Chapter 3: Defence of Lababia Ridge

LATE in 1942 General Blamey had been contemplating action against Lae and Salamaua. After the victory at Oivi–Gorari, north of the Owen Stanley Range, he had hoped to reach Buna and Sanananda quickly, and had even arranged for supplies to be sent by ship to Oro Bay to enable him to make a quick attack on Salamaua and Lae. This hope had been disappointed, and it was not until late in January 1943 that the Japanese had been finally cleared from the Papuan beaches. The price of the Papuan victory was the exhaustion of four of the six brigades of the 6th and 7th Divisions. Experience had shown that the AIF brigades must be the spearhead of the next offensive as their training and battle experience had made them by far the most efficient troops in the South-West Pacific. Until the 6th and 7th Divisions could be rehabilitated in Australia and until the returning 9th could be trained for jungle warfare the period was, of necessity, one of marking time and planning for an offensive.

The Japanese, after their defeats in Papua, at Wau, and in the Solomons, had also paused for regrouping and replanning in the South-West Pacific and South Pacific Areas. Blamey was sure that the Japanese were embarking in New Guinea on a long-range plan involving first, the establishment of a land route from Madang to Lae; secondly, the defeat of the Australians in the Wau–Salamaua area; and thirdly, a southward move against Port Moresby.

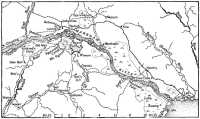

By the end of the Papuan campaign Blamey and his New Guinea Force commander, Lieut-General E. F. Herring, were emphasising the complementary nature of air and ground action in operations in New Guinea. “Each forward move of air bases,” they wrote in their respective reports, “meant an increase in the range of our fighter planes and consequently an increase in the area in which transport planes supplying our troops could be operated. To get airfields further and further forward was thus the dominant aim of both land and air forces.” Obviously the next suitable area for airfields was the valley of the Markham River whence the Vitiaz Strait, between New Guinea and New Britain, could be controlled. Gradually, ideas took a more definite form and resulted in an outline plan to capture Lae and the Markham Valley. Lae would provide a land base to which supplies could be transported by sea, while the Markham Valley was flat and would provide excellent areas for airfields particularly in the Nadzab area.

On 7th May General MacArthur had issued an instruction based on his orders from the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, outlining the offensive which the forces of the South-West Pacific and South Pacific would carry out in 1943. As part of these operations New Guinea Force was given the task of seizing the Lae, Salamaua, Finschhafen and Madang

areas. Provision was made for an operation in the Salamaua area to take place as a “feint” on 30th June when other operations were due to take place on Kiriwina and Woodlark Islands and on New Georgia in the Solomon. Further details of MacArthur’s order will be given later.

General Herring had left New Guinea for leave late in January. On 10th May he returned to Brisbane and there conferred with staff officers of Blamey’s Advanced Land Headquarters and with Rear-Admiral Daniel E. Barbey, the commander of the American Amphibious Forces. Blamey arrived in Brisbane on the 15th and next day he and Herring had a long conference with a model of the Salamaua and Lae areas before them. Blamey explained his plan, which provided for two phases; the first entailing the capture of Lae and the Markham Valley and its airfields, and the second exploitation round the coast to Finschhafen and Madang. To capture Lae a seaborne landing would be necessary. “This in turn,” wrote Blamey in his report, “demanded the prior seizure of a shore base within 60 miles of Lae, this being the maximum range of the landing craft which would carry the troops by night to the assault. Nassau Bay was selected as the area most suited for the purpose since its capture would also enable a junction to be made with our forces operating at Mubo and consequently reduce the problem of maintenance of their supplies. I instructed GOC, New Guinea Force, to carry out a preliminary operation for the seizure of Nassau Bay and for its protection as a base to assist the larger operation. With this latter end in view he was directed to seize the high ground around Goodview Junction and Mount Tambu and the ridges running down therefrom to the sea. Beyond this, however, he was not to go.”1 As it seemed essential that Nassau Bay should be captured as soon as possible, Blamey intended that his “preliminary operation” should take the place of MacArthur’s “feint”. “We realised we had to do something more,” wrote Herring later. “We had to capture Nassau Bay and hold it and this being so, we thought that quite conveniently it could be fitted into the operation that we had in mind for 3 Div.”

In discussion with Herring Blamey pointed out that the preliminary operation to capture Nassau Bay would not only enable a junction to be made between the landing force and the Australians at Mubo, but would increase the threat to Salamaua and perhaps draw enemy reinforcements from Lae to Salamaua. This idea, so fundamental to the success of the offensive, was described by Blamey in his report:

If the enemy’s attention could be concentrated on the operations for the capture of Salamaua there was every chance that he would drain his strength from Lae by reinforcing his forces south of Salamaua and that any discovery of further preparation on our part might lead him to believe that we were preparing for heavier action against the latter area. Thus the operations round Salamaua might have a decisive part in the capture of Lae.2

Herring summed up the matter more picturesquely when he wrote later that Blamey “wanted the operation against Salamaua to serve as a cloak

for our operations against Lae, and to act as a magnet drawing reinforcements from Lae to that area”.

Blamey’s opponent in New Guinea, General Adachi, later stated that the object of the Japanese was to hold Salamaua in order to delay the advance of the Australians and Americans as long as possible. He considered Salamaua “a very strategic position” which was to be held at all costs and was to be defended to the last man. Adachi considered that, should Salamaua fall, Lae would definitely be lost as its security depended on the Salamaua defences. The strength of the Salamaua garrison was accordingly built up to about 5,000 troops with troops from Rabaul, New Ireland, Lae, and Wewak.

Blamey’s instruction of 17th May was handed to Herring in Brisbane. It was addressed to Herring by name and the distribution list was very limited. Herring took this written instruction with him when he returned to Port Moresby on 22nd May. Next day he resumed command of New Guinea Force and General Mackay returned to the command of the Second Army in Australia. At this time Herring was the only Australian in New Guinea who knew the plan. He was now beginning his second period in command of the force in New Guinea, having commanded the I Corps and New Guinea Force in the later stages of the fighting in the Owen Stanleys and on the Buna coast until the end of January.

New Guinea Force at the end of May numbered 53,564 Australian soldiers and 37,200 Americans. In addition there were about 9,000 men of the RAAF and 19,100 of the American Army Air Force in New Guinea. The Australians estimated early in May that between 31,600 and 34,200 Japanese troops were deployed in Australian New Guinea with a further 38,000 in Dutch New Guinea and the Banda Sea islands. As mentioned earlier General Savige had a brigade headquarters with four battalions and an Independent Company in the battle area, and another brigade headquarters (the 15th) and another battalion – the 58th/59th – were moving in. Major-General Milford’s 5th Australian Division (4th and 29th Brigades) garrisoned Milne Bay and Goodenough Island. The 41st American Division was in the Buna–Oro Bay area; and in Port Moresby Major-General Clowes’ 11th Division included the 7th Brigade and the remaining battalion – the 57th/60th – of the 15th Brigade. New Guinea Force also controlled the Papuan Infantry Battalion in Port Moresby and Bena Force, far off in the Bena–Mount Hagen plateau.

In the actual Lae–Salamaua battle area the Intelligence staff of New Guinea Force estimated early in June that Japanese strength had grown to about 7,025. Of this total 1,500 were thought to be round Mubo, 400 in the Bobdubi area, 250 in the Duali–Nassau Bay area and the remainder in Lae and Salamaua. It was also estimated that the Japanese had 105 aircraft (50 bombers, 50 fighters and 5 float planes) on New Guinea airfields. General Kenney’s Fifth Air Force deployed far more aircraft than that. In the whole South-West Pacific Area (in April) there were some 690 serviceable aircraft in the Australian squadrons and 770 in the American. In New Guinea were nine American and two Australian fighter squadrons; a third Australian fighter squadron arrived in June.

