Chapter 3: Plans and Preparations

While the destination of the 7th Division was being decided, the 8th was being formed and trained. It was to include the 22nd, 23rd and 24th Infantry Brigades, and a proportionate number of corps troops was to be raised, bringing the total to approximately 20,000 all ranks. Major-General Sturdee1 took command of the division on the 1st August 1940.

Although a corps and two divisional staffs had been formed for the AIF, it was still possible to find a highly-qualified staff for the 8th Division. Colonel Rourke,2 who was transferred from the corps staff to the 8th Division as senior staff officer, had been a young artillery major in the old AIF. He later passed through the Staff College at Quetta, India, and instructed at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, and at the command staff school established in Sydney in 1938. The senior administrative officer, Colonel Broadbent, a Duntroon graduate and a Gallipoli veteran, as mentioned earlier had been attached to the British Embassy in Tokyo from 1919 to 1922, and was in charge of the Australian Food Relief Mission to Japan after the Japanese earthquake in 1923. He was one of very few Australian regular officers with experience of East Asia. In 1926 Broadbent had retired and become a grazier. Also on the staff were two citizen soldiers who had served as young officers in 1914-1918, and had won distinction then and in civil life – Major Kent Hughes,3 then a Member of the Legislative Assembly in Victoria and a former Minister, and Major Whitfield,4 a Sydney businessman.

The artillery commander was Brigadier Callaghan,5 also of Sydney, who in the 1914-1918 war had won his way to command of a field artillery brigade. This was followed by continuous service in the militia, including command of the 8th Infantry Brigade from 1934 to 1938. The senior engineer, Lieut-Colonel Scriven,6 who had designed the re-fortification

of Sydney in 1934, and the senior signals officer, Lieut-Colonel Thyer,7 were regulars; Lieut-Colonel Byrne,8 who commanded the Army Service Corps, Colonel Derham,9 the medical services, and Lieut-Colonel Stahle,10 the senior ordnance officer, were citizen soldiers, the two latter having held commissions in the old AIF.

The headquarters of the new division had been temporarily established on 4th July at Victoria Barracks, Sydney, and on 1st August were transferred to Rosebery Racecourse. The 22nd Brigade, raised in New South Wales, and the 23rd, raised in Victoria and Tasmania, were concentrated in the two bigger States; the 24th, drawn from Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia, assembled in Queensland.

Brigadier Taylor,11 who had been training the 5th Brigade of the militia, was chosen to command the 22nd Brigade. He had gained a commission in the militia in 1913 and, during the war of 1914-1918, served with distinction in France as an infantry officer. After returning to Australia he resumed militia service and, in 1939, when he was given the 5th Militia Brigade, had successively commanded the Sydney University Regiment, the 18th Battalion, the New South Wales Scottish Regiment, and the 56th Battalion. In civil life the quality of his mind was evident in his having become a Doctor of Science in 1925. He had become Deputy Government Analyst of New South Wales in 1934.

As his brigade major, Taylor obtained Major Dawkins,12 a regular who had become brigade major of the 5th Infantry Brigade in the 2nd Division. Taylor sought officers with last-war experience to lead his battalions, young militia officers as seconds-in-command, and a sprinkling of veterans among his NCOs and men, particularly for the steadying effect they were likely to have in the first action which the brigade or any part of it would have to face. Varley,13 who was given command of the 2/18th Battalion, Maxwell14 (2/19th) and Jeater15 (2/20th) all reflected his requirements.

Varley, an Inverell grazier, with keen blue eyes and a sparsely-built frame which accentuated his military bearing, had returned as a captain,

aged 25, from the 1914-1918 war. He did not seek appointment in the militia until after the Munich crisis of 1938, but for the nine months before joining the AIF he commanded the 35th Battalion. Maxwell, six feet three inches in height, was the shorter of two sons of a Tasmanian bank manager. Both had given distinguished service in 1914-1918 when they were affectionately known as “Big”16 and “Little” Maxwell. They served as troopers in the light horse on Gallipoli, and later were commissioned in the infantry. In France, each was decorated for his exploits at Mouquet Farm. After his return to Australia Duncan Maxwell graduated in medicine at Sydney University, and went into private practice at Cootamundra. In August 1939, despite some misgivings arising from the contrast between the duties of a doctor and of a combatant, he returned to the infantry as second-in-command of the 56th Battalion, which had been newly raised in the Riverina. Three months later he became its commander. Although his infantry service between the wars had been so brief, his service in 1914-1918 and his personality underlay his selection to command of the 2/19th. Jeater, an architectural draftsman of Newcastle, had enlisted in the AIF in August 1915, and gained a commission in the course of that war. In 1926 he obtained an appointment in the militia, and for three years from 1937 commanded a battalion.

