Chapter 4: Rendezvous at Nassau Bay

BECAUSE of the successful Australian resistance on Lababia Ridge, planning for the offensive was not hampered. As mentioned, it was to take place in three phases: first an American battalion group would establish a bridgehead round Nassau Bay on the night 29th–30th June; second, a battalion of the 15th Brigade would capture Bobdubi Ridge while small forces would raid the Malolo and Kela Hill area to distract attention from the attack at Bobdubi; third, a battalion of the 17th Brigade and the American battalion group would attack Mubo, not later than 6th July.1

The American battalion chosen to carry out the first phase was the I/162nd Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Harold Taylor), one of three comprising Colonel MacKechnie’s 162nd Regiment. This would be the 162nd’s first action. It had landed at Port Moresby from Rockhampton in February 1943 and later relieved the 163rd in the Buna–Sanananda area. At the end of February it began leapfrogging up the coast using mainly surfboats and trawlers, and looking for any Japanese who had survived the Buna fighting. By 4th April Taylor had established a defensive position at Morobe. Soon afterwards the I/162nd Battalion was relieved by the III/162nd and moved south to the Waria River for intensive training. To help the Americans in their baptism of fire Captain Hitch-cock’s company of the Papuan Infantry Battalion was attached to MacKechnie Force, which included detachments of artillery, signals, etc.

On 9th June Captain D. A. McBride, liaison officer from the 17th Brigade, arrived at MacKechnie’s headquarters. He was informed that planning was in abeyance pending advice about the availability of landing craft and a unit known then as the 2nd Engineer Amphibian Brigade whose task would be to handle all transport between Morobe and the beach-head.2

The 2nd Engineer Special Brigade was born on the sandy shore of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on 20 June 1942. ... Everything was “secret”. Announcement of the event was proclaimed only by the roar of motors and the sight of queer looking landing craft splashing through the choppy waters of Nantucket Sound. ... Although training of the new unit was veiled in secrecy, it was not long before the local residents of that picturesque cape showed keen interest in the “boys with the boats”. ... Gradually they began to refer to the new Amphibians as “Cape Cod Commandos”. ... The name stuck. It followed them across the United States and the Pacific Ocean to Australia, New Guinea, New Britain and the Philippines.3

The “Amphibs”, as they were known, were specially selected from men with maritime or other relevant experience. Eventually three brigades of “Amphibs”, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Engineer Special Brigades, served in the Pacific. The establishment of a brigade was 360 officers, 7,000 men and 550 landing craft; each brigade included three Boat and Shore Regiments.

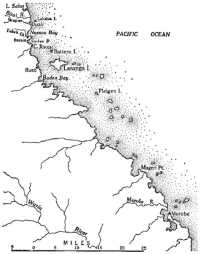

The training of the I/162nd Battalion had included the loading of 70 men on each of three patrol torpedo boats and their transfer at sea into LCVs (Landing Craft, Vehicle). Morobe Harbour, a deep land-locked bay protected to seaward by several high coconut-covered islands and surrounded from shore to foothills by mangrove, provided an excellent base. It was regularly bombed by the enemy, but good hideouts were available near by for PT boats, trawlers and barges. North of Morobe the coast was indented with large bays, while heavily timbered mountain spurs extending to the sea precluded the possibility of any land advance along the coast and dictated that all movement must be by water. Even the natives in this area were canoe-borne.

After the Summit conference MacKechnie had decided on 16th June to change the staging base for the landing from Lasanga Island to Mageri Point, an excellent sandy beach 12 miles north of Morobe with good cover for troops and ample hideouts for landing craft among the mangrove-lined inlets.

Uncertainty about the number of landing craft that would be available caused great difficulty. MacKechnie originally believed that 35 LCVs, 3 LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanised) and 9 salvaged Japanese barges would be available. Four days before the landing, however, he was informed that there were available only 20 LCVs, 1 LCM and 3 Japanese barges, together with 3 PT boats to pilot the landing waves and carry 70 men each. With these craft MacKechnie carried out a practice landing on 27th June at Mageri Point. The exercise was not a success but valuable lessons were learnt by the infantry and the amphibious engineers.

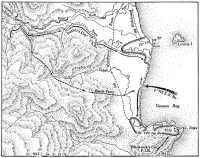

The Papuan company reached Buso by 15th June.4 Although they were not to move north from Buso for the present this did not prevent the native soldiers from carrying out long-range patrols, at which they were adept. For example, Lance-Corporal Tapioli went overland to Tabali Creek, and Lance-Corporal Bengari joined an enemy carrier line and spent two nights and a day with the enemy at Nassau Bay. Hitchcock himself, with several of his NCOs, reconnoitred the track from Buso to Cape Dinga – the southern headland of Nassau Bay – and decided that he could safely conceal his company behind Cape Roon on the day before the landing.

Brigadier Moten informed Colonel Wood on 21st June that Lieutenant Burke would arrive at the Saddle next day and would be supplied with direct communication to brigade headquarters until the completion of his task of assisting the American landing. Much depended on Burke. He had four tasks. The first was to guide the Americans to the landing beach with two red lights 600 yards from one another with a white light in the centre; the second was to protect the flanks of the beachhead with a platoon until relieved by American troops; the third was to provide guides to lead the Americans to Napier; and the fourth to inform the Americans where enemy resistance might be met and of the whereabouts of Major Dexter’s company. Moten also instructed Burke to depart from Napier three days before D-day; ordered that “boats, collapsible” for crossing Tabali Creek would be carried; that there would be no premature reconnaissance forward to the beach in order that the enemy should not be warned of the landing; and that six runners would be used for communications between the beach and Napier.

On 22nd June, while the fight for Lababia Ridge was still raging, Dexter received further detailed instructions from Moten about his company’s role. The company could anticipate no respite until it had drawn the enemy inland to the last spur and had been relieved by the Americans on their way to Napier where tracks had been cut to newly-built bridges over the Bitoi and on to Bitoi Ridge. On the day after the landing a small detachment from Napier would climb Bitoi Ridge to select a vantage point from which the Japanese lines of communication to Komiatum could be overlooked. Dexter’s company, plus an additional platoon, marched from Lababia Ridge to Napier on 25th June. Left at Lababia was Captain Cameron’s company reinforced by a platoon from each of two others. On 24th June Moten’s headquarters closed at Skindewai and opened at Guadagasal.

