Chapter 15: The Dog Fight

There is no absolute measure of success or failure in war. Though a nation may win a war, when peace ensues it may find itself at a disadvantage. Of the success or failure of a military enterprise as such, however, final victory or defeat is the last judgment. Judged as a contribution to the outcome of the battle, the first night’s attack at El Alamein was the foundation of the victory, though judged only in terms of the objectives prescribed, the attack had not succeeded.

As observed in the last chapter, the main reason for the XXX Corps’ failure to take all its objectives up to the Oxalic line had been that the plan had asked too much of the infantry. Not even with unexampled skill and valour could tasks of such magnitude have been completely accomplished. Likewise the main explanation of the 8th Armoured Brigade’s failure to debouch into the enemy rear even though its bridgehead to the Oxalic line had been cleared was that the plan had demanded the impossible in requiring the armour to give battle on ground of its choosing in the enemy’s rear without becoming embroiled on the way, for the ground chosen and the routes from the Oxalic line to it had been fortified by the enemy against tank attack, contrariwise to the assumptions on which the plan had originally been based. To ordain that the armour should give battle on ground of its own choosing was one matter; to expect it to attack ground prepared by the enemy to resist armoured attack, quite another.

Faced with the problem that the bridgehead had failed to span the enemy’s zone of anti-tank defence the Eighth Army had several courses open to it to persuade the enemy’s armour to join battle so that it might be destroyed. The existing bridgehead could be extended to overreach the remaining tank-proof localities, a new bridgehead could be pushed through on a weaker part of the front, or the enemy could be enticed, by the methodical destruction of his infantry from the existing bridgehead, to launch attacks against ground already prepared in tank defence, as Montgomery’s exposition of his second plan had foreshadowed; or some combination of these courses might be tried. These possibilities should be kept in mind as the subsequent course of the battle is followed.

On the morning of the 24th the attention of the armoured commanders, the corps commanders and the army commander himself was attracted to the Miteiriya Ridge sector where the Oxalic line had been reached and lanes for the passage of armour cleared. General Freyberg, forward in his tank in the early morning, was perturbed at the reluctance of the 10th Armoured Division’s tanks to push forward. Unable to contact Lumsden, he sent a message to Leese, who thereupon came forward to see Freyberg. Leese and Freyberg reconnoitred the front together and then returned to Freyberg’s headquarters to confer by the “blower” with Montgomery. There Lumsden soon joined them, having seen nothing that

morning, it may be presumed, to diminish his dislike of issuing in line ahead through minefield lanes to attack an enemy gun-line. Freyberg, whose counsel the higher commanders probably valued more highly than anybody’s, thought that the attack should be resumed that night, which may have helped the corps commanders to reach the same conclusion. Montgomery probably needed no prodding to decide that the risks could, should and would be accepted. Montgomery told Lumsden that the 10th Armoured Division was to get out into the open and manoeuvre beyond the Miteiriya Ridge.

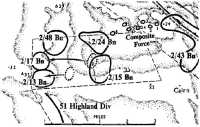

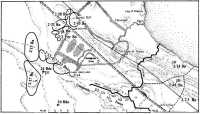

In outline Montgomery’s orders for the continuation of the battle were, with some modifications, to carry out by the morning of the 25th such of the tasks ordained for the 24th as had not been completed. The 9th Australian and 51st Highland Divisions were to secure the rest of the Oxalic line, the armour was to debouch by night and advance to the Pierson bound. The action of the armour, however, was not to be dependent on completion of the infantry tasks – the armoured divisions were to fight their own way forward. The 1st and 10th Armoured Divisions were to advance westwards, the 9th Armoured Brigade and the New Zealand division’s cavalry (armed with Honeys) southwards, all four armoured brigades to link on the Pierson bound. The thrust of the 9th Armoured Brigade was to prepare the way for later southward infantry thrusts by the New Zealand division. The 133rd Lorried Infantry Brigade from the 10th Armoured Division was to take over the part of the New Zealand front adjoining the Highland division. De Guingand later recorded that Lumsden was “obviously not very happy about the role his armour had been given” and Montgomery wrote that he told Lumsden to “drive” his divisional commanders.1 In the XIII Corps the 44th and 7th Armoured Divisions were also to carry out their tasks uncompleted on the first day.

By daylight that morning the 9th Division’s front had erupted with fire of every kind – fire from field guns, machine-guns, mortars and snipers directed at the infantry, high velocity fire aimed at the tanks, and fire from British tanks and guns in rear engaging targets. The pandemonium was to continue – with some periods of great intensity – for several days.

Soon after sunrise the forms of enemy tanks could be seen approaching from the west. The German 15th Armoured Division was coming in to make its first attack on the bridgehead. By 7.15 a.m. the tanks were reported about 1,000 yards west of the 2/48th’s left forward company and also forward of Trig 33. The battle-fire quickened. Soon the three Australian field regiments and the 7th Medium Regiment were firing pre-arranged concentrations on the areas into which the German tanks had moved and some Shermans in rear of the Highland division’s front and of the left flank of the Australians’ front were also engaging them. A little later lorried infantry appeared west of the 2/48th. In time the enemy armour drew back from its first encounter with the XXX Corps artillery and the Shermans’ long-range gunfire, leaving several tanks burning on the battlefield. Some Shermans were also burning.

The first big day-bombing attack by the Desert Air Force was allotted to the 9th Australian Division, which chose as target an enemy headquarters area 1,500 yards north of the northern flank of the attack. The bombing was timed for 8 a.m. The division had to indicate the target by smoke shells and to define the line of its own northern defences with blue smoke (from candles captured from the Germans). Although these signals were given, the 18 aircraft, flying at 18,000 feet and probably misled by the smoke on the 9th Australian and 51st Highland and 1st Armoured Divisions’ common battleground, dropped their 2,000-pound bombs on the 2/13th Battalion, 3,000 yards south of the target and 1,500 yards south of the blue smoke. But only four men were hit.2 It was an unfortunate prelude to very close and effective cooperation throughout the battle between the ground and air forces. Later that morning the RAF’s “tank-buster” squadron of heavily gunned Hurricanes attacked the Kiehl Group and reported that it had knocked out 18 of the Kiehl Group’s 19 tanks.3

On the northern flank the prospect at daylight had at once revealed that the tactical key to the security of the flank was Trig 29, north of Hammer’s battalion. Whitehead’s brigade, by comparison with other fronts, was faced by a less subdued enemy infantry, which the main artillery storm of the night assault had by-passed. Enemy artillery to the north was also active though most of its shelling was behind the forward battalions, but soon the enemy began patrolling to find the flank of the penetration.

Meanwhile sappers were busy throughout the day widening lanes, bringing the Diamond, Boomerang, Double Bar and Square tracks up to the foremost localities and clearing minefields from congested areas. In the evening hot meals were brought right up to the forward troops.

On the Highland division’s front the lanes of the northern corridor for the armour were being pushed forward. By 9.30 a.m., the tanks were deployed about the double Point 24 ridge to the south of the Australian sector and in action there. One successful daylight infantry attack by the Scottish was made in the centre of the division’s front on an enemy locality that had resisted during the night and in the late afternoon tanks of an armoured regiment cleared other defended localities to extend a mine-free lane to the Oxalic line. Towards sunset the enemy armour (15th Armoured and Littorio Divisions) attacked out of the sun, the main weight being directed more against the Highland than the Australian front. The gunfire battle furiously quickened and the Australians saw “Priests” in action for the first time. The firing continued until dark. Twenty to thirty tanks were destroyed on either side; but the Germans had to destroy British tanks in about the ratio of four to one if they were to retain a chance of avoiding armoured defeat, and that they did not do.

On the New Zealand front, tanks of the 9th Armoured Brigade and some of the 8th Armoured had fought a force of 30 to 40 enemy tanks during the morning until most of the British tanks had been knocked out.

The survivors then took up advantageous hull-down positions behind the crest of the Miteiriya Ridge.

–:–

At 4 p.m. the commanding officer of the 2/13th Battalion, Colonel Turner, and the adjutant, Captain Leach,4 were wounded, Turner mortally; both had to be evacuated. Major Colvin5 was promptly brought forward to take over and, on the way, received orders from Brigadier Wrigley for the renewed attack up to the Oxalic line, which was to open at 2 a.m. next morning. The 20th Brigade was to capture the ground originally assigned to the 2/13th on the first night, but the task was now to be carried out by two battalions, the 2/17th on the right, 2/13th on the left. The attack was to be made with full artillery support. After the Australians had secured their objective the 7/Rifle Brigade was to pass through, take Point 32 and form a bridgehead for the tanks beyond the Oxalic line.

