Chapter 7: The Fight for Komiatum

ALTHOUGH there seemed little chance of the Japanese seizing the initiative again in the Salamaua campaign they were defending their natural fortresses stubbornly. By costly and frustrating experience the Australians had learnt that it was easy enough to pin the enemy down but quite another problem to shift them, and that frontal attacks on high features like Mount Tambu were unprofitable. The Australians had also realised that to surround an enemy force did not mean its extermination because small parties could filter through gaps in the positions occupied by the besiegers who could not possibly maintain a continuous line in the dense jungle. Severing the various lines of communication, however, did lead to disorganisation of the defenders and would probably cause their withdrawal and the abandonment of equipment.

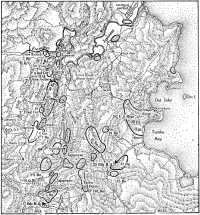

By early August plans were already well advanced for the encirclement of Komiatum and Mount Tambu. In order to achieve Brigadier Moten’s intention to place the 2/6th Battalion on Komiatum Ridge north of Mount Tambu and thereby to cut the main Salamaua–Komiatum track, patrols from the 17th Brigade were seeking the most suitable route to Komiatum Ridge. Moten realised that he must block not only Komiatum Ridge but also the other two ridges which led north and North-east from Mount Tambu. On the northern ridge – Davidson Ridge – he intended to use a company of the 2/5th Battalion and he hoped that Coane Force which was responsible for blocking the North-eastern ridge – Scout Ridge – would in fact do so.

On 6th August General Savige walked to Moten’s headquarters on the Bui Eo Creek. He agreed with Moten’s tentative plans but told him that the incoming battalion from the 29th Brigade could be used on Davidson Ridge in place of the company from the 2/5th. Moten’s pleasure at this unexpected addition to his fighting strength was increased when Savige gave him the first call on Colonel Jackson’s Allied artillery. Moten said that he would require 10 days’ reconnaissance before the attack could begin. Savige returned that night up the steep track to Guadagasal and issued an outline plan by which Komiatum Ridge would be secured and Mount Tambu isolated by an encircling movement of the 17th Brigade, Davidson Ridge occupied by the new battalion, and Roosevelt Ridge secured by Coane Force before the attack on Komiatum Ridge. The 15th Brigade would support the 17th by “offensive operations within their area”.

A letter from Herring to Savige written on the 4th was carried by Colonel MacKechnie who had been at Herring’s headquarters. In the course of it Herring wrote about the role of the new battalion and said that the use which Savige planned for it “would appear to make possible the further development of a line of communication from Tambu Bay. Its presence in the area should encourage Coane to make sure of getting Roosevelt Ridge, control of which is vital really to such line of

communication and also to the proper deployment and effective use of your guns.” Herring then urged Savige to “drive Coane on to the capture of Roosevelt Ridge even if the cost is higher than he cares about”, adding:

The question is whether you want me to make representations to higher authority with regard to any or all of the personalities concerned.

In his reply, on 7th August, Savige requested that Coane and Major Roosevelt be relieved. Savige now had confidence in MacKechnie if his health remained good, and also in the American “Executive Officer” – now Lieut-Colonel Harold G. Maison. On the 8th Savige sent a signal to Coane stating: “Our early occupation and control of Roosevelt Ridge of utmost importance irrespective of difficulties in achieving this vital objective ... you will plan for this operation forthwith.” He emphasised that the incoming battalion was not available for the attack on Roosevelt Ridge.

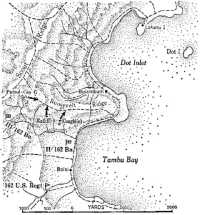

The 42nd Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Davidson1) was the one chosen from the 29th Brigade to move to Tambu Bay, and on 6th August the first flight of that battalion with a company of the 15th Battalion left Morobe for Nassau Bay in American barges. Already Captain Leu’s2 company of the 15th had moved from Morobe to Nassau Bay to relieve the remaining company of II/162nd Battalion, and by 6th August had moved to the Tambu Bay area where it took up a position on the left flank of the III/162nd Battalion on Scout Ridge.

After landing at Nassau Bay the men of the 42nd had a hot meal and a sleep, and began moving north at 1 p.m. Major Hodgman,3 one of Savige’s staff officers whom Colonel Wilton had sent hot foot to intercept the 42nd, was sitting on the track with his runner near the south arm of the Bitoi when the battalion came in sight. He informed Davidson that the battalion was on Coane’s ration strength but under Moten for operations. Seeing the possibility of misunderstanding, Davidson asked Hodgman to suggest that the position be made clear to Coane.

On the way to Tambu Bay the 42nd passed Coane’s headquarters at Salus. The meeting between Coane and Davidson at noon on the 8th was not over-cordial.4 Coane had planned to use the Australian battalion to assist in the assault on Roosevelt Ridge. In justification of this he had Savige’s signal of 1st August stating that the battalion “will be placed under your operational control”. Savige, however, had undoubtedly been influenced by a portion of Herring’s letter of the 4th which said: “I do not like putting the battalion under Coane in view of the stickiness which has been apparent in his command. Stickiness as you know is something that is catching especially by troops who haven’t yet been engaged in battle.” He had therefore sent Coane a signal at 11.55 a.m. on the 8th

stating that “troops of 29th Aust Inf Bde are not repeat not available to you for operational purposes”. Because he was moving his headquarters forward to Tambu Bay at this time Coane did not receive this signal, and another similar one sent late that night, until the next day. Savige had to send two more signals on the 9th requesting an acknowledgment of the change in orders before he heard anything from Coane who, even late on the 9th, had not received any of Savige’s signals. Coane at length replied to Savige’s several signals on 9th August that he would do everything possible to accomplish his mission, but because all high points on Roosevelt Ridge were heavily fortified each one would have to be taken in turn by coordinated artillery and infantry attack and this would be a slow process. However, he did intend to attack one strongpoint on 11th August if the 42nd Battalion was then in position to protect the left flank.

Marching overland and also conveyed by barge the 42nd Battalion arrived at Boisi on 10th August. On 9th August Moten placed a company of the 15th Battalion under Davidson’s command, and also one medium machine-gun platoon and one infantry company of the 2/5th (Captain Cameron’s) to assist the 42nd “in patrol activities, defensive preparations and the routine matters which troops usually acquire in the bitter school of practical experience”. He emphasised that occupation of the ridge due north of Mount Tambu must be done secretly and defensive preparations carefully concealed and camouflaged. No patrolling was to proceed farther west than Buiwarfe Creek.5 Aggressive action would be taken by offensive patrolling. With this letter came a copy of Moten’s operation instruction of the same date, from which Davidson learnt that his battalion would defend “ridge east of Komiatum Ridge and line of communication Mount Tambu to Boisi”.

At 3 p.m. on the 10th Davidson learnt that it was essential for his forward companies to be on the vital Davidson Ridge by the morning of 11th August. At dawn on the 11th the battalion was on the move. The climb from Boisi to the summit of Scout Ridge was a hard introduction to the battle area. Davidson ordered his troops to “travel light” with the result that tin hats and respirators were discarded, blankets and towels were cut in halves and all extra clothes (except a pullover and socks) were dumped;6 the men’s packs were still heavy because three days’ rations were carried. By 12th August the battalion was dug in with two companies near the junction of Davidson and Scout Ridges, and two on Davidson Ridge.

Opposite Moten in the Mount Tambu–Goodview Junction–Komiatum area Colonel Araki, the commander of the 66th Regiment, was dissatisfied with two of his battalion commanders. Early in August he relieved Lieut-Colonel Matsui and Major Kimura of their commands of I and III Battalions respectively; their places were taken by Captain Numada (I/66th Battalion) and Captain Okamoto (III/66th Battalion) both from Eighth Area Army Headquarters at Rabaul. By 8th August the III/238th Battalion of the 41st Division had landed at Salamaua from small craft,

a month after leaving Wewak. Thus the 51st Division had now been reinforced with one battalion of the 20th Division (I/80th) and one of the 41st.

“I am terribly anxious to ease the air commitment as quickly as possible,” wrote Herring to Savige early in August, “and I know you will do all you can in this regard. Plans for future operations are proceeding and I hope they will be able to get under way on time. Meanwhile you are assisting mightily by drawing reinforcements into your area.” The only alternative to air dropping was the development of a supply route from Tambu Bay to the battle area, and this was becoming more and more a vital necessity as the air force began to concentrate on its task in the rapidly approaching offensive.

