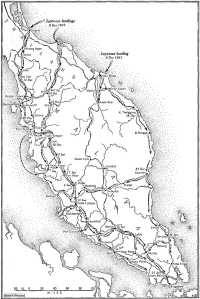

Chapter 13: To Singapore Island

The Japanese had bitten deeply into the left flank of Westforce in the battle of Muar. With two divisions deployed from the trunk road and railway to the coast, General Yamashita was able to apply to a greater extent the strategy and tactics characteristic of his campaign. Displaying extreme mobility, his forces continued to make swift and unremitting use of the initiative they had gained. General Percival’s forces were now being forced from the northern half of Johore, though that State was their last foothold on the Malayan mainland. The Japanese were stimulated by victory; their opponents were suffering the physical and psychological effects of withdrawal. Already Australian troops – the 27th Brigade – were sharing the loss and exhaustion imposed upon the III Indian Corps since the beginning of the struggle by constant fighting by day and movement by night.

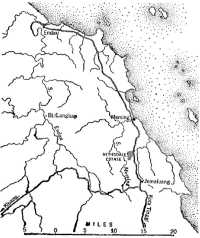

To the east, Mersing, extensively prepared for defence on the ground that it offered a tempting back-door approach to Singapore Fortress, had been comparatively little affected at this stage; but, as shown, the likelihood that it would be attacked had resulted in the 22nd Brigade Group being kept there, and had prevented the Australians from being employed as a division in resisting the enemy’s main thrust. Because of the Japanese possession of Kuantan and their progress in that and other sectors, the brigade had begun early in January to prepare to meet attack from the north and north-west rather than to resist a landing. Particular attention was paid to the Sungei Endau area and north of it. The river, with its tributaries, offered means of enemy approach in shallow draught vessels to the road running across the peninsula from Mersing, through Jemaluang, Kluang and Ayer Hitam to Batu Pahat. An Endau force was formed on 7th January, with Major Robertson,1 of the 2/20th Battalion, in command. It comprised one company of the 2/19th Battalion and one of the 2/20th Battalion, the anti-aircraft platoon of the 2/18th, and a number of small vessels under command.

Enemy infiltration of the area was soon evident, for during the morning of the 14th a reconnaissance patrol saw thirty Japanese soldiers crossing the Sungei Pontian, about 15 miles north of Endau, oddly clad in steel helmets, black coats and khaki shorts. Next day Endau was bombed and machine-gunned, and a party of Japanese riding bicycles was engaged eight miles north of the Sungei Endau by a platoon led by Lieutenant Varley, son of the commander of the 2/18th Battalion, which had been sent forward for the purpose.2 Both Endau and Mersing were attacked

from the air on the 16th. When, on the 17th, it became apparent that the Japanese were gathering in the Endau area in strength, Brigadier Taylor decided that the Endau force had fulfilled its role, and ordered its withdrawal. Before this had been completed the area was again attacked by Japanese aircraft.3 Because these attacks suggested some major move in the area, bridges on the way from Endau to Mersing were demolished and the road was cratered.

General Heath visited Brigadier Taylor’s headquarters at Mersing on 18th January, and it was decided at a conference that the road leading south from Jemaluang through Kota Tinggi to Singapore Island, rather than defence of Mersing, must be considered vital – another indication of the concern being felt about attack from the flank and rear. It was also decided that the garrison being maintained at Bukit Langkap, west of Mersing on the Sungei Endau, must be reduced to strengthen Jemaluang. The new formation to be known as Eastforce was to be commanded by Taylor under Heath’s control as from 6 a.m. on 19th January. It would comprise the 22nd Australian Brigade Group and all troops and craft in the MersingKahang-Kota Tinggi areas.

Its Australian components were the 2/18th and 2/20th Battalions, the 2/10th Field Regiment, the 2/10th Field Company, and the 2/9th Field Ambulance. Also included at this stage were the 2/17th Dogras, the Jat Battalion (amalgamated 2nd Jats-1/8th Punjabs), two companies of the Johore Military Forces, and the Johore Volunteer Engineers.

Patrols reported a gradual enemy approach to Mersing in the next two days, and the 2/20th Battalion area was under frequent air attack. During the morning of the 21st a patrol led by Lieutenant Ramsbotham4 ambushed a party of Japanese near the north bank of the Sungei Mersing, and killed a number of them. The others attempted a flanking move, and entered a minefield. Though the mines had become immersed in water from

heavy rains, and failed to explode, the Japanese were disposed of by machine-gun, mortar and artillery fire. In the afternoon a concentration of Japanese in the same locality was successfully dealt with by the 2/10th Field Regiment’s guns.

An attempt was made early on 22nd January by a company of Japanese to capture the Mersing bridge. This, however, had been well wired, and the attackers wilted under concentrated mortar and machine-gun fire. A section of the 2/20th Battalion crossed the river and machine-gunned enemy posts, and houses in which the Japanese had hidden. Artillery which ranged along the road completed the task, and the rest of the enemy force moved westward. Enemy posts and concentrations elsewhere in the Mersing area were pounded by the Australians’ guns, for which good fields of fire had been provided as a result of the evacuation of civilians on the outbreak of war with Japan. In keeping with the withdrawal policy laid down, Taylor moved his headquarters and the 2/18th Battalion less a company back to the Nithsdale Estate, 10 miles north of Jemaluang. The 2/10th Field Regiment maintained effective fire throughout the day, and the move was completed without interference during the night. The 2/20th Battalion was left covering the approach to Mersing.

–:–

On the civil front meanwhile the Governor, Sir Shenton Thomas, had responded to complaints that the civil administration was failing to meet the demands of war. In a circular issued to the Malayan civil service in mid-January he declared:–

The day of minute papers has gone. There must be no more passing of files from one department to another, and from one officer in a department to another. It is the duty of every officer to act, and if he feels the decision is beyond him he must go and get it. Similarly, the day of letters and reports is over. All written matter should be in the form of short notes in which only the most important matters are mentioned. Every officer must accept his responsibility to the full in the taking of decisions. In the great majority of cases a decision can be taken or obtained after a brief conversation, by telephone or direct. The essential thing is speed in action. ... Officers who show that they cannot take responsibility should be replaced by those who can. Seniority is of no account. ...

On this the Straits Times commented: “The announcement is about two and a half years too late,” adding “but no matter. We have got it at last.” It would, however, have required a staunch faith in miracles to entertain the idea that habits engendered by Malaya’s venerable system of government could thus be changed overnight.

–:–

A further exchange of cables between the British and the Australian Prime Ministers had again indicated their differences in outlook. Replying on 18th January to Mr Churchill’s cable of the 14th about the withdrawal in Malaya, Mr Curtin pointed out that Australia had not expected the whole of Malaya to be defended without superiority of seapower. On the contrary, the Australian Government had conveyed to the United Kingdom Government

on 1st December 1941 the conclusion reached by the Australian delegation to the first Singapore conference that in the absence of a main fleet in the Far East the forces and equipment available in the area for the defence of Malaya were totally inadequate to meet a major attack by Japan. There had been suggestions of complacency with the present position which had not been justified by the speedy progress of the Japanese. Curtin reminded Churchill that the “various parts of the Empire ... are differently situated, possess various resources, and have their own peculiar problems...”

To this Churchill replied first with a review of his war strategy in which he said he was sure that it would have been wrong to send forces needed to beat General Rommel in the Middle East to reinforce the Malayan Peninsula while Japan was still at peace. He added that none could foresee the series of major naval disasters which befell Britain and the United States in December 1941. In the new situation he would have approved sending the three fast Mediterranean battleships to form, with the four “R’s” and the Warspite, just repaired, a new fleet in the Indian Ocean to move to Australia’s protection, but

I have already told you of the Barham5 being sunk (Churchill added). I must now inform you that the Queen Elizabeth and Valiant6 have both sustained underwater damage from a “human torpedo” which put them out of action, one for three and the other for six months.... However, these evil conditions will pass. By May the United States will have a superior fleet at Hawaii. We have encouraged them to take their two new battleships out of the Atlantic if they need them, thus taking more burden upon ourselves. We are sending two, and possibly three, out of our four modern aircraft carriers to the Indian Ocean. Warspite will soon be there, and thereafter Valiant. Thus the balance of seapower in the Indian and Pacific Oceans will, in the absence of further misfortunes, turn decisively in our favour, and all Japanese overseas operations will be deprived of their present assurance. ...