Each commanding officer was allowed to enlist men from his own and adjoining militia districts, and naturally brought in a regional following. As an instance the 2/19th, although it included some men from as far afield as New Guinea, was

to all intents and purposes a Riverina battalion. You could see it in the way they walked, the way they talked, and in the squint of their eyes. Pitt Street and Bondi Beach were foreign to them. Their hunting grounds were at Gundagai, Leeton, Griffith, Wagga, Narrandera and Lockhart. They told the yarns bushmen tell; about sheep and drovers and cocky farmers. ... The Colonel’s batman, “Young” Jimmy Larkin, had a milk round ... [in Wagga] and had been a prisoner of the Bulgarians in the last war. The New Guinea men ... clung together. Their stories were about Rabaul and Salamaua and Samarai. They talked about copra and gold and Burns Philp and Carpenters.17

In choosing their senior officers, the battalion commanders looked for those who had been in militia units, and consequently knew where to find good NCOs. The officers chosen were told, however, that they must select not more than three-quarters of the NCOs they needed; the remainder were to be selected after the main body of the brigade was in camp. “As you mould your men, so will your battalion be,” Varley told his officers at the commencement of their classes. “Inculcate into them your finest ideals. Teach them the principles of team-work and good fellowship as opposed to individual effort and selfish disregard for the comrades with whom they are going to live, train and fight.”

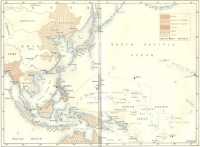

The Far Eastern Theatre, September 1938

The officers and NCOs of 22nd Brigade first went into training on the 15th July, at Wallgrove camp, among undulating country some 25 miles from Sydney, and just south of the main road to the Blue Mountains. Drafts of recruits began to stream in from such centres as Tam-worth, Newcastle, Wagga, Goulburn, and Liverpool and from “day-boy” centres in the metropolitan area where they had been receiving part-time training.

At Wallgrove and at Ingleburn, to which the brigade moved on the 20th August, the men rubbed shoulders, sizing each other up, settling into army routine. Those who needed the lesson soon learned to live simply and resourcefully. The “bull-ring” method familiar to the former AIF was used for training; tactical exercises developed skill and initiative; band instruments were acquired; amenities were established; groups of individuals were welded into units. These in turn merged into the whole as the scope of training extended, and the life of the brigade got into full swing.

The training of the other brigades was of course similar in most respects; the 23rd at “Rokeby”, near Seymour in Victoria and then Bonegilla, south of Albury on the Murray River; and the 24th (destined not to remain part of the 8th Division) at Grovelly, and later Enoggera in Queensland. The 23rd Brigade came into being on 1st July when its headquarters were temporarily established at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne; on 15th July Brigadier Lind,18 who had been appointed its commander, arrived at “Rokeby” with Major Sheehan19 as his brigade major. Brigade drafts came in the same day. Lind, like Maxwell, was a doctor. His first war service had been in the medical corps, ending with command of a field ambulance. In his student days at Melbourne University, however, he had been a subaltern in the citizen forces, and in 1919 he was appointed to command the Melbourne University Rifles. Since 1934 this enthusiastic doctor-soldier had led the 4th Infantry Brigade.

Lieut-Colonel Roach,20 commander of Lind’s 2/21st Battalion, was a Melbourne businessman and a devoted militia officer with varied military experience. After service on Gallipoli and in France, where he became a captain in the 5th Battalion in 1917, he joined the Indian Army, as did a good many other Australians. He saw active service in Persia and Afghanistan, retired in 1920 on medical grounds, and returned to Melbourne. There, since November 1939, he had commanded a militia battalion. Carr,21 of the 2/22nd, had received his commission in the militia

in 1921, and gained command of a battalion in 1938. Lieut-Colonel Youl22 (2/40th), a grazier, had become a major in the Royal Field Artillery23 in the 1914-1918 war; he then joined the militia, and gained command of one of the two Tasmanian battalions.

On 13th August a heavy blow had fallen on Australia’s leadership; the Chief of the General Staff (Sir Brudenell White), the Minister for the Army (Mr Street) and two other Ministers (Sir Henry Gullett and Mr Fairbairn) were all killed when the aircraft in which they were flying crashed near Canberra. In the consequent reorganisation, General Sturdee succeeded White. Sturdee had high qualifications for his new post. He had served as a captain and major of engineers on Gallipoli in 1915 and in France in 1916, commanded a pioneer battalion in 1917, and in 1918 served as a lieut-colonel on Haig’s staff. Between the wars he had served for a total of nearly six years in England or India, and had been the third Australian soldier to attend the Imperial Defence College. He had been a director at Army Headquarters, first of Military Operations and then Staff Duties, during the seven years before the outbreak of war. His eventual appointment as Chief of the General Staff had long seemed inevitable, but the events of 1940 brought it rather sooner than might have been expected.

