Chapter 9: Parting Shots and Farewell Salutes

Manning the Salient defences, which were so exposed, so close to those of the enemy, was still the most dangerous infantry duty to be performed day by day in Tobruk. The diarist of the 2/13th Field Company paid a special tribute to the 2/24th Battalion’s work in the Salient in re-siting the tactical wire to obtain maximum advantage from its fire plan, which it did first on the left of the Salient (from 18th August to 1st September) and later on the right (from 8th to 25th September). In both sectors the 2/24th lost a number of men from anti-personnel mines

Nevertheless the Salient was less dangerous than in the summer months because the defences had been gradually improved by deepening and more overhead cover had been provided. Also the front-line troops of each side had developed a certain amount of tolerance of the other and had unofficially adopted “live-and-let-live” attitudes to some extent. After sundown there was an unofficial truce for three or four hours, more strictly observed, it would appear, on the right of the Salient than on the left, during which both sides brought up their evening meal and undertook tasks on the surface (for example, repairs to wire) that were dangerous at other times. The end of the nightly truce was usually notified by a flare-signal.

There was a curious entry in the diary of the Italian officer captured on the night on which Jack was overrun. Against 1st September he had written:–

During the night the British, perhaps having heard of the existence of German patrols, penetrate into the eastern strongpoint, wounding an officer and a soldier.

At this time, on the contrary “the British” knew nothing of patrolling by Germans. If the Germans had been patrolling effectively, they had no less effectively avoided trying conclusions with the garrison’s infantry. It had been exceptional throughout the siege to encounter German patrols other than protective patrols about their own defended areas. On the night of 11th September, however, a patrol commanded by Sergeant Buckley1 of the 2/48th Battalion, which was then on the left of the Salient, perceived a German patrol approaching the company’s wire, waited till they were close and opened fire. Three Germans were killed and the rest scattered; but later one of these, apparently lost, came into an Australian post and was captured. He belonged to the HI/258th Battalion. This was the first intimation of the presence at Tobruk of infantry of the newly-formed Division Afrika zbV. The divisional Intelligence summary surmised:–

It is thought that they were brought over to release the Lorried Inf for their proper mobile role of supporting an armoured Div.

The 16th British Brigade’s service in Tobruk was not its first contact with the AIF It had already fought beside Australians in three campaigns: in Wavell’s Western Desert offensive, in Crete and in Syria. The staff of the newly-arrived brigade immediately interested itself in the defence arrangements for the sector it was soon to take over. The critical eyes of regular soldiers apparently saw much to find fault with. “No defence scheme exists for Tobruch fortress,” a brigade letter circulated on the 23rd September roundly asserted, and next day this deficiency was in part remedied by the issue of 16th Brigade Operation Instruction No. 1, together with a “Plan of Defence – Eastern Sector”. Points in the instruction were:–

Outposts will be re-occupied as O.Ps. Patrols will be offensive to prevent the enemy encroaching in no-man’s land.

Thus the brigade approached its first operational task in Tobruk in a positive and aggressive spirit. Later its “continuous active patrolling and readiness to engage the enemy at every opportunity” were commended in the 9th Division’s report; but it was not long before most of the outposts in no-man’s land then occupied by garrison troops had been taken over by the enemy and converted to defended localities.

There was good reason for the 16th Brigade to be thinking in definite terms and in detail about action to meet an enemy attack. On 21st September, the day on which it became known that the 16th Brigade would take over from the 20th, Colonel Matthew of the 104th RHA had issued an appreciation in which he examined the recent increase in the enemy’s artillery strength in the eastern sector. It showed that opposite Matthew’s 24 guns (including 2 anti-aircraft guns) the enemy had 71 guns. (The anti-aircraft guns had only 200 rounds each and were not normally manned; Matthew’s purpose was to reserve them for defence against tank attack.) The enemy had 52 field guns against Matthew’s 16 25-pounders, and 16 medium and three heavy guns against his four 60-pounders and two 149-mm guns. Matthew deduced that without help from guns in other sectors the enemy artillery opposite him could counter-bombard his guns on a one for one basis and still have sufficient uncommitted guns to fire a “three-hour barrage on 1,500 yards front”. He made a further deduction: “There is now a possibility of an attack.”

The looming danger was perhaps more keenly appreciated by the artillery than by the infantry. What struck the 20th Brigade, freshly arrived in the sector when Matthew wrote, and then holding it for the first time, was the enemy’s remoteness. Nevertheless Colonel Crawford in an operational instruction issued on 19th September had stated that “the area has ceased to be a home of peace” and that “should an enemy attack develop it is appreciated that it will be upon positions south of the BARDIA ROAD”. Brigadier Murray and Major Allan, his brigade major, were unhappy about the sector’s defence arrangements. They were of the opinion that the second line (Blue Line) defence positions were congested when occupied by both a battalion of the divisional reserve and a battalion of the brigade reserve and were too remote from the perimeter to enable

the brigade reserve battalion to intervene quickly if the perimeter was threatened. They recommended that a new position for the brigade reserve battalion should be developed closer to the perimeter behind the tactical (B2) minefield.

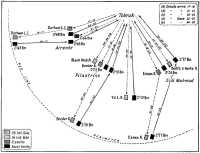

The policy of maintaining fixed outposts in no-man’s land was considered at a brigade conference on 20th September. There were five of these outposts in the brigade sector: Bondi and Tugun in front of the right battalion – the 2/13th; Jill, Butch and Kim in front of the left – the 2/17th. Neither Bondi nor Jill were visible from the perimeter. It was decided that it would be better to maintain observation by daylight standing patrols sent out to varying points, and in the meantime to send out strong fighter patrols at night to observation-post localities already known to the enemy.

Colonel Burrows decided to put the new policy into effect in a manner intended to bait the supposedly reluctant enemy. On 21st September he ostentatiously withdrew the Tugun garrison in carriers in broad daylight, but sent out a fighting patrol to the area after dark for the entertainment of any enterprising squatters. This produced no result. So next morning two carriers and an armoured car with an artillery observation officer moved out to Tugun, then across to Bondi, from which enemy positions were shelled by observation. The enemy responded by shelling Bondi very heavily. But then orders were received that the 16th Brigade was to relieve the 20th Brigade. Advanced parties from the 2/Queen’s arrived, and it was decided to cease stirring up trouble for others to face.

Its defence plan ready-made, the 16th British Brigade relieved the 20th Australian Brigade in the eastern sector on the nights of 25th, 26th and 27th September and on the 28th the sector command passed from Brigadier Murray to Brigadier Lomax. The 2/Queen’s was on the perimeter on the right, the 2/Leicester on the left; the 2/King’s Own on the Blue Line in reserve.

As soon as the 20th Brigade had been relieved in the eastern sector it began to relieve the Polish Brigade in the southern sector. This relief was completed on 30th September. But the Polish Brigade’s time in divisional reserve was as short as the 20th Brigade’s. On the night of 1st–2nd October the Poles began to take over the western sector from the 26th Brigade, which came back to divisional reserve for a much needed rest after about eight weeks in the dreaded Salient.

In the western sector the 2/43 Battalion, which had earlier replaced the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion as fourth battalion to the 26th Brigade, remained in the sector and came under the command of the Polish Brigade. The Polish cavalry regiment, holding the Wadi Sehel sector, also remained, reverting to the command of its parent formation.

The 16th Brigade’s first close contact with the enemy arose from hostile action by an enemy patrol, encountered about a mile south of the perimeter by a patrol of nine men from the 2/Queen’s on the night of 2nd–3rd October. The enemy threw grenades. The Englishmen opened fire and, as the enemy withdrew, gave chase, but apparently with insufficient speed to

regain contact. Next evening an even more unusual incident occurred. Posts in the Bardia Road sector (held by the 2/Leicester), opposite which the Italian defence line had been conveniently established beyond small-arms range, suddenly came under machine-gun fire from a distance of about 600 yards. A counter-bombardment by artillery and mortars quickly silenced the enemy weapons. “From this and other reports” the divisional Intelligence summary inferred that “the enemy is endeavouring to advance his FDLs in this area”.