Colvin found the 2/13th practically without officers, and General Morshead agreed to allow all left-out-of-battle officers to be sent forward. Early that night Sergeant Easter of the 2/13th, who had a reputation for cool and reliable judgment under fire, returned from a patrol which had failed to find any sign of the 1/Gordons on the battalion’s left.6 He expressed the opinion that there would not be much opposition to the night attack. Thereupon Colvin conferred with Colonel Simpson of the 2/17th and it was agreed to make a silent attack without artillery support. The 40th Royal Tank Regiment was to support the attack.

The attack by the two battalions was timed to open at 2 a.m. on the 25th. Just before it began a single enemy plane, probably looking for the armour, dropped a flare and then bombed the start-line, but without causing harm. The 2/17th on the right advanced with two companies forward, took the objective without having to fight for it and began to dig in. The battalion’s vehicles came forward but soon afterwards were shelled and bombed by aircraft. An anti-tank gun portee was set alight there and also an ammunition vehicle in the 2/13th’s area, both providing most unwelcome illumination. Some enemy posts nearby began harassing the 2/17th with machine-gun fire as reorganisation proceeded. In the right company Lieutenant Wray7 was a steadying influence walking through it all pipe in mouth while carrying a heavy load of mixed ammunition for one of his sections which had reported that it was running short. A vehicle in charge of Sergeant Cortis8 of the machine-gun platoon was hit and set alight, but Cortis coolly off-limbered a gun, got it into action,

Dawn, 25th October

engaged some of the enemy posts and silenced them. Captain McCulloch9 of the left forward company was killed by machine-gun fire and the company’s only remaining officer wounded; Sergeant Williams10 took command. The men were very weary and jaded, having been without sleep for 48 hours and throughout that time frequently under intense fire.

On the left the 2/13th had encountered machine-gun fire after about 500 yards but advanced through it. The right company surprised two posts and took the occupants prisoner. By 3.15 a.m. the troops were digging in on the objective with patrols out. The enemy began to lash the forward companies with machine-gun fire from close in front, but the 40th Royal Tanks came up behind and effectively engaged the enemy nests with tracer machine-gun fire. At 4.50 a.m. contact had been made with the Gordons on the left. By 7 a.m. shallow digging had been completed and supporting arms sited.

Before dawn the air was raucous with the noise of tanks approaching from the rear but the 7/Rifle Brigade had not yet appeared when the horizon showed the first signs of approaching day.

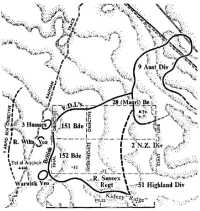

The break-out battle was soon to reach its climax. On the Highland front the main tank force of the 1st Armoured Division (2nd Armoured Brigade) had been moving up to the Oxalic line except on the division’s left where an enemy strong-point, which the division had lacked the strength to attack, still held out to the right of the gallant 7/Black Watch. It was beyond the Highlanders, however, where the southern bridgehead reached across the Miteiriya Ridge, that the battle’s most dramatic developments had been occurring that night. An hour and a half had been allowed to the sappers to clear lanes forward for each armoured regiment before, at 10 p.m., the guns fired the barrage behind which the three armoured brigades of the 10th Armoured Division were to debouch. The time proved all too short and the enemy, as could hardly have been otherwise, was expectant and ready for counter-strokes.

The 8th Armoured Brigade, in the centre, encountered the greatest misfortune. On one lane (Hat track) the enemy captured the mine reconnaissance party and the exit was covered by at least one 88-mm gun. The lane was abandoned. It was then decided that two regiments, the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry and 3rd Royal Tanks, would use the Boat track but

enemy aircraft reconnoitred with flares when the bombardment opened and the Notts Yeomanry were bombed with high explosive and incendiaries and shelled, so that the lane was soon illuminated by burning vehicles, in the light of which the column was harassed by enemy fire. It was decided that this lane was also unusable. The commander of the 10th Armoured Division, General Gatehouse, who was on the Boat track, had seen all this. Lumsden called for a report from Gatehouse.

Irreconcilable accounts have been given of the incidents that followed in which Montgomery, Lumsden and Gatehouse figured and the “friction of war” manifested itself and to which perhaps too much publicity has since been given. It must suffice to recount some salient facts that do not appear to have been disputed. Gatehouse feared that daylight would find his regiments exposed and vulnerable and likely to be shot to pieces by the enemy’s anti-tank artillery. Lumsden, who had no authority to break off the attack, reported this to army headquarters, which was also keeping closely in touch through report centres and by analysing what could be heard of the much-jammed radio traffic. De Guingand concluded that “a feeling in some quarters was creeping in which favoured suspending the forward move, a pulling back under cover of the (Miteiriya) ridge” and decided to take what was apparently regarded as a risk even on that battlefield. He woke the army commander and called a conference with the corps commanders for 3.30 a.m.

Three of the four armoured brigades to make the advance to the Pierson line had encountered no insuperable difficulties or problems beyond those to be expected in such a difficult operation. It is understandable, therefore, that the army commander should have decided that the operation should proceed, for he could expect at least some 400 tanks to debouch. He gave very firm instructions that they should. The original orders were partly changed, however, presumably in recognition of the fact that only one of the 8th Armoured Brigade’s three lanes – the Bottle track on which the Staffordshire Yeomanry were to debouch – was regarded as usable. One of the brigade’s three regiments was to advance and link with the New Zealand division’s 9th Armoured Brigade but the rest of the brigade was to remain on the Miteiriya Ridge and improve the gaps. After the conference Montgomery kept Lumsden behind and (he has since written) “spoke very plainly to him ... any wavering or lack of firmness now would be fatal. If he himself, or the Commander 10th Armoured Division, was not ‘for it’, then I would appoint others who were.”11

Gatehouse was no less averse than Morshead to accepting orders to commit his troops to operations which he thought unjustifiable but by comparison was less advantageously placed, not deriving his authority directly from a government. Lumsden wished Gatehouse to receive the instructions from the army commander himself. Gatehouse had gone back to his main headquarters so that he could be contacted by telephone, and there Montgomery telephoned him. Montgomery spoke “in no uncertain

voice” and nettled Gatehouse by ordering him “to go forward at once and take charge of his battle”.12

The orders were masterful. It remains to see what effect they had on the battle. On the left of the 9th Division’s area dawn on the 25th revealed the Queen’s Bays deploying among the infantry close to the end of the bridgehead, the tank commanders, dressed with great individuality for the hunt and bedecked with colourful cravats, standing up in their cock-pits unperturbed by the battle-fire’s cacophony and coolly surveying the terrain. There and for some considerable distance to the south the armoured brigade’s tanks sat about the foremost defended localities, the target of a vigorous bombardment, as if the limit of their advance had been reached. However hard and however often the “GO” button had been pressed on the army control panel, its impulses were not motivating these tanks whose commanders, though as brave as they were bizarre, evinced no intention to advance “at all costs” to the Pierson bound. Their presence there to do battle was not very welcome to the infantry who regarded the ground of the armour’s choosing as their own. Meanwhile about 6 a.m. part of the 7/Rifle Brigade had arrived in rear of the 2/13th’s forward companies where their vehicles attracted heavy fire, having insufficient space between the minefields for proper dispersal.

The enemy gunners were not too proud to shoot at sitting ducks. The carnage was terrible to watch. ... It was not long before a flood of casualties swamped the 2/13th R.A.P. which was already working at full pressure to cope with the unit’s own casualties. Captain Phil Goode and his men were equal to the occasion.13

Other Rifle Brigade vehicles which, as the Australians read the map and ground, appeared to have made not for Trig 33 but Point 29 farther south, were also stricken near Kidney Ridge behind which the Highlanders’ forward line had been established. Farther to the right, in front of the 2/17th Battalion, enemy infantry formed up to attack but were halted by artillery fire.