But Curtin, while appreciative, still was not reassured. “The long-distance program you outline is encouraging, but the great need is in the immediate future,” he replied on the 22nd. “The Japanese are going to take a lot of repelling, and in the meantime may do very vital damage to our capacity to eject them from the areas they are capturing.”

The immediate future as General Wavell saw it was reflected in a cable which he had sent to General Percival on 19th January:–

You must think out the problem of how to withdraw from the mainland should withdrawal become necessary (he said) and how to prolong resistance on the Island. ... Will it be any use holding troops on the southern beaches if attack is coming from the north? Let me have your plans as soon as possible. Your preparations must, of course, be kept entirely secret. The battle is to be fought out in Johore till reinforcements arrive and troops must not be allowed to look over their shoulders. Under cover of selecting positions for the garrison of the Island to prevent infiltration of small parties you can work out schemes for larger forces and undertake

some preparation such as obstacles or clearances but make it clear to everyone that the battle is to be fought out in Johore without thought of retreat. ...

Reporting the situation to Churchill, Wavell said that the number of troops required to hold the island effectively probably was as great as or greater than the number required to defend Johore. “I must warn you,” he added ... “that I doubt whether island can be held for long once Johore is lost.”

Next day General Percival sent to Generals Heath, Bennett, and Simmons (the Singapore Fortress Commander) a “secret and personal” letter, with instructions that it should be shown only to such senior staff officers and column commanders as they might think should see it. In this Percival said that his present intention was to fight for the line Mersing-KluangBatu Pahat, on which was situated three important airfields, and on which the air observation system was based. He outlined a plan, however, to come into operation if withdrawal south of this line and to Singapore Island became necessary. It provided that there would be three columns – Eastforce, Westforce, and 11th Indian Division – falling back respectively on the Mersing road, the trunk road, and the west coast road to Johore Bahru. The movements of the columns would be coordinated by the III Corps, which would establish a bridgehead covering Johore Bahru through which they would pass on to the island. Selected positions would be occupied on each road, and ambushes laid between them. The positions and sites were to be reconnoitred and selected immediately. With this letter therefore Percival set afoot provisional measures for the abandonment of the Malayan mainland.

Also on 20th January General Wavell again visited Singapore. There he came to the conclusion that General Percival’s forces would have to fall back to the Mersing-Kluang-Batu Pahat line, and that there was every prospect of their being driven off the mainland. He found that despite the instructions he had given for preparation of defences in the northern part of Singapore Island, very little had been done to this end. He told Percival to endeavour to hold the enemy on the mainland until further reinforcements arrived; but to make every preparation for defence of the island. After discussing dispositions for the latter purpose, he ordered that the 18th British Division, as the freshest and strongest formation, be assigned to the part of the island most likely to be attacked; that the 8th Australian Division be given the next most dangerous sector; and that the two Indian divisions, when they had been re-formed, be used as a reserve. Percival contended that the main attack would be on the north-east of the island, from the Sungei Johore, and favoured placing the 18th Division there, and the Australians in the north-west. Although Wavell thought this attack would be on the north-west – in the path of the enemy’s main advance down the peninsula – he accepted Percival’s judgment on the ground that he was the commander responsible for results, and had long studied the problem.

At this time also the question of Australian representation on the staff of ABDA was under discussion. In Wavell’s plan for the organisation of his ABDA headquarters the only provision for a senior Australian officer was as deputy intendant general in the administrative branch. In a statement to the Australian Advisory War Council on 19th January on this subject, Mr Curtin said that this was another sidelight on the attitude of the United Kingdom towards Australian participation in the higher direction of the war in an area in which Australia was vitally concerned. Attached to the statement was a comparison of the military careers of Generals Wavell and Blamey, Commander-in-Chief of the Australian forces in the Middle East.7 Curtin continued:–

When General Wavell was Commander-in-Chief in the M.E. his successes were mainly against Italians or black troops in Abyssinia, East Africa and Libya. He suffered defeats by the Germans in Libya in April 1941 and again in June 1941, when he launched a counter-offensive. He also was defeated by the Germans in the Greek campaign, though General Blamey conducted the actual operations of extricating the British forces.

Despite the implications of this passage, Curtin added:–

There can be no question of criticising this appointment, but apparently no Australian can expect consideration for a high command even though Australia may supply the largest share of the fighting forces as in the case of Greece and Malaya.

Curtin went on to say that exclusion of Australian officers from senior posts in ABDA was unjustifiable if Australia was to have three divisions and possibly a fourth in the area. A vital principle was at stake as much as the question of a share in the political higher direction.

It is my view (concluded Mr Curtin) that the GOC, AIF, should either be given a high place on the staff of the Supreme Commander or a Field Command in an area where the AIF is wholly concentrated under his operational control, subject only to the Supreme Commander. Alternatively, he should be brought back to Australia and be given a suitable post.

The Council concluded that the position allotted on Wavell’s staff was “quite unacceptable”, and that “the GOC, AIF, should be given a status that will ensure he is fully consulted in regard to all operational, administrative, and other plans insofar as they affect the AIF.” It recommended that representations be made to the British Government on these lines.

The War Cabinet endorsed this conclusion.8 On 21st January it had before it a proposal which carried the question of Australian representation into a higher sphere. This had come from the Dominions Office, and had been rejected by the Advisory War Council. It was to the effect that a Far Eastern Council be established in London on a Ministerial plane, presided over by Mr Churchill, and including a representative of Australia. Its function would be to “focus and formulate views of the represented Powers to the President”, whose views would also be brought before the Council. Again endorsing the Advisory War Council’s attitude, the War Cabinet decided to reply that both these bodies unanimously disagreed with the proposal. The Far Eastern Council would be purely advisory, and quite out of keeping with Australia’s vital and primary interest in the Pacific sphere. It was desired that an accredited representative of the Australian Government should have the right to be heard in the British War Council in the formulation and direction of policy, and that a Pacific War Council be established at Washington, comprising representatives of the Governments of the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, China, the Netherlands and New Zealand; this body to be a council of action for the higher direction of the war in the Pacific.

–:–

On the morning of 22nd January, after hope had been lost of rescuing Colonel Anderson’s column at Parit Sulong, General Bennett ordered the 53rd Brigade to hold its positions behind the Bukit Pelandok defile, on his left flank, at least until midday on the 23rd, to help the remnants of the column to escape and enable other positions to be organised. The causeway between the defile and Yong Peng was to be held till 7 p.m. on the 23rd. Yong Peng was to be evacuated by midnight. Anti-aircraft guns were concentrated along the main road and railway and air cover for the withdrawal from Yong Peng was arranged. During the 22nd, however, Bennett received a report that the brigade was falling back, and sent orders that it must stand fast. He was informed also that resistance at Batu Pahat showed signs of cracking. His diary for the day concluded:–

Held usual Press conference today. Same correspondents present, representing British, American and Australian press. They were waiting for me just as I sent the Bakri men my last message. I told them the story but am afraid my chagrin and disappointment made me somewhat bitter and critical.9

After a conference on the morning of 23rd January General Percival gave orders implementing the first stage of the plan for withdrawal to Singapore Island which he had outlined in his secret letter on the 20th. These provided that Westforce would come under General Heath’s command as soon as the last troops had been withdrawn south of the Yong Peng road junction, and that the 53rd British Brigade, to move back through the 27th Australian Brigade, should revert at Ayer Hitam to General Key’s (11th Indian Division) command. The general line Jemaluang–Kluang–Ayer Hitam–Batu Pahat was to be held, and there was to be no retraction from it without his permission. He had in mind that positions farther south were not good, and also the pending arrival of the rest of the 18th British Division. For this it was highly desirable that the enemy should be kept from the mainland airfields which lay behind the new defence line. A further concern was the growing strength of the Japanese near Mersing, and the possibility of another east coast landing.