At this time the supply problem was again causing concern. Too much weather and too few aircraft often meant that the troops felt the pinch. Even one inaccurate drop could endanger the build-up of supplies and so threaten to disrupt the plan for the offensive. For example, at

Guadagasal on 27th June Mitchells came in too fast and flew across the dropping ground instead of along it; only 6 of about 40 parachutes landed on the dropping ground. One aircraft dropped supplies on Buisaval Ridge, some 4,000 yards South-east of the dropping ground, and many packages were lost in inaccessible gorges. Moten’s vigorous protest that a continuation of such dropping would have a ruinous effect on maintenance for the coming operations was immediately passed on to General Herring. The supply position worsened, particularly in the 15th Brigade’s area. By 27th June there were no rations for natives in the whole Missim area, and troops and natives round Hote were without food. This unfortunate situation was not likely to improve the spirits or stamina of troops who were to go into action three days hence, most of them for the first time. Complaints and entreaties brought their reward, and on 27th June 13 aircraft dropped rations and ammunition, 12 at Selebob and one at Hote; and a further 20 dropped supplies on 28th June.

It was natural for troops in the forward areas to believe that the irregularity and scarcity of rations were caused by New Guinea Force’s lack of interest. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Herring and his staff knew only too well that the fate of the offensive depended on their ability to get supplies forward by air to the right place at the right time. The problem of supplying the Salamaua battle area was no easy one. All supplies had to be flown from Port Moresby. The mountains themselves were a serious enough obstacle for transport aircraft, but when the clouds built up over the mountains flying was impossible. Another hazard for the Allied supply dropping planes was the presence of Japanese fighters only a short distance away at Lae, while the nearest Allied fighters were at Dobodura some 200 miles away. To overcome this difficulty the Fifth Air Force adopted the practice of using bombers to carry supplies. The high speed of the bombers over the targets led to bad dropping, but bad dropping was better than none at all. Another important factor was later described by Herring: “The dropping had to take place in the shadow of high mountains and not only is it bad for aircraft to run into high mountains but there are a large number of air currents about which make flying in the vicinity somewhat hazardous and raw pilots found it very difficult at first to avoid these and get their runs over the dropping places just right.”

On 22nd June Colonel Guinn,5 now in temporary command of the 15th Brigade, issued the brigade’s first operation order which had been drawn up by Brigadier Hosking. The 58th/59th Battalion received the premier role of capturing Bobdubi Ridge from Orodubi to the Coconuts on the north end of the ridge – a very onerous task. Other tasks included

raids by the 2/3rd Independent Company on Malolo and Kela and the establishment of ambush positions by the company of the 24th Battalion forward of Hote.

On 23rd June Colonels Guinn and Starr and Major Travers arrived at Missim and later left with Major Warfe for the Meares’ Creek area. Next day they arrived at Nunn’s Post6 where Warfe, from his detailed and intimate knowledge of the wild country, oriented the other two commanders. As a result of this reconnaissance Guinn decided that Old Vickers and Gwaibolom (the highest feature on the ridge) were the keys to Bobdubi Ridge. He therefore instructed Starr that these two places would be his objectives, and ordered Warfe to send patrols to investigate Gwai-bolom and Orodubi.

The bulk of the 2/3rd Independent Company had been resting during early June in the Missim area. Canteens and the YMCA and even the Salvation Army were still unknown in this part of New Guinea. Missim was not equipped for large concentrations of troops and huts had to be hastily erected to accommodate them. Books and other means of recreation were lacking but two luxuries were available: the men could bathe in the swirling pools of the Francisco and wash at the hot springs. Most important of all, however, was the opportunity to relax after months of tension.

To prevent the enemy from discovering his lines of approach to Good-view Junction (Stephens’ and Walpole’s Tracks) against which danger he had been warned by Warfe, Captain Hancock decided not to strike again in that direction but to coordinate any further strike with the coming offensive. His decision was also influenced by a message from the surprisingly erudite Warfe, who had no wireless time left in which to encode a message after Private Hemphill’s7 arrival with information about the miscarrying of Captain Hancock’s prisoner raid but who wished to inform his second-in-command of the arrival of the 58th/59th: “Major opus multi populi iam Missim sunt.”8 Other activities of the Independent Company included two successful patrols led by Lieutenant Erskine and Sergeant Tomkins to reconnoitre the routes south from Base 4 to the 17th Brigade area and thus to prepare the way for the move north by the 17th Brigade.

In the Markham area a patrol led by Lieutenant Baber9 (of the 24th Battalion) was surprised by the Japanese on 19th June near Markham Point. As a result of this action Corporal Giblett10 was officially posted as

missing and became the 24th Battalion’s first loss in action. The first news of further casualties in the Markham area filtered in on 22nd June when the police boy of Captain Howlett and Warrant-Officer Ryan (of Angau) reached Kirkland’s Dump and reported that the Japanese had attacked the party at the Chivasing crossing. At dusk Ryan arrived at Kirkland’s with the news that Howlett had been killed the previous day. Ryan in his report told of a hazardous long-range patrol he had conducted with Howlett in areas to the north of the Markham which they had crossed on 25th April. He told of reconnaissances carried out in the Japanese-infested area north of the river, of close misses with the Japanese, of sicknesses, of Japanese movements (including two patrols which left Boana for Kaiapit on 18th April and 30th May) and of new tracks. On 21st June Howlett and Ryan and one native, on being assured by the local natives that there were no Japanese in the area, entered Chivasing before re-crossing the Markham. As the three men entered the centre of the village a volley of rifle shots and a burst of machine-gun fire came from a row of huts. As Ryan jumped down into a creek Howlett was shot dead.

The Japanese who had ambushed Howlett and Ryan consisted of 10 military police who had left Lae on 10th June “to ascertain the condition of the enemy and to conciliate natives in the coastal region of the Markham River”. On 21st June, according to the leader’s report which was subsequently captured, the Japanese attacked “an enemy reconnaissance patrol which had broken into the village of Chivasing”, killed one of the two Australians, and captured some ammunition and equipment. “This enemy reconnaissance patrol,” reported the Japanese, “had crossed the Markham River from the direction of Marilinan. They had been sent to relieve a reconnaissance patrol which had been detailed to Finschhafen.”

Ryan blamed the Markham natives for the betrayal and stated that as the Japanese patrol had been waiting at least three weeks for the patrol’s return the natives of Chivasing, had they so desired, could have warned Howlett. “Instead they chose to assist the Japanese in every possible way and for that reason, in my own mind, I look upon Captain Howlett not as a battle casualty but as the victim of a cold-blooded murder by these treacherous Markham natives,” wrote Ryan.

Such behaviour contrasted strangely with the treatment accorded Sergeant Hogan’s patrol by the Gabmatzung people, who also belonged to the Markham tribes. The Australian soldier had a considerable understanding of and sympathy for the natives in spite of derogatory opinions about his handling of them by those considered more expert in native affairs. He had come to the conclusion that natives in enemy territory should not be blamed too harshly for helping the enemy. Living very close to the bare existence level the natives knew well that enemy depredations against their crops and livestock would reduce them to starvation. If the natives refused to carry or spy for the enemy their villages would be burnt, their food taken, and they themselves perhaps killed. Common sense dictated to the natives – logical and practical people – that it would be prudent to serve Japanese or Australians, whichever happened to control the areas in which they lived. Thus it became the exception for natives

to refuse to obey the enemy. Many fled from enemy territory and many others served the Japanese with their hands and the Australians with their hearts.

