Chapter 18: Rabaul and the Forward Observation Line

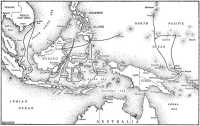

Eastward of the Malay Peninsula the Japanese, having captured Tarakan and Menado on 11th January, were ready in the last week of January to thrust their trident farther south. One prong was aimed at Kavieng and Rabaul, one at Kendari on the south-eastern coast of Celebes, and, later, Ambon on the opposite side of the Molucca Sea, and one at Balikpapan in Dutch Borneo, the site of big oil refineries. These advances into Dutch and Australian territory would carry the Japanese forces across the equator, and establish them in bases whence they would advance to the final objectives on the eastern flank – the New Guinea mainland, and Timor and Bali, thus completing the isolation of Java.

The capture of Rabaul, Kavieng, Kendari and Balikpapan were to take place on the 23rd and 24th January; the advance to the final objectives was to begin about four weeks later. In this phase, as always throughout their offensive, the length of each stride forward was about the range of their land-based aircraft. Thus aircraft from one captured base would support the attack on the next. If no such base was available, carrier-borne aircraft were employed.

–:–

As an outcome of the Singapore Conference of February 1941 and discussions between the Australian Chiefs of Staff and Air Chief Marshal Brooke-Popham, the Australian War Cabinet had agreed to send an AIF battalion to Rabaul, capital of the Mandated Territory of New Guinea. It decided also to encourage “unobtrusively” the evacuation to the mainland of women and children not engaged in essential work in New Guinea.

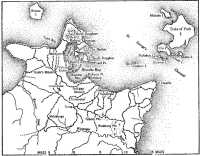

Rabaul, situated on the Gazelle Peninsula, lies on Blanche Bay, inside the hooked north-eastern tip of New Britain, largest and most important island of the Bismarck Archipelago. Formerly part of German New Guinea, the island had been seized in September 1914 by an Australian Expeditionary Force under Colonel Holmes,1 and remained under military government until May 1921.2 In fulfilment of a mandate from the League of Nations, Australia then established a civil administration throughout the Territory. This included a district service which offered unusual opportunities for adventure and advancement.

New Britain is crescent-shaped, 370 miles long with a mean breadth of 50 miles, with a rugged range of mountains along its whole length. Most of the coconut and other plantations near Rabaul were served by roads, but others, scattered along the coastal areas in the western part of the island, were reached principally by sea. New Britain’s climate is

The Japanese advance through the Netherlands Indies and to Rabaul

no worse nor better than that of thousands of other tropical islands, with a moderately heavy rainfall, constant heat, and humidity.

Lieut-Colonel Carr’s 2/22nd Battalion of the 23rd Brigade arrived during March and April 1941 to garrison this outpost, protect its airfields and seaplane anchorage, and act as a link in a slender chain of forward observation posts which Australia was stringing across her northern frontiers. The one other military unit in the territory, apart from a native constabulary, was a detachment of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles, comprising some eighty men, raised by Lieut-Colonel Walstab,3 the Superintendent of Police, for part-time training soon after the outbreak of war in 1939. Until December 1941, other small units arrived to swell Carr’s battalion group. They were principally a coastal defence battery with two 6-inch guns and searchlights under Major Clark,4 in March and April (sent partly because of the attack by German raiders on Nauru Island in December 1940); two out-dated 3-inch anti-aircraft guns under Lieutenant Selby5 (two officers and fifty-one others) on 16th August; and the 17th Anti-Tank Battery (six and 104) under Captain Matheson6 on

29th September. Other detachments included one from the 2/10th Field Ambulance under Major Palmer7 and six nurses.

The harbour which the little force was to defend lies in a zone containing several active volcanoes, some of which had erupted in 1937. Blanche Bay contains two inner harbours, Simpson and Matupi, and forms one of the best natural shelters in the South Pacific, capable of holding up to 300,000 tons of shipping. The inner part of the bay is almost surrounded by a rugged ridge which rises at Raluana Point, reaches a height of about 1,500 feet north of Vunakanau airfield, then decreases, as it swings north, to about 600 feet west of Malaguna. Farther north the ridge rises sharply to three heights which dominate the north-eastern part of the bay – North Daughter, The Mother and South Daughter. On the southern slopes of South Daughter lies Praed Point, overlooking the harbour’s entrance, where the coastal battery had been established. On the northern shores of Simpson Harbour, between the slopes of North Daughter and The Mother, was a flat stretch of ground up to three-quarters of a mile wide on which lay Rabaul and Lakunai airfield. Overlooking the town was the volcano Matupi, barren and weather-beaten, from whose crater from mid-1941 to October that year poured a mighty column of black volcanic ash. Cheek by jowl with Matupi was the gaping but idle crater of Rabalanakaia, from which Rabaul derives its name.

The European population of Rabaul, amounting to about 1,000,

was well served by two clubs, three hotels and three European stores (wrote Lieutenant Selby) but the main shopping centre consisted of four streets of Chinese stores where the troops could spend their pay on a multitudinous variety of knickknacks to tempt the eyes of the home-sick soldiery. In the centre of the two was the Bung, the native market, where the [native people] displayed and noisily proclaimed the excellence of their wares, luscious paw-paws, bananas, pineapples, tomatoes and vegetables. Among the magnificent tree-lined avenues strolled a polyglot population, the local officers looking cool in their not-so-spotless whites, troops in khaki shirts and shorts, the tired-looking wives of planters on a day’s shopping, Chinese maidens glancing up demurely from beneath their huge sunshades, their modest-looking neck to ankle frocks slit on each side to their thighs, bearded German missionaries, hurrying Japanese traders and ubiquitous [natives], black, brown, coffee coloured or albino, the men with lips stained scarlet by betel nut juice, the women carrying the burdens and almost invariably puffing a pipe.8

Rabaul was approached by three main roads – Battery road, which ran from Praed Point Battery past Lakunai airfield to the town; Namanula road, from Nordup on the coast over the Namanula ridge to Rabaul; and Malaguna road. On the outskirts of the township the Malaguna road joined the Tunnel Hill road (a short linking road to the north coast road system), and the Vulcan road which followed the coast past Kokopo until it reached Put Put on the east coast below the Warangoi River. A steeply-graded road named Big Dipper ascended between Vulcan and

Rabaul to Four Ways where a number of secondary roads met, and continued on through Three Ways into the Kokopo Ridge road running north of Vunakanau through Taliligap until eventually it linked with the Vulcan road east of Raluana. Above the ridge the country was flat and covered in thick jungle, but around Vunakanau airfield was a large undulating area of high kunai grass. Narrow native pads or tracks on the Gazelle Peninsula linked village to village, but they were usually steep and tiring to follow. Rivers and streams were plentiful. The smaller streams could usually be crossed by wading, but the larger, of which the Keravat, flowing north, the Toriu, flowing west, and the Warangoi, flowing east, are the principal ones, could be crossed easily only by boat.

