Chapter 17: The End of the Road

ABOUT mid-December when the 18th Australian Brigade was taking over from the Americans of Warren Force to sweep the coast as far as Giropa Point; when the Americans of Urbana Force were trying to clear the Triangle preparatory to closing in on the Buna Government Station; and when the Australian 21st Brigade and 39th Battalion, having just taken Gona, were cleaning up towards the mouth of the Amboga River, there began a new phase of the slow struggle among the swamps bordering the Sanananda Track in which first the 16th Australian Brigade, then the 126th American Infantry, and then the Australian 49th and 55/53rd Battalions had drained out their strength. Lieut-General Herring then possessed few infantry units which had not been committed at some stage of the New Guinea fighting. At Port Moresby there were the 2/1st Pioneers, the 36th Battalion and the 2/7th Cavalry Regiment (serving as infantry); at Milne Bay was the 17th Brigade. The pioneers had made a brief foray from Port Moresby along the Kokoda Track, but, for most of their time, had been labouring in the gravel quarry and on the roads at Port Moresby. General Blamey considered it necessary to hold the recently-arrived 17th Brigade at Milne Bay in case the Japanese attacked again. The 36th Battalion and the 2/7th Cavalry were the last Australian infantry to join the coastal forces.

The 36th, a militia unit from New South Wales, had arrived at Port Moresby late in May as part of the 14th Brigade. The 2/7th Cavalry was part of the 7th Division and had been formed in May 1940. Though the regiment had left Australia in that year, battle had so far eluded it. It trained in Palestine and Egypt, went to Cyprus in May 1941 to augment the slender garrison when that island was threatened with airborne invasion, and then rejoined its division in Syria. After their return to Australia with other units of the 6th and 7th Divisions early in 1942 the cavalrymen spent a period in south Queensland training in infantry tactics before they set out for New Guinea in September. Their work and training at Port Moresby continued into December and, when orders to move forward arrived, their spirits rose high. Some 350 of them were flown across the range.

On the 15th December, immediately before the concentration at Soputa of these two fresh units, Brigadier Porter considered the situation existing along the Sanananda Track. Excluding service troops, mortarmen and signallers, he had 22 officers and 505 men in the 49th and 55th/53rd Battalions; 9 officers and 110 men of the 2/3rd Battalion; 22 officers and 523 men of the 126th American Regiment. He noted, however, that the two last-named could be used only in a positional role, the 2/3rd because its men were sick and exhausted, the Americans “for various reasons”

including sickness and fatigue. Of the strength opposed to this force he wrote:

In actual numbers, it is difficult to estimate enemy strength but his state is such that he has undertaken locality defence with every available man and, as such, does not require personnel for the maintenance of a mobile force. All his strength appears to be devoted to occupying fixed positions, in which there are numerous alternative defences, for the purpose of staying indefinitely to impede our advance. His positions are in depth from our present position to a distance of 2,500 yards along the road—this information from our patrols—and probably all the distance to Sanananda. His strength in fighting personnel is probably 1,500 to 2,000 in the forward areas. ... A policy of encirclement will enable us to capture and occupy localities further to the north and even on the road itself, at the expense of strength in hand and protection of our axis and vulnerable L of C installations. I am prepared to seize more ground, as such, but this will not reduce enemy localities other than by a slow policy of stalking and starving him He must be attacked jointly and severally and this requires manpower. ... Since our first assault; we have used a “stalk and consolidate” type of tactics, combined with fire concentrations on enemy positions, as discovered. We have patrolled deeply and over wide areas. Several raids have had the effect of killing some enemy but his well-constructed MG positions defy our fire power and present a barrier of fire through which our troops must pass. We have attempted to seize these in the failing light but they are too numerous to deal with by other than an attack in great strength.

Against this background Major-General Vasey planned an attack for the 19th December by the newly-arrived cavalry and the 30th Brigade, his orders, issued on the 17th, based on this summing-up of the Japanese situation.

Our immediate enemy has been in position without reinforcement of personnel, material and supplies since 21-22 November. During the intervening period the enemy has been continually harassed by air, artillery or mortar bombardments and subject to infantry attacks and offensive patrols. From information obtained from prisoners of war and captured natives it would appear that he is now short of supplies.

The enemy, therefore, should now be considerably weaker although his strength in automatic weapons has NOT been greatly reduced in the areas which he is still holding. However, in spite of great tenacity, past experience has shown he has a breaking point and it i8 felt that this is now close. Adverse local conditions and the ever present possibility of him receiving reinforcements makes it imperative that the complete and utter destruction of the enemy in the Sanananda area should be carried out at the earliest possible moment.

He said that the 2/7th Cavalry, skirting the most forward Japanese positions and starting from Huggins’ road-block, were to push quickly along the track to Sanananda Point and seize the beach area there; while the 30th Brigade, moving initially in the cavalry’s wake and destroying first the forces between themselves and the road-block, were to eliminate all the Japanese then remaining in the area from Giruwa to Garara.

In preparation for the 30th Brigade’s part in this synchronised movement, Porter sent the 36th Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Isaachsen1) to take over on the 18th the positions astride the road which the other two militia battalions had been holding. Lieut-Colonel Kessels then swung the main

part of his 49th Battalion away to the right and Lieut-Colonel Lovell took his 55th/53rd to the left. Porter’s plans for the 19th were that Kessels should clear a way Northwest to the road from the vicinity of the area which Major Hutchison was holding with a handful of weary men of the 2/3rd Battalion and establish himself at a point about 500 yards north of the Cape Killerton track junction; that the 55th/53rd should thrust almost due east from the position Captain Herwig was manning with the remainder of the 2/3rd to clear the major part of the road up to the Killerton Track; the 36th Battalion, in brigade reserve, was to be prepared to exploit the success of either of the other two battalions. Mortars and Major Hanson’s four guns of the 2/1st Field Regiment would support the attack.

The guns opened at 7.22 a.m. on the 19th and the mortars joined in four minutes later. At 7.30 the two battalions began their closing movements towards the track. On the right Captain Noyes, commanding the 49th’s attacking force which consisted of four groups each of approximately platoon strength, made good progress for slight loss by sweeping away two or three machine-gun positions which tried to bar them. Swift to reinforce this success Porter sent Major Douglas’2 company of the 36th to the 49th Battalion’s front. Before midday Douglas relieved Noyes of a troublesome position about 350 yards Northeast of the track junction while Noyes’ men went on through the bush. Late in the day Noyes found that he had skirted the defences which hugged the track and was able to contact Huggins’. After that he followed Porter’s instructions and established a position in the bush a few hundred yards South-east of the roadblock.

On the left of the brigade movement, however, the results of the attack by the 55th/53rd were disappointing. Captain Gilleland’s company on the right flank of that battalion was in trouble early. They came against a strongly-held area from which two machine-guns and stubborn riflemen refused to be dislodged. Although they cleaned out one of the machine-gun positions the other defied them, and the end of the day found them still struggling with it. On their left Captain Coote,3 his company heavily embroiled when it had gone little more than 100 yards, was mortally wounded, his second-in-command was shot nearby, communication with the company was substantially lost, and, though Sergeant Poiner4 stayed with his wounded commander and made brave efforts to maintain control, the company disintegrated into a number of small groups. The loss of two of the platoon commanders and a large proportion of brave NCO’s increased the confusion. As the morning went on Lieut-Colonel Lovell sent in a third company with orders to go through close on Coote’s right. They were slow. In the early afternoon Captain Henderson5 came forward

to hurry them along. But some of the men were reluctant to advance and Porter wrote bitterly later:

Captain Henderson lost his life as he bombed an enemy LMG post. The remainder of his party left him to the task without aiding him.

Finally it became clear that confusion was general and the attack was called off. The battalion assessed its losses at 6 officers and 69 men (including 18 NCO’s) and had achieved little. Porter told Lovell to take over the positions Herwig’s men of the 2/3rd had been wearily but doggedly manning, and one south of Herwig which Lieutenant S. W. Powers’6 company had been manning as the left flank of the 36th. Powers thereupon went to the position occupied by the 49th, broke bush westward to the track on Douglas’ right and began moving south to clear the roadway to the track junction and thence back to the main Australian positions. Night overtook him, however, when he was near the junction and he settled there.

