Chapter 9: Eora Creek

WHEN he set out on 3rd October to take over from Brigadier Eather, Brigadier Lloyd was eager for action, his men no less so. Their desire to measure themselves against the Japanese had been sharpened by the importance of the occasion. They passed General MacArthur near Owers’ Corner on their way forward. He said then: “Lloyd, by some act of God, your brigade has been chosen for this job. The eyes of the western world are upon you. I have every confidence in you and your men. Good luck and don’t stop.” MacArthur was making his first visit to New Guinea. He arrived on 2nd October, spent about an hour at Owers’ Corner on the 3rd, and thus was able to see from a distance the country in which the troops were operating, and departed on the 4th.

Lloyd was a genial leader with something of the manner of an English regular officer. He was well into his forty-ninth year at this time; the New Guinea mountains might prove too much for him physically. He took care to know personally as many of his officers and men as he could and let them see that he was interested in them and thought they were grand people. They returned his respect and liking. He was a veteran of the 1914-18 War, during which he had proved himself an able and high-spirited young officer, and he had rounded off his service with a term in the Indian Army. In 1940 he took the 2/28th Battalion away, led it during the siege of Tobruk and later succeeded to command of the 16th Brigade. As recently as the second week of August he and his brigade had arrived from Ceylon, so that they had had little time to savour their return home before they were committed once more to an overseas venture. The British Prime Minister and General Wavell had been unwilling to release them and the 17th Brigade from the garrison of Ceylon. The fact, however, that these troops were urgently needed at home was demonstrated when only 36 days elapsed between the disembarkation of the 16th Brigade at Melbourne and its re-embarkation for New Guinea. The men were not unready for jungle warfare, having trained for it strenuously in Ceylon.

The 16th Brigade had been tried in the desert and Greece, and, in part, in Crete and Syria. General Allen, who now commanded the 7th Division of which it had just become a part, had been its original commander and expected much of it. Eather, whose brigade it now relieved, had been one of its original battalion commanders and was watching it with critical anticipation.

The brigade had arrived in New Guinea on 21st September. On 3rd October the 2/3rd Battalion (30 officers and 587 men) began to move forward from Owers’ Corner. Next day the 2/2nd Battalion followed with 26 officers and 528 men. Two days later 27 officers and 581 other ranks of the 2/1st took the track. In addition to his arms and ammunition,

each officer and man carried three days’ emergency and three days’ hard rations, with the inevitable “unconsumed portion of the day’s ration”. His haversack contained his toilet gear, a change of clothing, sweater and dixie. Half a blanket rolled in his groundsheet and strapped on to the back of his belt, a gas cape (as protection from the weather) and a steel helmet completed his outfit. With each company went the normal complement of light machine-guns and sub-machine-guns, rifles and bayonets, a liberal supply of grenades, ammunition and machetes. For each battalion one 3-inch mortar with twenty-four bombs and one Vickers machine-gun with 3,000 rounds was carried.

Quickly the men settled to conditions along the track. On the 6th, when a prisoner was handed over to them at Menari by the 25th Brigade, they saw their first Japanese and found him “an unprepossessing specimen”. With the eager boyishness which remained with so many Australian soldiers in spite of their grimness in action, they took a dump of discarded felt hats which had been torn almost in halves when they were dropped at Menari and sewed them into raffish shapes to wear in styles varying from light-hearted Alpine to rakish Mexican “Viva Villa”. They reacted sombrely to the atmosphere of the Efogi battle-ground where the 21st Brigade had fought so desperately.

Along the route (wrote the diarist of the 16th Brigade) were skeletons, picked clean by ants and other insects, and in the dark recesses of the forest came to our nostrils the stench of the dead, hastily buried, or perhaps not buried at all.

At Myola, where they guarded the dropping areas and gathered the stores, they began to appreciate fully the supply difficulties they would face and the problems their wounded would represent to them.

By the 19th their last illusions about the difficulties which faced them vanished as they tried to relieve the 25th Brigade forward of Templeton’s Crossing in the midst of an engagement. In the afternoon of that day, among other patrols, one led by Lieutenant Ryan1 went out from the 2/2nd Battalion to the ridge east of Templeton’s Crossing. He came against a strong position, his patrol was badly mauled, and he himself, shot in the stomach, was barely able to drag himself into the nearest Australian positions.

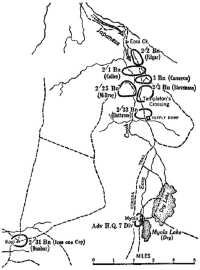

By the early evening Eather and Lloyd had planned that, next day, the 20th, Lieut-Colonel Edgar would send his 2/2nd Battalion from the Australian right flank against the Japanese who were savagely thrusting at the 3rd, Eather’s most forward battalion, while Lieut-Colonel Cullen would try to relieve the 3rd with his 2/1st Battalion and Lieut-Colonel Stevenson’s 2/3rd Battalion would take over from both the 2/25th and 2/33rd.

It will be recalled that the track from Templeton’s Crossing followed the right-hand side of the great Eora Creek ravine, over about two hours and a half of difficult going for an unburdened man, before it reached Eora Creek village; that first it rose high up the mountainside through

the dripping bush until even the roar of the torrent below could be heard no more. Nothing could then be seen from the track except the rain forests pressing in. It was broken by upward-rearing ridges which cut across it at right angles as it made its way over the torn side of the mountain and before it fell steeply down again to the water. Japanese were now bitterly blocking this track immediately beyond Templeton’s Crossing.

When Edgar (a composed and experienced soldier) was ordered to push the Japanese from these positions he planned to do it with four companies. Two would swing wide to the right of the 3rd Battalion, move northward along the heights of the main ridge which paralleled the track, and then turn left to drive down parallel spurs at right angles to the track in front of the 3rd Battalion’s positions. The other two companies would thrust forward at the closer reaches of the track, also from right of the 3rd Battalion, to sustain that flank and to support the rear of the foremost attackers.

On the morning of the 20th a cold gloom hung over the mountains. Water was dripping from the sodden trees and falling soundlessly on a sodden carpet of mould. Captains Ferguson2 and Baylis,3 whose companies were to do the wide outflanking movement, were on the move from 8 a.m., Ferguson leading. The 3rd provided guides to pilot them clear of its right. Ferguson moved then on a bearing of 70 degrees, his men behind him in single file as they made their difficult way up the slope through the cold, wet bush. The dank odour of tropical decay hung heavy in the air. High up the slope they swung left and moved painfully towards their assembly area. By 11 a.m. Ferguson was in position on the most forward spur, Baylis ready on the parallel spur on his left as they faced west towards the Japanese positions. On the hour the two companies went into the attack, moving deliberately down the slope over broken ground and through thick bush.

In Ferguson’s company Lieutenants Hall4 and Blain5 had their platoons forward, Hall on the right. Ferguson, with a runner and an Intelligence man, was advancing between the two. Sergeant Barnes’6 platoon was in reserve, on loan from Headquarters Company to replace Ryan’s platoon which had been cut about the previous day.

In Baylis’ company Lieutenants Tanner7 and Wickham8 were on the right and left of the advance respectively, Lieutenant Goodman’s9 platoon

in reserve. The platoons were moving still in single file, scouts well ahead, ready to fan out into open formation on contact.

The Australians went forward with slow care in the eerie mountain silence. A twig cracking sounded loud and sharp. About 200 yards down the most forward slope Hall and Blain came against the Japanese outpost positions, and then noises of battle rolled out, and the advance passed on. A further 100 yards and the attackers were against the first of the main enemy positions—about fifteen pits round perhaps four light machine-gun posts and spreading over both company features. These pits were well concealed and almost the first intimation Ferguson had of their presence was a devastating fire which swept through his little force. Among others Hall fell dead but his men encircled the position and gradually rooted the defenders out of their holes. Again the slow advance went forward, this time to come up against a line of main Japanese positions. When the defenders were forced out of these Ferguson had come to the end of his spur. He swung left then across to Baylis’ feature where he brought his depleted force in behind the other company as support. By that time the other forward platoon commander, Blain, was dead, with a number of his men, and Barnes, leader of the third platoon, was wounded.

