Chapter 14: Gona

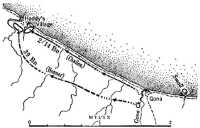

AFTER they crossed the Kumusi River on 15th November the 25th Brigade pushed on for Gona. About 40 miles of tropical lowland lay before them—a track alternately slopping through rank and steaming vegetation and winding through flats of coarse kunai grass on which the heat danced in visible waves.

At first Lieut-Colonel Buttrose led the way with his 2/33rd Battalion; Lieut-Colonel Marson’s 2/25th was hard behind him. They saw signs along the track of hasty Japanese retreat and of developmental work and installations which the invaders had abandoned—permanent huts, large stables, dumps of rice and barley, formed roads, drains and cuttings. But soon they were too occupied with their own troubles to pay more than passing attention to these. The steaming heat, mud, fever and sore feet were quickly finding out the weaker ones.

By the mid-afternoon of 18th November the 2/33rd was at Jumbora where they stopped to prepare a dropping ground in open kunai country. Captain Clowes, with sixty men, pushed on, to occupy Gona if the Japanese had gone, or alternatively to report their strength. Lieut-Colonel Miller was preparing to pick up rations from Buttrose and pass the 2/31st Battalion through to take the lead. Brigadier Eather’s headquarters was back at Amboga Crossing where the 2/25th Battalion had been held.

When Miller overtook him next morning Japanese riflemen were disputing Clowes’ advance through a large kunai patch just south of Gona. Miller pushed Captain Thorn’s company through but Thorn was barely clear of Clowes’ positions when he ran into a regular fusillade. Miller then sent his other companies through or fanned them out on either side of the track. By late afternoon, however, all were held in a semi-circle before Gona: Captain Cameron’s 2/14th Battalion Chaforce company on the right of the track on the outskirts of the village; Captain Beazley’s company astride the track backed up by Captain Upcher’s; Captain L. T. Hurrell’s1 company on the left, with Captain A. L. Hurrell’s company to the left again, stopped on the edge of warding cleared areas; Thorn’s company in reserve in the rear. A tenacious defence commanded the kunai clearings in front of and flanking the mission and took toll of the attackers as they emerged from the scrub and swamps of the main approaches, after tree snipers had already harassed them.

Eather told Miller:

If you think you can clean up enemy use 2/33 Bn patrol also. Adv HQ 25 Bde and 25 Bn four miles in rear of you, and will move up in morning, situation permitting. No ammunition available until dropping commences which should be tomorrow.

But as the night advanced Miller’s position became too difficult. Both food and ammunition were low. Thorn was dead, Cameron and Lieutenant Pearce from the Chaforce company had been wounded, L. T. Hurrell and Upcher were down with raging fever. Miller had thus lost four of his company commanders, thirty-two of his men had been either killed or wounded, and the rest of the battalion was already wasting fast with malaria. Just before midnight Eather ordered him to break contact and fall back behind the 2/25th. This he did in the darkness through a protective position established by Clowes, with fortunate early morning rain pattering heavily on leaves and helping to cover the sounds of his men’s movements. Although towards dawn the Japanese must have become aware of the move, because they then beat the bush with heavy fire, by 8 a.m. the bulk of the 2/31st was back behind the 2/25th. Their enemies had not followed them although Miller reported that, when he left, they were wakeful and active behind their own lines from which had come the sounds of busy trucks, a motor-boat plying to the shore, and men at work handling stores.

That all of their adversaries were not cooped up in front of them, however, was demonstrated to the Australians on this same day when the regimental aid post of the 2/31st reported that of two men who had fallen behind a sick party, one had been found strangled off the track near Awala, his rifle, ammunition and rations gone, and the other was missing. There were very dangerous stragglers in the bush and it behoved any man to walk warily along the silent tracks.

On the 20th Eather waited for supplies. There had been no planes over Jumbora. All of his units were down to their last emergency rations. On the 21st, however, supply aircraft came, dropping food, ammunition, quinine and tobacco. Eather then announced that the whole brigade would go forward on the 22nd except one company of the 2/33rd which was to guard the dropping ground. He proposed to attack Gona Mission with the 2/31st and 2/33rd Battalions, holding the 2/25th in reserve approximately two miles south of the village.

On the 21st Buttrose moved his 2/33rd Battalion to within two miles of Gona and sent patrols to approach from both the east and the west. Soon after 4 p.m. one patrol sighted Japanese as it was about to move off the track a mile ahead of the battalion. At 9.35 p.m. the other reported that it had reached the beach east of Gona with only minor contact.

At 6.30 a.m. on the 22nd Clowes started his company off along the track with the rest of the 2/33rd following half an hour behind him Soon he was fighting about 1,000 yards south of Gona. Captain Power pressed his company forward in support. Clowes was losing men steadily, however, and about 10.50 a.m., this capable and devoted young regular who had taken a leading part in the fighting from the time his brigade first entered action in New Guinea in early September, was himself killed.

Soon Eather had the 2/31st working round the right of the 2/33rd to come against Gona from the east. (He was planning also to complete the movement by sending the 2/25th Battalion against Gona from the

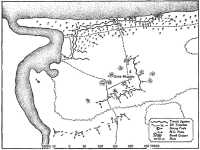

The Japanese defences at Gona

west. From that direction Lieutenant Haddy’s 2/16th Battalion Chaforce company, under command of the 2/31st, was already firing into the defences, having crossed the creek which ran into the sea just west of Gona Mission and became known to the Australians as Gona Creek.) Lieutenant Hayes2 (Thorn’s successor) was leading the 2/31st Battalion’s approach through the timber. Behind him Lieutenant Phelps3 followed with Headquarters Company, and behind Phelps went Captain Beazley’s company. As they approached the beach the timber country yielded to swamp and their detour led them through a kunai patch with the beach on their right and the swamp on their left. By 6 p.m. the whole battalion was in position on the edge of the kunai with Japanese defences fronting them about 300 yards ahead. With one company to guard their left flank as it rested on the swamp, and another to maintain their rear against any threat from the direction of Buna, Beazley, Hayes and Phelps prepared to attack in unison with the 2/14th Battalion’s Chaforce company now led by Captain Thurgood. As Hayes’ and Phelps’ men broke cover for the assault they had to move half right to make room for Beazley’s

and Thurgood’s as the frontage was too narrow to allow all to form up initially in the kunai patch.

Of the attack which followed the 2/31st diarist wrote later:

At zero the men rose and were immediately met by a most intense fire from the front and right flank. They cheered and yelled as they advanced and returned a heavy barrage of automatic fire. They reached the Jap pits but were not strong enough to continue as they were then enfiladed from both sides. Lieutenant Phelps was killed, Captain Beazley missing believed killed and Lieutenant Hayes wounded. The attack died down but the enemy continued a most intense rate of fire.

This unsuccessful action cost the 2/31st 65 casualties.4 The remainder desperately formed a thin perimeter, backed by the swamp, waiting for the counter-attack which did not come, and desperately tried to gather in their dead and wounded under a heavy fire. Company stretcher bearers and aid posts attended the injured and Colonel Marson rushed forward parties to help them back through the swamp and bush. By midnight Miller felt once more that he could hold against any Japanese sallies that might still come, and Eather sent him word that the 2/25th would be forward to help him at first light.

Eather decided that his opponents, in greater strength than he had at first thought, were holding an area some 300 yards square against the sea on the north and Gona Creek on the west. From the creek’s western bank Haddy’s men were still watching and worrying the defenders. Buttrose’s main force was still pressing close from the south. Eather therefore planned a new attack from the east with the 2/25th, and Marson led them to Miller’s northern positions. At 4.30 a.m. on the 23rd he sent them westward along the shore with Miller’s fire helping them. But, though they gained a little ground, generally they fared no better than the other battalion had done. They lost 2 officers and 62 men5 and had to withdraw after dark to hold against the expected enemy counter-moves.

By this time it was clear that the smouldering defence was rapidly burning the Australians out. All three battalions had been badly mauled. From 19th November to 9 a.m. on the 23rd the thin 25th Brigade had lost 17 officers and 187 men in battle6 and many others from malaria—and from sickness induced by the intense heat which shimmered around and above them as they lay in the open kunai. So Brigadier Eather had to plan afresh.