In July the 1st Independent Company, commanded by Major Wilson,9 passed through Rabaul on its way to Kavieng, New Ireland, an island slanting across the top of New Britain. Sections were to be disposed for the protection of air bases there and at Vila (New Hebrides), Tulagi (Guadalcanal), Buka Passage (Bougainville), Namatanai (Central New Ireland) and Lorengau (Manus Island), thus farther extending the forward observation line chosen by the Chiefs of Staff until it spread in an arc from east of Australia’s Cape York to the Admiralty Islands, north of New Guinea, a distance of about 1,600 miles.

From July to October Rabaul township was covered by dust and fumes from Matupi, which blackened brass, rotted tents and mosquito nets, irritated the throats of soldiers and civilians and killed vegetation. On 9th September, mainly because of the dust nuisance, the headquarters of the Administrator (Brigadier-General Sir Walter McNicoll10), with some of his staff, was moved from Rabaul to Lae, on the mainland of New Guinea.

That month the Australian Chiefs of Staff recommended to the War Cabinet acceptance of an American proposal to provide equipment, including minefields, anti-submarine nets, anti-aircraft equipment and radar, for the protection and expansion of the anchorage at Rabaul to make it suitable as a base for British and American fleets. The War Cabinet approved the proposals the next month and an inter-service planning team visited Rabaul in November. However, the Australian Chiefs of Staff reported in December, after the outbreak of war, that the project was unlikely to be implemented. They said it was important to retain the garrison at Rabaul as “an advanced observation line”, but its reinforcement was not possible because of the hazard of transporting a force from the mainland and of maintaining it; account should be taken of the psychological effect which a voluntary withdrawal would have on the minds of the Dutch in the Netherlands. The Chiefs of Staff concluded that though the scale of attack which could be brought against Rabaul from bases

in the Japanese mandated islands was beyond the capacity of the small garrison to repel, the enemy should be made to fight for the island, rather than that it should be abandoned at the first threat.

About the same time the War Cabinet, as an outcome of the Singapore Conference of February 1941, agreed to spend £666,500 on behalf of the United States for further development of New Caledonia, south of the New Hebrides, as an operational base. After the Chiefs of Staff had repeated earlier warnings that a division, supported by strong air forces, would be needed to defend the island, the War Cabinet approved the dispatch of the 3rd Independent Company (21 officers and 312 other ranks) to Noumea as a gesture to the Free French and to carry out demolitions if necessary.

Meanwhile, as an outcome of the proposals to expand the Rabaul base, a new commander had arrived at Rabaul. He was Colonel Scanlan,11 an experienced soldier of the 1914-18 war, who took over the already established headquarters of “New Guinea Area” on 8th October.

During December a force of four Hudson aircraft and ten Wirraways commanded by Wing Commander Lerew12 was established at Rabaul. Japanese planes, travelling singly and at great height, began to appear over the area. In mid-December compulsory evacuation to Australia of all European women and children not engaged in essential services began.13

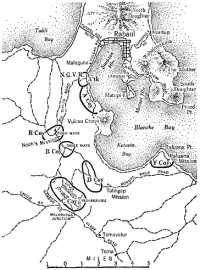

Scanlan, mainly occupied since his arrival in preparing a plan for the defence of Rabaul by a force equivalent to a brigade group and with a greatly expanded scale of equipment, made no radical redeployment of his existing force of 1,400 men. These had been disposed by Carr covering the harbour area, with an improvised company at Praed Point, a company in beach positions at Talili Bay, westward across the narrow neck of the peninsula; one at Lakunai; and others along the ridge around the bay, at Four Ways and defending Vunakanau airfield. On New Year’s Day the Area commander ordered his men to fight to the last and concluded with the words, underlined and in capitals: “There shall be no withdrawal.” The troops lacked regular news of the outside world and the camps were alive with wild rumours, some of them inspired by propaganda broadcasts from Tokyo. Lieutenant Selby felt that a regular official news service would do much to dispel misgivings which Scanlan’s order helped to increase. Scanlan’s headquarters considered such a service impracticable, but a few days later issued an order forbidding troops to listen to Tokyo.14

Other officers who saw as clearly as did the Chiefs of Staff the isolated and vulnerable condition of the force, were sufficiently disturbed by the

lack of a comprehensive scheme for withdrawal to ask Colonel Scanlan to define their functions in the event of the garrison being overwhelmed. The Army Service Corps officer to the force placed before New Guinea Area Headquarters in January a plan to hide portion of the battalion’s two years’ food supply in the mountains, but this precaution, fundamental to continued resistance in that area, or even to survival, seems to have gone almost neglected.15

The first heavy raid on Rabaul came about 10.30 a.m. on 4th January. Twenty-two Japanese bombers, flying in formation at 18,000 feet, made a pattern-bombing attack with fragmentation bombs on Lakunai airfield. More than fifty were dropped. Three hit the runway, seventeen landed on the native compound, killing about fifteen people and wounding as many more, and the rest fell harmlessly in the sea. Two Wirraways which took off from Lakunai failed to intercept the raiders, and Selby’s anti-aircraft battery fired at them, but without effect, their shells bursting far below.16 Late in the day about eleven flying-boats made two runs over the Vunakanau airfield; one pattern of bombs straddled the end of the strip, but the others fell wide of it, killing only one native.

On the 9th a Hudson piloted by Flight Lieutenant Yeowart17 made a courageous flight from Kavieng over Truk, 695 miles north of Rabaul, where he saw a large concentration of shipping and aircraft presumably being assembled for a southward thrust. By the 18th it had been established that the bulk of the Japanese Fourth Fleet was concentrated at Truk and its reconnaissance aircraft were ranging over the area held by the 2/22nd Battalion and the 1st Independent Company. Further bombing raids on the Rabaul area were made during January. The battery on the slopes of North Daughter, although equipped with obsolescent guns and lacking modern predictors, kept the aircraft at a high level.

Soon after midday on the 20th the garrison received warning from Sub-Lieutenant Page,18 a coastwatcher19 at Tabar Island, east of New Ireland, that twenty enemy aircraft were headed towards the town. A further formation of thirty-three approaching from the west was not

detected until it was over Rabaul at 12.40 p.m. A few minutes later a report was received that another fifty aircraft were over Duke of York Island, between Cape Gazelle and New Ireland. When the first formation was sighted two Wirraways were patrolling at 15,000 feet. Six others took off, though the odds seemed insuperable and to the pilots it must have seemed that they were going to certain death. One crashed in the kunai grass near Vunakanau and the others were still attempting to gain height as bombs were falling. Within a few minutes the remaining Wirraways, outnumbered, outpaced and outmanoeuvred, were forced out of action. Three were shot down, two crash-landed, one landed with part of its tailplane shot away, and only one remained undamaged. Six members of the squadron were killed and five wounded or injured in their brave but foredoomed action.

