Chapter 21: Resistance in Timor

Like Ambon and Sumatra, the island of Timor was a stepping-stone towards Java, heart of the Dutch empire in the East Indies. The Australian garrison sent to Timor in December 1941 to reinforce the local force was likely to be attacked once Ambon had fallen.

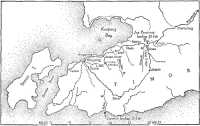

The area of Dutch Timor, comprising the south-western portion of Timor, was 5,500 square miles. Koepang, the capital and principal port, 517 miles from Darwin and 670 from Java, looked out on Koepang Bay. The principal airfield of Dutch Timor, at Penfui, was six miles south-east of the town. Four near-by seaplane anchorages, the principal one at Tenau, five miles south-west of Koepang, formed one seaplane base. Koepang Bay and the adjacent Semau Strait provided good shelter for shipping. There was in Dutch Timor a population of at least 400,000 Timorese and 4,000 to 5,000 other people, including Dutch, Chinese, and Arabs.

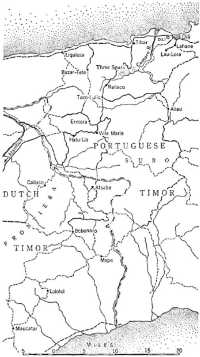

The eastern part of the island, and a small enclave at Ocussi on the north-west coast, were under Portuguese control. This colony had an area of 7,700 square miles and a population of about 300 Portuguese, 500,000 Timorese, 2,000 Chinese and a few Japanese and Arabs. Early in 1941 the interest shown by Japan in the establishment of an air service with Portuguese Timor had aroused the suspicion of the Dutch and Australian authorities. The Australian Cabinet had decided in October that, because of the threat to Australia that would arise from a Japanese occupation of Portuguese Timor, she must be prepared to cooperate to the fullest possible extent in measures for the defence of the Portuguese as well as the Dutch part of the island. To imagine that the Japanese would respect it as the territory of a neutral power, or that its small force was capable of defending it, would have been to take an extravagantly optimistic view.

Dili, situated on the north coast of the island, 450 miles from Darwin, had an airfield a mile west of the town, and ship and seaplane anchorages. It stood amid a flat, swampy area bounded by a semicircle of hills, at its greatest distance some three miles behind the shore. The hills merge into a series of mountainous corrugations extending over by far the greater part of the colony. Dili contained the residence of the Governor,1 and the principal European community. The colony was divided into provinces each with its administrator, and each province into “postos” under a junior official.

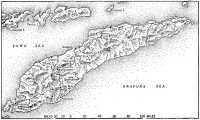

The island of Timor as a whole is 290 miles long, and up to 62 miles wide. Mountains, highly dissected and extremely rugged, occupy most of the island, and rise to 9,000 feet. The north-eastern portion of Timor particularly is dominated by them – in fact it was feelingly described by an Australian officer as “one lunatic, contorted, tangled mass of mountains”,

in which “the mountains run in all directions, and fold upon one another in crazy fashion”. Much of the south-west is open country, which in 1941 could be easily traversed afoot or on ponies. Timorese ponies – small sturdy animals of which it was estimated that there were at least 100,000 – were the basic form of transport on the island generally. A main trunk road ran from Tenau to Atapupu on the north coast, thence into Portuguese Timor, where it more or less followed the coast. Offshoots ran inland, and there were innumerable tracks, mostly suitable for horses. Only three roads crossed the island from north to south; two of these were at the Dutch end. Ships and seaplanes could use many points round the coast other than those mentioned, and there were many potential airfields. An existing airfield at Atambua, 180 miles from Koepang, was swampy and of little value.

A force of about 500 troops was under command of Lieut-Colonel Detiger, the Dutch Territorial Commander of Timor and Dependencies in December 1941, and there was a similar force under Portuguese command. The number at Dili (about 150) was considered insufficient to turn even a small-scale Japanese attack.

This was the situation when, on 12th December, the 2/40th Australian Battalion, detached like the 2/21st from the 23rd Brigade at Darwin, arrived, with the 2/2nd Australian Independent Company,2 at Koepang. The commander of the force, Lieut-Colonel Leggatt, aged 47, was a Melbourne lawyer who had served as an infantry subaltern in France in the previous war, and in the militia between the wars. He had been appointed to command the 2/40th, replacing Lieut-Colonel Youl, just a month before

the war with Japan broke out. A battery of coast artillery was included in the force, which contained approximately 70 officers and 1,330 men and was transported in the ships Westralia and Zealandia. The only air force on the island was No. 2 Australian Squadron (under strength) flying Hudson bombers. The main task of the small Allied force was to defend the Bay of Koepang and the airfield. Positions south of Koepang were to be held by the Dutch, and those to the north by the Australians, who were also made mainly responsible for the defence of the Penfui airfield. When the agreement was made to reinforce Timor with Australian troops and aircraft, the possibility of the island being subjected to large-scale attack seems not to have been envisaged. It was seen rather as part of an outpost line whence aircraft might operate northward.

Known as “Sparrow Force”,3 the Australian contingent was at first administered by Colonel Leggatt from a force headquarters, but on the ground that the arrangement led to unnecessary duplication this headquarters was soon disbanded and the force was controlled from battalion headquarters at Penfui. A rear headquarters was established at Tarus and a base at Champlong. Fixed defences were concentrated at Klapalima, a battery position on the coast three miles and a half north-east of Koepang. It was found after disembarkation that many valuable stores, including wireless sets, had been lost, or damaged in handling at Darwin, and by local labour at the landing. Sanitary preparations for the force

had not been completed, and most of the Australians were attacked by dysentery and malaria. These circumstances, and the need to labour on beach and airfield defences and other work, severely hampered training. Reporting on the force soon after its arrival, Leggatt mentioned that only a token defence of the island could be provided, owing particularly to its 400 miles of coastline and the degree of dispersion necessary even in the area near Koepang. He twice asked for an officer to be sent to Timor to carry out an inspection, but none came.

Preceded by about 100 additional troops from Java, Colonel van Straaten arrived at Koepang by air on 15th December to command the Dutch forces on the island. He was to be under Leggatt’s command. A conference held that evening was attended by the Dutch Resident at Koepang (Mr Niebouer); the Australian Consul at Dili, Mr Ross;4 van Straaten; Leggatt; Detiger; the Commander of the old 16-knot Dutch training cruiser Soerabaja (5,644 tons); the Officer Commanding the Australian air force squadron, Wing Commander Headlam;5 the Commander of 2/2nd Independent Company, Major Spence;6 and staff officers. Van Straaten said he had been informed by the Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies, Jonkheer Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer, that as a result of negotiations between the United Kingdom, Dutch, Australian and Portuguese Governments it had been agreed that in case of aggression against Portuguese Timor by Japan, the Governor of Portuguese Timor would ask for help, and Australian and Netherlands East Indies troops would be sent there; further, that if the Government of the Netherlands Indies considered the matter urgent, and an attack on Dili was imminent, the Portuguese Governor would be informed and would ask for these troops to be sent. The colonel added that he was instructed by the Governor-General to say that Japanese ships were now in the vicinity of Portuguese Timor, and it was urgent that troops be sent to Dili. It was agreed that Leggatt and Detiger leave for Dili next day by the Canopus,7 and convey this information to the Governor at 8 a.m. on 17th December. Ross flew back to Dili to arrange the interview.