As darkness fell on the 23rd, and before the moon rose, he began to withdraw the 2/31st Battalion; without further loss, Miller brought his men back from within forty yards of the Japanese to the rear of the 2/33rd on the main track. Shortly before this Lieut-Colonel Cameron had led his 3rd Battalion into the area and, although their numbers were now only approximately 180, Eather proposed to use them to give a fresh twist to his tactics—to move them across Gona Creek and try the defences from the west. As an additional new factor he determined

fully to exploit the possibilities of the available air support. His request that the most intense air efforts which could be mustered should be levelled at the Gona area between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m. on the 24th was granted and he was told to withdraw his troops to a safe distance to allow the air attackers full play.

In reviewing the position in conference with his battalion commanders on the morning of the 24th Eather found that his weakened 2/25th, 2/31st and 2/33rd Battalions numbered only 15 officers and 277 men, 6 and 181, 14 and 243, respectively,7 and thus were not strong enough to clear Gona of the Japanese who were well sited and well dug in. He gave orders for vigorous harassing patrols and a program of mortar and Vickers gun shoots and then awaited the results of the air bombardments. These began early in the morning. First, aircraft strafed the defenders and attacked with light bombs until about 11.30 a.m. Then the heavy bombers got to work between 1 p.m. and 2 p.m. with sorties so well directed that comparatively few bombs fell outside the target areas. These left the Japanese with little stomach for ground fighting during the day and gained a substantial rest for the tired Australians.

Late on the 25th Eather tried his new stroke (slightly modified) with the fresh 3rd Battalion. At 4 p.m. they attacked Gona from the South-west supported by machine-gun and mortar fire from the 2/25th and 2/33rd and by artillery fire from the four 25-pounders of the 2/1st Field Regiment sited forward of Soputa. Although they succeeded in penetrating the defences to a depth of some 50 yards at one point, strong positions, well dug and roofed, defied them; at 5.40 p.m. they withdrew, their casualties having been comparatively light.

It was now quite clear that Eather could hope for nothing more than merely to be able to contain his adversaries. And it looked for a short time as though these had no intention of sitting passive in besieged positions. As the evening of the 26th was lengthening, after a quiet day in the forward Australian positions astride the main track south of Gona, the men of the 2/33rd were vigorously assailed with the bayonet by a strong fighting patrol which advanced under cover of heavy machine-gun and mortar fire. Recoiling from an uncompromising reception the Japanese tried to make their way round the 2/33rd’s right flank but were blocked by the 2/25th. As night settled Buttrose and Marson had their men cutting coordinated lines of fire in preparation for further attacks, and from the sea there came the sound of Japanese barges approaching the beach for purposes which the Australians could only guess.

Now, however, a new factor was entering the situation. On this same afternoon of the 26th Brigadier Dougherty had arrived at Brigadier Eather’s headquarters. This quiet and experienced soldier, a simple and uncompromising sense of duty his greatest strength, had flown from Darwin to take over the 21st Brigade from Brigadier Potts when that brigade was reorganising at Port Moresby after its losses on the Kokoda Trail. His

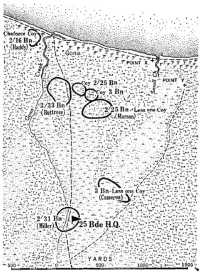

Dispositions 25th Brigade, 27th November

arrival in the Gona area heralded that of his veterans who were anxious to avenge the reverses they had already suffered. At Soputa, the previous day, General Vasey had told him that he was considering two alternative roles for the 21st Brigade: to assist the 16th Brigade in its efforts to capture Sanananda by a wide movement to the sea between Sanananda and Gona, followed by an advance along the coast against the former; or to augment the 25th Brigade whom he described as “depleted and suffering from malaria and fatigue”. As the 21st Brigade had yet to complete its forward move, Vasey continued, Dougherty should go to Gona and discuss the two alternatives with Eather. After that he would receive his orders.

As he trudged from Soputa to Gona Dougherty pondered his problem. He had visited the 16th Brigade in front of Sanananda, knew - that the Americans were struggling vainly to reach a decision at Buna, and had no illusions as to the condition in which he would find the 25th Brigade. Later he wrote of the ideas which came and went in his thoughtful mind:

I set out for Gona, accompanied by Colonel Kingsley Norris (ADMS 7 Aust Div), my Brigade Major (Major Lyon) and two native carriers, walking from Soputa via Jumbora. The track at that stage had not been made jeepable. Coming back along the track through hot and steamy kunai patches, and along that very muddy stretch through jungle, were many sick and wounded men, aided only by means of the universal stick that was carried. The muddy stretch mentioned was about a mile and a half long, and the mud varied in depth from ankle to knee Jeep. After rain it became fluid and it was then easier to walk through than after a few days of dryness when it became like glue. In the jungle alongside this muddy stretch there were many paths which could be used as alternative routes, but they were perhaps equally tiring as the mud. They meant a longer journey—one’s feet were continually slipping at all angles on greasy and twisted roots, and ‘ter a certain amount of use they became soft and gluey. .

I had been giving consideration to the two probable roles which the General had indicated to me. I felt that concentration somewhere was necessary in order to eliminate some of the Japanese. At that stage our forces were split into three pieces

– Gona area, the Sanananda Road, and Buna. At no place did our strength appear to be sufficient to defeat the enemy. If 21 Aust Inf Bde was used to advance on Sanananda via the route suggested there was the possibility that it might meet opposition which it could not overcome—its strength was approximately a thousand only, not much greater than a full battalion. That would result in the allied force being split into four pieces instead of three. ...

I felt that it would be much better to eliminate one lot of enemy opposition before proceeding further, and that the alternative task the General thought of giving us—the destruction of the enemy in the Gona Mission area, in cooperation with 25 Aust Inf Bde—was the desirable one.

I discussed the whole matter with Brigadier Eather. He agreed with my ideas as set out above. 1 became more convinced that those ideas were right when I saw how weary his brigade was.

During the afternoon of 26th November I rang General Vasey and told him of my views and those of Brigadier Eather. He agreed that the best course to take was the capturing of Gona Mission area before proceeding further, and I commenced consideration of plans for the attack.

The 29th was tentatively fixed as the date for the 21st Brigade assault on Gona. Dougherty wished to make it the 30th as the last of his battalions would not arrive until late on the 29th. Vasey agreed but then rang him early on the 28th with the news that General Herring, in view of certain information, insisted on the attack taking place as planned. Dougherty suspected that this information was that the Japanese were trying to land reinforcements.

From 9.30 a.m. to 10.11 a.m. on the 29th aircraft would concentrate upon a small rectangular space which surrounded Gona Mission. First twelve fighters would attack, each dropping a 300-lb bomb. Three Boston bombers would follow with parachute bombs and machine-gun fire. After that six Flying Fortresses would release eight 500-lb bombs and then three more Bostons would follow with bombs and machine-guns. Hard after these attacks the 2/14th Battalion would thrust along the coast from the east, the Blackforce guns, and the 25th Brigade from their positions astride the track south of Gona, supporting them with fire, with the 2/27th Battalion in brigade reserve pending the arrival of the 2/16th in the afternoon.

It was dramatically fitting that the 21st Brigade, rested in its major part and in some measure re-formed, should come to the assistance of the 25th Brigade when the latter formation was withering towards that ultimate exhaustion which it had barely staved off during the past weeks, for thus was the position at Ioribaiwa in early September reversed. And it was also dramatically fitting that the first of the 21st Brigade’s battalions to move into this new action should be the 2/14th. This unit, it will be recalled, had opened the 21st Brigade operations in August when the Japanese were advancing from Kokoda, and had suffered more heavily than any other Australian unit in the entire mountain fighting. Now it was to open the brigade’s operations in the new coastal fighting.

On 25th November Lieut-Colonel Challen, who had returned from Chaforce on the 2nd, had emplaned with the battalion at Port Moresby. (Ten days before it had moved to Ward’s Field to take off but the move

had been postponed at the last moment.) The battalion was not at full strength for 6 officers and 103 men were still detached to Chaforce. The total strength that Challen could muster at Port Moresby was about 19 officers and 450 men and of these some 350 all ranks were flown to the coast. The last of them reached Popondetta late on the 25th when the battalion was organised into three rifle companies, a Defence Platoon and Headquarters Company elements. Next day Challen led them on a tiring march to Soputa where they were told that they would move at 8 o’clock next morning to relieve the 25th Brigade. When they took the track early on the 27th they sank deep in mud which dragged heavily at their plodding feet until the last stages before they bivouacked, just before dark, between one and two miles south of Gona. In the late afternoon Japanese Zero fighters and dive-bombers stormed over them to strafe and bomb Jumbora and Soputa.