General Bennett had assigned to the 2/30th Battalion the task of holding Yong Peng until first light on the 23rd, and of then covering Ayer Hitam from the north. Two of its companies were to remain at Yong Peng until the 53rd Brigade had completed its withdrawal. As the first stage of this movement was in progress the appearance of some of the newly-arrived Hurricanes in the sky seemed to the Australians to promise the air power so conspicuously lacking hitherto in Malaya, as it had been in Greece and Crete where their comrades had fought. “You bloody beauts!” they fervently exclaimed. Perhaps it was fortunate that they did not know that of the two airfields on the mainland which had remained in use by defending aircraft after the Japanese reached Muar, the Kahang airfield had been evacuated on the 22nd.

On the railway on 23rd January the 22nd Indian Brigade had taken up positions to guard the Kluang airfield, with the 2/18th Garhwal to their north at Paloh, where a road ran south-west to the main road near Yong Peng. Under attack the Garhwalis withdrew, and their headquarters became separated from their rifle companies. Lacking this contact, the companies continued their withdrawal and reached Kluang that night – by which time the Kluang airfield also had been abandoned by the air force. The 8th Indian Brigade, on the main road covering the approach from the north, held off the enemy during the day and at night passed through Yong Peng. It was then transported to the Rengam area, on the railway line south of Kluang.

In the course of its withdrawal from the road between Yong Peng and Bukit Pelandok the 53rd Brigade was repeatedly attacked by enemy tanks and infantry. Bridges on the causeway were blown before the movement had been completed. Two companies of the Loyals were forced into swamp through which the causeway ran, and became isolated, for the time being, with the result that the battalion was badly depleted when, as had been arranged, it came under command of the 27th Brigade, and was posted to the rear of the 2/30th Battalion. The 53rd Brigade reached Ayer

Hitam on 24th January, and was thereupon sent to Skudai. The task undertaken by the Japanese Guards Division in the Muar area now had been completed.

Early on the 24th, when the last of the southward-bound units had passed through the 2/30th Battalion and the Loyals, the Yong Peng bridge was blown up and, Percival related, “we breathed again”.10 The dangerous isolation of Westforce resulting from the collapse of resistance in the Muar area had been overcome, and the front was relatively straight from coast to coast. But as will be shown, its western end was fraying dangerously; and the Japanese were active also at the eastern end.

The 44th Indian Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Ballentine,11 with attached troops and 7,000 Indian reinforcements, had reached Singapore on 22nd January, but as Percival considered it as little fitted for battle as the 45th Indian Brigade he kept it on the island. The reinforcements, still less trained and with very few NCOs among them, were drafted sparingly to units. On 24th January there arrived the 2/4th Australian Machine Gun Battalion,12 comprising 942 all ranks, and 1,907 largely untrained reinforcements for other units.13 Some of these had defective rifles. The machine-gunners were allotted accommodation in the Naval Base area and ordered to prepare machine-gun positions on the north coast of the island. Thus the influx contributed little to the defence of the mainland, and the value of the newly-arrived Indian infantry for the defence of the island was considered uncertain.

Batu Pahat, where another threat to the defending forces was now developing, was, like Muar, a small coastal port, on the south bank of an estuary crossed by a ferry. One road connected it to Yong Peng, and one to Ayer Hitam, also on the trunk road. Another ran down the coast, turned inland at Pontian Kechil, and joined the trunk road at Kulai near

Johore Bahru, capital of Johore. Thus the area offered scope to the Guards Division for further influencing the course of the campaign. Nishimura’s hitherto concealed I/4th Battalion had engaged in minor encounters with the British forces at Batu Pahat from 18th January onward. A sweep by the British Battalion and the Cambridgeshires on the 21st to clear the Bukit Banang area south of the town was unsuccessful, and Japanese troops were encountered north-east of the town also. Generals Heath and Key visited Brigadier Challen during the day, and told him that he must not only hold the area, but keep open the road to Ayer Hitam. Soon after they had gone, it was found that the Japanese had placed a block across it. The road was temporarily cleared next day by the 5/Norfolks from Ayer Hitam and the British Battalion from Batu Pahat; but a British field battery was attacked at a point on the coastal road about five miles south of Batu Pahat, its commander was killed, and a gun was abandoned. On the 23rd the Ayer Hitam road was again blocked, and the 5/Norfolks, who were to have moved along it from Ayer Hitam into Batu Pahat to reinforce the garrison, were sent via Skudai and Pontian Kechil instead.

Challen now feared that his 15th Brigade would find itself in a situation similar to that which had developed at Bakri. Unable to get instructions because his wireless had failed, he decided to withdraw from the town to a position in depth on the coastal road between Batu Pahat and Senggarang. Communication was restored while this movement was in progress, and it was reported to the 11th Division. Concerned that such a withdrawal would give the enemy access to the left flank and communications of Westforce and endanger the new defence line, Key ordered it to be cancelled, and Batu Pahat to be reoccupied. This order was confirmed by Heath after consultation with Percival. Although the Japanese had penetrated the town to some extent, and concealed themselves in houses, Challen’s men re-entered it and took up defensive positions for the night.

–:–

At this ominous stage of events in Malaya, Japanese forces had overcome (on 23rd January) the Australian garrison at Rabaul, administrative centre of the Mandated Territory of New Guinea.14 The enemy had thus extended his far-flung battle line east of the ABDA area, and made his first assault on territory under Australian control. Within the ABDA area Japan had used the middle prong of a trident thrust to the south to occupy Balikpapan (Dutch Borneo), also on the 23rd, and Kendari (Celebes) on the 24th. Disturbing reports had reached General Wavell of Japanese progress in Burma. The day after the fall of Rabaul he received notification that his responsibilities had been extended to the defence of Darwin and a strip of the adjoining coastal area considered necessary for this purpose.15 Taking this adjustment into account, the total number of men in the Australian land forces in the ABDA area,

including “Sparrow Force” on Timor Island and “Gull Force” on Ambon Island, was 34,370. Six squadrons of the Royal Australian Air Force were also in the area – three in Malaya, one on Ambon, and two based on Darwin and Timor – and a small advanced party of I Australian Corps reached Java on 26th January. These considerations gave further weight to the complaint that Australia was inadequately represented in the higher direction of ABDA and on Wavell’s staff.

Reporting on 24th January to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the outlook in his command, Wavell said that the only possible course was to use such limited resources as were available to check the enemy’s intense offensive effort as far forward as possible by hard fighting, taking offensive action whenever possible. This policy would involve heavy losses by land, sea and air, and ability to make further efforts would depend on these losses being rapidly made good.

–:–

In Malaya, 24th January was another fateful day. Heath now commanded a front on which Eastforce was in contact with the enemy in the Mersing area; Westforce, with the 9th Division (8th and 22nd Indian Brigades) on the railway covering Kluang and the 27th Australian Brigade covering Ayer Hitam, was temporarily disengaged; and the 11th Indian Division had the 15th Brigade precariously situated at Batu Pahat, the 28th Brigade at Pontian Kechil, and the 53rd Brigade on its way from Skudai to Benut, on the west coast road between Pontian Kechil and Batu Pahat. During the day Percival issued an outline plan indicating the method to be adopted in the event of withdrawal to Singapore Island, but without a time-table. The withdrawal by the 2/18th Garhwal Regiment from Paloh on 23rd January had created a dangerous situation, and the 8th Indian Brigade gained little respite at Rengam before it was ordered forward to enable the 22nd Brigade to counter-attack on the 24th. It was planned that the 5/11th Sikhs, commanded by Lieut-Colonel Parkin,16 should swing to the west and come in on the line at Niyor, the junction of a branch road from the railway to the road linking Kluang and Ayer Hitam. However, as progress of the rest of the brigade up the railway was slow, the Sikhs were ordered to reach it at an intermediate point. Lacking a map of the area, Parkin kept to the route originally ordered, but his battalion encountered a road-block and formed a perimeter for the night of the 24th–25th.

On the west coast the attempt to reinforce the 15th Brigade was resumed at dawn on the 24th, and the 5/Norfolk, having moved up the coast road, reached it soon after 7 a.m. Street fighting was in progress at Batu Pahat, with a Cambridgeshire company holding a position in the centre of the township. The Norfolks were ordered to occupy a rise overlooking the exit to the coast road, but the supporting artillery was able to give little aid because ammunition lorries had been omitted by error from the reinforcing convoy. By nightfall the battalion was still short of its objective.

