Chapter 20: The Destination of I Australian Corps

In the period between the fall of Ambon and the fall of Singapore the Japanese had been steadily advancing their western flank. When the army cooped up in Singapore had been overcome, only flimsy Allied land and air forces remained to defend the rich western islands of the Indies.

The naval forces in General Wavell’s command still included eight cruisers, eleven destroyers and a Dutch and an American submarine flotilla. In his air forces, however, there were only some ten depleted Dutch squadrons, and the remnants of the air force from Malaya, which on 14th February consisted of 22 Hurricanes and 35 Blenheims, many of them unserviceable. This force, commanded by Group Captain McCauley,1 was operating from P.2 airfield near Palembang in Sumatra; Air Vice-Marshal Maltby was then reorganising his headquarters in Java. The Dutch-controlled army in Java consisted of about 25,000 men organised in four regiments, each of three battalions, and a very little artillery. There were also in Java five regiments of British anti-aircraft artillery, which had been sent there to defend the airfields, but had lost much of their equipment as a result of enemy action and other factors.

For several years the little army of the Netherlands Indies had been in process of expansion. The conquest of Holland by the Germans in 1940 made the continuance of this expansion, never an easy task for so small a nation, exceedingly difficult. The Indies Army depended chiefly on the homeland for its officers, for cadres of European soldiers, and for equipment. In 1940 and 1941 the proportion of Europeans to Indonesians in the army was reduced until it was about one in forty; additional weapons were obtained from America and Australia but there were not enough. In any event they were of different calibre from the Dutch weapons, and at length the Indies forces had rifles of 6.5-mm (Dutch), 7.62-mm (American), 7.7-mm (Australian) and 8-mm. Reorganisation was still in progress in December 1941, and in the words of a Dutch general staff officer “things were more or less chaotic”.

Destined for the Indies, however, was the I Australian Corps, a more formidable formation than the Japanese had yet encountered, but most of it was still far away. An advanced party of the Corps had arrived at Batavia by air on the 26th January. It included the commander, General Lavarack; his Brigadier, General Staff, Brigadier Berryman;2 his senior

administrative officer, Brigadier Bridgeford;3 Chief Engineer, Brigadier Steele;4 and six other officers. Eight more officers, including Brigadier C. E. M. Lloyd, arrived on the 28th January. From that day Lloyd, as has been mentioned, became Intendant-General on Wavell’s staff.

On the 27th January Lavarack met Wavell, who told him of his general plans: to hold Burma, south Sumatra, Java, Timor and Darwin, with an advanced position in Malaya. Wavell said that Lavarack’s role would be to hold south Sumatra with one division and central Java with another, Dutch troops being deployed in between in western Java. Lavarack, obedient to his standing instructions from his Government, objected to the division of the Corps, but Wavell insisted that it was necessary, and at length the proposal was submitted to and approved by the Australian Government. From 1st to 9th February Lavarack and Berryman reconnoitred south Sumatra and central Java and prepared appreciations of the situation the Corps faced in both areas.5

The day these tasks were completed Lavarack received a cablegram from the Australian Prime Minister, Mr Curtin, seeking his views on a policy of launching a counter-offensive as soon as reinforcing troops and aircraft arrived. Lavarack replied to this somewhat vague proposal that he agreed with the fundamental policy, but urged the need for reinforcements, perhaps from Australia.

Lavarack’s senior Intelligence officer, Lieut-Colonel Wills,6 had prepared on 2nd February a paper in which he predicted that the next Japanese objectives would be (a) Timor (thus to cut air communications between Java and Australia) and (b) the Sumatra airfields and refineries; and that the enemy could attain these objectives by 2nd March. Java would then be isolated, Wills continued, and the small Dutch garrison, “split up into penny packets throughout the island” and of problematical fighting value, would not hold out for long. On the information available, the leading Australian division could not be ready for action in the Indies before 15th March at the earliest.7 Wills concluded that adequate Australian troops

could not arrive in time; that if part of the Corps arrived before the Japanese attacked it would be lost; and that

by attempting to bring 6 Aust Div, 7 Aust Div and Corps troops to southern Sumatra and Java, under the circumstances and bearing in mind the time factor, the defence and safety of Australia itself is being jeopardised.

Early on the 13th, when it seemed that Singapore would soon fall, Lavarack prepared an appreciation to send to the Australian Chief of the General Staff, General Sturdee, for the information of the Prime Minister. It contained echoes of Wills’ paper, but took into account further information about the projected arrival of the I Australian Corps. Lavarack said that the fall of Singapore would release large Japanese forces; that one Australian division plus the few Netherlands East Indies troops in Sumatra would delay the enemy for only a short period, and he was “unable to judge whether such delay would justify the probable loss of 7 Aust Div equipment and possibly the loss of a large proportion of its personnel”. He considered that, even with the addition of the 6th Australian Division, the prolonged land defence of Java was impossible. The I Australian Corps was now the only striking force within reasonable distance of the Far East, and he stressed the value of its two highly-trained, equipped and experienced divisions. The main body of the 7th Division would begin to arrive on the 25th February and would probably not be ready for full-scale operations until the third week of March; the 6th Division would probably not be ready for full-scale operations in central Java until “the middle of April at the earliest.”8

Lavarack showed this message to Wavell, who expressed agreement but asked him to delay sending it until Wavell himself had sent a somewhat similar appreciation to the Combined Chiefs of Staff and the War Office. Wavell did this, adding to his appreciation the suggestion that there would be strategic advantages in diverting one or both the Australian divisions either to Burma or Australia. “This message,” he added, “gives warning of serious change in situation which may shortly arise necessitating complete reorientation of plans.”