Three days before General Herring’s return, General Savige had received a note from New Guinea Force stating that “our forces are to occupy Kiriwina and Woodlark Islands for the establishment of airfields thereon”, and that New Guinea Force would cooperate in this operation. Savige was warned to be ready by 15th June to “threaten Salamaua by aggressive overland operation from the Wau–Bulolo valley and by threats along the coast from the Morobe area”. This warning was based on MacArthur’s instruction of early May, but it was ill-framed, for Savige then had no troops on the coast to advance from Morobe. An instruction to “threaten” Salamaua could be construed as giving the green light for an attack on Salamaua – an event which would strike at the very basis of the plot being hatched by Blamey. The note continued that New Guinea Force hoped to transport to Wau most of Savige’s units still in Port Moresby (110 officers and 2,447 men) within 14 days. Based on the assumption that he would have two Australian brigades each of three battalions and at least one Independent Company, Savige jotted down his preliminary thoughts on this instruction and noted: “We must get clarification of the words ‘threaten Salamaua’. It may mean ‘secure’ Salamaua or continue our present tactics on a bigger scale.”

On 18th May New Guinea Force had ordered that Colonel Wilton be sent to Port Moresby to be given “special information” based presumably on the General Headquarters’ order. At this time Wilton was absent in the Cissembob area and it was not till the 23rd May that he arrived at Port Moresby. Herring gave an outline of forthcoming operations to Wilton and to Colonel Kenneth S. Sweany, the chief staff officer of the 41st American Division at Morobe. On the 27th Wilton returned with a copy of an operation instruction3 issued to the commanders of the 3rd Division, 41st American Division, Fifth Air Force, and American PT (Patrol Torpedo) Boats.

The object of the pending operations was “to bring about offensive overland action against Salamaua from the Wau–Bulolo area and along the coast from Morobe, without jeopardising the defence of our bases in New Guinea”. Savige’s task was defined as ultimately to drive the enemy north of the Francisco River by aggressive action as soon as practicable; and immediately to establish a beach-head at Nassau Bay in order to open a sea line of communications into the Mubo area and enable American forces to operate in conjunction with the Australians. The task of Major-General Horace H. Fuller, commanding the 41st Division, would include ensuring the security of New Guinea east of the Owen Stanleys from Oro Bay to Morobe, moving a battalion group to secure the Lasanga Island–Baden Bay area three days before D-day as a base for operations northwards along the coast, and arranging for the landing of the battalion group at Nassau Bay whence it would cooperate in driving the Japanese north of the Francisco.

The Fifth Air Force, now gaining control in the air, would defend New Guinea bases against the enemy air force; carry troops and supplies and maintain them; prevent reinforcements or supplies reaching Salamaua by sea; reconnoitre and attack targets in the Lae–Salamaua–Sachen Bay area; and directly support the ground forces. The American PT group would attack enemy sea forces in the Huon Gulf in cooperation with the air force, protect the ground forces whilst seaborne and during movement along the coastal area from Oro Bay to Salamaua. All were warned to be ready by 15th June and it was plainly indicated that command of ground forces in the battle area would be exercised by Savige.

Mackay’s warning order of 20th May was now cancelled by Herring’s instruction of 27th May, but both served to make Savige all the surer that his objective was Salamaua. On 29th May he issued his own orders in which his intention was “to destroy the enemy forces in the Mubo area and ultimately to drive the enemy north of the Francisco River”. He considered that the enemy forces in the Mubo area must first be destroyed in order that the line of communication from Nassau Bay to Mubo might be successfully opened. The operation for the capture of Mubo would take place in three phases. First, on the night before D-day, an American battalion group would land at Nassau Bay. Secondly, the newly-arriving 15th Australian Brigade would capture Bobdubi Ridge on D-day while small forces raided the Malolo and Kela Hill areas, North-west of Salamaua, to distract the enemy’s attention from the Bobdubi attack. After the capture of Bobdubi Ridge this brigade would advance south to Komiatum and prevent the escape of the enemy northwards from Mubo. Thirdly, a battalion of the 17th Brigade and the American battalion group would attack the Japanese forces in the Mubo area – preferably not later than six days after the Bobdubi attack – and, after the capture of Mubo, would advance north towards Komiatum and North-east towards Lokanu. While these main operations were proceeding the 24th Battalion would harass Markham Point and provide a strong fighting patrol to move to the mouth of the Buang River and establish an ambush position on the coastal track one day before D-day to prevent enemy movement along this track in either direction.

The 17th Brigade was given the task of reconnoitring the shores of Nassau Bay to confirm whether any enemy defences existed and also to decide whether the beach was suitable for an unopposed landing. “It is essential,” said Savige in his order, “that the movements of this recce party be not observed by the enemy.” The 17th Brigade would also send a patrol along the south bank of the south arm of the Bitoi, and, three days before D-day, would establish a strong company patrol base as close as possible to the coast. On the day before D-day this patrol would create a diversion at Duali and on the night of the landing would provide a beach party to establish signal lights facing seawards. Moten was also ordered to detail a liaison officer (Savige suggested Captain McBride4 of the

2/5th Battalion) to move with the American battalion group. After establishing a beach-head in the Nassau Bay area at a spot selected after detailed reconnaissance by the Australians, the Americans would destroy enemy forces at Duali and Cape Dinga, and then move to Napier and come under Moten’s operational command.

General Herring’s concern was now to tie up the operations of the 3rd Australian and 41st American Divisions for the landing at Nassau Bay. After outlining plans to the two senior staff officers – Colonels Wilton and Sweany – he summoned the two generals – Savige and Fuller – for a conference at Port Moresby on 31st May. Savige and Fuller rapidly reached agreement on the main points. On the question of beach lights, Savige had planned to have red lights on the flanks and a white light for signalling in the centre, but when Fuller wanted them the other way round, Savige agreed. Most discussion centred on the size of the Australian force to cover the landing at Nassau Bay. Savige was startled to find that Fuller had been pressing Herring to have a battalion on the beach. This was obviously impossible, for not only did Savige not have a battalion available for such a task, but, even if he had, he could not move it or supply it across the terrible country which he called the “Unspeakables”. Savige believed that a platoon was adequate for the job but he did not say so. When Fuller persisted in his request for a battalion, Savige countered by saying that he would not be able to scrape together a full battalion, but that he would guarantee an “adequate force”.

After the discussion, Fuller drafted “notes on agreement” between the two divisional commanders. Savige agreed with these, which set the tentative date for opening the operations as the night 16th–17th June, requested that the Australian liaison officer should know the country, that guides from 17th Brigade should lead the Americans to an assembly area preparatory to the Mubo action, and that the Australians should make a demonstration on the afternoon before the landing. The lights would be lit only if the beach was clear, and finally the Australians would “block approach to beach from both ends with adequate force”.

Considerable reorganisation was taking place in Savige’s area at this time. In the Mubo area the relief of the 2/7th Battalion by the 2/6th was completed on 2nd June, when Colonel Wood opened his headquarters at Guadagasal. By 28th May the 2/7th Independent Company had been flown into Bena Bena, and Bena Force now came under Herring’s direct command. Between 25th and 31st May 49 officers and 784 men of the 15th Brigade headquarters and the 58th/59th Battalion were flown from Port Moresby to the Bulolo area.

The 3rd Division had originally consisted of the 4th, 10th and 15th Brigades. The 4th had been detached to the 5th Division and the 10th broken up. The 15th was an amalgamation. The original battalions of the 15th Brigade stationed at Seymour in 1941 had been the 58th, 59th and 57th/60th. In 1942 the brigade trained at Casino in New South Wales and later at Caboolture in Queensland. Here the 24th Battalion had

joined it from the 10th Brigade and the 58th and 59th were merged to form the 58th/59th. Brigadier Hosking,5 chosen by Savige, had also come from the 10th Brigade to command the 15th. Changes in unit identity – a proud possession of soldiers – and late changes in command had an adverse effect on the brigade, particularly on the 58th/59th. The brigade had arrived in Port Moresby in January 1943. Brigadier Hosking and Lieut-Colonel P. D. S. Starr (the former commander of the 2/5th Battalion at Wau) who had been chosen by Savige at Mackay’s suggestion to command the 58th/59th after its arrival in New Guinea, prepared at the end of May to move to the Pilimung and Missim areas respectively.

West of Bobdubi Ridge the 2/3rd Independent Company was in reserve, enjoying the bracing climate and hot mineral springs of Missim, with a company of the 24th Battalion at Pilimung under command. Manned by men of the Independent Company, Wells OP was paying full dividends. On 5th June it reported that during the past five days there had been a continual procession of Japanese and carriers, thought to be Chinese coolies, passing north and south along the Komiatum Track mainly between the hours of 2 and 3 p.m. For instance, on this day 208 Japanese had moved south towards Komiatum from Salamaua while 110 had moved north towards Salamaua.