While the small remainder of the 49th relieved the remnant of the 2/3rd, Powers and Douglas (under Kessels’ orders) set about carrying on the fight on the 20th. Powers, however, had barely recommenced his southward movement soon after dawn when Japanese positions astride the track halted him. While he was held there Douglas’ men thrust hard at the positions round which they themselves had been lying, but fared no better than Powers had done. Brigadier Porter, never dilatory, then instructed the Americans to take over from the rest of the 36th and ordered the 36th to attack next day the positions which had stopped Douglas (and of which, obviously, those which had held Powers formed a part). Isaachsen hurried to Kessels’ headquarters in the late afternoon, planned his attack, took Powers’ and Douglas’ companies back into his own command, moved the former back to the vicinity of his own headquarters and made ready to receive the other two companies next morning. When these arrived about 9.40 a.m. on the 21st they were shown the ground, moved out to an assembly area Northwest of the position Hutchison had been holding, and were ordered to fall upon the Japanese from the north. Captain Moyes7 was to take the right, Captain A. M. Powers8 the left; Lieutenant S. W. Powers’ company was to be the reserve. Moyes and A. M. Powers then led off at 3 p.m. behind the artillery and mortar fire. Moyes got forward about 250 yards in the teeth of mounting fire but, for a time, no news came from A. M. Powers. The rattle of heavy machine-gun fire was heard from his flank, however, and soon Isaachsen learnt that one platoon had lost direction and become separated from the company, that the remainder were held under a most resistant fire, and that the company commander himself was missing and was probably dead. Soon the company withdrew; Moyes found it necessary to conform;

and night found the battalion dug in with little to show for the loss of 55 killed, wounded or missing.

By this time Brigadier Porter had become bitterly critical of both the 36th and 55th/53rd Battalions. He said that any success which was theirs was “due to a percentage of personnel who are brave in the extreme”; and “the result of unskilful aggression”. He was caustic in referring to their deficiencies of training and spirit. Nevertheless, it is very doubtful if any Australian units could have suffered the same percentage of losses in their first action and done much better (and the final tally of casualties at Sanananda was to show that the militia losses were almost one-third of the total Australian-American casualties suffered there).

However, rightly or wrongly, Porter lacked confidence in two of his battalions. On 22nd December, the 49th was placed under Brigadier Dougherty (21st Brigade) who, with his brigade headquarters and the 39th Battalion, came over from the Gona area to take command at Huggins’ and forward. The Americans, who made up the rest of Porter’s force, were unlikely to gain ground, although, their force west of the road-block having been relieved by the 39th, they were concentrated once more. They were losing men in action daily trying to do what was expected of them, but were quite spent. Major Boerem was anxious to have them relieved and, on the 27th, he wrote:

This unit arrived on 21st Nov with 56 officers and 1,268 enlisted men. The total strength to date is 20 officers and 460 enlisted men.

Porter could achieve little more than active patrolling during what remained of the year. To add to the Australians’ worries, a very positive Japanese thrust at the four field guns developed. On the night 28th–29th, a raiding party fell upon the gun positions in determined style, exploded a charge in the barrel of one gun and destroyed it. Thenceforward the gunners could never feel safe.

This unsatisfactory state developed behind the 2/7th Cavalry Regiment after it had launched its own movement along the Sanananda Track.

On 16th December Lieut-Colonel Logan,9 with Lieutenant Barlow’s10 troop of Major Strang’s11 “A” Squadron of the 2/7th Cavalry, set out along the pathway which came in from the west to cut the Killerton Track and then passed on to join the Sanananda Track at Huggins’ road-block. This pathway had developed into the supply-line to the road-block and along it Logan now proposed to pass his regiment to avoid the Japanese positions still separating the 30th Brigade from Huggins’. The cavalry would launch their clearing attack towards Sanananda Point from the firm base which Huggins’ represented. Logan returned late the same day leaving Barlow at the road-block to gather information. In the late afternoon of the 17th Strang, with his two other troops, moved along the supply trail

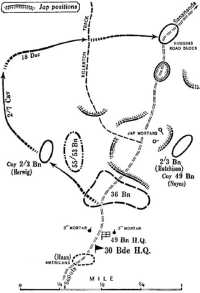

Dispositions prior to attacks of 19th December

to secure a dangerous kunai area in the vicinity of the Killerton Track, and thus enable the main body to carry out unmolested the approach march to the road-block on the 18th. In this, however, he was not successful although he claimed to have killed eight of a Japanese group who refused to be dislodged from a small flanking perimeter commanding the kunai clearing and who, in turn, killed two of his men before the main body of the Australians approached. None the less the latter went through the kunai without loss and the regiment was concentrated at the roadblock when night fell, heartily welcomed by the Americans there. In the miasmic darkness Logan told his men that they would set out the next day at 6 a.m. to push along the track with all possible speed to Sanananda Point; they could expect to be cut off from the main Australian force for some time; Strang’s “A” Squadron would lead, with Logan’s fighting headquarters, Captain James’12 “B” Squadron, Captain Cobb’s13 “D” Squadron, Major Wilson14 (Logan’s second-in-command) with the rear headquarters, and “C” Squadron following—in that order.

It was still dark next morning when the guns from Soputa opened on the Japanese positions forward of Huggins’ and Strang’s men led off close behind the bursting shells. Dazed after the long night and the savage bombardment, the Japanese allowed the squadron to advance for about 450 yards without hindrance. Six of them then started up from the centre of a dump area and two were killed as they fled. Their blood hot, Strang’s men followed with great dash—but ran headlong into the main Japanese positions which were now thoroughly alert. Strang himself was mortally

wounded and all his troop leaders were killed, leaving Sergeant Oxlade15 (bravely assisted by Trooper Hooke16) commanding the most advanced troop, in which four men were killed and the officer and six men wounded; the second troop suffered least (it lost its officer and one other man only); only three men were alive in the third troop. By about 9 a.m. squadron headquarters and the second troop were coming back to the dump area and re-forming there, but Oxlade’s men and the three survivors of the other troop were still forward.

The whirlpool thus suddenly formed across the track washed back against Colonel Logan and Captain James’ men (in Strang’s immediate rear) and the rest of the regiment waiting to go forward from Huggins’. The forward Japanese, who had allowed “A” Squadron through, squeezed in on those who sought to follow. Logan ordered James to make a left flanking sweep with Captain Cobb, who was behind James, moving similarly to the right. The rearmost squadron was to follow Cobb. This whole deployment, however, was necessarily slow if only because, by this time, Logan could reach only Cobb by wireless and had to rely on runners to carry orders to the others.

When James led this outflanking attempt, he found the Japanese vigorously opposed to it. They forced his men back into the narrow confines of the roadway and there pressed them so closely that one Australian, Corporal Sanderson,17 killed three of them in hand-to-hand fighting before he was killed himself. By the early afternoon it was clear to James that he would be doing well merely to maintain his position. He therefore gathered his men into a perimeter defence which the adjutant, Lieutenant Faulks,18 had established on the site of Strang’s first encounter after the loss of his colonel. Logan had been badly hit about 11 a.m. His leg was shattered; he attempted to crawl the 500 yards back to the road-block but died in the bush beside the track.

Night found about 100 men in James’ perimeter some 400 yards forward of Huggins’. Most of James’ squadron were there, with the remnants of Strang’s, the fragmentary headquarters group and a few men from “C” Squadron who had outstripped the rest of their squadron in their efforts to get forward. The main group from “C” Squadron, having failed to make any appreciable progress, fell back on Huggins’. Ahead of them Cobb’s squadron, frustrated in their efforts round the right, had twisted about the track in day-long efforts to advance, losing, among other brave men, Corporal Connell.19 When Connell was shot down he called to his mates to keep clear of him, but they kept on in the hope

of reaching him. So he raised himself from the ground with one last effort to draw the fire which he knew was waiting for them, deliberately threw himself into it and fell dead. Later, approaching darkness finally forced most of the squadron back on Huggins’ but Cobb himself, Captain Haydon20 (his second-in-command) and the rest of the squadron headquarters, and Lieutenant Frank Baker’s21 troop were still somewhere out along the track—probably about 100 yards south of James’.

