Chapter 10: Ed Duda

Tobruk on its desert coast had been enveloped in dust by every land-wind for centuries before the heavy transport and armoured vehicles of two armies had ground its arid fine-clay hinterland to light powder. Airente was the dustiest corner in Tobruk. There, after having been brought back from the embarkation point, the men of the 2/13th Battalion, some of whom had bedded down where they could – but most had not troubled – were greeted on 26th October with the densest dust-storm suffered since the siege began. Visibility was only a few feet. The Durham Light Infantry Battalion did its best at short notice to serve the Australians with a hot breakfast.

At midday Brigadier Murray attended a conference with General Scobie to discuss the disposition of the remaining Australians. It was agreed that the two companies of the 2/15th Battalion would remain in the Pilastrino area and could be called upon to provide working parties. General Scobie proposed that the 2/13th Battalion should take over the perimeter in the western sector along the Wadi Sehel near the coast, to carry out the role which he had intended to assign to the Polish Officers’ Legion, which was to have arrived in Tobruk in the ships that were to take the last Australians out, but now was not expected to arrive until destroyer convoys were resumed in the November moonless period. Brigadier Murray raised no objection.

Soon afterwards General Scobie visited Colonel Burrows at Airente and offered him a choice between the operational role indicated and a non-operational one. Burrows made the only choice a soldier could. Moreover he knew from his long experience that to have his men at work was the best way of keeping them out of mischief.

The battalion had handed over to the Yorks and Lancs all its equipment except what had been ordered to be carried on the man on embarkation: rifles, pistols and personal accoutrements. It was therefore directed to take over the equipment that had been drawn for the Polish Officers’ Legion by the Polish Cavalry Regiment. When it moved forward it was to come under the command of the Polish Brigade, which was responsible for the western and Salient sector. The defences to be occupied constituted a two-company or squadron position; there was also a reserve squadron locality. It was decided that nucleus parties would go out that night to the Polish Cavalry Regiment then holding the area and that three companies would effect the relief on the succeeding night while the fourth waited until an area for it to occupy had been reconnoitred.

Some reorganisation was taking place to strengthen the western sector, in which the front-line units had always been very fully extended. After the Salient line had been shortened, this sector had been held with two battalions in the Salient, one battalion and a cavalry regiment on the western perimeter and one battalion in reserve. It had been planned that

on the arrival of the Polish Officers’ Legion, which would slightly augment the holding-unit strength beyond that in Morshead’s day, the front-line strength would be increased by disposing the cavalry regiment in the centre of the Salient and extending the right flank of the Polish Battalion at the Salient’s northern corner, thus removing the inter-battalion boundary from a very vulnerable region overlooked by the enemy positions around S7. By relieving the Polish Cavalry Regiment in the Wadi Sehel, the 2/13th would enable these redispositions to proceed. The perimeter between the Polish Battalion on the right of the Salient and the Wadi Sehel positions to be taken over by the 2/13th Battalion was held by the recently arrived Czechoslovakian Battalion.

The coast sector on the western perimeter was quite unlike anything the 2/13th had known in Tobruk. In other sectors in which it had done front-line duty, the perimeter had opened out onto a terrain which though ridged and uneven in parts was rather flat and featureless, but here the perimeter posts were cut into the cliff-face of a gorge, just below its rim. The wadi they overlooked was about 150 feet deep, with a wide, normally dry watercourse at the bottom.

There were a number of wells in the wadi bed and a pumping station that provided – notwithstanding that it was in no-man’s land – a substantial proportion of the fortress’s potable water. That the garrison had for so long drawn water from beyond its supposed confines was probably a result of the intensely aggressive patrolling of the Indian and Polish Cavalry Regiments which had kept the enemy on the defensive and deterred him from establishing a defence line or outposts close to the wadi.1

Additional protection to the sector and in particular to the pumping station was provided by five outposts: Cocoa 1, 2 and 3, Big Cheetah and Little Cheetah. These were situated on the plateau on the enemy side of the wadi but close to its verge.

The 2/13th advanced parties went out to the sector on the night 26th–27th October. Next morning Major Colvin,2 Colonel Burrows’ second-in-command, went forward to the Polish Cavalry headquarters. Although the preceding day’s storm had to some extent abated, dust still shrouded the western perimeter. Major-General Kopanski visited the cavalry headquarters about 10.30 a.m. and informed Colvin that a prisoner captured on the night of the 25th–26th in the Wadi Sehel had stated that an attack would be made on the sector in the early hours of the next morning, the pumping station in the wadi being one of the principal objectives. This prisoner, a Libyan, was a civilian enemy agent – the first apprehended at Tobruk – and had been accompanied by another Libyan who, he said, had come straight from the Italian military Intelligence department at Beda Littoria. The captured Libyan said that he had been ordered by a Captain Bianco of the Italian Intelligence department to ascertain the dispositions in the western sector facing the Wadi Sehel.

Kopanski came back to Airente with Colvin to discuss this information with Burrows. Soon afterwards Scobie arrived and the conference considered whether the relief should proceed as planned at the risk that the Australians might be attacked on the night of their arrival, before they knew the ground. Scobie concluded, however, that an attack on a large scale was improbable, and decided that the relief should take place. Burrows decided that as well as manning the positions to be taken over he would detach a platoon from the reserve company to guard the pumping station. In the early afternoon he went forward to the headquarters of the unit sector.

The relief, in accordance with normal front-line routine, was due to be effected after darkness fell; but at 3.30 p.m. Burrows ordered that the battalion come forward at once under cover of the dust storm then raging. The transport summoned without notice while the drivers were taking their meal arrived in driblets but by 5.45 p.m. battalion headquarters and the forward companies had arrived in the forward sector. The relief was completed by 10 p.m., and soon after midnight the last convoy of outgoing troops departed. The men stood to arms throughout the night to face the predicted attack, but none eventuated.

The 2/13th now held the perimeter from the sea to S33, with the Czechoslovakian Battalion on its left. Two companies were forward: Captain Daintree’s on the right, also manning the three Cocoa outposts, and Captain Walsoe’s on the left, also responsible for the Cheetahs. Captain Graham’s3 company was in reserve. In the evening of the 28th Captain Handley’s company came into a deep reserve position in the Wadi Magrun.

So the men of the 2/13th Battalion settled down to weeks of front-line duty, mercifully uneventful, in the best sector they had known. The rugged gullies and headlands afforded plenty of cover. Moving up and down the wadis and hilly tracks the troops got beneficial exercise; all except those who could not be spared from perimeter defence bathed freely from the beaches of the Mersa Pescara and Mersa el Magrun. The weather cooled; the sun ceased to scorch. The men lost the languor and pallor that had seemed to afflict most of them at the height of the summer But the élan in patrolling that had characterised their early action days was not in evidence, nor did Burrows press his men so much to offensive embroilments as he had in other sectors. Nevertheless they executed a number of deep night patrols, and some in daylight, particularly to the Wadi Bu Dueisa.

The 2/15th Battalion’s two companies near Pilastrino, though not exposed to the front’s dangers or the strain of night patrolling, were given some burdensome tasks and for a time subjected to less pleasant living conditions than the 2/13th; at the end of October, however, they moved to the Wadi Auda, known as Tobruk’s most verdant place but, because of its water-installations, one of the most bombed. The 20th

Brigade headquarters and the attached rearguard details from the 9th Division headquarters established themselves in the next wadi to the west, the Wadi Tberegh, which was more peaceful.

The Australians left in Tobruk accepted their disappointing situation philosophically. A soldier in the 2/13th wrote these verses which became the unit song-

O, we’re Bull Burrows’ Bomb-Happy Boys

Back up the line we must go!

Once we were heading for Alex so fair,

Something went wrong and we didn’t get there. ...4

And a ballad writer of the 20th Brigade headquarters wrote:–5

“The last of all to leave Tobruk” –

We felt like heroes – donned our packs,

We gave away our primus stoves

And strapped equipment on our backs;

We said: “It’s something to achieve

To be the very last to leave.”