Angau capitalised on the natives’ genuine affection for the Australian soldier. News of good treatment, regular food and tobacco and care of the carriers’ families soon spread, with the result that principal Allied formations usually had numbers of carriers who had come from enemy-occupied territory. During the fluctuating fighting for Bobdubi Ridge the natives found themselves carrying for both sides in turn, usually for the Japanese first. The Australians, at least, did not blame or punish the natives for their actions. Some who were on Angau’s black list were undoubtedly pro-Japanese from choice; but on the whole they were amiable, likeable and cooperative and helped enormously to win the war in New Guinea.

Angau officers wished to punish the Chivasing natives and destroy their canoes. Savige decided, however, that the punitive expedition should consist only of an Angau representative and police boys, as an expedition by soldiers might turn the natives against the Australians. The Angau officer, moreover, was to sink the canoes but only address the natives. The Chivasing natives, pre-warned, or armed with the intuition which so often enabled a native to avoid trouble, did not wait to be harangued and left only three canoes.

On 26th June Savige informed Major Smith of the 24th Battalion that Captain J. A. Chalk’s company of the Papuan Infantry Battalion, less one platoon, would move forward from Wau to Sunshine where it would come under Smith’s command and patrol along the Markham. While the Papuans were moving up, a 3-inch mortar team from the 24th Battalion under Sergeant Christensen11 bombarded Markham Point on the 27th and again on 29th June. On the second occasion Lance-Corporal McInnes’ covering party inflicted 12 casualties on Japanese who came out to look for the troublesome mortar.

Final preparations were now being made for the landing of MacKechnie Force. It was the first time that so large a force would land in enemy-occupied territory in the South-West Pacific Area. By 28th June all troops were assembled at Mageri Point except for the 210 who were to travel on the three PT boats. From the reconnaissance of his own scouts and of Hitchcock’s Papuans MacKechnie believed that there were about 75 Japanese near the mouth of the south arm of the Bitoi, an outpost or two along the beach at Nassau Bay, and about 300 on Cape Dinga with an outpost on the ridge near the east end of the Cape Dinga peninsula. On the night of 28th–29th June three small detachments from the I/162nd Battalion were posted on Batteru, Lasanga and Fleigen Islands between Mageri Point and Nassau Bay. Their task was to flash signal lights each night from 29th June until 5th July to guide landing craft and supply boats. MacKechnie’s planning was again complicated

on 29th June itself when he learnt that he now had 28 LCVs, three LCMs, one salvaged Japanese barge, and four PT boats, three of which would carry troops and guide the barges. In these craft he decided to move three infantry companies, two artillery batteries, one anti-aircraft platoon, and five days’ rations during the two nights 29th–30th June and 30th June-1st July. Radio silence was imposed until midnight on 29th–30th June.

At dusk on 29th June three PT boats loaded 70 men each at Morobe and set off north to their rendezvous off Mageri Point with the main body of MacKechnie Force, about 770 strong, loaded into about 30 craft manned by boatmen of the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment.12 The landing force was divided into three waves each of which was to rendezvous with a PT boat outside Mageri Point. The boats moved off in twos with an interval of 20 minutes between waves. When they reached the open sea they encountered a heavy swell about 15 feet high, which added to the discomfort already caused by driving rain. So dark and stormy was the night that it was difficult for the boats to see the wakes of those in front of them, and more than half an hour was spent in finding lost boats. The first two waves met their PT boats but the third wave failed to do so and proceeded without a guide.

The other main groups of actors in the drama were also on the move on 29th June. The Papuans left Buso in canoes and arrived at Cape Roon whence they moved overland to Sachen Bay. Here Hitchcock set up his headquarters and during the dark night the native soldiers moved stealthily towards Cape Dinga.

Dexter’s company of the 2/6th Battalion, together with Burke’s small party, had arrived at Napier from Lababia late on the afternoon of 25th June. Next day the troops assembled in the largest hut where the company commander put them all in the picture. Towards evening Burke, with Urquhart’s platoon, left Napier on the first stage of their vital task. That night the patrol camped at the hut in a native garden along the Bitoi Track ready to push on next day.

At last light on the 27th Dexter marched east with the remainder of his company and camped at the hut. All movement was by night because the track along the Bitoi was exposed and a large force might have been noticed by enemy patrols. On the 28th the company was dug in at the last spur ready to withstand the Japanese whom it was planned to entice up the track, and ready to link up at this position with the vanguard of the Americans. At the same time a section led by Corporal McElgunn moved off as a guerilla force along the north side of the Bitoi’s south arm, hoping to capture the mortar used against Lieutenant Gibbons’ unfortunate patrol.

Nassau Bay landing, 29th–30th June

At 1.30 p.m. on the 29th Lieutenant R. J. H. Smith’s platoon moved out to try and draw back the Japanese from the position where Gibbons had been killed, about 400 yards from the coast. So far this part of the plan was working smoothly and when Private Trebilcock13 arrived from Burke to say that the beach patrol had reached Tabali Creek, Dexter was able to telephone this news to Moten. For about two hours in the late afternoon the men listened contentedly to sounds of an Allied air attack on Duali and Nassau Bay. At various times late at night and early next morning the Australians at the last spur could hear engines throbbing out to sea.

At first light on 28th June Burke had departed from the hut along the route which he and Ellen had blazed. The patrol spent the night in the jungle just off the track. Early on the 29th they moved off again and in the afternoon arrived at the edge of a swamp which was described feelingly by Urquhart as “the worst bastard I’d ever struck”. For two hours the men waded and staggered through the swamp, laboriously dragging out their feet, sinking now ankle deep, now up to their loins in the foul slime; dragging out their hindquarters by slapping weapons crosswise on the reeds and getting a purchase on them. After about 1,000 yards of

swamp the men reached firmer ground just after dusk and flung themselves down to rest near the dark and deep waters of the Tabali, which was said to be crocodile-infested. They hoped that the familiar jungle noises would drown the wheeze and whistle as they inflated their rubber boat. In pitch darkness Ellen and Private Molloy14 crossed the Tabali in the rubber dinghy which was then hauled back for the next load and so on. Before the last men were ferried across rain was pouring down. Burke, however, wished to reach the beach not more than one hour before the scheduled landing time because he believed that the actual site chosen for the landing might be occupied and it would be unwise to have a fight before the landing. Moreover, Moten had ordered no forward reconnaissance before the landing. He therefore paused for a short period despite Urquhart’s advice to press on.