The plan for the big offensive in the Lae–Markham Valley area was issued to the relevant commanders on 9th August in the form of an operation order. The intention was that New Guinea Force in conjunction with the Fifth Air Force and US Naval Task Force 76 would seize the Lae–Nadzab area with a view to establishing airfields. Savige found the tasks of the 3rd Division listed under “subsidiary operations”. He would continue operations for the capture of Salamaua, patrol in the Markham area, and transfer control of the Watut Valley to the 7th Division at a time to be notified.

On 9th August Savige signalled Herring that he was anxiously awaiting a reply to his signal about Coane. Herring discussed the problem with General Sutherland, MacArthur’s Chief of Staff, and next day Herring signalled MacArthur “now that guns under central control with Jackson as CRA Coane merely sits as an extra link between Savige and Maison who virtually commands 162nd US Regiment less one battalion”. Herring continued that this was most unsatisfactory and dangerous, and that he endorsed a request from Savige that MacKechnie relieve Coane. He emphasised that “new commander should feel completely free from all control 41 US Div in operational matters”.

At Savige’s headquarters Colonel Jackson heard rumours of possible changes. “Say, General, that’s highly political and mighty explosive,” he said. The situation did indeed have such possibilities, but MacArthur supported the Australian leaders, and ordered that Coane should report to General Fuller at Rockhampton to resume his normal duties, and MacKechnie should resume command of the 162nd Regiment, which would be detached from the 41st Division and henceforth be under operational control of New Guinea Force.7

The capture of Roosevelt Ridge, 13th August

Savige’s plan for the encirclement and capture of the Komiatum–Mount Tambu–Goodview Junction area involved movement on the entire divisional front. First move would be made by the Americans on 13th August – the capture of Roosevelt Ridge. On D-day the 17th Brigade would capture the Komiatum–Mount Tambu–Goodview Junction area, and next day the 15th Brigade would attack the Erskine Creek area and advance east to the Komiatum Track to prevent enemy movement north or south along the track.

Since the failure of the attack on Roosevelt Ridge at the beginning of August the II and III Battalions of the 162nd Regiment, assisted by the Papuan company, had been observing and patrolling south and west of Roosevelt Ridge. The II/162nd Battalion was clinging to positions on the southern slopes of Roosevelt Ridge and the III/162nd Battalion was on the eastern slopes of Scout Ridge about 500 yards from the ridge junction. Patrols found plenty of evidence that the Japanese were extending their defences. An observation patrol post near the western end of Roosevelt Ridge saw an officer wearing white gloves visit the Japanese lines at the ridge junction. The Japanese came to attention at his approach, and thereafter increased the number of barricades in front of their positions. Another patrol from Scout Ridge found the Japanese building more machine-gun pill-boxes near the ridge junction.

On 12th August Lieut-Colonel Maison issued orders for the attack on Roosevelt Ridge: the II Battalion, under Major Lowe, on the right flank would make “the main effort”, while the III Battalion on the left, now under Major Jack E. Morris, who had replaced Roosevelt, would support II Battalion. On gaining the crest of the ridge the Americans would exploit to the east and North-west

to its junction with main Scout Ridge. Zero hour would be 9 a.m. on 13th August.

A preliminary move began on 12th August when a patrol from the II Battalion penetrated enemy defences on Roosevelt Ridge and established an outpost position on the crest of the ridge about 2,000 yards northwest from Boisi. Between 6 p.m. on 12th August and 8 a.m. next day

the enemy made several attacks from the west, but the Americans clung to their position.

At 7 a.m. on 13th August the artillery opened on the enemy positions in front of the attacking companies of the II Battalion (Captain Coughlin’s on the right and Captain Ratliff’s on the left). Two hours later it shifted to the right and left flanks of these companies. Ratliff’s company then made the main attack on the left towards the enemy position on the crest east of the ridge junction, while Coughlin’s company made a diversionary attack towards the next high ground to the east. Soon after the attack started the men in the outpost attacked the enemy opposing Ratliff’s company and assisted it to reach the crest of the ridge. Boxed in on the flanks by the artillery barrage both companies reached their objectives. Enemy opposition during the attacks came from bunkers and well dug in but isolated positions. By nightfall the two companies were occupying high knolls about 500 yards apart and commanding a small Japanese force on a knoll between them. Coughlin’s company was about 800 yards from the coast, and the enemy were still occupying the North-west position of the ridge from Ratliff’s position to the ridge junction. During the day 39 Japanese were killed, and there were 25 American casualties. The Americans’ success on 13th August delighted Savige who sent his congratulations to MacKechnie and all commanders and troops who participated. The first day of the resumption of his command was indeed an auspicious one for MacKechnie.

The Japanese in the Roosevelt Ridge–Scout Ridge area were worried by this American success. At Salamaua General Nakano’s commander of the defence of Salamaua itself, Ikeda, wrote: “The enemy on the Boisi front have for some days been active and on the 13th finally seized our artillery positions. The army force has withdrawn. ... The navy mountain gun unit has become the front line.”

The two American companies found early on the 14th that the Japanese had withdrawn from the knoll between them during the night. Preceded by heavy fire from the supporting weapons Coughlin was able to advance 300 yards east and seize the next high ground after a 20-minute advance without opposition. At the same time Ratliff was advancing through a hastily evacuated Japanese position to the North-west. By midday the II/162nd Battalion held about 1,100 yards of Roosevelt Ridge, leaving about 500 yards of the east end still in enemy hands and the situation to the North-west unknown.

Early in the afternoon Captain Vernon F. Townsend’s and Captain Coughlin’s companies, preceded by withering supporting fire, reached the eastern end of Roosevelt Ridge with little opposition. By 3 p.m. the battalion controlled all Roosevelt Ridge from the sea inland to Ratliff’s forward patrol, still advancing to the North-west about 2,000 yards inland from the seaward end of Roosevelt Ridge. This patrol was forced to halt at 4 p.m. by what MacKechnie’s sitrep termed “extreme over-extension”. While it was digging in it reported that the enemy was in a position about 200 yards farther up the ridge. Captain Colvert’s company from the III/162nd Battalion was then sent to hold the position gained by the

patrol, but after a short advance was pinned down by heavy fire and at 5.30 p.m. dug in for the night.

A day of triumph for the Americans, particularly the II/162nd Battalion, saw the capture of Roosevelt Ridge and the killing of about 120 Japanese, mainly by fire from supporting weapons. An accurate count, however, could never be made as many Japanese had perished in the holes, tunnels and underground caves which the artillery and other supporting weapons had blasted. The stench from the whole area was terrible. A feature of the attack had been the use made of the Bofors anti-aircraft guns in the Boisi area during the infantry’s approach march before the attack. The guns had poured accurate and sustained fire on the enemy positions and had proved most effective against pill-boxes.

At about 1315 (wrote the 41st Division’s historian) the jungles north, south and west of Roosevelt Ridge shook and shivered to the sustained blast. The mountains and ridges threw the echo back and forth, down and out, and the quiet white-capped sea to the east, ringing the outer third of Roosevelt Ridge, grew dark as it received the eruption of earth and steel on that stricken shoulder of land. Scores of guns-75-mm howitzers, Aussie 25-pounders, 20-mms, Bofors, light and heavy machine-guns, even small arms – had opened up simultaneously on the enemy-held ridge. A score or more Allied fighters and bombers had swooped low to strafe its dome and tons of bombs released from the B-24’s and B-25’s fell straight and true, to detonate, shatter, rip and tear and to deliver certain death at that moment on an August afternoon. Those who watched from the beach saw the top fourth of the ridge lift perceptibly into the air and then fall into the waiting sea. In a scant twenty minutes all that remained of the objective was a denuded, redly scarred hill over which infantrymen already were clambering, destroying what remained of a battered and stunned enemy.8

On 15th August MacKechnie reported to Savige that he would try to capture the ridge junction, but did not consider an advance north or west possible or advisable until the third battalion rejoined the regiment; the effective fighting strength of his two battalions was 55 officers and 620 men with an average daily evacuation of 26. Savige agreed and on 15th August ordered that the present American positions should be held and the forces regrouped to place one company in reserve. To MacKechnie he wrote:

I have implicit faith in your judgment as well as that of Maison and Taylor. I hope, and believe, that we shall push the Jap beyond Komiatum within a few days. This will give you Taylor Battalion for your command and will achieve my aim in placing all US troops under American command which you know is my desire. Keep contact with 42 Aust Bn on your left flank.

