Chapter 13: Alam el Halfa and “Bulimba”

At the turn of the month the planning of Eighth Army headquarters reflected an unhappy ambivalence, as though the command was as apprehensive as it was hopeful. The respite from offensive operations afforded formation and unit commanders by the lull after the abortive attacks on 27th July was partly taken up by reconnaissances of possible holding areas in rear, and routes to them. Such prudent precautions against unexpected calamity were dispiriting.

Early in August the 9th Division was directed to give up the ground captured by the 24th Brigade on the Makh Khad ridges. The fortifications of the Alamein Box were to remain the main holding positions. Auchinleck’s intention was to reduce the number of troops committed to holding the front; his policy was to discontinue the offensive for the present and to prepare for “a new and decisive effort”, perhaps about the middle of September.

An operation order issued by the 9th Division on 1st August expressed the opinion that the Germans would build up a striking force as soon as possible, which might be ready to operate during the second half of August. The XXX Corps would hold its ground, reorganise to give greater depth in defence and create a reserve for the counter-offensive. The 24th Brigade was to withdraw into the El Alamein Box and the 20th and 26th Brigades were to change places over two nights, the 20th to be in position from Trig 33 to Point 26 by the morning of 3rd August, linking those positions with the El Alamein fortifications and protecting the area with minefields.

Similar reorganisation was effected in other sectors. As the army settled down to undertake a prolonged defence of the ground it held, the 9th Division (with the 50th RTR under command) held the coast sector, on its left the South African division linked with the 5th Indian Division astride Ruweisat Ridge, the New Zealand division held the right flank of the neighbouring XIII Corps and part of the 1st South African was in rear of the 9th.

–:–

In June, July and the first half of August decisions were made in Washington, London and Cairo which greatly affected the future conduct of the war in Africa. When the British Prime Minister and General Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, visited the United States in June, they succeeded in persuading Roosevelt and the American Chiefs of Staff to reconsider their insistence that the main Allied effort in the European war should be a cross-channel operation to be mounted in the autumn. Churchill’s polemic skill compelled notice to be taken of the British thesis that hard facts precluded operations in France until greater forces and resources could be assembled, while on the other hand an

enlargement of operations in Africa offered promise of major victory. In a memorandum to the President of the United States Churchill asked questions that the American advocates of early, direct assault in France found hard to answer. He pointed out that no responsible British military authority had been able to devise a plan to invade Europe in 1942 with prospect of success.

“Have the American staffs a plan?” he asked. “At what points would they strike? What landing craft and shipping are available? Who is the officer prepared to command the enterprise? In case no plan can be made ... what else are we going to do? ... It is in this setting and on this background that the French North-West African operation should be studied.”

Another decision made in Washington was of more immediate import to the Middle East command. The ill-wind that had taken the tidings of the fall of Tobruk to Churchill and Brooke in Washington presented the Eighth Army with a fulfilment of its greatest need in fighting equipment, tanks that could match the best German tanks in gun-range, mobility and dependability, for Roosevelt and General Marshall responded by magnanimously offering to send to the Middle East 100 self-propelled guns and 300 Sherman tanks, which had just been issued to the American armoured division. If Churchill’s past arguments with Wavell and Auchinleck about launching newly-arrived tanks into battle could be taken as a pointer, it would not be long before he would again be calling upon the Middle East command to expedite the mounting of a major offensive.

When Churchill and Brooke returned from the United States, the Eighth Army was about to make what then seemed a last stand at El Alamein. Churchill desired to fly out at once to the Middle East but was persuaded by Brooke to wait till the situation had stabilised. And on 15th July, Brooke obtained from the Prime Minister permission to visit the Middle East alone.

In the next fortnight General Marshall, Admiral King and Mr Harry L. Hopkins visited London to finalise Allied strategy for the year and on 28th July agreement between the two nations to mount an invasion of North Africa and defer the invasion of Europe was at last attained.

Meanwhile news of Auchinleck’s failure at Miteiriya Ridge and his decision to revert to the defensive had reached London. Churchill who was always desirous of making the main decisions in the conduct of the war determined at once that he must himself take the action necessary to put aright what seemed amiss in Cairo. The King and the War Cabinet agreed. Brooke was informed on 30th July, the eve of his departure, that Churchill would be following him to Egypt. Next day Stalin invited Churchill to visit him in Moscow. Churchill immediately accepted and decided to combine both journeys. He cabled Stalin that he would fix from Cairo the date of his visit to Russia.

Churchill also invited Field Marshal Smuts and General Wavell to attend the discussions in Cairo. There was no mistaking the mood in

which the British Prime Minister set forth on his mission. On 1st August he sent the following message to General Brooke at Gibraltar:

How necessary it is for us to get to the Middle East at once is shown by the following extract from Auchinleck’s telegram received yesterday:

“An exhaustive conference on tactical situation held yesterday with Corps Commanders. Owing to lack of resources and enemy’s effective consolidation of his positions we reluctantly concluded that in present circumstances it is not feasible to renew our efforts to break enemy front or turn his southern flank. It is unlikely that an opportunity will arise for resumption of offensive operations before mid-September. This depends on enemy’s ability to build up his tank force. Temporarily therefore our policy will be defensive, including thorough preparations and consolidations in whole defensive area. In the meantime we shall seize at once any opportunity of taking the offensive suddenly and surprising the enemy.”

Churchill arrived by air in Cairo on 3rd August and in the evening conferred with Generals Brooke and Auchinleck. “He is fretting that there is to be no offensive action until September 15th, and I see already troublesome times ahead,” Brooke noted in his diary.1 The main discussion concerned the future command of the Eighth Army. It was agreed that Auchinleck should not continue to combine his office of theatre commander in the Middle East with direct command of the Eighth Army in the field. Brooke proposed General Montgomery as the army commander. Churchill proposed Gott, although, as Brooke commented, Churchill was selecting Gott without having seen him. A round of conferences followed on the 4th. Brooke again pressed for the appointment of Montgomery but the Prime Minister demurred on the ground that Montgomery could not arrive in time to advance the date of the next offensive.

A big strategical problem facing the Middle East commanders was whether to concentrate on holding the Persian oilfields against a possible German advance in the late summer or to concentrate on holding Egypt. “We have not got the forces to do both,” the Middle East Defence Committee had said in a telegram to London on 9th July, “and if we try to do both we may fail to achieve either. We request your guidance and instruction on this issue.”

At one of the conferences at Cairo on the 4th Brooke explained to Churchill, Smuts, Wavell, Casey and the three Commanders-in-Chief that the Chiefs of Staff considered that to defeat Rommel would be the best contribution the Commanders-in-Chief could make to the security of the Middle East, but that, if the Russian southern front broke, they must hold the Abadan oilfields area even at the risk of losing the Egyptian Delta. Churchill said, however, that he was not prepared to divert any forces from Egypt until a decision had been reached in the Western Desert. The meeting agreed to this policy.

Next day Churchill and Brooke visited the Eighth Army. Churchill drove first to the 9th Division’s headquarters, where he arrived at 9 a.m. accompanied by Generals Brooke, Auchinleck and Ramsden and Air Chief Marshal Tedder. There he met the Australian brigadiers, senior staff officers, and heads of services and drove through the areas of the 2/ 3rd

Pioneer Battalion and 26th Brigade, stopping to speak to men on the way. Morshead noted in his diary that the British Prime Minister was most congratulatory and said that the division had stemmed the tide and done magnificently.

The visit to the Eighth Army provided opportunities for both Churchill and Brooke to see something of Gott. Churchill was confirmed in his view that this man with the “clear blue eyes” was the commander he needed. Brooke’s misgivings were confirmed.

By 6th August Churchill had determined that General Auchinleck must be replaced. He first offered the new Middle East Command to Brooke but he declined. Brooke has since stated that he felt he could best serve the Prime Minister as Chief of Staff, but sometimes the reason and motive for a difficult personal choice are not fully evident when one makes the decision.