About midday on the 28th Challen told his company commanders that the battalion would leave the track just north of the 25th Brigade Headquarters and strike Northeast through a long stretch of kunai running in that direction.8 A few hundred yards south of the beach another spur of kunai, long, narrow and tapering, struck in like a spear from the east, its point almost resting on the original line of advance. This western extremity of the second kunai spur was “Point Y”, the battalion’s “lying up” position. Thence a patrol would push Northwest to “Point X” at the mouth of the little stream which found the sea almost three-quarters of a mile east of Gona. (The Australians called this “Small Creek”.) When the patrol reported “Point X” clear the battalion would assemble there to attack Gona from the east on the 29th, supported by the 2/27th Battalion.

In accordance with these plans the 2/14th halted in the shade of a belt of scrub about 3 p.m. and Lieutenant Dougherty9 took his platoon forward to reconnoitre “Point X”. A little later, when the rest of the battalion was waiting at “Point Y”, news came from the 25th Brigade that “Point X” had been reported clear of the enemy.10 Brigadier Dougherty thereupon ordered Challen not to await Lieutenant Dougherty’s return. The 2/14th therefore moved on towards the beach through 300 yards of bush and then, in single file, through foul swamp, waist deep and fringed with prickly sago palms. Captain McGavin’s company was advance-guard, Captain Butler’s company, battalion headquarters, Lieutenant Rainey’s11 defence platoon and Captain Treacy’s company following in that order.

Just before dark scattered shots and then heavy firing broke out from the head of the column. Confused reports began to come back to Challen

and he dispersed the rest of his battalion into the swamp slime Captain Bisset, the adjutant, hurried ahead with Butler’s rearmost platoon which had been called forward, and found that a difficult situation had developed in McGavin’s company.

About 6.45 p.m. Lieutenant Evans,12 with McGavin’s leading platoon, had broken out on to the beach about 300 yards east of “Point X”. Well-concealed Japanese briskly engaged them from underground, camouflaged, heavily-roofed strongpoints and, among others, killed McGavin himself. Evans took over and, while his own platoon continued to engage the defenders, he asked for Butler to make a flanking approach on his left, and told Lieutenant Clarke,13 with the second platoon of his own company, to await Butler’s attack before moving forward. About 7.20 p.m. he received news from Bisset that Challen had sent Butler to the right and Rainey was moving to the left. Later, through the night darkness hanging over the gloomy swamp, there burst the noise of Butler’s attack. Clarke then tried to get forward but his platoon was cut about and he himself wounded. Butler’s company was likewise held, Butler was badly wounded, Lieutenant Clements killed, Lieutenant McDonald14 missing and almost certainly killed, and some sixteen others killed or wounded.

In the darkness which now hung like a thick curtain over scrub and swamp and sea it was impossible to locate the Japanese positions which had originally been picked up only sketchily in the last of the light. The confusion, arising largely from the fact that so many of the forward officers had been hit, was lessened by the rock-like Bisset. He with the wounded Clarke, who had taken over Butler’s command, organised a holding line. Sergeant Coy15 stood staunchly by until he fell unconscious from wounds. He had been with McGavin when that officer was killed, had shot the sniper responsible, had gone on to grenade two posts into silence, and had then dragged back two wounded comrades before rallying to Bisset. Working calmly among the scattered wounded Corporal Thomas16 was killed and Private Brown17 went on with the work of rescue with a wild storm of fire beating about him. As walking wounded or stretcher parties groped through the darkness Signalman Boys18 met them and guided them to the telephone cable which they could follow through the bog, bush overhanging them and fire whipping in from the beach.

By 2 a.m. on the 29th the battalion had withdrawn to “Point Y” through an intermediate block which Captain Russell had established.

Five officers and 27 men had been lost19 for no gain and primarily through faulty patrol information that “Point X” was clear. Whether the 25th Brigade patrol, and one from the 2/14th itself which had broken out on the beach in the morning about half a mile east of “Point X”, had missed picking up occupied positions in which Japanese were lying doggo by day, or whether the Japanese had been alarmed by the presence of the patrols and reacted by occupying the “Point X” area, is uncertain. The former was probably the case. (Lieutenant Dougherty might have supplied additional information but he and his men had swung much too far to the east and emerged towards Basabua where they surprised and killed approximately twenty Japanese. Runners with this news had missed the battalion and reached brigade headquarters about 7.15 p.m. but the patrol itself did not arrive back until the 30th.)

Brigadier Dougherty reacted to the misadventure by giving Challen new orders for the 29th: to swing east along the kunai spur from “Point Y” and then turn north for the beach, thence to follow it westward from his point of emergence (“Point Z”) and pierce the Japanese left flank. Meanwhile the 2/27th Battalion would pass through Brigadier Father’s positions to debouch slightly to the west of “Point X” and take over the main attack on Gona.

This had been the second of the 21st Brigade units to move forward. Although most of the Owen Stanleys casualties who were to return to the battalion from hospital had done so by the 26th November, the unit was still nearly 300 under strength until 130 reinforcements from Australia joined it that day. About 6 officers and 105 men were still detached to Chaforce. Lieut-Colonel Cooper had begun to emplane on the 25th and on that and succeeding days 21 officers and 353 men had been flown into Popondetta. He left the usual nucleus of old hands behind at Port Moresby and, with them, the reinforcements. These latter were to receive more intensive training before going into action. When he moved his fighting strength from Soputa into brigade reserve at Gona on the 28th he was organised on the basis of a Headquarters, Headquarters Company (Captain Lee20) and three rifle companies (Captains Sims, Cuming21 and Gill). Sims and Gill each had 4 other officers and 77 men with them, Cuming 3 other officers and 77 men.

Early on the morning of the 29th Cooper told his officers that Cuming would head the battalion move to the sea on the west side of Small Creek near “Point X”. They would then move westwards on Gona in the wake of an air strike which was planned for 11 a.m. The artillery would fire concentrations on the Japanese positions just west of the creek until the infantry reached the beach and would then engage opportunity targets. Brigadier Dougherty had planned this merely as an insurance, feeling confident that the battalion would arrive at the beach unmolested.

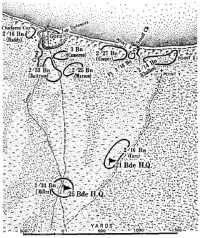

Dispositions, 6 p.m. 29th November

The move began at 10 a.m. But delay followed a guide’s error which caused Major Hanson, the artillery observation officer, to miss his rendezvous with Colonel Cooper. Instead of pushing ahead in spite of this, Cooper delayed, looking for Hanson. Thus the original timings were thrown out and it was not until about midday that the battalion, having made the beach without opposition, swung west against the waiting Japanese who had had time to recover in large measure from the effects of the perfectly executed air strike which had taken place on schedule.

By 12.25 Sims’ company, on the right among the coconut palms, and Cuming’s, on the left in the kunai, had both been driven to ground by heavy fire and were losing men rapidly as they tried to edge forward. After a long three hours Cuming’s company, some 75 yards in advance of Sims’, drove north across the latter’s front at a troublesome post near the water’s edge. In a spirited dash his men burst out of the undergrowth straight into a withering fire which swept the open space over which they tried to advance. Cuming himself, seizing a Bren, plunged ahead of his company into the shadowed space of a Japanese post tunnelled under the spreading roots of a large tree. Firing and shouting, Captain Skipper,22 his second-in-command, followed. (Later both their bodies were found at the foot of the tree ringed by enemy dead.) Though the company reached its objective it was cut about so badly that it had to withdraw to its original position in the secondary growth, temporarily officer-less, as Lieutenants Caddy23 and Bennie24 had been wounded, Bennie mortally.