For the success of the attack on Mount Tambu much depended on the patrols of the 17th Brigade to Komiatum Ridge. From patrol reports and interrogations of native carriers recently deserted from the enemy Moten deduced that the Japanese were in the habit of supplying their Mount Tambu defences every third day. He hoped that, if he could block this supply route, the Japanese position would become desperate by the

third day and force them to abandon their defences. He would therefore try to hem in the Japanese on Mount Tambu on the day when their rations arrived, give his troops time to consolidate, and then expect the hungry Japanese to break out on the third day.

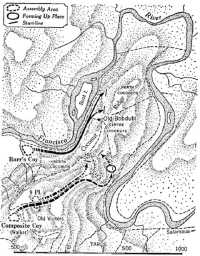

Much reconnaissance, however, had to be carried out before the dim outlines of the plan could be filled in. As mentioned, two three-man patrols from the 2/6th Battalion led by Sergeant Hedderman and Lieutenant Johnson had set out on the 5th. Hedderman’s patrol had returned at 2 p.m. on 7th August having moved east from Coconuts9 and across the Komiatum Track about 600 yards south of Komiatum, where the men spent a day observing a large amount of enemy movement. Hedder-man reported that the country was very rugged and steep but not impassable. Johnson’s patrol returned at 4 p.m. next day having reached the Komiatum Track near the old village of Komiatum about 250 yards north of the junction of the Komiatum and Mount Tambu Tracks. After crossing very rough and dense country, which he also reported was passable, Johnson found two positions suitable for occupation by troops: one an open kunai knoll, commanding the Mule Track and capable of accommodating two companies, and another, commanding the Komiatum Track, capable of accommodating a battalion. On his second day out Johnson had been ambushed on a spur to the west of the Mule Track but had escaped without casualties. Like Hedderman he reported much enemy movement. Komiatum Ridge near the old village had been bared by bombing, and thus had fields of fire already cleared. Savige now resolved to see the country for himself and discuss plans with his local commanders. He spent the night of 9th–10th August at Moten’s headquarters, and on the 10th the two commanders viewed the country from every vantage point on their way to meet Wood at Drake’s OP. There Wood told them of the difficulties encountered by his patrols in negotiating the gorge of the Buirali – only 1,200 yards wide as the bullet flies, but patrols setting out east finished up at all points of the compass. Wood sent for Captain Laver whose company was responsible for the patrolling. Laver explained on the ground just what his difficulties were but was hopeful that the tireless Hedderman would find a better route. Savige arranged to meet Wood at the same spot on his way back from the 15th Brigade’s area in two days.

On 11th August Hedderman and the battalion Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Marsden,10 left to make a thorough reconnaissance of the Coconuts area which had been finally selected as a suitable supply base and assembly area for the forthcoming operation. Next morning seven men from Laver’s company at Drake’s OP cut a track from the company area to the Coconuts, and the first carrier line went forward. That afternoon Hedder-man set out yet again, to define more clearly the route from Coconuts to

the area on Komiatum Ridge selected for occupation, known as Laver’s Knoll.11

Moten’s other three battalions were also busy patrolling and skirmishing. On 7th August the enemy had driven back the forward platoon of the 2/5th on Walpole’s Track, but after an accurate mortar bombardment the position was reoccupied. The I/162nd Battalion was harassing enemy supply routes to Mount Tambu from the coast, preparing ambushes at known water points and mortaring enemy positions. The 42nd Battalion on Davidson and Scout Ridges exchanged its first shots with the enemy on 12th August.

Conditions on these ridges were worse than the troops of the 42nd had imagined. Lack of sleep and patrolling in enemy territory were new experiences. Water was scarce and at least half an hour away from each com-pany – a normal problem for troops occupying ridges and knolls. It was more than a week before the battalion received rations in sufficient quantities to be barely adequate. The troops’ thoughts turned continually towards food and their hunger was not alleviated by stories of steak and eggs being taken to the Americans on Roosevelt Ridge or by stories from Boisi about fresh potatoes, fruit, fruit juices and other tasties which the Americans were said to be enjoying there. After the first week a little tea, sugar, milk, margarine and jam arrived.

Early on the morning of 12th August an Australian sergeant in charge of a party of natives working for the I/162nd Battalion reported that one of his natives had noticed a fresh track crossing the track from Boisi to Mount Tambu on the lower eastern slope of Scout Ridge. A small patrol followed the new track to the south and South-east and saw a Japanese force which it estimated as a company, with weapons, full equipment and camouflage, moving along the track. Colonel Taylor then sent Lieutenant Messec and his platoon to follow the enemy force, which seemed to be making for Bitoi Ridge. Their experiences will be described later.

On the left flank the 15th Brigade was getting what rest it could. The 58th/59th Battalion and the 2/3rd Independent Company certainly needed a spell but they were lasting better than their enemy – the I/80th Battalion, parts of the 66th and 115th Regiments and some marines. Long service in the tropics had sapped the fighting spirits of such units as the 115th Regiment, but even in the more recently arrived units disillusionment was apparent. Captured diaries indicated that the Japanese soldiers now doubted their invincibility. They complained of the food, the rain, malaria, bombing and their hopeless position. A private of the I/80th Battalion wrote:

The only Unit Commander remaining went forward but no word from him in a week. We don’t know whether he is dead or alive. Two section leaders, corporals,

were both killed. We are on half rations. After twilight we cover the trench so no light can show and cook our food. We eat in pitch darkness and don’t know what we are eating. It’s all gritty.

Patrols from the 15th Brigade probed the Japanese areas from 7th August. There were several skirmishes but patrolling, mainly defensive, was not Hammer’s idea of winning the war. He planned to drive the enemy from Bobdubi Ridge and then harass the Komiatum Track. He considered that his first tactical move would be the capture of the Coconuts followed by the capture of the Salamaua–Bobdubi and Komiatum Track junctions. Then would come the capture of Kunai Spur south of the Francisco and of important features north of the river. On 9th August Hammer called his commanding officers together and issued his orders for the capture of the Coconuts and the track junctions. He had not then received Savige’s order of 9th August that the 15th Brigade would attack the Erskine Creek area and exploit east to the Komiatum Track.

At Dierke’s OP on the 10th Hammer met Savige and outlined his dispositions and plans. He pointed out that a successful attack would secure the north flank of the divisional area and release troops for operations elsewhere on the brigade front. Savige, however, considered that active operations in the Erskine Creek–Komiatum Track area on the day before the 17th Brigade’s attack on Mount Tambu would help Moten in his difficult operations. Hammer stuck to his guns and pointed out the difficulties, largely of terrain, which would be caused by any regrouping to deliver his main attack in the Erskine Creek area. He doubted the physical possibility of regrouping in the south in the time available and considered that Savige’s requirements would be met by the capture of the Coconuts and subsequent exploitation to the Komiatum–Salamaua–Bobdubi track junctions.

Savige heeded the brigadier and deferred his decision until 11th August after he had completed a reconnaissance from Ambush Knoll and Mortar Knoll. Finally he decided that any regrouping of Hammer’s units might result in a half-cocked attack on the southern flank, whereas there was every chance of success on the north. He approved Hammer’s plan for an attack on the Coconuts two days before Moten’s attack, provided some pressure was applied to the Erskine Creek area not later than two days after Moten launched his attack.

This trip by Savige into the forward area was an arduous one for a man of 53. He had undertaken it not only to see the country for himself but also to renew his acquaintance with his old brigade – the 17th – and to have a close look at the 15th Brigade, particularly the 58th/59th Battalion about which he had received so many critical reports. The sight of the well-loved general toiling along the rugged tracks with his pack up and observing the battle area from the forward observation posts gave a great boost to the spirits of the men. As he moved through the units tin pannikins of tea were offered in such numbers that he could drink no more. He was pleased with the appearance of the 58th/59th, of which he was Honorary Colonel, and told them of the great value of their

effort. “When I met Wood on my return journey next day, the 12th,” wrote Savige later, “he had a grin on his face like a Cheshire cat and I knew he had taken the trick. He then informed me that the way had been found, the route had been blazed, and work had started on cutting a track along which to carry stores to the start-line.”

As the result of the excellent work performed by his patrols Moten was able to issue his orders on 12th August: the 17th Brigade would drive the enemy north of the general line Davidson Ridge–Komiatum-Ambush Knoll; D-day would be 15th August (but was subsequently changed to 16th August). The 17th Brigade would encircle and destroy their enemy by capturing Komiatum Ridge, and at the same time maintaining a constant pressure on the enemy from the south and holding Davidson Ridge. Moten hoped by these means to cut the enemy’s line of communication and thus prevent his supply, reinforcement or escape.

