Chapter 1: Reinforcement of Australia

By early March 1942, the Japanese thrust had struck deep into the Pacific to the south and wide to the South-west. Along its southern axis the Filipino and American forces in the Philippines were isolated and wasting fast; after the fall of Rabaul on 23rd January the Japanese were on the move through the Australian Mandated Territory of New Guinea; Port Moresby was under aerial bombardment from 3rd February onwards; Japanese aircraft were questing southward over the Solomon Islands. Along the South-west axis the British had surrendered Singapore on 15th February and, by 7th March, had begun the retreat from Rangoon which was to carry them right out of Burma; a threat to India was developing; the Netherlands East Indies were rapidly being overrun; on the Australian mainland Darwin, Broome and Wyndham had been heavily raided from the air.

The Japanese armies thus controlled the area within an arc which embraced the Western Pacific, passed through the Solomons and New Guinea and south of the Indies to Burma. This arc pressed down almost upon Australia whose nearest friendly neighbours on either side were now disadvantageously placed: the United States, separated by some 3,000 miles of ocean, was weaker than Japan on sea, on land and in the air; India, which had sent its best formations to the Middle East and Iraq, had lost some in Malaya, and had others fighting in Burma, was now garrisoned mainly by raw divisions.

In Australia itself some military leaders had long foreseen this very situation. But now, of four experienced divisions of volunteers of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), one had been lost in Malaya and in the islands north of Australia and the other three, which had been serving in the Middle East, were still overseas. The absence of these elite troops at a critical time in Australia had also been foreseen and the “calculated risk” accepted, because it was by no means certain when they went abroad that, if Australia itself were threatened with invasion, the situation in other theatres would permit of their recall. Even if it would, the return of such an army could not be accomplished for some months after the necessity first became apparent. Consequently preparations for the local defence of Australia had had to be based substantially on plans for the use of the home army.

By the end of June 1940 (when, with France falling, enlistments in the AIF vastly increased) the militia, a force comparable with the British Territorial Army or the American National Guard, had dwindled in numbers to 60,500, although its authorised strength was 75,000 to 80,000—a decline in which the greatest single factor had been enlistments for overseas service. The Government then decided to increase the militia’s strength by calling up more men as defined in Class 1 of the Defence Act—unmarried

men and widowers without children, between the ages of 18 and 35. By July 1941, virtually all men in Class 1 had become liable for service and by the end of August the militia numbered 173,000. Of these, however, only 45,000 were serving full time. As the call-ups continued it became clear that, apart from voluntary enlistment for overseas service, the two most important factors reducing the numbers available to the militia were the system of exempting men engaged in “essential” industry or giving them seasonal leave (which affected nearly 30 per cent of all men liable for service in Class 1), and medical unfitness, either temporary or permanent, which debarred nearly 14 per cent of the class from service.

But lack of continuity in the training of such forces as could be gathered together was also a handicap. When war with Germany began, first one month’s, then three months’ additional training had been ordered. Later the 1940–41 policy provided that serving and potential officers and non-commissioned officers should be intensively trained for 18 to 24 days as a preliminary to a camp period of 70 days, that militiamen (other than these) who had completed 90 days’ training in 1939–40 should undergo 12 days’ special collective training, and that the rest of the militia should carry out 70 days’ training. A further complication was added in July 1941, when “trained soldiers” (those who had already undergone 90 days’ training) and recruits became liable for three months’ and six months’ training respectively in each year. The fragmentary nature of the training was thus an important factor in preventing a high general standard of efficiency being achieved. Each unit, however, had a nucleus of key men serving full time and, when the War Cabinet approved the six months’ recruit training system, it also approved proposals for the enlargement and more intensive training of these groups—that officers, warrant and non-commissioned officers, specialists and essential administrative personnel, not exceeding 25 per cent of the strength of each unit, should form a training and administrative cadre and, when the unit itself was not in camp, should undergo special training.

There were other impediments to efficiency. The most energetic and capable of the younger officers had gone to the AIF. The senior appointments were filled by officers who had seen hard service in the war of 1914–18 and there were many such veterans in the middle ranks. These strove to maintain efficiency and keenness, but suffered many handicaps, including a serious shortage of equipment of all kinds—even rifles, of which large numbers had been sent to England in 1940.

While it was the largest and most important part of the army in Australia, the militia did not, however, constitute the whole of it. At the end of August 1941, the Permanent Military Forces in Australia numbered 5,025; there were 12,915 in garrison battalions, and 43,720 in the Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC). The formation of an Australian Women’s Army Service (AWAS) had been approved on 13th August.

The garrison battalions, filled mostly by old soldiers of the previous war, had their origin in the “War Book”1 plans for mobilisation, which had

provided for the raising of battalions for the local protection of the coast defences—“ten garrison battalions to relieve ten battalions of the field army allotted to the local protection of the forts”. A further impulse toward this end had come from the Returned Soldiers’ League through a resolution passed at its Twenty-Second Annual Congress at Hobart in November 1937. It stated that “Congress deems it necessary that a national volunteer force be raised from ex-servicemen and others between the ages of 41 and 60 years for local defence and to relieve existing forces from certain necessary duties in the event of a national emergency”.2

During the crisis in France the Federal Executive of the League, on 31st May 1940, followed this resolution with a declaration “that a Commonwealth-wide organisation of ex-servicemen for home defence purposes be established and that a scheme with that object be framed forthwith”.3 The Government agreed and decided to form an Australian Army Reserve on the general lines which the League had envisaged. Class “A” was to include volunteers up to 48 years of age, medically “fit for active service” and not in reserved occupations, who would be prepared to be posted to militia units and undergo the normal training prescribed for those units. Class “B” was to include volunteers not eligible for Class “A” and to be divided into two groups—Garrison Battalions’ Reserve and the RSL Volunteer Defence Corps. The garrison reserve would enlist for the duration of the war while the VDC was “to be organised by the RSS & AILA on flexible establishments approved by Army Headquarters and should carry out such voluntary training as can be mutually arranged between GOCs and State branches of the League in association with the existing area organisation”.4 So the formation of the VDC began on 15th July 1940.5

But at first the VDC had little more to sustain it than the enthusiasm of its own members since the army was preoccupied with training and equipping the AIF and the militia, and little material could be spared for the new corps. By the end of 1940 the VDC numbered 13,120 and two considerations were becoming obvious: first that the Government would have to revise in some measure its stated intention of not accepting any financial responsibility for this voluntary, part-time, unpaid organisation (except that involved in arming, and later, clothing it); and second that it must be brought more directly under the control of the army. In February 1941, therefore, the War Cabinet approved the expenditure of £157,000 on uniforms for the corps, following that in May with a vote of a further £25,000 for general administrative expenses. In May also the Military Board assumed control, foreseeing that roles of the VDC would

be to act as a guerrilla force, to engage in local defence, and to give timely warning to mobile formations of the approach of enemy forces.

Both the VDC and the AWAS were symbols of a growing urgency in the war situation—the former through the spontaneity of its growth; the latter through the emphasis it placed on the increasing shortage of man-power.6 The formation of an Australian Women’s Army Service would release men from certain military duties for employment with fighting units. No members of the Women’s Service were to be sent overseas with-out the approval of the War Cabinet. It was to be some months, however, before recruitment was under way, even on a limited scale, and before plans for the training of the AWAS began to be systematised.

