mount that attack, but arrangements for preliminary moves that may have been intended to set the stage were put in hand on 20th July. Reconnaissance parties from Lieut-Colonel Lloyd’s 2/28th Battalion spent that day with Lieut-Colonel Windeyer’s 2/48th Battalion

which held the perimeter from north of the Derna Road to the northern edge of the Salient. The 2/28th was destined to mount the attack on the northern shoulder from that sector, and the 2/48th, which was to carry out a subsidiary but important task on the left flank of the 2/28th, badly needed a rest. Two days later Lloyd’s battalion relieved Windeyer’s battalion, which came back to the Blue Line in the western sector. “The C.O. has been prevailed upon to take a spell,” wrote the diarist of the 2/48th. “The men are tired today after their period of 3 weeks in the line.”11

On 21st July Morshead visited his four brigade commanders and his headquarters issued orders to the 20th Brigade to relieve the 18th, which Morshead always liked to have in reserve for counter-attack in critical times. The 20th was to take over from the 18th on the southern sector on 27th July.

On the same day divisional headquarters issued general orders to all brigades to carry out raids relentlessly (but not without purposeful intent) and to endeavour to bring back prisoners and other identifications. From 22nd July the 2/28th Battalion, now holding the positions against the northern shoulder of the Salient, and the 2/43rd, which held the front opposite the southern shoulder, embarked on a systematic patrolling program designed to pin-point enemy positions, plot minefields and discover approach routes, along some of which minefields were devitalised. Soon orders for the capture of a prisoner were brought to bear upon these two battalions with pressing urgency. In the fourth week of July they sent out on an average two fighting patrols of platoon strength per night on this and other missions. Lieut-Colonel Conroy’s 2/32nd Battalion on the right of the Salient also patrolled vigorously on its right flank.

The divisional report implies that it was found from these patrols “that the enemy were not holding their positions in great strength, and that extensive use was being made of mines and booby traps”. A detailed scrutiny of the patrol reports has not yielded confirmation of the first part of this statement. The notion seems to have persisted from an impression gained at the beginning of June, when the 20th Brigade held the Salient line. All battalion commanders agreed at a conference at Murray’s headquarters on 7th June that the enemy was thinning out his foremost defended localities “to straighten his line”. These observations, however, were consistent with a falling back on a strong line of new constructions while some positions on the previous front continued to be lightly held. On 8th July, when Crellin’s 2/43rd Battalion relieved Ogle’s 2/15th Battalion on the left of the Salient line, Ogle reported:–

It is considered that the enemy is not holding the Salient by strength of numbers but by strength in automatic weapons and mortars. He is protected by the antipersonnel mines which he has sown. ...

The belief that the enemy might be thinning out was sharply revived on the night of 25th–26th July when, after an unusually quiet day, patrol

from the 2/28th and 2/32nd Battalions found that some previously occupied enemy outpost positions were vacant. A patrol from the 2/32nd searched the Water Tower (where Sergeant-Major Morrison had held out during the attack by the 2/23rd), and found that area and the ground to the west unoccupied. When this patrol’s report was received, Conroy sent out further patrols, which reported no signs of movement in positions known to have been previously occupied. Simultaneously, from the 2/28th Battalion, Lance-Corporal Monk12 and three men searched the area west of the Water Tower and found it unoccupied. Brigadier Godfrey’s reaction to these reports was quick, if optimistic Colonel Lloyd was to send out a patrol at first light “to attack and capture” Post S7, and Colonel Conroy another, to seize S6 if unoccupied.

Lieutenant Taylor13 and 10 men from the 2/28th Battalion set out for Post S7. Without difficulty they reached the mouth of a re-entrant leading up the escarpment on the east side of S7 but were then engaged by machine-guns posted on the slope ahead. The fire quickly thickened and the attempt had to be abandoned, the patrol members only extricating themselves slowly and with great difficulty.

Lieutenant Brownrigg14 took out from the 2/32nd Battalion the patrol to seize Post S6 if unoccupied. Brownrigg and nine men reached the vicinity of the Water Tower without incident just before 6 a.m. but fire from the south soon afterwards indicated that the area of the objective was held defensively. Brownrigg’s patrol spent the day observing from close to the Water Tower.

On the night of 25th July, an Italian prisoner was taken in a raid by British commandos near the coast west of the perimeter, but the great need was to get a German prisoner from the Salient. This was accomplished two nights later by a patrol from the 2/43rd Battalion led by Lieutenant Siekmann.15 The patrol challenged and engaged a German working party coming down a road some 1,500 yards from the Australian positions. Several Germans were killed, but two fled. Sergeant Cawthorne,16 though wounded twice, gave chase, killed one of these and captured the other. Enemy parties attempted to intercept the patrol as it returned, but were eluded. Questioning of the prisoner established that the Salient front was manned by the same three German lorried infantry battalions as before, and yielded information concerning the nature of the defences.

Morshead commented on the capture in a letter written to General Blamey next day:–

From a German corporal captured in a particularly good effort by a fighting patrol of the 43rd Battalion early this morning, we learned that even the Germans

in the Medauuar sector – it is no longer a salient – are apprehensive of our activities, so much so that they stand-to throughout the whole night, and have done so for the past week. We are planning an attack on posts S7 and S6 on the German left flank and R7, R6 and R5 on their right flank in the near future.

