Chapter 17: Cease Fire

On Friday, 13th February, whatever hope remained that Singapore might be saved was on its deathbed. Troops were disposed along an arc between the enemy and the town, but it was by no means firmly held, nor was it fortified. Behind it, instead of an area cleared for battle and organised for a maximum defensive effort, were thickly-clustered shops, offices, schools, churches, houses, gardens, and about a million civilians, many of them refugees from the mainland. Most of the civilians, especially the Asians, were pitifully exposed to the effects of bombardment, and without prospect of evacuation. In this densely congested area, where there was now little room for discrimination by the enemy between what was or was not a legitimate military target, bombs and shells were blasting away the last essentials of resistance.

The 2/30th Australian Battalion remained north of the defensive arc, in positions near Ang Mo Kio village, until 12.30 p.m., when the 53rd Brigade (Brigadier Duke), last of the forces to leave the Northern Area, had passed through. Then, in the course of its own withdrawal,

the old optimism, that always arose at the sight or news of supporting units, returned as the battalion passed through the long columns of British and Indian troops. But only one thing could have inspired any real sense of security: the appearance of British planes. The inevitable red-spotted variety soon dispelled futile dreams of this nature. ... Disappointment at not seeing more planes in the air in the last few weeks had been great. ... Though the campaign was nearly at its weary end, many of the troops had not seen a plane of either side brought down.1

Thomson road was choked with transport converging on this artery into Singapore, and Japanese planes were doing ghastly work. At Tanglin Barracks, on their way to Australian perimeter positions, the troops discovered that the barracks stores

contained practically everything that they could desire; there was clothing of all descriptions, military of course, and food in abundance ... without delay the troops began to help themselves to much needed stocks of clothing and, ignoring plain army rations, selected some choice lines of luxury foods which they had not seen for many a long day. There was also a fine collection of wines and spirits, together with a good supply of beer, which under the circumstances was not enjoyed to the full. ... It is unusual for Australian soldiers to deliberately pass up the opportunity of enjoying a glass of beer, particularly Australian beer. But there it was, in a very large barrel, by one of the barrack roads, and a stray soldier was imploring passers-by to come and drink with him. They passed him by, preoccupied and only vaguely interested ...2

Brigadier Taylor, who had been given a sleeping draught at the 2/13th A.G.H. the previous day, had left it in the morning with Lieut-Colonel Anderson and other officers who had been patients there, to resume duty.

He was given the task of forming the Australian perimeter, oval shaped and 7 miles in circumference. Holland road was the main axis, and the divisional headquarters, in Tanglin Barracks, was at the centre. Colonel Anderson rejoined his 2/19th Battalion.

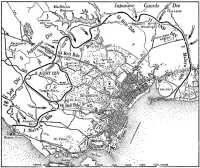

The segments of the arc which General Percival had ordered to be occupied by his forces generally were: Kallang airfield to Paya Lebar airstrip, the 2nd Malaya Brigade; airstrip to a mile west of Woodleigh on Braddell road, the 11th Division; Chinese cemetery area north of Braddell road, the 53rd Brigade; Thomson road to Adam Park, the 55th Brigade (inclusive of Massy Force); astride Bukit Timah road, the 54th Brigade and remnants of Tomforce; Farrer road sector, 2/Gordons; junction of Farrer road and Holland road to the railway north of Tanglin Halt, the 8th Australian Division; astride Buona Vista road west of Tanglin Halt, the 44th Brigade; Pasir Panjang ridge and Pasir Panjang village, the 1st Malaya Brigade.3

General Bennett, having reviewed the situation on either flank of the AIF, had decided as previously related to collect all the AIF, except a few units, inside the Australian perimeter. The north-western portion of the perimeter was the segment allocated to the AIF in the general line which General Percival had ordered to be occupied. The Australian perimeter was fully manned on all fronts in case the Japanese should penetrate the general line and endeavour to attack the Australians on either flank or even from the rear. Most units of the AIF were concentrated in the perimeter, and many of the base units were used to man sectors of the Australian line. The swimming pool at Tanglin was filled with fresh water and this, together with the reserve supplies of food, ensured that the AIF troops would not go short of sustenance for some days at least.

The withdrawals were followed by a lull in the fighting, except on the Pasir Panjang ridge, which formed a salient running north-westward from the general defensive line. There, after a two-hour bombardment, the 18th Japanese Division thrust towards the Alexandra area where the island’s largest ammunition magazine, the ordnance depot, and the principal military hospital were situated.

The 1st Malay Battalion, a regular unit, officered principally by Englishmen familiar with the language and customs of their men, showed during the struggle for the ridge how well more such forces could have been employed in the defence of their homeland.4 Despite their determined resistance, however, they were gradually overpowered. The Japanese won their way to heights known as Pasir Panjang III and Buona Vista hill, and along the Pasir Panjang road by the southern shore. As those on the ridge reached The Gap, near the Buona Vista road, where under peaceful

conditions there had been a popular lookout over part of Singapore and neighbouring islands, a desperate fight ensued around the Malay battalion’s headquarters. On the right, the 2/Loyals became exposed to enfilade fire from the ridge, and by 5 p.m. the Japanese had wrested from the 5/Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire a hill a little west of the Buona Vista road. As no troops were immediately available to attempt to regain the ridge forward of The Gap, the 1st Malaya Brigade and the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire were withdrawn at nightfall to what was known as the Alexandra switchline. This was where Alexandra road runs northward between the ridge and other high ground east of it, of which Mount Faber is the principal feature.

As its left flank became exposed by the Japanese advance, the 44th Indian Brigade was withdrawn down the railway to Alexandra road and thence to the Mount Echo area at the south-east corner of the AIF perimeter. The withdrawal accelerated movements whereby this perimeter was manned during the day by the Australians, including the 27th Brigade now reassembled under Brigadier Maxwell. The only Australian units not accommodated in the perimeter were the 2/13th A.G.H., at Katong on the east coast outside the general perimeter, and the 2/10th A.G.H., the Convalescent Depot, and the 2/10th and 2/12th Field Ambulances. The 2/Gordons – the only non-Australian unit in the perimeter – were still under General Bennett’s command. Although the Japanese were making their way eastward through areas north and south of the perimeter, it was not attacked in force from this stage onward.

The sufferings of Singapore’s civilians meanwhile were reaching an intolerable pitch. Despite inadequate provision for their protection, they had borne stoically and resourcefully ever since the beginning of the campaign an increasing scale of air raids. Now with artillery also pounding streets, shops and dwellings, and a water supply failure imminent, many more were being killed, many maimed, and many were losing all they possessed.