To the north the remainder of the 24th Battalion was given the task of preventing the Japanese from entering the Bulolo Valley, defending Zenag and Bulwa airfields, and patrolling to the Markham. To ease the ever-present problem of supply, not more than two companies were to move beyond the jeep-head at Sunshine without reference to divisional headquarters. After a patrol skirmish near the Markham on 3rd June, the 24th reported that the Japanese had reoccupied their old camp site at Markham Point. Another patrol attempting to set booby-traps near the Japanese camp was fired on and forced to withdraw. On 9th June, after the forward observation post had heard explosions and seen fires from the direction of Nadzab, Savige ordered that a small patrol should cross the Markham to obtain information of Japanese movement in the Nadzab area and, in particular, of any activity on the airfield.

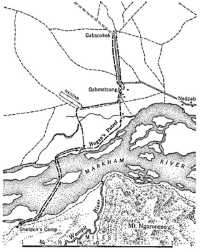

In the Mubo area, which the 2/7th Battalion had vacated, one company of the 2/6th was on Lababia Ridge with a platoon at Napier, a second company was at Mat Mat, a third at Summit, and the fourth at the Saddle. Both the 2/5th and 2/7th Battalions were in the Wau area.

The company commander on Lababia Ridge, Major Dexter, changed the Lababia defensive position by withdrawing it to the higher ground at the junction of the Lababia and Jap Tracks where he considered it would be less difficult to counter another enemy attempt at encirclement. One of the company’s first patrols along the Jap Track towards the Pimple on 2nd June heard voices and chopping in the position previously occupied by Captain Tatterson’s company of the 2/7th. Moten was concerned at

this movement by the enemy south of the Pimple, and told Wood that the Australian positions were too far removed from the Pimple either to restrict or to observe the enemy movement, and it would be possible for the Japanese to move a force from the Pimple and cut the Lababia Track, “which action would be detrimental to the success of POSTERN” (the code name for the offensive). On 4th June he ordered Wood to place a small force near the south end of the Pimple from which enemy movement could be seen or heard, and to patrol constantly to both flanks so that the enemy could not move in force from the Pimple without being detected. Dexter carried out this direction by placing a semi-circle of listening posts south of the Pimple.

Moten’s order to Wood coincided with reports from the Independent Company’s observation posts, particularly Wells OP, of considerable activity along the Komiatum–Mubo track. Dexter’s patrols were busy for the next few days to the south, east and west of the Pimple, and, although no shots were exchanged, the usual talking, coughing, chopping and rattling of mess tins suggested that the Japanese were still in the area south of the Pimple. So dense was the jungle that on 5th June a patrol stayed within 30 yards of the enemy position during the day, hearing voices but not seeing any Japanese.

In other areas occupied by the battalion patrols which may have seemed routine were in fact preparing for the offensive designed to end the stalemate.

Detailed plans for action before and after the American landing were now being formulated by Moten, his brigade major, Eskell,6 and his staff captain, I. H. McBride. But the plans of force, division, brigade and battalion hinged on information as yet unknown. For the task of reconnoitring the beach at Nassau Bay and a track through the area of swamp and foothills along the lower reaches of the Bitoi, Lieutenant Burke7 was chosen. Burke set out with Sergeant Ellen and three others from Napier on 2nd June with instructions to return to Napier and submit a report by 5th June. Sometimes moving along the track running along the south arm of the Bitoi and sometimes breaking bush over and round the foothills and spurs, Burke’s patrol finally came to the last of the spurs running in a North-easterly direction down to the Bitoi about two miles from the

coast. From the spur the men could see Nassau Bay, although the shape of the spur prevented them from seeing Duali and Lababia Island. As it was then 2.30 p.m. on 4th June the patrol returned to Napier, where Burke reported that it was doubtful whether a proposed signal fire on Lababia Ridge could be seen from the beach. (At this stage it was intended that the arrival of the Australians at the beach on D-day should be signalled with bonfires.)

Moten ordered Burke to carry out his original task after a day’s rest and to return to Napier by 13th June. Burke, accompanied this time only by Ellen, set out again from Napier at 8 a.m. on 7th June.

The two men followed the route blazed by Ellen and his two companions in April. After travelling along the dry creek bed for an hour Burke and Ellen set off southward following a native pad up a re-entrant and into the range of hills to the south of the Bitoi. Continuing in a south-easterly direction, they crossed a mountain range at a saddle about 2,500 feet high, and five hours after leaving the Bitoi reached Tabali Creek where they camped on the night of 7th–8th June. In the morning they crossed Tabali Creek, which at this point was steep with a hard stony bed. A faint native pad which they followed on the other side disappeared after three hours in a dry creek bed which continued in an easterly direction for 300 yards until dense swamp and jungle prevented further movement except by cutting a track. Hacking their way east, Burke and Ellen four hours later again reached the winding Tabali where they camped for the night of 8th–9th June surrounded by swarms of mosquitoes and drenched by heavy rain. Next morning they swam the Tabali which had flooded overnight and at this point was 40 yards wide, slow-moving, overgrown and about 10 feet deep close to the banks. After marching for an hour and a half through swamp country the two weary men reached a clearing 100 yards from the coast.

This clearing was about 400 yards long and 100 yards wide and went right to the water’s edge. There were signs of a camp near the shore and abandoned weapon-pits with the revetting timber rotting. An indistinct track wound north and south. They considered the flat beach an excellent one for landing flat-bottomed craft. The beach bank was about 10 yards from the water’s edge and 6 feet above sea level. They estimated that there would be good cover for the landing craft provided an Australian platoon held the beach. They returned to Napier in nine hours arriving there at 6 p.m. on 9th June. “We reached the bay, had a very quick look round then got to hell out of it,” wrote Ellen later. A high degree of determination and pioneering ingenuity had enabled the two men to carry out their difficult task.

Burke’s conclusions, on which Moten could now base his detailed orders, were that the route was a good one, the beach was suitable for the landing, protection would be available for the landing party, the enemy did not occupy the area although they may have patrolled it regularly, and the strip of coast from the mouth of the south arm of the

Bitoi to Nassau Bay could quickly be made suitable even for motor transport.

When the time element had prevented Burke’s first patrol from reaching the coast, Moten had decided to make sure that at least one patrol would reach the Nassau Bay area. He had therefore sent out another two-man patrol from the 2/6th Battalion – Lieutenant Gibbons8 and Corporal Fisher9-on the same day as Burke’s second patrol. Leaving Napier, Gibbons and Fisher followed the track along the south arm of the Bitoi towards the coast. At 11 a.m. on 8th June, Dexter, who was then visiting the Lababia OP, sent an ominous report to Wood of heavy mortar and machine-gun fire coming from the direction taken by Gibbons’ patrol. Twenty-four hours later Fisher wearily returned to the junction camp alone.

He said that after bivouacking the first night about a mile and a half from the sea, whence they could clearly hear the surf, they set off slowly at 6.30 a.m. on 8th June along the well-defined track and followed it for 45 minutes. They then saw fresh Japanese footprints on the track for another 10 minutes. Gibbons who was five yards in front of Fisher suddenly stopped, turned round, said “Jap” and moved back towards Fisher, who saw the Japanese behind a banana tree on the north side of the track about five yards from Gibbons. The Japanese fired and Gibbons fell. Fisher fired and thought that he killed the Japanese. After Gibbons had waved him back Fisher broke bush on the south side of the track about 100 yards back. He waited and saw Gibbons staggering back along the track. Gibbons then disappeared, and, as Japanese were now moving west along the track firing machine-guns and mortars indiscriminately, Fisher zigzagged back along the track for 300 yards, fell into a fresh weapon-pit, crossed to the north side of the track and reached the south arm of the Bitoi. From the firing he gathered that the Japanese were now ahead of him on the track.

Suffering that hopeless hunted feeling when the future seems black, Fisher struggled back through the great loneliness of the jungle towards Napier. After being swept downstream by the Bitoi and lost in a pit-pit swamp he finally rediscovered the track and returned to Napier in a shocked condition.

