Appendix 4: Ordeal on New Britain

After the Japanese had driven Colonel Scanlan’s force from its positions near Rabaul on 23rd January 1942, two main lines of retreat developed. One led westward to the Keravat River, and thence to the north coast; the other south-east to the south coast. In both directions the country was mountainous, rugged, covered with dense growth, and intersected by deep ravines along which ran fast-flowing streams. The little food available in the jungle was largely of a kind which the men had not been trained to recognise.

No plans had been made for the situation which then arose. Orders such as “go bush”, “break up into small parties” and “every man for himself” which soon began to circulate implied a cessation of military organisation and control. As the troops withdrew they left their communication and supply routes, and along the tracks they were to traverse few stores of food, ammunition or medical supplies had been organised or established. For the moment the only course open to the men was to escape in mechanical transport down the roads to the south so far as the roads ran. Soon trucks and carriers were transporting troops to the rear and being subjected to bombing and machine-gunning from the air.

Lieutenant Selby, the anti-aircraft artillery officer of the force, later re-called one such journey.

We walked at a brisk pace, only taking cover when diving planes roared down on us. Eventually a truck dashed by, then pulled up in answer to our hail and we climbed aboard. At frequent intervals planes would dive on us, their machine-guns blazing, and we would leap off the track and take cover by the roadside. ...

At Toma ... we came to Rear Operational headquarters. I told the sergeant-major there that I wished to report to the Colonel. He went into the tent and returned, saying: “The Colonel’s orders are that each man is to fend for himself.” Less than a mile farther on the road petered out and the jungle began. A large portion of my battery was waiting for me by the roadside but a number had gone on with various groups of infantry. Along the road was a long string of abandoned vehicles, filled with rations, munitions and stores of all descriptions. The sight of the rations made me feel hungry and glancing at my watch I was surprised to see that it was just after midday. I could not leave that string of trucks to be picked up by the enemy intact and [we] set to work demolishing the trucks ... but left the food in case more troops should be coming through.

Meanwhile Captain Appel, in accordance with his final instructions from battalion headquarters to cover the withdrawal, remained in the Vunakanau area until mid-afternoon of 23rd January. Then, following the direction taken by Captain McInnes and others, he too moved off towards the Keravat, crossed the river and two miles farther on reached a bivouac area already selected by his second-in-command, Captain Cameron.1 There

he found about 160 men, mostly from his own and McInnes' companies but including some headquarters and anti-tank people. The Vulcan beach defenders under Captain Field, who had been ordered by Major Owen soon after 7 a.m. to withdraw to Four Ways, made slow progress through thick bush and by dusk had reached a position only half a mile from Four Ways . Next morning a native reported to Field that Four Ways and Vunakanau had been occupied, cutting off the road to Tobera. Skirting Four Ways, the party moved on through the jungle, avoiding the roads and eventually reaching the Keravat four days later. On the way other stragglers joined the party which on arrival numbered fifty-nine. After crossing the river the men moved on towards Keravat Farm, which they found to be occupied by Japanese . A civilian told Field that Japanese were moving in large numbers towards the Vudal River, south-west of Keravat . His move would necessarily continue in that direction. The men were very tired, some were sick, and all had been practically without food for four days. Field called them together . He told them that he himself had no intention of surrendering ; that those who wished to continue with him could

do so; the alternative was surrender. He gave them half an hour to make their decisions. Six elected to go on, the remainder to return to Keravat and surrender. They would remain in their present position until the after-noon, they said, to allow Field and his men to get clear. It was then 27th January. All told, the rations for the seven men amounted to one tin of bully beef, a cucumber and two and a half biscuits.

Meanwhile, on the 24th, Travers, who had bivouacked his company near Toma the previous night, was confronted with a situation similar to that which Field was to face when he reached the Keravat River. He knew nothing of the movements of the rest of the force, or of the order to withdraw, and decided that the injured and those who considered themselves unfit to attempt the formidable task of reaching either the north or south coasts on foot should surrender. With Lieutenant Donaldson he set off at 8 o’clock to reach an agreement with the Japanese. The two officers walked to Vunadadia, thence to Malabunga Junction, and after a two hours’ journey returned to Toma, having seen no sign of the enemy. Travers then advised those who were resolved to escape to split up into parties as they saw fit, allowing the direction they took to be influenced by their knowledge of the country they were to traverse. The majority of the men made their way to the south coast; but parties under Donaldson and Tolmer, amounting to about twenty men in all, eventually linked with other escapers on the north coast, the main group of whom had set out westwards from Keravat on the 24th.

Appel had organised the men into groups consisting of carrying parties with advance and rear-guards, and by 5 p.m. on the 26th had reached the Kamanakan Mission. There, realising the condition of his men and sensing a lowering of spirits, he held a muster parade totalling 285 all ranks and appealed to the men not to allow themselves to be captured. He said that he would establish camps in the hills where he would re-train them and make them fit to fight again. The men responded well to his appeal.

He sent forward Lieutenant Smith2 and Corporal Hamilton3 on horse-back to Lassul Bay, Sergeant Jane4 and Corporal Headlam5 to Massava, and appointed Captain Cameron his liaison officer. The force, divided into a headquarters and four groups commanded by Captains McInnes and McCallum,6 Lieutenant Bateman7 and Appel himself, was established at St Paul’s, Guntershohe, Lahn and Kamanakan. On 27th January Kam-anakan was shelled by Japanese naval craft; next day two large Japanese forces were landed at Massava and Lassul Bay. McInnes, who reached

Lassul on the 29th, saw landing craft loaded with Japanese coming ashore. He withdrew his men and soon afterwards met Captain Appel, who had arrived with a second group of escapers. McInnes, who believed that the Japanese were likely to advance on Lahn, advised his men to split up into small parties, to facilitate escape. The alternative was surrender. Appel, however, took his company, now numbering about 120, four miles beyond Lahn into the mountains where, in pouring rain, the men spent the night. Next morning he moved them to a village westwards of Lahn, where they sheltered in small huts.