We waited gaily on the wharf

The inky darkness peering through,

Some thought they saw the ships arrive

Before they’d even passed Matruh;

But soon we learned the game was crook –

It seemed we wouldn’t leave Tobruk. ...

Sometimes we even start to think,

When in depression’s deepest throes,

That we are doomed to stay in here

Till Angel Gabriel’s trumpet blows,

And Peter, taking one quick look,

Says: “Enter! Last to leave Tobruk!”

The enemy’s activities on other sectors and the conformation of his newly developed localities were evidence of the continuation of trends apparent in the last weeks of the 9th Division’s command. The shift of operational pressure from the west to the south and east continued. On the last day of the divisional relief it had been reported that the small outpost at Cooma had disappeared and must be presumed lost. On the night of the 27th the party reappeared after an absence of nearly 48 hours, but also on that night enemy infantry accompanied by tanks were seen advancing on foot on the left of the Essex Battalion, which had replaced the 2/17th in the El Adem Road sector. The enemy approached within 300 yards and were then engaged by the infantry. Another party of enemy infiltrated through the wire at R51 and were inside for half an hour; no such penetration, so far as was known, had occurred since the full-scale assault on Medauuar in May. A few hours later two enemy were observed tampering with the perimeter wire close to R47.

Before the 9th Division departed, it had been presumed, from observations of the different behaviour by the troops opposed to the Polish

Brigade, that an enemy relief had taken place in the Salient. It was now thought that Italian troops might have replaced Germans there. This seemed to be borne out when it was observed that German artillery units had left the sector while batteries of similar guns had appeared in the south-east.

On the 28th the 1st RHA reported that the enemy was busily registering targets – various forward posts – elsewhere than in the Salient while simultaneously the Salient was heavily shelled. Reports of these developments and particularly of the new patrolling pattern in the south-east caused Brigadier Murray concern. He suggested to fortress headquarters on the 28th that the 2/13th Battalion and the companies of the 2/15th should be organised into a composite reserve force and stationed at the vital junction of the El Adem and Bardia Roads, where they could serve as a back-stop against irruption from the south-east. The suggestion was rejected.

The first fortnight of November brought no notable change in the situation. One night the Polish Brigade staged a demonstration assisted by an artillery bombardment and an effective smoke-screen. It evoked an attractive display of flares of all colours from the enemy and a return fire of most satisfactory volume from guns firing from all angles. Special arrangements had been made to plot battery positions by flash spotting. On the night of the 9th the 1/Durham Light Infantry made a courageous attack on Plonk, but with a sad outcome. Though supported by three regiments of 25-pounders and a squadron of tanks, the attackers were handicapped by a difficulty experienced in earlier attacks: sufficient artillery was not available to neutralise both the objective and its flanks. The infantry were caught by flanking fire on the approach and, failing to keep up with the barrage, were badly cut up by small-arms defensive fire and booby-traps at the wire, which they failed to get through. Eight men were missing and fourteen wounded.

The enemy continued his close reconnaissance of the south-eastern perimeter. On the night of the full moon an infantry party 30 to 40 strong approached the wire between R63 and R65, a region in which the anti-tank ditch was only four feet deep. Some got into the ditch but withdrew after being engaged by the infantry on the perimeter. Six nights later, on 10th November, about 40 Germans were discovered inside the perimeter near Post R53. They were contacted by two platoons of the 2/Queens and driven off. One of the enemy patrol was killed and another captured. A week later the German 2Ist Armoured Division was reported to be due south of the south-eastern perimeter at a distance of less than nine miles – as the diarist of the 1st RHA recorded, “presumably to watch Tobruk more closely, possibly to launch an attack”.

By the second week in November it was generally known in Tobruk that another offensive from Egypt with the object of raising the siege would be mounted very soon. On 7th November the 1st RHA was withdrawn from sector defence responsibilities into divisional reserve and was made fully mobile; many other units had to hand over vehicles to make this

possible. Preliminary reconnaissance and engineering work indicated that, as in the plans for BATTLEAXE, a garrison sortie in the south-eastern sector was projected.

To the Australians still in Tobruk the garrison’s role in the offensive was of less interest than the enemy’s intentions in the meantime. On 5th November sub-unit commanders had been informed that the remaining units and sub-units would be leaving in the convoys of the November moonless period. The 2/13th was warned that half of the battalion should be ready to leave by the 13th – a date which some of them did not deem well chosen; the remainder, including the forward companies, would leave two or three days later, after their relief by the Polish Officers’ Legion had been effected.

During the succeeding week there was a revival of enemy high-level and dive-bombing attacks on artillery positions and forward defences and there were more reports of probing enemy patrols near and within the perimeter, which contrasted sharply with his normal conduct at night as experienced over six months. Apprehensiveness grew as to what he was plotting. Then one day Burrows was summoned to fortress headquarters. On the next, the 13th, he called a conference of his company commanders and informed them that the battalion’s departure from Tobruk had been deferred till the night of 19th–20th November. In the meantime the battalion would have a role as part of the reserve in operations connected with the offensive from the frontier. When the garrison’s sortie was made, the battalion was to be split in two – one half to remain to defend the perimeter by the coast, the other to go to Pilastrino to take up a back-stop position. The battalion was to leave Tobruk not by sea, but by land, it appeared, after the garrison had linked up with the frontier forces. The clock-like precision of the predicted timing was received with some scepticism.

Whereas the general outline of the projected operations was accepted readily enough (wrote an historian of the unit) dates had ceased to be significant; the “push” that had been promised for so long would have to be seen to be believed.6

On that night, and the next, all Australians remaining in Tobruk except the 2/13th Battalion were taken out.

Some mystery still surrounds the decision to leave the 2/13th in Tobruk for the CRUSADER operations. One of the few certain facts is that General Sikorski, the Polish Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief, who was then visiting the Middle East, requested that the two companies of the Officers’ Legion with which it had been planned to man the sector of the perimeter where the 2/13th was rendering vicarious service should not be sent to Tobruk. Sikorski desired that they should be held at base where the officers would be needed because of plans to form new Polish divisions in the Middle East. General Headquarters had the request under consideration by 8th November.

Hence the Poles who were to relieve the 2/13th did not come to Tobruk. It may be presumed that General Scobie would have been unwilling to release the 2/13th Battalion until a replacement was forthcoming. Morshead’s advice that the garrison should be reinforced with an additional brigade group if it was to make an offensive sortie had not been heeded or, if heeded, not accepted by the General Headquarters; to have adopted it would have created other supply, transportation and order-of battle problems for the Middle East Command which, however, were not insuperable. The result, whether the reasons for not reinforcing were sound or unsound, was that Scobie’s forces would be fully extended to effect the proposed sortie and his reserves depleted, as indeed his plan to block the key Pilastrino pass-head with but two companies of the 2/13th abundantly illustrated. It was decided that the 2/13th should stay.

There is no record that AIF Headquarters was consulted about that decision or agreed to it. If there was such a reference, it is curious that G.H.Q. did not preserve a record of it. It would be even more curious if any officer of the AIF had granted authorisation on a question that had been negotiated between governments at the Prime Minister level, without carefully ensuring that the decision, and the circumstances in which it was taken, were fully recorded. General Blamey was not in Cairo, having been recalled by the Commonwealth Government to Australia for consultation. The better inference, but only an inference, is that General Headquarters decided not to seek Australian concurrence but to present AIF Headquarters with a fait accompli.7 After all, the deferment of the battalion’s departure was for only a week.

Only a week! There is no reason to suspect General Scobie of being insincere when he informed the 2/13th that it was to be sent out by road on the night of the 19th–20th November. That he should have thought there was a reasonable prospect of this reflects the optimism imbuing the British higher command with which Scobie had doubtless been infected in the course of the deliberations in which he had taken part before coming to Tobruk. The reborn army’s confidence in the likelihood of success was never again surpassed – not even before El Alamein; fortunately so, for it was dangerous over-confidence.

