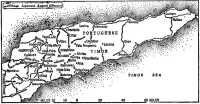

Appendix 2: Timor

AFTER resistance by the main part of Sparrow Force had ceased in Dutch Timor on 23rd February 1942, and after men of Major A. Spence’s 2/2nd Independent Company had met the Japanese invaders of Portuguese Timor in a series of small but spirited encounters, the leaders of the Independent Company began to reorganise and redeploy their troops in the southern half of Portuguese Timor about the middle of March.1 Company headquarters was to be established at Atsabe; Captain R. R. Baldwin’s “A” Platoon was to be stationed in the Bobonaro area; Captain G. G. Laidlaw’s “B” Platoon round Same; Captain G. Boyland’s “C” Platoon was to remain deployed in the most northerly positions—in the Hatu–Lia area.

Meanwhile Spence had been down to Lolotoi and had discussed the situation with Brigadier W. C. D. Veale, the Sparrow Force commander who, with a small group of his officers and men, had evaded capture by the Japanese. Veale and Spence agreed that the small bands of Australian and Dutch troops who were still at large in Dutch Timor should be called together at Atambua and thence cross the border and join the Independent Company.

The guerrillas, by this time, were suffering badly. They were faced with the task of existing where a complete force had failed to survive. Their last news from Australia had been that Japanese aircraft had raided Darwin heavily on 19th February. Except for scraps from some Dutch radio stations they had since been cut off from news of the rest of the outside world—and when they had fragments of the Dutch broadcasts translated it was only to learn, on 9th March, that the whole of the Netherlands East Indies had surrendered to the Japanese. They were usually hungry. They were wasted with malaria and had little quinine Their boots were becoming mere remnants of leather about their feet. Despite all this, however, they kept their spirits high.

When Mr David Ross, the Australian Consul at Dili who had been held captive there by the Japanese, was sent to seek out the guerrillas with demands for their surrender, he was amazed to find them in such good heart. The senior officers of the company had gathered at Hatu–Lia to meet him on 16th March. He gave to each of them a note saying that any orders for food or other commodities signed by that officer would later be honoured by the British and Australian Governments. He gave them detailed information regarding the defences of Dili and the near-by aerodrome to aid them in raids they were planning. He took back with him to Dili their scornful refusal to surrender.

Portuguese Timor

Gradually, aided to some extent by Ross’ notes, to a very large extent by the unremitting efforts of Senhor Antonio Policarpe de Sousa Santos, who was in charge of the Fronteira Province, and by their own efforts at organising supplies, their food situation greatly improved and they could look forward to obtaining reasonably adequate supplies from the local residents. Their planning and deployment were made easier because the Portuguese let them use the telephone system which linked the various Portuguese administrative posts. They had large reserves of ammunition which they had built up in the inland areas before the arrival of the Japanese, though sub-machine-gun ammunition was short. Their own vigorous and wide patrolling, information coming to them from native sources, and a constant flow of information through Santos, kept them well aware of the Japanese movements. By the end of March practically all of the remnants of the main force from Dutch Timor (approximately 200) had been safely collected in the South-west corner of the Portuguese territory (though they were mostly unarmed and many were ill and they remained under the direct command of Veale who set up his headquarters at Mape); about 40 armed and fit men from this group under Major J. Chisholm, a brave and vigorous officer of the 2/40th Battalion, were watching the frontier from a base at Memo; some 150 Dutch troops were also gathered in the South-west of the colony, spreading into Dutch Timor, and gradually being reorganised there by Colonel N. L. W. van Straaten; ammunition which had been stored at Atambua had been safely got away before the Japanese occupied that area at the beginning of April, and was a useful addition to Spence’s reserves.

Early April, therefore, found the forces on Timor in a far better position than they might have hoped for only a few weeks earlier. By that time, however, the Japanese were once more on the move inland. Major B. J. Callinan, Spence’s tireless and brave second-in-command, had gone forward to the Hatu–Lia area to relieve Boyland temporarily in command

of “C” Platoon. He took with him Lieutenant Turton2 who commanded the Independent Company’s engineer section. They found Lieutenants Burridge3 and Cole4 of Boyland’s platoon, with their sections, at Hatu-Lia and, while they were there, Lieutenant Cardy5 (of Laidlaw’s platoon), who had been on a wide patrol, came in. Soon Callinan and Turton pushed forward towards Taco–Lulic ordering Burridge and Cole to follow behind them and sending Cardy to sortie against the Japanese from the north of the road which led from Dili. As they approached Taco–Lulic at the end of the day they saw Japanese moving up the road towards them. Next day they watched these from high ground. The day afterwards they narrowly escaped parties searching for them and were themselves frustrated in an attempted ambush. It became clear that the Japanese were interested in moving up the roads which led to Ermera and Hatu–Lia. During the days following, the swift-moving Australians clashed sharply with the advancing Japanese and claimed 30 or 40 killed, without casualties to themselves, before the invaders occupied Ermera. Outflanked, the guerrillas then withdrew and later, from Villa Maria, watched the Japanese feeling out along the road towards them. By 9th April, however, these feelers had coalesced into a movement by about 500 men towards Hatu–Lia and the most forward commandos fell back—to Lete–Foho. But the Japanese pressed farther on and, on 13th April, after shelling the little town they occupied it and once again the Australians fell back. What really worried them, however, was uncertainty as to whether the invaders would stop at Lete–Foho, or would press on—to Atsabe or still farther to Ainaro—and menace the Australian bases. In the event, however, the forward movement not only ceased at Lete–Foho but, by the end of April, the Japanese had all withdrawn to Ermera and Dili, having suffered annoying losses to the harassing tactics of the guerrillas.

Typical of these tactics were actions fought during the month by Lieutenants Turton and Rose6 and Lance-Corporal Thompson7 and Corporal Taylor.8 On 15th April Turton led a party of his sappers in a sortie to demolish the Dili—Hatu–Lia road north of Ermera. Encountering a party of Japanese at close quarters they claimed to have killed six of them. Soon afterwards two of Turton’s men, Thompson and Sapper March,9 ambushed a party who had been moving along the road and

who alighted from a truck near the Australians. When the two commandos opened fire the driver of the truck made off with his vehicle and left his passengers on the road as targets for the two ambushers who raked them with Bren gun fire and later reported that they thought they had killed 35. On 24th April Taylor and three men, who had been lying in wait for two days, opened up on four trucks which were driving along the road. They wrecked one of these and thought that they left about 30 dead behind them when they disappeared once more into the bush. Next day Rose and four men waylaid a truck load of enemy soldiers near Villa Maria. The approach of a large convoy forced them to take to the bush, however, before they completed their work, though they claimed 12 Japanese dead for their efforts and gave the credit for eight of these to Private Wheatley10 who was renowned among them for his accurate sniping.

By the end of April not only were the Australians settling to their grim task with practised skill but a marked improvement in their general situation was promised through their opening of a radio link with Darwin. For some time a small group of their signalmen had been at work at Mape attempting (with the generous and skilled help of de Sousa Santos) to build a transmitting set. The most expert and tireless of these was Signalman Loveless,11 and for some time much of the Australian patrolling was directed towards getting parts for his transmitter. When Captain G. E. Parker, who had been the Sparrow Force signals officer, arrived from Dutch Timor, he was able to advance the work Loveless had so skilfully and patiently developed. On 20th April the weak transmitter which they had contrived was heard in Darwin. However, on the night on which contact was established the batteries failed, and the message had to be continued the following night. The first message had been a simple cipher, using as a keyword the name of an officer. Clues were given in clear as the identity of the officer. That first signal was prefaced by the priorities normally reserved to the Commanders-in-Chief of the Services, but it was felt that something had to be done to attract attention. It was certainly effective as the operator could hear all stations close down and concentrate upon “Winnie the War Winner”, as the set had been affectionately named.