Two days before this, Colonel Lloyd, Morshead’s chief staff officer, had been summoned to Cairo. No record survives of the message summoning him, or of how it was conveyed to Morshead. Circumstantial evidence supports the inference that Morshead was aware that Blamey had broached the question of a relief but did not know what course the discussions had taken. Not yet an advocate in the controversy, Morshead, in the letter just quoted, spoke with pride of the garrison’s spirit. He told Blamey:–

The troops are in wonderful heart, their morale never higher – the nightly raiding parties and fighting patrols, as well as the daylight carrier sorties, have contributed to this. Then the marked improvement in rations and canteen stores and the gifts of the Comforts Fund have also helped.

The men understand the position perfectly, and are enthusiastic in their appreciation for all that is being done.

On the night of 30th July, the 2/48th Battalion relieved the 2/32nd Battalion, which then came into brigade reserve. Two nights later, “A” Company of the 2/32nd Battalion relieved “D” Company of the 2/28th, and became the reserve company in the 2/28th’s sector thus freeing the 2/28th company from defence duties for employment in the projected attack.

The general plan for the operation by Godfrey’s brigade was to attack the shoulders of the Salient by night from right and left simultaneously. In more detail the plan is well described in Morshead’s own words:–

The plan for the 43 Bn was to capture Post R7 with two platoons, the third platoon occupying a position south of that post and outside the wire to deal with counter attacks. A fourth platoon acted as a carrying party. In the event of this attack being successful, the second phase would follow – this being the capture of Posts R5 and 6 by the covering platoon and one of the platoons from R7.

The plan for the 28 Bn was the capture of (a) Post S7 by two platoons, one attacking from the west and the other from the north and (b) Post S6 by one platoon.

Plans were made too for the exploitation of success by the attacking coys and also by the 32 Bn in reserve. The artillery support was by thirty-six 25-pounders, two 18-pdrs, nine 4.5 howl, eight 75-mms, four 105-mms, two 149-mms, two 60-pdrs and the “bush artillery”. In addition, all available mortars including seven 81-mms and 4 platoons MG were used.

The diarist of the 107th RHA, whose commanding officer was a critic of attempts to retake the Salient, described the operation more pithily:–

This was a two platoon attack at each end ... supported by twenty-one troops of artillery!

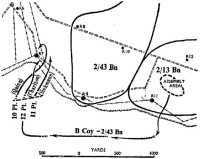

The operation was thoroughly planned. Captain McCarter’s17 company of the 2/43rd Battalion was relieved by the English commandos for three

days to practise the operation on a model of R7 which had been built into the Green Line defences of the fortress; Morshead watched them rehearse and was “much impressed by the manner in which they carried out the practice and the careful thought that had been given to the plan”18 Unfortunately the company of the 2/28th Battalion to mount the attack on the right shoulder, under the temporary command of Captain Conway,19 could not be afforded an opportunity for similar practice because the company of the 2/32nd which had to take over its front-line defence duties could not be made available to release it in time.

Of the two parallel fronts embaying the Salient in a double arc, the enemy line, on the inner side of the curve, was the shorter. Three German infantry battalions held the Salient against two Australian battalions and the left flank of a third. A battalion of the 104th Lorried Infantry Regiment held the front opposite Lloyd’s battalion, the II Battalion of the 115th Lorried Infantry Regiment that opposite Crellin’s battalion, with the I Battalion of the latter between. Depth was given by some Italian troops ensconced in rear, but the inference from patrol reports was that their main function was to construct defences.

For three months the enemy had laboured tirelessly to improve the Salient fortifications. Patrols brought back reports of working parties, both Italian and German, almost every night up to the time of the attack. Without air photographs it was impossible to pinpoint the defences behind the outer fringe. Morshead commented on this to General Blamey:–

Well before the operation I asked 204 Group for photographs of Medauuar, sent the usual reminders, and eventually the photographs were taken two days before the battle. I asked that they be dropped here and they agreed to so do on 1st August. I understand that they were flown up on that date, but the releasing apparatus failed. They were dropped next day, and found to be of the wrong area. However there are indications that from now on we can expect some cooperation from the Air Force.

It was known nevertheless that this tenaciously guarded territory was interlaced with earthworks set in minefields studded with anti-personnel mines. The sangars housing the German machine-guns were strongly built from sandbags and covered with earth camouflaged with tufts of coarse grass.

They rise from the ground to a height of about 4’6” with crawl trenches connecting each. MGs are fired through loopholes about 6” from the ground. ...20

Where Lloyd’s battalion was to attack, the terrain greatly favoured the defence. The attackers’ problem was brilliantly analysed a fortnight later in an appreciation written by Major T. J. Daly, Wootten’s brigade major.

Ground

(a) The ground over which the attack must be made is in the form of an escarpment at the top of which is the objective and at the bottom of which are our FDLs. The enemy occupies a line running along the top of the escarpment which peters out about 1,000 yds. East of Post S6 but continues for a considerable

distance to the West of S7. This ground formation enables the enemy to observe all the ground between our FDLs and the objective from both flanks and his weapons are so sited as to enable him to produce heavy enfilade fire from MGs while the narrowness of the immediate front enables him to cover the area most effectively with arty and mortar fire. Between our FDLs and the objective there are no covered lines of approach. A number of small wadis provide slight protection for part of the way against flanking MG fire but these are thoroughly covered by mortars.