Some explanation must be sought for such excessive optimism. Paradoxically it appears to have been born mainly of past failures. It had become the custom to attribute British defeats in the many reversals hitherto suffered by Allied arms to the fact that battle had always been joined in inferior force, that it had not yet proved possible to confront and fight the enemy on equal terms because he had started so many laps ahead in the armaments race. How often had it been said of the

Tommy, the Digger, or the Kiwi, that man for man, he was the equal of his opponent, if not superior! When such had been proved the case, as often it had, it had been important for the maintenance of morale to stress the fact; when such had not been the case, it had still been found expedient to explain failure by attributing it to the arms, and not to the man.

This sentiment pervaded a message published to all troops who were to take part in the offensive – whether from Egypt or from Tobruk – in which the British Prime Minister said that he had it “in command from the King” to express His Majesty’s confidence that they would do their duty “with exemplary devotion” in the approaching important battle, in which the Desert Army might “add a page to history” which would rank “with Blenheim and with Waterloo”. “For the first time,” declared the message, “British and Empire troops will meet the Germans with an ample equipment in modern weapons of all kinds.”

The word “ample” was a modest description when the British forces’ equipment and administrative resources were compared with the enemy’s. Did not the British have twice as many medium tanks as their adversaries – sufficient tanks, in fact, to allot infantry support roles to the cumbrous Matildas and Valentines and still leave the armoured divisions with a comfortable majority of fast tanks for the engagement and defeat of the enemy armour? In artillery, did they not have a like superiority in the number of guns?

–:–

At midnight on 26th–27th September 1941, General Cunningham’s Western Army Headquarters became Headquarters Eighth Army. Simultaneously Western Desert Force went out of existence and XIII Corps, its successor, was born. Within a few days a new armoured corps was established which, on 21st October, became XXX Corps. Thus a command structure of one army headquarters and two corps headquarters was established.

General Cunningham produced his first plan for operation CRUSADER on 28th September. The plan was much debated and to some extent redrawn before the Eighth Army moved forward into battle seven weeks later; but its main conceptions changed little.

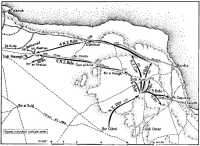

Cunningham was not one to write “approved” to somebody else’s plan. “There are two courses open to us,”8 Auchinleck had earlier written: one, a main thrust along the line of the inland oases, bypassing Tobruk, to the enemy’s rear, “whilst maintaining pressure and advancing as opportunity offers along the coast”; the other, a main thrust near the coast south of the escarpment, with two feints “from the centre and south”. Cunningham chose a third course; historians and critics have suggested others. Cunningham’s plan was to isolate, pin down and cut off the enemy positions by the coast, to feint along the line of oases towards Benghazi and to thrust with the main striking force south of Maddalena – which was perhaps about the direction of thrust Auchinleck earlier had in mind when he wrote of feinting “from the centre”.

The 1st Army Tank Brigade of Matildas and Valentines – approximately 145 of them – was assigned to the northern or coast force, to work in conjunction with two infantry divisions, the New Zealand and the 4th Indian. This force was the XIII Corps, commanded by Lieut-General Godwin-Austen.9 It had the pedestrian role of prising out the enemy ground troops expected to be left stranded in the forward defences by the battle-tide’s ebb when others had won the victory.

Cunningham’s plan allotted the decisive roles to the three armoured brigades10 equipped with 500 fast medium tanks – American Honeys, British Crusaders and older British cruisers – whose ingress into enemy-held territory was to be made well to the south of Rommel’s fortified line that stretched from Salum to Sidi Omar. Lieut-General Norrie,11 then commanding the 1st Armoured Division in England, had succeeded Lieut-General Pope as the commander of XXX Corps (which was to be the armoured striking force) after the plan had been framed.

The command structure bestowed on Cunningham, comprising an army headquarters, an armoured corps headquarters with a specialist signals organisation for communication with armoured formations, and an infantry corps headquarters with normal signals organisation, almost invited, if it did not predicate, a separate employment of the armoured and infantry formations. The decision to employ the infantry corps near the coast and the armoured corps in the south after outflanking the Salum-Sidi Omar line in itself divided the army’s strength. But the fact that the two corps were to be deployed so distantly from each other that they could not be mutually supporting induced a further subdivision. Cunningham’s plan provided for three forces: a northern force, as already described; a southern force, under the command of the armoured corps, to consist of the 7th Armoured Division (including two of the three armoured brigades), the 1st South African Division of two infantry brigades and the 22nd Guards Brigade, with additional anti-tank artillery and medium artillery; and a centre force comprising a reinforced armoured brigade, which was to operate between the northern and southern forces.

In Cunningham’s first plan the centre force was to be initially under the command of the XIII Corps. This revealed its primary purpose: to protect the flank of the infantry corps. General Norrie was a contemporary critic of this detachment. There have been many critics since. Norrie pleaded that the armour should be freed from the obligation of protecting the infantry corps. Neither Norrie nor Cunningham’s other critics, however, had to take the responsibility (political as well as military) of making and executing a plan which might have exposed the New Zealand Division or the 4th Indian Division, or both in turn, to the concentrated assault of two as yet unmauled German armoured divisions. To avoid splitting

his armour Cunningham had either to run that risk or to devise a plan that would entail employing the armoured corps and the infantry corps closer together; but the course urged upon him – to concentrate his armour astride the enemy communications in the El Adem-Sidi Rezegh area – would have meant employing them farther apart. Cunningham’s solution in his final plan was to restore the third armoured brigade to the armoured corps but to give to that corps the additional task of protecting the left flank of the infantry corps.

The conclusion General Cunningham drew from the staff’s estimate of the relative tank strengths of the opposing armies (“about 6:4 in our favour”) was thus stated in his “appreciation of the situation”.

It should be our endeavour to bring the enemy armoured forces to battle under conditions where we can concentrate against them a numerical superiority in tanks. Our armoured division [i.e. of two armoured brigades] will not have this superiority if faced with both the enemy armoured divisions, and one of our armoured brigades is weaker than one enemy armoured division. In order, therefore, to produce a superiority of tanks against the enemy, as long as the enemy divisions are within inter-supporting distance of each other, a similar condition must apply to our armoured division and our remaining armoured brigade.12

This states the principle Cunningham planned to follow more accurately and less unjustly than the impromptu statement attributed to him in a British narrative which it has become the fashion to quote in derogation of the general:

[The enemy] must either concentrate his armour to defend Bardia or Tobruch, or divide his forces. If the enemy split his forces we could split ours.

The comment was no more than a recognition of the truism that if from each of two unequal quantities the same amount is taken away, the disparity of the remainders is increased (to the advantage of the stronger), or in the instant case that two British armoured brigades against one German armoured division gave better odds than three against two combined; but it is hardly just to quote it as implying that if Rommel were to employ his two armoured divisions in different directions, Cunningham intended as a matter of course to divide his own armour. Rather he was arguing that the enemy could not gain an advantage by splitting his.

Cunningham’s final plan called for a triangular deployment of the three armoured brigades around Gabr Saleh, a convenient name on the map near the junction of the track from Bardia with the Trigh el Abd. An armoured force so disposed behind the enemy fortified line from Salum to Sidi Omar could strike north-west to Tobruk, north-east to Bardia or due north to cut communications between the Tobruk and Bardiafrontier zones, seizing supplies stored between the two fronts.

If the object of the excursion was to fight the enemy on ground of one’s own choosing, Gabr Saleh may have appeared a curious and indifferent choice; but the real reason for selecting it seems to have been that to be disposed there was the most threatening posture the armour could take up and still meet (or meet half-way) Cunningham’s requirements

that the three armoured brigades should be kept “within inter-supporting distance of each other” while simultaneously protecting the flank of an infantry corps charged with the task of containing the enemy’s frontier forces.

Of no less importance than the dispositions postulated by the plan which, if they had been adhered to, might have served well enough, were the basic concepts that underlay the thinking of the commanders and which were to exert a more potent influence on their actions than Cunningham’s “appreciation”. First there was the confident assumption that the destruction of the enemy armour would readily result from its engagement. “If all enemy armour is brought to battle,” wrote Cunningham, “the conquest of the rest of Cyrenaica should not be difficult or slow.” Hence “the essentials of a plan” as Cunningham saw them were not what a Tobruk defender would have expected:

(i) The enemy armoured forces are the target.