There he was approached by an officer and some of the NCOs who declared they should give up because of the poor physical condition of the men, the lack of food and the adverse weather. Eventually, after a further conference in which McInnes participated, Appel (still uncon-vinced of the hopelessness of the situation) set off with a small party, including McInnes and three NCOs, for Lassul Bay. Before he left Appel ordered his men to follow in an hour’s time. He felt that it was imperative that the men should have comfortable conditions that night, but hoped that the Japanese had left Lassul Bay because he had seen transports and destroyers moving out to sea.

About two miles from Lassul the party took a wrong track which led through Guntershohe and took the party five miles out of its way. Appel was afraid lest the delay result in the rear party arriving first at Harvey’s Plantation :

I forced two kanakas to carry two packs and set off [said Appel later]. Captain McInnes ... said he would accompany me from Guntershohe. The distance was seven miles. We ran every part of the way which was flat or downhill. Captain McInnes knocked up and I reached Harvey’s approximately 12 minutes after the troops. We stopped at Harvey’s house, which is 2 miles from the beach, and kanakas said the Japanese had left during the afternoon. ...

Greatly relieved by this discovery, Appel now set about organising food supplies, establishing reconnaissance and standing patrols (finding in the process that some men had abandoned their arms). Within the next few days most of the men from McInnes’ dispersed group, who found themselves unable to penetrate the jungle, had been found and brought back to the Lassul Bay area. A headquarters was formed at Harvey’s, and the troops, then totalling 413, were dispersed along the 30 miles of coastline between Ataliklikun Bay and Cape Lambert in groups ranging from the smallest of four at Vunalama under Lieutenant Tolmer to the largest of 194 under Captain Appel at Lassul Bay.

Meanwhile McInnes and a party of seven men had moved to Langinoa Plantation, about three miles east of Cape Lambert. There they remained until 16th February, when they set off in a boat navigated by Mr J. McLean of the near-by Rangarere Plantation, who had taken the place of one of McInnes’ men, and to whom the pinnace belonged. Their course took them to the southern end of New Ireland, where they met Mr Kyle,8

formerly the assistant district officer at Namatanai, who was also a coast-watcher. A message was sent to Port Moresby requesting that a flying-boat be sent to pick them up, but none could be spared. There the party remained until 30th April, although the Japanese twice visited the area, when they shipped in a larger vessel and in May reached Port Moresby.

Captain Appel, a pharmacist by profession and on that account able to give considerable assistance to the many sick, remained in the Lassul Bay area where he continued to be an inspiring and energetic leader.

On 14th and 15th February Japanese forces landed again at Lassul and at Gavit, capturing about 160 men without resistance. At Lassul Appel was able to approach within 60 yards of the Japanese who were sharing a meal with their prisoners, whom they appeared to treat well.

My troops were smoking what must have been Japanese cigarettes [said Appel afterwards] ... were guarded by Japanese with fixed bayonets. Our troops were unarmed but their hands were not tied. At 1815 the Japs marched the men down to the beach, lit numerous small fires and slept on the beach all night.

I sent two of my men down to the beach and they observed that our troops were given breakfast in the morning. After breakfast the hands of our captive troops were tied behind their backs and they were put in a pinnace and taken out to a transport.

Afterwards the Japanese distributed messages9 in writing urging the Australians to surrender, and Appel, afraid lest his exhausted and ill-fed men be persuaded, covered over 100 miles in the next five days, riding, walking and swimming, visiting his scattered parties and urging them to hold out.

At midnight on 21st February Corporal Headlam rode into Appel’s camp with heartening news for the fugitives. An evacuation scheme had been prepared by the Assistant District Officer at Talasea, Mr McCarthy,10 and he was on his way to meet the party.

In January McCarthy had been pursuing the normal duties of a district officer at Talasea. On the 23rd he had been at Cape Gloucester cratering the airfield, and that day had seen numbers of Japanese aircraft heading for Rabaul. He hurried back to Talasea, and by the 30th had established his radio in the Kalingi area, some 90 miles to the west, at the western end of the island overlooking the Dampier Straits. On his way he had gathered up a number of civilians and established a base camp at Karai-ai. On the 28th he received a message from Commander Feldt,11 naval Intelligence officer at Moresby, ordering him to take his wireless to Toma, in the vicinity of Rabaul, and send news of Colonel Scanlan’s force, of which nothing had been heard since the invasion. A further message ordered

him to take possession of the Lakatoi (179 tons), believed then to be at Kapepa Island, east of the Willaumez Peninsula, and use it to evacuate the civilians.

McCarthy had at this time under his command two small pinnaces, the Lolobau and the Aussi, each about 5 tons. He loaded the civilians aboard them and set off for Kapepa, arriving there early in the morning of 1st February, but the Lakatoi had gone. Leaving the civilians to go to Salamaua in the Lolobau, McCarthy and Marsland,12 a local planter who had volunteered to accompany him, set out in the Aussi with a native crew and sixteen police boys intending to take his wireless to Toma. He was followed in an open boat by Douglas,13 another planter who had volunteered for the journey and was determined to assist, and a Chinese, Leong Chu.

At Open Bay natives informed them that the Japanese had occupied Pondo Plantation to the north, and that two destroyers had been seen in Powell Harbour. McCarthy thereupon crossed the bar at the mouth of the Toriu River and established a camp some seven miles upstream. Thence Marsland made a trip to Pondo and discovered that the Japanese had left the area, after machine-gunning it and blowing up the ships and small

boats in the harbour. On the 9th he met Captain Cameron, liaison officer to the force on the north coast. Cameron had with him a group of nine soldiers, armed and in good spirits, a teleradio, and a small pinnace. On the 11th, accompanied by Marsland and Lance-Corporal Tuddin14, Cameron met McCarthy near Toriu. By the 14th McCarthy’s teleradio was able to transmit, and about midday a message drafted and signed by Cameron was sent to Port Moresby outlining the engagement at Rabaul and telling of subsequent events so far as they were known. It was the first news from the area received by the outside world since the message dispatched by Figgis on the morning of 23rd January.