A scene, typical of many since the bombing of Singapore began, met the eyes of an officer as he drove along Orchard road. A stick of bombs had just fallen.

A petrol station on our left blazed up – two cars ahead of us were punted into the air, they bounced a few times before bursting into flames. Buildings on both sides of the road went up in smoke. ... Soldiers and civilians suddenly appeared staggering through clouds of debris; some got on the road, others stumbled and dropped in their tracks, others shrieked as they ran for safety. ... We pulled up near a building which had collapsed onto the road – it looked like a caved-in slaughter house. Blood splashed what was left of the lower rooms; chunks of human beings – men, women and children – littered the place. Everywhere bits of steaming flesh, smouldering rags, clouds of dust – and the shriek and groan of those who still survived.

Farther on the officer slowed down in obedience to a signal from a frail Chinese woman who offered him her small child.

She was spattered in blood and the youngster was bleeding profusely from a head wound. I cheered her up in her own language and she smiled through her

tears as we helped her into the ambulance while the chaps attended to the child’s wounds.5

In terms of power politics, such sufferings were negligible. Although no warm regard existed between Germany and Japan, the effect of Japan’s onslaught in drawing off substantial forces from the war in Europe had been perceived with gratification by Herr Hitler and his followers. A report by Admiral Raeder, head of the German Navy, to the Führer on 13th February showed how much more was now expected of Germany’s Far Eastern ally.

Rangoon, Singapore and, most likely, also Port Darwin will be in Japanese hands within a few weeks. Only weak resistance is expected on Sumatra, while Java will be able to hold out longer. Japan plans to protect this front in the Indian Ocean by capturing the key position of Ceylon, and she also plans to gain control of the sea in that area by means of superior naval forces. Fifteen Japanese submarines are at the moment operating in the Bay of Bengal, in the waters off Ceylon, and in the straits on both sides of Sumatra and Java. With Rangoon, Sumatra, and Java gone, the last oil wells between Bahrein and the American continent will be lost. Oil supplies for Australia and New Zealand will have to come from either the Persian Gulf or from America. Once Japanese battleships, aircraft carriers, submarines, and the Japanese naval air force are based on Ceylon, Britain will be forced to resort to heavily-escorted convoys if she desires to maintain communications with India and the Near East. Only Alexandria, Durban, and Simonstown will be available as repair bases for large British naval vessels in that part of the world.6

Possibilities such as these, as they related to the area of his command, had to be weighed by General Wavell. He cabled to Mr Churchill on the same day: “... The unexpectedly rapid advance of enemy on Singapore and approach of an escorted enemy convoy towards southern Sumatra necessitate review of our plans for the defence of the Netherlands East Indies, in which southern Sumatra plays a most important part. With more time and the arrival of 7th Australian Division,7 earmarked for southern Sumatra, strong defence could be built up. But ground not yet fully prepared. ...”

How much of the more time that was needed could Singapore’s forces wrest from the enemy? The Japanese were within 5,000 yards of the main seafront, bringing the whole city within artillery range, when Percival summoned a conference at Fort Canning at 2 p.m. Mainly because there was no reserve available for the purpose, General Bennett now agreed with his fellow commanders that there remained no prospect of successful counter-attack. They emphasised the effect on their troops of continuous day and night operations, with no hope of relief,8 and recognised

that the plight of the civilians, in the event especially of domination by the Japanese of all food and water supplies, could not be ignored. Percival considered that in these circumstances it was unlikely that resistance could last more than a day or two, and that there “must come a stage when in the interests of the troops and the civil population further bloodshed will serve no useful purpose”. He therefore asked Wavell for wider discretionary powers. The reply next day, reflecting a situation more readily seen from Wavell’s point of view than from under the ominous smoke-pall of Singapore, was:

You must continue to inflict maximum damage on enemy for as long as possible by house-to-house fighting if necessary. Your action in tying down enemy and inflicting casualties may have vital influence in other theatres. Fully appreciate your situation, but continued action essential.9

As Bennett returned from the conference to his headquarters

there was devastation everywhere. There were holes in the road, churned-up rubble lying in great clods all round, tangled masses of telephone, telegraph and electric cables strewn across the street, here and there smashed cars, trucks, electric trams and buses that once carried loads of passengers to and from their peaceful daily toil. The shops were shuttered and deserted. There were hundreds of Chinese civilians who refused to leave their homes. Bombs were falling in a near-by street. On reaching the spot one saw that the side of a building had fallen on an air raid shelter, the bomb penetrating deep into the ground, the explosion forcing in the sides of the shelter. A group of Chinese, Malays, Europeans and Australian soldiers were already at work shovelling and dragging the debris away. Soon there emerged from the shelter a Chinese boy, scratched and bleeding, who immediately turned to help in the rescue work. He said, “My sister is under there.” The rescuers dug furiously among the fallen masonry, one little wiry old Chinese man doing twice as much as the others, the sweat streaming from his body. At last the top of the shelter was uncovered. Beneath was a crushed mass of old men, women, young and old, and young children, some still living – the rest dead. The little Oriental never stopped with his work, his sallow face showing the strain of anguish. His wife and four children were there. Gradually he unearthed them – dead. He was later seen holding his only surviving daughter, aged ten, by the hand, watching them move away his family and the other unfortunates. This was going on hour after hour, day after day, the same stolidity and steadfastness among the civilians was evident in every quarter of the city.10

Rear-Admiral Spooner had decided that rather than allow them to fall into the hands of the enemy as at Penang, the small ships and other sea-going craft still in Singapore Harbour, including some naval patrol vessels, should be sailed to Java. These craft, with which he himself would leave, would carry about 3,000 persons, as well as their crews, thus providing a last chance of organised evacuation. It was decided to send in them principally service people and civilians who could be spared, and also some chosen because their experience and knowledge would be useful elsewhere.

Of the vacancies, 1,800 were allotted to the army. Especially because of reports of what had happened to nurses who had fallen into the hands

of the Japanese at Hong Kong, all women in the nursing services were to be included. Staff officers and technicians no longer required were to be sent at the discretion of formation commanders. Air Vice-Marshal Pulford, who had declined to leave until air personnel capable of evacuation had gone, was also to go.

