Chapter 8: The Pacific Front

IN mid-1943 the Allied leaders in London and Washington were considering ambitious proposals for accelerating the defeat of Japan. Thus, on 6th April President Roosevelt discussed with his Chief of Staff, Admiral William D. Leahy, the Joint Chiefs, and Harry L. Hopkins, his adviser and assistant, the possibility of a campaign in Burma to open a road into China. Leahy later described the outcome:

Great Britain apparently did not wish to undertake a campaign against the Japanese in the Burma area, and it was certain that Japan would interrupt our air transportation to China if its forces in Burma were not fully occupied in resisting Allied ground troops. ... President Roosevelt appeared determined to give such assistance as was practicable to keep China in the war against Japan.1

On the other side of the Atlantic Mr Churchill, aware of the Americans’ high estimate of the military importance of China, had no doubts about what the Americans were thinking concerning Burma. The advance on Akyab had failed and its capture before the monsoon was now impossible. No advance had been made from Assam. There had been some increase in the air transport available for the China route, but the full development of the air route and the requirements for a land advance towards central Burma had proved utterly beyond British resources. Churchill wrote later:

It therefore seemed clear beyond argument that the full “Anakim” [reconquest of Burma] operation could not be attempted in the winter of 1943-44. I was sure that these conclusions would be very disappointing to the Americans. The President and his circle still cherished exaggerated ideas of the military power which China could exert if given sufficient arms and equipment. They also feared unduly the imminence of a Chinese collapse if support were not forthcoming. I disliked thoroughly the idea of reconquering Burma by an advance along the miserable communications in Assam. I hated jungles – which go to the winner anyway – and thought in terms of air-power, sea-power, amphibious operations and key points. It was, however, an essential to all our great business that our friends should not feel we had been slack in trying to fulfil the Casablanca plans and be convinced that we were ready to make the utmost exertions to meet their wishes.2

On 20th April Roosevelt received a message from Churchill suggesting that he and his full military staff should come to Washington for consultation early in May. The date was fixed for 12th May.

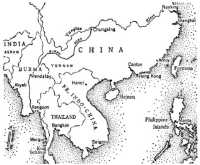

Meanwhile, on 28th April, the Joint Chiefs’ planning staffs, possibly influenced partly by the Navy’s desire to press on against Japan and partly by the President’s interest in China, recommended the establishment of a large number of air bases in China, the maintenance of which would require, first the opening of a port such as Hong Kong, and secondly the reopening of the Burma Road. The port to be opened on

the China coast could best be maintained by a direct drive across the central Pacific from Pearl Harbour to the Philippines. Although they recommended a simultaneous advance from the South-West Pacific Area they considered that MacArthur’s proposed line of advance from New Guinea to the Philippines would follow the long way in and would have a vulnerable right flank.

When on 2nd May Roosevelt discussed the impending conference at Washington with Hopkins, Leahy and the Joint Chiefs, the Army Chief of Staff, General Marshall, declared that without an immediate offensive in northern Burma the air-ferry service to China would be destroyed by Japanese attacks on the landing fields. And at the Joint Chiefs’ final pre-conference meeting with the President on the 8th it was agreed that, although the principal American objective at the conference would be to pin the British down to a cross-Channel invasion of Europe as soon as possible, the Americans should also press for some action in Burma.

On their way to Washington on 5th May Churchill and his staff prepared a paper on the situation in the Indian and Far Eastern spheres. Largely in order to seize the initiative at the conference his plan contemplated landings on the Andaman Islands, Mergui with Bangkok as the objective, the Kra Isthmus, Sumatra and even Java.

Churchill would no doubt have been the first to admit that these proposals were merely conference tactics. He sent a frank signal to Marshal Stalin in Russia on 8th May: “I am in mid-Atlantic on my way to Washington to settle further exploitation in Europe after Sicily, and also to discourage undue bias towards the Pacific, and further to deal with the problem of the Indian Ocean and the offensive against Japan there.”3

The “undue bias” was causing deep concern to Churchill’s advisers. For example, on 6th May the British Chief of the General Staff, General Brooke, wrote in his diary:

There is no doubt that, unless the Americans are prepared to withdraw more shipping from the Pacific, our strategy in Europe will be drastically affected. Up to the present the bulk of the American Navy is in the Pacific and larger land and air forces have gone to this theatre than to Europe in spite of all we have said about the necessity of defeating Germany first.4

Indeed, there were, in June, 13 American divisions in the Pacific, and 10 in the United Kingdom or Mediterranean.