A challenging figure stepped into the history of the 8th Division on 24th September, when Major-General Gordon Bennett24 was appointed its commander, in General Sturdee’s stead. Bennett had been born at Balwyn, a suburb of Melbourne, in 1887, and at the beginning of his business career was a member of the staff of a leading Australian insurance company. At the age of 21 he was commissioned in the Australian Infantry Regiment, gained a captaincy in less than three years, and at 25, soon after the introduction of compulsory instead of voluntary military training in Australia, became a major with the 64th (City of Melbourne) Infantry. His overseas service commenced in 1914, as second-in-command of the 6th Battalion of the 2nd Brigade, AIF.

Bennett established a reputation for personal courage and forceful leadership under fire from the first day at Gallipoli. For example, in the famous though ill-fated advance to Pine Ridge, when his men realised that plans had miscarried, he characteristically rejected the suggestion that they should retire, and led an advance to a position where a party of enemy troops came into sight, in front of Turkish guns. Bennett stood to direct his men’s fire, opened a map, and was shot in the wrist and shoulder. Although, when he went to the rear to have his wounds dressed, he was sent to a hospital ship, he was absent without leave from the ship next day, and back in the front-line. Ten days later Bennett led the

6th Battalion in a final attempt by Anglo-French forces to capture the peak of Achi Baba.

We advanced over open country in artillery formation, almost as though we were on a parade ground, and eventually deployed and advanced to what was known as the “Tommies Trench” (wrote a member of the 6th). ... I remember that Major Bennett was continually exposed to Turkish machine-gun fire on the dangerous side of a creek whilst he directed and encouraged the advance of the battalion. Later, when we made our rush forward from the Tommies Trench, again with an utter disregard of danger, and with practically every officer in the battalion a casualty, he directed a further advance in the face of extremely heavy fire.25

When the brigade was relieved from the line, Bennett alone remained of the original officers with the battalion, and succeeded to its command. In 1916, at the age of 29, he was appointed to command the 3rd Brigade; and thus became probably the youngest brigadier-general in any British army at that time. Blamey,26 to become commander of the AIF in 1939, was then chief staff officer of a division; Lavarack,27 to command the 7th Division, was an artillery major; Sturdee, to become Chief of the General Staff, was a major of engineers; Mackay,28 to command the 6th Division, was a battalion commander.

Bennett’s reputation continued to rise during his service with the AIF in France, and on several occasions before the war ended he temporarily commanded the 1st Division. After the war he became chairman of the New South Wales Repatriation Board, and commanded the 9th Infantry Brigade from 1921 to 1926. Then, aged 39, he stepped up to command of a division (the 2nd), highest appointment available in peacetime to a citizen soldier, and held it for five years before being put on the unattached list. He became President of the New South Wales Chamber of Manufactures in 1931, and in 1933 President of the Federal body, the Associated Chambers of Manufactures.

Suddenly, in 1937, while fears of another world war were being fanned by aggression by Italy in Abyssinia and Japan in China, Bennett stepped before the public as the author of a boldly-displayed article in the Sunday Sun of Sydney. Declaring that the militia was “inefficient and insufficient”, he asserted that nothing effective was being done to train senior citizen officers for high command. He alleged that attempts had been made to give command of all divisions to permanent officers to the exclusion of senior citizen officers, whom he considered more efficient. In succeeding articles he urged that all probable leaders be encouraged to fit themselves

for command; that the training of the rank and file be more comprehensive; and that Australian industry be organised to produce war requirements at short notice.

In place of a further article by Bennett which the Sunday Sun had promised, there appeared a statement that the Military Board had instructed Bennett to discontinue the series; and that newspaper made a heated attack on the Board.29 The controversy led to a lively discussion of Australia’s lack of preparedness by the Federal Cabinet; no action was taken against Bennett for his criticism.

After war broke out, however, Bennett was not given an appointment until July 1940, when he was placed in charge of the Training Depot of Eastern Command and was officer commanding the Volunteer Defence Corps; but he eagerly sought a more active appointment. In 1939 only two officers of the Australian Army were senior to him – Sir Brudenell White, and Sir William Glasgow,30 appointed High Commissioner to Canada at the end of 1939; yet Bennett, at 52, was not too old for any of the higher commands and had clearly demonstrated his capacity for leadership. He had been passed over for command of the Australian Corps and the 6th and 7th Divisions and, in the first instance, of the 8th. Behind this lay many factors, largely personal. Bennett’s aggressive temperament had shown itself in criticism of his superiors and others at intervals throughout his military career. Relations between professional and militia officers depended of course upon their capacity to appreciate each other’s virtues and the virtues of the two systems of training; but the references to the Staff Corps in his newspaper articles had caused resentment among professional officers. Bennett thus had become a controversial figure, and when leaders were sought who would command general support, strong-points of resistance to his being chosen were encountered. Pressing Brudenell White, while he was Chief of the General Staff, Bennett was told that he had “certain qualities and certain disqualities” for an active command.31 To a man of Bennett’s ambitious temperament, being shelved was a particularly galling experience which made him all the more determined to vindicate himself and his opinions. This chance arose when Sturdee became Chief of the General Staff; for he regarded Bennett as suitable, on the basis of experience, to take his place in command of the 8th Division, and it seemed to him that Bennett’s antipathy to professional officers had died down. The War Cabinet agreed to Sturdee’s recommendation.