Netherlands Indies troops numbering 260, and 155 of the Independent Company embarked on the Soerabaja at 8 a.m. on 16th December, leaving the remainder of the Independent Company to follow aboard the Canopus on its return to Koepang. Wearing civilian clothes, Leggatt and Detiger were introduced by Ross to the Governor on the 17th, and Leggatt conveyed to him the message he had received through van Straaten. The Governor said that his instructions were definitely to ask for help only

after Portuguese Timor was attacked. He was told that this would be too late; the troops were on their way, and must land. He then asked that the matter be put in writing, and when this had been done, asked for half an hour to discuss the matter with his Ministers. At 9.45 a.m. he said a message had been received from Lisbon, and he wanted an hour to decode it. This was agreed to, but meanwhile the Soerabaja had arrived off Dili, escorted by Australian aircraft. At 10.50 a.m. the Governor announced that the message was to the effect that he definitely must not allow troops to land unless Portuguese Timor was attacked, and that therefore his forces must resist such a landing.

Obviously the Governor was seeking to follow a diplomatically “correct” procedure which would avoid prejudice to Portugal’s neutrality. The delegation, however, expressed the hope that there would be no fighting, pointing out that the Portuguese force was too small to succeed. The Governor said that when the landing occurred he would see the commander of his troops, and “ascertain what arrangements could be made”.8 Leggatt and Detiger then boarded the Soerabaja, and reported the interview to van Straaten.

That afternoon the troops landed. Spence told his men that they might have to fight as soon as they stepped ashore; but they and fifty Dutch troops landed unopposed, on a sandy beach about two miles and a quarter west of Dili, in the early afternoon. A small party of signallers went into the town under Lieutenant Rose,9 to take over the radio station and signal Sparrow Force at Koepang. They were agreeably surprised to find the inhabitants apparently friendly towards them, and to experience no difficulty in taking over the radio station.

The Dutch were to occupy the town, and the Australians the airfield about a mile and a half west of it on the coast. As a precaution, the Australians took up positions near their objective, while Spence advanced with his No. 1 Section to the airfield and met the Governor, the Dutch Consul at Dili, and Ross. Australian occupation was agreed to by the Governor, though apparently with reluctance. Spence was unable to discover the whereabouts of the Portuguese troops, or their strength. The Australians then moved in, and at dusk were digging in around the two runways, and the hangars.

The attitude of the Portuguese authorities continued to cause concern. Leggatt and Detiger returned to Koepang on 17th December, but Leggatt was back in Dili for a few hours on the 19th. He found that at van Straaten’s request the Governor had sent most of the Portuguese force out of Dili, but that the Portuguese Council was meeting that day to discuss the situation brought about by the landing. Subsequent indications were interpreted as meaning that the Governor was definitely against the occupation, was obstructing by all means in his power, and probably would assist any Japanese attack. Leggatt reported to Australian headquarters that the pro-British Portuguese in Dili could form a government,

with the support of the Allied force, and that Ross recommended that that support be given if the Governor persisted in his attitude. On 31st December a message was received by Sparrow Force to be passed to Ross that, owing to a severe Portuguese reaction and threats to break off diplomatic relations, British proposals had been submitted to Portugal with Australia’s approval. These were that the Dutch force withdraw to Dutch Timor and be replaced by more Australians from Koepang. The message added that this might relieve the situation, as the Portuguese were highly antagonistic to the Dutch, and had presented a note amounting to an ultimatum.10 Sparrow Force replied to the message from Australia that the arrangement whereby forces had to be maintained at Koepang and Dili meant that they were weak at both points. If the proposals were carried into effect Koepang would be further weakened.

By 22nd December the remainder of the Independent Company, comprising a third platoon (Captain Laidlaw11) with signallers and engineers had reached Dili, and the company had received its only transport vehicles – two one-ton utilities and three motor-cycles. The Australians quickly set about obtaining a thorough knowledge of the country in which they might have to fight.12 They formed friendships with the people of Dili so quickly that a picquet with transport had to be sent to the town to bring men back to their lines after the hospitality they enjoyed on Christmas Day.

Platoons were on the move to various tactical positions when the men were attacked by malaria, with the result that early in January the company had practically no fighting strength. Captain Dunkley,13 the medical officer, established a hospital at Dili and within a few days it was crowded with seventy severe cases. Shortage of transport seriously hampered the moves, especially as so many of the men were ill, and it limited the extent of dispersal of men, supplies and equipment. By early February company headquarters and the hospital were at Railaco, in the hills behind Dili on the road to the town of Ermera.

Two sections of Captain Baldwin’s14 platoon were dispersed nearby over a series of heavily wooded spurs. A detached section (Lieutenant McKenzie15) was stationed at the airfield, and Laidlaw’s platoon was in the Bazar-Tete area, where it was in a position to control the coast road running west from Dili, and had an observation post overlooking the airfield. Fifty-five reinforcements who arrived on 22nd January had gone

into training with Captain Boyland’s16 platoon at a position known as “Three Spurs” between Railaco and Dili. The Dutch force was stationed in the town. Its officers showed little of the activity of the Australians in acquainting themselves with their surroundings, and disapproved of their friendly, easy-going attitude towards the other races on the island.

Back in Koepang Leggatt kept touch with Dili and forged ahead with defensive preparations. In its first operation order, on 25th December, Sparrow Force was told “Japan is moving southward. ... Landings may be expected around Koepang Bay and on the west coast in Semau Strait, and at any point or points on the south coast, by a force up to the strength of a division.” The order added that there was no naval support, nor could reliance be placed upon it becoming available. Of the 371 Dutch troops under command of Sparrow Force in Dutch Timor, 188 were in the Koepang area. Captain Johnston’s17 (A) and Roff’s18 (B) companies of the 2/40th were assigned to beach defence between Koepang and Usapa-Besar, six miles north-east of the capital; Captain Burr’s19 (C) to Penfui; and Captain Trevena’s20 (D) was to be kept on wheels as a mobile reserve. One platoon (Sergeant Miller21) of Headquarters Company (Major Chisholm22) would act as a covering force to the fixed defences at Kapalima, and a “reinforcement company” (Lieutenant Tippett23) would provide protection for headquarters. Combined Defence Headquarters were at the RAAF control room at Penfui; advanced headquarters also at Penfui; and base at Champlong, 29 miles from Koepang, in foothills overlooking the bay, and on the road through the centre of Dutch Timor to the north coast and Portuguese Timor. The responsibility of the Dutch troops in the Koepang area was to defend the stretch of beach from Koepang to Tenau.

Christmas Day was the occasion also of a message from Army Headquarters about Japanese tactics in Malaya, thus giving warning of what to expect should Timor be attacked. It was an interesting epitome of what had been learned to that date, setting out that the Japanese were full of low cunning, and used noise to lower morale and cause premature withdrawal; that it was customary for them to send a screen of troops, often dressed in ordinary shorts, shirts, and running shoes, to locate positions; and that, when this had been done, strong forces, often a battalion, deployed to the rear and worked round the flanks of their enemy. All

this was done very rapidly, continued the message, and every endeavour was made to maintain the momentum of attack. The Japanese were prepared to live on the country to a greater extent than British troops, and were therefore less dependent upon lines of communication. Theirs was essentially a war of movement and attack, and experience had proved that the best way to defeat them was by counter-attack. (“Cannot defeat enemy by sitting in prepared positions and letting enemy walk round us,” ran the message. “Must play him at his own game, and attack him every possible occasion.”24)

Leggatt was perturbed by the circumstances in which his force was placed in Dutch Timor. In a letter to Brigadier Lind on 4th January he wrote:–

We are looking after 4½ miles of beach and there is still about 6 miles of beach on our right flank which we should cover, but all I can do is to put a mobile reserve well out on that flank to deal with anything that tries to come through there. The Dutch have about 7 miles of beach to cover from the eastern end of the town to Tenau and about 180 men at present with which to do it. The camp is situated alongside the aerodrome along a road ending abruptly and most decidedly about three miles further south. No movement is possible off the roads now or for the next three months, and even in the dry season no movement is possible by MT or even by carriers across country for any distance because of the rough coral country. ... No ship has called here yet from Australia and we have no news about our carriers and extra MT, our leave personnel or our reinforcements – all of course badly needed and awaited eagerly. There is still a great deal to be done regarding naval and air force cooperation. We get on quite well with the RAAF here but they are just as much in the dark about things as we are. Ships and planes come and go with very little, if any, warning.