In the southern part of the XXX Corps front, however, the armour had advanced to places near the Pierson bound. The 24th Armoured Brigade on the right believed that it had two regiments on its objective (the third was in reserve behind the Miteiriya Ridge), though probably they were not in fact so far forward. The 8th, which had been pressing forward on its hard task while the generals had been conferring, had got all three of its regiments out by the Bottle track before the revised orders from Eighth Army Headquarters reached it. The Staffordshire Yeomanry, which had debouched first, was about the El Wishka ridge where soon after dawn concealed 88-mm guns put in hand a systematic destruction of its tanks.

The sappers of the New Zealand division had cleared and marked their lanes on time. The divisional cavalry (“Honey” tanks) on its way from the Oxalic line to its objective two miles to the south in an area southwest of El Wishka was soon met by intense fire. By 1.45 a.m. the regiment

had lost 5 tanks and 4 carriers. It withdrew at dawn. The 9th Armoured Brigade had passed through the gaps at 2 a.m. (one regiment using one of the lanes abandoned by the 8th Brigade) and advanced south and south-west almost to the Pierson bound.

In the deep south the operations of the XIII Corps had been less successful. The February minefield was cleared but a wide bridgehead had not been secured and the tanks of the 7th Armoured Division’s 22nd Armoured Brigade were shot up by anti-tank guns nearby while trying to debouch. Thirty-one tanks were lost and the exits blocked. A successful infantry attack was made in the Munassib Depression, but was very costly in loss of life.

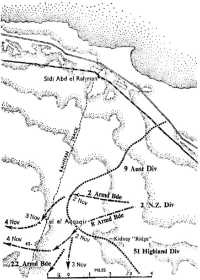

The armoured battles that day, though on balance advantageous to the Eighth Army, achieved less than Montgomery had hoped. In the course of the day most of the tanks were withdrawn from the positions they took up in the early morning. On the right the Bays, who seemed unable to locate where the fire directed at them was coming from, soon withdrew to some place beyond the Australians’ ken (where they were in action later in the day); but farther south, in front of the Highland division, tanks of the 2nd Armoured Brigade remained out with the 24th Armoured Brigade to their left. On the left Gatehouse withdrew the 8th Armoured Brigade behind the Miteiriya Ridge about 7 a.m. when he learnt of the casualties it was taking. The main body of the 9th Armoured Brigade, which was in a depression overlooked by enemy on El Wishka and enduring damaging fire, remained out until the afternoon, when it was withdrawn behind the Oxalic line. It had suffered 162 casualties and many of its tanks were knocked out (all but 11, however, were recovered later).

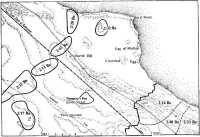

Probing attacks rather than hammerhead punches were made by the Axis armour throughout the day all along the front, which was what Montgomery wanted. The 1st Armoured Division lost 24 tanks but claimed the destruction of more than twice as many of the enemy. In the struggle for armoured superiority the scales had been tipped further to the advantage of the British. The following tables enable a comparison to be made of British and Axis tank strengths approximately from formation to formation as they were disposed from north to south on the 23rd and 25th October (progressive totals being shown in brackets).

Eighth Army (as at midday)

(The table does not include a substantial number of tanks – e.g. cavalry units – in other than armoured formations.)

| 23rd October | 25th October | |||

| Formation Totals | Progressive Total | Formation Totals | Progressive Total | |

| North: | ||||

| 1st Armoured Division | 169 | 149 | ||

| 10th Armoured Division | 280 | (449) | 167 | (316) |

| 9th Armoured Brigade | 122 | (571) | 92 | (408) |

| 23rd Armoured Brigade | 194 | (765) | 135 | (543) |

| South: | ||||

| 7th Armoured Division | 214 | (979) | 191 | (734) |

Axis Forces

| 23rd October | 25th October | |||

| Formation Totals | Progressive Total | Formation Totals | Progressive Total | |

| North: | ||||

|

15th Armoured Division |

112 | 37 | ||

| Littorio Division | 115 | (227) | 108 | (145) |

| South: | ||||

|

21st Armoured Division |

137 | 122 | ||

|

Ariete |

129 | (266) | 125 | (247) |

| Total North and South (excluding Trieste) | (493) | (392) | ||

| German armoured formations | 249 | 159 | ||

| Italian armoured formations (excluding Trieste) | 244 | (493) | 233 | (392) |

| Trieste | 34 | (527) | 34 | (426) |

Although the figures are not exactly comparable, if one regards the critical tank strengths in the armoured break-out battle of X Corps as those of its two armoured divisions plus the 9th Armoured Brigade on the one hand and of the two German armoured divisions on the other, the fall in the British strength from 571 tanks to 408 may be compared with the German fall from 112 to 37 in the 15th Armoured Division opposite X Corps and from 249 to 159 overall.

Nevertheless the German anti-tank cordon had not been prised open. The armoured brigades had been unable to establish a firm base on the “chosen” ground onto which they had debouched because they had taken with them only light mobile infantry (used mainly to muster prisoners) who could neither seize the gun areas nor firmly hold the ground.

On the broader level, the men of the 10th Armoured Division had proved Montgomery’s belief that, with their own resources, they could fight their way through to an objective, but the enemy guns had shown that they could not stay there by daylight alone.14

The 9th Division had its share that day of the enemy counter-attacks on the bridgehead. On the northern front a German patrol was shot up in the early hours of the morning by the 2/48th Battalion and later, about 1.20 p.m., a strong infantry attack on the battalion was launched but defeated by artillery and mortar fire. Another attack on the 2/48th by about 300 infantry was thrown back towards the end of the day.

Attacks in which tanks were employed were made from the west against the 20th Brigade. Just after 7 a.m. 12 tanks followed by infantry in 50 troop carriers hove into view but were halted by fire from the artillery and the foremost British tanks. In the early afternoon tank attacks were made almost simultaneously on the 2/17th and 2/13th Battalions. The tanks were first seen on the 2/17th front where a remarkable fire-storm was soon raging. Deterred by the intensity of their reception they came to

a halt beyond two-pounder range, but 15 were hit by heavier weapons. The enemy put down a smoke screen through which another wave of tanks emerged to attack the 2/13th Battalion front. Colvin instructed the anti-tank gunners to hold the fire of their well-concealed 2-pounder guns until the tanks were within short range. About 800 yards from the foremost defences some tanks halted hull-down; the rest drove on. So well did the gunners bide their orders that it looked as if the tanks would pass through the front-line unopposed. Sergeant Bentley15 commanding the antitank platoon waited until the foremost was 40 yards away, then fired, whereupon the other anti-tank guns opened up and the first wave, all hit, came to a stop. In all 17 tanks were destroyed – nine by Lieutenant Wallder’s16 troops of the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, five by Bentley and two by Private Taylor.17 The other tanks drew out of range but then waited while the infantry got ready to assault.

The enemy pressed the attack for an hour and a half on the 2/13th front and a further half-hour against the 2/17th. The intense fire that accompanied it took many casualties. The 2/17th, for example, lost 12 killed and 73 wounded through the day. Throughout it all the artillery observation post officers, Captain Jones with the 2/13th, Lieutenant Rodriguez18 with the 2/17th, stood up to observe and direct the gunfire

On the morning of the 25th Freyberg persuaded Leese and Montgomery to cancel the proposed southward infantry attacks of the New Zealand division. Freyberg thought that the main infantry attack had not failed by much to pierce the enemy’s defence girdle and that therefore a further westward infantry attack on the pattern of the first should be made to extend the bridgehead. Again the top commanders conferred at the New Zealand division’s headquarters. Montgomery decided about midday to cancel the New Zealand division’s “crumbling” operations because (according to Montgomery and de Guingand) they were likely to prove very costly, and instead to start “crumbling” on the northern flank, using the 9th Australian Division. The armour was to be withdrawn except on the north of the XXX Corps front (where the 1st Armoured Division took the 24th Armoured Brigade under command) and in the far south the XIII Corps was to go over entirely to the defensive.