On 15th February Cameron received a wireless message from head-quarters at Port Moresby granting him permission, if guerrilla warfare seemed impossible, to proceed with his party to Salamaua. Cameron replied that he would do so.

Then occurred an unfortunate dispute between Cameron and McCarthy, both exceptionally determined men, which cannot fairly be disregarded since McCarthy later claimed that Cameron’s actions jeopardised his entire evacuation scheme. Briefly, McCarthy wished Cameron to cooperate with his pinnace in the evacuation scheme he had devised and which had been approved by Port Moresby. Cameron, who had already received instructions to proceed to Salamaua, agreed to cooperate provided approval was gained from Port Moresby and drafted a message seeking permission, which he handed to McCarthy for transmission. Later when an attempt was made to take over Cameron’s pinnace and teleradio, Cameron, pending a reply to his message to Port Moresby, refused to agree. What Cameron did not know was that although McCarthy had accepted his message he did not send it, and at no stage did he intend to do so. He felt, he declared later, that Cameron was overriding his authority even by questioning it.

On the 20th Cameron, having given McCarthy a pistol for Frank Holland,15 a local timber-getter who was going through to the south coast to look for Colonel Scanlan and rescue other survivors, set out for Salamaua and arrived there on 3rd March with his eleven men after a voyage lasting eleven days.

Meanwhile McCarthy, having despatched Holland on 20th February to the south coast, moved north from Pondo to Seragi where he met Sergeant Jane and Corporal Headlam, the two energetic and competent NCOs who had been reconnoitring the coast ahead of Appel’s main force. They were suffering from malaria, but took McCarthy to Langinoa where about thirty troops were found on the verge of starvation. They had eaten all available poultry and European food on the plantation but “had failed to recognise 50 hectares of bearing tapioca growing within 20 yards of them”, McCarthy recalled later.

At Langinoa Headlam offered to ride on ahead and warn Appel of the impending arrival of McCarthy. It will be recalled that he arrived at Lassul Bay and met Appel at midnight on the 21st. That night Appel, who had earlier received warnings that the Japanese would be returning to Lassul Bay on the following day to accept the surrender of the remainder of his men, moved them about four miles inland to Lahn. On the 22nd he met McCarthy on the Usavit River and after hearing his plan agreed to have at least 145 men at Pondo within seven days. A minority of the men did not wish to take part, and McCarthy issued orders through Appel that surrender would later mean court martial for “desertion to the enemy”. Eight sick and wounded men, not well enough to make the move, were left at a hospital established at St Paul’s under Major Akeroyd,16 who had volunteered to remain, and during the next five days groups of men began to arrive at Pondo, assisted by native carriers over the final stages of the march through the mountains.

It now became apparent that the one ship available to ferry the men, numbering nearly 200, gathered near Pondo, would be inadequate. McCarthy placed Lincoln Bell17 (another timber-getter) in charge of the Aussi and set Marsland and Tolmer, two sergeants (Beaumont18 and Hunt19), and a civilian, D’Arcy Hallam, to repair the small schooner Malahuka, which had been partially destroyed by the Japanese. After five days and nights of intensive work she was launched and the ferrying of the troops down the coast began.

After one trip to Lolobau Island the Malahuka broke down, but some-times on foot, at other times in canoes, and occasionally by pinnace, the red-headed and energetic McCarthy (aided in particular by Appel and Tohner) continued the movement westwards. At Walindi on 8th March he met Patrol Officer Harris20 who had arrived with a flotilla of schooners from Madang, and thereafter the movement continued apace. On 9th March Holland, who had been anxiously awaited by McCarthy, arrived at Open Bay from the south coast with a party of twenty-three, including Colonel Carr, after a two days’ journey from Ril across the mountainous Mukolkol country. By the 15th most of the troops had reached Walindi, more than fifty arriving from Valoka in twenty canoes which McCarthy had organised. By this time five wireless posts were operating and direct communication between all points in the evacuation scheme was constant.

From Walindi the fit men walked to Garua Mission and thence across the Willaumez Peninsula to Volupai Plantation. The sick were transported round the peninsula in the Gnair and thence to Iboki, about 60 miles to the west.

Other ships of the flotilla then assisted in bringing the remainder of the men from Volupai to Iboki, where food was plentiful and a hospital had been established under a tireless and devoted woman, Mrs Gladys H. Baker, a plantation owner of Vitu Islands who had refused to be evacuated with other women and children in December.21 At Iboki McCarthy learnt that the Lakatoi was at Vitu, and on 19th March sent a party of men under Marsland to arrest her. On the 20th, the Lakatoi’s master and mate having agreed to cooperate, the main body of the troops moved to Vitu. Next day, loaded with stores, water and fuel and carrying a total of 214,22 the Lakatoi set sail for Australia. The empty ships Totole and Umboi were returned to Madang and the Gnair, with W. Money23 as master, followed the Lakatoi in its passage down the Vitiaz Straits. On the 22nd the Lakatoi met the Laurabada at the eastern end of Papua, and, after receiving food and medical supplies, continued her voyage southwards. On the 28th the survivors were disembarked at Cairns.

Of all on board [recorded Feldt], six only were fit men ... the rest were sick, debilitated by poor and insufficient food ... weakened by malaria and exposure. Most had sores, the beginnings of tropical ulcers, covered by dirty bandages. Their faces were the dirty grey ... which betokens malaria; their clothes were in rags and stank of stale sweat. They were wrecks, but they were safe, and some would fight again.24

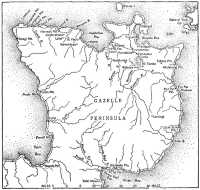

The main routes of withdrawal to the south coast were from the Malabunga and Toma roadheads across the Warangoi and Kavavas Rivers either to Lemingi at the foot of the Bainings, or to Put Put Harbour on the east coast of the Gazelle Peninsula. A number of tracks radiated from Lemingi to the south coast, but the principal ones led to Adler and Wide Bays. Both were ill-defined, rough and hard going. The route from Put Put followed the coast to Adler Bay.