Baylis’ men had been engaged simultaneously with Ferguson’s. First they came against a forward Japanese platoon but, covering behind trees, supported by light machine-gun fire and grenading, they drove ahead at a cost of only two men. After they had fought forward for about another 100 yards heavy machine-gun fire swept them. Tanner fell there, with several of his men. Quickly Baylis ordered Goodman to leapfrog through the leaderless platoon which would then become the reserve. As Goodman’s first section moved down it was pinned by machine-gun fire. The other two sections swung out of the fixed lines. Corporal Roberts10 closed his section on to a machine-gun post and bombed it into silence. The Australians kept pressing against the remaining strength of this position, able to see little in the thick bush but firing at the bases of trees and other likely targets. Finally the surviving Japanese broke and fled from these second strongpoints leaving equipment and rifles behind them. But after the attackers had followed on for about another 150 yards heavy fire smashed into them again and held them close to the earth. At Baylis’ request Colonel Edgar then turned the mortars on to the Japanese but with little apparent effect. Later Baylis asked the colonel if he could arrange for an attack from the other side by a company of the 2/1st Battalion so that, between them, the two companies could squeeze the defenders out. When Edgar told him, however, to press on alone Baylis sent his second-in-command, Captain Blamey,11 round the left flank with the remnants of Tanner’s platoon while the other two platoons harassed the

Japanese with fire. In the face of this threat their enemies withdrew as darkness lowered. Baylis thought his men had killed at least 12 of them in the day but he had lost 5 men killed and 10 wounded.

The two companies then dug in together for the night in box formation. In describing the scene later, two officers wrote:

As we dug a two company perimeter for the night a desolate scene was presented: our own and enemy dead lying in grotesque positions, bullet-scarred trees with the peeled bark showing ghostlike, our own lads digging silently. And with the coming of darkness came the rain, persistent and cold, and in this atmosphere we settled in our weapon pits for the night. At night we could hear the Jap chattering and moving about.12

While Baylis and Ferguson had been thus engaged Captains Fairbrother13 and Swinton14 had been moving the other rifle companies into action. Fairbrother issued his final orders in the dim mountain dawn and then, at 8.30, with guides from the 3rd Battalion, led out through that battalion’s right, north along the main ridge, to turn against the Japanese positions which lay astride the track and between the 3rd Battalion and Baylis’ and Ferguson’s objectives. Approximately where he would hit the main track a small pad crossed it at right angles.

At 10.18 a.m. the forward scouts of Lieutenant Smith’s15 platoon, which was leading, came under fire. Smith’s men pushed on until machine-gun fire whipped them to the ground. Although unable to locate his enemies or decide their strength Fairbrother then sent Lieutenant Hodge’s16 platoon wide to the right and, after that, on to the track in the rear of Smith’s assailants. There Hodge held although he was flailed from farther ahead.

Meanwhile Swinton had been moving on the flanks and rear of Fairbrother’s advance. Learning of Hodge’s difficulties he sent Sergeant Lacey’s17 platoon round the right flank to try to help him. But Lacey had gone only about 300 yards when his men began to fall to a heavy fire. Swinton then ordered Lieutenant Coyle’s18 platoon to circle round Smith’s left and fall upon the holding forces from that direction. This Coyle did with some success and without loss. Meanwhile Swinton had sent Lieutenant Irvin’s19 platoon to help Lacey, but Irvin’s men, in their turn, found themselves beaten at by fire.

Night was coming now and, as the two companies farther forward had done, Fairbrother and Swinton dug into a perimeter defence for the

6 p.m., 20th October

night. Fairbrother had lost 6 men killed and 10 wounded, Swinton 4 killed and 4 wounded.

While the 2/2nd Battalion had thus been leading the 16th Brigade’s initial attack the 2/1st had been “doubling up” in the 3rd Battalion area, its orders being to continue the advance when the 2/2nd had cleared the track. The companies were all in position before 10.30 a.m. on the 20th, trying to support the 2/2nd’s attacks with mortar and light machine-gun fire. But this task proved most difficult as, though the foremost Japanese were less than 100 yards in front, they were not visible, nor could the fall of fire be observed. When the attacking forces were held in the afternoon it was decided that Captain Catterns’20 company of the 2/1st should attack from the right of the main Australian positions early on the 21st and move forward down the main track.

Now, also, Lloyd’s third battalion was entering the scene. As Edgar and Cullen were manoeuvring in the face of the Japanese Lieut-Colonel Stevenson was bringing his 2/3rd forward from Myola. By 3.30 p.m. it had arrived at Templeton’s Crossing and relieved the 2/25th and 2/33rd.

When the night came, on 20th October, therefore, Lloyd’s brigade was concentrated at Templeton’s Crossing and in close contact with the Japanese. Backing it closely was the 3rd Battalion (which was remaining in the area on attachment to protect Alola after its capture and prepare the dropping grounds there) and a platoon from the 2/33rd Battalion was in position to strengthen the right flank.

On the morning of the 21st the Australians were early astir. Catterns moved his company round the right flank through Ferguson’s and Baylis’ positions. Soon after 10 a.m. the three companies were advancing down the slopes towards the track. But the Japanese had gone. The Australians estimated that they had been holding there with at least a battalion, and Baylis himself thought that the positions his men had actually cleared the

previous day were of company strength. Abandoned equipment and papers lay about. After they had combed the area across the track and down to the creek the two companies of the 2/2nd rejoined their battalion higher up the slope while Catterns’ men pushed on along the track.

Meanwhile the other companies had been having a similar experience. Fairbrother’s early morning patrols found the track clear immediately in front of them. There the Japanese had been fighting from what appeared to have been a platoon position in which 14 dead men now lay among scattered rifles and equipment. At 9.30 Captain Brown21 of the 2/3rd led his company into Fairbrother’s position and then moved eastward towards the crest of the ridge along the small cross-track. He was to clear positions the Japanese had been holding on the higher ground. But those positions too had been abandoned.

With the afternoon a new brigade movement was under way. Brown’s company was moving along a narrow, slippery track high up the slope to the right of, and parallel with, the main track, in places deep in morasses of foul smelling mud, hemmed in by tall trees and dripping bush. Major Hutchison22 joined him there with another company of the 2/ 3rd and took command of both. By that time one of Brown’s patrols had already brushed with a Japanese light machine-gun post on a minor footway leading back towards the main axis and killed one of its crew. The two companies continued a laborious advance until about 5 p.m. when a sudden fire swept over the leading platoon. It killed Private Fernance23 (the first man of the battalion to die in action in this campaign) and wounded two other soldiers. Of that incident Lieutenant MacDougal24 later said:

On the afternoon of the first day out from Templeton’s Crossing, as the leading company was moving along the track with the two forward scouts out in front, there was a sudden burst of fire and the scouts and one man farther back were hit. The company stopped on the track and in the bush on either side while the commanders of the two leading platoons went forward cautiously. Suddenly they were shot at by unseen Japanese evidently dug in at the foot of trees; but, though the shots came from a range of only ten yards—they stepped it out next day—neither of them was hit. As they lay low in the bush they could hear the butt swivel of the Japanese sniper’s rifle clicking as he moved. They went back, under cover. The company camped that night about sixty yards from the Japanese post, spread out across the track ready for attack from any direction. After dark, one of the platoon commanders went out and brought in one of the scouts who had been wounded by the sniper’s first shots.25

MacDougal went on then to speak of the intrepid men who became forward scouts. These led the advance in this bush fighting where there was room along the tracks for men to move only in single file. Normally

they did not expect to see the Japanese who were lying in wait until the ambushers fired. And to that sudden fire the scouts were almost certain to fall, to lie dead on the track, or wounded at the mercy of their enemies, while the rest of the company or platoon, who had been filing behind, fanned out through the thick bush to try to outflank the obstruction. MacDougal said:

On the march during the next weeks each leading company had to send scouts out ahead on the track. It was almost a certainty that once, or perhaps more often, a day the forward scouts on the track, or scouts exploring the Japanese positions across the track, would be killed or wounded by unseen snipers, who would wait until they were twenty yards away or less before firing. Yet there was never any difficulty in finding men for the job. Before the leading platoon moved off in the morning or after a spell, the commander might say: ‘We’ll need two forward scouts.’ Three or four men would begin to collect their gear and come forward. These three or four would arrange among themselves who would go out in front. One would say to another ‘You did it yesterday’, and there would be some quiet discussion until, in a few seconds without any more orders or suggestions from the platoon commander or sergeant, two scouts would be selected and ready.