Cooper’s men had done all they could for the day. In addition to the loss of Cuming and all his officers three of Sims’ officers were casualties –

Lieutenant Flight25 killed, Lieutenants Johns and Sherwin26 wounded. The killed and wounded (7 officers and 48 men) lay under Japanese observation and could be gathered in only under cover of night.27 As this difficult task went on reconnaissance patrols went forward into the darkness.

But the 2/27th had not been the only battalion engaged that day. As the newcomers had pressed the main east-west attack along the shore, the 3rd and 2/33rd Battalions, from positions astride the track, had inched up from the south. On the right, for the loss of one officer and 11 men, the 3rd Battalion had finally dug in on the edge of the timber fronting the southern defences, after one platoon had broken into the village and been forced out again by heavy machine-gun fire. On the left the 2/33rd had been stopped by machine-guns and snipers. Both battalions had lost men from the effects of the heat on weakened bodies.

And to the east of all this flurry, the 2/14th had also been fighting. Colonel Challen had followed his new orders to attempt to clear the area east of Small Creek, in the rear of the 2/27th. At 9 a.m. on the 29th his battalion was on the move again, the courageous Evans once more leading the advance. They struck the beach about 11.30 without opposition. Evans then moved westward with a block established in his rear at “Point Z” to prevent any Japanese foray from the south or east. After advancing some 200 yards he came to a seemingly deserted village. He pushed cautiously onward through a tongue of scrub and then left the first of the houses behind him. Soon his men were vigorously engaged from well-concealed Japanese positions deeper in the village which extended about 400 yards along the seashore. Though Lieutenant Sargent hurried forward to direct mortar fire on to the opposition (almost on to himself, at extreme range), they could not make any substantial gains Challen then ordered Captain Treacy’s company to attack with mortar support through Evans’ positions. Treacy showed the same grim courage that had carried him back across the mountains after he had been cut off at Alola at the end of August. His fine physique made him conspicuous as he coolly directed his attack to within thirty yards of the defending posts which were crossing each other’s fronts with fire. Privates Valli28 and Thompson29 dashed into that fire, flailing the nearest strongpoints with Bren guns from only twenty yards’ range. While the defenders cowered beneath this furious attack the company was able to continue the advance, but it was at the cost of the lives of these two brave soldiers for flanking fire finally caught them. About this time Treacy himself was killed.

In the thick of the fight Private Fyfe30 was cursing the Japanese and

yelling unprintable encouragement to his mates when a bullet struck him mortally. Lance-Corporal Weeks31 tended him where he fell and then carried him carefully through heavy fire to a safer place. Lieutenant Young32 went down wounded, and Rainey’s platoon, skirting to the left, was forced to ground. Then Lieutenant Kolb,33 with about sixteen men, moving further round the left, thrust in with the bayonet. But most of this determined little group were hit, Kolb fatally.

During this afternoon’s fighting Lance-Corporal Davis34 fell. Private Gaskell35 rushed through sweeping bullets to help him, pausing in his dressing to fire again and again. Thus he kept the near-by snipers unsettled until he had bandaged Davis’ wounds. After he had carried him to safety he similarly rescued two other wounded men before he received a death-wound himself.

About 4 p.m. Challen drew his men back a little. An hour later, behind a barrage of mortar bombs, he sent in a new attack under Sergeant Fitzpatrick36 and Warrant-Officer Taafe.37 Though it made some little progress it was then dourly held. After that the battalion withdrew to “Point Z” where they dug in for the night. Three officers and approximately thirty-five men had been lost in this second day’s encounter.

Early in the night General Vasey approved Dougherty’s plans for the 30th. The whole of the 21st Brigade was now in the area for during the day Lieut-Colonel Caro had led in his 2/16th Battalion, 22 officers and 251 men strong, formed into two rifle companies. Caro was given responsibility for the protection of brigade headquarters and also formed a patrol block between the 2/14th on the east and the 2/27th on the west, to stop any movement from the east towards the rear of the 2/27th. Now Dougherty allotted one company of the 2/16th to Cooper as from the early morning of the 30th to act as a reserve for a continuation of the 2/27th attack westward on that day.

Cooper then planned to fall upon the Japanese again at first light on the 30th. Captain Gill’s fresh company would attack through the other two depleted companies which would then follow the new drive. So, at 6.15 a.m. on the 30th, Gill pushed ahead of the positions which Sims and Cuming had reached the previous day. But then heavy machine-gun and rifle fire began to mow his men down and the other two companies, moving to help him, were also checked, still 80 to 100 yards short of the

Japanese. Captain O’Neill’s38 company of the 2/16th, moving up on the extreme left of the attack, suffered a like fate. The day then settled to an exchange of fire. Although Cooper planned a reorganised attack for the late afternoon he decided finally to hold it until next day. He had lost approximately a further 45, including three officers—Captain Best39 (Sims’ second-in-command) killed, Gill and one of his platoon commanders wounded. One officer and ten men of the 2/16th company had been hit.

Farther to the east the 2/14th were still embattled. The dark early hours of the 30th November had been disturbed when one of Challen’s sentries, Corporal Shelden,40 detected a patrol trying to slip past through the water on the seaward side. He killed five and wounded one of them. That ushered in a day of harassing patrols by the 2/14th (with a forward strength now of only 7 and 152) which culminated in a clearing attack westward along the shore by a platoon led by Corporal Truscott,41 who had been prominent in the previous fighting both at Gona and in the mountains—a quiet, very religious man, held in great respect by his battalion. Skilfully and bravely Truscott moved his platoon in at 6 p.m. after Blackforce had given him five minutes of concentrated shell fire. He finally gouged the defenders out of their holes with 2-inch mortar and rifle grenade fire and his men shot them down as they fled along the beach or swam wildly out to sea. Captain Bisset, who had promoted this attack busily, then continued on across the creek at “Point X” and got in touch with the 2/16th and 2/27th Battalions.

The Australians now had a firm grip on a large section of the beach between Sanananda on the right (where the Japanese defences were still firm) and Gona on the left.

That evening Brigadier Dougherty agreed that the 2/27th should continue their westward assault next day. He told Caro of the 2/16th to transfer his second and only remaining rifle company (Major Robinson’s) to Colonel Cooper’s command by 5 a.m. on 1st December. Brigadier Eather agreed that the 3rd Battalion should move to protect the left flank of the 21st Brigade and Dougherty told Cooper to arrange for his companies, attacking westward along the shore, to link with that battalion, which would then move with them, extending their left flank. Cooper had already reported that he was in direct communication with Cameron.

At 5.45 a.m. on the 1st artillery and mortar fire began to crash down in the small area of the Japanese defences. At six, with bayonets fixed, the Australians entered the assault under the cover of mortar smoke. Cooper’s three tattered companies were moving along the shore on the right of the attack, Captain O’Neill’s 2/16th company formed the left flank with orders to link with the 3rd Battalion, Major Robinson’s 2/16th

company was in reserve. But soon the attack seemed to be awry and there was confusion as to the cause. Along the beach the 2/27th men, after subduing the foremost position, were checked and withering, and for some time no one could say what was happening on the left. It transpired, however, that the 3rd Battalion had seen nothing of the left flank of the attack passing in front of them and had made no movement forward. But, soon after that, came the further news that O’Neill had indeed swept the 3rd Battalion front and, with part of Lieutenant Egerton-Warburton’s42 2/27th company (previously Captain Gill’s), was ravaging the central Japanese positions in the village of Gona itself. Lieutenant Mayberry’s43 platoon was the centre of O’Neill’s attack and, by the time they reached the centre of the village, blasting the last of their way there with Brens and sub-machine-guns fired from the hip, had been reduced from eighteen to Mayberry himself and five men. These fought on from shell holes for some time although assailed from both north and south—the area Cameron’s men were to have cleared—and, through some error of the gunners, under fire from the Australian artillery. Then as they tried to withdraw they clashed savagely with a party of Japanese moving back into positions after the bombardment, lost two more very brave men (Privates Sage44 and Morey45), broke westward and crossed Gona Creek to join Lieutenant Haddy’s Chaforce platoon on the far side.

