Chapter 11: The Build-Up Before Buna

AT the end of October General MacArthur’s immediate plans were by no means precisely defined. He had attained his objects in preparation for offensive action in the South-West Pacific: his forces controlled the crest of the Owen Stanley Range from Wau to Milne Bay and had crept round the north coast of New Guinea to Cape Nelson; they had the islands surrounding Milne Bay under surveillance; their base installations at Port Moresby, Milne Bay and (in Australia) in the Cape York Peninsula, were essentially complete; air power was concentrating in New Guinea and northern Australia. But the general situation beyond those limits was such as to give the Allied commander cause for wary consideration.

The seas to the north of Australia, and the Pacific Ocean adjacent to the northern Solomons, the Gilberts, Marshalls, Carolines, Marianas and Philippines, were under undisputed Japanese control. The main Japanese fleet was concentrated in the Truk–Rabaul–Jaluit triangle. Large Japanese forces, mobile, well-equipped and experienced, were within striking distance of MacArthur’s area. An intense offensive against the Americans on Guadalcanal was under way. The American fleet in the southern Solomons was weaker than the neighbouring Japanese fleet and needed the protection of land-based aircraft. It was unable—or unwilling—to assist in any action in the South-West Pacific at that time, and the naval forces available to the commander of that area were vastly inferior to those of his opponents in ships of all classes. The demands of Europe were not likely to permit replacement of heavy losses in MacArthur’s personnel or equipment and would impose a long delay on any program for remedying existing deficiencies.

On the other hand the Japanese air forces which had been concentrated in great strength in the Rabaul–Kavieng–Buin area had suffered such heavy reverses that the Allies had aerial superiority over New Guinea and, usually, over the southern Solomons. They were able to deliver punishing attrition attacks to shipping and land objectives in the northern Solomons, New Britain and New Ireland. The Americans felt that they were superior to their opponents in both training and equipment; the Australian Air Force, while experienced and well-trained, did not have enough first-class aircraft. None the less Guadalcanal was demonstrating that air power alone could not prevent invasion by sea even though the Americans there, with a higher proportion than MacArthur of land-based dive bombers, were better fitted to deal with such manoeuvres than MacArthur was with his larger proportion of high-level bombers.

Generally the defenders of the South-West Pacific were not in a position to engage their enemies in a battle of attrition. It was clear that the invaders still had such impetus that they could strike heavy blows at Guadalcanal, or along the north coast of New Guinea or against Milne

Bay; or combine two of these courses; or combine a most exacting defence at either Guadalcanal or on the north coast of New Guinea with an attack, that would be most difficult to sustain, on the remaining area or at Milne Bay.

Having considered these circumstances General MacArthur decided on the 3rd November that he would immediately drive through the plan already under way in New Guinea—a three-column advance against Buna—provided that New Guinea Force could so order its supply program as to place ten days’ supplies behind each column. The attacks would coalesce about 15th November (certainly not earlier than the 10th) but the actual date would depend upon developments. He reserved his decision whether he would attempt to consolidate and hold at Buna after its reduction.

This would depend to a large extent upon events at Guadalcanal. There it was still anybody’s fight. Despite the failure of their October offensive, it was clear that the Japanese were still capable of carrying the American defences by storm; the naval battle of Santa Cruz had not strengthened the American position at sea; on 26th October only 29 American aircraft were operational at Henderson Field.

Thus far in the campaign, Allied air and naval forces had fought valiantly, but had not yet achieved the result which is a requisite to a successful landing on a hostile island—the destruction or effective interdiction of the enemy’s sea and air potential to prevent him from reinforcing his troops on the island, and to prevent him from cutting the attacker’s line of communication.1

When, on 18th October, Admiral Ghormley had been replaced by the picturesque and forceful Admiral Halsey, the first decision Halsey had to make was whether or not Guadalcanal should be abandoned. General Vandergrift said that he could hold the island if he were given stronger support. This decided Halsey, who promised Vandergrift what he asked. One of his first actions was to send Admiral Kinkaid to fight the Santa Cruz battle.

Meanwhile the Joint Chiefs of Staff were preparing stronger air forces for the South Pacific and President Roosevelt himself had intervened. On 24th October he wrote to the Joint Chiefs that he wanted every possible weapon sent to Guadalcanal and North Africa even at the expense of reducing strengths elsewhere. Admiral King assured him that strong naval forces would meet his request. (These included twelve submarines from General MacArthur’s area.) For the Army General Marshall replied that Guadalcanal was vital.

The ground forces in the South Pacific were sufficient for security against the Japanese, he felt, and he pointed out that the effectiveness of ground troops depended upon the ability to transport them to and maintain them in the combat areas. Total Army air strength in the South Pacific then consisted of 46 heavy bombers, 27 medium bombers, and 133 fighters; 23 heavy bombers were being flown and 53 fighters shipped from Hawaii to meet the emergency. MacArthur had been directed to furnish bomber reinforcements and P-38 replacement parts to the South Pacific. General Marshall had taken the only additional measures

which, besides the possible diversion of the 25th Division from MacArthur’s area to the South Pacific, were possible—the temporary diversion of three heavy bombardment squadrons from Australia to New Caledonia, and the release of P-40’s and P-39’s from Hawaii and Christmas Island.2

Halsey, therefore, was strongly backed as he pushed his plans ahead. Late in October he diverted the I Battalion, 147th Infantry, from another operation of dubious value to cover, with the 2nd (Marine) Raider Battalion and lesser elements, the construction of an air strip at Aola Bay, about 33 miles east-South-east of Lunga Point. (These made an unopposed landing there on 4th November, but the project was subsequently abandoned because of the unsuitability of the terrain.) In Vandergrift’s original area two ships were to land more stores, ammunition and two batteries of 155-mm guns on 2nd November. These guns were heavier than any the garrison had yet possessed and would, for the first time, make effective counter-battery fire possible. On 3rd November the 8th Marines of the 2nd Marine Division were to land. More reinforcements would land about a week later—principally the 182nd Regimental Combat Team (less the III Battalion) from General Patch’s Americal Division at Noumea, to which the 164th Infantry, already on Guadalcanal, also belonged.

