Chapter 5: The Capture of Mubo

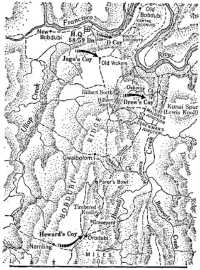

IN the last days of June the 15th and 17th Australian Brigades were preparing for the operations that were to follow the American landing at Nassau Bay. The 15th Brigade was to capture Bobdubi Ridge beginning on the day of landing, while the 17th was to begin the capture of Mubo and Observation Hill a week later. The 17th Brigade would have the main task while the 15th Brigade would draw off some of the enemy forces and then close the escape route north from Mubo.

Brigadier Moten’s orders issued on 2nd July (after the 15th Brigade’s opening move) stated that the 2/6th Battalion supported by the 2/5th would attack the Mubo–Observation Hill area on 7th July and would then mop up the area south from the junction of Bui Savella and Buigap Creeks, and join the Americans from Bitoi Ridge at the footbridges across the Buigap. The orders continued that the I/162nd Battalion would capture Bitoi Ridge on 8th July and, a day later, the ridge between Bui Alang and Bui Kumbul Creeks and the small feature west of Bitoi Ridge between Bui Kumbul Creek and the Bitoi River overlooking the footbridges, where the Americans would make contact with the Australians and cut the Japanese lines of communication along Buigap Creek.

After receiving the 15th Brigade’s operation order on 22nd June Major Warfe of the 2/3rd Independent Company and Colonel Starr of the 58th/ 59th Battalion issued their own orders four days later. Warfe’s order covered two diversionary patrols designed to deceive the enemy as to the direction of the main attack. The first was to raid the Malolo and Bukuap areas on the coast and the second to make a demolition raid in the Kela Hill area.

Lieutenant J. E. Lewin led the Malolo patrol of 16 from Missim on 27th June and on the morning of the 29th they watched small enemy parties along the coast at Busama and Bukuap. At midday George, the plausible son of the local luluai, joined the patrol and later the luluai of the area arranged for the evacuation of all Wamasu natives. George, who had been absent for some time, returned at 4 p.m., stating that the natives would be moving to Hote that night. At 4.30 p.m. Lewin withdrew his guards and while he was issuing orders for the raids on the following morning about 30 Japanese attacked from two directions. The Australians managed to get a few shots at the encircling enemy, but they had only one course and that was to depart in a hurry. They split into three parties and rejoined at the rendezvous with the company of the 24th Battalion on the Hote Track. Unfortunately the patrol lost seven weapons, including its Bren gun. The loss of a weapon was always regarded seriously and this loss undoubtedly took a lot of explaining to Warfe. Often when there was the slightest relaxation of precautions by a patrol operating deep into enemy territory the Japanese were able

The 17th Brigade attack on Muho, 7th–13th July

to carry out a surprise attack. Their good fieldcraft and use of native intelligence was usually offset by their inaccurate shooting. In this case, although the foremost Japanese were only 10 yards away when first seen, they inflicted no casualties. Lewin had possibly been betrayed by George and the luluai.

The other diversionary patrol, consisting of Sergeant Swan1 and five men, was moving forward to place demolition charges on the Japanese anti-aircraft guns at Kela Hill when, at midnight on the night 29th–30th June, it was challenged and fired on by a sentry. Machine-gun and mortar fire forced Swan to withdraw without being able to lay his charges. Although unsuccessful, both patrols probably helped to make the Japanese doubtful as to the direction from which the main attack might come and may have caused the enemy to delay sending his reserves to the Bobdubi and Mubo areas.

The 58th/59th Battalion had been moving forward throughout most of June. On 26th June Colonel Starr issued the operation order for the battalion’s first action: “58th/59th Battalion will capture Bobdubi Ridge with a view to controlling Komiatum Track”, it stated. Each company was allotted a detachment of 3-inch mortars. One company was to take Orodubi, Gwaibolom and Erskine Creek;2 another was to take Old Vickers Position and the village west of it; a third was to take portions of the Government Bench Cut Track South-east of Old Vickers. The fourth company was in reserve, with the task of preventing encirclement along the New Bobdubi Track and guarding the river crossings and the kunda bridge area. The 2/3rd Independent Company was to supply three guides to each company.

On 28th June Colonel Guinn issued to the 58th/59th Battalion one of those rousing orders of the day of which he was so fond; it adequately summed up the importance of the battalion’s task:

Bobdubi Ridge which is your objective is the key to the situation extending south to Mubo area. Its occupation means that we will be placed in a position to prevent the enemy reinforcing or supplying their forward areas. Further, those forward will be trapped like rats in a trap – it will be your duty to see they are annihilated in attempting to get out. By your determination and courage to carry out the heavy task allotted you will win the day thereby adding your first battle honours to a unit with a fine tradition during the years 1914-18.

This Victorian battalion, young, inexperienced and inadequately trained through no fault of its own, needed all possible encouragement. After the battalion had moved forward at night, company by company, to Meares’ Creek, Captain Millikan,3 its medical officer, felt that the men were fatigued, as they had had little rest since the march forward over the gruelling Missim trail; prepared accommodation and rations were scarce at Pilimung and unsatisfactory hygiene, resulting from the troops’

58th/59th Battalion attack, 30th June

weariness in the arduous crossing of Double Mountain, had caused outbreaks of diarrhoea or dysentery, tropical ulcers and tinea.

On the same miserable night that MacKechnie Force landed at Nassau Bay the men of the 58th/59th crossed the Francisco River on a swinging kunda bridge erected by their Pioneer platoon, and early next morning plodded towards their start-lines in torrential rain. The bad weather hampered the air strike planned for 8.30 a.m. on Gwaibolom, Old Vickers and the Coconuts area. Only four aircraft got through low clouds to the target area, the remainder dropping their bombs on Salamaua.

The three attacking companies left their start-lines near Uliap Creek in the early morning of 30th June. Major Heward4 in command of the southern company planned that Lieutenant Roche’s5 platoon would capture Orodubi, Sergeant Barry’s6 would move through to Gwaibolom and Lieutenant Houston’s7 would move through to Erskine Creek. A section sent north to Graveyard saw about 10 Japanese strolling round Orodubi and fired on them, causing them to jump into pits under the huts. Roche’s platoon then attacked Orodubi at 12.30 p.m. Anticipating booby-traps the men left the Bench Cut Track 70 yards south of Orodubi, climbed a 40-foot kunai slope and joined the main track within 10 yards of the enemy. They could hear the Japanese but could not see them; in the firing which now broke out the Australians were at a disadvantage as they could be seen by the Japanese. Corporal Crimmins8 was mortally

wounded and three others wounded. After 20 minutes firing and grenade throwing at close range Roche withdrew with only 10 men unscathed. During the action Private Duncanson,9 a stretcher bearer, went forward under fire and tended Crimmins and then, still under heavy fire, brought out the other casualties.

Heward then reconnoitred Orodubi from the Graveyard area to the north and from Namling to the south. By the time he had finished it was almost dusk and perhaps too late to attack. Rather than dig in where he was he withdrew to Namling, and decided to contain Orodubi with one platoon, a course which had been previously suggested by Starr. After telephoning at night to brigade headquarters (which was to retain control of the company until it had captured its objective) Heward was ordered to contain Orodubi with one platoon and move the rest to Gwaibolom and Erskine Creek next day.

Captain Jago’s10 company, which had the stiffest task, drove a Japanese outpost from the village west of Old Vickers in the early afternoon of the 30th, losing Lieutenant Pemberton11 and Corporal Gibson,12 killed, and capturing some documents. The company then had its first experience of meeting a well-entrenched and heavily-armed enemy when Lieutenant Griff’s13 platoon attacked Old Vickers. Griff’s move up Old Vickers was hounded by bad luck. Two of his men accidentally discharged Owen guns and one fell and cut his leg on a machete. The Australians did not know that the Japanese had deep dugouts 40 feet down from the top. In these they would take shelter from Allied bombing or shelling only to reappear in their foxholes on the top before the attackers could take advantage of the bombardment. As the platoon reached the top of the ridge they were surprised to see about 20 Japanese approaching from the direction of the recently captured village. Corporal Anderson’s14 section on the right flank was pinned down by heavy fire from the top of Old Vickers after they had inflicted several casualties with accurate small arms fire. Suddenly to the left the other sections saw four Japanese run yelling from a foxhole towards a Woodpecker concealed in a clump of bamboos. A grenade thrown by Griff killed all four. A group of Japanese riflemen then attacked but were dispersed by fire from a Bren. Griff now sent his platoon sergeant (Clarke15) to instruct Anderson to withdraw. On his return Clarke was hit by fire from the Woodpecker in the bamboo clump but, although in great pain, managed to make his report to the

company commander and was then dragged back by Griff. During the fighting Sergeant Ayre16 in charge of stretcher bearers did fine work going among and tending the wounded and arranging their evacuation. The platoon was now drawing fire from what Gruff estimated to be one Woodpecker, six light machine-guns and one light mortar. Using the grenade discharger the Australians unsuccessfully tried to destroy the Woodpecker. Griff crawled forward to reconnoitre its position but, unknown to him, he was crawling along a fire lane thinking it was a track. Bursts of firing from several machine-guns induced him to roll rapidly down the hill to his platoon, which had now been rejoined by Anderson’s section. As he could hear enemy on both flanks Griff withdrew about 100 yards to some high ground where he reported to Jago and was ordered to join the rest of the company in the village area. In the day’s fighting the company had lost three killed and five wounded.