The set occupied a room about ten feet square (Callinan wrote later), and there were bits and pieces spread around on benches and joined by wires trailing across the floor. Batteries were charged by a generator taken from an old car and driven by a rope which passed around a small grooved wheel attached to the armature of the generator and around a similar wheel about eighteen inches in diameter. Attached to this latter wheel was another wheel around which a further rope passed on to a wheel about four feet or more in diameter, and to this large wheel were fixed handles by which four natives turned the machine. This was a further example of the work of Sousa Santos, as the whole of this battery charging device had been built under his orders.12

Strangely, this painfully contrived set had been operating for scarcely a week before Lieutenant Garnett13 handed over a second receiving and transmitting set to the signallers, complete and in good order. This had belonged to Qantas Empire Airways. During a long and difficult patrol Garnett got in touch with some Portuguese “deportados” on the outskirts of Dili. These were men who, because of revolutionary activities, had been banished for varying periods from Portugal itself to the most distant of the Portuguese possessions. Under Garnett’s initial prompting they became actively helpful to the Australians and operated with them later in a small and colourful group, usually not more than about six in number, which the Australians called “the International Brigade”. Some deportados, led by Pedro Guerre, sneaked the Qantas set out of Dili one night under the noses of the Japanese and passed it over to Garnett who then got it back across practically the whole width of the island to the force headquarters where the signallers used it to supplement the efforts of “Winnie the War Winner”.

Meanwhile, back in Australia there had been astonishment and, at first, some doubt when the signals from the forces still fighting on Timor were picked up in the Northern Territory. The doubts, however, were quickly resolved and arrangements were made for the air force to reconnoitre the Dili area on 23rd April and, on picking up visual signals from the ground, to drop batteries and other supplies. In the event, however, the first Hudson aircraft did not get over the Sparrow Force area until 24th April and, unable to pick up any signals, it brought back the batteries and medical stores which it carried. Acting on instructions from Darwin Veale’s headquarters then had signal fires burning as aircraft recognition signals round Mape on 26th April. The aeroplanes, however, flying too far to the north, did not pick up the signals, and, once again, could not drop their stores. But the following day the first drop took place: parachute deliveries of 19 packages at 5 p.m. on 27th April, at Beco. More drops took place on 3rd and 8th May. The period of Sparrow Force’s isolation was ended.

While these arrangements were being made, however, the future of Sparrow Force was being anxiously considered by the army leaders in Australia. On 28th April Major-General Herring’s Northern Territory Force Headquarters reported to Army Headquarters a Sparrow Force signal that, if it were intended to retake Timor from the Japanese (whose main strength—at Dili—Sparrow Force estimated to be 1,500) within one month, the men on the island, reinforced by 300 guerrillas, could effectively mop up the Japanese if their own position did not deteriorate badly in the meantime; that, however, if they were not thus reinforced, Sparrow Force could not achieve anything really effective. Next day Herring proposed to inform Sparrow Force that Army Headquarters wished to impress on them that the matter of early relief presented many difficulties; that air assistance would be limited to dropping essential

supplies but that this assistance would not be on any regular schedule; that it was vitally important that the men on Timor should maintain an offensive spirit and continue their guerrilla activities and should keep up a flow of information with a view to the later use of Timor as a base for extending guerrilla activities to other islands in the vicinity; that there was no possibility of evacuation in the immediate future. On 3rd May Land Force Headquarters told Herring that they had no present intention to reinforce Sparrow Force but intended to maintain them.

By that time the general Sparrow Force plan was to attack Dili from the east and so draw off Japanese troops in that direction while other Australians harassed the Japanese west of Dili.

The essence of this latter policy was for a body of troops to harass the enemy and, when attacked, to divide and move off in opposite directions at right angles to the line of the Japanese advance. This then gave the Japanese two alternatives, either to pursue our troops and so split their own force, or to push on and ignore our troops. Should they push on, or not continue the pursuit of our troops, then we would come back on their rear and flanks. Ground of itself was not important; the main object was to kill, and our best method of killing was by sharp harassing actions.14

Accordingly, by the end of April, an extensive Australian re-deployment had been almost completed. Laidlaw’s platoon was carrying out a wide and difficult movement to establish themselves at Remexio, fairly close in to Dili; Boyland’s platoon was settling in the Maubisse area; a new platoon (“D”), which had been formed from the Independent Company’s sappers and from the fittest of the survivors from Dutch Timor, had been gathered at Mape and given a short intensive course of guerrilla training, and, by early May, would be based on Atsabe under the command of Turton, who, though gentle by nature, was already proving himself an outstanding soldier and guerrilla engineer; Baldwin’s platoon (which had been scattered widely to fill gaps as they developed) was to have the left flank positions in the general area of Cailaco.

Thus the Australians were settling themselves in an arc from the outskirts of Dili to Cailaco, well sited to harass the main Japanese forward base which had developed at Ermera and its lines of communication with the main base at Dili. This arc extended over about 60 miles and was manned by a little over 300 fighting troops. South of it, at Ainaro, Captain C. R. Dunkley, the company’s medical officer, established his hospital and a rest centre early in May. Previously his hospital had been at Same. To it the sick and wounded had been transported from the section positions under the most difficult conditions—carried on stretchers for long days over bridle paths and tracks which wound through rugged country or, more often, borne on the backs of small but hardy Timor ponies. Ainaro was almost ideal for Dunkley’s purposes. It had been an early missionary centre and was the site of the oldest administrative post on the island. It was a rich area, its natives were friendly Christians, it contained some fine buildings and an existing hospital which Dunkley

took over. As their centre developed there the Australians fed to it the men who, for various reasons, had become physically ineffective—not only commandos but survivors from Dutch Timor. After they were treated in hospital and rested they went to training squads under officers and NCO’s from neighbouring sections. Men who responded to training were sent forward to platoons as reinforcements; others were given additional medical treatment and rest and training; those who seemed unlikely to make good at all were held in the area for possible evacuation.

During May the Australians busied themselves by chopping at -the Japanese whenever opportunity offered—and the existence of the Ermera base played nicely into their hands for traffic between Dili and Ermera was constant—demolishing sections of the roads, destroying bridges at key-points. Callinan has recorded:

One typical raid was carried out by Sergeant James,15 who with two sappers sat less than one hundred yards from a Japanese post for two days. When he knew the routine of the post well, he decided that the best time to strike was just as the enemy were having breakfast. So the following morning there was a sharp burst of fire and twelve Japanese were killed, the raiders disappearing into the scrub.

It was seldom that a week went past without two or three successful raids being carried out. The individual number of Japanese casualties was small; it might be five or as high as fifteen, but these numbers quickly provided an amazing total, and their effect on Japanese morale was enormous. Japanese soldiers told natives that the Australians were devils who jumped out of the ground, killed some Japanese and then disappeared, whilst their officers complained that though they had been fighting them for months, many had never seen an Australian.

In an attempt to obtain support from the natives, the Japanese placed a price of one hundred pataccas—approximately eight pounds—on the head of each Australian soldier, and one of a thousand pataccas—approximately eighty pounds—on the head of the Australian commander and “Captain Callinan”. ...