Pressure from north-east of the township increased next morning, and a reconnaissance report indicated that an enemy force (presumably Nishimura’s I/4th Battalion) was concealed near Senggarang. It was therefore in a position to cut Challen’s line of communication, as Nishimura had planned to do. With his fears of becoming isolated thus confirmed, Challen again sought permission to withdraw, but was told that a decision could not be given until after a conference which General Percival was to hold during the afternoon. Meanwhile the 53rd Brigade, consisting at this stage of the 6/Norfolk and the 3/16th Punjab, each of only two companies, had reached Benut. It took two squadrons of the 3rd Cavalry and a field battery under command, and Brigadier Duke sent the Norfolks forward with armoured car and artillery support, to leave a garrison of one company at Rengit and then press on to Senggarang. The head of the column, less the company left at Rengit, reached Senggarang at 8 a.m. but the Japanese in the area successfully attacked its tail half a mile south of the village, and established a series of road-blocks.

In the central sector heavy air attacks on the crossroads at Ayer Hitam, where the 2/30th Australian Battalion and the 2/Loyals were stationed, had made it obvious that the Japanese would press home their advantage. The roar of demolitions along the road had indicated that the 2/12th Australian Field Company was doing its best to make this as difficult for them as possible. The company had been hard at work during the whole of the struggle from the time of the Gemencheh ambush, and as occasion arose its members shared in the fighting.

Viewing this now familiar pattern of threat and compulsion, Percival decided, after his conference in the afternoon of 25th January with Heath, Bennett, and Key, that the 15th Brigade should immediately link with the 53rd Brigade in the Senggarang area; Westforce to withdraw at night to the general line Sungei Sayong Halt-Sungei Benut on the railway and trunk road respectively. This line was to be held at least until the night of 27th–28th January, and subsequent withdrawals were to be made to positions specified in advance. Eastforce and the 11th Division were to move in conformity with Westforce, under orders from Heath. Bennett was to hold a good battalion in reserve, whenever possible, to deal with the danger of penetration from the Pontian Kechil area. The 2/Gordon Highlanders, from Singapore Island, were to relieve the Loyals.

There remained a slender hope that the Japanese advance might be stemmed in southern Johore, but withdrawal to Singapore Island was an insistent probability. With this in mind Heath had selected areas for delaying action on a series of lines to the rear. He gave maps to Key and Bennett on which these lines had been marked, with tentative times for withdrawals; and he subsequently ordered Eastforce to withdraw to Jemaluang. Key ordered the weak 53rd Brigade to clear the road from Rengit to Senggarang by dawn on the 26th, and 15th Brigade to reach Benut by the 27th; Challen to take command of the troops at Senggarang and Rengit as he reached them. Bennett issued orders for the movement

required of Westforce. On the basis of Heath’s maps he issued that day or the next – records differ on this point – an outline withdrawal plan. This required that the 9th Division should withdraw down the axis of the railway and the 27th Brigade down the trunk road, denying successive positions to the enemy. As there was no road from a few miles south of Layang Layang to Sedenak down which the 9th Division might withdraw its artillery and transport, it was necessary for this to be sent from Rengam by estate roads to the 401-mile post on the trunk road while it was still covered. Between Rengam and Sedenak the division would be restricted to such equipment as could be manhandled, and would have to make its way on foot.

During the afternoon of the 25th, Brigadier Taylor held a conference of his commanding officers. The day before, when Kluang airfield was endangered and he was ordered to destroy Kahang airfield, he had moved his headquarters to a point east of Jemaluang. He now issued orders for his headquarters to be established on the Kota Tinggi road south of Jemaluang, and for the 2/20th Battalion to withdraw from its strongly prepared positions to Jemaluang crossroads that night. The enemy, however, was to be made to pay for the concession. Lieut-Colonel Varley, of the 2/18th Battalion, gained approval of a plan for a large-scale ambush in the Nithsdale and adjacent Joo Lye Estates. This would operate on the withdrawal of the 2/20th, and after carrying it out the 2/18th would pass back to a position on the Kota Tinggi road. Bombing of Mersing during the day was heavy, but the 2/20th made its withdrawal with precision, and the 2/18th meanwhile took up its ambush positions.

In the railway sector on the 25th the Sikhs were preparing to advance on Niyor when they received orders to withdraw to Kluang.. Parkin decided that the attack should be made to secure freedom for this movement. In the ensuing engagement the Japanese were routed with bayonets, and the withdrawal was then made with relative ease. The rest of the 22nd Brigade was engaged during the day, but with the headquarters and headquarters company of the Garhwal, who rejoined it during the afternoon, withdrew at night (25th–26th) to Rengam, where the Sikhs rejoined next morning. The same night the 8th Brigade was withdrawn to Sungei Sayong Halt.

Fighting had occurred meanwhile on the trunk road sector (where as is now known the main body of the Japanese 5th Division was being employed). The 2/30th Battalion (Colonel Galleghan) and the 2/Loyals (Colonel Elrington) were covering the northern approach to the vital road junction at Ayer Hitam. “A” Company (Major Anderson) of the 2/30th, a “B” Company platoon (Lieutenant Cooper17), a few newly-arrived reinforcements, and a detachment of mortars (Sergeant McAlister18) occupied a hill position on the right, 4,000 yards north of the junction,

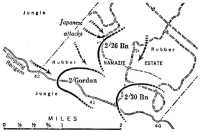

Ayer Hitam, 24th–25th January

with the Loyals forward astride the road. Between these positions and the rest of the battalion was the Sungei Sembrong and an area of swamp, scrub, and jungle. The area offered good fields of fire. Anderson’s men took full advantage of grass and bracken on their hill for concealment from air observation, and dry rations were passed from hand to hand among them with a minimum of movement.19 The battalion maintained these precautions for two days, despite a growing feeling that it might be better to be bombed than to be driven mad by mosquitoes. On 24th January the Loyals came down the road under enemy pressure, and on Brigadier Maxwell’s instructions were redisposed by Galleghan with “A” Company under Anderson’s command. Despite his senior rank, Elrington elected to remain with his men and accept direction, on the ground that Anderson was more familiar than he with the local situation.

Heavy tropical rain added to the discomfort of the troops on the 25th. Japanese aircraft were overhead trying to locate them and destroy the bridge over the river. Patrol actions, in which Sergeant Russell20 of the 2/30th was outstanding, commenced at dawn and gradually developed into general fighting in the forward area, with heavy fire against the defenders and the bridge. Near mid-afternoon attacking troops were led by an officer bearing a large Japanese flag. He was shot down, and so were a second and a third who attempted to carry it forward. Beaten back by Australian small arms and mortar fire, the Japanese abandoned their emblem. In the latter part of the afternoon the Japanese made a two-company attack on the right flank of Anderson’s company but were similarly repulsed by the Australians and the Loyals, and left many casualties lying on the ground. A second attack in greater strength became bogged down in swamp and under mortar fire. Then, as light was failing, the enemy heavily attacked a company of Loyals west of the road. The Loyals held on until some of them were in hand-to-hand conflict, but were outnumbered, and after suffering heavily were forced from their positions.

The forward left flank was thus exposed, but as Japanese came on to the road and could be dimly seen by a platoon under Lieutenant Brown,21 which occupied the top of a cutting, the platoon’s fire forced them to ground. In retaliating the Japanese used “a queer weapon which emitted red balls of flame and much smoke to little effect”.22 Though they tried later to rush the position and mounted machine-guns, the platoon held them off with mortars, Bren guns and grenades. The rest of the battalion, however, and the artillery positions behind Ayer Hitam, were now under intensive shelling and bombing. As the brigade was due to withdraw that night, the battalion was pulled back. The Japanese having gained the road. the withdrawal from the forward positions was made partly through swamp and abandoned rice-fields, in darkness and under persistent enemy machine-gun fire. Although they had to struggle through mud at times waist-deep, the stretcher-bearers succeeded without exception in their tasks. Captain Peach,23 the adjutant, who had brought forward the withdrawal order, succeeded under similar conditions in conveying it to the Loyals and returning to the bridge over the Sungei Sembrong. At 9 p.m., when he was assured that only the enemy were forward of it, he ordered its demolition. Captain Duffy successfully commanded a rearguard partly consisting of his (“B”) company and some Loyals, and covering 25-pounder fire was given by the 30th Battery of the 2/15th Field Regiment. Although the Japanese had been made to pay heavily, the casualties of the 2/30th Battalion were only four killed and twelve wounded or missing. The battalion took up during the night a position it had been assigned at the 41-mile post, five miles south of Simpang Rengam. The Loyals were withdrawn to Singapore Island and replaced as had been arranged by the Gordons, who occupied a position at Sungei Benut (milestone 48i) with the 2/26th Battalion at milestone 44½.