Montgomery’s decision to attack in the north has usually been represented as a calculated switching of the direction of attack initiated after the failure of that morning’s armoured sortie so as to retain the initiative and keep the enemy dancing to the Eighth Army’s tune. It was not as clear-cut as that, however, for although the final orders for the switch were then given, the decision to begin the northward crumbling had been

foreshadowed earlier; and before the dawn that morning had revealed the peril to which the 8th and 9th Armoured Brigades had been exposed, Lieut-Colonel Hammer of the 2/48th had given his company commanders preliminary instructions for an attack to be made on Trig 29 next night. The 9th Division’s written operation order was issued at 1 p.m. The explanation of this switch given in the division’s report on LIGHTFOOT probably puts it in better perspective:

The only portion of the original plan still untried was the tentative portion for the cutting off and capture of the enemy between XXX Corps’ northern flank and the sea. Orders were given to 9 Aust Div through XXX Corps for this to proceed.

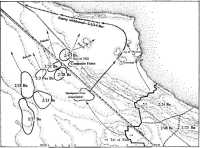

The 9th Division’s instructions were to begin attacking northwards towards the sea with the ultimate object of destroying the enemy forces in the salient that had been formed by the advancement of the Eighth Army’s northern flank. The 1st Armoured Division was also to continue its attack west and north-west and if possible to get to the rear of the enemy in the salient. Written instructions by the XXX Corps on the 25th required the 9th Division to attack and seize the Trig 29 area that night. As a diversion the 1st South African Division was to carry out at 10 p.m. an artillery program simulating an attack in its sector.

The tactical value of the hill known as Trig 29 had been appreciated before the battle opened. It dominated the northern flank, being the highest ground thereabouts, though by only 20 feet. The already too broad frontage of the first night’s attack could not be extended to include the hill but it had been chosen as the first exploitation task on that front. Morshead warned Brigadier Whitehead on 24th October to be ready to take Trig 29 and the warning, as we have seen, was passed down in turn to Lieut-Colonel Hammer and, by him, to his company commanders.

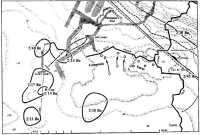

The 9th Division’s task was to seize not only Trig 29 but the spur and the forward slopes of the high ground running out to the east of it. In effect the northern front was to be advanced about 1,000 yards. It is of some interest to observe that the fronts to be defended on completion of the task by the division’s five bridgehead battalions (four up and one in depth) would extend on the west for about 5,000 yards and on the north for 4,000 yards.

The orders required Whitehead’s brigade to advance its whole northern front from Trig 29 on the left to the front edge of the enemy’s defence line on the right. North-east from where the 2/48th Battalion’s right company now sat, a strong enemy switch-line ran up to Thompson’s Post as a second line of defence against an attacker breaking through the front wire where it ran out to Point 23 (as the 2/15th did at BULIMBA) and then thrusting towards the coast road. The junction of the switch line with the front wire was an easily recognisable feature on ground and map – the Fig Orchard, which was down the forward slope of the ridge of which Trig 29 was the summit. The orders to the 26th Brigade were to employ the 2/48th and 2/24th Battalions – the 2/23rd still being held as a reserve behind the composite force – to seize Trig 29, the spur on the eastern side of Trig 29 pointing to the Fig Orchard, and the orchard itself. The

20th Brigade was to relieve the 2/48th on the part of the front it then held and the 24th Brigade to relieve Macarthur-Onslow’s composite force of three of its posts so that it could extend its front to link with the 2/24th Battalion on its objective. Whitehead allotted the left objective, the Trig 29 area, to the 2/48th and the Fig Orchard to the 2/24th.

Colonel Hammer of the 2/48th made a bold and original plan of fire and quick movement for what was to prove a model battalion attack executed with precision, vigour, and great courage. He planned to advance on Trig 29 under cover of a barrage with two companies forward and, just as the barrage lifted, to rush a third company on to the objective in 29 carriers and other vehicles. Ten carriers were to carry the two leading platoons of the mobile company; four carriers towing 37-mm anti-tank guns were to follow, and after them a troop of 6-pounder anti-tank guns with the third platoon mounted on the portees.19

After the 2/48th had begun to attack, the 2/24th was to form up in part of the area of the first phase of the 2/48th’s attack and thrust northeast, rolling up the flank of the switch line. Macarthur-Onslow’s force was to push its line of defensive posts northward to conform with the 2/24th’s new front.

A counter-attack was expected on the 2/48th’s front but did not develop. At dusk an enemy group was seen near the forward companies and fired on. Several Germans were killed and three captured including the acting commanders of the 125th Regiment and of that regiment’s II Battalion. The battalion commander had a map of the area to be attacked that night showing the enemy’s minefields and the disposition of his troops. The map showed that the track leading to Trig 29 along which Hammer’s carriers were to advance was free of mines; this was confirmed by Hammer’s interrogation of the prisoners. Interrogation also established that the Germans had just reinforced Trig 29.

To have captured the map was rare good fortune. When it was studied at Whitehead’s headquarters it revealed that the planned axis of the 2/24th’s attack ran straight along the leg of a minefield. The forming-up place and bearing of attack were therefore altered so that the sappers, instead of having to clear mines to a depth of 1,000 yards or more, would require to make only one gap 200 yards deep.

The 2/17th relieved the 2/48th at 10 p.m. on the 25th. The barrage opened at midnight and the leading companies of the 2/48th moved forward on foot, Captain Robbins’ company on the right, Captain Shillaker’s on the left. They pressed on through enemy defensive fire – which became particularly heavy on the right – to their intermediate objective some 200 yards short of Trig 29, and halted. Then the carriers under Captain Isaksson moving four abreast with Captain Bryant’s company aboard charged through with synchronised timing onto the smoky dust-shrouded centre objective as the barrage stopped.

When the carriers reached the spur the infantry leapt out and charged, one platoon moving left and one right while one went straight on to Trig 29. The surprised defenders were overcome but only after sharp hand-to-hand fighting. When Corporal Kennedy,20 for example, led his section against enemy posts that were engaging them with small-arms fire and grenades, the blast from a grenade knocked one of his men down; Kennedy helped him to his feet, dashed forward and killed two Germans with a grenade and farther on charged and bayoneted another German.

Bryant ordered one of his platoons to attack a troublesome post. Corporal Albrecht,21 leading his section to attack it, found that it was a dug-in tank. Albrecht charged forward and knocked out the crew with grenades, and though wounded by shell fragments and covered with blood, continued to lead and control his section, refusing to be taken back until it was firmly dug in.

Captain Robbins’ company on the right had taken heavy casualties from fire about 400 yards from the start and soon Robbins was the only remaining officer. The company pressed on nevertheless and secured its objective 1,100 yards from the start-line, taking 38 German prisoners.

Captain Shillaker’s company also had to fight its way to the objective. Lieutenant Taggart22 and four others in his platoon were killed attacking a series of posts that were holding up the company. The platoon became pinned to the ground and soon was only seven strong. Two of these, Private Gratwick23 (aged 40) and Corporal Lindsey,24 jumped up and raced forward to assault. Gratwick, with rifle and bayonet in one hand and a grenade in the other, charged the nearest post, threw in one grenade, then another, then jumped in with the bayonet. He killed all the occupants, including a complete mortar crew, then charged a second post with rifle and bayonet but, as he closed on it, was killed by a burst of machine-gun fire. Shillaker saw that Gratwick had unnerved the enemy and at once moved in and the whole position was quickly captured. The men began digging in very rocky soil.

As soon as the objective had been taken Colonel Hammer contacted Major Tucker and asked him to bring forward the vehicles loaded with consolidation stores, which were being held back along the track some 500 to 600 yards to the east of the point from which the attack had started. Just at that moment a stray shell hit a mine-laden truck which with five other trucks also loaded with mines exploded with an astounding detonation. Tucker was at first dazed, but soon got the undestroyed vehicles moving and sent Captain Potter25 back to “B” Echelon. Potter

returned with five composite reorganisation stores trucks. By first light 2,000 mines had been laid. Bryant’s company was facing north, Shillaker’s west. Edmunds’ company, on the battalion’s left, facing west and northwest, had linked with the 2/17th Battalion in the 2/48th’s old positions. The battalion was now firmly established, though only shallow trenches had been dug and everyone was very weary.

Meanwhile at 12.40 a.m. the two leading companies of the 2/24th had crossed the start-line, striking north-eastwards on the right of the 2/48th. It had been realised that an advance of 3,000 yards along a line of enemy posts was a difficult assignment but the army’s Intelligence service expected them to be held by Italians. On the contrary they proved to be mainly held by Germans, and where there were Italians there were usually Germans with them.

