Chapter 11: In Palestine, Syria and the Lebanon

The troops brought out from Tobruk in the minelayers and destroyers of the relief convoys disembarked at Alexandria, stayed for about 24 hours at Amiriya and then entrained for the AIF Base Area in Palestine. The 24th Brigade1 and other units, including the 2/12th Field Regiment, the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment and the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion, arrived in Palestine during the last week in September; the brigade went to camp Kilo 89. The 26th Brigade, followed closely by the 20th Brigade,2 arrived a month later; both settled in at Julis. General Morshead arrived at divisional headquarters at Julis on 30th October.

On arrival in Palestine each unit was allowed two days of rest, free from parades and duties. The men received lavish issues of beer and of comforts provided by the Australian Comforts Fund; they relaxed and enjoyed the good food, and the amenities of the permanent camps. Thereafter the normal rigid camp routine was reimposed, units were re-equipped and preparations for training were started. Daily leave to Tel Aviv and Jerusalem was granted on an ample scale. Later, two days of leave were allowed to those centres, and four days to Haifa. Still longer leave to Cairo was instituted for men with sufficient pay credits.

General Morshead toured Syria early in November and on his return went to the Delta, and then to Kenya for a month’s leave. At Alexandria he met Brigadier Murray and elements of the division (other than the 2/13th Battalion) that had been left in Tobruk after the cancellation of the last relief convoy and had just been brought out. At Cairo Morshead was invested by General Sikorski, Prime Minister of the Polish Government in exile and Commander-in-Chief Polish Forces, with the Virtuti Militari (5th Class); the 26th Brigade provided the band and the guard of honour at the ceremony.

Axis agents were said to be attempting to provoke rebellion in Palestine and to be disseminating rumours that British forces there were at low strength. To counter this propaganda the British command instituted patrols to villages and the 9th Division was made responsible for them in the Gaza area. Patrols of company, or half-battalion, strength, led by a band where possible, would march to the outskirts of a village and wait there while an officer and interpreter called on the mayor or mukhtar, inviting him to take coffee with the officer-in-charge and seeking permission for the patrol to march through the centre of the village. Invariably the village dignitary would request an official call by the officer and others, and hospitality would be reciprocated, while the band played in the village. Motorised patrols of platoon strength were sent on similar missions to outlying small villages.

A company of the 2/17th Battalion was dispatched to Broumane, Syria, for guard duties at Ninth Army headquarters. Considerable demands, too, were made on the division to supply guards at base installations. The interference with training entailed in meeting these requirements caused General Morshead to approach General Lavarack, commanding I Australian Corps, with the request that the guards be supplied by base troops. Training, beginning with individual and sub-unit training, soon became the division’s main occupation, with leisure hours often spent in sport. Three Australian crews took part in a regatta at Tel Aviv in which Jewish and Palestinian Police crews participated. Soccer and hockey teams from the 20th Brigade toured Palestine for a week, meeting RAF teams at various stations.

On 20th December the 2/13th Battalion reached Palestine from Tobruk. An elaborate welcome was staged but had to be cancelled because the train was late. The division was now approaching full strength, reinforcements having been steadily absorbed. The divisional cavalry regiment and the 2/8th Field Regiment had rejoined; the 2/7th Field Regiment, however, was still acting as depot regiment at the School of Artillery, near Cairo. The divisional engineers, less the 2/7th Field Company, were in Syria under the command of X Corps. To put into effect an alteration in War Establishments relating to the organisation of anti-tank artillery, the brigade anti-tank companies were disbanded. Members of the 20th and 24th Anti-Tank Companies were absorbed into the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment; the men of the 26th Anti-Tank Company were later taken into the 4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment. The health of the troops was improving, but medical opinion was that they were not yet fit for a 20-mile march or sustained operations.

By the time the siege of Tobruk had been raised, at a cost in men and material so much in excess of every prediction, the Eighth Army’s resources not only of armour and motor transport but also of infantry had become severely strained. On 10th December the Ninth Army was directed to have a division ready to move to the Nile Delta for reinforcement of the General Headquarters reserve. Ninth Army headquarters nominated the 7th Australian Division but requested that it should be replaced in Syria by the 9th Division as soon as the move took place. General Blamey demurred to the latter proposal, pointing out that the 9th Division had been an untrained formation when it had been committed to operations and that it was essential that its training should be undertaken before it was given other duties. General Headquarters did not press the issue, presumably because General Freyberg had already made a proposal to transfer the New Zealand Division to Syria, which had been agreed to.3

The future deployment of the 7th Division, however, was to be determined by events of greater consequence then occurring far from Cairo. The day on which Japanese armed forces had landed in Thailand and Malaya and struck from the air at Pearl Harbour, Wake Island, Guam,

Hong Kong and Ocean Island, had dawned three days before Middle East Headquarters had asked the Ninth Army to nominate a division for the reserve. A fortnight later the Japanese forces were at the Perak River, having captured the northern end of the Malayan Peninsula; a landing had been made in North Borneo; Hong Kong was soon to fall; the Philippines had been invaded. The reinforcement of the Far Eastern theatre had become the Allies’ most pressing strategic problem. It was patent that a call might be made to dispatch from the Middle East any forces that could be momentarily spared (including some or all of the Australian divisions). On 21st December, Middle East Headquarters cancelled the plan to move the 7th Division to Egypt. About a week later new warning orders were issued: to the 7th Division to move to the Gaza area “for training”, and to the 9th Division to relieve the 7th in Syria. General Blamey no longer raised objections.

Early in the New Year the British Government proposed to the Australian Government that two Australian divisions should be dispatched from the Middle East to the Far East and on 6th January the Australian Government notified its concurrence.4 Next day orders were issued for the projected relief of the 7th Division by the 9th to proceed at once.

–:–

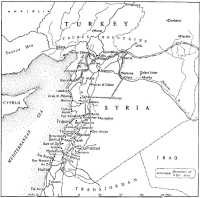

The 9th Division was to relieve the 7th Division in the northern parts of Syria and the Lebanon, assuming operational responsibility for an area exceeding 1,200 square miles adjoining the Turkish border. The 20th Brigade was to relieve the 18th Brigade in the frontier region, the 24th Brigade to relieve the 21st around Madjlaya, three miles to the south-east of Tripoli, and the 26th Brigade to take over in Tripoli from the 25th. Other 9th Division units were to relieve their counterparts of the 7th Division. Advanced parties left Palestine on 9th January and main bodies commenced the move on the 11th, departures continuing daily thereafter until the 18th.

Bitterly cold weather prevailed as the convoys, leaving Palestine, wound their way northwards along the Lebanon coast to Tripoli, and the troops, mostly in open trucks, were too miserable to admire the beauties of an ever-changing landscape – green hillsides, ribbed with whitish rock, which shelved down to a cobalt sea, red roofs topping neat stone dwellings in the villages and the soft azure of distant mountains under a veil of snow, gleaming white at the skyline.

The relief was to begin with the foremost units and outlying detachments on the frontier, so the 20th Brigade was the first to move. On the 13th the 2/17th Battalion reached Tripoli and immediately set out for Afrine, a village about 20 miles north-north-west of Aleppo to relieve the 2/12th Battalion, the 2/13th Battalion followed to relieve the 2/9th Battalion at Latakia and two frontier outposts. The 2/15th Battalion, relieving the 2/10th, arrived a day later. The battalion was quartered in barracks and tin huts at Idlib, less two companies which occupied barracks at Aleppo. Brigade headquarters were established at Aleppo.