At 9.45 the 26 men began moving towards the beach. It was soon apparent that they had under-estimated the difficulties of the night and jungle Linking themselves together by each man grasping the bayonet scabbard or shoulder strap of the man in front, they set out towards the beach which was only 500 yards away. Creepers, vines, trees, undergrowth and hidden logs impeded progress, and the patrol blundered too far south; in Burke’s opinion the considerable amount of metal carried by the troops caused a southing pull on the compass bearing worked out on the previous reconnaissance. “Try to imagine it,” wrote one participant soon afterwards, “only 500 yards between us and the sea, no more than the distance from Spencer Street to the Town Hall, from the Woolshed to Cassidy’s Creek, and we couldn’t do it. There we were ... a stumbling, straining, cursing serpent of men, lured on by the distant rumble of the ocean, and never getting any nearer to it. It became evident we were moving in a circle. We all stopped and listened – the croaking of frogs, the sullen drum-drum of the rain on our shoulders and always the rumble of invisible breakers.”15

Time was slipping away and it began to appear that the patrol could not reach the beach in time. The troubled moment produced the man. Corporal G. L. Smith went to the front and began hacking at the tangled jungle growth. At intervals he shone back a torch to guide the remainder of the patrol and was in turn guided left or right by Corporal Stephens16 holding a compass on a bearing of 90 degrees.

Progress was less frustrating as the men moved up to Smith before he advanced again. Burke realised that this procedure was risky but he knew there was no alternative if he was to reach the beach on time. As the men followed Smith and the flashlight the sound of the surf became stronger. After navigating a patch of thick jungle in this slow but sure manner the leading men about 11.15 p.m. reached a semi-cleared area whence they could hear the waves breaking on the beach. “Then of a sudden,” wrote Stephens, “Smithy gave a loud cry, the scrub relinquished

us and slipped quietly out of the game and, as we topped a low sand-dune, the ocean opened up with a million-horsepowered roar and swallowed us and the whole world in the noise of it.”

Burke now made straight for the beach with Ellen, Smith and four others. These seven men had become separated from the rest of the patrol when the movement through the jungle had accelerated but Urquhart knew the general plan. The smaller group found themselves well south of the landing beach and raced north along the sand without worrying about the enemy, in order to get into their signalling positions as soon as possible. Breathless and soaked, the seven men set up the signalling lights (five minutes late according to the plan), red lights 600 yards apart on the flanks and a white light in the centre. The lights were positioned on a high bank of sand whence they could be seen from the sea even taking account of the height of the waves which Burke estimated was about 10 feet. For about half an hour the men waited tensely for some movement from the sea. They then saw figures moving rapidly up the beach and believed they were Japanese approaching from Bassis. Burke had already withdrawn his men from the lights and now they returned to the shelter of the jungle. The “Japanese” were actually Urquhart and the rest of the party who had reached the beach too far south and had moved rapidly north where they had also begun to signal with two lights. At the same time as Burke’s men saw the group approaching from the south (about 12.30 a.m.) they heard the throb of engines in the bay. “It was at this psychological moment,” wrote Burke later, “that the first of the landing craft hit the beach – and I really mean hit.”

The convoy of landing craft had experienced great difficulty in finding the beach. The leading and central boat of the first wave, carrying two key figures, Colonel Taylor and Captain D. A. McBride, as well as 29 troops, had an unfortunate experience. After two hours the lieutenant in charge of the first wave and leading boat informed Taylor that he was doubtful whether his craft was capable of reaching its destination. He suggested that the more important members of the boat should transfer to the next craft, called to the next craft to come alongside, waved the remainder on and began the trans-shipment – no easy task in the rain, the darkness and the high sea. By the time that five had trans-shipped the first wave had disappeared and the second wave had passed through. The lieutenant, who had also transferred, took the lead of the third flight which automatically followed. The boat led the wave on until 2 a.m. on 30th June, over two hours after the scheduled time of landing, when all began to be smitten with sickening doubts about their whereabouts.

At 3 a.m. Taylor ordered the wave to turn south. After milling about in what McBride considered was Lokanu Bay, the boats again headed for the open sea and proceeded south for two hours. McBride recognised Lasanga Island and suggested to Taylor that he could navigate to Nassau Bay. At this stage it was noticed that eight of the boats that had been following closely had disappeared. As always with men trying to reconcile their fears with their duty, there was now some vacillation. An opinion

was advanced and eagerly seized upon that it was doubtful if the landing had taken place. Making the best of a bad job the remaining three boats put into Buso where men at Hitchcock’s rear headquarters stated that the landing had indeed taken place. McBride, a bewildered passenger, classed the transfer as a “complete mystery”, particularly as the first boat, minus the lieutenant, landed on the first night. The other boats of the third wave returned to Mageri Point.

Except for McBride’s report there is naturally no Australian account of what happened in the landing craft at the actual landing. Both the American infantry and American boatmen have left accounts which vary in detail although they coincide in general.

Everything went wrong during the landing at Nassau Bay (wrote the historian of the 41st Division). The leading PT boat overshot the beach; in turning back, several of the boats carrying the first wave were lost and much time passed before they could be located. By this time the second wave was moving ashore and crossed in front of the first wave, almost causing a collision. As the boats approached shore they found a ten to twelve-foot surf pounding the beach. Utter confusion reigned throughout the landing. Boats of the first and second waves attempted to land at the same time in an interval between two lead lights which covered only half of the landing beach. There was a great deal of congestion and, due to the high surf, many of the craft were rammed onto the beach and were unable to get back to sea. Later boats ran into these beached craft or over the open ramps. Of eighteen boats which landed only one made it off the beach and back to sea. All others broached and filled with water as the high surf pounded against them. Despite the rough sea, beaching of the landing craft, confusion and congestion, no men were lost or injured and the only equipment lost were some Aussie radios, which made communications somewhat limited thereafter. ... The leading elements discovered, after they landed, that the Australian platoon had been lost and had arrived at the beach only in time to establish two lead lights, instead of the three that had been planned.17

The historian of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade thus described the voyage and landing:

Escorted by only three PT boats, the convoy inched northward a few miles off the enemy-held coast through the inky darkness and into ever increasing rain, wind and heavy seas. ... The PT boats were too fast even at their lowest speed for the convoy and could not effectively guide it. Their craft cruised at twenty-five knots, ours at eight. One wave of boats got off the course entirely. ... The main group of boats finally located the landing beach. An Aussie patrol from the mountains had infiltrated through the Jap lines to the objective beach and flashed recognition signals to the convoy. They were barely visible in the murky, rainy darkness. ... The Amphibs ... directed their boats straight toward the lights of the Aussie patrol and pulled their throttles wide open. It was obvious to the experienced boatmen that the barges could not be beached successfully in the churning surf, which was now running twelve feet high, but orders were to land that night. So land they did, an hour after midnight,18 even though the boats were

tossed about like match sticks as they approached the shore. Much equipment, weapons and ammunition were lost in the landing but every soldier was put safely ashore. Most of the boats were unable to retract and twenty-one of them were left swamped on the beach, twisted in every direction while the surf pounded them into distorted shapes within a few minutes.19

The confusion of the landing was accentuated by the absence of the battalion commander on whom MacKechnie was relying to look after operations while he himself would concentrate on establishing a base. Despite the confusion and mishaps, the fact that a landing did take place at all was a remarkable feat. As Burke wrote later: “It was a great effort on the part of the troops and the inexperienced navigators in the landing craft, that they ever managed to reach the beach in one piece.”