At the Washington conference, which lasted from 12th until 25th May, the main decision was to fix the date for the cross-Channel invasion of Europe (OVERLORD) by an initial force of 29 divisions beginning on 1st May 1944. If the forthcoming assault on Sicily – it opened on 10th July – did not cause Italy to surrender, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Allied Commander-in-Chief in North Africa, would be authorised to proceed as he thought fit to bring about the elimination of Italy from the war.

Turning to the Pacific the Combined Chiefs resolved “upon defeat of the Axis in Europe, in cooperation with other Pacific powers, and, if possible with Russia, to direct the full resources of the United States and Great Britain to force the unconditional surrender of Japan”. They added: “If, however, conditions develop which indicate that the war as a whole can be brought more quickly to a successful conclusion by the earlier mounting of a major offensive against Japan, the strategical concept set forth herein may be reversed.”5

In other words the conference did nothing to reconcile the variety of the opinions canvassed by the various leaders. These opinions were tartly summed up by General Brooke in his private diary on 24th May:

May 24th. Washington. Today we reached the final stages of the Conference, the “Global Statement of our Strategy”. We [concluded] with a long Combined Meeting at which we still had many different opinions which were only resolved with difficulty.

Our difficulties still depended on our different outlook as regards the Pacific. I still feel that we may write a lot on paper, but that it all has little influence on our basic outlooks which might be classified as under:

(a) King thinks the war can only be won by action in the Pacific at the expense of all other fronts.

(b) Marshall considers that our solution lies in a cross-Channel operation with some twenty or thirty divisions, irrespective of the situation on the Russian front, with which he proposes to clear Europe and win the war.

(c) Portal considers that success lies in accumulating the largest Air Forces possible in England and that then, and then only, success lies assured. ...

(d) Dudley Pound on the other hand is obsessed with the anti-‘U’ boat warfare and considers that success can only be secured by the defeat of this menace.

(e) Alan Brooke considers that success can only be secured by pressing operations in the Mediterranean to force a dispersal of German forces, help Russia, and thus eventually produce a situation where cross-Channel operations are possible.

(f) And Winston? Thinks one thing at one moment and another the next moment. At times the war may be won by bombing, and all must be sacrificed to it. At others it becomes necessary for us to bleed ourselves dry on the Continent because Russia is doing the same. At others our main effort must be in the Mediterranean directed against Italy or the Balkans alternately, with sporadic desires to invade Norway and “roll up the map in the opposite direction Hitler did”. But more often than all he wants to carry out all operations simultaneously, irrespective of shortage of shipping.6

There were no representatives of the South-West or South Pacific Areas at the Washington conference to state their case as the commanders in the China, Burma and India theatres had been able to do.7 So far as the Pacific theatre was concerned the upshot of the conference was that “General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz were directed to move against the Japanese outer defenses, ejecting the enemy from the Aleutians and seizing the Marshalls, some of the Carolines, the remainder of the Solo-mons, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the remainder of New Guinea”.8

The Australian Army in June 1943 still included 10 infantry divisions and two armoured divisions. MacArthur’s American formations now included or would soon include the Sixth Army Headquarters, under Lieut-General Walter Krueger, I Corps Headquarters, and four divisions: the 32nd and 41st; the 1st Marine from Guadalcanal; and the 1st Cavalry, to arrive in Queensland in July.

In the South Pacific Area Halsey still had seven divisions. The 2nd Marine Division had returned to New Zealand in February to recuperate after Guadalcanal. The 3rd Marine at the end of June sailed for the Solomons, where also the Americal, 25th, 37th and 43rd were established. The 3rd New Zealand Division, formed in 1942, garrisoned New Caledonia from late in 1942 until August and September 1943.

After receiving the Joint Chiefs’ directive of 28th March MacArthur’s planning staff had set to work to produce a plan for operations in the SWPA and South Pacific in 1943. Much of the preliminary planning had already been done, and, indeed, merely required what the American military historian has called a “revamping”. The plan (ELKTON III) was ready by 26th April and with certain changes was approved by MacArthur and Halsey in Brisbane.

As previously indicated, MacArthur issued a warning instruction for the forthcoming operations on 6th May. “The general scheme of maneuver,” it said, “is to advance our bomber line towards Rabaul; first by improvement of presently occupied forward bases; secondly, by the occupation and implementation of air bases which can be secured without committing large forces; and then by the seizure and implementation of successive hostile airdromes.”9 Describing the direction of attack the instruction stated that

the general lines of attack will proceed along two axes. In the west, along the North-west New Guinea coast to seize Lae and secure airfields in the Markham River Valley, thence eastward to seize western New Britain airdromes. The advance along the New Guinea coast will continue to the seizure of Madang to protect our western flank. In the east, North-westward through the Solomons to seize southern Bougainville, including the airdromes of the Buin-Faisi area, neutralising or capturing airdromes on New Georgia. Later occupy Kieta and neutralise hostile airdromes in the vicinity of Buka Passage. All operations are preparatory to the eventual capture of Rabaul and the occupation of the Bismarck Archipelago.