Lieut-Colonel Roach, returning to Australia from command of Gull Force on Ambon Island, called at Koepang on 17th January. He and Leggatt fully agreed that the forces for the defence of both Ambon and Timor were inadequate.

The steamer Koolama and the sloop Swan arrived on the 19th January bringing about 100 reinforcements (with little training) and some men returning from leave. On the 23rd the first batch of what was intended to be a steady stream of American aircraft assembled in Australia for use in Java landed en route at Penfui.

Seven Japanese aircraft arrived overhead on the 26th, machine-gunned the camp and airfield, damaged two aircraft on the ground, and shot down an unarmed machine. On the 30th (the day of the first Japanese landings on Ambon Island) Penfui was again raided, this time by forty-two aircraft. They destroyed a Hudson on the ground, attacked a dispersal airfield on the Mina River, destroying another Hudson, and shot down a Qantas flying-boat over the sea. These, and succeeding raids directed principally against shipping at and near Koepang, sharpened expectations of an invasion of Timor in the near future.

General Wavell, in Java, had decided on 27th January that Timor was threatened. Its airfield was essential, since short-range aircraft could not reach Java from Australia without refuelling after the flight over the Timor Sea.

I somewhat reluctantly departed from the principle I had laid down that we could not afford to reinforce these small garrisons (he wrote later) and asked the Australian Government for permission to move a battalion from Port Darwin to Koepang, while the Americans agreed to send an artillery regiment from Port Darwin. I sent a battery of light AA artillery from Java.25

The Australian War Cabinet at first would not agree to this request on the ground that Australia had only two trained battalions at Darwin, but on 5th February, on the advice of the Chiefs of Staff, decided that the 2/4th Pioneer Battalion should go to Timor. Ships would not be available until 15th February.

Meanwhile on 9th February the Japanese had come nearer. That day a force which had embarked at Kendari, now an effective enemy air base, landed at Macassar.

In anticipation of the Australian Government’s decision, Brigadier Veale,26 hitherto Chief Engineer of the 7th Military District, had been instructed to take command of Sparrow Force with its additional battalion. Captain Arnold,27 Veale’s staff captain, and a small advanced party reached Timor on 9th February. Veale, with his brigade major, Cape,28 arrived on the 12th.

The 49th American Artillery Battalion which was allotted to Sparrow Force was one of two which had been landed at Darwin on 5th January from the transport Holbrook. The Holbrook had been part of the “Pensacola Convoy” carrying reinforcements to the Philippines but diverted to Australia when the war broke out. The 79th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery (a British unit sent by Wavell), less one troop arrived at Koepang from Surabaya on the 16th.29 On the same day, Japanese bombers passed over Koepang and bombed the convoy, escorted by the American cruiser Houston, the American destroyer Peary and the Australian sloops Swan and Warrego, which was bringing the other units from Darwin. About the same time, Wavell, having decided that an attack on Timor was imminent, ordered that the convoy turn back, and it did so, arriving at Darwin on the 18th. No ships were hit.

The Australian airmen, and some American pilots whose craft had been wrecked in Dutch Timor, were flown out of Penfui on the 19th.

Sparrow Force was informed that Penfui would cease to be an operating station, and become a refuelling point only. Its use even for this purpose became questionable when news was received that the Den Pasar airfield at Bali, used as a further stage in flying fighter aircraft to Java, had been so heavily bombed as to be unserviceable, and was under frequent attack. Darwin was asked by Leggatt to state the future role of Sparrow Force in these circumstances, but no reply was received.

On the ground that a strong Portuguese garrison force was on its way to take over the defence of Portuguese Timor, plans to withdraw the Dutch troops from Dili were afoot early in February.30 Leggatt sought to withdraw the Independent Company also, partly because of its serious malarial casualties and partly so that it might replace Trevena’s company as a mobile reserve to safeguard the Koepang-Champlong line of communication, and enable the 2/40th Battalion to operate as a more compact unit. Veale thereupon decided to withdraw the company to Penfui and sent a message to Major Spence instructing him to move his troops overland to Atambua, where transport would be provided; but the message arrived too late to be acted upon. However, Captain Callinan,31 second-in-command of the company, left Railaco for Dili on 19th February to confer with van Straaten about movement of the Allied forces from Portuguese to Dutch Timor. That day news arrived of a devastating Japanese air raid on Darwin. The report stated that a Japanese aircraft carrier, a cruiser and five destroyers were 80 miles east of Kolbano, on the south coast of Dutch Timor.

The Portuguese force to replace the force at Dili was about due when, near midnight of 19th–20th February, Private Hasson,32 one of the sentries on the Dili airfield, reported noises which he thought might indicate that the Portuguese had arrived. Lieutenant McKenzie, at the section’s headquarters on the airfield, passed the report on to Callinan by ringing him at the Dutch headquarters at Dili. After advising him to send a patrol to investigate, Callinan switched him through to van Straaten, who ridiculed McKenzie’s suggestion that an enemy landing might be in progress. Next came a report from another sentry that he could hear foreign voices. Reluctantly, because the voices might have been of Dutch troops who, van Straaten had told him, were due to reinforce the Australians on the strip, McKenzie again lifted the receiver to ring Callinan.

The sound of shell fire reached Callinan at this moment. The first of eight rounds hit the Dutch headquarters, but left the Japanese consulate building next door unscathed. Callinan was unhurt, but he heard moans from Dutch troops farther down the corridor. Sections of the building

caved in from another hit as he left it. He found van Straaten still sceptical about a landing, and convinced that the shells were coming from a submarine; then Dutch artillery returned the fire, and McKenzie saw a warship and a transport. He again rang van Straaten. The Dutch commander persisted that the attack was coming from a submarine, adding that it might land a few troops who would attempt to blow the airstrip and withdraw; but McKenzie preferred to believe the evidence of his own eyes. He sent another patrol, and a Bren gun team to cover the entrance to the airfield from Dili. An attempt was made to signal with a Lucas lamp to a post above company headquarters, but it failed owing to fog. The patrol returned with a negative report. Had he been too hasty? Once again, McKenzie rang Callinan.

The conversation was interrupted by a burst of fire from the Bren team. They were in action against the enemy, mowing down the foremost of a party of Japanese soldiers who a moment before had been loudly laughing and chattering as they marched along the road. Private Ryan33 at the Bren first thought they were the expected Dutch reinforcements, and held fire until the Japanese were so close that those not put out of action by his first burst were able to throw grenades into the gunpit. These seriously wounded Ryan, and killed Private Smith.34 Now, however, the Japanese evidently thought they were being trapped, and withdrew. Corporal Delbridge35 and Private Doyle36 crawled into the pit and bandaged Ryan, who refused to budge from his gun and urged them to leave him alone. During a lull in a second Japanese attack, Delbridge and Doyle moved into undergrowth. Ryan attempted to fire as soon as the Japanese came within good range, but his gun jammed. One of the Japanese called in English “Surrender! You are no longer an enemy. Take off your coat and give it to us.”