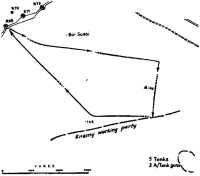

But interest was soon to switch from the eastern to the southern sector. On the night of the 5th–6th Lieutenant Cartledge2 took out from the 2/17th Battalion a small patrol comprising himself, a sergeant and two other men. From one of the listening posts established beyond the perimeter on the eastern side of the El Adem Road the four men struck out due south for 2,400 yards until they were close to the enemy minefield. There they saw two enemy parties, each about 27 strong, apparently being guided through the minefield; then a third party, not quite so close, which they followed, at first crawling then swiftly walking. After going to ground and so eluding what appeared to be a roving protective patrol, Cartledge and the others moved in to within 100 yards of an Italian working party, about 50 strong, and opened fire with telling effect, which cries of distress made evident. After engaging for about 10 minutes the patrol was about to close when machine-guns on the flanks and light automatic weapons in front began to whip the desert around them. The four Australians, with ammunition almost exhausted, “scattered towards the north” as Cartledge afterwards said, and came back to the listening post along a pipe-line ditch.

Next night, from just before midnight to dawn, enemy tanks were observed on the front of the 2/17th Battalion near the pipe-line along which Cartledge’s patrol had withdrawn, and to the west of Bir el Azazi, at which the outpost Plonk had been established. Plonk consisted of three alternative posts, one of which was normally occupied by seven men of the 2/17th Battalion, with a non-commissioned officer in charge. About 3,000 yards to the south-east of Plonk was the outpost Bondi, garrisoned by nine men of the 2/Queen’s. Nine tanks were reported west of Plonk at the one time – more than had been observed when the enemy overran the outpost Jack – and Colonel Crawford of the 2/17th estimated that 14 tanks and 4 other armoured vehicles had been involved. They came within a mile of the perimeter. Crawford thought they were closer than they realised and planned to attack them with tank-hunting platoons and to counter-attack with tanks. It was believed that the tanks were operating to protect working parties rather than offensively, since they moved about noisily.

On the night of the 7th–8th the occupants of Plonk reported five tanks advancing from the south at 12.25 a.m. Others were observed near the pipe-line. Tank-hunting patrols went after the latter and one patrol scored

hits on one tank with two “68” grenades. The Plonk standing patrol was normally relieved nightly, but this time was withdrawn without a relief. At dawn the 107th Field Regiment engaged the tanks at Bir el Azazi. Later the enemy heavily shelled the perimeter on either side of the El Adem Road and dive-bombed the troop positions of the 104th and 107th RHA covering the sector. Fifty-one bombers escorted by six fighters took part in the raid. Two guns were put out of action and three gunners killed.

In the evening Brigadier Murray instructed Colonel Crawford to reoccupy Plonk. At last light a patrol of sappers went out and mined the route the enemy tanks had taken on the preceding two nights. Another patrol then set out to occupy the post. Part of this patrol was put to ground by three tanks but they later moved away and the post was entered. A garrison of eight men was left in occupation. Groups of tanks were again reported moving about throughout the night, in one instance accompanied by infantry. Some enemy tanks in the vicinity of the listening post were shelled, but did not move off. Next morning Plonk was heavily bombarded by enemy guns beyond range of the garrison’s artillery.

The enemy tank activity seemed to indicate a more offensive intention than the mere protection of Italian working parties against patrols such as Cartledge’s. Plans were therefore made, as the divisional report expressed it, “to put an end to this bolstered aggressiveness”. It was decided to send out a squadron of 16 infantry tanks and 2 light tanks to Plonk at 9.45 p.m. under orders “to engage and defeat any enemy tanks met with”. The 2/17th Battalion and an engineer party had the task of lifting the anti-tank minefield at Plonk and also the mines laid on the preceding night to trap enemy tanks. In addition two gaps were to be made in the perimeter minefield and to be protected by anti-tank guns. Elaborate precautions were taken to identify returning tanks. The identification password was “Welsh Washerwoman”, apparently chosen as difficult for Germans to pronounce.

At dusk a patrol of two men was sent out from Plonk to the enemy minefield to the south. It found that a gap of 40 yards had been cleared and a white tape laid. The two Australians picked up the tape and fired on an enemy working party. About 10 enemy followed them most of the way back to Plonk.

Just after dark vehicle engine-noises were heard in the region of Bondi, to the south-east. Artillery defensive fire was put down around the post. Enemy tanks twice approached it before 9 p.m. but withdrew in face of defensive fire. Then the 2/Queen’s lost communication with Bondi, but soon after 10 p.m. two men from Bondi came into Plonk with the disturbing news that the garrison of nine men had been overrun in an attack by German infantry and more than 30 tanks.

The squadron of Matilda tanks, which had at first waited on its start-line outside the perimeter for the 2/17th men who were to report that the Plonk minefield had been lifted, was meanwhile proceeding to Plonk

under the guidance of Captain McMaster,3 but moving slowly, so that high engine-noise would not disclose their approach. On the way the squadron met the two men of the 2/Queen’s and learnt that Bondi had fallen, also that Plonk had been shelled and one man wounded there. The Matildas went on to Plonk at full speed. Soon after their arrival German tanks were heard coming from the south-east. The British tanks went out to meet them and got within 100 yards before opening fire. A close-range tank-battle developed; the British squadron commander was wounded and his tank disabled. After 15 minutes the German tanks made off and the British followed, but the Matildas were soon outdistanced. One of the British tanks, having mechanical trouble, had meanwhile retired to Plonk where it fought off five German tanks approaching from another direction. While this was occurring McMaster withdrew the infantry patrol from the Plonk positions, which were no longer mined, and brought it back to the perimeter. But soon after midnight a reconnaissance patrol went back and found the area all clear, so the post was reoccupied. The enemy tanks were heard at intervals during the rest of the night, but made no further attack.

Colonel Crawford was putting into effect the policy he had advocated when the 20th Brigade had gone to the eastern sector: to maintain forward observation posts but not to regard the localities taken up as ground to be denied to the enemy at all costs. To give up any ground without a fight in the face of a mere threat, however, was alien to Morshead’s temper. On 10th October he directed that the 2/17th Battalion was to hold the Plonk area and to defend it. The brigade orders laid down that the outpost was to be held by two sections of infantrymen under command of an officer, and a section of anti-tank guns from the 20th Anti-Tank Company. Whether further protection should be afforded by additional fighting patrols or other methods was left to Crawford’s discretion.

Crawford planned to send out the standing patrol at last light accompanied by two infantry working parties to erect wire, lay minefields and construct gun and weapon pits and by a covering party of one platoon to be stationed 300 yards to the south in order to prevent encirclement round the flanks. In addition to the anti-tank guns the standing patrol was to man four light machine-guns and two mortars. Captain Windeyer4 was to be in tactical command, Captain Maclarn in charge of the working parties.

By 7.50 p.m. Windeyer and Maclarn had reached Plonk with their men but at 8.40 p.m. the enemy began to shell the area heavily. The bombardment was sustained and continued for more than half an hour. Several men were hit. Some were sent back by stretcher to the perimeter. Windeyer himself was wounded but remained in active command. The working parties were drawn back from the beaten zone, but when the shelling did not abate Windeyer attempted to resume the work under shell fire. Dust

caused by bursting shells reduced visibility to five yards. The ground was stony, hard, and unyielding. Little progress was made.

About 9.20 p.m. the shelling was still continuing and telephone communication from Plonk to the 2/17th Battalion had broken down. It had been reported that German tanks had passed through the minefield gap to the north. Reports had also reached Crawford from his patrols that enemy parties had been observed at two points south-west of Plonk, and that German voices had been heard at both points. The 2/Queen’s reported that tanks were pushing in their patrols.

Another half hour passed and still there was the sound of intermittent firing around Plonk but no further word had come back to Crawford. Just before 10 p.m. Lieutenant Reid5 received orders to proceed to Plonk with all available men of his platoon, his main task being to protect the anti-tank guns. At 10 p.m., however, Madam came in and reported that both of the trucks carrying the anti-tank guns had been hit on the way to Plonk. He said that Plonk was “absolutely untenable”. Madam went back to attempt to recover the anti-tank guns. Reid awaited further orders.

Meanwhile, out to the front, the battle clamour intensified. At 10.50 p.m. Crawford reported to Brigadier Murray that his patrols had been driven back from Plonk by very heavy machine-gun and artillery fire. As they had withdrawn the enemy artillery fire had crept after them until they were almost back to the perimeter. Enemy tanks were moving around the Plonk area.