Major Takamura, commander of the III/102nd Battalion, was very pleased with Superior Private Koike who shot Gibbons. In a letter of commendation Takamura wrote on the same day: “While on sentry duty at a point 300 metres in front of the patrol at the banana plantation, he sighted an enemy patrol of 3 men, each armed with an automatic rifle at around 0940 hours. Signalling to the neighbouring sentry, he coolly prepared to fire, and awaited the approach of the enemy. The enemy approached step by step carrying their automatic rifles in readiness. He waited until they approached within 10 metres, and then fired, killing one man and causing the other two to retreat in haste. He captured one automatic rifle, 4 magazines, a sketch map and a pocketbook, etc., which were of great value to future operations.”

The map captured by Koike was the Mubo 1:25,000 sheet which was the main map used in the Australian area. Takamura realised that plans for an offensive were being prepared for in a special order issued on 11th June he said: “On 8th June in the battle in the area on the right arm of the Naka River [south arm of Bitoi] a captured sketch map together with records from enemy who were killed and secret activity of natives all indicate that the enemy is planning and in a position to attack.”

During early June two important and successful patrols were carried out by other members of Dexter’s company in preparation for the coming offensive. Corporal McElgunn and Private Rose10 patrolled from Napier, intending to reach the coast by a route north of those taken by Burke and Gibbons. After moving through extremely difficult country on the outward journey McElgunn reached the beach about half way between Duali and the mouth of the north arm of the Bitoi. He returned along the north arm with information that no enemy activity was taking place along the coast north of Duali. Sergeant Hedderman11 led a patrol which pioneered a route to Bitoi Ridge in readiness for the advance of the Americans towards Mubo, and managed to reach a point from which he could overlook the Mubo–Komiatum track along Buigap Creek. Both McElgunn’s and Hedderman’s patrols were the first to reach these objectives. From 5th June Lieutenant Johnson12 and Sergeant Gibson13 were detached from their platoon on Lababia Ridge and stationed with Lieutenant Urquhart’s platoon at Napier whence they would prepare two suitable routes on to Bitoi Ridge. Sergeant Daniel14 from the Pioneer platoon was also sent to Napier to build shelters for the Americans.

Throughout Savige’s area the troops were supplied by native carriers, or “cargo boys”, who transported ammunition, rations and supplies from the airfields and dropping grounds to various units. It was largely the skilful and careful planning of his senior administrative officer, Lieut-Colonel Griffin,15 and the devotion of the native carriers that made it possible for the mountain-based Australians to continue the fight against the sea-based Japanese.16 As far as possible the natives were kept away from the area where the bullets were flying; there the supplies were carried by their white employers and friends. On return journeys the

natives acted as stretcher bearers for wounded and sick Australian soldiers, an arduous task which they performed with great solicitude.

An organisation which played a major role in maintaining this lifeline of supplies was the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit – or Angau. In the field the Angau officers and NCOs assisted commanders in the control of native labour, advised on matters peculiar to New Guinea, and gathered information. They were responsible for the local allocation and marshalling of native carriers, organisation of carrier lines between staging points, and the administration of punishment to natives for pilfering. Quite soon Savige saw trouble brewing in the “boy lines” mainly because of the fact that control was in the hands of the combatant officer while the Angau officer or NCO was relegated to a subordinate position. On 9th June he issued a clarification designed to avoid clashes of temperament between some local commanders who considered they knew how to control natives and some Angau officers who considered they knew how to command troops. Members of Angau on the lines of communication were to be subject to direction by senior local commanders at each staging point concerning the duties to be performed by native labour, but they were to be responsible directly to Angau headquarters for the internal economy and administration of allotted native labour. Attached to his headquarters Savige had Major D. H. Vertigan of Angau, while Captain H. McM. Lyon was with the 17th Brigade and Lieutenant G. K. Whittaker with the 15th. All were old New Guinea hands whose advice was much respected.

An example of the value of Angau was provided on 11th June when, between 7.25 and 7.40 a.m., four Beaufighters strafed Wood’s headquarters on Guadagasal Ridge instead of Green Hill and the Pimple. Two natives were wounded, but the calamitous aspect of the mistake was that 300 native carriers went bush. Angau assembled them again, but without Angau it might well have proved impossible to round them up and get them back to the carrier lines.

Because of what he called “unavoidable inactivity” in the Missim area, General Savige on 10th June ordered Brigadier Hosking to harass the Japanese supply route between Salamaua and Mubo but not in such a way as to indicate the main objectives of the coming offensive nor the area from which it was to be launched. He suggested that a force from the 2/3rd Independent Company, now included in Hosking’s command, should be employed, but that the Independent Company should be relieved of all its present commitments by a company of the 58th/59th Battalion which had now arrived at Selebob after a gruelling march from Bulwa. Two days later, in accordance with this order, Major Warfe ordered Captain Menzies to attack between Komiatum and Mubo by raid or ambush at a point no farther north than Stephens’ Track and to make every attempt to take prisoners.

Menzies at once began to concentrate his men, who were widely scattered on patrols, and to organise his supplies. Setting off from Wells

OP with a strong raiding party, he moved south over the Pioneers Range and worked his way towards the enemy supply line over rough, disused tracks. On 16th June Warfe received word that the party had run into a booby-trap, Menzies and three others being wounded. Menzies had travelled for some time and must have reached the scene of earlier operations in the Mubo area. The booby-trap encountered was made with Australian grenades and Australian trip wire. Once again the Australians learnt from tragic experience the effectiveness of their own grenades. Thirty-two native stretcher bearers were required to carry the wounded to Missim. The medical officer, Captain Street, met the party on its way in and gave the men what attention he could during an overnight halt at Base 4. Medical orderlies accompanied the party for the rest of the journey. Menzies and two others recovered, but Private McDougall,17 a boy of only 17, died soon after reaching Missim.

The disabling of Menzies left the platoon without a commander and Captain Hancock took over. The platoon had not had any respite since their arrival in the Missim area and the 22 men who were still fit for duty were very tired. However, days had passed since the order had been received to strike at the Komiatum–Mubo track south of Stephens’ Track, and to take prisoners if possible.

Hancock decided to approach by the quickest route. He moved with Sergeant Tomkins18 and a small party along the ridge of the Pioneers Range in the general direction of Mount Tambu. Guided by Corporal Lamb, who had spent many weeks patrolling in this area, he continued directly along the ridge not far south of the junction of Stephens’ Track and the Komiatum Track leading to Goodview Junction. The ridge descended steeply to the enemy track but provided a definite means of access and the terrain permitted an almost “text book” ambush position. There was flat ground near the track with a line of undergrowth along the track and a small hill near by which gave a view over short stretches of the enemy track in each direction. On 20th June the party took up position – the plan was to capture the last man of any enemy party which passed and to shoot the remainder. A long jungle vine was laid between the ambush party and the supporting party on the hill in order to transmit signals between them. Just as Hancock was completing the siting of the supporting party three Japanese appeared from the direction of Mubo. Hancock gave the pre-arranged signal and, as the Japanese passed, Lamb rushed forward on to the track closely followed by the rest of the party. Unfortunately the scrub beside the track was thick enough to give the enemy warning and the Australians were forced to shoot it out with them. The Japanese were killed, dragged off the track and relieved of their arms and equipment. The loot included official papers and diaries, which were immediately sent to Missim. Later the unit learnt that the papers gave parade states and other useful information about the enemy in the

Lower Markham River Valley area

Mubo area: the three men had been members of the II/102nd Battalion probably returning to Salamaua after their unit had been relieved by the 66th Regiment. On the 21st June a listening post established above Good-view Junction heard sounds of running, dropping of tins, shouted orders, cursing and general, commotion; it was clear that the bodies had been discovered and that the raid was causing a due amount of consternation.

Meanwhile, the newly-arrived 15th Brigade headquarters began to scent action; and on 15th June it issued its first operation instruction, signed by the brigade major, Travers.19 The brigade’s tasks on entering the Missim area would be to prevent the enemy from entering the Bulolo Valley through its area of responsibility; to secure the Missim–Pilimung–Hote area as a firm base to enable offensive raids to be carried out towards Komiatum and Salamaua when ordered; to plan the capture of Bobdubi Ridge and exploitation to Komiatum; and to reconnoitre and plan for a diversion against Salamaua in the Malolo area. The 2/3rd Independent Company, with a company of the 24th Battalion and one of the 58th/59th under command, was allotted the task of controlling the main tracks and establishing defensive positions in the Cissembob–Daho area to protect the brigade’s left flank and provide a base for patrols towards Salamaua along the Hote–Malolo track.