Between the landing of the two waves Burke moved all lights 200 yards farther north to prevent the boats from bunching – the boats of the first wave had mostly made for a position from the centre light to the south light when 8 of the 11 boats had broached. It had been intended that Captain George’s company of the I/162nd Battalion would move about 300 yards north of the northern landing light and Captain Newman’s a similar distance south of the southern light. As the landing craft had broached, the company in the PT boats could not be trans-shipped for landing and returned to Morobe.

Unfortunately both regimental and battalion headquarters, portions of three infantry companies, the hospital, the engineers, the men manning the landing craft and other service detachments were dumped together in a very small area where the sub-units became intermingled. The inexperience of the Americans was apparent to the small Australian party on the beach from the way several smoked and many spoke in loud voices. Urquhart sent his men moving among the Americans to urge them off the beach and into cover, and by dawn the two flanking companies had been guided to their positions and had been assisted in fixing their defences. About three hours after the landing Burke met MacKechnie who was dismayed at the mishaps suffered by the craft and upset that so few of his troops had landed.20 Although no contact was made with the enemy that night several recently-abandoned weapon-pits were found immediately inland.21

Nor was all well with the Japanese in the Nassau Bay area. Major Takamura had been relieved of his command of III/102nd Battalion by Major Oba. Speaking to his officers on the eve of his departure Takamura said: “There is still insufficient understanding and zeal in execution. It is a regrettable fact that with a lack of clearness of understanding, there have been many instances of failure to get any practical results. To be specific: there is a lack of quick, reliable transmission of orders; slowness and lack of comprehension in carrying out plans; leaders are lacking in eagerness to serve; they are not strict in supervision of their subordinates; and there are those whose sense of responsibility cannot be relied upon. Reports are

greatly delayed, some are not straightforward and frank, and there has been much carelessness and many mistakes in the various investigations; hence, opportunities to advance our objective are lost.”

General Nakano was anything but pleased with the showing of his force at Nassau Bay. He issued a severe lecture to his senior and middle grade divisional officers about their lack of willpower, their poor leadership, their prevalent whines, their feeble morale, their lost prestige, and their lack of attention to detail. He said that they had “forfeited their trust and confidence because of the contradiction of their words and deeds”.

Other changes were occurring in the Japanese area. On 29th June Nakano ordered Major-General Chuichi Muroya, commander of the infantry of the 51st Division, to protect and fortify Salamaua. Under command Muroya would have the III/66th Battalion and two battalions of the 102nd Regiment, together with artillery and ancillary troops. The new command would be established from noon on 30th June.

As MacKechnie’s wireless sets had been submerged during the landing Savige and Moten knew nothing about what had happened at the beach. A reconnaissance aircraft reported at 1.15 p.m. on the 30th that 19 barges (actually 21) were lying on the beach at Nassau Bay and that troops were clustered along the foreshore. As all landing craft were to be clear of Nassau Bay by dawn to avoid air attacks, Savige and Moten knew that something must be wrong. Moten had telephone communication to the last spur, but his patrols thence had not yet made contact with the Japanese or the Americans.

At 7 a.m. on the 30th the platoon sent out by Dexter the previous afternoon returned and reported having gone beyond the suspected Japanese position without making contact with the enemy. As a second patrol was unable to ascertain if the track to the coast was clear, Lieutenant Roach’s platoon was sent east at 11 a.m. in an attempt to attract the enemy. It returned at 5.30 p.m. and reported being fired on about 400 yards from the coast. The platoon engaged the enemy for about 30 minutes and withdrew when a gun opened fire from north of the Bitoi. Roach occupied an ambush position 300 yards farther back for an hour but the enemy refused to fall into the trap.

Dexter telephoned this information to Moten and was ordered to move forward early next morning and destroy the enemy at the mouth of the south arm of the Bitoi by 9 a.m. It was a wild rainy night and the Victorians were soaked to the skin. In Dexter’s opinion his company, which had received no let-up since 19th June, was exhausted; men were falling asleep on their feet and were in no condition for fighting. The voice of Moten came over the wire emphasising that the task must be done and Dexter, having given his assurance that it would be, sent for a section from his reserve platoon at Napier to take over the last spur position. Success or failure was to be indicated by pre-arranged Very light signals. MacKechnie Force would then attack the enemy position at 11 a.m. Savige told Fuller about this, and the orders were sent to MacKechnie in a message dropped by a Wirraway and carried by PT boat from Morobe.

On the morning after the landing Captain George’s company of the I/162nd Battalion began patrolling towards the mouth of the Bitoi while Captain Newman’s patrolled towards the mouth of Tabali Creek. Urquhart

was requested to move with George’s company towards Duali, assisting and advising him where possible. The Allied patrol advanced north along the coastal routes in the general direction of Duali. After half a mile Urquhart’s forward scout, Corporal G. L. Smith, shot a lone Japanese on the inland track. Hearing the firing George moved his company to the inland track, after which Urquhart decided to leave the Americans there and advance along the coastal track. Soon afterwards the Australians were pinned down by machine-gun fire coming from the direction of Duali. Private Shadbolt with his Bren, assisted by Private Skuse,22 ran forward and cleared the track. Soon afterwards Private Barwise23 noticed two Japanese setting up another machine-gun on the beach ahead and, with grenades from his grenade discharger, killed them both and destroyed the gun. George’s company meanwhile had gone to ground. American mortars were fired indiscriminately in the direction of Duali.

MacKechnie ordered Newman’s company north from the Tabali to help George’s company. Leaving one platoon in a defensive position 200 yards north of the Tabali, Newman joined George in the early afternoon and slowly advanced towards the south arm of the Bitoi. At 4.30 p.m. the platoon near the Tabali reported that the enemy had crossed the river near its mouth and were moving inland towards the American flank. The platoon was ordered to move north and establish a defensive position from the beach to the swamp at the south edge of the actual beach-head area. While moving to this position it was attacked, at 4.45 p.m., and had to fight its way back towards the beach-head, losing its leader and four men killed. To support it the two northern companies were now moved back to the beach-head.