It was to weld together this partly-equipped (by the standards of modern war) and partly-trained force, that, in August 1941, Major-General Sir Iven Mackay7 had been recalled from command of the 6th Division in the Middle East to become General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Home Forces. As far back as 1937 Major-General J. D. Lavarack, then Chief of the General Staff, had proposed that, in the event of a crisis, a Commander-in-Chief should be appointed. At the Imperial Conference that year, however, the War Office and the Air Ministry had expressed the view that Service Boards should continue to function in an emergency provided that sole responsibility for the direction of operations was vested in a Chief of Staff. These views had been recalled by the War Cabinet in its discussions in May 1941 of a proposal by the Minister for the Army, Mr Spender, to appoint Lieut-General V. A. H. Sturdee as Commander-in-Chief with Major-General J. Northcott as Chief of the General Staff. Convinced, apparently, by the argument that the Military Board system was necessary to coordinate the control and administration of the AIF in the Middle East, the Far East and Australia, and the militia and kindred organisations at home, Spender at length modified his recommendations and proposed the appointment of a GOC-in-Chief of the Field Army in Australia. This the War Cabinet had approved in principle. In June the Minister for the Army had further explained that he considered such an appointment necessary because the weight of administrative work prevented the Chief of the General Staff from adequately controlling training and preparation for war. He urged the appointment of an officer concerned only with preparations of the army for war to ensure the single control and direction of military operations, as being psychologically more satisfactory to the people of Australia. Discussion revolved round the points that, if the Military Board was to continue to function under a GOC-in-Chief, with considerable delegations, the situation would virtually revert to the one then existing; if matters had necessarily to be referred to the GOC-in-Chief, with the Military Board still in existence, it would make

for centralisation and congestion. A final decision had again been deferred to allow the Minister for the Army to consider these points. On 11th July, however, the War Cabinet directed that a GOC-in-Chief, Home Forces, should be appointed; he would be superior to the General Officers Commanding in the regional Commands for the direction of operations, equal in rank to the Chief of the General Staff, but subordinate to the Military Board which would remain the body to advise the Minister for the Army and, through him, the War Cabinet. The question of the authority to be delegated to the Home Forces commander by the Military Board was left to be decided later. The appointment of General Mackay was then confirmed on 5th August 1941.

If Mackay had been in any way deceived by the grandiloquence of his new title his illusions were soon dissipated when he assumed command on 1st September. Initially there was reluctance to grant him the substantive promotion he had been promised. He found, too, that his authority did not extend over the forward areas of New Guinea and the Northern Territory; nor was he to be responsible for “the defence of Australia” as such, as this responsibility remained with General Sturdee, the Chief of the General Staff. In short his command was far more circumscribed than he might have expected, with the added disadvantage of calling for a political finesse to the possession of which he laid few claims. He was a gallant and successful soldier, with a long record of distinguished service to his country, and a man of instinctive and unassuming courtesy. But neither his qualities of character and temperament nor the academic seclusion of his life between the wars fitted him well for the role of a senior military adviser to a Cabinet inexperienced in military affairs.

If the terms of Mackay’s appointment were unsatisfactory to himself they were equally so to General Sturdee who, while he agreed in principle with the appointment, disagreed with the way in which the principle had been carried out. Mackay was junior to him in the Army List and, in fact, if not in the terms of his appointment, Sturdee’s subordinate. But Mackay had the right of direct access to the Minister. It was only because of the forbearance of the two generals that the arrangement worked as well as it did.

From the beginning, therefore, the appointment of the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Home Forces, was an unsatisfactory compromise which pleased none of those most immediately concerned and, if only for that reason, could not produce the best results. That it did little to provide the psychological balm which Mr Spender had hoped for was suggested in a blunt statement by The Sydney Morning Herald:

The Government has appointed a Commander-in-Chief in Australia, but that is not sufficient unless he has the authority proper to that position. It may be that his functions and those of the Chief of Staff at Army Headquarters have been precisely and correctly defined and can lead to no conflict between them; but if so the public is not aware of it.8

It was in these circumstances that Mackay turned to his task. In his planning he was bound to accept the existing doctrine that there were certain areas vital to the continuance of the economic life of Australia which must be held and to be guided by the arrangements designed to give effect to that doctrine. Military thinking had long been based on the premises that “an invading force . .. will endeavour to bring our main forces to battle and defeat them. The most certain way to do this will be to attack us at a point which we must defend. The objective of an invading force therefore will probably be some locality in which our interests are such that the enemy will feel sure that we shall be particularly sensitive to attack. Thus the geographical objective of land invasion would be some compact, vulnerable area, the resources of which are necessary to the economic life of Australia.”9 So the problems of the defence of the Newcastle–Sydney–Port Kembla area to which the above conditions plainly applied, became the paramount ones in Australian defence thinking. That area contained almost a quarter of the Australian population, the chief commercial ports, the only naval repair establishments in the country, and the largest industrial plants; these were dependent upon the large coal deposits which the area contained.

Accordingly the Army staff had then decided that “the plan for the concentration of Australian land forces to resist invasion must therefore provide first of all for the initial defence of these vital areas and for the concentration of the main force to deal with the enemy’s main attack as quickly as possible after its direction becomes definitely known. The plan must then provide for the security of other important areas which might, if entirely denuded of mobile land forces, be attacked by minor enemy forces with far-reaching effect.”10 In broad outline the following were seen to be the requirements of the plan of concentration for the land defence of Australia:

(a) Provision for the initial defence of the Sydney–Newcastle areas.

(b) Provision for the concentration as quickly as possible of the main army to deal with the enemy’s main attack.

(c) Provision for the defence of other areas regarded as sufficiently important.

No part of this planning meant that there would be a rush to concentrate in the areas likely to sustain the main enemy attack (i.e. the Sydney–Newcastle–Port Kembla areas) as soon as mobilisation began. This was simply the basic planning. The decision to undertake or defer concentration would be taken in the first weeks of the war in accordance with the movements and apparent intentions of the enemy. Planning, therefore, provided that “in the case in which a decision to defer concentration is taken, training will take place either at places of mobilisation or at places of preliminary concentration, or at both. ... If the order to move to the main area of concentration is deferred for a longer period than six weeks

after the completion of mobilisation, the assembly of formations for manoeuvre training in places of preliminary concentration should be undertaken.”11

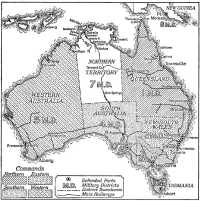

In accordance with this general outline Mackay was required to think in terms of the defence of his vital areas plus provision for the defence of Brisbane, Melbourne, Hobart, Adelaide, Fremantle and Albany. Nor, although they were outside the areas for which he was responsible, could his planning eliminate the needs of the Northern Territory and Papua–New Guinea, since any increase of strength there would reduce the force available to him. This force would consist basically of the 1st and 2nd Cavalry Divisions, the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th (Infantry) Divisions, with the components of a fifth division and corps troops. In addition fixed defences were provided at Thursday Island, Townsville, Brisbane, Newcastle, Sydney, Port Kembla, Port Phillip, Adelaide, Hobart, Fremantle,

Albany and Darwin, with coast guns which ranged from 4-inch to 9.2-inch in calibre. The major part of six divisions was marked for ultimate concentration in the Sydney–Newcastle–Port Kembla areas, but Mackay had to combat a feeling in the country at large that forces raised in an area were designed particularly for the defence of that area.

On 4th February 1942 Mackay produced and Sturdee “generally concurred in” a memorandum stating the principles mentioned above but extending the area of concentration to embrace Melbourne, and Brisbane where newly-arrived American detachments had established themselves..

Mackay wrote that the Melbourne–Brisbane region, 1,000 miles from north to south, had scarcely five divisions to defend it. He did not propose, therefore, while the main areas remained equally threatened, to attempt to defend either Tasmania or Townsville with more troops than were in those areas then. The troops then in north Queensland—a few battalions—should remain there for reasons of “morale and psychology”. He asked that the Government should either confirm his proposal not to reinforce Townsville or Tasmania or else give “some further direction regarding the degree of such defence”.