While Wavell’s appreciation and Lavarack’s were on their way, General Sturdee was writing a comprehensive paper on the future employment of the AIF. He pointed out that the first flight of 17,800 troops of the Australian force was then in Bombay being re-stowed into smaller ships for transport to the Netherlands Indies. So far, he said, the Allies had violated the principle of concentration of force. The object should now

be to hold some continental area from which an offensive could be launched when American aid could be fully developed. Thus the sea and if possible the air routes from America should be kept open. The area to be held must be large enough to provide room for manoeuvre. The Dutch forces in Java “should be regarded more as well-equipped Home Guards than an Army capable of undertaking active operations in the field”. It seemed doubtful whether the 7th Australian Division could reach south Sumatra in time, and if they were unable to do so probably the whole Corps would be concentrated in central Java. Assuming the Australian Corps could reach Java in time, the defence of Java would depend on the Australian Corps of two divisions, one British armoured brigade (Sturdee did not know that Wavell had already ordered it to Burma) and two inadequately organised and immobile Dutch divisions (in fact an overstatement of the Dutch strength) . He considered the prospects of holding Java “far from encouraging”. If Timor were lost it would be impossible to ferry fighter and medium bomber aircraft to Java from Australia.

Sturdee concluded that the only suitable strategic base was Australia, with its indigenous white population, considerable fighting forces, and sufficient industrial development. The alternatives were Burma and India. Burma was already in the front line; India had a long sea route from America, and the attitude of its people was likely to be uncertain if the East Indies fell into Japanese hands.

The Australian Military Forces, he added, were being built up to some 300,000 but lacked much essential fighting equipment and were inadequately trained. He recommended that the Government should give immediate consideration to

(a) The diversion to Australia of:

(i) that portion of the AIF now at Bombay and en route to Java;

(ii) the British armoured brigade in the same convoy.

(b) The diversion of the remaining two flights to Australia.

(c) The recall of the 9th Australian Division and the remaining AIF in the Middle East at an early date.

After this had been written but before it had been delivered, Lavarack’s cable and then Wavell’s arrived, confirming, in Sturdee’s opinion, the views he had expressed.9

There was likely to be opposition to the policy recommended by Sturdee and Lavarack. Indeed, in Wavell’s cablegram there was an indication of one form which the opposition might take: a proposal to send one Australian division, or both, to Burma.

Sturdee and Lavarack had the advantage, when preparing these and later appreciations, that they were reproducing proposals and arguments which they had been expressing during the last decade, whereas the British and American Ministers and their advisers were viewing calamities which they

had not foreseen and which were occurring in areas about which they knew little. The Australian leaders belonged to a school of thought which had long contended that the situation of February 1942 would come about: Singapore fallen; the British and American fleets temporarily impotent against Japan; and Australia, the only effective base, being required to hold out until British or American reinforcements could arrive in strength.

Acting on the advice of Sturdee and influenced by Lavarack’s message, Mr Curtin, also on 15th February, sent a cable to Mr Churchill, repeated to the Prime Minister of New Zealand and General Wavell, to the effect that Australia was now the main base and its security must be maintained; “penny-packet” distribution of forces should be avoided; the Indies could not be held; the AIF should return to Australia to defend it.

When we are ready for the counter-offensive (he added) sea power and the accumulation of American forces in this country will enable the AIF again to join in clearing the enemy from the adjacent territories he has occupied.

It was not until the 17th, however, that Curtin sent a cable to Churchill repeating the precise requests suggested in Sturdee’s paper: that the three Australian divisions and, if possible, the 7th British Armoured Brigade be sent to Australia.

On the 16th Wavell had sent a cable to Churchill which to some extent reinforced Curtin’s. He said that he considered the risk of landing the Australian Corps on Java unjustifiable, and summed up:–

Burma and Australia are absolutely vital for war against Japan. Loss of Java, though severe blow from every point of view, would not be fatal. Efforts should not therefore be made to reinforce Java which might compromise defence of Burma or Australia.

Immediate problem is destination of Australian Corps. If there seemed good chance of establishing Corps in island and fighting Japanese on favourable terms I should unhesitatingly recommend risk should be taken as I did in matter of aid to Greece year ago. I thought then that we had good fighting chance of checking German invasion and in spite results still consider risk was justifiable. In present instance I must recommend that I consider risk unjustifiable from tactical and strategical point of view. I fully recognize political considerations involved.

If Australian Corps is diverted I recommend that at least one division should go Burma and both if they can be administratively received and maintained. Presence of this force in Burma threatening invasion of Thailand and Indo-China must have very great effect on Japanese strategy and heartening effect on China and India. It is only theatre in which offensive operations against Japan possible in near future. It should be possible for American troops to provide reinforcement of Australia if required.10

Meanwhile, on the 17th, Lavarack had cabled that the Orcades with 3,400 troops, mostly Australian, had been ordered to Batavia, that he had represented to Wavell that they should not be disembarked, but that Wavell did not agree, being “anxious to avoid appearance precipitately

changed plan which might compromise relations Dutch and prestige generally; also wishes them to protect aerodromes in Java”. Lavarack added that he considered there was no possibility of employing the AIF to advantage in Java. Sturdee, when handing on this cable, commented that if the troops landed and were distributed in Java it would be difficult if not impossible to withdraw them.

The Australian War Cabinet considered Lavarack’s Orcades cable on the 18th and decided to tell Wavell that Lavarack considered the Australian troops now at Batavia could not be employed to advantage in the Indies.

Next day – the 19th – when the Australian Advisory War Council considered the problem, it had before it also a cable sent from London on the 18th by the Australian representative to the United Kingdom War Cabinet, Sir Earle Page. He reported that the Pacific War Council (Churchill and the United Kingdom Chiefs of Staff plus representatives of Holland, Australia and New Zealand) had considered, on the 17th, the recommendation sent by Wavell on the 16th (and repeated to Australia by Page) that at least one Australian division should be sent to Burma. The Pacific War Council had thereupon recommended to the Combined Chiefs of Staff at Washington that resistance should be maintained by all forces already in Java, but no attempt should be made to land the Australian Corps in the Indies. It had also recommended that the Australian Government be asked to agree that the 7th Division “already on the water” should go to Burma, these being, in Page’s words, “the only troops that can reach Rangoon in time to make certain that the Burma Road will be kept open and thereby China kept in the fight. The position of this convoy makes it imperative that permission should be given to this course within 24 hours.” The Council had added that the 70th British Division, less one brigade, would be sent from the Middle East to Rangoon, and the remaining brigade used to garrison Ceylon; the remaining Australian divisions (6th and 9th) should go “as fast as possible back into the Australian area”.11

Also on the 18th Page sent to Australia a copy of a telegram to the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington recording the deliberations of this meeting of the Pacific War Council. In it the proposal about the 7th Division was phrased thus:

In view of the imminent threat to Rangoon and the vital importance of keeping open the supply route to China, the Australian Government should be asked to permit the 7th Australian Division, the leading elements of which are now off Colombo and are the nearest fighting troops to Rangoon, to proceed to Burma and assist in the defence of that country until they can be relieved.