The Japanese now delivered leisurely high-level bombing attacks against shipping, wharves, airfields and other objectives. Heavy bombers, flying-boats and seaplanes patrolled in pageant formation while Zero fighters attacked shipping in the harbour, wharves and military encampments, and performed impudent aerobatics. The Japanese used about 120 aircraft, and the raid lasted three-quarters of an hour. At its end the Norwegian merchantman Herstein lay burning in the harbour, the hulk Westralia had been sunk, and a Japanese heavy bomber, brought down by anti-aircraft fire, was smouldering against the side of The Mother. Only three of Lerew’s aircraft – one Hudson and two Wirraways – remained undamaged. That afternoon he concentrated these at Vunakanau and handed over Lakunai for demolition.

There was a lull in the air attacks on the 21st, but early that morning Scanlan’s headquarters intercepted a message from a Catalina flying-boat that four enemy cruisers were 65 miles south-west of Kavieng, heading towards Rabaul. Scanlan learnt also that Kavieng had been heavily attacked that morning. In the afternoon Carr and his adjutant, Captain Smith,20 were called to Area Headquarters, where Colonel Scanlan informed them that he expected the cruisers to be near Rabaul about 10 o’clock that night, and that he did not intend to allow the troops “to be massacred by naval gunfire”. He ordered Carr to move all troops from Malaguna camp, which lay in an exposed position along the foreshore of Simpson Harbour and an improvised company, under Captain Shier,21 to be sent to Raluana. All other companies were to be prepared for immediate movement. Scanlan added that the troops were to be told that it was “an exercise only” – a decision which resulted in some men going to battle stations lacking hard rations, quinine and other essentials.

That day Lerew began arrangements to evacuate his force. Two Wirraways left in the afternoon for Lae by way of Gasmata, and before daylight on the 22nd the remaining aircraft – a Hudson – had taken off from Vunakanau

carrying the wounded. The airfield was then demolished, over 100 aircraft bombs being buried in the strip and then exploded.

Just before 8 a.m. on the 22nd a further attack was launched by forty-five fighters and dive bombers. Under severe machine-gunning and dive-bombing, Captain Appel’s22 company at Vunakanau, inspired and encouraged by their leader, replied with small arms and machine-gun fire. The dive bombers then turned to the Praed Point battery, easily located from the air because during its construction all the palm trees and tropical undergrowth in the area had been removed, and a wide metalled road ran like a pointer to the emplacements.

The intense bombing and machine-gunning that followed had the effect of silencing the coast defence guns. A heavy pall of smoke and dust, so thick that it resembled a semi-blackout, hung over Praed Point. Some of the dazed survivors said that the upper gun had been blasted out of the ground, crashing on the lower gun and injuring the commander. Eleven men were killed, including some sheltering in a dugout who were buried alive when it collapsed.23

With the silencing of the Praed Point battery, the evacuation of the air force,24 and the cratering of the airfields, Scanlan decided that the justification for the original role of the force no longer existed. He ordered that demolitions be carried out and the township evacuated. At 3.30 p.m. he received news from the anti-aircraft battery position that an enemy convoy was approaching and sent his brigade major, McLeod,25 to confirm it. Through the battery telescope McLeod saw eleven ships “just visible on the horizon, and steaming south-east”. The convoy appeared to him to consist of destroyers, cruisers, transports and one aircraft carrier. About twenty vessels had been counted in the convoy before it disappeared to the south-east half an hour later.

At 4 p.m. the engineers blew a bomb dump within the town. The blast of the great explosion shattered valves of wireless sets in Rabaul and put the radio transmitter at headquarters out of action. The only means then existing of passing messages was by a teleradio, which had been established at Toma. Thus, as Rabaul received confirmation of the arrival of the enemy convoy, its main link with the outside world snapped.

Scanlan, who had now established his headquarters between Three Ways and Taliligap, decided that the enemy’s probable landing places would be within the harbour. To prevent the possibility of part of his force being cut off should the Japanese establish themselves astride the

Dispositions, 2 a.m. 23rd January

connecting isthmus, he decided to move his troops from the Matupi area and concentrate the companies south of Blanche Bay. Major Owen’s26 company at Lakunai, having demolished the airfield there, was moved to prepared positions at Vulcan; “R” Company from Praed Point to a reserve position at Four Ways; and a company under Captain McInnes27 from Talili Bay to a cover-

ing position at Three Ways, about a mile south of Four Ways, to prevent enemy penetration from the beach at Vulcan or from Kokopo, along the Kokopo Ridge road. Appel’s company was to retain its position at Vunakanau for airfield defence. Captain Travers’28 company, supplemented by “R” Company, would remain at Four Ways as battalion reserve, with possible roles of defence against penetration from the Talili or Kokopo areas, or as reinforcement to Appel’s company at Vunakanau. Major Palmer’s detachment of the 2/10th Field Ambulance and the six nurses, who had been running a military hospital on Namanula ridge, he moved with the patients to the comparative safety of Vunapope Mission at Kokopo. Finally he ordered Lieutenant Selby of the anti-aircraft battery to destroy his guns and join Captain Shier’s company at Raluana. The force was now west and south of Rabaul.

It was a sad moment for the gunners to whom the guns had long been a source of pride and inspiration. A round was placed in the chamber and one in the muzzle of each gun. The oil buffers were disconnected and lengths of telephone wire attached to the firing handles. The ring-sight telescope was draped over the muzzle of No. 2 gun and the gun telescopes were removed from their brackets. Everybody took cover. The wires were pulled, there was a roar, then another, and pieces of metal

whistled overhead. When the artillerymen emerged from their shelter both barrels had split and for a couple of feet from the gun mouths they “opened out like a sliced radish”. It was found impracticable to destroy the ammunition, amounting to about 2,500 rounds.

At 5 p.m. Scanlan ordered road-blocks to be dropped on three secondary roads which led to the new positions from Talili Bay, and anti-tank mines to be laid. McInnes supervised this, posting a section on each road-block and sending patrols along Tavilo and Kokopo Ridge roads and down Big Dipper road.

Meanwhile Owen had disposed his company in prepared positions on the Rabaul side of Vulcan crater. He placed the N.G.V.R. and the antitank guns under Lieutenant Clark29 of the 17th Anti-Tank Battery near the Big Dipper-Vulcan road junction; Lieutenant Grant’s30 platoon of the 2/22nd forward on the left, north of the lower slopes of Vulcan; 9 Platoon on the right on two spurs approximately 1,200 yards south-west of Grant’s platoon and 8 Platoon in reserve, about 1,000 yards to the rear of the forward platoons near company headquarters.31 To the fire power of each of the forward platoons Owen added a medium machine-gun, retaining the three mortars near his company headquarters. The men who had been attached from the coastal defence battery and the engineers were disposed between the Vulcan position and the Big Dipper road. By 5 p.m. all were settled in their positions and watching civilians making their way in trucks, cars and on foot along the road to Kokopo under a cloud of black smoke from the burning wharves and the demolitions in Rabaul township.