During that same afternoon of the 21st the 2/1st and 2/2nd Battalions had been moving along the main track in that order, with Catterns’ the vanguard company for the brigade, Captain Sanderson’s26 company following closely and the commanding officer, Cullen, himself moving in rear of Sanderson. At about 2 p.m. the forward scouts came against a Japanese position on a ridge up which the track climbed. Catterns’ men thrust against it but lost 2 killed and 4 wounded. He was trying to outflank round his enemies’ left. But the bush was thick, the upward slope steep and broken. It was 7 p.m. before he was in position to attack. In the fading light the Australians therefore bivouacked. They would attack at first light on the 22nd.

So night came again. The fight for Templeton’s Crossing had ended but it was clear that the fight for the main Eora Creek crossing was only beginning. At that crossing place the country offered what were possibly the most favourable conditions for defence along the whole length of the track between Port Moresby and Kokoda. There, it will be remembered, the main stream, after flowing down an ever-deepening valley from near Templeton’s Crossing, had gouged a deeply sunken and gloomy gorge and was joined by a tributary which flowed in from the South-east. The swirling waters of the two had churned what was almost a great pit around the point of junction. Massive boulders lay in the bed of the stream and the waters rushed round them foaming. Just above the junction a bridge crossed the tributary and just below it a second bridge crossed the main flow. As the track, after rising and falling over humps and razor-back spurs, approached the first crossing, it passed over a bare ridge and through a few miserable native huts—the village of Eora Creek—plunged precipitously down the forward slopes, crossed the first bridge, then followed the echoing floor of the gorge briefly before it twisted west to

Eora Creek, 22nd-23rd October

cross the second bridge. It scrambled north again, crossing a slight widening of the creek valley through broken ways, and, a little farther on, thrust up the scarred side of a mountain so steep that the crags seemed to overhang it. To the right of the track as it crossed the creek forbidding cliffs rose. To the left of the track and creek junction broken country reared high, tumbled and scrub covered, to sweep upwards in an arc of turbulent hills and crevasses into a thrusting feature Northwest of that point and across the track farther on.

In the early morning of the 22nd both Hutchison and Catterns found

that the Japanese had gone. They pushed forward, Hutchison still on the auxiliary track higher up the valley side and followed along that track by the 2/2nd Battalion, Catterns and the rest of the 2/1st on the main track, with the balance of the 2/3rd close behind. About 10.30 a.m. Brown’s company, still leading Hutchison’s detachment, swung on to the main track in front of the 2/1st and entered Eora Creek village. Then mortar and machine-gun fire raked them. Brown and some of his men were hit. They lay in the open for most of the day until, towards dusk, one or two began to struggle back up the slope and Sergeant Carson,27 using his pioneer platoon as stretcher-bearers, made courageous efforts to bring some in, losing one of his bearers killed and one wounded in the process.

When Cullen arrived at the ridge overlooking the village about an hour after Brown was shot, he sent Captain Sanderson and his company across to the left bank of the creek with instructions to work up the ridge above the Japanese on the left and attack from that position.

By early afternoon most of the brigade was blocked on and behind the bare ridge which overlooked the village. Although they did not know it at first they could be seen there by the Japanese who began to shell, mortar and machine-gun them heavily. Lieut-Colonel Stevenson was struck in the ear and his medical officer, Captain Goldman,28 was badly hit.

Goldman was working at the time with Captain Connell,29 medical officer of the 2/1st Battalion, when the regimental aid post they were jointly manning came under heavy fire. Three of their men were killed and Lance-Sergeant Doran30 was painfully wounded in the foot. Doran assisted Connell to carry on, however, and it was not until all the other casualties in the post had been treated that he reported that he himself needed attention.

As the daylight was beginning to fade Brigadier Lloyd studied the situation. It was becoming clear now that the Japanese were strongly entrenched at Eora Creek. On the right of the Australian positions the 2/ 3rd Battalion was deployed. All the men Cullen of the 2/1st could muster there were disposed about the track itself but he had less than half of his battalion with him; on orders from the brigadier, Captain Simpson’s31 company had swung off the track earlier to try to reach Alola by bypassing Eora Creek and most of Headquarters Company had followed in error and were not to rejoin the battalion until next day; Captain Sanderson’s company were still out in the wild country to the left and nothing had been heard of them; one of Captain Catterns’ platoons was

away on a special patrol. The 2/2nd Battalion was in reserve a little farther back along the track in the vicinity of brigade headquarters.

Lloyd decided that, although the Japanese had commanding positions covering them, he would have to attack across the bridges. There were only two other crossing places he could use, one to the right of the first bridge, the other well to the left where Sanderson had already crossed. Even if he did use the ford on the right his attacking forces would have to face the bottleneck of the second bridge; if he used the left-hand ford he felt that he might only be sending men in Sanderson’s footsteps to no additional purpose. He therefore ordered Stevenson’s battalion to secure the bridges themselves by 6 o’clock next morning so that Cullen could cross them and be free to concentrate on attacking the defences on the far side. If Stevenson could not force the bridgehead Cullen would still attack.

Neither of the battalion commanders liked the plan very much. Both were experienced infantry officers: Stevenson, 34 years old, a confident leader and smooth tactician; Cullen, four months younger than Stevenson, stocky, quick-witted, logical and aggressive. But it was difficult to frame an alternative, particularly as Lloyd was well aware of the need for haste.

This need was resulting in a pressure that was becoming increasingly irksome to Allen. On 21st October General Blamey had signalled bleakly:

During last five days you have made practically no advance against a weaker enemy. Bulk of your forces have been defensively located in rear although enemy has shown no capacity to advance. Your attacks for most part appear to have been conducted by single battalion or even companies on narrow front. Enemy lack of enterprise makes clear he has not repeat not sufficient strength to attack in force. You should consider acting with greater boldness and employ wide encircling movement to destroy enemy in view of fact that complete infantry brigade in reserve is available to act against hostile counter-offensive.

You must realise time is now of great importance. 128 US already has elements at Pongani. Capture Kokoda aerodrome and onward move to cooperate with 128 before Buna is vital portion of plan.

On the same day an even more galling signal arrived:

The following message has been received from General MacArthur. Quote. Operations reports show that progress on the trail is NOT repeat NOT satisfactory. The tactical handling of our troops in my opinion is faulty. With forces superior to the enemy we are bringing to bear in actual combat only a small fraction of available strength enabling the enemy at the point of actual combat to oppose us with apparently comparable forces. Every extra day of delay complicates the problem and will probably result ultimately in greater casualties than a decisive stroke made in full force. Our supply situation and the condition of the troops certainly compares favourably with those of the enemy and weather conditions are neutral. It is essential to the entire New Guinea operation that the Kokoda airfield be secured promptly. Unquote.

Next day Allen replied:

I was singularly hurt to receive General MacArthur’s signal of 21st Oct since I feel that the difficulties of operations in this country are still not fully realised. This country does not lend itself to quick or wide encircling movements. In addition owing to shortage of carriers I have been confined to one line of advance. As is

already known to Commander New Guinea Force my available carriers forward of Myola are far below requirements. There is one line of advance which I would certainly have used had I the necessary carriers and that was the Alola–Seregina–Kagi. However, under the circumstances it was quite out of the question. I have complete confidence in my brigade commanders and troops and feel that they could not have done better. It was never my wish to site a brigade defensively in rear but the supply situation owing carrier shortage has enforced it. I fully appreciate the major plan and therefore that time is most essential. All my force are doing their level best to push on. I am confident that with the capture of the high ground at Eora Creek our entry into Kokoda and beyond will not long be delayed provided Alola is utilised as a dropping place. It is pointed out however that the track between Alola and Myola is the roughest and most precipitous throughout the complete route.