The main task of attacking and capturing the south end of Komiatum Ridge was allotted to the 2/6th. The 42nd Battalion, assisted by companies from the 2/5th and the 15th, would hold Davidson Ridge, prevent the enemy being reinforced or supplied from the east, support the 2/6th with machine-gun fire, and protect the track from Boisi to Mount Tambu. The I/162nd Battalion would harass the enemy on Mount Tambu and, “at the appropriate time”, destroy them. The 2/5th would also harass the enemy and would attack and destroy them in the Goodview Junction area “at the appropriate time when the enemy is weakened by encirclement”. One company (from the 2/7th Battalion) would contain the enemy in the Orodubi area.

Hammer, on 11th August, issued his final orders for the attack on the Coconuts on 14th August, and the Salamaua–Bobdubi–Komiatum track junctions two days later. To precede the attack he requested an hour and a half of heavy bombing, which would be supplemented by 600 rounds from the Australian 25-pounders, 600 mortar bombs and eight belts each for six machine-guns. Captain Barr’s company of the 2/7th Battalion – a total of 88 men – would attack North Coconuts from the west; a composite company of 60 men led by Major Walker would attack South Coconuts from the east and south; and Lieutenant Lewin’s platoon of the 2/3rd Independent Company – now reinforced to 47 men – would cut the enemy line of communication along the Salamaua–Bobdubi track and prevent reinforcement or withdrawal.

Barr and his platoon commanders on 12th August climbed unobserved almost into North Coconuts and were able to form their plan for the attack with simplicity. To the south Captain Rooke,12 on a stealthy patrol, found a track which led him and his section leaders to within 10 yards of the enemy positions on the Coconuts. At a conference with his commanders on 13th August Major Picken estimated that not more than an enemy cothpany was holding Coconut Ridge.

At 9.20 a.m. on 14th August nine Liberators began circling Coconut Ridge. The artillery immediately began registering the targets and 10

The 2/7th Battalion’s attack on Coconuts, 14th August

minutes later the first three Liberator aircraft released their bombs. These bombs, accurately dropped by the Liberators which were soon joined by 13 more Liberators and 7 Fortresses, had an annihilating effect. Through the dust which cloaked the ridge, trees, logs and rubbish could be seen erupting into the air. As the big bombers droned away an ominous report to the effect that 100 Japanese were standing to in South Coconuts, was received from an observation post.

Forty minutes after the beginning of the aerial bombardment, the artillery, mortars and machine-guns began to plaster Coconut Ridge to cover the forward move of the attacking troops who, during the air strike, had been 600 yards from the ridge. At 11.40 a.m. the artillery switched to the area of the Salamaua–Bobdubi–Komiatum track junctions. Under cover of well-laid mortar smoke, Barr’s company formed up with two platoons forward. Ahead, Barr found that the air strike had blown away all cover and previously reconnoitred lines of approach. The slope was now a cliff face of loose earth and rubble up which the troops had to crawl on hands and knees. The leadership of Barr and his platoon commanders and the determination of their men enabled the two platoons to reach the crest of the ridge at the positions previously planned. Sharp fighting ensued before they finally cleared out the Japanese by 2.45 p.m. The position captured consisted of two pill-boxes connected to weapon-pits by an intricate system of underground crawl trenches. Enemy fire from South Coconuts which had not yet been captured was responsible for most of the Australian casualties. Barr, moving throughout the action with his forward platoon, was mortally wounded by this fire. Lieutenant Walker13 and Sergeant Tennant14 were killed: Lieutenant Fietz

then took command and continued mopping up and exploiting to Centre Coconuts where most of the defenders had been buried by the air strike.

Meanwhile Major Walker’s force had been unsuccessful. Rooke’s platoon approached from the east, struggling over a mass of branches and trees smashed by the bombardment. When below South Coconuts it came under heavy machine-gun fire from three machine-guns only a few yards away. Rooke sent the left forward section led by Corporal Berry.15 round the left flank. It advanced up the steep slope swept by very heavy enemy fire until within 20 yards of the crest where it was showered with grenades. All except two men were wounded or killed, but Berry, although wounded, clung to the ground he had gained and sent a request to his platoon commander for more grenades. As the position gained by the section was untenable it was withdrawn. At this stage Rooke was wounded by a grenade.

A second platoon of Walker’s group, attacking from Old Vickers, was pinned by heavy fire from earthwork bunkers. During the two operations, crowned on the north with success and on the south with failure, the 2/7th had lost 9 killed and 17 wounded.16

While this attack was in progress Lewin’s platoon moved down Steve’s Track, dug in by 11.30 a.m. astride the Bobdubi Track on the enemy line of communication to the Coconuts, and cut their signal wire. At 1.15 p.m. the platoon killed one Japanese out of a party of five moving towards Salamaua; half an hour later two Japanese out of seven were killed going the same way, and at 4.15 p.m. one more Japanese was killed from a party of four travelling towards Bobdubi. Those who escaped Lewin’s ambush panicked and went bush, leaving weapons and equipment behind. Although the numbers were not great this action could not but have a very unsettling effect on the enemy on both sides of the ambush. During the next two days pressure by patrols and harassing mortar fire were maintained against the enemy in South Coconuts, and early in the morning of 17th August patrols found it unoccupied.

Again and again in the jungle it was found that encirclement did not mean destruction for those encircled. Dense growth and dark nights were the allies of those seeking to escape. So it happened on this occasion. Later investigations showed that the enemy had laid signal wire due east to the Francisco and, using the wire as a guide, had withdrawn from South Coconuts after darkness on the night of 16th–17th August. The whole of Coconut Ridge and the northern portion of Bobdubi Ridge were now in Australian hands.

Meanwhile, in the main battle area, the 2/6th was almost ready for the attack. Colonel Wood’s plan allotted the task of capturing the selected spot on Komiatum Ridge (Laver’s Knoll) to Captain Laver’s and Captain Edgar’s17 companies under Laver’s command. Another company was to

guard the line of communication and the fourth to carry supplies to the knoll. Reducing equipment to a minimum the troops would wear the clothes in which they stood, and each would carry his weapon and ammunition, pack, water-bottle filled, groundsheet or gas cape, pullover, spare pair of socks, mosquito lotion, four days’ operational rations and half a mess set. The attacking companies and the one protecting the supply route would each carry 7 picks, 14 shovels and 10 machetes, while the company carrying supplies forward would carry 10 machetes. Each rifleman would carry 150 rounds, each Bren gunner 200 rounds and each Tommy-gunner 200 rounds. All troops would carry two 4-seconds grenades, and twelve 7-seconds grenades would be carried for the grenade discharger.

By 3 p.m. on the 15th Laver Force and Price’s company were in position due west of Laver’s Knoll near the Mule Track. Since they were in danger of being observed by the Japanese on Komiatum Ridge Laver decided not to cross the Mule Track until early on the 16th.

On 13th August Colonel Jackson had issued the artillery’s operation order stating that the guns would support the operations of the 162nd Regiment, 17th Brigade and the 15th Brigade with timed concentrations, harassing fire and defensive fire.18 Separate arrangements for the attack on Roosevelt Ridge had been made between MacKechnie and the commander of the American artillery in the Tambu Bay area. Most artillery units were suffering from accurate counter-battery fire, particularly Thwaites’ battery of the 2/6th Field Regiment which was shelled on 12th August. The five observation posts manned by members of Thwaites’ battery – Captain McElroy19 and Lieutenants Lord, Dawson, Halstead20 and Scotter21 – extending from Old Vickers south to Wells OP and east to the western extremity of Roosevelt Ridge, did their best to support the infantry and arrange the salvation of their own and the American batteries by directing counter-battery fire. These observation post officers formed a pool and were allotted on call to guns not already committed to a task. For the attacks by the Australian brigades Dawson would be forward observation officer with the 15th Brigade, Lieutenants Melvin and Nelson from the 218th American Artillery Battalion would be with the 2/6th and 2/5th Battalions respectively, while Halstead would be with the 42nd Battalion. As usual the mountain battery had played its part. Heavy

artillery support was the more necessary because the air strike planned for 15th August was cancelled because of bad weather.22

By nightfall on 15th August Moten’s four battalions were ready. At 6 a.m. on 16th August Laver Force, with Laver’s own company leading, crossed the start-line. Ten minutes later the guns began to fire on Komiatum Ridge and Laver’s Knoll, and in half an hour they fired over 500 shells. Then the forward troops scrambled up the precipitous slope of Komiatum Ridge and arrived at their objective. The enemy, about a platoon, was surprised and fled leaving only one of their number dead. Laver Force immediately dug in and Laver sent Lieutenant Johnson’s platoon to occupy Johnson’s Knoll 150 yards to the south where the Japanese again fled leaving four killed.