(ii) They must be hemmed in and not allowed to escape.

(iii) The relief of Tobruk must be incidental to the plan.13

Another opinion expressed by Cunningham was that “the relief of Tobruk would mean much more to [the enemy] than the loss of Bardia-Salum”. From this observation the conclusion was drawn that the way to bring to battle the reluctant German armour seeking “to avoid meeting superior armoured forces” was to develop a threat in the Tobruk area. This belief was very widely held. “What will make enemy move out to meet us?” asked General Auchinleck, and answered his own question: “An obvious move to raise siege of Tobruk.” It seems to have occurred to nobody that General Rommel was not one to abandon his own forces to destruction and that a serious threat to his frontier garrisons might have been no less efficacious.

Evolving naturally from the premise that “the enemy armoured forces are the target”, the “seek out and destroy” terminology employed to denote the task of the armoured corps exerted its own influence. Writing later but echoing words Cunningham had used in his written instructions to Norrie before the battle, General Auchinleck thus described the initial role of the armoured forces:–

The three armoured brigades were concentrated in the 30th Corps and General Norrie was instructed to seek out and destroy the enemy’s armour.

The phrase may have induced a happy hunting mood. It was hardly likely to call forth the restraint and imperturbability needed to bring the enemy to battle on ground one has both chosen and got ready.

The exercise of military command becomes real when the commander passes from stating a general purpose to determining courses of action that will accomplish it. But the proposition that the enemy armoured forces were the target was a notion from which neither a plan nor a guiding principle could be derived for the very reason that the target was mobile.

Although Cunningham may have intended not only to stage-manage the first clash but also to provide a new formulation and fresh impulse at every turn of battle, the possibility that his forces might be committed as a result of decisions neither of his own making nor impressed with his will was inherent in the way he conceived the “essentials of a plan”. With the precept “seek out and destroy” ringing in their ears, subordinate commanders were hardly likely to wait upon definitions of a master plan before engaging.

To exhort subordinate commanders to seek out and destroy their enemies might not have worked disastrously if they and the formations they commanded had been more than a match for their opponents, but experience was to prove that they were outmatched. Comparisons of the quality and quantity of each side’s equipment, showing for example that the British had more but the Axis heavier guns or that the British were the stronger in tanks, the Axis in anti-tank guns, do not provide the main reason, which was that the Germans had, but the British lacked, a sound tactical doctrine for the employment of armoured forces. A separation of the operations and training functions at the higher levels of the British command structure may have contributed to this lack, for in the employment of armoured forces the commanders consistently failed to practise what the training staff had preached. The cardinal difference was that the Germans fought their tanks in close conjunction with guns and other arms whereas the British, notwithstanding that their tanks mounted a lesser variety of weapons than those of their opponents, for the most part expected their tanks to fight with little aid from other arms, except in set-piece operations. What this meant in practice is well illustrated by some comments made by the South African historians:–

The artillery of the British 30th Corps comprised one hundred and fifty-six field-guns. ... Even if the infantry formations be excluded – and if their artillery is not to be taken into account, why were they in the Corps? – 7th Armoured Division alone could muster eighty-four field-guns against sixty 105 and 150-mms of D.A.K.14 However, when the Crusader operation came to be fought out in November of 1941, each British armoured brigade was committed separately, and 4th, 7th and 22nd Armoured Brigades went into action with twenty-four, sixteen and eight field-guns respectively. The sixteen mediums of 7th Medium Regiment R.A. were not with the armour at all, but had been assigned to 1st S.A. Division. ... 7th Armoured Brigade had sixteen field-guns and four 2-pounders, and in the critical midday battle of 21 November this Brigade, less a regiment of its tanks, was called upon to engage the whole of D.A.K., which controlled forty field-guns, twenty mediums, sixty-three 50-mm and twenty-one 37-mm anti-tank guns – to say nothing of the 88s and the lighter anti-aircraft artillery.15

Not only did the Germans bring more guns to the fray. They had better anti-tank guns, they used them to better advantage and, as in operation BATTLEAXE, they used 88-mm anti-aircraft guns as anti-tank weapons, which could destroy a British tank from well beyond the reach of its 2-pounder gun.

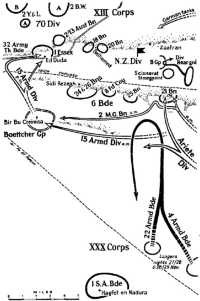

In the first phase General Godwin-Austen’s XIII Corps (New Zealand

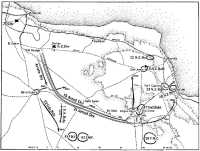

Division, 4th Indian Division, 1st Army Tank Brigade) was to prevent the enemy frontier garrisons from moving east or south while General Norrie’s XXX Corps (7th Armoured Division, 4th Armoured Brigade Group, 1st South African Division and 22nd Guards Brigade) was to destroy the enemy’s armoured forces, employing the armoured brigades, or at least two of them, to do so. In the next phase, after the hostile armour had been destroyed, the XXX Corps, using the South African division (of two infantry brigades) as well as the armoured brigades, was to break the siege of Tobruk by joining up with a sally force from the fortress; it was intended that the South Africans should seize Sidi Rezegh and the neighbouring ridges, the Tobruk forces Ed Duda – while the XIII Corps cleared the enemy from between the frontier and Tobruk. All would then be set to complete the capture of Cyrenaica, reduce the abandoned garrisons on the Egyptian frontier and proceed to the capture of Tripolitania.

That was not the way the battle went. In the first phase the British armoured corps, far from destroying the German armoured divisions, was itself almost destroyed. Moreover, before the German armour had even been encountered, Sidi Rezegh was seized with only one armoured brigade (plus a weak support group) and without the South African division. Soon the area became a battleground on which the German armoured divisions soundly defeated the British armoured formations and overran a South African brigade caught up in the mêlée. The British were thrust from the ground seized.

In the second phase the German armour charged around the battle arena and expended its strength in attacks on the XIII Corps. The latter took over the carriage of the offensive, fought its infantry in conjunction with its tanks (Matildas and Valentines), maintained pressure at the frontier and proceeded to effect a junction with the Tobruk garrison while the XXX Corps for the most part watched from the side-lines, rebuilding its tank strength.

In the third phase, the advance from Tobruk to recapture the whole of Cyrenaica, the British armour which had meanwhile re-established its superiority in numbers of tanks was again defeated. Operations intended to pave the way for an invasion of Tripolitania in fact so depleted British armoured strength that subsequently General Rommel was able to regain the initiative and retake the whole of Cyrenaica west of Gazala, where for a time a stable line between the two armies was established.

–:–

If the time spent by the German commander on reconnaissance in strength in mid-September (Operation “Summer Night’s Dream”) was not entirely wasted, it may be doubted whether his planning was any the better for it. Nothing was discovered to cause any modification of his plan to crush the British outpost at Tobruk which, as a symbol and a legend, was developing a moral significance to match its tactical importance. Nothing, it appeared, but his own intractable supply situation threatened to thwart his ambition to encompass its downfall.

It may have been more than a coincidence that Rommel issued his operational directive for the capture of Tobruk only three days before Hitler, on 29th October, made an announcement foreshadowing German naval and air reinforcement of the Mediterranean theatre and the appointment of Field Marshal Kesselring as Commander-in-Chief South. The German High Command made a serious attempt to achieve Axis supremacy over the seas across which the Germans and Italians supplied and reinforced their African front and the British provisioned Malta. In course of time the Axis supply situation in Africa was to improve to some extent, that of Malta to worsen greatly – a change resulting as much from the diversion of British resources from the Mediterranean and Middle East to the Far East as from German reinforcement of the region. But it was a gradual change, and for the rest of that year, when the supplies received by either army would influence the outcome of British efforts to raise the siege of Tobruk, the rate of delivery to Rommel’s army was not increased but on the contrary halved. During the summer and autumn the supplies reaching the Axis forces in North Africa had averaged approximately 72,000 tons a month; of those sent about 20 per cent were lost on the way. But in November only 30,000 tons were received; more than 60 per cent was lost. In December, a month of almost continuous ground fighting, only 39,000 tons were received. British aircraft, ships and submarines all contributed to that result.