It is obvious, therefore, that failing the complete neutralisation of the enemy’s defensive fire it will not be possible to advance over this country in daylight or, having advanced, to bring further troops across it.

(b) The capture of the objective presents us with a linear posn which, owing to the nature of the ground and the impossibility of either giving direct supporting fire or securing observation from our present posns, is virtually without depth. In addition it will be subjected to heavy fire from both flanks which, unless subdued, will also effectively prevent communication with the rear and the bringing up of necessary reserves and stores. Consequently it will be necessary to exploit fwd from these posns sufficiently far to give depth necessary to hold these posns, which from our present knowledge, would appear to be to the general line of the Acroma Rd. In addition exploitation to the East at least as far as the wrecked plane will be necessary in order to protect the left flank of the captured posn and to prevent it forming a narrow salient jutting out towards Ras el Medauuar. This will require a heavy arty preparation before being undertaken. Simultaneously, a front must be formed facing West to meet any threat from that direction.

Time and Space

... In an attack carried out under these conditions exploitation during the hours of darkness must necessarily lead to an almost complete loss of control and it is doubtful if our force would be able to withstand a determined counter-attack at first light. On the other hand failure to exploit would greatly increase the difficulty of holding a line S6-S7 on the following day. ...

Opposite Crellin’s battalion the terrain afforded the German defence little assistance except commanding observation from the gentle, concave slope leading up to Medauuar; but it was known that the defences were intensively developed. The approach was barred to tanks by a continuous minefield with a screen of listening posts in front. The prisoner taken on 27th July thus described the defences:–

Behind the minefield is a continuous belt of barbed wire, and behind the wire are more holes occupied by from 2 to 4 men. These holes are camouflaged with bushes to fit in with the surrounding country, and are all connected by crawl trenches. They are close together, varying from 3 to 4 metres apart to 20 and even 30 metres apart, depending on the nature of the ground. ... The strongposts are surrounded by barbed wire, and Posts R7, R6 and R5 are held by about 30 men each, one company holding Posts R7, R6 and part of R5 and intervening fieldworks, while the rest of the R5 garrison is from a reserve company.

Lieut-Colonel Lloyd, whose battalion’s task of capturing S6 and S7 with one company was perhaps the more formidable of the two, was the most widely experienced of the Australian battalion commanders in Tobruk. After hard service in the first AIF in which he had reached the rank of captain he transferred in 1918 to the Indian Army, with which he served in the Second Afghan War and from which he retired in 1922. He returned to Australia and in 1936 had become a major in a militia battalion. Lloyd’s plan was to employ two platoons in direct assaults on

each post while a third gave right flank protection. The latter was to move outside the perimeter and engage the sangars on the escarpment west of S7, one platoon was to assault S7 from the area of S9 and the third S6 from the area of S8. On the left a platoon from the 2/48th, moving in rear of the platoon attacking S6, was to seize the Water Tower and the sangars to the east of it, while farther to the left that battalion’s forward companies were to engage with fire the enemy positions on their front (within the arc S4 to R2). The 2/48th was to be ready on 10 minutes’ notice to swing forward the right of its front to a new alignment linking the Water Tower with the existing front at Forbes’ Mound. This in turn would require the capture and occupation of an enemy strongpoint beyond the wrecked plane and of another about 300 yards south-west of Forbes’ Mound. The task of wresting, from a thoroughly alerted foe, the foremost fringe of a defensive zone developed in depth was a forbidding one.

Lloyd had one company plus one platoon available to capture the two posts that Evans had earlier failed to take in a battalion attack (albeit hastily mounted) using initially two companies. His plan differed from Evans’ assault in two respects: on the one hand by providing for attack on a broader front, with a platoon neutralising the outer flank of each post attacked, but on the other hand by allotting one platoon to the direct assault on each post as against one company in Evans’ operation.

For the attack on the southern shoulder Crellin’s plan was that his assault company should use two platoons to attack R7 in converging assaults from right and left, while one platoon was to be held in reserve to meet enemy counter-moves from flank or rear or, if the operation developed propitiously, to exploit initial success by a further advance. The attack was to be made from a start-line laid outside the perimeter to the south of the objective. A platoon from another company was to carry bridges for crossing the anti-tank ditch, give flank support southward during the assault and be ready to assist in consolidation.

Crellin’s assignment included exploitation by his assault company, on success of the first phase, to capture Posts R6 and R5, if there was a reasonable assurance of success. Godfrey’s orders adopted the unusual but sensible course of requiring the company commander himself to decide whether that should be undertaken. If it were, the two flanking companies of the 2/43rd and, farther right, the left company of the 2/48th were each to push out a platoon to establish an outpost line as close as possible to a road that ran north-west and south-east across the enemy territory in front of S4 on the right, and R4 and R6 on the left. A feature of Crellin’s plan was the provision for quick delivery of consolidation stores by five carriers, a trailer and an ammunition truck (with a reserve truck standing by). These were to assemble near R9, whence they would be able to reach R7 within five minutes of the call forward. They were to take forward two anti-tank guns and a 3-inch mortar, with their crews, as well as ammunition, wire, shovels and other stores.

Tanks were not to be used in either assault, for fear of prejudicing surprise, but two squadrons of cruisers and two troops of infantry tanks

The 2/28th Battalion attack, 2nd–3rd August

were to stand by under Godfrey’s command to deal with counter-attacks or assist exploitation.