Turkey, Syria and the Lebanon

Units of the 24th Brigade arrived in the Tripoli area on 15th and 16th January, and brigade headquarters opened at Madjlaya. The 9th Division headquarters, with Brigadier Tovell temporarily in command, opened in Tripoli on the 16th. General Morshead had gone to I Australian Corps headquarters at Aley, where he remained until General Lavarack, the corps commander, left for Lake Tiberias to embark on a flying-boat for the Far Eastern theatre on the 19th. General Morshead then went with a small staff to the Ninth Army headquarters at Broumane and established a headquarters there to administer command of the remaining corps units still in Syria and to settle claims and finalise contracts made with civilian contractors by the outgoing corps.

The move of the division was completed with the arrival in Tripoli of the 26th Brigade on 18th and 19th January. The divisional artillery (less the 2/7th Field Regiment still in Cairo5) and other divisional units had also arrived and were encamped or billeted in the Tripoli area.

The British occupation of Syria in the summer of 1941 had removed the danger to the Middle East of a German penetration bypassing Turkey to the south, driving a wedge between Palestine and Turkey and building a bridge of entry to the oilfields through Syria; but the threat of an incursion through Turkey persisted. The danger, which had seemed very real in the previous autumn, had abated with the unexpected success of the Russian winter counter-offensive, but it remained to be seen whether the German forces would demonstrate once more their exceptional resilience and prove capable of renewing the advance. Churchill summed up the situation for the President of the United States in a paper prepared in December 1941:

While it would be imprudent to regard the danger of a German south-west thrust against the Persian-Iraq-Syrian front as removed, it certainly now seems much less likely than heretofore.6

How the Turks might react was the crucial question. Much might depend on the military situation in Cyrenaica. Ankara became a focal point of diplomatic activity, espionage and counter-espionage by both Britain and Germany, of some of which lively accounts have been published. The Turkish Government was understandably wary of entanglements. Although an outcome to the war which left Germany the victor might create a threat to Turkish independence, while the prospect of British victory evoked no such spectre, yet a too open collaboration with the British might bring the day of possible loss of independence much closer. Therefore Turkish relations with Britain, though cordial and secretly cooperative, were cautious.7 British arms and equipment were being supplied to the Turkish Army, which, however, was still far from being modernised or able even on its own ground to halt a German Army.

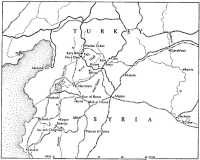

The problem of resisting a German thrust from the north, if it should materialise, was intractable. The strategy followed by the British Government rested largely on the hope that the threat would not materialise. The topography of the northern and north-eastern flank clearly indicated a tactical solution, but political geography and strategy inhibited its execution. The wide mountain barrier stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Persian Gulf roughly in the shape of a boomerang, behind which, between the Black and Caspian Seas, the Caucasus Mountains provided a second barrier, was the obvious ground on which to block a German advance before it could reach the plains of Syria and Iraq. This meant that the battles to defend Syria and Iraq against a German thrust through Turkey should ideally be fought in Turkey. British planners conceived that defensive positions should be held covering the arc Mardin–Diarbekir–Malatya–Maras–Adana, utilising the barriers constituted by the Taurus, Masab and Malatya Mountains.

There were good reasons to hope that, with no immediate threat from the Caucasus, Turkey might actively resist a German invasion from Thrace.

There were reports of reinforcements of Turkish forces across the Bosporus. Such reinforcement, though a good omen politically, the British regarded as militarily unjustifiable. Although there was some fear that, if the Germans seized the Strait of Istanbul by an airborne operation, the Turks might deem resistance to be futile, the consensus of Allied opinion in Turkey was that they would fight an invading force in Anatolia. Several schemes of counter-action had been considered at planning level, some envisaging the employment of armoured forces in Turkey; but, as between the possible courses entertained, the likelihood that the required resources could be made available for any one scheme varied in inverse proportion to its adequacy to meet a serious threat. The least improbable course with the resources available, but also the least propitious one, was a plan to send an air striking force of 24 RAF squadrons accompanied by a “protective” ground force of four infantry brigade groups, anti-aircraft artillery and ancillary troops to Anatolia, where a number of aerodromes had already been prepared for their use and dumps of stores and materials established.8 It is not easy, however, to conceive of circumstances in which even that would have been practicable. Indeed, by the third week of January, General Auchinleck, reviewing the situation in the light of the prospective diminution of his ground and air strength by the dispatch of forces to the Far East, had decided that his resources in the foreseeable future would be insufficient to permit him to do more against a strong invading force than wage a defensive battle on a line through central Persia and Iraq and southern Syria, yielding to the enemy the strategically sited airfields farther north.

The Ninth Army’s plan for the defence of the Suez Canal and the Middle East base from the north, in the event that no advance into Turkey should be undertaken, provided for delaying actions near the Turko-Syrian frontier while the main British forces were to pivot on a system of defensive areas on “fortresses” in the Lebanon and northern Palestine, a scheme of defence which General Blamey strongly criticised.9 The responsibility for the construction and defence of two of these – Tripoli and Djedeide fortresses – had originally devolved on the I Australian Corps, which had also been made responsible for the demolition and holding positions along the frontier.

The responsibility for defence of the Turko-Syrian frontier, and for mounting, if the necessity arose, delaying actions in conjunction with a planned withdrawal on the Tripoli fortress, had now fallen to the 20th Brigade (Brigadier Windeyer), which was deployed on a front extending over 100 miles, not taking into account the distance to outlying detachments around Azaz or to an isolated post on the Euphrates.10 Under brigade

command was the 9th Divisional Cavalry Regiment at Aleppo, less three troops at Djerablous where the Baghdad railway crosses the Euphrates; also the 2/9th Field Regiment, 42nd Field Company RE, and ancillary units, all at Aleppo. Throughout the brigade’s area there were detachments of Free French forces, which were exclusively responsible for patrolling the frontier and primarily responsible for internal security, airfield defence and coast-watching.

The task of the brigade in the event of German attack through Turkey was to cover the withdrawal of base and line-of-communication installations from Aleppo, of the RAF operating from, airfields in northern Syria, and of the Free French forces. Subsequently it would itself withdraw into the Tripoli fortress.

The 2/17th Battalion was on the right flank of the 20th Brigade, with “A” and “B” Companies disposed along the Aleppo-Meidan Ekbes railway from Raju to Meidan Ekbes on the frontier, the main concentration being around Raju to protect the demolitions at the two tunnels and viaduct. It was essential, in the event of an enemy thrust from the north, that the use of the railway be denied to the enemy, and it required protection meanwhile from saboteur bands known to be active there. “D” Company was at El Hammam, a frontier village to the south. “C” Company’s headquarters was at Azaz, to the east and rear of the remainder of the battalion, but still adjacent to the frontier; the company had a section at Sanju on

the Aleppo-Killis road, a platoon guarding the Katma tunnel on the Aleppo-Meidan Ekbes railway and a platoon at Akterin, on the Aleppo-Baghdad railway, some 30 miles across country accessible only by devious tracks.

The brigade headquarters and administrative units were based on Aleppo, as well as the centre battalion, the 2/15th, which was mainly quartered in barracks in Aleppo and Idlib but maintained frontier posts at Bab el Haoua, Harim and Knaye.

From Aleppo to Latakia is about 100 miles as the crow flies, much farther by road, and there the 2/13th Battalion was operationally employed in a detached role, blocking the coast route from Turkey. Battalion headquarters and two companies were encamped not far from the town, one company went initially to Bedriye, a village adjacent to the frontier about 40 miles north-east of Latakia, on the Aleppo Road, and another company went to quarters at Kassab in the mountain fastnesses of the frontier near the coast. Later the outlying companies were drawn back to Latakia for training, except that one platoon was left at Kassab to show the flag to the Turks.

Commanders of formations and sub-units down to platoon leaders were soon busy on reconnaissance. The troops took a keen interest in the country, its historical associations, its customs and the novel and sometimes quaint styles of dress of the inhabitants, with whom they quickly established friendly relations, notably at Afrine where the Kurds were very cooperative and on occasions gave information about the whereabouts of bandits.