Bennett succeeded to the command of a formation the staff and brigadiers of which had already been chosen by his predecessor, a regular. Such a succession is not infrequent in war and peace, but, in the circumstances mentioned above, it was perhaps unfortunate that Bennett missed

the opportunity of making the senior appointments in the division, and instead, took over a division in which they had already been made.

Events overseas resulted in some re-shaping of the 8th Division during the early stages of its existence. In September, General Blamey had urged that the 9th Division, which had been formed from troops diverted to England in June, be completed not from corps troops and reinforcements as had been planned, but from the brigades already formed in Australia. This request was agreed to, and in December the 24th Brigade was transferred to Egypt. A twelfth brigade was now needed to complete the infantry of the four divisions-6th, 7th, 8th and 9th – and in November the 27th Brigade was formed from recruits then training in Australia. This was the beginning of a transfer of brigades and even individual units from one division to another during the next few months, in response to emergencies which were to affect every division of the AIF. In this period the parts of the 8th Division were scattered throughout Australia. A difficult task was thus imposed on divisional headquarters at Rosebery Racecourse in New South Wales (which, in addition, had the task of administering all non-divisional AIF units in that State).

Brigadier Norman Marshall,32 chosen to command the new brigade, was a 54-years-old country man, son of a Presbyterian minister, who had risen from the ranks of the old AIF to become one of the outstanding battalion commanders in France in 1917-18. At a critical moment at Villers Bretonneux in April 1918 “it was he (wrote C. E. W. Bean) who took hold and for the rest of the night controlled more than any other man the 15th Brigade’s part in the operation”. In 1940 he was commanding the 1st Cavalry Brigade of the militia; in July he stepped back a rank (an action typical of the man) to take command of an infantry battalion in the Second AIF, when other leaders of about equal seniority in the old AIF, such as Mackay and Allen,33 were commanding divisions or brigades.

One regular and two citizen soldiers, all in their middle-forties, were chosen as his battalion commanders. Lieut-Colonel Boyes,34 to command the 2/26th (Queensland) Battalion, had been commissioned in the regular forces in 1918 and until 1938 had occupied positions as adjutant and quartermaster of militia battalions. At the outbreak of war in 1939 he was brigade major of a militia brigade, and in April 1940 was chosen as a brigade major in the 7th Division. He was junior both to Lieut-Colonel Robertson35 (2/29th Victorian Battalion) and Lieut-Colonel Galleghan36

(2/30th N.S.W. Battalion), each of whom had the added qualification of having served in France with the old AIF. Robertson, pleasant and likeable and a capable man-manager, was a fuel merchant and garage proprietor of Geelong, Victoria, who had given long years of service between the wars to the militia, in which he was commanding a battalion in 1939. Galleghan, senior of the three (in fact senior to all the battalion commanders in the 8th Division, for he had commanded three militia battalions in succession since 1932) had been twice severely wounded as a young ranker in the old AIF, and had been commissioned on his return to Australia. As a public servant he had spent most of his life in the Newcastle area until 1936, when he transferred to the Commonwealth Investigation Service in Sydney. Tall, dark-visaged, possessed of drive and determination, he tended to ride roughshod over the opinions of others, and had won a reputation as a disciplinarian which preceded him to his new battalion.

Major Pond,37 who became Marshall’s brigade major, was also a citizen soldier – somewhat a departure from the principle established with earlier formations of having a regular in such appointments; on the other hand, since the end of 1939, he had occupied staff appointments in a militia division. Commanding officers were given freedom to select other officers for their units, subject only to age limitations laid down by General Bennett, who required that lieutenants should be 26 or younger (whereas in earlier formations 30 had been the upper age limit) and that captains should be correspondingly youthful. Inevitably there were exceptions to the general rules.