The 1,800 were to include 100 from the AIF. Bennett decided that this Australian group would be led by Colonel Broadbent, his principal administrative officer, and appointed Lieut-Colonel Kent Hughes to succeed him in this position. Lieut-Colonel Kappe, Chief Signals Officer, was nominated by Malaya Command to leave. With him were to be twenty-seven of his best signals technicians. Captains Fisk11 and Pople,12 on Bennett’s list, with seven other ranks, boarded a vessel. The remainder were too late in leaving Tanglin and were unable to get away.

Percival again visited the Governor, who, because a shell had entered a shelter under Government House, killing several people, had moved to the Singapore Cricket Club; and he said goodbye to Pulford. Referring to the course of the campaign, Pulford remarked, “I suppose you and I will be held responsible for this, but God knows we did our best with what little we had been given.”13 By this time Singapore’s public services had come almost to a standstill for lack of labour. Corpses lay unburied; and water had ceased to reach many taps, because it was gushing unchecked from broken mains at lower levels. Hospitals were trying to cope with ever-increasing numbers of wounded soldiers and civilians.

The next day, 14th February, brought no relief to the defenders and civilians of Singapore. In their principal thrusts north of the town, where both the 5th Japanese Division and the Guards Division were now employed, the enemy got to within a few hundred yards of the Woodleigh Pumping Station, vital to the maintenance of the city’s water supply, before they were held by the 11th Indian Division; forced a gap between the 53rd and 55th Brigades which had to be plugged with a battalion from the 11th Indian Division; and sent tanks down Sime road, some of which were stopped only after they had reached the edge of the Mount Pleasant residential area. In the south-western area of the city, a series of attacks which commenced at 8.30 a.m. was stoutly resisted by the 1st Malaya Brigade. Heavy losses occurred on both sides, but the Japanese poured in fresh troops and, about 4 p.m., with the aid of tanks, penetrated the brigade’s left flank, forcing it to withdraw to the vicinity of Alexandra road. Japanese naval units which entered the Naval Base during the day were surprised to find it deserted and undefended. However, because of delay in getting supplies across Johore Strait on to the island, the enemy artillery was running short of ammunition, and “deep consideration was

Daybreak, 14th February

given to preserving progress and battle strength in the army’s fighting henceforth.”14

Though the 2/13th Australian General Hospital north-east of the city fell into enemy hands without harm to its occupants, a ghastly episode occurred when Japanese troops advancing along the Ayer Raja road reached the Alexandra military hospital in pursuit of some detached Indian troops who fell back into the hospital still firing. The Japanese bayoneted a number of the staff and patients, including a patient lying on an operating table. They herded 150 into a bungalow, and the next morning executed them. Among those who lost their lives was Major Beale, who had been taken to hospital after being wounded on the 11th.

It seemed likely after the withdrawal of the 1st Malaya Brigade that the Australian perimeter would soon be completely by-passed. General Bennett concluded that his troops might become isolated from the rest of the defending forces, and sent a cable to Army Headquarters in Melbourne:

AIF now concentrated in Tanglin area two miles from city proper. Non-fighting units less hospital including my headquarters in position. Can rely on troops to

hold to last as usual. All other fronts weak. Wavell has ordered all troops to fight to last. If enemy enter city behind us will take suitable action to avoid unnecessary sacrifices.15

Bennett as well as the Japanese was concerned with the availability of artillery ammunition. Information had been received from Malaya Command the day before that there was a serious shortage of field gun ammunition, particularly for 25-pounders, as so many dumps had been captured by the invaders. The Australian ammunition column had shown courage and resource in salvaging shells; but now it was found that no further supplies of 25-pounder ammunition could be obtained from dumps or the base ordnance depot, which was under fire and ablaze. Bennett therefore ordered that the AIF guns should fire only in defence of the Australian perimeter, “and then only on observed targets, on counter-battery targets, and H.F. targets where enemy troop and battery movements were definitely known to be taking place.”16

General Percival had received early on 14th February from the Director-General of Civil Defence (Brigadier Simson) a report that the town’s water-supply was on the verge of a complete failure. At a conference held by Percival at 10 a.m. at the municipal offices, attended also by the Chairman of the Municipality, by Brigadier Simson and the Municipal Engineer, the latter reported that more than half the water being drawn from the reservoirs was being lost through breaks in the water mains caused by shells and bombs. He said that the supply might last for 48 hours at most, and perhaps not more than 24 hours. Percival arranged to withdraw about 100 men of the Royal Engineers from the 1st Malaya Brigade’s sector to assist in repairing the mains. He then visited the Governor, telling him that despite the critical water situation he intended to continue the fighting as long as possible.

Staunch though he had been in refusing to admit even the possibility of defeat, the Governor cabled to the Colonial Office:

... There are now one million people within radius of three miles. Water supplies very badly damaged and unlikely to last more than twenty-four hours. Many dead lying in the streets and burial impossible. We are faced with total deprivation of water, which must result in pestilence. I have felt that it is my duty to bring this to notice of General Officer Commanding.17

Percival reported the situation to General Wavell, adding that though the fight was being continued, he might find it necessary to make an immediate decision. Wavell replied that fighting must go on wherever

there was sufficient water for the troops, and later dispatched a further message:

Your gallant stand is serving a purpose and must be continued to the limit of endurance.

He nevertheless reported to Mr Churchill that he feared Singapore’s resistance was not likely to be very prolonged. The British Prime Minister wrote later that at this stage he decided that

now when it was certain that all was lost at Singapore ... it would be wrong to enforce needless slaughter, and without hope of victory to inflict the horrors of street fighting on the vast city, with its teeming, helpless, and now panic-stricken population.18

He therefore cabled to Wavell:

You are of course sole judge of the moment when no further result can be gained at Singapore, and should instruct Percival accordingly. C.I.G.S. concurs.

At a second conference at the municipal offices, about 5 p.m. on the 14th, the Water Engineer reported that the water-supply position was a little better. Percival asked Brigadier Simson for an accurate report at 7 a.m. next day of the prospect at that time. Curiously, though the Japanese had gained control of the reservoirs, water continued to flow to the pumps at Woodleigh.