Very little work on defences was required and the brigade was committed to a program of training, which, however, the weather during January to some extent frustrated. Storms lashed the coast during the last week of the month; two vessels were driven ashore at Latakia, and tents and huts of the 2/13th Battalion were blown down. Snow fell over most of the brigade area on the 27th, cutting off communication with the frontier posts, except the parties on the railway.

The division held Tripoli fortress, the pivot of the northern defence scheme, with two brigades, the 24th (Brigadier Godfrey) and 26th (Brigadier Tovell), the 24th on the right. The battalions of the 24th Brigade moved into winter quarters on arrival, but maintained sections forward in occupation of the sector defences. The 2/28th Battalion, the right battalion in Section “B”, took over the area previously occupied by the 2/14th Battalion around Srar, one company being in a position 24 miles forward of battalion headquarters. With the exception of the reserve company, movement of the rifle companies had to be completed by pack-mules owing to incessant rain and the inability of vehicles to move on the tracks. The 2/43rd Battalion, based at Arbe, occupied a shorter front on the left of the 2/28th Battalion and were on the eastern slopes of Jebel Tourbol, around Kafr Aya, with the Nahr Barid gorge between them and the forward company of the 2/28th. The brigade’s third battalion, the

2/32nd, was in the reserve area around El Ayoun and took over security duties.

The headquarters of the 26th Brigade, which held the coast sector, were established in the Legoult Barracks, in which the 2/48th Battalion was also quartered. The 2/23rd Battalion occupied the adjacent Beit Ghanein Barracks. The two battalions quartered in barracks sent companies daily to their allotted forward positions to work on the defences; the moves were made on foot owing to lack of transport, causing a loss of two to three hours of working time daily. Later, when tents became available, camps were made in company forward areas. The 2/24th Battalion was under canvas in the foothills east of Madjlaya, two companies moving 10 days later to bivouac in forward positions on the arc, Azge-Kafr Aya-Khlaisse, around the north-eastern and eastern slopes of the Jebel Tourbol, with “A” Company of the 2/48th Battalion in positions on the plateau behind them. Officers and men alike were struck by the similarity of the defences being prepared around Tripoli to those on the Tobruk perimeter. Profiting by their experience in Tobruk, they re-sited some positions and adopted the “Tobruk” type of defence positions in preference to the textbook type.

–:–

The AIF maintained no school in the Middle East to train cadets for commissioned rank. Men chosen for promotion were sent to the Middle East Officer Cadet Training Unit (O.C.T.U.), for which the AIF and other Dominion contingents were allotted a proportion of each monthly intake. The mingling of men from the various components of the Middle East forces in this and other training schools was a potent force in imparting a sense of unity and common purpose to a heterogeneous army.

At the O.C.T.U. the cadets were tested in leadership qualities, given a grounding in tactics and unit administration and smartened up by barrack-square drill in the strictest British Regular Army tradition. The cadets attending in February 1942, who included a due proportion of Australians, found themselves, in addition to undergoing the prescribed course of indoctrination for their future responsibilities, participating in activities not included in the syllabus – the staging of a coup d’etat.

This history is no place to unravel the Gilbertian complexities of Egyptian politics of that day and earlier days. King Farouk, then aged only 22, was believed to have pro-Italian sympathies. The maintenance of a strong government friendly to the Allied cause was of prime importance to the British. The Egyptian Prime Minister, Sirry Pasha, had evinced unexceptional loyalty to the Anglo-Egyptian treaty, but lacked support in the country. The resignation of his Finance Minister at the end of the year had weakened his government. Confronted with a demand for his resignation from the King, who was nurturing and exploiting a grievance at not having been consulted about a recent suspension of diplomatic relations with Vichy France, and troubled by student demonstrations in the streets which were believed to have been inspired from the palace, Sirry Pasha resigned on 2nd February.

The British were not found unprepared or wanting in a situation Machiavelli would have relished. A mixed brigade of British, New Zealand and South African units had already been moved into Cairo to “maintain order” and on the day after Sirry Pasha’s resignation Sir Miles Lampson, the British Ambassador, called on the King and proposed a course that may have surprised His Majesty. It was necessary, he represented, in order to ensure internal security, to have a government that commanded a majority; so Nahas Pasha was the man to appoint, Nahas Pasha, leader of the Wafdists, the traditionally anti-British party whose policy was to rid Egypt of the Anglo-Egyptian treaty and all that went with it – the occupation of Egyptian territory by alien forces and the special “mixed courts” to try suits involving Europeans. The King was not immediately compliant.

At the O.C.T.U., meanwhile, the course of instruction of the Middle East Force’s budding subalterns had taken on a bias for exercises in mobile battle-column tactics, with tanks, such training being carried to the point that a column would be ready to move at 10 minutes’ notice. One day the cadets were told that they would thenceforth practise with live ammunition.

At midday on 4th February Sir Miles Lampson delivered an ultimatum to the King to the effect that the required action to appoint Nahas Pasha must be taken by the end of the day. That evening detachments from the mixed brigade surrounded the Abdin Palace. At 8.30 p.m., the commandant of the O.C.T.U. paraded the cadets, informed them of the ultimatum and of its expiry at 8 p.m. and told them that they were to proceed to the palace to force the issue. Headed by military police, the column, which included light tanks and guns, drove straight to the palace,

pushed open the gate and deployed in the courtyard, while the royal guard ceremoniously presented arms. Soon after 9 p.m. the British Ambassador arrived by car and entered the palace. After about 15 minutes, he returned and drove off. Nahas Pasha was invited to form a government.

Before accepting, Nahas Pasha presented a letter to the British Ambassador in which he said:–

It is quite understood that I accept the task on the basis that neither the Anglo-Egyptian treaty nor the situation of Egypt as a sovereign and independent country permits the Ally to interfere in the internal affairs of the country and particularly in the formation and dismissal of ministries.

The impeccable Government of His Britannic Majesty was only too happy to assent to these irreproachable sentiments, the Ambassador in his reply confirming that it was the policy of His Majesty’s Government to secure sincere collaboration with the Government of Egypt, as an independent and allied country. The excellent compact was democratically validated in elections held immediately afterwards, which the Opposition conveniently boycotted.

Whence the British Government derived its faith that Nahas Pasha would provide the secure, collaborative government so greatly needed may be known only to the inscrutable Sphinx; but the faith was not misplaced. The “Incident of 1942” was shrouded in official secrecy until after the war ended, when it was recalled and became symbolic to Egyptian nationalists of the incompatibility of foreign military occupation with national sovereignty and independence. Britain’s resort to brazen power politics in an hour of crisis no doubt provided impetus after the war to the movement to end the British occupation. But the causes of the movement were more deep-seated, the end inevitable.

–:–

Early in February General Morshead spent five days reconnoitring the 20th Brigade area, after which he visited the Ninth Army commander and, having doubtless in mind the 9th Division’s experiences in withdrawing to Tobruk, expressed his dislike at being compelled to rely for his divisional reserve on a brigade having such a role as that of the one based on Aleppo. It might not get back, he said; and, if it did, would not know the country. Since six weeks’ warning of an invasion was anticipated, why not blow the demolitions early and be assured of getting the brigade back, foregoing any delay that covering the demolitions might impose, he argued. As for covering landing grounds, how long would the air force use them? On past experience, General Morshead contended, they would give them up in the early stages. He suggested that he should leave one battalion in the Aleppo area and withdraw the rest of the 20th Brigade Group to Tripoli.

Morshead was concerned at the lack of opportunities for training afforded troops in the fortress area. Because of slow progress in construction of the defences, the Ninth Army had issued instructions that during February six days a week should be devoted to work on the defences, instead of three days to defence work and three to training as hitherto.