Brigadier Marshall, who established his headquarters at the Royal Agricultural Showground in Sydney in November, had the difficult task of controlling battalions raised and training in widely separated areas. The 2/26th Battalion went into camp at Grovelly in Queensland; the 2/29th at Bonegilla in Victoria; the 2/30th at Tamworth, NSW. It was not until February that it was possible to concentrate the brigade. Nevertheless the fact that most of the men had been drawn from infantry recruit training battalions was a partial compensation, and in those first few months, despite the handicap of limited equipment, a sound basis for more ambitious training was laid. This was tackled vigorously, and the battalions were soon welded into a fighting formation well prepared and eager for action.

–:–

Many men of the 8th Division, who in civil life had been avid newspaper readers, and listeners to radio news, gave comparatively little attention to what was happening overseas as they became absorbed in the reveille to “lights out” round of camp life, then began to look forward eagerly to home leave; but meanwhile events were shaping which would draw the 8th Division into their course. On 27th September 1940 a ten-

year pact between Germany, Italy and Japan was signed in Berlin. The signatories undertook to “assist one another with all political, economic and military means if one of the high contracting parties should be attacked by a Power not at present involved in the European war, or in the Sino-Japanese conflict”. The pact was the outcome of persistent German efforts to commit Japan fully to the Axis, but it was more significant of Japan’s fear of missing opportunities for expansion which now seemed to lie open to her than of any affection she felt for Germany. The wording of the pact indicated clearly that extensive concession had been made by Germany to the Japanese viewpoint, especially in the passage which read:–

The Governments of Germany, Italy, and Japan consider it as a condition precedent of a lasting peace that each nation of the world be given its own proper place. They have, therefore, decided to stand together and to cooperate with one another in their efforts in Greater East Asia, and in the regions of Europe, wherein it is their prime purpose to establish and maintain a new order of things, calculated to promote the prosperity and welfare of the peoples there.38

The flowery wording of this passage, and the reference to each nation of the world being given “its proper place” were further typical of Japan’s official outlook at the time; and Japan’s prospective share in the spoils was clearly stated in the article of the pact which declared that “Germany and Italy recognise and respect the leadership of Japan, in the establishment of a New Order in Greater East Asia”.

Nevertheless, a lack of enthusiasm tinged with uneasiness haunted the conclusion of the pact. The British Ambassador to Japan recorded what he considered a well-substantiated story current at the time that while champagne corks popped at a party given by the Japanese Prime Minister to celebrate the occasion, Prince Konoye “was seen to melt into tears and the party, from all accounts, was a distinct frost”. Ciano, Italy’s Foreign Minister, despite his laudatory statement at the signing of the pact, wrote gloomily of the proceedings: “The ceremony was more or less like that of the Pact of Steel.39 But the atmosphere is cooler. Even the Berlin street crowd, a comparatively small one, comprised mostly of school children, cheers with regularity, but without conviction. Japan is far away. Its help is doubtful. One thing alone is certain: That the war will be long.”40

Plainly, however, Germany hoped that the pact would serve as a deterrent to United States aid to Britain, and would cause a diversion of British forces to East Asia, or at least tether those already there. To Japan it represented a counter to United States and British restraint upon Japanese expansionist moves. Matsuoka stated bluntly that Japan had concluded the pact because she recognised the principle of hakko ichiu (a Japanese term meaning the eight corners of the universe under one roof, or the whole world one family). “We three nations would be very

glad to welcome any other Powers, whether it were the United States or another, if they should desire to join us in the spirit of hakko ichiu,” he said. “However, we are firmly determined to eliminate any nation that may obstruct hakko ichiu.”

Mr Bullitt, the United States Ambassador to France, was equally blunt in addressing the Council on Foreign Relations in Chicago. “The pact,” he said, was “a contingent declaration of enmity”, adding that “if ever a clear warning was given to a nation that the three aggressors contemplated a future assault upon it, that warning was given to the American people”.

The Japanese Army and Navy quickly took advantage of a provision in the pact for the establishment in the three Axis capitals of mixed technical commissions. Japanese missions were promptly sent off to Berlin and Rome to pick up all the information they could that might help the Japanese forces. The head of the military mission to Berlin, Lieut-General Tomoyuki Yamashita, was to have plenty of opportunity to put it to practical use.