Crawford now decided to send out Reid’s patrol to Plonk to ascertain what the enemy was doing. Reid led out 15 men at 11.15 p.m., met and conferred with Captain Windeyer and then went forward with two men towards Plonk. He reported on his return:

There were 11 large tanks and five carriers or troop carriers. These latter were small vehicles. The tanks were splayed. Parties were digging on a front of approximately 300 to 400 yards. We heard voices speaking Italian (can identify definitely). At least 30 to 40 men were digging spread over the area right on the line of Plonk. ... Sounds of tank movements to the flanks and rear were audible.

Maclarn managed to recover both the damaged trucks, with their guns. One gun was out of action but was repaired by the following night.

The standing patrol’s enforced withdrawal from Plonk was reported to fortress headquarters just before midnight. Major Hodgman6 of Morshead’s staff told 20th Brigade headquarters that, since the attempt to carry out the orders had failed, he “had no further task” for the 2/17th Battalion. About 3 a.m. the enemy opened a heavy bombardment of the 2/17th Battalion’s forward companies; it was estimated that more than 2,000 shells fell in the next four hours. In the night’s operations two men had been killed and nine seriously wounded by shell fire. Captain Windeyer was mortally wounded.

In the no-man’s land in front of the 2/Queen’s, to the left of the 2/17th, the enemy was also active. The Queen’s were establishing a new outpost, called Seaview, to be occupied as an alternative observation site to the overrun Bondi, but the locality was so heavily shelled that the working party was forced to withdraw. At the old Tugun outpost site also enemy tanks were discovered patrolling at 2.30 a.m., but by 5.30 had withdrawn.

Only in the western sector had the defending forces exhibited their normal mastery of no-man’s land that night. A patrol from the 2/43rd Battalion ambushed an Italian patrol in the White Knoll region, inflicting fearful slaughter. The Italian patrol had been advancing in two groups; in the forward group, numbering 16, there was only one survivor.

About an hour before sunrise, as soon as the sombre landscape’s contours were discernible, the garrison’s artillery bombarded Plonk. Yelling and screaming were heard at once. Later there were sounds of picks and shovels being thrown onto a truck, and vehicles drove off to the south. At 6 a.m. Plonk was again bombarded, while a patrol was sent out to see if it was still occupied. About four men were observed walking about the post just after sunrise and were engaged by artillery and machine-guns. Concurrently the enemy guns carried out the customary dawn strafe of the 2/17th’s defended localities but with exceptional intensity. Again, just before 8 a.m., eight men were seen at Plonk and engaged, and again the 2/17th’s front was bombarded. But soon the warm day’s haze and the dust stirred up by gunfire and tank movement and wind made observation of activity at Plonk impossible.

Between 8.30 and 9 a.m., first 6 tanks, then 17, then 20 were reported on the 2/17th Battalion front and some machine-gun fire swept that battalion’s defences, which in this sector was unusual. The enemy reoccupied Tugun. A general attack seemed possible. A rehearsal for a planned attack in the Carmusa area by a company of the 2/15th Battalion in conjunction with tanks of the 32nd Armoured Brigade was cancelled soon after 9 a.m. and training cadres and conferences were stopped in order that the whole of the 20th Brigade could be kept in a state of instant readiness. At 9.45 12 tanks were reported hull-down just south of Plonk; but although the enemy continued to be unusually active, there was no attack.

Next night, the 11th–12th, was the culmination of the Plonk operations. Morshead ordered the 20th Brigade to attack and recapture Plonk, and to establish a new outpost in the Plonk area, but not at the site of the old outpost because it was appreciated that the previously held positions were registered by the enemy artillery. As the divisional report later stated:

any place in that vicinity offered as good observation as any other – the main object was to keep the upper hand and to put a stop to the enemy pushing our posts back and advancing his position.

The site chosen for the new post, to be called Cooma, was 1,500 yards south-west of Plonk. The forward troops were to be “C” Company of

the 2/17th and any other 2/17th troops detailed and one squadron of the 4th Royal Tank Regiment. A company of the 2/13th Battalion was placed under Colonel Crawford’s command as a reserve. The infantry attack on Plonk was to be preceded by a regimental bombardment by the 107th RHA: at slow rate for 20 minutes and rapid rate for 10. The 1st RHA was to put down smoke on the enemy minefield if the wind was favourable.

That night Lieutenant Reid led the 2/17th’s assault force of two platoons out from the wire 10 minutes after the beginning of the slow bombardment of Plonk (which to him “appeared to be very poor”). The foremost tanks, all of which should have set off for Plonk 10 minutes earlier, were then just behind the perimeter wire. About half way to Plonk Reid halted his party for the tanks to come up and open fire. Apparently Reid did not know that the tanks which were following behind the first to arrive were strung out (as the movement orders prescribed) at a mile interval between tanks and making only five miles an hour, and that therefore considerable time would pass before the squadron could be assembled on the start-line. Meanwhile the enemy put down defensive artillery fire in front of Plonk and shelled the 2/17th’s defences so intensely that, when the bombardment was heard at Brigadier Tovell’s distant headquarters, two battalions – the 2/23rd and 2/24th – were made ready to come at call to the assistance of Murray’s brigade.

After waiting in vain for the tanks to appear Reid sent back an orderly to report that he proposed to attack Plonk without them, but the orderly soon reappeared to say that he had found the tanks on their start-line. So Reid went back and learnt from the squadron commander that, having got forward late, he had thought it wisest to wait on further instructions. (The inference from the 20th Brigade war diary is that he had not referred to Crawford for these instructions till about 11.45 p.m.) Reid then reported to Crawford, who arranged to repeat the artillery preparation and to re-stage the attack 15 minutes after midnight with such tanks as were available, some having broken down.

Reid went out again to his patrol. Before the artillery program was repeated he and his men could hear digging and talking at Plonk and to the north-west. The bombardment for the attack opened slowly but intensified, the enemy replied with defensive fire, the Matilda tanks from the garrison approached, and Reid moved his patrol to about 300 yards from Plonk.

A tank action began just before 1 a.m. when the British tank commanders discerned enemy tanks about 100 yards ahead and opened fire. The battle was brisk and noisy, punctuated by tank gun reports and the rapid crackling of automatics. Fiery projectiles ricocheted in every direction as though from a carelessly ignited box of fireworks. Enemy tanks were found both in front and to the east and west of Bir el Azazi but the British tanks, though fired on wildly (but, in the darkness, not accurately) from ahead and right and left, advanced steadily onto the objective. The German tanks, still engaging, withdrew in front of the British.

The tanks moved slowly east (Reid wrote in his report) and defensive fire redoubled. My party waited and machine-guns from forward elements of enemy ceased and by the light of a flare I saw one of our tanks on or very close to Plonk. More of our tanks were firing across our front periodically and prevented me from going forward.

The firing ceased at 1.25 a.m., by which time the enemy had gone from Plonk, and for a brief interval no-man’s land was quiet. Then one or two gun flickers were seen in the enemy territory and in a moment numerous guns were flashing in a wide semi-circle from west to south to east, their fire converging on Plonk. Never before at Tobruk had such an intensive bombardment been seen; the impressive artillery display struck the watching infantry with awe. While shells were rapidly pounding and exploding upon Plonk, another group of German tanks approached from the west. Again the British tanks drove them off.

It was clear to Reid that by entering Plonk he could achieve nothing but would lose his whole patrol. He sent one section back with a wounded man and with the rest made a sweep for some distance to the east, looking for a machine-gun nest from which fire had come before the British tanks overran Plonk, but failed to find it. Reid then sent back the rest of his men but waited forward for a time before firing (at 2 a.m.) the Very light signal to indicate success of the mission to clear the enemy from Plonk. When the light shot up into the sky, the enemy artillery, probably interpreting it as a signal that the position had been reoccupied, again bombarded.

While each side in turn had been pounding this small patch of desert the work of establishing the new outpost at Cooma had been proceeding. After overrunning Plonk the Matildas had come across to Cooma to protect the infantry and had shielded them from a group of enemy tanks; but later they withdrew within the perimeter. Shortly before 5 a.m. Brigadier Willison ordered the tanks to return to Cooma and to remain out during the day to protect the infantry post, but at 5.17 Crawford reported to brigade headquarters that, although it was getting light, the tanks had not yet reached the minefield gap. He requested permission, which Murray gave, to withdraw the tanks to the forward assembly area.