As mentioned, the Australian Government Representative, Mr Bowden, largely because of his membership of the War Council in Singapore, had supplied information which, with General Bennett’s reports, had helped to mould Australian policy.19 Now the Council had ceased to function, and Singapore’s civilian administration was rapidly coming to a standstill. Bowden had received from the Australian Minister for External Affairs an assurance that his Government would try to arrange an exchange of Bowden and his staff against the Japanese diplomatic staff in Australia. However, he received information on 14th February suggesting that capitulation was very close; and a member of Percival’s staff offered him an opportunity of leaving with some senior officers and certain persons selected by the Governor. Bowden, Wootton and Quinn thereupon decided that, as their remaining in Singapore would serve no useful purpose, they would accept the offer. The vessel upon which they would embark would be the Osprey, a launch designed to seat ten persons. Bowden drafted his last message to Australia: “Our work completed. We will telegraph from another place at present unknown.” Although by the time it was lodged the means of transmission had been reduced to a small handset operated at the point where the cable entered the water, the message reached its destination. The three men went to the launch at 6.30 p.m. By this time groups of soldiers including Australians were at large seeking escape,

and a few, armed with Tommy guns and hand grenades, threatened to open fire on the launch unless they themselves were taken aboard. When, at 11.30 p.m., the Osprey moved out, with thirty-eight aboard, rifle shots were fired at it, but no one was hit. The launch party, which included Colonel Dailey, of Dalforce, and some of his men, transferred in the harbour to a forty-foot diesel-engined vessel, the Mary Rose.

Meanwhile, General Bennett had been giving close consideration to the question of escape if capitulation were enforced. Colonel Broadbent was the only senior officer who had been sent away with the special party, and there was doubt whether he would be able to reach Australia. Bennett considered it advisable that other officers from his headquarters should, if possible, return to Australia and give first-hand information of Japanese methods and strategy. Major Moses, who had been acting as liaison officer with the 44th Indian Brigade, had told Bennett’s aide de camp, Lieutenant Walker, on 12th February that he intended to “have a crack at getting away”. Walker thereupon broached the subject of getting Bennett away; but as Moses was then to be appointed brigade major of the 22nd Brigade in place of Beale, he dropped out of the project for the time being. As it happened the appointment was filled by Captain Fairley. When Moses returned, Walker had invited Captains Curlewis and Jessup,20 two of Bennett’s staff officers, to join the escape party. Curlewis, who had been President of the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia, was known to be a strong swimmer, and Jessup spoke Malay and Dutch. From 12th February onward, steps had been taken to put an escape plan into operation.

Some further gains were made by the enemy during the night, but the general defence line was held. Brigadier Simson reported next morning (15th February) that the water-supply had deteriorated to the extent that most of the water was running to waste because repairs could not keep pace with breakages; and supply to the higher parts of the town had failed. After a Communion service at Fort Canning, a conference was held at 9.30 a.m. of the area commanders and others. The commanders reported on the tactical situations on their fronts; Brigadier Simson said that such water-supply as existed could not be guaranteed for more than 24 hours, and that if a total failure occurred it would result in the town being without piped water for several days.

Percival said that only a few days’ reserve of military rations remained, but there were still fairly large civilian food stocks. Hardly any petrol remained other than that in the tanks of motor vehicles, there was a serious shortage of field gun ammunition, and reserves of shells for Bofors anti-aircraft guns were almost exhausted. The only choices available, he continued, were to counter-attack immediately to regain control of the reservoirs and the military food depots and drive back the Japanese artillery to an extent which would reduce the damage to the water-supply; or to surrender.

The area commanders again agreed that a counter-attack was out of the question. Consideration was given to what might happen if the Japanese smashed their way into the town, amid its civilians. Bearing the tremendous responsibility of determining what to do in the circumstances, Percival decided with the unanimous concurrence of the others at the conference to seek a cessation of hostilities as from 4 p.m.,21 and to invite a Japanese deputation to visit the city to discuss terms of capitulation.

It was further decided that a deputation representing the military and civil authorities should go to the enemy lines as soon as possible, to propose the cease-fire and to invite the Japanese to send a deputation to discuss terms. Orders were to be issued for the destruction of all secret and technical equipment, ciphers, codes, secret documents, and guns. Personal weapons were excepted, in case the Japanese would not agree to the proposal to be made to them, or the weapons were needed before agreement was reached.

Percival was strengthened in his resolve by a message received from Wavell that morning:

So long as you are in position to inflict losses to enemy and your troops are physically capable of doing so you must fight on. Time gained and damage to enemy of vital importance at this crisis. When you are fully satisfied that this is no longer possible I give you discretion to cease resistance. Before doing so all arms, equipment, and transport of value to enemy must of course be rendered useless. Also just before final cessation of fighting opportunity should be given to any determined bodies of men or individuals to try and effect escape by any means possible. They must be armed. Inform me of intentions. Whatever happens I thank you and all troops for your gallant efforts of last few days.

Percival thereupon notified Wavell of his decision, and again reported to the Governor, but Bennett was not informed, as obviously he should have been, of Wavell’s view that opportunities should be given for escape.22 However, Bennett in turn called his senior commanders together, told them of the decision to negotiate with the enemy, and the question of escape was discussed. It was agreed that to allow any large-scale unorganised attempts to escape would result in confusion and slaughter. Officers recalled how Japanese troops had run wild after capturing cities in China, and it was agreed that the Australians should be kept together and sentries posted. Bennett thereupon issued an order that units were to remain at their posts, and concentrate by 8.30 a.m. next day23 (but said after the war that this did not mean that no-one was to attempt to

escape after the surrender). The order was of course important not only to the Australians, but to the other troops and to the inhabitants of Singapore generally because of the effect which either a disciplined surrender or disorder and disintegration in the Australian perimeter might have upon their fate. Similarly, it was important to all concerned that order should be maintained in the other formations also.

Meanwhile fighting continued north and south of the city, yielding further gains to the enemy against troops exhausted by day and night pressure against them. In the north-east, the defenders fell back towards the Kallang airfield, and the northern line generally was retracted despite local counter-attacks. The 2/Loyals were under attack throughout the day in the south-west of the city, and during the afternoon withdrew, with the Malay Battalion and the 5/Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, to a line from Keppel Golf Links northward, near the southernmost portion of the AIF perimeter. This perimeter now became a salient sandwiched between enemy forces, and appeared likely soon to be completely enveloped.

The joint deputation, sent along Bukit Timah road to the Japanese 5th Division’s lines, returned about 1 p.m. with instructions that Percival was to proceed with his staff to a meeting with Lieut-General Yamashita, the Japanese commander. This took place about 5.15 p.m. in the Ford motor factory north of Bukit Timah village. Although Percival received no copy of the galling terms, he recorded them from memory in his subsequent dispatch:

(a) There must be an unconditional surrender of all military forces (Army, Navy and Air Force) in the Singapore area.