In the west, Brigadier Challen succeeded, with the aid of a bombardment by the river gunboat Dragonfly, in withdrawing his forces during the night of 25th–26th January from Batu Pahat. Although he had been ordered by General Key to reach Benut by the 27th, he discovered at Senggarang on the morning of the 26th that the enemy had occupied the bridge and near-by buildings at the southern end of the village. The Cambridgeshires cleared the buildings, but were held up by enemy fire along the swamp-lined road leading to the Japanese blocks. Under attack also from the air on artillery positions and transport, successive attempts to force a way south were unavailing.

Thus Brigadier Duke (53rd Brigade) found himself called upon as at Bukit Pelandok, though with a depleted brigade, to conduct a relieving operation. On orders from Key, who visited his headquarters at 10.30 a.m.

on the 26th, he mustered and sent from Benut at 12.30 p.m. a column under a British territorial officer, Major C. F. W. Banham, of artillery, armoured cars, carriers and a detachment of infantry, with orders to deploy at Rengit. The column nevertheless was in close formation when it ran into a road-block a little north of the village, and was almost wiped out. Only Banham’s carrier broke through and continued on its way. After negotiating the succession of blocks established by the enemy, it dramatically toppled over the last one and reached Senggarang at 2 p.m. just as Brigadier Challen was about to launch a full-scale attempt to break through to the south.

On Banham’s report of the obstructions he had encountered, Challen decided that it would be useless to attempt to get his guns and vehicles to Benut. He therefore ordered them to be destroyed, the wounded to be left under the protection of the Red Cross, and the remaining troops to make their way across country past the enemy.24 That night, after having blocked the road south of Rengit, the Japanese captured that village. About 1,200 of Challen’s men, guided by an officer of the Malayan police force, moved east of the road from Senggarang and reached Benut next afternoon. Others, led by Challen, moved west of the road, and halted at a river during the night of the 26th–27th. Challen was taken prisoner while he searched for a crossing. Lieut-Colonel Morrison, of the British Battalion, thereupon took command, led the men to the coast west of Rengit, and sent an officer to Pontian Kechil to seek aid. General Percival decided when he learned of their plight to evacuate them by sea. By using two gunboats (Dragonfly and Scorpion) and a number of small craft from Singapore, this daring and difficult task was carried out during successive nights, and completed on 1st February.

In dislodging and dispersing the 15th Brigade, the Japanese Guards Division had carried out a series of adventurous enveloping movements. Despite the obstacles presented by rivers, jungle, and swamp, and the fact that units went astray from time to time, the movements were generally well coordinated. The 5th Infantry Regiment lost the equivalent of a battalion in the fighting between Muar and Batu Pahat, but the division’s total losses were small in comparison with the results which it achieved in overcoming resistance in the Batu Pahat area and influencing the course of the struggle on the mainland generally.

Concurrently with the withdrawal of the 15th Brigade from Batu Pahat, enemy forces were increasingly active at the eastern end of the Johore defence line. A convoy which comprised four cruisers, one aircraft carrier, six destroyers, two transports, and thirteen smaller craft was sighted 20 miles north-east of Endau by Australian airmen at 7.45 a.m. on 26th January, but their warning signal was not received. Thus it was only when they returned to base on Singapore Island at 9.20 a.m. that the news reached Air Headquarters.25 Only thirty-six aircraft were available

as a striking force. As it was thought that the Japanese vessels would be in shallow water by the time they could be attacked, the Vildebeestes in the force were rearmed with bombs instead of torpedoes which they normally carried. The bomber group in Java was ordered to send all available bombers to Endau, and ABDA Command was asked for American bombers to supplement the endeavour. It was not until early in the afternoon that the first wave of the local force (9 Hudsons and 12 Vildebeestes) took off, escorted by 23 fighters. Heavy opposition was encountered in the target area, which was reached about 3 p.m., but the attackers were able to avail themselves of cloud cover. Direct hits were made on two transports and a cruiser, and bombs were dropped among troops in barges and on the beaches, for a loss of 5 Vildebeestes.

About 5 p.m., when the second attack was made, by 9 Vildebeestes and 3 Albacores, with 12 fighters, the clouds had disappeared, and the damage inflicted upon the enemy was slight, but 5 more Vildebeestes, 2 Albacores and a fighter were lost. Five Hudsons from Sumatra returned to Singapore after bombing troops and landing-craft in the Sungei Endau during the evening. Early next morning two obsolescent destroyers – Vampire (Australian) and Thanet – sent from Singapore, encountered three modern Japanese destroyers. Under concentrated attack, Thanet quickly sank. Vampire, trying to cover Thanet with a smoke-screen, was next engaged, and another destroyer and a light cruiser joined in the action against her. She nevertheless succeeded in eluding the enemy, and escaped to Singapore. Thus the enemy was able to complete the landing operation. On the other hand the number of defending aircraft in service in Malaya had been reduced to near vanishing point. Not only had a high proportion of them been lost, but others had been badly damaged; two squadron leaders had been killed, and a number of the airmen had been wounded.

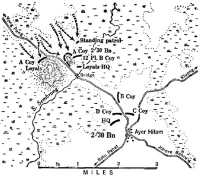

The Japanese force which landed was the 96th Airfield Battalion and its signal unit, to operate the Kahang and Kluang airfields as soon as they had been captured. This was not known when the convoy was sighted on the 26th, and, in the light also of the evidence of concentration of enemy troops from the north, it then appeared that the 22nd Brigade could expect to be attacked on a large scale. Arrangements were completed for Varley’s ambush, but with the stipulation, in keeping with the general withdrawal orders, that the troops employed in it must withdraw through the 2/20th Battalion at Jemaluang immediately the ambush had been sprung, to the section of the road to Kota Tinggi allotted to them. Captain Edgley’s26 company of the 2/18th was west of the road from Mersing, near a height known as Gibraltar Hill and where jungle growth formed a defile; Major O’Brien’s27 east of the road to the south of the defile; Captain

Nithsdale Estate, 26th–27th January

Johnstone’s28 company astride the road to the rear of these positions; and Captain Okey’s29 company in reserve. It was proposed to let about a battalion of Japanese pass the two forward companies and to come upon a block established by Johnstone’s company. Guns of the 20th and 60th Batteries of the 2/10th Field Regiment, supplementing the battalion mortars and machine-guns, would pound the trapped enemy troops at this stage, and an artillery barrage would creep forward, spreading to both sides of the road into the Nithsdale Estate, as Edgley’s men moved in behind it on to the road. After mopping up, they would then move south towards O’Brien’s company, whose task was to dispose of any Japanese who survived on its front. The success of the plan depended upon all concerned withholding fire until a sufficient number of Japanese had entered the trap. This required a degree of self-control which would severely test the training of the 2/18th Battalion.