These plans were still being executed when General Vandergrift thrust once again across the Matanikau River somewhat as the marines had done early in October. At daybreak on 1st November the first phase of a lavish support program opened: artillery, mortars, aircraft and naval guns combined to beat down opposition in front of the advancing marines. When light came the attack had made about 1,000 yards.

On the 2nd the advance continued and three marine battalions trapped the defending Japanese at Point Cruz. There was bloody work with the bayonet there before the surviving Japanese were driven into the sea, leaving behind some 350 dead, twelve 37-mm guns, one field piece and thirty-four machine-guns. Next day Colonel John M. Arthur pressed still farther ahead with two battalions of his own 2nd Marines and the I Battalion of the 164th Infantry. By the afternoon he was about 2,000 yards west of Point Cruz though still more than two miles short of Kokumbona. There Vandergrift halted him East of the Lunga a new Japanese venture seemed to be burgeoning at Koli Point.

The Americans had correctly forecast this new move and the II Battalion of the 7th Marines, hastily moving eastwards, had established themselves east of Koli Point and just across the mouth of the Metapona River, by nightfall of the 2nd. They knew that some Japanese survivors of the previously unsuccessful attempts on the Lunga perimeter were already nearby. In the rain and early darkness of that night a Japanese cruiser, a transport and three destroyers loomed offshore about a mile farther east and landed men and supplies. Next morning the II/7th Marines found themselves hard pressed by a westward thrust from that

position, fell back some distance, and crossed the Nalimbiu River to hold from its western bank. Meanwhile, American and naval units had been turned loose on this new threat; the I Battalion of the 7th Marines was hastily embarking on a small craft to the aid of the other battalion; the 164th Infantry (less a battalion) was preparing to set off overland from the Ilu River to contain the Japanese left south of Koli Point.

By 4th November Brigadier-General William H. Rupertus, who had been allotted immediate responsibility for the new sortie, had reached Koli Point with the water-borne reinforcements; the 164th and a company of the 8th Marines were moving eastwards; the 2nd Raider Battalion, just arrived at Aola Bay, was ordered to push westward towards Koli Point. The Americans thus, taking no chances, were in a most favourable tactical position, with a force strong enough to deal with a really serious threat.

Night of 7th November saw them defensively located about one mile west of the mouth of the Metapona. On the 8th the two Marine battalions and the II Battalion of the 164th located and almost encircled the main Japanese positions on the east bank of Gavaga Creek which paralleled the Metapona just to the east. General Vandergrift then withdrew part of the force, in order to press home new attacks he had planned against Kokumbona on the other side of the Lunga. As these left on the 9th, the remaining Americans closed their trap more firmly until they held a curved line from the beach on the east bank to the beach on the west bank of the sickle-shaped bend at the mouth of Gavaga Creek, with only one gap—at the southern extremity—where two companies of the 164th had failed to link. Through this gap many of the Japanese apparently escaped while others had withdrawn inland earlier. After another three days, however, the Americans had cleared the remaining pocket. They then reported that they had killed 450 for the loss of some 40 of their own men killed and 120 wounded.

Before this climax had been reached at Koli Point General Vandergrift had once more resumed his drive west of the Matanikau. On 10th November Colonel Arthur led out a strong force from Point Cruz (to which he had drawn back from the most westerly limit of his previous advance). By midday on the 11th they were just past the line of the penetration of 4th November. Vandergrift then had word that large, fresh invading forces were on their way by sea against him. He would need his whole force concentrated in the Lunga area. He therefore once more ordered Arthur to disengage. This the latter did so swiftly that his whole force was back across the Matanikau on the 12th. The Americans then destroyed their bridges and packed their ground forces tight within their main perimeter while they awaited the results of the efforts of their navy and air to keep the new invasion from the island.

By this time they had a fairly complete picture of the assemblage of ships in the harbours Truk, Rabaul, Buin—an unfailing barometer of Japanese intention. Scouting aircraft had reported a great many transports and cargo ships and, in addition, 2 aircraft carriers, 4 battleships, 5 heavy cruisers and 30 destroyers. In contrast Admiral Halsey’s main force consisted of

24 submarines (which had destroyed a number of ships along the Japanese sea lanes to Guadalcanal), one aircraft carrier, 2 battleships, 4 heavy and one light cruisers, 3 light anti-aircraft cruisers, 22 destroyers and 7 transports and cargo ships. These were in two task forces, one under Admiral Turner responsible for the defence of Guadalcanal and the transport of troops and supplies to the island, and a carrier force at Noumea under Admiral Kinkaid (to support Turner as necessary) consisting of the carrier Enterprise, 2 battleships, one heavy and one anti-aircraft light cruiser and 8 destroyers.

Turner divided his force again into three groups. One, a transport group under his own direct command, moving out of Noumea to Guadalcanal with reinforcements and supplies, was to be covered by a second, under Rear-Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, operating from Espiritu Santo. The third, under Rear-Admiral Norman Scott, like Callaghan’s operating from Espiritu Santo, was to bring fresh troops and supplies from that island to Guadalcanal.

On 8th November Turner’s four transports, escorted by two of Callaghan’s cruisers and three of his destroyers, stood out from Noumea and rendezvoused with the rest of Callaghan’s warships off San Cristobal on the 11th. Meanwhile, closely guarding three transports, Scott had arrived off Guadalcanal early that morning. Japanese bombers made the day an uncomfortable one for him and, with the coming of night, he withdrew from the immediate vicinity of Guadalcanal. Later he linked with Callaghan and Turner. Dawn of the 12th found all the transports busily unloading at Lunga Point with the warships standing offshore. Turner, expecting the arrival of a fresh Japanese fleet, was anxious to get the seven transports emptied and away again as soon as possible. But unloading was interrupted about the middle of the afternoon when some 25 torpedo bombers swept at the ships. Callaghan’s flagship—the cruiser San Francisco—and the destroyer Buchanan were hit but none of the transports were damaged. Most of the attackers were shot down and unloading went on in the later afternoon.

