Chapter 10: Mounting Disasters

The Japanese forces as a whole were now riding a wave of victories. In the colony of Hong Kong, which had become a perilously-situated extremity of British power, the enemy troops continued on 9th December their advance on the Gin Drinkers’ Line. This line, ten and a half miles long, occupied a commanding position on the mainland, but had little depth. Major-General Maltby,1 commander of the British troops in China and of the Hong Kong Fortress, estimated that the line might be held for seven days or more, but only if there was no strong and capable offensive against it. It was hoped that sufficient delay would be imposed to enable final measures, possible only when war was certain, to be taken for defence of the main stronghold, the island of Hong Kong itself.

The island, with an area of thirty-two square miles, is traversed by an east-west range of steep, conical hills, rising to 1,800 feet at Victoria Peak. The densely-populated city of Victoria occupied principally a flat, narrow strip of land along the north-western shore. Some shelters against bombing and shelling had been provided, but for the majority of its 1,750,000 inhabitants, mostly Chinese, no such protection was available. Its water supply came partly from the mainland, and partly from reservoirs on the island itself. In both respects it was vulnerable to enemy action. Since it was first occupied by the British in 1841, the island had graduated, like Singapore, from earlier use by pirates and fishermen, through increasingly lucrative stages, to affluence as a great port and commercial centre on the main Far Eastern trade route.2 The colony had been extended in 1860 to include part of the peninsula of Kowloon, and 359 square miles of adjacent territory was acquired in 1898 on a ninety-nine years’ lease; but development of the island as a naval base had given way, as a result of the Washington Agreement of 1922, to construction of the Singapore Base.

The total force for defence of the colony, including naval and air force personnel and non-combatant services, was about 14,500 men. Its principal components, as mentioned earlier, were two United Kingdom, two Indian, and two Canadian battalions. Both the United Kingdom and the Indian battalions had lost some of their most experienced officers and men by transfer to service elsewhere. The Canadians had not received the concentrated and rigorous training necessary to fit them for battle. The outbreak of war had prevented their carriers and lorries, dispatched later than the troops, from reaching Hong Kong. The artillery on the island was manned largely by Indians and volunteers; some of the guns dated

The Attack on Hong Kong

from the 1914-18 war, and were drawn by hired vehicles driven by Chinese civilians. Protracted naval defence of Hong Kong was out of the question, for only three destroyers, a flotilla of eight motor torpedo boats, four gunboats, and some armed patrol vessels were stationed there at the outbreak of war with Japan, and two of the destroyers sailed for Singapore on 8th December. Prospects of naval reinforcement were negligible. On the other hand, denial of the port to the enemy was considered highly important.

As in Malaya and elsewhere, a poor opinion had been widely held of the quality of the Japanese forces despite much available information to the contrary. They were considered, for instance, to be poorly qualified for night operations; to prefer stereotyped methods; and to be below first-class European standards in the air.

Until the arrival of the Canadian troops it had been considered practicable to employ only one infantry battalion on the mainland, but three were then allotted to it, with a proportion of mobile artillery. At the time of attack the 5/7th Rajput occupied the right sector of the Gin Drinkers’ Line, the 2/14th Punjab the centre, and the 2/Royal Scots the left, the whole force being commanded by Brigadier Wallis.3 On the island, under the Canadian commander, Brigadier Lawson,4 were a machine-gun battalion (1/Middlesex) for beach defence, the Winnipeg Grenadiers in the south-west sector and the Royal Rifles of Canada in the south-east. The defences included some thirty fixed guns of up to 9.2-inch calibre, but lacking radar equipment. Anti-aircraft armament was on a small scale, and such aircraft as the colony possessed had been put out of action in the first day of war.

Pre-conceived ideas about the Japanese had rapidly to be revised as their attack developed. Their patrols and small columns, led by guides familiar with the terrain, moved swiftly over cross-country tracks by day and night, and the Japanese forces as a whole acted with such speed and efficiency that it was apparent they had been intensively trained for their task. Although on 9th December they engaged chiefly in patrol action, they surprised the defenders of Shing Mun Redoubt, a key position largely dominating the left sector of the Gin Drinkers’ Line, and captured it, including a Scots company headquarters, near midnight. This gravely affected the situation generally, and a company of the Grenadiers was brought from the island to strengthen the mainland forces. A Japanese attack from the Redoubt next morning was halted by artillery and a Rajput company which had been moved into a gap on the right of the Scots; but the centre and left companies of the Scots had become dangerously exposed, and they were withdrawn late in the afternoon to an inner line. Shelling and air attacks were carried out by the enemy during the day. At dawn on the 11th Japanese troops turned the left flank of the Scots,

and though the Grenadier company and a detachment of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps were brought into action,5 the position became so critical that withdrawal of the mainland forces, except 5/7th Rajput, was ordered. The Rajputs were to occupy Devil’s Peak Peninsula, covering the narrow Lye Mun Passage between the peninsula and the island.

The Japanese extended their activities during the day to attempted landings on Lamma and Aberdeen Islands, and stepped up artillery and air attack. Withdrawal of the British forces from the mainland, as ordered, was carried out during the night. Because of the weight of the attack and other factors, including rapidly increasing water transport difficulties, Devil’s Peak Peninsula too was evacuated, with naval aid, early in the morning of 12th December. The withdrawal imposed an exhausting task on the Indian battalions who, short of transport, had to manhandle mortars and other equipment over difficult country and to fend off the enemy, while under dive-bombing attacks and mortar fire. The whole of the northern portion of the island now came under mortar and artillery fire. This, and the fact that the resistance on the mainland had lasted only four days, was of course disconcerting to the civilian population as well as to the British forces.

The Japanese forces on the mainland comprised principally the three regiments of the 38th Division – the 228th and 230th Regiments with three mountain artillery battalions on the right, and the 229th Regiment on the left. Expecting a longer resistance, they had rapidly to readjust their plans to what had happened. At 9 a.m.6 on the 13th a launch flying a white flag reached the island from Kowloon, with a letter to the Governor of Hong Kong and Commander-in-Chief, Sir Mark Young, from Lieut-General T. Sakai, commander of the Japanese XXIII Army, demanding the surrender of the colony. The offer was sharply rejected, an increasingly heavy bombardment of the island followed, and Japanese were seen to be collecting launches in Kowloon Bay. The British forces were reorganised into the East and West Brigades. The East Brigade, commanded by Wallis, comprised the Royal Rifles of Canada and the 5/7th Rajput; companies of the 1/Middlesex were also under command, and two companies of Volunteers in reserve. The West Brigade – the Royal Scots (in reserve), the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the 2/14th Punjab, with the rest of 1/Middlesex and four Volunteer companies, also in reserve – was placed under Lawson. The Middlesex companies were manning pill-boxes on the perimeter of the island.