Far from acting as a deterrent to America, however, the pact was followed by a great acceleration of her aid to Britain, and of her own defence program. Already on 26th September a virtual ban had been placed upon export of any grade of iron or steel scrap to Japan. British and American policies in the Pacific and East Asia now drew closer together. Britain re-opened the Burma Road as from the 18th October, after her Ambassador in Washington had been assured by the American Secretary of State that “the special desire of this Government is to see Great Britain succeed in the war. Our acts and utterances with respect to the Pacific area will be more or less affected as to time and extent by the question of what course will most effectively and legitimately aid Great Britain in winning the war.”41 No doubt influenced by the growing cordiality of relations with the United States, Mr Churchill had informed President Roosevelt in advance of the intended re-opening of the Burma Road, adding:–

I know how difficult it is for you to say anything which would commit the United States to any hypothetical course of action in the Pacific. But I venture to ask whether at this time a simple action might not speak louder than words. Would it not be possible for you to send an American squadron, the bigger the better, to pay a friendly visit to Singapore? There they would be welcomed in a perfectly normal and rightful way. If desired, occasion might be taken of such a visit for a technical discussion of naval and military problems in those and Philippine waters, and the Dutch might be invited to join. Anything in this direction would have a marked deterrent effect upon a Japanese declaration of war upon us over the Burma Road opening.42

This proposal was discussed by the United States Standing Liaison Committee – a coordinating body for the military, naval, and diplomatic services which had been created in 1938. The committee agreed, however,

that sending a squadron to Singapore might precipitate action by Japan against the United States. Admiral Stark, the American Chief of Naval Operations, declared that “every day that we are able to maintain peace and still support the British is valuable time gained”; and General Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the Army, that the time was “as unfavourable a moment as you could choose” for provoking trouble.43 Thus military considerations were added to political ones favouring a cautious policy by the United States in the Pacific; and Britain like the Netherlands East Indies (which, since February, had been stonewalling Japanese demands for trade concessions) had to continue to temporise. Nevertheless, several conversations took place about this time between the American Secretary of State, Mr Hull, the British Ambassador, Lord Lothian, and the Australian Minister in Washington, Mr Casey, about means whereby the United States, Britain, Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands East Indies might exchange information as to the forces available to meet a Japanese attack. Lothian told Hull that Singapore was available to the United States Fleet at any time.

The entrance of the Japanese into Indo-China and the signing of the Tripartite Pact greatly discouraged the Chinese. On 18th October 1940 Chiang Kai-shek told the American Ambassador, Mr Nelson T. Johnson,44 that he was anxious lest the Japanese seize Singapore or cut the Burma Road.

Before either of these disasters, China must have economic aid plus numbers of U.S. aircraft manned by American volunteers. Unless this aid came soon, China might collapse. If it came in time, the internal situation would be restored and the Japanese forestalled. The aircraft would also permit the Generalissimo to effect a “fundamental solution” of the Pacific problem by destroying the Japanese Navy in its bases. Proposed a month before British carrier aircraft attacked the Italian Navy at Taranto, the Generalissimo’s plan might indeed have been the fundamental solution, but in the irony of history it was the Japanese who attempted the method at Pearl Harbour.45

The possibility of a joint defence agreement between the United States, Australia and New Zealand, had been mentioned by Casey in a cable to Canberra dated 3rd September. He said that the establishment of a permanent Joint Board of Defence (United States and Canada) and lease of sites for American bases in the British West Indies had inspired press references in America and elsewhere to the possibility of extension of arrangements on either or both of these lines to the Pacific and Australia. While he did not believe that for domestic political reasons the United States would consider any such extension before the presidential election in November, he thought it was not impossible after the elections. Casey asked for the views of the Australian Government defence advisers as

to the most telling arguments that he could have up his sleeve for use as opportunity arose, respecting the value to the United States of joint use of existing bases or rights to lease and build their own bases in the south-west Pacific. On 24th September the War Cabinet sent him notes by the Australian Defence Committee46 for the purpose.

On the same day, the Australian War Cabinet approved a proposal, suggested in August by the United Kingdom Chiefs of Staff, that a conference be held to consider the problems of defence of the East Asian area. Australia had proposed that it be held in Melbourne, but Singapore, where principally the British forces for the defence of the region were concentrated, was eventually chosen.

While preparations were being made for this conference, the War Cabinet was called upon to decide also the policy to be pursued by an Australian delegation to a conference to be held in New Delhi, convened by the Government of India with the consent of the United Kingdom to determine a joint war supply plan for the eastern group of Empire countries. The purpose of this Eastern supply conference was to ensure that maximum use would be made of the existing and potential capacity of each of the participating countries to supply the materials required in war. It was contemplated that the needs of each country, including essential needs of commerce and industry for maintenance of defence services and the civil population, should be met as far as possible within the group, and that any surplus production should be made available to Great Britain.