Morshead objected to the new order; he was supported by General Blamey and General Wilson agreed that the training of the division would continue and that civilian labour could be employed under unit supervision on defence works. Morshead noted: “We’ve been digging since April almost and it is of paramount importance that we have time for training. We must also be equipped.”11 He broached to General Blamey “this eternal question of equipment”.12

Another proposal of General Wilson – that the 20th Brigade be employed as army reserve – was also vetoed by General Blamey, who insisted that the command of the complete division must remain with General Morshead.

Except for one day of torrential rain in the 2/13th Battalion area, the weather improved during February and warmed towards the end of the month. The troops were in good health and spirits, and there was little reaction to the scant but sombre news of the Japanese advances and the air raid against Darwin; or to false rumours that Sydney had been bombed; but one remark addressed to the commander of the 24th Brigade reflected a developing uneasiness: “Are you sure we are not wasting our time here? It’s a good spot but they might be needing us at home soon.”

There was some fraternisation between Australians and the Free French forces at command level, but not much below. The relationship could be said to be “polite”. Fraternisation between British and Turkish frontier detachments was encouraged by the former but the Turks would not approach British posts during daylight; after dark, however, they showed themselves anxious to be friendly and eager to partake of Australian cups of tea.

Measures were taken by General Morshead to ensure that the reputation of his troops as a fighting force should not be tarnished by their behaviour as occupation troops. Careful regulation of leave, watchfulness by the divisional Provost Corps who set a high example in dress and deportment, and tight discipline all had their effect, but most troops needed no discipline to force them to conduct themselves well. Unit pride and a strongly-developed pride in the division, which good formation and unit commanders always strove to create, alone sufficed. Two senior officers from divisional headquarters were informed

that the conduct of the troops in Tripoli at the present time is a great credit to Australia. The civilian population in the past have been afraid of soldiers generally, but our troops have impressed them with their bearing, manners and good behaviour to such a degree that civilians are not now afraid but friendly towards soldiers.13

The officer commanding No. 255 Section British Field Security Service, stationed at Aleppo, reported on 31st January:

A good impression has been made on local people by the determination of the new [20th] Brigade to establish a good record for behaviour in public.14

Unsolicited testimony to good behaviour by Australians also came in from some café proprietors and shopkeepers. No longer were continual complaints of the A.I.F’s behaviour being received by the Australian command from General Auchinleck, General Maitland Wilson and the Spears’ Mission. Cases of delinquency of one kind or another continued to occur, of course. At this period the most prevalent offence was that of being found in one of the prohibited villages, which included most of those in the Tripoli area. Later disposing of government property in the flourishing black market was to become the most frequent crime. Severe measures were taken to stamp it out.

Throughout the division, unit tactical exercises were carried out in the field. To free troops for participation in battalion exercises, some minor alterations were made to dispositions in the frontier region and at Tripoli several thousands of civilians were employed on defence works to release troops for training. Nevertheless they were still required to work on the Tripoli defences for three days weekly. Apathy and some positive antipathy to digging tasks were displayed and progress was slow, but the men showed more enthusiasm for training. Firing courses were carried out on rifle ranges in brigade areas and practical wire-crushing training was included, also practice with the new spigot anti-tank mortar. Battalions cooperated with each other in tactical exercises. One battalion would defend its sector of the Tripoli defences against attack by another and at a later date would attack its sector while the other battalion defended it. The troops thus became thoroughly acquainted with the terrain they might have to defend. The 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, having received 32 guns, constructed an anti-tank practice range at Amrit and, by batteries, carried out shoots there. During February cadres from units of all arms proceeded to Australia to help train reinforcements for the division.

Rumours of an imminent German attack on Turkey were reported from the Balkans and it was also reported that Italian officers in Greece had spoken of an intention to stage small-scale raids on the Syrian coast. Although the rumours were suspect and believed to have been disseminated in order to excite British uneasiness for the northern flank while an Axis offence was being prepared in Libya, the 26th Brigade was nevertheless ordered to maintain a mobile group of one rifle company, one section of carriers and one platoon of machine-gunners ready to move at half-an-hour’s notice to reinforce protective detachments at the port of Tripoli and at Chekka.

Troops manning the frontier posts stopped many letter-carriers attempting to cross the border, apprehended Turkish deserters and prevented some

smuggling, particularly of sheep skins, the price of which had risen to such an extent that it was assumed the skins were being procured for winter clothing for German troops on the Russian front.

On 22nd February General Blamey summoned General Morshead to Cairo and informed him that he would become G.O.C., AIF (Middle East) on Blamey’s departure for Australia. Morshead returned to Tripoli and again pressed General Wilson for a third brigade for the defence of the fortress. On 3rd March he returned to Cairo and spent the next three days in consultation with Blamey concerning his future responsibilities. With General Auchinleck, General and Lady Freyberg, and other senior officers of the fighting Services, he farewelled General and Lady Blamey early on the morning of the 7th when they left Cairo airport on their flight to South Africa on the way to Australia. For security reasons Morshead’s appointment was not announced, nor was his promotion to Lieut-general gazetted, until three weeks later. The strength of the AIF in the Middle East at that time was about 45,000 of whom, however, approximately 10,000 belonged to the 6th Division and I Australian Corps and were awaiting embarkation.

–:–

The I Australian Corps, having detached the 9th Division and a proportion of corps units to remain with it in the Middle East, had embarked for the Far East in a succession of convoys from 30th January onwards. The corps commander (General Lavarack) and small parties of officers had flown to Java ahead of the main body. Two days after the fall of Singapore on 15th February, the Australian Government, on the strong recommendation of Lieut-General Sturdee, the Chief of the Australian General Staff, requested that all Australian forces then in transit or about to sail to the Netherlands East Indies should be diverted to Australia, and that the 9th Division and other AIF units in the Middle East should be recalled at an early date. The forces alluded to as being “in transit or about to sail” comprised the I Australian Corps headquarters and the 6th and 7th Divisions and attached corps troops with the exception of a machine-gun battalion and pioneer battalion and other small units (numbering in all some 2,900 men) which had already disembarked in Java. The Australian Government’s reasons for making the request were set out at great length in messages to the British Government. In summary, relying on the wise counsel of General Sturdee who in retrospect is seen to have been less swayed by contemporary crises, and to have made a sounder, more detached assessment of the strategic problem presented by Japanese aggression in South-East Asia and the South-West Pacific than either the British or the American Chiefs of Staff, the Australian Government contended that the policy of the Allies should be to “avoid a ‘penny packet’ distribution of our limited forces and their defeat in detail”, to secure Australia as a base as a first step, to accumulate Allied forces there, and later to lodge a counter-offensive in strength. The background of the request, the dismal weakness of the military forces then

available in Australia to resist invasion, and other relevant facts are related in detail in the next volume of this series. There an account is given of Mr Churchill’s efforts to obtain the Australian Government’s agreement to the employment in Burma of part of the Australian forces (consisting of most of the 7th Division) then moving through the Indian Ocean and of the ensuing conflict between Mr Churchill, strongly supported by the President of the United States and the British and American Chiefs of Staff on the one hand, and Mr Curtin, adopting the advice of the Australian Chief of the General Staff on the other, in which Mr Curtin had his way.

Mr Curtin was informed on 18th February by Sir Earle Page, the Australian representative to the United Kingdom War Cabinet, that the Pacific War Council had recommended that the 6th Division (then embarking in the Middle East) and the 9th Division should be returned as fast as possible to Australia and the 7th Division be diverted to Burma but that before the 9th Division was moved, the 70th British Division should be sent from the Middle East to the India-Burma theatre. It is apparent that what was in contemplation concerning the 9th Division was a return, not in the immediately foreseeable future, but in a matter of some months, after urgent calls on shipping had been met. It was on the next day that Mr Curtin informed Sir Earle Page that the Government had decided not to agree to the diversion of the 7th Division to Burma, but before the decision had been communicated to the British Government the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs informed the Australian Government that an additional American division would be sent to Australia to augment the forces already proposed to be sent there. The Secretary of State asked:–

In these circumstances would it not be wise to leave destination of 6th and 9th Australian Divisions open? More troops might be badly needed in Burma.