Serious fires, civil disorder, sniping by “fifth columnists” and desertion of locally-enlisted army transport drivers soon contributed to the island’s difficulties. Accurate and intensive Japanese shelling began putting guns out of action on the 14th, and on the 15th was mainly directed at pillboxes along the north shore. A night landing on the north-east part of the island was attempted by Japanese troops using small rubber boats and

rafts, but was repulsed. Resistance was encouraged by reports that Chinese forces were moving towards Hong Kong, though Maltby considered that they could not give effective assistance until early in January. Continuous pounding from land and air, mainly of military objectives, had caused extensive damage and put a heavy strain on the defenders when, on 17th December, the Japanese renewed proposals for surrender. These were again rejected, and next day Japanese shelling and air raids became less discriminate, as had been hinted by the envoys. Petrol and oil tanks were set ablaze, and burned for several days. Further concentration of water transport craft by the enemy was observed. Shelling of the north-east sector was particularly heavy, and frequently cut communications with the pill-boxes. By now, the destroyer (Thracian) had been disabled, and the only British naval vessels in action were two gunboats and a depleted motor torpedo boat flotilla.

Japanese forces swarmed over the strait and landed on a two-mile front in the north-east of the island on the night of 18th–19th December. Despite concentrated fire from the Rajputs to whom the sector had been allotted, and shelling by British artillery, the Japanese 229th Regiment occupied Lye Mun Gap and Mount Parker, the 228th Regiment won its way to Mount Butler, and the 230th Regiment to Jardine’s Lookout. There they dominated the approaches from the area to the Wong Nei Chong Gap, behind which the West Brigade was disposed from north to south across the island. Although the enemy gained access to the North Point power station area, resistance was maintained at the station throughout the night by a force known as the “Hughesiliers”,7 with power company employees, nine Free French personnel, and some wounded of the 1/Middlesex. Most of the force fought in near-by streets next day until killed or captured. Resistance was continued in the main office of the building until 2 p.m.

Trying to check or repulse the invaders, Lawson sent forward three platoons and then a company of Grenadiers, while Fortress Headquarters organised other reinforcements. The Grenadiers at first made good progress. Led by Company Sergeant-Major J. R. Osborn, some of them captured Mount Butler and held it for three hours. They were then dislodged, and rejoined remnants of their company trying to get back to brigade headquarters.

Enemy grenades began to fall in the company position. Osborn caught several and threw them back. At last one fell where he could not retrieve it in time; and the Sergeant-Major, shouting a warning, threw himself upon it as it exploded, giving his life for his comrades.8

Few of the company, however, escaped being killed, wounded, or taken prisoner; and, at 10 a.m. on the 19th, Lawson reported to Fortress Headquarters that, as the Japanese were firing at point-blank range into his headquarters at Wong Nei Chong Gap, he was about to fight it out in

the open. He and nearly all the staffs at the headquarters – West Brigade, West Group artillery, and a counter-battery group – were killed. Maltby himself took over command of the brigade until next day, when he passed it to Colonel Rose,9 of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps. The Governor, Sir Mark Young, emphasised to Maltby the importance of fighting to the end, however bad might be the military outlook, on the ground that every day gained was a direct help to the British war effort.

A motor torpedo boat attack on Japanese being ferried to the island met with some success, but fire from both sides of the harbour, and from fighter aircraft, prevented it from being developed as planned. As the Japanese became established in the north-east, and brought in support and supplies under cover of their positions, efforts by the West Brigade to dislodge them gradually gave way to defence on its north-south line. The Rajputs having been practically destroyed in opposing the landings, the East Brigade was withdrawn from a line slanting south-westward on the right of the former Rajput line to one running east-westward to Repulse Bay, covering Stanley Peninsula and Fort Stanley. Misunderstanding of an order lost the brigade its mobile artillery in the process. The brigade was organised in its new position for a counter-attack on 20th December along two lines of advance – one via the Repulse Bay road to the Wong Nei Chong Gap, and the other along the western slopes of Violet Hill south-east of the Gap. The advance was commenced at 8 a.m., but two hours later a company of Royal Rifles encountered Japanese troops surrounding the Repulse Bay Hotel, at the head of Repulse Bay. The Canadians drove them off, and found a number of European women and children in the hotel being defended by a mixed party led by a Middlesex lieutenant. The advance generally was soon halted by superior numbers (two battalions of 229th Regiment) and as night closed in the brigade fell back on its former positions.

It became increasingly evident as the fighting on the island continued that Japanese command of the air and sea, and the weight of their attack, made defeat inevitable in the absence of speedy aid from outside. All available forces, including navy, air, and army service corps personnel joined in heroic efforts to retrieve the situation. In the course of the desperate fighting the Scots took revenge for their reverse on the mainland, but suffered further severe casualties. The 1/Middlesex distinguished itself particularly in defence of Leighton Hill. Maltby recorded that the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps proved themselves stubborn and gallant soldiers. Progressively weakened, the defenders were however driven southward and westward, and a wedge was driven between the East and West Brigades. On the night of 24th December a bombardment commenced of the centre of Victoria, capital of the colony; of the naval dockyard;

and of Fortress Headquarters. Japanese patrols were penetrating the outskirts of the city.

Christmas morning presented a desperate situation, especially as failure of the water supply was imminent. Again the Japanese sent envoys – this time a British officer and a civilian whom they had captured – to testify to the formidable array of men and guns they had seen massed for final assault. It was nevertheless decided to fight on, but the military situation so deteriorated that soon after 3 p.m. Maltby told the Governor that no further effective resistance was possible. Responsible also for the civilian population, Sir Mark Young thereupon authorised negotiations for a ceasefire. He formally surrendered the colony later in the afternoon. Holding out at Fort Stanley, Brigadier Wallis demanded confirmation in writing of verbal orders brought to him through the Japanese lines to surrender. It was not until 2.30 a.m. on 26th December that he ordered that a white flag be hoisted.

Many factors additional to Japanese command of air and sea, and the extent and efficiency of their land forces, entered into the defeat. Commenting on the enemy tactics, Maltby said later that patrols

... advanced by paths which could have been known only to locals or from detailed reconnaissance. Armed agents in Kowloon and Hong Kong systematically fired during the hours of darkness on troops, sentries, cars and dispatch riders. ... After the landing on the island had been effected, penetration to cut the island in half was assisted by local guides who led the columns by most difficult routes ... marked maps found on dead officers gave a surprising amount of exact detail, which included our defences and much of our wire. Every officer seemed to be in possession of such a map. ... They seemed to be in possession of a very full Order of Battle, and knew the names of most of the senior and commanding officers.10

The British battle casualties in the defence of Hong Kong were estimated at nearly 4,500; and 11,848 combatants were lost in the fighting and as a result of the surrender. The official total of Japanese battle casualties was 2,754. Capture of the colony by the Japanese was not only a blow at British power and prestige in the Far East: it also provided the enemy with an additional stronghold in the regions they had determined to dominate, and cancelled Hong Kong as a means of bolstering Chinese resistance.

–:–

Japanese forces were sweeping over United States possessions also. Pearl Harbour, stricken as it was and presenting a tempting chance to acquire a stronghold menacing even American home waters, was not further molested. Midway Island suffered only submarine bombardments in the period with which this volume deals. But after air attacks lasting two days, invading and supporting forces overwhelmed on 10th December the small garrison on Guam Island. The Japanese were able to develop the island as a naval and air base about equidistant from New Guinea and the Philippines. An attempt to land at Wake Island on the 11th was defeated; but on the 23rd a second and more formidable invasion force

bore down on the isolated garrison. Heavily outnumbered, and amid the wreckage of sixteen bombing raids, the Americans nevertheless fought until they too had no choice but to surrender. By the evening the enemy was in possession of that base also.