“If you want my coat, come and take it off yourself,” was Ryan’s reply.

Another party of Japanese ran into heavy machine-gun fire at the back of the hangar at this stage. Trying to ring Dili again, McKenzie found that the line was dead. Doyle, the section runner, quickly claimed the task of taking a message to the Dutch headquarters, though he knew that in doing so, he would have to pass through the Japanese.

Then commenced a dangerous journey. Doyle mounted an old Dutch push bicycle ... called farewell to his friends, then crouching low over the handle-bars, pushed off for the strip entrance, where the Japanese troops were preparing to attack, speeding along as fast as his legs would take him.

Through the strip entrance he rode, Japanese troops on either side of him, fast through the darkness until he arrived on the main Dili road. The sight of a dashing

Australian riding a push bicycle hell for leather through their lines must have amazed the Japanese to such an extent that they did not open up. Whatever it was, not a shot was fired at him by the enemy.

He rode into the township, found Captain Callinan, and delivered the message. He told him that the Bren gun team had been knocked out, and how precarious the situation was at the strip; then not being satisfied with the one-way trip he mounted his bicycle again and with a reply message from Captain Callinan headed back for the section.

This time he was not so fortunate. He rode the cycle along the main road until he approached the strip entrance where the fighting was taking place, contacting a group of Japanese. Turning sharply he gathered speed, and crouching low over the handlebars, riding the old Dutch cycle like an Olympic games star, he headed back towards the town.

The Japanese opened fire with rifles and L.M.G’s, hitting the push-bike and forcing Doyle to leave his vehicle at top speed, to land on his feet, and crouching low disappear along the side of the road.37

Excepting what Doyle accomplished by his bravery, the now-familiar story of failure of communications in the face of the Japanese onslaught was repeated at this stage. Trying to transmit a message from Dili to company headquarters, Callinan found that the radio was disabled. When it had been repaired, no response could be obtained. The road between Dili and the headquarters was the one along which the Japanese had advanced from their landing point between Dili and the airfield. At the airfield, Corporal Curran38 was sent by McKenzie to check up at all the positions under his command. Curran found that the men were in good fettle, and well placed to carry out the role for which they had been trained, of a small force containing a large one. McKenzie himself occupied a fighting position, and with rifle and machine-gun fire the Australians made their enemies pay for each attempt to infiltrate their positions. Curran, who had been given responsibility for blowing the airstrip, bayoneted several Japanese on a bridge over a ditch on the western edge of the airfield; Privates Poynton39 and Thomas40 distinguished themselves as Tommy gunners.

As dawn approached, with the danger that it would reveal that the airfield was being held by only a section against overwhelming odds, McKenzie reviewed the situation. The reinforcements promised by van Straaten had not arrived, and McKenzie was unable to obtain orders from higher authority. The Japanese attack strengthened. He arranged for a dawn counter-attack to cover withdrawal. This attack, carried out with determination and vigour by Poynton and Thomas, and Private Hudson41 with a rifle, enabled the airstrip to be cratered by the sappers and the withdrawal to proceed. Ryan remained beside the body of Smith in the

gunpit, and with Signalman Gannon,42 who also had been wounded and refused to let others hold back to help him.

The section set off in independent groups. McKenzie and Private Hooper43 left the main party at a Dutch artillery position and went to Dili. There McKenzie found that Callinan had left with the Dutch forces, under the impression that they were retiring to a secondary position at Taco-Lulic to direct the battle from there. Callinan had taken with him Doyle, who had got back to Dili after his dash on a bicycle. An Australian signaller at the radio station was still trying to transmit a message to company headquarters. McKenzie sent Hooper to bring the main party into Dili, intending to lead them by an indirect route to Railaco.

Private Holly44 reached Tibar without encountering any Japanese, and met a platoon patrol which had come down from Three Spurs to investigate the cause of explosions they had heard when the strip was blown. Within four hours of having left the strip, he was at company headquarters with the patrol, breaking the news of what had happened to McKenzie’s section. Meanwhile Callinan, having accompanied the Dutch some distance before discovering that they intended leaving Portuguese Timor, had informed van Straaten that he must leave him and return to Australian headquarters. Van Straaten agreed, and Callinan and Doyle set off for Railaco in a direct line. On the way they almost walked into an ambush, only avoiding it by scrambling

up a hillside chased by shots from the Japanese, and hiding among some bushes. From this position they saw McKenzie’s main party and some Dutch troops approaching a junction of roads to Lahane and Lau-Lora in a van and an old truck they had acquired. The party, anticipating an ambush, took up positions to attack the Japanese. Lance-Corporal Fowler,45 Privates Poynton, Thomas, Growns,46 and Signalman Hancock,47 firing from a ditch beside the road, were highly successful. Poynton knocked out a Japanese machine-gun and its crew, then advanced with hand grenades and repeated the feat.

Callinan and Doyle meanwhile had pushed on towards Aileu. That night – the second of the assault on the Dili area – McKenzie and his main party, except for Fowler, Poynton, Thomas and Hancock, set off for Railaco, and on the 25th rejoined their platoon. The four continued their fire until dusk, then withdrew along the road towards Atambua taken by van Straaten and 150 Dutch troops, whom they overtook early next morning. Curran, with two sappers (Lance-Corporal Richards48 and Williamson49) had set out for Three Spurs to convey the news of the landing, rightly judging that as the night had been foggy the fighting would not have been seen from there. Williamson had a bad attack of malaria, and the three were without food for nearly three days. When after a hazardous trip they reached Three Spurs on 27th February they found that the camp was being prepared for demolition.

Company headquarters received from Captain Laidlaw in the Bazar-Tete area on the morning of 20th February an account of what was then happening at Dili. His platoon’s observation posts commanded a view of a warship shelling the town, and Japanese troops landing. Laidlaw sent a running description of the scene by radio to Railaco, and then led a patrol towards Tibar. This met the patrol from Three Spurs which had been encountered by Holly.

Lieutenant Campbell50 of No. 7 Section, patrolling at Tibar, had also seen the warship, and sent a runner to Three Spurs with the news. A party of fifteen accompanied by the Company Quartermaster Sergeant, Walker,51 had left for Dili on leave before the runner arrived. Unaware that the Japanese were in Tibar, they drove through the village and reached the Comoro River before they were halted and taken prisoner by Japanese sentries. All but four were then sent on in the truck towards Dili. The fate

of the four – Lance-Sergeant Chiswell52 and Privates Alford,53 Hayes54 and Marriott55 – illustrated how the Japanese military code of honour so often worked out in practice. They were forced to march for some distance; then their hands were tied behind their backs; and they were pushed into a drain beside the road. As they lay helplessly there the Japanese fired on them, killing three. Hayes lay unconscious with a bullet through his neck. When he regained consciousness and moved the Japanese bayoneted the four, wounding him again in the neck. Reviving, he found that his wristlet watch had gone, but that in the act of taking it his wrists had been freed. Despite his pain and weakness, Hayes crawled away into a rice-field, where he was found by native people. They took him to their village, where a woman tended his wounds. They then dressed him in their clothes, and took him on a pony to Laidlaw’s positions at Bazar-Tete.

With the departure of the Dutch,56 the Independent Company was left to fend for itself. As the situation became apparent to the Australians, they continued to move farther back into the hills. As the Three Spurs site was being vacated Percy the magpie, an Adelaide bird, which had been brought to Timor as a mascot, was last seen perched nonchalantly on a demolition charge.