As these pin-pricking raids of ours continued, the Japanese came to blame us for everything that happened, and this is the pinnacle of success for a harassing force. It is a state of mind induced by numerous fruitless endeavours to deal with an enemy who seems able to deal a blow anywhere at any time, but who remains elusive.16

In May the Australians prepared the boldest single blow they had yet planned against their enemies. On the afternoon of 15th May, from their base at Remexio, Laidlaw led down towards Dili some 20 of his men, under the direct command of Lieutenant T. G. Nisbet. They had blackened themselves with soot and grime. After night came they crept up to the defending wire which fronted them. They planned to kill silently the Japanese sentries whom they expected to find there. It took them some time to discover, however, that there were none. They then passed quietly through the wire and, by way of the deep drains which flanked them, along the silent streets. There were lamps burning in huts and houses which they passed and in these huts they could see Japanese resting or talking. Laidlaw approached a machine-gun position. To a Japanese there he was just a shape bulking in the darkness and the soldier spoke to him. Laidlaw

shot him in the stomach with a .45-inch revolver at three yards’ range. As he fell Nisbet and Lance-Sergeant Morgan17 almost tore him apart with rifle and sub-machine-gun fire. The whole of the attacking party opened up. Their fire poured into the near-by huts, beat against the walls, shot down disorganised defenders who rushed out of the buildings or milled in confusion. After about ten minutes of this mêlée (at 1.15 a.m.) the attackers began to withdraw, fire from Lieutenant Garnett and his men, who had taken up a position on the beach just outside the town for this purpose, covering them and causing more panic and confusion among the garrison. All the Australians got clean away and the Japanese were apparently too disorganised to arrange any immediate pursuit.

On 22nd May, however, a party of them was moving on Remexio. Lance-Sergeant W. E. Tomasetti and Lance-Corporal Kirkwood,18 with the little “International Brigade”, killed 4 or 5 of them about 4 a.m. before they themselves broke into the bush. Warned by the firing Corporal Aitken’s19 men, farther out along the track, lay waiting in an ambush which they sprang about 10 a.m. They said they shot down about 25 Japanese and the rest then fell back. (Among the first Japanese to fall was “the Singapore Tiger”—a Japanese major, ruthless and versed in bush fighting, so reports said, who had been brought down specially from Singapore to deal with the Australians.) Next day, however, a Japanese party about 200 strong moved on Remexio, but the Australians had melted away. On 26th May the Japanese returned to Dili. The Australians then returned to Remexio.

By this time the spirits of the Australians on Timor were very high. They were operating vigorously and efficiently—a picturesque band, tattered, bearded, each man accompanied by one or more loyal natives (creados) to assist and serve him personally. The two air drops in April and additional drops on 3rd, 8th and 23rd May had made good their most urgent needs. On 24th May a Catalina flying-boat brought more stores from Darwin and (since his own personal role had necessarily been a limited one and the information he could bring back to Australia was valuable) it took Brigadier Veale out on its return flight. With him went also the Dutch commander, van Straaten, 3 wounded and 4 sick men. Spence, promoted Lieut-colonel, replaced him as the force commander and Callinan was promoted to command the Independent Company. Baldwin became Callinan’s second-in-command and Lieutenant Dexter,20 stocky, strong and laughter-loving, took over “A” Platoon. Early in the evening of 27th May HMAS Kuru (a naval launch with a cargo capacity of 5 or 6 tons) ran in on the first of what was to become a series of regular

trips by it and HMAS Vigilant (capable of carrying about 7 tons) from Darwin.

The establishment of this regular and efficient system of supply by sea followed firm decisions taken early in June by Generals MacArthur and Blamey regarding their future operations on Timor. On 3rd June Blamey suggested to MacArthur that two courses of action were open to him: to recapture Timor with an overseas expedition; or to withdraw the bulk of the forces then there. MacArthur replied on the 11th:

To attack Timor would require at least two brigades, perhaps a division. Success would require that this force be carefully trained in landings on hostile shores, be equipped with suitable ships and landing craft and be strongly supported by air and naval forces. A careful review of our present position indicates that a number of these requisites are lacking. Without them such an expedition has little chance of success and cannot therefore be considered with the means now available.

The withdrawal of the bulk of the present garrison from Timor does not present any great difficulty. Such a plan, no doubt, could be successfully executed. However, the retention of these forces at Timor will greatly facilitate offensive action when the necessary means are at hand. These forces should not be withdrawn under existing circumstances. Rather, it is believed that they should remain and execute their present missions of harassment and sabotage.

The retention of the bulk of these forces at Timor will necessitate a carefully prepared plan of supply and a plan for the withdrawal of the garrison in case the Japanese make a sustained offensive against them.

Accordingly a link between Australia and Timor was firmly and quickly established. A plan was developed through which supplies (to supplement those the guerrillas got from the land, off which they lived substantially during the whole of their stay on the island) were to be delivered from Australia on the basis of a monthly schedule of requirements, with all stores marked in Darwin for delivery direct to platoons and headquarters and packed before dispatch in watertight containers in 100-pound pony loads and 40-pound man-loads. This system was to be supplemented by droppings from Hudson aircraft to meet urgent demands at short notice. The development of the sea route meant also that the Hudsons could be used for the most part to attack targets on information supplied by the troops in Timor and such attacks on key Japanese points (particularly Ermera and Dili) became a feature of the operations.

June passed fairly quietly though marked by a series of small but vigorous forays by the men of the improvised “D” Platoon. It was marked also by a reorganisation of the Dutch forces so that they closely covered the South-west border and extended the line of the Australian positions with the result that the combined line, though jagged and not, of course, capable of complete integration, stretched Northeast across the whole of Portuguese Timor to the vicinity of Dili.

Meanwhile, on 9th and 11th June, the Australian Government had learnt through the Dominions Office of a proposal by the Portuguese Government that that government should open negotiations for the withdrawal of the Japanese in return for the surrender of the Australian troops to the Portuguese authorities for internment in Portuguese Timor. The

Australian Chiefs of Staff advised that the proposal be rejected and General MacArthur concurred.

Late in June Ross arrived once more in the Australian positions having been sent out by the Japanese with a second surrender demand. He had warned both the Japanese consul and commander that there was no hope that the Australians would fall in with the demand, particularly as they knew that some of their men who had been taken in February had been murdered. The Japanese commander was most indignant at what he considered this reflection upon the behaviour of Japanese soldiers. He was emphatic that neither he nor any soldiers under his command had ever caused the death of prisoners and added that he, personally, had taken the Australian surrender at Ambon. He gave Ross an undertaking, addressed to the Independent Company commander and signed both by himself and the consul, which read:

In the name of the Imperial Japanese Government, we hereby guarantee that all Australian soldiers under your command, who surrender to the Japanese Force now in Portuguese Timor, will receive proper treatment as prisoners of war in accordance with International Law.

He also asked Ross to give his compliments to the Australian commander and tell him how much he admired the way in which the Australians had fought and kept on fighting. He added, however, that he thought that they should come into Dili and fight it out to the last man. If they would not do this he would take his men into the hills and fight it out there. Ross said that there were not sufficient Japanese in Timor to round up the Australians. The colonel agreed and admitted that, from his reading about the Boer War, and from his own experiences in Manchuria, he believed that it required about ten regular soldiers to kill each guerrilla. He then added “I will get what is required”.

When Ross arrived at Spence’s headquarters at Mape the Australians gave the Japanese offer scant consideration, and, since Ross had not promised to return to Dili, he remained with them and later was sent out to Australia, where on 16th July, he described the situation on Timor to the Advisory War Council.