The morning had brought news of the approach of a Japanese naval force which Turner assessed as 2 battleships, 2 to 4 heavy cruisers and 10 to 12 destroyers. These were obviously intent on the destruction of ships, or the bombardment of the airfield, or both. Turner, naturally anxious not to be caught by these purposeful craft, cut short his unloading at the end of the day (although it was still unfinished) and sent his soft-skinned vessels out of the danger area under a close escort. But, though the ships might elude the hunters, the shore defences could not. Callaghan therefore turned to protect the island, taking Scott with the latter’s flagship Atlanta and two of his destroyers under his command. His whole force then consisted of 2 heavy and 3 light cruisers and 8 destroyers.

Headed towards Savo, Callaghan located the Japanese ships at 1.24 a.m. between Savo and Cape Esperance, but his radar was not strong enough definitely to find the position either of his own scattered forces

or those of his enemies. The battle quickly became a melée, a naval free for all, with friend often not knowing foe across the dark waters. Both Callaghan and Scott were killed. But though the Americans were harshly handled the Japanese gave up their attempt to break through and withdrew. The new day, however, exposed crippled and rescue ships of both sides on the glittering sea between Savo and Guadalcanal. These still struck dying blows at one another. Among them was a stricken Japanese battleship. American airmen kept at her during the day and, when night came, her crew scuttled her. But not only the Americans had a sting left for, about 11 a.m., limping away from the battle scene where she had been almost sundered by a torpedo, the cruiser Juneau was torpedoed again—by a lurking submarine—and sank at the base of a great pillar of smoke with all but ten of her crew.

Twelve of the thirteen American ships which had been engaged were sunk or damaged. The cruisers Atlanta and Juneau had gone and four destroyers with them. The heavy cruisers San Francisco and Portland, with three destroyers, were seriously damaged. With the two remaining ships they made for Espiritu Santo after the battle. The Japanese lost the battleship Hiyei and two destroyers and had four destroyers damaged. But though numerically they fared the better, and lost far fewer men than the Americans, they failed in their object. This (it was learnt later) was to put Henderson Field completely out of action to give a run, clear of air interference, for an invasion fleet which was behind them.

To deliver this first blow Admiral Kondo, in command of the naval side of the new invasion, had sent Vice-Admiral Hiroaki Abe out from Truk on the 9th with the battleships Hiyei and Kirishima screened by light forces. Abe subsequently rendezvoused with more destroyers which put out from the Shortlands on the 11th. His group then consisted of the two battleships, the light cruiser Nagara and 14 destroyers, and this was the force which Callaghan met. (After the battle Admiral Abe was removed from his command, sent to a shore posting, and retired at an early age after a short “face-saving” period ashore.)

Before Callaghan and Abe clashed, Admiral Kinkaid, who had been racing time at Noumea where his carrier Enterprise was being repaired after the Santa Cruz battle, was boiling towards Guadalcanal although repair gangs were still hard at work on the ship. On the morning of the 13th, still between 300 and 400 miles from Guadalcanal, he flew off some aircraft to base them temporarily on Henderson Field since his carrier was still not able to operate with complete efficiency. The first target these sighted was the crippled Hiyei and they joyfully bore down on her. Meanwhile Admiral Halsey had ordered Kinkaid to cover, by remaining well to the south of Guadalcanal, the withdrawal of ships damaged the previous night. Later he told Kinkaid to have his heavy-gun vessels ready for a quick dash to Guadalcanal on orders from him—so Rear-Admiral Willis A. Lee waited at the alert with two battleships, Washington and South Dakota, and four destroyers. When, however, Halsey, having learned that a new bombardment force was on its way to pound Henderson Field

on the night 13th–14th, sent orders for Lee to close on it, Kinkaid’s group was still too far away to permit of this being done. Although Lee raced off he knew he could not reach Guadalcanal before about 8 a.m. next day.

Vice-Admiral Mikawa profited (although unknowingly) by this error. He had put out from the Shortlands about 6.30 a.m. with 4 heavy cruisers (Chokai, Kinugasa, Suzuya and Maya), 2 light cruisers (Isuzu and Tenryu) and 6 destroyers, as Kondo had planned to follow up Abe’s initial attack on Henderson Field with lighter blows from Mikawa the following night. He saw no reason to change his orders to Mikawa simply because Abe had failed, and so, with Callaghan and Scott dead and their force broken, with Kinkaid and Lee far to the south, and with night keeping the airmen earthbound, there was little to hinder Mikawa when he arrived off Savo soon after midnight on the 13th. Peeling a patrol group off to westward under his own command he sent Rear-Admiral Shoji Nishimura to drench Henderson Field with high explosive. This the latter did, for thirty-seven minutes, with only two motor torpedo boats to worry him.

Back in Washington it was still the morning of Friday the Thirteenth. Everyone hoped that Callaghan’s sacrifice had stopped the enemy; it was a shock to hear that heavy surface forces had broken through and were shelling Henderson Field. And when, a few hours later, word came that Japanese transports were heading down the Slot unopposed by surface forces, even President Roosevelt began to think that Guadalcanal might have to be evacuated. “The tension that I felt at that time,” recalled Secretary Forrestal, “was matched only by the tension that pervaded Washington the night before the landing in Normandy.”3

Early on the 14th aircraft reported more fighting ships and some transports headed for Guadalcanal, and Mikawa’s retiring Support Group some 140 miles Northwest. Other aircraft then attacked Mikawa. They left Kinugasa burning and Isuzu smoking heavily. Shortly before 10 o’clock aircraft launched from Enterprise pressed the attacks home and saw Kinugasa sink. Before Mikawa got clear, he also suffered damage to Chokai, Maya, and a destroyer.

Unwittingly Mikawa had served as a decoy to draw attention from Rear-Admiral Raizo Tanaka’s Reinforcement Group-11 merchantmen escorted by 11 destroyers. Tanaka, obedient to Kondo’s orders for the third phase of his plan, was bringing these down to Guadalcanal laden with reinforcements. He had led them out from the Shortlands on the 12th. Sensibly he had sheltered on the 13th—in preparation for a dash on the 14th to enable him to discharge his troops under cover of darkness that night. But the gods were against him. Henderson Field, despite all Kondo’s planning, was still very much alive; Kinkaid’s carrier-borne aircraft fanned in high and fast from the south, and heavy aircraft from Espiritu Santo joined in. By the end of the day seven of the eleven transports had been sunk.