Indiscriminate firing continued, and after dark the Americans apparently thought that they were being attacked from all sides. They reported that the enemy were using machine-guns, mortars, grenades and rifles with tracer ammunition, and at the same time calling out names and English phrases. Because the night was so dark physical contact was necessary before the outline of a body could be seen and the Americans believed that several Japanese infiltrated their positions. As a result of the firing throughout the night 18 unfortunate Americans were killed and 27 wounded. Of this night, which the Australians dubbed “Guy Fawkes night”, Urquhart commented: “My blokes went to ground and stayed there. Not one man fired a shot.” Even in experienced units “itchy finger” often led to accidental casualties at night. In this case the night was pitch black, the noises of the jungle appeared magnified by the noises of the surf until the hearers were sure that the enemy was upon them, and the nerves of the Americans were on edge because of their skirmishes to the north and south of the beach-head during the day. There was a little mortar fire and the enemy sent over some tracers, evidently with the object of getting the Americans to fire back and

disclose their position. Undoubtedly the enemy had been prowling around at night and some small attacks were possibly made, as reported, but it is improbable that any large attack took place. It was a relief to all concerned when morning came.

On this second night, when the Americans were again concentrated in a small area on the beach-head, three landing craft, one of which contained Colonel Taylor and Captain McBride, attempted to land. Although the boats approached to within 150 yards of the shore and moved up and down, with much signalling and shouting, there was no reply from the shore. It is possible that the boats approached the wrong shore, for there are no reports of such signalling and shouting by any of those ashore. The three boats returned to Buso.

On 30th June reports of the landing began to reach Japanese headquarters. Major Kimura of the III/66th Battalion was immediately ordered to send about 150 men south from Salamaua to reinforce the fight of Major Oba’s III/102nd Battalion against the invaders and to halt them, if possible, north of the Salus area. Colonel Araki ordered the remainder of his 66th Regiment, in the Mubo area, to be prepared to cooperate with Oba. The Japanese commanders estimated that about 1,000 men had landed.

By dawn on 1st July Dexter’s company was ready to move forward. After a strafing attack by Beaufighters at 9 a.m. the company went straight through the enemy position which had obviously just been abandoned, and reached the coast. Dexter sent back a runner to the last spur with a telephone message for Moten (he had been unable to fire the Very lights as arranged because they were too damp), and at 10.40 a.m. Moten learnt that the route to the coast was clear. Patrols pursued the enemy, who fled north without seeking an engagement. On receiving the telephone call Moten, who was very worried at the non-appearance of the Americans at the last spur, instructed Dexter to make contact with MacKechnie, give him details of the situation, hand over responsibility for defence of the area at the river mouth and then proceed to Napier.

The force dispersed from the mouth of the Bitoi consisted largely of a machine-gun company from Oba’s battalion. This company had lost two of its platoons when the Heiyo Maru was sunk off New Britain in January 1943. In January a force from the 102nd Regiment, including machine-gunners, had been sent to Mambare but with the advance of the Americans through the Mambare and Morobe areas the force was gradually withdrawn to the Bitoi area.

At the same time that MacKechnie Force was being tossed ashore, the leading Papuan platoon took up a position along the ridge at Cape Dinga overlooking the Bassis villages. On 1st July a patrol under Sergeant Beaven24 drew the Papuans’ first blood in the Nassau Bay area when three Japanese were killed in foxholes. Although a strong patrol led by Lieutenant Bishop25 was forced to withdraw from the Japanese positions near

the coast after striking strong opposition, the company continued to keep pressure on the enemy in the Cape Dinga area. MacKechnie had no means of communication with the Papuans but Captain Hitchcock arrived on 1st July with news that two enemy outposts on Cape Dinga had been deserted, but that a few Japanese were still in Bassis No. 3. Hitchcock Was then sent to make contact with the American platoon near the Tabali before continuing with his task of attacking the enemy on the north coast of the Cape Dinga peninsula and blocking any escape inland along the track leading to a saddle at the west end of the peninsula.

Early on 1st July Newman’s company again moved south but dug in 1,000 yards north of Tabali Creek. During the 600 yards’ advance the company reported finding about a dozen dead Japanese and meeting several stragglers. The rest of the force remained concentrated on the beach-head. The Australians on the beach-head did their utmost to instil confidence into the Americans. Burke remained with MacKechnie while Urquhart and his platoon helped with the re-establishment of defensive positions and Major Hughes,26 a liaison officer from NGF, tried to organise communications. Soon after midday the three barges containing the missing battalion commander and McBride arrived at the beach. When MacKechnie informed McBride that his force was the victim of “considerable misfortune”, McBride, who had been briefed by Moten and Wilton and who was the only Australian present fully acquainted with the whole plan, suggested that it would be a good idea to send George’s company north to the Bitoi and Newman’s company south to the Tabali. The arrival of Dexter and a small party of the 2/6th Battalion who had walked unhindered from the mouth of the Bitoi lent point to McBride’s suggestion and induced MacKechnie to issue orders to this effect.

Dexter reported to MacKechnie who was sitting in a tent surrounded by his men in foxholes. The Americans had done little patrolling to find the enemy’s whereabouts but now MacKechnie asked that Dexter should lead Urquhart’s platoon and some Americans south to clear the mouth of the Tabali. The Australian instead urged MacKechnie to move towards Napier. The American, however, decided that his troops were too inexperienced and tired to move and that their supplies were inadequate. Dexter then returned to the mouth of the Bitoi after Burke and Urquhart had emphasised that no one should approach the American perimeter at night and that the Australians should take no notice of any shooting from the beach-head. Only mosquitoes attacked the Australians at the mouth of the Bitoi that night, and all was quiet except for some shots from the American perimeter.

Next morning Dexter returned to the beach-head and arranged for MacKechnie to have a company ready at midday to be escorted to Napier. The Australians were now without rations and received MacKechnie’s permission to retrieve broken cases of food from a foundered ration

barge; needless to say several “broken” cases were found. Towards midday MacKechnie walked to the mouth of the Bitoi and here agreed with Dexter’s suggestion that the Bitoi Track should be protected by establishing one platoon at the river mouth, one platoon at the former enemy camp 400 yards inland and one platoon at the last spur. With this protection the engineers would be able to begin work on the jeep track.

Dexter had already sent Moten a message suggesting the company’s recall. MacKechnie appeared reluctant to lose the services of the Australians but, just as he was trying to apply pressure, Private Trebilcock arrived, wet through, with a message from Moten instructing Dexter that his task was now finished and that all responsibility for the area should be handed over to MacKechnie. Trebilcock had set out from the last-spur camp accompanying two line-laying signallers but had met a party of Japanese. The signallers retraced their steps towards Napier, but Trebilcock ran into the jungle, dived into the Bitoi, and swam down towards the coast, thus getting the message through. MacKechnie, now realising that the Australians were bent on moving westward, asked that they should clear the track back to the last spur. Dexter agreed and left Lieutenant R. J. H. Smith and two men to guide the American platoon.