At sunrise on the 12th 19 German tanks and about half a dozen other vehicles were within view on the front of the 2/17th, mostly near Plonk, which the enemy had again reoccupied, and behind the old outpost a line of sangars could be seen stretching to right and left. Along this line working parties were seen throughout the day. By mid-morning it was reported that Plonk was defensively wired. By mid-afternoon, taking advantage of the mirage which prevented observation of artillery fire, the enemy had run wire south-east from Plonk to the sangar line. Orders were now given that until further notice a squadron of tanks was to provide protection each night for the Cooma outpost, leaving the perimeter at dusk, remaining stationary in close proximity to the post all night, and returning at dawn. In addition two troops of tanks were to be kept at hand throughout the day in a state of instant preparedness to go to the

assistance of Cooma. The duty was at first performed by the 4th Royal Tank Regiment, but later for two days by the 7th.

On the evening of the 12th, about an hour after sunset but before the tanks to protect Cooma had left the perimeter, nine German tanks were perceived 90 yards west of Cooma. Crawford asked for permission to withdraw the Cooma patrol, and Murray consented. It came in at 7.30 p.m. For some hoars enemy tanks patrolled round Plonk and Cooma and in front of the 2/17th, one or two approaching the perimeter wire. Infantry tank-hunting patrols were organised but failed to make contact. At 1 a.m. the British tank squadron went out. They failed also to make contact with the enemy tanks, but for an hour shot up his working parties. The enemy fired up to 20 anti-tank guns on fixed lines and an erroneous impression was gained in the perimeter that another tank-versus-tank battle was taking place. Meanwhile Cooma was being reoccupied and strengthened.

In the succeeding days, and for the rest of the time that Murray’s brigade held the southern sector, Cooma continued to be occupied by the 2/17th and Plonk by the enemy. Each night the squadron of tanks went out to protect Cooma. The enemy, perhaps discouraged by experiences at Plonk, did not attempt to remove the garrison’s latest observation post, from which his activities in developing a new defence line could be closely observed. The situation was discussed in an appreciation written on the 13th by Lieutenant Vincent,7 the Intelligence officer of the 20th Brigade:–

That the enemy intended to push forward his general line in this and eastern sector (he wrote) was known since fall of Jack, though to what extent was unknown. It would seem that he is forming a general line from his strongposts on east of El Adem rd, eastwards south of Plonk, to Bondi.

Until this new line is well established any large-scale action on the enemy’s part in southern sector would seem unlikely.

Two days later the brigade Intelligence summary commented that events seemed to bear out these conclusions and added:

Now that this is accomplished his activity appears to be concerned with consolidation. The move forward fills in the gap which previously existed between the Bologna and Pavia Divs and which was thought to be held in depth by a small armoured column of some twenty tanks.

What is surprising about the war of the outposts is not that the enemy succeeded in wresting Jack, Bondi and Plonk from the garrison but that the fortress troops with their main force confined within the fixed perimeter line managed to maintain these little strongpoints for so long and, as some fell, to establish others; with what audacity may be appreciated if it is realised, for example, that Bondi could not be seen from the perimeter and was almost three miles beyond it and had been established within the enemy’s own minefield at a time when no armoured vehicles more formidable than infantry carriers were available to come to its occupants’ rescue. In the latest episode the enemy had been forced

to a major expenditure of effort, not to mention ammunition (in comparison with which the tallies of the Halfaya sniper gun were insignificant), to establish a line of defences some 2,000 yards from the perimeter. Moreover, observations by the counter-battery staff indicated that

in addition to increasing his field artillery for the operation, the enemy also brought round three heavy batteries consisting of the 210-mm howitzers, a battery of 149/35’s and an unidentified battery which may be one of the “Harbour Gun” batteries (155-mm).8

That week the enemy artillery strength in the southern sector was estimated to be 10 field, 12 medium and 3 heavy batteries – about 100 guns.

Although by a temporary concentration of force the enemy had effectively dominated the region in which he was establishing the new defence line, the policy of offensive defence and dominance of no-man’s land was being maintained in the other sectors. On the night of the 12th a squadron of the Polish cavalry successfully raided enemy positions established at Points 22 and 32 on the bluffs running out to the sea west of Wadi Sehel. Early on the 14th a carrier patrol of the 2/King’s Own in the eastern sector captured 10 Italians near Bir Suesi and on other nights strong fighting patrols of the King’s Own and 2/Queen’s successfully shot up enemy working parties.

The time was now approaching for the rest of the 9th Division to leave Tobruk. The final relief operation could prove more difficult than earlier reliefs, not only because several men of the 16th Brigade were missing from operations and it was therefore to be assumed that the enemy would realise that the relief was proceeding, but also because the changing over of units in forward areas would be hard to conceal.

It was more complicated than the previous ones as two complete infantry brigades together with divisional units had to be lifted each way, and it entailed a great deal of movement within the Fortress, as units had to be brought into reserve before they could be finally relieved.9

Furthermore, in the first two reliefs, incoming units were able to spend some time for acclimatisation in divisional reserve but on this occasion it would be necessary for some new units to go almost directly into forward positions.

The accompanying diagram shows the manner in which the reliefs were planned. A principle adopted in the previous reliefs was maintained: that an incoming unit should arrive at least one day before the departure of the one it replaced. Thus the number of units available for operational employment was at no time diminished.

As before, the relief was effected by a minelayer and three destroyers which came into Tobruk nearly every night of the moonless period. The first trip was made on the 12th–13th October, the rest on seven out of the nine nights from the evening of the 17th to the morning of the 26th. Most of the convoys brought in 1,000 men and took away a few less.

The relief of the 9th Australian Division

The convoy on the night of the 12th–13th brought in the 1/Durham Light Infantry and took away, among others, advanced parties of the 26th Brigade Group. During the next three days the Durham Light Infantry relieved the 2/43rd Battalion, taking over the whole of its equipment. The fortress was now one battalion over-strength and the 2/43rd was freed for relief.

The main unit reliefs then proceeded. On the night of the 17th–18th, the 2/Border relieved the 2/23rd Battalion and the 2/43rd departed; also portion of the 2/Essex arrived and more advanced parties went out. On the night of the 18th–19th the main body of the Essex came in and relieved the 2/24th Battalion, while the 2/23rd Battalion and part of the 2/3rd Field Company departed. On the night 20th–21st, a field ambulance, an anti-tank company and a number of maintenance units arrived, and the 2/24th Battalion, the rest of the 2/3rd Field Company and the 2/11th Field Ambulance departed. On the night 21st–22nd October the 2nd Czechoslovakian Battalion and portion of the 1/Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire came in and a number of headquarters and maintenance groups went out.

Nobody appreciated more than Morshead how much the defence of Tobruk owed to the non-Australian units of the garrison, which had worked in such close integration with the Australian units now departing and which were for the most part to remain. While the reliefs were proceeding he visited them and their commanders. On one day he farewelled

the regimental commanders of the five field regiments and on another lunched with Lieut-Colonel Martin and addressed a parade of the 1/Royal Northumberland Fusiliers.

Major-General Scobie,10 who had now been appointed to succeed Morshead as fortress commander, arrived in Tobruk on the night of the 20th–21st, and next day Morshead took him out to every brigade headquarters. The command of the divisional reserve passed on this day from the 26th Brigade to the 23rd British Brigade, the first of the two incoming brigades, which was now complete in Tobruk. The 23rd Brigade immediately began to change places in the southern sector with the 20th Brigade, which had to come into divisional reserve before relief, and in the evening the 1/Essex relieved the 2/17th.

The 22nd October was the last day of Morshead’s command in Tobruk. He farewelled the 4th Anti-Aircraft Brigade, the Polish Carpathian Brigade, the 16th Brigade and the 32nd Tank Brigade. At 5 p.m. he handed over command to Scobie, then went to the shell-holed, bomb-scarred “Admiralty House”, where he dined with the naval staff before departing in HMS Endeavour.

Several British war diaries recorded Morshead’s farewell visits with appreciation. It is unfortunate that the text of none of the addresses he gave has survived. We know what he said and wrote, however, in fare-welling a number of units later in the war: there can be little doubt that the theme of these addresses would have been apt, the sentiment poignant and the English scholarly; in fine, that they would have been worthy of their occasions.