The main efforts of the cavalry on the 20th were directed towards assessing their position. By wireless James was able to direct artillery and mortar fire on the Japanese ahead of him and give an outline of his circumstances to Major Wilson who, from the rear headquarters still at Huggins’, was temporarily commanding the regiment. About 11 a.m. James was in brief communication with Cobb who, with one of his troops, was still somewhere in the vicinity. Cobb asked for his other two troops to be sent forward from Huggins’ to join him but Wilson replied that heavy machine-guns commanding the road ruled out any immediate hope of this. James then gave Cobb details of his location and Cobb replied that he would try to join the forward garrison, but no further word came from him. Later it was learnt that, in the darkness of the next dawn, he and his men had begun a wary movement towards James along a drain which bordered the road. The Japanese had this covered, however, shot four of the men, split the little group and pinned all motionless under a merciless sun for the rest of the day. When darkness came again Cobb got his wounded back along the drain. He himself remained alone at the most forward point and his companions never again saw him alive.22 Command of the little group then fell to Captain Haydon.

Meanwhile James had been settling his men more firmly within their defence and laying out ground strips to guide the aircraft which he hoped might bring him ammunition, batteries for his wireless, and food (his men had only two days’ rations with them). Wilson got orders through to him about 4 p.m. to try to send back a patrol to Huggins’ with details needed to fill out the scanty picture which the wireless painted. When darkness came James therefore sent off Corporal Morton23 and Troopers Chesworth24 and Hancox25 to swing wide on the western side of the track and then strike eastwards into the road-block. The three men, apprehensive in the midst of the Japanese positions, made slow progress through the dark bush and swamp. By 2 a.m., however, they calculated that they were

then close to Huggins’. They turned due east on the last short lap of their cat-like journey. But luck then failed them and they stumbled over unseen Japanese positions. A grenade exploded at their feet, its burst smothered by the thick mud. Throwing caution to the winds they plunged ahead behind their own fire. Answering fire met them. Chesworth and Hancox went down before it, but Morton, though hard hit, went leaping on like a stag through the enemy ring. Then, behind the burst of one of his own grenades, he was hit again. “Huggins, are you there? Ham Morton here!” he called despairingly. Friendly voices answered him, the fusillade stopped, and hands dragged him within the Huggins’ defences; unknowingly, he had made his last attack on one of the outer American positions and it was American fire which had inflicted his second wound.

The news which Morton brought, and vigorous patrolling from both Huggins’ and James’ on the 21st and 22nd, added much to the Australians’ knowledge of the Japanese dispositions. Nevertheless no junction was made between Huggins’ and James’, and Haydon’s little group remained isolated among the Japanese. James, however, had his men hard at work preparing additional positions to be occupied when the rest of the regiment broke through to him and was most successful in directing artillery and mortar fire on the besieging positions.

At this stage General Vasey brought Brigadier Dougherty of the 21st Brigade across from Gona. In that area, it will be recalled, Dougherty had halted his main operations after the seizure of Haddy’s village on the 19th and had settled down to aggressive patrolling to prevent any further Japanese attempts to move east once more from the mouth of the Kumusi.

On the 21st Vasey told Dougherty to leave Lieut-Colonel Challen in command in the Gona area (the troops there to be known as Goforce) and bring his own headquarters and the 39th Battalion across to the Sanananda Track. Dougherty took over Huggins’ from the Americans next day, and also took into his command the 49th Battalion and the cavalry. The men of the 39th (temporarily commanded now by Major Anderson26 while Lieut-Colonel Honner was ill with malaria) were weary and reduced in numbers and could not be expected to do more than garrison Huggins’; the 49th, reduced to a skeleton, were still in the bush a few hundred yards South-east of the road-block, astride the new supply line; the cavalry, although still fresh and eager, had not been much more than half the strength of a battalion when they first arrived, had taken a hard knock and had yet to be concentrated again. The role given to Dougherty was, therefore, a limited one: to maintain the two road-blocks, build up reserves of ammunition and rations, and patrol aggressively; he was not to attempt any large-scale operations.

After Dougherty’s arrival Lieutenant Hordern27 completed his preparations for a strong sortie to James’ with “C” Squadron and the two troops

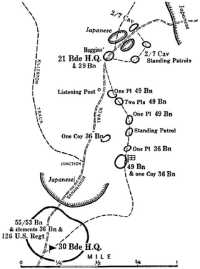

Dispositions, 24th December

which had become separated from Captain Cobb on the 19th. Early on the 23rd these set out to extend the line of approach laid down by the 49th Battalion by swinging wide to the right after they left Huggins’ and later chopping westward across the track into James’. Their movement was slow, small patrols feeling ahead of them like questing antennae to find a way through the maze of Japanese defences. When he was about a third of the way out Hordern cast off a troop under Sergeant Davis28 to form a small perimeter and act as a firm base for patrols to keep sweeping the line which was

being opened. A little farther on he established a second such position under Sergeant Batchelor.29 The main movement then continued, still through a network of abandoned Japanese positions, until finally, with Trooper Pearlman30 (who had done outstanding scouting work during the whole of the day) probing ahead, Hordern crossed the road and entered James’ perimeter—without having lost a man. He found the garrison in excellent heart although they were down to half a tin of emergency rations a day.

On the 24th Hordern returned to Huggins’ and it was then decided that the balance of the regiment should move forward to

James’, leaving at Huggins’ the mortar detachment and the medical post. This they did without incident that afternoon, although the passage of the new route was still a nerve-racking experience.

It seemed an age before we passed Batchelor’s perimeter (wrote Chaplain Hartley31 afterwards). This little citadel of safety seemed very strange, perched on a small piece of higher ground in the midst of dense undergrowth. They reported all clear as we silently passed. The wink of an eye, the raising of a hand was greeting and

encouragement enough for these silent watchers. ... As we neared James’ the track wound in and out Japanese defences that had been abandoned after James’ perimeter had been consolidated. This maze of bunkers and foxholes made us realise how impossible it would have been to supply our perimeter if Nippon had held on to these nests. The strength of these dug-in positions revealed how futile it would have been to try to drive out the enemy without long and sustained attacks. It made us aware too of how precarious was our life line. If the Japs decided to reoccupy their vacated holes the situation would become very critical indeed. The machine-gun nests came right to the road directly opposite the perimeter.

Although the cavalrymen were now concentrated once more, with 19 officers and 205 men at James’, their position was most discouraging. After six days of hard fighting they had advanced only some 400 yards and lost 7 officers and 33 men killed with about as many more wounded. But, pending the development of a new battle pattern, they set about fixing themselves more firmly in their new position, actively reconnoitring, and harassing their enemies. Their first job on Christmas Day, however, was to get out the wounded. There were thirteen of these at James’, eight of them lying cases for whom rough stretchers had to be made on the spot. Chaplain Hartley wrote later:

We were astir early and cooked our breakfast. We got over the problem of smoke from our fires by using cordite from the captured enemy shells. ... It was a slow, tedious and nerve-racking journey. The patients were heavy. Four men were required for each stretcher. These bearers had to carry their arms in their free hands. ... There were times when, to our strained hearing, the noise along the track sounded like a herd of elephants crashing through the undergrowth. ... Whenever there was a stop for rest, armed men would penetrate the jungle off the track and silently watch against a possible ambush. ... As we came nearer to Huggins’ it became easier going. ... We now came into view of the Jap camp that had been shot up on 1st December [30th November]. ... There were mangled and rotting corpses scattered everywhere. Blank-eyed skeletons stared with sightless eyes from beneath broken shelters. Bones of horses with their saddles and harness rotting round them shone white as the morning sun peering through the creepers caught them in her beams. We actually welcomed this gory sight. It was to us a sign post. It meant that Huggins’ was but a hundred yards beyond.32

After this party had delivered their wounded at Huggins’ they returned to the forward perimeter carrying with them Christmas cheer and mail. The small comforts (including sweets for men who were hungry for sugar) gave the soldiers new strength, and letters from home gave them new heart.