Although what happened at Pearl Harbour, Wake, and Guam belongs to naval rather than to army history, the blow to American sea power thus inflicted was fundamental to the course of the war, and thus to the nature of the struggle in which land forces became engaged. It affected, for instance, defence of the Philippine Islands, where resistance to continued assault became a struggle isolated from the aid which otherwise America might have been able to give.

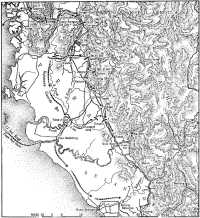

In the Philippines as in Malaya, the overwhelming initial successes of the enemy airmen left little to be feared from the defending air forces. The Japanese were nervous of submarine action, but no decisive opposition was to be expected from such surface units of the United States Asiatic Fleet as remained in Philippine waters. The Japanese plan was to seize bases at the northern and southern ends of the Philippine archipelago, and then, in the third week of the war, to land their main force – including the 16th and 48th Divisions – on Luzon. Thus by 20th December, enemy marines had seized Batan and Camiguin Islands, north of Luzon. Landings had then been made at Aparri, on the north coast of Luzon; near Vigan (north-western Luzon); at Legaspi, near the south-eastern tip of the island; and at Davao, in the south-eastern portion of Mindanao Island. Aircraft had again bombed airfields in the vicinity of Manila, and destroyed the near-by naval dockyard at Cavite on Manila Bay. Fourteen Flying Fortresses, the only survivors of their kind in the Philippines, had left for the Batchelor Field in the Northern Territory of Australia.11

By 9th December the army and navy planning staffs in Washington had decided that the Philippines could not be held, but, at President Roosevelt’s insistence, the navy was instructed to do what it could to help MacArthur. On 14th December Colonel Eisenhower, by then on General Marshall’s staff, prepared a paper emphasising the need “to convert Australia into a military base from which supplies might be ferried northward to the Philippines”; a principal which was thenceforward accepted.12

In the Philippines the defending army was organised into four commands: North Luzon (four divisions), South Luzon (two divisions), the harbour defences of Manila Bay, and the Southern Islands (three divisions). One Philippine Army division and the “Philippine Division” of the United States Army were in reserve.

The 48th Japanese Division was landed in Lingayen Gulf on 22nd December, and part of the 16th Division in Lamon Bay, south-east of Manila on 23rd and 24th December. On the 23rd General MacArthur decided to withdraw the forces on Luzon into the Bataan Peninsula, and next day he moved his headquarters to the island fortress of Corregidor

Japanese landings in the Philippines

in Manila Bay. By 2nd January both North and South Luzon Forces, with a combined strength of about 50,000, had succeeded in withdrawing into Bataan, which is about 30 miles long and 20 wide. They formed a line across the neck of the peninsula. Also on the 2nd the Japanese entered Manila.

Prospects of relief for MacArthur’s forces were now about as remote as Hong Kong’s had been. Not only had the Philippines been practically eliminated as a danger to Japan’s southward moves; the islands could now be used as an aid to other operations. Having played its part in the landings, the Japanese Third Fleet proceeded as planned against Dutch Borneo, Celebes, Ambon and Timor.

–:–

An invasion of British Borneo had been planned by the Japanese high command as part of the opening phase of their overall plan. Tactically, possession of this territory would safeguard their communications with Malaya, and facilitate subsequent movement on Java. It would also secure for Japan supplies of oil which she urgently needed.

Occupying an area along the northern and north-western seaboards of the island of Borneo, the greater part of which was owned by the Dutch, British Borneo comprised the two principal states of British North Borneo and Sarawak; between these two areas, Brunei, a small native state under British protection; and Labuan, an island Crown colony at the northern entrance to Brunei Bay. Generally clad in dense jungle, the island of Borneo as a whole was largely undeveloped and unexplored, but both the British and the Dutch portions were rich in oil and other resources. Although, like the near-by

Philippine Islands, it lay at the approaches from Japan to Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies, neither the Dutch nor the British had found it practicable to spare more than small detachments for its defence.

Defence of British Borneo’s oilfields at Miri, in Sarawak near its boundary with Brunei, and at Seria in the latter state, had therefore been ruled out in favour of destruction of the installations on the fields and at Lutong, nearby, where the oil was refined.

A company of the 2/15th Punjab Regiment had been sent in December 1940 to Miri to cover the demolitions when they became necessary, and in August 1941 partial application of a denial scheme had reduced the

output of oil by 70 per cent. The rest of the 2/15th Punjab, sent in May 1941 to Kuching, capital of Sarawak, was to defend this centre near the south-western extremity of the state because of its airfield, seven miles south of the town, and because a Dutch airfield known as Singkawang II lay only 60 miles to the south-west. The other forces in Sarawak, comprising a local Volunteer Corps, a Coastal Marine Service, the armed police, and the Sarawak Rangers (native troops) were bracketed with the Punjabs in a command known as “Sarfor” (Lieut-Colonel Lane).13 It was realised, however, that such a force could not be expected to cope with any large-scale attack upon the town, and when in September 1941 it appeared that this must be expected, a conference of British and Dutch authorities decided that the airfield only would be defended. Demolitions of the oilfield installations and of the refinery were carried out on 8th December. On the 13th the detachment at Miri, with the oil staffs, left by sea for Kuching.

This was the day on which a Japanese convoy left Camranh Bay (Indo-China) and caused concern in Malaya lest it be headed for Mersing or thereabouts. With an escort of cruisers and destroyers, and two seaplane tenders for reconnaissance, it carried the Japanese 35th Infantry Brigade Headquarters and the 124th Regiment from the 18th Division, and the 2nd Yokosuka Naval Landing Force. The convoy anchored off Miri a little before midnight on the 15th December, and swiftly occupied the oilfields without opposition other than by rough seas during landings. In raids on the 17th, 18th, and 19th Dutch bombers sank a destroyer (Shinonome) and some landing craft. By 22nd December, however, fifteen Japanese medium attack planes and fighter aircraft were using an airstrip at Miri despite the damage which had been done to it before the Punjab company withdrew.

Kuching was raided by Japanese bombers on 19th December, and Dutch planes reported to Air Headquarters, Far East, on the morning of the 23rd that a convoy (carrying part of the force which had reached Miri) was approaching the town. Bombers at Singkawang II were ordered to attack, but the enemy forestalled the operation by a raid on that airfield. As a result, the field was so damaged that with the concurrence of Air Headquarters the planes stationed there were withdrawn during the afternoon to Palembang, in Sumatra. A Dutch submarine torpedoed four of the six transports near the anchorage off Kuching on the night of the 23rd, but a landing had been made by dawn next day. Another Dutch submarine sank a second Japanese destroyer (Sagiri) the following night before being herself sunk by a depth-charge. Five Blenheim bombers from Singapore Island also raided the convoy, causing minor loss.