But still bigger events were pending. It will be recalled that Admiral Lee had left Kinkaid’s main force early in the night of the 13th in a northward

dash—though he was too far south to permit him to arrive off Guadalcanal in the darkness which had sheltered Mikawa’s attack on the island. To avoid detection he had stood about 100 miles off shore during daylight on the 14th. He had listened with interest to the news of the fight with Mikawa and Tanaka but what really touched him closely was a report, about 4 p.m., that a large battle force was southbound from an area about 150 miles north of Guadalcanal.

Lee had very little detailed information of the composition of this force when he manoeuvred to intercept it. He was to learn later that it was Admiral Kondo’s main force—the battleship Kirishima, 2 heavy cruisers (Atago and Takao), 2 light cruisers (Nagara and Sendai), and 11 destroyers. Prowling through the darkness round Savo, Lee made his first radar contact with these at 11 p.m. Seventeen minutes later he fired his opening rounds. Five minutes later the main battle was joined. But Kondo, cunningly deployed, soon had the Americans confused as to the relative positions of their own and the ships they were fighting. At 11.35 p.m. the opening phase of the battle ended with four American destroyers out of action without having launched a single torpedo, the battleship South Dakota blind through failure of power supply, the second battleship in confusion as it manoeuvred to avoid burning destroyers and found its radar echoes bouncing back off Savo. Only one Japanese ship—a destroyer—had been hit.

Soon afterwards Lee ordered his destroyers out of the engagement. Seven minutes later South Dakota was the centre of a concentrated torpedo attack. And then shells began crashing into her. But quickly Washington took up her cause. She engaged Kirishima as her primary target, and within seven minutes Kirishima was aflame and her steering gear was shot away. But South Dakota, badly battered, was also out of the fight. The outcome was still uncertain as the main battle flickered out. It was twenty-five minutes after midnight when Kondo ordered all ships not actively engaged to withdraw, eight minutes later when Lee, having observed the beginning of this retirement, ordered the withdrawal of his own forces.

In the small hours the Japanese, with vivid recollections of the ordeal the wounded Hiyei had suffered, scuttled their battleship Kirishima and the destroyer Ayanami. Three of Lee’s destroyers went down, the fourth limped painfully to safety, the big South Dakota had been heavily hit 42 times, had lost 91 men killed or wounded.

Admiral Tanaka was still struggling on with his 11 destroyers sticking close to his four remaining merchantmen. When daylight came on the morning of the 15th it showed three of these four vulnerable ships unloading at Tassafaronga Point to the west of Kokumbona, with the fourth moving slowly offshore. The marines’ artillery, the destroyer Meade from Tulagi, and swarming aircraft, destroyed all four while hundreds of sailors, shipwrecked in the battle of the previous night watched from the wreckages and rafts to which they clung. Then the aircraft began systematically to fire the beach stores until the shore seemed almost one long blaze.

This destruction marked the final failure of the Japanese attempts in November to put the issue at Guadalcanal beyond doubt. The whole failure cost the invaders two battleships, one heavy cruiser, three destroyers and 11 merchantmen sunk, and two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser and six destroyers damaged. Against that loss stood the sinking of ten American ships (one light cruiser, two light anti-aircraft cruisers, seven destroyers) and the damaging of one battleship, two heavy cruisers and four destroyers.

The Japanese plan for these two November weeks became known later. It will be recalled that, after the failure of the Ichiki and Kawaguchi formations, General Hyakutake had landed by mid-October the 2nd Division and two battalions of the 38th Division; that, in the ill-fated October ventures, General Maruyama had attacked the Lunga defences from the south in association with attacks from the Matanikau.

Subsequent to his failure Hyakutake decided to bring in more of his XVII Army; to convoy the balance (the major part) of the 38th Division down from Rabaul in a single group of transports—although certain elements of the 228th Infantry were trickled in to the beaches west of Kokumbona between 28th October and 8th November. His original plan envisaged a major landing at Koli Point and an attack from the Matanikau area. To prepare a clear run for the invaders the navy would bombard Henderson Field as a preliminary to the arrival of the convoy.

Subsidiary to the main plan was the minor operation to land supplies with a few additional troops at Koli Point to assist the survivors of the right wing of the Maruyama assault who had made their way to that point after the October disaster and were to build an airfield on the flat plain south of Koli Point. This landing took place as planned on the night of 2nd–3rd November, but was brought to nothing by the prompt American move westward to meet it under General Rupertus. Hyakutake thereupon abandoned his airfield-construction plans and ordered his men to circle back to Kokumbona by the inland route. Further disaster then attended them, however, for the larger part of the Koli Point force, having escaped the American trap there, were dogged in their retreat by the Raiders who had come in from the east. The Raiders hung like leeches from their flanks and claimed to have killed 400 for the loss of only 17 of their own men before they reported in to the Lunga on 4th December.

Admiral Kondo had planned the two successive blows at Henderson Field which Abe and Mikawa had attempted—the former without success, the latter with some immediate success for which, however, he paid dearly next day. The two later phases of Kondo’s plan were the running in of some 10,000 XVII Army men (with all their heavy equipment) under Admiral Tanaka’s protection, and his own main assault on the island. But Tanaka’s merchantmen were destroyed; probably not more than about 2,000 men got ashore and only a small part of the equipment and stores survived the sinkings and the subsequent air attacks. Tanaka’s decision to continue after the loss of his first seven ships on the 14th was a most courageous one. He could have turned back to his base and landed no

reinforcements at all. But knowingly he traded his remaining ships for the chance of getting sufficient fresh troops ashore to give Hyakutake a chance of ousting the Americans. Kondo’s own last effort, of course, was brought to nothing by Admiral Lee, and the last of Tanaka’s ships were consigned to destruction.