One small group, however, still had no share in even this simple Christmas. Haydon’s few men had all this time remained precariously alive in the ditch beside the track forward of Huggins’. The captain, seeing no other way of getting his wounded out of the hornet’s nest in which a number had already been killed, had set his men painfully to work, some days before, at digging a narrow crawl trench back to Huggins’ under the noses of the enemy. With extraordinary patience the soldiers went on with this work, steadily growing weaker from lack of food and their exertions, but they finally got back to Huggins’ on the evening of the 26th after almost eight days of danger and privation.

At first light on the 29th a sortie took place which was to lead to the only event of more than patrol significance between the time James’ perimeter was established and the end of the year. Lieutenant Capp,33 with a reinforced troop, sallied against a Japanese post sited in the deep bush east of the track, roughly midway between Huggins’ and James’, and offering a constant threat to the supply-line. Capp’s men went in with great dash, cleared trip wires, and took the two outer lines of earthworks in the face of well-directed fire. Then, however, the Japanese opposed them so effectively that they had to withdraw—losing 5 killed and 4 wounded.34

When Capp reported that he thought he could have taken the position with more men, Lieut-Colonel C. J. A. Moses, a former officer of the 8th Division who had shared General Gordon Bennett’s escape from Singapore earlier in the year, and had arrived on the 27th to take temporary command of the cavalry regiment, told Hordern to take his squadron against the post. Dougherty arranged artillery and mortar support and the start-time was set for 10 a.m. on the 30th. Although the shells fell as planned, the mortar fire was both late and inaccurate. After a revised mortar program Hordern took his men forward at 11. But, no novices at reading signs, the Japanese were ready. They shot 16 of the attackers, all three troop commanders among them, and Hordern knew it would be folly to press the attack further.

New plans were again being made to end the ghastly nightmare which the Sanananda affair had become. The primeval swamps, the dank and silent bush, the heavy loss of life, the fixity of purpose of the Japanese for most of whom death could be the only ending, all combined to make this struggle so appalling that most of the hardened soldiers who were to emerge from it would remember it unwillingly and as their most exacting experience of the whole war.

After the 19th December had made it clear that the arrival of the two fresh units would still not enable the Australians to sweep a way clear to the sea, Herring visited Vasey on the 20th. The two generals agreed that further major offensive action on this front was not possible with the troops available. Herring said that he would try to bring tanks and fresh infantry into the fight, but that could not happen before the 29th at the earliest. How necessary these were was shown by the figures which Vasey’s headquarters prepared three days later as an approximate summary of the strength on the 7th Division’s front. They showed that the division had received from 25th November to 23rd December 4,273 troops

to replace 5,905 lost to its front from all causes. Thus Vasey’s force was about 1,632 weaker than at the outset.

These figures were particularly disturbing against the background of the entire scene at that time on the Buna–Gona coast. On the right, before Buna itself, the 18th Brigade still had much fighting ahead of them and none could forecast exactly when the situation would be cleared; in the Urbana Force sector the Triangle was still to be reduced and the difficult way through the Government Gardens to the sea lay ahead; Vasey’s figures, and the experiences of the 2/7th Cavalry and the 30th Brigade, told the story of Sanananda; on the left the little Goforce could no longer guarantee its ability to carry out even the limited tasks allotted to it. Vasey considered air action the only real protection for his left flank No further Australian help could come from Port Moresby where no other infantry were left. Possibly the 17th Brigade might come round from Milne Bay but not only would such a move leave a vital point and its adjacent islands and coasts to the protection of one widely-flung brigade, but it would also leave Blamey entirely without means quickly to counter any fresh jab the enemy might make at New Guinea. Could Australia provide more infantry? Of the three AIF infantry divisions the 9th was still in the Middle East; the 7th had been wholly committed in New Guinea and depleted by battle losses and sickness; of the 6th the 16th Brigade had been worn to a shadow in New Guinea, the 17th was at Milne Bay, and the 19th formed the core of the Northern Territory garrison. The militia infantry numbered 18 brigades at this time (two of them of only two battalions). Of these, three brigades had been committed in New Guinea, and three more were destined to arrive there early in 1943; five were in Western Australia, and two in the Northern Territory, forming part of the sparse garrisons of the broad and empty areas from which threats of Japanese landings had not yet lifted. Only five remained to meet military commitments which stretched from the islands north of Cape York (and included the protection of the vital air bases in that northern tip) to Tasmania in the south.

Since, therefore, General Vasey could not finish the fight at Sanananda with what he had, he was compelled to await the end of the Buna fighting so that he might get a transfusion of Australian and American strength from the coastal right flank, or to look for help from American infantry not yet thrown into New Guinea.

At the beginning of the year (as previously mentioned) when the Japanese menace first developed, the first American ground formation sent to Australia had been the 41st Division, and the 32nd Division had followed to compensate for the continued absence from Australia of the 9th Division. The 163rd Infantry—a Montana regiment—of the 41st was on its way to New Guinea in December.35 The Americans rated the regiment

“well-trained, and the men, fresh, ably led [by Colonel Jens A. Doe, ‘noted for his aggressiveness’] and in superb physical condition, were ready for combat”.36 Blamey was directed that the 163rd should go to the Buna front. He promptly told General MacArthur that it was a pity that he had interfered in a matter within Blamey’s sphere; that he did not “for one moment question the right of the Commander-in-Chief to give such orders as he may think fit” but that he believed that nothing could be “more contrary to sound principles of command than that the Commander-in-Chief ... should [personally] take over the direction of a portion of the battle”. The 163rd went to the Sanananda front. Future developments before Sanananda thus depended on the entry into action of these fresh Americans and the successful clearing of the Buna sector. The one might be looked for by the end of the year; the other, it seemed likely, could not take place until early in the New Year and some little time would be required after that for necessary regrouping. Herring wrote an appreciation:

Enemy is reduced in numbers, short of ammunition, food and supplies, whilst our Air Force and PT boats are preventing any large reinforcements or delivery of supplies. He is weak in artillery, has no tanks and has suffered a series of defeats. He has been attacked by our Air Force and artillery and has no adequate countermeasures. He has had over six weeks to develop his defences and along all good approaches we can expect timber pill-boxes in depth which can only be located by actual contact. He is a determined defensive fighter and fights to the death, taking a heavy toll of attacking troops. He has used guns and Molotov cocktails in the jungle effectively against our tanks. ... We have practically unchallenged air superiority, whilst our PT boats are effectively protecting our convoys of small craft to Oro Bay and forward to Hariko. Owing to the jungle it is not possible to derive adequate direct and close air support.

A few days later General Berryman wrote down his thoughts—and concluded: “We have air superiority, and are superior in numbers, guns, mortars and tanks. The problem is to use them to the best effect in the jungle.” He added that Giruwa–Sanananda appeared to be the main Japanese base—with a hospital at Cape Killerton. Against this main area were three major lines of approach: along the sea shore from Tarakenabut this was reputedly a swamp-bound line which, in places, allowed a passage only a few yards wide, with the sea washing one side and mangrove swamps, deep and stagnant, against the other; along the main road to Sanananda—but this was held in depth by obstinate, entrenched and concealed Japanese; along tracks branching westward from the main road towards the coast west of Sanananda—but these were unfamiliar and the country they traversed was known to be largely covered by rotting marshes.

Herring defined his plans on the 29th December. He wrote that it was his intention to resume intensive operations against the Sanananda–Cape Killerton positions as soon as Buna was reduced. Against Sanananda his fighting formations would be the 7th Division and “Buna Force”. To the 7th Division he allotted the 14th, 18th and 30th Brigades and the 163rd Infantry. The three regiments of the 32nd Division would constitute Buna

Force. The task of the 7th Division would be to capture the Sanananda Point–Cape Killerton position and contain the Japanese in the Amboga River–Mambare River area. Buna Force was to defend the Cape Endaiadere–Buna area from seaborne attack and advance up the coast against the Sanananda defences by way of Tarakena. Additional guns were to be moved across to the Sanananda Track from the Buna area and eight more guns of the 2/1st Field Regiment were to come from Port Moresby by sea. Most of the tanks were to join the 7th Division as soon as the Buna operations ended.