A message from Malaya Command reporting the approach of the convoy had been received in Kuching at 9 p.m. on the 23rd – two hours after the convoy had been sighted from the near-by coast. Although in pursuance of his orders Lane had disposed troops for the defence of the

airfield, the message contained an order for its destruction. Reporting that it was too late to alter his plans, he received a reply next day reiterating the order. He was to resist the Japanese as long as he could, and then to act as he thought best in the interests of Dutch West Borneo. On 24th December, despite resistance which cost the enemy seven landing craft and a number of casualties, they had forced their way up the Santubong River to Kuching, and captured the city by 4.30 p.m. At nightfall they were advancing on the airfield; and next day, concerned lest Japanese encircling moves might cut off his force, Lane ordered its withdrawal into Dutch West Borneo. The force was attacked as this was in progress, and all but one platoon of the rearguard of two Punjabi companies were killed or captured. A further 180 men became separated from the force during the night at a river crossing and most of the transport was abandoned. This party, however, rejoined the column when, having parted near the border from its Sarawak State Forces component, it reached Singkawang II airfield on 29th December. Women, children, and Volunteers who had accompanied the column were sent to a point on the coast from which they were evacuated on 25th January. The Punjabis meanwhile came under Dutch command, as part of a garrison of 750 Dutch Bornean troops for defence of the airfield and its surrounding area.14

–:–

In Malaya, intensive air attacks on ground troops which began on 23rd December added to the pressure of the Japanese thrust down the western part of the peninsula. In keeping with the orders issued by General Percival on 18th December, successive positions along the trunk road south-east of where it crossed the Perak were chosen as means of delaying the enemy. The next major stand was to be made at Kampar, north of a junction of the road and the railway, and 23 miles south of Ipoh. General Heath ordered the reconstituted 15th Brigade Group to occupy this position while the 12th Brigade was disposed north of Ipoh and the 28th Brigade south of it and on the road to Blanja.

The problems presented to the Japanese in crossing the Perak caused a lull on this front, and Christmas Day was observed by the British forces in varying ways and circumstances. The scene which met General Bennett as he visited some of his men at their Christmas dinner was typical of something which orthodox disciplinarians were apt to deplore. “I found the officers waiting on the men at table,” he recorded, “the light-hearted men addressing them in the local fashion as ‘boy’ and demanding better service. While the men enjoyed their Christmas fare, the sergeants relieved them by taking over their guard duties.”15

“I wondered,” Bennett commented, “if they realised that they would soon be fighting for dear life.” He had reported on 23rd December to the Chief of the General Staff (General Sturdee) that positions were

being prepared in the vicinity of Gemas, on the main road into Johore, and at Muar, on the coastal road west of it, adding:

When enemy advance is checked lost ground must be regained. This will require at least three divisions in my opinion. Again strongly urge that at least one of our divisions from Middle East be sent here as early as possible. Percival concurs.16

Sturdee replied next day that the Australian Government had decided to send to Malaya a machine-gun battalion and 1,800 reinforcements.

Further and very insistent warning came from the Australian Representative in Singapore (Mr Bowden). In the course of a cable received in Australia on Christmas Day, he declared:

... deterioration of our position in Malaya defence is assuming landslide proportions and in my firm belief is likely to cause a collapse in whole defence system. ... Present measures for reinforcing Malayan defences can from a practical viewpoint be regarded as little more than gestures. In my belief only thing that might save Singapore would be immediate dispatch from Middle East by air of powerful reinforcements, large numbers of latest fighter aircraft with ample operational personnel. Reinforcements of troops should be not in brigades but in divisions and to be of use they must arrive urgently. Anything that is not powerful modern and immediate is futile. As things stand at present fall of Singapore is to my mind only a matter of weeks. If Singapore and AIF in Malaya are to be saved, there must be very radical and effective action immediately ... plain fact is that without immediate air reinforcements Singapore must fall. Need for decision and action is a matter of hours not days.

The Australian Prime Minister, Mr Curtin, responded dynamically to this compelling situation. He addressed to both President Roosevelt and Mr Churchill, as they were conferring in Washington, a cable dated 25th December in which, after referring to reports he had received, he said:–

Fall of Singapore would mean isolation of Philippines, fall of Netherlands East Indies and attempt to smother all other bases. This would also sever our communications between Indian and Pacific Oceans in this region. The setback would be as serious to United States interests as to our own.

Reinforcements earmarked by United Kingdom Government for Singapore seem to us to be utterly inadequate in relation to aircraft particularly fighters....

It is in your power to meet situation. Should United States desire we would gladly accept United States command in Pacific Ocean area. President has said Australia will be base of utmost importance but in order that it shall remain a base Singapore must be reinforced. In spite of our great difficulties we are sending further reinforcements to Malaya. Please consider this matter of greatest urgency.

To the Australian Minister in Washington, Mr Casey, was sent an even more emphatic statement of the situation. “Please understand that stage of suggestion has passed,” he was told. “... This is the gravest type of emergency and everything will depend upon Churchill-Roosevelt decision to meet it in broadest way.”

Churchill cabled, also on the 25th, that Roosevelt had agreed that the leading brigade of the 18th British Division (which when Japan came into the war was rounding the Cape in American transports on its way to the Middle East, and was then diverted to Bombay and Ceylon) should go

direct to Singapore in the transport Mount Vernon.17 He reminded Curtin of his (Churchill’s) suggestion that an Australian division be recalled from Palestine to replace other troops going to Malaya, or sent direct to Singapore if that could be arranged. While indicating that he did not favour using up forces in an attempt to defend the northern part of Malaya, he spoke of Singapore as a fortress “which we are determined to defend with the utmost tenacity”.18 Referring to current consultations between himself and Roosevelt, and between their respective staffs, he said that not only were the Americans impressed with the importance of maintaining Singapore, but they were anxious to move a continuous flow of troops and aircraft through Australia for the relief of the Philippine Islands. The President was agreeable to troops and aircraft being diverted to Singapore should the Philippines fall, and was also quite willing to send substantial United States forces to Australia, where the Americans were anxious to establish important bases for the war against Japan.

The people of Australia were warned of the critical situation in a newspaper article by Mr Curtin published on 27th December. In this he declared:–

... the war with Japan is not a phase of the struggle with the Axis Powers, but is a new war ... we take the view that, while the determination of military policy is the Soviet’s business, we should be able to look forward with reason to aid from Russia against Japan. We look for a solid and impregnable barrier of democracies against the three Axis Powers and we refuse to accept the dictum that the Pacific struggle must be treated as a subordinate segment of the general conflict. ... The Australian Government, therefore, regards the Pacific struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must have the fullest say in the direction of the democracies’ fighting plan. Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom. We know the problems that the United Kingdom faces. ... But we know, too, that Australia can go and Britain can still hold on. We are, therefore, determined that Australia shall not go, and shall exert all our energies towards the shaping of a plan, with the United States as its keystone, which will give to our country some confidence of being able to hold out until the tide of battle swings against the enemy.19

This stung Mr Churchill, who later declared that it “produced the worst impression both in high American circles and in Canada”.20 Nevertheless, a concerted plan of the kind Curtin sought speedily emerged from the crisis; for on the night of 27th December in America (28th in Australia) Roosevelt proposed to Churchill the appointment of an officer to command the British, American, and Dutch forces in the war against Japan. He had suggested to his Chiefs of Staff that the officer should be General MacArthur,21 but after discussion agreed to propose General

Wavell. Churchill at first demurred, and his Chiefs of Staff opposed the nomination on the ground that responsibility for the all-too-likely disasters in the area would be placed on the shoulders of a British general rather than an American. It was, however, urged on him next day by Marshall, and the British Prime Minister thereupon sought and obtained his Cabinet’s approval of the plan. Trying to meet the immediate needs of Malaya, he had cabled on 25th December to General Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, suggesting that he should be able to spare at once, despite the needs of the Libyan offensive, four Hurricane fighter squadrons and an armoured brigade. Auchinleck immediately set afoot arrangements to comply. At this date the reinforcements under orders for Malaya comprised the 45th Indian Brigade Group; the 53rd Brigade Group (18th Division) with one anti-tank and two anti-aircraft regiments and the crated Hurricanes previously mentioned; reinforcements for the two Indian divisions; the 2/4th Australian Machine Gun Battalion; and reinforcements for the 8th Australian Division.