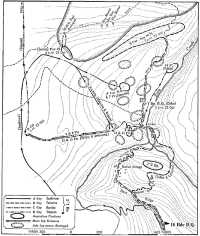

As cold and biting as this background which was developing on the highest military plane was the continuous rain which swept through the darkness above Eora Creek until 2.30 a.m. on the morning of the 23rd. Then a pale moon rose. Stevenson had sent Captain Gall,32 now commanding Brown’s company, to secure the bridgehead earlier in the night and Cullen took Captain Cox,33 his adjutant, and cautiously reconnoitred over the first bridge. They drew no fire. Cullen, quick to see the advantage of the situation, decided to try to pass his attacking company, Captain Barclay’s,34 over the bridges in the moonlight so that they would be in position to assault the main Japanese defences across the creek in the period immediately before and after the dawn. He hoped that the attack would coincide with one by Captain Sanderson from the left since Sanderson’s company had apparently not had time to get into position for an assault on the previous day. But he could not be sure that this would happen as his wireless sets were not working and he had no telephone cable. Thus Sanderson was completely out of touch as also was Simpson, struggling towards Alola.

On their reconnaissance Cullen and Cox had seen nothing of Gall’s company and had to accept the fact that the bridgehead had not been secured. It transpired later that Gall had tried an outflanking approach from the left with two platoons, in preference to a direct approach over the bridges, and had sent his third platoon to try a crossing on the right of the bridges. But the Japanese had been too alert for him so that he had been forced to swing wider across the creek up to the high ridges on the extreme left. Of the right flank platoon one section had succeeded in crossing and, under intense fire, was left clinging precariously below the Japanese positions to the right of the second bridge. Private Richardson35 of this section volunteered to carry back to Stevenson news of what had happened but was shot down before he had moved five yards towards the bridge.

With Gall’s company thus scattered Cullen pushed ahead his preparations for Barclay’s attack. While Cox remained forward at the first bridge learning more of the land the Intelligence officer was marking the track down to the first bridge with pieces of paper struck through with upright sticks. Only through some such expedient could Barclay’s men, heavily laden with weapons and ammunition, hope to make a reasonably silent way in the night down a narrow, steep and zigzag track which was alternately a clinging morass on the more level stretches and a treacherous slippery-dip on the slopes.

At 4 a.m. Barclay started downwards towards the creek. Apparently not expecting such an audacious manoeuvre the Japanese had relaxed their vigilance for Cox was able to guide the company across the first bridge safely. But only half were over the second bridge when the defenders woke to their presence. Now, however, the moon was down and it was dark. Sergeant Armstrong,36 commander of the third platoon, waited until the two leading platoons were clear of the bridge on the other side and then hurried his men safely across through the bullets which were cracking down from the heights. Barclay was fortunate to lose only two men wounded from his whole company in the crossing. But he was not so fortunate on the other side where numerous paths the Japanese had made in moving about the area confused his men. He had planned to move with the track as his axis, one platoon holding to it, the other two platoons to the right and left respectively. But the leading platoon, Lieutenant McCloy’s,37 swung too far to the left and Barclay followed with part of his company headquarters. Lieutenant Pollitt’s38 platoon, trying to keep to the right of the track, drifted too far in that direction in the darkness, and Sergeant Armstrong, in the rear, made the same mistake as McCloy and yawed too widely to the left.

On the right Pollitt’s men broke through a forward Japanese position and killed a number of the defenders. They continued then along the bank of the creek until the breaking dawn showed them moving into a dead-end defile. On their right the water foamed. On their left almost sheer rocks rose. They could do no more than cling to the positions they had won. This they did with the Japanese raining fire down on them and steadily wearing down their strength. And the fact that any continued to survive at all was probably due in large measure to the bravery of Lance-Corporal Hunt39 who climbed the slope and stalked several Japanese like a solitary hunter after deer and killed two of them.

Meanwhile McCloy on the left had similarly smashed through Japanese opposition in his initial movement, forcing his way some distance westward up a spur which ran to the creek junction from that direction. But

Barclay was killed there and, when dawn showed Armstrong’s platoon also on the lower slopes of the spur, McCloy assumed command of both platoons and prepared to attack northwards maintaining the direction which the track followed.

The ground was fairly open to the north, however, for some little distance--the floor of a basin which was enclosed on the east by the waters of the creek and, down the creek a little, by the craggy heights below which Pollitt’s men were fighting for their lives; shut in on the north by a spur which swept southwards to back the cliffs which held Pollitt; pressed on the west by the semi-circular sweep of the rough ground rising upward from the spur McCloy was holding in the area of the creek and the track, and linking the two spurs. It was as though a space somewhat less densely bush-covered than most of the valley, on the western bank of the creek, a few hundred yards long by two to three hundred wide, were enclosed by a horseshoe of high ground both ends of which rested on the northward running creek. Pollitt was under the northern tip of the horseshoe, McCloy was preparing to take the shortest route across the open end of the horseshoe from the southern tip. But the Japanese had positions sited on the floor of the basin, running up to the high ground on the west, and, beyond those, their main line on the heights which hemmed the basin on the north. McCloy found that he could not cross.

Then the morning air carried down from the Northwest the sounds of heavy firing. McCloy knew that Captain Sanderson’s men, whose attack had been delayed from the previous night, were trying to fight their way through to the crossing. But the high ground and thick bush of the horseshoe’s curve cut the newcomers off from sight and McCloy’s two platoons could do nothing to help. Soon, however, they saw two other platoons moving down the ridge towards them and Lieutenants Blakiston40 and Wyburn41 with their men joined them. There was no sign though of Sanderson and the rest. This, as it was learnt a little later, was their story.

After Sanderson had crossed the creek on the 22nd he had led his men very wide to the left of the main crossing to come in behind the Japanese positions sited for its protection. But rough country hampered the Australians, they had difficulty in negotiating a waterfall and matted vines and bush dragged at them. So it was that they were not in position to attack until the early morning of the 23rd. By that time they were Northwest of the crossing, on the right of the main Japanese positions which, from the high ground, faced southward across the basin towards the two bridges; and they were on the far side of the horseshoe from McCloy and his platoons. With the dawn they were moving down the heights towards the basin, a descent so steep that they had almost to swing down from tree to tree. Blakiston and Wyburn were on the right of the descent,

with Lieutenant Johnston’s42 platoon, with whom Sanderson himself was moving, on the left. The rough country separated Blakiston’s and Wyburn’s men from the rest and they drifted farther and farther to the right until they finished on the spur where McCloy was waiting. Sanderson and Johnston, meanwhile, had fought through opposition to reach the basin across which the forward Japanese positions were strung out towards the creek on the east. They engaged these but the Japanese held them off. As the fight went on more Japanese crept round the high ground above and behind the Australians until they were in such a commanding position that they could begin methodically to wipe them out with machine-gun fire. Sanderson, Johnston, and nine of their men were killed before the others of the platoon, most of whom were wounded, broke off the encounter and managed to make their way back into the rough country of the ridges. When Sanderson’s body was found later it was lying ringed by over 300 spent shells from the German Mauser which he had brought back with him from the Middle East.

While his two attacking companies had been thus beset Cullen had been trying to reach them with the two platoons which Captain Catterns had available. The Japanese commanded the track to the bridges, however, in the daylight and so whipped it with fire that Catterns could not use it. He swung wide to the right and it was not until about 11.20 a.m. that he had crossed the creek into the area between the two bridges, laying wire as he went. He then managed to cross the second bridge and, just beyond it, found a dead man, a wounded man and two men unhurt of the 2/3rd Battalion section which Captain Gall had had to leave there the previous night. As Catterns pushed on then into the basin, from the floor of which the Japanese, cut about by Sanderson, McCloy and the rest, had now withdrawn, Lieutenant Pollitt joined him with the survivors of his platoon who had been caught by daylight in the defile on the right of the track. Pollitt himself had been hit badly and his men carried their other wounded with them.