The 7th Division was not in a single convoy ready to set out at short notice for Rangoon. It had embarked at Suez in five flights, three of them each containing a brigade group and a proportion of other troops; one

(in Orcades) containing principally two battalions; and one containing divisional headquarters and administrative units, and the cavalry and signals units. On the 17th February, when the Pacific War Council made its recommendation, the Orcades had reached Batavia, the second convoy (21st Brigade Group) was between Bombay and Colombo, the third (25th Brigade Group) was due at Colombo on the 18th, the fourth (18th Brigade Group) was two days’ sail west of Bombay, where it was to trans-ship into smaller transports (a task that would take five days), and the fifth, three days’ sail west of Colombo.

In addition, the transports had been hurriedly assembled from far and wide, and the staffs in Egypt, wisely as it seemed at the time, had loaded each group of ships as they became available, putting men on troop transports and heavy equipment on cargo ships, and had sent them off. Consequently the men were not necessarily in the same convoy as their heavy equipment. In January it had seemed that there would be time in Sumatra and Java to sort things out. To have insisted on each part of the force being “tactically loaded” would have delayed the movement of the Corps as a whole. Because he knew this Lavarack had pointed out on the 13th that the 7th Division could not be ready for operations in Sumatra until about 21st March. It was unlikely therefore that it could be ready for action in Burma even as early as that.

At the Australian Advisory Council meeting which considered these proposals the non-Government members recommended that the 7th Division

should go to Burma, but the War Cabinet decided to reject this advice and not to vary its request for the return of all three Australian divisions to Australia.

–:–

Thus the Pacific War Council in London was convinced, it seemed, that the 7th Division could save Rangoon, keep the Burma Road open, and thus keep China in the war.12 The non-Government members of the Advisory War Council considered that the 7th Division should go to Burma. The Australian War Cabinet, however, accepted the advice of General Sturdee that the whole AIF should return to Australia. It was natural that in this crisis the thoughts of British Ministers and generals (including those of Wavell, until recently Commander-in-Chief in India) should turn towards Rangoon and Calcutta. As has been shown, however, it was entirely consistent of General Sturdee to advise concentration on the defence of Australia at that stage, and the development of Australia as a base for a later offensive. Inevitably Curtin’s refusal to yield to the proposals formulated in London was opposed not only by Churchill but Roosevelt, for the stand the Australian leader had taken touched American policy on the raw.

The American leaders and people in general felt a strong affection for the Chinese. From the President downwards they regarded European imperialism in general and British imperialism in particular as an active force for evil in the world, and their own American colonial policy as an active force for good. Partly as an outcome of their sentimental regard for China they saw in the Chinese a potential military power which might greatly help them against the Japanese. To the British leaders Burma was a gateway to India; to the American leaders it was a gateway to China. Australian senior soldiers, on the other hand, were sharply aware of the internal insecurity of the Asian colonies, compared with Australia with its united and patriotic people, and of the Asian colonies’ lack of industrial equipment and skilled operators, in both of which Australia was relatively rich.

Sturdee’s paper was dated the 15th February; Curtin’s cable to Churchill requesting the return of all three divisions was sent on the 17th (the day on which, as it happened, Sumatra was evacuated). In the following six days there developed a cabled controversy of a volume and intensity unprecedented in Australian experience. On the one hand were the Australian Ministers and their Chief of the General Staff; on the other were Mr Churchill, President Roosevelt, their Chiefs of Staff, General Wavell, Mr Bruce (the Australian High Commissioner in London), and Sir Earle Page. The messages sent between the 19th and the 22nd which passed through Page’s hands alone cover twenty foolscap pages, many of them closely typewritten. They include discussion of problems other than the destination of I Australian Corps, but most of them deal chiefly with that subject.

On the 18th Wavell recommended through the War Office that the whole Australian Corps be diverted to Burma, or, if Burma were unable to receive it all, that part be landed at Calcutta. This cable was repeated to Australia. The same day Bruce cabled to Curtin declaring that it was “essential” to agree to the 7th Division going to Burma, and giving such reasons as keeping the Burma Road open, Chinese morale, strengthening Australia’s position in demanding help, and the feelings of the Dutch.

On the 19th (the day Darwin was bombed) Lavarack cabled to Curtin that the 7th Division should be sent to Burma “if Australia’s defence position reasonably satisfactory”. Sturdee still advised that the home defence position was not satisfactory; and Curtin sent a cablegram to Page confirming his previous decision. That day the Dominions Office sent a cable to the Australian Government stating that General Marshall had said that an American division would leave for Australia in March and asking whether, in consequence, the destination of the 6th and 9th Australian Divisions might not be left open; “more troops might be badly needed in Burma”. The same day Page sent a cablegram to Curtin asking him to change his mind and quoting arguments by Churchill.

On the 20th (the day on which, as described in the following chapter, Timor was invaded) Curtin sent a long telegram to Page and repeated it to Casey (the Australian Minister to Washington), Lavarack and Wavell, justifying the Australian decision and confirming it. That day Page informed Curtin that the original destination of the AIF “convoy” (not “convoys”) had not hitherto been altered during the negotiations, but that instructions had now been issued to divert it to Australia.

Still on the 20th Churchill cabled Roosevelt that “the only troops who can reach Rangoon in time to stop the enemy and enable other reinforcements to arrive are the leading Australian division”, but the Australian Government had “refused point blank” to let it go. He appealed to Roosevelt to send him a message to pass on to Curtin. Roosevelt did so, emphasising that he was speeding troops and planes to Australia and concluding “Harry [Harry L. Hopkins] is seeing Casey at once”. That evening Churchill sent to Curtin a telegram in which appeal, reproach, warning, and exhortation were mingled.13

On the 21st February Curtin was informed through Casey (Hopkins having seen him) that the American Government had decided to send the 41st United States Division to Australia; it would sail early in March. On the 22nd, Curtin having replied to Churchill’s telegram of the 20th with equal asperity, Churchill sent Curtin the following cable:–

We could not contemplate that you would refuse our request, and that of the President of the United States, for the diversion of the leading Australian division to save the situation in Burma. We knew that if our ships proceeded on their course

to Australia while we were waiting for your formal approval they would either arrive too late at Rangoon or even be without enough fuel to go there at all. We therefore decided that the convoy should be temporarily diverted to the northward. The convoy is now too far north for some of the ships in it to reach Australia without refuelling. These physical considerations give a few days for the situation to develop, and for you to review the position should you wish to do so. Otherwise the leading Australian division will be returned to Australia as quickly as possible in accordance with your wishes.