Early on the 30th Captain Drew’s17 company moved towards the track junction on the right flank of Jago’s company. When Jago was held up, Starr ordered Drew to go to his objective, but the company did not reach the track junction by nightfall, mainly because its information about tracks was faulty and progress was barred by a sheer cliff face. It camped near Jago’s position. The company might well have emulated Lieutenant Stephens’ section in May by going straight east down to the Bench Cut via tracks leading from positions known later as the Hilberts18 and thence north along the Bench Cut towards the Salamaua–Bobdubi track.

With orders direct from Guinn, Heward smartly set out for his objectives on the morning of 1st July. By 11.30 a.m. Roche’s platoon occupied Gwaibolom and by 1 p.m. Houston’s occupied Erskine Creek – both without opposition – while Barry’s platoon “contained” Orodubi by setting up two Brens covering it. The Japanese did not need many troops at Orodubi as the crest of the ridge on which it stood would prevent more than one platoon attacking from the Bench Cut Track. From the Gwaibolom–Erskine Creek area Heward set up a Vickers gun to fire on the Komiatum Track.

Drew’s company set out again at 9 a.m. on 1st July towards its objective but, after “scrub-bashing” for several hours, the men carrying the mortar and machine-gun and their ammunition were exhausted. The company then slowly followed a creek until Drew called a halt and sent two lightly-equipped volunteers forward to look for a suitable route. After an hour and a half they returned saying that the country ahead was impossible for loaded troops. Unfortunately the guides from the 2/3rd Independent Company did not know this particular area. Drew therefore had the distasteful task of leading back a “bloody-minded” company to

the Bobdubi Ridge Track. It was later found that Drew was within half an hour of the Bench Cut Track when he turned back.

Plans for Jago’s company to attack Old Vickers again and for the reserve company to join in with an attack on the Coconuts were delayed on 1st July because 3-inch mortar ammunition had not arrived. Griff, however, led a patrol to the top of the ridge and sketched some of the defences of Old Vickers. The battalion learnt this day that documents captured by Jago’s company on 30th June had identified the Japanese as part of the 115th Regiment.

Jago’s attempt to capture Old Vickers, quickly following the American landing, helped to cause consternation among the Japanese planners at Salamaua. On the previous day Major Komaki, in charge of the Bobdubi sector, had upbraided Lieutenant Ogawa stationed at Old Vickers for not reporting “approximately 100 of the enemy ... seen moving towards Bobdubi through the grassy plain 9,000 metres south of the mountains”. This approach by men of the 58th/59th Battalion had apparently been seen by artillerymen. On 1st July General Muroya’s order read: “The enemy has made an opening in No. 9 Company, 115th Infantry Regiment (Ogawa’s unit) at Bobdubi, and is infiltrating also along the Komiatum Track. I Battalion commander 66th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Matsui) will dispatch one infantry company to Bobdubi to relieve Ogawa on 2nd July. Be especially careful to conceal relief operations from the enemy. When the company is relieved it will immediately return to Salamaua and guard the area.” Thus the attack drew off to the north a portion of the enemy force defending the Mubo area.

During the first two days of its operations the 58th/59th Battalion had seen very few Japanese. The Japanese were not in unexpected localities nor in large numbers, except in Old Vickers, but from their well-entrenched defensive positions they were able to drive back attacks which could not be supported by heavy weapons. Lack of battle experience and shortage of adequate rations (not an isolated event in this area) reacted on the young soldiers of the 58th/59th to the prejudice of efficient patrolling. Captain Newman19 of the 15th Brigade staff, who investigated the shortage, found that a two days’ patrol meant that those who stayed behind went hungry because rations had to be scraped together for the patrol.

In spite of heavy bombing of Salamaua and Kela Hill by Allied aircraft on 1st July considerable enemy activity was observed by the Salamaua OP in the area from the quarry to the township of Salamaua during the day. Savige warned Guinn that these movements possibly indicated a counter-attack from Salamaua on 2nd July. Hearing of this, Starr ordered Drew to leave one platoon on the right flank of Jago’s company and move the remainder to join the reserve company. Guinn did not agree with this move and ordered Starr to reassemble the company and send it to its objective via Gwaibolom and Erskine Creek.

The unusual activity observed in the Salamaua area was caused by the arrival from Madang of the I/80th Battalion, which was sent to the Bobdubi area immediately.

To guard against a possible counter-attack on Bobdubi Ridge, Savige ordered Guinn to redeploy the 2/ 3rd Independent Company on 1st July

so that they could support or reinforce the 58th/59th Battalion. When the enemy counter-attack did not take place by 2nd July Savige signalled Guinn that the Independent Company’s task would now be to prevent the escape of the Japanese from Mubo and he took the unusual step of instructing Guinn where he thought the three platoons should go. Despite the removal of the immediate threat Savige was still apprehensive about the northern flank, with the result that the company of the 24th Battalion patrolling the Malolo Track was ordered to prepare an ambush position on the New Asini Track as well. The forward patrol of this company on 7th July skirmished with the enemy on the Malolo Track about three miles from the coast.

Worried by the failure to reach the Bench Cut Track and so threaten the rear of the Japanese at Old Vickers as well as the supply route to Mubo, Starr sent the company, now commanded by Gruff, through Gwaibolom and Erskine Creek towards its objective. Having at length found the elusive Bench Cut Track the company advanced and on 3rd July set up a patrolling base at Osborne Creek, to harass both the Salamaua–Bobdubi track to the north and the Salamaua–Komiatum track to the east. Of these tasks the more important would be the Salamaua–Bobdubi track and the approach to Old Vickers. The capture of Old Vickers was essential to the capture of Bobdubi Ridge as a whole and to an effective command of the Salamaua–Komiatum track. At 5 p.m. on 3rd July the leading platoon was attacked by a party of 20 Japanese moving towards Old Vickers. In hand-to-hand fighting the Australians killed half of them, including an officer.20 Corporal Beaumont,21 who had already escaped from Malaya, killed one Japanese with the butt of his rifle. As the area of the track junctions was in a flat densely covered swamp Griff withdrew after dark to high ground near Osborne Creek.

Living conditions in this area, about 400 yards above the Komiatum Track, were primitive and uncomfortable. The company was forced to live on field operation rations as cooking of dehydrated foods was impossible because smoke might indicate the position to the enemy. Supplies of solidified alcohol, however, enabled the troops to make hot drinks in the early stages but were soon being used instead to combat tinea. As the natives were reluctant to carry beyond Gwaibolom one platoon usually had to act as carriers for the other two. The men were not downcast, however. Events in New Guinea again and again proved that troops would cheerfully endure wretched conditions if they were enjoying good hunting.

The men of the 58th/59th Battalion would have been inspirited had they known the effect which their activities were having on the enemy. Colonel Araki, commanding the 66th Regiment, issued orders on 2nd July to counter the northern moves of the Australians. “The enemy appears to have begun frontal resistance and is gradually increasing his strength at Nassau and Bobdubi. This morning there was an attack on the left front height by the enemy and the situation does not

permit any optimism; all defence areas are being strengthened. The Mubo garrison will move immediately to Komiatum to strike a telling blow at the enemy on this front. The i will hold the present position strongly and, if the situation permits, will dispatch some weapons to Komiatum tomorrow.” In another order Araki directed the Mubo garrison, except for the II/66th Battalion, to move the Mubo ammunition stores and ration dump to Komiatum. By this time General Muroya expected the main attack to develop in the Bobdubi area. As well as Major Jinno’s I/80th Battalion, he ordered Araki to dispatch the whole of Matsui’s I/66th Battalion towards Bobdubi on 3rd July. Thus the 58th/59th Battalion was again drawing off more of the enemy force facing the 17th Brigade.