Major Mollard’s company on the right attacked along the frontal wire with one platoon in front of the wire and two on the left behind it. They fought their way forward without any serious check until less than 100 yards from the company objective when they were held up by a strong-post. This was assaulted and taken but not before Mollard had received a disabling wound. The post was found to have a garrison of more than 40 mixed Germans and Italians and to house an 88-mm gun. Captain Mackenzie26 led the company forward to its objective.

The left leading company under Lieutenant Geale27 had to advance the prescribed distance then move left, contact the 2/48th Battalion and dig in on the north-east spur of Trig 29. This the company did but Geale was badly wounded and Lieutenant Doughan,28 the only surviving officer took over. Doughan was wounded later in the day and Sergeant-Major Bailey29 then took command. A number of posts were taken. Sergeant Berry30 was foremost in the affray in the attack on three of these and took two positions single-handed.

Captain Harty (on the right) and Lieutenant Greatorex followed up the centre-line, then led their companies through the forward companies towards the Fig Orchard. Each had to overcome three posts on the way. Harty’s company took the Fig Orchard post, which was found to be a headquarters with offices sunk in the ground to great depth. Greatorex’s company overshot the Fig Orchard and came up near the outer edge of the defences covering the big defended locality known as Thompson’s Post. Both companies were troubled by anti-tank and mortar fire from a post 300 yards ahead. Harty and Greatorex reconnoitred to plan an assault. Greatorex was wounded (for the second time that night) and Sergeant-Major Cameron31 taking charge of his company got permission

Dawn, 26th October

to withdraw it – now numbering only 14 of the 63 who started – to alongside Harty’s.

The 2/24th had carried out a methodical destruction of the enemy as prescribed by the master plan, to which the number of enemy dead and of prisoners bore witness,32 but Colonel Weir, after going forward, decided at 4 a.m. that the battalion was too depleted to hold the extended front on which his men were digging in. The forward companies were therefore withdrawn about 1,000 yards where by 5 a.m. they had consolidated behind a reverse slope running north-west from Point 22 to Trig 29. On the right flank the composite force, which had been held up in its advance by fire from Thompson’s Post, found itself in an exposed situation.

On that night of much action the enemy launched an attack with infantry and a few tanks against the 2/13th Battalion, following up by dark the daylight attack that had failed. Three tanks were knocked out by Hawkins mines and Treweeke’s company knocked out two tracked troop carriers when they were within 60 yards. Artillery and infantry-weapon fire broke up the attack. At dawn the 2/17th discerned 12 enemy tanks sitting on a ridge to the north-west, where they remained all day, harassing the Australians with guns and small-arms fire and knocking out vehicles. On the left of the divisional front the 1st Armoured Division made its morning visitation and the Australians saw 30 Sherman tanks engaging the enemy.

No foolhardy attempt was made to push through the enemy gun-line and behind the coast salient.

On the 25th–26th the division had taken a total of 173 German prisoners, all from the I, II or III Battalions of the 125th Regiment and 67 Italians of the Trento and Littorio Divisions. The 26th Brigade reported its casualties for the night as 4 officers and 51 others killed, 20 officers and 236 others wounded and missing.33

The 51st Highland Division also attacked that night overcoming some remaining centres of resistance near the left of its front which, except on the right at Kidney Ridge, was then clear of enemy strongpoints about the Oxalic line.

At dusk on the 25th Field Marshal Rommel arrived back from Germany to take over, at Hitler’s personal request, the conduct of the battle and received discouraging reports from General von Thoma, who had been exercising command.

“Our aim for the next few days,” he later wrote, “was to throw the enemy out of our main defence line at all costs and to reoccupy our old positions, in order to avoid having a westward bulge in our front.” Rommel listened to the artillery barrage that night and learnt that “Hill 28” (Trig 29)34 had been taken – “an important position in the northern sector”.

“Attacks were now launched on Hill 28 by elements of the 15th Armoured Division, the Littorio and a Bersaglieri Battalion,” wrote Rommel, “supported by the concentrated fire of all the local artillery and A.A. Unfortunately the attack gained ground very slowly. The British resisted desperately. Rivers of blood were poured out over miserable strips of land.”35

Attracted partly by activity of the 1st Armoured Division, which seemed to the enemy to be directed north-west towards the coast road, the Axis forces directed their main efforts on the 26th and 27th to breaking their enemy’s new front on the northern flank. The attacks started on the 26th and were mounted with increasing frequency and vigour on the 27th, a day of many stresses for the Eighth Army but no disaster, during which the artillery was continually called on for defensive fire.

The 27th was marked by a day-long continuous struggle (wrote a battalion historian). ... Those who were there that day may recall the extraordinary rising and falling waves of sound. All the different weapons appeared to be co-ordinated to produce a definite rhythm ranging from diminuendo to deafening crescendo and it went on hour after hour.36

The enemy vigorously bombarded the 2/24th and 2/48th in their newly seized positions on the morning of the 26th and more heavily still on the morning of the 27th but several of the guns were counter-bombarded with the help of observation from Trig 29 and forced to move back. There, on the most heavily shelled ground on the whole front, Lieutenant Menzies37 maintained an observation post with little cover for several days, directing the fire that broke up many counter-attacks, some while the enemy was forming up. The value of Trig 29 was now plainly evident: from it one could see 4,000 to 5,000 yards in every direction.

The enemy’s first effort against Trig 29 was made on the afternoon of the 26th, when 300 infantry moved into positions 1,500 yards to the north but were dispersed by gunfire. The 2/48th Battalion had three field regiments and one medium regiment on call at that stage and was able to defend itself with devastating fire.

The western front of the 20th Brigade was also attacked on the 26th. Three attacks by infantry and tanks, the main weight of which fell on the 2/13th, were repulsed on the afternoon of the 26th.

-:-

The subsequent continuation of the northward Australian attack is usually ascribed to Montgomery’s having “spent the day of the 26th in detailed consideration of the situation”.38 It was, however, no more than a further implementing of the direction to attack northwards given on the 25th, though the consequential army regrouping no doubt resulted from Montgomery’s day of pondering. Morshead had been instructed on the 25th to plan further northward operations to be mounted after the attack on Trig 29 at midnight on the 25th–26th. Montgomery, attended by Leese and Lumsden, held a conference at Morshead’s headquarters at 11.30 a.m. on the 26th to hear his proposals. “On previous day,” Morshead recorded in his notebook, “I had received orders to ‘go north’ and to have my firm plans ready today. The army commander fully approved plans without alteration.” The 9th Division’s attack was to be made on the night of the 28th. But first, on the night of the 26th, further thrusts were to be made to the west near the boundary of the Australian and Highland divisions. The 7th Motor Brigade was to capture two features in the Trig 33-Kidney Ridge area known as Woodcock and Snipe.

That day in the course of a tour of the XXX Corps front Montgomery spoke to several formation commanders. Freyberg still advocated another broad-front infantry attack but represented that if his own depleted division mounted the attack, it would then be unfit for its intended role in the exploitation phase.39 Montgomery also visited Wimberley; it is unlikely that Montgomery found him much more anxious than Freyberg to mount another large-scale attack. By dawn that morning the Eighth Army had lost 6,140 men killed, wounded or missing. It had expended much of its

strength; but although some ramparts had been taken, the strong enemy front showed no sign of collapse. The impulse to break the deadlock would have to come from the army commander himself. A new strong punch would be needed.

By the evening of the 26th Montgomery had decided that the New Zealand division should be withdrawn into reserve and rested, that the 1st Armoured Division should also be drawn into reserve for refitting and relieved by the 10th and that he would rely on the 9th Division’s northward attack to retain the initiative. Consequently a substantial regrouping was to be effected on the night of 27th–28th. The northward shift of the 9th Division and the withdrawal of the New Zealand division would greatly extend the front to be held by other formations. The XIII Corps was directed to make available all the infantry it could spare for operations in the north and to extend its front to include the South Africans’ sector. The 4th Indian Division was to relieve the South Africans and they in turn to relieve the New Zealanders, who would be withdrawn. The 51st Division was to relieve the 20th Australian Brigade thus enabling the 9th Division to have one brigade freed from holding duties and available to attack.