By the end of February, company headquarters had been established at the Villa Maria, a house twenty miles from Dili, and a little inland of Ermera. Boyland’s platoon was farther inland, at Hatu-Lia. Laidlaw’s platoon continued to patrol the Bazar-Tete–Tibar area. There, on the last day of the month, they had their first encounter with the enemy. Seeing a convoy of Japanese trucks travelling along the coastal road between Dili and Liquissa, they went down to the road and attempted to mine it. However, the convoy came into view on its way back to Dili before this dangerous task – delayed while the section casually brewed itself some tea – had been completed. When the first truck passed them without hitting a mine, Lieutenant Nisbet,57 one of twelve lining the road, stepped from cover and aimed a machine-gun at the driver. The gun jammed, and the convoy dashed through rifle fire and bursting grenades. One of the trucks was wrecked, but the rest got away.

The incident showed the Japanese that the Australians were prepared to give fight without waiting for the enemy to seek them out; and on 2nd March Laidlaw learned that Japanese troops were on their way to Bazar-Tete to deal with this danger. From a near-by spur, Laidlaw and his men watched them enter the village and approach their position. Under Australian fire, the Japanese went to ground and commenced their characteristic encircling movement. Realising the threat, the Australians withdrew along a spur, with Japanese moving up spurs on either side of it. Privates Knight58 and Mitchell59 were killed, and three were wounded.60 It then appeared that one party of Japanese was moving west of Bazar-Tete, and the other between Bazar-Tete and Railaco. The withdrawal would have to be made between these two forces.

The firing had been heard by Baldwin’s platoon, now situated at Lonely Cross Spur, farther into the hills south-west of Railaco; and next morning 150 Japanese approached this position. Their forward party, of about fifty soldiers, marching gaily along, with rifles slung over their shoulders, entered an ambush of twenty-two men of McKenzie’s section and of platoon headquarters, directed by Lieutenant Baldwin. In a moment, a Japanese officer was shot, and Japanese were falling before they could unsling their rifles. The action continued until the main body of the Japanese brought up mortars. Having accomplished their purpose, Baldwin and his men withdrew without casualties, but leaving the ground littered with enemy bodies. The withdrawal was part of a plan agreed upon earlier whereby Baldwin’s platoon should withdraw to Mape, and Laidlaw’s to Hatu-Lia. It was made difficult by the fact that a second party of Japanese had outflanked Bald-win’s platoon, which remained under cover during the day, and at nightfall made for Boyland’s post at Hatu-Lia. After gruelling experiences, in steep, jungle-tangled country, they and Laidlaw’s platoon had all reached HatuLia by 7th March, and the company was together for the first time since it had landed on the island.

This meant a great deal. Under test, it had stood up to the tough, flexible sort of warfare for which the unit, but few others in the Allied forces, had been trained. Its losses had been slight. Though Portuguese reports were that 4,000 Japanese had landed, and 200 had been killed in the action at the airfield, the company had emerged from the first shock of assault a compact, alert fighting body, undaunted by the disappearance of the Dutch force from the scene of action, or by the Japanese numbers and tactics. Its members scorned messages from the Japanese urging them to surrender, though rumours were current that they would be treated as spies if captured.

There was, however, anxious speculation about the fate of Australia, for the message about the raid on Darwin was the last home news the company had received. And what had happened to the main body of Sparrow Force in Dutch Timor?

–:–

Brigadier Veale had completed the reconnaissance he undertook on arrival on Timor, when on 19th February the news of the Darwin raid reached him. He was in a difficult position. The units which were to have built up the Australian force to the strength of a small brigade group had not arrived; his own staff was incomplete. In these circumstances he wisely instructed Colonel Leggatt to put his (Leggatt’s) plan for the defence of the airfield into operation, to keep the airfield open as long as possible, and then to withdraw on Su, some 30 miles east of Champlong. Leggatt ordered his force to stand ready for action. During the evening a watching point at Semau Island, flanking Koepang Bay to the southeast, reported that thirteen unidentified warships and transports were approaching from the north-west. Rear headquarters were moved to Tarus, north-east of Usapa-Besar on the road leading to the north coast and Portuguese Timor. Veale also moved his headquarters to Tarus, intending to go next day to Championg where he could organise some form of defence in that area and at the same time give Leggatt the freedom of action a battalion commander might expect. A report was received during the night from the Independent Company that Dili was being shelled from the sea. Then silence fell on events in that area.

Early on 20th February a report arrived that the Japanese had begun to land at the mouth of the River Paha, which reached the south coast at a point almost due south of Usapa-Besar. Tracks led from the mouth to roads into Koepang, but owing to the smallness of the forces on the island the spot was undefended. (It was to meet such a contingency as this that one company had been organised as a mobile reserve.) The Japanese landing was a serious threat to the rear of the force at Koepang. Sparrow Force engineers were ordered to blow their prepared demolitions on the Penfui airfield as authorised by Veale; and the reserve company (Captain Trevena) was sent to positions based on Upura, astride the road to Koepang from the south coast, along which the Japanese might advance. The company was machine-gunned from aircraft while the move was being made. Veale, who meanwhile had moved from Tarus to Babau farther east, suggested to Leggatt that Sparrow Force move to Champlong; but as demolitions were incomplete, Leggatt decided against this. Veale and his headquarters troops themselves moved to Champlong, as arranged.

Veale’s plan was to give Leggatt what assistance he could from Champlong, where the limited reserve supplies were concentrated, and if the Independent Company arrived from Portuguese Timor, to use it as a reserve wherever required. His Signals Officer, Captain Parker,61 tried without success

to reach Australia by wireless from the 2/40th Battalion’s station at Champlong, and from a point several miles farther along the Su road. Soon, most unfortunately, Veale was also out of wireless communication with the 2/40th Battalion. Veale decided that Champlong could not be held long, whereas Su could be held for some time by a battalion group – and as mentioned Leggatt had been instructed to withdraw his force there when he could no longer hold the airfield. Consequently Veale decided to maintain a small defensive position astride the road west of Champlong, move all stores to Su, and then his headquarters. He arrived at Su on the 21st February.

The Japanese were acting swiftly meanwhile. Their bombers attacked the fort at Klapalima on the 20th, mortally wounding the commander, Major Wilson.62 The air force report centre, transferred from Penfui to Champlong, received at 9.30 a.m. that day a report that hundreds of Japanese paratroops were landing five miles north-east of Babau.63 The whole force was jeopardised by the landing of these paratroops astride the only road into the centre of the island, particularly as it cut the battalion off from its main ammunition dumps and supplies at Champlong. The only men in the Babau area were the cooks and “B” Echelon personnel, and the men of headquarters company, together with a few patients and medical orderlies in a small dressing station. Captain Trevena’s company was summoned back to Babau, and the men in the threatened areas were ordered to defend them meanwhile. Klapalima was again bombed, and both guns there, having become ineffective as a result of the destruction of their communications, were put out of action by their crews.

After the destruction of the guns Leggatt redeployed his force. Captain Roll’s company, which had been ordered to evacuate its position on the beach and move to a prepared position for defence of the fort, was ordered to the airfield. Captain Johnston’s company was ordered from its beach position to a prepared position in defence of the Usapa-Besar road junction. Lieutenant Sharman’s64 platoon was to send out a fighting patrol to Liliba to contact the enemy. The N.E.I. force was ordered to move its headquarters to Tarus (to join Sparrow Force rear headquarters) and to take up a position from Liliba to Upura astride the Baun road.

An advanced party of the paratroops entered Babau at 10.50 a.m., and met stiff resistance from two improvised platoons of Australians, armed only with rifles, plus artillerymen fighting as infantry. After suffering severe losses the Australians were forced out of the village early in the afternoon, and withdrew to Tarus.

When Trevena’s company became available it advanced on Babau. It attacked from a start-line about 500 yards west of Babau at 4.30 p.m. The left platoon, advancing through maize fields, forced its way into the eastern end of the village. The other platoons, under mortar and machine-gun fire, advanced to the market place, Lieutenant Corney65 being killed in an attack on a machine-gun post. A considerable number of paratroops were killed in the village and a useful number of automatic weapons captured, but enemy machine-guns firing from the concealment of the maize made the Australians’ position untenable. When it was almost dark, and there seemed to be hundreds of Japanese moving into the village, Trevena withdrew his men to Ubelo, a good defensive position.

The situation after the day’s fighting was reviewed at a headquarters conference at Penfui at 8 o’clock on the night of 20th February. The Japanese were astride the line of communication between Penfui and the supply base, with a force too large for Trevena’s company to overcome. Leggatt therefore decided to withdraw from the airfield. He intended to use his force to recapture Babau and Champlong (presumed to have been occupied by the enemy) obtain the supplies it needed, and then wage guerrilla warfare on the Japanese.

He ordered the force to concentrate at Tarus, and movement thither began at 10 p.m. Johnston’s company remained in position until all other troops had withdrawn past the Usapa-Besar junction, and then it withdrew across the Manikin River. Sappers of the 2/11th Field Company demolished the bridge.

At Tarus about midnight Leggatt gave instructions for a second attack on Babau at 5.30 a.m. on the 21st. All company commanders and Colonel Detiger, the Dutch commander, were present. Leggatt explained that his headquarters would be at a point 500 yards west of Ubelo. Roll’s and Trevena’s companies, each with a section of carriers, an armoured car, and a mortar detachment under command, would lead the attack from a start-line at Ubelo.

Trevena’s company began to advance at 5.30 but was halted for a time by a Japanese paratrooper in the maize at the left of the road. This man was disposed of, but the advance continued only slowly; there were no troop-carrying vehicles and the men were very tired, having had little rest for the three previous nights. At 8.30 a.m. it was reported that about 300 more paratroops had been landed in the same area as on the previous day. From 7 a.m. Japanese aircraft were over the Australian column strafing and dive-bombing. The gunners of the 79th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery – a veteran unit which had served in the Battle of Britain – shot down several aircraft and damaged others.66

Leggatt and his adjutant, Captain Maddern,67 joined the forward companies at 10.30 a.m. They were then about 800 yards from the outskirts of Babau. After a rest the advance was continued at midday, with Trevena’s company astride the road and Roff’s on its left. Soon after the advance was resumed the companies came under very heavy fire. Trevena ordered his two right-hand platoons to withdraw 200 yards preparatory to a wide flanking movement, but the platoons, still under heavy fire and losing men, moved back almost to Ubelo. Leggatt and Maddem came forward again at 2 p.m. and Leggatt ordered Trevena to prevent the enemy from moving towards Ubelo; but they could not find Roff, although they found one of his platoons almost in Babau, protecting a light antiaircraft gun of the British battery.

Leggatt thereupon returned to Ubelo and ordered Burr’s company forward from Tarus to reinforce Roff’s. At the same time he ordered that all vehicles should move to Ubelo within a perimeter to be formed by Johnston’s company and Trevena’s and men from the fixed defences. The antiaircraft battery too was moved into the perimeter.

Meanwhile Roff’s company (with two platoons of its own and the remaining platoon of Trevena’s company) had won a brilliant success. They had moved round the left flank, cleared the paratroops from the maize fields there and then taken Babau. In a building that seemed to be the enemy’s headquarters Roff (who was wounded but carried on) and two men had killed 10 paratroops, including their commander. Corporal Armstrong68 advanced under heavy fire with a Lewis gun, established himself in a building from which he could enfilade an enemy group, and drove it off, killing five. Lieutenant Williams69 led his platoon with great dash. Maps and equipment were captured. Only isolated Japanese remained in Babau when the Australians moved out.

Leggatt then decided to move the whole force into Babau that night. Johnston’s company entered unopposed at 8 p.m. and by 5.30 a.m. on 22nd February the force was concentrated there, with Roff’s company forward on the right, Johnston’s on its left, Burr’s on the left rear, Trevena’s on its right and the transport within the perimeter. The Dutch force did not take part in this movement.70

At Babau the savagery of the Japanese again revealed itself. It was found that several Australians, including a medical orderly, had been tied to trees, and their throats cut. One man, forced by the paratroops to carry a wireless set, had been bayoneted when he collapsed of exhaustion. He was still alive when his comrades found him, but died later. Some

men of the fixed defences who had been sent on their way to hospital at Champlong on the 20th had been intercepted, tied together, and shot.

At this stage it seemed likely that from 300 to 500 paratroops were between Leggatt’s force and Champlong, and that the enemy was in Koepang. Leggatt decided to move the whole force on to Champlong, beginning at 8 a.m. with Roff’s company, followed by Johnston’s and Trevena’s. Burr’s was to protect the rear. The carriers and mortars were allotted to the forward companies and the anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns were distributed along the column. At 7 a.m. Japanese paratroops surrounded an anti-aircraft gun that had moved outside the perimeter to join the convoy then forming up. The gunners held them off until one of Johnston’s platoons attacked and drove them away.

All rations and ammunition in Babau having been issued, the head of the column passed the start-line punctually at 8 o’clock. About a mile from Babau a road-block was seen at the bridge over the Amaabi River and many Japanese, with a mountain gun, were seen digging in on the Usau ridge over which the road passed. Roff decided to move round the left – the more covered approach – cross the river and attack the ridge.

Only the left platoon (Warrant-Officer Billett71), however, managed to cross the river, and it suffered a number of casualties in doing so. The others, under heavy fire, waited until support could be given by the mortars. They then

moved well round the left flank and finally attacked, but were driven out by superior numbers. ... Hundreds of the enemy appeared to be occupying the village [Usau], most of them being concentrated on the reverse slope of the ridge, and both front and flanks of the village were protected by an organised defence.72

Two more mortar detachments were sent forward to Roff and throughout the morning these fired on the ridge. At 10 a.m. Johnston’s company attacked on the right but could not continue because the approach was across 400 yards of open ground well covered by the enemy’s fire. A second attack at midday also failed. At 1.30 Leggatt and Maddern went forward to Johnston, and there Leggatt decided that an attack on that flank could not succeed. He therefore ordered the company back to the main road preparatory to a three-company attack. Leggatt then reconnoitred the left, and after his return summoned the company commanders to report at 4.30 p.m. for orders. These were that, after a mortar and small arms bombardment and after the engineers had removed the roadblock, the battalion would attack Usau ridge, with Johnston’s and Burr’s companies forward supported by the fire of Roff’s company, the medium machine-guns and mortars. The start-line would be the river left of the road. Roff’s company was to advance as soon as Johnston’s gained its first objective. At 4.35 p.m., 25 minutes before the attack was due to begin, heavy firing was heard from the rear of the column still near

Babau, and word soon arrived that an enemy column about 400 strong had approached moving along the road in fours. Trevena’s company, guarding the convoy, with 30 men of the fixed defences, went into action and soon dispersed the enemy, but this fight continued throughout the evening.

The fire support for the attack on Usau ridge was intense, and the ridge became obscured by dust and smoke. Lieutenant Stronach,73 Sergeant Couch,74 and five others of the engineers removed the road-block without anyone being hit, and at 5.25 the attack went in. Roff’s company on the right met fierce fire and soon he and his second-in-command, Lieutenant Gatenby,75 had been killed and a platoon commander and several NCOs wounded.76 Johnston’s company soon gained their first objective – a knoll on the left of the road at the entrance to the village. At this stage the enemy still occupied the ridge to the right, the troops on the right were pinned down, Johnston’s company was clearing the enemy from the village and the reverse slope, and Burr’s, having made a wide sweep on the left, was approaching the village at right angles to the road, having lost heavily during its advance. The ridge was strewn with Japanese dead.

Leggatt and Maddern moved forward to the knoll as soon as Johnston captured it. They brought a Japanese machine-gun on the knoll into action against the Japanese pinning down Roff’s company, but quickly ran out of ammunition. Leggatt then moved forward to control the forward companies, leaving Maddern to deal with the mopping-up of the Japanese who were holding up Roff.

Maddern ordered “R” Company to rush the ridge. This company consisted of reinforcements who had enlisted in December 1941, arrived in Timor on 16th January with little training, and were now attached to Johnston’s company; the men killed all the surviving Japanese but one, whom they captured. This prisoner later jumped into a trench and opened fire with a machine-gun, necessitating another charge by “R” Company. Maddern then ordered the survivors of Roff’s company under the only remaining officer, Lieutenant McLeod,77 to occupy a position on the forward slope of the ridge to protect the convoy as it and Trevena’s company moved through. From 6.5 p.m. the vehicles moved through Usau. Trevena’s company, fighting from a series of rearguard positions, had protected them against the strong enemy force in the rear; some vehicles, including two anti-tank vehicles, had been knocked out and two anti-tank guns

destroyed for lack of vehicles to tow them. Captain Groom78 had been wounded in this fighting, but carried on.

The convoy was halted one mile beyond Usau at 7 p.m.; picquets were posted and patrols sent out. Leggatt then sent his Intelligence officer, Lieutenant McCutcheon,79 forward in a carrier to find a defensive area and one where the force could be reorganised for an attack on Champlong. The strength of the force had been so reduced that Leggatt decided to move all the survivors forward in the vehicles. At this stage Captain Johnston was killed when moving forward to give orders to the head of the column. Maddern then went forward and issued orders for the move to begin, and the Intelligence officer reported that the area ahead was clear of the enemy. The men were now nearly exhausted. When, at 9 p.m., the convoy was still not moving Maddern went forward again and found the leading driver asleep. He set the column moving and it was at Airkom by 11.30. Some of the trucks had carried 30 men, and the Bofors tractors and guns carried up to 60.

Leggatt considered that the main body of the Japanese was behind him, but that other Japanese were certainly in Champlong. At midnight he ordered the reorganisation of the column; nine vehicles loaded with wounded were placed in the centre. At 4 a.m. Burr’s company was to be ready to move forward in trucks protected by carriers to contact the enemy at Champlong. At the conference at which these orders were given Leggatt pointed out that ammunition, rations and water were almost exhausted and the men were almost worn out; consequently it was necessary to take Champlong quickly to replenish supplies and prepare for further action. At this stage four officers had been killed and six wounded; 21 remained in the battalion and 21 in other units.

Soon after 6 a.m. on 23rd February Lieutenant Sharman’s platoon of Burr’s company moved off in two trucks preceded by a machine-gun carrier. No news had been received from this little force when, at 7.50, an enemy convoy led by light tanks towing field guns moved up to the tail of the column, the leading tank flying a flag thought at first to be white but later seen to be a furled Japanese flag. When this was realised, the tanks were so close to the rear of the Australian convoy that two antitank guns that had been manoeuvred into position could not be fired without endangering the Australians.

The commander of the Japanese force now called upon the Australians to surrender. He said that the Japanese, whose force totalled 23,000, were on both flanks and had one brigade in the rear; if there was no surrender by 10 a.m. the convoy would be bombed continuously and fire would be opened. Leggatt called his officers together and ordered them to obtain the feelings of the troops.

All companies and units were unanimous in the opinion that further resistance was useless, as the position in which the Force found itself meant annihilation if the battle was continued. All troops also indicated that they would continue to fight if Commander ordered it. The decision to surrender was made at 0900 hours 23 Feb 1942 and the Japanese made immediate arrangements for wounded to be moved back to Babau.

Many troops, including Major Chisholm of the 2/40th, who was in Champlong when the paratroops landed and was unable to rejoin the battalion, immediately dispersed into the hills; and the decision did not affect Lieutenant Sharman’s platoon, which, as mentioned, had set out towards Champlong at 6 a.m.80

At 10 a.m. a wave of Japanese bombers appeared and bombed both the Australian and the Japanese convoys, killing some in both forces and destroying four enemy tanks. They made a similar attack at 10.10, but when a third wave of bombers appeared the Japanese had placed many flags around and the aircraft did not attack.

–:–

From the beginning the 2/40th and its attached units, tied down to a defensive role, had little chance of doing more than delaying its eventual defeat by mobile forces possessing the initiative and having complete command of the sea and air. The battalion moved or fought for four days with little rest while its strength dwindled and its food and ammunition steadily became exhausted. On the last day it carried out a successful attack with three companies against a well-entrenched Japanese force on its front while at the same time defending its rear against a yet stronger Japanese force. At the time of the surrender the Australian battalion had practically no food or water, only 70,000 rounds of ammunition, 84 officers and men had been killed, and near the rear of its column nine trucks containing 132 wounded or seriously ill men were within close range of the enemy’s weapons.81

A severe handicap to the battalion throughout the fighting was the lack of effective communications.

Communications from battalion HQ to rifle companies was by runner (wrote Leggatt later) or personal contact by the CO or Adjutant. Radios were inadequate and did not work anyway, while line communication usually was possible only between battalion HQ and the 2 i/c and his HQ with the transport. For these reasons small battles were slowed up, and it was difficult indeed to take advantage immediately of success.

In later discussion Japanese stated that there were only seventy-eight survivors of the paratroops; that a Japanese company which had moved overland from the south coast and joined them had been destroyed; and that further toll had been taken by Trevena’s company in its rear-

guard action.82 The Australians discovered that the paratroops were armed with .258 carbines; a high proportion of .258 light machine-guns; approximately 2-inch mortars; and hand grenades. Each paratrooper carried a portion of cooked rice wrapped in oiled silk, and a tube filter through which water could be sucked direct into his mouth.

Those Japanese forces which, under the command of XVI Army, had been given the task of making a three-pronged advance from Mindanao to a line through Bandjermasin, Macassar and Timor, thus cutting off Java from the east, had now completed their work. The western of these forces comprised the 56th Regimental Group and the 2nd Kure Special Naval Landing Force (a battalion group of marines, about 1,000 strong). These had taken Tarakan, Balikpapan, and Bandjermasin in east and south Borneo. The central force comprised the Sasebo Combined Special Landing Force (a two-battalion regiment about 1,600 strong) and the 1st Yokosuka S.N.L.F., which was built round a battalion of 520 paratroops. This force had taken Menado and Kendari, and the Yokosuka had gone to Macassar. The eastern force included the headquarters of the 38th Division, the 228th Regimental Group (about 4,500 strong), the 1st Kure S.N.L.F. (820 strong), and the 3rd Yokosuka S.N.L.F. (a paratroop and infantry unit about 1,000 strong). As has been seen, the 228th and the Kure attacked Ambon, the 228th and the Yokosuka attacked Timor. The 56th Regiment was destined now to join the main body of the XVI Army in the invasion of Java. It will be seen that the two main forces closely resembled in composition the South Seas Force which had advanced to Rabaul: a combined army-navy force built round a brigade or regimental group plus one or more battalions of marines.

As mentioned, Brigadier Veale and Colonel Leggatt had been out of touch during the fighting. At Su, Veale had established outposts, and the Dutch commander at Atambua was instructed to report. He said that no Japanese had landed in his area, and he had no reports from Portuguese Timor. Veale instructed him to move his troops to Su.

On the 23rd Veale learnt that Leggatt had surrendered. Veale had no news from Portuguese Timor, and the only force still available to him comprised about 250 Australians, most of whom were in the Ordnance, Army Service, and Army Medical Corps, with only rifles and a few sub-machine-guns; and about 40 Dutch and Timorese troops. Dutch women and children were encamped about 10 miles north of Su; and the Dutch Resident was anxious to avoid fighting near them. In these circumstances Veale decided that the continued occupation of Su would serve no useful purpose, and now told the Dutch commander at Atambua, who had about 100 troops, to remain there instead of coming to Su. Veale further decided to send a party into Portuguese Timor to contact the Independent Company; and to move the rest of his force to Atambua, taking with him a wireless set possessed by the Dutch Resident. With this set he hoped to

speak to both Java and Australia, and ask that reinforcements be landed on the south coast near the Dutch-Portuguese border.

After an enemy convoy had approached the bridge over the Mina River on the 23rd, and had been fired on and withdrawn, the bridge was blown up (by Lieutenant Doig83) and the withdrawal to Atambua began. An outpost was left at the Benain River to destroy the bridge there if a large enemy force approached.

Atambua was a small town in level country flanked on the north by the coastal range and on the east by the mountainous area of the Portuguese border. A road led south, through open country to Besikama, and a fair-weather road led to Dili. Veale decided that if the Independent Company arrived from eastern Timor a stand would be made round Atambua as long as possible, the line of withdrawal being to the south coast and thence eastward into Portuguese Timor. He established posts at the crossroads at Halilulik and at Kefannanu.

On 25th February a Japanese force approached the Benain River; the outpost blew up the bridge and withdrew to Kefannanu. On the 27th Colonel van Straaten arrived from Dili, very fatigued, and reported that the Japanese had taken Dili on the 19th February and that his troops were following him; he had last seen the Independent Company about Villa Maria. He said his troops were very tired and he favoured distributing them in small parties among the villages.

Also on the 27th a strong group of Japanese mounted on ponies crossed the Benain River and advanced on Kefannanu. Veale now decided not to oppose van Straaten’s proposal to distribute his men; a major reason was the limited amount of food at Atambua. Veale decided also that, when the Japanese occupied Kefannanu, he would move most of the Australian troops to villages in the north coast area west of Atapupu, allow small organised parties to attempt to reach Australia, and himself move with a small reconnaissance party to south-west Portuguese Timor, where, he considered, there was the best chance of maintaining a force.

This plan was put into operation. All vehicles and surplus stores at Atambua were destroyed; the main body moved to the north coast; and three escape parties set out.84 Brigadier Veale, with Captains Arnold and Neave85 and ten other ranks set out for Portuguese Timor on 2nd March; and at the same time Captain Parker and some signallers moved east into Portuguese Timor in an effort to contact the Independent Company.

On the night of the 5th March Veale’s party met Lieutenant Laffy86 of the Independent Company, who was making a reconnaissance south of

Cailaco, and was in touch with Senhor de Sousa Santos, the Portuguese administrator of the Fronteira Province, with headquarters at Bobonaro.87 Laffy was told to instruct Major Spence to meet Brigadier Veale at Lolotoi, and Spence arrived there on the night of the 8th March.88

While Brigadier Veale’s party was moving eastward towards them the men of the Independent Company had been consolidating their position. As previously related, company headquarters had been established by the end of February at Villa Maria, and it was not then known that the 2/40th Battalion had surrendered. After Callinan had spent a day or so at the headquarters, he suggested to Spence that they should endeavour to get further instructions from Leggatt, and inform him that they were quite capable at present of carrying out their secondary role of protecting his rear. The only means of communication with Leggatt was by runner and the time required to cover the one hundred and twenty-odd miles would be considerable. It was agreed that Callinan should go, as he could speak with most responsibility to Leggatt. He set out with Lance-Sergeant Tomasetti89 and Sapper Wilby.90 At Laharus they learned that the main force had surrendered. A day was spent assisting Catholic missionaries to restore order locally, and sending messages by Timorese to all Australians in the area that the Independent Company was still fighting. One of these messages brought Captain Parker and party to Laharus, and they returned with Callinan to Cailaco.

On his way back to Cailaco, Callinan pondered what they should do now that the movement back along the road to Koepang was not only

unnecessary but also undesirable. He formulated a plan based upon earlier discussions with Baldwin about the desirability of having secure bases from which platoons could operate. The base areas for the platoons were selected from the map so that each had a town or village, printed in larger type on the map, within its base area, and they were approximately equally spaced along the southern side of the central range. The size of the type proved to be misleading as an indication of the relative size of the town or village, but the general areas selected were eventually taken up. One selection had, however, been made for them by de Sousa Santos, who had sent a message to Spence saying that troops could and should be quartered at Mape. Baldwin later established his headquarters there.

At Lolotoi on 8th March Brigadier Veale at last obtained a clear picture of the operations of the 2/2nd Independent Company and their present dispositions; and learnt that Callinan and Parker had already been in contact. Veale then set up his headquarters at Maucatar.

The spirit of the Independent Company at this time was evident in their uncompromising response to a demand by the Japanese for their surrender, brought by Ross from Dili. Ross travelled under Japanese escort as far as Liquissa, and thence made his way to Hatu-Lia. He said he had been told by the Japanese commander that all fighting in Dutch Timor had ceased, and that as the Australians in Portuguese Timor were part of Sparrow Force, they also should surrender. If they did not, they would be declared outlaws and if captured would be executed. The reply, swiftly decided upon at a conference of senior officers of the company with Ross on 15th March, was that the company was still a unit, and would fight on.91

–:–

Again, as at Rabaul and Ambon, the Japanese invasion of Timor had been supported by the Japanese Carrier Fleet. It was this fleet which, at dawn on the 19th February, had launched 81 aircraft at Darwin to neutralise that base in preparation for the coming operations in the Indies. These 81 were joined by 54 land-based aircraft from Kendari; and in the afternoon a second attack was made, by another 54 aircraft. At Darwin or near jt the raiders sank the American destroyer Peary, four American transports, a British tanker, two large Australian ships and two small ones, killed 238 people and destroyed 10 aircraft.92

The plan of attack on Dutch Timor was to land the main part of the force south of the Koepang area with the airfield as a main objective. Part of the 228th Regiment was given the task of cutting off the defenders’ withdrawal to the east. The paratroops were to be dropped about Usau and to cooperate in the attack on the airfields. On the first day the main part of the force reached an east-west line about the centre of the western tip of the island; next day it advanced to Koepang airfield. On this day the right battalion of the regiment became engaged in “desperate” fighting with the Australians withdrawing eastward, whereupon the remainder of the regiment swung east and attacked them, eventually capturing the main body of the Australians near Usau. The Japanese believed that they encountered 1,300 Australians and Dutch troops at Dili. What proportion of the Japanese force landed at Dili could not be ascertained.

A striking demonstration of the flexibility possessed by the army of a Power which commands the sea and air had been given by the 228th Regiment. It had taken part in the operations against Hong Kong in December; played the main part in the conquest of Ambon in January-February, and now had repeated the achievement in the taking of Timor in February. It will reappear in another theatre in the next volume of this series.