The commander of the force, Colonel Scanlan, after issuing to Carr his orders for the withdrawal, had remained at Tomavatur for about an hour deliberating whether to attempt to reach the south coast or to surrender. Eventually, accompanied by five others, he set out for Malabunga and joined other assorted groups trudging along the track to Lemingi.

Some of the men who arrived at Malabunga during the afternoon of the 23rd January were advised to take three days’ rations from abandoned

trucks there and push on about five miles to a police barracks. By 5 p.m. about 200 who obeyed these instructions had gathered there. It was nearing dusk and about half the party decided to stop at the barracks until morning; the others to attempt to reach Lemingi Mission. One soldier25 who elected to go on described the trip:–

We walked along in line in pitch dark. Each had his hand on the man in front. If a man in front came to a log he’d say “log” and the word would go back along the line. I was the twentieth in the line at the beginning and by midnight I was last and dropped off. I pulled a groundsheet over me and slept in the rain. Next morning I followed the track and came up with the others in a village about 1700.

By the 25th advanced parties of the force had begun to arrive at Father Maierhofer’s mission at Lemingi, and the following day it was estimated that 300 officers and men were there. The missionary provided tea, rice and native foods, and the men slept at the station and in the neighbouring village.

Early on the 26th an advanced party under Captain Nicholls26 left Lemingi to push on over the mountains to the coast. That day and the next other parties followed. Soon after leaving Lemingi the track dropped away steeply for about 2,000 feet. It was muddy and slippery, and the men slid most of the way to the fast 30-yard-wide river below; after wading it, they followed all day a track which climbed steeply. There were few villages. The men, wet, muddy and weary, were strung out along the track and had to rest every hundred yards or so.

Soon they broke up into groups of about twelve men. As they entered the villages the natives disappeared, but the men found taro roots, and cooked them for food. Otherwise rations were meagre. Each day found them growing weaker through lack of food and the effort needed to climb ragged mountains and cross swift rivers.

Our hands, never dry, were cut and torn [recalled one soldier]. It was painful even to close them to grip the rough vines, and our bodies were bruised and stiff from innumerable falls.

The advanced party arrived at Adler Bay at 4 p.m. on the 27th. As they neared the coast they heard sounds of gun fire, and Lieutenant Best27 and Private Ross28 went ahead to reconnoitre. They returned with the news that civilians and Chinese, who were camped at Adler Bay, were flying a white flag and desired to surrender. At the bay Nicholls’ party met Colonel Field29 of the N.G.V.R., who told them it was no use going on and advised surrender. Nicholls’ men pulled down the white flag. During the 28th and 29th groups of men from Lemingi continued to arrive. A dressing

station was set up by members of the 2/10th Field Ambulance,30 where the men were able to obtain sticking plaster, mercurochrome and small quantities of quinine. Food was abundant and the men slept in huts in a large village.

Meanwhile other soldiers were advancing by the route through Put Put. One party was led by Major Owen, the resolute commander of the company on Vulcan Beach. He had withdrawn soon after 7.30 a.m. on the 23rd with Captain Silverman and the RAP, and eventually overtook some Japanese near Taliligap. In skirting them Owen became separated from the rest of his party and spent the night close to Vunakanau, which he found also to be occupied. On the 24th, near a church at the foot of Mount Varzin, he met Lomas’ platoon, which had been joined by Lieu-tenant Dawson, and was told that all resistance had ceased and the troops had been instructed to fend for themselves. Owen thereupon assumed leadership of the group, now amounting to thirty-six, and announced his intention of reaching the south coast.

On the 25th they met the acting Administrator (Major Page31) and three other administrative officials. Page warned them that he had already sent a note to the Japanese informing them of his location and asking to be picked up. He added that the soldiers would be foolish to stay in the area. Acting on this advice Owen pushed on to the Ralabang Plantation house, reaching it soon after dusk.

There we found three civilians [said Dawson later] who said they could not give us any food. I lifted a plate of scones off the table and said: “This will do for the time being.” Eventually they gave u8 enough food for one day, but said they could not give us more as they had more than 300 natives to feed and did not know how long it would be before they could get rice from the Japanese. The unreality of their outlook shocked us.

Thence on the 26th the party reached the Warangoi River, followed its course on foot and by rafts, and on the 28th reached Put Put. On the 31st they too reached Adler Bay where they found a considerable number of troops waiting to surrender.

Colonel Carr had set out on the 23rd with a small headquarters party for Malabunga where, about midday, he met a naval officer, Lieutenant MacKenzie,32 and some ratings. Native carriers detailed to carry MacKenzie’s wireless set onward from Malabunga had not arrived there and lest it fall into Japanese hands MacKenzie had ordered that it be destroyed. Its destruction removed any possibility of continued resistance under one command until a new wireless could be obtained, said Carr later.

That afternoon and next day the headquarters group, now amalgamated with MacKenzie’s naval party and numbering twenty-one in all, toiled along a rough jungle track until they reached a village 15 miles south of

Malabunga. They remained there for a week, sending back patrols to report the movements of the Japanese. From these Carr learnt that the enemy had not penetrated beyond the Warangoi River to the east, Malabunga Junction in the centre, and the Keravat River to the west, and that the Australians were pushing on in small parties on the main routes already described. On the 24th pamphlets33 had been dropped ordering them to surrender. On the 26th Major McLeod and Lieutenant Figgis joined the headquarters group, and some days later the move continued. On 1st February, at Lemingi, Father Maierhofer proved as helpful to Carr’s party as he had been to earlier arrivals. He estimated that nearly 400 men had passed through in the preceding week, among them, Carr learnt, being Colonel Scanlan.