The striking British successes in November were due mostly to sinkings by surface ships, in particular by Force K (the cruisers Aurora and Penelope and the destroyers Lance and Lively) operating from Malta, which sank the seven merchant ships of a convoy on 9th November and a large tanker on 1st December; in December most sinkings of Axis shipping were effected by submarines.

The German submarines in the Mediterranean, as already noted, achieved early successes against British shipping on the Tobruk run. Soon they made their mark against bigger quarry and sank the aircraft carrier Ark Royal on 14th November and the battleship Barham on 25th November. These developments greatly intensified the urgent strategic need for the British land forces to secure ground for air force bases in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania.

Rommel’s orders for the capture of Tobruk followed in the main his outline plan. It was hoped to make the attack between 15th and 20th November. The Africa Division (soon to be known as the 90th Light) was to secure the sector of the perimeter bounded on the north-east by the Bardia Road and on the west by the boundary between the Pilastrino and El Adem sectors (which boundary was heavily overprinted on Italian maps of Tobruk then in use by both sides), including a supposed strong-point at the junction of the Bardia and El Adem Roads. After the Africa Division had breached the perimeter, the 15th Armoured Division (100 gun-armed tanks, including the 5 captured Matildas, and 38 light tanks) was to push on to the coast, also to seize the road-pass of Fort Solaro (so-called). The Italian XXI Corps was to “advance to the high ground

west of Tobruk” to prevent a westerly or south-westerly escape of the foredoomed garrison. In deference to General Halder’s requirement that the frontier flank be guarded, the 21st Armoured Division was to be stationed south-west of Gambut, an ambivalent position that did not rule out its employment as a reserve for the attacking force if the assault did not prosper.

Notwithstanding the accumulating evidence of growing British strength and the deterioration in his own supply situation General Rommel adhered with single-minded purpose to his intention to mount this attack. He refused to regard the build-up of the Eighth Army as a ground for cancelling it, and his arguments in general were sound enough. An operation to subdue the fortress, if it succeeded, should be completed in three days, within which time, he maintained, the British could not effectively intervene. In thus limiting himself to only three days of grace Rommel seems to have allowed for the possibility that the British had a proper plan to intervene. But if the British command had such a plan, it was one of its better kept secrets.16

Rommel’s calculation that the unwieldiness of the British forces would vouchsafe him three days free from serious interference was reasonable except in the contingency that the British began to move forward from their holding positions before the attack began, which could happen in either the not unlikely event that they had discovered or inferred that his attack was imminent or the most unlikely event that they had chosen to mount an offensive of their own on the same day or a day or two earlier. What was mathematically so improbable almost occurred. Early in November Rommel was planning to open his attack on Tobruk on 15th November, the very date on which the British forces were then scheduled to cross the frontier for the CRUSADER offensive. On the 11th, two days after the loss of the convoy destroyed by Force K but perhaps not because of it, Rommel’s Quartermaster-General produced a curious document the purpose of which seems to have been to demonstrate that enough supplies were on hand-20,700 tons of ammunition in addition to that held by the frontier garrison and 4,609 tons of fuel (sufficient to last the 28 days ending on 12th December) – to mount an attack on Tobruk, but not enough for a big advance with distant objectives; moreover, because of the British neutralisation of the shipment of Axis supplies the army would have to live on its reserves. Presumably the conclusion to be drawn was: strike while you can; there is enough for a strike against Tobruk but for nothing else.17 Simultaneously Rommel’s Intelligence staff reported that no British preparations for attack, such as the establishment of supply dumps, had been discovered and that the enemy situation had undergone no significant changes. The possibility that the British might

be about to make a serious attack was considered but discounted with the reassuring deduction that they could not get their main bodies forward before the second night or attack decisively before the third morning. The Intelligence staff in Germany also issued an appreciation denying the likelihood of an early British offensive.

Whether by coincidence or not, this flurry of German paper-work coincided with a report by Rommel’s nominal superior, General Bastico, to the Italian Supreme Command drawing an exactly opposite conclusion from the results of ground and air reconnaissance. Bastico’s opinion was that the British were ready and indeed only waiting for the Axis forces to become involved in an attack on Tobruk to launch “a heavy offensive aimed at forcing a final conclusion”.

On 14th November Rommel flew to Rome to attend high-level discussions about the Tobruk attack with the Italian and German staffs. There he appears to have won his point by shouting down his opponents and other doubters, such as Field Marshal Jodl, to whom he spoke by telephone. The formal authorisation of the attack was conveyed to Bastico’s African headquarters and received there on 18th November. The 21st of November was fixed as the date for the assault.

The British offensive, however, had also been postponed. Otherwise the Eighth Army might have crossed the frontier while Rommel was still in Rome. In the months of the summer and autumn the South Africans had found, as had the Australians and New Zealanders on other occasions, that of all the army’s needs few were accorded lower priority by the Middle East staffs than training; greater priority had been given to digging fixed defences in rear areas. At the end of October, the commander of the 1st South African Division, General Brink, reported that he could not be ready for an offensive before 21st November and demanded 21 clear days for training. A few days later he repeated this request to Auchinleck himself, in a conference which the latter held with Cunningham, Norrie and Brink on 3rd November. Auchinleck and Cunningham agreed to defer the opening of the offensive from 15th to 18th November provided that Brink would then be ready. General Brink asked once again

for three more days of training to bring the date of the opening of the offensive to 21 November, but agreed, if this was impossible, to advance into battle on the 18th.18

Thus it happened that the British advanced before the Germans attacked. If Auchinleck had agreed to the further deferment requested by Brink, he might have had to do much explaining to Churchill.

–:–

Although the British plans and outline orders prescribed close coordination between the forces from the frontier and those inside Tobruk, no one seems to have informed the headquarters of Tobruk fortress that the onset of the offensive had been postponed for three days. Yet the garrison had a part to play and, by 6 p.m. on the day on which the Eighth Army would cross the frontier, had to be ready to start preparatory moves for

a sortie at next first light. These timings were based on the optimistic assumption that the British forces might decisively defeat the German armoured divisions in one day, their first in Libya, though it was not really expected that an opportunity to do so would be presented or created before the second day.

Tobruk fortress came under the command of the Eighth Army on 30th October but was to be transferred to the command of the XXX Corps as soon as Operation CRUSADER started. The garrison’s sortie was to be made at dawn on a day XXX Corps would nominate and notify by code word. On every day after the start of the offensive the XXX Corps was to send a code word to fortress headquarters before 6 p.m., which would be either “Tug” (“Don’t attack tomorrow”) or “Pop” (“Attack tomorrow”).

Scarcely a unit in Tobruk was unaffected by the sortie plan, for according to the fashion of the day every combatant formation had either to fight or to feint. Orders were passed down to subordinate commanders in time for them to get their units ready by the appointed day but without time to waste. Command and staff problems were thrashed out over a sand-table model. On 13th November a rehearsal of the main sortie was conducted over similar ground. The infantrymen were inspirited to see the tanks that were to support them in the real show charge through to overrun the imaginary enemy. They were further encouraged when next day the fortress commander addressed them and told them that the sortie, though hazardous, would not be ordered until the relieving British forces had got the better of the German armour.

By 15th November all preparations had been made and from 4 p.m. many were at one hour’s notice to move. But the day brought neither the promised code word (“Tug” or “Pop”) nor any other news of the “push”. On the contrary through the communications network grim warnings were passed that an Axis attack might be impending, in which parachute troops and seaborne troops in rubber boats might be employed. The information received at fortress headquarters indicated that the assault was likely to be made in the western sector near the coast.