With the naval-air battle of these November days the Guadalcanal campaign mounted its climax, for the success or failure of the fighting ashore at this critical time was almost entirely dependent upon it. The frustration of the Japanese attempts at sea meant that they must now mount another major naval effort before they could hope for the reconquest of the island. Whether they could do that, or whether they would be prepared to accept the risks of attempting it, was still to be seen. And since the hinge on which victory was swinging in the southern Solomons was a naval one, it is fitting that the summing up of this phase should be done by the American naval historian:

Both fleets retired from the field of battle; both countries claimed a tremendous victory. In view of what each was trying to do, and in the light of future events, who really wonBoth objectives were similar: to reinforce one’s own garrison on Guadalcanal but deny it to the enemy by air and sea. With that yardstick the conclusion is unmistakable: Turner got every one of his troops and almost all his materiel ashore, while Tanaka the Tenacious managed to land only about 2,000 shaken survivors, 260 cases of ammunition and 1,500 bags of rice. The Americans dominated the air from start to finish and kept possession of Henderson Field. On the surface, Callaghan chased one force out of Ironbottom Sound, losing his life and several ships in the process, and Lee disposed of Kondo’s second attempt to follow the Mahan doctrine. Air losses were far greater on the Japanese side. Of combat ships the United States Navy sustained the greater loss, but the elimination of two battleships and 11 transports from the Japanese Fleet was far more serious. The enemy could accept a heavy loss of troops because he had plenty of replacements, but he could not replace battleships or transports, and he depended on air and surface fleets to stop any American offensive against Greater East Asia. ... In torpedo tactics and night action, this series of engagements showed that tactically the Japanese were still a couple of semesters ahead of the United States Navy, but their class standing took a decided drop in the subject of war-plan execution. Why was Admiral Mikawa permitted to abandon the area and the transports on the morning of the 14th? Without his muscle-men, the big-bellied transports waddled into a veritable slaughter-house. Again, with Henderson Field still a going concern and an American carrier snorting back and forth southward of Guadalcanal, why did carriers Hiyo and Junyo hang far back to the North-westward, instead of steaming down to square an unfavourable balance of air power? Lastly, why were the transports not recalled to Shortland to reorganise (as at Wake in December 1941) when it became apparent that the operation was not proceeding according to book? ... a captured Japanese document admitted: “It must be said that the success or failure in recapturing Guadalcanal Island, and the vital naval battle related to it, is the fork in the road which leads to victory for them or for us.”4

The same mid-November days which were thus proving critical ones in the Solomons saw a new phase opening in New Guinea. There, it will be remembered, in addition to the Australian forces pushing down to the Buna–Gona coast over the Kokoda Track, two columns (mainly American)

were approaching Buna from the South-east and the south, according to a plan which had developed chiefly from the Australian occupation of Wanigela in early October when the 2/10th Battalion was flown there from Milne Bay.

As a preliminary to this advance a small seaborne expedition was mounted against the Japanese survivors of the Milne Bay invasion force who had been marooned on Goodenough Island late in August. This, in its turn, however, had been preceded by a smaller expedition of a similar kind to Normanby Island.

There, survivors from a Japanese destroyer, which had been sunk by aircraft on 11th September, had been reported. While their presence did not constitute any military problem, Captain Timperly of Angau believed that their continued undisputed existence on the island was lessening Australian prestige among the natives and rendering administration difficult.

On 21st September, in HMAS Stuart, Captain J. E. Brocksopp of the 2/10th Battalion moved with his company, and certain attachments, against this shipwrecked group. He landed at Nadi Nadi at dawn next day. But the country was rough and tangled and Brocksopp was not able to bring the fugitives to battle. The natives were cooperative, and through them Brocksopp was able to take eight prisoners, all except one of whom were wounded. He found much evidence of Japanese occupation and the natives told him of parties living and moving in the area, the largest

probably being about fifty to sixty strong. Two Japanese warships patrolled the coasts and turned searchlights on the shore that night but took no other action. Brocksopp embarked his party again on the Stuart, without incident, on the afternoon of the 23rd. He was convinced that the only way successfully to carry out such operations would be by using small craft in a series of little “aquatic hooks”.

On 19th October Lieut-Colonel Arnold was told to take his 2/12th Battalion and certain attached troops to Goodenough Island; to destroy there approximately 300 Japanese marines whom native reports indicated were concentrated in the Galaiwau Bay–Kilia Mission area in the extreme South-eastern section of the island; to reconnoitre the approaches to the island and suitable sites for airfields and to re-establish coastwatching and air warning stations in the area.

Arnold planned to land his main battalion group (less one company group under Major Gategood) at Mud Bay, on the east coast. He would move slightly south of west to Kilia Mission, some four hours’ march he was told, across the mountains which ran down the centre of the isthmus which formed the southern extremity of the island. Gategood and his men were to land at Taleba Bay, on the west coast of the isthmus immediately opposite Mud Bay and six miles distant as the crow flies. When the main thrust pushed the Japanese from Kilia they would tend to move Northwest round the coast and come against the waiting Gategood some four miles only from the mission. Thus he would destroy them. After close scrutiny from the air of the area of their proposed operations by himself and his company commanders, Arnold embarked his main force in HMAS Arunta and Gategood’s men in HMAS Stuart.

The landing at Mud Bay began soon after dark on 22nd October. Silence was to be one of its features as the soldiers trans-shipped to small vessels and went ashore through a beach-head made by Head-quarters Company. But the rattle of racing chains as the destroyer cast her anchor echoed round the island, two landing craft collided with a crash in the darkness, and at least one other ran on a mud bank so that weapons and equipment clattered as soldiers fell heavily in the boat itself or into the water. There was some confusion on the beach as the companies sorted themselves out. Altogether the landing, planned as a standard amphibious operation on a small scale, did not go smoothly.

With his own headquarters and a lightly-equipped force of three companies Arnold pushed inland towards Kilia Mission at 11 p.m., guided by native policemen. But the Angau men who had described the approach had not taken into account their own practised ease in moving unburdened through the mountains when they had described the march as a four-hour one, a description which might have been applicable to their own movement on a fine day. The soldiers found the going most difficult. It was raining heavily.