A force estimated at 1,000 Japanese, reported to be moving from Endau to Mersing, was not expected to reach the positions until after daylight on the 27th. However, patrols had exchanged shots with a Japanese patrol in the ambush area late in the afternoon of the 26th. After dark increasing numbers of Japanese, finally estimated at battalion strength, were observed but allowed to pass into the area as arranged, despite the ideal target presented by enemy troops marching along the road in column of route. Indiscriminate enemy fire, accompanied by the noise of crackers, broke out soon after midnight, apparently intended to make the Australians disclose their positions; but their orders to hold fire were strictly observed. Lieutenant Warden’s30 platoon of Johnstone’s company was attacked at 2 a.m., and retaliated with bayonets. Although the encounter was expensive for the Japanese, it resulted also in the death of the platoon commander, and two others. An hour later, when the

pressure indicated that a large body of Japanese was engaged, the mortar and artillery fire was ordered. Varley, who for some while had been vainly trying to get through to the forward companies by telephone, succeeded at this critical stage and ordered them to carry out the agreed plan. Johnstone’s company heard a stream of shells rushing over them into the defile,31 which became a shambles. After about 20 minutes the barrage had moved far enough up the road to allow the forward companies to go into action. Soon after, Varley received a telephone message from Edgley that his company had not come into contact with the enemy, and was about to withdraw as arranged. That was the last report Varley received from him. It transpired that the company’s leading section attacked Japanese who were repairing a bridge; thereupon the Japanese fled to positions which had been hastily taken up by their force on high ground astride the road at the southern end of the defile. A two-platoon attack failed to dislodge them, and a platoon sent to their left flank was repulsed. In savage encounters, the Australians discovered that the position was strongly held, and came under an increasing volume of mortar and machine-gun fire, accompanied by grenades. Because of this, and communication difficulties, the fight was still raging when daylight came. O’Brien’s company was also engaged, though with smaller numbers of the enemy, with whom it dealt successfully. It therefore moved towards the Japanese stronghold encountered by Edgley and itself encountered severe resistance.

Meanwhile Varley found himself again cut off from line communication with his men; but at 7.45 a.m. Sergeant Wagner,32 the battalion’s Intelligence sergeant, who had gone forward through the enemy to the forward positions, provided information which enabled the artillery again to concentrate on its target with notable results. Varley then ordered Johnstone to assemble men for a counter-attack. They were about to move off, and the move by O’Brien’s company to assist Edgley’s was afoot, when a message was received from Brigadier Taylor in consequence of detailed orders he had received from Heath under the general withdrawal plan. It was to the effect that as the brigade (less its 2/19th Battalion) was responsible for holding the whole of the road back to Johore Bahru, no further troops must be committed to the action, and the companies engaged must be withdrawn to Jemaluang.

The order was reluctantly obeyed, especially as it meant leaving Edgley’s company – and to an extent O’Brien’s also – to fight their way out. The withdrawal of the battalion, including such of the forward troops as could be extricated, was covered by Okey’s company. In the final count its losses in the ambush action were found to be six officers and 92 others killed or missing; but the Japanese losses appeared to have been far heavier. Edgley’s company was subsequently reconstituted of survivors – about a platoon strong – who had made their way back to the battalion,

and others, under Captain Toose.33 A series of further movements in keeping with the withdrawal plan were made unmolested by Eastforce, commanded by Varley34 while Taylor carried out a bridgehead task to which, as will be seen, he had been allotted. Reports from men who came in after being cut off indicated that the setback imposed on the Japanese was such that they did not occupy Jemaluang until 29th January.

A Japanese account of the experiences of the Kuantan landing force (two battalions of the 55th Infantry Regiment with artillery and engineers) which made its way to the Mersing area indicates that it encountered severe difficulties in making its way from Kuantan through jungle and swamp. Men handling artillery pieces sank deep in the mire; troops ate tree roots, coconuts, and wild potatoes, and at times could find dry resting places only by climbing trees. The fighting near Jemaluang was “an appalling hand-to-hand battle”. Seriously weakened, the force withdrew towards Mersing, and strong reinforcements were sent from Kluang to Jemaluang. The 55th Infantry Regiment was then diverted to Kluang to join the main body of the Japanese 18th Division. The progress of the 5th and Guards Divisions having made unnecessary the earlier plan to land the 18th Division in the Mersing area, this formation had landed at Singora on 22nd and 23rd January and had been brought south, bringing the Japanese strength on the west of the peninsula to three divisions. Because of the terrain of Malaya and insufficient means of transporting the 18th Division’s horses by sea, these had been left behind in Canton; nor had it mechanical transport of its own; but lorries had been made available by the other formations to transport its main force from Singora to the scene of action.

In the central sector the withdrawal plan was being carried out meanwhile under varying pressure. Low-flying Japanese planes were constantly overhead, and the Gordons and the 2/26th Battalion were intensively strafed. A sheet of paper blown from the cockpit of a Japanese fighter and picked up in the 2/26th Battalion area bore an accurate sketch of the dispositions. Early in the afternoon of the 26th January snipers and machine-gunners attacked the Gordons’ forward companies. Japanese troops who then approached along the edges of the road were checked by mortar and 25-pounder gun fire. Near the close of the day, however, it was reported that the Gordons had run out of food and water and their ammunition was running short.35 Under further enemy pressure they were withdrawn, but fortunately the Japanese did not immediately seize their advantage.

In the afternoon General Heath had held a conference at which he issued a definite program for movements culminating in a withdrawal to

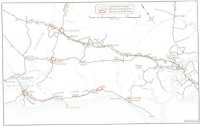

Singapore Island on the night of 31st January-1st February. General Bennett accordingly issued at 12.20 a.m. on the 27th an operation instruction to Westforce. This embodied the following schedule, which it was emphasised must be adhered to:–

Night 26th–27th January – hold present positions.

Night 27th–28th January – withdraw to line rail mile 440, road mile 44.

Night 29th–30th January – withdraw to line Sedenak road mile 32.

Night 30th–31st January – withdraw to line rail mile 450, road mile 25.

Night 31st January–1st February – On to island.

The order contained a discrepancy in that an appendix showing these stages coordinated with the movements of Eastforce and the 11th Indian Division specified the Westforce positions for the night of 27th–28th January as rail mile 437 and road mile 42.

General Barstow gave orders to the 9th Indian Division based on his interpretation of this instruction. These required the 22nd Indian Brigade to hold the foremost position on the railway till the night of the 28th–29th; the 8th Indian Brigade to hold Sedenak till the night of the 30th–31st; and the 22nd Indian Brigade to hold the next position till the night of 31st January-lst February. Barstow specified block positions to be occupied in front of each of the points the brigades were to deny, and instructed his brigadiers to coordinate the movements of their brigades by agreement. The 22nd Indian Brigade block for the 27th–28th was from the railway milestones 432 to 437. Brigadier Painter pointed out that a network of estate roads between Rengam and Layang Layang would enable this to be easily outflanked, and perhaps allow the enemy to get between the two brigades. (The roads ran through some six miles of rubber plantation separating the brigades.) He was told, however, that it was necessary to hold the area to cover the right flank of the 27th Australian Brigade’s position on the trunk road until 4 p.m. on the 28th. Barstow selected and ordered the 8th Brigade to occupy during the evening of 27th January a ridge astride the railway at milestone 439+ to the rear of Layang Layang, covering the railway and a road bridge at that point in the brigade block. The brigade accordingly moved back, and the 22nd Brigade took up its position, with the 5/11th Sikh a mile and a half south of Rengam, among the estate roads mentioned, and the rest of the brigade at rail mile 435. The Sikhs, however, were driven back during the afternoon to rail mile 434.

On the trunk road, the 27th Brigade’s positions were strafed from low altitudes36 during the 27th – especially when the 9th Division’s guns and transport came through – and concentrated shelling of the 2/26th Battalion’s area broke out in mid-afternoon. Front and flank attacks on the Australians followed, and they became heavily engaged. The Japanese

again supplemented their fire with crackers of a type known to Australians as Jumping Jacks. These, as recorded in the battalion’s narrative, “burst with a flash of coloured fire and then changed direction suddenly and would again explode”. It was noticed that one cracker would perhaps explode ten times. Apparently they were intended to affect morale, but although the absence of air support such as had been given in the withdrawal from Yong Peng was a bitter disappointment, the crackers were regarded by the Australians as a form of comic relief amid the strain of constant bombardment and fighting. Again, the fact that apparently the Australians were inflicting a far greater number of casualties on the Japanese than they themselves suffered, despite the enemy’s command of the air, was reassuring. The battalion had difficulty in breaking off the engagement for the scheduled withdrawal after dark, but eventually, with the staunch support of the 30th Battery, got back by midnight to its milestone 42 position, covering a road into the Namazie Estate, with the Gordons a little ahead of them on the trunk road to their left.