At Raluana Shier’s improvised company received some slender reinforcement during the day. The men were short of tools and it was not until 11 p.m. that digging of the platoon positions was completed. Soon afterwards Shier ordered a redeployment, placing Lieutenant Henry’s32 platoon right of the Mission with a patrol to the junction of the Vulcan-Kokopo roads, Lieutenant Tolmer’s33 pioneers at the Mission, and Lieutenant Milne’s34 platoon on the left at the Catchment (a small water reservoir), supported by a medium machine-gun manned by five New Guinea riflemen.

Meanwhile the anti-aircraft gunners had arrived at Three Ways. Thence they were ordered by Scanlan to join Shier at Raluana.

My men (wrote Selby afterwards) had had no infantry training – neither had I. ... We climbed back into the two trucks and moved on through Taliligap. A misty rain

was falling, the road was a slippery ribbon of mud and ... lights were forbidden. ... We went at a walking pace down the narrow twisting road, a gunner walking in front with his hand on the mudguard to guide me through the darkness. It was nearly midnight when we reached Raluana and we were given a most welcome cup of soup, our first refreshment since lunchtime. Captain Shier and I walked around the defences. There was no wire on the beach and only one short length of trench had been dug. On Shier’s orders I placed the Vickers gun and its crew on the beach and posted five gunners with rifles to cover it. The rest of us were ordered to proceed to the old German battery position a few hundred yards up the hill where we were to support the troops on the beach.

Soon after midnight Owen’s company, waiting beside Vulcan, heard the hum of an approaching aeroplane and a parachute flare was dropped towards the crater, illuminating the whole harbour. Other flares had been dropped continuously over Vunakanau airfield throughout the night. About 1 a.m. landing craft could be seen making in the direction of the causeway, and red Very lights in Matupi Harbour signalled the success of Japanese landings. At 2.25 the men heard movement and voices within Simpson Harbour and landing craft were seen making towards the left platoon. Corporal Jones,35 patrolling forward of the company positions, fired a Very light at 2.30 – a signal to his comrades that the Japanese had arrived at the near-by beach.

The Australians could see the landing craft and their occupants silhouetted against a boat and dumps ablaze in Rabaul harbour and township. Lieutenant Grant immediately telephoned Major Owen, who passed the news to battalion headquarters.

We could see dimly the shapes of boats, and men getting out (said one soldier later). As they landed the Japanese were laughing, talking and striking matches .. . one of them even shone a torch. ... We allowed most of them to get out of the boats and then fired everything we had. In my section we had one Lewis gun, one Tommy gun, eight rifles. The Vickers guns also opened up with us. We gave the mortars the position ... and in a matter of minutes they were sending their bombs over.36

The beach was wired forty yards ahead of the platoon’s position and the mortars, accurately directed by Sergeant Kirkland,37 were landing their bombs just in front of the wire. Two attempts to rush the positions were frustrated by the intense fire of the Australians. Thwarted in their flank assaults on Owen’s positions, the Japanese now began moving toward Vulcan, away from the wire which stretched across the company front. Soon after 2.30 the right platoon reported that Japanese were moving up the ravines from Keravia Bay. A few minutes later the telephone line between company and battalion headquarters went dead. Some of the Japanese were carrying flags towards which others rallied. They were engaged by rifle and machine-gun fire and immediately halted in the cover of the ravines.

Meanwhile Captain Shier’s company in its hastily and ill-prepared positions at Raluana was faring less well. At 2.45 a.m. Japanese had landed on the beach between Tolmer’s platoon at the Mission and Milne’s at the Catchment. The enemy overran the forward sections of company headquarters and Captain Shier gave the order to withdraw. The company fell back in stages, platoon by platoon, to transport waiting on the Vulcan Ridge road, and began embussing. At 3.30 the Japanese began infiltrating through the position and were fired on by a rearguard section which remained. At 3.50 the last of the company, including the artillerymen, withdrew from Raluana, joining a procession of trucks moving slowly in the darkness up the steep winding track towards Taliligap.

At 4 a.m. a green flare, which appeared to the defenders along Vulcan beach to be the signal for concerted action, was sent up to about 1,000 feet over Rabaul. Soon afterwards a Japanese launch was seen moving along the eastern side of the harbour, clearly indicating that the Japanese were established in Rabaul itself. A string of transports, each about 2,000 tons, entered the harbour from the east and disgorged landing parties. The first transport made towards Malaguna, others for Matupi Island. Some landed troops at Vulcan, Raluana and other places on the Kokopo coast. One party, consisting of a ship’s launch towing two landing barges each containing about twenty men, attempted a landing in front of the Catholic Church between Vulcan and Malaguna. The N.G.V.R’s mortars under Lieutenant Archer38 accurately ranged on the position, one bomb landing in the second barge.

The sun was rising when Grant reported to Owen at 6 o’clock that his supply of ammunition had been exhausted. Two fast trips were made by Captain Field39 and Private Olney40 to replenish it. The barges which had made the original landing on “A” Company’s immediate front had been withdrawn, leaving the casualties behind, but the Japanese could now be seen taking cover in the ravines, and it was clear that further landings, beyond the range of effective mortar fire, had been made on the lower slopes of Mount Vulcan. There the invaders were engaged by Grant’s platoon with small arms and machine-gun fire, and dispersed round the side of Vulcan, losing a machine-gun and crew which Private Saligari41 put out of action with light machine-gun fire.

Soon afterwards Owen’s right platoon reported that enemy patrols were working wide round their right flank, attempting to encircle them. Japanese were moving on the rearward slopes of Vulcan towards Four Ways. Owen decided that his position was no longer tenable: a prearranged attack by Travers’ company from Four Ways had failed to

eventuate, the troops were being attacked by low-flying Japanese planes, transports in the harbour were shelling his positions, and his line of withdrawal along Big Dipper road was endangered. At 7 a.m. he ordered Grant to withdraw his platoon, with the carriers, by road to Four Ways, while the remaining platoons provided covering fire.

Landing craft were now disembarking troops near Big Dipper road, and were being engaged by anti-tank guns. Small merchant ships could be seen berthing at Main Wharf. As Grant’s men clambered aboard the waiting truck, a further four or five landing craft moved towards the beach between Big Dipper road and Owen’s headquarters. The two platoons remaining held their positions until 7.30, when Owen ordered them too to withdraw to Four Ways. Except that it was clear that fighting had ceased at Raluana, Owen had no knowledge of events in other sectors. Consequently he directed the withdrawing troops to move to Tobera, south of Kokopo, if they discovered that Four Ways had been captured. Soon after the order had been given the men began to withdraw through the bush towards Four Ways, under fire from the ships in the harbour, and followed by Owen and Captain Silverman,42 medical officer to the coastal battery, who had established an R.A.P. in the area.