Price’s company soon arrived, breathless but laden with ammunition and supplies. Sergeant White’s team carrying the heavy 3-inch mortar and ammunition actually followed Laver’s leading platoon to the objective, and the mortar was soon in action. After dumping their loads Price’s men set out down the steep rugged slope for the Coconuts which they left with their second load at 2 p.m., arriving at Laver’s Knoll again at 5 p.m.

Meanwhile Laver’s patrols had been active to the east, north and south seeking enemy positions, cutting signal wire, and trying to find the troublesome mountain gun.23 By 11.15 a.m. the Komiatum Track for 300 yards

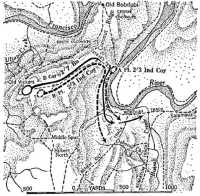

Allied and enemy dispositions, Salamaua area, 15th August

north of Laver’s Knoll was clear of enemy although areas south and South-east were still under sniper fire.

East of Laver’s Knoll the 42nd Battalion had suffered its first casualties as it prepared for its part in the encirclement of the Japanese on Mount Tambu. On the night before the capture of Laver’s Knoll the enemy had occupied a position just below Captain Greer’s24 company on Scout Ridge. The track from the company position crossed a saddle then led up Mount Tambu through an enemy perimeter to other enemy positions farther up the mountain. An Australian patrol probing along this track was climbing the mountain slope when the Japanese fired on it. The Bren gunner,

Private Eddlestone,25 answered the fire until he was killed. Private Read26 from the “fostering” company of the 2/5th Battalion rolled into Eddlestone’s place but fired only a few shots before he also was killed. Cursing and yelling Private Greene,27 6 feet 3 inches tall, charged from the patrol’s position up the ridge into the Japanese position. With his Owen he killed several of the enemy before he himself was killed by machine-gun fire. In its first action the 42nd had lost three men killed but had killed at least ten Japanese.

During the morning of 16th August the 42nd had observed Laver Force digging in. In the late afternoon enemy movement to the west and south of Johnson’s Knoll led Laver to expect an attack. When the tense and expectant machine-gunners on Davidson Ridge saw Laver’s Very lights soaring into the air at 6.45 p.m., they immediately placed a curtain of defensive fire south of Johnson’s Knoll. In this task the eight Vickers guns were aided by three 3-inch mortars.28 Half an hour later Moten rang Davidson to say: “I’ve just had word from Laver. Your defensive fire came down immediately, it was right on the spot and completely broke up the Jap attack.”

Soon after 7 p.m. more enemy movement was heard in the darkness to the west and south of Johnson’s Knoll, but 40 minutes later Johnson repulsed the attack 30 yards from his position by using grenades and small arms fire. During the night intermittent firing and enemy movement continued south of Johnson’s Knoll until, in the darkness at 4 a.m. on the 17th, Johnson’s men dimly saw a large Japanese force moving straight down the track from the south and west. As with the first attack, this third attack was dispersed by the prompt reply of the 42nd to a call for defensive fire.

As Laver Force had been harassed by an enemy mountain gun, Moten asked Taylor to use his 81-mm mortars in an attempt to silence it. Observation was made by an infantry officer (Captain Cole29) on Davidson Ridge, fire was directed by phone through Colonel Taylor’s switchboard over at least 25 miles of wire, and apparently not only the gun but a large ammunition dump was destroyed by the American mortars. The machine-gunners of the 42nd had the best hunting for the day when they picked off Japanese trying to put out a kunai fire started by mortar smoke bombs.

After dusk on the 17th the Japanese came again for the fourth time from south and west against Johnson’s Knoll. This attack and three subsequent ones between 7 and 8.15 p.m. were all launched with great determination but stubborn defence and very accurate supporting fire broke up all the attacks.

The capture of Komiatum and Mount Tambu by 17th Brigade, 16th–19th August

The 18th was a quiet day for Laver Force, which was strengthened when a Vickers gun was carried up from Coconuts. At 3.35 p.m. a patrol from the 42nd Battalion arrived at Laver’s Knoll, having encountered no enemy on the way. With the occupation of Laver’s Knoll the enemy was surrounded in the Mount Tambu and Goodview Junction areas. His attempts to break out along Komiatum Ridge had been unsuccessful;

his position was growing desperate as pressure was maintained from all sides and artillery, mortars and machine-guns pounded his positions. Meanwhile, the 2/5th Battalion had been ordered to capture the pillbox area south of Goodview Junction two nights before Laver’s attack.

The task was allotted to Captain Bennett’s company which set out a night late (on 16th–17th August) after Laver’s Knoll had been captured. The attacking platoon followed tapes for a while but then became lost. Towards dawn it found itself on a ridge below which were a large number of the enemy. About 18 of them were killed but it was now light and the company withdrew under heavy fire.

At 4.30 p.m. on 17th August the stubbornly-defended Hodge’s Knoll was found deserted and was immediately occupied by Bennett’s company. To the north the junction of Stephens’ and Mule Tracks was found unoccupied but the enemy was 40 yards along the track leading from the junction to Komiatum Spur. During the night a patrol from Bennett’s company set out through Hodge’s Knoll down to the Mule Track, then climbed a very steep track towards Mount Tambu where fire from pill-boxes stopped it. At first light another patrol moving cautiously up the Komiatum Track was also stopped by fire from the pill-boxes. During the day the Australians were unable to encircle the razor-back and could make no headway frontally. East of the junction of Stephens’ and Mule Tracks another platoon found a Japanese position on a razor-back similar to the one confronting Bennett, and could make no progress.

At Port Moresby in mid-August, important decisions about the future of the command in the forward area were being made. On 15th August the Commander-in-Chief, General Blamey, with his Deputy Chief of the General Staff, General Berryman, arrived at General Herring’s headquarters from Australia.30 Blamey sent Berryman forward to see Savige and report on the situation at the distant front.

When he received a signal from Herring at 4 p.m. on 16th August saying that Berryman proposed visiting the divisional area Savige foresaw trouble. Were the senior commanders dissatisfied with the way things were going? Herring asked Savige to meet Berryman at Moten’s headquarters on the 19th, and stated that Lieut-Colonel Daly31 would travel with Berryman to relieve Wilton who had been selected for an appointment on the Military Mission at Washington. Berryman arrived at Tambu Bay by landing craft on 17th August, and next day moved through Taylor’s headquarters near Mount Tambu to Moten’s headquarters, 24 hours before Savige expected him.

After Moten had described how the Japanese were surrounded and would probably try to break out the next morning, Berryman realised that he had walked into one of the decisive battles of the Salamaua campaign. By the night of the 18th Moten’s four battalions were pressing in on the enemy from all directions. It was obvious that the Mount Tambu area could not be held much longer; indeed the Japanese had

already given evidence of their intention to evacuate when an American patrol in the late afternoon of the 18th worked its way to near the crest of Mount Tambu and reported indications of at least partial evacuation.

Among the surrounded Japanese was Lieutenant Shimada who wrote a report to his company commander:

The two men defending No. 6 position were killed. The enemy has penetrated in this area. We went out to meet this attack but were unsuccessful. At present we are face to face with the enemy. With the four men at No. 5 position, we will again try to counter-attack. As the enveloping enemy is quite strong, attack or retreat is difficult. Our strength is platoon commander and 18 men (two dead, and the 4 who went for fuel have not returned). Our telephone lines have been cut by the enemy. We will die in defence of our positions and drive back the enemy. ... It will be extremely useful if you will press the enemy, who have penetrated No. 6 position, from the right rear flank.

Captured in the Mount Tambu area was a notebook belonging to Private Hamana of the battered 115th Regiment whose attitude was less zealous than Shimada’s. Against the date 18th August he wrote:

Living in the mountains in front of Mount Tambu I wonder why they don’t send things up to the front line? This is the reason the company’s faces are pale, their beards long and bodies dirty with red soil from the ground. We are just like beggars. Because of the scarcity of men, to continue duty is to weaken the body. Everyone is longing for a full stomach. The higher officials should give a little more consideration and quickly replace the 51st Division with the fresh 41st Division or the 51st will become decrepit.