At 4 p.m. Lieut-Colonel Zaremba, General Kopanski’s chief of staff, called on Lieut-Colonel Burrows and informed him that divisional headquarters had received information suggesting that an enemy landing on the western beaches supported by parachute troops was possible. The 1st RHA, now fully mobile for the CRUSADER operation, was placed in support of the 2/13th Battalion for the night. Burrows stood his battalion to arms at dusk and established six fighting patrols along the beaches and headlands for almost three miles east of the perimeter. If an enemy force made a beach landing in the battalion’s sector, a code word was to be passed. Captain Graham’s company would at once occupy a defensive position to block penetration.

The night passed without alarms, the next day without news of the Eighth Army’s advance. At dusk there was a similar stand-to, followed by similar protective measures, except that the 1st RHA was withdrawn from the sector to stand by for its part in the CRUSADER sortie, which

the fortress command had to be ready to mount as from that evening. The night was again uneventful except for some rain showers.

Next evening – the 17th – the 2/13th was again required to act as beach night-watchman. There was still no information of either the British drive or the German combined operation. A few more postponements, a few more nights of standing to arms, should suffice, it seemed, to make the 2/13th Battalion utterly miserable. The fact that there was no news from the frontier added to their discouragement; fortress veterans remembered that practically no information of BATTLEAXE had been passed down to them before that offensive’s failure had been announced. But the elements themselves were to complete their discomfiture.

That night above Tobruk the skies which throughout the summer had shed not a drop of rain and had since bestowed only a few token showers were murky with heavy cloud. Lightning sporadically illuminated them. In time, with an accompaniment of thunderclaps, drenching rain fell, wadis quickly became coursing torrents – “letti di torrenti temporanei” as the Italian military maps described them – and crawl-trenches, weapon-pits, dug-outs, and other entrenchments, deep and shallow alike, were soon water-filled. Fieldworks had made no provision for drainage. At the Wadi Sehel pumping station men of the 2/13th Battalion carrier platoon who provided the standing patrol withdrew quickly but not according to plan, while their warning flares and rockets, triggered by torrent-borne debris striking the trip-wires, shot to the sky. Dawn brought a scene that seemed funny to some but not others when Australian patrols were discovered on the enemy side of the Wadi Sehel, waiting for the torrent to subside.

That morning in many of the frontal areas soldiers on both sides abandoned the holes in which they normally took shelter from each other’s shell and shot, and stood about or sat around in scattered groups sprawled across the defended localities like ants flooded out of their nests. If the ethics of war required them to kill off their exposed enemies, a simpleminded solicitude for their own survival induced some deviation from first principle. In the Salient the Poles, fearing that daylight’s disclosure of their plight would invite disaster, were determined to get the upper hand by shooting first. With machine-guns set up in improvised positions, they harassed the enemy as soon as they could be discerned in the dim light.

The enemy did not respond by fire but began to hoist white flags asking for peace. When fire ceased the work of draining their positions and drying their clothes began and enemy went so far as to kindle fire in improvised blanket tents. We took advantage of it to make some warm tea for our troops.19

Some officers of the RHA also made the best of the situation, visiting the Salient as observers “to make some observations which under normal conditions would have been impossible”.

This was the opening day of the Eighth Army’s postponed offensive. One would not have thought so in the western sector of Tobruk where the 2/13th Battalion, like most other units, awaited receipt of the code

word signalling first action to be taken. As the compiler of the Polish Brigade’s Intelligence summary remarked next day:–

The day of 18 of November was marked by exceptional inactivity of the enemy and own troops. Artillery shelling almost nil. ... During the day a sort of truce was established, each side trying to remove the effects of the rain and subsequent floods. After dark the normal conditions became re-established.

On the 20th, however, it was reported in the same publication:

The conditions on the salient yesterday were the same as on the previous day but this morning the old habits became re-established.

Old habits: one shoots to kill, that is.

In Tobruk the relief operations had no dramatic beginning. The garrison did not see the Eighth Army’s westward advance on wheels that caught the imagination of those who took part, firing them with the eager confidence of men who believe they belong to an invincible army. One heard of a flare-up in another region. In the course of days the wind changed, the conflagration drifted closer; then one’s own ground was threatened; there was real danger suddenly; one was in the fight, in the midst of it. But what was really happening out there beyond the perimeter nobody knew. The prescription for confidence was faith, hope and luck.

To the forces in Tobruk the offensive was an operation which from the start seemed behind schedule and always confused. Knowing their own tasks but not the master plan, conceiving the proposed link-up at Ed Duda with the Tobruk sortie force not as a merely incidental sequel to the planned destruction of the German armour but as the chief objective of the first phase of the offensive, they read the first situation reports with some puzzlement and judged the early progress more halting than audacious.

The code word “Tug” meaning “Don’t attack” was received from the XXX Corps on the 18th and again on the 19th. The 2/13th received its first battle situation report on the evening of the 19th. It gave the dispositions of the armour as at 10.45 a.m. on the 18th (and even then inaccurately, by confusing Bir Taieb el Esem with Gabr Taieb el Esem). So far no British tanks were reported within 30 miles of Ed Duda.

A situation report received on the morning of the 20th purported to depict the situation on the preceding morning. The 7th Armoured Brigade was moving to Sidi Rezegh, the 22nd to Bir el Gubi. The 4th Armoured Brigade had engaged 60 tanks, which had retired northwards. The puzzling part of that report was that the South African division, which was expected to capture Sidi Rezegh at the same time as the garrison sally force snatched Ed Duda, was still deep in the desert south of El Gubi. In the early afternoon the garrison witnessed a fighter sweep by 40 British aircraft; the 104th RHA’s diarist remarked that it was the first time they had seen anything like it. Gun flashes and tracer fire were subsequently seen from the Tobruk perimeter in the direction of Sidi Rezegh. It was reported that a big tank battle had occurred on the preceding day, the British having destroyed 27 enemy tanks for the loss of 20. British forces

from the frontier were obviously in the neighbourhood and it seemed as if the offensive’s objectives were being substantially achieved.

No further report came from the Eighth Army or XXX Corps; but a satisfactory outcome of the tank engagements could be presumed, for the code word XXX Corps sent that afternoon was not “Tug” but “Pop”: the sortie was to be made on the morrow. Through the Tobruk telephone network other code words were passed to set in train all required action.

There was a close resemblance in the routes and final objective chosen and some similarity in the associated deception schemes between the plan devised by Morshead and Wootten for a sortie in BATTLEAXE and that put out by Scobie and Martin for the sortie of the 70th Division in CRUSADER. In fact the decision to seize Ed Duda with a sally force from Tobruk appears to have been adopted (or reborn) at an early stage of the CRUSADER planning. General Cunningham discussed some details of the project at a staff conference on 15th October which General Scobie attended before going to Tobruk to take command there. General Scobie is reported to have agreed to place a squadron of cruisers at General Brink’s disposal for any westward move of the South African division20 after the link-up at Ed Duda. This was advanced planning indeed, perhaps without full knowledge of the mechanical condition of the cruisers Scobie was to inherit or the clairvoyance to foretell that by the end of the first day of the sortie only eight of them would be runners.

The best that can be said of the sortie plan is that in some fashion it worked. Two of its features seemed to commend it rather as a course to take after defeating the enemy than as a way of defeating him. One was the necessity to detach part of the garrison force including practically all its tanks and an indispensable artillery regiment and to employ the detachment so distantly that if it was endangered the garrison would be unable to lend effective aid. The other was the requirement to open up a corridor through enemy-held territory and keep it open; this involved exposing to the enemy two flanks of almost maximum extension defended at almost minimum depth. By simple logic holding the corridor open necessitated later secondary operations to make the flanks safe, in fact a greater commitment than nominally undertaken.

It was assumed that surprise was unlikely to be achieved. The chances of obtaining it were diminished by plans for ancillary operations to precede the main thrust, which were intended to divert the enemy’s attention from the sortie zone to other sectors but, if keenly executed, held promise of alarming and alerting him all round the perimeter.

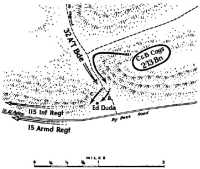

The plan for the main sortie, like many ambitious projects, was in two parts; the first required much doing, the second much daring. In the first phase the striking force was to punch a gap through the encompassing enemy defences, converting the enemy strongpoints to its own use; in the second a mixed column of infantry and armour – the armour leading – was to sweep on to Ed Duda, seize that feature and hold it.