In the Markham area a daily patrol moved forward to observe the Japanese camps at Markham Point and on Labu Island in the Markham, half an hour’s walk beyond. When first discovered the Markham Point camp had been deserted and had consisted of 12 weapon-pits on a sharp rise, almost a cliff face, 40-50 feet high, running at right angles to the

14th–18th June

river. By 11th June the Japanese were protected by ambush positions 150 yards west of the cliff-face position, while the huts were let into the side of the ridge of the precipice like blast bays of an airfield.

In pursuance of Savige’s order that a small reconnaissance patrol from the 24th Battalion should go to the Nadzab area, Sergeant Eaton20 with two men and a native left at 5.30 p.m. on 11th June to cross the Markham. During the crossing one boat swamped causing the two other members of the patrol to spend the night uneasily on a sandbank and return to Old Mari the next morning. Eaton and a native guide reached the north bank of the Markham, but returned at 8.30 p.m. next day after their boat had capsized on the return trip. Major Smith obtained permission for Eaton’s patrol to be repeated.

Sergeant Hogan,21 Lance-Corporal McInnes22 and Private O’Connor23 set out on the second Nadzab patrol on 14th June, and returned four days later. The patrol crossed the Markham by moonlight in rubber boats which they hid in the reeds, and then moved east along the north bank of the river and north to Gabmatzung across what the natives called “Big Road”, and on to Gabsonkek. As the natives were very friendly, Hogan stayed there during the night 17th–18th June and gathered information. “Natives say,” Hogan wrote in his report, “that the Japs come to the village every day between 1000 and 1200 hours taking everything in sight – pigs, fowls, fruit, etc., without paying; they take native girls back to Lae if they can catch them.” The guides would not proceed farther to Ngasawapum because “Japan man come up Big Road, cut us off”, and they would not go to Narakapor because they claimed there were “too many Japs and two big guns”. Native information gathered by

Hogan from the Gabsonkek “boss boy”, who had been forced to carry cargo to Lae, was that 300 Japanese had recently crossed the Markham with the intention of going to Oomsis; 200 Japanese patrolled daily from Heath’s Plantation where “Jap dig hole”; 100 to Gabmatzung and 100 to Chivasing; one kiap [European official] and five police boys had been killed by the Japanese; and natives would not cross the river now unless with a patrol. At 6 a.m. on 18th June Hogan’s patrol retraced its steps while the Gabmatzung natives obliterated all traces of them in the village and on the track. Moving west along the disused motor road the patrol came to the Nadzab airfield which was overgrown by kunai three to six feet high. Hogan finally reached the south bank of the Markham at 10 p.m. after an exceptionally fine patrol.

After Hogan’s return Captain Kyngdon24 of Angau questioned Markham natives who were nervous about patrols crossing the Markham because they feared reprisals by the large numbers of Japanese there who, they said, were being reinforced by submarine. The natives pleaded that patrols should not cross the Markham, and promised to obtain information themselves. They reported also that the Japanese, by means of radio location, had discovered that Captain Howlett25 and Warrant-Officer Ryan,26 both of Angau, were moving in the Urawa area. Kyngdon asked that they be requested to keep wireless silence.

Preparing for more distant events General Herring on 8th June had warned General Clowes in Port Moresby and General Savige that the 57th/60th Battalion was on 24 hours’ notice to move by air from Port Moresby to the Watut Valley with the task of defending the Marilinan airfield; it would come under Savige’s command on arrival.

By 20th June two platoons from the 57th/60th were patrolling in the Marilinan area. On 18th and 19th June the commander of the 57th/60th, Lieut-Colonel Marston,27 was informed that his task was to prevent the Japanese from entering the Watut Valley sufficiently far to interfere with or hamper the operation of aircraft on airfields selected in the valley between Marilinan and Wuruf. This task would be done by an infantry platoon and a platoon from the Papuan Infantry Battalion based on Pesen, with reconnaissance patrols to the north and standing patrols to the North-east and North-west. The main defensive position of two companies would be constructed in the Wuruf area while the Marilinan airfield would be protected by two companies and American anti-aircraft guns.

How to supply his augmented force was one Savige’s major problems. The air force did its best, but bad weather caused delays and throughout June the troops often went hungry or were down to their last meal.

Inaccurate dropping of supplies and lack of carriers also helped to keep the cupboard bare. An example of this combination of circumstances had occurred on 10th June when, after some days of adverse weather in the 15th Brigade’s area, the aircraft approached the steep-sided Selebob Ridge (the dropping ground) at right angles instead of making their run as requested along the ridge; they also dropped too high and too fast. This necessitated the commandeering of a boy-line of 90 leaving Powerhouse on 11th June for rations. Such was the shortage in this area that Lieut-Colonel Refshauge,28 commander of the 15th Field Ambulance, considered that fighting troops would be unable to maintain their strength. The 11th of June was an exasperating day also for the troops at Guadagasal: to the insult of bad supply dropping by four Douglas aircraft bringing supplies was added the injury of mistaken strafing by the Beaufighters. One transport emptied nearly all its packages in heavy timber off the clearing and another continued to throw out packages after passing the clearing.

In mid-June General Herring decided to see something of the forward area and to hold a final coordinating conference there. On 13th June he flew to Bulolo accompanied by the Deputy Chief of the General Staff, Major-General F. H. Berryman. That day Savige signalled Brigadier Moten to be at Summit at midday on 15th June. Herring, Savige and Berryman, accompanied by Colonels Wilton, Griffin, Sweany and Archibald R. MacKechnie (the commander of the landing force), jeeped to Summit on the 15th. After assembling in a large tent specially erected for the conference Savige called on Moten, who would actually control the ground operations, to explain his plan for covering the landing at Nassau Bay and the capture of Mubo.

While the three senior commanders sat on one side, Moten explained his plan to this distinguished audience. He said that he thought that the enemy in the Mubo–Komiatum area was approximately 1,100, comprising the I and II Battalions of the 102nd Regiment; and in the Duali–Nassau Bay area there were about 200. His appreciation of enemy dispositions had led him to believe that the Japanese were in strength along the line of Buigap Creek with forward positions at Observation Hill, Kitchen Creek, Green Hill and the Pimple. The Salamaua garrison, believed to be about 2,600 with a further 500 in the Bobdubi Ridge area, would have their hands full countering the attack of the 15th Brigade and be unable to reinforce the Mubo area, although it would be possible to bring reinforcements from outside by submarine and barge. His brigade’s object was to “clear the enemy from Mubo area and drive forward to Mount Tambu with a view to exploiting via tracks of access to Lokanu to the line of Francisco River”.

Moten envisaged the operation being carried out in five phases. In phase 1, MacKechnie’s battalion group (the I/162nd Battalion) would establish a beach-head at Nassau Bay where they would come under Moten’s command and would be assisted by a company of the 2/6th Battalion; after

clearing the enemy from Duali and the other villages of Nassau Bay, the Americans would push forward to the assembly area at Napier. In phase 2, the 2/6th plus a company of the 2/5th would capture Observation Hill and the ridge between Bui Savella and Kitchen Creeks and exploit along both these creeks to Buigap Creek and along the track through the Mubo Valley to the Archway; at the same time the Americans would capture Bitoi Ridge and exploit to Buigap Creek. Phase 3 would consist of the capture of Green Hill and the Pimple by the Americans and the 2/6th. With the object of exploiting towards Komiatum and Lokanu, the 2/5th in phase 4, would advance from Mubo through the 2/6th, occupy Mount Tambu, link up with the 15th Brigade at Komiatum, and patrol towards Lokanu. Phase 5 would consist of the capture of Lokanu and Boisi and the clearing of the enemy from south of the Francisco by troops yet to be allotted. Four days previously D-day had been advanced to 30th June.