Casualties were mounting fast. Most of the men who had entered the village were now either dead, wounded or missing (a few of the wounded and missing destined to get back when night came). O’Neill himself, badly hit, had been left lying on the eastern bank of the creek. Colonel Cooper was wounded and Major Hearman (second-in-command of the 2/16th) had taken over from him. About the middle of the morning more concentrated fighting boiled up when Major Robinson, with fifteen men from the reserve company, bravely assaulted a strong and troublesome post on the beach. They took the position, but a counter-attack forced them out soon afterwards. Wounded but resolute, Robinson was still fighting when he was again wounded.

For the Australians the rest of the day was one of sweat and hazard as they tried to clear their casualties from the battleground beneath a worrying fire from the main Japanese positions and unnerving shots from concealed snipers. With the night Corporal McMahon46 and Private Yeing47 of Haddy’s platoon swam Gona Creek into Japanese territory and on a punt brought back the dying Captain O’Neill through the darkness

from the position in which he had been lying wounded all day. Through the same darkness came the wavering light of flares from far out to sea, and the distant echoes of heavy bombing, as aircraft attacked Japanese ships which had seemed to be moving in towards the shore but turned out to sea again under cover of smoke.

The day, which cost the 2/16th alone 3 officers and 56 men,48 had once again hinged on a bitter mistake for the Australians—the failure of the 3rd Battalion to move forward and link with the westward attackers. This certainly demanded a nicety of timing and direction in manoeuvre very difficult to ensure in any attack, and certainly most difficult in the Gona country. The actual truth seems to have been, however, that the 3rd was not where Brigadier Eather had thought it to be, or indeed where Colonel Cameron thought it was, but farther south; that, instead of moving forward on its time schedule, it waited for the 21st Brigade’s attack to become manifest, but inevitably saw nothing of it and was not waiting where O’Neill expected to make his junction. Here was a perfect example of the necessity for planning an attack in bush warfare even more carefully than elsewhere, mainly because of limited observation resulting in lack of information and faulty deduction. A major factor was also that the Gona maps were incomplete and inaccurate (despite the fact that air photographs could have been used to provide detailed information which was so urgently needed). But for this mistake the 1st December assault on Gona Mission might not have been another costly failure for the Australians.

Brigadier Dougherty was very worried. Early in the evening Vasey told him that too many casualties were being suffered at Gona; that he was considering leaving a force to contain the place while another force moved eastward in a flanking threat to Sanananda. The upshot was that Dougherty sent Challen along the coastal track to Sanananda next morning with instructions to maintain a firm base and confine his operations to fighting patrols. But scrub and mangrove swamp blocked Challen’s main party beyond Basabua and he was forced to bivouac at Basabua on the night of the 2nd.

At Gona on the same day willing but tired men staged yet another attack as they tried to maintain pressure on their enemies. But its minor nature was indicative of the fact that they had temporarily exhausted their capacity for full-scale assaults. Lieutenant Hicks and twenty men of the 2/16th Battalion (a platoon of the 2/27th standing by to consolidate), supported by fire from the 3rd and 2/33rd Battalions, tried themselves against the most easterly of the Japanese positions which Major Robinson had tested the previous day. They came directly in from the east and pinched off the flanking defences but Hicks himself was mortally wounded and nine more men were shot.

By midday on the 2nd the troubled Vasey was conferring with three brigadiers at the 25th Brigade Headquarters below Gona: Dougherty,

Eather (whose men for the past few days had been able to do little more than merely hold their positions astride the track south of the village), and Porter (whose 30th Brigade was then entering the coastal scene). Vasey had planned to have Porter’s brigade relieve Eather’s but now he said that Eather must continue to contain the Gona garrison. The remnants of the 2/16th and 2/27th, forming a composite battalion under Lieut-Colonel Caro, would join the 25th Brigade. The first of Porter’s battalions, the 39th, which was even then approaching Gona after flying in to Popondetta, would go to Dougherty’s command and follow the 2/14th around the coast to Sanananda. This 39th was the proud militia battalion which had been the first Australian unit to be blooded in the Kokoda fighting. It was still led by the skilful and imperturbable Lieut-Colonel Honner. It was rested and reinforced; its reinforcements included about 100 of the 53rd Battalion who had joined it just before the amalgamation of the 53rd and 55th Battalions to form the 55th/53rd.

The new plan was operating on the 3rd. Wary fire from both besiegers and besieged marked the day in the main area. Eastwards Challen was finding no enemy to contend with but the country was unfriendly enough in itself. The coastal track shown on the map had faded into scrub and swamp and, as they milled about in this inhospitable region, the 2/14th held up Brigadier Dougherty’s own group and portion of the 39th Battalion following behind them. Their difficulties were not lessened when one over-zealous RAAF airman swept low and strafed the whole force in error. It was clear that no line of approach could be established through this country, and Dougherty reported this to Vasey. Vasey then had no choice but to revise his orders. In the early evening he instructed Dougherty to resume command of his own three battalions and to include the 39th with them; to relieve Eather and the entire 25th Brigade (including the 3rd Battalion); and thus become responsible for the whole Gona area. The 49th Battalion, which had already begun to march in to Eather’s command, was to return to Soputa and revert to command of the 30th Brigade which (less the 39th) would then resume action on the main track to Sanananda.

There was more than a hint of bewildered desperation in these rapidly changing plans. The opening notes of this last round, a mere fortnight before, had been confident ones for the Australians. Hot in pursuit the 25th Brigade had passed from elation to a sobered but confident assessment of the unexpected strength of the last-ditch opposition, to exhausted impotence, losing well over 200 officers and men in battle for little visible result just when it seemed that their long and bitter journey from the sea to the sea was at an end. Then the 21st Brigade, anxious to avenge the past, had seen their hopes fading when battle losses alone amounted to 340 out of almost an even 1,000 within five days of their entry into the new action. And still the end was not in sight.

Afterwards some veteran officers were critical of the Australian tactics in this tropical vignette of the trench warfare conditions of the earlier war. Major Sublet, a competent and experienced soldier, thought that

one of the cardinal principles of war—concentration--had been lost sight of. He considered that, though the Japanese had been pounded from the air, with artillery and mortar fire, and flailed with small-arms fire, so that ultimately they scarce dared show themselves above ground, much of the advantage of this had been lost through the shifting emphasis of the Australian attacks. These had taken place on a number of different fronts and, in some cases, sufficiently limited objectives had not been defined. He wrote:

In my opinion we would have gained more by pinching off one enemy strong-point at a time by concentrating manpower with sufficient mortar fire, shell fire and small arms fire against each post in turn. The remainder of our forces could then have been disposed purely to arrest any attempt by the enemy to reinforce or to evacuate Gona.

On 4th December, however, Vasey’s new plans came into operation. By 4.30 p.m. that day the 21st Brigade had completed the relief of the 25th Brigade.49 Dougherty had his headquarters on the track about one mile south of Gona with Captain Thurgood’s and Captain A. J. Lee’s Chaforce companies there as protection. Honner had the companies of the 39th Battalion grouped round the track forward of brigade headquarters and below the Gona southern perimeter. On the seashore the 2/14th Battalion was in a defensive position in their old area just east of Small Creek. Linking with them on the west and reaching towards the eastern extremity of the Gona defences Colonel Caro had his composite battalion spread along the beach.

With the night came determined Australian patrol assaults on the most easterly of the Japanese positions. In this shadowy fighting a number of Japanese were killed and the Australians gained useful information.

Dougherty was content to spend the next day reshuffling his positions slightly as he brought the 2/14th in to change places with Thurgood and

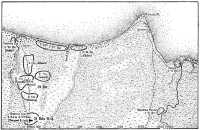

Dispositions, 6 p.m. 4th December

Lee. Worrying news had come to him from General Herring that the Japanese would probably try to land reinforcements from destroyers at the mouth of the Kumusi River. He decided to send both the composite battalion and the 39th to attack again on the 6th, estimating that the total Japanese strength was now about 150. Silent patrols were to move forward

at 5.30 a.m.—Caro’s against the most easterly Japanese strongpoint, Honner’s against the South-west pivot and followed by the main weight of his attack on that axis to secure the fringe of timber, made up of trees four to five feet in diameter, with gnarled roots under and around which the Japanese were dug in. This ran in a line parallel to the beach.