About 12.45 p.m. word came back to Catterns from his forward platoon, Lieutenant Body’s43: “The leading scout’s been bowled.” Body pressed doggedly on where the track rose steeply to cross the main ridge but soon had lost eight or nine men wounded. Catterns tried to outflank but could not do so. He could go no farther in the face of light and medium machine-guns, a mountain gun and mortars, firing from heights behind the northern side of the horseshoe. He spread his men across the track and well to the left of it where they began to dig in immediately below the defences.

Cullen then asked Lloyd for help. He said that a strong attack must be made on the Japanese right flank positions if his enemies were to be moved. Pending the arrival of this aid, he sent Lieutenant Leaney,44 who

joined him about 4 p.m. with the pioneer platoon, round Catterns’ left to attack the Japanese right. Leaney’s men did this although they numbered only eighteen. As Corporal Stewart’s45 section drove forward a medium machine-gun blocked them. One man fell dead, another wounded, to its fire. Stewart hurled a grenade into the position and plunged forward after the burst, pouring sub-machine-gun fire into the defenders, his men following him He himself was wounded, but the section wiped out the gun crew, put the gun out of action, and held the ground for ten minutes afterwards in the teeth of a furious fire which killed another of them and wounded yet another, leaving only two men unharmed in the little band. They withdrew then, the wounded Stewart helping another wounded man as he went. Before Leaney finally quitted the scene with those who were left of his men, he himself returned alone into the position the Japanese now held again to bring out another wounded man.

By this time it was almost dark. It had taken Leaney a long time in the rough country to mount and deliver his attack. This determined the Australians to delay until next day a further attack they were planning with Captain Lysaght’s46 company of the 2/3rd Battalion which had arrived about 5.15 p.m.

While the 2/1st had been fighting hard during this busy 23rd October, the 2/3rd, waiting to move in their rear, had been having a comparatively uneventful but anxious day. Stevenson was out of touch with two of his companies until the early afternoon; one which he had sent wide on the right of his positions, and Captain Gall’s. By nightfall, however, the right-flank company was on its way in without having come against any Japanese and it was known that Gall had linked with the remnants of Sanderson’s and Barclay’s companies. Meanwhile Lysaght had moved off at 4 p.m. to assist Lieut-Colonel Cullen under whose command he was temporarily placed.

The night of the 23rd-24th, therefore, saw something like stalemate threatening. Edgar was still holding his 2/2nd Battalion behind the high ground above Eora Creek village, waiting to advance when opportunity offered. He had lost men during the day from mortar fire. Stevenson, except for Lysaght’s company and Gall’s, was still holding forward to the right of Edgar and, like Edgar, had been enduring Japanese fire while he waited. Across the creek, and on the northern slopes of the basin, the 2/1st were in difficulties, tattered, and holding a position from which it seemed unlikely they could move forward and which was itself almost untenable. Their most forward troops, under Catterns, were almost under the very noses of the Japanese, not more than 30 yards from them and holed in like animals on a precipitous slope. From Barclay’s and Sanderson’s companies alone they had lost 3 officers and 17 men killed, and one officer and 25 men wounded. Even though they were strengthened during the night by the arrival of most of the balance of Headquarters

Company (except for the mortars and medium machine-guns which remained on the ridge above the village to give fire support from that area), and had Captain Lysaght’s company under command, they were still weak for any purposes and particularly weak for the circumstances in which they found themselves.

The night brought no rest. It was broken by intermittent firing and grenade bursts and covered desperate efforts to get rations and ammunition forward. The bulk of this work fell on those men of Headquarters Company who had been left back beyond the creek. All through the night these toiled forward and back again over a track that was narrow, slippery and steep, and swept by Japanese fire; on the return journeys they carried out the wounded.

That General Allen was hoping for a quicker result than now seemed likely was shown by the orders he had issued that day. He ordered Brigadier Eather to send the 2/31st Battalion on the way to Templeton’s Crossing with instructions to move on to Eora Creek on the 24th and come under Lloyd’s command. The 2/25th and 2/33rd were to be ready to go forward again next day. Allen’s intention was to use both his brigades for the capture of Kokoda. When the 16th Brigade had cleared Eora Creek it would move forward on the right of that stream with the 25th Brigade moving on the left. The task of the 16th would be to secure and operate a supply dropping ground at Alola, to seize the commanding features at Oivi and then, after mopping up between that area and Kokoda, junction with the 25th Brigade. It would push on then to establish bridgeheads over the Kumusi River at Wairopi and Asisi. The 25th Brigade would capture and hold Kokoda, prepare the airfield and protect and administer the supply dropping area.

But the morning of the 24th brought no renewed hope of a speedy execution of Allen’s plans. It confirmed Cullen’s belief that his own men would be doing well if they merely maintained their positions. Some were being hit by the intermittent Japanese mortar fire which was coming from about 150 feet above their positions and 300 yards distant. The Japanese had only to drop their fire among the treetops below, which they knew sheltered the Australians. The bombs usually exploded in the foliage and then scattered like shrapnel. Although a large percentage were duds, the sound of a bomb plopping among the high branches and slithering through the leaves towards the slit trenches was a sickening one to the men crouched below.

Lieutenant Frew47 provided an example of the difficulty of coming to grips with the enemy in that country. He sallied out with a patrol at dawn. As he climbed a ridge a rifleman was firing at him from above. So steep was the ridge that the first bullet, after just missing Frew’s head, went through his foot. The second hit him in the other foot. Frew then shot his adversary.

Colonel Cullen decided that only an attack by at least two companies

round the left flank offered any chance of success. He reported so to Brigadier Lloyd. About 10 a.m. he received word from Lloyd that Lysaght’s and another company of the 2/3rd would be sent on this mission. Later in the morning Stevenson passed through Cullen’s rear area with his own headquarters and Captain Fulton’s48 company and then, with Lysaght leading, moved round to the left to try to secure the high ground there. He was not long in provoking opposition and by 2.30 p.m. machine-gun and rifle fire was hampering his men. Lysaght’s men pushed on, however, cleared the immediate vicinity, and captured two light machine-guns in doing so. About the same time Fulton’s men brushed off a patrol and killed three of its members. Then Gall, who had linked his company again with the battalion, was pushed widest to the left. But the whole of the new movement having necessarily been slow and uneasy night came again without a decision.

For the men of the 2/1st Battalion the 25th was another day of holding on. It started badly. Back on the ridge above the village the medium machine-gun platoon had dug in their Vickers gun in the cold, wet darkness of the previous night with the intention of harassing the Japanese from that area. With the dawn, however, a Japanese field gun opened from the heights opposite and scored a direct hit on the Vickers, blowing the gun out of its pit and causing casualties among the crew—an additional lesson to the Australians of the completeness of the Japanese observation of even their rearward positions. Later in the morning two friendly aircraft tried to strafe the Japanese positions but their fire fell too far back to affect the immediate issue.

From their forward positions Catterns’ men were sniping and grenading to the full extent of their limited supplies of ammunition. On the battalion’s left Leaney was active. With his few men he drove at a forward Japanese post, killed three of the defenders and wounded others, and consolidated again in advance of his original positions.

During the afternoon a party which had been searching for a mortar observation post to the east of the creek located a suitable site. Line was laid and other preparations made to bring the mortar into action from the village ridge next day. Meanwhile, however, Japanese mortar fire continued to fall on the Australians in both the forward and rearward positions.