As July advanced, however, there were disturbing signs that the Japanese commander’s threat was no idle one. Rumours, and reports from the Dili observation post, came to the hills of the arrival of fresh troops at Dili and accretions to the Japanese forces in Dutch Timor. The invaders withdrew to Dili from their forward positions at Ermera and, though the Australian patrols pressed closely in on Dili itself and busied themselves demolishing and blocking roads and destroying key-points, they found the Japanese strangely passive, as though they were gathering and containing themselves for a major effort. There were disturbing and increasing indications also that some natives were becoming not only unfriendly but actively threatening to the Australians.

On 9th August the Japanese methodically bombed Beco and Mape. Next day the bombers were over Mape again and also attacked Bobonaro,

where Callinan had his headquarters, and the near-by Marobo, thus ushering in a series of raids on the villages which the Australians had been using as their key-points. It quickly became clear that the Japanese were launched on a widespread and well-organised move to envelop and destroy the Australians and the Dutch. The pattern which subsequently emerged was that perhaps 1,500 to 2,000 Japanese were on the move; that one column was striking south from Manatuto; two struck out from Dili itself, one South-east then south by way of Remexio, one due south through Aileu; another crossed the border at Memo and drove at Bobonaro through Maliana; attacks from Dutch Timor developed against the Dutch positions in the South-west round Maucatar; a party landed at Beco (but in a rather disorganised state after effective attacks on their convoy by 18 Hudsons).

The bombings drove Spence and his headquarters out of Mape and they lost touch temporarily with the main forces. The Portuguese telephone system of which the Australians had been making full use was disrupted and Callinan moved a few miles out of Bobonaro and set up a wireless control through which he was able to keep in close touch with his platoons.

In the most northerly sector Laidlaw, learning of the Japanese approach, left Remexio and, the following day, before an advance of 500 or 600 Japanese, withdrew towards Liltai. His men harassed the Japanese in a series of well-planned encounters as the Japanese felt their way towards Liltai. They hit them hard when the attackers entered Liltai on the night of the 13th and then later swung away to the east to gnaw at their flanks and rear as they went on from Liltai. The Australian platoon lost one man killed. They were fortunate, however, to escape so lightly from the Liltai area as they were almost taken by surprise there by the convergence with the column they had been engaging of the one which had moved unexpectedly from Manatuto. Corporal Loud,21 in the most forward position, skilfully extracted his sub-section and left the converging Japanese forces hotly engaging one another over the space he had left.

Boyland, meanwhile, from his positions north of Aileu, had been harassing the force which had come south from Dili. But he was pushed beyond Aileu and then fell back on Maubisse. As the Japanese advanced he was then driven farther south again.

Perhaps the most difficult fighting, however, developed in the western sector where Dexter had his platoon based on Rita Bau, and Turton was based on Atsabe farther to the east. As the Japanese advanced, Dexter, fighting hard and manoeuvring skilfully, found his movements hampered by natives (mostly from Dutch Timor) whom the Japanese were using to screen their advance. These natives moved among the bewildered local villagers and completed the demoralisation which the bombings had begun, the locals reasoning that surely this time the end had come for the Australians and no sensible man would side with the losers. Dexter’s men fell back towards Bobonaro. Just outside the town one of his sections was

almost surrounded and there Private Waller22 (one of the company’s three sets of brothers) was killed. At Bobonaro the column which had come from Memo and the party which had landed at Beco came together on the morning of 13th August and Dexter then joined forces with Turton to fight from a narrow saddle through which the road from Bobonaro passed to Atsabe. On the 14th Dexter himself remained in ambush at the saddle, where he was later joined by Sergeant Hodgson23 and some other men of Turton’s platoon so that the total ambush numbers became 28, while the rest of the group fell back to Atsabe. After a sharp clash Dexter led his ambushers also back to Atsabe.

Meanwhile Callinan himself and his company headquarters had found themselves almost cut off by the Japanese advance through Bobonaro. They therefore struck into the high mountains to the Northeast and, after two very cold and hungry days, swung down into Ainaro. There Callinan learned that Dexter and Turton had been forced beyond Atsabe, that Boyland had been pushed back beyond Maubisse and that there was nothing now in front of the Japanese moving down from Liltai. As he set about reorganising his company he knew that he was in a desperate position. The men were very tired and had had little food since the fighting began; small though his transport requirements were they were difficult to satisfy; he had little petrol left for use in his battery chargers and only a few serviceable batteries. At this stage he sent urgent messages off to Australia for money “to coax food and transport from the natives, and for batteries to maintain our vital communications. The same day the gallant Hudsons of RAAF were over us dropping the vital supplies. This magnificently prompt and effective help cheered us and the three short bursts from the planes’ guns as they passed over our headquarters on their way back to Australia was a salute we returned in our hearts.”

As the Australian commander, with the Japanese closing in, prepared orders for issue on the 19th for an Australian attack which he hoped desperately might stave off the necessity for breaking away into the largely unknown and difficult country to the east, the end came. On the night of the 18th–19th the Japanese shot a green flare high into the darkness above Same. The Australians felt that this was to signal the final movement towards their destruction or dispersal. But their wary patrols could find no evidence the next day of advancing enemies and then, incredulously, discovered that their attackers were withdrawing. They hurried after them, harassing their rear and flanks.

Though this withdrawal meant at least a temporary relief for the Australians from pressure by the Japanese, troubles with the natives threatened to become increasingly acute. These took the form in late August and during September largely of clashes between Portuguese and the natives

and between rival bands of natives. In the latter part of August the Maubisse natives rebelled against the Portuguese authority and killed the Portuguese administrator in that area. Detachments of Portuguese police and soldiers at once took to the hills to quell the disorders, having first been assured that the Australians would in no way interfere in these matters of local administration. On 27th August a native band some 200 strong, armed with knives, spears and bows and arrows, set out from Ainaro for Maubisse to join in the hunt for the rebels. Seeing this the Australians felt that they were witnessing merely the opening scenes of large-scale disorders which could not fail to react on their own situation. September made this clearer. The Japanese were obviously fomenting the disorders. How long, therefore, the Australians could hold aloof and regard the troubles as purely domestic was a subject for interesting speculation.

The private local war, Portuguese versus native, still goes on its bloodthirsty way and provides some humour for sub-units here and there (wrote the war diarist of the Independent Company on 3rd September). One of our patrols near Mape, out hunting the Jap, encountered a Portuguese patrol out hunting some natives; they exchanged compliments and went their various ways. Coy HQ witnessed the spectacle of about 3,000 natives, all in war dress and armed to the teeth, also complete with drums and Portuguese flags, returning from the hunt with many of them nonchalantly swinging heads of the unfortunate in battle.

During September there was much Japanese movement inland and along the north coast. The Australians learned that a complete fresh division had relieved the original Japanese garrison of Timor about the beginning of the month.24 There were reports also that the new regime was imposing much more rigid security precautions in and around the capital. On 12th September Portuguese reported to the guerrillas that a strong force of Japanese and Dutch Timor natives were moving from Dutch Timor across to Dili—on the route through Hatu–Lia and Ermera. It seemed that they might have the triple purpose of reconnoitring the roads, reinforcing Dili and fomenting the native disorders. Dexter and Turton sent men to keep a close check on the movements of this band. Turton said that the natives of the areas through which this force was passing seemed to be greatly impressed by its strength. Between 10th and 20th September Japanese troops landed at Manatuto and, though some returned soon to Dili, some pressed farther out along the north coast. At the same time a strong sortie was being launched to the south from Dili. On 21st September a party of about 400 Japanese, many natives accompanying them, entered Aileu, and next day reached Maubisse. Boyland’s opinion that they would continue on from there was confirmed on the 23rd when about 150 moved out towards Ainaro, and were smartly engaged by Lieutenant Burridge’s section, who thought that they killed or wounded about 30, without loss

to themselves. Burridge reported that two other parties were following the one which he had engaged, all three parties totalling about 350. In the early afternoon of the 24th Dexter (who had been telephoned from Maubisse by the local Japanese commander that he was coming to destroy Dexter and his men), Turton and their men, from cleverly arranged ambushes, shot many of the invaders and the fight did not flicker out finally until evening. Next day, however, the Japanese occupied Ainaro, with Turton’s and Dexter’s platoons watching and waiting for a chance to harass them from positions about the town and Boyland’s men waiting farther back towards Maubisse to worry them if they retraced their steps.