On paper the home forces of February 1942 appeared fairly formidable; in reality deficiencies in strength, training and particularly equipment were likely for some months to make them less powerful in the field than perhaps three well-trained, well-equipped divisions. In addition Mackay was well aware that he could not defend his main areas simply by clustering his forces round the immediate vicinity of those areas. Fully alive to the intrinsic importance of Brisbane and Melbourne he none the less considered them chiefly important as defining the flanks, or perhaps the front and rear, of his most vital areas so that, in effect, to carry out the task of protecting Newcastle–Sydney–Port Kembla, he had to think in terms of the vast area Brisbane–Melbourne.

Mr F. M. Forde, the Minister for the Army in the recently elected Labour Government, whose electorate was in north Queensland, recommended that the Cabinet decide to defend “the whole of the populated area of Australia.” This discussion was still in progress later in February when knowledge that the 6th and 7th Divisions were returning and that an American division had been allotted to Australia radically altered the situation.

The machinery for command and planning in Australia at this time had been strengthened. Mackay’s headquarters was established in Melbourne and provision had been made for movement into the field of the necessary sections if the “Strategic Concentration” planned were ordered. Throughout the country the system of area commands was still operating and it was planned that the General Officer Commanding, Eastern Command, would assume coordinating control in the main concentration area pending movement into the field of Army Headquarters. He would thus have the status of a corps commander and, as the basic planning provided for the creation of an army of two corps to replace Eastern Command in the main areas when concentration was ordered, he would be the commander

designate of the corps to be deployed in the Sydney–Port Kembla area.

In February 1941, War Cabinet had approved the establishment of certain important Intelligence and planning organisations. These were the Central War Room, to facilitate control of operations on the highest military plane through direct meetings between the Chiefs of Staff or their deputies; the Combined Operations Intelligence Centre with the function of making Intelligence appreciations on strategical questions for the Chiefs of Staff and collecting and assessing urgent Intelligence for distribution to the Services, to the Central War Room, to New Zealand and Singapore; Area Combined Headquarters located at Townsville, Melbourne, Fremantle and Darwin, to facilitate the cooperation of the navy and air force in trade defence in the focal areas; and Combined Defence Headquarters to coordinate the operations of the naval, military and air forces allotted for the defence of the areas which included a defended port. In addition certain purely planning organisations had been approved in September. Of these the most important, the Chiefs of Staffs Committee, was to be concerned with planning on the highest military level for the defence of Australia, and initial planning for that body was to be carried out by a Joint Planning Committee.

General Mackay, busy with constant travelling, inspecting and advising, did not at first add to this list by setting up a separate Home Defence Headquarters, but functioned through and from Army Headquarters. Unceasingly he attempted to drive home lessons that his experience in the Middle East had confirmed. Of the most important of these the first concerned the spirit which made an army, so he preached a doctrine of alertness, intensity in training, sacrifice and service. The second was that modern war demanded a high degree of physical efficiency and so he drove his forces to hard training. The third concerned mobility; he urged that the war in Australia would be one of swift movement; that attack might come from any direction, therefore defence should not be based only on strongpoints looking out to sea and the hope that the invaders would land at the required spot so that they could be mown down; that the army should be prepared to move at short notice and fight in any direction.

But Mackay could do little more than had been done before his arrival—and not least because of the inherent defects of the militia system itself. This system, however, should be judged against the background of the voluntary system on which it was superimposed; up to the beginning of December 1941, this had yielded 187,500 men to the AIF, and 59,700 men to the RAAF, while 20,900 men were serving in the Navy. These were volunteers for a war which was still remote from their own country and already they represented almost 4 per cent of the Australian population. In addition many volunteers were serving in the militia—men who had become suspicious of European quarrels, were unwilling to volunteer for unrestricted service, but ready to fight in defence of their homes.

Meanwhile, equipment which might have given militia training greater

effectiveness had been going overseas. Thus, in February 1941, the War Cabinet ruled that, in view of the deficiency of 39,588 serviceable rifles for the army and requirements of 40,000 and 4,500 respectively for the Volunteer Defence Corps and the air force, no more deliveries of rifles should be made for the present to the United Kingdom or other Empire countries (except New Zealand) or to the Netherlands East Indies. On the other hand, at the end of April 1941, the Chief of the General Staff, in view of the fact that Australia was not immediately threatened, told the War Cabinet that though the provision of an additional 1,179 Vickers machine-guns was necessary to complete the initial equipping and war wastage reserve of the Australian Military Forces, this was not of immediate urgency. The War Cabinet thereupon approved the dispatch of 25 guns a month to the Netherlands Indies and the equal division of the remaining guns coming from the factory (175 monthly) between air force and Indian orders with the proviso that 50 should go to the Free French forces in New Caledonia as soon as possible. On 11th June, it was pointed out that 53 field guns had already been sent to the Middle East and Malaya since the war began; Australia was below initial requirements and had no reserves. It was then decided that no additional field artillery should be permitted to leave Australia until 25-pounders were well into production, and no anti-tank guns beyond an allotment to the United Kingdom of 25 a month from July onwards should be spared.

The year 1941 saw a quickening of preparations for war. At the beginning of the year the Cabinet approved the formation of an armoured corps and the army began to raise and train the 1st Armoured Division, as a fifth division of the AIF. Although orders had been placed in the United States for 400 light tanks for initial training and equipment, Australia was pressing ahead with her own tank production program, hoping to have a first tank produced in November and 340 by August 1942. The anti-aircraft defences were being equipped by the Australian ordnance factories, forty-four 3.7-inch guns having been made available by the end of April, with a promised rate of production on army orders of eight a month. There was a generally increasing rate in the production of weapons and equipment of many different kinds. Orders were issued for the continuous manning of coastal and anti-aircraft defences. Additional troops were sent to Port Moresby and Darwin and a battalion group was sent to Rabaul. Australian-American cooperation in the construction of airfields in Northeast and Northwest Australia developed. A program of tactical road building was being pushed ahead: from Tennant Creek to Mount Isa; an all-weather road from Darwin to Adelaide River; a Port Augusta–Kalgoorlie road. Telephone communications with isolated areas were improved.

On 7th–8th December 1941 Japan attacked. The Army’s first official news of this came through the Combined Operations Intelligence Centre at 7 a.m. on 8th December with reports of the landings at Kota Bharu in Malaya. Cancellation of all leave followed, final preparations for mobilisation were made. At a War Cabinet meeting the same day General

Sturdee (who, about one week earlier, had asked the Prime Minister, Mr Curtin, for an additional 100,000 men) proposed that divisions in cadre forms be called up for training on a basis which included the actual fighting organisation but excluded the rearward services. No immediate action was taken on those proposals and Sturdee was asked to provide fuller information. This he did next day saying that, excluding reinforcements and certain maintenance units, the strength that he proposed for the militia at this stage was 246,000 men, of whom 132,000 were already on full-time duty. To allow time for further consideration, however, the War Cabinet decided immediately to recall to service only 25,000 militiamen and approved the recruitment of 1,600 more women for the Australian Women’s Army Service. On the 11th, it approved revised proposals by Sturdee that, as it had been found that only 132,000 men were on full-time duty, the Army would require immediately a further 114,000. This entailed calling up Classes 2 and 3—married men, or widowers, without children, between the ages of 35 and 45, and married men, or widowers with children, between the ages of 18 and 35. The Ministers noted that a further 53,000 would be required to complete the full scale of mobilisation including first reinforcements; and approved that 5,000 of the Volunteer Defence Corps should be called up for full-time duty on aerodrome defence and coastwatching—a curious development considering the essential nature of that corps.