Quickly assenting to the establishment of a united command of forces resisting Japan, Curtin asked that Australia be represented on a joint body which it was proposed to set up, responsible to Churchill and Roosevelt, from whom Wavell would receive his orders. “I wish to express our great appreciation of the cohesion now established,” he cabled to Churchill, “and would like to say to you personally how appreciative we are of the great service you have rendered in your mission to the United States of America.” The clash between the two Prime Ministers had emphasised how differently the war appeared at this stage from the viewpoints of the United Kingdom and of Australia, and pointed clearly to the need for a better mutual understanding. It thus was an argument in favour of Curtin’s request for representation in the new controlling body, if one were needed additional to the facts that Australia had land forces in Malaya, Ambon, and Timor, in the ABDA (American, British, Dutch, Australian) area as it was about to be defined, and in Darwin to which it was later extended; that the I Australian Corps would soon be assigned to ABDA, and Australia was to become increasingly the main base of operations against Japan. Notwithstanding all this, Australia was given no direct representation on the controlling body, which comprised the United States Chiefs of Staff, and the Imperial Chiefs of Staff represented by senior officers in Washington, thousands of miles distant from the ABDA theatre of war at Australia’s northern portals.

–:–

While these high-level decisions were helping to shape the future, the 12th Indian Brigade again came to grips with the enemy in the fight for time in Malaya. The Japanese attacked at Chemor, north of Ipoh, in the afternoon of 26th December, and although by the end of next day the brigade had given little ground, its casualties were heavy and its men exhausted after twelve days of continuous action. Seeking to conserve his

forces for the defence of Kampar, General Paris decided to move his two forward brigades to positions south of Ipoh. During the night of 27th–28th December the 28th Brigade was moved to the right flank of Kampar, and the 12th Brigade was disposed in depth along the main road from Gopeng to Dipang, while the 15th Brigade prepared the Kampar position.

–:–

Meanwhile “Roseforce”, which Percival had ordered to be formed to raid Japanese communications west of the Perak, had come into existence, commanded by Captain Lloyd.22 Two naval motor launches, part of the Perak flotilla which also Percival had brought into existence, were used to transport the two-platoon force from Port Swettenham, south of Kuala Selangor, on 26th December for a landing up the Trong River, west and a little north of Ipoh. It was accompanied by Major Rose23 of the Argylls, whose pleas to be allowed to organise commando activities had given rise to the plan (though it was on a much smaller scale than he had urged).

The blight which had fallen on British endeavours in Malaya seemed to have fallen on this expedition also when the engine of the launch allotted to Lieutenant Perring’s24 platoon could not be started. After half an hour’s delay Lloyd ordered Lieutenant Sanderson’s25 platoon to go on alone. Thus delayed, and necessarily restricted in their objective, Sanderson and his men landed about 9 a.m. on 27th December near a road to the village of Trong. They eventually succeeded in ambushing a Japanese car carrying officers, followed by three lorries and a utility, on the main south coast road. The car was hit by a grenade and ran off the road. Sanderson emptied a drum of Tommy gun ammunition into it, killing the passengers. The two leading lorries capsized over an embankment, and their occupants also were shot. The remaining lorry halted, and the utility turned over. Their occupants hid behind a culvert, but were killed by grenades.

Having thus demonstrated what might have been done on a much larger scale to hamper and disconcert the enemy, the platoon rejoined the rest of the force. Five British soldiers who had become separated from their units in earlier fighting attached themselves to it, and it returned to Port Swettenham on the 29th. Sanderson’s platoon had the distinction of being the first body of Australian infantry to go into action against the Japanese in the Malayan campaign. Soon after, the depot ship for the

Perak flotilla was bombed and sunk, five vessels on their way to reinforce the flotilla were sunk or driven ashore, and both the flotilla and Rose-force were disbanded.

The little that had been done to form units for irregular warfare was represented principally by the Independent Company, previously mentioned, which became committed to the battlefront before it could be used in its special role; and by Lieut-Colonel Spencer Chapman’s Special Training School.26 Chapman, who after suffering many frustrations had at last obtained permission to organise parties to operate behind the Japanese lines, crossed the Perak on Christmas Day intending to meet Roseforce at a rendezvous and guide it to suitable targets. “Except for the occasional exercise we had had in the Forest Reserve at Bukit Timah, on Singapore Island, it was the first time I had been in real jungle,” he recorded in describing his adventure. The rendezvous failed, but he returned convinced that the Japanese lines of land communication, now becoming as extensive as those of the British forces, were very vulnerable to attack by men with the necessary training. His account of what he saw as he lay by a roadside and watched the enemy was illuminating. As he later described it, there were:–

hundreds and hundreds of them, pouring eastwards towards the Perak River. The majority of them were on bicycles in parties of forty or fifty, riding three or four abreast and talking and laughing just as if they were going to a football match. Indeed, some of them were actually wearing football jerseys; they seemed to have no standard uniform or equipment and were travelling as light as they possibly could. Some wore green, others grey, khaki or even dirty white. The majority had trousers hanging loose and enclosed in high boots or puttees; some had tight breeches and others shorts and rubber boots or gym shoes. Their hats showed the greatest variety: a few tin hats, topees of all shapes, wide-brimmed terai or ordinary felt hats; high-peaked jockey hats, little caps with eye-shades or even a piece of cloth tied round the head and hanging down behind. Their equipment and armament were equally varied and were slung over themselves and their bicycles with no apparent method. ...

The general impression was one of extraordinary determination: they had been ordered to go to the bridgehead, and in their thousands they were going, though their equipment was second-rate and motley and much of it had obviously been commandeered in Malaya. This was certainly true of their means of transport, for we saw several parties of soldiers on foot who were systematically searching the roadside kampongs, estate buildings and factories for bicycles and most of the cars and lorries bore local number plates. ...

All this was in very marked contrast to our own front-line soldiers, who were at this time equipped like Christmas trees with heavy boots, web equipment, packs, haversacks, water-bottles, blankets, ground-sheets, and even great-coats and respirators, so that they could hardly walk, much less fight.27

–:–

Not only was the Japanese 5th Division now concentrated in the vicinity of the Perak, but the Guards Division, allotted initially to the XV Army

for the occupation of Thailand, was arriving in the Taiping area to take part in the drive on the western front in Malaya. The Japanese were thus in a position to force the pace with fresh troops while the British forces engaged on this front became progressively more battle-worn and depleted of men and material. As the struggle developed, the enemy tactics generally continued to impose on the British a wide dispersal of forces and to necessitate frequent hasty movement of units to and from threatened areas, thus adding to the disruption and fatigue of actual combat. In the relatively open country of the Kampar position both sides would be able to use artillery to a greater extent than hitherto, but the Japanese still had the exclusive and powerful aid of tanks. In the air they could strike freely behind the British lines, and keep a close watch on the movement of opposing forces – formidable advantages at a time when air forces had become to a large extent the eyes and long-range artillery of land forces; and apt to be severely damaging to the morale of all but thoroughly trained and disciplined troops. The Japanese advance in the west now increasingly threatened the junction at Kuala Kubu, on the trunk road, of communications with the 9th Indian Division in the east.