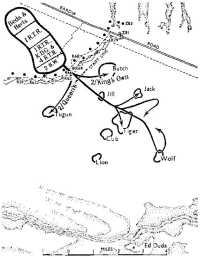

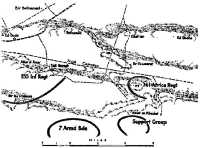

The composition of the main sally force, its order of advance and axis are shown in the diagram. The operation was not just a short attack across known ground to the front of that held. The main objective of the first phase, the strongly held and fortified locality called Tiger, was two miles and a half from the perimeter. The plan required that secretly by night men, tanks, guns, other weapons, stores and vehicles should be got across the perimeter’s anti-tank obstacles and formed up for battle in no-man’s land. For this eight bridges over the anti-tank ditch would be needed. Moreover Tiger was but one of a number of mutually supporting enemy localities. So before Tiger could be attacked, Butch had to be subdued, Jill overrun, and something would have to be done to neutralise Tugun, Lion, Cub and Jack. Then to reach Ed Duda a further advance of about five miles would have to be undertaken.

The first feint, to be carried out by the Polish Brigade in the western sector at 3 a.m., was a series of raids combined with an artillery bombardment. In this operation the 2/13th was to participate with a patrol of one officer and 12 men, which was to demonstrate against a strong Italian defensive locality known as Twin Pimples as though threatening attack while concentrated fire was laid along the front by mortars, medium machine-guns and light machine-guns. Other sorties – one of company strength and two of platoon strength – were to be made on the left of the 2/13th by the 1st and 3rd Polish Battalions. A second diversion was to be carried out by the 23rd Brigade in the area of the El Adem road-block.

The Tobruk garrison’s great assault began with these diversionary operations in the early hours of 21st November. The Polish Brigade’s operation went to plan, woke up everybody, deceived nobody and attracted a satisfactory if not lavish volume of retaliatory fire. The 23rd Brigade’s diversion was quite successful to the extent that its purpose was to make a noise and stir up the enemy; but Plonk, the piece de resistance of the brigade’s task, was not captured.

The sally force’s difficult forming-up outside the perimeter was achieved without interference from the enemy; the roar of supporting gunfire and enemy counter-bombardment from the 23rd Brigade’s false strike drowned the clatter of its assembly. Zero hour for the infantry to advance in the most formidable attack ever made by the Tobruk force was 6.30 a.m. On the left of the sally port and not far out was Butch, which had to be neutralised or the route to Tiger would be murderously enfiladed. It was to be taken by the 2/King’s Own. The centre strike, by the 2/Black Watch, was to be directed at Tiger through the smaller outpost Jill. The left prong was to reach out to Tugun, far to the left flank – an operation assigned to the 2/Queen’s.

At 6.20 a.m. a bombardment of Butch began. Within 10 minutes the 2/King’s Own supported by a squadron of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment (19 Matildas) announced its capture. They reported that the enemy, of whom there were 30 dead, were German and they sent back 10 live ones to prove it. And it soon became evident that this was no isolated

The break-out, 21st November

pocket. A region thought to lie along the boundary of two Italian divisions and expected to be defended mainly by cross-fire from a few strong-points proved to be a German defensive area held in some density by unyielding and determined defenders. Most of these had moved in BqR six days before. Moreover the localities called by code names and delineated in the plans accompanying the operation orders proved to be parts of a more extensive, unmapped and well-concealed defensive system, interlaced with unmarked minefields. Thus an area just to the north of Butch which was not one of the operation’s objectives remained in enemy hands for several days.

At 6.30 a.m., sustained by a regimental tradition reaching back for more than 200 years, the infantrymen of the 2/Black Watch’s assault companies stood up, all to face death, half to die. The tanks were not there, except for a squadron of cruisers not to be employed in the main assault. The time required to get them over the bridges crossing the anti-tank ditch had been underestimated. The infantry commanders made the right decision: to press on alone, making best use of what protection the timed artillery program would provide.

The action developed into a muddle redeemed by great leadership and utmost bravery. Jill, treated in the plan as a small detached post to be easily smothered in the advance of the leading company, proved a strong locality. Each effort of the Black Watch to get forward was murderously cut down until the lately arrived infantry tanks came across from Butch with a company of the 2/King’s Own following. When Jill had been overrun, “there was nothing left of [the leading company of the 2/Black Watch] to carry on to Tiger”.21

When the tanks of the 4th Royal Tank Regiment were assembled on the battlefield, they were unable to proceed because of a minefield to the west and north of Tiger. They were told to make “merry hell”, which they did, with a resounding accompaniment from the guns of “A/E”

Battery. The defence seemed momentarily neutralised and Captain Armitage, who had nosed his armoured command post forward, reported at 8.30 a.m. that he was “on the back of Tiger”, which comprised 1,000 yards of infantry positions dug flush with the ground. The Black Watch were too extended, however, to make the concerted rush needed to exploit a fleeting opportunity, but continued to probe forward to the stirring but melancholy skirling of bagpipes.

Brave work was then done by sappers and men of the King’s Dragoon Guards in clearing minefields. At last a sufficient gap was made and, while “C” Squadron of the 4th Royal Tank Regiment under the brilliant if unorthodox leadership of Major Goschen of “B/O” Battery attacked centres of supporting defensive fire to the east, the tanks of “B” Squadron surged through the gap and right through Tiger. Then, about three hours after the attack had started, the 200 men still remaining of the Black Watch charged forward and captured their objective at the point of the bayonet. Yet there was still work for the Black Watch to do. Machine-gun hail beat down intermittently directed from Jack to the north-east. A weak company was collected and with tanks of the 4th Royal Tank Regiment assaulted and took the place. When Captain Jones of the 104th RHA reported there a little later to establish an artillery command post, he found only a handful of men, sent for reinforcements and personally took charge until a company of the 1/Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire arrived. In another operation, Lion – a defended locality to the south-west of Tiger – was bombarded by artillery and overrun by tanks, but not seized.

Jack was found to be a German battalion headquarters and communications centre. Captured documents showed that the sortie force had struck at the heart of the infantry of Rommel’s assault force, who were all set to go and expected to assault on the morrow;22 the 70th Division’s attack had driven a wedge between the Africa zbV Division on the left and the Bologna Division on the right. There was also evidence that the enemy had been forewarned of the British attack. The warning, it now appears, had emanated from Rommel himself, who had called for three-hourly reports; which suggests that his excellent intercept service may have gathered some clue as to what was afoot.

A subsidiary operation by the 2/Queen’s against Tugun on the right flank, planned concurrently with the main sortie but in insufficient strength, had not succeeded. The 2/Queen’s, reinforced by a company of the Beds and Herts, later mounted a second assault in conjunction with a squadron of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment and managed to secure the eastern end of the locality, but the enemy hung on to the western end.

That morning’s situation report from the Eighth Army, detailing its situation at 9 a.m., had said that the 4th Armoured Brigade was at Gabr Taieb el Esem and the 22nd north-west of Gabr Saleh, both “following up the retreating enemy armoured forces” in a north-westerly direction and that the 7th Armoured Brigade which, with the 7th Support Group,

was at Sidi Rezegh had been ordered to intercept the retreating enemy. An encouraging message from XXX Corps received later in the morning, which indicated that the 5th South African Brigade was ten miles south of Sidi Rezegh, and confirmed that its support of the sortie operations would be forthcoming that afternoon, emboldened General Scobie to proceed with the second phase, the seizure of Ed Duda, notwithstanding the unexpected casualty rate suffered in the first.

The start-time was set first at 1 p.m., later at 2.30. By then the task force had assembled on its start-line, but Brigadier Willison, commanding the 32nd Army Tank Brigade, asked for more time to enable the participation of a number of tanks which had become embroiled in resisting local counter-attacks and in mopping-up operations in the corridor. Even after a postponement, he would only be strong enough, he said, if the attack were synchronised with operations by the South Africans. The postponement was agreed to. Shortly before 4 p.m., just as Willison’s force was making ready for its delayed start, another message came from the XXX Corps suggesting that the operation be postponed because it would be impossible to provide support for the operation against Ed Duda owing to an armoured battle 16 miles to the south-east. Scobie, impressed no doubt by the apparent resilience of the retreating German armour, cancelled the sally.