These instructions were given by Leese to Morshead and the other divisional commanders on the night of the 26th. It has been said that Leese was anxious as to how the proposals would be received, but he already knew Morshead’s plans. He told the divisional commanders that the stalemate must be broken and that Montgomery had decided to follow up the Australians’ success by a further thrust to the north. The Australians must draw everything they could on themselves. “He glanced at Morshead and saw no flicker of hesitancy disturb that swarthy face.”40 Just after these orders had been given, however, Morshead received a cable sent from Australia two days earlier, the full import and intention of which were not very clearly expressed, but which could have been construed in a way which would have critically prejudiced Montgomery’s plans to break the stalemate.

On 14th October the Australian Government had considered two documents relating to the defence of Australia: a statement by the President of the United States to the effect that a superior naval force concerned solely with the defence of Australia and New Zealand could not be provided, and a memorandum from General Blamey drawing attention to the weakness of the Australian land forces available to resist an invasion if a naval reverse were suffered. The War Cabinet asked the Chiefs of Staff to report on the forces needed to defend vital areas on the Australian mainland. Next day, however, having been told that General MacArthur was of the opinion that the time had now come for the return of the 9th Division, the War Cabinet decided to press for the division’s return and to cancel the approval previously given for the dispatch of 6,000 reinforcements.

On 17th October Mr Curtin sent a cable to Mr Churchill (and a copy to President Roosevelt) requesting the early return of the 9th Division and setting out in detail the reasons for making the request. In brief they were:–

Australia was at present 22,000 men short of the number required for the present order of battle in Australia.

From 7,000 to 8,000 personnel per month were needed to replace wastage against a prospective intake of 1,100 per month. Eight infantry battalions had therefore been disbanded and a further decrease of eleven battalions was contemplated.

The extreme tropical conditions in New Guinea caused a heavy wastage of combatant personnel.

Three Australian divisions were already in New Guinea. No further Australian formations could be sent there because of the depletion of forces available for the defence of the mainland.

Thus it would not be possible to maintain the flow of reinforcements needed by the 9th Division in the Middle East; if left in the Middle East, the division would, in a few months, cease to be an effective fighting unit. General MacArthur had expressed apprehension at the shrinkage of Army combat troops consequent on the reduction of Australian formations.

The Government, the message stated, would not consent to the breaking-up of the 9th Division “by replacement of wastage from ancillary or other units” in the Middle East; but the division could be built up in Australia by disbanding other formations. The Government had consulted its Advisory War Council, which had come to the unanimous conclusion that the division’s return should be requested.

On 20th October the Australian High Commissioner in London (Mr Bruce) informed the Australian Government that the British Chiefs of Staff were examining the problem with a view to the 9th Division’s return at the earliest possible date but, owing to the operation which was then imminent and the part in it that had been allocated to the division, the date of its withdrawal from the front line depended on developments in the immediate future. Mr Curtin replied on the 22nd that it was essential that the Commander-in-Chief, in his use of the division, should have regard for the fact that reinforcements could not be provided either by dispatch from Australia or breaking up units in the Middle East. There the matter had stood when the battle (of whose planning Curtin knew nothing) opened next day.

On 24th October a message had been sent from Australia to General Morshead informing him of the Australian Government’s request for the early return of the division to Australia and stating that he was being informed of this so that he might safeguard the Government’s decision. This was the message that reached Morshead just after he had attended the conference at which Leese had announced Montgomery’s intention of continuing the northward advance. Morshead replied to the Australian Government that he would see the Commander-in-Chief as soon as possible. This he did at 11 a.m. next morning, the 27th October, at Montgomery’s tactical headquarters.

After the interview, Morshead reported to the Australian Government that Alexander had not hitherto been informed of its decision but had said

that he could not consider the division’s release at that time, as it was the main pin of the operations and without it the battle would collapse; of all the formations in the Middle East, it was the one (Alexander had said) that he could least afford to lose. Morshead added that Alexander had undertaken to arrange its relief as soon as the operational situation permitted but had drafted a signal to London which concluded as follows:–

9th Australian Division playing very conspicuous and important part in present operations and it would be quite impossible to lose their magnificent services until present operations are brought to a successful conclusion.

In reply, the Australian War Cabinet instructed Morshead to ensure that the Government’s wishes were kept constantly in mind; which Morshead assured them that he would not fail to do.

Next day (the 28th) Churchill telegraphed Curtin:

You will have observed with pride and pleasure the distinguished part which the 9th Australian Division are playing in what may be an event of first magnitude.

Just after 4 a.m. on the 27th an attack on the 2/13th was made by “at least a company of infantry” just in front of 15 tanks. “Put down Fremantle urgently” was the message to the artillery recorded in the battalion’s Action Log. The concentrated bombardment, with the infantry fire-curtain in front of it, broke up the attack. A second attack was easily repulsed. Later that morning a patrol under Lieutenant Pope was sent out to clear the front for 400 yards. Covered by the patrol, Private Burgess41 took a telephone and cable 300 yards farther out and observed the front from a derelict tank, sent back reports which enabled enemy salvage parties to be engaged, also an 88-mm gun to be bombarded (which the enemy then withdrew) and later, having seen a group of the enemy, went across towards Kidney Ridge nearby and guided back a carrier of the 7th Motor Brigade, which rounded up 30 prisoners.

It was on the afternoon of the 27th, after the enemy had reconnoitred the ground with four tanks, that the pressure on Trig 29 became intense.

The next effort by the enemy (wrote the historian of the 2/48th Battalion) commenced near Sidi Rahman Mosque, where a great many vehicles began assembling. Word of this was passed back, and our bombers came in and straddled the area, leaving spirals of black smoke curling skywards. ... Two hours later enemy troop carriers moved into dead ground 1,400 yards from our front, and were engaged by indirect fire from our guns. Thirty minutes later, enemy infantry estimated at one battalion strength formed up and advanced towards our troops. A great wall of fire was put down by our three regiments of artillery to check them, and the battalion joined in with mortars, machine-guns and rifles. Trig 29 and the surrounding area now came under a terrific bombardment as the Germans supported their attack. The position became so clouded with dust and smoke that the order was given for the mortars and artillery to cease fire in order to give the machine-gunners a clear view of the enemy. The Germans were driven back, and commenced to dig in eight hundred yards from the forward troops. Very heavy casualties had been inflicted. The night was filled with cries of the wounded. Patrols sent out later reported that the battlefield was strewn with enemy dead.42

The Germans’ left wing came up against the left of the 2/24th Battalion, where an attack with infantry and tanks was pressed with some determination but broken up by a combination of artillery bombardment and mortar and machine-gun fire. The right wing of the German attack came in on the 2/17th Battalion but was beaten off 400 yards out from the forward infantry. Simultaneously the enemy also attacked the Kidney Ridge area with a powerful armoured thrust.

The so-called Kidney Ridge was a depression with raised lips around which the enemy had developed a powerful locality. Its continued resistance was the main reason for the 1st Armoured Division’s failure to advance much beyond the Oxalic line to attack behind the salient as the Australians had hoped. The 51st Highland Division and the 1st Armoured Division had been cooperating in attempts to clear the area but these had been attended with much misfortune mainly because of a misreading of the map in one of these two divisions. Throughout that day, ensconced with 19 6-pounders on the left front of the ridge, men of the 2/Rifle Brigade had been in a position with little cover to which, owing to the same error, they had been misdirected; they were now cut off in rear. By the time of this last and heaviest attack by the enemy the desert around their outpost (appropriately named Snipe) was littered with tanks destroyed by them in earlier attacks. The attack was made straight at them and they broke it too, having knocked out in the day some 60 or 70 tanks and self-propelled guns, of which at least 32 were irrecoverable.43

That night the 2/Rifle Brigade withdrew after a relieving battalion of the 133rd Lorried Infantry Brigade had also lost its way. A second battalion of that brigade, which was to take another locality, also dug in on the wrong site and was overrun next day. By repelling strong armoured assaults without even field artillery support, the 2/Rifle Brigade had demonstrated that if the infantry front were pushed firmly forward and protected by anti-tank artillery the German armour could not throw it back. The 1st Armoured Division, however, in its efforts to secure Kidney Ridge was repeating errors of earlier days by sending out battalions to hold localities with open flanks when an advance on a broad front was needed. The efforts failed tragically, and the enemy was still on Kidney Ridge at the end of the month.