But once again the Australian attack bogged down. Caro’s men gained no real momentum along the beach although the leading platoon, Lieutenant White’s,50 reached within ten yards of their objective (the first post along the beach), where White was killed. In the 39th Battalion’s sector Lieutenant Nelson51 had led his platoon forward on the right of the track in the dark towards the centre of the Japanese southern defences. They were up to their shoulders in the water and slime of a sago swamp when heavy fire was encountered. Nelson was wounded and his men, unable to make the passage of the swamp, withdrew.

Meanwhile Colonel Honner’s main movement, by Captain Bidstrup’s company on the left of the road towards the timber line, was shot to

pieces. The smoke which had been laid to assist Bidstrup’s men, and the half light of the fading night, shrouded their objectives—already well hidden, dug down almost to ground level and roofed—but they themselves loomed large through the murk to their waiting foes. Vicious crossfire from machine-guns struck them after they had gained only about 50 yards. Bidstrup would then have been quite out of touch with his left platoon had not Private Skilbeck52 four times crossed open ground under intense fire to bring back reports to the company headquarters, each time helping wounded men on the way. Once he was asked to lead a reserve section forward and, while waiting for it, went back into Japanese fire to carry in another helpless and wounded man. Sergeant Morrison was another who refused to bend to the circumstances of that day. When his platoon commander was wounded he went forward through intense fire and, even above the din of the fighting, could be heard directing the platoon in its assault. He was wounded—first in the hand and then in the leg—but carried on, shouting orders as he lay on the ground. Fifty-eight of the company had been killed or wounded before the attackers withdrew to cover.

On the right of this main attack, however, some small and fleeting success had developed. The creek had protected Bidstrup’s left. On his right flank Corporal Edgell’s53 section had been ordered to silence any posts in the area through which the attack would pass. Taking advantage of the noise and confusion of Bidstrup’s attack he and his men rocketed to the objective through the gloom and a network of Japanese posts. Finding themselves alone there, however, this small group fought their way back again, Edgell himself (with a sub-machine-gun) and a Bren gunner beside him pouring such a storm of fire into a Japanese post that the two were credited with having killed 10 or 12 of the defenders before they went on their way leaving the final reduction of the post to Lieutenant Tuckey54 and a patrol he had brought out with him

By this time an uneasy situation had developed on the Australian extreme left—west of the main Japanese Gona Mission defences. It will be remembered that the 2/16th Battalion component of Chaforce had been established on the west bank of Gona Creek practically the whole time since 21st November, harassing the Japanese and watching the Australian left flank. Originally six officers and 103 men strong they had dwindled to a strength of 45 all ranks—in actual fact little stronger than a platoon—with Lieutenant Haddy commanding. Like the other Chaforce companies they had had virtually no rest since August when the 21st Brigade had first entered the battle in the mountains. The 45 who remained were gaunt and worn with strain and malaria. In an exposed and isolated flanking position at Gona they had been bombarded by

Australian artillery and strafed by Allied aircraft several times, as they faced the Japanese. Always, his men recorded later, it was Haddy himself who met the varied occasions of their stress with quick presence of mind and unwearied courage, always first to test dangerous situations to protect his men. Several times the little band foiled Japanese attempts to land reinforcements in their vicinity. On such occasions (as in a normal harassing role) Haddy himself usually operated the 2-inch mortar with deadly effect, as implacable in defence as he was dashing in attack.

On the last day of November, with a Chaforce patrol, he relieved Lieutenant Greenwood of the 2/14th Battalion in a small village area, which became known to the Australians as “Haddy’s village”, between one and two miles west of his own Chaforce firm base and not far east of the Amboga River. In that position he beat off a Japanese attempt to seep eastwards towards the centre of operations. In doing so he lost two men killed but wounded a number of the attackers. From reports and observations he concluded that there were between 150 and 200 Japanese just west of the Amboga and native carriers who fell into Australian hands indicated that these were reinforcements for Gona who had been prevented from landing there by Allied air attacks. When, on 4th December, Captain L. T. Hurrell led a strong 2/31st Battalion reconnaissance patrol into this same area, Hurrell and three of his men were killed in a sharp brush with these dangerous elements. Soon, after certain other patrol manoeuvrings, Haddy returned to the village positions on the 5th with 20 volunteers. All were racked with fever and weak.

Just before a rain-driven midnight on the 6th the Japanese closed in. Feeling the aggressive strength opposed to him Haddy sent Private Bloomfield55 back to his own main base for help. Bloomfield, weak with fever, staggered through the darkness with three wounded men, carrying one of them most of the way on his back Finally he delivered his message to Sergeant Jones56 who set out at once with the remainder of the Chaforce men, the whole band numbering fifteen. Soon Jones ran into four questing Japanese whom he shot but, before he was killed, the fourth bayoneted the sergeant. Corporal Murphy57 then took over, encouraging his men and leading them so skilfully that they checked advancing Japanese until help came later on the 7th.

This was in the form of a 2/14th Battalion patrol, fifty strong, under Lieutenant Dougherty, whom Challen had sent on orders from Brigadier Dougherty after news of Haddy’s plight had reached him. Dougherty found the Japanese in strength about half a mile east of Haddy’s village. Always aggressive, he forced a violent clash in which he inflicted comparatively heavy casualties but in which a number of his own men were also lost. As the afternoon advanced he realised that he was being encircled

by much stronger forces so reluctantly pulled back some 500 yards. The brigadier then ordered Colonel Challen to take the rest of his fighting strength (numbering some forty), link with Dougherty, and take charge of operations in that area. Challen achieved this in the early darkness and formed a perimeter for the night about one mile west of Gona Mission.

About 6.30 p.m. two of Haddy’s men from the village reported at brigade headquarters and said that another six of their number were still in the scrub on their way in. (Sergeant Eric Williams,58 leading these men, said the next day that he counted 400 to 500 Japanese moving east.) There was no sign of Haddy himself, however, and it later transpired that he had died as he had lived and fought.

Soon after he had sent Private Bloomfield for help he decided to try to extricate the rest of his men. They combined to write later:

He ordered the withdrawal stating that he would stay to the last. It is mentioned by all his men that Haddy was always placing himself in such positions to enable his men to get out of tight corners irrespective of the risk attached. ... From then until the 2/14th found the bodies of Lieutenant Haddy and Private Stephens59 they were posted as missing. Stephens’ body was in the hut underneath which Haddy had his HQ. At the time the Japs attacked he was on sentry duty and was hit with a grenade. Lieutenant Haddy’s body was found under the hut and from the evidence around the but it proved that Haddy had fought to the last, killing many Japs before they finally got him It was always Haddy who carried out tasks and volunteered for jobs which may have resulted in death for any of his men. On every patrol Haddy was in command of he insisted on being forward scout.60

Meanwhile, back in the main positions, after a night of determined harassing raids by Australian patrols, the 7th had been a comparatively quiet day. Brigadier Dougherty had arranged air attacks as a preliminary to another assault by the 39th. These proved disappointing, however, falling on the Australian rear areas and not near the Japanese. Honner (not prepared to send his men against an unshocked and alerted enemy) at once cancelled the ground program and Dougherty approved his action. That night General Vasey agreed with Dougherty’s plans for the 8th, granted him 250 rounds for artillery support, and agreed to have surrender leaflets dropped on the Gona garrison next morning with the hope of whiteanting their morale before an all-out assault by the brigade.

This was to be Dougherty’s last throw. His fighting strength was down to 37 officers and 755 men (2/14th, 6 and 133; 2/16th, 5 and 99; 2/27th, 4 and 142; 39th, 22 and 381)—less than the full strength of one battalion.61 Colonel Pollard, Vasey’s chief staff officer, called on Dougherty on the morning of the 8th and told him that it might be necessary to withdraw the 39th Battalion and return it to 30th Brigade at Sanananda; that Vasey agreed with Dougherty’s determination to liquidate Gona and, at the same time, investigate the Japanese force apparently based on the Amboga River, but that, if the impending attack were not

successful, further attacks on Gona would be ruled out as being likely to be disproportionately costly; that Gona would then have to be merely contained while as large a force as possible moved to smash the Japanese concentration in the west.

Dougherty’s plan now hinged on the 39th, his strongest battalion. After an artillery preparation it was to operate in three phases: to move north into the timber fringing the southern defences; to attack Northwest into the village; to clear the timber belt on the east side of Gona Creek.