On 3rd July Brigadier Hammer22 who had been at Savige’s headquarters since 26th June arrived at Missim to take command of the 15th Brigade. Hammer, a dashing soldier, had been in action as a brigade major in Greece and battalion commander at El Alamein. After handing over to Hammer at midnight on the night of 3rd–4th July, Guinn reported to Savige that the ground situation was well under control and that the enemy in Old Vickers would be surrounded and attacked. He was disappointed with some of the leadership, but stated that the attack of Jago’s troops on the village area west of Old Vickers was well done; the men had heard the Japanese run and squeal and had killed 20 out of the 40 enemy met in the area. Replying to Guinn Savige stated:

Your report on situation encouraging and verifies my faith in these boys. ... Not surprised your assessment leadership values. A broom will be necessary later.

Now that Griff’s company was in position Starr was free to concentrate on capturing Old Vickers and Orodubi. Patrols from the battalion’s four companies were active during the next few days. Early in the morning of 4th July reconnaissance patrols from Captain Hilbert’s23 company approached the North Coconuts area where they “drew the crabs” (drew fire) from the enemy in Old Vickers Position and Centre Coconuts. As it appeared that the northern end of the ridge was only lightly held, Lieutenant Franklin’s24 platoon from this company set out at 5 p.m. to attack North Coconuts. Jago poured fire from machine-guns and mortars on to Old Vickers to keep the enemy there occupied. Partly covered by this fire Franklin reached North Coconuts and prepared to dig in for the night. Success was short lived, however, as his platoon was attacked next morning at 10.30 a.m. by about 100 Japanese. Unfortunately only Franklin and 10 men were present, the others having gone back for supplies. The Japanese came on with much noise and indiscriminate firing, and blew bugles and waved flags. The depleted platoon was forced to retire, but could have inflicted many casualties had it been at full strength and able to stand its ground.

Franklin’s attack had disturbed Colonel Araki who was now apparently responsible for the battle area from the Francisco to Mubo. “The enemy is gradually increasing his strength in the Bobdubi area,” he wrote. “Strength is now about 500, a section of which has advanced to a height covered with coconut trees. Moreover it is feared that they will advance in the vicinity of the pass ... at the southern foot of Komiatum [Goodview Junction]. The enemy forces which landed in the Nassau area are also increasing their strength and are cooperating with the enemy forces on the Mubo front and it is estimated that those advancing on the Komiatum area are numerous.” Araki ordered the commander of II/66th Battalion to send a platoon to repel attacks from the west. At the same time he anticipated an attack from the south to the “Komiatum high ground”.

On 5th July a patrol from Griff’s company stationed near the junction of the Komiatum and Bobdubi Tracks saw 102 Japanese moving along Bobdubi Track towards Bobdubi Ridge. It did not fire on this force, which was apparently carrying out a relief as 120 Japanese were later observed moving along the same track towards Salamaua. Both Japanese patrols were well dispersed, and moved cautiously with weapons at the ready. Previous ambushes had surprised Japanese patrols moving in close order with weapons slung, but now they were on the alert. Casualties could undoubtedly have been inflicted on the Japanese but the numbers unharmed would have been sufficient to encircle the Australians. Griff therefore decided to reserve his hitting power for smaller parties with which he could deal adequately. Hammer was troubled, however, by what he considered was Griff’s failure to attack the Japanese on the Bobdubi Track and instructed Starr that every movement on the track must be fired on and that the offensive spirit must be built up. Next day Lieutenant Bethune’s25 platoon ambushed a party of 20 Japanese coming from Bobdubi and killed 10.

During the 58th/59th Battalion’s initiation Savige had kept the 2/3rd Independent Company in reserve in order to use it to plug any gaps caused by enemy infiltration. On 5th July he ordered Hammer to send the company towards Tambu Saddle and Goodview Junction where it would cut the Komiatum Track and prevent the enemy’s escape north from Mubo.

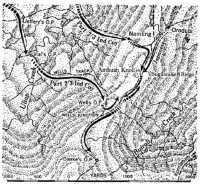

Warfe’s headquarters and two of his platoons arrived at Namling on the 5th while the third platoon arrived at Vial’s OP from Base 3. Next day this third platoon (Captain Winterflood’s) climbed to the head of the Pioneers Range and then went east along the ridge turning off at Walpole’s Track to approach Goodview Junction, while the rest of the company left Namling for Dierke’s, a three hours’ march.

The column moved from Namling in the morning with Captain Meares’ platoon in the lead followed by Warfe’s headquarters, a carrier line of 85 natives with an engineer spaced at every tenth native, and the 16 men from Lieutenant Barry’s platoon as rearguard. After half an hour the carrier line had just passed the feature known later as Ambush Knoll

Ambush Knoll, 6th–7th July

when the rear of the column was attacked by a Japanese force approaching from Orodubi. The natives, although not actually under fire, and despite the efforts of their escorts, “went bush” to Namling, leaving behind the stores including one 3-inch mortar, two machine-guns and a medical pannier containing, among its legitimate contents, the unit’s war diary. This was indeed a calamity, for rations were again scarce, and Hammer had ordered a combing of the brigade’s long lines of communication for supplies. Worse, however, was the loss of the mortar and machine-guns. Despite the confusion of the sudden attack and rapid disappearance of the natives, Barry immediately counter-attacked, killing eight Japanese for the loss of one killed and two wounded. To avoid being cut off from the main force Barry pushed on to Wells Junction collecting some stores as he went. Here he reorganised his two small sections – Lewin had not yet rejoined the platoon since his raid – and again unsuccessfully attacked the Japanese. Warfe, who had reached Dierke’s, then had to weaken his force moving towards Tambu Saddle in order to clear Ambush Knoll and recover the stores. A section from Meares’ platoon was sent during darkness to reinforce Barry while the native carriers were sent to Vial’s to quieten down. It was not until the next evening that Barry’s persistent pressure forced the Japanese to move back from Ambush Knoll to Orodubi. He retrieved the mortar and the two machine-guns.

From the beginning Hammer was uneasy at the lack of depth in the 58th/59th Battalion’s positions especially as the Missim line of communication was on the extreme north. He considered that he might have to withdraw Heward’s company to protect the north flank, but above all he strongly desired to capture Old Vickers Position. On 4th July he instructed Starr to plan an attack and two days later he visited battalion headquarters. Nor was he the only worried commander. According to the plan Bobdubi Ridge should now be in Australian hands and the 15th Brigade exploiting towards Komiatum.26 On 6th July Savige pressed Hammer for his plan for the capture of Old Vickers Position and the Coconuts.

Determined that plans should not be thwarted by any untoward delay caused by the Japanese ambush of the 2/3rd Independent Company, Hammer on the night of 6th July ordered Warfe to leave a force to secure Wells Junction while the remainder of the company proceeded with its original role. Next day therefore Warfe moved on with two platoons (Winterflood’s and Meares’) to take up positions on Stephens’ Track (Tambu Saddle) and Walpole’s Track (Goodview Junction) respectively with the object of cutting the enemy’s supply route from Komiatum to Mubo. The third platoon assumed a defensive role with parties at Base 4, Stephens’ Hut and Wells Junction.

From 4th July the Japanese commanders could not make up their minds about the intentions of their enemy and, in fact, were now dancing to the Australian tune. Orders for the withdrawal of the main Japanese forces in the Mubo area were contained in an order from Araki on 4th July: “Tomorrow, 5th, at sunset, II Battalion (66th Regiment) will leave the battle line and proceed with the utmost dispatch to assemble at Komiatum.” An hour later this order was cancelled “because of the situation” and all units were ordered to carry out their previous duties. This was because Araki thought on 3rd July that the Australians were about to attack from the west, and had decided to withdraw quickly, on 4th July, to guard his vulnerable centre and to prepare defensive positions on the high ground south of Komiatum and Mount Tambu. When no attack came he changed his mind and decided to stay round Mubo, particularly as the activity of Australian patrols on Observation Hill made him conclude that an attack on the Mubo area was imminent. Nakano was so uneasy at the progress of the fighting in the Bobdubi area that he moved from Salamaua on 2nd July to supervise operations personally. It was near Bobdubi that his chief of staff, Colonel Hungo, was killed on 3rd July while inspecting front line defences.