With regard to the Australian operations MacArthur’s order stated:

The New Guinea Force, supported by Allied Air and Naval forces will:

(a) By airborne and overland operations through the Markham Valley and shore-to-shore operations westward along the north coast of New Guinea, seize Lae and Salamaua and secure in the Huon Peninsula-Markham Valley area, airdromes required for subsequent operations.

(b) By similar operations, seize the north coast of New Guinea to include Madang; defend Madang in order to protect the North-west flank of subsequent operations to the eastward.

While Halsey would occupy the Solomons including the southern part of Bougainville, the Sixth Army would:

(1) Occupy, by overwater operations, and defend Kiriwina and Woodlark Islands; establish airdromes thereon.

(2) Assume the responsibility for the defence of the island groups to the north of South-eastern New Guinea. Replace Australian ground troops on Goodenough Island by United States troops.

(3) Occupy western New Britain to include the general line Gasmata-Talasea by combined airborne and overwater operations and establish airdromes therein for subsequent operations against Rabaul.

By this stage General MacArthur had ensured that General Blamey would henceforth be the commander of “Allied Land Forces” only in name. Between February and April 1943 the headquarters of the Sixth American Army, mentioned above, arrived in Australia, although there were then only three American divisions in the area. General Blamey later wrote that “at no stage” was he given “any information as to the proposals [for the arrival of new American formations including the Sixth Army] or the development of the organisation”. Blamey considered that at this stage MacArthur “took upon himself the functions of Commander, Allied Land Forces” and his own functions were limited to command of the Australian Military Forces. This position was arrived at, beyond doubt, on 26th February when, with the object of placing Sixth Army, and thus the American corps and divisions, directly under the command of GHQ, Sixth Army was named “Alamo Force” and was given the status of a “task force” under MacArthur’s direct command. For this purpose MacArthur reconstituted “United States Army Forces in the Far East” (USAFFE), his command when in the Philippines, with himself as its commander, and orders went directly from USAFFE to the American formations.

In 1954 Major-General Charles A. Willoughby, MacArthur’s senior Intelligence officer in the SWPA, wrote:

The reasons for letting the Sixth Army operate in the field as the Alamo Force were never communicated to Krueger, but they were obviously bound up with international protocol: special task forces could undertake specific missions without complex inter-Allied command adjustments.10

Krueger’s own comments were:

The reasons for creating Alamo Force and having it, rather than Sixth Army, conduct operations were not divulged to me. But it was plain that this arrangement would obviate placing Sixth Army under the operational control of CG, Allied Land Forces, although that army formed part of those forces. Since CG, Allied Land Forces, likewise could not exercise administrative command over Sixth Army, it never came under his command at all.11

MacArthur did not consult the participating governments about this change as he should have done under the terms of his directive, nor did Blamey then raise the question with his own government, as he was entitled to do. Whether the procedure – or lack of it – was right or wrong, the new arrangement was probably the only one that, in the circumstances that had developed, would have been politically acceptable in Washington. The direction of the operations in the Pacific had been allotted to the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. Although a majority of its troops were Australian, MacArthur’s headquarters was not an Allied but an American organisation, although it received extensive specialist assistance from Australian staffs and individual officers. There were practical and psychological obstacles in the way of leaving an Australian commander in control of the Allied land forces in the field now that they included a substantial American contingent; and the Americans evidently considered that, if separate roles could be found for the Australian and the American Armies, difficulties inseparable from the coordination of forces possessing differing organisation and doctrines could be avoided.

When the Japanese entered the war General Krueger, the new army commander, had been in command of one of the four American armies – the Third – and from it he had drawn most of his staff for the Sixth Army.12 That staff had trained for a short period in Texas near Fort Alamo, which had gained fame in an American war with Mexico – hence “Alamo Force”. One of America’s most senior generals, Krueger was 62, German-born, cautious, tenacious and unexcitable. His previous war record included experience in the ranks during the American-Spanish war of 1898, as a junior officer in the Philippines insurrection of 1899-1903 and on the Mexican border in 1916, and as a staff officer in France in 1918.