South from Kidney Ridge the remaining centres of enemy resistance about the Oxalic line had been cleared up on the night of the 26th–27th by the Highland, New Zealand and South African divisions. Thus the bridgehead originally planned to be seized had been captured, and had been extended in the north; but the enemy maintained an unbroken front to the west and the direction of the Eighth Army’s attack had now been switched to the north.

On Rommel’s return the enemy’s defence had assumed the character of vigorous forlorn-hope attacks, which suited Montgomery who preferred the enemy to counterattack rather than await attack on his own ground. Rommel’s first morning at the front revealed the 1st Armoured Division concentrating near Kidney Ridge after

night attacks had been made there and at Trig 29, which he interpreted as efforts to advance northwards to the coast road. He therefore ordered the 21st Armoured Division and part of the Ariete to a position south of Tel el Aqqaqir ready to counterattack. Artillery from the southern sector was sent north. The 90th Light Division was ordered forward from Daba and, with the 361st Battle Group, was put into the line south of Sidi Abd el Rahman on the night 26th–27th October, with the 159th Battle Group west of Trig 29 and the 200th Battle Group between Ghazal and the coast.

The strong counter-attacks on the 27th had resulted from orders by Rommel for attacks by the 90th Light Division against Trig 29 from the north and by the 21st Armoured Division against Kidney Ridge from the south. Infantry drawn from the 15th Armoured Division and 164th Division were to assist. The attack at Trig 29 was made by the 155th Battle Group which advanced only to 500 yards west of that objective. The heavy British artillery fire halted the infantry and Rommel ordered that the troops should go over to the defensive on the ground then held. The 155th dug in to the north-west of Trig 29, while the 361st Regimental Group of the 90th Light Division took up a holding position astride the railway line southeast of Abd el Rahman.

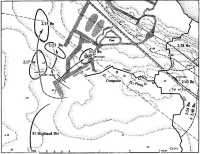

The policy, laid down by Montgomery on the 26th, of continuing the attack northwards towards the sea on the 27th and succeeding days, appears to have been originally embarked on as a crumbling operation with the general object of destroying the enemy in the salient by the coast, and not with the specific intent that the armour should debouch there. At that stage a break-out point does not appear to have been indicated, nor indeed had the planning evinced any haste to get ready for a chase. No immediate intention to break out along the coast road is suggested by the written orders nor by the narrative dealing with this stage in the 9th Division’s report:

With the Army Commander’s brief direction to “Attack North”, consideration was given to the staging of a further attack in this area on the night 27th–28th October. On the arrival of XXX Corps Operation Instruction No. 85 of 26th October, which ordered a policy of mopping up, and the completion of the capture of the final objective by all divisions on 27th October, it was decided to plan the further attack northwards on the night 28th–29th October – one night later.

In the plan submitted to the army commander by Morshead on the morning of the 26th, however, his intention had been to attack at once to seize and open up the main road from the enemy’s front-line westwards for three kilometres. Perhaps it was the contemplation of this plan that implanted the idea later tentatively adopted that the armour might next debouch along the coast road. A subsidiary object of Morshead’s plan was to secure the road and the area south of it for use by the division’s vehicles, thus shortening its long and exposed supply and evacuation routes.

The plan was an ambitious one. The task was to be accomplished in progressive phases and required the employment of all three brigades. For the operation the 23rd Armoured Brigade less two regiments was also placed under Morshead’s command and the artillery of the 51st, 2nd New Zealand and 10th Armoured Divisions and of three medium regiments was to be in support. Including the division’s own artillery there would be 360 guns.

In the first phase, the 20th Brigade was to secure the flanks of the northward advance. On the right the 2/13th Battalion was to advance

along the switch line and establish itself south of Thompson’s Post. On the left the 2/17th Battalion was to hold on to Trig 29 and the 2/15th to extend the western flank northwards by striking north from there. In the next phase, to be carried out by the 26th Brigade, the 2/23rd Battalion and 46th Royal Tank Regiment were to strike north-east from near Trig 29 to cut the main road about Kilo 113 and establish a firm base. Then the 2/48th was to advance eastwards alongside the road to attack in rear the enemy’s front line defences astride the road and capture them. The 2/24th would follow the 2/48th and capture Thompson’s Post from the north. Finally the 24th Brigade, as well as maintaining a firm base behind the original coast defences, was to capture the enemy’s outpost covering the main road in the Kilo 109 area and also the area north of the 2/48th’s breach, between the main road and the sea. For the attack the 2/3rd Field Company was to be in support of the 24th Brigade, 2/7th Field Company and 295th British Field Company in support of the 26th Brigade, and the 2/13th Field Company in support of the 20th Brigade.

Although the artillery provision was liberal, the guns were ill-sited to support the operations except those planned for the 2/13th Battalion (which were also to be supported by timed enfilade fire by the machine-guns of Macarthur-Onslow’s composite force). To support the northward advance the guns had to fire concentrations in enfilade; to support the attack eastwards, they had to fire in the face of the advancing infantry. For the latter phase the plan provided for timed concentrations about 200 yards deep receding ahead of the infantry.

Morshead. discussed his detailed orders with Leese on the morning of the 27th and had a further discussion on the operations with Montgomery in which he “stressed need for armour to support us on our left flank”. Morshead recorded in his diary that Montgomery agreed that these were the proper tactics but doubted whether the armour would manage it.

Morshead outlined his plan to his brigade commanders and others at a conference at 2 p.m. on the 27th. That afternoon Brigadier Windeyer resumed command of the 20th Brigade after an absence due to severe illness. Morshead’s final oral orders were given at a conference at 7 a.m. on the 28th and confirmed by a written operation order later in the morning. The attack was to be made on the night 28th–29th and the 20th Brigade, after its relief by the 152nd Highland Brigade, was to relieve the 26th so as to be in position to open the attack.

It may be readily assumed that on the 27th Alexander had discussed with Montgomery other matters than the future of the 9th Division, which may have had some bearing on developments on the 28th. So far all operations ordered and executed had been within the compass of the modified LIGHTFOOT plan expounded by Montgomery in his memorandum of 6th October:–

The task of 30 Corps and 13 Corps will be to undertake the methodical destruction of the enemy troops holding his forward positions.

30 Corps will walk northwards from the northern flank of the bridgehead, using 9th Australian Division, and southwards from the Miteiriya Ridge using the New Zealand, South African and 4th Indian Divisions. ...

I hope that the operations outlined ... will result in the destruction, by a crumbling process, of the whole of the enemy holding troops.

Having thus “eaten the guts” out of the enemy he will have no troops with which to hold a front. ... When we have succeeded in destroying the enemy holding troops, the eventual fate of the Panzer Army is certain – it will not be able to avoid destruction.

By the morning of the 28th, however, Montgomery had decided that a new break-out thrust would be made as soon as the 9th Division had completed its next “crumbling” phase. About 8 a.m. on the 28th Montgomery conferred with Leese and Lumsden and told them that he planned that the XXX Corps should then drive westwards along the axis of the road and railway to Sidi Abd el Rahman while the X Corps was to exploit westwards from the Australian left flank, holding off the enemy armour from XXX Corps. In brief, a break-out operation between Trig 29 and the sea was envisaged, and the front from Trig 29 southward was to go over to the defensive. It is remarkable that, if this break-out plan had been executed, the armour’s seaward flank would have been closed when it emerged and it could have manoeuvred in only one direction.

Before advancing along the road axis it would have been desirable if not essential, in order to provide a safeguard against enfilade fire from the hillocks near the sea, to capture first not only the road and railway to the north of the 9th Division and all ground south of the railway but also the whole area between the road and the sea. That indeed was the underlying and ultimate purpose of the next operation planned for the 9th Division, but the enemy defences between the road and the sea were not within the scope of the operation’s immediate objectives.

Later that morning Lumsden and Freyberg each had a long conference with Morshead, and Freyberg was subsequently warned by Montgomery that on completion of the Australian attack the New Zealand division should be ready to take over the sector and make an advance along the coast.

The relief of the 26th Brigade by the 20th Brigade on the night of the 27th–28th was made difficult by strong enemy counter-attacks on both the 2/24th and 2/48th Battalions at the time set for their reliefs and still more difficult by the late arrival of the 2/Camerons to relieve the 2/13th. The latter, which was to have proceeded across by foot, had to be fetched by transport waiting to take out the 2/24th, and was only just in time to complete the relief by dawn. The 2/17th on Trig 29 had previously been severely counter-attacked that morning and in the early afternoon but had driven the enemy off.