These companies at Vulcan and Raluana had been out of touch with the battalion commander, Carr, and with Scanlan, since soon after 2.30, when the line which ran from Owen’s company at Vulcan through Raluana and thence to Carr’s headquarters at Noah’s Mission, between Three Ways and Four Ways, went dead. At 3 a.m., from his command post now established at Taliligap, Scanlan had ordered Travers’ company to move from Four Ways to prepared positions at Taliligap covering the Kokopo Ridge road. An observation post at Taliligap commanded a view of both Lakunai and Vunakanau airfields and of the whole harbour. At dawn an assembly of thirty-one vessels could be seen at the entrance to the harbour. Steaming along the harbour in line abreast were three destroyers, and landing craft or barges dotted the deep waters and foreshores of the harbour. A merchant ship was berthed at the Government Wharf. As it was evident that Owen’s company must be hard pressed, Lieutenant Dawson,43 the young and enterprising Intelligence officer of the 2/22nd Battalion, was sent to lead it out from its beach positions along a track which passed through Tawliva Mission and led down to the beach.

I set off in a car with a driver and an Intelligence orderly (said Dawson later). On turning the last curve before the mission we saw there in the middle of the road a full platoon of Japs and several natives. With them was one of the local German missionaries shaking hands with an officer who appeared to be the platoon command. I had seen the German earlier in the morning and he had then impressed me as being very pleased about something. ... The impression I got was that the natives had led the Japs up the ... track because it was utterly impossible to find it from the lower end. That was the reason I was going down to lead “A” Company out. The Japs opened fire at a range of about 50 yards. The car stopped.

The Australians dismounted. Private “Curly” Smith44 was killed as he rounded the front of the car, but the driver, Private Kennedy,45 and Dawson escaped into the bush. Carr, unaware of Dawson’s encounter with the Japanese and his failure to reach Owen, had rung Scanlan at 6.30 and informed him that Owen’s company was withdrawing. Scanlan thereupon ordered McInnes’ company, astride the main Kokopo road at Three Ways, to cover the withdrawal of Owen’s company. At 6.45 Scanlan decided to withdraw his own headquarters to Tomavatur.

By 3.10 Travers’ company, which had been ordered to the pre-arranged Taliligap position astride the Kokopo Ridge road, had arrived in its position and was digging in. Travers disposed his men on a front of about 2,000 yards astride the Kokopo Ridge road. He placed a platoon under Sergeant Morris46 on the left covering the road and approximately 300 yards of front to the forward slopes of a knoll; Lieutenant Lomas’47 from the Kokopo Ridge road to the left of a large re-entrant on the reverse slope of the knoll; and Lieutenant Donaldson’s48 from the re-entrant to Vunakanau. Company headquarters were sited in rear of Morris’ platoon, with the anti-tank guns, machine-guns and mortars nearby. At 5 a.m. Travers sent a patrol from Morris’ platoon to Taliligap Mission.

Half an hour later the survivors of Shier’s company from Raluana began to arrive after a difficult trip without lights in the darkness. Some trucks had overturned on the slippery road. The survivors’ arrival was reported to Carr who ordered that Tolmer’s platoon join Travers and the remainder continue to Four Ways and join the battalion reserve.

Thereupon Travers ordered Tolmer to a position forward on his left flank near Gaskin’s House. The area was under low-flying machine-gun attacks and light bombs were being dropped. At 8.15 telephone communication with battalion headquarters failed. It was never restored.

During the morning a detachment of Fortress Signals at Toma managed to dispatch a message by teleradio (drafted by Lieutenant Figgis,49 the Area Intelligence Officer) to Port Moresby to the effect that a “landing craft carrier” was off New Britain and that a landing was taking place. The message was corrupted during transmission and as received at Port Moresby merely reported,: “Motor landing craft carrier off Crebuen [Credner] Island.” It was Rabaul’s last message.

Meanwhile McInnes and Appel at Three Ways and Vunakanau respectively, and the Reserve Company at Four Ways, had seen no enemy

troops since the action began, although all areas had been attacked from the air. The company under Appel in prepared positions round Vunakanau airfield was constantly dive-bombed and machine-gunned throughout the morning. At 7.20 a.m. Captain Smith, the adjutant, phoned to Appel that battalion headquarters was closing at Noah’s Mission and moving southward to Malabunga junction. Appel passed the message to Scanlan.

Soon after 8.30 Grant’s platoon from the Vulcan position arrived at Three Ways. The crews of two machine-guns which McInnes had posted along the Kokopo Ridge road to hold the line between his own and Travers’ companies now reported that they had been surrounded, and were forced to withdraw under covering fire from McInnes’ mortars. Soon afterwards Three Ways came under rifle and automatic fire from a ridge about 800 yards distant.

McInnes’ position was rapidly becoming untenable. At 8.45 Appel telephoned McInnes, who informed him that Grant’s platoon had passed through Three Ways and was moving along Bamboo road in the rear of Vunakanau. He then said that his own company would have to withdraw. Appel asked him to hold his position if possible, and asked that Major Mollard,50 who had been sent forward by Carr to coordinate the defence of the Kokopo Ridge road by the two companies there, be brought to the telephone. When Mollard arrived Appel suggested that if McInnes could hold his present position and close the gap between his own and Travers’ company on the Kokopo Ridge road, the front would possess good length and depth, and force the enemy to come out into the kunai grass country. On the other hand, he added, if McInnes withdrew the whole front would have broken down.

Mollard, after reiterating the necessity to withdraw, ordered Appel to cover McInnes’ withdrawal and that of the remnant of Owen’s company under Grant, and then to move his own company to an area at the junction of Bamboo and Tavilo roads, south of Vunakanau.

Appel now sent a dispatch rider to battalion headquarters at Malabunga junction. The rider found the headquarters at Glade road, 500 yards from the junction, and returned with a message that the battalion would move to the Keravat River and take up new positions; meanwhile Appel’s company should continue to hold the junction of Bamboo and Tavilo roads until all transport of the withdrawing companies liad passed through. It was the last communication Appel had with his battalion headquarters.

Mollard, now concerned lest the line of withdrawal of “R” Company through Three Ways be cut, hastened by car to Four Ways to order its evacuation. It was then about 9 a.m. All transport available, no matter to which company it belonged, was requisitioned and troops were bundled into the vehicles in whatever order they arrived. Sergeant Walls51 recalled

afterwards that he himself was clinging to the side of a taxi containing a corporal and six members of his section. It had gone about 400 yards from Four Ways when the convoy halted and he was ordered by Major Mollard to move towards Malabunga, making a wide circuit of the road which the enemy were wrongly believed to have crossed.

About 10 o’clock Mollard ordered the withdrawal of McInnes’ company from Three Ways. Soon the troops were speeding along the road in trucks continually harassed from the air.