The battalion headquarters party was now at the rear of a long and weary procession of men. On the morning of the 28th the withdrawal westwards from Adler Bay had begun. The coastal route lay along coral rocks, or through mangrove swamps; the men camped in deserted villages at night and mosquitoes made life a torment; little food was to be found. By midday on the 31st the advanced party reached Wide Bay, where they met four air force men who had rowed round the coast in a dinghy.34 Tol Plantation house, the men discovered, had already been visited by the Japanese. They had shot the cattle and taken the pigs and sheep, but had left untouched the furnished house, complete with bed linen. The weary men caught and killed a stray pig, made linen lap laps, bathed and shaved, and afterwards revelled in the luxury of a roast pork dinner.

By 1st February the escapers at Tol had grown, according to some estimates, to 200, and small fires tended by groups of men were burning throughout the area.

We told them to put out the fires, but they were too tired to worry [recalled one soldier]. They just didn’t care any more.

That morning a float-plane came over and some of the leaders, convinced that the signs of occupation would bring the Japanese, warned the men to leave the area. Many pushed on that day, among them Sergeant Smith’s35 party, which had been joined by seven members of “A” Company, and now totalled twenty in all. Best and Nicholls, after conferring with Private O’Neill,36 who had demonstrated outstanding qualities as a leader during the journey down the coast, left the following morning, accompanied

by twelve others. They met a party of five engineers under Captain Botham37 at the mouth of the Henry Reid River, crossed the three rivers which run into Henry Reid Bay and bivouacked for the night of 2nd February near Kalai Mission.

That day Major Owen, accompanied by Sergeant Morgan38 and Private Glynn,39 had set out from Adler Bay on a fast trip to Tol. Owen feared that food was being wasted and was determined to get ahead of the troops in order to organise the available supplies.40 During the day he passed about 150 troops going to Tol, and on his arrival that afternoon found about 100 already there. After learning that food was scarce at Tol but said to be plentiful at Kalai Mission, Owen decided to push on. He set out early next morning, having been joined by Majors Mollard and Palmer and Captain Goodman41 and a small body of troops. They were crossing the second river at 7 a.m. when five enemy landing craft, heavily laden with troops, appeared heading for Tol Plantation. As they neared the beach the Japanese began to shell and machine-gun the area. Other groups who had recently left Tol either heard or saw the arrival of the Japanese and hastened away.

On the 3rd there remained at Tol and at Waitavalo, about a mile north, some seventy men. Twenty-two elected to surrender and, carrying white flags to the Japanese on the beach, were taken prisoner. Others attempted to escape through the plantation areas into the bush but many were captured. The Japanese systematically combed the areas adjacent to Henry Reid Bay, and parties of prisoners unable to cross the rivers at their mouths42 except by boat were brought to the concentration point at the Tol native labour quarters. The troops were fed at midday and at night. The Japanese contributed some rice towards their evening meal and per-mitted the use of a fire to cook it. When night fell the men were imprisoned in a large hut. Fires were lit round it and tended by the Japanese through-out the night.

Early next morning the prisoners were assembled outside the hut and marched to Tol Plantation house. There two Australian officers who had headed the surrender party the previous morning were separated. A piece of cloth on which Japanese characters had been written was attached to the belt of each officer, and an attempt made to separate from the others the men who had comprised the surrender party. Of about forty

men who claimed this distinction twenty were separated and marched away.

When they had gone the remainder were lined up in fours, and their names, ranks and army numbers entered in a book. Paybooks, photographs, letters and personal items were collected and heaped together; the hands of the prisoners were tied behind their backs with cord and they were linked together in groups of nine or ten. The men rested for a while. Some of them were given water to drink and allowed to share Japanese cigarettes. Then, led by three Japanese and with each group separated from the other by soldiers carrying spades and fixed bayonets, the men moved off through the plantation. The parties soon divided, going in different directions into the long undergrowth.

I decided that this was a shooting party [said one survivor later] and that if one were to be shot one might as well be shot trying to escape as be “done in” in cold blood. I was fortunate in that the line I was in happened to be not roped together and that I was No. 2 in the line. ... In the beginning the procession made its own track through the cover crop and secondary growth which was springing up, but after a time emerged for a short distance upon the track proper through the plantation. It was here that an “S” bend in the path with secondary growth overgrown with cover crop presented an opportunity for me to escape and I availed myself of it. Turning the first bend of the “S”, I nipped out of the line and ducked down behind a bush on the other bend of the “S”. The chap next to me called “Lower, Sport”, and I accordingly crouched further into the scrub.43

A survivor from another party, Private Collins,44 was in a group of men linked together by cord. When his party halted in the plantation an officer drew his sword, cut the rope joining the first man to the others, and motioned him into the bush. A Japanese soldier followed with a fixed bayonet. Collins, last in the line, heard a man cry out, and saw the Japanese return wiping his bayonet. Others were cut away from the group and led into the bush. One man broke loose and tried to escape, but the officer hit him with his sword and then shot him. Clissold45 of the 2/10th Field Ambulance, who was wearing a Red Cross brassard, had it torn from his arm. When he asked if he could be shot, the officer, in Collins’ presence, complied.

Finally, only Collins and the officer remained. The latter took up a rifle and motioned Collins to walk. After a few paces he fired, hitting Collins in the shoulder and knocking him to the ground. Another shot hit him in the wrists and back. The Japanese departed. Collins lay still on the ground for a time, then finding that the last shot had severed the cord round his wrists and that his hands were free, got up and walked

away, passing the bodies of about six of his comrades lying still on the ground.46

Another survivor, Lance-Corporal Marshall,47 endured a similar ordeal. When the group he was with entered the undergrowth, each was unlinked from the line and taken into the bush with a Japanese soldier. When Marshall’s turn came he was stabbed from behind with a bayonet, receiving three wounds – in the back, the arm and side, and lower down on his side. He fell, and lay still, feigning death. Soon afterwards he heard cries, followed by rifle shots. He concluded that any man who moved was fired upon. After lying for a time on the ground, bleeding freely, he managed to release one of his hands. When dusk fell he arose, and saw three or four men lying on the ground. After a few days’ wandering in the bush he was picked up by a party of Australians, including Lieutenants Lomas and Dawson, who had themselves narrowly escaped capture.