Krueger set up his headquarters on 20th June at Milne Bay. On the same day Rear-Admiral Barbey flew in and hoisted his flag. Although there were many ribald tales about reconnaissance parties13 having a good time with the comely Trobriand girls, the American troops were not informed that there was little likelihood of any opposition on the islands of Kiriwina and Woodlark; Krueger wished his men to have the experience of carrying out the landings, the first big amphibious operation in the SWPA, under full combat conditions. And General Kenney, Vice-Admiral Carpender and Rear-Admiral Barbey did not expect that the landings would be undetected and intended to be ready at least for air

and naval reaction. As D-day was fixed for 30th June, however, it seemed that the landings would escape heavy opposition because of the more important landings at Nassau Bay and in the central Solomons, scheduled for the same day.

An advanced party of the 112th Cavalry Regiment made the landing on Woodlark Island from two destroyers on the night of the 22nd-23rd June. Ashore was Lieutenant Mollison,14 a coastwatcher of the Australian Navy, who had not been informed of the operation. Natives saw the invading force and warned Mollison who formed them up into a “skirmish line” about 100 yards inland. Hearing the landing troops speaking in American accents, however, Mollison joined the shore party without any accidents.

The same destroyers landed the advanced party of the 158th Regimental Combat Team on Kiriwina on 24th June. Again the landing might have been opposed by Australian troops who were stationed on Kiriwina to protect a radar station. The Australians had been told that the island would subsequently be occupied by United States troops but were not told when. Seeing only two destroyers they feared that the enemy had arrived to put off troops to oppose the American landing.

The main bodies of both forces landed on the night 30th June-1st July. On 16th July an RAAF aircraft landed on the newly constructed airstrip on Woodlark and by 23rd July the American 67th Fighter Squadron began operations from Woodlark. Four days later the Japanese bombed Woodlark for the first time and followed this by another raid on 1st August. The construction of an airfield on Kiriwina was delayed initially because of heavy rains, unexpected difficulties with roads, and the slow arrival of heavy constructional equipment, but by 19th August No. 79 Squadron, RAAF, was ready to begin operations from the island.

Kiriwina and Woodlark, however, never really paid dividends on the investment of effort. Although “planning was so thorough and comprehensive that the plans for movement of troops, supplies, and equipment in amphibious shipping became standing operating procedure for future in-vasions”,15 by the time the air bases were established the war had moved on and they were little more than “fixed carriers”16 too far behind the fighting front to play an impressive part in the battle.

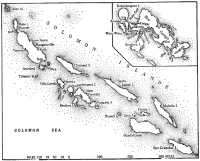

During his conference with MacArthur in Brisbane Halsey had explained his plan for moving north in the Solomons. New Georgia loomed as the next obstacle. MacArthur accepted Halsey’s view that the invasion of New Georgia should take place at the same time as the occupation of Kiriwina and Woodlark rather than after the establishment of bases on the Huon Peninsula as MacArthur’s staff had been advocating, and D-day was set at 15th May (later postponed to 30th June) to coincide with the Nassau Bay and island landings. Halsey was already building two

airfields on the Russell Islands, which had been taken unopposed on 21st February 1943 by the 43rd Division.

In March and April 1943 the 37th Division from Fiji had relieved the Americal Division on Guadalcanal, and at the end of May the division’s 148th Regiment had relieved the 43rd Division on the Russells. On the North-west tip of New Georgia the Japanese had hacked out Munda airfield; and on circular Kolombangara was Vila airstrip. Munda and Vila were among the bases from which the Japanese attacked Guadalcanal and Allied shipping in the Solomons area. Farther north was the enemy stronghold of Bougainville, the final objective, with its surrounding islands, Buka, the Treasurys, the Shortlands, and Ballale, all sheltering airfields and anchorages manned by large garrisons.

As a curtain raiser to the main attack on New Georgia and to aid a coastwatcher, Major Kennedy,17 who was being pressed by the Japanese, two companies of marines landed unopposed at Segi Point on New Georgia on 20th–21st June after receiving a cheerful “OK here” from Kennedy. Next day two companies of the 43rd Division landed. Six miles east of Munda in the rainy pre-dawn of 30th June (soon after other Americans had landed far to the west at Nassau Bay) a destroyer-transport and

minesweeper disembarked two companies on Sasavele and Baraulu Islands. At sunrise the 172nd Regiment landed on Rendova. Assisted by a party of Solomon Islanders under Major M. Clemens (of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force) the 172nd killed about a quarter of the Japanese garrison of 300 and chased the remainder inland.