This, in conjunction with the steep, slippery track, made the ascent of the intervening hills very difficult (said Arnold later). It was quite a common practice for men to slip back fifteen yards, to laboriously climb again, only to slide back

once more. The men were soaked through and through by rain and perspiration. It was not till 0300 hrs 23rd October that the summit of the range was reached. Thereafterwards the descent became more hazardous than the climb.

Meanwhile Gategood’s party, a little over 100 strong, had landed at Taleba Bay in the darkness of the early morning of the 23rd.

Arnold had timed his attack on Kilia for 6 a.m. but the slow and difficult going threw his plans out. It was not until 8.30 that his tired leading troops, Captain Ivey’s company, met Japanese about half a mile north of the mission. The Australians found that their way lay through a narrow pass opening on to a stream which flowed at right angles to their line of advance. Beyond the stream a high feature, heavily wooded, rose steeply. Fire from positions which they could not locate, and grenades rolled down upon them, prevented Arnold’s men from crossing the water. They were wearied by their march. Arnold decided that they should rest before attacking strongly on the 24th.

During this arduous day, try as he might, Arnold could not reach Gategood by wireless although, in the distance, he could hear firing at intervals. Actually, Gategood had struck determined opposition soon after his landing.

At first light he had moved inland along a native track. At 5.45 a.m. he encountered the Japanese, lightly at first but the resistance quickly grew. His men pushed on through waist-high grass, firing from standing positions as they advanced. They cleared the initial opposition and repulsed a sharp counter-attack about 9, but had difficulty in locating their opponents among the bush and were losing men. Company headquarters came under fire from what seemed to be a heavy mortar.

After the first encounter Gategood had tried unsuccessfully to get into wireless touch with Arnold. In the absence of news of any kind he began to fear that the drive from the other side of the isthmus had been delayed. His own position was worsening, with six of his men killed, and eleven wounded. At 10.45, worried by lack of news of the rest of the battalion, he began to withdraw towards the beach. But the cutter, approaching the shore to pick up the wounded, came under heavy fire and his difficulties were thus increased. Still lacking news of the main operations as the day went on, he feared they had miscarried so, moving to a more sheltered position, he embarked his company and set out for Mud Bay. He reported there next morning, the 24th.

By that time Arnold was just mounting his second attack. It met with no more success than that of the previous day. The Australians were unable to locate the Japanese positions. Arnold said “It was this inability to discover the firers that took the sting out of the attack”. Captain Suthers, leading one of the attacking companies, gave an example of this difficulty:

The country was so close that I got eight feet off a Japanese machine-gun and did not see it. I signalled to a signaller to put the phone on the wire. The moment I pressed the key he [the enemy] fired all he had, hit three of my men. The burnt cordite from the gun was hitting us in the face it was so close.

On the 25th Arnold had prepared an air support program and had two mortars forward. The aircraft did not arrive, however. Nevertheless, when he pushed forward he found that the Japanese had made off. His men moved down to the mission and the beach through an elaborately prepared (but unmanned) defence area. Later he returned part of his force to Mud Bay by sea and part returned over the mountains. The battalion then settled to work to build an airstrip in the Vivigani area, about half-way up the east coast.

In the entire operations the 2/12th lost 13 men killed and one officer and 18 men wounded. They took one prisoner and estimated that they killed 39 Japanese. What had become of the balance of the force they could still only guess.

It was learned later that approximately 350 Japanese of the 5th Sasebo Naval Landing Force had originally been stranded on the island. At first they had been left without rations. They were supplied later, however, by submarines, which also took off about 60 sick and wounded. The Japanese had, in fact, been aware of the Australian landings from the time they began. In the fighting which followed they lost some 20 men killed and 15 wounded. All of the survivors were taken in two barges to Fergusson Island soon after they broke off the engagement. A cruiser picked them up there and took them to Rabaul.

After the Goodenough Island episode, only one battalion of the 18th Brigade was left at Milne Bay; and, after the development of the advanced base at Wanigela, the rest of the brigade had been ready to fly to Wanigela or elsewhere at short notice. This did not mean, however, that the Allied commanders were content progressively to weaken the Milne Bay base or did not fear further attacks there. Indeed, they were well aware of the necessity to secure the area against further Japanese attacks and to build it strongly as their own right-flank bastion. Other seasoned troops were, therefore, brought in to strengthen it. By the middle of October an advanced party of the 17th Brigade, newly returned from Ceylon, arrived at Gili Gili and the battalions followed closely.

The base at Milne Bay, the freedom of the flanking D’Entrecasteaux Islands from Japanese ground forces and airfields, and the development of their own forward airfield at Wanigela, meant that the Americans and the Australians could confidently plan supply by sea as their basic supply line for their coastwise movement. Responsibility for the development of the sea line (and supply generally) fell, early in October, to a Combined Operational Services Command (COSC).

The maintenance of fighting forces in New Guinea (as elsewhere overseas) demanded the development of a base port with its many associated installations and facilities: docks; roads for the distribution of supplies to depots; buildings to protect stores against the weather, for camps and for hospitals; water-supply systems. Initially Milne Bay lacked all of these facilities; Port Moresby itself was only slightly less deficient. Administrative installations at these places had to be developed concurrently with

offensive operations against the Japanese. The problem of supplying and servicing the Australian Army alone was difficult enough. In addition the United States Army and the Allied Air Forces had to be supplied and serviced, each with an administrative organisation and system differing from that of the Australian Army and from that of each other.