From first light on the morning of 19th August Laver Force was very active. At 6.30 a.m. Sergeant Harrison32 led a patrol north from Laver’s Knoll about 100 yards and found a new track leading to the east. This track had been much used by the enemy and it seemed as though they may have withdrawn during the night. At 7.30 a.m. a patrol south from Johnson’s Knoll found many enemy text books and papers. Two knolls north of Laver’s Knoll were then occupied by Edgar’s company; one of them had sheltered a mountain gun position. A patrol from Laver’s company, moving back to Davidson Ridge with the 42nd Battalion patrol, found a track six feet wide on the eastern slopes of Komiatum Ridge. Along this track also there had been considerable movement to the north during the night. Further evidence of a general withdrawal was the attempt of small enemy parties to cross the Australian line of communication to Coconuts during the day.

Early on 19th August patrols of the 2/5th found enemy positions at Goodview Junction and on Goodview Spur deserted. As a stream of reports began to flow in to the brigade headquarters from Conroy indicating that the Japanese were withdrawing, Moten realised with satisfaction that the battle was being fought as he had planned it. After waking Berryman he ordered Conroy to advance along the Komiatum Track and join Laver. Captain Bennett’s company led the advance and Berryman and Moten joined in. For a time they were with Bennett and his leading

platoon commander, and just behind the leading section. Major-generals and brigadiers are likely to be an embarrassment to a patrol commander, and, after a time, the exasperated Bennett prevailed on Berryman and Moten to move farther back.

With opposition from enemy stragglers only, Bennett’s company advanced to the junction of the Komiatum and Mount Tambu Tracks. Here Moten reminded Berryman that he was to meet Savige at midday. On their way back to Bui Eo Creek the two leaders met the signallers laying line. Moten telephoned his brigade major, Eskell, at brigade headquarters and told him to get the Americans moving. He was convinced that the Japanese had vacated their positions on Mount Tambu because Bennett had been able to reach the track junction, and therefore ordered that Taylor should clear Mount Tambu and join the 2/5th Battalion at the track junction as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, Savige was walking along the track towards Moten’s headquarters. For the most part he was silent as he made up his mind how to handle his talk with Berryman. He then discussed his plan with Wilton, knocked it into shape, and stuck to it in his later discussions. The two men arrived a little before midday and Eskell informed them that Berryman and Moten were in the forward area. He then made tea for them and they were drinking it when Berryman arrived at Moten’s office. After saying good morning to Berryman, Savige asked Moten, “How’s she going?” and up went Moten’s thumb. Savige then asked Moten to outline the situation.

After Moten had done this Savige ordered him to exploit north along the Komiatum Track and to get the 42nd Battalion moving towards Nuk Nuk along the high ground of Scout Ridge; he also warned that Hammer would exploit towards Komiatum Ridge from the direction of Orodubi and Erskine Creek. Savige asked Moten to send Taylor’s battalion back to join the rest of the 162nd Regiment in accordance with his promise to MacKechnie. Turning to Wilton Savige ordered him to “issue the necessary orders to get things going”. Savige, Berryman and Moten then went to the mess where, after a drink and a chat, Berryman handed Savige a letter signed by Herring on the 16th. This began:

The Commander-in-Chief has directed that the time has arrived for the relief of Headquarters 3rd Australian Division and that it be relieved by Headquarters 5th Australian Division as early as possible. Major-General Milford is en route from Australia (ex leave) and should report to your Headquarters within the next seven days. The command of the forces now operating under your command in the Salamaua operations will pass to him as and when mutually agreed upon by yourself and him.

The letter also dealt with the need to establish divisional headquarters at Tambu Bay, and to organise a supply system whereby “your forces can be maintained from the sea and without air droppings as from 28 Aug at the latest”. The letter concluded: “Am glad your plans have worked out so well; aggressive action should enable you to shorten your supply lines in the next day or two.”

After reading the letter Savige turned to Berryman and said, “Frank, I have had rather a difficult and trying time but as you see we have got away with it.” Savige had indeed “got away with it”. He was a successful general in an operation which he later described as the “toughest operational problem I ever faced” in experience covering campaigns in four continents.33

While the generals were meeting at the Bui Eo Creek reports from all sectors confirmed the departure of the Japanese from positions which had previously seemed impregnable. They were no longer on the ridge east of the junction of Stephens’ and Mule Tracks; two platoons from the 2/5th followed Walpole’s Track unmolested to the Komiatum Track. Captain Walters’ company then advanced along the Komiatum Track, passed through Bennett’s position and moved north towards Laver’s Knoll.

It was no surprise when an American platoon from Captain George’s company reached the crest of Mount Tambu without opposition late in the morning of 19th August. The platoon mopped up enemy stragglers before two companies from the I/162nd Battalion moved on to Mount Tambu from the east. A platoon then advanced along the Mount Tambu Track and met the 2/5th Battalion at the track junction.

After four long weeks of artillery and mortar pounding and three direct assaults Mount Tambu was at last in Allied hands (wrote the historian of the 41st American Division). Jap positions were found, in many instances, to be ten feet underground with a complete system of tunnels and connecting trenches. At least a full battalion, with virtually perfect organization underground, had occupied the position. Artillery and mortar fire had done little damage to the position but apparently had broken the morale of the garrison.34

After his talk with Berryman a thoughtful Savige accompanied by Wilton set out immediately after lunch to visit the conquerors of Laver’s Knoll. On the way they passed through part of the 2/5th Battalion. Some stray bullets were flying as the two officers arrived on Laver’s Knoll. Laver was then busy counter-attacking to the north and did not notice Savige in a slit trench until, with a startled look, he came along and said, “Sir, you shouldn’t be here – it’s too hot.” “To hell with you,” said Savige, “get on with your battle and forget us.”

Walters’ company from the 2/5th Battalion arrived at Laver’s Knoll soon after 2 p.m. thus completing the link-up of Wood’s, Conroy’s and Taylor’s battalions. Moten then ordered Davidson to patrol to the Americans on Mount Tambu. Lieutenant Stevenson35 led this patrol, which soon began to run into the Japanese retreating from Mount Tambu. Seeing eight Japanese approaching Stevenson set an ambush which killed five of them, the others going bush. When a large Japanese force approached,

Stevenson fell back to await it. On the way Lance-Corporal Miller36 met a lone Japanese to whom he said affably, “Good day; going some place?” and then dispatched him irrevocably towards it. The enemy force disappeared, probably down the gorge between Komiatum and Davidson Ridges. Captain Greer then led a patrol to clear the track, and, just on dusk, he rang from the American positions to say that the track was clear.

As on previous occasions many of the enemy had slipped through the Allied cordon, but they had been forced to desert defences which had proved a stumbling block to the 17th Brigade’s advance. The splendid planning for the Komiatum offensive was matched by near faultless execution by the troops. “This little battle has been the perfect action. Everything went exactly according to plan,” wrote Wilton that night. General Adachi said later that, as a result of Australian infiltration and bypassing, Komiatum was endangered; therefore, about the middle of August, the garrison withdrew to “Grass Mountain” (Charlie Hill37).

After the capture of Roosevelt Ridge Colonel MacKechnie’s advance had been stopped to the west and North-west. On the east and North-east the Americans were faced with a series of ridges running to Dot Inlet. During Moten’s attack on Mount Tambu American patrols had maintained pressure on the known Japanese positions near the junctions of Roosevelt and Scout Ridges and Roosevelt and “B” Ridges. They had been unable to make any gains and by 17th August the III/162nd Battalion was stationary, pinned down by enemy fire from the junction of Roosevelt and Scout Ridges. On 18th August MacKechnie told Savige that his total fighting strength was down to 791 and that, with 30 evacuations a day, he had insufficient troops to guard Tambu Bay. He added, “We will continue to do our best but insufficient numbers and resulting exhaustion may lose us golden opportunities or result in failure at critical time.” Savige replied:

Will send you one of Taylor’s coys within forty-eight hours. With luck remainder should follow thirty-six to forty-eight hours later. ... Can you lay hands on any sub-unit such as cannon company? Can you organise further detachments from people in rear not otherwise fully employed? This will provide some measure of rest for tired troops in forward areas.