The dominant feature of the Kampar position was Bujang Melaka – a 4,070-foot limestone mountain with steep sides thickly covered by jungle, whose western slopes descended to near the right of the main road where it reached Kampar. The mountain afforded good observation posts for artillery, commanding a wide and open tin-mining area to the north, west and south, although a large area of rubber plantations lay to the south-west. It was thus a local offset to enemy air observation while the position remained in British hands. The main sector of the Kampar position, adjacent to the township of Kampar, rested against the mountain and was occupied by the 15th Brigade (the combined 6th and 15th) with the 88th Field Regiment and 273rd Anti-Tank Battery under command. On the right, at Sahum, astride a road which looped the mountain and rejoined the main road below Kampar, was the 28th Brigade, to check any attempt to bypass Kampar by this route. To guard against attack from the direction of Telok Anson, in the south-west, the 12th Brigade was to be withdrawn to Bidor after completing its covering task, and the 1st Independent Company was to be stationed at Telok Anson.

The 12th Brigade was attacked at Gopeng on the afternoon of 28th December, and by midday on the 29th had been forced back to within three miles of Dipang. Brigadier Stewart was given permission to withdraw through Dipang after dark, and the 2nd Anti-Tank Battery had already gone back when a further enemy thrust, supported by tanks, nearly succeeded in disrupting the defence. The situation was saved only by resourceful action by Lieut-Colonel Deakin28 (5/2nd Punjab), whose men checked the enemy less than a mile north of Dipang. The brigade was thus enabled to withdraw to Bidor. Three attempts to demolish the Dipang bridge over the Sungei Kampar failed, but the fourth was successful.

The Japanese advance to Slim River

Further enemy advance along this road was discouraged by artillery fire, but enemy parties now appeared right of the Sahum position, and patrols were encountered south-west of Kampar. On New Year’s Day a heavy assault, preceded by a bombardment, was made on the main position where it was held by the Combined Surreys and Leicesters, now known as “the British Battalion”. The fighting lasted throughout the day, and, although the position was held, the Japanese gained a foothold on its extreme right, at Thompson’s Ridge. As pressure failed to develop at Sahum, Paris withdrew from that position all but a battalion and supporting artillery, and ordered the 28th Brigade’s 2/2nd Gurkha Rifles to the Slim River area – another prospective strongpoint in the British line of withdrawal – as a further precaution against attack from Telok Anson and thereabouts.

Also on 1st January, a tug towing barges was seen at the mouth of the Sungei Perak, and a large group of sea craft appeared at the mouth of the Sungei Bernam, the next large river to the south, bordering the States of Perak and Selangor. The two rivers, navigable for several miles, were only nine miles apart at the coast, and linked by a road which led to Telok Anson. A landing occurred during the night at the Bernam. Instead, therefore, of enjoying a respite at Bidor the 12th Brigade was sent to the area between Telok Anson and Changkat Jong, where the road forked north towards Kampar and north-east towards Bidor. The 2/1st Gurkha and 5/14th Punjab, in divisional reserve, had been placed on the road from the junction to Kampar in anticipation of the new threat. As was later established, the seaborne troops were the 11th Infantry Regiment, embarked at Port Weld, with a battalion of the 4th Guards Regiment which came down the Perak in small commandeered boats and landed at Telok Anson early on 2nd January. They were to thrust from there towards the trunk road.

The Japanese again attacked the Kampar position on 2nd January and pressed heavily upon the defenders. Although the position was still being held at the end of the day, street fighting had occurred in Telok Anson; the 1st Independent Company was withdrawn from the township through the Argylls; and by nightfall the 12th Brigade had been forced back to a position two miles west of Changkat Jong. As this thrust now endangered the rear of the troops at Kampar, Paris decided that Kampar must be abandoned. In the ensuing moves the 28th and 12th Brigades withdrew to the Slim River area, where on 4th January they were covered by the battered 15th Brigade at Sungkai. The British Battalion at Kampar, led by Lieut-Colonel Morrison,29 had borne for two days the weight of the Japanese 41st Infantry Regiment (of the 5th Division) supported by tanks and artillery.

–:–

The best news at this stage was that the 45th Indian Brigade – first of the reinforcements being hurried to Malaya – had reached Singapore. Semi-trained though it was, and with no experience of jungle warfare, it sustained hopes that if only the enemy could be delayed long enough, sufficient forces could be deployed on the mainland to save Singapore and its naval base. The promised brigade group of the 18th British Division was due in mid-January and the rest of the division, the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade, the 2/4th Australian Machine Gun Battalion, and Australian and Indian reinforcement drafts, later in the month or early in February.

The fact that the whole of the 18th British Division was to be committed to Malaya reflected critical decisions made by the United Kingdom Chiefs of Staff at a meeting on 1st January. They had decided that although defeat of Germany must continue to be the primary aim, the security of Singapore and maintenance of Indian Ocean communications were second in importance only to the security of the United Kingdom and its sea

communications. Despite the prize which appeared within grasp in Libya, where a successful offensive was in progress, development of the campaign in that theatre was made subject to the proviso that it must not prevent reinforcement of the Far East on a scale considered sufficient to hold the Japanese. The reinforcements for this purpose were to comprise (it was hoped) two divisions and an armoured brigade for Malaya, two divisions for the Netherlands East Indies, and two divisions and a light tank squadron for Burma. Endeavours were to be made to send to Malaya also eight light bomber squadrons, eight fighter squadrons, and two torpedo bomber squadrons; and to Burma six light bomber squadrons and six fighter squadrons. The United States was to be asked to do its utmost to strengthen the Netherlands East Indies air force with supplies via Australia. In fulfilment of this policy, the main body of the 18th Division, then at Bombay, was ordered at once to Malaya – despite misgivings which had been expressed by Wavell, when Commander-in-Chief in India, at the extent to which the resources to have been available in India were being diminished. Consent was obtained from the Australian Government on 6th January to the dispatch of the I Australian Corps (including the 6th and 7th Divisions) from the Middle East to the Far East; but this movement, which would make big demands on shipping, could not begin until the first week in February.

These decisions were in sharp contrast to the relative importance originally assigned to the Far East by Mr Churchill; the question now was whether or not sufficient time could be gained for them to become effective.

–:–

On the civil front in Malaya, realisation of the rapidly increasing peril which faced the established order was dawning bleakly:–

We enter into a New Year in local conditions that are simply fantastic (declared the Straits Times, an influential morning daily paper in Malaya). ... Even a month ago we were preparing for the usual New Year land and sea sports in Singapore. All accommodation at the hill stations was booked, prospects for the Penang race meeting were being discussed and hotels were announcing that very few tables were still available for the New Year’s festivities. ... Terrible changes have taken place with a rapidity that still leaves us a little bewildered, but as we recover from the initial shock, so do we become better able to see things in their proper perspective...30

This “proper perspective” was not, however, reflected in some official communiqués and statements, which seemed to be devoted to propping up prestige rather than to bringing home to the people of Malaya the real facts of the situation.31 The task of those concerned in wording them was admittedly not easy. Not only had care to be taken to avoid disclosure of information which might aid the enemy; thought had to be given also to the effect of news of British reverses upon the Asian population, whose outlook and interests were substantially different from those of the British

community. In the upshot the effect on neither community was satisfactory; nor did some sections of the civil administration engender confidence.