For Lloyd’s assault artillery support was to be provided by the 51st Field Regiment less one section, one battery of the 107th RHA and three troops of the 2/12th Field Regiment; for Crellin’s assault by “B/O” Battery, one battery of the 107th and one battery and one troop of the 2/12th. Lieut-Colonel Goodwin was in charge of counter-battery fire. Four platoons of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers were to provide machine-gun support, three with pre-arranged fire tasks during the assault.

The zero hour for both attacks was 3.30 a.m. on 3rd August. Silently, below the Salient’s steep north shoulder, Captain Conway and his platoons, Lieutenant Overall with his sappers, and the Intelligence section men who were to lay the start-lines, got ready in the middle of the night. Conway’s company had been relieved the night before from local defence duties by a company of the 2/32nd Battalion.

Lieutenant McHenry’s21 platoon was the first to move off, an hour before zero, followed by the rest 15 minutes later. The moon, which was three-quarters illumined, set while they were going forward to the places chosen for their start-lines. Captain Conway, who was to move into S7 when the success signal was shot, went to his battle headquarters at a feature called Bare Knoll.

For the attack on S7 McHenry’s platoon was to advance from a start-line west of S7 outside the wire and give supporting fire while Lieutenant Coppock’s22 platoon executed a direct assault from a start-line near the bottom of the escarpment. When Coppock fired the success signal the engineers with McHenry were to blow the perimeter wire and McHenry would join Coppock.

All were ready when the bombardment from more than 60 guns opened up five minutes before zero. Enemy defensive fire from all arms sprayed down on the approaches before the platoons moved off. Coppock and his men advanced up the escarpment. Fire slashed them from front and sides, while “jumping jack” mines burst out of the ground they trod. The few survivors who reached the top, nearly all wounded, gave covering fire while the sappers moved in with their bangalore torpedoes, blew the

wire with a resonant boom and placed their bridges across the anti-tank ditch. Coppock and three men got across to the post, killed four Germans and took the surrender of six more, only two of whom were unwounded.

The Very light signal to call in McHenry’s platoon should then have been given, but Coppock was unable to fire it because the sack carrying the cartridges had been shot from his back. A runner was sent to Conway but did not reach him.

Others of Coppock’s platoon managed to get into the post. But from outside Lance-Corporal Anderson,23 now twice wounded, continued firing with his Bren gun on the enemy sangars, until Coppock himself went out and dragged him in. About two hours later he died. Stretcher bearers toiled to get the wounded back to S8. The enemy lit up the area at short intervals with flares and began to close in. Coppock, dazed and wounded, when no help came set out to find Conway. Two signallers, White24 and Delfs,25 arrived having laid a line to the post, worked on a telephone but found the line dead.

Lance-Sergeant Ross26 of the 2/13th Field Company, a born soldier and leader, who had joined in the work of removing the wounded, returned afterwards to the post to remove the bridges and assist in its consolidation. He found there a dozen men of whom only about five (including two signallers) were fit to fight.

Meanwhile from outside the perimeter Lance-Corporal Riebeling’s27 section of McHenry’s platoon had given close support. But when the night moved towards dawn and no light signal came, McHenry withdrew his men within the perimeter and went to report to Conway.

The attack on S6 had proceeded with even less success. Lieutenant Head’s28 platoon reached the escarpment with few casualties. Behind it followed a platoon of the 2/48th Battalion under Sergeant Ziesing,29 which then seized the weapon-pits and sangars east of the Water Tower without much trouble. But thenceforward Head’s platoon was mown down by bullets, bombs, shells and mines. The engineers were shot before they could blow the wire round the post. Head, with the survivors following, pressed on but stepped on a booby-trap as he reached the wire and was wounded in the neck and legs. He had now only eight men with him, some of them seriously wounded. No platoon, no other men, stood by, waiting on his success signal, to reinforce his strength. Ought Head still have ordered his dwindling band to strive to reach that post through its

uncleared obstacles and mines, subdue its garrison and, if yet some survived, to hold out if possible in case miraculous help might come in time? Their lives were his to command. Doubtless they would have done his bidding. Head led them back.

Colonel Lloyd, who had established an advanced headquarters on top of the escarpment between S12 and S13, waited long and in vain for the success signals. An hour passed, and another. No word came back. At last the passage of time itself, with not a single report received, seemed to spell failure. Accordingly he reported to Godfrey about 5 a.m. that both attacks had failed.

The carrying parties waiting to take stores and ammunition up to the captured posts, which had been assembled on the exposed shelf round S10, were now drawn back to cover because of the approach of dawn. Godfrey dismissed the waiting tanks, which then lumbered slowly back on their journey of some miles to their harbour. At 5.15 a.m. Windeyer was informed of the failure of both attacks by Godfrey’s headquarters. Windeyer, doubtless with some feelings of relief, stood down the platoons waiting to advance his front to the intended new line and recalled Ziesing’s platoon from the Water Tower. But at 5.20 a.m., unmistakably above Post S7, a green light burned in the sky, then a red, then another green. Fifteen seconds later came the same succession of lights – the signal for success at S7.