Portion of Matsui’s I/66th Battalion and Jinno’s I/80th Battalion were concentrated about a mile north of Komiatum by 3rd July, ready to attack in the Bobdubi area or defend in the Goodview Junction area. Araki sent portion of these battalions west to seek information about Australian intentions. At 11 a.m. on 6th July Matsui reported that his patrols had seen about 160 enemy and 60 natives on the track towards Wells Junction. A composite force from the two battalions attacked the Australian line at Ambush Knoll and captured the equipment mentioned above.

Meanwhile the three detached forces – the Papuans along the coast, the 24th Battalion in the Markham area, and the 57th/60th Battalion in the valley of the Watut – had been busy.

Hitchcock’s Papuans, who had been skirmishing with the Japanese in the Bassis villages, learnt on 2nd July that they were to move overland from the Tabali Creek area to Salus. Hitchcock, who did not relish the overland movement when water transport was available, set out for MacKechnie’s headquarters where he was successful in persuading MacKechnie to let him move by sea. On 3rd July, however, two attempts to land at Salus from launches failed because of heavy surf. At Hitchcock’s request MacKechnie made four landing barges available, on which the company embarked that day. After a Japanese air attack had caused the company to disembark at Nassau Bay, Lieutenant Gore’s27 platoon was sent forward

to reconnoitre the Salus area. In a skirmish at Lake Salus two men were wounded. Hitchcock then arranged artillery fire on the Japanese and drove them out. Another platoon patrolled along the south arm of the Bitoi and surrounding country, and the remainder of the company moved forward to Duali.

South of the Markham River the 24th Battalion had now clashed five times with the Japanese in the Markham Point area. To deceive the enemy about the actual numbers and activities of the troops opposing them, Captain Duell’s28 company, from 3rd July, sent patrols forward over kunai ridges in view from the north bank of the Markham River in an attempt to make any Japanese and hostile natives observing from north of the Markham believe that a large number of Australians were in the Chivasing crossing area. The relief to Deep Creek would move out over a kunai spur from Oomsis with its boy-line carrying rations, while those relieved would move back to Oomsis by a covered route. On 4th July Duell and Captain Chalk, commanding “B” Company of the Papuan Infantry Battalion, in cooperation with Captain Kyngdon of Angau, decided to tighten security arrangements by allowing no native movement on the south bank of the Markham between the Watut and Markham Point, and no unauthorised native crossing of the Markham. The natives on both sides of the Markham, however, were of the same tribe and they could not really be prevented from crossing if they wanted to do so by swimming or in darkness.

Ever since the success of Corporal Bartley’s patrol to the mouth of the Buang River, Savige had toyed with the idea of establishing there a small force which would lead the Japanese to detach some of their strength from the main effort. The upshot was that on 27th June Major Smith of the 24th Battalion sent forward a platoon under Lieutenant Rayson29 across the valley of the Snake River and along the rugged track through Mapos and Lega to the coast. The patrol, known as “Smoky Force”, was to establish an ambush at the mouth of the Buang and observe Japanese movement between Lae and Salamaua along the beach, firing only on large enemy parties.30

The patrol reached the mouth of the Buang by 29th June.31 Four days later Smith received a message by police boy from Smoky Force that it had seen no Japanese and was mainly concerned with settling in and reconnoitring the banks of the Buang back to the crossing 30 minutes from the beach. According to Rayson’s native guides the Labu natives knew of the Australians’ presence; it was therefore likely that the enemy also knew. On 4th July Smoky Force intercepted on the beach five

natives including an ex-Rabaul police boy who told the Australians of the presence of the enemy in Busama, Bukuap and Kela. In order to gain more information by skilled interrogation Rayson reported to Smith that he was sending the natives back under guard to the Angau representative at Lega. Aware of the danger to Smoky Force if the natives escaped or were released, Smith sent a warning not to let them go, but before this message arrived the natives were released, largely on Angau advice that they were apparently reliable and that the enemy would look for them unless they were let go. By setting free the Lega natives, Smoky Force had almost certainly prepared trouble for itself, even though Japanese activity past the mouth of the Buang was still conspicuous by its absence.

Far to the North-west Lieut-Colonel Marston’s 57th/60th Battalion was gradually assembling in the Watut Valley. Twelve aircraft landed at Tsili Tsili and Marilinan on 1st July carrying battalion headquarters and portions of two companies. Six days later thirty-two aircraft brought to Tsili Tsili an American anti-aircraft battery, a detachment of Australian engineers and more of the 57th/60th. To help in patrolling, a platoon of Chalk’s Papuan company went to the Watut Valley where it came under Marston’s command. By 4th July a Papuan section had established a standing patrol at Pesen.

By 6th July Colonel Araki had come to the conclusion that the main blow was not to be in the Goodview Junction area after all, but that the enemy on the Mubo front was planning an attack. He directed the Mubo garrison to strengthen its defences, and ordered that the two platoons from II/66th Battalion previously sent north to guard the approaches to Goodview Junction be recalled. “All units to leave the present location will thoroughly consider counter-intelligence and burn every scrap of paper or document and must destroy all articles so that they will be of no use to the enemy,” he ordered. This was one of the rare references to security in a captured document.

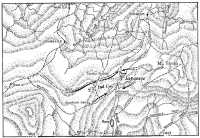

By 6.30 p.m. on 6th July the attacking companies of the 17th Brigade – Captain H. B. S. Gullett’s and Captain H. McB. Stewart’s from the 2/6th Battalion and Captain Morse’s32 from the 2/5th – arrived stealthily at their assembly area at Buiapal Creek ready for the assault on Mubo and Observation Hill. Another company of the 2/6th was on Lababia Ridge and the fourth arrived back at the Saddle on 4th July from its task at Nassau Bay. The remainder of the 2/5th was in areas from which the attack could be readily reinforced. The 17th Brigade was poised and ready to drive the Japanese from the area which they had occupied for so long. From 4 p.m. on 6th July synchronisation of watches began and continued at intervals throughout the night.

The Allied thrust against Mubo really began at 9.30 a.m. on 7th July when Mitchells bombed and strafed Kitchen Creek, Woody Island and the eastern slopes of Observation Hill. They were followed by Liberators and Fortresses bombing Kitchen and Buigap Creeks and Bostons heavily strafing Stony and Kitchen Creeks. An impressive spectacle was watched by the members of Moten’s headquarters from a grandstand seat on

Guadagasal Ridge. The entire Mubo Valley was enveloped in thick smoke broken only by sheets of flame flashing across the valley as the heavy bombers dropped their loads. Most bombs seemed to be in the target area, and, even if the attack did not inflict many casualties on the entrenched enemy, it certainly helped to raise the spirits of the attackers and lower those of the defenders. Approximately 120 aircraft including fighter escorts were in the air over the Mubo area at one time and more than 100 tons of bombs were dropped. The bombing and strafing ceased at 10.40 a.m.

The air attack was the curtain-raiser for the attack by the 17th Brigade. In Colonel Wood’s plan there were two objectives: first was Observation Hill, south of Kitchen Creek and on the general line of Vial’s Track, and second was the high ground between Kitchen and Bui Savella Creeks.

At 8.40 a.m. on 7th July Stewart’s company moved to its start-line south of Observation Hill. Towards the end of the air attack Morse’s company, followed by Gullett’s, moved north to their start-lines. When the end of the air attack was indicated by the dropping of signal flares, the mountain guns opened fire on Observation Hill, their isolated whines and bangs contrasting with the full-throated brazen roar of the bombing raid. After three-quarters of an hour’s firing one of the guns blew up. Thirty minutes before zero hour – midday on 7th July – Morse’s company set off in a North-easterly direction for Vial’s Track. At zero hour Gullett’s men moved west from the attacking companies’ start-line running north and south through a fallen log on the track about 1,000 yards west of the kunai patches on Observation Hill. By 1.40 p.m. Gullett had reached his first objective – the kunai patch on the South-west slopes of Observation Hill – without opposition. Two hours later, when telephone communication was established with Wood’s headquarters, Gullett reported that Morse was also in position about 1,000 yards to his north along Vial’s Track. No opposition had yet been encountered, but by 3.45 p.m. Stewart’s company, which was to capture the southern slopes of Observation Hill after passing through Gullett’s company, was held up 300 yards south of Gullett by heavy automatic and rifle fire. Although Stewart captured one enemy position he was halted by another 40 yards farther south. As the time was now 5.30 p.m., and as he had lost one man killed, one missing and three wounded, Stewart decided to occupy a defensive position for the night. To the north also the enemy had been encountered when, at 4.30 p.m., one of Morse’s patrols ambushed five Japanese. By dusk Savige and Moten considered that a splendid start had been made.