The full significance of the dispersal of the 15th Brigade after the fall of Batu Pahat had become apparent to General Percival during 27th January. He considered the remaining troops on the west coast road were not strong enough to stop the advance in that sector for long, and that the whole of his forces on the mainland were now endangered. In the evening he sent a message to General Wavell in which he said:–

A very critical situation has developed. The enemy has cut off and overrun the majority of the forces on the west coast. ... Unless we can stop him it will be difficult to get our own columns on other roads back in time, especially as they are both being pressed. In any case it looks as if we should not be able to hold Johore for more than another three or four days. We are going to be a bit thin on the island unless we can get the remaining troops back. Our total fighter strength now reduced to nine and difficulty in keeping airfields in action.

Wavell replied the same day giving Percival discretion to withdraw to the island if he considered it advisable.

At a conference early on 28th January between Percival, Heath and Bennett, a plan was adopted by which the mainland would be evacuated on the night of 30th–31st January – a day earlier than was contemplated in the schedule on which Heath and Bennett had been working. Wavell was notified of this and when cabling approval told Percival that he must fight for every foot of Singapore Island. Wavell also conveyed the decision to Australia in a cable dated 29th January which General Sturdee read to the Advisory War Council next day. In this he said the Japanese were making three main thrusts, in one of which warships with large convoys were proceeding by the Moluccas probably against Ambon, but Koepang might be threatened.

The Australians in Malaya had greatly distinguished themselves, he continued. Percival should have the equivalent of approximately three divisions to hold Singapore Island, about half of whom would be fresh. Of the very limited naval forces available in Java a considerable proportion was in harbour for repair or refit, and practically all the rest except

submarines were engaged on escort duties. Endeavours were being made to collect a striking force, but it would be small. No more formations of land troops would be available for about three weeks, when the Australian Corps would begin to arrive. It had been intended to use this Corps to relieve Indian troops in Malaya and carry out a counter-offensive, but in view of the changed situation the Corps must be used in the first instance to secure vital areas in Sumatra and Java. The air striking force amounted to little more than eight to ten American heavy bombers, which had been doing most effective work, but were insufficient to meet all threats. Considerable reinforcements of British and American air forces were on their way.

All I can do in the immediate future (said Wavell) is to check enemy by such offensive action by sea and air as limited resources allow and to secure most important objectives which I conceive to be Singapore, air bases in central and southern Sumatra, naval base at Surabaya, aerodrome at Koepang.

Picture looks gloomy but enemy is at full strength, is suffering severe losses, and cannot replace his losses in aircraft as we can. Things will improve eventually as we keep on fighting but may be worse first.

The Advisory War Council discussed Wavell’s omission of Ambon from the key points to be held. The Chiefs of Staff held that withdrawal from Ambon would be a very difficult operation and in any event it was important to deny it to the Japanese as long as possible.

–:–

For the crossing from the Malayan mainland to Singapore Island it had been planned to form an outer and an inner bridgehead, to safeguard the movement as fully as possible. Anti-aircraft guns were to be grouped to counter Japanese air attacks upon the long stream of men and material which would pass along the Causeway across Johore Strait, and provision was made to ferry troops across the water if the Causeway became unusable. The outer bridgehead would be held by the 22nd Australian Brigade and the 2/Gordons; the inner one by the Argylls, now reorganised but only 250 strong. The Australian brigade would include its 2/19th Battalion, hurriedly reorganised by Colonel Anderson after the losses it had sustained between Bakri and Parit Sulong. General Heath at first allotted command of both bridgeheads to the Argylls’ commander, Colonel Stewart, but General Bennett asserted that as the outer bridgehead troops were to be mainly Australians and Taylor was the senior in rank, they should be under Taylor’s command. Eventually the outer bridgehead was placed under Taylor and the inner one under Stewart. Bennett also pressed for a detailed plan for the withdrawal, pointing out that no times for the various units to cross the Causeway, and no order of march, had been specified. Finally, he protested to Percival against the Australian machine-gun battalion being used to prepare the III Corps positions on the island instead of those to be occupied by Australian troops; but on this point Percival replied that the work must be carried out according to a program laid down by the Fortress Commander, Major-General Simmons. Detailed routes and timings were worked out by Heath with Bennett.

The prospect of holding a bridgehead area in southern Johore for any lengthy period had been discussed but rejected. Some defences had been prepared in the Kota Tinggi area before the war, but they were inadequate; the forces in the bridgehead area would be dependent upon the Causeway and such temporary provision as might be made for traffic to and from the island; and by landing on the island from another direction the Japanese might at last fulfil their threat to the rear of the mainland forces which had hovered over the defenders for so long. Water supply on the mainland would also present an awkward problem, for in view of the situation on the west coast the prospect of holding a sufficiently large area to include the Gunong Pulai catchment area, between Pontian Kechil and the trunk road, and main source of supply to the Johore Bahru area, was not entertained.

The 11th Indian Division was made responsible for holding Skudai on the trunk road against enemy approach from the west coast. Key therefore ordered the remnant of the 53rd Brigade at Benut to withdraw on the night of 29th–30th January to the island, and the 28th Brigade to hold the Pontian Kechil area till dusk on the 29th; then to take up positions in depth on the road to Skudai. Bennett visited the Sultan of Johore after the conference and was entertained by him at length and presented with gifts. Bennett, determined not to be engulfed in defeat, told him that it was quite possible that he might have to attempt escape to avoid becoming a prisoner of war, and might be seeking his aid, especially to obtain a boat for the purpose. That night Bennett instructed his staff to issue orders accelerating the withdrawal of Westforce by one day as had been decided. These were issued next morning (29th January). They provided that the final position on the mainland, to have been held for two days, now would be held for one day only.

In the railway sector another disaster was brewing. Brigadier Lay informed the 22nd Indian Brigade during the night of 27th–28th January that he was moving the 8th Brigade south of Layang Layang and would telephone again later. Before he could do so, however, the railway bridge over a creek near the 4391-mile position on the railway line was prematurely blown, thus disrupting the railway telegraph line – the only means of communication between the two brigades since their wireless sets had been sent back with their transport – and preventing rations and ammunition being sent forward by rail. The position was made worse by the fact that the 22nd Brigade moved farther towards Sedenak than Barstow had ordered, and left unmanned the ridge near Layang Layang that ha had decided it should occupy. In the early hours of the 28th the 22nd Brigade heard transport moving on the estate roads on its right flank, and at dawn Brigadier Painter found that enemy troops were between him and the 8th Brigade. He thereupon decided that immediate withdrawal was essential to regain contact. By 10.15 a.m. the brigade had been concentrated and had begun to move down the western side of the railway.

Meanwhile General Barstow had somewhat varied his previous orders to the brigades, to make sure that the positions specified for them in General Bennett’s withdrawal program at that time – before the accelerated program had been adopted – were securely held. Early on the 28th he went forward to see for himself how the brigades were faring. With him went his senior administrative officer, Colonel Trott, and the Australian liaison officer with the Indian division, Major Moses.37 At Lay’s headquarters he learned of the bridge having been blown, and that the ridge from which it was to have been covered was unoccupied. He immediately ordered Lay to send his leading battalion – the 2/10th Baluch – to the ridge, and with Trott and Moses continued on up the line on a trolley, intending to visit the 22nd Brigade. Finding the Baluchis resting beside the line about a mile short of the creek, he personally ordered them forward, and continued his journey. At the creek the three officers discovered that although the bridge had sagged it was still passable on foot. They therefore crossed it, and walked along the railway embankment towards Layang Layang station, spaced out with Barstow in the lead. Soon they were challenged and fired upon. In their spontaneous move for cover, the general went to the right of the embankment and the others to the left. Attempting to rejoin Barstow, they again came under fire in such volume that they decided the only course left to them was to make their way back.

Bullets again whizzed past them as, having waded the creek, they reached the ridge where the Baluchis were to have been, only to find it occupied by the enemy. After making a detour they again reached the railway, and met the vanguard of the Baluchis moving forward; but more fire from the ridge sent them to cover. Trott thereupon went back to report the situation to the 8th Brigade and 9th Division, while Moses remained with the Baluchis thinking that Barstow might be rescued after the ridge had been gained. However, the Baluchis failed in the attempt and were driven back under heavy fire. No further endeavour was made during the day to reach the 22nd Brigade, and the battalion was withdrawn during the night. The 22nd Brigade thus was left to find its way out of the trap set for it by the Japanese as best it could.