Meanwhile the Australian strength on Timor had been augmented. On 12th August General Blamey’s headquarters in Brisbane had told Major-General Stevens, then commanding the Northern Territory Force and under whose command Sparrow Force had been placed as from 30th July, that they were considering sending a small force to Timor to relieve the pressure on the troops already there and clear the Japanese from the Australian area. They envisaged a maximum strength for this force of some 500. Stevens replied that the minimum Japanese strength for operations against the guerrillas in Timor was certainly four if not five battalions; that he believed that the sending of two more Australian companies to the island would lead to useless sacrifice; that, if any more troops were to be sent, they should be of brigade strength to guarantee a successful outcome; he had not the forces available in the Northern Territory to make such a move. Finally, however, it was decided that the 2/4th Independent Company should go.

This company had been formed under the command of Major Walker25 at the beginning of 1942 round a core of officers and NCO’s who had been recruited and, in some measure, trained for Independent Companies in 1941, had been diverted to other duties when the decision to discontinue the training of Independent Companies was taken, and had been recalled when this decision was reversed. Walker took his company to the Northern Territory in March 1942, where they were based on Katherine, and set them to work watching and patrolling the lines of approach into the Territory along the Roper, Victoria and Daly Rivers. They were relieved in August by the 2/6th Cavalry Regiment and the North Australia Observer Unit and attached to the 19th Brigade for administration and training. On 9th September, General Stevens told Walker to take his company to Timor, establish observation posts over Dili, obtain information regarding the Japanese and harass these soldiers at every opportunity; but to be wary until he and his men had got to know the country and the natives. Walker then left with an advanced party from Darwin on 12th September and was busy with Callinan getting the local picture when the main body of his company embarked at Darwin on 22nd September in the destroyer Voyager. The ship began to unload off Betano in the late afternoon of the 23rd. Then she went aground. The

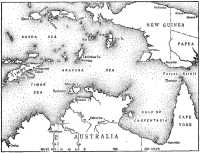

Timor–Northern Australia area

disembarkation went ahead but the falling tide left the ship fast on the sea-bed. Next morning a Japanese reconnaissance aeroplane found her there and hurried back to Dili with the news. A little later three more aircraft appeared. Seamen manned the anti-aircraft guns on the stranded vessel and engaged the Japanese. They thought they destroyed a bomber. Then the ship was attacked repeatedly though the seamen engaged the attackers and most of the bombs went wide. As the day advanced the captain ordered that the Voyager be destroyed. Her crew set off a series of explosions and then lit fires to complete her destruction. They themselves were picked up soon afterwards by the corvettes Warrnambool and Kalgoorlie.

Walker’s men, however, had not waited to see the final acts of this drama played out but had hurried inland to join the forward troops of the other company. For experience of the country and of active guerrilla operations they were then attached to these veterans (whom General Stevens did not consider it practicable to withdraw for some time). Meanwhile Dexter’s and Turton’s platoons had been watching the Japanese in Ainaro, Boyland’s had been waiting for a chance to strike between Ainaro and Maubisse, and Laidlaw’s men were in their old area east of Dili. But, on the 27th, Dexter’s patrols entered Ainaro to find that the Japanese had eluded them temporarily by swinging away Northwest to Atsabe.

On the 27th26 also some 2,000 Japanese moved south from Dili to Aileu. The next day strong forces, screened by native scouts, continued on to Maubisse, with the Australians making ready to harass them at the first suitable opportunity. This, it seemed, was an expected Japanese movement of strong forces to the area where the Voyager had been stranded, the Japanese knowing that fresh Australians had landed, but not in what strength. When the Japanese vanguard left Maubisse on the 29th, Boyland’s platoon, and Captain Thompson’s27 of the 2/4th, fought them from a series of ambush positions and believed that they killed about 50 (losing themselves one of the 2/4th men). But these Japanese were determined fighters, coolly proceeded to outflank the ambushers, and forced them to fall back to positions south of Same. After that the Australians lost touch with their enemies and, after a few days had passed with guerrilla patrols trying to locate the main Japanese party, it became clear that the Japanese had got through to Betano and were then on their way back to their northern bases. They settled in Aileu with outposts at Maubisse. About this time too it was known that the Japanese were developing the eastern end of the island, moving troops and stores along the north coast road east of Manatuto, building airstrips at Fuiloro (east of Baucau).

Closely watching, and at times harassing, these developments to the east was a 2/2nd Independent Company group under Lieutenant C. D. Doig, known as “H” Detachment. Early in August eight men and Doig, already proved an active young leader, had set out to watch the main road which crossed the island from Baucau in the north to Beasso on the south coast, map and patrol the area, and to send food and horses back to the main body. They had done well. They had become very familiar with the eastern country, had established good relations with the natives, and had kept horses and supplies of food and other useful items flowing back Cooperating with them was a Dutch detachment which had followed them and had taken up positions at Ossu in the centre of the island to hold that section of the road as long as possible against any Japanese southward movement.

With Doig and the Dutch group thus forming their extreme right the Australians, in early October, set about reorganising their positions. Left of Doig, in the main right-flank positions—in the Laclubar area, northeast of Maubisse—were Laidlaw’s platoon, and Captain O’Connor’s28 of the 2/4th, watching the north coast road and Dili; Boyland’s platoon was South-west of these, east of Maubisse round Mindelo; Dexter was at Same; Turton was between Same and Ainaro, overlooking Maubisse from the South-west; Thompson was at Ainaro with his 2/4th platoon; Lieutenant Murphy’s29 “A” Platoon of the 2/4th was based on the Lete–Foho

area and, from an observation post west of Dili, covering the sea approaches to Dili from the direction by which most of the Japanese shipping was routed in.

October saw vigorous action against Japanese parties, particularly by O’Connor’s fresh troops who chopped hard at Japanese moving east of Dili. Corporal Haire30 of the 2/2nd Independent Company, who opened coolly on an enemy party moving from Laclo towards Dili on the 28th, estimated that his men shot down about 25 of them, and turned the Japanese back on their tracks. A section of newcomers under Lieutenant Dower,31 manning an observation post overlooking Dili from the east, were bombed from the air and beaten at from the ground after the Japanese located them, but, learning quickly the lessons the old hands had to teach them, dourly reoccupied their old positions as soon as the pressure eased. Nevertheless the month was chiefly remarkable for Japanese-fomented disorders among the native population, and the necessity for meeting this ever-worsening situation limited the action which the Australians could take against the Japanese themselves.