(b) Hostilities to cease at 2030 hours, British time24 – i.e. 2200 hrs Japanese time.

(c) All troops to remain in positions occupied at the time of cessation of hostilities pending further orders.

(d) All weapons, military equipment, ships, aeroplanes and secret documents to be handed over to the Japanese Army intact.

(e) In order to prevent looting and other disorders in Singapore town during the temporary withdrawal of all armed forces, a force of 100 British armed men to be left temporarily in the Town area until relieved by the Japanese.25

Yamashita insisted that these terms be accepted immediately; and Percival felt that he was in no position to bargain. In complying he told Yamashita that there were no ships or aircraft in the Singapore area, and that the heavier types of weapons, some of the military equipment and all secret documents had already been destroyed pursuant of orders he had issued after his commanders’ conference.26

This news, unlikely to be palatable to Yamashita, was received more placidly than Percival had expected. Japanese accounts of their circumstances during the assault on Singapore suggest that it was a relatively minor consideration. A report attributed to Yamashita’s chief of staff, Lieut-General Suzuki, related that of the 1,000 rounds of shells allotted to each Japanese cannon, 400 had been fired against Singapore Island from Johore Bahru, and another 400 before the morning of 13th February.27 At that stage the Japanese had been experiencing an “unimaginably vehement” bombardment, and a bayonet charge to have been made in the 18th Division’s area in the south of the city was held up by heavy fire.

Describing in a radio talk the scene as he and Yamashita watched the battle on 15th February from a height near Bukit Timah, Suzuki said:–

My eye was caught by a Union Jack fluttering in the breeze on the top of Fort Canning. ... I figured that it would be a good week’s work to take the heights that still intervened between us and our object. ... Behind Singapore was an island with a fort. To the left was the Fort Changi. It was no simple matter to take these forts. I figured that a fairly large number of days would be required to capture this last line of defence of the city. ... Presently, it was intimated to me ... that the bearer of a flag of truce had come.

This account is of course consistent with Singapore having been surrendered for reasons not obvious at the time to the Japanese, such as the threatened failure of food, ammunition and water supplies. It is also a tribute to the defenders’ artillery and to the men who stood in the path of the Japanese thrusts to the heart of the city.

The magnitude of the disaster which had befallen them was not easily grasped by the battle-weary forces now at the mercy of an enemy alien to them in language, custom and thought. What lay ahead? When, if ever, would they see their homes again? From the point of view of the Australian troops, what would happen in their absence, with Singapore no longer an obstacle between the Japanese and Australia, and they themselves powerless to defend their own soil? Perhaps this was their bitterest thought.

On the other hand, the prospect of a cease-fire offered at least a chance of temporary oblivion in long-delayed sleep. Some were past caring for the time being what happened after that. Some, though they were required to stay in their positions, considered prospects of escape. Some who had failed to rejoin their units searched the waterfront for a way out of the shambles, and its atmosphere of futility and defeat. There remained to General Bennett the choice between becoming a prisoner of war or acting on his escape plan.

I personally (he wrote subsequently) had made this decision some time previously, having decided that I would not fall into Japanese hands. My decision was fortified by the resolve that I must at all costs return to Australia to tell our people the

story of our conflict with the Japanese,28 to warn them of the danger to Australia, and to advise them of the best means of defeating Japanese tactics.29

After directing that his men should be supplied with new clothing and two days’ rations, Bennett set out early in the afternoon with Moses and Walker to tour the Australian lines and look for a way through the Japanese forces. The attempt would be hazardous – the risks involved without doubt greater than those involved in remaining – but Bennett’s personal courage was beyond question. He took leave of a number of his officers and, during the evening, orders for a “cease-fire” as from 8.30 p.m. came through. When this time arrived he handed over his command to his artillery commander, Brigadier Callaghan (who had administered the 8th Division during his visit to the Middle East) and moved off. With him went Moses and Walker.30 The three got away from Singapore Island about 1 a.m.

In the Australian lines Japanese troops were head cheering as they received news that the campaign was about to end; but sniping, shelling and bombing continued until the “cease-fire”. Then the rattle and roar of battle sank to a strange and solemn hush. In the comparative silence, the small sounds of everyday life, and the groans and cries of the wounded, seemed to be magnified and given a keener significance. The dense smoke still hovering over the city, principally from burning fuel and oil depots but also from homes, shops and offices, became a stiffing shroud. Beyond it the fall of Singapore reverberated throughout the world as one of the greatest disasters in British history.

–:–

During the invasion of the island the No. 3 Japanese Flying Corps had engaged chiefly in cooperation with the ground troops, and in attacking ships seeking to escape from Singapore; the 12th Air Corps in gaining air superiority over Singapore; and the 57th Air Corps in attacking key positions, particularly those occupied by the opposing artillery. The aircraft made 4,700 sorties and dropped 773 tons of bombs. The Japanese anti-aircraft units, with few and then no British planes to engage their attention, used their weapons for cooperation in ground fighting. Thus

the defending troops became exposed to the full and unopposed weight of the Japanese air attack, and were targets for their anti-aircraft guns as well as of their field artillery. Nevertheless, the Japanese casualties in the capture of the island were 1,714 killed and 3,378 wounded. As against this, British forces numbering about 85,000, and masses of stores, weapons, and other material which could ill be spared from the resources necessary elsewhere to stem the Japanese onslaught generally, fell into their hands. It was to Yamashita’s credit that he kept his troops, other than those engaged in police duties, from any mass entry to the city, and that order was maintained.

After a seventy-day campaign, the whole of Malaya was at the feet of the enemy. The Japanese forces in this period had advanced a distance of 650 miles – in which the Australians had been engaged over a distance of 150 miles – at an average rate of nine miles a day, from Singora (Thailand) to Singapore’s southern coast. The casualties among the defenders were: United Kingdom, 38,496; Australian, 18,490;31 Indian, 67,340; local Volunteer troops, 14,382; a total of 138,708, of whom more than 130,000 became prisoners. The Japanese suffered 9,824 battle casualties during this period. They had evolved no new principles of warfare, but their tactics had been far more flexible than those employed by the defenders.