At 7.55 p.m. Stewart was ordered to make a dawn attack on the enemy position. When he held Observation Hill, Gullett’s company would carry out the original plan of securing the high ground between Kitchen and Bui Savella Creeks. At midnight Morse was ordered to send a patrol up Vial’s Track at first light next morning to make contact with the Independent Company.

This patrol set out along Vial’s Track at 5.40 a.m. An hour later Stewart cancelled the dawn attack believing that a frontal attack would

be hopeless and that a flanking attack would be more successful. When Wood learnt that this attack might take three hours he ordered Stewart to keep two platoons on the ridge to guard Gullett’s flank and to find an outflanking approach with the other platoon. Wood then instructed Gullett to wait no longer for the clearing of the ridge but to set out for the high ground between Bui Savella and Kitchen Creeks.

By 8.30 a.m. Gullett’s men were moving through Morse’s position and swinging South-east down the ridge. Three times they were held up by a few riflemen and machine-gunners, but the opposition was rapidly shifted. By 2 p.m. Gullett was sure that he was on his objective. News of the company’s success was eagerly awaited by Savige and Moten, as Gullett’s was the key role in the Mubo attack. Eventually Moten telephoned and passed on Gullett’s report: “I have fetched up with a creek on my right and a creek on my left which I hope to ––– are Kitchen and Bui Savella Creeks.”

While moving towards his objective Gullett had heard firing from the rear. He was anxious about this until Morse sent a message telling him that his company had been skirmishing with an enemy position up Vial’s Track. Morse had attacked and inflicted casualties, but heavy automatic fire prevented him from capturing or outflanking the position.

Between 10.10 a.m. and 11 a.m. 46 Allied aircraft made a bombing and strafing attack, but it was hard for the troops to discover what they were aiming at, and they actually fired on Australian positions. One stick of bombs was dropped on Mat Mat, five Mitchells bombed the mountain-gun positions and made five strafing runs over the area during which one gunner was killed, the bridge over the Bitoi was destroyed, and the carrier lines were disrupted. “It is not understood,” signalled Savige to Herring, “how our request as to type of attack and targets was altered.” Such unfortunate accidents were always likely in this tangled area and it was most improbable that anyone would deliberately alter a bomb-line; the type of aircraft and the missiles to be used were of course the business of the Fifth Air Force.

Stewart was still held up. After mortar fire his company at 2 p.m attacked the stubborn enemy positions. The leading section under Private Moss33 temporarily occupied two posts before withdrawing in the face of a strong encircling counter-attack. The Japanese followed their success by attacking the company’s flanks, but were repulsed. In the day 10 Japanese were killed and 3 Australians wounded. Because of the company’s inability to clear the ridge Wood was forced to use his fourth company (Dexter’s). By 6 p.m. it arrived at Observation Hill and occupied Gullett’s former position.

Out on the right flank in the Lababia area the fifth Australian company in the Mubo line-up had been patrolling the area south of the Pimple. It directed mortar fire on the Japanese positions, and afterwards a patrol found the Japanese still in occupation.

Meanwhile, early on 7th July, Colonel Taylor’s I/162nd Battalion had begun to move forward from Napier on to Bitoi Ridge. Led by Captain George’s company, the Americans crossed the swollen Bitoi using hand ropes. The tracks, prepared mainly by Lieutenant Johnson and Sergeants Hedderman and Gibson, were narrow, rough and winding and so precipitous and slippery that if a man fell he would keep going until stopped by a tree, roots or vines. One platoon with light packs climbed ahead of the main body which spent the first night at the foot of Bitoi Ridge. By 3.15 p.m. on 8th July battalion headquarters with most of Captain George’s and Captain Robert E. Kitchen’s companies had reached the upper southern slopes of the ridge, with patrols forward on the crest.

Many patrol clashes occurred on 9th July as the Australians moved deeper into Japanese territory in fulfilment of Wood’s orders to “worry at” the enemy and to join up with the Americans. Early in the morning four patrols set out on various tasks: one under Lieutenant Trethewie34 to make contact with the enemy between the two creeks, another under Lieutenant Lang35 to join the Americans, a third under Sergeant Ellen to destroy the Japanese near the source of Kitchen Creek along which Wood anticipated that the Japanese facing Stewart would withdraw, and a fourth led by Private Moss to the rear of the enemy position on the ridge. Soon after the departure of these patrols two Japanese scouts disguised as bushes moved up the track towards Gullett’s company. The bushes became stationary when observed and, after being fired at, one became permanently stationary.

Later in the morning Trethewie’s patrol returned after moving about 600 yards towards Kitchen Creek and then encountering 30 Japanese with four machine-guns. In the ensuing skirmish the Japanese first scattered, but later counter-attacked and forced the Australian patrol back. Ellen’s patrol returned at midday after climbing down the steep bank of Kitchen Creek without finding any trace of the enemy. Lang reported that he had reached the Bui Savella and was moving down it towards the Buigap. After midday, Private Moss, now acting as platoon sergeant because of casualties in his platoon, climbed to near the top of Observation Hill behind a Japanese position which he considered was not the one holding up Stewart’s company. At 4 p.m. another runner from Lang reported strong opposition on the high ground in the area at the junction of the Bui Savella and Buigap Creeks. After killing four Japanese, Lang was forced to withdraw.

To the north the Japanese were seriously threatening Morse’s company. Moving south along Vial’s Track they poured in heavy fire and attempted to encircle the company from the west. Pressure continued for an hour and three-quarters until 5.45 p.m. when the firing ceased. As enemy success on Morse’s flank would imperil Gullett’s line of communication, Wood ordered Dexter to send a platoon north to clear that flank. At

6 p.m. the platoon, under the ever-willing Ellen, reinforced Morse. The Japanese attackers at this stage could be heard chopping and digging 40 yards to the north.

During the day artillery had become an important factor in the bitter hide-and-seek fighting. The remaining mountain gun, guided by mortar smoke, fired 40 shells in half an hour on to the stubborn Japanese position on the ridge but failed to shift them. Even more welcome and encouraging sounds for Australians and Americans were those from the American guns which, manhandled forward, had begun intermittent firing on the Pimple and Green Hill on 8th July.36

More inconclusive but intrepid patrol activity followed on 10th July as Wood’s five companies increased their pressure on a stubborn enemy. Patrols from “B” Company, now led by Lieutenant Price37 in place of Gullett38 who had fallen ill with malaria, set out towards the two flanking creeks. One patrol towards Kitchen Creek met the Japanese 100 yards from Price’s position. These were probably the Japanese who on the previous day and also on this morning had attempted unsuccessfully to draw fire from the company. Unfortunately for this enterprising Japanese band the mountain battery’s forward observation officer, Lieutenant Cochrane,39 was travelling with the patrol. Having fired at dawn on the Japanese area north of Morse’s company and the Japanese position reported by Lang at the junction of the Bui Savella and Buigap Creeks, the gun now shelled the Japanese met by the patrol and drew forth many squeals. In the afternoon Price reported that the track to Kitchen Creek was clear.

North-west of Price’s area Morse found no Japanese in his immediate vicinity although signs on Vial’s Track to the north showed that his recent opposition had consisted of an enemy company. At 1.30 p.m. Dexter, in local control on the ridge, sent a platoon of Stewart’s to attack the enemy position to the south. It was immediately pinned down by at least six automatic weapons and the forward scout was killed. In spite of a shoot of 28 mortar bombs on to the Japanese position, the platoon was unable to advance and finally withdrew at 3.15 p.m.

The Americans meanwhile had been drawing closer to the Australians. On 9th July the leading company reached the Bui Kumbul Creek, where Captain George left one platoon astride a track on the high ground between Bui Kumbul and Bui Alang Creeks to cut what was thought to be a

possible enemy escape route from the Buigap Creek area. Lieutenant Marvin B. Noble’s platoon moved down the high ground between the two creeks’ to the Buigap intending to cut the Komiatum Track, while the remainder of the company advanced down the left bank of Bui Kumbul Creek to follow the left bank of the Buigap south to the footbridges and join the Australians attacking from the west. While these platoons were getting into position, Captain Kitchen’s company went to the western tip of Bitoi Ridge where it set up the battalion’s 81-mm mortars. One platoon, stationed on the Bitoi, patrolled south over rough and precipitous country towards Green Hill. By the afternoon of 9th July a third company reached the north side of Bitoi Ridge and the fourth guarded the guns of the 218th Artillery Battalion between Napier and the coast.