After further discussions Churchill (on 6th August) sent a telegram to London seeking War Cabinet approval of a reorganisation of the Middle East Command and a series of transfers of senior officers. He proposed a reorganisation of the Middle East Command into two commands – a Near East Command comprising Egypt, Palestine and Syria and a Middle East Command comprising Persia and Iraq. Auchinleck was to be offered the new and relatively inactive Middle East Command and General Alexander2 the Near East Command. Alexander who had previously been appointed to command the British army to take part in the projected Allied landings in French North Africa, should be replaced in that command by General Montgomery. General Gott should command the Eighth Army; and Generals Corbett (C.G.S. at Cairo), Ramsden (XXX Corps) and Dorman-Smith (D.C.G.S.) should be replaced. Churchill added that Smuts, Brooke and Casey approved of these proposals. The War Cabinet agreed, though at first it raised objections to the division of the command. If the Prime Minister’s personal selection of a field commander at the second level of command in an operational theatre was unorthodox, Brooke’s endorsement gave it at least formal correctness. On the 7th, however, an aircraft in which Gott was travelling to Cairo was shot down. Gott was killed. Thereupon Churchill proposed that Montgomery should command the Eighth Army and the War Cabinet agreed.3

“Strafer” Gott was widely mourned in the Eighth Army by the commanders, staff officers and men who had come to know him in the course of the army’s battles but were as yet unaware to what purpose he had been summoned to Cairo. Many of these later contended that, when the mantle was placed on Montgomery’s shoulders, it was merely to execute a plan that Gott had made. Yet, in the after-knowledge afforded by historical research, Gott’s potent influence on both the decisions of the army command and their execution in the campaigns that preceded his death appears

to have contributed as much to the army’s defeats as to its victories. His virtues were his character, impressive bearing and ability to inspire others with confidence in himself, rather than the capacity, possessed by Montgomery in abundant measure, to conceive the form of successful battle action and to get commanders, staff and combatants to work efficiently, train and fight to the conception.

In the preceding year Churchill had been impatiently critical of Auchinleck because of his refusal to be hastened in mounting the offensive intended to relieve Tobruk and destroy the German Army in Africa. Now, despite Auchinleck’s recent success in halting Rommel by seizing the initiative and forcing him onto the defensive, Churchill was again impatient because Auchinleck was proposing not to mount another offensive before mid-September. That would seem to have been the main factor prompting Churchill’s decision to remove him from command. Yet the successors Churchill chose soon came to the same conclusion as Auchinleck, and eventually decided that the offensive should not be resumed until much later than Auchinleck had suggested.

After the new appointments had been announced, among those of Auchinleck’s subordinates who wrote to him expressing regret and gratitude was Morshead, who said:–

I am very sorry and very surprised that you are going away, and every single member of the AIF will be as regretful as I am, for we all hold you in the highest regard.

You have always been particularly kind and generous to me, and I shall always remember with gratitude your consideration and encouragement both while in Tobruk and ever since, and your having me to stay with you on several occasions.

I hope that your new appointment will be worthy of you. Whatever and wherever it is I should be not merely content but very privileged to serve under you.

“I looks towards you” Sir, and wish you all you wish yourself.

Auchinleck understandably declined the proposed “Middle East” appointment on the ground that he considered the new command arrangement faulty in structure and likely to break down under stress. He went to India, took some leave and then set about writing his despatch.

It had long been evident that Alexander, seven years younger than his predecessor and indeed four years younger than Montgomery, was destined for high command. Alexander, unlike most of his seniors, collaterals and his immediate subordinate, had held no staff appointment until he was 39; his service in the first world war was almost entirely in the infantry; he was commanding a battalion in France at the age of 25. Brooke, Wavell, Wilson, Montgomery, for example, had seen only brief regimental service or none at all in that war. In the 1930’s Alexander had led a brigade in operations on the North-West Frontier of India, and in France in 1939 and 1940 had commanded the 1st Division (Montgomery commanded the 3rd) and finally the rearguard at Dunkirk. Writing long afterwards about critical days in France in May 1940 Brooke, then a corps commander in the BEF, wrote:–

It was intensely interesting watching him [Alexander] and Monty during those trying days, both of them completely imperturbable and efficiency itself, and yet

two totally different characters. Monty with his quick brain for appreciating military situations was well aware of the very critical situation that he was in, and the very dangers and difficulties ... acted as a stimulus ...; they thrilled him and put the sharpest of edges on his military ability. Alex, on the other hand, gave me the impression of never fully realising all the very unpleasant potentialities of our predicament. He remained entirely unaffected by it, completely composed and appeared never to have the slightest doubt that all would come right in the end.4

After Dunkirk Alexander had been a corps commander in Britain in 1940–41 and then was given the vital Southern Command. When the defence of Burma was collapsing in March 1942 he was hurried out to take over and he commanded during the retreat to India. Montgomery had become a corps commander in England in 1940 and late in 1941 had been promoted to South-Eastern Command.

Alexander arrived in Cairo on 8th August and, after he assumed command on the 15th, chose General McCreery as his chief of staff. McCreery, a cavalry officer, had been Alexander’s G.S.0.1 when he commanded the 1st Division in France in 1939 and early 1940, and when the Germans attacked in May 1940 he was commanding the 2nd Armoured Brigade. General Lumsden had been appointed to command the XIII Corps in Gott’s place.

On the 10th Churchill had handed Alexander a handwritten directive:

1. Your prime and main duty will be to take or destroy at the earliest opportunity the German-Italian Army commanded by Field Marshal Rommel together with all its supplies and establishments in Egypt and Libya.

2. You will discharge or cause to be discharged such other duties as pertain to your Command without prejudice to the task described in paragraph 1 which must be considered paramount in His Majesty’s interests.

Alexander implied in his despatch written later that he found the Eighth Army disheartened and discouraged and lacking in confidence in the high command. His first step in restoring morale was “to lay down the firm principle, to be made known to all ranks, that no further withdrawal was contemplated and that we would fight the coming battle on the ground on which we stood”.

Montgomery arrived in Cairo on 12th August. After seeing Auchinleck and Alexander that day he went next morning at Auchinleck’s suggestion to the Eighth Army to spend the two days before Alexander and he were due to take over their appointments. The senior staff officer of Eighth Army, Brigadier de Guingand, was well known to Montgomery, and they had worked together before the war. Montgomery summoned de Guingand to meet him in the desert outside Alexandria, and together they drove out to the headquarters of the Eighth Army. On the way, at Montgomery’s request, de Guingand described the situation and outlined some matters that he thought needed Montgomery’s attention. Among these were:–

(a) The dangerous “looking over the shoulder” defensive policy.

(b) The unsound fashion that prevailed of fighting in battle groups or “Jock Columns” as they were called, and not in divisions as the army had been trained to fight. Only in this way could the army develop its full strength.

(c) The unsatisfactory headquarters set-up.

(d) The fact that Army and Air Headquarters were not together.5

Montgomery had the staff assembled on the night of his arrival and addressed them. In de Guingand’s words, “the effect of the address was electric – it was terrific! And we all went to bed that night with a new hope in our hearts, and a great confidence in the future of our army”.6

Montgomery said that Alexander and he had been given a mandate to destroy the Axis forces in North Africa. Any further withdrawal was out of the question. He would not be very happy if Rommel’s expected attack came within the next two weeks; after that he would welcome it. He would immediately start planning a great offensive. The expression “battle groups” would cease to exist; divisions were to fight as divisions. He would form a reserve “corps d’élite” consisting of two armoured divisions and the New Zealand division (motorised). He would not attack until he was ready, whatever the pressure and from whatever quarter.

When Montgomery arrived Ramsden was temporarily in command of the Eighth Army and both corps were temporarily commanded by Dominion generals – the XXX by Morshead and the XIII by Freyberg. Montgomery, although not due to take over until the 15th, sent Ramsden back to his corps and then wrote a signal to Middle East Headquarters stating that he had assumed command of the army.