This information astonished not only Curtin in Australia but Page in London. Page promptly followed it up with a telegram to Curtin pointing out that it conflicted with the information he had received and also with a statement in Churchill’s cable of the 20th that the leading ship of the convoy would soon be steaming in the opposite direction from Rangoon.

Page learnt next day that the leading convoy had pursued its course towards Java up to 9 p.m. on the 20th, when the Admiralty, on Churchill’s orders, had directed that it should turn north towards Rangoon. The final appeal was sent to Curtin ten minutes later in the belief that a reply would arrive in time for the convoy’s route to be changed again without complications, if necessary. In the event, the reply from Australia was not received until the morning of the 22nd, by which time the Admiralty had learnt that some ships had not enough fuel to reach Australia.14

On the 23rd Curtin sent a cable to Churchill complaining that Churchill had treated his Government’s approval of the diversion of the convoy towards Rangoon as merely a matter of form, and that by doing so he had added to the dangers of the convoy. He added:–

Wavell’s message considered by Pacific War Council on Saturday reveals that Java faces imminent invasion. Australia’s outer defences are now quickly vanishing and our vulnerability is completely exposed.

With AIF troops we sought to save Malaya and Singapore, falling back on Netherlands East Indies. All these northern defences are gone or going. Now you contemplate using the AIF to save Burma. All this has been done, as in Greece, without adequate air support.

We feel a primary obligation to save Australia not only for itself, but to preserve it as a base for the development of the war against Japan. In the circumstances it is quite impossible to reverse a decision which we made with the utmost care, and which we have affirmed and reaffirmed.

Our Chief of the General Staff advises that although your telegram of February 20 refers to the leading division only, the fact is that owing to the loading of the flights it is impossible at the present time to separate the two divisions, and the destination of all the flights will be governed by that of the first flight. This fact reinforces us in our decision.

That day Churchill, not a little disgruntled, as his later telegrams show, informed Curtin that the convoy had been turned about, would refuel at Colombo, and proceed to Australia.

Meanwhile Sumatra had been lost and ABDA Command dissolved. Even before the end of January it had seemed likely that the first blows

against the western islands of the Indies would be felt by Sumatra. Japanese bombers operating from captured fields in Malaya had bombed the Palembang airfield (P.1) in south-eastern Sumatra from early February onwards. During the first fortnight of that month, however, they had not found the second and more distant Palembang airfield (P.2), 40 miles to the south-west of P.1, where, as previously mentioned, Group Captain McCauley’s depleted squadrons were then established.

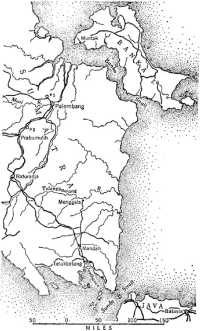

Except round the oilfields in the south and the refineries near Palembang, the island of Sumatra (in common with most of the Indies outside Java itself) was little developed in 1942. Only one through road – on the western side – ran from north to south. The southern tip of the island, however, was better served with roads than the rest, and a railway ran from Palembang to the port of Oosthaven, facing the Sunda Strait separating Sumatra from Java. In mid-February Palembang and the airfields were garrisoned by a number of Dutch platoon or company groups, plus some British anti-aircraft detachments, and some small groups of RAF men armed as infantry.

The Japanese land assault on the Palembang area was made by two main Japanese forces: the 229th Regiment (of the 38th Division) which sailed from Hong Kong to Camranh Bay and thence, on the 9th and 11th February, towards southern Sumatra; and a force of some 360 paratroops flown from airfields in Malaya. About 260 paratroops were dropped round P.1 airfield on 14th February, and next day about 100 were dropped near the refineries. There was close fighting against the paratroops throughout the 14th.

Meanwhile, on Wavell’s orders, given on the 13th, Admiral Doorman had sailed westward to intercept the Japanese convoy. Doorman himself was then south of Bali, and it was the 14th before he had collected his

forces. At dusk that day he sailed from a point north of Sunda Strait with the Dutch cruisers De Ruyter, Java, and Tromp, the British Exeter, the Australian Hobart, and ten destroyers. About midday on the 15th aircraft from the Japanese carrier Ryujo and land-based aircraft from Borneo attacked the Allied squadron. No Allied ships were hit but Doorman decided to withdraw southward.

It was not until the night of the 15th–16th that the leading Japanese infantry, having moved up the river Musi in landing craft, reached Palembang and joined the paratroops. Already Wavell had ordered the withdrawal of the garrison to Java by way of Oosthaven, where a number of small ships were waiting.

On the 14th Brigadier Steele, the Chief Engineer of I Australian Corps, had been sent to Sumatra to examine the proposed demolitions of the P.1 airfield. He was on his way from the airfield to the refineries at 9.30 a.m. when the Japanese paratroops landed. At Dutch headquarters he learnt that a few N.E.I. companies were on their way to reinforce Palembang; and he was joined by Lieut-Colonel MacCallum,15 a medical officer on Lavarack’s staff who was also reconnoitring in Sumatra. That afternoon, after having helped to organise the troops in the area, Steele, who was the senior Australian officer on Sumatra, went to Oosthaven to see what was being done about the reception of the Orcades, which was due to land her Australian troops there next day. The Orcades, a fast liner which had steamed far ahead of the other ships containing the 7th Division, carried 3,400 men, including two battalions – the 2/3rd Machine Gun (Lieut-Colonel Blackburn16) and the 2/2nd Pioneers (Lieut-Colonel Williams17) .