On 4th January, having conferred with Generals Eichelberger, Vasey and Berryman, Herring issued his orders. These required Vasey to begin carrying out his role after two battalions of the 163rd had arrived, but obliged the 32nd Division to begin pressing against Tarakena at once with a view to pushing on along the Tarakena–Giruwa axis.

The Japanese, however, were themselves already forcing something of an issue in the Tarakena area. At dusk that day they rose from the swamps and fell upon the most advanced American positions, which Lieutenant Louis A. Chagnon commanded forward of Siwori, and which, only a few hours before, fresh arrivals had brought up to a strength of 73.

The Americans opened fire blindly and in thirty minutes had exhausted their supply of ammunition. They then withdrew in disorder.37

Chagnon’s men, having taken to the sea, counted themselves fortunate that all but four were later able to reassemble at Siwori village.

By this time Eichelberger had made Colonel Grose responsible for the westward push, with the 127th Infantry as his main striking force. Grose at once sent Lieutenants McCampbell and James T. Coker with their companies to make good the Tarakena loss. These, after a difficult crossing, were on the west bank of Siwori Creek by 9 a.m. on the 5th and closed with the Japanese, McCampbell following the water-line, Coker wallowing bravely through the swamp on his left. Despite Japanese delaying tactics, they slowly advanced on that and the following days, Lieutenant Powell A. Fraser’s company having come forward to help them on the 7th. By nightfall on the 8th, after difficult going (particularly along Coker’s axis which still led through clogging swamp) and crisp encounters, the three companies had their enemies at bay at Tarakena. Two fresh companies then came through these tired but satisfied men, and reduced the village before the night was far advanced. Konombi Creek, a tidal stream some 40 feet wide, lay ahead and offered no ready means of crossing. On the 9th Japanese on the far bank successfully disputed the passage and, during the darkness which followed, the swift current frustrated new American attempts. Some brave volunteers then swam the creek in broad daylight and made fast a guy wire on which the two available boats could be warped across. Lieutenant Tally D. Fulmer then led his company over the water, the other company followed, and the bridgehead was

firm by the end of the 10th. But this well-earned success turned a little sour when the 11th revealed what lay ahead—“a section where the mangrove swamp comes down to the sea. At high tide the ocean is right in the swamp. ...”38 Eichelberger thereupon decided to allow Grose to wait until the drive up the Sanananda Track drew aside the curtain which still concealed what Grose might expect farther on.

Meanwhile, within the framework which Herring had formed, Vasey had elaborated his plans. On 31st December these depended mainly on the arrival of the 163rd Infantry, but the 14th Brigade Headquarters was also arriving from Port Moresby. Lieut-Colonel Matthews,39 then commanding the 9th Battalion at Milne Bay, was to become temporary commander of 14th Brigade with only the depleted 36th and 55th/53rd Battalions (which properly belonged there) constituting it, the former already reduced by battle and sickness to some 16 officers and 272 men. Vasey planned that, on the 2nd and 3rd January, the 163rd would relieve the headquarters of the 21st Brigade, the 2/7th Cavalry, 39th and 49th Battalions (in and around the road-blocks). The three last-named would then take over from the 36th and 55th/53rd by 3 p.m. on the 4th and make up the 30th Brigade to which the remnants of 126th Infantry were also allotted. After this relief by 6th January, Matthews would move his two thin battalions west of Gona to relieve what remained of the 21st Brigade. Thus, on the 27th December, after disembarking his I/163rd at Port Moresby, Lieut-Colonel Harold L. Lindstrom flew them across the range. By the time the planned regroupings and reliefs were complete the II/163rd (Major Walter R. Rankin)—whose movement over the mountains had been delayed by bad weather—had also arrived; and the 18th Brigade, their task before Buna completed, had crossed country to the vicinity of Soputa. The 18th Brigade numbers were being quickly made up from about 1,000 fresh troops who were being flown in, and though, after their Buna experiences, the “old hands” were under no illusions as to what lay ahead of them, their spirits were high. By the evening of the 7th three tanks, under Captain May and Lieutenant Heap, had arrived at a bivouac area about three miles south of Soputa (with a fourth soon to arrive from Popondetta). The rest of the tanks were weatherbound at Cape Endaiadere by incessant rains and were to move across to the Sanananda Track as soon as possible. The same rains prevented the artillery moves which had been planned but, mainly to lessen the problem of ammunition supply by getting the weapons as close to the sea as possible, the guns of the 2/5th Regiment and the 4.5’s were concentrated near Giropa Point, and on the 7th, Major Vickery40 landed at Oro Bay eight more guns of the 2/1st, which he later brought into action in the Strip Point–Giropa Point area.

Vasey now planned to have the two newly-arrived American battalions in the road-blocks and astride the Killerton Track (about three-quarters of a mile above its junction with the main track) by nightfall on the 9th, to cut off the most forward Japanese zone (south of Huggins’ and north of the 30th Brigade) and harass the Japanese lines of communication. That done he proposed to destroy all the Japanese thus hemmed in. In order to achieve this the 18th Brigade was to take the 2/7th Cavalry under its command and relieve the rest of the 30th Brigade by the morning of the 10th. Vasey directed also that the remnants of the 126th were to be relieved; this was done by the afternoon of the 9th, battle casualties, sickness and the transfer of regimental headquarters to the Buna front having reduced their original 1,400 to a mere 165.

Before that date, however, eager to come to close grips with the Japanese, Colonel Doe asked to be allowed to try to overcome the main positions between the two road-blocks. Forward at James’ he had one company plus a platoon; the rest of Lindstrom’s battalion was at Huggins’. Now Doe proposed that the company from James’ should fall from the Northeast upon the Japanese left flank and a company from Huggins’ should circle his own left flank and then launch themselves from the west against the Japanese on that side of the road. General Vasey, having dispatched Colonel Pollard to the road-block to ensure that this sally of Doe’s would not commit Rankin’s II/163rd Battalion, or prevent that battalion from carrying out their Killerton Track role on the 12th, assented to Doe’s proposals. When, in the wake of Major Hanson’s artillery fire about midday on the 8th, Lindstrom’s men went into the attack, they had their first taste of the quality of their opponents, who not only refused to budge but flung back the attackers. A little sobered by this efficient hostility Doe then proceeded to follow the main plan. On the morning of the 9th he sent Rankin to strike across country towards the Killerton Track. Rankin was almost at the trail before he met opposition. Some fire from a near-by strongpoint troubled him, but not sufficiently seriously to retard him, and, as the day advanced, he sited his battalion across the track. Next day the regiment’s third battalion marched into the battle area and Doe spread some of the men across the east flank supply-line to Huggins’ and settled the rest in the road-block itself.

The practised Wootten, now busy taking over from the 30th Brigade, had set up his headquarters on the road about three-quarters of a mile below the Cape Killerton track junction. On his right Major Parry-Okeden settled the 2/9th Battalion in the area the 49th had been holding, lying in bush and swamp a quarter to half a mile about east and east-southeast of the junction and roughly parallel with the track. Lieut-Colonel Arnold linked the 2/12th’s right with Parry-Okeden’s left, extended to the track and deployed South-west along it. From Arnold’s rearmost position the cavalry then closed the left flank with a series of positions running almost due north on the west of the road to just short of the Killerton Track, half to three-quarters of a mile above the junction. Lieut-Colonel

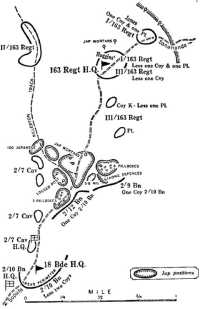

Dispositions, 8 a.m. 12th January

Geard,41 who had taken over from Lieut-Colonel Dobbs when the latter went to hospital after Buna, had the 2/10th in reserve in the brigade headquarters area. Thus the Australians closely cupped the Japanese position astride the main road just south of the track junction, while to the north the Americans blocked both escape routes.