In the 2/3rd’s area skirmishes and fire from both sides marked the day as the main body edged farther to the left and felt round the Japanese right flank, continuing the grim game which Gall’s men had begun there after they had been forced wide on that side on the morning of the 23rd. A member of that company said later:

The Japanese had the good sense to establish this forest fort on the only water to be found on the ridge. Consequently, for the four [sic] days before support arrived, the men of the company had to catch rain water in their gas capes and drink water from the roots of the “water tree”. Their only food was dehydrated emergency ration, eaten dry and cold. Every time patrols from the company located one of the outlying Japanese machine-gun posts, scouts were killed or wounded.

Then the post would be outflanked and overrun with Brens, Tommy-guns, and grenades, but each night the attacking parties had to withdraw to defensive positions, and, in the darkness, the Japanese would re-establish the posts or put out others. The Japanese snipers were alert and were good shots. When an Australian patrol had been pinned down by fire, it would not be long before a man would fidget, thrusting a hand or arm or leg out of the cover, and would be hit, perhaps from twenty-five yards.

The 2/3rd lost 4 men killed and 12 wounded on the 25th.

The next morning was marked for Cullen by a similar misfortune to that which had marked the 25th. Early in the day the mortar went into action. Though, as was subsequently discovered, the rounds fell with effect in the main enemy positions, the success was costly, for a Japanese mortar or gun replied almost at once and scored a direct hit on its target. Sergeant Madigan49 then carried his wounded officer to the medical aid post under heavy fire, quickly secured another weapon, gathered replacements for others of the crew who had been badly hit, and continued the fight.

On this same morning of the 26th the two worn-out companies which Barclay and Sanderson had commanded in the original attack on the 23rd were once more with the battalion, and with them Captain Simpson’s company which had set out for Alola on the 22nd. Simpson said that he had reached a position just above Alola and, with grenades and sub-machine-guns, had surprised Japanese there in a bivouac area. Although he had lost two men in the fighting which followed he knew that his company had killed at least six Japanese out of a larger number of casualties. A counter-attack from the flank and shortage of rations had forced his withdrawal. Cullen now sent him round to the extreme left of the positions beyond Leaney’s pioneers (near whom Sergeant Miller50 with a 2-inch mortar carried on a most effective little private war with the Japanese during the afternoon). With Simpson, went the company that had been Captain Barclay’s, now commanded by Lieutenant Prior51 and later in the day taken over by Captain Burrell.52

By that time, in his efforts to advance, Stevenson had moved the 2/3rd farther to the left and out of contact with the 2/1st. He was still struggling to round the flank and break into the main Japanese positions. But an attack by Lysaght thrust directly into medium machine-gun fire and could achieve no effect. Gall and Fulton swung round Lysaght later in the afternoon but made no marked gain. Sergeant Copeman53 thrust into the Japanese positions with a patrol and cut a gap in their telephone line. Then, irritated by the Australian efforts, the defenders counter-attacked

against Lysaght and Gall at last light. Although the attack achieved some little local success against one of Lysaght’s platoons it lost its momentum and a quiet night began in the 2/3rd’s area.

But, although the forward commanders might consider that their efforts to resolve their difficulties had been intense, neither General MacArthur in Australia, nor General Blamey in Port Moresby, shared their views. That day Blamey had signalled Allen referring to their previous interchange of messages:

Your 01169 of 22 Oct does NOT confute any part of General MacArthur’s criticism in his message sent to you on 21st. Since then progress has been negligible against an enemy much fewer in number. Although delay has continued over several days attacks continue to [be made] with small forces. Your difficulties are very great but enemy has similar. In view of your superior strength energy and force on the part of all commanders should overcome the enemy speedily. In spite of your superior strength enemy appears able to delay advance at will. Essential that forward commanders should control situation and NOT allow situation control them. Delay in seizing Kokoda may cost us unique opportunity of driving enemy out of New Guinea.

General Allen replied:

One. Every effort is being made to overcome opposition as quickly as possible. Present delay has [caused] and is causing me considerable concern in view of its probable effect upon your general plan. Jap however is most tenacious and fighting extremely well. His positions are excellent well dug in and difficult to detect. I feel it will be necessary to dig him out of present positions since his actions to date indicate that a threat to his rear will not necessarily force him to retire. I have already arranged for 2/31 Bn to assist 16 Bde 27 Oct but it must be realised it would take 36 hours to get into position. Owing to precipitous slopes movement in this particular area is extremely difficult and a mile may take up to a day to traverse. I had hoped that 16 Bde would have been able to clear enemy position today. Two. As I feel that a wrong impression may have been created by our sitreps I must stress that throughout the advance a brigade has always been employed against the enemy but up to the present this has been the maximum owing supply situation. Three. Jap tactical position at present is extremely strong and together with the terrain is the most formidable up to date. No accurate estimate can be given of Jap strength except that commander 2/3 Bn reports that at least one battalion opposes him alone. Four. You may rest assured that I and my brigade commanders are doing everything possible to speed the advance.

Even had he known of this exchange Lieut-Colonel Cullen’s mounting impatience with the delay could scarcely have been intensified. On the 27th he decided to move his own headquarters into the left flank area where Leaney, Burrell and Simpson were, with the intention of organising really heavy pressure there. But scarcely had his headquarters reached their new site than word came from Catterns that the Japanese had withdrawn on his front. Having ordered Burrell and Simpson to push hard on the left Cullen then quickly returned to the vicinity of the track intending to follow Catterns’ advance. But it soon became clear that his opponents had merely pulled back some 500 yards to make their positions even more compact. Catterns was again held, and although Burrell and Simpson beat at the Japanese right flank, so that they killed and wounded numbers of the defenders, they made no substantial advance and lost men.

Thus the situation was growing hourly more wearisome. When a company from the 2/2nd took over their duties the details whom Cullen had left on the eastern bank of the creek came into the 2/1st area on the 27th, so that, for the first time at Eora Creek, almost the whole battalion was then concentrated. This was the first time, too, since the fighting on the 23rd that Captain Sanderson’s old company was able to take the field again as a formed sub-unit. Now Lieutenant Wiseman54 was in command.

As night came again Colonel Cullen knew that a kind of torpor was clogging the minds and bodies of his men. The will to fight and win, the intangible “morale” was still high, but worn bodies could no longer raise speed in execution of the plans which came only painfully and slowly to tired minds Catterns’ men, still in the most advanced positions, for they could not be relieved, were suffering most as they clung like leeches to the rough slope. They were always wet from the cold, driving rain and, added to the shortness of their rations, was the virtual impossibility of cooking food for themselves or making even a drink of hot tea. They were only 40 yards from their enemies and, if they ventured to light fires, the smoke drifted above the trees and became target indicators for the Japanese mortarmen. By day they could not move out of the two-man pits in which they crouched, and only at night could they go about their essential tasks of getting up food and ammunition; and darkness merely minimised and did not do away with the risks of movement in their bullet-swept areas. Their numbers were being reduced by the constant fire which swept their positions and the bursting of the grenades which their enemies rolled down on them from the heights. None the less they clung to their positions and resolutely beat back the frequent patrols which the Japanese sent to harass them.

Also, for the 2/1st, misfortunes were added to the normal hazards of battle. In the early hours of the 26th, when rain had lashed down in sheets and turned the already turbulent waters of the creek into a raging torrent, the bridge had carried away. But its broken timbers caught against some rocks a little farther downstream so that determined men could cross by bracing themselves against the wreckage. All supplies then had to come forward, all the dead weight of the helpless wounded then had to be carried back, through the bitterly cold mountain waters foaming down the cold and windswept darkness and whipped by plunging fire. Here it was that a brave priest, Chaplain Cunningham,55 who joined the 2/1st only on the 27th, distinguished himself, helping to bear the wounded through the dangerous waters, comforting the dying and burying the dead regardless of creed.

While a sub-section of the 2/6th Field Company, helped by infantrymen, was still trying to repair the damage to the bridge, in the dusk of the

Eora Creek, 27th–28th October

27th, another misfortune came. From its positions behind the village ridge the 3-inch mortar went into action. It quickly got thirteen rounds away but the fourteenth, the second of a supply that had been dropped from the air, exploded in the barrel and killed three of the crew.