–:–

On the morning of 16th February a Japanese officer arrived at the Australian headquarters with instructions that the general officer commanding should present himself to the Japanese military authorities with his senior commanders. Brigadier Callaghan32 responded to this summons, accompanied by Brigadiers Maxwell, Taylor and Varley, Colonels Thyer and Kent Hughes, and Captain Geldard.33 Objections by the Australian officers to their troops being herded into the Raffles College area, and being deprived of their steel helmets, as was happening at the time, were accepted, and these actions ceased. As an outcome of the meeting the Australian troops were issued with instructions about the surrender of arms and ammunition and were told to remain in their area. Most of the arms, even small arms, had already been put out of action at the time of the surrender. Later in the day a conference of GOCs was held at Malaya Command with the Japanese. General Percival raised strong objections to the order that all troops would move to Changi on the following afternoon without their arms and equipment, but carrying ten days’ rations. The Japanese insisted that the order must be obeyed but allowed a certain number of trucks to carry the rations. The move took place the following day. To some of the troops the long and humiliating march to Changi was almost more than they were able to bear in their weakened state. They were cheered, however, by the kindness of the Asian people who

pressed gifts on them as they marched. Many units did not reach the area until the early hours of the following morning.34

–:–

The fall of Singapore, coming at a time of political as well as military crisis, was a heavy blow to Mr Churchill personally as well as to the prestige of British arms. As against this, Britain had gained, by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, an ally whose resources, if sufficient time could be won in which to develop and apply them, would bring overwhelming strength to the struggle against the Axis powers. In President Roosevelt, Churchill had gained a warm-hearted and understanding friend.

I realise how the fall of Singapore has affected you and the British people (cabled the President on 19th February). It gives the well-known back-seat driver a field day, but no matter how serious our setbacks have been – and I do not for a moment underrate them – we must constantly look forward to the next moves that need to be made to hit the enemy. I hope you will be of good heart in these trying weeks, because I am very sure that you have the great confidence of the masses of the British people. I want you to know that I think of you often, and I know you will not hesitate to ask me if there is anything you think I can do. ... Do let me hear from you.35

–:–

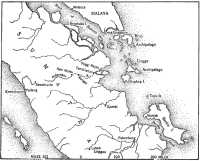

The seas between Singapore and Sumatra and Java were dotted for several days with small craft as those who had got away in the official groups, and some making individual endeavours, sought to run the gauntlet of Japanese air and sea forces in the area. The official evacuation had been carried out in a confused way as men sought to find the craft to which they were allotted, but which had become dispersed under the Japanese bombardment of Singapore and its seafront. The 2/3rd Reserve Motor Transport Company, having no role once the army had concentrated on Singapore Island, was ordered to embark in the steamer Kinta (1,220 tons). The Kinta’s crew dispersed in an air raid, but the Transport Company supplied competent deck and engine-room hands and the Kinta sailed on the 9th and reached Batavia. Desperate men no longer with their units, and civilians not listed for evacuation but determined to escape, also sought to take what opportunity offered. Of the hundred men to have been sent officially from the AIF only thirty-nine, including Broadbent, eventually got away. A patrol boat carrying Admiral Spooner, Air Vice-Marshal Pulford and others was forced ashore on a deserted and malarial island in the Tuju group, 30 miles north of Banka Island. There, with few stores and no doctor, eighteen of them died, including Spooner and Pulford, before the survivors were found and taken into captivity by the Japanese.36

General Bennett, Major Moses and Lieutenant Walker, with some planters who had been serving in the Volunteer forces in Malaya, took charge of a native craft and made an adventurous trip to the east coast

of Sumatra. There the three Australians transferred to a Singapore Harbour Board launch, the Tern, and by this and other means crossed Sumatra to Padang, on its west coast.37 There Bennett met other escapers, including Brigadier Paris (12th Indian Brigade) and Colonel Coates (6th/ 15th Indian Brigade) who had fought in his area on Singapore Island; and

he received a telephone call from General Wavell. Bennett and his officers were flown thence to Java, and he then went ahead of them on a Qantas plane to Australia. He reached Melbourne on 2nd March and called on General Sturdee, then Chief of the General Staff.

To my dismay, my reception was cold and hostile (wrote Bennett afterwards). No other member of the Military Board called in to see me. After a few minutes’ formal conversation, Sturdee told me that my escape was ill-advised, or words to

that effect. I was too shocked to say much. He then went on with his work, leaving me to stand aside in his room. This same Military Board had issued a circular not many months before instructing all ranks that, if captured, their first duty was to escape...38

A meeting of the War Cabinet was held and was attended by Sturdee and Bennett, who gave an account of the Malayan campaign. As soon as it was over, without consulting Sturdee, the Prime Minister made a press statement in which he said:

I desire to inform the nation that we are proud to pay tribute to the efficiency, gallantry and devotion of our forces throughout the struggle. We have expressed to Major-General Bennett our confidence in him. His leadership and conduct were in complete conformity with his duty to the men under his command and to his country. He remained with his men until the end, completed all formalities in connection with the surrender, and then took the opportunity and risk of escaping.39

The Mary Rose, carrying Bowden and others, passed unmolested from Singapore Harbour on 15th February through many small and apparently new sampans, manned it was thought by Japanese in Malay clothes. The original plan was that the launch should proceed to the Inderagiri River in Sumatra, whence its occupants presumably could have reached Padang and Java as Bennett had done. It was decided, however, to make for Palembang, in the south-east of the island. At the entrance to Banka Strait before dawn on 17th February a searchlight suddenly shone on the Mary Rose, and two Japanese patrol vessels trained their guns on her. With no white flag to show, the party used a pair of underpants to indicate surrender, and was taken to Muntok Harbour, Banka Island. There, as its members’ baggage was being examined, Bowden remonstrated with a Japanese guard about some article being taken from him. The party was then marched to a hall where hundreds of other civilian and service captives were held. Bowden asked that he be allowed to interview a Japanese officer in order to make known his diplomatic status. Another altercation with a guard resulted. Though Bowden was an elderly, white-haired man, he was punched and threatened with a bayonet, and the guard sought to remove his gold wristlet watch. Then, when a second guard had been brought, he was told by signs that he was to accompany the two. Squaring

his shoulders, he was led from the hall by the guards who carried rifles with bayonets fixed. About half an hour later two shots were heard, and the guards returned cleaning their rifles. It subsequently appeared that the guards kicked Bowden as he was being marched along, made him dig his own grave, and shot him at its edge.