At 11.30 a.m. on 8th December Australian mortars and field guns began ranging. An hour later fifteen minutes of concentrated fire began, the gunners using delayed fuses so that the shells burst about two feet underground, actually boring into the dug-in positions with deadly effect. At 12.45 the 39th Battalion attacked, Captain Gilmore’s62 company on the right of the track, Captain Seward’s63 on the left. Anxious to come to grips Gilmore’s men followed the barrage so closely that they were among the defenders before it had ended and while these were still reeling. On the company’s right Lieutenant Kelly’s64 platoon lost men but smashed into the mission area itself. Undaunted by sweeping fire, Private Wilkinson65 moved into the open, set up his Bren gun on a post about four feet high and, standing in full view of the Japanese, raked them with his fire. On the left of the company Lieutenant Dalby raced his men to the first post and was reported to have struck down the gunner manning a medium machine-gun and seven other defenders. Hard on his heels his men clawed out the remaining defenders of this big post, capturing a medium and three light machine-guns. Then Corporal Ellis66 ranged hotly ahead and his fellows credited him with wiping out the next four posts single-handed.

On the left of the track Seward’s company had been less fortunate. They were badly cut about by fire from the positions Captain Bidstrup’s men had encountered on the 6th. Honner pulled out the survivors and left Lieutenant French’s company to maintain the front there. Sound tactician that he was (and adhering to his own plan which he had made in expectation of success on the right) he then, as the afternoon advanced, sent Bidstrup’s and Seward’s men through the breach that Gilmore’s men had made. They fought on through the afternoon and into the night until half the perimeter defences and the centre of the garrison area were in their hands.

Near the shore Major Sublet, who had taken over command of the composite battalion that morning, was not to be denied a share in this clash. He thrust his 2/27th component along the beach and Captain

Atkinson67 (with the company which Major Robinson had previously commanded) Northwest from his command post. But they did not get far through the storm of machine-gun fire which beset them. Once again Lieutenant Mayberry shone out even in that brave company. With a scratch crew of six men he stormed headlong against a key position. Badly wounded in the head and right arm he still fought on and urged his men forward. His shattered right arm refusing its function, he dragged the pin out of a grenade and essayed a throw with his left hand. But the arm was too weak. He forced the pin back with his teeth and then lay for some hours in his exposed position before he was rescued. The other two platoon commanders also went down, Lieutenant Inkpen68 mortally wounded.

As the day closed Thurgood and Lee of Chaforce covered the composite battalion from the east and Sublet set his men to digging in the small area they had gained.

The surviving Japanese were now pretty well enclosed in a much-diminished area. Between Sublet’s positions on the right and Honner’s on the left there lay a small corridor, possibly some 200 yards in width. Though this ground was swampy it was not sufficiently so to prevent the Japanese from traversing it at night. As darkness covered their desperate plight they tried repeatedly to make their way out through this corridor, or to break through the ring which Sublet and Honner had forged about them. At least 100 were killed in these attempts during the night, some by Honner’s men, most by Sublet’s, some mopped up by the Chaforce men to the east.

An atmosphere that was strangely macabre even for that ghastly place seemed to well out over the battlefield in the darkness that night, stemming from the despairing efforts of the Japanese to escape. A group, trying to steal along the seashore, was mown down by machine-gun fire from men of the 2/27th. Survivors, taking to the water and swimming for the open sea, illuminated themselves in ghostly light as the tropical, phosphorescent water boiled up around them and guided the merciless Australian fire. Into one of the 2/27th’s company headquarters a Japanese officer burst with flailing sword and fell upon an Australian soldier there so that, to other Australians close by, there came the sudden sounds of two men fighting for their lives in the black night, of sword blows, shots, panting breaths and screams.

Early on the 9th, to clean out the remaining pockets of resistance, patrols from both the composite battalion and the 39th moved into the dreadful graveyard which Gona Mission had become for most of the 800-900 men of the improvised Japanese garrison who had been stationed there. In this work Lieutenant Sword, who had fought most bravely and tirelessly since the very beginning of the Japanese invasion, was killed.

The grim search went on until the early afternoon when only isolated individuals, in some reckless last throw desperately starting up from the silence that was settling, remained of the Gona garrison.

The afternoon was spent in burying, salvaging, and cleaning up the area (the 2/16th diarist wrote later). Gona village and beach were in a shambles with dead Japs and Australians everywhere. Apparently the enemy had made no attempt to bury the dead, some of whom had obviously been lying out for days. The stench was terrific. The Japs had put up a very stubborn resistance. They still had plenty of ammunition, medical stores and rice, although a large quantity of rice was green with mould. In one dugout rice had been stacked on enemy dead. More Japs had died lying on the rice and ammunition had been stacked on them again. 638 Japs were buried in the area.

Earlier in the day Honner had rung down the curtain over Gona Mission with a laconic message to Brigadier Dougherty: “Gona’s gone!”

This was, however, in a sense an anti-climax as it meant only a very brief pause in the fighting in the Gona area. The 2/14th Battalion to the west across Gona Creek, had been having a lively time since it had settled into a perimeter about one mile west of the mission. Those three indefatigable young officers, Bisset, Dougherty and Evans, had harried the Japanese on the 8th and the equally indefatigable Truscott (now a sergeant) had led his men in the destruction of yet another post. The following day and night Challen’s men had continued with a series of minor but aggressive passes against an enemy who was obviously in some strength.

It was clear to Brigadier Dougherty that his work was but half done until he had dissolved this very real threat, which the survivors from the mountains and some of the newly-arrived troops were posing. Late on the 9th, therefore, he ordered Honner to move the 39th westward. Honner then came into reserve for a night’s rest preparatory to setting out on his new task on the 10th.

When Dougherty took stock of his strength on the morning of the 10th he found that his three original battalions had lost 34 officers and 375 men in battle and many through sickness. An additional 6 officers and 115 men had been lost in battle by the 39th.69 These bitter losses represented more than 41 per cent of his strength and the engagement was still unfinished. They had been inflicted by an enemy who had seemed already beaten when the last round opened. The Australians had made several serious errors but had fought with dogged bravery, and undoubtedly the Japanese will to fight to the end was the major factor. For example, of the operations by the foremost clearing patrols on the last day at Gona Mission, the 2/16th Battalion diarist has recorded:

Their task was to feel out enemy positions and if fired on go immediately to ground. The patrol following was to come forward and mop up post. At second Jap post along beach twelve lap8 were encountered, at least nine of them were stretcher cases, but all opened fire on party with grenades and rifles. Party retaliated with grenades and killed seven Japs. A message was sent, brought patrol 2/27 Bn up and post was cleaned out.

Quite obviously the Japanese were soldiers to whom, lacking a means of escape, only death could bring an acceptable relief.

Lieutenant Schwind70 and Sergeant Iskov71 of the 2/14th who, in the preceding days, had carried out a long and hazardous patrol in the area of the Amboga River, were guiding the 39th when that battalion moved westward on the 10th, parallel with the coast, and through scrub and swamp. The movement continued next day and, after he had crossed a creek which (it later transpired) flowed into the sea about two miles west of Gona Mission and one mile west of the 2/14th Battalion, Honner turned north towards the sea with Lieutenant French’s company as advance-guard. In the early afternoon the leading scouts and Iskov killed a Japanese Lieut-colonel and two other officers and documents were found on the bodies. Then the Australians, pressing forward into swamp, came hard against the southern defences of Japanese positions located in Haddy’s village on the seashore. Corporal Edgell, the young but proved leader of the forward section, rushed the foremost post, into the muzzle of a machine-gun which wounded him badly in the right arm. Changing his own sub-machine-gun to his left hand he killed the three Japanese manning the gun and then, wounded as he was, assisted two other wounded men back. Lieutenant Plater,72 a spirited young Duntrooner, maintained the impetus of the attack along the track, grenading and machine-gunning, and then personally striking down a number of Japanese officers and men in one foray after another as the day wore on. Just before nightfall one of his section commanders was wounded beside him and, as Plater dressed his wound, he himself was shot through the shoulder blade. But still he staggered at the head of the section to wipe out another obstructing post before he finally allowed himself to be carried from the field.