Before the departure of Sir Walter Massy-Greene, leader of the Australian delegation to this Eastern Group Conference, the Prime Minister instructed him, also in accordance with recommendations of the Defence Committee, that any policy of dependence on supplies from India was not acceptable to the Australian Government. This was particularly because of the risks associated with control of sea communications between the Eastern Group countries, political factors such as India’s attitude to attainment of self-government, and the internal and external security of India. Mr Menzies emphasised that Australia was not prepared to import things she could produce, and there was no intention of entering into commitments which might cramp development and expansion of her secondary industries.47

Before the Singapore conference assembled the three commanders in Malaya – Admiral Layton,48 General Bond and Air Vice-Marshal Babington49 – prepared a joint appreciation which was sent to the Chiefs of Staff in London on 16th October. In it they affirmed that, in the circumstances,

the air force was the principal weapon for the defence of Malaya. Its tasks should be to repulse any invading force while it was still at sea, shatter any attempted landings, and attack any troops who managed to get ashore. They urged that the British forces be authorised to advance into southern Thailand if the Japanese entered that country. They recommended that the air force be increased until its front-line strength was 566 aircraft, and the army until it contained 26 battalions and 14 field and 4 anti-tank batteries – the equivalent of about three divisions with artillery on a reduced scale.

The Singapore conference, held from 22nd to 31st October, was attended by staff officers from India, Australia, New Zealand and Burma, with an American naval officer as an observer.50 Before the conference got under way the Australian and New Zealand delegates contended that its scope should not be limited to south-east Asia but that it should consider the whole problem of Pacific defence. This proposal was referred to and approved by the British and Australian Governments. The conference concerned itself also with points for later staff talks with representatives of the Netherlands East Indies and United States in the event of these being authorised. The assumptions on which the conference worked were that, on the outbreak of war with Japan, the disposition of the Allies’ sea, land and air forces would be as at the time of the deliberations; that the United States would be neutral, but her intervention would be possible; that the Dutch might remain neutral, but their intervention was probable; that Australian and New Zealand naval forces would return to home waters, and a battle cruiser and an aircraft carrier would be sent to the Indian Ocean.

The delegates reviewed courses of action which appeared to be open to the Japanese if they entered the war on the side of the Axis powers; and concluded that, in such event, attack on the trade and communications of the Allies in the Pacific and Indian Oceans would be certain. They noted that the Chiefs of Staff in London considered an attack on Hong Kong probable, but that if American intervention were a strong possibility, attempts to invade Australia or New Zealand could be ruled out altogether. Other possibilities considered were: an attempt to seize islands in the Pacific Ocean to pave the way for invasion of Australia or New Zealand, and secure bases for attack on shipping in Australian and New Zealand waters; an attack on Malaya aimed at seizing Singapore; an attempt to seize bases in British Borneo preparatory to attack on Malaya; an attack on Burma by land and air from Indo-China and Thailand; an attack on the Netherlands East Indies or Timor to secure supplies and bases for further operations; an attack on Darwin; raids by warships and seaborne aircraft on points in Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere.

Area of deliberations, Singapore conference, October 1940

The conference decided that it was vital to defeat any attack on Malaya. A successful attack on the Netherlands East Indies or Timor (Portuguese and Dutch) would make it relatively easy to carry out naval and air attacks on Malaya, including Singapore, and on Darwin and the trade routes. An attempt to seize Darwin for use as a base was considered possible, although in view of the difficulties of maintaining a force there it was thought unlikely. Warning was given, however, that raids to destroy the facilities of the port must be guarded against.

The conference decided also that until sufficient naval forces were available for offensive action against the Japanese, it would be necessary to remain on the defensive, and to concentrate on the protection of vital points and vital trade and convoys. The first and immediate consideration must be to ensure the security of Malaya against direct attack. In view of the inadequacy of the naval forces then available, army and air forces in Malaya, including the reinforcements then being provided, were far below requirements in both numbers and equipment. This deficiency must be remedied immediately, and the further cooperation of India, Australia and New Zealand should be sought without delay. It was decided that Burma also was inadequately defended.

The conference considered that all available air forces should be used to prevent or at least deter the Japanese from establishing naval and air bases within striking distance of vital points in Malaya, Burma, the Netherlands East Indies, Australia and New Zealand. Advanced operational bases should be available throughout the area, so that aircraft could be concentrated at any point from its collective air resources. Preparation of the necessary facilities and ground organisation should therefore begin forthwith, irrespective of whether or not adequate aircraft were available.

While the possibility of a major expedition against Australia or New Zealand might be ruled out initially, such army and air forces must be maintained there as were necessary to deal with raids; and such naval and air forces as would ensure maintenance of vital trade, protect troop convoys, and carry out other local defence tasks. The conference noted the weakness inherent in the absence of fully-developed manufacturing industries in those countries, and that provision of adequate air forces in Australia and New Zealand in the near future was entirely dependent upon allotment by Britain of aircraft to meet rearmament and expansion programs.