The sense of urgency in the forward area was soon transmitted to the rear. Can had moved his headquarters from Noah’s Mission to Glade road about 8 o’clock. Thenceforward he was out of touch with his forward companies except by dispatch riders, although telephone communication was maintained between the battalion commander and Scanlan throughout. Soon after 9 o’clock rumours reached battalion headquarters that the Japanese were coming through “in thousands” and could not be held. Enemy aircraft, flying low, were machine-gunning and shelling all roads, Vunakanau airfield and battalion headquarters area. As if to confirm the rumours, trucks now began to come through the fire and were seen speedily withdrawing along Glade road towards Toma. The adjutant, Captain Smith, and the regimental sergeant-major, Murray,52 attempted to halt some of the trucks and establish a defensive position near Glade road, but the men said the enemy was advancing quickly, and some trucks refused to stop. Other trucks followed the early arrivals and, since serious congestion appeared likely on the narrow road, offering a target for further air attacks, Can ordered the withdrawal to continue to Area Headquarters at Tomavatur.

After a telephone discussion with Carr, Scanlan – as much out of touch with the progress of fighting as his battalion commander because of the breakdown in communications, but who had observed the trucks streaming down the road past Tomavatur towards Toma – decided that it was useless to prolong the action. He ordered Carr to withdraw his battalion towards the Keravat River. Carr pointed out that this was now impracticable, since his battalion was already spread out in other directions. He suggested that the northern companies withdraw to the Keravat, the southern to the Warangoi, both to hold those positions as long as they could; and the centre companies to move back along the Malabunga road. Scanlan agreed, adding that it would now be “every man for himself”, which Can took to mean withdrawal in small parties. Carr gave these orders to his battalion signallers for transmission to all companies. To avoid congestion at the road junction he posted a picquet at the Malabunga road junction with orders to direct, in accordance with the agreed plan, any trucks arriving there.

It remains to record the experiences of Travers’ company on the Kokopo Ridge road, out of touch with its headquarters since soon after 8 a.m.,

with its line to Three Ways severed, and faced with the possibility of attack from the rear by troops advancing from Vulcan. At 9 o’clock Travers ordered a redeployment to meet the new threat, placing Lomas’ and Morris’ platoons on a knoll 500 yards to the rear of his previous position facing the original left flank. Lieutenant Garrard,53 with company headquarters, took up a position between these two platoons and Tolmer’s pioneers; Donaldson’s remained in its previous position facing Kokopo, with the task of flank protection.

At 11 o’clock the pioneers moved forward of Gaskin’s house to a knoll astride the Kokopo Ridge road, 400 yards farther forward along the road to Kokopo. At 11.30 Tolmer’s batman, Private Holmes,54 called out that two natives of the island were approaching. Tolmer, who immediately joined him, saw the two wearing white mission lap-laps, closely followed by Japanese. He fired on the natives, killing one, whereupon his men joined in and killed the other and, Tolmer estimated, ten Japanese. Simultaneously Japanese began to move in on Donaldson’s platoon and company headquarters. Those encountered by Tolmer’s platoon succeeded in occupying Gaskin’s house, where they were held; others worked round the left flank, cutting off the company from its trucks.

At midday Travers withdrew Tolmer’s platoon to Taliligap, where, half an hour later, it came under machine-gun fire from a knoll to the right of Taliligap. At 12.45 p.m. Travers ordered Lomas and Tolmer to withdraw their platoons through Donaldson’s positions towards Vunakanau, and attempt to contact Appel’s company, believed still to be occupying the airfield, on which aircraft could be seen dropping bombs. Heavy fire could be heard near Morris’ and Garrard’s positions.

Lomas withdrew his platoon in good order, passing behind Donaldson’s perimeter defence and heading in the direction of Vunakanau as directed. He was not again seen by Travers. Tolmer reached Donaldson at 1.15, with orders from Travers to hold on until the rest of the company had passed through, and took up a position on the right flank facing Taliligap. There was a lull, while both sides regrouped; then at 2 o’clock Travers, who had throughout proved himself a fearless and capable leader, ordered the two covering platoons to join him at Taliligap heights. There Donaldson received orders to advance along the Kokopo Ridge road and recapture two M.M.G. trucks which had been cut off with the company’s transport 300 yards west of Taliligap.

Just before 3 p.m. Donaldson set off along the road, covered by fire from Tolmer’s pioneers. The men came under light small arms and mortar fire before reaching a platoon on the left of the road, where Donaldson asked Sergeant Morris to support his advance with fire from the left flank.

In the subsequent advance Lance-Corporal Simson55 was outstanding. He made his way forward, skilfully using all available cover, and came upon ten Japanese into whom he fired with his Tommy gun, accounting for all of them. Advancing farther, he killed a similar group. Both trucks were brought back, one of them driven by Private Clinton56 under very heavy small arms and mortar fire. Enemy troops encountered were checked by sub-machine-gun fire from Donaldson’s platoon, in which Corporal Sloan,57 another Tommy-gunner, was a dominating figure. When the counter-attack had ended, Donaldson estimated the enemy casualties at fifty. His own platoon had suffered none.

At 3.10 Travers ordered the company to withdraw through the kunai to Glade road, and his men did so, closely pursued by Japanese who at times reached within 100 yards of the rear of the column, only to be checked by sub-machine-gun fire. Under fire from mortars and machine-guns, and constantly harried from the air, the company reached Toma road at 5 p.m. There a bridgehead was formed and in a deep valley a mile to the west the men bivouacked for the night.

Organised resistance to the Japanese on New Britain had now ended. The force split up into small parties and withdrew south-west to the north coast and south-east to the south coast. The strength of the force at Rabaul on 23rd January was estimated at 76 officers, 6 nurses and 1,314 others. Of this number 2 officers and 26 men were killed during the fighting that day. Some 400 subsequently escaped to Australia; about 160 were massacred by the Japanese at Tol in early February. The remainder became prisoners. The special circumstances in which the force was placed, and the ordeal and fate of many of its members are narrated separately in Appendix 4 of this volume.

–:–

The Japanese force which undertook the capture of Rabaul was the Nankai or South Seas Force, commanded by the slight, balding Major-General Tomitaro Horii, who had originally commanded the 55th Division, whence the principal units of the South Seas Force had been drawn. The main units of the force, formed in November 1941 to carry out landing operations in cooperation with the Fourth Fleet, were the I, II, and III Battalions of the 144th Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Kusunose; a mountain artillery battalion; the 15th Independent Engineer Regiment; anti-aircraft artillery; and transport and medical detachments, probably about 5,300 strong. Evidently these were supported at the outset by three special naval landing forces, each of about battalion strength. The force had left Japan towards the end of November, rendezvoused in the Bonin Islands area, and on 10th December carried out the landing operations at Guam. Evidently the Japanese expected strong resistance in the

next phase of the operations – or were taking no risks – and allotted a naval force including two aircraft carriers and two battleships to the task.58

The convoy carrying the South Seas Force left Guam on 14th January with a naval escort, being “patrolled continuously” by naval planes until the 17th, when it was joined by the Fourth Fleet from Truk; it then totalled “more than 30 ships” (Dawson from his observation post at Tawliva counted 31 on the morning of the 23rd). While the convoy was at sea aircraft of the 24th Air Flotilla “strafed the enemy’s air bases” at Rabaul, Vunakanau, Kavieng and Salamaua and “shot down about 10 enemy planes over the New Britain Island area on the 21st and 22nd”.