Rendova was a stepping-stone for Munda. Without opposition on 2nd July the 169th and 172nd Regimental Combat Teams landed on New Georgia at Zanana ready to attack west towards Munda. To prevent the Japanese garrison on Kolombangara from reinforcing the Munda garrison, it was decided to land a force on the north coast of New Georgia with orders to secure Enogai Inlet, block the Munda-Bairoko trail and later to secure Bairoko harbour. For this task a force consisting of a battalion of marines and two battalions from the 37th Division (a total of 2,600 men) landed unopposed early on 5th July. Here they were greeted by a coastwatcher, Flight Lieutenant Corrigan18 (RAAF), who had organised a carrying party of 200 natives to help carry supplies inland. After some severe fighting the force captured Enogai on the 10th at a price of 51 dead and 76 wounded.

In the main battle area the 43rd Division was faring badly. By 9th July the 169th and 172nd Regiments were slowly advancing west against developing defences. To shorten the supply routes the 172nd secured a new beach-head 4,000 yards west of Zanana while the 169th struggled along the Munda trail. Stubborn resistance by the Japanese, who seemed to the Americans both elusive and ubiquitous, stopped the advance. Worse still the enemy infiltrated behind both regiments and cut the thinly held supply routes from Zanana. Under these circumstances, the hungry and sleepless division was in danger of defeat and urgently needed reinforcing.

The American commanders were becoming anxious. They controlled the air and sea and outnumbered the Japanese on the ground. “Rugged as jungle fighting is,” wrote Halsey later, “by now we should have been within reach of our objective, the airfield. Something was wrong.”19 On the 15th Major-General Oscar W. Griswold, the commanding general of XIV Corps, was placed in command. The original plan had allotted about 15,000 men to wipe out the 9,000 Japanese on New Georgia; by the time the island was secured, the Americans had sent in more than 50,000. “When I look back on ELKTON, the smoke of charred reputations still makes me cough,” wrote Halsey.20

When, on 11th July, the enemy drove a wedge between the two regiments of the 43rd Division, two regiments of the 37th Division – the 145th and 148th – were ordered to relieve the 169th Regiment and strengthen the tenuous American line. The 145th landed at Zanana on 16th July and the 148th on the 18th.

Fierce fighting continued throughout July, but after a long struggle the Japanese began to yield. On 1st August the 43rd Division reported

thankfully, “The going is easy.” All along the front on 2nd August the Americans advanced, and next day the Japanese commander ordered an evacuation. Enemy remnants still resisted but on the same day leading troops of the 43rd and 37th Divisions converged on the eastern edge of Munda while the 148th Regiment cut the Munda-Bairoko trail thus preventing the enemy troops withdrawing along it. On the 5th organised resistance lessened and American infantry and tanks moved into Munda unopposed. By the time four New Zealand aircraft landed on Munda airfield on 13th August the enemy remnants had fled from the island.

To seize Arundel Island, the stopper in the bottom of Kula Gulf, Griswold landed the tired 172nd Regiment on 27th August. Reinforced from Vila the Japanese fought back and it was not until 20th September that the 172nd, reinforced by 2 battalions and 13 tanks, captured Arundel for the loss of 44 dead and 256 wounded.

In order to isolate Kolombangara, Nimitz had suggested to Halsey on 11th July that he should land troops on Vella Lavella to the North-west and thus bypass it. Until this time neither side had been much interested in Vella Lavella, but with the capture of New Georgia both began to cast eyes in its direction. On 15th August the 35th Regimental Combat Team (25th Division) landed unopposed. The Japanese regarded the landing on Vella Lavella as a threat to the evacuation of Kolombangara. On 19th August a mixed army and navy force of about 390 men from Buin landed at Horoniu on the North-east of Vella Lavella where a barge base was established. On 4th September, the Americans, slowly advancing towards Horoniu, first skirmished with the Japanese and captured a plan of the defences. Ten days later the barge depot was captured and, on 18th September, Major-General Barrowclough’s21 3rd New Zealand Division relieved, with one brigade, the 35th Regiment. It completed the destruction of the enemy on Vella Lavella by 9th October.

“The Central Solomons campaign ranks with Guadalcanal and Buna-Gona for intensity of human tribulation,” wrote the American naval historian. “We had Munda, and we needed it for the next move, toward Rabaul; but we certainly took it the hard way. The strategy and tactics of the New Georgia campaign were among the least successful of any Allied campaign in the Pacific.”22 New Georgia had indeed been a lengthy and costly affair. It was planned to capture the island with one division but elements of four divisions were eventually used. American casualties totalled 1,094 dead and 3,873 wounded. A count of enemy dead, not including Vella Lavella, totalled 2,483. But on Vella Lavella and New Georgia four airfields brought all Bougainville within range of Allied fighters.