Marshall ... attempted to run away (wrote Dawson afterwards). He was delirious, walking along with an empty tin in one hand, the other tucked in his shirt front, which was full of blood. He had used the tin for drinking river water. We caught him, and learned the story of the massacre of Tol.

Other survivors spoke of subsequent killings on that grim day. Gunner Hazelgrove48 was one of a party of six who had entered Tol Plantation, unaware of the presence of the Japanese, soon after the first massacre, and had been surprised and captured. They were taken to a house near the beach where the party met an interpreter with the Japanese, dressed in shirt and shorts, who appeared to be English. As they arrived the interpreter said “All right boys, you can put your hands down now.” He spoke like an Australian, said Hazelgrove, later. At the Tol Plantation house Hazelgrove saw a large pile of equipment. Identity discs and personal belongings were taken from his party. Their hands also were tied behind their backs, and they were roped together. After marching them through kunai grass for about a quarter of a mile the Japanese, without warning, fired. Hazelgrove was hit in the back, fell, and lay very still. The Japanese threw palms over them and left. After struggling for two hours Hazelgrove freed his wrists from the bonds, and got up. Around him his five comrades lay dead. Somehow he struggled to the beach, where in a confused state he remained for two days before a party of artillerymen under Lieutenant Selby picked him up and cared for him.

Private Cook,49 of the 2/10th Field Ambulance, survived another such execution. About 9.30 on the 4th he and a group of seven others had been walking along the track towards Tol when they met an NCO of

the 2/ 22nd Battalion, who told them that he believed the Japanese had left Tol, but to remain where they were until he made certain.

We waited just off the track, four of us, having a game of cards and the other four cooking some food (said Cook later). Our first intimation that the Japs were there was when the four who were cooking ran past us, muttering “The Japs are on us.” We were at the edge of the jungle. I myself ran into the jungle and hid. I saw my seven mates walk out with their hands up so I went back with them. It was roughly about 1030 hours. We were taken to the main track under a party of Japanese, in charge of whom was a sergeant.

Soon other small parties of Japanese arrived with more prisoners, until the group totalled twenty-five. At Tol the Japanese separated a civilian police officer from them, they were tied together, and made to sit down in the plantation. The ambulance men protested that they belonged to the Red Cross, but the brassards they were wearing were torn from their sleeves. The Australians were then taken away in twos and threes. Cook was in the second last group of three. In sign language they were asked whether they would prefer to be bayoneted or shot. They asked to be shot. As they reached the bottom of the track, three other Japanese with fixed bayonets intercepted and fell in behind them:

They then stabbed us in the back with their bayonets (Cook related). The first blow knocked the three of us to the ground. Our thumbs were tied behind our backs and native lap laps were used to connect us together through our arms. They stood above us and stabbed us several more times. I received five stabs. I pretended death and held my breath.

The Japanese then walked away. The soldier who was lying next to me groaned. One Japanese came back and stabbed him again. I could not hold my breath any longer, and when I breathed he heard it and stabbed me another six times. The last thrust went through my ear, face and into my mouth, severing an artery which caused the blood to gush out of my mouth. He then placed coconut fronds and vines over the three of us. I lay there and heard the last two men being shot.

After an hour Cook was able to rise. He untied the cloth which connected him to his mates, and staggered towards the sea, about 50 yards away. After a few steps he again collapsed. Eventually he regained consciousness, reached the beach and, the instinct for self-preservation strong even in that weakened state, walked along it in the water to avoid leaving traces of blood. At dusk he saw the smoke of a near-by camp fire and stumbled towards it. Next morning he found a small party of soldiers under Colonel Scanlan camped close to where he had spent the night. Scanlan dressed his wounds while Cook told his story.50

Another survivor, Private Webster,51 was among eleven men who reached Tol on 3rd February. Next morning they were surprised and captured by a Japanese patrol. They were marched to Waitavalo House, tied, lined up in the bush and fired upon. Hit in the arm and side Webster fainted.

When he recovered the Japanese had gone. Only one of his comrades, Private Walkley,52 remained alive. After hiding near the plantation for three days, the two men set off for help. Webster, who was ahead, missed Walkley and searched for him without success. Eventually Webster too met Colonel Scanlan’s party.

In a summary of these events and after interrogating all the available survivors and independent witnesses who had passed through the area, a Court of Inquiry reported in May 1942 its conclusion that

there were at least four 8eparate massacres of prisoners on the morning of 4th February, the first of about 100, the second of 6, the third of 24 and the fourth of about 11. These figures are only approximate.53 Witnesses were pressed by the Court as to whether they could suggest any explanation as to the cause of the Japanese action, but none of them can advance any explanation of the Japanese onslaught upon them, and none saw anything which might have provoked it. All the men had surrendered or been captured and held in captivity for some time before being slaughtered.

The Court accepts as absolutely reliable the evidence of the above men. Each of them appeared truthful and had a clear recollection of the event8 he was describing. This conclusion is supported by the fact that each of the five wounded men bore wounds consistent with his account, and Robinson’s hands were tied when he was picked up.

The Court considers that their evidence is further supported by the fact that each of the six was subsequently picked up, quite independently, by other parties and gave an account of his experiences agreeing with his present testimony. It is in the highest degree improbable that such an account could, in the circumstances, have been concocted.

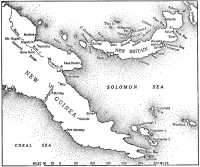

After the massacre the movement westwards continued. Two small parties got ahead of the main group. One comprising seven men under Corporal Hamill,54 which passed through Tol on 2nd February, had by the 15th reached Awul, 50 miles east of Gasmata. There from a missionary, Father Culhane, they learned that Gasmata was in Japanese hands, and went into the mountains, emerging five miles west of it. Using native canoes they reached Pilelo, an island off the New Britain coast near Arawe, and on 2nd March left in a missionary’s pinnace for Finschhafen.