The main body of Australians had hardly settled in at the last-spur camp when they heard firing from down the track. They waited on the alert and presently Smith and his two companions accompanied by the American platoon commander arrived. They had been fired on by a small Japanese party and had been cut off from the American platoon which had decided to move back to the beach. Dexter immediately sent out a patrol which found the missing Americans who were told what was expected of them. They were given a position in the perimeter with instructions not to fire without orders. The telephone line was then taken through to the beach-head. At the last-spur camp troops had a peaceful night and no shots were fired.

Lieut-Colonel Matsui, the commander of I/66th Battalion, in an Intelligence report on 1st July stated that the Australians were “assembling in the coconut groves 21 kilometres from the coast opposite Lababia”. Other units listed as soon due to arrive in Salamaua were the I/80th Battalion (20th Division) 400 strong on 2nd July, and I Battalion of the 14th Field Artillery Regiment, consisting of 146 men and six mountain guns, next day.

Savige now ordered Moten to instruct MacKechnie that the Papuan company should as soon as possible advance along the coast north of the Bitoi with the tasks of maintaining contact with the retreating enemy, mopping up pockets of resistance, and ultimately reconnoitring for a secure bridgehead for landing barges in Dot Inlet. Time should not be wasted by operations against any Japanese in the Cape Dinga area as these could be contained with a minimum force and dealt with at leisure. Already irritated with events at the beach, particularly the lack of decision and the concentration of troops which invited air attack, Savige told Moten by telephone to issue orders to MacKechnie as to one of his own battalion commanders, and to report any failure on the American’s part

to obey orders. Savige also urged General Fuller, commanding the 41st Division, to send the remainder of his engineers and artillery to Nassau Bay as soon as possible and to instruct MacKechnie that his forward elements must begin to move from the beach-head to the assembly area.

The scanty reports received by Savige and Moten under-emphasised the actual confusion at the beach-head. Moten had attempted to ring MacKechnie at Nassau Bay on the night of 1st July. A long conversation had ensued with the American signaller at the end of the line, the gist being that he could not fetch MacKechnie because anyone who moved would be shot and in any case he was closing down about 9 p.m. as soon as he had heard the BBC news.

MacKechnie was convinced that his force had received a severe mental and emotional shock. By 2nd July a headquarters and supply dumps had still not been organised and no orders were being issued except those covering affairs of small importance. At dawn a further 10 boats arrived, carrying mainly the fourth infantry company, and two PT boats accompanying the landing craft bombarded enemy positions at Cape Dinga.27 Troops and supplies remained concentrated at the beach-head making ideal targets for air attack. At p.m. 10 Japanese medium bombers bombed and strafed Nassau Bay and both sides of the mouth of the south arm of the Bitoi, some of the bombs falling near Corporal McElgunn’s patrol which had returned to the Bitoi mouth and reported that Duali seemed empty. At 3.10 p.m. a further 8 bombers and about 15 fighters attacked. The only damage was done by a direct hit on one of the broached landing craft.

Hitchcock reported that the enemy outposts on Cape Dinga peninsula had been evacuated and late on 2nd July the Papuan company began skirmishing with enemy remnants in Bassis 2. Newman’s company reached the Tabali late on the 2nd but had not yet made contact with the Papuan company advancing west along the coast. It began to seem that the enemy had evacuated the Cape Dinga area because Newman’s men found between 50 and 60 Japanese packs abandoned near the Tabali.28 Later reports from farther north that a similar number of Japanese had been seen moving north across the Bitoi added weight to this belief.

Early on the 3rd the Americans began moving towards Napier. They were slow mainly because they were not used to hard jungle marches and carried too much gear. Helped by the 2/6th, Colonel Taylor’s headquarters and three infantry companies moved inland. The Australians returned in the afternoon and by 5 p.m. were at Napier, whence they would move to the Saddle next day. The example of determination, efficiency and coolness shown by these experienced soldiers had helped the Americans to reorganise and proceed with their task.

To Savige’s disappointment MacKechnie was at least one day late by 3rd July. The position was improved, however, by the arrival at Nassau Bay that day of one battery of the 218th Field Artillery Battalion, an engineer company and other detachments. The artillery lifted the spirits of the Americans at the beach-head and along the Bitoi Track and the Australians in the distant Mubo hills when from 1.35 p.m. its four 75-mm guns shelled for 50 minutes the mouth of the Tabali Creek, Cape Dinga, Lababia Island and the area from the mouth of the south arm of the Bitoi to Duali.

By 4th July 1,477 troops of MacKechnie Force had been landed at Nassau Bay.29 At 3.30 p.m. on the 4th Taylor’s battalion was spread out between its assembly area at Napier and the beach. Headquarters and two companies were at Napier and another was in the dry creek bed east of Napier. To keep this force supplied all available men including gunners and sappers carried supplies to Napier on 5th July. This supply train was ambushed about three miles inland but the enemy scattered and fled across the Bitoi after killing three Americans. At this time the jeep track running west from the mouth of the south arm of the Bitoi was open to traffic for half a mile along the river. The gunners as well as 150 natives were assisting the American engineers in its construction. Unfortunately the tractors and bulldozers were out of action either through being stuck in the stream or bogged in the mud, and in order to keep to the program Savige told Moten to set the Americans working on the track with picks and shovels.

MacKechnie had different ideas. In a letter to Moten on 4th July he said that loss of over half his landing craft and his inability to get his guns, troops and supplies in as originally scheduled had materially delayed him. He considered that it would not be tactically sound to leave his base, with Japanese about, in order to concentrate all his troops 8 to 10 miles inland with no supplies. It would take, he thought, three weeks, not two days, to construct the artillery road; troops at the assembly area would be out of rations tomorrow, and there were no native carriers. “To be very frank we have been in a very precarious position down here for several days and my sending the rifle troops inland was contrary to my own best judgment.” Troops had gone inland “stripped to the bone”, he wrote, and without heavy weapons and mortar and machine-gun ammunition. “Therefore, these troops who are up there now are in no position to embark upon an offensive mission until we are able to get food, ammunition and additional weapons up to them.” General Fuller had advised him not to embark on offensive operations unless adequately supported by artillery and heavy weapons. “In short I must advise you at this time that it will be impossible for me to comply with the orders as they now stand.” MacKechnie concluded by suggesting that the plan be changed, that he would not and could not sacrifice lives to meet a time

schedule and that he did not plan to leave the beach until the position was secure and supplies adequate.30

Moten informed Savige of the letter and suggested that pressure would be necessary if operations were to proceed as now planned for 7th July. Moten then informed MacKechnie that arrangements had been made to drop supplies to Taylor on 5th July and that Bitoi Ridge was not occupied by anyone except Australian patrols waiting for the Americans to take over. He advised MacKechnie that heavy machine-guns could not be used on Bitoi Ridge but mortars would be useful. In Moten’s opinion casualties to MacKechnie Force would be unlikely and one or at most two companies resolutely led could capture and hold the objective. Best news for Moten was that, with MacKechnie’s consent, he could now deal direct with Taylor, who was willing and anxious to carry out the attack as planned but hampered by lack of supplies and ammunition. Moten arranged for the delivery to Taylor of 100 boy-loads of ammunition from the beach on 6th July and 1,000 rations from 17th Brigade.