–:–

“I will give you two simple rules which every general should observe”. It is some three years before Montgomery came to the Middle East, Wavell is speaking, and his subject is “The General and his Troops”. He proceeds to state his two rules. “First, never to try to do his own staff work; and, secondly, never to let his staff get between him and his troops.”

From the very moment of his arrival at the Eighth Army Montgomery carried both rules to their extreme application. He declined to exercise command through a clutter of paper-work. When de Guingand set out to meet Montgomery that first day, he took with him a paper laboriously prepared to present his views on what was wrong. Montgomery told him to put the paper away. “Tell me about it!” he enjoined. We see him next morning bundling off the unfortunate staff officer who came to him with the morning’s situation and patrol reports.

Far from letting his staff get between him and his men, Montgomery set out assiduously to attract their attention, to show himself often to them and to make himself easily recognisable, not only as a commander but as a man of individuality; to implant in their minds an image of himself as an energetic, realistic and efficient commander. Morale was the number one factor in war, Montgomery always declared. Experts in logistics might disagree, but it was an expedient and efficacious belief for one who could influence his men to fight but had no power to energise the production and delivery of the material means. So Montgomery’s efforts were directed to giving his officers and men a belief in the army they belonged to, a quite unqualified confidence. That, he knew, only success could give them;

but a spirit of optimism could be nurtured meanwhile, and would grow. The first step was to make them believe that they would win their battles. He himself exuded confidence, for he had no doubt that he was an absolutely first-rate commander, and he was determined that there were to be no failures.

Having arrogated to himself two days of command not rightly his, Montgomery went out, saw the ground, and then set off to see and talk with Freyberg and other commanders. On the 14th he visited the 9th Australian Division, met the senior officers, went forward to the 20th Brigade, viewed no-man’s land and the enemy’s front line from Point 24, and then visited the 24th Brigade headquarters for 10 minutes. He called for and was issued with a “digger” hat, which he wore for some time before deciding to adopt a beret as his distinctive head-dress. Montgomery then asked for and was given a “Rising Sun” badge for the hat, claiming an entitlement to wear it on the ground that his father had been Bishop of Tasmania.

The hat was brought to him while he was at Brigadier Windeyer’s headquarters on the occasion of that first visit. Montgomery tried it on without denting it, looking rather odd. While Montgomery was talking to others present about hats, Morshead took Windeyer aside, suspecting that the new army commander’s idiosyncrasies might strike Windeyer as rather comic, if not surprising, and told him: “This man is really a breath of fresh air. Things are going to be different soon.” A few days later Morshead summoned the brigadiers to meet him at Windeyer’s headquarters. Windeyer recalled the conference many years later:–

I am quoting Morshead’s words as nearly as I can remember them:

“I have had a long talk with the new army commander. It was refreshing. He is making some changes. There are some things, four things especially, he wants understood.

First, this line will be held. There will be no further withdrawals and plans for withdrawals are cancelled. We will hold our present position until he is ready to attack. That is good news.

Second, formations are not to be broken up. There will be no more battle groups or ‘Jock columns’. Divisions will fight as divisions and brigades as brigades. That I am sure we are pleased to hear.

Third, the word ‘box’ is not to be used; it is banished from the military vocabulary. He doesn’t want to create the impression that the army is boxed up. That you will understand too.

His fourth point is perhaps not quite so easy: he says that the word ‘consolidation’ is also to be banished. It is a handicap to the momentum of an attack. When his attack begins he does not want it to seem that he intends it to come to a standstill. He intends to keep going. He suggests ‘re-organise’ is a better word than consolidate.”

A point Morshead may not have mentioned to his brigadiers, because it did not concern them, was that Montgomery had also told his senior commanders that he was a firm believer in the chief of staff system and would always act through the chief of his staff. This contrasted with the methods adopted by his predecessor, whose employment of the clever Dorman-Smith in the role of Deputy Chief of the General Staff in the field, and as a close collaborator in directing operations, had introduced, whatever benefit came from it, a questionable dualism of staff function.

Montgomery further made it clear to his commanders that orders were to be acted upon, not debated.

On another visit to the division made soon afterwards Montgomery, seeing some gunners beside one of the new anti-tank guns, asked them what they thought of the gun and was told that they had not fired it; they had been forbidden, they said, to practise with live ammunition because it was so scarce and reserved exclusively for battle use. Within a day or two an order came down from Army Headquarters that every six-pounder gun was to fire off half its ammunition stocks in practice. “Unless the men are trained to shoot,” said Montgomery’s memorandum, “we shall do no good on the day of battle however great the number of rounds we have saved ready for that day.”

When the commander of the 51st Highland Division, General Wimberley,7 informed General Montgomery soon after the division’s arrival that he was troubled at having been told that flashes were not to be worn in his division because Middle East security rules forbade formation and unit identifications on dress, Montgomery at once told Wimberley to let his men wear their flashes.

Other instances could be found, but those given must suffice to illustrate the methods by which Montgomery almost instantly had an extraordinary effect on the Eighth Army, giving it revived hope, a better tone and a new confidence. With an orator’s instinct – not with rhetoric but with telling words followed up by action that showed he meant what he said – he told his army the things it wanted to hear, that it would never go back but fight where it stood, that it would surely attack again when ready, but not before, and that tactical methods which had failed – the “boxes” and the small improvised battle groups – would be discarded and the vocabulary signifying them banished. His influence was felt first and most dynamically at the higher command level but percolated down to the front-line soldier as the thoroughness of the army’s preparations and the purposefulness of the training and rehearsal soon required of all formations and units came to be experienced. No army was ever more confident, none ever had a higher morale, than the Eighth Army when it next attacked.

Montgomery soon took the wise step of concentrating his whole headquarters at Burg el Arab close to Air Vice-Marshal Coningham’s8 Desert Air Force headquarters. Alexander then set up a small tactical headquarters of his own, also alongside.

In order to strengthen the army against Rommel’s expected attack Montgomery asked for and was promptly given the recently-arrived 44th Division because he wished to place it on Alam el Halfa Ridge which could become the keystone of resistance to a wide turning movement

when the next enemy blow fell. He then got Alexander to agree to have General Horrocks9 flown from England to command the XIII Corps; later Lumsden was transferred to the command of the X Corps.

–:–

Churchill visited Egypt again on the 19th on his way home from Russia. “A complete change of atmosphere has taken place ...” he reported. “The highest alacrity and activity prevails”; and he found that Alexander “cool, gay, comprehending all ... inspired quiet, deep confidence in every quarter.”10

In due course news of the appointments to high commands in the Middle East made after Mr Churchill’s first visit reached Australia. When General Blamey learnt of the first round of changes, including the promotion of Major-General Lumsden to a corps command, he drew Mr Curtin’s attention to the appointments, in a letter dated 21st August 1942, asserting, but without derogating from the officers concerned, that none of them had had “the same experience of desert warfare or the same success in any warfare” as General Morshead, who, he said, could not but feel humiliated at having inexperienced English officers in command over him.11 The disregard invariably shown by British authorities in the Middle East in this respect, said General Blamey, was notorious, and this latest example had aroused ill-feeling in the Australian Army. He asked the Prime Minister to make representations to London that the claims of Dominion commanders for higher command should not be disregarded. He also cabled Morshead assuring him of his fullest confidence and informing him that he was referring this question of higher command appointments to the Prime Minister.

Morshead replied that it had been made abundantly clear that Dominion commanders were ineligible for corps commands even when the corps consisted wholly of Dominion troops; soon after Major-General Ramsden had been appointed to the command of XXX Corps, then consisting of the 1st South African and 9th Australian Divisions, he had informed Morshead that Major-General Briggs,12 who had only recently been appointed to command an Indian division in another corps, would take over the XXX Corps if Ramsden became a casualty.13 Morshead also

mentioned that when Gott was killed Freyberg had administered the XIII Corps for a few days, but then Horrocks, who had commanded a machine-gun battalion in France but had had no operational experience since, had been appointed to that command.14 Morshead added that he was too interested and occupied with his own command to bother about personal feelings.