On the 11th February Lavarack had prepared an instruction for Blackburn placing him, on arrival at Oosthaven, in command of all Australian troops in Sumatra until the arrival of the divisional commander or a brigade commander. At length he was to move his force into the Palembang area, but at the same time guard his communications to Oosthaven. Steele, who had seen this order, held a conference of the senior Australian and British officers at Oosthaven on the morning of the 15th. It was discovered that there were no Dutch troops south of Prabumulih near the P.2 airfield. Steele then formed a headquarters to control the defence of Oosthaven with himself in command, and as “G.S.O. 1” Lieut-Colonel MacCallum (who although now a medical officer had been a brigade major in France in the war of 1914-18). The forces in the area comprised a light tank squadron of the 3rd Hussars (which had been disembarked on the 14th), a British light anti-aircraft battery, and five improvised companies of men of the RAF each of about 100 riflemen. Steele gave

the force the task of defending the Oosthaven area and covering the evacuation of the air force troops from P.2 and of unarmed men and civilians from Oosthaven.

At midday the Orcades arrived off the harbour. Steele went aboard and arranged for Blackburn to bring his men ashore, form them into a brigade and advance on P.2 and thence Palembang. The troops were disembarking when the captain of the destroyer Encounter which was in the harbour received a signal from Wavell’s headquarters ordering that no troops be disembarked and that the 3rd Hussars be put aboard the Orcades, which was to sail immediately. In the course of the day MacCallum was informed by a Dutch liaison officer that Japanese seaborne troops had landed at Palembang and had taken it, but that the oil refineries had been demolished except for two small plants.

On the morning of the 16th, after a conference of his own and Dutch officers, Steele, who had not yet learnt of Wavell’s order for the evacuation of Sumatra, issued orders for the withdrawal from Sumatra of all British troops by 11 p.m. on the 17th, in cooperation with the N.E.I. forces. Late on the 16th ABDA Command received a message from Steele asking for naval and air support during the embarkation of 6,000 men by 6 p.m. on the 18th. It had also received a comprehensive report about events on Sumatra when a liaison officer returned with an account of what Steele was doing. The same day P.2 was evacuated.

Reports now reached Steele that Japanese vessels, laden with troops, had moved upstream to Menggala. A rearguard of British anti-aircraft gunners and RAF riflemen under Major Webster18 of the Corps staff had been placed in position at Mandah, where the road and railway from the north crossed a river. Steele now advanced the time for evacuating Oosthaven to 2 a.m. on the 17th. The embarkation of troops was carried out accordingly, all equipment that could be lifted having been taken on board the ships. On the 15th, 16th and 17th about 2,500 RAF men, 1,890 British troops, 700 Dutch troops and about 1,000 civilians were embarked in twelve vessels. Lieut-Colonel Stevens19 of the staff of ABDA Command, who had organised the embarkation, went aboard the steamer Rosenbaum with the rearguard at 7.30 a.m. on the 17th. There remained at the quay a K.P.M. steamer to pick up any late arrivals, and two more small ships were in the roads. A small group of officers remained ashore.

After the main evacuation an urgent appeal was sent out by ABDA Command on the 17th to embark all aircraft spares and technical stores. This signal was picked up by the Australian corvette Burnie, covering the embarkation, and she reported that the vessels had sailed. She intended to demolish oil tanks and quays. Burnie was promptly instructed not to destroy anything in Oosthaven without the concurrence of the local military authority. Nevertheless the proposed demolitions took place. On the 18th, ABDA Command learnt that late-arriving troops were still being

embarked at Oosthaven in one remaining vessel. The enemy did not press on to Oosthaven, and on the 20th the Australian corvette Ballarat, whose captain knew Oosthaven well, went in with an air force salvage party of some 50 men and recovered valuable equipment.

–:–

No sooner had Sumatra been overcome than a Japanese force descended upon Bali at the opposite end of Java. When he learnt of the Japanese convoy advancing on Bali Admiral Doorman was at Tjilatjap with the cruisers De Ruyter and Java and four destroyers; the small cruiser Tromp was at Surabaya; and four American destroyers were in the Sunda Straits. Doorman decided to attack the enemy convoy on the night of the 19th–20th. The ships from Tjilatjap were to move in from the south at 11 p.m., and the Tromp and the four American destroyers would arrive from the north-west three hours later. One of the Dutch destroyers, the Kortenaer, ran aground leaving Tjilatjap. When Doorman’s squadron reached Bali about 10 p.m. on the night of the 19th–20th one Japanese transport, escorted by two destroyers, remained. In a confused action the Dutch destroyer Piet Hein was sunk and the Japanese transport damaged; the Allied squadron withdrew. About three hours later the Tromp and the four American destroyers came in. In the succeeding action hits were scored by both sides but no serious damage was done.

When he received news of the action the Japanese admiral, who was north of Bali with the cruiser Nagara and three destroyers, sent two destroyers to help the other ships. These encountered the Tromp’s force in Lombok Strait, east of Bali, at 2.20 a.m. and there both Tromp and a Japanese destroyer were severely damaged. Thus, although the Japanese were out-gunned at all times, they inflicted heavier loss than they received.

By the 20th, the airfields of Timor, Bali and Sumatra having been lost, the Allied air force in Java was now virtually cut off from reinforcement by air. That day the Combined Chiefs of Staff informed General Wavell that all land forces hitherto approaching him from the west were being diverted elsewhere, but that the troops on Java must fight on. Wavell was told also that Burma would be transferred to the control of the Commander-in-Chief, India – a course which Wavell had always advocated – and he was instructed on the 21st to transfer his headquarters “at such time and to such place within or without the ABDA area as he might decide”. In reply Wavell recommended that his headquarters be not transferred but dissolved since he now had practically nothing to command, and the control of the forces in Java could be better exercised by the Dutch commanders.

Also on the 20th Mr Curtin informed General Lavarack of the Australian Government’s opposition to the diversion to Burma and that the Government had been influenced in this policy by Lavarack’s advice. Curtin asked Lavarack to explain the unsatisfactory situation of Australia’s home defences to Wavell and ask for his sympathetic cooperation. He asked whether, if the worst came to the worst, there would be some

chance of withdrawing the men from Orcades, which had arrived at Batavia on the 17th and disembarked its troops there on the 19th.