Many others were discovering at this time what it meant to be at the mercy of the Japanese. An outrage had occurred the day before to the survivors from the Vyner Brooke. Those aboard this vessel, which left Singapore on 12th February, included the sixty-four Australian nurses in charge of Matron Drummond40 of the 2/13th Australian General Hospital, who had been ordered out as the enemy pressed on that city. The vessel was bombed and sunk off Banka Island on the afternoon of the 14th. Two of the nurses were killed during the bombing, nine were last seen drifting on a raft, and the others reached land. Of the latter, twenty-two landed from a lifeboat on the north coast of the island, a few miles from Muntok. Although two of them had been badly wounded, they were supported by the others in a long walk along the beach to a fire lit by earlier arrivals from the same vessel, some of them also wounded. On the 16th, when it was found that Japanese were in possession of the island, an officer was sent to Muntok to negotiate their surrender. Some of the women and children in the group, led by a man, set off soon after for Muntok. The Australian nurses stayed to care for the wounded.

About ten Japanese soldiers in charge of an officer then appeared. The men in the party capable of walking were marched round a small headland. To their horror the women saw the Japanese who had accompanied the group wiping their bayonets and cleaning their rifles as they returned. The nurses were next ordered to walk into the sea. When they were knee-deep, supporting the two wounded among them, the Japanese machine-gunned them, and killed all but one. The survivor, Sister Vivian Bullwinkel,41 regained consciousness and found herself washed ashore and lying on her back, while Japanese were running up the beach, laughing over the massacre. After a further period of unconsciousness she found herself on the beach surrounded by the bodies of those who had fallen with her.

I was so cold that my only thought was to find some warm spot to die (she related). I dragged myself up to the edge of the jungle and lay in the sun where I must have slept for hours. When I woke the sun was almost setting. I spent the night huddled under some bamboos only a few yards from my dead colleagues, too dazed and shocked for anything to register. Next morning I examined my wound and realised I had been shot through the diaphragm and that it would not prove fatal. For several days I remained in the jungle. I found fresh water where I could get a drink and have a bath. ... On the third day, driven by hunger, I went down to the lifeboat to see if there were any iron rations in it. ... A voice called

“Sister”, and I found an Englishman there. ... After machine-gunning the sisters the Japanese had bayoneted the men on stretchers. He too had been bayoneted through the diaphragm, and left for dead.42

Sister Bullwinkel and the Englishman were again taken captive, about ten days later. He died during internment, but Sister Bullwinkel, despite her wound and the sufferings of the prisoner-of-war period, survived and at length returned to Australia. Among those who died in the massacre was Matron Drummond of the 2/13th A.G.H. Matron Paschke43 of the 2/10th A.G.H. was among the nine who drifted from the Vyner Brooke and were not seen again.

The escapers generally from Singapore were broadly in three categories – those who had deserted or had become detached from their units during hostilities; those officially evacuated; and those who escaped after Singapore fell. As has been related, the official evacuation was a confused undertaking. For many of those chosen to leave – mostly women and children, nurses, specialists, and representatives of various units to form experienced cadres elsewhere – the transport which was to be available could not be found when the parties had been organised. The servicemen among these were given the choice of rejoining their units (as Kappe and most of his signals party had done) or of escaping on their own initiative. Two naval gunboats and four small converted river steamers in which evacuees eventually left Singapore were bombed and sunk, but many of these, and others, survived the misfortunes which befell them.

The dividing line between desertions and escapes was in some instances indefinite, particularly as a report that the “cease-fire” on Singapore Island was to take effect as from 4.30 p.m. on 15th February had gained wide circulation and many acted on it in good faith.44 Some, as the plight of the city worsened, consciously deserted. Once the fighting had ceased, others felt free to get away if they could. Thus before and after capitulation Singapore’s shores were combed for craft of any kind which gave hope of escape. The extent of the movement from the island is indicated by the fact that although many who took part in it died and others were captured, about 3,000 reached Java, Ceylon and India through Sumatra.

South and west of Singapore Island the seas are strewn with islands. It was chiefly by way of these that hundreds of craft – sampans, tongkangs, junks and European craft from launches to gunboats – were navigated with varying degrees of skill, or drifted under the influence of wind and currents, towards Sumatra. Many of their occupants owed their lives to Indonesian villagers and others who gave generously of their frugal resources, and in some instances risked their lives to aid them;45 to the help

and hospitality of the Dutch;46 and to selfless efforts by servicemen and civilians who voluntarily or officially acted as part of the escape organisation. Many escapers were drowned; others were killed by bombs and bullets; some as has been shown died at the hands of the Japanese, or of disease and starvation. Most of those who reached Sumatra were evacuated through the west coast port of Emmahaven, a few miles from Padang.

Two officers became principally active in organising aid for the participants in the strange migration. Captain Lyon47 of the Gordons, assisted by a Royal Army Medical Corps private, established a dump of food and a shelter hut on an uninhabited part of an island near Moro, in the south-western part of the Rhio Archipelago. Here, until the evening of 17th February, first aid and sailing directions were given, and rations were provided for the next stage of the journey. Even after Captain Lyon and his assistant left, others got food and instructions left behind in the hut.

Meanwhile Major H. A. Campbell, of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, had arranged with the Dutch authorities in Sumatra means whereby transport, food and clothing were provided. The three main routes used were from the south through Djambi (the first to be closed by the Japanese); through Bengkalis Island to the north-west; and, in the main up the Inderagiri River to Rengat, thence by road to a railhead at Sawahlunto. All three routes led to Padang.

It was the Rengat route that by constant travel and personal contact Campbell organised. Instructions about the route and navigation of the Inderagiri were supplied at Priggi Rajah, at the mouth of the river. At Tambilahan a surgical hospital was set up and further aid was given. Escapers were rested and re-grouped into suitable parties at Rengat, and Ayer Molek nearby. Though the Dutch themselves were endangered by the Japanese, now invading Sumatra, a generous number of buses was made available to carry the escapers to the railhead. A British military headquarters was set up at Padang to handle evacuations, and help the Dutch defend the town if necessary. Naval vessels and a number of small craft took parties thence to Java. Two ships left for Colombo and one, with Colonel Coates, formerly of the 6th/15th Indian Brigade, as officer-in-charge of 220 troops aboard, got there. The other, whose passengers included Brigadier Paris and his staff, was sunk on the way.48

The behaviour of the escapers varied greatly. Some, generally regarded as being among the deserters, and including Australians, blackened the reputation of their fellow countrymen and prejudiced the chances of those

who followed.49 Among those whose courage and resource gained them distinction were Lieut-Colonel Coates,50 of the Australian Army Medical Corps, and Captain W. R. Reynolds, an Australian who had been mining in Malaya. Coates was among those of a medical party evacuated from Singapore whose vessel was bombed and disabled, but who reached Tambilahan in a launch. There, aided by other doctors, he carried out a series of operations on wounded people at what became one of a chain of hospitals established by the Royal Army Medical Corps across Sumatra to Padang. Eventually he remained in Padang, with a Major Kilgour of the British medical corps, looking after troops not evacuated.