On the afternoon of the 22nd the convoy passed between New Ireland and New Britain, sailing between both islands in clear sight during the daytime in a zigzag movement at reduced speed to kill time. “Undoubtedly,” says the report of the South Seas Force, “the enemy was aware that the convoy entered deep between both islands in the daytime ... but it seemed that they judged this movement of ours meant we would land in the Kokopo vicinity, because the units stationed directly at Rabaul were withdrawn and positions were taken up facing the Kokopo area to the south. Thus, our successful landings were made by taking advantage of the enemy’s unpreparedness at that point.”

Horii landed the I Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Tsukamoto) at Praed Point, the II Battalion and regimental headquarters of the 144th in the vicinity of Nordup. These two battalions advanced rapidly to occupy Lakunai airfield and the Rabaul township. The first wave of the III Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Kuwada) left the stern of the Mito Maru at 0200 and succeeded in making a landing on the beach in the neighbourhood of Kazanto (Vulcan – where Owen’s company was stationed) at 0230, and at Minami Point (Raluana) where they seized “the gun emplacement”.59 The III Battalion started its drive towards Vunakanau but “being blocked by sheer cliffs and unable to find the road shown in the aerial photo60 ... was forced to advance through jungles. Bitter fighting broke out at the landing point of the 9th Infantry Company ... which happened to be just in front of the position which the enemy newly occupied after their change of dispositions.” Another diarist records that during the advance to Vunakanau “there were places on the road where the enemy had abandoned vehicles, where ammunition was scattered about and where due to the pursuit attacks of our high speed Butai [detachment] were pitiful traces of the

confused flight and defeat of the enemy. Leapfrogging all Butai we advanced on foot to the aerodrome and at 1400 hours captured it.” Evidently the resistance in the III Battalion area, where “furious reports of big guns and rifle fire” could be heard from Rabaul, caused some concern, however, and in the afternoon the I Battalion was transferred by water craft from Rabaul to Keravia Bay and strengthened the III Battalion in its thrust towards Vunakanau. Horii ordered the pursuit of the Australians to be continued on foot on the 24th January, and later a destroyer and three transports were allotted to facilitate these operations, which were impeded by the difficult terrain.

During the fighting on 23rd January the Japanese lost 16 killed and 49 “injured” (presumably wounded in action). Eight aircraft (presumably wrecked), two fortress cannons, 2 anti-aircraft guns, 15 anti-tank guns, 11 mortars, 27 machine-guns, 7 light machine-guns, 548 rifles, 12 armoured cars (Bren carriers), 180 automobiles and 17 motor cycles, were reported to have been captured by the invaders.

–:–

Meanwhile, on 21st January, two days before the Japanese landing at Rabaul, Kavieng, 125 miles to the north-west, had been attacked soon after 7 a.m. by about sixty Japanese aircraft, including bombers, dive bombers and fighters.61 The Japanese concentrated their dive-bombing on the town, gun positions on the airfield and along the ridge running laterally to the western beaches, where the 1st Independent Company had established concealed machine-gun positions. The aircraft were met by brisk fire and one crashed into the sea beyond Nusa Island. Soon after the raid began the Induna Star62 cast her moorings at the main wharf and was attempting to reach the comparative safety of Albatross Channel when she was attacked by six aircraft. Although the ship’s Bren gun team under Corporal Reed63 put up a stout defence, during which six of the team were wounded including two mortally,64 control of the vessel was lost and she ran on a reef about two miles south of Kavieng.

By 9 o’clock the aircraft had gone. The defenders of Kavieng accounted for four planes and damaged others during the almost incessant air attacks. Soon afterwards the captain of the Induna Star arrived at Kavieng in a canoe to report the beaching of his ship. He was ordered to return and attempt to bring it back to the wharf. A message was then sent to Rabaul, reporting details of the action, including the supposed loss of the Induna Star.

After visiting the areas occupied by his men that day, Major Wilson concluded that his positions at Kavieng would be untenable should landings be made simultaneously at Panapai and the western beaches. He

decided to move his men from the area except for a portion of Captain Goode’s65 platoon at the airfield and a few other troops required for demolitions in the town. At the civil hospital the wounded had begun to arrive and Captain Bristow,66 ably assisted by Sister D. M. Maye of the Administration’s nursing service, was operating. After consulting them Wilson decided that the seriously wounded should be sent to the near-by Lamacott Mission under the sister’s care.

At 11 a.m. the Induna Star returned, leaking badly and considered unseaworthy by her skipper. However, since she represented the Independent Company’s only means of escape a month’s rations were taken aboard

and the crew was ordered to take the ship to Kaut Harbour, patch the hull, and await orders. During the afternoon the men were moved on foot to camps on the Sook River (adjacent to one set up by the civil administration) and at Kaut overlooking the harbour. Wilson moved his main wireless set to a position of relative safety about half a mile south-west of the airfield, where he established his headquarters. Soon after these moves had been completed a message was received from Rabaul that an enemy force of “one aircraft carrier and six cruisers” was approaching from the north-west.

At 8 o’clock on the 22nd Wilson learnt from Rabaul that no further information had been received, but Rabaul promised to keep in touch with him. It was the last message passed between the two forces. The rest of the day was spent by the Independent Company preparing for an attack, and moving supplies to Sook and Kaut. At 10.30 p.m. the plantation manager at Selapui Island, Mr Doyle, arrived in a motor-boat bringing a report from the company’s outpost that there had been no sign of the enemy. It was dark and raining, but Wilson asked him to return to Selapui, since the outpost was now out of touch by wireless, and warn the men to make for Kaut if they saw Kavieng being attacked. Only Wilson, Lieutenant Dixon,67 three soldiers and five civilians (some of them Catholic priests) remained in Kavieng during the night. The men stayed in two houses close to the water front, so that demolition of the wharves could begin early on the 23rd.

At 3.5 a.m. sounds were heard at Saunders Wharf. Visibility was poor and it was raining lightly. Five minutes later enemy landing barges were reaching the western beaches, Very lights were being fired and there was much shouting and shooting. A few minutes later the house Wilson and its owner were occupying was surrounded but the two men left by car unmolested, except for a few stray and ineffective shots. At the airfield Wilson met Lieutenant Burns68 and ordered him to blow it and the supply dumps. He then drove to the end of the runway and at 3.18 saw and heard the sounds of the demolitions. Captain Goode received severe concussion, but withdrew with all members of his platoon in good order towards a pre-arranged rendezvous at Cockle Creek.