Conway had refused to infer failure from negative evidence; he had gone forward from Bare Knoll before dawn to find out the situation for himself. So Coppock, returning, had missed him at Bare Knoll; McHenry also. Coppock in his wounded, dazed condition subsequently became lost; McHenry went back to S9. Most of McHenry’s platoon then moved down to the regimental aid post at S12. But Conway reached S7 with his sergeant-major and two other men, having meanwhile lost two men as casualties. Finding the post occupied by his own men, he fired the success signal.

Lloyd, who had no reserves for the attack and whose carrying parties had gone back, now attempted to get a platoon from the relieving company of the 2/32nd to reinforce the post and gave orders for stores to be taken forward in carriers. Learning that McHenry had returned, Lloyd also instructed him to go to S7 with the men at hand. McHenry with his platoon sergeant and two of his men set off at once, carrying more than 2,000 rounds of ammunition, and reached the post before dawn. But the 2/32nd platoon and the carriers bearing stores were not so quick off the mark; meeting with a concentration of artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire laid down on the approaches, they could not get over the escarpment to the post. A carrier was disabled and the stores were dumped in a wadi 300 yards from S7.

About 6.45 a.m. it was observed from Lloyd’s battle headquarters that the area of S7 had been smoked by the enemy. In the captured strongpoint Conway and McHenry had only nine men fit to fight. What happened

there, after Conway arrived, was described in a statement taken from Signaller White next day:

The sapper, L-Sgt Ross, then rearranged the sandbags. He pulled out bags on his side and instructed us where to pull out and rearrange the bags so as to be able to fire and have protection. We could see the positions of the snipers – we arranged the bags so that we could fire at them.

Dawn broke at about this time.

The sapper took me and Sig Delfs to the other end post. ... Lieut McHenry came to this pit with a Bren and two men were between us with rifles.

The sapper came back to the north pit. There were two of us and the sapper in this pit. From this point there was a burnt-out tank on the right.

Just after dawn the Germans counter-attacked. They were seen coming out of a wadi to the east and moving south-westwards, whence they attacked from west, south and east, under covering fire from near-by sangars. White thus described the attack:

At about 0600 hrs., the enemy came up the fence from my right – they scrambled through the fence and made for the burnt-out tank. The tank was about 150 yards to the west from the post. ... They moved up in small groups and we engaged them. They went around the tank and came quickly towards us – all were knocked down – only about two crawled back through the wire. When this was taking place there was very heavy MG fire from a wadi from the east to the south.

The sandbags were being cut by fire and the sand draining on to the Bren prevented it from firing more than single shots. I was using a German machine pistol which stopped for the same reason. I then used my rifle. As they were coming from behind the tank in twos and threes, single shots were enough. The sapper got a flesh wound from a bullet in the forehead – went below and dressed it and returned and continued firing.

The counter-attack was beaten off. German stretcher bearers later came out and Conway permitted them to collect their wounded. This was observed from Lloyd’s advanced headquarters about 9.30 a.m. But Lloyd, a rugged soldier of the old school, who believed (though higher formation forbade) that commanding officers should direct the battle from the front line and that when his battalion was in action the cooks should fight beside the riflemen, interpreted this licence allowed by Conway as indicating not a truce but defeat. The impression was confirmed by one of his men who later crawled to the vicinity of the post and saw no movement.

The Germans did not allow the Australians similar liberties when attempts were made to remove the 2/28th wounded lying in Posts S9 and S10. Staff-Sergeant Lyall30 was granted permission to take a truck under the Red Cross flag to the posts, but although the Germans allowed the vehicle to approach, they fired on the occupants when they dismounted, preventing evacuation of the wounded.31

By mid-morning the result of the attack for the northern shoulder of the Salient, as it presented itself to Godfrey and Lloyd unable to peer through the battle-fog, was that S6 had not been taken and S7, though recaptured and briefly held, had again been lost. In the early morning,

The 2/43rd Battalion Attack on 2nd–3rd August

however, Godfrey had instructed the 2/32nd Battalion to send a second company to the 2/28th Battalion to come under Lloyd’s command so that he could continue operations if the situation proved better than was feared.

Of the 2/43rd Battalion’s attack on the southern shoulder, as of the attack in the north, the enemy appeared to be forewarned. Probably the assembling troops had been seen in the moonlight through field glasses before they moved out to the start-line. When the garrison’s bombardment began, enemy defensive fire came down as if by switch. Some of Captain McCarter’s assault force were hit before they moved off. The sappers, and Lieutenant Tapp’s32 platoon carrying the assault stores, reached the perimeter wire south of R7 with the bangalores and bridges. The wire was blown on time, but before the objective was reached the bridges were shattered by the enemy bombardment and the men carrying them wounded. Gusts of shell fire swept down on the area where the wire had been gapped; but the men, as a close observer said, “moved on as though it were a tactical exercise.”33 As the infantry approached the post, exploding grenades and booby-traps caused casualties to mount alarmingly. Some of the leaders were first to fall.

The left-hand platoon led by Warrant-Officer Quinn,34 going too far right, overshot the post, swung round and attacked it from the north. One section was silhouetted by flares and completely wiped out by mortar bombs. The other two sections got through the post wire and pressed on in dwindling numbers across a lethal mine garden to the edge of the unbridged, booby-trapped anti-tank ditch. Quinn had only seven others with him by the time he reached the ditch. Taking cover in it, they carried on the fight with grenades. Only three survived.