On 23rd February, General Sturdee discussed this suggestion in a memorandum to the War Cabinet and urged that the Government should adhere to its decision that both the 6th and 7th Divisions should be returned to Australia. In regard to the 9th Division he commented: –

No date has been mentioned for its departure from Syria and it is most improbable that it could be made available for operations in any country outside the Middle East until late May. ... The date of its departure can be much later if other moves take priority of shipping or the British Government is piqued at the Australian Government’s firm demand for the diversion to Australia of the AIF originally destined for Java. ... The most that I feel we can offer is that the return of the 9th Division be delayed for a short period if the services of an American division is made available.

The Australian Government, accepting Sturdee’s advice, maintained its insistence that the 6th and 7th Divisions should return, and in so doing greatly offended Mr Churchill. Acting on a suggestion made by Sir Earle Page, Mr Curtin then attempted to heal the breach and to show his Government’s desire to be cooperative, without derogation from its overall policy or unjustifiable risk to Australian security, by offering on 2nd March to make two brigade groups of the 6th Division available temporarily for the defence of Ceylon; but he added that the Australian

Government made that offer “relying on the understanding that the 9th Division will return to Australia under proper escort as soon as possible”.

–:–

A shortage of food had developed in Syria to such an extent that it posed a threat to internal security. The Spears’ wheat plan, initiated in the autumn, had for a time eased the situation, but hoarding of wheat and flour and, to a less extent, of other foodstuffs, had continued and caused prices to rise to levels far beyond the reach of the average Syrian. Suleiman Murshed, the Alaouite leader, was said to have a hoard of wheat in his village and a report that he was to receive 200 tons from the United Kingdom Convention Commissioner for distribution among Alaouite peasants in the hills led to some apprehension that this consignment would merely swell his store. A modification of the Spears’ plan was introduced providing for flour to be sold by the U.K. Convention Commissioner to the poorer classes at important centres. This was only a palliative for it did not strike at the root of the trouble by controlling the wartime profiteer. Axis propaganda among the Arabs made much play of price rises and provoked demonstrations.

From the time of their first engagement, all civilians employed on roads, defence works and the Beirut–Tripoli railway had been issued with about 10 pounds of flour weekly to ensure that they would be fit for manual labour. The 2/17th Battalion supervised the issue of 5,000 pounds of flour to the poor in the Raju area which were supplied by the American Red Cross in response to the battalion’s representations.15

–:–

In the middle of March the greater part of the New Zealand Division arrived in Syria. One brigade occupied the Djedeide fortress; another relieved units of the 20th Australian Brigade Group in the Aleppo area. The 20th Brigade then concentrated around Latakia. The 9th Division had thus been relieved of a considerable area of responsibility; there were no longer any Australian detachments east of the Orontes River.

This concentration was effected in pursuance of General Auchinleck’s “plan of deception”. Bearing as Commander-in-Chief a unique personal responsibility for the military security of the Middle East bases, and acutely conscious, as he always was, of the danger latent in an inadequately guarded northern flank, Auchinleck emphasised that it was

of paramount importance that we avoid disclosing our weakness or our intentions to the enemy, to Turkey or to the local populations, because by so doing we may encourage the enemy to attack, drive Turkey into submission, and bring about a serious security situation.16

General Morshead was highly sceptical of the efficacy of the many ruses used to create illusions of strength and wished to see more attention given to getting the men ready to fight. He noted in his private diary:

I am sick to death about the importance attached to prestige and the flying of the flag. All to impress wogs and doubtful Free French!

He told his brigade and other commanders: “We must train the men to give them confidence begotten of knowledge and experience.” The 20th Brigade’s relief from other responsibilities, however, served Morshead’s purposes as well as Auchinleck’s. The brigade immediately embarked upon an intensive program of battalion and brigade field exercises. This was the first occasion on which it had undergone field training, the first occasion in the 22 months since its formation that it had been given an opportunity to conduct exercises in the field with troops.

Morshead became concerned about a field security service report that there was unrest among his command. “Unrest” was perhaps too strong a word to use. Battalion commanders had without exception reported that the morale in their commands was good. Yet evidence that some men were becoming unsettled could not be gainsaid. An uneasiness about their current employment, which had been aggravated by lack of mail from home, was apparent in a number of rumours and stories which, though usually regarded as apocryphal, were continually recounted, such as a supposed accusation by an Australian women’s journal that men were volunteering to remain in the Middle East while Australia was in danger, a rumour that American troops had been sent to Australia and a story that Australian girls had written to men in the Middle East rejecting them in favour of brave militiamen who had stayed to defend their homeland. The sentiment underlying the masochistic repetition of these stories was undoubtedly one of rejection by the men of their role of passive employment in a Middle East backwater. Evolving as it did out of their particular complex situation, it cannot be regarded as indicative of an attitude to circumstances not then existing, such as for example, their further operational employment in Africa.

The AIF Entertainment Unit opened its Syrian tour on 10th March at Beirut with the revue “All in Fun” under the direction of Jim Gerald.17 General Maitland Wilson, General Morshead, the President of The Lebanon, the American Consul-General (Mr C. van Engert) and other notabilities were present. This show, the best the troops had seen in the Middle East, was subsequently played in all Australian areas in Syria. There were also nightly cinema shows in each brigade area. Trips were arranged to the snowfields and places of historic interest and leave to Tripoli and Beirut was maintained. In the evenings, for units not engaged on night exercises, table-tennis, chess, draughts, boxing tournaments and euchre parties were arranged. Short-wave broadcasts of news bulletins prepared by the Department of Information in Australia were re-issued

through the Palestine Broadcasting Service at Jerusalem and Radio Levant at Beirut.

The battalions in the Tripoli area were now engaged in “live out and train” exercises of three days’ duration, carrying out tactical movements by day and bivouacking for two nights under “alert” conditions. The men, appreciating the break from camp or barrack routine, participated keenly, and were stimulated to take an intelligent interest in the manoeuvres by being brought into the picture beforehand and having mistakes discussed and explained to them afterwards.

In mid-April the 20th Brigade was transferred from the Latakia area to Tripoli, where it relieved the 26th Brigade on the coast sector of the perimeter north of the town. The 26th Brigade then became divisional reserve and moved into tented camps among the olive groves around Bech Mezzine, about nine miles south-south-west of Tripoli. The 9th Divisional Cavalry Regiment stayed at Latakia. The battalions of the 20th Brigade marched the 95 miles from Latakia to Tripoli in four days and a half, battalions leaving Latakia on consecutive days and bivouacking nightly. The enthusiastic reception of the troops by villagers along the way indicated a friendly regard for the AIF

Frequent tactical exercises were carried out in the field both with and without troops. One battalion held an exercise relying completely on pack-mules for transport. Another held a four-day bivouac exercise in which Hurricane fighters of No. 451 Squadron R.A.A.F. cooperated. The artillery regiments, when not engaged on the construction of their field positions, conducted exercises and shoots in the country east of Tel Kalliakh, and also participated in training exercises with officers of the infantry brigades. The divisional engineers went by companies to Kishon near Haifa for bridging exercises.

The 1942 grain crop in Syria was an abundant one and more than sufficient for local needs. To ensure that the harvest should not be bought and stored by merchants who had the market cornered, it was decided, with the concurrence of local authorities, that the Spears’ Mission would acquire the crops as they stood and harvest them under military supervision. To this end volunteers with wheat-harvesting experience were called for from the division and the men required were forthcoming, but the division was destined to leave Syria before the harvest.