Soon afterwards Wilson arrived at his headquarters south-west of the airfield and after ordering the destruction of the wireless equipment retired also to Cockle Creek. There he found that Dixon and his party had not arrived from Kavieng, and learnt from other reports that the landing had been made by a force estimated between three and four thousand strong.69 Landings at Panapai and the western beaches had not been simultaneous, and it was this fact that had allowed their unimpeded withdrawal. At 6.45, as Dixon still had not arrived, the men began to withdraw towards Sook. As it was impossible to carry the wounded through the thick jungle, they made their way on foot. Corporal Noonan70 gallantly refused assistance though wounded in both legs.

Next morning they met a party sent out by Captain Fraser71 from Sook, and moved there on foot and in canoes. Some of the men arrived during the afternoon, others not until next day, and then almost exhausted.

On the 27th the men learnt that Dixon and his party had been captured at Kavieng. Lieutenant Dennis72 and a civilian arrived from Kaut during the day with news that an enemy aircraft carrier was anchored at Djaul Island and an enemy submarine was patrolling the mouth of the Albatross Channel. Wilson learnt also that the Induna Star was lying on a mudbank in Kaut Harbour. However the new arrivals believed that she could be made seaworthy. The men were now suffering from malaria and diarrhoea, and some of the civilians were complaining that the soldiers’ presence was endangering them. Wilson decided that two courses were open to him: to concentrate his force at Kaut and attempt to refloat the Induna Star in the hope of reaching New Britain, or to move to Lelet plateau, where healthier conditions existed.

An offer by Captain Fraser and Warrant-Officer Harvey73 to take a rescue party to Kavieng and attempt to bring back Lieutenant Dixon was refused, since the reports received were contradictory and the time needed would have endangered the remainder of the company.74 On the 28th, after destroying all equipment too heavy to carry, and leaving the wireless set with the civilians with instructions not to take any action to destroy it until three days had passed, Wilson moved his men to Kaut, and set them to work repairing the Induna Star. It was not until the evening of the 30th that the craft was pumped free of water, her hull patched and the main engine functioning satisfactorily. That morning Wilson had sent Lieutenant Sleeman75 to Sook with dispatches for Moresby about his proposed move to New Britain; in the afternoon Sleeman returned with the news that the wireless had been destroyed, but bringing a message from Army Headquarters, Melbourne, ordering Wilson to “remain and report, also to do as much damage as possible to the enemy”. After conferring with his medical officer, Captain Bristow, Wilson decided that the condition of his men precluded any such role.

They had mostly been struggling through jungle and swamp for nine days (he wrote afterwards); prior to that they had been constantly on duty for many months and were now suffering from fatigue, malaria and dysentery, and skin diseases. Furthermore there was only two months’ supply of food left, including that on the “Induna Star” [and] our only main and effective role, that of observation reports was now impossible. Added to this, our only chance of leaving the island was to go at once before the enemy discovered the whereabouts of the “Induna Star”.

That night Wilson embarked his men, intending to sail down the coast in the darkness and lie up during the day in the hope of reaching the east coast of New Britain. By daylight on the 31st Kalili Harbour had been reached without incident. There Wilson learnt that fighting on New Britain had ceased, that the natives on New Ireland were becoming increasingly

hostile; and that the Namatanai detachment of the Independent Company was believed to be in the mountainous country south-east of Namatanai, with representatives of the civilian administration equipped with a teleradio set “and therefore in a reasonable position”.76 Thereupon Wilson decided to attempt to reach Port Moresby. That night the journey down the coast continued. Early next morning an enemy destroyer was sighted lying inshore about three-quarters of a mile astern. Soon afterwards the destroyer swung out from the shore and set off westwards.

All that day the schooner lay hidden in a harbour near Gilingil Plantation. The night was overcast and Wilson decided to run straight for Woodlark Islands with a favourable wind and a heavy following sea. At 9.30 a.m. on the 2nd, when the ship was some 90 miles south-east of Rabaul, she was sighted by an enemy plane. It circled and machine-gunned the ship without doing serious damage, and then dive-bombed. One bomb struck the Induna Star amidships, destroying the lifeboat and causing a number of casualties. Since the ship was now taking a dangerous amount of water, Wilson considered further resistance useless, and ordered the ship to heave to.

We then received instructions from the enemy to proceed towards Rabaul, which we did slowly, accompanied by enemy planes, all available hands taking shifts on the pumps (wrote Major Wilson). At 1813 hours an enemy destroyer came up to within 500 yards, then sent a boat which took the wounded and officers aboard the destroyer. A line was passed to the “Induna Star” which was towed. The next morning we were lying off the eastern end of New Ireland when all but six of the personnel were transferred to the destroyer from the “Induna Star” and we proceeded to Rabaul and captivity. Three men had been killed during the action and these had been buried at sea from the “Induna Star”; one of the wounded died on the enemy destroyer during the night and was buried immediately, honours being paid by the enemy, myself giving what I remembered of the burial service.77

Meanwhile on the 23rd and 24th January Japanese forces had landed at Kendari and Balikpapan. The force that was to take Balikpapan – the 56th Regiment plus the 2nd Kure Naval Landing Force – set out from Tarakan in 16 transports on 21st January. An American submarine, American flying-boats and Dutch aircraft reported the convoy, and on the evening of the 23rd Dutch aircraft destroyed the transport Nana Maru. That night the convoy began disembarking its troops at Balikpapan, under the protection of the cruiser Naka and seven destroyers. There was no opposition ashore, the Dutch garrison having withdrawn inland after damaging the oil installations.

Since early in January Admiral Glassford’s American naval force, based at Surabaya, had been allotted a general responsibility for the eastern flank from Bali to eastern New Guinea, while the Dutch squadron operated

in the centre and the British-Australian squadron on the west. Admiral Glassford’s squadron – two cruisers and four destroyers – had learnt of the advance of the Japanese convoy on the 20th, when it was anchored off Koepang. The destroyers set out towards Balikpapan but a mishap delayed the cruisers. After midnight on the 23rd–24th, as the Japanese were disembarking, the destroyers were nearing Balikpapan. Since the Dutch had set fire to the oil tanks the American destroyers as they approached could see the enemy’s transports silhouetted. They attacked in the early hours of the 24th. The Japanese were taken completely by surprise. The escorting destroyers raced off searching for imagined submarines while the American destroyers fired torpedo after torpedo at the convoy, sinking three transports – Sumanoura Maru, Tatsukami Maru and Kuretake Maru – and a

torpedo boat. A Dutch submarine sank the Tsuruga Maru; and, as mentioned, Dutch aircraft had sunk the Nana Maru and probably also the Jukka Maru. It was the heaviest loss suffered by a Japanese convoy during their whole offensive.

–:–

At Kendari the American seaplane tender Childs was getting under way in the early morning of the 24th January when to the astonishment of her crew they saw a flotilla of enemy vessels approaching. The Childs made off, concealed in a sudden rain storm. The Japanese ships contained the Sasebo Combined Naval Landing Force – the equivalent of a brigade group of marines, and the same force as had taken Menado on 11th January. The resistance of the troops ashore was soon overcome.