That night the relief of the 20th Brigade in the southern sector was continued, the 2/Border relieving the 2/15th Battalion. The rest of the Beds and Herts battalion and portion of the 2/Black Watch came in and the 2/48th and advanced elements of the 2/17th went out. Command of the southern sector passed from the 20th Australian Brigade to the 23rd British Brigade in the afternoon of the 23rd and the relief and withdrawal into divisional reserve of the 20th Brigade (less the 2/13th Battalion) was completed next night. Then on the night of the 24th–25th the rest of the Black Watch and the 2/York and Lancaster arrived and the main body of the 2/17th and the 2/15th less two companies departed. With the hand-over of equipment from the 2/13th to the Yorks and Lancs next day, all was ready for the final act of the controversial relief, the departure of the last contingent of Australians. Brigadier Murray paid farewell visits and at 5 p.m. handed over command of the divisional reserve to the 14th British Brigade. At the end of the day there was a dive-bombing attack on the harbour. When night fell, the relieving British units served a meal to the outgoing Australians, who then began moving off to their embarkation assembly areas.

The October relief had seemed to start inauspiciously when there was some shelling of the harbour on 17th October and very heavy shelling next day: Admiralty House, beside the harbour foreshore, received a direct hit. Yet the enemy did not show awareness that the relief was proceeding and made no intensive attack. Bomb and mining raids on the port and harbour were abnormally few and of less than normal strength.

A new threat to Tobruk shipping had developed, however, though at first its nature was not apprehended. On 15th October naval headquarters at Tobruk reported that two “A” lighters that had sailed on the night of the 11th had not reached their destination and must be presumed sunk. They had indeed been sunk, on the 12th, by one of the U-boats Hitler had transferred from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, and which were now based at Salamis. Their operational assignment was to attack the shipping servicing Tobruk.

The Royal Navy was not attempting to conceal that its ships were operating in Tobruk waters but on the contrary was making full use of their presence to do damage to the enemy. HMS Gnat, one of the garrison’s best warrior-friends afloat, while escorting two “A” lighters to Tobruk, bombarded the harbour-gun battery on the night of the 18th–19th. Next night again she went out and gave the battery another pasting. On the succeeding night, the 20th–21st, Gnat sailed for Alexandria but the cruiser escort squadron for the relief convoys, the cruisers Ajax, Hobart and Galatea, carried on the work, bombarding the gun positions in company with two destroyers.

At 4.45 a.m. on the 21st HMS Gnat was torpedoed about 60 miles east of Tobruk by the German submarine U 79. Her bows were blown off but she did not sink. The nightly relief convoy was at that time to the east of the Gnat, making good speed for Alexandria. Four destroyers, including HMAS Nizam, went to Gnat’s assistance but not long afterwards the Commander-in-Chief ordered them to turn eastward because of threatened air attack. When the Nizam, which had part of the 2/24th Battalion aboard, turned in compliance with this order, a huge wave broke over the ship and swept 21 men of the battalion overboard. The Nizam turned again and went to their rescue; sailors dived overboard and helped to sustain them; but six men were drowned and two seriously injured, one mortally. Private Godden,11 a strong swimmer, courageously helped two of the others who probably would not otherwise have survived. Eventually Gnat was taken in tow by the destroyer Griffin and brought to Alexandria under strong fighter escort. Next day three destroyers bombarded the harbour at Bardia in consequence of a report that an enemy submarine was unloading petrol there, and the cruiser squadron bombarded the petrol dump area at Bardia on the night of the 23rd–24th while four destroyers shot up enemy positions at Salum.

The October moonless period was now ending. On the night of the 25th the moon, almost in its first quarter, was not due to set until 10.27

p.m. It was still shining and according fair visibility over the sea as the incoming Tobruk convoy – the last of the relief program – approached the enemy-held shores lying between Salum and Tobruk. The ships were the fast minelayer Latona and the destroyers Hero, Encounter and Hotspur. At 9.5 p.m., about 40 miles east of Tobruk, the convoy was heavily attacked by aircraft. A bomb hit the Latona and set her afire. The deck cargo of ammunition exploded, then her magazine blew up. Four officers, twenty naval ratings and seven soldiers were killed. The Hero and Encounter took off the survivors, the Hero being damaged by a near miss while alongside the Latona. There could be no question of completing the night’s program, but the three destroyers managed to make Alexandria safely next day. Admiral Cunningham and the other Commanders-in-Chief decided that the risks involved “in present moon conditions” were too great to organise a special convoy to bring out the 968 fit and 10 sick or wounded Australians still in Tobruk. They advised the Chiefs of Staff in London:–

Completion of relief has therefore been indefinitely postponed.

Thus operations for the relief of the 9th Division concluded with the loss of some life and a fine ship.

In Tobruk, on the night of the 25th, Brigadier Murray and Major Allan, Major Dodds of Morshead’s staff (who had been responsible for the efficient administrative arrangements for the relief) together with the 2/13th Battalion, two companies of the 2/15th, and rear parties of the divisional and 20th Brigade headquarters and supply staffs arrived at the embarkation assembly areas by the harbour side between 10 and 10.30 p.m. and waited for the convoy due to arrive about 11 p.m. At midnight they were still waiting. Half an hour later word was received that the move was cancelled. Between 1.30 and 2.30 a.m. dejected bodies of troops were marched to embussing points, placed on vehicles and taken to areas where they might snatch some sleep and be served breakfast in the morning: 20th Brigade headquarters to Fort Solaro, the 2/13th to Airente (Eagle Corner) and the 2/15th to Pilastrino.

–:–

Morshead received many congratulatory messages during the siege, most, but not all, sent after one or other of the garrison’s critical actions had been fought. The extent to which they imparted a consoling sense of recognition is indicated by the fact that copies of them circulated from Morshead’s headquarters were included in almost every unit diary. The concluding paragraph of the narrative of the siege in the divisional report referred to them:–

Messages of commendation and encouragement were received from the Parliaments of the Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand, from the Prime Ministers of Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand, the Commanders-in-Chief, the G.O.C. AIF and from many others. These messages were appreciated to an unusual degree; they heartened the whole garrison and inspired them to still greater efforts.

No plaudits hailed the 9th Division, however, as it left the battleground of its hard striving. If there had been some generous impulse to acclaim, perhaps the bitterness engendered by the controversy about the relief had quelled it, just as it tainted the last interchanges between the British and Australian Governments about the division’s departure. On 26th October Churchill telegraphed Curtin:

Our new fast minelayer, Latona, was sunk and the destroyer Hero damaged by air attack last night in going to fetch the last 1,200 Australians remaining in Tobruk. Providentially, your men were not on board. I do not yet know our casualties. Admiral Cunningham reports that it will not be possible to move these 1,200 men till the next dark period in November. Everything in human power has been done to comply with your wishes.

In a further telegram to Curtin sent next day Churchill detailed the casualties and concluded with the statement:–

We must be thankful these air attacks did not start in the earlier stages of the relief.

Curtin, who had meanwhile heard from Blamey that the relief had been “indefinitely postponed”, replied on the 30th:–

You may be interested to know that Inspector-General Medical Services who recently returned from a visit to the Middle East and who saw first units of 9th Division to be relieved reported they had suffered a considerable decline in their physical powers. As condition remainder would have deteriorated further we are naturally anxious that those remaining should be brought away during next dark period as intended.

Perhaps there was less magnanimity in these messages than Burke would have thought wise but the friction remained on the political plane.12 No sentiments of envy or disapproval were heard in Tobruk to weaken a bond between British, Australian, Indian and Polish fighting men that had been forged in the heat of battle by shared suffering and combined effort.

If the greatest single factor in repelling the German assaults and holding the besiegers off was the steadfast, efficient and brave work of the field artillery which for some of the time was solely and for the whole time preponderantly from the British Army; if the greatest call on deep resources of courage was laid most often upon the anti-aircraft gunners who stood to their guns day and night even when they themselves were the direct target of the strike; if the most dreadful burden borne by the defenders was the constant manning of shallow and sun-scorched diggings and weapon-pits in the regularly bombed, bullet-raked Salient, in which to stand in daylight was to stand for the last time; these judgments only illustrate that each man had his own job in the conduct of the defence. The spontaneous respect of all arms and services for the performance of the others and the loyalty with which they combined were the things that made Tobruk strong in defence and dangerous to its besiegers. General Auchinleck summarised the garrison’s achievement in his despatch:–

Our freedom from embarrassment in the frontier area for four and a half months is to be ascribed largely to the defenders of Tobruk. Behaving not as a hardly

pressed garrison but as a spirited force ready at any moment to launch an attack, they contained an enemy force twice their strength. By keeping the enemy continually in a high state of tension, they held back four Italian divisions and three German battalions from the frontier area from April until November.