When Moten had finished Herring said: “That seems all right, Moten.” Savige and Berryman agreed, and so did the Americans. There was then some general discussion to elucidate a few points, among which was a request by the Americans to have red lights on the flanks and a white light in the centre on the landing beach. Savige agreed to this with a smile. MacKechnie and Moten agreed that the officer commanding the beach party (Lieutenant Burke) would meet the landing force commander (MacKechnie) at the white light, and guides at each red light would lead the landing parties to where detachments from the 2/6th would be guarding the flanks 300 to 400 yards from each red light. The Allies agreed that Captain E. P. Hitchcock’s company of the seasoned Papuan Infantry Battalion, which had served in the Papuan campaign and which had arrived at Morobe on 7th June in a schooner, would delay its movement from Buso (which it had reached overland and by canoe on 15th June) until D-day in order to retain the element of surprise. After arriving at Nassau Bay it would be used by MacKechnie for mopping-up operations and right flank protection in the coastal area north of the south arm of the Bitoi, and later would move north along the coast. The Summit conference also decided that the time of the landing would be between 11 p.m. and midnight on the night before D-day.

Moten gave MacKechnie a copy of Burke’s report and also some notes about projected movements for the seven days from the day before D-day. These indicated that on 29th June Burke’s party would arrive, the bombing and strafing of Duali would begin, and two Australian platoons would demonstrate near the mouth of the south arm of the Bitoi so as to entice the Japanese inland. On 30th June Burke, with the latest information, would have guides ready to lead MacKechnie’s troops to Napier. The Americans would consolidate the beach-head next day, patrol forward and to the flanks, and use their artillery to engage suspected Japanese positions. On 2nd July the Americans would begin the move to Napier, improve the track for artillery, and finish the mopping up at Nassau Bay. After arriving at Napier Australian troops would be

withdrawn, leaving only guides. Three days after D-day the Americans would complete their move to Napier and would bring their artillery forward; on 4th July the artillery would register targets while the infantry established observation posts and prepared for a forward movement to Bitoi Ridge. In his notes Moten expressed the hope that the Americans would begin to move from Napier on to Bitoi Ridge five days after the landing.

Dexter on 14th June outlined the role of his men for D-day, when they were to create a diversion and draw the enemy inland from the position reached by Gibbons. He allotted portion of Urquhart’s platoon to Burke as a beach guiding party. One of the other platoons was given the task of establishing a base camp half way between Napier and the last spur, and drawing the enemy back from the coast. The third platoon was allotted the less exciting but no less vital task of carrying supplies forward from Napier for the remainder of the company. Later action would depend on the situation but the company would try to remain in contact with the enemy until a junction was established with the Americans. The troops were warned of the similarity of Japanese and American helmets.

The conferences at Port Moresby on 31st May and Summit on 15th June had discussed an offensive whose objectives were Nassau Bay, Mubo and Bobdubi Ridge. Nothing was said about the ultimate objective – the capture of Lae and the Markham Valley – nor of the vital fact that Salamaua must not fall before Lae. This was doubtless done for security reasons, but later misunderstandings might have been avoided had Savige been told of the bigger plan. He remained convinced that he should capture Salamaua as soon as possible. There appeared to him to be no ambiguity about his orders to drive the enemy north of the Francisco, and Salamaua was immediately north of the mouth of the Francisco. The position was all the more anomalous in that Moten knew of the bigger plan. General Blamey himself was not satisfied that New Guinea Force fully understood his intentions and on 15th June he wrote to Herring:

I note one divergence from the plan I had approved for future operations. You will remember that it had been decided that Salamaua should not be seized; it should be bypassed. ... This has been ignored and the outline of plan indicates that Salamaua would be first seized. If this is done of course all hope of obtaining any degree of surprise at Lae will disappear. Whereas any build up south of Salamaua will tend to draw forces into the latter area. I hope to go north again at the end of this week and will discuss the matter further with Berryman, but so far I do not see any valid reason for changing the plan already agreed upon.

Herring explained that a misunderstanding had occurred because New Guinea Force had been referring to the preliminary operation for the seizure of the Komiatum Ridge as the Salamaua operation. “It was never intended,” he wrote, “to depart from the plan you approved, nor should I think of doing so without your approval. ... We hope and intend to get guns forward to shell Salamaua but further than this we did not intend to go.”

One day before the Summit conference Wood had informed Moten that reports from patrols and listening posts led him to believe that the Japanese were in the area previously occupied by Tatterson’s company. Between 7th and 11th June they were more active than usual and were sending out small reconnaissance patrols towards the Australian position on Lababia Ridge and the Lababia OP.

Moten was anxious about persistent reports from Wells OP of Japanese moving south along the Komiatum Track and about Wood’s reports of increased enemy activity round Mubo. He could not be sure whether a large-scale attack was intended round Mubo or whether the Japanese were reinforcing their defensive positions fearing an Australian attack. It did not seem improbable to the Australians that the enemy might know of the planned landing, for even the native carriers knew something of it.

Preparations for D-day continued. Lieutenant Swift29 of the 2/1st Field Regiment had left Lababia on 13th June to look for suitable artillery positions and to find out whether guns could be moved inland from the coast. On the 15th Lieutenant Johnson and Sergeant Gibson again left Napier for Bitoi Ridge reconnoitring the route to be taken by the Americans. They returned five days later and reported that the journey from the river junction to the top of Bitoi Ridge would take a few lightly-equipped troops about eight hours and a larger number approximately ten. By the time of the Summit conference Sergeant Daniel had supervised the construction of 16 large huts for the incoming Americans. Across the Bitoi Sergeant Sachs30 from Reeve’s OP31 found a route for troop movement to Observation Hill without meeting any signs of Japanese beyond blood spots and fresh excreta on Observation Hill. Tracks were cut from Reeve’s OP to Buiapal Creek and assembly areas were prepared north of the creek at the foot of Observation Hill. As with the patrols to Bitoi Ridge, these patrols were carried out without exciting the enemy’s suspicion. The series of two-man listening posts and daily reconnaissance patrols north of Lababia Ridge had located Japanese positions where little security was being observed. On the night of 16th June Private McGrath32 and Private Hurn33 volunteered to raid the position. They moved stealthily along the Jap Track, no mean task at night, and had a pleasant evening’s sport when they located about a dozen Japanese squatting round a camp fire without a sentry. Each Australian fired 20 shots at the silhouetted targets causing many screams; a delay of two minutes ensued before the Japanese reached their weapon-pits and started firing wildly in all directions.

In the next few days patrols from the 2/6th Battalion’s forward companies on Lababia Ridge and Mat Mat kept close watch on the Pimple

and Observation Hill areas respectively. The mountain battery periodically fired on the Bitoi crossing and air strikes on the Stony Creek and Kitchen Creek areas were made on 18th June. On the previous day four enemy aircraft had bombed Wood’s headquarters at the Saddle, obviously attempting to silence the mountain gun about 400 yards away. Skirmishes between small Australian patrols and Japanese listening posts or standing patrols occurred near the Jap Track. Normally the Japanese had been content to sit in their defences and let the Australians control no-man’s land, but now they were unusually active.

Information about enemy movement poured in from Wells OP. On the 15th 486 Japanese were counted moving south along the Komiatum Track. At 6 a.m. on the 16th Wells OP reported that three heavily laden launches had arrived at Salamaua from Lae the previous evening; at midday that 80 Japanese were seen moving south along the Komiatum Track. Between 3 and 5 p.m. the men at the observation post saw 173 Japanese and 60 heavily laden carriers moving south towards Komatium and 58 Japanese moving north towards Salamaua.34

Thus Savige and Moten felt fairly certain by 20th June that the Japanese intended to strike hard at the forward Australian positions in the Mubo area. From 10.20 a.m. that day Japanese aircraft dive-bombed and pattern-bombed Guadagasal, Mat Mat and the Mubo Valley. In the day 83 enemy aircraft were overhead. The bombing caused some casualties and damage, particularly to the 2/6th’s “Q” store at the Saddle but the most serious outcome was the dispersal of the brigade’s native carriers. They went bush, and by 4.30 p.m. next day only three had returned and about 578 were missing. It took three days for Angau to gather them together, and this caused a commensurate delay in moving forward rations, stores and ammunition.35 With D-day 10 days away this time could ill be spared. Angau officers who were rounding them up – Major N. Penglase and Lieutenant Watson – said that more Japanese air attacks in the near future would make it impossible to hold the carrier lines; in consequence, Moten suggested that frequent fighter sorties be made over the forward areas.