The party under Nicholls and Botham reached Wunung on 10th February. Thence Lieutenant Best set out in a pinnace with eight men, but his party was captured at Gasmata. By the 13th Nicholls and Botham reached Father Culhane’s mission at Awul and, having secured a pinnace, sent back a message to Rano (where some of the men had remained) asking for a volunteer to steer it. One man who had been a seaman – said

he would not risk the journey, but Private Frazer, who had sailed on Sydney Harbour, offered his services.

They said only one man (Frazer related) but O’Neill said he was going too. We got tins of meat and goldfish55 and a canoe. Three miles out in the bay two Zeros shot us up. We put into shore and left the canoe. O’Neill was now delirious from the sun. I dragged him to a village and got two natives to carry him. At Father Culhane’s we found some “A” Company boys sick, and the rest half a mile farther on. Father Culhane said the Japanese had captured Gasmata and we would not get past.

He (Father Culhane) had a 20-foot pinnace, old, with a diesel engine capable of 4 knots and mast on which we rigged a sail. We got a compass off a schooner which had been wrecked on the reef. Father Culhane put O’Neill to bed with a temperature of 105. We took a 44-gallon drum of water, two 44-gallon drums of dieseline and two kerosene tins of cooked rice. I was to steer and sail the boat and Sergeant Elton56 was to look after the engines. The idea was to make for the Trobriands due south at dusk. We’d painted the boat black with pitch and set off at dusk twenty-five days after the landing.

200 yards out someone trod on the feed pipe and it broke. It took an hour to change and we had to row to keep off the reef. Two men wanted to go back, but O’Neill stood up, swaying with fever, and said he’d shoot anyone who wanted to do so. Three miles out a hot cap on the motor burst. It took an hour to put on a spare. These were the only spares we had.

Five miles out we ran into weather in the dark. To steer south meant being side on and we were shipping waves. So we steered south-east for one hour and south-west for an hour. In four days we hit the Trobriands. At one stage it rained for half a day. We saw no aircraft or boats. Most were seasick; only Elton and I were not. They lay helpless, unable to eat rice. We’d given up hope on the fourth day when a boy said he saw land. It took only two hours to reach it. We passed the first island, and sailed on looking for a mission. We passed another two islands and turned right through more islands and came to a channel marked by a post. We’d come along the only possible channel all the way from Rabaul with a map from an atlas as our only guide.

On the 20th February, Nicholls’ party of eleven were joined in the Trobriands by a group of civilian escapers. On the 24th they reached Samarai; three days later they were flown to Port Moresby where they gave details of the retreat down the south coast of New Britain and asked that help be sent.

Among the troops who passed through Tol after the massacre was Colonel Scanlan, who as related had met some of the survivors, including Privates Cook and Webster, soon after the event. Two messages57 had been left at Waitavalo, one addressed to Colonel Scanlan, urging him to surrender and “beg mercy” for his troops.

On the evening of the 8th Scanlan reached Kalai Mission, where a number of troops were gathered under Major Owen. A Mission priest told Scanlan that he knew of no scheme for rescuing the men and if they proceeded farther westward they would run short of food. In his opinion there was no alternative but to return to Rabaul and surrender.

The disorderly withdrawal of his force from Rabaul, the events at Tol, and the implications of the sentence “surrender yourself and beg mercy for your troops” must have weighed heavily upon Scanlan. Unaware how events were shaping elsewhere or of any attempt or plan to rescue the survivors, and in the light of the Japanese message, Scanlan decided his duty was to surrender. He told Major Mollard his reasons and asked him to address the men. That night Mollard gathered the troops together, told them that he had decided to return with Colonel Scanlan, and gave them his reasons.58 His speech “through its sheer hard logic depressed me more than anything which had happened on the track”, wrote Lieutenant Selby later.

After the departure of Scanlan and Mollard on the 10th, Owen, as senior officer on the south coast, took command. That day he began the movement westwards from Kalai, travelling with a party of twenty-three including the medical officer (Major Palmer) and three of the survivors from Tol – Hazelgrove, Marshall and Webster. The party reached Draak on the 17th, and were joined there by a further survivor of the massacre – Private Cook. By the 23rd the men were at the Malmal Mission at Jacquinot Bay, where they were generously helped by Father Harris. (It was his pinnace that Best and his party had taken on their voyage to Gasmata.) When Owen learned that the Japanese had occupied Gasmata, he decided that it was useless to continue the move westward. Camps were established at Wunung and Drina plantations for about 50 and 100 troops respectively. Several of the men had died on the march from Tol, and others were extremely ill.

As it seemed likely that the wait on the south coast would be long, and to keep the men occupied, Owen set them to work planting vegetables. Before long, however, sickness had depleted the workers until they seldom exceeded 10 per cent of the camp strength. In a medical report on the condition of the troops at this time, Major Palmer wrote that

100 per cent of the men have been inflicted with malaria and have had at least one recurrence; 90 per cent have had two or more recurrences, 10 per cent have daily rigours or sweating at night, 33 per cent only are able to do any sort of work. At least 15 per cent of the men are suffering from such a degree of secondary anaemia and debility following attacks of malaria, diarrhoea and the privations of the journey and lack of food that it will not be possible to keep them alive more than a few weeks.

On 5th April, however, a party sent out by Owen returned from Awul with a supply of stores and trade goods; that day Owen received welcome orders to concentrate his men at Wunung for evacuation.