The route by which the left-hand platoon had attacked was that ordered for the right-hand platoon. The result was that the latter – Siekmann’s platoon – keeping to the right of Quinn’s, became closely involved in a fire fight with German flanking positions to the east and lost heavily. Siekmann extricated a handful of men and tried to get into the post but the defence weapons did not cease exacting their toll. Soon only two men

were with him, one badly wounded. Siekmann and the other fit man, crawling, dragged the wounded man back.

Twenty minutes after the fight began Captain McCarter instructed Lieutenant Pollok’s35 platoon, which was in reserve, to take up the attack. Led by Sergeant Charlton36 who had taken over command after Pollok had been wounded, the platoon practically re-enacted Quinn’s assault and suffered similar attrition. Charlton also reached the ditch with only seven men, fought on from there, but lacked the numbers to carry the assault into the post.

All three assault platoons had spent their force. Captain McCarter saw that it was impossible to make more progress and ordered a withdrawal. He gave the order about 50 minutes after the attack had commenced. McCarter, though he had been twice wounded, remained at the wire gap to keep control until all returning sections had passed through. It was an orderly withdrawal and many wounded were carried out.

It had been a costly attack. The attacking infantry had numbered 4 officers and 139 men; their battle casualties were 4 officers and 97 men. In addition the supporting troops incurred five casualties (4 engineers and 1 driver wounded). Four were missing. Twenty-nine infantrymen lost their lives.

Early next morning the attention of observers within the perimeter was arrested by an unusual spectacle. Vehicles from both sides, carrying the Geneva emblem, drove out unmolested into the bare, fire-swept Salient near R7. Sergeant Tuit,37 accompanied by stretcher bearers, took out the first vehicle from the 2/43rd at 7 a.m. Others followed in procession throughout the day. The Geneva Convention was seldom dishonoured in the desert war, though German Air Force attacks on hospital ships were frequent. On this occasion the Germans displayed a magnanimous solicitude for the wounded and their rescuers. They allowed the vehicles to approach within 200 yards, devitalised minefields to enable the wounded to be reached, brought out 4 wounded and 15 dead from the post, and gave Sergeant Tuit a drink. Tuit’s humanitarian mission recovered 5 wounded and 28 dead.

But around Post S7, which remained isolated throughout the livelong summer day, neither side ventured any move before dusk. All approaches to the post were under enemy observation and close-range fire; it was impracticable to make contact in daylight except by a major operation. A sergeant of the 2/32nd Battalion, who kept the post under constant observation for two hours, reported just before 2 p.m. that he was certain that it was occupied by the enemy.

Nevertheless it was essential to obtain positive confirmation. Colonel Lloyd’s plans for immediate action after dark were to send out two reconnaissance patrols. One, of five men under a senior NCO, was to ascertain

and report on the situation at S6, including the condition of the wire, and to “endeavour locate and arrange for any of our wounded of this morning to be brought in”. The other, to consist of an officer and six men including one NCO and one sapper and to be commanded by Lieutenant Taylor, was to move out through S8 and reconnoitre S7 and its immediate vicinity. Taylor’s task was – to ascertain and report upon the following:

(a) Who is in occupation of S7 and surroundings, i.e. whether enemy or own troops.

(b) If enemy, whether Italian or German.

(c) Estimate strength in weapons and manpower.

Should S7 be in our hands, then to contact and obtain full information as to numbers and names in occupation, commander etc. and other particulars that will help establish definite information.

Both these patrols were ordered to depart at 9.45 p.m. and to return not later than midnight. If Taylor’s patrol reported the post not occupied by the enemy, Captain Cahill’s38 company of the 2/32nd Battalion was to send forward a fighting patrol of one platoon to reinforce the garrison. Another company was to provide a platoon as a carrying party. Both the latter patrols were to be ready to leave at 10 minutes’ notice.

About 8.15 p.m. Colonel Lloyd received a direction from Brigadier Godfrey to send out a fighting patrol at last light and at once sent his adjutant, Lieutenant Lamb,39 to Captain Cahill to instruct him that the fighting patrol was to move out as soon as darkness fell. The sun set at 8.20 p.m. but still shone its beams onto a high, gleaming moon, which shed down its light with cruel brilliance. The 2/28th forward defences came under intense fire. The fighting patrol became disorganised.

At 9.50 p.m. the Very light signal by which Conway had notified the capture of S7 in the early morning was seen again above S7. Conway, who was under close attack, was calling for defensive fire but the signal was not so interpreted. About the same time the two signallers (White and Delfs) who had followed Coppock’s platoon into S7 when it was captured suddenly appeared at Post S8. Each brought a copy of a message from Conway, whom they had left about an hour earlier:–

Am at S7 with Lieut McHenry and 19 ORs including 9 very badly injured also some shock cases. The remainder of us are too fatigued to offer any resistance. We have seven prisoners here. We must have immediate help to hold Post S7.

Amn – have about 1,200 rds. 10 new men could hold the post.

Please send out help for injured. Have no bandages left. Require morphia tablets. Direct route 9-S7 appears clear. No enemy in vicinity except two snipers.