Before first light on 10th July Noble’s platoon followed the Komiatum Track South-west until, at dawn, it found 10 Japanese asleep in a hut and killed them all. Continuing along the track the Americans were ambushed by about 70 Japanese. In the ensuing fight Noble lost over half his patrol killed and wounded before withdrawing. As he had no communication with his company commander he decided to move northeast along the Komiatum Track in an endeavour to join his company. At 6 p.m. he ran into what appeared to be the main Japanese defence just north of the junction of Bui Savella and Buigap Creeks. After suffering severe casualties, including Noble and his platoon sergeant, and heavily outnumbered, the remnants of the platoon withdrew to their overnight position. Next morning they moved back to the head of Bui Kumbul Creek now occupied by Captain Newman’s company. This was the first news of the missing platoon since 9th July.

During Noble’s fight patrols from George’s and Kitchen’s companies made contact with one another on 10th July but found no tracks leading up to Bitoi Ridge from the Buigap, although a patrol from Newman’s company found a good track running east along the ridge. Twice during the day George reported sending patrols across the Komiatum Track in an attempt to meet the Australians. All he met was an enemy force near the southern footbridge, and at nightfall he established a strong outpost east of the northern footbridge.

Thus, across the Buigap, American patrols were watching for the Australians who were advancing against stiffer opposition. At 3.30 p.m. on 10th July Price sent out three men to meet the Americans at the southern footbridge, but they returned next day unable to reach their objective because of enemy positions along the Buigap. As reports filtered in from the two Allied forces it appeared to Savige and Moten that the Japanese had no alternative but withdrawal.

Warfe’s Independent Company was already in position in the Komiatum–Goodview Junction area ready to attack any Japanese escaping from the Mubo area. To safeguard Warfe’s flank and to clear a supply route Savige, on 10th July, ordered that an infantry company base be established at Base 4 for patrolling east and North-east, and Morse was given this task.

The next two days, 11th and 12th July, saw the beginning of the triumph of the persistent Australian patrol policy. On 11th July patrols from Wood’s five companies were constantly seeking the enemy. In the area between Bui Savella and Kitchen Creeks, Price’s patrols were very active, particularly towards the footbridges and the Bui Savella–Buigap Creek junction. A patrol to the north footbridge on 11th July was fired on and retired about 400 yards north of the Buigap–Kitchen Creek junction where it was again forced to withdraw by heavy fire from entrenched enemy positions. Forty 3-inch mortar bombs on to the razorback and covering fire from one of Stewart’s sections failed to prevent the Japanese from repulsing an attack by one of Dexter’s platoons on the 11th. From the Lababia area a platoon, split into small patrols, tried to find the Japanese and draw their fire. One patrol actually managed to push into the Pimple clearing before drawing fire.

The enemy force in the Mubo area, disorganised and depleted before 7th July by Araki’s vacillations, fought bitterly to retain Mubo after the Allied attack commenced. Lieutenant Usui’s company of II/66th Battalion consisted of three officers and 87 men at the beginning of July. In the afternoon of 8th July Usui met an Allied patrol “at the three road junctions” and claimed to have repulsed it. Usui reported to his battalion commander at 6 a.m. on 9th July that “the enemy was already on the high ground and they are now being attacked to repel them”. By the end of the day Usui’s strength had decreased to three officers and 72 men. By 10th July the Japanese found that the Allies were astride the Mubo–Komiatum line of retreat, and by 6 p.m. next day the defenders of Mubo were retreating towards Mount Tambu, probably along Bui Kumbul Creek. At this time Usui had only three officers and 46 men left.

In an attempt to capture the stubborn Japanese position holding up Stewart’s company on a razor-back to its south, Captain L. A. Cameron, of the 2/5th Battalion, was ordered to send a patrol from Mat Mat to attack the position from the south. Lieutenant Miles40 led his platoon forward from Mat Mat early on 12th July, but, as he was crossing the Buiapal Creek at Mubo, suffered the unusual misfortune of being accurately bombed by a Japanese reconnaissance plane and lost one man killed and two wounded. After sending back the wounded the patrol began to climb the southern slopes of Observation Hill and successfully brushed aside opposition from a Japanese outpost. Further progress was prevented when the patrol came to the main enemy position which was causing such trouble to the 2/6th Battalion. Although heavy enemy machine-gun fire prevented much movement Miles went forward with the battalion’s mortar sergeant, Robertson,41 and Signalman Turnbull42 with a telephone and wire. Only 50 yards from the enemy position and thus in a very dangerous position from his own ranging fire as well as enemy fire, Robertson directed 3-inch mortar and medium machine-gun fire from Mat Mat upon the Japanese. A slight slip by one Vickers gun actually sprayed the

forward position and wounded Turnbull. As soon as the bombardment finished, Miles’ platoon arose and attacked the formidable position. The Japanese had had enough and fled before the determined advance of the small body of Victorians who completely cleared the area by 4.30 p.m.

Advancing steadily the platoon passed through innumerable defensive positions just abandoned. Three large bullet-riddled and blood-stained huts, hastily-buried corpses, tins of food opened that day, and a good lookout position in a large tree overlooking Mat Mat and the Saddle were passed before the patrol found a big Japanese camp, with accommodation for 700, freshly-cooked food and many bloodstains. Miles saw a path leading North-west, but as it was getting dark and his platoon could not occupy the abandoned Japanese battalion area he withdrew to the position which his platoon had captured. He then reported by telephone to L. A. Cameron who informed Stewart that the Japanese had left Observation Hill and that Miles had apparently dislodged their rearguard.

Events were also moving rapidly in Lieutenant Price’s area on 12th July. Between Bui Savella and Kitchen Creeks his men were keeping up a relentless pressure. At 3 p.m. a runner reported to Price that a patrol under Corporal Martin had reached the junction of the Buigap and Bitoi without opposition and had met an American platoon whose commander, Lieutenant Williams, asked that the Australian company should come forward before he (Williams) crossed the Buigap. Price went forward and he and Williams joined forces and took up positions with two machine-guns commanding the track and the river junction.

South of the Bitoi W. J. Cameron’s patrols were getting closer to the Pimple than the Australians had been before. At 8.30 a.m. on 12th July one platoon moved out to harass the Japanese position south of the Pimple. It probed forward and found 25 pill-boxes and 50 weapon-pits unoccupied. At 5.32 p.m. on 12th July the long campaign of attrition against the Pimple came to an end with its occupation by the forward platoon, led by Sergeant Longmore.43 There was no opposition nor were there any signs of the enemy. Patrols sent forward along a well-defined track to Stony Creek could not make contact; the track to Green Hill had not been used for some time. As a result of the easy capture of the Pimple, Moten informed Taylor that the capture of Green Hill was no longer an American responsibility.

The Americans, meanwhile, were also finding evidence of Japanese withdrawal. Recently-deserted positions had been found near the junction of the Bitoi and Buigap on 10th July. Next day a patrol from George’s company moved across the Buigap between the footbridges to meet the Australians, but again met instead a large enemy force withdrawing to the North-east, and retired across the Buigap at 2.15 p.m. The 81-mm mortars then fired 60 bombs into the enemy. With telephone line now laid to his forward positions, George was able to call down artillery fire also, and it produced loud cries and groans from the bombarded Japanese.

Kitchen now withdrew his platoon from the Bitoi, north of Green Hill, and advanced towards the junction of the Bitoi and the Buigap with the object of destroying any Japanese still remaining there and joining the Australians.

Captain Newman’s company, which had been maintaining outposts on the east and north slopes of Bitoi Ridge, began to march North-west on 11th July, intending to cut the Komiatum Track north of the junction of Buigap and Bui Alang Creeks and reconnoitre towards Mount Tambu. This move was the outcome of a suggestion to Moten by Savige, who thought that the Americans were in a better position than the Australians to advance quickly towards the enemy’s main supply route. The leading platoon camped during the night north of Bui Kumbul Creek with George’s company. Next morning two platoons advanced north but soon ran into a strong enemy force on the ridge between the two creeks. They repulsed attacks until determined Japanese resistance forced them to withdraw to the overnight position. George meanwhile had found the track between the Bui Savella and Bui Talai honeycombed with weapon-pits. During the afternoon his patrols had followed an artillery barrage into the Bui Savella area where they found 40 to 50 Japanese killed by artillery fire. The remainder of the Japanese dispersed in confusion leaving their packs and equipment.