There was a scare on the night of 24th–25th May. The whole of the 20th Brigade and the mobile and coast defence detachments of the division were alerted. At 9 o’clock it was reported that four boats had landed troops near the Nahr Sene. Later Free French watching posts reported that two warships, probably destroyers, and three fairly large transports were seen moving towards the coast in the vicinity of Arab el Moulk. There were other highly-coloured reports from coastwatching posts but nothing transpired and at 6.30 a.m. the alert ended. Ninth Army headquarters subsequently announced that a British convoy of which the naval authorities at Tripoli had not been informed had been proceeding north along the Syrian coast. Though 50 miles away, the convoy had been visible as

a result of peculiar atmospheric conditions, which included temporary illumination from a large meteor.

The War Office had authorised the granting of 28 days’ leave during the summer to all officers and men serving under British command in the Middle East, with free travel to and from an approved leave centre. Troops stationed in Syria or the Lebanon were not permitted to take their leave in Palestine or Egypt. The Ninth Army headquarters stipulated that the leave be taken in two periods of 14 days. General Morshead authorised leave for the AIF on the prescribed scale but directed that it be taken in seven-day periods in order that as many troops as possible should have some leave before anything could occur to interrupt the program. It proved a wise decision; the scheme had been in operation for only four weeks when the division moved to Egypt. Leave camps were established at Beirut and Damascus, but Beirut was preferred, Damascus being extremely hot and, after a few days of sightseeing, having little to offer. At Beirut the camps were near the city and close to the sea. Cool breezes, bathing and a complete freedom from duties made the stay very enjoyable. Accommodation at the camps was free; but other ranks were allowed a choice of accommodation at reasonable cost at hotels or “pensions” controlled by the Australian Comforts Fund. Ten per cent of each unit went on leave weekly, approximately 1,500 from the division.

In parts of south Lebanon there was evidence of native unrest among the Arabs, some of whom were armed, and the Ninth Army requested the dispatch of a small force to “show the flag”. This was provided by the 2/24th Battalion, and consisted of one rifle company, with mortar, machine-gun, provost and medical detachments; it was commanded by Major Tasker. Its route included the villages of Beit ed Dine, Jezzine, Machrhara, Qaraoun and Merdjayoun, with diversions to Hasbaya and Tyre. Company exercises were carried out in the affected area and close-order drill near the villages. The expedition was away five days.

–:–

Meanwhile, in the desert west of Tobruk where the opposing armies had been sparring with each other around Gazala from static defence lines for more than four months, intense fighting had broken out and the Eighth Army appeared to be in danger of being thrust from its ground. The possibility that the day might not be far distant when the 9th Division, which had seen no action for seven months, might be required to fight again was in the minds both of the planning staffs and of every soldier of the division. To fit it for such a role, training in motorised battle deployment in a desert terrain, which the division had never had an opportunity to practise, was an urgent need. A program for training each brigade in turn was arranged.

On 5th June the 24th Brigade Group, having earlier been relieved by the 26th Brigade Group on the right forward sector of the defences, moved from the Tripoli area to Fourgloss, east of Horns, and for the next fortnight underwent extensive exercises in motorised deployment and movements in “box” formation, bivouacking in the desert at night. No.

451 Squadron R.A.A.F. cooperated with low-level strafing runs. Conditions were exacting; the days were extremely hot and the sun beat down mercilessly on the shelterless plain, from which the vehicles churned up clouds of stifling dust; yet the nights were cold. Hardest to endure of all was the severe rationing of water to three-quarters of a gallon a man for all purposes, including vehicles. One battalion, the 2/28th, alleviated the shortage when it discovered a small wadi showing signs of dampness and, by digging to depths varying from two to six feet, obtained about 1,000 gallons of good water.

At first, formation of unit “boxes” was practised by battalion groups. This was followed by evolutions by the entire brigade group. To see more than 600 vehicles neatly deployed in the prescribed order with a front of 3,500 yards and a depth of 6,000 was most impressive. The artillery units carried out range shoots as well as participating in formation movements. The syllabus culminated in a demonstration in two phases. The first was an attack by the 24th Brigade Group on a simulated German lorriedinfantry column; the second was designed to demonstrate the defensive fire that could be brought down by the group’s supporting arms; live ammunition was fired at screens representing an attacking column. Over 400 officers from British formations and Allied forces watched the demonstration, which was described in a broadcast running commentary.

The group returned to Tripoli on 23rd June and relieved the 26th Brigade Group so that the latter could be released for similar exercises. The 20th Brigade was under orders to follow in due course. In the event only the 24th Brigade completed the training.

–:–

For the British Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East, the most important consequence of the Japanese onslaught in December 1941 had been that reinforcements and supplies intended for the Middle Eastern theatre were diverted to the Far East, and formations already in the Middle East were sent to the new theatre of war, including, as we have seen, the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions. It was in the air that the reduction in strength had most effect on operations in the early months of 1942. By April about 180 bombers and 330 fighters had been dispatched to the Far East.

Partly because his forces were thus weakened, partly because faulty methods of handling tanks and guns still thwarted the Eighth Army’s designs, General Auchinleck was unable to exploit fully, in the six months after Tobruk was relieved, the opportunities afforded by his victory in the CRUSADER offensive. Moreover the problem of sustaining Malta weighed each month more heavily on the Commanders-in-Chief and imposed a severe strain on their diminished naval and air force strength.

After the German and Italian forces abandoned the Gazala line in mid-December, they next stood at Agedabia, in the plain south of Benghazi. British mobile forces entered Benghazi on Christmas Eve, while to the south the Guards Brigade made contact with the German forces on 22nd December. When, on 6th January, the 1st British Armoured Division

arrived in the forward area, the Axis forces retired to the Tripolitanian frontier region. Meanwhile, near the Egyptian frontier the isolated German garrisons at Bardia, Salum and Halfaya were reduced and taken in the first 17 days of January.

Rommel received strong reinforcements of tanks, armoured cars and supplies of all kinds from a convoy which arrived in Tripoli on 5th January, and on the 21st launched a counter-attack which took the British by surprise. The German commander was able to retain the initiative in the fighting that ensued. By 6th February the British had been driven back to Gazala, having lost great quantities of stores and equipment. The 1st Armoured Division, for example, had lost 90 tanks – three-fifths of its full establishment.

At Gazala Lieut-General Ritchie succeeded in establishing a stable line behind a minefield running from the sea to the strongpoint of Bir Hacheim on the desert flank about 45 miles to the south. Tobruk was the forward base and the ridges running back towards Tobruk were fortified against penetration.

The opposing armies maintained a static front on the Gazala line for three months and a half, during which the plight of Malta became ever more desperate. Some success in provisioning Malta had been achieved in January, when the RAF could operate from airfields in Cyrenaica. Of a convoy of four supply ships sent early in February under escort, however, not one arrived. Another convoy bearing 26,000 tons, which was fought through in March with skill, bold action and extreme courage, suffered grievous loss. Only 7,500 tons reached the garrison of Malta.

Malta’s perilous situation underlay a conflict then developing between Mr Churchill, with some support from the Chiefs of Staff, and General Auchinleck. From the end of February the irrepressible Prime Minister brought continued pressure on the Commander-in-Chief to renew the offensive. While Churchill feared that if the Cyrenaican airfields were not recaptured Malta would be lost, Auchinleck averred that to launch an offensive with the forces available would incur a risk of their piecemeal destruction and could endanger the security of Egypt. Eventually the Middle East Commanders-in-Chief were over-ruled from Whitehall and the Prime Minister, in the name of the War Cabinet, the Defence Committee and the Chiefs of Staff, telegraphed on 10th May instructions to launch an attack at the very latest before the June dark-period convoy to Malta.