Meanwhile, in May, the Americans had opened an offensive against the Japanese northern flank in the Aleutians where, in June 1942, the

Japanese had placed garrisons on the islands of Attu and Kiska. The 7th American Division was landed on Attu on 11th May and after 20 days of fighting, in which about 600 Americans and 2,350 Japanese were killed, they secured the island.

Planning immediately began for an attack on the more formidable base of Kiska where the enemy had built roads, submarine pens, a seaplane base and a modern airfield. American submarines and the Eleventh Air Force maintained a continual attack on the island until August. On 22nd July the air force and a task force heavily bombarded the island. Next day a dense arctic fog-bank descended for a week. Realising the hopelessness of their positions on Kiska after the capture of Attu, Japanese transports sneaked into Kiska and removed the garrison (about 10,000) by 28th July. When a powerful force, consisting of three American regimental combat teams and the 13th Canadian Brigade, landed on 14th August they found only an abandoned base, and insults scribbled on the walls.

Meanwhile the Australian Army was entering upon the largest offensive operation yet undertaken by the Allies in the Pacific (having regard both to the size of the opposing forces and the area to be involved). That army was still having difficulty, however, in maintaining its strength. On 13th July the War Cabinet reaffirmed that three divisions must be maintained for the offensive operations planned by MacArthur, and also that there must be “adequate forces” for the defence of Australia and New Guinea. At the same time the army was receiving only 4,000 male and 1,000 female recruits a month, and General Blamey had already pointed out that this was not enough to maintain the existing formations.23 The War Cabinet also decided in July that the force on the mainland should be reduced by one infantry division within the next six months and, if the AIF corps was employed in an offensive role for a period of 12 months, by the equivalent of a further division. In the event, as already narrated, the 2nd Motor Division ceased to exist, leaving the 6th, 7th, 9th, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 11th and 12th Divisions (and the 1st, a purely training division), the 1st and 3rd Armoured.24

The army’s commitments had now been increased in the Torres Strait-Merauke area. On 6th May MacArthur had ordered Blamey to “augment

the Torres Strait garrison by one brigade group and such divisional troops as are necessary to bring the strength of this area, including Merauke [in Dutch New Guinea] to approximately one composite division”. In accordance with this instruction the 4th Division, consisting now of two brigades, provided the troops for York Peninsula, Torres Strait and Merauke. Japanese aircraft attacked the remote garrison at Merauke fairly frequently and long-range patrols had some clashes with Japanese patrols, as will be described later.

It was evident that for the remainder of the war the Australian Army would be used entirely against the Japanese in the Pacific. In order to prevent any repetition of the mistakes of sending inadequately trained units to fight in New Guinea the Australian Army was now being trained in a common mould. As mentioned in the previous volume, the Atherton Tableland in northern Queensland had been selected as a training ground for divisions destined to fight in the islands to the north. When Blamey first ordered a reconnaissance of the Atherton Tableland in November 1942 with a view to locating three divisions plus hospitals and convalescent depots there he had in mind the desirability of being able to bring troops forward to New Guinea more rapidly than hitherto, and the fact that rugged jungle country suitable for training was available on the tableland. Four officers made a thorough examination of the area, where already more than 5,000 troops were located, and selected a number of sites in the relatively dry western belt of the tableland. They recommended that only two divisions be placed on the tableland in view of the limitations imposed by the wet season, water supply and communications, and the third in the Townsville-Charters Towers area. Finally, however, accommodation was provided for more than 70,000 troops. From the point of view of the troops a big disadvantage of Atherton was its distance from the pleasures of the city. (The Americans were treated more kindly in this regard. In December 1942 when the 1st Marine Division from Guadalcanal arrived at Brisbane they found their camp there too uncomfortable and were moved to Mount Martha near Melbourne.) From early in 1943 when the 7th Division and the 16th Brigade began to arrive at Atherton, nearly all malaria-infected units returning from service in New Guinea were sent there for anti-malarial treatment before going on leave, and after leave the units usually returned to Atherton for training.

While these units returning from New Guinea were stationed at Atherton, new recruits were trained under rugged conditions at Canungra in the Macpherson Ranges, where the climate was less hospitable, but where jungle conditions were available near by. On 3rd November 1942 Army Headquarters had ordered the formation of an “LHQ Training Centre (Jungle Warfare)” at Canungra. At this time it was decided that Canungra would consist of a reinforcement training centre, an Independent Company training centre, and a tactical school. With the establishment of Canungra the Independent Company training centre on Wilson’s Promontory, where much money had been spent on camps and training facilities during 1941 and 1942, was abandoned.