... the administration is displaying so little vigour (wrote a British observer in a day-by-day account of events) that the Asiatics are entirely uninspired and there’s an atmosphere of apathy – almost of resignation – about the whole place. One can’t resist the conclusion that the average citizen has little confidence that Singapore will hold – or even that the British intend to put up much of a fight for it. Why else should the trades people have stopped all credit facilities?32

Mr Duff Cooper expressed in a letter he sent by airmail to Mr Churchill his dissatisfaction with civil defence preparations. To the War Council on 31st December he pointed out that a breakdown in the civil defence organisation might be fatal to the defence of Singapore, and spoke of the need for some bold step which would revive public confidence. He then proposed that the Chief Engineer of Malaya Command, Brigadier Simson,33 be appointed Director-General of Civil Defence with plenary powers in Singapore Island and the State of Johore. In the terms in which he received the appointment from the Governor, however, Brigadier Simson was given such restricted powers that the position did not carry with it the freedom of action intended by Mr Duff Cooper, and even these powers did not extend beyond Singapore Island. Furthermore, the course of events was to give him little time to use them for what they were worth.34

–:–

General Heath had hoped that his 9th Division east of Malaya’s central range might become available for transfer along the east-west road to Kuala Kubu for assault on the Japanese left flank. It was decided, however, that to safeguard arrival at Singapore of the prospective reinforcement convoys, the division must hold Kuantan airfield and also deny the enemy access to central Malaya by the railway north of Kuala Lipis.

The importance of these considerations did not escape the Japanese. Equipped with horse transport, and using coastal seacraft, the 56th Infantry Regiment so surmounted the formidable difficulties presented by the undeveloped state of Kelantan and Trengganu that leading elements of the regiment were in contact with patrols from the 22nd Indian Brigade on 23rd December. Supported by the 5th Field Artillery Regiment, this brigade was on both sides of the Sungei Kuantan so that it might resist

attack from the sea, or on land from the north. The airfield was six miles from the coast, west of the river and near the main road. Under orders from Heath, who was anxious lest part of the force and its equipment be cut off east of the river, the commander, Brigadier Painter,35 on 30th December set afoot a withdrawal which would leave only the 2/18th Royal Garhwal covering the river east of the ferry crossing near the coast. By this time, however, a substantial Japanese force was nearby, and in a forestalling attack with air support seriously hampered the movement; but guns and transport were successfully withdrawn during the night. The Japanese quickly entered Kuantan, attacked the covering troops, and bombarded the ferry head.

On 31st December Painter received instructions to resist as long as possible, but not to jeopardise his brigade. After discussion with General Barstow, Painter disposed the 2/12th Frontier Force Regiment to hold the airfield and ordered that the 2/18th Royal Garhwal should cross the river that night. Two companies were cut off, but the rest made the crossing, and the ferry was sunk. The Japanese succeeded in infiltrating towards the airfield, and at the same time the decision to withdraw the 11th Division from Kampar on the 2nd–3rd made it essential to withdraw the 9th from the Kuantan area. Therefore on the 3rd orders were received from Heath to withdraw the brigade to Jerantut, where part of the 8th Indian Brigade was stationed. A further Japanese attack succeeded in isolating the rearguard of the 2/12th Frontier Force Regiment as it was leaving the airfield. Despite courageous action by Lieut-Colonel Cumming36 (for which subsequently he was awarded the Victoria Cross) the greater

part of two companies was lost. The rest of the brigade reached Jerantut without being further engaged, and by 7th January was disposed in the vicinity of Fraser’s Hill.

Concurrently with these developments on the eastern front, General Percival had urged upon General Heath that the airfields at Kuala Lumpur and Port Swettenham be denied to the enemy at least until 14th January_ Realising that unless provision were made to cope with further Japanese landings southward along the west coast he might be unable to fulfil this requirement, he sent units to Brigadier Moir,37 commanding the Lines of Communications, with orders to prevent landings at Kuala Selangor. To delay the enemy on the trunk road he ordered dispositions in depth, headed by the 12th and 28th Brigades in the Trolak-Slim River area to cover crossings of the river, and with the main defensive position some ten miles south of it, near Tanjong Malim.

At this stage the 42nd Infantry Regiment of the Japanese 5th Division, with a tank battalion, was under orders to press on along the trunk road towards Kuala Lumpur. The III/11th Battalion, followed by the 4th Guards Regiment, was to advance by land and sea to Kuala Selangor and Port Swettenham, thence also towards Kuala Lumpur. Other troops were to be ready to exploit these moves.

Attempts to land in the Kuala Selangor area on 2nd and 3rd January were repelled by artillery fire from Brigadier Moir’s force, which General Heath then reinforced. On 4th January, Japanese troops using a track north of Kuala Selangor drove back forward patrols, and reached the north bank of the Sungei Selangor. Next morning they were in contact with the 1st Independent Company covering bridges over the river in the Batang Berjuntai area, only eleven miles from Rawang on the trunk road. Brigadier Moorhead, commanding the 15th Indian Brigade, was now made responsible for the coastal sector. On 6th January he withdrew across the river his forces at Batang Berjuntai, and destroyed the bridges.

The 12th Brigade had moved into the Trolak position early on 4th January, and set to work preparing defences. That night the 15th Brigade was withdrawn from its covering position at Sungkai to occupy the main Tanjong Malim position. Constant attack by Japanese aircraft necessitated much of the 12th Brigade’s work being done at night. Coming on top of the men’s previous exertions and shortage of sleep, this resulted in extreme fatigue. Describing the condition of the 5/2nd Punjab at the time, its commander, Lieut-Colonel Deakin, was to write:–

The battalion was dead tired; most of all, the commanders whose responsibilities prevented them from snatching even a little fitful sleep. The battalion had withdrawn 176 miles in three weeks and had only three days’ rest. It had suffered 250 casualties of which a high proportion had been killed. The spirit of the men was low and the battalion had lost 50 per cent of its fighting efficiency.

The foremost part of the position comprised dense jungle through which the trunk road and railway ran roughly parallel, a few hundred

yards apart. The 4/19th Hyderabad (three companies) was forward; the 5/2nd Punjab was in the centre; and the Argylls were at the exits from the jungle at Trolak village and on an estate road branching from the trunk road. The 5/14th Punjab, from corps reserve, was at Kampong Slim under short notice to come forward to a check position about a mile south of Trolak.

The density of the vegetation was relied upon to keep enemy tanks and transport to the road; but although the 11th Division had enough anti-tank mines to pave large sections of the road with them, Stewart had only twenty-four, with some dannert wire and movable concrete blocks, to help impede an enemy advance. On the ground that his area gave little scope for artillery, only one battery of the 137th Field Regiment was deployed in support, while the rest waited between Kampong Slim and the Slim River bridge. Positions allocated by Brigadier Selby to the 28th Brigade were the 2/2nd Gurkha in the Slim River station area; the 2/9th Gurkha astride the road at Kampong Slim; and the 2/1st Gurkha in reserve at Cluny Estate – two miles and a half eastward. For the time being, however, the brigade was being rested in the Kampong Slim area. Instead of occupying the position at Tanjong Malim, the 15th Brigade was sent on 5th January to reinforce Moorhead’s coastal force.