The forward battalions tested the defences on the 10th and 11th when patrols probed for information and the commanders tried to crowd some of their men even closer to the Japanese; but these reacted sharply and flicked the patrols back with minor but stinging losses (9 killed and 19 wounded). Wootten’s immediate plan was to have the 2/9th and 2/12th clear the junction and the road to about a quarter of a mile beyond. Knowing his opponents, however, he entertained few hopes that he might achieve this with one blow and planned, therefore, for separate phases. The first, on the 12th, envisaged a closure towards the junction—a simultaneous attack by the two battalions on opposite sides of the Japanese defences with, on the right, the 2/9th thrusting southwest, and on the left the 2/12th closing on to the road from the east and driving along it at the same time. Three tanks were to help the 2/12th, a company from the 2/10th would strengthen each of the attacking units, while the rest of the battalion, the cavalry, one tank and the mortars of the two battalions would be a reserve.

In the morning mist on the 12th, through the swampy bush, Parry-Okeden sent his two attacking companies of the 2/9th, Lieutenants Jackson’s42 and Lloyd’s,43 to circle his own right flank and get into position

roughly Northeast of the road junction. The other two companies remained generally east and South-east of the junction, their initial task being to support the attack with fire to the west, their later task to close the left flank and harass the Japanese ahead of them. At 8 a.m. Jackson crossed his line, precisely on time, and his men started killing the scattered outer defenders. On his left, however, Lloyd was delayed a little at first and then found his way very difficult in the face of a punishing fire. For a time Jackson held back his advance to allow the other company to keep pace but, despite that, was among the line of trees which constituted his objective by 9.30 a.m. Lloyd then succeeded in getting farther forward and linked with Jackson’s left. The other two companies maintained the battalion front by pressing forward on Lloyd’s left. The men dug in, having substantially achieved their object for the day (although the hard core of the defences was still solid on the track) for a loss of 6 officers, including Jackson and Lloyd who were both killed, and 27 men. They were still linked on the left with the 2/12th.

That battalion’s day, however, had gone wrong from the beginning, when the tanks began to cross the start-line at one minute past eight. The tank crews had been told that there were no anti-tank guns to hinder them and that their task was to knock out the Japanese bunkers, but no one could tell them where those bunkers were. The road ahead was a narrow defile through the swamps, the ground flanking its raised surface so soft that no tank could travel on it, the track itself so narrow that there seemed to be no hope of any tank turning once it had crossed the line. Thus there seemed to be one way only for them—straight on—when Lieutenant Heap led his troop out in line ahead, with Corporal Boughton’s44 tank some 20 yards behind him, and Sergeant MacGregor’s45 following at the same interval. After he had gone about 60 yards Heap stopped, peering left towards a point where he had been told he might find a bunker, his tank’s gun traversing slowly to the left. A shell struck the front of his tank, ricochetted on to the driver’s flap—which it sprung wide—and stunned the driver, whose forehead was pressed against the wall just above the aperture. Heap then saw the gun flash (though he was never able to see the gun itself) from a concealed position about 40 yards to his right front and a second shell struck the track. A third hit followed, springing the hull gunner’s flap and stunning the gunner. By this time Heap had swung his own gun round and was briskly engaging the enemy, though he still had only a general idea of where the other gun might be. A fourth shell then smashed through the vehicle and burst inside it. The only way Heap could now escape was to take the risk of getting off the track. He therefore wirelessed Boughton that he was doing this and plunged into the bush on his left. Boughton’s tank then went ahead but, in its turn, was hammered badly by the enemy gun before it could get

off a shot at its unseen enemy, and Boughton was mortally wounded. It now seemed that, blinded and partly crippled and caught within the narrow confines of the track, the tank was doomed. But the driver, Lance-Corporal Lynn,46 was brave and cool. He peered through a gaping shell hole in the broken vehicle and performed the seemingly-impossible feat of turning about on the roadway, and the tank limped out of the fight. Undaunted, Sergeant MacGregor next closed in. He was not long engaged, however, before flame exploded round his vehicle, probably in part at least from a mine pushed beneath it on the end of a forked stick, and the tank itself was seen to be on fire. It was gutted and the crew perished, but precisely how each died is uncertain still for the fog of battle then closed them round and when the burnt-out tank was examined later no trace of their bodies was found.

These misfortunes stamped out the day’s pattern for Arnold’s infantry. His plan had been that Captain Trinick’s47 and Captain Curtis’ companies should attack up the road with the tanks, with the other two companies moving forward in support from the right of the road. But Trinick himself (who had just “wangled” his way back to the battalion after he had been declared medically unfit for front-line service) was mortally wounded, and his company was unable to advance. On the left, Curtis, whose company’s movement was to be the major one, made three desperate attempts to get ahead, but each time his men were driven back beyond the start-line. The tangled branches of trees which had been torn and twisted by artillery fire proved one of their greatest obstacles; they were caught in these as though in masses of barbed wire. So the 2/12th had scarcely advanced at all by the end of the day, and had lost 4 officers and 95 men. They were so close to the Japanese that carrying parties had great difficulty in getting food to them. When hot food was brought forward much of it had to be thrown into the forward pits from a point near company headquarters.

The Australian commanders were bitterly disappointed at the apparent failure of this day. Vasey wearily took counsel with Wootten at 18th Brigade Headquarters in the evening. As a result he decided to seek the views of General Eichelberger to whom had passed the command of the force in the forward area.48 Next day Eichelberger, Vasey, Berryman (who was acting as Eichelberger’s chief of staff) and Pollard discussed the situation and sharp differences of opinion seem to have developed as various ways out of the impasse were examined. Vasey himself had decided that:

As a result of the attack by 18 Aust Inf Bde on 12 Jan 43, it is now clear that the present position which has been held by the Jap since 20 Nov 42 consists of a series of perimeter localities in which there are numerous pill-boxes of the same type as those found in the Buna area. To attack these with infantry using their

own weapons is repeating the costly mistakes of 1915-17 and, in view of the limited resources which can be, at present, put into the field in this area, such attacks seem unlikely to succeed.

The nature of the ground prevents the use of tanks except along the main Sanananda Track on which the enemy has already shown that he has A-Tk guns capable of knocking out the M3 light tank.

Owing to the denseness of the undergrowth in the area of ops, these pill-boxes are only discovered at very short ranges (in all cases under 100 yards) and it is therefore not possible to subject them to arty bombardment without withdrawing our own troops. Experience has shown that when our troops are withdrawn to permit of such bombardment, the Jap occupies the vacated territory so that the bombardment, apart from doing him little damage, only produces new positions out of which the Jap must be driven.

Vasey considered it best either to advance to Cape Killerton and thence eastwards along the coast by the Killerton Track, provided supplies could be landed by sea, or to land additional troops in some strength from the sea in the Killerton area, although he realised that he lacked the resources to carry out such a plan.

Berryman on the other hand was convinced that a close blockade of the Japanese positions south of the road-blocks was the most practicable solution. Eichelberger, though generally in agreement with this view, approached this proposal rather more cautiously, and Vasey and Pollard shied away from it. Nevertheless, preliminary orders to establish the blockade were issued and, next day, Berryman had prepared detailed orders (which, however, Eichelberger held over pending the receipt of detailed reconnaissance reports from Vasey’s patrols on the 15th). On the 14th Vasey wrote unhappily to Herring:

Doubtless you have heard of the lack of success of the attack of 18 Aust Inf Bde on 12 Jan and also of my interview with Eichelberger and Berryman yesterday.

The position is that George’s [Woollen’s) attack drove in all the outposts in front of the enemy pill-boxes and has disclosed some of them to our sight. 30 Aust Inf Bde, unfortunately, was unable to do this. In view of this situation I feel that it is useless carrying out further attacks supported by tanks (for use of which the country is quite unsuitable, as evidenced by the very early loss of two out of the three employed) and in an area where the distance between our foremost troops and these pill-boxes varies from 20 to 80 yards. It was in view of this that I asked Eichelberger to come and see me yesterday. I attach some notes which I prepared for him. From these you will see that the present intention to encircle closely the Jap opposite 18 Aust Inf Bde is not one of the courses which I thought open to me. While I agree that this course may in time succeed in reducing those immediately in front of us, I feel that it is hardly within the spirit of my instructions which were and, as far as I know, still are to capture Sanananda beach area.