Blamey wrote a second letter to Curtin, telling him of the additional facts mentioned by Morshead and again suggesting that he raise the matter with the authorities in the United Kingdom. No Australian commander, he said, had any desire to be appointed to the command of troops of the United Kingdom except when they were fighting in the same formations as Dominion troops; but where that was so, failure to recognise the claims of proved Dominion commanders placed a severe strain on good relations between senior officers. Curtin then cabled Churchill expressing the Australian Government’s concern that Morshead’s claims for consideration appeared to have been disregarded. Churchill replied that Morshead had been carefully considered when the recent appointments were made and his undoubted qualifications would be taken into account in any further change. He added that the Chief of the Imperial General Staff had instructed Montgomery to consider the desirability of giving Morshead a corps; this, said Churchill, would have been agreeable to himself, for he had formed a high opinion of Morshead’s bearing and spirit when he had visited his headquarters at El Alamein.

Meanwhile Morshead had informed Alexander (on 5th September) of his exchange of cables with Blamey and of Curtin’s cable to Churchill. A few days later, in a cable to Blamey, he reported Alexander’s reaction:–

He replied highest commands in Middle East were open to Dominion commanders and that appointments of corps commanders in August were made at a conference of Prime Minister, Commander-in-Chief and General Montgomery in Cairo. He was good enough to say he thought I had some qualifications for corps command, adding that war would last long time and opportunity would come.

On 13th September, three days after Churchill had cabled Curtin that Morshead’s qualifications would be considered in any further change, Montgomery informed Morshead that Lieut-General Ramsden was being replaced as commander of the XXX Corps by Lieut-General Leese,15 who was due to arrive by air from the United Kingdom that day. In a cable sent next day informing Blamey of this, Morshead said that he had asked Montgomery whether he was aware of Morshead’s earlier conversation with Alexander. Montgomery had acknowledged that he was. Morshead reported Montgomery as saying that both the Commander-in-Chief and he

were of opinion that as Morshead was not a regular soldier he did not possess the requisite training and experience.16 He continued:–

When asked whether 9th Australian Division had ever failed to do what was required of it he replied it was superb. Admitted he did not know me or anything about my service and said if Leese became casualty during operations I would then command corps. Montgomery who has revitalised Eighth Army is quite friendly but just doubts capacity any general who has not devoted entire life to soldiering.17

Morshead stated that he had told Montgomery that he was presenting the case of Dominion officers generally rather than pressing any personal claims. He told Blamey that he was very content and happy with his present command and appointment.

Blamey (who had been a regular from 1906 to 1925) wrote to Curtin that Morshead’s account of his interviews revealed an “attitude of unconscious arrogance” and “the repugnance of the British Command to accept Dominion officers, however successful in higher command” because “they had not been turned out on the British pattern”. If these were strong words, yet the facts seemed to support Blamey’s contention. An unexpressed reason for not preferring Morshead may have been that Auchinleck and Ramsden had found him a difficult subordinate. The considerations mentioned by Blamey did not apply to the case of Freyberg who, though he showed no ambition to leave the New Zealand division for higher responsibilities, could have been considered for a corps command but was not, for a long time to come. Freyberg was an ex-regular officer and Guardsman with an unsurpassed record of both gallantry and operational command; his seniority as a regular major-general had been above that of Alexander, Montgomery, Wilson and Auchinleck and only nine months below Wavell’s.18 Yet at the close of the African campaign, Freyberg was still only a divisional commander, although he had temporarily commanded a corps for a fortnight just before the surrender of the Axis forces; indeed it was not until February 1944, after Freyberg’s division, in three years of fighting under his command, had successfully carried out more major operational tasks than any other Allied formation, that he was made a corps commander, after representations had been made by the New Zealand Government to the British Government against his repeated supersession by British commanders of less experience.

There was nothing dishonourable in all this. It was merely that the men at the top of the British Army hierarchy tacitly assumed that they would direct the operations of all the formations committed to a theatre in which they exercised command, regarding the role of Dominion commanders as merely one of commanding their own formations; nor would the point have occurred to them, until it was brought to their attention, that a corps such as XXX Corps, holding its front with two Dominion divisions, might as appropriately be commanded by a Dominion commander.

There can be little doubt that a main factor determining the selection of the officers chosen for key posts in the Middle East at this time was the opinion of the Chief of the Imperial Staff, General Brooke. They had all served under him Alexander, Montgomery, McCreery and Horrocks in France, Leese in England.19 That Brooke chose well is unquestionable.

While the appointments to higher command were under discussion, Morshead was considering who should command the 9th Division in the event of his becoming a casualty. He felt that, of the officers available, Brigadier Ramsay would be the best choice. Since Tovell was senior to Ramsay, he recommended in a cable to Blamey on 31st August that Tovell should be recalled to Australia for higher appointment. He told Blamey that Tovell’s brigade had done splendidly in recent operations and that Tovell had always given full and loyal support. Blamey replied that Tovell should be returned to Australia, but owing to the claims of others could not receive a higher appointment. He also said that he intended to send a major-general to be Morshead’s second-in-command. Morshead demurred to the latter suggestion. He did not, he said, see the need for a deputy. He had every confidence that Ramsay would command the division efficiently if the need arose. Should Blamey still decide to send a deputy, he asked to be first consulted about the person to be appointed, for it was essential that he and Morshead should work well together. Blamey did not reply immediately. In the meantime, on 12th September, Tovell had handed over his command to Brigadier Whitehead, whom Morshead had promoted to be his successor. Blamey reverted to the question of a deputy when cabling Morshead with reference to Leese’s appointment to the command of XXX Corps. He said that the suggestion had been made partly as a camouflage “of possible developments at some future date” – an oblique reference, presumably, to the possibility of the division’s recall to Australia. He had intended sending Major-General J. E. S. Stevens (then commanding Northern Territory Force), but, on receiving Morshead’s views, had withheld action. If Morshead now agreed with him, he would be glad of a panel of names of officers whom Morshead would prefer for the appointment. He doubted if Ramsay was sufficiently experienced for the responsibility involved. Morshead replied that he would now be glad to have Stevens as his deputy.

Curtin’s and Blamey’s protests and Morshead’s representations appear to have eventually had some effect. Morshead’s diary records that Alexander’s Chief of Staff, McCreery, called on him on 4th October and had

a general discussion. Next day Montgomery visited Morshead and, in the course of a long discussion about the forthcoming battle, informed him that he would command the XXX Corps if Leese became a casualty.

–:–

The period over which the first of these changes in command had been taking place was one of static defence while the Eighth Army was getting ready to counter the onslaught Rommel was expected to make in mid-August. For the forward infantry and the engineers, who were laying mines, digging and patrolling, it was not a restful time. By night they slept in broken watches, each taking his turn to keep guard or patrol the wire; in addition one full night’s sleep in three might be lost by men employed on deep patrolling. By day the heat, the intermittent shelling and the ubiquitous flies drove sleep away. The flies! The divisional cavalry recorded on the 9th that they were so bad that the midday meal had been practically dispensed with. It was midsummer A number of unburied dead still lay on the battlefield when the 20th Brigade took over the forward positions. A strenuous policy of burying and cleaning up was adopted and within a fortnight the fly menace was under control.

The 20th Australian Brigade had two battalions forward: the 2/15th (Lieut-Colonel Ogle) on the right and the 2/17th (Lieut-Colonel Simpson20) on the left, with the 2/13th (Lieut-Colonel Turner) in reserve. On 3rd August, the day on which the brigade took over the front, Brigadier Windeyer laid down a policy of aggression. The enemy, he ordered, was to be fired on whenever seen, and harassed by patrols and raids. The first patrol in compliance with this direction set out from the 2/15th at 9 p.m. on the 4th. It comprised Captain Cobb21 and 12 others. When they reached their objective about 1,500 yards north of Point 25 (Baillieu’s Bluff) they were challenged and found themselves in the midst of a German position.