That such success was achieved was due most of all to Morshead’s own insistence on an aggressive conduct of the defence; his determination that the enemy should be attacked wherever he came within reach; his single-minded rigid resolve, to which he adhered in the face of counsels for a more flexible defence, that his forces should never yield ground nor give quarter, that if any place was wrested from them, they should not relent until they recaptured it. There were some misjudgments. Sometimes the tasks prescribed could not be done with the means given. Nonetheless Morshead’s policy left his opponent no other choice than to let the garrison forces keep their ground, at least until he felt able to mount a massive attack.13

–:–

Courageous patrolling had contributed not a little to that achievement. If during the siege some magic eye could have captured the comings and goings after dark around Tobruk, each night small groups of men would have been seen going forth into no-man’s land from every part of the perimeter, some proceeding along the wire and anti-tank ditch, some covering ground close in and some – probably about thirty in all around the whole perimeter – thrusting deeply into enemy territory. Some went out at night to lie up for the next day, observing the enemy’s defence-works and activities. Others patrolled daringly in daylight.

When the historian thinks of these patrols, names and occasions emerge at random. Take, for example, a brief war-diary entry concerning the 2/24th Battalion: “B company patrols capture 6 officers, 57 other ranks.” No wonder a German soldier noted in his private diary captured in mid-April:–

They already have a lot of dead and wounded in the 3rd Company. It is very distressing. In their camp faces are very pale and all eyes ... downcast. Their nerves are taut to breaking point.

There was the sustained patrolling of the 18th Indian Cavalry Regiment: for example, the patrol on 27th May when Captain Gretton was killed and no fewer than three remarkable patrols by Captain Barlow. There were the brilliantly executed patrols by Lieutenant Harland of the 2/15th

Battalion in the early siege days; the patrol led by Captain Llewellen Palmer of the King’s Dragoon Guards, which created such confusion that the enemy continued fighting among themselves after the patrol had left. There was Lieutenant Beer of the 2/48th Battalion, whose patrol record few rivalled and who on the 29th–30th May with six others wearing sandshoes went out to the by-pass tracks (not yet a formed bitumenised road) at a distance of five miles from the perimeter, mined them and laid up there in ambush for an hour. They boldly began their journey in a captured car but had to abandon it when a wheel got stuck in a slit-trench.

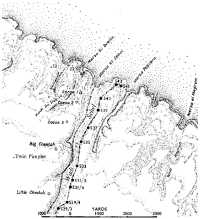

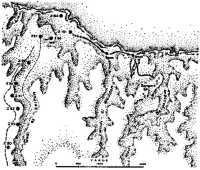

Opposite each sector of the perimeter were localities beyond the wire which had been the scene of adventurous patrol activity. On the west of the perimeter near the coast, across the Wadi Sehel and beyond the garrison’s “Cocoa” outposts, the most prominent landmarks were the Twin Pimples, looking like bare-topped rabbit warrens, though the inmates were Italians. Their nights were troubled; death often struck; but their most dreadful night was on 17th–18th July when 40 Special Service troops broke into the heavily-fortified position and overran it, killing all but one of those who did not flee, while a patrol of nine Indians attacked a flanking post. Next night a large Italian working party of well over 100 men, protected by Germans, was successfully shot up by a patrol of the 2/48th Battalion led by Lieutenant Wallis.14

Near the head of the Wadi Sehel the main coast road entered the perimeter south of S21. Here the broken eroded ground provided good cover for the besieging Italians, but the road was under British observation. Vehicles bringing up their rations and supplies had to come by night. On 29th June Lieutenant Nicholls15 of the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion led out a patrol of six at 9.30 p.m. to intercept the Italians’ ration truck on its return journey; by that time they were expected to have relaxed their vigilance. The plot failed because the truck returned by another route. Nicholls then tried to intercept the carrying party but, failing again,

decided to attack an enemy position which was manned by about 40 men and armed with three machine-guns and three mortars. Nicholls got close to the sentry undetected and grabbed him as he moved to give the alarm, whereupon his men rushed a sangar and dispatched its eight occupants with the bayonet. A mêlée developed as other enemy came to help their comrades, Corporal Raward16 repulsed an attack by five but was himself mortally wounded. Private Evans17 shot an enemy machine-gunner and with Private Jamison18 got Nicholls’ prisoner away.

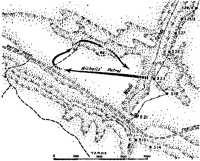

South across the Derna Road and towards the dreaded Salient, the perimeter from S19 to S11 ascended in turn two escarpments. West of S15 on the second escarpment was the feature well-named “White Knoll”; between the two escarpments were a number of enemy sangars and diggings. In this area Lieutenant Beer had one of his most successful nights when a small patrol under his leadership attacked the enemy in vastly superior numbers and brought back a talkative prisoner. On the night of 17th–18th July Captain Buntine’s19 company of the 2/28th Battalion raided enemy positions on the two escarpments. The company was divided into two for the raid. One platoon patrolled uneventfully along the northern escarpment. The main body, finding White Knoll unoccupied, established a base there, and Lieutenants Hall’s20 and Hannah’s21 platoons, with Lance - Corporal Booth22 as forward scout, launched raids deeper into the enemy’s rear, killing 19 of the enemy and wounding twice as many Corporal France accounted single-handed for two enemy weapon-pits. Only one Australian was wounded .

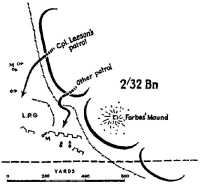

In the Salient of bitter memory, patrolling against the close and strongly held enemy positions, webbed with booby-traps, was most dangerous. Corporal Weston23 of the 2/48th and Lieutenant Bucknell of the 2/13th are two names to stand for many who more than once risked death there on night patrol but by stealth and quick action outwitted and killed their opponents. It was in front of this chalky knob, known as Forbes’ Mound, that Corporal Leeson’s24 six-man patrol from the 2/32nd Battalion on the 24th–25th July stalked two German crews manning a machine-gun and a mortar. The Germans were moving their weapons from point to point in a truck to counter-attack another patrol of the 2/32nd which had become embroiled in a firefight with enemy unexpectedly encountered in sangars close to the Australians’ wire.

From the southern shoulder of the Salient the perimeter ran for some distance east-south-east. Parallel to it, and some two miles to the south, ran a low escarpment which petered out near Bir el Carmusa where, as the name implies, there was a well and a fig tree. The enemy developed a line of defences along the ridge. For knowledge of defences such as these the artillery and operational staffs depended almost entirely on patrol reports until late in the siege when some air photographs became available. On the night of 22nd23rd July a patrol of five men from the 2/43rd Battalion under a non-commissioned officer found a new minefield some 300 to 400 yards from the foot of the escarpment and followed the field in a westerly direction. Here is an extract from the patrol’s report, which was accompanied by an excellent diagram of the minefield.

The bearing of this field is 290°. At this point a gap of 10 yds. occurs (39934251) – this gap is marked by trip-wires. The minefield then runs on a bearing of 340° and is composed of 2 rows of anti-personnel and 4 rows of Teller mines. The

spacing of this field is similar except that the AP mines are 9 paces apart, also the mines are staggered. One Teller and one AP mine were brought back. Recent tank tracks exist in the gap in the minefield.

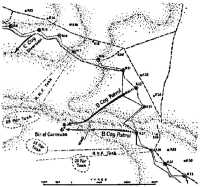

Eastwards was the sector from R21 to R29 where the perimeter bulged out southwards onto the plateau and from which there was a clear view of the fig tree at Bir el Carmusa. On the night of 19th–20th July the 2/10th Battalion sent out two large patrols to operate against enemy positions around Carmusa while the 1st RHA fired an effective artillery program in support. From R23 Lieutenant Ellenby25 led out a patrol of 21 men including 2 sappers which assaulted the Carmusa strongpoint and inflicted numerous casualties. Ellenby and Private Booker26 broke through the wire but Ellenby was shot down after he had flung seven grenades into the enemy weapon-pits. At Ellenby’s command Booker blew the whistle signal to withdraw. Private Fallon27 carried Ellenby back to the Australian lines, a distance of 2,750 yards. The other patrol of the same strength, led by Sergeant Seekamp,28 went out from R27 and was equally successful but encountered very heavy fire from more than 15 machine-guns and had three men wounded.

Farther east the El Adem Road issued from the perimeter between posts R41 and R43. It was from R41 that Lieutenant Haupt with two others of the 2/12th Battalion went out on 10th July to establish an observation post more than three miles from the perimeter. They occupied it for more than 15 hours and throughout one whole day made careful observations of the enemy’s doings and the effects of his shelling.