The constant pressure exerted by the attacking companies had its reward on the 13th when all companies advanced. Supported by the mountain battery, two platoons of Price’s company moved south from the junction of the Bitoi and Buigap Creek towards Mat Mat. After reaching Garrison Hill the patrol returned, having found no Japanese although they saw many camps, one capable of holding about 300 troops. Another patrol reported camps “everywhere”. The whole of the Observation Hill area was thoroughly searched without any Japanese being found. By dawn of 14th July the Mubo airstrip had been made ready for small ambulance aircraft, and Green Hill had been occupied.

The Americans arranged for an artillery shoot at 11 a.m. on 13th July at the Japanese occupying the high ground at the head of the Bui Kumbul. After their grim experience of the previous day the Japanese rapidly withdrew after the first few rounds. The Japanese fear of artillery fire enabled Newman’s company to reach the Bui Alang early in the afternoon, when George’s company advanced up the Buigap through abandoned pill-boxes and foxholes. “Literally hundreds of dead Japanese and fresh graves were seen,” said this company’s report. The area from Bui Alang south to the Bitoi was now cleared of organised enemy resistance. During Newman’s and George’s operations it became apparent that the enemy, fearful of using the Komiatum Track because of the Australians’ marauding raids to the north, was using a route via Bui Kumbul Creek to Mount Tambu.

Reports from all the forward fighting units of the 17th Brigade indicated that the enemy had apparently escaped during the night by tracks unknown to the Allied troops in the area. The escape of the Japanese, however,

could not dampen the jubilation of Moten’s message to Savige: “Woody Island clean bowled 0900; Green Hill 1140; Yanks now batting on the Buigap; no further scores to luncheon adjournment.”

Both the Allies and the Japanese were aware that the success of the 17th Brigade round Mubo had been helped greatly by the pressure exerted by the 15th Brigade to the north. The attacks by the 58th/59th Battalion had not been successful in clearing the Japanese from Bobdubi Ridge, but they had caused the enemy commanders to reinforce this area rather than the main Mubo battle area, and had eventually played an important part in causing the withdrawal.

The thorn in the side of the 15th Brigade during the success of the 17th had been Old Vickers Position. Conferring with Starr on 7th July Hammer outlined the battalion’s essential tasks: the capture of Old Vickers, patrolling of the ridge track between it and Orodubi, and control of the Komiatum Track. That day another attack was launched on Old Vickers, after an hour’s bombing and strafing by five Bostons and by mortars. The attack reached within 60 yards of the pill-boxes when it wavered before heavy fire. With one platoon Captain Jago covered the forward move of the other two platoons which had the unpalatable task of attacking up an incline swept by machine-guns tunnelled into the hill and thus not hit during the air strike. This machine-gun fire caused the Australians to withdraw with four casualties.

In the following days there were a few examples of the battalion’s inexperience but, in spite of disappointments, the battalion was learning. On 7th July a platoon from Hilbert’s company which was patrolling the North-west slopes of Old Vickers successfully held its ground against two attacks by 30 to 50 Japanese; on 8th July a patrol from Heward’s company inflicted five casualties at the Graveyard; on 9th July one of Griff’s platoons ambushed a party of about 30 Japanese on the Bench Cut Track north of Erskine Creek and killed nine.

After consultation with Hammer on 9th July, Starr’s plan was that Jago’s company would again attack Old Vickers after an air bombardment, Heward’s and Griff’s companies would attack enemy parties of any size on the Komiatum Track, and the whole battalion would make an all-out effort for the next three days. The attack on Old Vickers again failed. It was a difficult task because the knife-edged saddle had no cover on it and dictated a one-man front. In the two attacks on Old Vickers Position on 7th and 9th July the Australians lost 6 killed and 13 wounded.

Hammer came to the conclusion that when his troops had suffered more casualties they would be more successful. This was a reaction to be expected perhaps from a man who had recently commanded a battalion at El Alamein in a battle conducted on a European scale. He was also making a constant struggle to get accurate information. His signal wires ran hot checking back on what he described as “the most appalling reports”. In the end he resorted to asking a series of set questions. “Times, map references, numbers, directions don’t seem to mean a thing to these people,” he wrote to Savige on 8th July, “but by constant reiteration

we are making them learn.” For their part the officers and men of the 58th/59th thought that the new brigadier had lots of drive but that, at this stage, did not realise the difficulties of the forward troops in the jungle. At brigade headquarters maps were available; in the platoons they often were not.

Many hard things were said about the failure of the 58th/59th Battalion to capture Old Vickers. The battalion was discovering, as the 17th Brigade had done in attacks on the Pimple, how sound were the enemy’s prepared defences. Repeated attacks without adequate preparation or support helped to make the men think that they were facing a hopeless task. They had no artillery, air attacks were insignificant and inaccurate, and mortars and machine-guns had very limited ammunition.44 Nothing was more demoralising to a small band of troops than an order to attack a strongly-defended position when they knew that there was little hope of success.

The attacks on the Old Vickers Position (wrote the historian of the 58th/59th Battalion) suffered from the same faults that so often foredoomed Australian attacks to failure – lack of effective support, insufficient preparation, and the use of too small an attacking force to crack a stronghold capable of resisting a force three or four times as strong. The policy of attacking a company position, first with a section, then with a platoon, then with a company, was costly in that unnecessary casualties were caused with each attack, and the enemy was encouraged by the persistence of the attacks to consolidate his defences. It also had unfortunate effects on morale, since repeated setbacks left the impression that the position was impregnable.45

From 10th July the Japanese showed increased interest in the Erskine Creek area, no doubt engendered by Griff’s recent ambush activity on the Bench Cut and Komiatum Tracks, and their own desire to safeguard their withdrawal from Mubo. The first indication of this interest came

at 9.45 a.m. when the carrier supply line to Griff’s company was ambushed on the Bench Cut Track. The carriers were bringing mail and tobacco as well as rations and ammunition.46 They abandoned their cargoes and with their escorts, one of whom was wounded, fled back along the track. As Griff’s only wireless was returning in the ambushed carrier line, and as the enemy cut the telephone so often that it was impossible to keep it in repair, little accurate information could be passed back to battalion headquarters. A patrol led by Lieutenant Hough47 was sent to salvage the supplies but was ambushed on the Bench Cut near Erskine Creek, suffering 11 casualties, six of whom were missing but later returned. In order to let Starr know what was happening Griff sent out two experienced scouts to find battalion headquarters. They followed compasses on fixed bearing but were unable to get through until next day. Two hours after the ambush one of Heward’s machine-guns on the Bench Cut near Erskine Creek was overrun, apparently by the same Japanese party. The section manning the gun withdrew after killing two Japanese and rendering the gun unserviceable. Having disorganised these two companies the Japanese party now sat down on the Bench Cut north of Erskine Creek. Two of Griff’s platoons were withdrawn from the Bench Cut on 11th July and scrub-bashed their way to Gwaibolom while the third remained on the track north of the Japanese position. A combined attack planned for the two companies failed when faulty communications prevented Gruff from receiving Starr’s orders until too late to put in a coordinated attack with Heward, whose attack was unsuccessful.

The ambush position in the Bench Cut between the two companies had disorganised them and, until it could be removed, Australian operations there would be confused. The leading elements of Griff’s company, moving to attack the ambush position on 12th July, recovered two machine-guns lost on the 10th. Griff found that the belt boxes had been shot through often – obviously during the fighting. He also found the machine-gun sergeant’s body near the gun; the sergeant’s legs were tied together with a webbing strap, apparently splinting the broken leg to the good one, and he had died from exposure or loss of blood.

Starr had now come forward and at 9.30 a.m. on 13th July he and Heward set out to see Gruff. They came to a section posted on the track and asked for Griff. The corporal in charge said that he was away but would soon be back. Starr and Heward and Heward’s orderly went on, thinking that Griff was ahead. The corporal did not mention that his was the forward post. Soon they saw two men a few yards away. Starr called to them thinking they were his own men, but they were Japanese and opened fire. Starr jumped aside and escaped but Heward, who was carrying a copy of Starr’s operation order, was killed.

The 2/3rd Independent Company at Goodview Junction, 8th–10th July

It was a patrol from Jinno’s I/80th Battalion which fired on the three men. The patrol’s report stated: “No. 1 Company ... destroyed an officers’ patrol and captured materials; code book, map, operations order, etc.” The Japanese translation of Starr’s operation order was subsequently recaptured. In it all units of Savige’s force were listed, but the Japanese concluded, probably with dismay, that “the presence of the 6th Division is now certain”.