As Plater’s platoon thus fought on, Lieutenants Mortimore and Gartner73 had swung their platoons to the right and left respectively of the track. Gartner, already marked in the battalion as a skilful tree-sniper, fought hard for four hours until, through the scrub and swamp, he could see the village huts, tantalisingly close, on the seashore. By that time, however, his platoon had been reduced to approximately section strength. Sergeant Meani then led the ten remaining men to watch Mortimore’s right flank while Gartner took over Plater’s leaderless platoon.

Captain Seward tried to work his way wide round the left with his company (now only twenty-five strong), but a storm of fire stopped him The whole battalion then dug in for the night. Rain came with the night, flooding tracks, weapon pits, latrines, so that the Australians were held in swamp and water before opposition sited on higher and drier ground. In the darkness and rain a determined attack overran Seward’s forward

Nightfall, 15th December

platoon from which a handful of wounded survivors straggled in next morning.

During these days, from positions half-way between Gona Mission and Haddy’s village, the 2/14th Battalion had been skirmishing along the coast. On the evening of the 11th Lieutenant Dougherty attempted an attack from the south on the Japanese holding in a cluster of huts just west of the 2/14th positions. But the enemy were not disposed to yield and killed the fearless young Dougherty as he came at them.

By the evening of the 12th Honner had lost 10 killed and 37 wounded in the new operations but had developed a clearer idea of what he was facing. Examination of the Japanese dead and their equipment suggested that his opponents were apparently portion of a freshly-landed force, well fed and well found, approximately equal in numbers, he thought, to his own. More precise information, hastily passed down from higher sources, then revealed that papers taken by Sergeant Iskov from the officers killed on the track on the 11th showed that possibly about 500 men of the III Battalion of the 170 Regiment, had landed between the Kumusi and Amboga at the beginning of December from four destroyers which Allied aircraft had attacked on the night 1st–2nd December. Well-founded estimates suggested that, allowing for casualties which had been inflicted in the fighting up to that time, the newcomers, together with survivors from the mountain fighting who had escaped down the Kumusi and congregated near its mouth, totalled some 600 in the Kumusi–Amboga area on 13th December.

For three days after the 12th Honner was striking for the sea west of Haddy’s village to block off Japanese reinforcements from that direction. These were difficult days of small actions and skirmishes with the 39th edging slowly forward. By nightfall of the 15th, however, the battalion was not only pressing the defenders closely from the south but also closing in from the west where Captain Bidstrup’s company, reinforced by the pioneer platoon, was then overlooking the beach.

During this period the 2/14th men had moved along the shore in the wake of an opposition which had melted grudgingly back into the main defensive area against which the 39th had been spending themselves. (The intrepid Sergeant Truscott was killed in this slow advance.) The Australian trap was slowly closing and, to ensure complete coordination, Dougherty then placed the skeleton 2/14th under Honner’s command.

On the 16th the trap began to spring. On the main track from the south Lieutenant Gartner had given the Japanese no rest since he had

taken over Plater’s platoon five days before. He himself was never still. Among other responsibilities he made the 2-inch mortar his personal concern. Firing this from a shallow position he worried his antagonists constantly. As he worked this deadly little weapon he was the target for everything the Japanese could bring to bear on him until at last they got him about 9 a.m. on the 16th with a burst of machine-gun fire which drove through his hip. During the next six hours, with his platoon, he then fought forward about 40 yards crawling through thick bush. By 3 p.m. he could do no more and was carried from his post. Thirty-five Japanese bodies marked the little space over which his platoon had painfully edged.

On his right, Mortimore’s men had similarly inched forward and, after dark, seized some huts in the South-east corner of the village. The same darkness brought a sally from the west by some thirty Japanese trying to reinforce the village. But they fell a prey to Bidstrup’s waiting men.

The daylight hours had been ones of reconnaissance and scattered small clashes for the men of the 2/14th, sitting right on a little stream which marked the eastern edge of the village and waiting to link with the 39th advance. In the early night they then got Sergeant Shelden and Corporal Russell74 across the stream with small parties, though the move cost Russell his life.

On the 17th the Australians drew their ring closer still. On the extreme left, near the water’s edge, Lieutenant McClean’s platoon of the 39th nipped off another post. Then two more sections of the 2/14th crossed the stream in a brisk little engagement in which Shelden personally knocked out two posts. That afternoon Captain Russell took command of the 2/14th from Challen who had returned with Dougherty to brigade headquarters. Shelden and Private Walters75 did deadly work with rifle grenades, scoring a direct hit on a machine-gun group, destroying at a blow one heavy and two light machine-guns and some twenty-five Japanese.

In the dank darkness, about 2 a.m. on the 18th, Corporal Ellis of Captain Gilmore’s company pressing from the south, wormed his way to within 10 yards of a medium machine-gun position and killed the crew with a shower of grenades. Thus he climaxed three days of lone-wolf activity in which he had searched for that post, crawling out into no-man’s-land in the dark dawn and holing up through the day, showering with grenades what he judged to be the area of the post and sniping at any Japanese who appeared. He was credited with from twelve to twenty kills during those days. After his final exploit he returned to lead his section in the climactic assault.

Gilmore’s and Seward’s companies then inaugurated the last phase of this grim week’s encounter. Soon after the 18th dawned they surged into the village, lashed by heavy fire, Lieutenant Dalby dashing ahead as he had done at Gona Mission and killing the gunner and six other defenders

in a medium machine-gun position. The rest of the force then overran the defences.

They buried 170 Japanese at Haddy’s village. Captured documents revealed that the wounded, and those known to have been killed in the early days of the engagement, outnumbered those finally buried by the Australians. The wounded had been evacuated across the sand bar at the mouth of the creek to the west, or taken off by barges at night.

Thus, for all practical purposes, there dissolved what could have been a major Japanese threat to the Australians, which had been presaged by the arrival at the Kumusi mouth of the III/170th Infantry on 2nd December. But the second failure of the I/170th Battalion to land (little more than a week later) had left Yamagata in a difficult position. He was not then strong enough to fight his way through the Australians who were just beginning to press him hard. He was under frequent air attack. He, therefore, cast aside all thoughts of doing more than maintaining his defence until more troops could reach him. These came soon afterwards. On the 14th the I/170th, it will be remembered, made a successful landfall at the mouth of the Mambare with about 800 men (with them Major-General Oda to take over as General Horii’s successor).

Although the Japanese did not know it their new beach-head was under the eyes of watchers from the Papuan Infantry Battalion and some brave men of a new and special force.

In June 1942 an Allied organisation had been formed to coordinate espionage, sabotage, guerrilla warfare and any other form of activity behind the enemy lines which might seem to offer success. This unit was the Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) and came directly under Major-General Willoughby, General MacArthur’s chief Intelligence Officer, with Colonel Roberts76—an Australian—as commander. The Coastwatchers in the South-West Pacific were incorporated into this force. So it was that, among other AIB men, Lieutenant Noakes77 and Sergeant Carlson,78 his signaller, who had been sent to New Guinea to undertake sabotage tasks for which, in the event, opportunity was not offering, found themselves placed under Commander Feldt as Coastwatchers. Feldt left them at the mouth of the Mambare—and wrote later:

The Mambare debouches into the sea between low, muddy banks along which nipa palms stand crowded knee-deep in the water. Behind the nipa palms, mangroves grow, their foliage a darker green dado above the nipa fronds. Here and there a creek mouth shows, the creek a tunnel in the mangroves with dark tree trunks for sides, supported on a maze of gnarled, twisted, obscene roots standing in the oozy mud. Branches and leaves are overhead, through which the sun never penetrates to the black water, the haunt of coldly evil crocodiles. Beyond the reach of high tide grow sago palms and jungle trees, with bushes and thorny vines filling the spaces between them. ... Slim, boyish and enthusiastic, Noakes was the perfect terrier. Sneaking through the swamp, he arrived at the Jap encampment,

noted their tents and supply dumps and placed them in relation to a sand beach easily seen from the air. Back to camp through the jungle he made his way; then, with Carlson, he hastily coded a signal, which Carlson sent, giving the exact position of everything Japanese.79

Thus Noakes and Carlson brought Allied aircraft swarming about the ears of the Japanese, and continued to do so despite puzzled Japanese efforts at concealment. Partly as a result the Mambare beach-head fell far short of the Japanese expectations; although submarines from Rabaul ran there with supplies which were ferried down the coast on small craft, the volume was comparatively meagre.