However, the situation was being resolved. A sick and bedraggled prisoner reported on the morning of the 14th that on the night of the 12th–13th (i.e. immediately after the Australian attack) the Japanese defenders of the position south of the road-blocks had been ordered to withdraw all their fit men leaving only the sick and wounded to hold the positions to the last. On the 13th, however, further orders followed: that the positions should be completely abandoned during darkness on the 13th–14th. This information was already being confirmed by the lack of

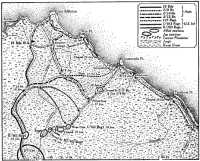

Final operations along Sanananda Track, 15th–22nd January

opposition to Australian patrols; and Wootten’s men were seeping so quickly into the area that, by nightfall of the 14th, the entire road junction area was in their hands. Vasey at once ordered Wootten to pursue his retreating enemies with speed; to push down the Killerton Track to the coast and seize the Cape Killerton area with a view to attacking Sanananda and the track from the west. Doe’s Americans were to destroy the Japanese in their immediate vicinity and then advance directly along the Sanananda Track. Behind these main movements the cavalry were to clean up, and the 30th Brigade was to protect the Soputa–Jumbora dumps. The 14th Brigade was to continue to hold the left flank and cut off any Japanese moving westward.

The 14th Brigade men had had a strange week in the Gona area. They were deployed from Garara on the east of Gona to the mouth of the Amboga River, leaving the 21st Brigade free to move out on the 7th to Popondetta, from which point, and Dobodura, they emplaned for Port Moresby with only 217 left in the whole brigade. When the 36th Battalion took over along the Amboga River they were told that the Japanese had an observation post across the river from Haddy’s village and probably 300 men a little farther back on the western side of the Amboga; the Japanese were passive and made no attempt to fire on the Australians

unless they tried to cross the river. A reconnaissance patrol of the 36th attempted this on the night of the 4th–5th January but found the Japanese wakeful and lost one man. A fighting patrol, rafting across the river next day, found the defenders still alert and lost several men killed and wounded. The 36th then settled down to harassing their enemies with fire and patrolling widely for flanking approaches. But though they crossed the river several times the spreading swamps blocked their closing movements. On the 12th, however, a determined patrol crossed at the river’s mouth, met no opposition and pushed on some distance along the coast. Their way led them through defensive positions and freshly-abandoned camps, which they estimated had been occupied by at least a battalion, but they met no Japanese. Other patrols followed on the 13th and 14th, but all returned with reports that the Japanese were leaving the Kumusi regions also. Barges were taking them away, the natives said, aircraft were bombing them and PT boats were attacking them at night. It was clear that any threat on the left flank had dissolved. There was, therefore, no risk when Lieut-Colonel Isaachsen, in obedience to orders received on the morning of the 14th, pulled back the bulk of the battalion to defend the Gona–Jumbora track against Japanese fleeing from the main battle area. North of them the 55th/53rd, who had already collected more than fifty Rabaul natives who had abandoned the Japanese, were awaiting Japanese moving along the coast.

Swift in execution, Wootten began his approach on Cape Killerton at 7 a.m. on the 15th, the 2/10th Battalion forming his advance-guard. Until shortly before noon the 2/10th moved fast along the track until it petered out among bush and swamp. The companies wallowed separate ways in search of it and Killerton village, which was lost to them in the forbidding marshes and tangled scrub. Nightfall found them still below the coast, perched in trees like wet fowls, or lying in water.

Next morning (as Major Trevivian recalled it) we pushed on through the bloody mangrove swamps. It was the hardest job I ever had in the army. Sometimes the water was over our heads, most times up to our arm-pits. Our rate of progress was about 100 yards an hour and we had to cut down pieces of mangrove to get the stores across. At that stage we were carrying ammunition, mortars and the heavy stuff—and I would like to record the sterling job that the mortar chaps did in that show. If there is one bunch of fellows I had respect for it was the mortars. Eventually we struck a track which ran along the beach and ultimately into Killerton village. We came on to that right by a Japanese position. The Japs were sunbaking at the time and it was a toss-up who got the biggest surprise. ... In the meantime, while the battalion was pushing along the coast, Cook’s49 company was sent off to find Killerton village. Until we found it we couldn’t accurately determine where we were. Nothing seemed to make sense as far as our maps and photographs were concerned. Eventually an aircraft was sent out to help but by that time we were on the objective and the thing was plain sailing.

The battalion (less Captain Cook’s company) then combed the coastline across the cape, struck at one or two isolated enemy parties and camped for the night with their most advanced company, Captain Wilson’s, at

Wye Point (a little more than a third of the way from Cape Killerton to Sanananda Point) and Wilson’s patrols flicking at Japanese outposts 200 to 300 yards farther along the coast. These were obviously guarding strong positions for, when Trevivian’s company passed through Wilson’s in the dawn of the 17th, they were sharply checked after 200 or 300 yards and drew back in the afternoon to allow the mortars to drop 45 rounds on the defences.

By this time the whole brigade was closing in on the main defence area. After Cook of the 2/10th had left his battalion on the morning of the 16th he led his company to a point almost two miles South-east of Killerton village from which he felt eastward for the Sanananda Track. By evening he was close to it. Wootten thereupon decided that the 2/12th should strike at the road along that line, and Arnold, with two companies, should thrust eastward from the Killerton Track through the last light and early darkness and come up with Cook about 8.30 p.m. and take him under command. Drenching rain fell during the night, with lightning hurtling through it, striking into the swamp water and shocking some of the men sharply. It so raised the level of the swamps that water lapped high about every movement of the Australians next morning. In the early light the rest of Arnold’s battalion joined him, leaving at the coconut grove the 39th Battalion which had come forward as the pivot in the communications line. The quest for the track then got under way again in a neck-deep torrent. By 11.30 a.m., however, Captain Ivey’s company were through this and astride the road, firing intermittently at Japanese who tried to pass them, and Cook’s men were astride it a little farther to the south, shooting their way northwards to link with Ivey. During the remainder of the day most of the rest of the battalion reached the road and, when night came, they were holding about 300 yards of it.

Not only did nightfall of the 17th find the 2/12th (with Captain Cook’s company) in position on the track above the Japanese who were still holding the Americans farther south, and the main body of the 2/10th pressing down the coastline from Wye Point to Sanananda Point, but it also found the 2/9th significantly poised. As with the 2/12th, Wootten used the 2/9th to penetrate through country which could reasonably be regarded by the Japanese as a sufficient obstacle in itself and which he could, therefore, expect to be less heavily defended than other lines of approach. Accordingly he sent Major Parry-Okeden South-east from brigade headquarters, just west of the village, on the 17th and then, from the area where Cook had bivouacked on the 16th, Northeast towards Sanananda Point itself. With the darkness Parry-Okeden then settled his men defensively in a large kunai patch about three-quarters of a mile in a straight line South-west of Sanananda Point. Next morning, after a night in which some ten inches of rain poured down, his men ploughed through mud and water up to their waists, crushed two strongpoints, cleared Sanananda village and point, and established one company (“A”) at the mouth of the river at Giruwa, for the loss of one killed and two wounded. They killed 21 of their enemies, made prisoner 22 Japanese

and Koreans and 21 coolies (most of them forced labourers from Hong Kong). “C” Company then swung southward along the Sanananda Track to help the 2/12th, cleared out two separate foci of resistance, but were held by a third with night coming on.

Reaching towards these men along the track from the south Arnold had opened the day by starting Curtis’ company of the 2/12th up the right of the track and Lieutenant Clarke, now commanding the company in place of Trinick, up the left. They advanced a cautious 200 to 300 yards without interference, but then Clarke’s men came against such determined opposition that, although they tried themselves against it in three distinct movements during the day, it remained obdurately in their path. And, on the right, although at first an easier passage than the left had seemed to be offering, Arnold deployed his other three companies without success during a day which cost him thirty-four casualties.