Reynolds had left Malaya aboard a 90-ton former Japanese fishing boat. On his way he picked up and towed to Sumatra a motor vessel whose engines had failed. Aboard her were 262 Dutch women and children. When Reynolds heard that a large party of evacuees was stranded at Pulau Pompong, in the northern part of the Lingga Archipelago, he made two trips back into the danger zone to evacuate them. Then he placed his vessel at the disposal of the Dutch authorities, and is credited with having helped 2,000 people to Sumatra. On 15th March, when Japanese troops were expected to arrive next day at Rengat, he was officially advised to leave. After a hazardous trip up the east coast of Sumatra he reached India.

Travelling in a launch owned by the Sultan of Johore which had been manned by two Royal Navy officers and a crew, Colonel Broadbent made an adventurous trip to Sumatra, and landed at Tambilahan. It was this launch which picked up Lieut-Colonel Coates and his party whose vessel, as mentioned, had been bombed and disabled on its way from Singapore. Broadbent attended to the housing of about 60 Australian soldiers at Tambilahan. He then went to Rengat, took part in establishing a collecting station, and became responsible for staging a growing number of people to Padang. There he handed over to Brigadier Paris (who at this stage had not left) responsibility for all but about 125 Australians who had reached this point. Other Australians had already been sent forward and had left Sumatra by ship. At length Broadbent and the substantial group of Australians under his command reached Tjilatjap on the south coast of Java, where they and others boarded a fast cargo ship, the Van Dam, one of the last vessels to leave for Australia. After picking up on the way five survivors (two of them Australians) of those aboard a vessel which had left a few hours ahead of her, the Van Dam reached Fremantle on 6th March.

–:–

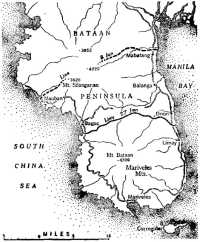

During and after the collapse of resistance in Singapore largely because of the imminent failure of its water supply, the American-Filipino army of 80,000 troops pent up in the Bataan Peninsula with 26,000 refugees

was being starved into submission. Pre-war plans had provided that six months’ supplies for 43,000 men should be stored in the peninsula at the outbreak of war but

MacArthur’s order to fight it out on the beaches had invalidated this plan, and when war came supplies and equipment were moved forward to advance depots to support the troops on the front lines.51

On 3rd January there were only 30 days’ field rations for 100,000, and soon the daily allowance of food was reduced to a dangerously low level.

The Japanese plan provided for the capture of Luzon by the end of January. This would release the 48th Division which, as mentioned, was to take part in the invasion of Java. Late in December, however, the invasion of Java was brought forward one month on the time-table and early in January preparations were being made to transfer the 48th Division, in replacement of which General Homma, commanding the XIV Japanese Army, received the 65th Brigade, of six battalions. Soon Homma had only a division and a half to oppose 80,000 troops in Bataan, 12,000 on Corregidor, and the three Philippine divisions in the central and southern islands.

However, on 9th January, Homma, whose staff greatly under-estimated the strength of MacArthur’s force, launched an attack by three regiments against the Bataan line. After thirteen days of fierce fighting the weary defenders withdrew to a line 12 miles from the tip of the peninsula. The Japanese attacked again but, after three weeks, had made no real progress against a line manned by far stronger forces than their own and well supported by tanks and artillery. On 8th February Homma ordered his force in Bataan to fall back and reorganise and appealed to Tokyo for reinforcements. Battle casualties and tropical disease had reduced the XIV Japanese Army to a skeleton. After the war Homma told an Allied Military Tribunal that if the American and Filipino troops had launched an offensive in late February or in March they could have taken Manila

“without encountering much resistance on our part”. From the end of February until 3rd April there was little contact between the opposing armies.

Meanwhile, on 8th February, seven days before the surrender at Singapore, President Quezon had proposed that an agreement be sought with Japan whereby the American troops be withdrawn from the Philippines and the Philippine Army disbanded. This proposal was contained in a message from the American High Commissioner, Mr Francis B. Sayre, supporting the proposal, if American help could not arrive in time, and by one from MacArthur in the course of which he said:–

Since I have no air or sea protection you must be prepared at any time to figure on the complete destruction of this command. You must determine whether the mission of delay would be better furthered by the temporizing plan of Quezon or by my continued battle effort. The temper of the Filipinos is one of almost violent resentment against the United States. Every one of them expected help and when it has not been forthcoming they believe they have been betrayed in favor of others. ... So far as the military angle is concerned, the problem presents itself as to whether the plan of President Quezon might offer the best possible solution of what is about to be a disastrous debacle. It would not affect the ultimate situation in the Philippines for that would be determined by the results in other theatres. If the Japanese Government rejects President Quezon’s proposition it would psychologically strengthen our hold because of their Prime Minister’s public statement offering independence. If it accepts it we lose no military advantage because we would still secure at least equal delay. Please instruct me.52

Roosevelt promptly sent a long telegram to MacArthur in the course of which he ordered that American forces must keep the flag flying in the Philippines as long as any possibility of resistance remained. MacArthur was authorised, however, to arrange for the capitulation of the Filipino elements “when and if in your opinion that course appears necessary and always having in mind that the Filipino troops are in the service of the United States”. Roosevelt added:–

The service that you and the American members of your command can render to your country in the titanic struggle now developing is beyond all possibility of appraisement. I particularly request that you proceed rapidly to the organization of your forces and your defenses so as to make your resistance as effective as circumstances will permit and as prolonged as humanly possible.

If the evacuation of President Quezon and his Cabinet appears reasonably safe they would be honoured and greatly welcomed in the United States. They should come here via Australia. This applies also to the High Commissioner. Mrs Sayre and your family should be given this opportunity if you consider it advisable. You yourself, however, must determine action to be taken in view of circumstances.

By the beginning of March the troops on Bataan were receiving only enough food to keep them alive. The cavalrymen shot their horses and they were eaten; there was much malaria and a shortage of quinine; dysentery was widespread. Resistance could not last much longer.