2020 hrs 3 Aug 41

R. A. E. Conway

Lieutenant Waring,40 in S8 when White and Delfs arrived, endeavoured unsuccessfully to take a section forward immediately to Conway’s help;

the enemy strafed the area as soon as the movement was perceived. Meanwhile a patrol that had gone out at last light from the 2/48th Battalion to the Water Tower area had approached S7; it returned to report that Australian voices could be heard. Lieutenant Beer of the 2/48th then took out a patrol with the intention of occupying S6 if it should be unoccupied. Lieutenant Taylor subsequently set out from the 2/28th Battalion on his mission to S7.

Colonel Lloyd then had to endure another long wait. It was not until 1.25 a.m. that he received the report from Taylor’s patrol. Taylor had seen about 50 enemy skylined on the northern side of S7 and inferred that the post was definitely in enemy hands, but Lloyd refused to accept this conclusion and ordered an attack for S7 by the 2/32nd men under his command. This was a difficult task to carry out in a moonlit area under continuous mortar bombardment with no place of assembly beyond the enemy’s observation. Eventually the move off was deferred until after moonset (3.45 a.m.) and got under way just before 4 a.m.

The attack was made by two platoons, with a third acting as a carrying party, but failed. Lieutenant Payne,41 whose platoon suffered 12 serious casualties in the assault, reached the wire but was there badly wounded in the stomach. Lieutenant Fidler,42 commanding another platoon, was mortally wounded. In all 30 serious casualties were incurred.

At 4.40 a.m. Lieutenant Beer’s patrol from the 2/48th, which was in the vicinity of S7 (his second patrol to the region that night), saw a green flare fired by the enemy. Thereupon all firing suddenly died down. The fight for S7 was over. Conway’s attack had been made by 135 men (including the attached engineers); of these 83 had been killed or wounded or were missing; the company’s fighting strength at dawn on the 4th was 4 NCOs and 28 privates. Conway had surrendered just before 11 p.m. when his ammunition was almost exhausted and the enemy having got into the anti-tank ditch surrounding the post was poised for a final assault.

Between 4th and 7th August the 18th Brigade relieved the 24th, which went into divisional reserve. On the night of the 8th the much tried 2/48th Battalion came into brigade reserve, the three forward battalions then being: right 2/12th, centre 2/10th, left 2/9th. Two nights later the 2/48th left the Salient, changing places with the 2/24th Battalion and becoming reserve battalion in the quiet eastern sector. Another unit to be allowed a well-earned rest was the 2/13th Field Company, which had been continuously in the Salient and western sector since May. It was replaced by the 2/4th Field Company on 12th August.

The months following the BATTLEAXE operation were a time of reconstruction and reinforcement for both the Axis and the British forces in Africa. When General Paulus reported back to the German Army Command

after the failure of Rommel’s assault on Tobruk in May, the German Army Chief of Staff, General Halder, conceived a means of controlling the African field commander whose proclivity for becoming committed beyond his allotted supply resources was proving so vexatious. General Gause was appointed, with Field Marshal Brauchitsch’s concurrence, “German Liaison Officer at Italian Headquarters in North Africa.” Gause arrived in Tripoli on 10th June but found General Gariboldi, the Commander-in-Chief in Africa to whom Rommel owed nominal allegiance, not complaisant. The inherent threat to Gariboldi’s illusory authority appears to have impressed him more than the intended curb on his intractable subordinate. Rommel, of course, was indignant, and protested to General Brauchitsch.

The stars in the Axis High Command firmament, however, favoured Rommel While Brauchitsch and Halder, in fear that Hitler was committing Germany to undertakings for which her resources were insufficient, were setting up machinery to keep Rommel in check, Field Marshal Keitel, Hitler’s right-hand man and subservient supreme commander, was discussing with General Cavallero, the Italian Chief of Staff, the mounting of an offensive against Egypt in the autumn by four armoured divisions, two of them German, and three motorised divisions, and the provision of the artillery reinforcements estimated to be necessary for the capture of Tobruk to be undertaken. Plans were also in hand to reduce Rommel’s dependence on Italian infantry. Advanced elements of what was to become the Division Afrika zbV43 (and later the 90th Light Division) began crossing to Africa in June.

On the day after Gause set foot in Africa, there appeared the first draft of a directive from Hitler which provided for the further prosecution of the war after the invasion of Russia had felicitously ended. The proposal included attacks directed at the Middle East through Libya, Turkey and the Caucasus. This grandiose scheme was called “Plan Orient”. Though its golden consummation was perhaps seen through a glass darkly, two early steps on the way were in immediate contemplation: the capture of Tobruk and the seizure of Gibraltar. The directive was followed up in an instruction from Halder to Rommel on 28th June: Rommel was required to submit a draft plan for an invasion of Egypt after the reduction of Tobruk.

The intention to drive forward aggressively did not well accord with a scheme to keep the field commander’s head in check with long, tight reins. The repulse of the British mid-summer offensive, reported to the High Command with an honest magnification of the tank losses inflicted, had added lustre to Rommel’s reputation. General Cavallero now came forward as an advocate for a single headquarters to control the operational forces in Africa, with Rommel in command. Hitler appears to have supported Rommel’s claims. Eventually Halder had to give way.

Before this issue had been settled, Halder on 2nd July ordered Rommel

to submit a draft plan for the attack on Tobruk. Still conducting a rearguard action to prevent enlargement of the African commitment, he warned Rommel to expect no further reinforcements and imposed a collateral restriction that one complete armoured division was not to be committed to the attack on Tobruk but held behind the Egyptian frontier.