The Chiefs of Staff had advised the War Cabinet on 8th December that the most probable Japanese actions were, in order of probability, attacks on the outlying island bases, which would take the form of attempts to occupy Rabaul, Port Moresby and New Caledonia on the scale, at each place, of one division assisted by strong naval and air forces; raids on or attempts to occupy Darwin—a strong possibility in the event of the capture of Singapore and the Netherlands East Indies; and naval and air attacks on the vital areas of the Australian mainland. They concluded that the defeat of the Allied naval forces, or the occupation of Singapore and the Netherlands Indies with a consequential establishment of bases to the Northwest of Australia, “would enable the Japanese to invade Australia”. Sturdee said that, to counter these probable moves, he would require forces of a minimum strength of a brigade group in each of the three areas Rabaul, Port Moresby and New Caledonia, and the better part of a division at Darwin.

Soon afterwards the War Cabinet considered the dispositions and strengths of the militia then actually in camp or on full-time duty. In Queensland 1,563 men were manning the fixed defences at Thursday Island, Townsville and Brisbane; the field army was 15,071 strong with the nucleus of one brigade in the Cairns–Townsville area, of one brigade in the Rockhampton–Maryborough area and, in the Brisbane area, of one cavalry brigade group and one infantry brigade group as a command reserve, and one battalion for local defence. One garrison battalion was on coast defence duties and two on internal security duties. The total “full-time and in camp” strength was 16,400.

In New South Wales, there were 3,900 on fortress duty at Port Stephens, Newcastle, Sydney and Port Kembla. The field army, including base and lines of communication units, numbered 34,600, with the 1st Cavalry Division (except for a brigade group on the coast south of Port Kembla) on the coast north of Port Stephens, the bulk of the 1st Division covering the Sydney–Port Kembla area, one brigade group of four battalions in the Newcastle area and the 2nd Division in the Sydney area as Command reserve. Garrison battalions, very much below strength, numbered 1,777 men. All of these, with various training and similar units, totalled 43,807.

In Victoria 46,500 men were in camp or on full-time duty: 2,120 were manning the fixed defences and 38,600 (including base troops) were in the field army, of which the 3rd Division was held as Army reserve; the 2nd Cavalry Division (containing only one brigade group of four regiments) and the 4th Division (of two brigades each of four battalions) were disposed as the Melbourne Covering Force together with certain non-divisional units which included some armoured and other AIF units. Two garrison battalions were on coast defence duty and one on internal security duties.

There were 10,810 troops in South Australia and 4,380 in Tasmania.

In remote Western Australia were 1,900 in its coastal forts, and one brigade group of four battalions, one light horse regiment and a machine-gun regiment in the field army which, with base troops, totalled 8,180. Four garrison battalions had a total of 1,150.

In the Northern Territory, excluding the 2/21st and 2/40th Battalion groups which had been ordered to the Netherlands East Indies immediately on the outbreak of war, were the 19th Battalion, and two AIF battalions—the 2/4th Machine Gun and the 2/4th Pioneer. Two militia battalions and an AIF Independent Company were moving north from South Australia. With base units the force totalled 6,670.

In the Mandated Territory of New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides, with the main strength (2/22nd Battalion group) in the Rabaul area, there were 2,158 troops including approximately 1,138 AIF. At Port Moresby, in the Territory of Papua, 1,088 men were stationed including some Papuans and some 30 AIF.

In addition to the troops thus deployed throughout Australia and the islands there were on the mainland on 8th December 31,900 of the AIF including about 2,800 men destined for employment in Ambon and Timor.

After the formal declaration of war on 9th December, the army moved swiftly to battle stations and the work of preparing defences. A tangled undergrowth of barbed wire sprang up over beaches many of which, until then, had been city playgrounds. Fields of fire were cleared. Guns were emplaced. Training was intensified. And the strength of the army increased daily. Proclamations calling up the later classes defined in the Defence Act began to take marked effect. From actual registration there were no exemptions. Enlistments in the AIF rose steeply as they had always done when the need and the opportunity to serve could be seen more clearly. The

monthly figure, which had fallen to 4,016 in October and 4,702 in November rose to 10,669 in December and 12,543 in January. These figures were by no means as spectacular as those of June of 1940 when over 48,000 men enlisted, one main cause being a War Cabinet decision that prevented members of the militia from enlisting in the AIF or RAAF. Women also offered in daily increasing numbers and the first recruits in New South Wales for the AWAS were interviewed on 26th December by female officers who had already been trained. On 1st January 1942 the first twenty-eight female recruits were formally enlisted. By 5th February enlistments in the AIF since its formation in 1939 totalled 211,706, and 222,459 were in the militia and other forces.

Before and soon after the outbreak of war with Japan a group of senior officers who had distinguished themselves in the Middle East were recalled to lead militia formations or fill important staff posts. On the day when General Mackay became GOC-in-Chief, Home Forces, Brigadier S. F. Rowell, formerly General Blamey’s chief of staff, became Deputy Chief of the General Staff with the rank of Major-general. On 12th December Major-General H. D. Wynter, who had been invalided home from Egypt, was appointed to Eastern Command, which embraced the vital east coast areas. Ten days later General Mackay established his own headquarters and to him, soon afterwards, went Major-General Vasey12 as his chief of staff. At the same time Brigadiers Clowes,13 Robertson,14 Plant,15 Murray16 and Savige17 were promoted and given Home Army commands: Clowes, an expert artilleryman, 50 years of age, who had commanded the Anzac Corps artillery in Greece, took over the 1st Division; Robertson, 47, the 1st Cavalry Division; Plant, 51, Western Command; Savige, 51, the 3rd Division; and Murray, 49, the Newcastle Covering Force.

In the period from December 1941 to March 1942, while these experienced and energetic leaders were rapidly building the Home Army to a new peak of strength and efficiency, American reinforcements were arriving and battle-hardened veterans of the AIF were on their way back from the Middle East.

The first Japanese blows at the Philippines had destroyed half the defending air forces and shown that the attackers were free not only to land there but to move southward with every chance of isolating the Philippines before American reinforcements could arrive. President Roosevelt and his military leaders, however, were agreed that they must accept the risks of trying to reinforce the islands while there was any chance of success and that the United States must not withdraw from the South-West Pacific. Logically then they decided to establish an advanced American military base in Australia and to keep open the Pacific line of communication. On 17th December General George C. Marshall (Chief of Staff of the United States Army) approved Brigadier-General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s plans for the establishment of this base which was, first of all, to be an air base and commanded by a senior Air officer (Lieut-General George H. Brett). But, though the forces to be sent to Australia were to be part of the United States Army Forces in the Far East, with the prime task of supplying the Philippines, almost at once “it was evident that the establishment of this new command implied a more comprehensive strategy in the Southwest Pacific than the desperate effort to prolong the defense of the Philippines”.18

On 22nd December 1941 four American ships (escorted by the American heavy cruiser, Pensacola) arrived at Brisbane. They carried some 4,500 men of field artillery units and the ground echelon of a heavy bomber group, munitions, motor vehicles, petrol and 60 aeroplanes; they had been on their way to the Philippines when the Japanese attacked and had then been re-routed from Fiji by way of Brisbane. They were being followed closely by four other ships carrying an additional 230 fighter aircraft. But by that time the isolation of the Philippines was nearly complete and, on 15th December, all that remained of the Philippines heavy bomber force—fourteen Flying Fortresses (B-17s)—were ordered south to the Netherlands Indies and Australia on the ground that there was insufficient fighter protection to enable them to operate from their own bases. It was then clear to President Roosevelt that the chance of reinforcing the Philippines had gone and he directed that the reinforcements then on their way should be used “in whatever manner might best serve the joint cause in the Far East”.