It had already become apparent, however, that an enemy offensive might be expected before the British forces could be made ready to attack. On 26th May General Rommel launched an onslaught on the Gazala position, thrusting with his armour around the southern flank of the British forward defence line. Although Rommel held the initiative in the first few days and achieved considerable local successes, while the British command repeatedly committed the error of permitting isolated formations to become separately engaged and failed to mount an effective counter-stroke, the Axis forces after a week’s exertions had failed to

dislodge the Eighth Army from its ground and had lost almost one third of their effective tank strength.

In the early hours of 5th June, General Ritchie launched an operation aimed at closing the German armour’s supply route but, after some initial successes, the assault force was repulsed with great loss. Sensing the discomfiture of his enemy, Rommel reverted to the assault. First he concentrated his forces against Bir Hacheim. This strongpoint, on the southern flank of the British position, and now isolated, was held by the 1st Free French Brigade. After a most heroic defence for five days against continuous assault from the ground and the air the position had to be abandoned. The garrison fought its way out on the night of 10th June.

Ritchie still attempted to hold a line from Gazala to Tobruk. The defence rested on a number of strongly-held fortified localities in dominating positions. On 12th June, however, the German armour struck at the British armour in the centre of this line, between the Knightsbridge and El Adem boxes, routed the three British armoured brigades of the 7th Armoured Division and remained in possession of the battlefield. Next day the British suffered further losses.

Ritchie had to abandon Gazala to save his weakened force from piecemeal destruction. General Auchinleck authorised this course, but ordered Ritchie to hold a line west and south-west of Tobruk through Acroma and El Adem and directed that he was not to permit Tobruk to become invested. Whether or no it was practicable to hold the German and Italian forces on that line, Ritchie, influenced, it should seem, by Gott’s advice, made no serious attempt to do so, but withdrew to the Egyptian frontier most of the forces released by the abandonment of the Gazala bastion. Meanwhile Mr Churchill had asked Auchinleck for an assurance that there would be no question of giving up Tobruk. Under pressure from above and below, Auchinleck authorised Ritchie to permit “isolation” of the fortress for short periods. Rommel was in fact allowed to invest Tobruk without interference worthy of remark. On 17th June the reorganised 4th British Armoured Brigade was engaged and completely defeated. Rommel swiftly planned an assault to reduce Tobruk and the British command now lacked the means of effective intervention from outside.

The attack was launched on the 20th. The German Africa Corps assaulted in the south-eastern sector with infantry and about 40 tanks after a heavy dive-bombing and artillery bombardment and the tanks quickly penetrated through to the defenders’ gun-line. By the early afternoon they were bombarding the harbour from the top of the escarpment and by the evening the port was in their hands. Effective resistance or escape being no longer practicable, the garrison commander (Major-General H. B. Klopper), wishing to avoid further bloodshed, surrendered the fortress next morning at dawn. About 35,000 men, including four infantry brigades (two South African, one British and one Indian) and a tank brigade, were taken prisoner.

Most defenders of Tobruk from Morshead’s days have pondered this debacle, asking themselves whether they could have repelled the assault to which Tobruk at last succumbed. That onslaught cannot be directly compared with any they themselves withstood. There were significant differences between Morshead’s dispositions in the south-eastern sector and those adopted by the defenders on that day. The brigade holding that sector had three battalions forward on the perimeter, one – the 2/7th Gurkhas – behind the Wadi es Zeitun. If any of these were overrun, the vital crossroads in rear (King’s Cross) and the road to the port would lie open. Morshead always held one battalion back in this sector, using it, together with a battalion of the divisional reserve, to constitute a second defence line in an arc covering the crossroads. Another battalion (at Fort Airente) could be moved up at short notice from below the escarpment. He insisted that units of the line should not be tied down to the defence of the perimeter on the fringe of the precipitous Wadi es Zeitun, which he held lightly with Army Service Corps spare personnel employed as infantry. Such arrangements, however, though influential, could not of themselves determine the outcome of an engagement such as occurred, in which an armoured force numbering more than 100 tanks (outnumbering the defenders by about 2 to 1) was cast for the decisive role. The speed of the collapse appears to have been mainly due to sluggishness in bringing reserves into battle, and to failure to confine the enemy to a narrow bridgehead.

Immediately after the fall of Tobruk Ritchie withdrew the Eighth Army to Mersa Matruh, and Rommel pressed on in pursuit. By 25th June his advanced elements were in contact with the British forces masking the Matruh defences. On that day Auchinleck relieved Ritchie of command of the Eighth Army, assuming personal command.

The army was now organised as follows: the X Corps (Lieut-General Holmes18) was in charge of the static defences of the Matruh fortress, having under command the 10th Indian Division (which had just arrived in the desert) and the 50th Division. The XIII Corps (Lieut-General Gott) was responsible for the left flank, having under command the remnants of the 1st and 7th Armoured Divisions and the motorised New Zealand Division (less one brigade), also newly arrived. The XXX Corps (Lieut-General Norrie) was at El Alamein, 120 miles to the rear, organising a defensive position with the 1st South African Division and 2nd Free French Brigade Group. On taking over command Auchinleck immediately decreed an extensive re-organisation of formations into battle-groups, of which the basic principle was to use the artillery in a mobile role as the main weapon and the infantry as local defence for the artillery. Whatever the scheme’s merits, its inauguration on the very eve of battle was perhaps inopportune.

Auchinleck decided not to commit the army to the task of holding Mersa Matruh, lest the X Corps within the port’s perimeter defences

should share the fate of the Tobruk garrison. His overriding aim was to keep his force intact. But he intended, by fighting a mobile offensive battle with battle groups in the area between Matruh and El Alamein, to confront his enemy with a novel situation and hoped thus to halt his advance in that region. What occurred, however, was more in the nature of a precipitate withdrawal than an offensive defence. On the evening of the 26th June the German forces made a breach in the minefield south of Matruh. Next day the 21st Armoured Division, passing to the north of the New Zealand division at Minqar Qaim, attacked it in rear (from the east) while the 15th Armoured Division converged on it from the west and the German 90th Light Division cut the road between the British XIII Corps and the X Corps. General Gott ordered the withdrawal of the XIII Corps and in consequence the X Corps was left isolated at Mersa Matruh. The situation was in part retrieved by great gallantry. That night the New Zealand division, in the epic battle of Minqar Qaim, broke through the German ring and retired with little loss to El Alamein. The next night the 50th Division and the 10th Indian Division fought their way out of Mersa Matruh. Although the break-out was successful, these formations suffered severely and had to be withdrawn soon afterwards from the battle area to reorganise.

–:–

News of Tobruk’s fall profoundly shocked the men of the 9th Division, who had so stoutly defended it. To some it seemed that their efforts, and those of lost comrades, had gone for nought. Some commanders addressed their men in an effort to combat their sombre mood. The relentless advance of Rommel’s forces towards Alexandria continued meanwhile and the thought that the division might soon follow the New Zealanders to the desert was ever present.

–:–

At intervals during the three months preceding the British withdrawal to El Alamein, the Australian Government had broached with the British Government the question of the 9th Division’s future employment. In a message to Mr Curtin on 10th March 1942 Mr Churchill had quoted a message from the President of the United States in which the President had informed him that the United States was prepared to send two additional divisions to the Pacific area, one to Australia and one to New Zealand, the decision to do so having been taken, so Curtin was informed, on the basis of (a) the President’s recognition of the importance of the continuing security of the Middle East, India and Ceylon, (b) the need for economising in shipping and (c) the President’s agreement with the British Government’s view that the Australian and New Zealand divisions then in the Middle East should remain there; upon this, it was stated, the sending of the two additional American divisions was conditional. Churchill said that he hoped that in these circumstances the Australian Government would consent to leave the 9th Division in the Middle East: he added that the two brigades of the 6th Division soon to arrive in Ceylon would

be sent on to Australia “as soon as the minimum arrangements for this all-important point can be made”.