It later transpired that Barstow’s body was found at the foot of the embankment by the enemy. His courage and initiative, at a time when morale was being severely tested, had won for him the high regard of the Australians and others with whom he had been associated.38 Moving back along the railway, the 22nd Brigade advance-guard at midday on 28th January found Japanese troops in possession of Layang Layang station and suffered about fifty casualties in an unsuccessful endeavour

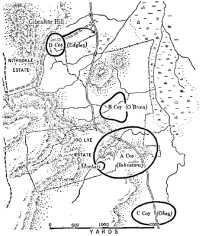

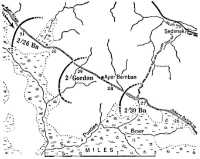

Namazie Estate, 7 a.m. 28th January

to eject them. Lacking fire support, means of evacuating his wounded other than on hand-borne stretchers, and communication with the 8th Brigade, Painter decided to move his brigade across country west of the railway, hoping to reach the 8th Brigade’s left flank. A track shown on his only map of the area came to an end in dense jungle, through which his men hacked away on a compass bearing until the moon went down and they were halted.

On the trunk road the Japanese had begun 28th January with probing patrol movements. The Gordons, in the foremost position at mile-post 411, were engaged in skirmishes, and fire was soon concentrated on the 2/26th Battalion on the Gordons’ right, amid rubber trees. The supporting position was held by the 2/30th Battalion, at the junction of the estate road with the trunk road, which for two miles to the rear was bordered by jungle. Both Brigadier Maxwell and Colonel Galleghan were uneasy about the position because of the opportunities, remarked upon by Brigadier Painter, that the estate roads offered to the enemy, who if he reached the jungle to the rear might isolate the two battalions. A plan discussed by Maxwell and Galleghan to organise a battalion ambush at the entrance to the jungle defile was set aside after weighing its possibilities.

A series of fire attacks on the Gordons and on the flanks of the 2/26th Battalion, with constant air support, lasted throughout the morning. The return fire was so effective that the attackers were held in check, but other enemy troops meanwhile worked round through the rubber to the right of the 2/30th Battalion. Near midday, a patrol came upon about six of them, near where “D” Company was stationed in a rearward position on this flank, and reported their presence to company headquarters. A fighting patrol of two sections, led by Corporal Moynihan,39 was thereupon sent to dispose of what seemed to be a small infiltration. In an encounter they found themselves outweighed in fire power, and had difficulty in withdrawing. Galleghan concluded that, as he had anticipated, the Japanese were trying to get to the jungle defile at the rear of the brigade’s positions, and sent Captain Duffy with two platoons to the area to meet the threat as best he could. Leading one of the platoons, Lieutenant Jones saw two men sitting on a rise covered by a type of vine familiar in rubber plantations, about where a “D” Company standing patrol was expected to be.

“Yes, we are ‘Don’ Company,” was the reply to a challenge from a distance.

“Like hell they are! They’re Japs!” came immediately from one of the platoon, who confidently opened fire on the two Japanese, as indeed they were, and wearing British steel helmets. Immediately the whole hillside seemed to spring into life with Japanese troops, who were lying there, having been very effectively concealed by the cover plant. ... The platoon was heavily outnumbered, but unhesitatingly engaged the enemy and quickly inflicted forty to fifty casualties with steady fire. Corporal Swindail40 accounted for a Jap only twenty yards away, who had Lieutenant Jones pinned down. Swindail had to expose himself to pick off his man and was himself wounded before succeeding. As Lieutenant Jones was armed only with a revolver, Swindail flung his rifle to his officer, who then completed the job.41

The other platoon, led by Lieutenant Cooper, arrived at this critical stage and the Japanese were repulsed. The two platoons took up a position covering the approach to the battalion’s rear at a point where the rubber and the jungle met. However, “D” Company’s headquarters and the battalion headquarters area between this point and the trunk road came under fire, and it was evident that the threat was increasingly serious. Three more platoons, two armoured cars and a section of mortars were moved to the area, and the forward units were told of the situation. At Galleghan’s request Boyes sent him a company of the 2/26th Battalion to come under command and reinforce his right flank. Three platoons, covered by two others, were ordered to attack under Captain Duffy’s direction the high ground occupied by the Japanese, and a strong outflanking attack was to be made.

The frontal attack was launched at 4.40 p.m., under a storm of covering small arms fire. Although the Japanese made expert use of cover, the Australians got in among the foremost of them with bayonets, the armoured cars blasted machine-gun posts and other targets, and under this fierce assault the enemy fell back. There were no tanks at hand to tip the scales against the Australians, whose bayonets again caused screaming confusion; but the Japanese now produced containers which exploded into clouds of yellow fumes. At first it seemed that they had resorted to the use of poison gas. With no respirators available to them the Australians were robbed of their advantage by fits of coughing and by their eyes watering so profusely that they could scarcely see. One container, which appeared to have been fired from a rifle or mortar, burst close to company headquarters and emitted more fumes. To cope with the effect which the fumes produced as they spread, the forward troops in the vicinity were withdrawn, and the intended outflanking attack was withheld.

At the regimental aid post it was soon discovered that the fumes were merely an irritant and that those who had encountered them soon recovered. However, the enemy had gained further freedom of movement and might reach the defile as night was falling. It seemed obvious that the aim was to force another brigade into the jungle. Meanwhile Captain

Wyett42 had come forward from 27th Brigade headquarters with authority to issue orders on Brigadier Maxwell’s behalf. Orders were issued for withdrawal at nightfall, with special precautions against attack in passing through the defile.43 Westforce in due course ordered the 9th Indian Division to conform by withdrawing during the night to Sedenak. This order was passed on to the 8th Indian Brigade; but, as has been shown, communication with the 22nd Indian Brigade had now failed.

The 2/26th Battalion, last in the order of withdrawal, had difficulty in breaking contact, but the move was successfully made. Owing to lack of troop-carrying transport at the forward positions, however, a twelve-mile march was now superimposed upon the day’s fighting and all that had gone before it. Boyes set aside standing orders and used portion of his “A” Echelon vehicles in successive runs carrying men over portions of the route. Even a water cart managed to make several trips with up to twenty-five men and many weapons, filling the bottles of the marching troops as it returned. Such aid as this, and the spirit in which it was given, did much to help the men overcome their fatigue.

Early on the morning of 29th January, before it had received the Westforce order for the generally accelerated withdrawal, the 9th Indian Division’s headquarters ordered the 8th Indian Brigade forward in an endeavour to rescue the 22nd Indian Brigade. On receipt of the Westforce order this move was cancelled, and the 8th Brigade was instructed to withdraw during the night to rail mile 4501, about two miles and a half north of Kulai. The 22nd Indian Brigade, which at the time was struggling on through increasingly difficult country, was thus finally cut off.44

The 27th Australian Brigade, now in more rubber and jungle country at milestone 31, near Ayer Bemban forward of a branch road to Sedenak, had another heavy day’s fighting on the 29th. The 2/26th Battalion was astride and mostly west of the trunk road. Behind them were the Gordons, and the 2/30th was in reserve at the road junction. After a sharp early clash had brought Australian artillery fire on to the Japanese, a party of thirty of them dressed in European, Indian and native clothing was allowed to reach a position between the two forward companies of the 2/26th, and there was wiped out. Others were found to be massing behind a rise, and were attacked with grenades and bayonets. By mid-morning all four Australian companies were being fiercely and persistently attacked. The Japanese tried to set up mortars and machine-guns in full view of the Australians, and were mown down in most instances before the weapons could be fired. Their casualties mounted rapidly, but so did their reinforcements, and in mid-afternoon, when it was estimated that

Ayer Bemban, 29th January

three Japanese battalions had been brought forward, one battalion with infantry guns was seen forming up on the road.

The Australian artillery quickly took advantage of the new target and the battalion’s mortars thickened the fire. A sharp counter-attack by the 2/26th Battalion’s “D” company (Captain Tracey45), which again found use for its bayonets, finally disposed of this threat, but was badly weakened by an accurate bombing attack. Bombing and shelling of the battalion generally was added to the weight of the infantry attacks, and more fumes of the kind experienced the day before were released in the area occupied by “B” Company (Captain Swartz46). The battalion nevertheless stood its ground, and, as night set in, the Japanese gave up their costly and unusually protracted assault.47