It had been a day of great achievement. A wedge three miles deep had been driven through one of the strongest sections of the encircling defences. To secure the corridor against sniping and cross-fire, further operations would be required, but it was already possible for garrison forces to debouch into the open desert, whatever perils might lie beyond. Five hundred and fifty German prisoners (including 20 officers) and 527 Italian (including 18 officers) had been taken, but at great cost in loss of life. In the 2/Black Watch alone, there were 200 dead.

Next morning (22nd November) another message was received from the XXX Corps stating that their own troops at Sidi Rezegh were being heavily attacked. “Please attack Ed Duda as soon as possible,” the message importuned, “and shoot up enemy tanks now on Trigh Capuzzo.” This was not the kind of sortie General Scobie’s planning had envisaged. He signalled that his heavy tank strength was much reduced and that if the operation failed, the safety of the fortress would be endangered, but added: “Will attack Ed Duda if you wish. Request immediate orders.” The XXX Corps replied just after midday “Do not attack”, adding with inverted logic “Situation improving”.

–:–

In the CRUSADER planning the prerequisite for the sortie to Ed Duda was the defeat of the German armoured forces but on that day the British 7th Armoured Division was staring defeat in the face. The execution was to take place on the morrow.

As the great British army of the desert had set off westwards on wheels to cross the frontier, the storms that had caused torrents to flow in the wadis of Tobruk had swept towards the advancing forces, flooding air-

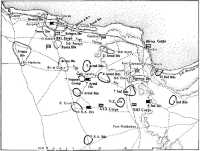

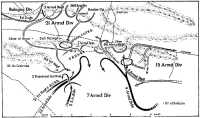

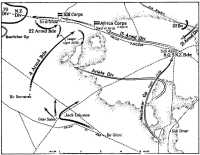

Dispositions, 18th November

fields and grounding aircraft in the operational zone. No aircraft had reported to the German armoured group commander (General Rommel) the size of the British force coming towards him, or even detected its presence. The British formations moved on the 18th to their designated first objectives unopposed except for one or two skirmishes with light enemy screening detachments. Never in a large operation had tactical surprise been more completely achieved since Gustavus Adolphus crossed the frozen Baltic; never had it been achieved to less purpose. So well had the British command and the elements concealed the move intended to provoke a disconcerted enemy to self-destructive reaction that none ensued. The old campaigner Rommel was not put about by early, scary reports of the magnitude of the British incursion and declined to authorise any counter-measures that might interrupt his advanced preparations to assault Tobruk.

The wait-and-see, your-turn-next tactic implicit in the Cunningham plan had brought the Eighth Army to a halt. What to do next? Seek out and destroy! While Cunningham deliberated subordinate commanders took the initiative. Late on the 18th General Norrie indicated Bir el Gubi and Sidi Rezegh as likely objectives for the next day’s operations and early on the 19th General Gott, commanding the 7th Armoured Division, ordered the 22nd Armoured Brigade to attack the Ariete Division at

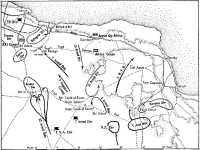

The capture of Sidi Rezegh Airfield, 19th November

El Gubi, which was ground of the Ariete’s own choosing, and well-prepared at that. Honours were about even in the battle. The British lost 25 tanks, the Italians 34, but when the action was broken off the Italians held the ground. Gott also ordered the 7th Armoured Brigade to reconnoitre towards Sidi Rezegh and later to seize a position there, which it did at good speed, overrunning the airfield and capturing 19 Italian aircraft.

Meanwhile the 4th Armoured Brigade had sent the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment with armoured cars of the King’s Dragoon Guards on a foray, cavalry-style, to the north-east. The excursion, which developed into a chase of the German 3rd Reconnaissance Unit, stung the German command into the sort of reaction the CRUSADER planners had visualised. At the instance of General von Ravenstein (commanding the 21st Armoured Division) General Crüwell (commanding the German Africa Corps) obtained General Rommel’s permission to send a reinforced tank regiment (the 5th) to strike at Gabr Saleh. Here was presented the first opportunity of inflicting defeat in detail on the German armoured forces. But at Gabr Saleh there was now only one British tank regiment, the 8th Hussars, with little more than 50 General Stuart tanks, a 12-gun battery of 25-pounders and four 2-pounders. The 5th Royal Tanks were not far to the east, but not exactly within inter-supporting distance. The divisional artillery was not to hand. The battle was joined about 2.30 p.m. and the 5th RTR.

came across in time to join in the fight, which was not broken off until night began to fall. The British armoured brigades, then slightly outnumbering their opponents in tanks, were not disgraced but the German group with its stronger artillery had had the best of it.

The armoured engagements had so far been inconclusive but in the next three days the battle moved swiftly to a calamitous climax. The 3rd Royal Tank Regiment’s jaunt had convinced the German command of the necessity for strong counter-measures, though misleading it as to the purposes of the British and the location of their main strength. The 15th Armoured Division on the coast east of Tobruk was directed to link up with the 21st Armoured Division. Thus concentrated the armour would strike towards the frontier from Sidi Omar northwards, which was not in fact the region threatened by the British armoured force. The 15th Armoured Division’s move would inevitably postpone Rommel’s attack on Tobruk, thus precluding the near chance that the German assault would be launched on the day Scobie made his sortie, an eventuality in which (it is safe to say) the operations of neither side would have gone according to plan.

While the German armour was concentrating, the dispersion of British mobile forces was continuing. The 7th Support Group was directed to move up to Sidi Rezegh next day to join the 7th Armoured Brigade and the South African division was sent to Bir el Gubi to release the 22nd Armoured Brigade so that it could also join the 7th. Before the latter move was executed, however, perturbing reports received by Eighth Army headquarters required a change of plan.

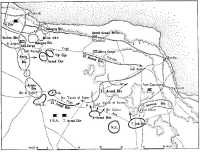

On the morning of the 20th Brigadier Gatehouse23 ordered the 4th Armoured Brigade to advance and engage their adversaries of the evening before. A spirited action ensued, which was broken off by the German commander in conformity with orders for the concentration of his division at Sidi Omar. Then General Cunningham learnt from his intercept service that both German divisions had linked up and were planning to attack the 4th Armoured Brigade at midday. He summoned the 22nd Armoured Brigade to come across from El Gubi, a move which was not completed until late afternoon. At that moment of crisis help from another quarter was proffered to Gatehouse. General Freyberg, whose excellent New Zealand division was at Bir Gibni some seven miles away, could see no reason why it should be kept out of the fight. With General Godwin-Austen’s approbation he offered the division with its complete artillery and its battalion of heavy tanks to Gatehouse, but Gatehouse preferred to fight his battle unencumbered by infantry. So the 4th Armoured Brigade, kept – in Rommel’s phrase – pure of race, made ready to meet its sternest test alone. The attack, delayed and diminished in strength to one division by German supply difficulties, came in at 4.30 p.m. and again the fighting continued until nightfall stopped it, with the 22nd Armoured Brigade joining in before it ended. This second battle between British and German

Situation, 20th November

armour was as inconclusive as the first but at its end the enemy camped on the battlefield, recovering his damaged tanks – none had been destroyed. The 4th Armoured Brigade, which had crossed the frontier with 164 tanks, had 97 left.

That night General Rommel, believing the 4th Armoured Brigade to have been accounted for, ordered both German armoured divisions to proceed at once to the Tobruk front to deal with the British armoured force at Sidi Rezegh. The Germans were no longer doubtful of British plans. The BBC had obligingly informed them. The British command had meanwhile transmitted the code word requiring the Tobruk garrison to break out on the morrow. If the Tobruk garrison and the German forces had both fully carried out their orders next day, Scobie’s small sortie force would have reached Ed Duda about the same time as two German armoured divisions.