Curtin and his advisers apparently did not realise that Lavarack had been in the Middle East since 1940 and could not speak with authority on the present situation of Australia’s home defences. That day Lavarack saw Wavell, however, and discussed with him the plans for the 7th Division and the troops in Orcades. After the meeting Lavarack wrote in his diary that General Wavell was

sympathetic but feels cannot give way on subject of 7 Div. Also did not do so on subject of landed troops for reasons air requirements ... and moral effect, particularly on Dutch. Promised, however, to make arrangements for evacuation if necessary and possible, and said had spoken to Admiral Palliser re this. Saw Palliser and found no positive arrangement, but promised to do all possible.

It was now decided to use Orcades to take away the advanced parties of the Australian Corps and the 7th Division. Consequently, on the 21st, Lavarack cabled to Curtin informing him that these advanced parties were embarking in Orcades for Colombo pending a decision as to their destination, and that he himself was flying to Australia to report. The Australian troops who had been landed in Java were being retained for defence of airfields, but arrangements were in train for their embarkation when the final decision was taken about Java.

Lavarack still did not know whether or not the Corps might go to Burma and, before he set out by air for Australia, instructed Allen that if the Corps went into action during his absence Allen was to command it, with Brigadier Bridgeford as his senior general staff officer, while Berryman commanded the 7th Division. Before the embarkation of the advanced parties Berryman issued an instruction to Blackburn, now promoted to brigadier, placing the following AIF units under his administrative command:–

| Approximate strength | |

| 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion | 710 |

| 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion | 937 |

| 2/6th Field Company | 222 |

| Company headquarters and one platoon of Guard Battalion | 43 |

| 105th General Transport Company | 206 |

| 2/3rd Reserve Motor Transport Company | 471 |

| 2/2nd Casualty Clearing Station | 93 |

| Stragglers | 165 |

| Details | 73 |

For operations “Blackforce”, as it became known, would be directly under the command of the Dutch Commander-in-Chief, General ter Poorten.

General Wavell and his staff were still in Java, and a message from Wavell to the War Office indicated that they would remain there until ordered to go. On the 21st the Dominions Office cabled to Curtin that the Chiefs of Staff in London had suggested to the Combined Chiefs in Washington that ABDA Command headquarters should move to Fremantle

pending further instructions. That day Wavell cabled to Washington describing the situation in Java and seeking instructions. Fewer than 40 fighter aircraft and 40 bombers remained, he said, and little could be done to prevent a Japanese invasion. He was endeavouring to evacuate about 6,000 surplus RAF and RAAF men and 1,400 American air force men. There would remain 3,000 to 4,000 RAF men, 5,500 British troops, 3,000 Australians, 700 Americans, and 650 officers and men of his own headquarters.

The Combined Chiefs on the 22nd sent Wavell a telegram stating that:–

All men of fighting units for whom there are arms must continue to fight without thought of evacuation, but air forces which can more usefully operate in battle from bases outside Java and all air personnel for whom there are no aircraft and such troops particularly technicians as cannot contribute to defence of Java should be withdrawn. With respect to personnel who cannot contribute to defence, general policy should be to withdraw U.S. and Australian personnel to Australia.

On the 23rd the Combined Chiefs accepted Wavell’s proposals and Wavell decided to dissolve his command from 9 a.m. on the 25th.20 It had been in existence just six weeks.

On the 21st February Wavell had sent to Churchill (who had suggested that he should again become Commander-in-Chief, India) a characteristic signal which concluded:–

Last about myself. I am, as ever, entirely willing to do my best where you think best to send me. I have failed you and President here, where a better man might perhaps have succeeded. ... If you fancy I can best serve by returning to India I will of course do so, but you should first consult Viceroy both whether my prestige and influence, which count for much in East, will survive this failure, and also as to hardship to Hartley [the Commander-in-Chief, India] and his successor in Northern Command.

I hate the idea of leaving these stout-hearted Dutchmen, and will remain here and fight it out with them as long as possible if you consider this would help at all.

Good wishes. I am afraid you are having very difficult period, but I know your courage will shine through it.21

Here this great commander, perhaps the noblest whom the war discovered in the British armies, passes out of the Australian story. It was under his command-in-chief that Australians, including some who had until recently been round him in Java, had taken part in the first successful British campaign, and later in other operations in the Middle East, some of which succeeded and some of which failed. The failures of the second quarter of 1941 had led to his removal to India, a removal which he accepted in written and spoken word as he accepted every decision of his seniors as being right and proper. The Japanese onslaught brought him a second time to the command of the main theatre of war. There he deported himself with immense energy for a man whose first taste of active

service had been gained 42 years before; with a fastidious regard for the proprieties, and with characteristic wisdom and self-effacement.

General Lavarack first learnt that the 7th Division was destined not for Burma but Australia when he arrived at Laverton airfield near Melbourne on the evening of 23rd February. He asked General Sturdee, who met him there, when he should be leaving again.

Sturdee then astonished me with the information that the whole set-up was now changed (he wrote in his diary) and that the whole of I Aust Corps was now ordered to Australia, by arrangement though not agreement between the British and Australian Governments.

Mr Curtin now set about trying to extricate the 3,000 Australian troops from Java. On the 24th he cabled to Page and Casey that his Government insisted that Wavell be given authority to ensure that the Australian troops in Java be evacuated ultimately to Australia. Page, however, could only reply that, although Wavell had been given authority to evacuate certain personnel, the Pacific War Council had recommended to the Combined Chiefs at Washington six days before that resistance should be maintained in Java by the troops already available there. Curtin, probably impressed by the undesirable moral effects of withdrawing troops already deployed on the soil of an ally, did not persist, and the 3,000 Australians remained in Java.

In London Sir Earle Page was disappointed about the decision not to send Australians to Rangoon, and he now adopted the suggestion of Colonel Wardell,22 the Australian Army liaison officer at Australia House, that the 7th Division should reinforce, at least temporarily, the garrison of Ceylon. (Retention of Ceylon was essential to continued control of the Indian Ocean.) Page discovered that the garrison of Ceylon consisted of the 34th Indian Division (two Indian infantry brigades and one Ceylon brigade with only one battery of field artillery). There were 116 antiaircraft guns. One brigade group of the 70th British Division would arrive in mid-March.23

On the 24th Page sent this information to Curtin with a recommendation that the 7th Australian Division should be landed in Ceylon at least until the brigade of the 70th Division arrived.