By this time (wrote Cobb in his report) everyone knew that surprise had been lost. All talking and digging had ceased and they were waiting for us. I placed the two Brens and then told the others we were going to crawl forward to the ones we had seen go to ground. No questions were asked. We crawled for about 60 yards, Corporal Else22 and three men on my right, Corporal Cooper23 and three men on my left, when we heard the bolt of a Spandau ripped back about 15 yards in front. I pitched my 69 at him and he fired at the same time. One bullet got me through the leg, one got Munckton24 through the foot and one got Cooper, who was the slowest to get to his feet, in the body.

Private Munckton and I then followed the others into where the Spandau just fired from. The gun was not firing but there was movement in the fairly large trench behind it. Munckton emptied his rifle into it and at the same time Corporal Else yelled out “I’ve got a prisoner and all my men are safe.” McHenry25 yelled out

“Corporal Cooper dead, Munckton hit and has left for home.” Lance-Corporal Morris26 who was Cooper’s fourth man was having a merry time with his Tommy-gun on the left flank in another doover. I ordered the patrol to withdraw and moved over to where Corporal Else and party were. Just then the prisoner had a bit of a scuffle and threw himself to the ground – shamming dead. Private Woods27 reminded him that he was alive with his bayonet and he jumped up and moved off with us. We had gone about 10 paces when someone fired from the ground at us with a Tommy-gun. I got him twice with my pistol from about ten feet but not before he had put one into my arm and killed our prisoner. After we’d gone through the prisoner I began to realise that the bullet through the arm was going to be a different matter than that in the leg. I told Else to take the patrol back and got Private Pickup28 to give me a hand along. Just as we reached the Bren gunners I blacked out and Corporal Else threw me over his shoulder, got his men together – or rather apart – and moved off. From then on for about 1,000 yards they took it in turns to carry me until some particularly close medium machine-gun fire forced us to ground. I found when I got to my feet I was feeling much better and was able to walk most of the way into the road. At the road fortunately we found an Iti stretcher and I rode home in state on that.

Every man on the patrol knew, when the surprise was lost, that we were in for it – but no one hesitated or asked any questions. Corporal Else did an outstanding job. He carried out his orders to the letter in obtaining a prisoner and controlling his men. He remarked when I told him that I could stumble along behind that he’d carry me home even if I were b––– well dead. He frequently changed direction going home to keep the patrol out of the heaviest MMG fire and kept the men alert and moving. ...

For the second night in succession Private McHenry did an excellent job. His sense of direction is always reliable. He moves like a cat. Can see and hear men moving and talking in about ten different places at the same time.

An intensive program of supporting fire from machine-guns, artillery and mortars had been prearranged to begin at the moment when surprise was lost and this had the desired effect of simulating an attack on a broad front, thus confusing the enemy and causing the laying-down of his defensive fire plan. Thus enemy shells and machine-gun fire passed harmlessly over the heads of the withdrawing patrol to fall on the distant targets of Point 25 and Trig 33. Cobb decided that there was a continuous line of enemy defence works from the coast to Point 25. The prisoner was from the 125th Regiment (part of the 164th Division) newly arrived from Crete.

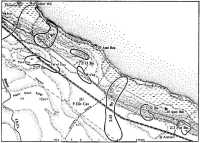

Until the 7th the enemy appeared to be unaware of the 9th Division’s withdrawal from the El Makh Khad positions. That day, however, enemy aircraft made a reconnaissance of the area and Morshead decided that outpost positions should be occupied there to prevent close enemy observation of the El Alamein and Tel el Eisa defences. At 11 p.m. on the 7th a company of the 2/13th, which had been maintaining a series of posts south of the railway and north of Makh Khad linking with the Alamein Box defences, occupied Trig 22, around which a protective minefield belt was at once laid by the 2/13th Field Company. A patrol, 1,800 yards farther forward, drew flares and long-range fire. The same night the 2/43rd placed a company with anti-tank guns and machine-guns astride

Dispositions, noon 7th August

the Qattara Track east-south-east of Trig 22. On the next night the 2/43rd took over from the company of the 2/13th at 22 and occupied the Makh Khad Ridge from about Cairn to a position astride the road round Kilo 6. Patrols went forward 2,000 yards that night but saw no movement and next night patrols with sappers attached went 3,000 yards – half way to Ruin Ridge – still without finding minefields or seeing the enemy.

On the night of the 10th–11th the 2/15th sent out a patrol to probe west of Point 17 for some 2,600 yards ahead of the forward companies to a locality which earlier patrols had established to be the usual route taken by German working parties. Captain Angus29 led the patrol which was 17 strong. After 2,400 yards an enemy working party of about 40 men was seen moving north about 75 yards away. Other parties were observed moving about but were too far away to be attacked advantageously. After the patrol had waited patiently for some 30 minutes, a party of 25 Germans approached. When they were only three or four yards away Angus threw a grenade as the signal for every man to open fire; the patrol had two Brens, four sub-machine-guns and six rifles. Every German was killed or wounded and one of the wounded (from the 125th Regiment) was carried back; one Australian was wounded and another was missing. Here again a previously planned heavy fire support plan was used to confuse the enemy and cause him to lay down his defensive

fire and the patrol returned unmolested by the enemy fire, which passed well overhead.

While the 2/15th Battalion’s patrols were aggressively fighting the enemy behind his own lines between the railway and the coast, the 2/17th was patrolling along the railway line and to the south of it, where the enemy defences were more distant from the Australian lines. The 2/13th Battalion was also pushing out patrols through the 2/17th Battalion front in a south-westerly direction.

A patrol of the 2/17th led by Lieutenant Norton,30 a particularly accurate and reliable officer, which was out from 9 p.m. on the 13th August to 3.30 a.m. next morning, made the deepest penetration so far effected in their sector-5,500 yards. At 4,090 yards the patrol was fired on by a Spandau but its bullets flew high. In the next 800 yards trip wires were encountered and at 5,478 yards a breast-high wire on long pickets, which gave a warning rattle when struck by the patrol’s scout. A sentry challenged. The patrol went to ground for a few minutes, moved forward again, was again challenged, then charged, and was met by fire from men in trenches, to which the patrol replied with grenades, sub-machine-guns and rifles. After an exchange of fire lasting two minutes Norton withdrew his men without having a single casualty.

Next night the 2/17th sent out two patrols, one to follow up Norton’s, the other to probe a locality on the south side of the railway line where the enemy had been reported (by a group of officers investigating from no-man’s land without authority) to be developing a defensive position. The latter patrol, which was the deepest, was led by Lieutenant Thompson31 and its task was to move 6,000 yards parallel to the railway line, then southwest for 1,400 yards and thence back to the start-point. After about 4,000 yards the patrol, 12 strong, passed through two fences into a “most extensive” but unoccupied position with a pill-box and trenches. Just then about 50 enemy troops approached unawares. The patrol opened fire at 20 yards range, inflicted some casualties and then withdrew north to the railway line. Thompson was hit by grenade splinters but no other Australian was harmed. Thompson having been stunned, Corporal Monaghan32 coolly and skilfully extricated the patrol. The patrol was important as confirming the existence of a strongly-held locality about 500 yards south of the railway and 5,500 yards from Tel el Eisa station. This was now named Thompson’s Post, a designation that was not apt to describe a defended area of considerable extent.

The other patrol again probed the general area covered by Norton’s patrol and discovered that the enemy had closed a gap in his wire and was working hard with compressors, picks and shovels. These patrols showed what the enemy was doing to command the coast road from the south.

A patrol of the 2/13th Battalion which probed forward of the 2/17th’s positions on the night of the 14th–15th comprised Lieutenant Edmunds,33 a reinforcement officer leading his first patrol, and seven others. Edmunds pointed out to his men a constellation on which any man who became separated was to march. The patrol moved out stealthily for 2,800 yards and went to ground near an enemy working party. Edmunds went forward and returned with the information that there were enemy-occupied positions on either side. After a wait Edmunds moved the patrol towards one working party. An enemy sentry stood up and challenged. Edmunds gave the order to charge and hurled himself at the sentry but was shot. Corporal Humphries34 took command but was killed while leading the men out. The men scattered but the survivors, except one man who became a prisoner, made their way back separately, guided by the constellation Edmunds had with forethought pointed out.