The Japanese exploited the natives skilfully. Parties of 50 or 60 natives would press against the Australians, usually urged on by a few Japanese in the rear. Almost daily Australian groups would report conflict with such bands resulting in the shooting of 10, 20 or 30 natives and possibly one or two Japanese. But the invaders were now not only concerned with stirring up the natives against the Australians; they were aiming also to destroy completely the Portuguese control.32 In Aileu they incited attacks on the residence of the District Officer at the beginning of October and, in these, ten Portuguese, including a woman, were killed. In November the District Officer at Manatuto and his secretary were similarly killed and, soon afterwards, the Portuguese official at Fuiloro was murdered. Meanwhile, however, the Japanese had evolved a “neutral zone” idea and ordered all Portuguese to assemble in a specified area west of Dili by 15th November. After that date, they said, all Portuguese within that area would be protected by the Japanese; those outside would be treated as active helpers of the Australians. This proposal inevitably represented a crisis to many of the Portuguese. In the second half of October Callinan (accompanied by Private McCabe33 who was fluent in Portuguese and the principal native language and was a brave and skilful scout) moved across from his headquarters at Ailalec to Hatu–Lia to meet a gathering of 12 or 15 Portuguese men and discuss the position. The Portuguese said that they wanted the government in Lisbon to know the plight of

the colony; that they wanted protection for their women.34 and children and arms with which to protect themselves; that, if their women and children could be moved to a safe place, they themselves would fight with the Australians. Callinan said that the only way to ensure the safety of the women and children would be to remove them to Australia but that, though he would explain their position to Australia, it would be most difficult to arrange this; that he would like the officials to remain at their posts and do all they could to maintain order among the natives. He said also that he had already asked Australia for certain arms to issue to the Portuguese and was hopeful that these would arrive soon; he would then issue them to the officials and order the Australian patrols to work in conjunction with them. After further discussion he then set out on his return journey.

When he arrived at Ainaro he found a willing fight going on—near-by villages burning, hostile natives from Maubisse being driven back up the valley by Australian fire, natives loyal to the Australians armed with bows and arrows and spears yelling wildly as they tried to get close enough to the raiders to use their primitive weapons. He found there also a message from Australia ordering him to suspend all offers to arm either Portuguese or natives pending further instructions. On 1st November, however, the arming of local inhabitants for guerrilla operations against the Japanese was approved.

By this time it was becoming clear that the men of the 2/2nd Company were almost at the limit of their endurance. They had been in action for nine months under conditions of great mental and physical hardship; their food had never represented a balanced and sustaining diet; malaria had wasted them; dysentery was chronic and widespread; they had suffered some 26 casualties since the Japanese invasion began. On 10th November Spence signalled Northern Territory Force Headquarters that one Independent Company was sufficient to carry out the tasks which had been allotted on Timor; one company was all that could adequately be maintained; the 2/2nd urgently needed relief. On 24th November Land Headquarters approved the relief of the company and the evacuation at the same time of 150 Portuguese.

During November, however, the general situation had improved in one respect at least—Allied bombing attacks on Dili and other key-points became more widespread and effective after the arrival at Darwin for a brief period of American Marauder bombers, and, a little later, Australian Beaufighters, to supplement the few gallant Hudsons on which the men on Timor had been so dependent for air support. On 3rd November the guerrillas watched four Marauders cross the island to attack Dili. The men at the combined company headquarters found that one of their wireless sets was netted in on the same frequency as that being used by the American airmen. As the aircraft turned to make for Darwin the

listeners on the ground heard one of the pilots report “Port prop hit by flak!” He began to lag and his leader urged him “Come on, Hitchcock, make formation”. Then the soldiers heard him report that there were Zeros on his tail and they saw three fighters close on him from different angles. The other three bombers came roaring down to help him. Then friends and foes alike, still fighting, disappeared into the skies to the south. That night the worried soldiers sent off a message to Darwin asking about Hitchcock. They had no reply. Next morning the Americans were over again. Laidlaw broke into their conversation asking “Did Hitchcock make it?” They were too busy to reply to him but that night a message came through from the American commander at Darwin:

Thanks Diggers, Hitchcock made it. Stop. Crash-landed Bathurst Island.

Of this incident Callinan wrote later:

These brief and personal contacts with the outside world affected us strangely and deeply; we had become accustomed to being engrossed in our own pressing problems and troubles, and to being self-dependent, so that when we experienced a close personal relationship with others, emotions were aroused which had been long suppressed. Hitchcock and his fight were discussed up and down our line, and we were bitterly disappointed when a few days later Darwin told us that the ... bombers had been withdrawn suddenly to meet an emergency on the east coast of Australia.35

Soon after, however, the soldiers learned that a squadron of Beau-fighters had arrived at Darwin, and, heavily armed, would be crossing to Timor on strafing missions. They proved most effective especially against Japanese vehicles moving along the roads in the eastern end of the island.

As from 11th November Callinan took over command of the whole of Sparrow Force, with Baldwin, unfailingly loyal and efficient, as his staff captain, and soon afterwards Spence returned to Australia. Laidlaw succeeded to the 2/2nd Independent Company. By this time it was known that the Japanese were working hard to develop the eastern end of the island where they were building airstrips and laying down supply dumps; in the centre Maubisse festered as the main centre of hostility to the Australians; along the south coast the Japanese were slowly moving eastward and were beginning to consolidate in the Hatu–Udo area.

On 27th November Callinan was ordered to prepare for evacuation about 190 Dutch troops who had been fighting with the Australians since the Japanese invasion (a fresh though much smaller Dutch detachment from Australia was to relieve them), 150 Portuguese who were seeking refuge in Australia, and the 2/2nd Independent Company. The Dutch and Portuguese were to go out first. Callinan felt that their embarkation from the island would present comparatively few problems as he would have the 2/2nd available to protect the beach-head. The embarkation of the latter would be more difficult, however, as he could not draw the 2/4th in sufficiently to cover them as they moved.

The arrangement was that Kuru and two corvettes Armidale and Castlemaine would run in to Betano on the night 30th November–1st December, lift the Dutch (leaving the fresh detachment) and the Portuguese and then return to embark the Australians on the night 4th–5th December. With the darkness of 30th November there were signal fires burning on the coast to guide in the promised ships. But only the Kuru arrived. The captain told Laidlaw (who was supervising the embarkation) that he did not know where the corvettes were but had intercepted a message from one of them saying that she was being bombed. He waited until the appointed time for departure and then set sail with over 70 Portuguese (chiefly women and children) on board his tiny craft. When daylight came Japanese aircraft attacked his ship heavily. The ship survived, however, and met the two corvettes, which had been delayed by determined attacks from the air and the reported presence of Japanese cruisers off the south coast so that they had arrived late off Betano and, finding no signal fires there, had put out to sea again. The Kuru transferred her refugees to the Castlemaine. That ship then set course for Darwin while the Kuru and Armidale (the latter carrying the Dutch replacement troops) turned back for Timor. But Japanese aircraft prevented their landfall and sank the Armidale. Callinan and his men, however, knew nothing of this loss until they were instructed from Darwin that the later phases of the evacuation would be delayed. This meant that they had hastily to rearrange their plans for covering the embarkation: Murphy’s platoon was to become responsible for the Mindelo area; Thompson’s was to cover the Same–Ainaro region; O’Connor’s men were to remain east of Dili and continue their observations there, centred on Fatu Maquerec.