The first troops to arrive at Canungra, on 27th November 1942, were the advanced party of the Independent Company troops from Wilson’s Promontory. On 3rd December the first draft of infantry reinforcements arrived for training. At the end of December there were 96 officers and 1,279 men in training, and the first draft of 218 trained men marched out to units. By the end of April there were 164 officers and 3,320 men in camp.

By May 1943 the Canungra training centre consisted of an advanced reinforcement training centre for jungle warfare, a Commando Training Battalion, and any Independent Company that was re-forming or refitting.25 The infantry training centre was training reinforcements for all combat units except signals. Men trained to a “normal draft priority 1 standard” (known as DP1’s) were received at Canungra from Australian training camps, and were given an extra four weeks’ training in jungle warfare before being sent forward. There were 2,000 reinforcements organised in eight training companies; 500 were received each week and 500 sent forward each week. The Commando Training Battalion trained reinforcements for the seven Independent Companies.

Canungra training was tough and realistic in the extreme. The concept was that the men should live and train under conditions as near as possible to those of active service. The reinforcements were ruthlessly disciplined, put through a hard physical fitness test, and given confidence in themselves and their weapons. With practically no amenities except for a canteen day and picture night once a week, and no leave except compassionate, the men were rigorously trained for 12 hours on each of six days and six nights each week for three weeks. For the fourth week they were sent into the deep and rough Macpherson bush, which closely resembled that of New Guinea, on a six-day exercise in which they carried their own food. If the men qualified on this final test they were passed out as fit for jungle warfare. The training for the Independent Company reinforcements was even more strenuous and covered a period of eight weeks in much the same way.

Canungra also trained 60 new officers from the Officer Cadet Training Unit (OCTU) each six weeks in the duties of a platoon commander in jungle warfare. Many of the instructors had seen service in the Middle East and South-West Pacific. It was made plain to the instructors that no man would move forward until he had reached a satisfactory standard of training. The test of a trainee’s suitability would be, “If you were in the firing line and needed a reinforcement would you have him?” Canungra, commanded from January 1943 by Lieut-Colonel “Bandy” MacDonald,26 helped enormously to create a finely trained army.

After receiving MacArthur’s warning order of 6th May Blamey issued his own plan which he described thus in his report:

On 17th May 1943, from my headquarters in Brisbane, an order was issued giving in brief detail the method by which the task allotted New Guinea Force would be conducted. The seizure of the airfields in the Markham Valley involved, as a primary stage, the capture of the enemy base at Lae and this was to be carried out by two divisions: 9 Aust Div by a landing from the sea; 7 Aust Div by an overland advance down the Markham Valley. Planning for the operation was to be carried out conjointly by the Staff at my Advanced Headquarters in Brisbane and by the Headquarters staff of New Guinea Force at Port Moresby. Plans were to be completed in time to enable the launching of the operation on 1 August 1943 and arrangements were to be made for the move to New Guinea of portion of my Advanced Headquarters about fourteen days before the operation was to begin. On its arrival, the Commander of New Guinea Force was to establish a forward headquarters from which to control the activities of the Australian Corps, while I personally exercised command over the complete operation with my headquarters located at Port Moresby.27

Blamey arrived in Brisbane on 15th May and on the 16th he and Generals Herring and Berryman had the long conference mentioned earlier. It was because they had contemplated at this time that the 9th Division would be carried in the small craft of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade that Nassau Bay, about 60 miles from Lae, had been selected as a staging point. Thus the present plans for the 3rd Division had been tied in with future plans for the 9th. As already narrated Herring carried Blamey’s orders with him to Port Moresby on 22nd May.

In the new phase the acquisition and accommodation of adequate shipping would obviously be a major problem. To relieve congestion at Oro Bay where stores for the American air squadrons at Dobodura were accumulating, Herring decided to open a port at Buna for handling Australian requirements. Delays were caused because of the difficulty in obtaining a ship suitable for the transport of long piles for building a wharf. Attempts to obtain landing craft to unload the ships at anchor in the roadstead were unsuccessful in June because the craft were being used at Woodlark and Kiriwina. By 22nd July, however, when the first ship arrived at Buna, a few landing craft had been collected. Supplemented by some amphibious trucks (DUKWS), which arrived on the next ship, the Buna port boasted 22 landing craft on 21st August. With the completion of the wharf, shallow-draught coastal vessels unloaded there, while Liberty ships were unloaded into the landing craft until sufficiently reduced loads enabled them to tie up at the wharf. Morobe was also prepared as a base for the Americans who were to invade New Britain.