When his patrols reported early on the 19th that all the Japanese positions fronting them were still manned in strength, Arnold planned to use Cook’s company to try to break the deadlock on his left flank. Cook thereupon led his men forward at 8.50 a.m. and soon afterwards shot his success signal into the sky. Arnold himself wrote admiringly of this exploit:

The successful attack by “A” Company 2/10th Battalion on left flank was one of the outstanding features of this phase of the campaign. The position held by the Japs was almost entirely surrounded by water more than shoulder deep, except for small tongue of dry land about 15 yards wide and which was covered by enemy LMG fire. Under cover of a mortar bombardment this company infiltrated by twos and threes along this tongue forming up within 25 yards of the enemy. On a given signal they pushed forward with the bayonet under their own hand grenade barrage. The enemy resistance collapsed and the company advanced 500 yards killing 150 Japs many of whom were hiding in huts and captured three large dumps of medical and other stores. As in many other cases enemy wounded engaged our troops and had to be shot. This may give rise in the future to Jap propaganda but they are doing it so consistently that our troops cannot take any chances.

After this skilful action Arnold pressed forward west of the road to make contact with “B” Company of the 2/9th, which had taken over the forward positions from “C” Company early that morning. On the east of the road, however, the Japanese still refused to give way despite thrusts from the north by the 2/9th men and from the south by Captain Harvie’s50 and Ivey’s companies of the 2/12th.

These closing stages of the Sanananda struggle were made more horrible by the drenching rains and swollen swamps. Only the raised surface of the track rose above loathsome mud and water through which every movement had to be made. The struggle went on with movement on either side slowed as if by the leaden weights of a nightmare. With such movements did the men of the 2/12th and the 2/9th seek to link on the 20th. About the middle of the morning each of these groups drew back to allow the gunners to try to smash the defences. After that “C” Company of the 2/9th pushed once more through the slime from the north against the

remaining track positions while Arnold sent in Harvie’s and Ivey’s companies from the south and, when they could make little headway, pushed Cook’s company through them. But Cook likewise was checked and, although night found a ring closed round the Japanese defences by the linking of the two battalions on the east of the road, the last of the defenders still refused to die or yield. The toll they were exacting was mounting in a ghastly fashion, for the Australians along the track were losing some 50 or 60 men in killed and wounded each day, Cook’s company alone having lost 51 in his attacks of the 19th and 20th. On the 21st, however, Arnold rang down the curtain over this scene of mud, filth and death. His patrols reported early that morning that there was little opposition to be met, and then an emaciated prisoner confessed that only sick and wounded remained within the defences. The Australians closed in and 100 Japanese fell before them, while swollen and discoloured corpses of a hundred previously killed bumped against them in the swamp water or protruded from the obscene mud. The sickened Arnold wrote:

Since January 17 the battalion has been working in the worst possible country. Both flanks of the MT road are running rivers beyond which is nothing but jungle swamp. The road has been built up several feet with the surface of corduroy. In most places it becomes a causeway. As the result of our aircraft bombing large gaps occur through which the rivers run making all movement difficult particularly the supply of food and evacuation of wounded. The whole area, swamps and rivers included, are covered with enemy dead and the stench from which is overpowering. It is definitely the filthiest area I have ever set eyes upon. In a great many cases the Japanese bodies have been fly-blown and others reduced almost to skeletons.

The Australians had no wish to linger. In the early afternoon they went on up the road to the Sanananda–Giruwa coast where the 2/9th and 2/10th were still at work, while, from the east, the Americans were closing in.

A long pause had followed the crossing of Konombi Creek, before the Americans tried to resume their advance on the 16th under Colonel Howe. But the Japanese were still alert and stopped them with well-sited weapons which commanded the narrow approaches, and the whole surrounding country remained most inhospitable.

This damn swamp up here (said Howe) consists of big mangrove trees, not small ones like they have in Australia, but great big ones. Their knees stick up in the air ... as much as six or eight feet above the ground, and where a big tree grows it is right on top of a clay knoll. A man or possibly two men can ... dig in a little bit, but in no place do they have an adequate dug-in-position. The rest of this area is swamp that stinks like hell. You step into it and go up to your knees. That’s the whole damn area, except for the narrow strip on the beach. I waded over the whole thing myself to make sure I saw it all. ... There is no place along that beach that would not be under water when the tide comes in.51

Eichelberger, considering these and other remarks of Howe’s, told him that he might bring forward practically all of the 127th if he desired, and Howe set about pressing forward again on the 17th. But still he could measure his advance in yards only. Next day, however, resistance

weakened, and, on the 19th, with the aid of a 37-mm gun, the Americans virtually broke what opposition remained. On the 20th they took several machine-guns and a number of emaciated and dysentery-racked prisoners, and the late afternoon found them approaching Giruwa while, beyond it, they could see Australians of the 2/9th Battalion who had been at the river’s mouth since the 18th. Only sporadic shots met the Americans as they walked into Giruwa on the 21st. All about them in this part of the main Japanese base was death and desolation. In what had been the Japanese 67th Line of Communications Hospital

the scene was a grisly one. Sick and wounded were scattered through the area, a large number of them in the last stages of starvation. There were many unburied dead, and ... “several skeletons walking around”. There was evidence too that some of the enemy had been practising cannibalism. Even in this extremity the Japanese fought back. Twenty were killed in the hospital area resisting capture; sixty-nine others, too helpless to resist, were taken prisoner.52

While the Americans had been approaching Giruwa, “A” Company of the 2/9th had been killing fugitives attempting to cross the river by night and had seen barges coming in the darkness and taking off detachments of the garrison. Two of Parry-Okeden’s other companies (as has been seen) had been attacking alternately down the track while the fourth had been probing westward to help the 2/10th whose attempts to clear the coastline from Wye Point had been bitterly contested since the 17th.

On the two following days Trevivian, leading the forward company, found himself trying to edge ahead along a narrow strip of beach with the sea on one side and impenetrable swamp on the other. At high tide the strip might be twelve feet wide; at low tide it shrank to about two. The Australians found it impracticable to dig themselves in because seepage filled the holes almost as soon as they got beneath the surface of the sand. A man seeking cover would find himself with his head under water. The patrols were constantly at work trying to go round the right flank but the swamps defeated them. Typical was one fine attempt which progressed almost precisely 100 yards in four hours. The gunners did what they could but most of their shells fell into the sea or uncomfortably close to the Australian infantry. The only really effective help Trevivian could get was from the mortars. These were being fought with grim determination by Lieutenant Scott,53 a recently-arrived reinforcement officer. His bombs, which had to be carried forward from the village, were rationed, but he and Trevivian developed a technique of movement which alone enabled the advance to continue. Scott would lay down his bombs, Trevivian’s men would seize another few yards of ground in their wake and then lie pinned beneath the Japanese fire until more bombs were brought forward. Two days were thus consumed. On the 20th, however, behind an effective mortar and artillery barrage Trevivian’s men gained about 500 yards, capturing several machine-guns, with their ammunition, and killing

some 40 Japanese, though the Australian losses about equalled those of their enemies. Among the Japanese dead was the Lieut-colonel who had been commanding a dual-purpose gun which had been the Australians’ chief worry. Trevivian killed him as he stood dazed beneath a small Japanese flag which he had tacked to a mangrove, his sword at the ready. Although the Australians did not get the gun itself it worried them less after that. None the less they were well held again from 8 a.m. onwards. Then, as the morning advanced, they withdrew to allow Parry-Okeden’s mortars to come into play from the other side of the sorely-beset Japanese pocket. These still did not break the Japanese will and, in trying to move forward, Trevivian’s company were once more blocked although, tantalisingly, they could see men of the 2/9th less than 300 yards away. Geard then brought forward Captain Matheson’s company and got them round his right flank to come under Parry-Okeden.

Brigadier Wootten now planned the destruction of the men he had at bay. He ordered Parry-Okeden to push his own men into the pocket from the South-east next day while Matheson’s men converged from the Northwest. A carefully planned artillery program was to precede the movement, which Wootten timed to begin at 9.30 a.m. on the 21st. These plans went awry, however, when the guns failed to find the target area, and it was not until the 22nd that the two battalions swept the last resistance away and reported at 1.15 p.m. that they had joined forces and organised resistance along the coast was ended.