Reports from the Australian liaison officers at the beach (Major Hughes, Captain McBride and Captain Rolfe31) caused Moten to suggest to Savige on 6th July that Fuller be asked to send an officer to take charge of and relieve MacKechnie of responsibility for beach organisation. Aware of the danger of delay to the plans for the attack on Mubo, Savige relayed this to Herring and informed Moten: “I have placed MacKechnie under your command and he must obey orders and instructions issued by you.”

The dangers of dual command were already sensed by Savige. Although it was stated in operation orders emanating from NGF’s instruction of 26th May that the Americans were under Australian command, and although it had been confirmed at the Summit and Port Moresby meetings, the question who really commanded the Americans was not really settled. MacKechnie thought that he had to serve two masters – Savige and Fuller. Back in Port Moresby Herring understood the delicate nature of the problem and felt that Fuller might protest to MacArthur if the Americans were placed under the command of an Australian several mountains away from the coast. Herring decided that one of his main tasks was to ensure smooth cooperation between Americans and Australians and for this reason he was diffident about placing the Americans completely under Savige’s command. In Savige’s own mind, however, there was no doubt that Herring’s written and oral orders clearly placed the Americans under Australian control.

Because of this uncertainty both the Australian and American divisional commanders were apt to misinterpret each other’s actions. An example was contained in an exchange of signals following MacKechnie’s landing. On 1st July Moten advised Savige that planes were attacking Duali and that, if they were Allied planes, they would “endanger our troops and ... prevent attack planned”. Savige replied that the attack was arranged without his concurrence and promptly changed the bomb-line. At 10 a.m. he signalled Fuller: “Air attack arranged by you for 8 a.m. on targets Duali-Bitoi mouth should have been coordinated at this HQ. This attack may endanger troops of the 17th Bde who were in target area at time of attack ... requests for air attacks by you direct from MacKechnie must be referred here for coordination to avoid repetition today’s attack.” Late that night Herring asked who had altered the bomb-line and, on being told that Savige had done so to avoid danger to his own troops, signalled that he “would be glad if you would communicate your regrets to 41 US Div”. About midday on the 3rd Savige signalled Fuller that “attack not arranged by me or Air Support Party here. Assumed arrangements had been made through you as MacKechnie had no communication with us. Took prompt action to alter bomb-line to avert certain danger to our troops.”

Late on the 3rd Savige received Fuller’s reply (dated 1st July) to his first message. Fuller said that he had not arranged the air attack but that a request for an air support mission had been received at 41st Division headquarters and had been relayed to 3rd Division headquarters, which had received it at 9.25 p.m. on 30th June, and to First Air Task Force. Clearance for the mission had been given by the Fifth Air Force during the night of 30th June. Fuller concluded that “all requests for air attacks will be forwarded to your headquarters as was done in this case”. On examination it appeared that the Americans had acted on an information signal between Air Support Parties at the two divisional headquarters and had not used the proper procedure to obtain coordinated attacks. On receipt of Fuller’s delayed signal Savige replied late that night: “Your signal now clarifies whole matter and emphasises difficulties in communications leading to misunderstandings and assumptions by reader not contemplated by sender. You have my regrets for either as may be applicable to me.”

This incident has been fully described in order to show how dual command could lead to much unnecessary work, worry and misunderstanding. Whenever the allocation of command is deliberately or unconsciously left vague, there is trouble. This incident might well have served as a warning to prevent further such incidents. But for the sane attitude of the commanders and the genuine friendship between the Australian and American troops in the front line, relations between the two commands might have been strained at this time. Give and take was necessary on both sides.

Order very gradually came to the congested beach-head. Hughes assisted with the organisation of American headquarters. Captain Wilson,32 an

engineer officer sent by Moten, assisted the American engineers in the construction of a jeep track. Rolfe and D. A. McBride were hard at work urging the gunners to attempt to manhandle their guns. Communications remained the most unsatisfactory feature, as American signallers appeared reluctant to do night work.

On 4th July Savige informed Moten that the attack against Mubo would open on 7th July. Moten then advised MacKechnie and Taylor that Taylor’s move from the assembly area at Napier to his objective on Bitoi Ridge would also begin on the 7th, and that this move would be coordinated with attacks by 15th Brigade to the north and 2/6th Battalion to the west. Adopting a persuasive tone, Moten informed the American commanders that it would be desirable but not essential for MacKechnie Force guns to be in position by 6th or 7th July.

While Taylor was moving west, Oba was moving north. General Nakano’s headquarters on 7th July estimated that 4,000 had landed at Nassau Bay.

Most of the Japanese from Nassau Bay escaped to the north to join in the fight again. Small detachments, particularly those whose foxholes the Americans found soon after landing, scattered into the jungle and moved north; they either starved or helped themselves to American rations. One of these more resourceful Japanese was Sergeant Taguchi who left the following entries in his diary: “About 0230 hours (30th June) there was a sudden enemy landing at Nassau Bay and 6 of us – Sergeant Taguchi, Leading Private Shimada, Pfc Takata, Takano, Ohata, Superior Private Ishijima – escaped to the jungle according to company orders. I was not able to walk by myself so Pfc Takata helped me and we went deep into the jungle. Due to my condition, both of us were determined to die at that place. The Hori Company arrived at the place at 0730 and engaged the enemy.”

Three weeks later Taguchi and Takata were still in the area and Taguchi wrote: “As it grew darker, advanced closer to enemy voices. Moved slowly on all fours since it was too dangerous to walk. This stealing is a difficult proposition. Got lost on the way. Was so dark I could not see anything and had to feel my way. ... Wish they would hurry up and go to sleep. Mosquitoes are coming at my outstretched legs. I am getting sleepy too but I cannot do that. About [10 p.m.] it suddenly started to pour and I got soaking wet. Time has come. Moved out to the path and advanced cautiously. What an uncomfortable feeling! Moon came out. When they smoked their cigarettes I was watching for the direction and distance. ... There seemed to be no one in front, so I walked up and found a large barrel. I thought it was oil because it was still dark. I searched the place and found many ... large and small tins of canned foods and dry foods, which Pfc Takata would Like to eat, and there seemed to be dozens of them. This joy could not be expressed. I took my bayonet and opened the can and ate the contents. The taste was never so good as this. We had been eating taro before this for over ten days.”

Next day, 22nd July, Taguchi wrote: “Looking at the things which I brought last night, there were 29 small and large cans and 3 large loaves of bread and one extra-large can. After segregating these, there were 11 cans of corned beef, 9 cans of milk, 3 cans of peaches and 7 cans with unknown contents.”