The divisional cavalry was patrolling by day, and on the 15th it was decided that members of patrolling companies of the 2/13th should go out with the cavalry to study the country west and north of East Point 23 in daylight.

Information from a prisoner suggested that Italians occupied a dominant feature, which faced Trig 33 across the saltmarsh, named Cloverleaf (from the shape of its contours on the map) and Germans the feature on the coast to the north-east, later named Suthers’ Hill. Major Suthers’35 company was given the task of raiding the hill. If the opposition was not too strong, he was to leave one platoon there and raid Cloverleaf with the other two. The company set out but about 400 yards from Suthers’ Hill Lieutenant Newton’s36 platoon walked into a field of booby-traps and Newton and 10 men were hit. A flare was fired from Cloverleaf and voices were heard from Suthers’ Hill but no shots were fired. Unable to find a way round the field of booby-traps the company withdrew.

A patrol of 19 under Lieutenant Adnams37 of the 2/43rd and including Captain Bakewell38 of the 2/3rd Pioneers set out from between Cairn and Trig 22 in a south-westerly direction at 11.15 p.m. on the 16th under orders to penetrate some 4,000 yards. After 2,600 yards had been covered a working party could be heard and 800 yards farther on minefields were encountered. German voices were audible. Four Bren gunners were left here and the patrol went on, reached diggings occupied by at least 50 men, threw grenades, grabbed three men (Italians) and shot or bayoneted at least 12 more. Soon after they had begun to move back, they came under fire from a mortar and at least eight machine-guns firing on fixed lines. It took the patrol about an hour to get clear, and Bakewell and the four

Bren gunners were then missing. Captain Hare led a party out to find the missing men. It was discovered that Bakewell had been wounded by a booby-trap. The Bren gunners carried him for 200 yards but then left him at his own request, and because his wounds were so serious. All the other missing men were found or made their own ways back, three of them having been wounded.

Australian patrols established bit by bit that German sub-units were bolstering Italian units. Night patrols heard both languages being spoken in adjacent places, and German and Italian weapons were fired from positions close together. The Australian battalions maintained their mastery of no-man’s land but the enemy reacted by closely wiring and booby-trapping all forward positions within the range of normal patrolling so that it became difficult to effect deep penetrations unless a large and carefully planned raid was made.39

On 22nd August the enemy’s “political warfare” experts raised the 9th Division’s spirits by arranging for aircraft to scatter leaflets over the divisional area. They measured 6 by 8 inches and were headed with the divisional insignia – a platypus over a boomerang. One set read: “Aussies! The Yankees are having a jolly good time in your country. And you?” The other read: “Diggers! You are defending Alamein Box. What about Port Darwin?” The leaflets were treasure trove indeed and eagerly collected for sale to others as mementos or to post home.

–:–

On 19th August Alexander confirmed his spoken instructions to Montgomery with the following written directive:–

1. Your prime and immediate task is to prepare for offensive action against the German-Italian forces with a view to destroying them at the earliest possible moment.

2. Whilst preparing this attack you must hold your present positions and on no account allow the enemy to penetrate east of them.

Alexander ordered that this decision be made known to all troops.

By the 20th Montgomery had been in command for eight days and his new policies were having their effect in the forward units. An operation order by Morshead on 17th August announced that the division would defend its present forward defended localities at all costs and that this was to be impressed on all ranks immediately. Next day a divisional staff instruction stated that in the Eighth Army the word “box” was not to be used to describe a defended area, and the term “battle group” was not to be used. On the 19th Godfrey informed his colonels that, in accordance with the army commander’s policy, the 2/43rd’s positions would cease to be “outposts” and become “forward defended localities”.

On the 22nd extracts from a memorandum from Montgomery were sent to all commanding officers. One extract expressed alarm at the prevalent idea that units and sub-units could not be assembled in compact bodies

to be addressed by their commanding officers or sub-unit commanders; apparently it was feared that the enemy might see such an assembly and shell it or attack it from the air. “I consider,” wrote Montgomery, “that if a unit is to be welded into a fighting machine that will fight with tenacity in battle, then it must be assembled regularly and the men addressed personally by their officers.” He also said that he favoured performances by concert parties in the areas of the forward divisions and added that he wished weapon training to be carried out in forward areas with live ammunition.

Many equipment shortages were being remedied, though requisitions for wire to protect the forward infantry positions, most of which were not wired, continued to remain unfulfilled. The divisional diary recorded on the 19th that more Crusader tanks were expected for the cavalry regiment to bring it to its full establishment of 28 tanks; battalions were to have four Vickers guns and eight 2-pounder anti-tank guns.40 Since early in August the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment had had 64 6-pounders; its 2-pounders were being handed over to the infantry.

Officers and men who had served in the first world war or the militia welcomed the restoration of a medium machine-gun platoon to battalion war establishments, recalling that there were two such platoons in the support companies of Australian battalions until the formation of the first AIF division, when a more recent British establishment was adopted. Then Vickers guns were grouped in machine-gun battalions, which became corps troops, on the scale of one such battalion per division in the corps. This reorganisation may have been prompted by first world war experience, but AIF experience in the 1939–45 war evidenced no need to place medium machine-guns under corps control.

–:–

In a sense the defeat of the Axis forces in Africa was a victory of the sea war. Both armies’ supplies came mostly by sea. The fortunes of the British army commanders depended more on what they received and what their enemy was prevented from receiving than on their own manoeuvres. They never for long had the better of their adversary on the field of battle except when they were blessed with a preponderance of armaments and resources. Some of Rommel’s greatest victories, even so, were won when he was outmatched in all but skill.

There were three courses open to Rommel after Auchinleck’s spirited counter-attack in July had failed by never so fine a margin to snap the strained Axis line. He could disengage to entice the British from their fixed defences, and revert to a battle of movement in which his formations excelled; he could try once more to envelop his enemy’s forces in the

El Alamein positions if only he could build up the requisite strength; or he could settle down to hold fast to the El Alamein line by defence in depth, a course that could offer no prosperous final outcome.

Mellenthin has recorded that disengagement, together with a withdrawal of all the non-mobile formations to Libya, was considered early in August by the general staff of the Armoured Army of Africa but there were reasons other than tactical for not adopting that course.

The British excelled at static warfare, while in mobile operations Rommel had proved himself master of the field. So long as we did not remain tied to a particular locality we could hope to hold up a British invasion of Cyrenaica for a long time. But Hitler would never have accepted a solution which involved giving up ground, and so the only alternative was to try and go forward to the Nile, while we still had the strength to make the attempt.41

The “only alternative” required an improvement in the dispatch of men, equipment and supplies and their safe delivery to Rommel’s army. In July and August deliveries were stepped up. The Germans were using 500 transport aircraft to bring across men and supplies. In April, May and June 22,900 men were flown in for the army, 6,600 for the air force; in July and August 24,600 for the army, 11,600 for the air force. In addition to the 164th Division, the Ramcke Parachute Brigade was brought across from Greece. As replacements for the Pavia and Sabratha Divisions, rendered ineffective in the July fighting, two new Italian divisions, the Bologna and the Folgore (a parachute formation), were arriving forward. Another fresh division, the Pistoia, had arrived but remained in Libya.

The German army formations were low in numbers when August opened. Only about half the units of the 164th Division had arrived. The 90th Light Division had only 51 per cent of establishment; the two armoured divisions, the 15th and 21st, only 61 and 68 per cent respectively. By 15th August, however, the German war diary recorded that the German formations were then at 75 per cent of full strength, compared with 30 per cent on 21st July.