Thereupon Curtin cabled to Page (on the 26th) complaining that Page was not advocating the Australian point of view; on the contrary he had subscribed to the diversion of the 7th Division to Burma and was now seeking its diversion to Ceylon. Curtin said that a further reply would be sent about Ceylon, and meanwhile he instructed Page to “press most

strenuously” the importance of Australia’s security as a base for a counter-offensive against Japan. In a cable containing more than 2,000 words, Page defended his policy and insisted that the security of Australia had always been his first consideration; but he doggedly continued to press for an answer to his proposal about Ceylon and on 2nd March Curtin sent Churchill a cablegram in which he said:–

1. We are most anxious to assist you in your anxieties over the strengthening of the garrison at Ceylon.

2. The President while fully appreciating our difficult home defence position in relation to the proposed return of the AIF was good enough to suggest that he would be glad if we would see our way clear to make available some reinforcements from later detachments of the three divisions of the AIF which have all been allocated from the Middle East to Australia.

3. For the purpose of temporarily adding to the garrison of Ceylon, we make available to you two brigade groups of the 6th Division. These are comprised in the 3rd Flight of the AIF and are embarking from Suez. We ask that adequate air support will be available in Ceylon and that if you divert the two brigade groups they will be escorted to Australia as soon as possible after their relief. We are also relying on the understanding that the 9th Division will return to Australia under proper escort as soon as possible.

4. As you know we are gravely concerned at the weakness of our defences, but we realise the significance of Ceylon in this problem and make this offer believing that in the plans you are at present making you realise the importance of the return of the AIF in defending both Australia and New Zealand.24

Two questions need to be answered: Was the I Australian Corps necessary to the defence of Australia; and could the available Australian troops have saved Rangoon and kept the Burma Road open in 1942?

It is not part of the task of the writer of this volume to answer the first question in detail. It is enough to say here that the next volume of this series will show that within a few months of its arrival in Australia the Corps and the divisions it included were needed to halt the Japanese advance in New Guinea.

To examine the question whether the available Australians could have saved Rangoon (as Mr Churchill and his Chiefs of Staff believed at the time and as Mr Churchill evidently still believed in 1951 when he published the fourth volume of The Second World War) it is necessary to turn back to the second week of February, just after a visit by General Wavell to the Burma front. Indian and British troops were then holding a front west of the Salween River. Wavell wrote later that:

all commanders expressed themselves to me as confident of their ability to deal with the Japanese advance.25

It was then that Wavell decided to divert the 7th Armoured Brigade, intended for Java, to Burma, and it arrived on 21st February.

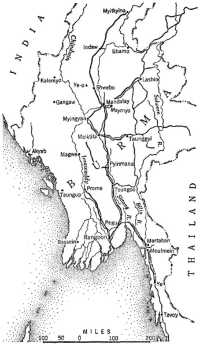

The force defending southern Burma was the 17th Indian Division, which included the 16th and 46th Indian and 2nd Burma Brigades. Farther north, in the southern Shan States, was the 1st Burma Division, including one Indian and two Burma brigades, but for the present the Japanese invading force – mainly the 33rd and 55th Divisions, each less one regiment – was concentrated against southern Burma. The conclusion had been reached that “the battalions of Burma Rifles, which formed so large a proportion of the army in Burma, were undependable”.26

From 22nd February control of operations in Burma was taken away from ABDA Command and returned to the Commander-in-Chief in India. About the same time General Alexander,27 then commanding Southern Command in England, was appointed to the army in Burma; but he would not be able to arrive there until the first week of March. On 25th February, as mentioned, Wavell closed his ABDA Command headquarters and was appointed Commander-in-Chief in India again; on the 27th he reached Delhi.

Meanwhile the front west of the Salween River had been crumbling. On 11th February Martaban was lost. On the 14th the 17th Division (Major-General Smyth28) began to withdraw to the Bilin River. By 17th February the whole division was heavily engaged, and that night the Japanese crossed the Bilin. Counter-attacks failed to restore the position and, on the 19th, General Hutton decided to withdraw behind the

Sittang River. On this line the enemy would be close to the main road and railway to Mandalay and thence the road to China; and incidentally the road and railway to Mandalay was one of two main land routes for evacuation from Rangoon.

On the 18th February, General Hutton had cabled ABDA Command and the War Office that in the event of a fresh enemy offensive in the near future he could not be certain of holding the position on the Bilin River. If this line were lost the enemy might penetrate the line of the Sittang River without much difficulty and the evacuation of Rangoon would become an imminent possibility. The best he could hope for was that the line of the Sittang River could be held, possibly with bridgeheads on the eastern bank. A withdrawal to that river would, however, seriously interfere with the use of the railway to the north and thus with the passage of supplies to China. To hold the line of the river permanently and to undertake the offensive, he would want the extra division which had already been promised him from India but was not scheduled to arrive until April. Meanwhile he could only hope that the V Chinese Army would fill the gap. To defend Rangoon against a seaborne attack on the scale which had now become possible, he would require a second additional division, and to provide for a reserve and for internal security a third division was desirable. He required therefore, over and above the two divisions which he already had, an additional three. His major problem, however, was whether the prospects of holding Rangoon and denying the oilfields justified the efforts to provide these reinforcements, which could only be at the expense of India. He himself thought that, provided reinforcements could be sent earlier than at that time visualised the effort would be justified but, failing an acceleration of the reinforcement program, the risk of losing Rangoon was considerable.

This was two days before Mr Churchill cabled to Mr Curtin that the leading Australian division was “the only force that can reach Rangoon in time to prevent its loss and the severance of communication to China”, and added “it can begin to disembark at Rangoon about the 26th or 27th”. On the 20th the 17th Indian Division began to withdraw to the positions west of the Sittang. The Japanese followed up fast. In two days of heavy fighting – in the course of which, at 5.30 a.m. on the 23rd, the bridge over the river was blown while two brigades and part of a third were on the far side – the division lost practically all its heavy equipment. Its infantry strength was reduced to 80 officers and 3,404 other ranks, of whom only 1,420 still had their rifles. The effective units east of Rangoon were now only the 7th Armoured Brigade (two armoured regiments and one British infantry battalion) which had just disembarked, and a second British battalion watching the coast south of Pegu. Farther north was the Burma Division, which had only three Indian battalions and two battalions of the Burma Rifles, some of whose men had deserted.