Naval problems were reviewed, and it was noted that with the exception of capital ships, the minimum naval forces considered necessary to safeguard essential commitments in Australian and New Zealand waters could be provided by the return of Australian and New Zealand naval forces then serving overseas – provided that adequate air forces were maintained in the focal areas. Those available in the areas at the time were considered inadequate. The position in the Indian Ocean was dependent upon the arrival of naval reinforcements from elsewhere; among other things

it would be necessary to replace the Australian and New Zealand ships on that station. Early provision of air forces in the Indian Ocean was essential. The strengthening of facilities at Suva, Port Moresby, Thursday Island and Darwin should be expedited, in preparation for possible operations by the United States and British naval forces.

As to the military requirements of Malaya and Burma, the conference pointed to the fact that the British Government had asked India, subject to her own security requirements, to have four divisions ready for service overseas in May, July, October and December 1941 respectively. Although it had been planned to send these to the Middle East, the Indian Government was unlikely to raise any difficulties about their ultimate destination, provided adequate warning was given. From the AIF in Australia it should be possible to provide one strong brigade group and the necessary ancillary troops by the end of December 1940, if the British and Australian Governments agreed.

The most disturbing aspect of the report was its revelation in detail of the defence deficiencies in the danger zone extending from India to New Zealand. Although the Singapore naval base had been intended as a stronghold of sea power for the whole area, it was evident that its ability to serve this purpose to even a limited extent turned solely upon what the British Navy, desperately committed on the other side of the world, might be able eventually to spare. The Australian delegation recorded as its general conclusion that, in the absence of a main fleet in the area, the forces and equipment available for the defence of Malaya were totally inadequate to meet a major attack by Japan.

The conference estimated that Malaya needed an additional twelve battalions of infantry; six field or mountain regiments of artillery; eight anti-tank batteries; six infantry brigade anti-tank companies; three field companies of engineers; and three light tank companies, as well as 120 heavy and 98 light anti-aircraft guns and 138 searchlights. Additional requirements for Burma on a short-term basis included seven infantry battalions. The formations then in these areas were, with few exceptions, deficient in Bren guns and carriers, mortars, anti-tank guns and rifles, all forms of technical equipment, and mechanical transport. They were seriously short of rifles and ammunition, and equipment reserves were on a ninety-day reserve scale for normal garrison purposes only.

The aircraft deficiencies disclosed by the report were startling. The numbers of aircraft already available were stated to be 88 in Malaya and Burma, of which only 48 were classed as modern; 82 in Australia (42 modern).51 New Zealand had only 24 and the Indian Ocean 4, all classed as obsolete. It was estimated that to equip the squadrons which the conference considered necessary (leaving replacements out of account) 534 modern aircraft were needed in Malaya and Burma; 270 in Australia; 60 in New Zealand; and 87 in the Indian Ocean. On the information

before the conference, some 187 were needed in the Netherlands East Indies. A number of operational airfields, and advanced operational bases for land-planes and flying-boats, also were needed in Burma, Malaya, Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands East Indies. The full extent of planned output of modern military aircraft in Australia in 1941 was 180 Beauforts, of which 90 were for the RAAF and 90 for Britain.52 Prospects of being able to remedy deficiencies in arms, ammunition and equipment were shown to be bleak, although certain equipment and ammunition being produced in Australia might be supplied.

These disclosures left no room for complacency. When it considered the report, with the observations of the Australian delegation and the views of the Australian Chiefs of Staff, the Australian War Cabinet expressed grave concern at “the most serious position revealed in regard to the defence of Malaya and Singapore”, which was “so vital to the security of Australia”. Nevertheless, reluctance to send Australian troops to reinforce Malaya was still evident. The War Cabinet decided to tell the British Government that it considered it preferable to use Indian troops there for the reasons stated when the subject was previously under consideration. If, however, Imperial strategy should call for Australian troops in Malaya, dispatch of a brigade group at an early date, with the necessary maintenance troops and equipment on a modified scale, would be concurred in; but the War Cabinet added the proviso that the troops should be concentrated in the Middle East as soon as circumstances permitted.

The War Cabinet decided that work should begin immediately on the extension of air force stations in Australia and the New Guinea–Solomon Islands–New Hebrides area; and that the British Government be asked to expedite allotment of aircraft to Australia to enable her to meet her share of responsibility for the air defence of the mainland and the islands. The minimum number of aircraft required to provide initial equipment of the squadrons earmarked for this task was stated to be 320; the deficiency (in modern aircraft) 278.

As to the naval problem, the War Cabinet noted the assumption by the Singapore conference that, in a war with Japan, Australian and New Zealand naval forces would return to their home waters, and that a British battle cruiser and aircraft carrier would proceed to the Indian Ocean. It agreed to give whatever naval assistance it could by allotting antisubmarine and minesweeping vessels, mines, and depth-charges, for use beyond Australian waters. The Chiefs of Staff reported that they were already expediting the expansion of naval stations at Darwin and Port Moresby, and strengthening the defences of Thursday Island.