By this time the projected Australian base had become a major American commitment. “The immediate goal was to establish nine combat groups in the Southwest Pacific—two heavy and two medium bombardment groups, one light bombardment group, and four pursuit groups. ... This force represented the largest projected concentration of American air power outside the Western Hemisphere ... and a very substantial part of the fifty-four groups that the Army expected to have by the end of the winter.”19

On 23rd December the British Prime Minister, Mr Churchill, and President Roosevelt, with their Chiefs of Staff, began strategic and military

discussions in Washington. By the end of the first week of these discussions the British staff began to share something of the American concern regarding the northern and eastern approaches to Australia and New Zealand. As a result agreement was reached regarding the diversion of shipping necessary to permit reinforcement of the South-West Pacific. The major shipments were to be to Australia and to New Caledonia, which the American planners regarded as a tempting objective for the Japanese, partly because of its strategic position on the Pacific supply line and partly because of its chrome and nickel deposits. There was, however, an increasingly obvious need for the establishment of other island garrisons throughout the Pacific. By the closing stages of the conferences some 36,000 air, anti-aircraft and engineer troops were listed for Australia, and about 16,000 infantry and service troops for New Caledonia. It was planned to get these on the water during January and February 1942 though the shipping position was such that it remained uncertain when the necessary equipment and supplies for them could be transported. No decision was taken, however, to send army ground forces to Australia.

Among the most important results of the December conferences was agreement between Britain and America regarding the machinery to be set up for the strategical command and control of their military resources. This machinery was to be based on the Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee composed of the American Joint Chiefs of Staff and four representatives of the British Chiefs of Staff. The first expression of this principle of unity of command was to be in ABDACOM (American, British, Dutch, Australian Command) under General Wavell.20 The course of events in the ABDA Area was, however, short and unfortunate, and, as the situation in Malaya rapidly deteriorated, a revision of planning in relation to the disposition of ground forces became vital. On 13th February Wavell cautiously but plainly foreshadowed the loss of Sumatra and Java and opened the question of the diversion to Burma of either the 6th or 7th Australian Divisions (then bound for Java and Sumatra respectively) or both. Before this question was decided, however, and on the day after Wavell’s warning, the American War Department abruptly decided to send ground combat forces and their ancillary services to Australia as well as air and anti-aircraft units. Almost at once movement orders were issued to the 41st Division and supporting troops. By 19th February shipping for the move was available.

This decision implied a new development in American strategy. When the question of the diversion of the Australian divisions to Burma was raised both Churchill and Roosevelt urged agreement upon the Australian Prime Minister, Mr Curtin. But Curtin, advised by his Chiefs of Staff, was resolute in his refusal. The wisdom of his decision was to be underlined by events which followed in Burma and by events later in the year in New Guinea. However, in his exchanges with Curtin, the President

defined his understanding that the maintenance of one Allied flank based on Australia and one on Burma, India and China must call for an Allied “fight to the limit” and he declared that “because of our geographical position we Americans can better handle the reinforcement of Australia and the right flank. I say this to you so that you may have every confidence that we are going to reinforce your position with all possible speed.”21

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Army Forces in the Far East, had withdrawn his forces to the Bataan Peninsula by early January and the end of large-scale resistance was in sight. On 22nd February, with Singapore surrendered, ABDACOM disintegrating, and plans for the firm definition of the Pacific as an area of clear American responsibility within the Allied strategic pattern taking shape in his mind, Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to Australia with a view to having him accepted “as commander of the reconstituted ABDA Area”.22

While these events were developing the Australian leaders had become increasingly dissatisfied with the lack of voice accorded them in the determination of strategic decisions which affected Australia vitally. They felt that there was reluctance, on the part of Great Britain particularly, to grant to Australia any real part in the direction of policy. When ABDACOM was created they were disturbed by the fact that they were not represented on the Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee from which Wavell would receive his orders and dissatisfied with the scanty Australian representation on ABDA Headquarters. On 5th February, only partly placated by a limited form of representation in the United Kingdom War Cabinet and only because of the urgency of the situation, the Australian War Cabinet approved proposals for the establishment of a Pacific War Council (on which Australia would be represented) in London and for direction of the Pacific war by the Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee in Washington—while still requesting the establishment in Washington of a Pacific War Council with a constitution and functions acceptable to Australia.

On 26th February the Australian and New Zealand Chiefs of Staff reviewed the situation in the Pacific. They declared that their countries were in danger of attack, emphasised the need to plan for an offensive with Australia and New Zealand as bases and recommended the establishment of an “Anzac Area” with an American as Supreme Commander (to replace one which had already been defined on 29th January as an area of joint naval operations under Vice-Admiral Herbert F. Leary, United States Navy, and to include not only most of the Western Pacific but also New Guinea, Ambon, Timor and the sea within about 500 miles of the Australian west coast). These proposals were cabled to the Dominions Office and to President Roosevelt on 1st March together with proposals for Australian and New Zealand representation on the Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee. A few days later the Australian Government decided that it would welcome the appointment as Supreme Commander of General Brett,

who had returned to command of the American forces in Australia after the dissolution of the ABDA Headquarters where he had been deputy to Wavell.

Concurrently Roosevelt and Churchill had been planning a world-wide division of strategic responsibility and, by 18th March, had reached general agreement on the establishment of three main areas: the Pacific area; the Middle and Far East area; the European and Atlantic area. The United States would be responsible for operations in the Pacific area through the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff who would consult with an advisory council representing Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands Indies, China and possibly Canada. Supreme command in the area would be vested in an American.

In anticipation of this agreement the Joint Chiefs of Staff had been planning the subdivision of the Pacific area. On 8th March, after studying the Australian and New Zealand proposals, they accepted instead the view that the navy was primarily concerned with protecting the Pacific lines of communication and that New Zealand belonged within those lines; they regarded “the Australian continent and the direct enemy approaches there” as a separate strategic entity. They defined Australia and the areas to the north and Northeast as far as and including the Philippines as the South-West Pacific Area (SWPA) which would be an army responsibility under General MacArthur as Supreme Commander, and designated most of the rest of the Pacific as the Pacific Ocean Area for which the navy would be responsible and in which Admiral Chester W. Nimitz would be Supreme Commander.

This was the stage of planning when, on 17th March, after a hazardous dash by torpedo boat and aircraft, General MacArthur arrived at Darwin, and, immediately, General Brett telephoned Mr Curtin and read him a letter which he had prepared in the following terms:

The President of the United States has directed that I present his compliments to you and inform you that General Douglas MacArthur, United States Army, has today arrived in Australia from the Philippine Islands. In accordance with his directions General MacArthur has now assumed command of all United States Army Forces here.

Should it be in accord with your wishes and those of the Australian people, the President suggests that it would be highly acceptable to him and pleasing to the American people for the Australian Government to nominate General MacArthur as the Supreme Commander of all Allied Forces in the South-West Pacific. Such nomination should be submitted simultaneously to London and Washington.

The President further has directed that I inform you that he is in general agreement with the proposals regarding organisation and command of the Australian Area, except as to some details concerning relationship to the Combined Chiefs of Staff and as to boundaries. These exceptions he wishes to assure you, however, will be adjusted with the interested Governments as quickly as possible.

The President regrets that he has been unable to inform you in advance of General MacArthur’s pending arrival, but feels certain that you will appreciate that his safety during the voyage from the Philippine Islands required the highest order of secrecy.