To meet the difficult administrative situation, and having conferred closely with General Blamey, on 5th October General MacArthur ordered the immediate establishment at Port Moresby of COSC—to operate under the control of the Commander, New Guinea Force; to include all Australian Lines of Communications units and the United States Service of Supply; to be

charged with the coordination of all construction and sanitation, except that incident to combat operations; and all Line of Communications activities including those listed below:

a. Docking, unloading, and loading of all ships.

b. Receipt, storage, and distribution of supplies and materials.

c. Receipt, staging, and dispatch of personnel.

d. Transportation in Line of Communications areas, or incident to Line of Communications or supply activities.

e. The operation of repair shops, depots, and major utilities.

f. Hospitalisation and evacuation.

g. Such other activities as may be designated by the Commander “New Guinea Force”.5

On 8th October Brigadier-General Dwight F. Johns, of the United States Army, assumed command of COSC with Brigadier Secombe,6 an Australian, as his deputy. The organisation the two were to build up was a radical departure from that which the Australian Army considered normal administrative procedure, but it was adequately to meet the novel demands of a campaign in a country lacking roads and railways, in which all transport had fundamentally to be by sea or air, and in which often the administrative or base areas coincided with the operational areas. Of the COSC operations and organisation Johns was to report later:

From its outset the Combined Operational Service Command was visualised and has been considered largely as a coordinating agency between the American and Australian Forces operating in the New Guinea theatre of operations. ... It was organised on the bases of parallelism, representatives of the Australian and American Services handling the details of the various activities with respect of their particular Services, operating in close cooperation with each other and closely coordinating activities at all times. Following this general principle, for instance, practically all supervisory functions and command activities with respect to Australian units has been exercised by Brigadier Secombe and with respect to American units, by the undersigned. Detailed discussion on all problems arising and the agreement between Brigadier Secombe and myself as to the appropriate solution and action has, at all times, been arrived at as a basis for action and directives. In a similar way coordination between the American and Australian representatives on the Combined Operational Service Command staff having to do with supply, transportation, hospitalisation and evacuation, and construction has been attained. ...

Perhaps the major feature with respect to transportation involved the provision of additional dockage and unloading facilities at Port Moresby and the coordination of unloading activities in order to increase the capacity of this port. This construction and coordination in activities resulted in the increase of the cargo handling record of the port from something under 2,000 tons daily to an average over a considerable period of time of approximately 6,000 tons daily with a peak day of just over 8,500 tons.

Other elements of the transportation responsibility of Combined Operational Service Command involved the coordinated utilisation of ocean shipping consisting of both large ships operated under the Army Transport Service of USASOS, and under Movement Control of the Australian Army, as well as small ships, trawlers, tug and harbour boats, operated under U.S. Advanced Base, the Australian Army Water Transport Group, and Angau. The action of COSC with respect to large ships was concerned with coordination of shipping operations between New Guinea and the mainland of Australia, and of the employment on missions in this theatre of certain of these ships.7

Against the administrative background thus developing, the 126th U.S. Regiment, it will be recalled, had been given the task of crossing from the south coast of Papua overland by way of Jaure, but the difficulties of the track and the development of the airfield at Wanigela had combined to produce a change of plan. Only one battalion crossed the Jaure Track. The rest of the regiment was to be flown to the north coast to begin a landward advance on Buna from the south. Meanwhile, the 128th Regiment had been flown to Wanigela.

Both regiments belonged to Major-General Edwin F. Harding’s 32nd Division, a National Guard (or, in Australian terms, a militia) formation from Michigan and Wisconsin, which had been on full-time duty for two years. Harding had landed his division in Adelaide in May 1942 and it had moved to Brisbane by August as the Allied emphasis began to shift northward. He said later:

From February when I took over, until November when we went into battle, we were always getting ready to move, on the move or getting settled after a move.

This, apparently, was considered the prime reason why an effective standard of training had not been reached by the time Lieut-General Eichelberger arrived in Australia to command the American Corps late in August.8

Not only was the 32nd Division’s training deficient but, after their arrival in New Guinea, the men quickly found that some of their weapons, and much of their clothing and equipment, were unsatisfactory and that they had to modify many details of their organisation. The proportion of sub-machine-guns was increased; two platoons of each of the heavy weapons companies were issued with light machine-guns, the third with either two 81-mm or four 60-mm mortars; each Cannon Company had four 81-mm mortars. The divisional artillery was perforce left behind;

the divisional engineers were too few in numbers for their many tasks and took only hand tools with them into the bush.

The Americans also underestimated the toll that the country would exact from them and the numbers and spirit of the Japanese they would meet. On 14th October General Harding had written to General Sutherland:

My idea is that we should push towards Duna with all speed, while the Japs are heavily occupied with the Guadalcanal business. Also, we have complete supremacy in the air here, and the air people could do a lot to help in the taking of Buna, even should it be fairly strongly defended, which I doubt. I think it quite possible that we might find it easy pickings, with only a shell of sacrifice troops left to defend it and Kokoda. This may be a bum guess, but even if it proves to be incorrect I don’t think it would be too much trouble to take Buna with the forces we can put against it.

He followed this on the 31st with:

All information we have to date indicates that the Japanese forces in the Buna–Popondetta–Gona triangle are relatively light. Unless he gets reinforcements, I believe we will be fighting him on at least a three to one basis. Imbued as I am with considerable confidence in the fighting qualities of the American soldier, I am not at all pessimistic about the outcome of the scrap. ... The health of the troops has been remarkably good. The sick rate is very low. If our luck holds in this respect, we should go into the operation with our effective strength reduced very little by sickness—less than four per cent, I would say.

His men shared their general’s feelings for, when General MacArthur’s order of 3rd November stipulated that ten days’ supplies be built up in rear of each column before any further forward movement took place, an American observer noted:

... Opinions were freely expressed by officers of all ranks that the only reason for the order was a political one. GHQ was afraid to turn the Americans loose and let them capture Buna because it would be a blow to the prestige of the Australians who had fought the long hard battle all through the Owen Stanley Mountains, and who therefore should be the ones to capture Buna. The belief was prevalent that the Japanese had no intention of holding Buna; that he had no troops there; that he was delaying the Australians with a small force so as to evacuate as many as possible; that he no longer wanted the airfield there ... that no Zeros had been seen in that area for a month; and that the Air Corps had prevented any reinforcements from coming in ... and could prevent any future landing.9

By this time the triple overland-air-sea movement of the 126th and 128th Regiments had taken definite shape. After the 128th had been flown in to Wanigela in mid-October, had been prevented by floods from following the 2/6th Independent Company northward across country, and had had two boat-loads of their men attacked in error by an American aircraft as they were moving by sea to Pongani, they had finally slowly completed their seaward movement and were concentrated in the area from Oro Bay northwards to Cape Sudest by mid-November.