On 21st February the Chiefs of Staff in London, having reviewed the position described in telegrams from General Hutton, had asked General

Wavell whether he still wished the 7th Australian Division to be diverted to Burma. Next day Wavell cabled both to the Chiefs of Staff and Hutton that he saw no reason why air attack should close Rangoon port, and that the only prospect of success lay in a counter-offensive, for which the 7th Armoured Brigade and an Australian division would be needed. On 23rd February Hutton agreed to accept the 7th Australian Division provided it arrived in time, but added that a final decision whether “the convoy” should enter the port would have to be made 24 hours before its arrival.

If the 21st Australian Brigade had continued its voyage to Rangoon it could have begun disembarking about the 26th, three days after the disaster on the Sittang. The convoy containing the second brigade of the division was then still at Colombo, having sailed there direct from Aden and arrived on the 18th; the third brigade was at Bombay about seven days’ voyage from Rangoon; the commander and part of the headquarters of the division and part of the headquarters of the corps were in the Orcades steaming west from Java and due at Ceylon on the 27th. None of these convoys was “tactically loaded”. Lavarack had estimated that the division could not be ready for operations in Java (where some preliminary organisation had been done by the advanced parties) before 21st March, and it seems improbable that the division could have been reasonably equipped and ready for action in Burma sooner than that.

On the 24th and 25th February the Japanese again attacked Rangoon from the air in full force, but again, as had happened in late December, the defending fighters shot down so many of the attackers that the raids were not repeated after the 25th. Already, however, there was chaos in the city.

Rangoon burned. Once more a multitude of refugees poured down the roads from the city, crammed the outgoing trains, and fled into the jungle. ... The “E” evacuation warning signal was hoisted on February 20th, 1942, and an exodus gave the capital of Burma over to fire and the looters. The Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, remained with his senior officials, preparing a demolition of the port and powerhouse. At this midnight of disaster, troopships and transports of the 7th Armoured Brigade drew alongside the quays, and the 7th Hussars, 2nd Royal Tank Regiment and a battalion of the Carneronians began disembarking their Stuart tanks and carriers. They rendered incalculable service during the rest of the campaign. Indeed, these 150 tanks probably saved the army, for they convoyed or carried thousands of troops out of encirclement, broke the Japanese road-blocks, held at bay the Japanese armour, and acted as the artillery of the rearguard all the way northward to the frontier of India.

The last days of Rangoon were at hand. Singapore had fallen, releasing Japanese troops and air forces from Malaya. But it was the loss of sea power which decided the issue. With Singapore there passed also the command of the Indian Ocean; Rangoon became indefensible, and without Rangoon the British Army in South Burma could not be supplied at that period since there were no land links with India.29

When Wavell reached Delhi on the 27th (the day after the 21st Australian Brigade might have begun to disembark) he learnt that it was proposed in Burma to evacuate Rangoon. He immediately cabled that

nothing of the sort should be done until he arrived, and he ordered that convoys carrying a fresh Indian brigade – the 63rd – to Burma, which had been turned back from Rangoon, should sail into that port. He himself arrived by air at Magwe, on the Irrawaddy, on the 1st March and there confirmed his order that Rangoon be not abandoned. That day he flew on to Rangoon, and thence up to the front, where he replaced the commander of the 17th Division “who was obviously a sick man”.30 Next day Wavell flew to Lashio and interviewed Chiang Kai-shek, and on the 3rd flew back to India. At Calcutta he met General Alexander, who had just arrived by air, and instructed him to hold Rangoon as long as possible.31 Alexander alighted at Magwe airfield on the 4th March and reached Rangoon on the 5th. The 63rd Indian Brigade, newly disembarked, was about 16 miles north of Rangoon, but its vehicles were still on board the transports. There was a gap of 40 miles between the 17th and the Burma Division (each with an effective strength of about a brigade) and Japanese were across the road between them. Alexander ordered attacks north and south so that the two divisions could link, and these gained some success, but meanwhile the Japanese cut the Rangoon-Pegu road, south of Pegu, and by 6th March one regiment of the armoured brigade and a brigade of the 17th Division were isolated in Pegu. At midnight of the 6th–7th Alexander ordered that plans for demolition in Rangoon be put into operation, the city evacuated, and the forces regrouped north of Rangoon in the Irrawaddy Valley. In the next few days the force in Pegu succeeded in extricating itself and it and the other forces round Rangoon were withdrawn to the Irrawaddy Valley ready to retreat northward. The Japanese entered Rangoon before dawn on the 8th March.

In the conditions outlined above it would have been astonishing if the 7th Australian Division – landed at Rangoon a brigade at a time between about the 26th February and the 6th March, with the transport and heavy weapons arriving on different vessels from those carrying the men, with no previous reconnaissance or base organisation, no tropical equipment and no tropical experience – could have been landed, organised, and launched into a successful counter-offensive against two hitherto victorious Japanese divisions in time to save Rangoon.32 It is even more doubtful whether, had the 7th Division done this, the success could have been maintained in the face of increasing Japanese air power and Japanese naval control of the eastern part of the Bay of Bengal and beyond. A force defending Rangoon could have been adequately supplied only by sea,

and the Japanese had the means of cutting the sea route to Rangoon, as they were soon to demonstrate.

It is now evident that the 7th Division would have arrived in time only to help in the extrication from Pegu and to take part in the long retreat to India. In that event it could not have been returned to Australia, rested, and been sent to New Guinea in time to perform the crucial role it was to carry out in the defeat of the Japanese offensive which would open there in July. The Allied cause, therefore, was well served by the sound judgment and solid persistence of General Sturdee, who maintained his advice against that of the Chiefs of Staff in London and Washington; and by the tenacity of Mr Curtin and his Ministers, who withstood the well-meaning pressure of Mr Churchill and President Roosevelt.