On the night after Haupt returned, Lieutenant A. L. Reid and Sergeant Russell led out two fighting patrols, each of nineteen men, to raid an enemy position astride the road. Support was given by the guns of 1st RHA and the machine-guns of the 1/Royal Northumberland Fusiliers. They drove out the occupants from one position, assaulted another and

brought back five prisoners, leaving the ground strewn with dead and wounded. Reid and nine others were wounded and three did not return. The Italian radio described the raid as a foiled attempt to break through the siege lines.

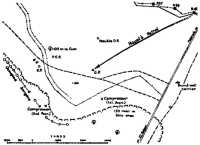

It was from R41, too, that Captain Bode29 of the 2/15th Battalion led out his patrol of eleven men on 31st August to attack a strongpoint east of the road. Five patrols of the 2/15th had earlier reconnoitred the region, two of them led by Sergeant Patrick,30 who accompanied Captain Bode. They moved out at 12.15 a.m. when the moon was within one hour of setting so that the night would be dark when they arrived. For the last few hundred yards they approached on hands and knees, formed up about 50 yards behind the post and advanced north. A flare went up, the Australians threw themselves to the ground and a Breda machine-gun opened fire. Next day Chester Wilmot heard Patrick tell Colonel Ogle what ensued.

The firing stopped and Captain Bode said “Come on boys, up and at ‘em.” We charged. Another flare went up behind us and the Ities must have seen us silhouetted against its light. They swung four machine-guns straight on to us and a volley of hand grenades burst in our path. For a few seconds the dust and flash blinded us, but we went on. In the confusion I ran past the machine-gun pit that I was going for, and a hand grenade – one of the useless Itie money-box type – hit my tin hat. The explosion knocked me down but it didn’t hurt me. As I lay there, the fight was going on all around, and I could hear Ities shouting and screaming and our Tommy-guns firing and grenades bursting.

I rolled over and pitched two grenades into the nearest trench and made a dash for the end machine-gun post. I jumped into the pit on top of three Italians, and bayoneted two before my bayonet snapped. I got the third with my revolver as he made for a dug-out where there were at least two other men. I let them have most of my magazine. Another Italian jumped into the pit and I shot him too. He didn’t have any papers so I took his shoulder-badges, jumped up and went for my life.

I cleared the concertina wire in front of the post, but caught my foot in a tripwire. Luckily it brought me down, for just then a machine-gun burst got the chap next to me. I wriggled over to him, but he was so badly hit I couldn’t do anything to help. I took his last two grenades; crawled out through the booby-traps and then threw one grenade at a machine-gun that was still firing. As this burst, I made a dash for it, and a hundred yards out reached a shell-hole. I waited till it was all quiet again, and then came back.

At one stage Bode, though maimed with a bullet-wound in the hip, attempted to pull two Italians from a five-foot deep weapon-pit but an

Italian grenade exploded at his feet, temporarily blinding him. Corporal Isaacs31 went to his leader’s assistance, shot the two Italians and shepherded Bode out of the post. As the patrol returned Bode came in singing the old song “My eyes are dim, I cannot see; I have not brought my ‘specs’ with me.” Three Australians, including Bode, were wounded; three were missing.

It was from this sector also that at 8 a.m. on 14th May Lieutenant Maclarn issued from the perimeter near R43 with four carriers taking with him an artillery forward observation officer. They proceeded south for 4,000 yards, and began to direct artillery fire on a tank and other targets. Soon two enemy tanks appeared, then others, making six in all. These engaged Maclarn’s carriers, but Maclarn got them back safely to the perimeter, which was re-entered an hour and a half after their departure.

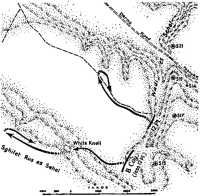

Farther east, opposite the southernmost portion of the perimeter, was the part of no-man’s land in which many of the outposts came to be established. It was here that Captain Barnes32 led ten men of the 2/9th Battalion to locate, cut and bring back portion of an electrical cable previously reported in the Sghifet el Adem. That was nearly 7,000 yards from the perimeter. The patrol proceeded from R53 by way of “White Post” (in the locality later known successively as Bob and Bondi) and the Walled Village, and then worked back and forth along the foot of the escarpment until it found the heavy black cable, which the men then cut under fire. At one stage entrenched enemy engaged the patrol with a machine-gun, a mortar and six light machine-guns. Although nearly four miles from the perimeter Captain Barnes charged the position, inflicting six casualties for two suffered, of whom one was missing.

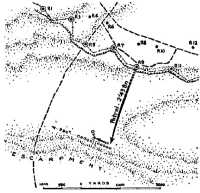

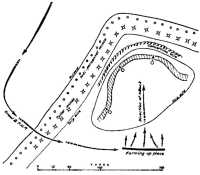

The south-eastern sector of the perimeter from, say, R63 to R71 was one of the quietest in the early days of the siege though towards its end most activity by both sides was concentrated on this part of no-man’s land, for here the British were planning a sortie, the Germans an incursion. The fighting for some of the outposts has already been described. Until late in the siege much of the patrolling in this sector was therefore done with carriers, some at night but mostly by day, and with this phase the names of Lieutenant Masel and Sergeant Rule, both of the 2/28th, will always be associated. A daylight patrol on 10th May by three carriers commanded by Captain Sudholz of the 2/43rd around Point 144 and Trig 146 provides an example of the daring way in which these lightly armoured vehicles were handled. The sketch shows the patrol’s

route. The end of the southward leg of its course brought it upon an Italian working party constructing gun-pits and weapon-pits along a reverse slope. About 1,200 yards to the south-east five enemy tanks and three anti-tank guns were seen. The carriers shot up the working party and were in turn engaged by the tanks and guns. The patrol returned unscathed to report the construction of a new defence line.

Four and a half miles to the south of the perimeter lay Dalby Square, the scene of Captain Joshua’s raid on the night 13th–14th September. The report of one of Joshua’s preliminary reconnaissance patrols to the area is an excellent example of patrol reporting. Joshua took with him three NCOs of his own battalion (the 2/32nd), a sergeant sapper and a corporal and one other man from the 2/43rd.

The patrol left R65 at 2130 hours, proceeded to BASH OP, and left there on a bearing of 160°. At 1450 yards a white cement obelisk was 50 yards on left of route. At 1900 yards (41944166) a drum with cask on top was 120 yards to left. After passing the cask a small recently constructed dugout was 80 yards to the right of the route. It was camouflaged with bushes, and in front were several rows of stakes 2 feet high, as if ready for wire. Telephone wires led into the dugout from the rear and a foot pad not well worn but recently used ran along the wires. A shovel was leaning against the dugout. At 3800 yards a road was reached. At 3900 yards (42004147) a spur of minefield was met; it consisted of a row of B4 web-type mines, joined together with loose string and hidden under bushes, with two rows of B2 box-type mines about 6 yards to the rear. Bearing of the field was 52°. Sounds of digging and voices were heard on an approximate bearing of 230°. Patrol is unable to estimate the distance but the sounds were a long way off. The patrol turned right and moved along the field for 250 yards, where this spur field met the main field. The engineer devitalised the web-type mines as the patrol moved. He did not touch the B2 mines. At the junction the main field had bearings of 335° and 160°. Patrol turned left and followed the field for approximately 400 yards, reaching a road which appeared to be much used, bearing of road is 300° (41994143). 200 yards west of the junction of road and field is a branch road, bearing 285°. Search was made 60 yards south and 60 yards east from junction of field and road, but no mines were found. Patrol commander and two others moved 100 yards westerly along the road and came to a recently used latrine indicated by a sign “MATTERCINE”. 100 yards farther west along the road a sangar was seen (41974144), and party then turned to their right (northerly), and as they turned they heard an alarm from the direction of the sangar. The alarm resembled a blowfly in a spider’s web, and was probably made by a wind instrument. Remainder of patrol approximately 200 yards away could clearly hear the alarm. No shots were fired immediately, but shortly afterwards the balance of patrol was fired on by LMGs (estimated 2) from the north-west of the patrol commander and approximately 400 yards from him (41944147). Another MG was to the south or south-west of the patrol commander and approximately 800 yards from him (41904140). This gun had a slower rate of fire. Some rifles were also fired and voices could be plainly heard. The time was then 0200 hours. Patrol withdrew to the junction of the two minefields, moved north 6450 yards meeting a road 40 yards south of the tank trap. Patrol moved 375 yards north along the wire to R69, reaching there 0515 hours.