On the same day the Prime Minister informed the War Cabinet which agreed that he should cable London and Washington:

General Douglas MacArthur having arrived in Australia, the Commonwealth Government desires to nominate him as Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in this theatre. His heroic defence of the Philippine Islands has evoked the admiration of the world and has been an example of the stubborn resistance with which the advance of the enemy should be opposed. The Australian Government feels that his leadership of the Allied Forces in this theatre will be an inspiration to the Australian people and all the forces who will be privileged to serve under his command. If this nomination is approved might I be informed of the text and time of any announcement.

Next day-18th March—Mr Curtin announced the news to the Australian people, who greeted it with enthusiasm. They were soon to find that MacArthur’s reputation lost nothing in the man. Alert and energetic, with an air of command, lean, his face combining the intellectual, the aesthetic and the martial, he was outstanding in appearance and personality. He was proud and, with skilful publicity measures, was soon to build himself into a symbol of offensive action and final victory.

He had been one of America’s leading soldiers for many years. Son of General Arthur MacArthur he was born at a frontier post in 1880 and had shared the lives of soldiers as a boy before he entered West Point in 1899. He served in the Philippines and went to Japan as his father’s aide when the old soldier was sent as an observer to the Russo-Japanese war in 1905. He was in France in 1918 as chief of staff of the 42nd (Rainbow) Division, became commander of the 84th Brigade in that division, and commander of the division itself from 1st November to the Armistice on 11th November 1918. After that war the highest offices in the United States Army came quickly to him. He became Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point in 1919 and then served again in the Philippines for some five of the years 1922–30. In November 1930, he became Chief of Staff of the United States Army and remained in that post for five years (his original term having been extended). He was then appointed Military Adviser to the Philippine Commonwealth Government and later was made a field marshal in the Philippine Army. At the end of 1937 he was retired from the United States Army at his own request but remained with the Philippine Army to continue his ten-year plan for building military strength in the Philippines to a point where they could hope to defend themselves. In July 1941 he was recalled to service with the United States Army, with the rank of lieutenant-general, as commander of the United States Army Forces in the Far East.

But if MacArthur’s record was, in many respects, brilliantly impressive, it was by no means uniformly so. As Chief of Staff he had initiated vigorous and practical reforms in army organisation; but these reforms were an insufficient basis for the demands of the multi-theatre conflict which developed in 1941. He laid the foundation for the development of an American armoured force; but he gave no evidence, for example, of possession of the vision of the British and German tank enthusiasts. He foresaw that “the airplane, the physical embodiment of the spirit of speed, has become an indispensable member of the military team”; but one of his reforms, the establishment of the General Headquarters Air

The Pacific Theatre

Force in 1934, proved inadequate for the needs of the new war—nor did he handle his air force effectively in the Philippines. He appreciated the fundamental importance of speed and mobility in war; but the Japanese caught him off balance in the Philippines with the speed of their own movement and destroyed a large part of his air forces on the ground. As the attack by the Japanese in December was being prepared he miscalculated their intentions and timing and was over-confident of his powers to check them in the Philippines where they quickly defeated him.

In his personality and actions there were contradictions. He stirred the profoundest admiration and loyalty in many; but provoked resentment, dislike and outright hostility in others. He had physical courage; but from the time the withdrawal to Bataan was completed (about 6th January) until he departed from Corregidor on 12th March he left that fortress only once to visit his hard-pressed troops in Bataan.23 He was resolute; but when President Quezon of the Philippines shocked the American leaders in Washington by proposing that the Philippines be granted immediate and unconditional independence and forthwith be neutralised by agreement between the United States and Japan, MacArthur himself was prepared to consider Quezon’s proposals. He was uncompromisingly loyal to many of his associates; but, in conversation with Brett after his arrival in Australia, he heaped abuse on his Philippine Air Force and its commander (whom Brett from long personal knowledge and a fighting association in Java considered a proved “energetic and capable officer” and whose own version of events was quite different from MacArthur’s) and asserted that Admiral Thomas C. Hart (commanding the United States Asiatic Fleet) “had run out on him”. A few days after his arrival in Australia he announced:

My faith in our ultimate victory is invincible and I bring to you tonight the unbreakable spirit of the free man’s military code in support of our just cause. ... There can be no compromise. We shall win or we shall die, and to this end I pledge you the full resources of all the mighty power of my country and all the blood of my countrymen.

But there is evidence that, in those early days, he was not only dismayed but aghast at the situation in which he found himself. Brett, who knew him, served under him, and suffered much from his moods, wrote of him:

a brilliant, temperamental egoist; a handsome man, who can be as charming as anyone who ever lived, or harshly indifferent to the needs and desires of those around. His religion is deeply a part of his nature. ... Everything about Douglas MacArthur is on the grand scale; his virtues and triumphs and shortcomings.24

When MacArthur arrived in Australia he found an unbalanced assortment of less than 25,000 of all ranks and arms of the American forces;

of the Australian forces, on whom he would have to depend chiefly for some time to come, many of the main “cutting edge”—the tried AIF were still overseas.

As a result of the revised planning which had followed the collapse of ABDACOM the 7th Australian Division had been diverted to Australia and would disembark at Adelaide between 10th and 28th March. Two brigades of the 6th Division had been diverted to Ceylon and only the headquarters and the 19th Brigade of that division were then on their way to Australia. The 9th Division was still in the Middle East—and was likely to remain there since the British leaders considered its retention of the highest importance, and, at Mr Churchill’s suggestion, early in March the United States had offered to send a second division to Australia if the Australian Government would agree to leave the 9th Division temporarily where it was. The offer was accepted and on 28th March the 32nd Division, then preparing to move to northern Ireland, was ordered to prepare for movement to Australia.

Soon after MacArthur’s arrival the Australian and New Zealand Governments were informed of the detailed proposals for the division of the world into three Allied strategic theatres and the proposals for the subdivision of the Pacific. They united in their protests, seeing themselves and their adjacent islands as one strategic whole. They were over-ruled on the grounds that the division was one of convenience only and did not mean that there would be any absence of joint planning and cooperation.

On 1st April the new Pacific War Council, which President Roosevelt had planned would act in a consultative and advisory capacity to the Chiefs of Staff, was constituted in Washington with Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, China and the Netherlands represented. On 3rd April Dr Evatt (the Australian representative) cabled to Curtin the full text of the directives which had been framed for issue to General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz and asked for formal approval to be given as soon as possible. These defined the Pacific Theatre and, within it, the South-West Pacific Area, the South-East Pacific Area and the Pacific Ocean Area, within the last-named defining also the North Pacific, Central Pacific and South Pacific Areas.

The instructions to General MacArthur were:

1. The South-West Pacific Area has been constituted as defined.

2. You are designated as Supreme Commander of the South-West Pacific Area, and of all Armed Forces which the Governments concerned have assigned or may assign to this Area.

3. As Supreme Commander you are not eligible to command directly any national force.

4. In consonance with the basic strategic policy of the Governments concerned, your operations will be designed to accomplish the following:

(a) Hold the key military regions of Australia as bases for future offensive action against Japan, and strive to check Japanese aggression in the South-West Pacific Area.

(b) Check the enemy advance across Australia and its essential lines of communication by the destruction of enemy combatant, troop and supply ships, aircraft, and bases in Eastern Malaysia and the New Guinea–Bismarck–Solomon Islands region.

(c) Exert economic pressure on the enemy by destroying vessels transporting raw materials from recently conquered territories to Japan.

(d) Maintain our position in the Philippine Islands.

(e) Protect land, sea and air communications within the South-West Pacific Area and its close approaches.

(f) Route shipping in the South-West Pacific Area.