How had this come about? On 7th February, leaving Figgis and MacKenzie to go by the direct route to Wide Bay, Carr and the bulk of his party had left Lemingi for the south coast. On the 14th, they met Scanlan and Mollard returning to surrender. On the 26th they overtook Figgis and MacKenzie at Ewei, where they were repairing a 12-foot dinghy. At Ril on 4th March Carr learnt from warrant-officers of the New Guinea constabulary of the evacuation scheme being organised on the north coast. A few days later, led by Frank Holland, Carr’s party, now accompanied by Collins and Robinson, two survivors of the Tol massacre, set off for McCarthy’s rendezvous. They took with them a message drafted by MacKenzie to be sent on McCarthy’s teleradio to the Naval Office, Port Moresby, stating that he and Figgis would endeavour to concentrate the remaining men on the south coast at Palmalmal, and there each Wednesday and Saturday afternoon would keep watch for aircraft and for any instructions that might be dropped to the force.

It was in response to this message that Lieutenant Timperly59 of Angau, taking a teleradio with him, had slipped across from the Trobriands to Palmalmal in a fast launch, arriving on 5th April. At midday Major Owen received a message from Captain Goodman to concentrate his men at Wunung. “They must be here today, as tonight is the night,” the message warned.

Then began a harrowing forced march for the men at Drina. Some were able to make only slow progress, supported at each side by their comrades; others were so weak they had to be carried on improvised stretchers. It was after midnight when the weary, over-wrought men arrived at Palmalmal, to discover that so far only Timperly’s pinnace had arrived. By the 9th over 150 soldiers and civilians had gathered at the evacuation point. That morning the Laurabada arrived, captained by Lieutenant Ivan Champion.60 She lay concealed during the daylight and at dusk the troops filed aboard. On the 12th the Laurabada reached Port Moresby, whence the survivors were shipped in the Macdhui to Townsville!61

One small party which could not reach the evacuation point in time to catch the Laurabada was brought out under the leadership of the former radio superintendent at Rabaul, Mr Laws,62 in a salvaged launch more than a month later. The party landed at Sio, whence the men wallced by way of Bogadjim to Bena Bena, and were flown to Moresby.

Another group of nine led by Lieutenant Dawson, having learnt from Lieutenant Figgis of McCarthy’s scheme on the north coast, followed the route taken by Colonel Carr, but arrived too late to be evacuated in the Lakatoi. They were led by friendly natives to Mavelo Plantation, and thence by canoe reached Valoka Mission at Cape Hoskins. At the end of March Dawson at Garua, following the route of earlier escapers, met Lincoln Bell, who had remained in New Britain after McCarthy’s departure, and through him sent a message to Port Moresby, giving the names of his men. On 14th May, after periods spent at Iboki and in the Vitu Group, the party was picked up at Bali Harbour by Lieutenant Harris in the schooner Umboi. On the 16th they reached Bogadjim and met Lieutenant Boyan63 of Angau. He led them to Kainantu in the Upper Ramu. There they were joined by several other Australians and learnt that they must go to Bena Bena for evacuation. At Bena Bena the weary Australians were told that only Americans (survivors of a Mitchell bomber which had made a forced landing in the area) were to be flown out; they must walk by way of Wau to the south coast, where they would be picked up by small ships.64 They reached Wau on foot on 15th July and were ordered to walk thence over the Ekuti Range to Bulldog and down the Lakekamu River to the south coast of New Guinea. Dawson protested and eventually all except Dawson himself were evacuated from Wau by air. Dawson’s odyssey had not ended. He remained with the 2/5th Independent Company until the end of September, when, suffering from dysentery, he walked over the Ekuti Range along a track which climbed to about 8,500 feet through moss forest until at length he reached the mouth of the Lakekamu; there he was picked up by a small vessel and taken to Port Moresby. (In 1945 he was back on New Britain as a battalion commander.)

–:–

The strength of Colonel Scanlan’s force at Rabaul on 23rd January was 1,396. Of these this narrative has recorded the escape of over 400, either by their own enterprise or with the guidance and help of those members of a force soon to become known as ANGAU. In addition some 60 civilians and four members of the R.A.N. were embarked either on the Lakatoi or the Laurabada, and about 120 members of the air force were taken off in flying-boats on 23rd and 24th January – an indication of what might have been done had an organised withdrawal and evacuation

scheme been planned before the invasion. About 800 became prisoners.65

Also remaining on New Britain and New Ireland were some 300 civilians. Most of the women and children had been evacuated between mid-December and early January. What opportunities had there been to evacuate the remaining civilians? On 16th January, the Acting Administrator at Rabaul, having learnt that a Japanese invasion was believed imminent, sent an urgent radiogram to the Commonwealth Government asking for action to evacuate the civil population. On the 21st the Prime Minister’s Department in Canberra replied asking the Administration at Lae to supply the numbers and the whereabouts of unessential civilians so that the question could be considered. It was then too late. Attempts by the Administration at Lae to gain wireless touch with Rabaul on the 22nd failed; Rabaul had been attacked that morning, and the Herstein in which Page hoped all civilians might be embarked lay burning in the harbour.

It is doubtful whether, even if granted opportunity to escape at this last moment, all the civilians would have chosen to go. Many of them had spent their lives hewing out plantations from the jungle and were reluctant to abandon their life’s work; others no doubt were swayed by responsibilities to their native labourers; a percentage under-estimated the consequences of remaining or over-estimated the dangers of travelling in small craft (some of which had left Rabaul as late as the day before the invasion) over long distances exposed to air attack; some were elderly and could not have faced the hardships entailed in escaping; some of the administrative officials considered it their duty to remain at their posts.

After the invasion most of the civilians were gathered in the vicinity of Rabaul where a camp was established by the Japanese for civil and military prisoners at Malaguna road.66 On 22nd June, 849 military prisoners, and about 200 civilians were embarked at Rabaul on the Montevideo Maru. On 1st July the Montevideo Maru was torpedoed and sunk by an American submarine off Luzon in the South China Sea. All the prisoners were lost, including a large number of the men responsible for the development of the territory in the two previous decades. In the first week of July the officers and nurses of Scanlan’s force were also shipped from Rabaul “in a dirty old freighter packed in a hold”, related one nurse. “We were all mixed together and spent nine days sweating and starving before we reached Japan.”67