An earlier excellent patrol in the same region was carried out by the 2/24th Battalion. Moving out from R67 at 9.30 p.m. on the night of 15th–16th July the patrol of two officers and 15 men led by Lieutenant

Hayman33 investigated a minefield and, stumbling upon two enemy posts at a depth of 6,000 yards from the perimeter, assaulted them inflicting numerous casualties. Hayman and the other officer (Lieutenant Finlay34) and three of the men were wounded. One of, the men, whose leg seemed to be broken, had to be left. He died later in an Italian hospital. Morshead asked that this patrol’s exploits be “fully written up in next Mideast Summary”.

Farther east and north was the Bardia Road and the precipitous Wadi Zeitun, held from 21st April onwards by dismounted Army Service Corps men. Here at midnight on 9th–10th July five men of the 2/23rd Battalion 4, were led out by Private Stirk35 on an adventurous patrol from Z101, the easternmost of more than 100 perimeter strongpoints east of Ras el Medauuar. They intended to take prisoners. The patrol descended the forward slopes of the bluff, passed round the next bluff and set up a base near the mouth of the Wadi Weddan. They patrolled 1,500 yards up the wadi, found no enemy, returned and moved their base to the next wadi to the east, near the shore. From there they searched some sangars 600 yards to the south but, finding no enemy, returned to their base and waited there until first light.

At dawn Stirk took his men back to the sangars, which were still empty. Then they climbed up a headland ahead of their base to watch an enemy observation post, and saw some movement to the north-east of it. They pushed on 500 yards to the east where they halted a party of three enemy near the mouth of the Wadi Belgassem, two of whom held up their hands. The third made off but they shot him, badly wounding him.

Private Stirk and his four comrades arrived back at Post Z101 at 10.45 a.m. with their two prisoners.

–:–

The siege of Tobruk was not, like some famous sieges, a struggle for survival in the face of dire shortages of food or water or munitions. Shortages there were at times but never so acute that men were starving or guns without rounds to fire. For this the main credit must go to the Royal Navy’s Inshore Squadron and the garrison’s anti-aircraft artillery – the 4th Anti-Aircraft Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Slater. Moreover

the navy’s efforts to keep the garrison supplied might have proved abortive or too costly if the anti-aircraft gunners’ defence of the harbour and base installations had been less successful. This protective battle was won only by continually improving operating practice and developing new techniques to cope with each change in the enemy’s method of attack; it was won by men in under-strength units handicapped by inadequate supplies of gun spares and signal equipment and a scarcity of external labouring assistance. Often the available gun-power was seriously reduced by enemy action; but the speed with which the workshop sections carried out repairs usually reduced the periods of extreme danger to a few hours.

Tobruk’s anti-aircraft gunners had to deal with four main types of attack – daylight dive-bombing raids, daylight high-level attacks, night-bombing raids and night-mining raids. As the defenders improved their technique and fire power the enemy changed the method of attack. At first daylight raids predominated, more than half of them dive-bombing raids. As time went on the frequency of dive-bombing attacks diminished and of night raids increased. The trends can be seen in the accompanying table. On only one day during Morshead’s command was no air raid warning sounded.

| Dive-Bombing Raids | Total Daylight Bombing Raids | Night Bombing Raids | Total Bombing Raids | Daylight Reconnaissances | |

| April 10th–30th | 21 | 41 | 11 | 73 | 27 |

| May | 17 | 60 | 22 | 99 | 58 |

| June | 6 | 58 | 76 | 140 | 39 |

| July | 4 | 91 | 43 | 138 | 46 |

| August | 11 | 55 | 77 | 143 | 39 |

At the beginning of the siege the anti-aircraft artillery in Tobruk comprised 16 mobile heavy 3.7-inch guns in action and 8 unmounted guns not yet brought into action, 5 mobile and 12 static 40-mm Bofors (of which 6 static guns were not yet in action) and 42 20-mm Bredas. As soon as four of the static 3.7-inch guns were brought into action, four heavy mobile guns were released for perimeter defence to deter dive bombers and artillery observation planes. They were, however, brought back to the harbour region whenever particularly vulnerable targets were in port.

The defensive air battle began with a struggle to defeat the dive bombers, which predominated in the early attacks. With the exception of Brigadier Slater, who had commanded the 4th Anti-Aircraft Brigade with the British Expeditionary Force in France, none of the anti-aircraft personnel in Tobruk had experienced dive-bombing attacks before the siege began. By 14th April, when the first large-scale dive-bombing attack was made, an elementary fixed horizontal barrage at 3,000 feet had been prepared to give protection to the ships and waterside installations. A serious weakness was immediately revealed: aircraft had penetrated unobserved before the barrage was fired. This was successfully countered by establishing an observation post on the escarpment overlooking the harbour. As further attacks developed, other weaknesses were discovered. There appeared to

be gaps in the barrage; it had insufficient depth; it was often fired too soon, so that the bombers, discovering its edge, could dive under it. These defects were effectively remedied. The barrage was spread from 3,000 to 6,000 feet and made to swing back and forth across the harbour; the fire was intensified by repairing and bringing into action four captured Italian 102-mm guns. In August, three more of these were added. Pilots who still penetrated the barrage found themselves engaged accurately, and often fatally, by the 12 static 40-mm Bofors guns of the 40th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, which were disposed singly around the harbour.

In mid-August the Royal Navy provided three 20-barrel parachute rocket projectors whose missiles contained a parachute which opened above the vulnerable area and trailed long strands of wire – like an octopus with long tentacles; at the end of the tentacles was a small bomb. The rockets were first used on 18th August and achieved great success in countering an attack by 18 dive bombers escorted by three fighters. The diving aircraft were completely upset. Two came in contact with bombs and one withdrew with a parachute entangled in its tail.

One of the enemy’s counter-measures was to attack the gun-sites. Six guns were put temporarily out of action by these tactics, but none was destroyed. After the lesson had been learnt in May and June that the gunners’ safest course in these attacks was not to take cover but to engage the attacking aircraft, it was seldom that an attack on the gun-sites did not result in the destruction of one or more aircraft shattered by direct hits. There were nineteen dive-bombing attacks on the guns from 10th April to 1st September, when the last such attack was made. The effectiveness of this policy in combating the dive bomber can be seen from this table:–

| Month | Number of dive-bombing raids | Number of dive bombers(Ju-87) engaged |

| April (last 20 days) | 21 | 386 |

| May | 17 | 277 |

| June | 6 | 123 |

| July | 4 | 79 |

| August | 11 | 217 |

| September | 1 | 46 |

| October (first 9 days) | 2 | 57 |

When it became evident to the enemy that dive-bombing attacks were proving very costly but not very effective, he swung the weight of his attack into high-level daylight raids. Such raids were carried out daily from 11th April to the end of July. Towards the end of May their frequency increased. Sometimes 10 to 15 attacks were made in one day on the jetties and town area.

These attacks usually took place at heights between 18,000 and 25,000 feet. Observation was the first very difficult problem. Visibility was such that an attacking high-level bomber was seldom seen until it had dropped its bombs, and this from a height from which it could bomb accurately. Efforts were made to get telescopic observation by obtaining an early sound

pick-up of the aircraft and predicting a future bearing in which telescopic search could be carried out within the range of likely altitude of approach but, owing to haze and clouds, these met with very limited success. The method next adopted was to attempt to bar the way although the plane could not be seen. A line on which fire was required was drawn just outside the line of bomb release for attack on the vulnerable areas in and around the harbour. Any aircraft approaching a position from which it could attack a target in these areas would be confronted with a barrage of shells bursting immediately ahead in its line of flight. The barrage was divided into four sectors, each the responsibility of one four-gun position. In September a system of decentralised control was developed, each gun position officer firing on his own initiative. As enemy aircraft developed deceptive methods of approach, extremely quick appreciation and decision were required. Some gun-position officers became remarkably adept in outwitting the enemy. The introduction of these barrages bordering the bomb-lines had an immediate effect on bombing accuracy. A large proportion of the bombs fell harmlessly north of the town; some were released over the sea.

After the end of July high-level daylight attacks became less frequent and were mainly confined to times when a particularly inviting target was in the harbour. The scale of night attack, on the other hand, steadily increased month by month from the beginning of the siege until it reached maximum intensity in late summer The number of night bombers engaged each month was as follows:

| April (last 21 nights) | 32 |