(g) Support operations of friendly forces in the Pacific Ocean Area and in the Indian Theatre.

(h) Prepare to take the offensive.

5. You will not be responsible for the internal administration of the respective forces under your command, but you are authorised to direct and coordinate the creation and development of administrative facilities and the broad allocation of war materials.

6. You are authorised to control the issue of all communiques concerning the forces under your command.

7. When task forces of your command operate outside the South-West Pacific Area, coordinate with forces assigned to areas in which operations will be effected by Joint Chiefs of Staff, or Combined Chiefs of Staff, as appropriate.

8. Commanders of all armed forces within your area will be immediately informed by their respective Governments that, from a date to be notified, orders and instructions issued by you in conformity with this directive will be considered by such Commanders as emanating from their respective Governments.

9. Your staff will include officers assigned by the respective Governments concerned, based upon requests made directly to national Commanders of the various forces in your area.

10. The Governments concerned will exercise the direction of operations in the South-West Pacific Area as follows: –

(a) The Combined Chiefs of Staff will exercise general jurisdiction over the grand strategic policy and over such related factors as are necessary for proper implementation, including the allocation of forces and war materials.

(b) The Joint United States Chiefs of Staff will exercise jurisdiction over all matters pertaining to operational strategy. Chief of Staff of the whole Army will act as executive agency for Joint United States Chiefs of Staff. All instructions to you to be issued by or through him.

The most important parts of Admiral Nimitz’s directive were:

In consonance with the basic strategic policy of the Governments concerned, your operations will be designed to accomplish the following:

(a) Hold the island positions between the United States and the South-West Pacific Area necessary for the security of the lines of communications between those regions; and for the supporting naval, air and amphibious operations against the Japanese forces.

(b) Support the operations of the forces in the SWPA

(c) Contain the Japanese forces within the Pacific Theatre.

(d) Support the defence of the Continent of North America.

(e) Protect the essential sea and air communications.

(f) Prepare for the execution of major amphibious offensives against positions held by Japan, the initial offensives to be launched from the South Pacific Area and South-West Pacific Area.

Mr Curtin, still not completely satisfied with the boundaries proposed, now, however, acquiesced in the proposals for subdivision, in view of the urgency of the situation. But he insisted that any power to move Australian troops out of Australian territory should be subject to prior consultation and agreement with the Australian Government and pointed out that, in this respect, the limitations imposed by existing Commonwealth defence legislation should be borne in mind constantly. He also demanded clarification of the powers of the Commonwealth concerning the direction of operations in the South-West Pacific Area, while making it clear that he disapproved of political intervention in purely operational matters; a demand which he considered was completely justified by the fact that Australia was not represented either on the committee which controlled strategical policy or the one which controlled operational strategy.

A partial solution, at least, to these problems was achieved by recognition of the right of appeal of a local commander to his own government, and through the definition of the following principles in a note to the President by the United States Chiefs of Staff:

Proposals of United States Chiefs of Staff (for operations in the South-West Pacific Area) made to the President as United States Commander-in-Chief, are subject to review by him from the standpoint of higher political considerations and to reference by him to the Pacific War Council in Washington when necessary. The interests of the Nations whose forces or land possessions may be involved in these military operations are further safeguarded by the power each Nation retains to refuse the use of its forces for any project which it considers inadvisable.

Such was the singleness of purpose, however, of both the Prime Minister and General MacArthur in pursuing their common aim of driving back the Japanese that the problems which had loomed large on paper rarely occurred in practice to disturb the close relationship which grew up between the two men. MacArthur never yielded in his attitude that the Pacific was the main war theatre and offered the best opportunities for opening a “second front” which would help the Russians. To this end, he reiterated, the first step was to make Australia secure; the second was to organise Australia as a base for a counter-stroke. And he asked Mr Curtin to secure from outside, particularly from the United States, the maximum assistance that was available. This the Prime Minister attempted—a task at which he never slackened.

In his preliminary comments on the text of MacArthur’s directive Curtin had asked, on 7th April, for additional naval and air forces, particularly aircraft carriers. On 23rd April he was told that the total strength of the American forces, ground and air, allotted to the SWPA was 95,000 officers and men. After discussions with MacArthur he then cabled to Evatt that MacArthur was “bitterly disappointed”, that the proposals regarding the air forces, together with the fact that there was no increase

in the naval forces, produced a situation in which MacArthur could not carry out his directive and which “leaves Australia as a base for operations in such a weak state that any major attack will gravely threaten the security of the Commonwealth. Far from being able to take offensive action ... the forces will not (repeat not) be sufficient to ensure an adequate defence of Australia as the main base.”

At the same time Curtin was mindful of a promise which Churchill had made on 17th March: “the fact that an American Commander will be in charge of all the operations in the Pacific Area will not be regarded by His Majesty’s Government as in any way absolving them from their determination and duty to stand to your aid to the best of their ability, and if you are actually invaded in force, which has by no means come to pass and may never come to pass, we shall do our utmost to divert the British troops and British ships rounding the Cape, or already in the Indian Ocean, to your succour, albeit at the expense of India and the Middle East.” Curtin therefore requested assistance from Britain, by the diversion of two divisions whose movement East was projected for late April and early May, and by the allocation of an aircraft carrier “even of the smallest type”. Churchill, however, refused, saying: “No signs have appeared of a heavy mass invasion of Australia”, and “the danger to India has been increased by the events in Burma as well as by an inevitable delay, due to the needs in home waters, in building up the Eastern Fleet”. As far as aid from Britain was concerned, then, Curtin was left with what gloomy comfort he could draw from a further promise made by Churchill on 30th March:

During the latter part of April and the beginning of May, one of our armoured divisions will be rounding the Cape. If, by that time, Australia is being heavily invaded, I should certainly divert it to your aid. This would not apply in the case of localised attacks in the north or of mere raids elsewhere. But I wish to let you know that you could count on this help should invasion by, say, eight or ten Japanese divisions occur. This would also apply to other troops of which we have a continuous stream passing to the East. I am still by no means sure that the need will arise especially in view of the energetic measures you are taking and the United States help.

Meanwhile Australia’s agreement to the detailed arrangements under which MacArthur would work had become effective from midnight on 18th April. MacArthur’s growing ground forces in Australia then totalled some 38,000 Americans, 104,000 of the AIF, and 265,000 in the militia. Before his arrival integration of American and Australian forces had been achieved through a system of joint committees. He now established a General Headquarters in Melbourne and organised his forces into five subordinate commands: Allied Land Forces, which included all combat land forces in the area, under General Blamey; Allied Air Forces under Lieut-General Brett; Allied Naval Forces under Vice-Admiral Herbert F. Leary; United States Army Forces in Australia, responsible for the administration and supply, in general, of American ground and air forces, under Major-General Julian F. Barnes; United States Forces in the Philip-

pines, a fast-wasting asset, under Lieut-General Jonathan M. Wainwright. All of these commanders, except Blamey, were Americans (and MacArthur had agreed to the appointment of an Australian to the combined ground command only at the insistence of the War Department in Washington).

By this time Blamey already had a radical reorganisation of the Australian Army under way. On 2nd February, then in Cairo, he had proposed to Curtin that he should move to the Far East as soon as the Middle East situation was sufficiently clear. On 18th February the War Cabinet had decided that Blamey should return to Australia, and Lieut-General L. J. Morshead should command the AIF in the Middle East. With the air link to Australia then disrupted Blamey flew from Cairo to Capetown early in March and took ship to Australia on the 15th. On the voyage he heard the announcement of MacArthur’s appointment and commented: “I think that’s the best thing that could have happened for Australia.” When he reached Fremantle on 23rd March he was handed a letter from Curtin telling him that the Government proposed to appoint him “Commander-in-Chief, Australian Military Forces”.