With respect to supplies brought by sea the picture was gloomy. In July only 6 per cent of such supplies had gone to the bottom, but in August 25 per cent of the general military cargo and 41 per cent of the fuel were lost on the way.42 Further grave difficulties were experienced in delivering to the front such supplies as were landed. On 1st August Rommel made representations to the German High Command concerning these problems and their remedy. He asked for barges and three coasters and recommended continuous air protection of his coastwise shipping. More unloading equipment was required for Tobruk. German staff, for effective regulation of railway traffic, and German locomotives and waggons were needed. The shortage of vehicles should be remedied by deliveries to Tripoli and Benghazi.

The shorter Axis supply route could be utilised to reduce temporarily the disparity in strength between the contending armies but Rommel could

expect the situation again to become worse in September when the supplies sent from America and Britain after Tobruk fell reached Egypt. He must therefore attack in August.

On 7th August Rommel informed the commanders of the Africa Corps, XX Italian Corps and 90th Light Division of plans for a renewed offensive. The 21st and 15th Armoured Divisions were then withdrawn in succession to rearward positions to prepare for the onslaught. On 19th August the German commander told his subordinates that he would probably attack in the moonlit period at the end of the month, and three days later he issued the preliminary orders. Moonlight was needed for the armour to make the initial penetration by night.

The two critical items of supply were tanks and fuel. The Africa Corps had accumulated 203 medium tanks of which more than half were the formidable “Specials”, including Mark IV Specials which outmatched any tank of its opponents. The XX Italian Corps had 281. This was largesse not enjoyed since the first weeks of the Gazala offensive. But fuel was short. On the day Rommel issued the preliminary orders, he reported to General von Rintelen that if the attack was to be made about 6,000 tons must reach Libya between 25th and 30th August. A promise to send 10,000 tons, of which half would be for the army and half for the air force, was received. On the 27th the Africa Corps had only enough fuel to carry its tracked vehicles 100 miles and its wheeled vehicles 150 miles, but on the 30th more stocks arrived, the Luftwaffe gave the army 1,500 tons, and a shipload of 730 tons reached Tobruk. Rommel had enough fuel to launch his offensive, but not enough for further operations. However, the formations to make the assault had already begun to move.

–:–

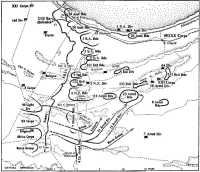

A defensive position in the desert was usually established by resting one flank securely on the sea and holding a front strongly some distance to the south; behind the front a line of defences facing south was usually developed, with gaps filled by armoured formations to threaten the flank and rear of an enveloping force. El Alamein was no exception, since the Qattara Depression was too far from the sea for all the ground between to be strongly held. When the Battle of Alam el Halfa began the front was firmly held from the coast to Alam Nayil with three Dominion and one Indian divisions; south from Alam Nayil, where the New Zealanders’ left flank was refused, the continuation of the line was held with light mobile forces.

Three ridges ran back from the firm front: El Miteiriya, Ruweisat and Alam el Halfa. Like Auchinleck and Dorman-Smith before them, Alexander and Montgomery saw that the key to defence against attack from the south was to base the rearward defence of the southern flank on the southernmost of the three ridges – the Alam el Halfa, behind Alam Nayil.

Auchinleck had lacked sufficient forces to hold a firm front southwards from the sea-shore beyond Tel el Eisa to Alam Nayil while at the same time providing for defence against an enveloping enemy attack launched south of Alam Nayil. Hence had flowed the indecisiveness, which

had angered Morshead, as to whether to hold the shortest possible front, resting the main defence on the Alamein Box, or whether to extend the ground to be firmly held to include the Makh Khad ridges and other territory forward of the box.

Montgomery’s policy of “what we have we hold” had settled that the more extended front would be held but had involved tying down more troops to frontal defence. His inland flank was not strong despite the occupation of the Alam el Halfa Ridge by two brigades of the 44th Division which had been called forward. Particularly was this so at the flank’s hinge at Alam Nayil where, until the evening of the unexpectedly late German attack, the New Zealand division’s southern flank was held by the inexperienced 132nd Brigade. That evening the 5th New Zealand Brigade changed places with the 132nd in a routine brigade relief which was carried out while the German armour, getting ready to strike, was known to be assembling nearby.

–:–

At the end of August the northern sector from the coast to Deir el Shein was held by the 164th German Division and the Trento Division with their regiments interspersed so that an Italian regiment normally was flanked by German ones. From the north the front-line regiments were: 125th German Regiment, 62nd Italian Regiment, 382nd German Regiment (these three faced the 9th Division), part of 361st German Regiment, 61st Italian Regiment, 433rd German Regiment. From Deir el Shein southwards were the Bologna and Brescia Divisions, stiffened by German groups including units of the Ramcke Parachute Brigade, and the Folgore Division. Behind the front line in the southern sector were concentrating (from north to south) the 90th Light Division, Ariete, Littorio, Trieste, 21st and 15th Armoured Divisions, 3rd and 33rd Reconnaissance Units. The German formations totalled about 41,000 officers and men; the Italian about 33,000.

Auchinleck’s appreciation, and Montgomery’s, that a German attack in the south could best be resisted by defending the Alam el Halfa Ridge was to prove correct. Rommel decided to skirt the front as far south as Alam Nayil, which he thought to be too deep and strongly held to be swiftly penetrable, and planned to attack between Alam Nayil and Qaret el Himeimat with the Africa Corps (two armoured divisions) and Reconnaissance Group on the right, the XX Italian Corps (two armoured divisions) in the centre and the 90th Light Division on the left. When these had thrust through the British front they were to wheel northward and advance to the sea. It was an ambitious plan which required the Africa Corps to travel seven miles between 11 p.m. on 30th August and 6 a.m. on the 31st through minefields of unknown extent.

The initial attack would thus fall on the weak 7th Armoured Division (7th Motor Brigade and 4th Light Armoured Brigade). If the Axis forces broke through to the south and swung north, they were bound to clash with one or more of the three armoured brigades of the 10th Armoured Division. They would be faced (from their left) by the 5th New Zealand Brigade, which was settling in on the New Zealand division’s turned-back left flank, then – though with a wide gap between – the 22nd Armoured Brigade, then farther to the right the two infantry brigades of the 44th Division ensconced on the Alam el Halfa Ridge, with the 8th Armoured

Brigade forward of the ridge about Trig 87. If they pushed through the gap behind the New Zealand division, they would come up against the 23rd Armoured Brigade in front of the Ruweisat Ridge. The brunt of the attack would therefore be borne by the XIII Corps which comprised the formations named above. Montgomery, looking ahead to his own offensive, instructed Horrocks that he must not allow his corps and particularly the 7th Armoured Division to get mauled. The Desert Air Force was to attack the enemy’s forward troops day and night, and also to do all it could to prevent the German Air Force from playing an effective part in the battle.

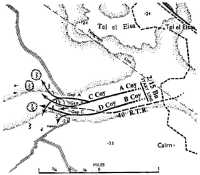

By 23rd August the British staff expected that Rommel would attack in the moonlight period between 25th August and 1st September and it had been decided that, as an immediate counter-stroke, a raid would be made in the north near the coast road towards the enemy’s vulnerable supply routes as soon as his attack was launched. This was to be carried out by the 20th Brigade which was to seize a sector of the enemy’s defences with one battalion and hold it as a firm base from which a small armoured force would raid enemy transport on the main supply tracks leading south from Sidi Abd el Rahman. The operation was to be called BULIMBA.

–:–

At 10.20 a.m. on 30th August sentries of the 2/17th found a British soldier who told a remarkable story and incidentally provided detailed information about the defences west of Point 23 where BULIMBA was to take place. He was Private A. G. Evans of the 1/Sherwood Foresters, who had escaped from Tobruk after its capture and made his way to Salum, thence eastwards, keeping south of the road. He had lived by stealing scraps of food and searching old dugouts. Arabs had helped him. “Nobody took any notice of me,” he said, “although on one occasion I went by mistake into a German camp, but as I had an Italian water-bottle and made a movement with my hands that I had seen Italians make, they did not stop me.” For the past fortnight he had been in the enemy’s area forward of the 2/17th’s positions, either hiding in a dugout or making attempts to get safely through the enemy’s wire, minefields and working parties. Finally he succeeded.