Meanwhile the 2/3rd Battalion, still working round the high ground on the extreme left, were also chafing against the stubborn circumstances that were holding them. Early in the morning of the 27th Colonel Stevenson, suffering pain from his wounded ear, handed over his command to Major Hutchison. The latter, a short, thick-set young man who had been

with the battalion from its inception, whose deliberate manner suggested the possession of a brain which, having decided upon a plan of action, would follow it through to the bitter end with bulldog fixity of purpose, decided then that he would resolve the situation. He determined that his men should comb the spur, methodically rooting out and killing any who barred the way into the main Japanese positions from the right of those positions. With Captain Brock’s56 company of the 2/2nd under his command, in addition to his own battalion, he formed three columns and ordered them to move forward at a distance of about 300 yards from each other. They would halt after they had gone about 1,000 yards and get in touch with one another so as to maintain an unbroken front in their advance.

At 8.50 a.m. on the 27th the movement began. At 11.30 Brock’s column, moving on the right, met the enemy and lost men in the sharp give and take which followed. Then a patrol from Lieutenant McGuinn’s57 company, moving as the central column, clashed against a determined party and lost 1 man killed and 4 wounded. McGuinn, realising that he was up against a stronger position than he had at first appreciated, asked for assistance. Hutchison told Captain Fulton to attack in cooperation with McGuinn; but night came before the attack could go forward.

From first light on the 28th action began to boil along the whole Australian front. In their positions spreading from the track leftwards Catterns’ dazed and hungry men could do no more than cling where they were. Grenades, bowled down from above, accounted for five more of them during the afternoon. Farther to the left Japanese were thrusting into Burrell’s area with patrols which cut the company’s telephone wires and stimulated Burrell’s men to sharp reaction which flung the invaders out again. Farther left again Simpson’s pressure had forced the Japanese back but provoked them to counter-attack which, although it cost them men, cost Simpson casualties also. As opposing patrols moved in and around both Burrell’s and Simpson’s areas, and in the open space between the two, a grim game of blind man’s buff developed. The searchers on either side could normally not see more than some 10 yards ahead of them in the thick bush and neither of the two Australian companies concerned was sure of the other’s position. So a sort of murderous confusion set in.

Meanwhile the 2/3rd made deliberate preparations, which were completed by the middle of the afternoon. Captain Fulton had been placed in command of a combined force consisting of his own and McGuinn’s companies. At 5 p.m., after a barrage of rifle grenades, McGuinn struck downhill from the left and Fulton’s own company, soon afterwards, struck from the right so that the Japanese right-flank positions were caught between the two. Despite a hail of defending fire from strong positions the Australians’ ferocity increased.

We sailed into them firing from the hip (said Lieutenant MacDougal afterwards). ... The forward scouts were knocked out, but the men went on steadily, advancing from tree to tree until we were right through their outlying posts and into the central position. Suddenly the Japanese began to run out. They dropped their weapons and stumbled through the thick bush down the slope, squealing like frightened animals. In a minute or two the survivors had disappeared into the bush. We buried well over 50 Japs next morning, though our own casualties were fairly light and there must have been other Japanese dead in the bush that we didn’t find. Some of the dead Japanese were wearing Australian wrist watches. Before this Eora Creek fight the men had been saying that the Japanese wouldn’t run. Eora Creek proved that he would.

During the action Corporal Pett,58 “five feet of dynamite”,59 as a diarist described him, distinguished himself by knocking out four machine-gun posts single-handed.

Hutchison’s men had leisure then to examine the positions which had held them up for so long. These were based on a sort of central keep about 300 yards across. Radiating from this central position in four or five directions were outlying machine-gun posts. Although the Japanese shrewdness in locating themselves on the only water to be found on the ridge had increased considerably the physical discomfort of the Australians during the preceding days, it had not represented all profit for the defence. For the first time in their struggle against the 16th Brigade the Japanese had not occupied the highest ground in the area and this had finally allowed Hutchison to get above them, an important factor in his final success. Obviously they had been in this position for a considerable time and, in a storehouse which it contained, the Australians found equipment of all kinds including machine-guns, mortars, a wireless set and informative papers. A physical check on the morning after the battle revealed 69 dead bodies and there were certainly others which remained unfound and unaccounted. The day cost the 2/3rd Battalion 11 men killed and 31 wounded.

The turning of the Japanese right flank by the 2/3rd Battalion meant the end of the Japanese resistance at Eora Creek. On the morning of the 29th patrols of the 2/1st Battalion found the defences down and they walked unopposed into the positions before which they had spent themselves so bitterly for almost a week. The battalion then took up the pursuit along the track with the 2/3rd moving on their left and the 2/2nd in rear. There would be no more fighting for either the 16th or 25th Brigades during the last three days of October, but that which they had already done was only a prelude to days of blood and battles which lay ahead.

The Japanese, although beaten in the mountains, were making for their base on the north coast and they could be expected to fight stubbornly there. By the time General Horii reached Ioribaiwa he was at the end of his resources and his thin supply line across the range could no

longer support him, partly because the mountains were too rugged, partly because of the attacks by American and Australian aircraft, which did their most effective work at the Wairopi crossing where they destroyed the bridge as fast as the Japanese rebuilt it. At Ioribaiwa the Japanese commander received the last of a series of changing orders each of which had pared down his objective. When he developed his main attack before Isurava on 26th August he was told to press on to Port Moresby. Difficulties at Guadalcanal and disaster at Milne Bay, however, caused Imperial General Headquarters, at the end of August, to order General Hyakutake to instruct Horii to assume defensive positions as soon as he had crossed the main Owen Stanley Range and, in accordance with these orders, Horii selected Ioribaiwa as the area in which to stand. While he was approaching this point, however, the Kawaguchi Force was virtually destroyed on Guadalcanal. The Japanese High Command then felt that it should concentrate all its energies in the Pacific on retaking Guadalcanal particularly as the extent of the reverse at Milne Bay was then clear. In New Guinea, therefore, Horii’s men were to fall back to the more easily defended Buna–Gona beachhead area. After the Guadalcanal situation was retrieved the main Japanese effort would be directed against New Guinea and, in concert with a fresh move to seize Milne Bay and another coastwise approach to Port Moresby, Horii would once more cross the mountains

To implement this plan Horii allotted the rearguard role to Colonel Kusunose’s 144th Regiment, which prepared to hold at Ioribaiwa with two battalions and some supporting troops while the rest of the force fell back. The main body of the 41st Regiment (less elements which were given a role along the track) were to fall right back to the coast to make firm there the positions to which the rest of the beaten troops could retire. In accordance with this plan Colonel Yazawa moved swiftly and was already back at Giruwa when the Australians struck their main blow at Ioribaiwa on 28th September. By that time also (for what reasons it is not certain but probably because the heart had gone out of them) the units of the 144th Regiment had left their rearguard positions at Ioribaiwa and were intent on keeping as far ahead of the advancing Australians as possible.

Of the retreat across the Owen Stanleys a Japanese war correspondent (Seizo Okada) has written:60

In one of the small thatched huts which we had hastily built on the mountain side [at Ioribaiwa], Sato and I had just finished our usual scanty evening meal of sweet potatoes, when we scented some important change in the situation. We hurried out to see Major-General Horii in his tent that stood on a little uncovered elevation. On a thin straw mat in the tent the elderly commander was sitting solemnly upright on his heels, his face emaciated, his grey hair reflecting the dim light of a candle that stood on the inner lid of a ration can. Lieut-Colonel Tanaka, his staff officer, sat face to face with him also on a mat. Two lonely shadows were cast on the dirty wet canvas. ... The staff officer was silent, watching the burning wick of the candle as though to avoid the commander’s eyes, when a rustling sound was heard in the thicket outside and the signal squad commander came in with

another wireless message. It was an order from the Area Army Commander at Rabaul instructing the Horii detachment to withdraw completely from the Owen Stanleys and concentrate on the coast at Buna. This message was immediately followed by a similar order that came directly from the Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo. It was now beyond doubt that the order had been authorised by the Emperor himself His Majesty’s order had to be obeyed. It is true there was a strong body of opinion among the hot-blooded battalion commanders advocating a desperate single-handed thrust into Port Moresby. But Staff-Officer Tanaka remained cool, and reasoned with them saying that it was a suicidal action even if everything went well except the supply of food, which was in a hopeless condition.