The War Cabinet had made this decision on 11th March, appointing Lieut-General Lavarack of the I Corps to act until Blamey’s arrival. On the 16th the Military Board recommended that the Australian Commander-in-Chief should become “Commander-in-Chief Allied Armies in the Australian Area” upon the appointment of a Supreme Commander in the Anzac Area; that, until the appointment of the Supreme Commander, the Board should cease to function but, on the appointment being made, should be reconstituted as the senior staff of the Commander-in-Chief. The Minister for the Army, Mr Forde, declined to submit these proposals to the War Cabinet until after Blamey’s arrival. On 26th March the War Cabinet considered them and, on Blamey’s advice, decided that the Military Board would cease to function and the heads of its Departments would become Principal Staff Officers under the Commander-in-Chief. On the same day Blamey assumed his appointment.25

On 9th April Blamey issued the orders which defined the main lines of his reorganisation. Army Headquarters were to become General Headquarters (Australia). (In late May they were redesignated Allied Land Forces Headquarters—LHQ) The land forces in Australia were to be organised into a field army and lines of communications. A First Army (Lieut-General Lavarack) was to be created and located in Queensland and New South Wales, absorbing Northern and Eastern Commands. A Second Army (Lieut-General Mackay) was to be located in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania, absorbing Southern Command. (Not long afterwards, however, the Second Army took over also most of the troops in New South Wales.) The field troops in Western Australia (Western Command) became the III Corps (Lieut-General Bennett). Headquarters and some of the units of the 6th Division which had arrived in or were

immediately returning to Australia (two brigades, as mentioned, having been ordered to remain in Ceylon) were to move to the Northern Territory where the 6th Division would absorb the 7th Military District. (Shortly afterwards this command became the Northern Territory Force.) The troops in Papua and New Guinea (8th Military District) were to become New Guinea Force (Major-General Morris26). Except in the Northern Territory and New Guinea the fixed coastal defences, anti-aircraft units and garrison battalions were to be under the lines of communications area commanders.

Command was to pass from the home forces commander to the two army commanders at 6 p.m. on 15th April; the headquarters of the various commands and military districts were to cease operating from the same time.

Within this organisation on 15th April there were ten Australian divisions—seven infantry, two motor (formerly cavalry), one armoured; the Northern Territory and New Guinea Forces, each with a numerical strength roughly equivalent to that of a division; and one incomplete American division—the 41st. (Most of the 32nd Division was scheduled to arrive by mid-May). Of these divisions, the First Army included the following: 1st (Major-General Clowes); 2nd (Major-General Lloyd27); 3rd (Major-General Savige); 5th (Major-General Milford28)—newly formed in Queensland from the 7th, 11th and 29th Brigades; 7th (Major-General Allen); 10th (Major-General Murray)—newly formed from the Newcastle Covering Force; 1st Motor (Major-General Steele29). The First Army was organised into two corps: I Corps (Lieut-General Rowell); II Corps, under Lieut-General Northcott who, for the past seven months, had commanded the 1st Armoured Division. The Second Army comprised three formations; the 2nd Motor Division (Major-General Locke30); the 41st U.S. Division (Major-General Horace H. Fuller) ; the 12th Brigade Group. (The 32nd U.S. Division would go to the Second Army on arrival.) In Western Australia the III Corps included the 4th Division (Major-General Stevens31) and a number of unbrigaded units. As his reserve Blamey temporarily retained the 1st Armoured Division (Major-General Robertson) and the 19th Brigade. (The 19th Brigade, however,

soon went to the Northern Territory and, on 19th May, Blamey was to write to General Bennett that he proposed to add the armoured division and an infantry division to the latter’s command, “keeping in mind the possibility of an eventual offensive to the north from the area of your command”.)

The main troop movements resulting from these groupings involved the 7th and 4th Divisions. The former, disembarking at Adelaide, was to be concentrated in northern New South Wales by 27th April (and it moved to southern Queensland soon afterwards). On 1st April there were only two infantry brigades in Western Australia. To build up the strength there of the 4th Division, 6,000 men were to move from Victoria.

On 10th April, Blamey issued his first Operation Instruction as Commander-in-Chief to the commander of the First Army. He stated that the retention of the Newcastle–Melbourne area was vital but the probability of a major attack thereon was not then great because the enemy’s main concentrations were in Burma and the Indies. The enemy’s first effort southwards from the Mandates would probably be “an attempt to capture Moresby followed by a landing on the Northeast coast with a view to progressive advance southwards covered by land-based aircraft”. He added:

In view of the limitations of resources, it is not possible at present to hold the coastline from excluding Townsville to excluding Brisbane. As our resources increase it is intended to hold progressively northwards from Brisbane.

On 18th April, after Blamey’s reorganisation of the army had become effective, MacArthur formally assumed command of Australian forces. Curtin had written to him on 17th April:

I refer to ... your directive, regarding the assignment of Forces to your Command and notification to local commanders as to the date of commencement of the Supreme Command.

2. In accordance with the terms of your directive, taken in conjunction with the official memorandum by the United States Chiefs of Staff, which forms part of your directive, I would inform you that the Commonwealth Government assigns to the South-West Pacific Area under your command all combat sections of the Australian Defence Forces. These Forces are as follows:

Navy—The Naval Forces at present operating under Admiral Leary.

Army—The 1st Army

the 2nd Army

the 3rd Corps

the 6 Division (Darwin)

the New Guinea Force

Air—All Service Squadrons but not including training units.

3. In accordance with Article 8 of your Directive the Commonwealth Government is notifying its Commanders of the Forces assigned to the South-West Pacific Area that, as from 12 midnight on Saturday 18th April 1942, all orders and instructions issued by you in conformity with your directive will be considered by such Commanders as emanating from the Commonwealth Government.

At this stage it was obvious that the changes brought about by MacArthur’s appointment were more sweeping even than had first appeared. It was reasonable to expect that the Supreme Commander would work

through a headquarters which, throughout its various layers, would represent in due proportion the Australian as well as the American forces under his command; the Australian far outnumbered the American and seemed likely to continue to do so for a long time. (That such integration was practicable was to be demonstrated later in the European theatres.) But no such development took place in Australia although the Australians were to be represented on MacArthur’s headquarters by a rather shadowy liaison organisation and their own Army Headquarters, under General Blamey, was to remain intact, though as an entirely separate and virtually subordinate entity. The absence of a combined staff was the more remarkable because of the existence, from the beginning, of the following factors (other than those which related to mere numbers) : General Blamey was far more experienced in actual war than any of the American commanders, including MacArthur. Blamey’s experience in the 1914–18 War had been long and varied and he had emerged from that war with a glowing military reputation. His service between the wars was of a high order. His leadership of the Second AIF, and his discharge of responsibility as Deputy Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, had brought him valuable experience and had shown that he, probably more than any other high-ranking officer in the Australian Army, could combine military skill and political shrewdness in the degree demanded in a Commander-in-Chief. Blamey’s subordinate commanders in the Australian Army and his senior staff officers had had far wider experience of war than their American counterparts. Inevitably their service in the 1914–18 War had, as a rule, been far longer; and of the seventeen army, corps, divisional and force commanders, eleven were fresh from hard-fought Middle East campaigns, and one had fought the Japanese in Malaya. These, and the other Australian leaders, had evolved a staff organisation which functioned efficiently under the direction of highly-trained and experienced staff officers in key positions. The headquarters of the First Army, for example, was formed by enlarging that of the I Corps, an expert team which had controlled operations in two Middle East campaigns.