About 11.30 p.m. that night the enemy began shelling and mortaring the 2/13th Battalion’s positions near the sea. Captain Walsoe, whose company occupied a tongue of sand dunes between the seashore and a salt-marsh lying at the foot of Trig 33, reported at 12.30 a.m. that at least a company of the enemy were in the salt-marsh moving towards battalion headquarters and also penetrating the wire of his own defences. Almost simultaneously Lieutenant Appleton,43 whose carrier platoon, holding static positions on Point 5, barred the enemy’s access to battalion headquarters, reported that Germans were trying to get through his lines. Several small enemy groups attempted to work their way forward but were shot up. A fierce small-arms fire fight developed, but after about an hour

the enemy ceased to return the fire. Later the area was shelled. A German prisoner taken in this raid, who belonged to the 111/125th Battalion, said that 80 men had taken part.

Just before 4.30 a.m. a similar raid was launched against Captain Sanderson’s44 company holding the ground to the south of Trig 33. Sanderson called for defensive fire, which the Australian artillery brought down close to the forward positions, but the enemy continued to press the attack for some time and Sanderson’s reserves of ammunition were running low before it was broken off. The Australians later brought in several prisoners.

Another unsuccessful raid was made on the front of the 24th Brigade. At 12.30 a.m. men of Captain Minocks’45 company of the 2/43rd reported that about 80 enemy troops were approaching. The 2/7th Field Regiment shelled them but they passed through the minefield and reached the wire. A close fire fight developed before they were driven off. Then at 4 a.m., Minocks’ men came under fire from six machine-guns. Defensive fire was again brought down and the enemy made off. A patrol at first light found fresh blood on the ground in six places and signs that wounded had been dragged away. One prisoner was taken – a German of the I/382nd Battalion.

These were among several diversionary attacks from the coast to Ruweisat Ridge intended to divert attention from the main thrust farther south, beyond Alam Nayil, where the main enemy force was then moving eastwards.

Rommel hoped to achieve surprise, but since the British expected the attack to be made in the moonlit period the Desert Air Force watched the southward movement of his armour. At dusk on the 30th the forces concentrating for the offensive were attacked from the air. This was only the first of a series of tribulations. When the Africa Corps reached the first minefield about 2 a.m. on the 31st it was in some confusion, again under attack from the air, and under fire from the 7th Armoured Division. Progress was slow; General Nehring was wounded and Colonel Bayerlein took command of the corps until General von Vaerst took over later in the day. The attackers were delayed by bad going, unexpected minefields and renewed air attack, and when Rommel arrived forward at 9 a.m. he postponed the attack, originally planned for 6 a.m., to midday to allow time for re-fuelling, and reduced the distance the corps would have to travel by ordering that it would attack the western part of Alam el Halfa, not the eastern part as planned.

The axis of the German advance was thus switched close to the left of the main concentration of British armour instead of widely by-passing all of it except the isolated 8th Armoured Brigade, which was out in front of the ridge opposite the centre of the 44th Division. Despite the postponement of six hours the German armoured divisions were late, the 15th starting at 1 p.m. and the 21st (whose commander, Major-General von

The Battle of Alam el Halfa, 30th–31st August

Bismarck, was killed during the day) about 2 p.m. They were soon being hit hard by the British guns and tanks, and at dusk Vaerst decided to cease the attack.

The Battle of Alam el Halfa, 30th–31st August

As soon as Montgomery’s staff had discerned the position and intentions of the Africa Corps, the 23rd Armoured Brigade was moved into the gap between the New Zealand division and the 10th Armoured Division. When night fell the air force lit up the desert with flares and attacked the enemy’s vehicles without ceasing, and soon clouds of smoke were rising from petrol fires and burning vehicles.

On the 1st the Africa Corps made little progress and was struck hard by day-bombers. The 21st Armoured Division did not move, perhaps for want of fuel, but the 15th again tried to work round the flank of the main concentration of British armour. Throughout the day the German armour was “under constant bombardment from guns and aircraft”.46 Montgomery ordered the 2nd South African Brigade to move to a position north of Alam el Halfa, and warned the New Zealand division to prepare to attack southward across the enemy’s line of communication.

By the end of the day the air attacks had severely damaged the 3rd and 33rd Reconnaissance Units on the enemy’s right flank and they were in a bad way; but the 15th Armoured Division was still threatening Point 132. According to the Armoured Army of Africa’s diary, however, petrol supplies were now assured only until 5th September. “The position was so serious that it was necessary to break off the offensive for the time being and go over to the defensive.”

Next day Montgomery was offered the opportunity to attempt a dramatic counter-stroke in force behind the German armour sprawled to the south of the XIII Corps; but the army commander who had earlier warned Horrocks to husband his armour for a later offensive was apparently still of the same mind. He decided to continue with the infantry attack being prepared by Freyberg to close the gap where the enemy had penetrated but to hold his armour to its defensive role. Optimism was shaping the plans as much as farsightedness, however, for the attack was directed to proceed with such forces as had been allotted, in the expectation that it would succeed. The attack, to be made by Freyberg’s own 5th and 6th Brigades and the 132nd British Brigade, was to open on the night of the 3rd–4th. Freyberg was to advance three miles southward in the first phase and a further three miles in the second. The initial thrust was to be made by the 132nd Brigade on the right and 5th New Zealand Brigade on the left, each with a squadron of Valentines.

Montgomery was doubtless wise not to hustle Freyberg into an earlier hasty attack – as it was, there was hastiness in some of the preparations – but the enemy had meanwhile been strengthening his defences at his most vulnerable point. The raw 132nd Brigade left the start-line about an hour late, on the night of the 3rd, and came under heavy fire which wounded the commander; the units fell into some confusion. The 5th New Zealand Brigade reached its objective after hard fighting and defeated two counterattacks. Montgomery and Horrocks agreed with Freyberg, however, that a renewed attack was unlikely to succeed and that his brigades should withdraw (the 5th had had 275 casualties and the 132nd 697). This they did that night. More effective than the counter-attack was the continued onslaught of the air force. By 4th September the Africa Corps had had 170 vehicles destroyed and 270 damaged by air attack, and petrol supplies were now gravely depleted.

In the next few days the enemy withdrew as he had planned, and was not pressed. He was left in advantageous possession of the British minefields where the front had been breached and of Himeimat – an eminence 700 feet high that dominated the landscape in the southern parts of El Alamein. Horrocks protested at this but Montgomery firmly declined to contest the ground taken.47 “The impression we gained of the new British commander, General Montgomery,” wrote Rommel, “was that of a very cautious man, who was not prepared to take any sort of risk.”48

In their attack the Germans lost 1,859 killed, wounded or missing and

the Italians 1,051; 49 tanks were destroyed. The British lost 1,750 killed, wounded or missing and 67 tanks Mellenthin later described Alam el Halfa as “the turning point of the desert war, and the first of the long series of defeats on every front which foreshadowed the collapse of Germany”.49

While the German attack was in progress the 1st South African Brigade had carried out a raid supported by heavy artillery fire and collected 56 prisoners of the Trento Division.

A diversionary attack by part of the Ramcke Brigade on the 9th Indian Brigade at Ruweisat Ridge penetrated the defenders’ positions and led to a counter-attack by infantry and a squadron of tanks. The Ramcke lost 11 killed or wounded and 49 were missing.

–:–

The 9th Division’s diversionary attack – Operation BULIMBA – was launched by the 20th Brigade just before dawn on the first day of the battle. West Point 23 had been chosen as the sector of the enemy’s line to be secured for a bridgehead for several reasons; it was distant from the commanding Sidi Abd el Rahman features which were strongly held by the enemy and also was partly defiladed from enemy positions to the south; it gave observation over the desert for several miles; and the “going” between the Australian forward positions and the objective was suitable for wheeled vehicles.