At the end of July Blamey asked MacArthur to begin the offensive on 27th August when the phase of the moon would be most suitable. MacArthur agreed and directed that the requirements of the offensive should receive first priority. Admiral Carpender took control of the water transportation system north of Buna; landing craft were withdrawn from Woodlark and Kiriwina for use along the North-east coast; small craft

and amphibious trucks from Milne Bay were moved to Oro Bay and Buna; more troops were used for unloading; ships for maintaining Merauke Force were diverted; and the convoy system was revised to increase the speed of transport.

Describing this period Blamey wrote:

These measures effected considerable improvement but as the target date approached it became obvious that complete readiness for the operation would not be obtained. The strategic position was such, however, that to delay the operation until the administrative position was entirely complete, would have granted the Japanese the time necessary to reinforce his forward troops and improve his general situation. I therefore decided to begin the offensive early in September when the administrative position would be capable of supporting the initial stages of the operation and of rapid expansion immediately afterwards.28

Blamey counted on a close association between the two AIF divisions assigned to capture Lae and the Fifth Air Force. “The fulfilment of the offensive plan,” he wrote, “contemplated the establishment of air superiority, the softening of enemy resistance by continued air attacks on the successive objectives of the land forces, and, by attacking enemy shipping, forward bases and airfields, the interruption to reinforcement and supply of enemy forces.” The main enemy bases at Rabaul, Wewak, Madang and western New Britain were within range of medium bombers. In order to give fighter protection to these bombers and to provide close support in the early stages of the movement into the Lae–Markham Valley area, airfields had to be developed in the Watut Valley and an emergency landing ground established on the Bena Bena plateau.

Early in 1943 Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo had decided to pursue a policy of “active defence” in the Solomons and to reinforce New Guinea for an “aggressive offensive”. General Imamura in Rabaul therefore ordered General Adachi of the XVIII Army to strengthen Lae, Salamaua, Wewak and Madang, and in January and February the 20th and 41st Divisions were sent to Wewak from Palau. The Japanese were determined not to yield “an operational route for the proclaimed Philippines invasion”. Imamura had emphasised to Adachi in April the importance of Lae and Salamaua, the building of a road from Madang to Lae and the establishment of coastal barge services from New Britain to Lae and Salamaua. In June Adachi was ordered to strengthen Finschhafen and prepare to capture Australian outposts and patrol bases at Wau, Bena Bena and Mount Hagen, as well as infiltrating up the Ramu and Sepik Rivers. The general idea was to prepare for an offensive in 1944. Without control of sea and air, however, and in the face of the gathering momentum of the Allied offensive, this resolve was bound to be but a pipe dream.

In New Guinea Adachi’s army was then distributed thus – the 51st Division in the Lae–Salamaua area, the 41st in the Wewak area and the 20th in the Madang-Wewak area. The main role of the force at Madang was to build the road through the upland valleys to Lae. Across the border in Dutch New Guinea the XIX Army was occupying positions along the coastline from the Vogelkop Peninsula to Hollandia. In the Solomons the XVII Army, consisting now mainly of the 6th Division, was responsible for Bougainville; the 38th Division and, from September, the 17th were in New Britain under Imamura’s direct control. While the Army was responsible for the northern Solomons the Navy – South Eastern Fleet (X1 Air Fleet and Eighth Fleet) – under command of Vice-Admiral Jinichi Kusaka was responsible

for the central Solomons where the 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force (6th Kure and 7th Yokosuka SNLF’s) was garrisoning New Georgia, and the 7th Santa Isabel Island. The naval troops on New Georgia were later reinforced by army troops – the South-Eastern Detachment.

The slow but sure Allied advance in New Guinea and the Solomons around mid-1943 compelled the Japanese leaders to take some counter-action. They decided to reinforce the area with another air division. Accordingly the 7th Air Division in the Netherlands East Indies was transferred from the Southern Army to the Eighth Area Army. From June onwards its aircraft began to arrive in New Guinea. To coordinate the operations of the 6th and 7th Air Divisions a Fourth Air Army Headquarters (under Lieut-General Kumaichi Teramoto) was established at Rabaul on 6th August. The 6th Air Division was to operate from Rabaul, the Admiralties, Wewak and Hansa Bay, while the 7th would develop rear bases at But, Boikin, Aitape and Hollandia. The tasks of the two air divisions were to cooperate directly with the XVIII Army and to a lesser extent with the XIX Army in the Banda Sea area. About a fortnight after Teramoto’s command was established, and just as a substantial number of planes were arriving in New Guinea, he lost practically the lot when, as mentioned, Allied air armadas attacked airfields in the Wewak area with devastating effect on 17th and 18th August.