Dexter’s company at this grave moment was divided between the Laba-bia camp, Napier, and the Lababia OP. Lieutenant Roach’s36 platoon and Sergeant Hedderman’s were slightly forward on the left and right respectively of the Jap Track, just north of its junction with the Lababia Track. Their rear near the track junction was guarded by Lieutenant Exton’s37 platoon from another company. West of these three platoons across a small saddle Dexter established his headquarters guarded to the north by

Defence of Lababia Ridge, 20th–23rd June

Lieutenant Smith’s38 anti-tank platoon working as riflemen. Lieutenant Urquhart’s platoon was at Napier. Five men from the battalion Intelligence section and the forward company were at Lababia OP. About 200 yards north of Roach’s platoon an entrenched section listening post was manned night and day.

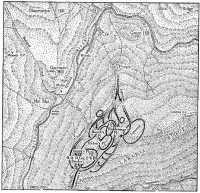

At 1 p.m. on 20th June a patrol led by Private Watt39 moving north along the Jap Track about 50 yards forward of the listening post noticed a few Japanese moving up the track towards the listening post. After firing on them and killing the leader, who was giving hand signals to those in the rear, the patrol withdrew under fire. Soon afterwards the Japanese began firing indiscriminately from both sides of the track. The Jap Track at this point was very steep with re-entrants on either flank. Corporal

A. J. Smith,40 commanding this forward section, was reinforced and although the Japanese made several attempts during the afternoon to get round to the section’s flanks they were at a disadvantage for they were on lower ground. Enemy pressure continued, however, with the result that Smith was withdrawn to the forward platoon position. Private Watt ran forward and, with machine-gun fire, covered Smith’s withdrawal. After inflicting heavy casualties Watt saw six Japanese in dead ground on the flank and killed them with two grenades. In the withdrawal he re-set four booby-traps. At 4.30 p.m. the Japanese withdrew and half an hour later all was quiet. No movement was seen or heard during the night. Learning that about 50 Japanese had been engaged, Dexter concluded that they were probably a strong patrol sent out to find the main Australian positions before launching a large-scale attack. The Japanese had moved up the track in a very open way and had appeared surprised to stumble across the outpost; according to Corporal Smith the Japanese leader had smiled at him. They were well camouflaged, wearing greenish uniforms with packs on their backs to which were strapped boughs and green foliage. During the afternoon when they were held up they had made a great deal of noise and had held many consultations. Whistles blown before the firing of automatic weapons had helped to indicate Japanese positions to the defenders and to facilitate the killing of 9 and wounding of 11 while only one Australian was wounded.

Next morning at 6.30 a small Australian patrol moved 500 yards up the track to the Lababia OP and found all quiet. An hour later the telephone line to the observation post cut out. A patrol accompanied by linesmen had barely left the company perimeter when firing broke out from enemy positions north of the observation post track. This continued intermittently throughout the morning during which time the Japanese were apparently moving to the flanks in small groups of two and three and assembling for an attack. This movement was harassed by the defenders’ fire which scattered several small groups, and by booby-traps. At 11 a.m. a large body of Japanese, advancing on either side of the Jap Track, was dispersed by fire from the grenade discharger, Brens, rifles and Tommy-guns. Both the grenade with a 7-seconds fuse fired from a discharger attached to the muzzle of the .303 rifle and the grenade with a 4-seconds fuse thrown by hand were supporting Savige’s contention that units experienced in jungle warfare were unanimous in their praise of the grenade as the Number 1 jungle weapon. In the morning Corporal Smith set out with a patrol to hunt the enemy. Coming upon 25 Japanese he hit five before his rifle was shot from his hands. Grasping the rifle of a wounded comrade he kept the Japanese at bay until he was able to pick up the wounded man and carry him back. Up to 2 p.m. probably 25 Japanese were hit by small arms fire from Roach’s and Hedderman’s platoons, exclusive of those killed by the supporting weapons, and the booby-traps which were continually being sprung.

Sensing that a dangerous situation was about to develop, Moten at 1.17 p.m. sent a message to Wood who had left his headquarters at the Saddle to visit Mat Mat: “POSTERN prejudiced by enemy occupation of Lababia Ridge. Take immediate aggressive action to drive enemy back to former location in Pimple area.” In order to reinforce Dexter’s company, Moten, eight minutes later, ordered Lieut-Colonel T. M. Conroy of the 2/5th Battalion to send part of one company from Banana to the Saddle to relieve Captain Cameron’s41 company of the 2/6th which would then move to Lababia Ridge.

An hour earlier Lieutenant Smith’s platoon reported slight movement well round on the left flank but forward of his position covering the Lababia-Saddle track. At 2 p.m., however, the Japanese began a heavy attack on Hedderman’s position between the Jap Track and the Lababia OP Track. The attack quickly spread to Roach’s and Exton’s front. Pouring automatic and mortar fire into the two forward platoons the Japanese pressed harder and harder. A bayonet attack along the Jap Track was halted within 10 yards of the forward Australian position; another one on the right flank brought some of the Japanese to within

20 yards of the Australian positions before they were stopped. During the attack Hedderman and his runner, Private G. L. Smith,42 found time to carry two badly wounded men to comparative safety where Captain Scott-Young43 attended to them. At 3 p.m. Hedderman’s left flank was endangered by a determined enemy assault supported by mortar fire. Moving to the threatened spot he silenced the mortar and dispersed the enemy attack by using the grenade discharger. Private Smith meanwhile was distributing ammunition to the weapon-pits and joining in the fight where it was hottest. Desperate attacks were then launched against Roach’s troops, who fought back with fierce determination although it seemed that so few men could not hold back the large enemy force much longer. When all but three of his section had been killed or wounded Private Ryan44 took command and coolly held off the attack with Bren-gun fire. When another machine-gunner was hit Private McGrath picked up his gun, ran to another pit where all the occupants were casualties, and drove off the attackers.

With the enemy massing for another assault Dexter decided to use part of his small reserve – a few men from his company headquarters – to reinforce Roach’s platoon. The reinforcements arrived just as Corporal A. J. Smith and his remaining riflemen, with fixed bayonets, were meeting a Japanese bayonet attack up the Jap Track. The determination and courage of Corporal Smith’s gallant band were too much for the attackers, who wilted. Every Japanese in this attack was killed by the bayonets of these men or by fire from the weapon-pits.

The edge of the Japanese attack had now been blunted; it received a large dent when, at 3.15 p.m., Sergeant Mann45 used the 3-inch mortar for the first time, from a clearing near company headquarters. The second bomb caught in a small branch and exploded. The head native climbed up the tree and cut down the limb although bullets were flying through the trees. Firing throughout the remainder of the afternoon on the Jap and Lababia OP Tracks the mortar caused the Japanese to break on several occasions. One of Dexter’s main concerns was to conserve his ammunition. Whenever he heard any prolonged bursts from the defenders he was forced to warn his platoon commanders to “keep your bloody fingers off the triggers”.46 The problem of supplying ammunition to the weapon-pits of the perimeter was solved by the troops with typical ingenuity. They took off their socks, put the ammunition in them, and threw them to the various weapon-pits.

The Japanese continued to attack Roach’s, Hedderman’s and Exton’s positions throughout the late afternoon, and, although suffering heavy casualties, it seemed that they might break through Exton’s position where their shouting and determined attacks appeared to unnerve one post. Exton and Corporal Martin47 ran forward and rallied the men, who, encouraged by their example, waited until the enemy were within 30 yards before firing. It was with some relief that Dexter welcomed Cameron and his company who arrived at Lababia Ridge between 5.15 and 6.15 p.m. along the Lababia-Saddle track which the enemy had not reached. Cameron’s men dropped their packs at company headquarters and were sent forward immediately to reinforce Roach and Exton.

Towards dusk the Japanese attack gradually decreased in intensity. Throughout a night of sleepless expectancy the Australians could hear sounds of the Japanese moving dead and wounded, the eerie howling of a dog, and much moaning and groaning. These melancholy cries of the wounded contrasted with the arrogant calls of the Japanese at the height of the fight: “We are Japan; we will win,” or “Come and fight you conscript bastards.” The Japanese attackers had lost about 100 men killed and wounded during the day while Australian casualties amounted to 9 killed and 9 wounded.