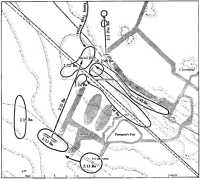

Both battalions of the 20th Brigade opened their attack at 10 p.m. on 28th October. The 2/13th on the right was a depleted unit, with rifle companies averaging only 35 of all ranks, and an exhausted one, after five sleepless nights. It had attacked on two successive nights, been counterattacked on the next two, and on the night preceding this attack had been on the move, arriving only just before dawn in an area overlooked and constantly shelled by the enemy. The troops crossed a start-line laid farther back than the plan provided but soon caught up with the barrage and had to pause until it lifted. The attack by the 2/24th on the 26th

October had cleared the enemy from the ground covered in the first phase except for some isolated survivors who offered no resistance, but the enemy, apparently aiming behind the shell-bursts of the British barrage, brought artillery fire down on the battalion transport and in the midst of the rear companies. The Fig Orchard, which was the first objective, was reached in 50 minutes. Captain Gillan’s company dug in close behind the orchard with battalion headquarters nearby. Soon Lieutenant Barrett’s44 company and Lieutenant Vincent’s passed through and continued down a track leading towards the coast. They took up position some 800 yards from Thompson’s Post, after having to move back about 50 yards because the protective artillery barrage was too close. Captain Burrell’s company then patrolled deeply ahead but without making contact.

With companies barely stronger than platoons, the battalion’s attack with two companies forward had inevitably been on a narrow frontage. The path taken missed enemy positions on the left flank, which now became troublesome, heavily mortaring battalion headquarters and Gillan’s company. Moreover the whole area was found to be strewn with anti-personnel mines. Casualties were mounting and it fell to Gillan’s company to deal with two enemy posts which were mainly responsible. The first patrol of 10 men under Lieutenant North45 met with disaster when a mortar bomb landed in its midst, killing or seriously wounding all except the commander. North returned and organised a second patrol to bring his men back. Colonel Colvin had meanwhile ordered Gillan to send out another patrol with firm orders to subdue the other post. Corporal McKellar, who was given the task, moved with ten others through a minefield, attacked with grenades two machine-gun crews giving covering fire to a mortar crew, and captured the guns and their crews. Next they rushed and overcame the mortar crew some 30 yards away and returned with their prisoners carrying the captured weapons. After one more post was silenced by patrol action it appeared that local opposition had at last been subdued. Meanwhile Burrell’s company had returned and dug in a short distance behind battalion headquarters.

On the left the 2/15th attacked northward from Trig 29. As the battalion was forming up it was heavily shelled and Colonel Magno and his adjutant were wounded, Magno mortally. Strange took command and led the battalion in a vigorous, well-executed attack. Advancing through machine-gun and mortar fire they encountered posts manned mainly by Italians 900 yards from the forming-up place, overcame them and secured their objectives. In the attack 89 Italians were killed and some 130 Italian and German prisoners were taken. No minefields were found and the vehicles had no difficulty in moving up. The battalion dug in. It had lost 6 killed, including Captain Jubb,46 a company commander, and 36 wounded; 3 men were missing. Soon after first light two enemy tractors

approached towing anti-tank guns. The guns and 22 Germans with them were promptly captured.

The fresh 2/23rd (Lieut-Colonel Evans) and the 46th Royal Tanks (Lieut-Colonel T. C. A. Clarke), who were to execute the advance to the main road, had trained together for semi-mobile operations. To gain surprise and save time Evans planned to advance to the objective with his assault troops (one company) mounted on the tanks and two companies following on his own carriers and those of the 2/24th. By the time the 20th Brigade attack began all were lined up ready at the forming-up place, there to await that brigade’s success signal. An alerted enemy was also ready. When the barrage opened and the advance started the tanks and carriers and the men mounted on them were exposed to sharp fire. Some of the tanks, not having the assistance of moonlight as broad as that laid on for the earlier attacks, missed the marked gaps in the home minefield and were immobilised. Others, according to the diarist of the 2/23rd, moved right and left contrary to instructions to search for others gaps and “an extremely confused situation” developed, into which the enemy pumped shot and shell from weapons of every kind. In the left company, in which casualties were severe and all the officers wounded, the company sergeant major, Warrant-Officer Joyce,47 rallied the survivors and led them forward without the tanks to overcome the foremost enemy positions in hand-to-hand fighting and take 40 prisoners; but elsewhere the attack did not progress.

It was decided to re-set the attack and the sappers were directed to widen the gaps, but much time was lost. “The difficulties of this period,” states the 9th Division’s report, “were added to by communications between the commanding officers of 2/23rd Battalion and 46th Royal Tanks breaking down and the headquarters of 26th Brigade and 23rd Armoured Brigade, which were situated close to each other, not being in touch.” So no doubt it appeared to the staff at divisional headquarters. Evans had lost touch because Clarke and most (if not all) of his squadron leaders had been wounded. Whitehead and Richards had gone forward together to keep closer touch.

After the gaps had been widened the advance was resumed until the tanks again reported mines Engineer sweeping operations were undertaken but failed to discover any. It was 12.55 a.m. before the tanks moved forward again, but then they came under fire from six 50-mm antitank guns, whereupon they dispersed taking their infantry with them. The enemy became very active and casualties mounted fast.

The operation was developing into the type of muddle for which there were several derisive epithets in common army parlance. Colonel Evans gathered what men he could – only 60 or 70 – and organised an attack which at 3.15, after a hard fight, took the main German position with its six guns and 160 men.48 About that time another group of infantry

and 15 tanks, who were out of touch with Evans, advanced east of Evans’ position towards the railway. After 800 yards they came under fire from German guns, including one 88-mm; nine tanks were knocked out and many of the infantrymen were hit. At 4 a.m. Evans reported that he was digging in about 1,000 yards forward of the original F.D.L’s because he had so few men and was not in touch with any responsible officer of the 46th RTR. The 2/23rd had suffered very severe losses in the attack, having lost 29 killed, 172 wounded and 6 missing. The casualties included 2 majors, 4 captains, and 10 lieutenants.

Meanwhile Brigadier Whitehead had made a new plan: to attack with the 2/24th and 2/48th Battalions from the area firmly held by the 2/15th. General Morshead made the 40th RTR available to him; but the 23rd Armoured Brigade could not at such short notice give a definite time for the 40th’s arrival at the forming-up place and it became apparent that the fresh battalions would probably have insufficient time to reorganise on their objectives before daylight. Morshead therefore postponed the attack and ordered Whitehead to ensure that the 2/23rd was securely established and made contact with the 2/13th on its right and 2/15th on its left: the 2/24th and 2/48th were to return to their lying-up areas. The few tanks of the 46th RTR still in running order – only eight – were withdrawn.

Dawn on the 29th found the 2/13th Battalion in an isolated, rather precarious position, with open left flank and a gap of 400 yards (protected, however, by an enemy-laid minefield) between the two left companies; opposite the gap were known enemy fortified posts, which might be still occupied. Behind the battalion there was an open flank for almost 1,000 yards.

From 7 a.m. onward heavy and accurate artillery fire fell on the battalion headquarters. Three shells penetrated the dug-outs; the third wounded and incapacitated Colonel Colvin, killed the adjutant, Lieutenant Pinkney,49 and wounded the anti-tank officer, Lieutenant Gould.50 Captain Jones, the command post officer, notified the catastrophe to Windeyer’s headquarters and the two forward companies through his radio links. The Intelligence officer (Lieutenant Maughan) who was the only officer left on the headquarters, asked brigade headquarters to find Major Daintree, the second-in-command, and in the meantime Captain Gillan had come across from his company to take charge. Major Daintree could not be found. Later it was ascertained that he had been wounded while organising the transport and evacuated. Thereupon Windeyer asked Morshead to make available Captain Kelly, a former adjutant of the unit, who was then serving on divisional headquarters. Morshead agreed and promoted Kelly to the rank of major. Kelly arrived in the afternoon and took command. Finding that the four rifle companies had between them only about 100 men, he reinforced them with men from “B” Echelon and

Dawn, 29th October

the Headquarters Company. Gillan later wrote: “To the dazed and battered troops, it was like a shot in the arm to see Major Joe back in the fold.”51