On the 19th Captain Pawson,38 the divisional liaison officer with the Americans, signalled Savige that the Americans’ morale was high and they were determined to beat the enemy. Pawson stated that MacKechnie was worried that he may have given the wrong impression about the morale of his troops. “Point he wished to make was that troops were in need of rest from continual strain of shell and mortar fire in forward area,” continued the signal. “There is definitely no suggestion of troops breaking in

any sector.” Realising the need for improvisation MacKechnie streamlined his headquarters, and formed a provisional battalion, consisting of the anti-tank company, cannon company and regimental band.

When he learnt that the track between the I/162nd and 42nd Battalions was clear, Savige was able to redeem his promise to release the first of Taylor’s companies within 48 hours. With the occupation of Mount Tambu the I/162nd Battalion had finished its task under Moten’s command and by 21st August it returned to MacKechnie.

The 42nd Battalion meanwhile investigated a reported enemy position north of the junction of the Boisi and Scout Ridge Tracks. A patrol led by Lieutenant Cameron39 set out to investigate on 18th August. As he and two men were creeping towards the enemy position a sentry fired and hit the youthful Cameron who fell into a narrow gully. One of the men (Corporal Stevens40) sent back for the patrol while he himself dressed Cameron’s wounds and then carried him through the jungle for 500 yards in an easterly direction towards where he thought he would find Scout Ridge. Here the two men waited in vain for the patrol until Cameron ordered a reluctant Stevens back to return next morning with help. Stevens put Cameron beside a log, covered him with leaves and set off using Cameron’s compass. At dusk he arrived back on the track junction where he found the patrol.

Davidson’s plan to attack the Japanese perimeter north of the track junction was postponed while patrols set out on 19th August to find Cameron. In the early morning Stevens accompanied a searching patrol but returned baffled unable to find the log. Major Crosswell,41 the battalion second-in-command, then led a large search party towards the enemy position. Disregarding the wild Japanese firing the patrol followed Stevens’ attempt to retrace his route and finally found Cameron in high spirits and beginning to crawl back to safety despite a compound fracture of the left thigh. He was one of the few soldiers who had ever had an attack postponed for him.

After the capture of Mount Tambu the 42nd Battalion turned north and North-east and intercepted enemy parties escaping from Mount Tambu between Komiatum and Davidson Ridges. At dusk on 19th August Captain Cole’s company overlooking the track down Davidson Ridge watched 20 Japanese walk into its ambush before firing on them. Next morning 12 dead Japanese were counted.

On 20th August Davidson ordered the capture of what he thought were only two knolls to the north of the battalion’s positions on Davidson Ridge. The smaller knoll was occupied without opposition and Lieutenant Ramm’s42 platoon seized the second knoll against slight opposition.

Next morning Cole reported that there was another feature (Bamboo Knoll) about 600 yards farther north of the one occupied by Ramm. Davidson ordered him to capture it immediately and this was done with little opposition. From the kunai clearing on top of the knoll Cole’s men could see Salamaua and shells from the Allied artillery landing there. They could not see the airstrip because another hill was in the way. Before actually seeing this hill (Charlie Hill), Davidson’s Intelligence men thought that it was the one they had reached. The inaccuracies of the map had deluded them. Often from now on the battalion diarist recorded “these orders not put into effect due to our position not being as far north as we thought”; or “due to inaccuracies in the Komiatum sheet, these map references later found to be misleading and companies actually moved” to other positions.

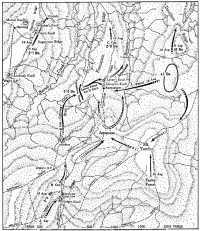

Meanwhile the 15th Brigade on the left flank had not been idle. Even before patrols from the 2/7th Battalion had found the South Coconuts unoccupied on the 17th, Hammer’s troops were moving towards their next objective, the Salamaua–Bobdubi–Komiatum track junctions. On the 15th Hammer had called together his three unit commanders, Major Picken of the 2/7th, Major Warfe now commanding the 58th/59th and Captain Hancock of the 2/3rd Independent Company, and issued his plan. A company of the 2/7th (Baird’s) and two platoons from the Independent Company (Lewin’s and Winterflood’s) would be used in the attack while the 58th/59th created a diversion in the Erskine Creek–Graveyard area and set an ambush on the Komiatum Track east of Newman’s Junction. As a preliminary move Winterflood would secure the high ground east of Middle Spur and north of Hilbert North, while Lewin’s would capture the area between the track junctions suspected to be a Japanese staging camp, and link up with Winterflood’s platoon. Baird’s company would then move through and capture the two track junctions.

It was obvious that the enemy was occupying the track junctions and the northern corridor between the Komiatum and Bench Cut Tracks in strength. On 15th August Lewin’s platoon successfully withstood a bayonet attack on its ambush position near the junction of Steve’s and Bobdubi Tracks by a party of 30 Japanese from the east, and Lieutenant Allen’s patrol next day skirmished with about 40 entrenched Japanese just south of the Bobdubi–Salamaua track in the corridor between the Komiatum and Bench Cut Tracks.

The attacking force-100 men from the Independent Company and 66 men from the 2/7th Battalion – were faced with a heavy task. A panoramic view from a bomb crater on Coconut Ridge as well as patrol reconnaissance showed that an unusually thick belt of jungle ran across the proposed line of advance. As he sat on the side of the bomb crater on 16th August pointing out targets to the artillery observation post and mortar and machine-gun officers Hancock regarded his task distastefully. It was apparent that observation would be restricted to a few yards, thus making it extremely difficult to travel off the main Bobdubi Track. The flat ground provided no natural and solid cover from fire and gave promise

The attacks by 2/7th Battalion and 2/3rd Independent Company on Bench Cut–Bobdubi track junctions, 17th–18th August

of increasing the effectiveness of the enemy’s small arms. Hancock and Baird hoped that these disadvantages might be offset by an air strike which would not only have a physical effect on the defenders and dampen their enthusiasm, but would thin out the jungle, lay bare the enemy’s positions, and dig craters which would provide some cover from fire. These points had been emphasised by the experience of one of Hancock’s patrols which, although moving with the utmost caution, had unwittingly walked into the midst of the enemy’s defences and had experienced great difficulty in extricating two wounded men. The dank gloom of the jungle flats also had its effect in depressing the men who arrived back on the ridge blinking at the light and sighing with relief at leaving this jungle dungeon. It was with foreboding that Hancock and Picken learnt late in the evening of 16th August that no aircraft would be available for strikes on 17th and 18th August. The attack, however, would go in as planned.

During 17th and 18th August the troops watched big fleets of American heavy and medium bombers flying North-west, and wondered. They were on their way to Wewak, where, Intelligence had learned, more than 200 Japanese aircraft were concentrated on four airfields. More than half the Japanese aircraft were either destroyed or badly damaged, and the Japanese Air Force in New Guinea was greatly reduced. There was little doubt that the Japanese air fleet was intended to support Japanese operations in the Lae–Salamaua area.

Between 10 and 11 a.m. on the 17th artillery, mortars and machine-guns opened up on the green carpet of tree tops. The attackers hoped that a proportion of the missiles would reach their destination. Moving cautiously along the Bobdubi–Salamaua track, Lewin met opposition from Japanese strongly entrenched east of a small creek bed which crossed the track. Meanwhile, Winterflood on Lewin’s right moved round the foot of spurs leading up to Bobdubi Ridge and clashed with the enemy on their line of communication to the Hilberts and Middle Spur. His platoon killed five Japanese, but as he was about to push on to the main defences he was attacked from behind by another enemy force moving down the

Hilberts spur. Between two fires he was forced by 2 p.m. to withdraw to the next high ground to the north.

The attack was thus stationary, but Lewin’s patrols began to probe to the flanks in an endeavour to find any weak spots in the enemy defences. About 150 yards to the south one of his patrols found a place whence the Japanese had unaccountably withdrawn leaving large quantities of equipment. Major Picken, in charge of the attack, then decided that a reinforced platoon, under Lieutenant Jeffery of the Independent Company, would drive straight through to the Japanese staging camp area and consolidate there, ready for the following troops to pass through to the Komiatum Track junction.

Jeffery found the staging camp unoccupied, but Baird, following with the remainder of his company, could find no signs of the spearhead force. He was faced with a problem, which he solved by deciding that his present area was too valuable to lose. He therefore dug in and sent out a patrol to find Jeffery. Visibility was about five yards and the area was covered with the densest jungle yet encountered by these troops. The patrol could find nothing and withdrew. Lewin’s company attacked only to find the opposition along the creek stronger. At 6.30 p.m. he repelled a vicious Japanese counter-attack, although his casualties were heavy – 5 killed including Lieutenant Barry, and 11 wounded. By dusk the Australian attacking force was thrust like a wedge into the enemy positions: Lewin on the left, Baird forward and centre, Winterflood on the right. Jeffery’s strong patrol was out of touch although firing in the jungle ahead at 6.30 p.m. gave a clue that it was in trouble.