The Dutch destroyer Tjerk Hiddes was to lift the first flight of the 2/2nd Independent Company (“D” Platoon, Lieutenant Doig now commanding, and the hospital patients) on the night 11th–12th December, together with the Dutch troops and some Portuguese. On the 10th Doig handed over to Thompson and concentrated his men at Same preparatory to moving down to Betano. On the morning of the 10th, however, Japanese suddenly sortied against his rearguard and a pack train (escorted by three soldiers) carrying rifles and supplies to a small group of Thompson’s men who were organising, training and arming friendly natives in the Ainaro area. The pack train party fought their way out but had to abandon the rifles and supplies. Of the rearguard Sapper Moule36 was killed and Sapper Sagar37 wounded. Doig, however, managed to get the rest of his platoon (except for Sapper Dennis,38 who, though he could have made good his own escape, stayed to help Sagar) through to the embarkation point. Callinan had hastily changed this point to the mouth of the Qualan River—about five hours’ walk from Same—because the Japanese in Same were

uncomfortably close to Betano. The embarkation went smoothly and before dawn the first flight was on its way back to Australia.

Laidlaw then had his own old platoon (now commanded by Nisbet) deployed east of Alas and disposed his two remaining platoons to observe and cover the outlets from Same. The second and last phase of the evacuation was set for the night 15th–16th December. On the 15th, however, the Japanese moved out of Same to Alas where they arrived about 11 a.m. They then struck down towards Betano round which (and Fatu–Cuac just to the Northeast) the remainder of the 2/2nd (except for Nisbet’s platoon) were then centred. This move suited Laidlaw quite well as he could slip his party eastward to the Qualan River when night came, sufficiently far ahead of the Japanese to complete their embarkation unhindered. The invaders, however, were not confident. As they approached Fatu–Cuac where Laidlaw had his own headquarters, Laidlaw and his men fired into them and then went off ahead of them. The Japanese entered Fatu–Cuac but then turned and set off back to Same again. The departing Australians, and 24 Portuguese, were thus able to board the Tjerk Hiddes unhindered and, before midnight, were on their way home.

Alone of the original Sparrow Force Callinan and Baldwin remained on Timor. They had their headquarters with Walker at Ailalec They felt the absence of their old comrades deeply. Callinan gathered about him the creados who had served these men so faithfully. Most of them came from areas which the Japanese had now occupied and so could not return home. Each carried a note from his former master which Callinan read.

In many cases it did not require the surat [note] to tell me that Mau Bessi, Antonio, Bera Dasi, or whatever his name, was “a good boong—treat him well, he deserves it”. Their feats of loyalty and courage were well known. This one had stayed with his wounded master whilst Japanese were searching surrounding villages, and moved him out just before the Japanese came to that village. This one had taken a message through the Japanese lines to a section cut off by a rapid enemy move. This one had been captured by the Japanese but had refused to give information of our moves, and had escaped by biting his way through his ropes when they were not watching. This one, while carrying mail and secret messages, had run into a Japanese patrol; he had quickly thrown the bag into the bushes and gone on unarmed to meet the Japanese, and by sheer effrontery had talked his way out of trouble. He had then made a detour back to where he had thrown the bag, which he recovered and delivered.39

After the departure of the 2/2nd Independent Company the wide sweeps of the Japanese caused Callinan and Walker to reconsider their position. Soon after the affray at Same Japanese attacks forced some of Murphy’s troops out of their positions on the Maubisse–Same road and the invaders’ movements seemed likely to cut Thompson’s platoon off from the main force. About the same time attacks were jeopardising O’Connor’s positions farther to the north. Walker then defined a basic area which he considered it necessary for his men to hold if they were to survive and continue fighting as a force, though, if this were lost, he thought they might continue the fight as small groups and individuals farther to the

east. This area was generally that within an arc sweeping northwards from Alas, through Fai Nia, to Laclubar and thence east to Lacluta. Accordingly Thompson’s platoon (less the Ainaro detachment which was completely pocketed by Japanese and hostile natives) was based on Alas; Murphy’s was based on Fai Nia; O’Connor’s men were based on Fatu Maquerec (with one section still manning the observation post which looked into Dili from a point Northeast of Remexio).

The Japanese and hostile natives were quickly becoming more active, however, and their activities more widespread. Scarcely a day passed that the wide-ranging Australian patrols were not skirmishing with them. Callinan told Australia that arming the natives who seemed to be friendly was a danger which might ultimately destroy the guerrillas themselves but was nevertheless the only course which offered them a chance of retaining their vital areas. He redoubled his efforts therefore to organise and train native auxiliaries. But the Australian position worsened quickly. Japanese pressure from the west was driving natives eastward from burnt and plundered areas; Japanese, and pro-Japanese natives, followed, burning, looting, wrecking and setting up a cumulative strain on the food resources in the east; O’Connor’s men were forced out of their observation area east of Dili; unrest grew to such an extent that natives would not move outside their own local areas and this, in turn, stopped the interchange of native information which had always been the Australians’ great source of Intelligence; soon the guerrillas had virtually no information of any value to send back to Australia. In addition to their other worries Callinan and Baldwin found more and more of their time being taken up with native administration. The conditions of anarchy which had developed left the natives in the Australian area with no central authority, so they turned to the Australian leaders for directions and for the settlement of their disputes.

Meanwhile the army leaders in Australia had become increasingly concerned with the position of Lancer Force (the new code name given to the troops on Timor in November), which they could well interpret from the detailed reports they were receiving. They had no immediate intention of attempting to retake Timor although, late in December, at the request of the Advisory War Council, the Australian Chiefs of Staff had prepared a study of the strategical importance of Timor in relation to Australian defence and an estimate of the forces that would be required to capture and hold the island. They believed that there then were approximately 12,000 Japanese troops on Timor, disposed more or less equally between the Dutch and Portuguese areas; that its capture and retention would involve the use of strong naval and air forces and three divisions with additional non-divisional troops. They stated, however, that they could not make any recommendations to the War Council regarding the advisability or otherwise of embarking upon any operations concerning the capture of Timor, because neither information regarding the enemy forces likely to be available for concentration against the Allies, nor information regarding the Allied resources likely to be available for use, was held by them; and because they considered that General MacArthur’s advice was

essential before the Australian Government could consider the matter further.

Blamey was incensed that the Advisory War Council should have followed the matter as far as they did without consulting MacArthur—so incensed that, on a copy of the terms of reference which they had given the Chiefs of Staff, he wrote:

Many years of training have produced in me a dislike for profanity in writing. This alone prevents me from giving my complete opinion on this imbecility.

This followed a fruitless request he had made in a letter from New Guinea to the Secretary of the Defence Department on 19th December, when he first learned of the Advisory War Council’s proposals, that the Prime Minister should approach MacArthur before he allowed the matter to proceed any further. In that letter he wrote also:

As a matter of simple fact an operation against Timor is in the immediate future completely out of the question. We are involved in a campaign in this region against the Jap which will absorb all our resources, both Australian and American, for many months to come. The Jap does not intend to be driven out of these areas. He has recently elevated this command into that of an Army Group and divided the Guadalcanal and New Guinea areas into two separate Army Commands He intends to hold on to the Buna area and reinforce it if possible. I hope we will capture it by the extermination of his force, but he has already shown signs of establishing himself on a further line extending from northern New Guinea to Rabaul.

I have no hesitation in saying that the preparation of a scheme for the capture of Timor, is, at the present juncture, a pure waste of time. Firstly, because we cannot disengage ourselves from the present area of operations, and secondly, we cannot spare resources to open up another.40

It was not merely the precarious position of the little force on Timor, therefore, but also the lack of any sufficiently important purpose in holding the positions there, which led to a decision on 3rd January 1943, to bring the 2/4th Independent Company back to Australia.41 Warning of this proposal was sent to Callinan next day. But he was then asked also if a small party (perhaps ten) could be left behind to collect and send information. He advised against this but volunteered to remain himself and organise native resistance (though he suggested that such a course would only be of value if some attack in force from Australia were contemplated for the near future). On the night of the 5th–6th January he was ordered to concentrate his force for evacuation on the night 9th–10th, at an embarkation point to be nominated by him. Since the Japanese had long since occupied Betano and were moving slowly east along the coast from that point, and were also closing in westward, there was little

choice in respect of this embarkation point. Callinan nominated Quicras, though about the only point in its favour was that it was almost equidistant between the Japanese eastern and western south coast positions.