The night was far advanced. It had begun to drizzle, softly. The headquarters was in confusion sending out messages to the front positions instructing them to make preparations for immediate withdrawal. ... The order to retreat had crushed the spirit of the troops which had been kept up through sheer pride. For a time the soldiers remained stupefied among the rocks on the mountain side. Then they began to move, and once in retreat they fled for dear life. None of them had ever thought that a Japanese soldier would turn his back on the enemy. But they were actually beating a retreat! There was no denying that. As soon as they realized the truth, they were seized with an instinctive desire to live. Neither history nor education had any meaning to them now. Discipline was completely forgotten. Each tried for his life to flee faster than his comrades.

Our movement was evidently reported by a scouting plane. On the morning of the fourth day, after the front-line units had begun to move back, the Australians took up the pursuit. Our party, and small independent units, went down without bothering about anything; but the headquarters unit was constantly delayed by the sick and wounded whom they had to pick up on the way. At each key-point there was a platoon of the Yokoyama Engineer Unit, who waited for the last of our men to pass and blew up the cliffs or cut off the log-bridges to delay the Australians in pursuit. But the pursuit grew hotter every day, until the enemy were close upon our heels. At the same time, attacks from the air by American planes became more vigorous. ... The roar of propellors that seemed to burst our eardrums and pierce our intestines, the ratatat of the machine-guns, the sound of cannon fire that streamed forth from tails of B-17s—these were nightmares threatening us in our miserable retreat. Moreover, the soldiers were short of food necessary to keep themselves from starvation. On our way forward we had gathered a pretty good crop of taroes, but now we could find none at all. Even the fields more than ten kilometres away from the track had been dug up all over almost inch by inch. From time to time we came upon large fields extending over the side of a mountain, but we could not find a single piece of potato in them. As for papayas, the stems themselves had been rooted out and bitten to the pith. Here and there along the path were seen soldiers lying motionless, unable to walk any longer in the excess of hunger and weariness.

One day, towards evening, we came to the ravine where the fierce fighting had taken place. It was in the remotest heart of great masses of mountains about midway across the Owen Stanley Range, and was deeper and larger than any other ravine we had passed. The dark path through the enormous cypresses ... seemed to lead down to a bottomless pit. A rumbling sound like drumbeats came, it seemed, from somewhere deep underground. We rounded a rock, and saw a furious white serpent of water falling from a height of about a hundred feet and making roaring noises among the cavernous rocks below. The humidity here was very high, mosses hanging in bunches on the trunks of trees. We stepped across the edge of the seething basin, and followed the path leading further down through thick growths of bamboo-grass that glistened like wet green paint. The branches overhead were so closely interwoven that not a ray of sunshine came through. There was neither day nor night in that ravine; it was always pale twilight, and everything looked as wet as though it were deep under water. And in that eternal twilight lay numberless bodies of men scattered here and there. ...

At Mount Isurava which stood at the northern end of the path across the Owen Stanley Range the narrow path was congested with stretchers carrying the wounded soldiers back to the field hospital on the coast. There were so many of them that they had been delayed here since the wholesale retreat began. Some of them were makeshift stretchers, each made of two wooden poles with a blanket or tent-cloth tied to them with vines and carried by four men. They made slow and laborious progress, constantly held up by steep slopes. The soldiers on them, some lying on their backs, emitted groans of pain at every bump. In some cases, the blood from the wounds was dropping through the canvas or blanket on to the ground. Some looked all but dead, unable even to give out a groan.

Nevertheless, whatever despondency may have been in the hearts of the retreating Japanese, their rearguards fought vigorously at Templeton’s Crossing and Eora Creek once they had decided to make a stand. At Eora Creek the third battalion of their regiment joined them. Thus Kusunose mustered there a regiment, which had been much reduced by heavy casualties and sickness and weakened by the mountains and hunger, in strong and carefully selected defensive positions, and measured them against a fresh Australian brigade which had been weakened by the mountains but not yet reduced to any extent by battle.

By the time the Eora Creek fighting came to an end the 16th Brigade had lost between 250 and 300 officers and men killed and wounded.61 For slightly more than every two wounded one was killed. This unusually high proportion of killed to wounded was the measure of the closeness of the fighting.

These casualties can be interpreted properly only in relation to the type of fighting which produced them. It was fighting in the now familiar pattern of bush warfare in tumbled mountains—by individuals pitted against one another, by small groups meeting and killing in sudden encounters among the silently dripping leaves and tangled quiet of the high rain forests; but with the first loud sounds of a new note being struck as Australians came against Japanese in ideal defensive positions which the latter manned strongly as a result of long preparation, and from which they fought most tenaciously. How effectively had Lloyd’s men met the comparatively new challenge of ideally sited mountain defence? Certainly with courage and energy, as witness their frontal attack over the bridges which their enemies were sited to command. But it seems possible now that, in that manoeuvre, there was more courage and energy than skill;

that Stevenson’s and Cullen’s initial doubts about that plan were well founded. The positions had finally been turned from the Japanese right flank. Had one battalion, at least, followed in Captain Sanderson’s path and felt out the Japanese carefully there for a day or two before attacking, it seems likely that the engagement at Eora Creek would have been less drawn out and less costly.

And then again, if Colonel Cullen had persisted with his plan on the 27th of driving against the Japanese from his own left-flank positions with all the strength that he could muster there, it is possible that immediate success would have followed. He found later that the point at which he planned to throw his men was merely a strong link between the main positions and the Japanese right flank positions which Hutchison’s men overran the following evening. It was the Japanese recession which caused him to change his plans.

For the gallant and capable General Allen himself Eora Creek meant the end of his service in the mountains. This message from General Blamey reached him on the 27th:

Consider that you have had sufficiently prolonged tour of duty in forward area. General Vasey will arrive Myola by air morning 28 October. On arrival you will hand over command to him and return to Port Moresby for tour of duty in this area. Will arrange air transport from Myola forenoon 29 October if this convenient to you.

Allen replied:

it is regretted that it has been found necessary to relieve me at this juncture especially since the situation is improving daily and I feel that the worst is now behind us. I must add that I feel as fit as I did when I left the Base Area and I would have preferred to have remained here until my troops had also been relieved.62

But General Vasey arrived at Myola on the 28th and, on the 29th, Allen left for Port Moresby. Later, in Australia, he had the opportunity of speaking to General MacArthur to explain the conditions and he told MacArthur how much his signals had distressed him. In real or assumed surprise MacArthur said: “But I’ve nothing but praise for you and your men. I was only urging you on.” Allen answered drily: “Well, that’s not the way to urge Australians.” He was cheered, however, by MacArthur’s intimation that he had important work yet for him to do.

It was natural that Allen should feel aggrieved. He was a devoted soldier of wide experience in two wars who had demonstrated his ability in field command in every rank from that of platoon to divisional commander. He felt that neither MacArthur, nor Blamey, nor Herring could really

appreciate the conditions under which he had been fighting as none had set foot on the Kokoda Track itself beyond the end of the motor road near Owers’ Corner. Perhaps the disadvantages of that could have been overcome in some measure through the use of competent and experienced liaison officers—and indeed General Allen was too experienced a modern soldier not to realise that a theatre commander must rely largely on that and similar means to develop a picture denied generally to his own eyes by the demands of the desk from which necessarily he must discharge most of his responsibilities. But he noted that, up to 22nd October when Lieut-Colonel Minogue arrived at his advanced headquarters at Myola on a liaison mission, no senior staff officer from the headquarters of any one of his three superiors had visited his forward area to examine conditions at first-hand.