Bombers pounded the 12th Brigade positions on the morning of the 5th, and Japanese infantry then advanced along. the railway. Waiting until they came within close range, the Hyderabads posted at this point directed on them such concentrated fire that the attack wilted. Next day the Japanese began an outflanking movement. A further infantry attack occurred soon after midnight on the 6th–7th along both the road and the railway; then, after a heavy barrage of mortar and artillery fire, and in clear moonlight, tanks suddenly appeared on the road.

These, it quickly became apparent, were part of a mechanised column with infantry interspersed between the armour. Under covering fire, the infantry soon disposed of the first road-block in its path; the forward company of Hyderabads was overrun; and with guns blazing the column charged on. Other Japanese troops renewed the pressure along the railway, and some of the tanks used an abandoned and overgrown section of old road in a flanking manoeuvre, with the result that rapid progress was made in this thrust also. The column was checked only when the leading tank entered a mined section of the road in front of the forward company of the 5/2nd Punjab near Milestone 61. Fierce fighting ensued, but here the first of two more disused deviations, which it had been intended to use for transport when the time came for the battalion to withdraw, enabled the enemy to move to the flank and rear. Again overrunning the position, the Japanese column advanced until it came upon more mines, in front of the reserve company of the 5/2nd Punjab. Furious fighting at this point lasted for an hour, but by exploiting the third loop section the Japanese achieved the same result as before. The suddenness of the penetration so disorganised communications that it was not until 6.30 a.m.,

when the position had been lost, that a dispatch rider delivered to General Paris’ headquarters at Tanjong Malim his first message from the 12th Brigade. Even this contained only a vague reference to “some sort of break-through”, for the information received by Stewart had lagged behind the night’s swiftly-moving events.

In was in fact about this time that four enemy medium tanks reached the first of two road-blocks hurriedly erected by the Argylls. The blocks, and such resistance as the battalion, lacking anti-tank guns, was able to offer to the tanks, were also overcome, and an attempt to destroy the bridge at Trolak failed. Although the Argyll companies on the railway and the estate road held out until they were surrounded, and then tried to fight their way out, all but about a hundred of them were lost. Thus the tactics in which the Argylls had been trained had been used with disastrous effect against them and the other units of Stewart’s brigade. At 7.30 a.m. the tanks reached the 5/14th Punjab moving up in column of companies to occupy their check position. Caught by surprise, the Punjabis were dispersed and a troop of anti-tank guns sent from the 28th Brigade to assist them in the position they were to occupy was overrun before it could fire a shot.

Unaware as he was that by daylight the Japanese had reached the Argylls, Paris had ordered Selby to deploy the 28th Brigade in the positions assigned to it, and Selby had issued his orders at 7 a.m. The 2/9th Gurkha were occupying positions near Kampong Slim when, about 8 a.m., the leading Japanese tanks roared past, and caught the 2/1st Gurkha Rifles moving in column of route to Cluny Estate. Thrown into confusion, the battalion dispersed. The tanks next paused briefly to fire on two batteries of the 137th Field Regiment parked beside the road, and reached the Slim River bridge about 8.30 a.m. An anti-aircraft battery brought two Bofors guns to bear on them at 100 yards’ range, but the shells bounced off the tanks, while they poured fire into the gun crews. Before the bridge could be destroyed, the tanks crossed it and continued their triumphant course. Two miles south of the bridge they met the 155th Field Regiment moving up to support the 28th Brigade. There, after the regiment’s headquarters had been overrun, and six hours after the column had commenced its thrust, they were stopped. Although under heavy fire, a howitzer detachment got a 4.5-inch howitzer into action. With their leading tank disabled, the Japanese thereafter confined themselves to tank patrols, and during the afternoon withdrew to the bridge.

Selby meanwhile had established the 28th Brigade headquarters, with headquarters of the 12th Brigade which had withdrawn down the estate road, on a hill east of Kampong Slim. On the incomplete information available to him, he decided to hold out until dusk and then withdraw his men down the railway, and across the river to Tanjong Malim. Pressed by increasing numbers of Japanese, the 2/9th Gurkha had difficulty in breaking contact for this move. The one bridge which had been successfully blown was that which had carried the railway line across the Slim

River. A hurriedly constructed plank walk served as a perilous substitute. Because of the congestion at its approaches, a number of men entered the water downstream. Some were swept away by the current, and others lost their way.

Next day – 8th January – the strength of the 12th Brigade was fourteen officers and 409 men. The 2/1st Gurkha had been lost, and of the other two battalions of the 28th Brigade there remained a total of only 750 men. The guns and equipment of two field batteries and two troops of antitank guns, and all the transport of the two brigades, had been forfeited. Although it had absorbed the 12th Brigade to make good its losses from Jitra to the Perak, the 11th Indian Division had suffered another disastrous débâcle.

After the campaign opened there was no reason to under-estimate the enemy; indeed the tendency was now to over-estimate him. Yet as events proved, the precautions taken to meet attack along the main route of the Japanese advance were surprisingly inadequate. Once again, the impetus of the enemy had thrown the machinery of control out of gear, and the defenders off balance. The Japanese had repeated their success at Jitra, and by similar means. It was discovered later that the battle was won by the Japanese 42nd Infantry Regiment, aided by a tank battalion and part of an artillery regiment. The spearhead of the attack comprised one tank company, an infantry battalion in carriers and lorries, and some engineers.

The tactics employed by the Japanese from the commencement of their invasion of Malaya – in particular their enveloping type of attack and the flexibility and momentum of their movements – had been consistent. They could hardly have been cause for surprise had the substance of Intelligence reports on the subject been adequately circulated and sufficiently digested by commanders; yet the enemy had employed them with unfailing success. The overall tactical weakness of the dispositions which had been forced on the army for the defence of airfields was of course a fundamental disadvantage, and tended in itself to dictate withdrawal to what it was hoped would be some firm rallying point; but as the need at least to delay the enemy’s progress was imperative, it might have been expected that all means to this end would have been used. The road from Jitra southward had presented many opportunities for ambushes, and outflanking tactics to counter those employed by the Japanese. By such means they might have been made to pay heavily for their impetuous actions, and to proceed with caution and thus at a reduced speed. Effective counter-initiative might indeed have thrown their advance seriously out of gear. It is now known that the commander of the 5th Japanese Division, pursuant of the fundamental principle of the Japanese Army in the campaign that the British forces must be given no respite, had ordered his frontline units to attack without losing time in arranging liaison and cooperation with each other, and to disjoint the British chain of orders as much as possible. To counter such tactics required, however, well-trained and well-led troops, fighting with dash and determination; and as has been

shown General Heath had all too few of them under his command. General Bennett’s emphasis in cables to Australia on the need for additional “quality” troops was underlined by this situation.

In the losses of men and materials which it involved, the disaster at Slim River far more than offset the value of the reinforcements which had reached Singapore on the 3rd January, and seriously prejudiced prospects of later resistance. To the Australians preparing to defend Johore, it gave urgent warning. The 11th Division had ceased to exist as an effective formation. Time, such as had existed in the easy-going, pre-war days in Malaya, was necessary to concentrate and deploy forces for the next stand. The outcome of the Battle of Slim River, and enemy moves in other directions, showed that time was running very short indeed.