The Australians had little time in which to plan their movement and gather in their widely-flung parties. There was no one to cover their movement so they would be extremely vulnerable as they began to move in and gather at Quicras. They therefore not only took elaborate precautions against any premature news of their proposed departure leaking out but also set in train clever deception measures. Everything went smoothly except that there was no word from the detachment at Ainaro. As his plans matured Callinan had time to ponder the wider implications of the departure of his force. He regretted that all the effort of the long period from February 1942 to January 1943 should now apparently come to nothing. He sent off a message volunteering to remain at the head of a small and desperate band of 15 or 20 men. (Baldwin saw the message go out, and formally asked to be allowed to remain as a member of this band.) But General Stevens replied to Callinan that, though he had sent the offer on to Army Headquarters, he had recommended that it be not accepted. Nevertheless, an instruction came through early in the morning of the 9th that one lieutenant and 20 men would remain. Major Callinan was ordered not to be of the party.

On the morning of the 9th the force (now concentrated except for the Ainaro detachment from whom there was still no word) set out with 50 Portuguese (all they could take of over 100 who had asked to go with them) on the last stage of their journey—over open grass country. It was raining heavily. The rivers between them and Quicras might flood and block them. They had to hurry. Soon after they started a Zero fighter suddenly appeared about 1,000 feet above them. They were afraid it would pick them up but the pilot apparently noticed nothing. The afternoon march led through swamps, often up to a man’s chest. The going beneath the surface was slippery with mud and twisted mangrove roots. But by 5 p.m. the whole party was in the bush which fringed the beach. Exactly at midnight recognition lights from the sea answered the signal fires. The surf was heavy. Boats sent inshore from a destroyer—the Arunta—were swamped. Time was running out. A few strong swimmers swam out beyond the broken water but reported this manifestly too difficult for most. At last, however, through great efforts, the whole group was ferried on board. The sailors were very kind to them. Most of the soldiers were so tired they slept almost all the way to Darwin.

On the island Lieutenant Flood42 remained in command of the volunteers of “S” Force—the party which was to continue to observe and report Japanese activities. With him were Corporal Ellwood,43 Signalmen Wynne44

and Key45 (both of whom had previously been in the observation posts overlooking Dili), Corporals Hayes46 and Ritchie,47 Lance-Corporal Hubbard48 and Privates Whelan,49 Duncan,50 Fitness,51 Hansen,52 Jacobson53 and Phillips.54 Just after the departure of the Arunta Private Miller55 joined them. He had been cut off from one of O’Connor’s patrols and had been unable to get through in time to catch the ship.

Flood set up his headquarters at Fatu–Berliu. The Japanese had not yet penetrated that area, the natives were friendly and food was plentiful. Soon after their arrival there Flood’s party was joined by Corporal Wilkins,56 Signaller Fraser57 and Private Finch58—from Ainaro. They had fought their way out of the Ainaro pocket, but were too late to join the evacuation. Private Howell59 had also been with them but had been killed on the way out. These brave soldiers were tired and sick but their courage was still high.

Soon, however, Japanese patrols also found Flood’s party. As they closed in the Australians engaged them but were quickly outflanked and had to fall back, fighting as they went. The pony carrying much of their wireless equipment bolted and so, when they re-established themselves again, they were out of touch with Darwin. But they improvised another set and by 20th January were once more in communication. The Japanese, however, were determined to get them and that same day two strong parties closed on them. There was a vigorous fight with fire being exchanged from a distance of only about 50 yards. The Japanese hunted the little band all day and dispersed them. The pony carrying the wireless was shot while crossing a stream. The swift water carried it away with the wireless still attached to it. The various little Australian groups then struck

South-east through rain and swamp, out of touch with one another and with Australia. They were in strange country. Food was very scarce. Many of the men became sick. The Japanese hunted them continually with aeroplanes and ground patrols. Gradually, however, the groups began to come together again, as they got news of one another from Portuguese and natives, and began to link with a “Z” Special Unit group which had been operating in the eastern end of the island.

“Z” Special was a small unit of the Australian Army of a highly “secret” nature. It was responsible for special operations of various kinds and special Intelligence tasks, often within enemy occupied territory. About the middle of 1942 two officers of this unit (one of them Captain Broadhurst,60 formerly of the Malayan Police) had arrived in Portuguese Timor to plan operations at the eastern end of the island. They had gone first to de Sousa Santos for information, advice and letters of introduction. Soon afterwards they returned to Darwin on the Kuru and, in September, Broadhurst and a small party were landed in the eastern area where they established themselves firmly and began organising the natives there to resist the Japanese.61 Like Flood’s party they were now being vigorously hunted by the Japanese and indeed, on 18th January, had signalled Darwin that their headquarters were surrounded and saying “We are finished”, and asked to be taken off. On the 30th they signalled that they had joined up with “7 survivors of Lancer, no wireless”. (Their wireless was transmitting but not receiving and thus they had no way of knowing whether or not their messages were getting through.) Hudsons dropped food and wireless sets to them.

On 10th February the combined “Z”-Lancer group were waiting near the mouth of the Dilor River (some 20 miles east of Quicras) with a white cloth hung out as a signal to a submarine, the USS Gudgeon, which was lying off shore. When darkness came the submarine surfaced and exchanged recognition signals with the soldiers. The Americans took the Australians aboard in rubber boats through a heavy surf. They gave them clothes and plenty of good food and their own beds and took them to Fremantle.

Thus the Australian operations on Timor ended in only a few days less than a year from the date on which they had begun. They had no positive strategical value, except that perhaps they diverted a measure of Japanese attention at a critical time and perhaps, in part, led to a buildup of Japanese forces on Timor during 1942 in anticipation of possible Allied attempts to reoccupy the island. They did, however, result in the destruction of some hundreds (at least) of Japanese soldiers at very small cost. But most importantly, possibly, they demonstrated how an apparently

lost cause could be revived by brave men and transformed into a fighting cause, and at a time when such a demonstration was of the greatest value to many of their fellow Australians.

Their tactics and the results they achieved (both in relation to the losses they inflicted and the small losses they themselves sustained) can be judged neither by the standards of regular open warfare nor by those of the bush warfare which developed in New Guinea. They were organised and trained for guerrilla warfare and the circumstances in which they found themselves permitted them to (indeed demanded that they should) operate as they were organised and trained to do. The country could supply them; there was a friendly population to assist them; there was rugged country to aid them, conceal them, and hinder regular operations against them—but, at the same time, it was not the rain forest country of New Guinea which demanded (even of ambushes) that the attacker and the attacked come to such close quarters that a fierce give and take in fighting was often inevitable; it was bush country of the Australian type which permitted long-range ambushes and a clean getaway. The pattern of warfare developed by the Australians on Timor perhaps more closely paralleled that developed by the Boers than any other (and two of the young Australian leaders at least—Baldwin and Dexter, both scholars as well as soldiers—were students and admirers of the Boers and had closely studied Reitz’ Commando). The Boers failed finally through exhaustion; because the country could no longer support them; because the friendly population had been swept out of the areas of their operations. When similar circumstances beset the Australians on Timor they had to get out—perhaps most of all because a large section of the local population was either no longer friendly or was actively hostile to them.