Next day the Australian Chiefs of Staff recommended that the proposal be accepted. They pointed out that the American division would reach Australia as soon as the 9th Division could arrive, that considerable shipping would be saved if a move of the 9th Division from the Middle East and another division to the Middle East to replace it were avoided, and that acceptance might hasten the return to Australia of the two brigades of the 6th Division then earmarked for Ceylon.

But the Government did not come to an immediate decision. On 20th March Curtin telegraphed Churchill that the question was still under consideration, being related to other aspects of Australian defence, including naval and air strength. The Australian Government may have been playing for time until it had an opportunity to consult General Blamey, whom it intended to appoint Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Military Forces, but who was still overseas. Blamey was due to leave Capetown by the Queen Mary on 15th March and to reach Australia on the 23rd. There was, moreover, a hint of coercion in this and previous communications from the British and American Governments that displeased the Australian Government, the dispatch of American forces to Australia having been represented (and, in the latest instance, the return of Australian forces in Ceylon obliquely suggested) to be conditional upon Australian agreement to the employment of Australian formations elsewhere. The Government’s objection to this mode of negotiation between cooperating allies was conveyed to the President of the United States by Dr Evatt, the Australian Minister for External Affairs, who had arrived in the United States on 20th March. Dr Evatt subsequently reported to the Government that the President had stated that American forces were being, and would continue to be, dispatched to the Australian theatre unconditionally, and that the Australian Government’s right to decide the destination of the AIF was not questioned.

General MacArthur had arrived in Darwin from Manila on 17th March. Mr Curtin announced next day that the Australian Government had nominated him as Supreme Commander in the South-West Pacific Area. General Blamey’s appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Army was made on the 26th; soon afterwards he was also appointed Commander of Allied Land Forces in the South-West Pacific. Mr Curtin at once consulted General MacArthur on the 9th Division’s future employment. MacArthur advised that the division might be permitted to remain in the Middle East provided that the naval and air strength of the Australian base were augmented: to conserve shipping the aim, in his opinion, should be to move troops from non-operational to operational areas rather than from one operational area to another. General Blamey, however, urged that the division should be returned to Australia as soon as it could be replaced in the Middle East and shipping be made available. The Government’s decision was conveyed to Mr Churchill in a telegram

sent by Mr Curtin on 14th April, in which he alluded to most of the issues involved:

The Government’s view is that all Australian troops should be returned to Australia but it appreciates the difficulties at this stage in giving effect to its wishes, in regard to the 9th Division, owing to the shipping position. ... It is therefore prepared to agree to the postponement of the return of the division until it can be replaced in the Middle East and the necessary shipping and escort can be made available for its transportation to Australia.19

Although on 1st April the Australian Government had received from Mr Churchill an unsolicited undertaking that in the event of large-scale invasion of Australia by Japanese forces the British Government would divert to Australia a British infantry division due to round the Cape towards the end of April or beginning of May and an armoured division that would be following it one month later, the British Government was not willing to provide, in circumstances indicating no imminence of such a peril, the augmented naval and air forces for which General MacArthur was pressing. MacArthur’s immediate reaction was to seek additional land forces, with an eye to those two divisions. On 28th April Curtin telegraphed Churchill that, because additional land and air forces could not be provided from elsewhere, he had been asked by MacArthur to request that the two divisions rounding the Cape be diverted to Australia; the Australian Government, he said, supported General MacArthur’s request. The British Government would not agree; which could hardly have surprised either Mr Curtin or General MacArthur, who then told the Australian Government (on 2nd May) that he felt impelled to ask for the early recall of the 9th Division and strongly recommended that the British Government should be asked to state a definite time for its return. General Blamey supported MacArthur’s recommendation. These representations were communicated to Dr Evatt then in London, who in a reply (dated 8th May) indicated his intention to discuss this and other matters related to Australian defence with Mr Churchill on the following Monday; but succeeding reports from Dr Evatt contained no further reference to the question, and it would seem that no specific request for the return of the division was then addressed to the British Government. On 28th May Dr Evatt suggested that if such a request were to be made, it should be made from Australia. On 30th May General Blamey represented in a memorandum addressed to the Government that a decision on the retention or otherwise of the 9th Division had become a question of pressing importance because general decisions on organisation and the allocation of manpower in Australia hinged on whether or not reinforcements were to be sent to the Middle East. The problem was further discussed at the Prime Minister’s war conferences on 1st and 2nd June, when General MacArthur and General Blamey renewed their requests for the division’s return.

The war situation was rapidly changing, however, both in the Middle East and in the Pacific and discussions initiated when the Allies were devoid of resources to oppose the advancing Japanese forces in the South-West Pacific on land or sea or in the air were being carried on at a time when Rommel’s swift advance was threatening to place the Middle East base and oilfields in more imminent peril than the Allied base in Australia. The losses suffered by Japanese naval forces in the battle of Midway Island from 3rd to 6th June put an end to Japanese naval dominance in the Pacific seas. On 11th June General MacArthur announced that in consequence of the damage suffered by the Japanese Navy in the Coral Sea and Midway Island actions, the security of Australia was now assured. In the desert of North Africa, on the other hand, the development of the battle during June seemed to portend a major defeat, which might even involve the loss of the Middle East naval, military and air bases towards the end of the month. MacArthur and Blamey both advised the Australian Government that it should not press for the return of the 9th Division at that time. Their recommendation was adopted by the Australian War Cabinet on 30th June and endorsed by the Advisory War Council on 1st July.

–:–

Already on 25th June orders had been received at the headquarters of the 9th Division that the division should move to Egypt as soon as possible. Secrecy was to cloak the move and an elaborate deception plan was evolved. No titles were worn, AIF and divisional signs were obliterated, Australian-type hats hidden,20 unit signposts left in position, 9th Division wireless-telegraphy traffic was simulated after its departure, interpreters travelled with units to Egypt and later returned to Syria. Anyone enquiring concerning the move was told it was a training exercise.

Some of the troops averred that their destination was Australia, but as the journey proceeded it became patent that they were bound for Egypt. Few were deceived by the security precautions, not even the inhabitants of Tripoli who scorned any suggestion that the division was going anywhere but to Egypt – had not advanced divisional headquarters travelled south by the coast road? The populace knew, moreover, that tan boots were peculiar to the AIF From the villages of Syria to the streets of Cairo, the troops were greeted with cries of “Good luck Australia”.

The 26th Brigade, first away, left at 6 a.m. on 26th June and travelled by way of Homs, Baalbek, Rayak, Tiberias, Tulkarm, Gaza, across the Sinai Desert to the Canal and Cairo; the whole journey was completed in motor transport. Instructions were received en route that the division would be responsible for the defence of Cairo, but before the main bodies reached Cairo orders had been changed.

Main divisional headquarters and divisional troops left Tripoli on the 27th and, travelling by the coast road and the Sinai Desert, reached Amiriya about the same time as the 26th Brigade. The 24th Brigade Group left on the night of the 27th–28th by the same route as the 26th Brigade

until Tiberias was reached, when the main body was diverted to Haifa to entrain, a road party continuing on by the 26th Brigade’s route. The rail party detrained at sidings to the west of Alexandria in the afternoon of 1st July, the road party arriving some hours later.

The remaining brigade, the 20th, now in the frontier area, was not to move immediately but to await relief by the 17th Indian Brigade. The 2/15th Battalion was dispatched hurriedly by road and rail to Tripoli for the defence of that town, the commanding officer, Lieut-Colonel Ogle becoming commander of Tripoli fortress. Late on 29th June, however, the 20th Brigade received orders from the Ninth Army not to await relief but to move to Egypt early next morning. The 9th Divisional Cavalry Regiment also left Latakia for Egypt that day.

All units got away on their journey at extremely short notice and their onward movement was most efficiently organised by the staffs and units of Ninth Army and the British line-of-communications organisations. Whatever the future might hold for them, the men welcomed the end of garrison duties in Syria.