South of the 58th/59th Battalion, the 2/3rd Independent Company had been moving towards its objective after having driven the Japanese from Ambush Knoll. Determined to cut the Komiatum Track and gain the high ground to the east, Warfe had issued orders on the night 7th–8th July for an attack at dawn by two platoons down Walpole’s and Stephens’ Tracks. Hammer was constantly on the phone, the rain was incessant, and Warfe’s temperature was 104. The adjutant put him to bed under a groundsheet. All were hungry and wet, but at dawn, after a cup of tea and a meal of boiled rice, Winterflood’s platoon advanced down the steep ridge along Walpole’s Track and drove Japanese outposts from positions on Goodview Junction, killing 12 for the loss of one man wounded.

In the afternoon, however, the Japanese struck back; under cover of mortar and machine-gun fire, large numbers of Japanese attacked from both flanks. Twenty-five Japanese were killed but Winterflood found the hastily-dug positions among a thick bed of roots untenable and withdrew 300 yards west up Walpole’s Track.

Captain Meares’ reinforced platoon moving along Stephens’ Track on 8th July unexpectedly encountered strong opposition from a Japanese position in the Tambu Saddle area at the junction of Stephens’ Track and the Mule Track. One section engaged this position while three others bypassed the Japanese to the south and moved across the Mule Track to the Komiatum Track. After engaging another enemy position at the junction of Stephens’ and Komiatum Tracks Meares attacked the first enemy position on the Mule Track from the east and killed 13 Japanese. At dusk he decided to withdraw to a holding position on Stephens’ Track. His scouts had previously seen about 90 Japanese moving to reinforce the positions already encountered at the track junctions, and had heard a great deal of enemy activity on the slopes of Mount Tambu east of the Komiatum–Mubo track.

All this time Lieutenant Egan was harassing the enemy from his impregnable position about 800 yards south of Goodview Junction and overlooking the Buigap gorge. He was actually watching the area where the Mubo–Komiatum-Salamaua track entered and ran along Buigap Creek. On the 8th his men killed 11 Japanese moving north.

Late that day Hammer informed Warfe that possession of the Komiatum Track in the Goodview Junction area was essential to the success of the divisional operation and that all available troops must be thrown into the battle on the 9th. Signallers, cooks and carrier escorts were removed from their regular duties and added to the fighting platoons which at this stage averaged 63 each. The troops were divided into two large attacking patrols. Winterflood’s force consisted of 70 men while Hancock led a composite force of 50, including some sappers and the transport section.

The plans were fine but, as Napoleon and others had found, an army marches on its stomach. On 8th July the forward units had no lunch except some native rice. Aircraft dropped supplies at Selebob and Nunn’s Post that day, but even though Nunn’s Post was a foolproof dropping ground there was still a long carry to the hungry and weary troops. The position was aggravated when, on the night of 8th–9th July, the boy-line from Missim with rations, signalling and medical equipment to replace the losses at Ambush Knoll had been misdirected to Meares’ Creek. Colonel Griffin attempted to remedy the serious situation by sending a line of carriers with rations from Mubo to Base 4 by back tracks. An earlier line of rations from Missim, however, arrived providentially in the afternoon and all troops then had iron rations to last until the 10th.

Winterflood’s men attacked frontally on 9th July but were pinned down by heavy fire, suffering four casualties. It took some time to assemble Hancock’s composite force, which set out at 10 a.m. along Stephens’ Track, across the Mule Track and into the track triangle area. Hancock advanced south parallel to the Komiatum Track but did not reach the vicinity of Goodview Junction until next morning (much too late to support Winterflood) because of the need for caution in the presence of large numbers of Japanese heard immediately east of Goodview Junction and Tambu Saddle. Twenty-four hours after setting out Hancock came

across a party of Japanese digging in on the west side of the Komiatum Track at the southern corner of the track triangle. The Australians killed eight and dispersed the remainder, but as no rations were being carried because there were none to carry, action against the enemy east of the Komiatum–Mubo track could not be pursued. By dusk Winterflood’s and Hancock’s forces were holding positions on Walpole’s and Stephens’ Tracks respectively.

The plan for the Independent Company had been to harass the unprotected enemy supply line between Komiatum and Mubo. Instead, it now appeared that they had struck the considerable strength of the west flank of the Japanese defences on Mount Tambu, and there were indications that the Japanese might be using another supply route farther east. There was no movement either north or south along the Komiatum Track until 12th July when a party of 16 heavily camouflaged Japanese, moving stealthily from Goodview towards Mubo, was attacked, 14 being killed.

Sounds of chopping and digging from the Japanese positions as well as the fact that all Japanese encountered had been well clothed, well fed and lightly burdened, made it apparent that the enemy had a large fresh force available in the Mount Tambu area. The Americans had proved that the enemy escaping from Mubo were using a new route up Bui Kumbul Creek to Mount Tambu. By mid-July it was clear that, instead of hunting fleeing bands of enemy escaping from the south, the Independent Company was up against a new and powerful force well established to the east.

This force consisted mainly of Matsui’s I/66th Battalion, which had been withdrawn from Mubo before Moten’s attack was launched, and later the remnants of II/66th Battalion which escaped from Mubo after 7th July.

The northern unit of Hammer’s force was Captain Whitelaw’s company of the 24th Battalion in the Cissembob–Hote area. Its tasks as formulated by Hammer on 8th July were to defend that area as a base for operations against Salamaua, and establish control of the Hote–Malolo track. This was an enlargement of its previous role of establishing a defensive position on the left flank of Warfe’s company and protection of the Missim supply route. The specific task of preventing the enemy approaching from Malolo was relatively simple for determined troops as the country was wild and rugged and ideal for defence.

It was troops from the 115th Regiment who had attacked the Australians at Cissembob in May, before being withdrawn to the Heath’s, Markham Point or Lae areas by the beginning of July. On 2nd July General Muroya ordered the commander of 102nd Regiment “to furnish a platoon immediately, the main part of which will occupy the heights about 3 kilometres North-east of Hote”.

During the operations early in July Savige’s staff thought that Hammer, fresh from desert warfare, except for three months’ training on the Atherton Tableland, was unduly worried about the insecurity of his flanks. On the other hand Hammer’s front extended from Goodview Junction in the south to the Francisco River in the north and then through a gap of

unoccupied country to Hote farther north. His troops were very thinly spread and with only one battalion and a quarter and an Independent Company available, his concern was understandable. The possibility of encirclement of his northern flank from the Buiris Creek area at the beginning of July had delayed the move of Warfe’s company south. Enemy thrusts into the middle of the brigade area, which disorganised portion of the 58th/59th Battalion, underlined the two-mile gap between the southern area held by the 58th/59th Battalion at Namling and the Goodview Junction area for which the 2/3rd Independent Company was fighting. It would be possible for the enemy to drive a wedge into this gap and threaten the Base 3 and Uliap Creek supply routes. Hammer therefore telephoned Colonel Wilton on 11th July and asked that Warfe’s company be relieved from Goodview Junction in order to fill the gap between Wells OP and Base 4 and to strengthen Starr’s southern flank at Namling and Orodubi.48 Savige and Wilton considered that gaps and lack of a continuous line must be accepted as a concomitant of jungle and mountain warfare, but in this case they agreed with Hammer that the gaps were unduly large and the dangers to the supply routes too acute.

By 10th July Colonel Conroy had already received orders for the movement north of two companies of the 2/5th Battalion, so that Wilton was able to inform Hammer that these would relieve Warfe’s company which could then protect the southern flank of the brigade. Captain A. C. Bennett’s company was sent north to join Captain Morse’s at Base 4 on 13th July. The two companies, known as “Bennett Force”, took over from the Independent Company on 14th July. Bennett was instructed to secure the Goodview area, prevent the Japanese escaping from Mubo, protect the line of communication to Base 4, patrol vigorously north to Komiatum, make and retain contact with the Japanese in that area, and patrol northeast to Mount Tambu. The remainder of the 2/5th moved up the Buigap as far as Bui Alang Creek on 14th July.

It will be recalled that the Papuan company at Nassau Bay had begun to move north into the Duali and Salus areas on 6th July. Next day Hitchcock received a message from MacKechnie to “move north sending out patrols east of Salus to mop up enemy” – a difficult task since to the east of Salus lay the sea; and to find suitable landing places for barges at Tambu Bay and Dot Inlet. In its progress north the company unearthed a Japanese machine-gun hastily buried in the sand near the mouth of the north arm of the Bitoi, and on 8th July a patrol from Lieutenant Bishop’s platoon moving west along the Bitoi captured one badly wounded prisoner a mile from the coast.