The task exactly fitted Rommel’s aspirations but the annexed condition was not to his liking, as his plan submitted on 15th July demonstrated. He proposed to concentrate almost all the German forces in Africa for the attack, including the 15th Armoured Division and part of the 5th Light Division. The assault was to be preceded by 10 days of bombing to soften up the defences and was to be made against the south-east perimeter while a feint was made in the west. As in the two preceding attacks (and in the attack to which Tobruk eventually succumbed) it was planned to breach the perimeter with tanks at dawn – the Matilda tanks captured in BATTLEAXE leading the way – and to drive the armour through to the port and harbour. It was hoped to reduce Tobruk by mid-September to enable Egypt to be invaded in October.

The shape of the new Axis organisation emerged from a welter of top-level conferences, some of which Rommel attended in Germany and Italy at the beginning of July and early August. The flattering designation “Panzergruppe Rommel” at first adopted for the new force was sensibly changed, but this did nothing to cloud Rommel’s new eminence. The Commander-in-Chief in North Africa remained Italian – an appointment in which General Bastico had replaced General Gariboldi on 23rd July. Prestige prevailed over common-sense and duality of control on the battlefield was perpetuated: an Italian mobile corps, to comprise the Ariete Armoured and Trieste Motorised Divisions, was to be under Bastico’s direct orders. But all other ground forces in the operational area, both German and Italian, were allotted to Rommel’s new command, renamed the Armoured Group Africa.

The forces under Rommel’s command were to be grouped into two formations, the German Africa Corps and the XXI Italian Corps. The Africa Corps was to be built up to a strength of two complete armoured divisions and two infantry divisions, the infantry to consist of a German light infantry division in process of formation and the Italian Savona Division (the latter for static defence duties on the frontier). The Italian corps was to comprise four Italian divisions destined for employment mainly in the Tobruk-El Adem area: Trento, Pavia, Brescia and Bologna. Three of these – Trento, Pavia and Brescia – were already engaged in the siege, being stationed respectively opposite the eastern, southern and western sectors. The provision of a fourth division would free the German forces for offensive tasks as well as enabling the Italian divisions to be brought into reserve in rotation.

At the beginning of August, the High Command of the German armoured forces outlined the strategic objectives for the remainder of the year. These included strengthening the armed forces in North Africa to

enable the capture of Tobruk, and simultaneously renewing the air attack on Malta. The directive declared:

Provided that weather conditions cause no delay and the service of transports is assured as planned, it can be assumed that the campaign against Tobruk will begin in mid-September.44

An important gloss should have been added to the statement of that proviso. Whatever the weather, the Royal Navy was to prove a potent deterrent to fast reinforcement. Rommel was destined to wait two months to receive the major part of the promised forces with enough supplies and equipment to permit their active employment.

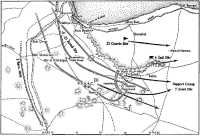

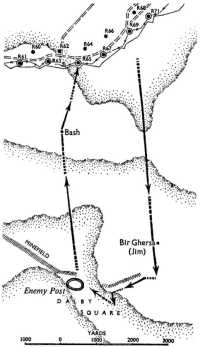

Nevertheless by mid-July the form of the projected assault had crystallised in Rommel’s mind, which immediately revealed the necessity for preliminary operations the execution of which did not have to wait on the advent of reinforcements. The plan for an irruption directed at the bifurcate junction of the main south road from Tobruk with the Bardia and El Adem Roads, later generally known as “King’s Cross”, required that the assault force should be assembled on the plateau south-east of the perimeter and jump off from an area not so remote from the intended point of penetration as to involve a long approach march. In this region the Tobruk garrison had brazenly established outposts.45 The first step was to remove them.

Towards the end of July the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion was on the perimeter on the left of the eastern sector and maintained small permanent garrisons in two outposts taken over from the 2/23rd Battalion. On 26th July, about two hours after midnight, the outpost “Normie” at Trig 146 repelled an attack by an Italian patrol of between 12 and 15 men. At 9 p.m. on the 28th Normie was heavily shelled and the five men in the post were forced to withdraw on the approach of enemy in substantial numbers.

At 10 p.m. Captain Ellis46 with Lieutenant Williams47 and 21 men set out to restore the situation. Two hundred yards from the post they were engaged and vigorously returned the fire, to keep the enemy’s heads down. Ellis then moved his patrol to envelop the position in a flanking movement. The enemy shot up flares and close artillery defensive fire came down; but the patrol charged through and the enemy fled, their numbers being estimated at 100. The patrol pursued them for some distance, returned to the post, took possession of an Italian light machine-gun, 20 rifles, 36 grenades, flares and ammunition and left the five observers in occupation.

The enemy attacked Normie again on 30th July, this time in mid-afternoon. The men in the post retaliated, the 104th RHA accurately

bombarded, and Lieut-Colonel Brown sent out two carriers with an officer and 10 men to help. The attackers were dispersed and a mortally wounded Italian was captured.

Interest in the south-eastern outposts next switched to the 2/23rd Battalion’s sector, on the right of the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion. The use of the Walled Village area as an observation site had been discontinued but two other observation posts had been established in the region. On the night of 6th–7th August the 2/23rd established one at Bir Ghersa about 5,800 yards south of the perimeter. It was named “Jim”. Another post, “Bob”, was established north of the Walled Village, due west of Jim.