Desultory fire from both sides began about 6.30 a.m. on 22nd June. From 8 a.m. onwards small parties of Japanese were observed moving round to the Australian left flank and, Dexter feared, to the Lababia-Saddle track. These parties were effectively sniped; while the grenade dischargers and 3-inch mortar, always great morale builders or morale lesseners depending on which end of them the troops happened to be, continued to have great effect down the Jap Track judging from the squeals and sounds of stampeding. Movement during the morning was

confined to the Australians’ left flank and the right flank beyond the Lababia OP Track, where Australian sniping was most effective. Here the Japanese were climbing trees and firing down into the Australian weapon-pits, but they reckoned without Exton, a crack shot. Dexter was telephoning Exton’s platoon sergeant, who said suddenly: “Just a minute – there’s a Nip getting up a tree about 100 yards away – Exton’s going to have a shot – he’s got him and he’s bouncing.”

At 2.10 p.m. heavy fire poured this time into Lieutenant R. J. H. Smith’s position just north of the Lababia-Saddle track. Fire from the Australian defenders, however, again proved too powerful and after five minutes the attack died out. Five minutes later a Japanese mountain gun began shelling embattled Lababia. At first the shells landed to the west but soon started to arrive within the company perimeter. One severed the line to battalion headquarters, but it took the hard-pressed signallers only half an hour to fix it.

That afternoon two patrols tried to find the whereabouts of the Japanese attackers. One moved east from the Lababia camp to the south of the Lababia OP Track but was forced to withdraw after running into the enemy before reaching the track. Another patrol, led by Lieutenant W. T. Smith48 from the 2/5th Battalion left the Saddle to try to make contact with the enemy west of Dexter’s position and north of the track from Lababia Ridge to the Saddle. It reached the track leading to Vickers Ridge but was unable to find any enemy. Japanese casualties for 22nd June were thought to be between 50 and 60, excluding those killed by supporting weapons. One Australian died of wounds and 3 others were wounded making a two-day total of 10 killed and 12 wounded, mostly caused by light mortar fire or tree snipers. During the night the weary Australians heard the Japanese again moving their dead and wounded.

The Japanese attacks seemed to the defenders to have been in three phases. In the first, the Japanese moved up the track until fired on, when they deployed to either flank and pressed on. In the next phase they concentrated for the attack on the right flank which was probably carried out by moving a force of from 50 to 60 up to the vicinity of the track to Lababia OP during the early hours of 21st June and building up this force by the movement of groups of three or four from the Pimple. Later investigation showed signs of much movement and occupation on both sides of the observation post track by approximately 200-300 troops. The third phase was the attempted encirclement on the left flank which was carried out in the same manner as on the right flank but without a force in position before small groups began to move. To reach their positions on the left flank the Japanese cut a new track from the Jap Track to meet the Vickers Ridge Track. A feature of the attack which amazed the defenders was that the Japanese never closed their enemy’s line of communication – the Lababia-Saddle track – although they encircled the perimeter to within 50 yards on the north side. Because of this failure reinforcements went forward without interference and supplies were kept

up. The Japanese failure to cut the track to the Saddle was all the more remarkable because of the presence of a track leading from the position formerly occupied by Tatterson’s company to the Lababia-Saddle track.

After a miserable night with heavy rain a series of booby-trap explosions were heard at first light on 23rd June. The few available men, from the company commander to the company clerk, manned the perimeter but no attack developed. Soon afterwards ineffective firing along the Jap Track came from the enemy’s positions. As on the previous day this firing seemed designed to draw the Australian fire and so to enable the tree snipers to operate: on both days four or five tree snipers had been shot from the trees soon after first light. Automatic fire continued from the Jap Track until 9 a.m. by which time the 3-inch mortar was proving effective in breaking up enemy movement. Between 9.45 and 11 a.m. the mountain guns joined in the punishment and shelled the Jap Track and Pimple area north of Lababia with great effect. Major O’Hare had used two 3.7-inch howitzers throughout the fight and at this stage was OPO (observation post officer) himself, but shortage of ammunition had reduced firing to times when the Japanese were actually attacking. The mountain guns with their 21-lb shells and extreme accuracy were more decisive than the 3-inch mortar which could not shoot close to the perimeter. The screams of the bombarded Japanese and the excellent shooting caused the 2/6th Battalion war diarist to exult, “the morale of our troops which has always been high was raised to the highest pitch by the excellent shooting of the mountain battery”. At midday when the intermittent Japanese fire from the front and the right and left flanks suddenly increased in volume the 3-inch mortar again caused the Japanese to disperse. Wood now rang Dexter and said: “I’ve got a surprise packet for you. Stop the arty.” Soon afterwards the delighted troops watched Beaufighters spread their “whispering death” up and down the Jap Track. By 1.30 p.m. the enemy had withdrawn and firing had ceased.

While the enemy was receiving his final coup de grace Lieutenant W. T. Smith’s patrol moved up the Lababia Track to the observation post which he reached at 2.45 p.m. without sighting the enemy, although the telephone wire was cut in many places. Smith’s platoon relieved a seven-man patrol which Moten had ordered Urquhart to lead to the observation post during the Lababia attack. Urquhart had left Napier at 7 p.m. on 22nd June in total darkness, climbed 2,500 feet up the steep track and arrived at 2 o’clock in the morning. After their relief Urquhart’s men returned to Napier.

Documents containing Japanese plans for the attack were found on a dead Japanese who had died with his hand in the air as though in salutation to his victors, who returned his grisly greeting and waved to him.

With the Japanese mortaring Mat Mat in the late afternoon of 23rd June Dexter’s force for the first time in four days had a respite from fighting. While Corporal A. J. Smith re-occupied the listening post, other troops reconnoitred the battle area and found many Japanese dead. Their own comrades buried the Australian dead on Lababia Ridge after a moving

service conducted by Padre O’Keefe.49 The enemy dead were buried by the Pioneer platoon which Wood sent forward for that task. Soon after darkness had fallen an enemy 75-mm gun opened fire on Guadagasal50 and Mat Mat. This was the first time during the Japanese attack that the gun had fired. The shelling ceased at 7 p.m. by which time the attack had been defeated.

Congratulatory messages were received by Wood from Herring and other senior commanders. To Herring, Savige and Moten the defeat of the enemy meant that subsequent re-grouping and concentration of units for the offensive could proceed unhindered; it also meant that for the first time in the bitter nerve-racking fighting since April the Australians had scored a notable success. The action underlined a development in Australian defensive tactics. Previously the teaching had been to camouflage defensive positions and conceal the defenders. The Lababia defences, however, had been based – first by the 2/7th and then by the 2/6th – on positions which to some extent sacrificed concealment to the clearing of fields of fire. Approached from the enemy side, however, there was little to be seen for the enemy had to come up hill and could see nothing until he was on a level with the diggings, and the fire lanes were cleared from the ground up, only leaves, twigs and small shrubs being removed to a height of about four feet.

“This engagement is noteworthy,” wrote Moten, “and is a classic example of how well-dug-in determined troops can resist heavy attacks from a numerically superior enemy. Our troops in Lababia Base totalled 80 and when joined by C Coy 2/6 Aust Inf Bn totalled 150. It is conservatively estimated that 750 Japs attacked our perimeter. Our casualties were 11 killed and 12 wounded. Enemy casualties were estimated as 200.”

The Australian estimate of the Japanese strength was too low – more than 1,500 not 750 took part in the attack. The estimate of enemy losses was a little high but not very: the Japanese recorded that 41 were killed and 131 wounded.

Documents captured at Lababia Ridge identified the 66th Infantry Regiment (less III Battalion) under Colonel Araki. The I Battalion was 687 strong, the II was 552. The 66th Regiment had been shipped from Rabaul to Finschhafen and had marched down the coastal track to Lae, leaving Finschhafen on 13th April. General Adachi said after the war that the Japanese forces engaged were about 1,500 strong. The two battalions engaged had recently relieved I and II Battalions of the 102nd Regiment which had been in the area during May. Including technical troops there were about 2,000 Japanese in the Mubo area.

On 23rd May General Nakano, the commander of the 51st Division, had been confident of his ability to clear the Lababia–Guadagasal–Waipali area. He had directed that ammunition and rations be accumulated at Mubo between 25th May and 20th June ready for the attack on Waipali which should be successfully completed by 22nd June. Preparations for the attack had included the repairing of the main track for about 5,500 yards north and 2,500 yards south of Komiatum.

Following Nakano’s instructions, Araki, on 27th May, had issued an order that the 66th Regiment would carry out a surprise attack on the Australians’ “key point” at Lababia and annihilate them. “Immediately after this,” continued the