Meanwhile ill-fortune and some confusion had also attended the concentration of the 126th Regimental Combat Team. By the time the II Battalion had gathered at Jaure the Australian successes along the main

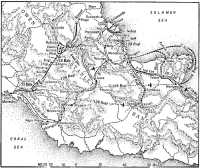

Allied advance across Owen Stanley Range towards Buna, 26th September-15th November

overland track suggested that a move by this battalion directly against Buna might profitably coincide with the Australian advance through Wairopi. The Americans therefore cast off a detachment under Captain Medendorp which left Jaure on 27th October, crossed the divide, and followed the Kumusi River down to Kovio to determine the Japanese dispositions and secure the battalion’s advance against attack from the Wairopi flank. Although one of Medendorp’s patrols had a brush with Japanese at Asisi, some 5 miles south of Wairopi, on 10th November, the latter showed no intention of moving up the trail through that area. Thus the battalion was able to travel eastward without incident, and on 14th November began to arrive at Natunga, about three days’ westward march from Pongani and on the rugged slopes of the Hydrographer’s Range.

Shortly before, however, Colonel Lawrence A. Quinn, commander of the 126th, surveying the difficult air dropping operations at Natunga and Bofu, had been killed when his supply plane, its tail fouled by a parachute, crashed in the mountains. Further setbacks followed within a few days. When the rest of the regiment was being flown across the mountains one transport crashed in the wild interior with the loss of all but six of the men it carried. (These six walked back to Abau and arrived there about

a month later.) To complicate matters further some confusion developed as to whether the air movement should terminate at Pongani, where a landing strip had been completed early in November, or at Abel’s Field in the mountainous country in the vicinity of Sapia, which, it was hoped, could be reached in four days by troops marching down from Abel’s Field. As a result Colonel Edmund J. Carrier, the battalion commander, and most of I Battalion, were landed at Abel’s Field, but regimental headquarters and III Battalion were put down at Pongani.

By mid-November detailed orders had gone out for a coordinated American-Australian advance on Buna. On the 14th General Herring told General Vasey that the Americans were spread along the line Oro Bay–Bofu. Between Bofu and Popondetta the Girua River flowed roughly Northeast to the sea in the Buna–Sanananda area. Generally this river was to form the boundary between the American and the Australian forces. Buna was defined as the American objective, Sanananda and Gona as the Australian. The Americans were ordered to secure a crossing over the Girua near Soputa as soon as possible.

They planned to move northwards in two main columns—the 128th Regiment following the coastal track from the Embogo area to Cape Endaiadere, the 126th an inland axis to Soputa. The confusion whether the air move of the 126th should terminate at Abel’s Field or Pongani twisted the plans for the inland move, however. On the 15th, with the general northward move timed to begin next day, Colonel Carrier’s group were just marching into Pongani from Abel’s Field, the II Battalion was at Bofu, and regimental headquarters and the III Battalion were at Natunga after a forced march from Pongani. It was decided then to ferry the I Battalion to Embogo and have them march thence west-Northwest to Dobodura, where they would rejoin the regiment.

So the forward move began on the 16th; but further troubles came quickly. Ahead of the advanced base which had been established at Porlock Harbour the American supply line was an attenuated one composed of seven luggers, and a captured Japanese barge from Milne Bay. Late on the afternoon of the 16th, this barge, laden with two 25-pounders of Captain Mueller’s10 troop of the 2/5th Field Regiment (the troop had come round from Milne Bay to support the Americans), their crews and ammunition, left Oro Bay for Hariko, just north of Cape Sudest, in company with three of the luggers which carried rations, ammunition and men, each towing a boat or a pontoon. General Harding himself was on board one of the luggers, going forward to the front from the command post he had recently established at Mendaropu (just south of Oro Bay). As the little convoy rounded Cape Sudest fourteen Japanese Zero fighters came with the dusk. Soon all three luggers were blazing fiercely. Then the Australians on the barge watched their turn come.

Three times a Zero made its swooping dives. Tracer bullets, leaving searing ribbons of flame in their paths, ripped into the hull of the barge and into the crouching bodies tightly packed aboard it. There was little that could be done

in defence other than to keep cool and get behind anything offering a scrap of protection. These things the men did. A single light machine-gun had been set up on the stem. As the bright coloured rain of death poured down in graceful curves, Gnr A. G. King11 stood to face the Zero. He fought the plane defiantly with this pitifully inadequate weapon. ... Soon the barge was ablaze. Clouds of dense black smoke billowed upwards. Beneath this canopy the vessel was sinking fast.12

Five of the Australians were killed, sixteen wounded. In all, from the four craft, 24 men were lost, many more wounded. The survivors, including the general, swam ashore. Next morning more strafing Zeros put two more luggers out of action.

These misfortunes, besides resulting immediately in the loss of all the stores, including the two precious artillery pieces, completely disrupted the Americans’ supply plans. Until they could establish an airfield at Dobodura, where one had been planned, they would be almost completely dependent upon supplies dropped from the air. General Harding, therefore, at once ordered General MacNider temporarily to halt the advance of the 128th Regiment until one of the remaining luggers could reach him; and set off on a 30-mile march with full packs the men who were still to be ferried forward from Pongani: Colonel Carrier’s detachment of the I/126th Battalion, a company of the 128th Regiment, an engineer company, and the Australian 2/6th Independent Company.

Despite these checks, however, the combined Australian-American assault on the Japanese defences along the Buna–Gona coast was under way. About the same time as the Americans jumped off on their northward movement on the 16th the Australian veterans of the Kokoda Track crossed the Kumusi River to complete, they hoped, the last phase of their long fight. The 25th Brigade was advancing on Gona, the 16th Brigade on Sanananda. These advances, and the American advance on Buna, were to develop into three virtually separate fronts.