The mystery of Jeffery’s disappearance was not solved until dawn on the 18th when Lieutenant P. C. Thomas and Sergeant Clues,43 who were both wounded, and five men from Jeffery’s patrol arrived exhausted at Old Vickers. It was then learnt that on reaching the staging camp and finding it empty the patrol, allowing enthusiasm to outrun discretion, had pushed on in an attempt to find the Japanese. Advancing east through the dense jungle, it had encountered concealed enemy positions near the Komiatum Track junction. In the ensuing fight the patrol had been at a disadvantage as it had cover only from the trees and none from the lie of the land. After suffering heavy casualties Jeffery had sent runners back to tell Baird what was happening but they could not get through because the area seemed suddenly alive with Japanese. Withdrawing, Jeffery had run into another ambush astride his route back to the staging camp, and more men were hit. On the evening of the 17th a group of wounded men under Thomas had tried to reach Baird’s position. Being unable to find the staging camp, and realising how risky it would be to approach it in darkness, the wounded men had remained in the bush until the early morning, when they had found themselves at the foot of the spur leading to Old Vickers.

Thomas’ fit men, after a good meal, returned to Baird’s position to act as guides. Lieutenant Fleming44 then led a patrol into the dense jungle, and, as a result of shouting, another group of Thomas’ men materialised from the jungle and were sent back to the west. Trying to find the remainder of the patrol Fleming found the enemy instead. Two parties of about 40 and 20 Japanese respectively were trying to cut off this patrol, but by moving wide Fleming managed to return safely about 10 a.m. with the enemy following.

On the left flank Lewin’s platoon resolutely withstood strong Japanese attacks for three hours from 3 a.m. The strongest attacks were on his right but the enemy were unable to dislodge his platoon. The attacks ceased at dawn but began again with increased violence soon after Fleming’s return. The diarist of the 2/7th Battalion described the fights thus:

The enemy launched himself on all points of the line held by the force. The fire exchanged was tremendous and the observers in the command post were at a loss to know where the enemy were. The noise of small arms and the thumping of 36 grenades grew to a roar as though the Japs were attempting to scare the troops out by an impressive demonstration of fire. A call for defensive fire brought the mortars in play and the crash of bombs added to the noise. Finally the MMG opened up on their defensive lines and their chatter just completed the din.

During the remainder of the 18th patrols cautiously investigated the wall of jungle ahead. Although they were not successful in either pinpointing Japanese positions or in extricating Jeffery’s men, they did have the effect of gradually forcing the enemy back to the line of the Komiatum Track.

To the south the 58th/59th Battalion was busily playing its part in attracting Japanese attention. During 17th August its patrols were active and aggressive. For the loss of 18 casualties, including one company commander, Captain Blackshaw,45 wounded, 23 Japanese were killed, 10 of them at Erskine Creek. Next day there were signs that the Japanese were thinning out.

With the enemy being driven back on the north and with signs of his impending withdrawal on the southern sector opposite the 15th Brigade, it appeared to Savige that the enemy intended to hold with a strong rearguard the area from the track junctions along the line of the Hilberts–Erskine Creek–Graveyard-Orodubi–Exton’s Knoll, with the intention of withdrawing from the Mount Tambu–Komiatum-Goodview Junction area and then from the southern portions of his line opposite the 15th Brigade. Events on 19th August gave added weight to this belief.

It was not until 2 p.m. on the 19th that a patrol at length found the missing men of Jeffery’s patrol – all wounded and exhausted. Jeffery himself died next day. A platoon occupied the area where Jeffery had been found, and saw no enemy there; Lewin also found that the enemy had withdrawn.

On the morning of the 19th Hammer warned his units that the enemy were withdrawing from the Mount Tambu–Komiatum area, and told them to watch for the Japanese and engage them with mortars and machine-guns. Lieutenant Fietz’s company on North Coconuts could observe the Komiatum Track, and in the late afternoon enjoyed the sight of retreating Japanese groups being battered and harassed by mortars and machine-guns. Warned to harass the enemy retreating north from Mount Tambu, the 58th/59th Battalion had been largely responsible for providing this spectacle. Without opposition several of the positions which had proved such obstacles in the past were occupied by the 58th/59th: the Erskine Creek area, North and South Pimples and Orodubi.46

The unpleasant tasks of the 2/7th Battalion and 2/3rd Independent Company in fighting the entrenched enemy around the flat track junctions were now being rewarded. The turning of the enemy’s flank by the attack along the line of the Bobdubi–Salamaua track from 17th August onwards had hastened the enemy’s withdrawal from Mount Tambu and the Orodubi “pocket” area.

Just before midnight on 19th August Savige phoned Hammer’s headquarters, and, in the absence of the brigadier, instructed Travers to secure Kennedy’s Crossing and patrol the line of Buiris Creek north of the Francisco. As enemy resistance had collapsed in the Mount Tambu area, Savige ordered that every effort should be made to close the enemy’s avenue of escape between Komiatum and Bobdubi Ridges. When Travers said that Hammer was worried about his northern flank, Savige replied that the 15th Brigade would be relieved of responsibility for the area south of Erskine Creek.

Hammer prepared to take advantage of the enemy withdrawal but it was necessary for his men to move cautiously through booby-trapped areas and clear up the area before setting off in full pursuit. At 4 a.m. next morning all units of the brigade had a hot meal, and an hour later they were on the move. Two companies of the 2/7th Battalion (Baird’s and Cramp’s) attacked where the Bobdubi–Salamaua track crossed the Buirali, captured some pill-boxes, and then withdrew for a mortar shoot on the remaining pill-boxes. Fighting stubbornly the Japanese hung on. By nightfall the two companies were still attacking the junction area. Another company (Captain Arnold’s47) advanced north along the Bench Cut Track, the fourth company (Major Dunkley’s48) gathered at the north end of Bobdubi Ridge, and a platoon crossed the Francisco and reconnoitred the area north and west of Buiris Creek. A platoon of the 2/3rd Independent Company found the Hilberts–Middle Spur area abandoned and moved

along what had been the enemy line of communication before reaching the 2/7th Battalion near the track junctions. By nightfall on the 20th the Independent Company had thrust from Malone’s Junction to the Buirali, thus effectively cutting the Komiatum Track also. On the 20th the 58th/59th also reached the Komiatum Track in several places. One company was astride the Komiatum Track half way between Erskine Creek and Newman’s Junction; another deloused 60 booby-traps along the Bench Cut in the same area. Major Rowell’s49 company from the Graveyard area was fired on as it approached the Komiatum Track. Lieutenant Mathews50 then led his platoon round the east flank and, after an exchange of fire lasting for about an hour, he withdrew and led the company round the west flank after cutting a track. Late in the afternoon the company reached the enemy’s main Erskine Creek Track and moved down it towards its junction with the Komiatum Track. Near the junction of the Erskine and Buirali Creeks the company again encountered a Japanese position.

Newman’s company later met heavy resistance at the junction of the Komiatum and Orodubi Tracks where the Buirali joined Buiwarfe Creek. The company then attacked from the south but, like Rowell’s from the west, they could not see the enemy, nor could they find suitable cover from enemy fire which swept the flat ground. The Japanese position was a well-chosen one in a bottleneck and commanding the ground east of the track. Nevertheless the two companies were beside and across the Komiatum Track, and a patrol to the south met the forward company of the 2/6th Battalion at the northern extension of Moten’s advance.

By nightfall on the 20th the enemy had been pushed back to the general line of the Komiatum Track and beyond. Hammer now had freedom of movement along the Bench Cut from Ambush Knoll to Osborne Creek. His ambushes along the Komiatum Track, however, had not trapped the retreating Japanese. This fact supported his belief that the Japanese line of communication now led from the Komiatum–Orodubi track junction up Charlie Hill to Salamaua.

North of Brigadier Hammer’s main area Captain Whitelaw’s company of the 24th Battalion had been patrolling the tracks east towards the coast from its forward base without incident until 19th August, when a three-man patrol from Lieutenant Barling’s51 platoon was ambushed about a mile along a track which left the Hote–Malolo track and led South-east towards Buiris Creek. One man – Private Mathews52 – was killed.

Still farther north Colonel Smith, on 7th August, received an interesting and encouraging signal from Savige: