Chapter 10: Before Lae

THROUGHOUT the early months of 1943 two experienced AIF divisions – the 9th and the 7th – were preparing for their roles in the coming offensive. As early as 2nd December 1942 General Morshead had cabled to General Blamey from Palestine: “Having regard to our future employment is there any particular form of training you wish us specially to practise?” Blamey had replied: “Re training. One. Combined training and opposed landings. Two. Jungle warfare.” This briefest and clearest of signals accurately forecast the 9th Division’s future.

After a triumphal review by General Alexander in Palestine, the 9th Division returned to Australia in February 1943. It was given three weeks leave, after which units of the division marched through the mainland capitals and received just acclaim from huge crowds; it re-formed in the Kairi area of the Atherton Tableland in April.

Soon after his return General Morshead was promoted to command of II Australian Corps, concentrated on the Atherton Tableland and consisting of the 7th and 9th Divisions and a brigade of the 6th. Here the jungle training of the 9th Division was intensified. Teams from the other two AIF divisions, each consisting of one officer and four or five men, were attached to each brigade of the 9th, while officers from the 9th were attached to the 6th and 7th for periods of about four weeks. The units began to “learn quickly the methods of applying the principles of war to jungle conditions”.1

After the promotion of Morshead, Brigadier G. F. Wootten was appointed to command the 9th Division. It would be no easy task for anyone coming from outside the division to step into the shoes of the man who had led the 9th through two arduous and honourable campaigns. Wootten brought to the 9th Division, however, not only some experience of the kind of fighting the 9th had been through in North Africa – his 18th Brigade had for a time formed part of the division in the siege of Tobruk – but much experience of the tropical warfare it was now entering, having led the 18th Brigade in the Milne Bay and Buna-Sanananda fighting. He was by far the senior infantry brigade commander in the AIF having succeeded Morshead in the 18th Brigade in February 1941.

The 9th Division, home after more than two years, took some time to settle down. Seldom had that elusive quality morale been higher in any division than in the 9th after El Alamein. For them it was St Crispin’s Day. As part of the Eighth Army they had seen fighting on a majestic scale – tanks deployed in hundreds, men in tens of thousands and great bombardments by hundreds of guns – and they had shared the great exhilaration of victory that comes from participation in a massive battle. And now the bottom seemed rather to have fallen out of things. To a feeling

of anti-climax and reaction after return home from the Middle East was added other more material troubles. In one brigade, for instance, about 5 per cent were absent without leave at the end of May. There were many influences at work and some were listed by a brigade commander: lack of amenities, contrast with the conditions enjoyed by militia units farther south and civilian employees in war industry, domestic worries including a number of unhappy matrimonial cases, reaction after home leave, discontent with the apparent unreality of some parts of Australia’s war effort, and contact with industrial unrest in New South Wales. In general, however, the majority of the men who were AWL were old offenders. The senior officers of the division soon discovered also that one of the penalties of service on their native soil was that they were subjected to frequent requests by Federal Ministers and others to do favours for this individual soldier or that.

The special problems of the period were soon left behind, however, although the special dog-barking or “Ho Ho” cry which characterised this phase remained with the 9th thereafter.2 Although it is probably quite true that the 9th never quite recaptured the élan of the El Alamein period, the division soon began to recover from what one brigade commander later described as “this tremendous, sudden and almost frightening drop in morale”. The 9th Division was fortunate that it was not required, as the 6th and the 7th had been in 1942, to transfer large batches of officers and NCOs to militia units, which now and until the end of the war were led chiefly by former officers of the 6th and 7th Divisions.

As plans for the coming offensive took shape the 9th began amphibious training, a new and fascinating experience for Australian soldiers, even though some of the officers and NCOs had attended a British school of amphibious warfare on the shores of the Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal area. On 27th May, only three weeks after General MacArthur had issued his orders for the New Guinea offensive, Major-General Wootten conferred with Brigadier-General William F. Heavey, the commander of the American 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, about amphibious training. After further conferences with General Morshead and his senior staff officer, Brigadier Wells,3 three liaison officers from the boat and shore battalions of Colonel John J. F. Steiner’s 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment were attached to the 9th Division for amphibious training. This engineer amphibian force was equipped to move one infantry brigade at a time in shore-to-shore operations over a distance not exceeding 60 miles, and to establish, protect and maintain a beach-head.

The first Australian troops to undertake amphibian exercises – the 24th Brigade – arrived at Deadman’s Gully near Trinity Beach north of Cairns on 16th June for a fortnight’s training in shore-to-shore operations. Describing this training the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade’s historian wrote:

When the Amphibs heard that they were going to work with the famous 9th Australian Division (the “Rats of Tobruk”) in impending amphibian operations in New Guinea, they took hold with renewed vigor and determination. These veteran AIF troops who had performed so admirably in the defense of Tobruk against Nazis, Fascisti, and desert sands had won every Amphib’s confidence long before actual training began.4

The 20th Brigade took over from the 24th on 4th July. Unfortunately there was no time for the 26th Brigade to practise amphibious operations effectively, because, when its turn came at the end of July, the division was on its way north.

The mishaps to the small landing craft in the Nassau Bay operation, and the loss of surprise likely to result from the assembly of about 400 landing craft within 60 miles of the objective, caused Blamey and Herring to seek better means of transporting a whole division and at the same time maintaining the element of surprise. By 21st May Blamey’s misgivings were such that he discussed the problem with MacArthur, emphasising the need to provide sufficient craft to move the whole 9th Division at once. Because this task was beyond the capacity of the ESB, and because of the hazards apparent in the use of Nassau Bay as the starting base, the Australian and American planners, now meeting weekly, began to contemplate using also the larger vessels of the Amphibious Force of the Seventh Fleet.

MacArthur’s staff had planned that the main attack would come from the Markham Valley with a secondary one (by one brigade only) from the coast east of Lae. The Americans now found that Blamey’s idea was that the main effort should be the landing of a whole division east of Lae, followed by an overland and airborne movement into the Markham Valley. Blamey therefore requested, in addition to the Engineer Special Brigade, 17 LCIs and 3 LSTs, or 15 LCTs. If this was agreed to there would be two forces – one from the army and one from the navy – with much the same sort of equipment, operating in the same area. After a careful evaluation of advantages and disadvantages, the planners of the “G3” section of GHQ recommended to MacArthur on 25th May that, for the sake of simplicity of command, the ESB should be placed under the operational control of the Amphibious Force, but for the Lae operation only.5 For later shore operations along the coast the Commander of the Allied Naval Forces would be authorised to pass elements of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade to the command of New Guinea Force. The naval commander would be responsible for the amphibious training of the 9th Division.

In Brisbane on 27th June Blamey was assured by Admiral Carpender that the whole of Barbey’s Amphibious Force planning staff would soon move to New Guinea so that joint planning could take place. On 11th July in Port Moresby Blamey discussed with Herring, Barbey and Wootten his outline plan for the movement of the 9th Division in the larger craft of Barbey’s task force.

“This,” wrote Herring later, “... involved a complete change in plan. As a result of the conference the following outline plan was submitted for the approval of the appropriate commanders. 9 Aust Div was to be brought to Milne Bay for training and rehearsal with Amphforce craft. On the appropriate date the assaulting brigades were to go direct from Milne Bay to the landing beach, while the reserve brigade, having done its training at Milne Bay was to be transferred some days before the operation to Buna and held there ready to be moved on the night of D+1/D+2.”6 In Herring’s plan “the task of the 2 ESB was ... limited to the transport of one shore battalion in their small craft from the base in the Morobe area. The craft carrying the shore battalion to the landing beach were to remain there and come under command of 9 Aust Div, for movement of men, equipment and supplies along the coast.” The main result of the change in plan was to render unnecessary any further development of staging bases along the coast. With its larger craft Amphforce needed only one port between Milne Bay and Lae. Buna was selected as the most suitable port and was speedily developed.

At the Port Moresby conference Wootten and his principal staff officer, Lieut-Colonel Barham,7 learnt that the division would land on a beach east of Lae to be selected by Wootten and out of gun range of Lae. A joint planning headquarters (9th Division and Task Force 76 – the naval force in support) would be established at Milne Bay where the planning staffs of the three Services would live together. Wootten’s planning headquarters flew to Milne Bay on 20th and 21st July but because the naval staff remained on their headquarters ship, Rigel, eight miles away, intimate cooperation was not achieved, naval representation being spasmodic and uncertain at planning conferences.8

Between 26th July and 12th August the brigades of the 9th Division followed one another to Milne Bay in American and Australian ships, in the order in which Wootten had already decided they would land east of Lae–20th, 26th, 24th. “All ranks will immediately shave under the armpits and hair on heads will be close cropped”, ordered the routine orders of one battalion; another’s warned “the natives do not like being

called ‘George’. The correct term to use is ‘Boy’ “; while a third stated “a certain number of men inadequately trained are still expressing the opinion that taking of atebrin will result in loss of manhood. ... No case of loss of virility from taking atebrin has yet been recorded in scientific circles.”

In its period of general training and re-forming in the Ravenshoe area of the Atherton Tableland the 7th Division had faced different problems from those confronting the 9th. The 7th needed no introduction to jungle warfare. When he returned from leave and sickness to resume command on 18th April Major-General Vasey found the division greatly below strength because of battle casualties in the Papuan campaign and recurring malaria. The 21st Brigade, for instance, had only 57 officers and 1,066 men whereas its war establishment was 119 officers and 2,415 men. As late as June the 18th Brigade had only 44 per cent of its authorised strength and was considered unfit for service without further training and reorganisation. By 10th July this brigade had absorbed 51 officers and 1,239 men from the 1st Motor Brigade then being disbanded. During April, May and June the brigades trained hard and in mid-July took part in a divisional exercise.

Camped at Gordonvale was Colonel Kenneth H. Kinsler’s 503rd American Parachute Regiment. As early as 11th May Kinsler had provided a demonstration and inspection of equipment for Vasey and the three infantry brigadiers. MacArthur’s headquarters on 19th June authorised Kinsler’s parachute regiment to train with the II Corps and several exercises were carried out. Wishing to discuss the lessons of the Crete campaign with Brigadier I. N. Dougherty, who had commanded a battalion in the successful defence of Heraklion against German paratroops, Kinsler adopted the unusual method of arriving by parachute on the Ravenshoe golf links.

For the attack on Lae Blamey intended that the 7th Division would play second fiddle to the 9th which would actually capture Lae. He wrote later:

The introduction of a force simultaneously into the Markham Valley was primarily to prevent reinforcement of the Japanese garrison at Lae. This would be carried out by interposing a force of sufficient size across the enemy’s overland line of communication between Madang and Lae. When this had been done, an offensive operation would be carried out against Lae from the North-west to assist that which was to be made along the coast by the 9 Aust Div. Then, with a port and airfields in our possession, 7 Aust Div would be free to expand towards the north of the Markham Valley to secure or construct airfields.9

Blamey hoped that the 7th Division would be based early in the Bulolo Valley. Its advance from there into the Markham Valley would involve crossing the Markham River, no easy task, and a “serious defile” as be termed it. It would be necessary therefore to establish an air base north of the Markham as soon as possible after the launching of the offensive.

There were many sites in the extensive Markham flats, and there were also a number of small overgrown pre-war landing grounds. Seizure of one of these would reduce the effort and accelerate the preparation of an airfield suitable for large transport aircraft. About 20 miles North-west of Lae was the old landing ground at Nadzab, which Blamey decided to seize.

The concentration of the 7th Division in the Bulolo Valley would involve movement of troops and supplies into an area which had no land or sea line of communication with Allied bases. As maintenance of the 3rd Division already made large demands on the limited number of transport aircraft available for crossing the mountains, it was hoped to use the Bulldog–Wau road to move troops and supplies into the Bulolo Valley and a road from Sunshine to move them thence to the Markham. Delays caused by equipment shortages and the rugged nature of the country led Blamey on 21st May to inform MacArthur that his ability to launch the 7th Division’s offensive was dependent on the completion of the Bulldog Road.

On 17th June MacArthur agreed to provide an American parachute battalion to capture Nadzab after which an Australian brigade would move into the area either in air transports or overland from the Bulolo Valley. Blamey’s outline plan provided that, in addition, an infantry brigade group would move overland through the Bulolo Valley to reach the Markham River before the airborne landing and would be available as a reserve.

On 8th July the 25th Brigade was warned to be ready for movement. By 20th July most of the brigade had sailed, in troopships well known to Australian soldiers moving to and from New Guinea – Duntroon, Taroona and Canberra. The remainder arrived at Port Moresby on 26th July aboard the Katoomba. The 21st Brigade followed at the beginning of August, and the 18th had arrived at Port Moresby by the 12th.

By the time his advanced headquarters arrived in Port Moresby on 25th July, Vasey already expected that it would be necessary for his entire division to be transported north of the Markham by air.10 On 25th July he attended a conference at New Guinea Force. There Blamey outlined the plan and Barbey and Wootten said they would be ready by 27th August. Blamey had ascertained that the airfields in the Watut Valley would be capable of accommodating two fighter squadrons in early August, and that twin-engined fighter groups would be established at Dobodura by mid-August. Air support for the Nadzab operation would thus be assured, but as air operations depended so much on weather a firm date such as that suggested for the seaborne assault could not be guaranteed. Blamey was now convinced that two infantry brigade groups must be used at Nadzab, but because of delay in opening the Bulldog–Wau

road, he thought that it might be necessary to fly the second brigade into the Bulolo Valley.11

Already Vasey was capturing the imagination of the men of the AIF as perhaps no other commander was to do. Lean, highly-strung and learned, he now had more experience as a field commander than any of his contemporaries in the regular officer corps. Like Wootten, Vasey would have close association with a particular American unit – in his case the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment; like Dougherty, Vasey had served against German paratroops in Crete. At the Port Moresby conference on 25th July Vasey had said that he doubted whether one parachute battalion was sufficient to seize and prepare landing strips capable of taking two brigades, which he considered the minimum force required for his task. On 31st July he suggested to Colonel Kinsler the use of the whole regiment (2,000 men) because of the nature of the Nadzab flats and the extensive front which the parachutists would have to cover; and on 2nd August he wrote to Herring asking that the strength of the paratroops be increased from one battalion to one regiment, that Australian engineer paratroops be attached to the American regiment for the operation, and the greatest possible number of gliders be made available and used (to carry engineers and their equipment).12 By 23rd August the entire parachute regiment had been transported with great secrecy to Port Moresby.

Vasey, however, was still not convinced that the regiment, by itself, could secure the Nadzab strip against possible opposition and then develop it. He therefore proposed that one of his brigades should be flown to Bulolo or Tsili Tsili some days before the operation, cross the Markham just after the airstrip had been seized by the paratroops, and assist in its preparation.

He immediately set about finding suitable crossings of the Markham. Thus, at the end of July, parties led by Captain K. Power of the 2/33rd Battalion and Captain D. L. Cox of the 2/25th reconnoitred north from Tsili Tsili and Sunshine respectively to the Markham.

To help the paratroops construct the airstrips Vasey now decided to move the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion and 2/6th Field Company overland from Tsili Tsili and across the Markham to Nadzab on the day of the landing. On 6th August he ordered Lieut-Colonel Lang13 of the 2/2nd Pioneers to provide a patrol to reconnoitre the track Marilinan-Babwuf-Waime-Naragooma-Kirkland’s Dump. The patrol’s tasks would include finding a suitable crossing of the Watut near Tsili Tsili; reconnoitring a track east of the Watut to Kirkland’s which could be used by about 2,000 troops; finding a suitable concealed area near Kirkland’s to hide the troops, and recommending a suitable crossing of the Markham as well as the best means of crossing.

The patrol was led by Major Kidd14 of the Pioneers and included old New Guinea hands as well as representatives of the Pioneers and 2/6th Field Company. Kidd reached Kirkland’s Dump on 15th August and later submitted a report on which subsequent movement of the overland force was based.15

Meanwhile, between 3rd and 5th August, Lieutenant Merry16 of the 2/6th Field Company had floated in an assault boat down the Watut from Tsili Tsili to the junction of the Markham and Watut Rivers. He reported that the river was navigable in spite of sandbanks and snags, and provided the load in each boat did not exceed 2,000 pounds.

Damage caused to stores and equipment by careless handling and weather had been experienced by both the 9th and 7th Divisions in their movement from Australia to New Guinea. Stop-work meetings and go-slow tactics by the Cairns wharf labourers had delayed and confused the move of the 20th Brigade late in July. The 26th Brigade’s stores had been dumped in confusion on Stringer Beach early in August in pouring rain and with insufficient time for unloading ships. At Port Moresby unloading was carried out by troops no better than the loading at Cairns. During the unloading of the 21st Brigade’s stores at Port Moresby such delicate equipment as anti-tank guns, anti-aircraft guns and wireless equipment were dropped the last few feet on to the wharf. Crates burst open, and when the brigade officer detailed to prevent pilfering asked that more care be taken in the unloading of crates whose contents were valued at £2,000 each, the reply was “Righto, Mate”, and another crate slipped from the sling and crashed into the lighter below. No care was taken to place generators and predictors upright, as requested, in the lighters. Before the last of the 21st Brigade’s stores had been unloaded the holds were battened down and the ship sailed. Conditions were better at the bases on the North-east coast of Papua from which the attack would be launched – “one cannot say too much about the splendid planning, the speed with which those plans were put into effect and the spirit with which everyone set to work”.17

While the 24th Brigade was moving to Buna the 20th and 26th Brigades prepared for a practice landing from Barbey’s craft on two beaches on Normanby Island as similar as possible to those chosen east of Lae. The diarist of the 2/32nd Battalion, preparing to leave for Buna, wrote: “Should Jupiter Pluvius continue in his present vein, our camp will become

an ideal spot to conduct amphibious operations.” The real practice, however, took place, on 20th and 21st August and many valuable lessons were learned. The majority of the craft used were those actually to be employed for the real landing and consisted of “Assault Personnel Destroyers” (APDs), LCIs, LSTs and LCTs of Barbey’s Task Force and the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment.

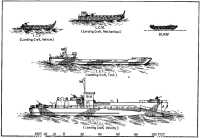

The craft which would carry the Australians to the landing beaches would be manned by the Americans, but, although probably few of the crews or the troops they carried realised it, the prototypes of many of these craft and others that were to land Americans and Australians on coast after coast northward towards Japan had been designed in Britain.

In the nineteen-thirties Japan led the Powers in the development of landing craft; from 1937 in China she used them on a scale not to be attained by any other Power until 1943. In Britain, in the ‘thirties, work on the design of landing craft was accelerated; and, when war broke out, a modest number of LCAs (Landing Craft, Assault) and LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanised) were being built there. The operations in Norway severely tested British landing craft and British staff work for combined operations; and the overrunning of France and the Low Countries compelled her to press on with improving the design and increasing the output of the landing craft without whose help her troops could not strike back against the Germans.

By 1941 some hundreds of “assault” and “mechanised” landing craft were being built, more than 100 larger LCTs (Landing Craft, Tank) were built or building, a number of LSIs (Landing Ships, Infantry – liners able to carry landing craft at their davits) were in use. Also LSTs (Landing Ships, Tank, vessels capable of landing through their bows 500 tons or more of tanks, vehicles and stores), had been built and tested, and other specialised craft were on the way. When the Pacific war began Britain gave large orders for these ships and craft in the United States, where the designs were adopted and mass production soon began on a scale unattainable in Britain, although in America some Service Chiefs had been “dubious about the need for landing ships and craft before Pearl Harbour”.18 In 1942, at the request of Admiral Mountbatten for a vessel able to carry about 200 men across the Channel and land them on a beach, a new and important type, the LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry) was designed. The Americans, faced with the need for craft which could run ashore on the coral-fringed beaches and swampy shores of the Pacific – problems not encountered in Europe – developed amphibian vehicles: for example, the LVT (Landing Vehicle, Tracked) and the DUKW (a lorry with a hull and propellers). A large number of other specialised types of ships and small craft for landing operations were developed by them as the war went on.

Rapid progress had been made in the planning and execution of amphibious expeditions as well as in their equipment since the experimental British seaborne raids by Independent Companies in 1940 and

Some Allied landing craft

1941. In August 1942 a force equal to a small division had been put ashore at Dieppe; in November there were the North African landings by large forces but against a defender who was not expected to offer a very sturdy or well-organised resistance; and in July 1943 came the invasion of Sicily, the largest seaborne operation so far.

In the Pacific the landings had generally been on a smaller scale. At Guadalcanal in August 1942 the 1st Marine Division had put more men ashore than were in the British-Canadian force which landed at Dieppe in the same month, but on a far less strongly defended shore. In June 1943 the Americans had landed on New Georgia. In the SWPA there had been the rehearsal landing of two regimental combat teams on Woodlark and Kiriwina in June, and the landing of one battalion combat team at Nassau Bay on a beach occupied by a party of Australian troops. The landing of the 9th Division east of Lae would be the largest amphibious operation yet undertaken in the South-West Pacific.

General Blamey’s instruction for the capture of the Lae–Nadzab area was issued on 30th July, and was followed on 9th August by General Herring’s orders. These stated that “New Guinea Force, in conjunction with 5 AF and US Task Force 76, will seize the area Lae–Nadzab with a view to establishing airfield facilities therein”. To carry out this order the 9th Division would capture Lae after landing east of Lae, while the 7th Division would “establish itself in the Markham Valley by overland and airborne operation”.

At Milne Bay Wootten continued his efforts to iron out the vital points of his plan with Barbey. For instance, when the two commanders lunched on Rigel on 2nd August, Wootten emphasised the necessity for carrying 10 days’ reserve rations on D-day, and also the need for a full-scale rehearsal. At another conference five days later (attended by Herring, Wootten, Barbey, Colonel M. C. Cooper of the Fifth Air Force and Air Commodore Hewitt19 of the RAAF) the date for D-day was postponed mainly because of shipping difficulties and because Barbey requested air cover over the landing beaches until at least noon on D-day. On 13th August Barbey agreed with Wootten that landing and unloading would proceed if enemy aircraft attacked the Task Force during the landing. Naturally Wootten was determined not to have his division dumped ashore inadequately loaded and supplied, and he therefore contested suggestions for doing the job quickly. On the 21st a long-standing argument was settled when Barbey said that he would not insist, as he had up to then, on LSTs being completely vehicle loaded. Bulk loading, which would take longer to unload, or a combination of bulk and vehicle loading might be used, as Wootten wished.

Thus planning – and argument – proceeded. At a conference with Herring, Wootten and Cooper on 19th August Barbey had insisted that unloading on D-day should cease by 11 a.m., not 1 p.m. as stated previously, because the large commitments of the Fifth Air Force in the airborne operation of the 7th Division would prevent air protection over the landing beaches for more than a limited period, and because it was considered unwise to expose the limited number of landing craft in the theatre to air attack and so jeopardise the success of future operations. Barbey also stated that as there would be no moon on the morning of 4th September, which had now been designated D-day, he would be unable to guarantee landing on the correct beaches until 20 minutes after sunrise at 6.30 a.m. “The time span for the landing was thereby reduced to 41 hours,” commented Wootten later, “which meant that after forward troops had been put ashore there would be a maximum time of three hours for unloading stores.”20

At this conference on the 19th Barbey insisted on an “air umbrella” all the way, and the air force stated that aircraft could not be kept aloft indefinitely but that radar would enable them to reach the spot quickly. Because the air force could not provide close support over the beaches until 7.15 a.m. on D-day, Wootten decided to dispense with bombing and strafing of the beaches immediately before the landing. As continuous a fighter cover as possible, however, would be provided during the approach to the landing beaches, during the landing, and during the return of the amphibious craft.

Wootten’s staff estimated that there were about 7,250 enemy troops, including 5,100 field troops in Lae, that the enemy had a large amount

of artillery, and that most defences were in and around Lae itself. By the time Wootten issued his operation order on 26th August, his brigadiers and battalion commanders were well acquainted with their tasks. The 9th Division’s landing would be preceded by a six-minute naval bombardment by five destroyers and would be carried out in three main groups. First, the 20th Brigade, supported by the 26th, would begin landing at 6.30 a.m. on 4th September on Red Beach. The 2/13th Battalion would land at the same time on Yellow Beach to the east to protect the eastern flank and secure an alternative beach-head if necessary. In this group of 7,800 troops, the first assaulting wave would be carried in the four APDs – capable of carrying assault landing craft as well as troops to man them. On arrival near the landing beaches the APDs would launch the craft carrying the first wave of infantry. The second group consisting of some 2,400 troops – rear details of the two brigades – with vehicles and bulk stores would land at 11 p.m. on 4th September, and the third, comprising the reserve brigade group, some 3,800 troops, would land on the night 5th–6th September. The boat and shore regiment would travel in their own craft from Morobe to join the first group, but all other troops and stores would be transported in and landed from Barbey’s larger landing craft.

The area chosen for the landing was in the vicinity of the Bulu Plantation, and on 19th August Lieutenant W. A. Money of Angau, the owner of that plantation, gave Brigadier Windeyer21 of the 20th Brigade and his battalion commanders a detailed description of the country. The area through which the 9th Division would advance consisted of a flat coastal plain averaging three miles in width before rising to the rugged foothills of the Rawlinson Range. West of the Burep River this plain broadened into the valleys of the Busu, Bumbu and Markham Rivers. About two miles and a half north of Lae the Busu and Bumbu were divided by the Atzera Range which dominated Lae. Dense jungle, interspersed with patches of kunai 8 to 10 feet high and mangrove swamps near the coast, covered the coastal plain. Between Red Beach and Lae, 16 miles away, the advancing division would have to cross five rivers and a large number of small streams. Swollen by the daily downpours of the rainy season22 the rivers were now fast-flowing, but, except for the Busu, which might present a problem, they were narrow with shallow banks and stony bottoms. There were no roads in the area, only native paths. The two landing beaches were about 20 yards wide and of firm black sand, but behind them was a swamp through which were few exits.

In Port Moresby Vasey was better situated than Wootten to maintain close liaison with the Americans, and during August he constantly conferred with them about details of the Nadzab landing. American cooperation enabled him to fly low over the Nadzab area in a Superfortress bomber on 7th August.

Meanwhile the units of the 7th Division were concentrating on acclimatisation and specialist training. The 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion, for example, practised with folding assault boats in the Laloki River, while the infantry battalions rehearsed the speedy loading and unloading of aircraft, assisted by a training film, “Loading the Douglas C-47”. Between 8th and 21st August Brigadier-General Ennis C. Whitehead, Deputy Commander of the Fifth Air Force, made five planes available each day at Ward’s and Jackson’s airfields for Vasey’s units to practise loading and unloading. Detailed movement tables were prepared and a great deal of research went into the operational loading of aircraft, particularly by Lieut-Colonel R. A. J. Tompson, the division’s Chief Engineer, and Lieut-Colonel Blyth23 of the 2/4th Field Regiment.

On 16th August Vasey wrote to Herring expressing his anxiety at the little equipment available to Tompson – one scoop, one ripper and one tractor on loan from New Guinea Force. By 26th August, however, Vasey was informed that the 871st United States Aviation Engineer Battalion would be placed under his command from that day. When the engineers of the 2/6th Field Company (Captain Dunphy24) saw the equipment of the 871st Battalion, their diarist was moved to write: “Their equipment (light mechanical earth moving equipment for air transport) was the envy of the company.”

In order to reduce any interruption due to bad weather Vasey decided to use Tsili Tsili as a forward staging field to which the leading elements of the airborne brigade would be moved the day before Z-day.25 Here also the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion and 2/6th Field Company arrived by air on 23rd and 24th August.

Vasey’s Intelligence staff estimated that there were about 6,420 enemy troops in Lae, including 4,780 field troops, slightly lesser numbers than those estimated by the 9th Division. This number, side by side with the 7,000 Japanese estimated by Herring’s staff to be in the Salamaua area, made understandable Vasey’s anxiety to have his fighting troops at Nadzab as soon as possible.

Vasey issued his plan on 27th August. Z-day would be 5th September, a date proposed by Vasey and Whitehead after taking into consideration the availability of fighter cover and the weather. The paratroops would jump over Nadzab at 10.30 a.m. under cover of a preliminary air attack and smoke screens placed by aircraft. The pioneers and engineers from Tsili Tsili would make a covered approach to the Markham on the previous day and cross to coincide with the paratroop attack. Vasey’s forward headquarters and the first troops of Brigadier K. W. Eather’s 25th Brigade would land at Tsili Tsili on 6th September and await the preparation of the Nadzab airfield before being ferried across by aircraft. When the airfield was ready, the 21st Brigade would move direct to Nadzab

from Port Moresby. Immediately after landing Eather would relieve Kinsler of his protective tasks, and, when a sufficient force had been landed to block the Markham Valley from the west, he would begin the advance towards Lae.

The Markham Valley runs North-west of Lae for about 80 miles. Gradually rising from sea level at Lae, it is about 1,200 feet above sea level at the Markham’s headwaters near Marawasa where the divide between the Markham and Ramu Valleys is so gradual as to give the impression that the two valleys are one. It was believed that in geological times the Markham and Ramu Valleys were beneath the sea, thus dividing New Guinea into two islands. Through the ages the Markham plains, varying in width from 6 to 12 miles, had been formed by rivers washing down huge quantities of alluvial gravel from the high ranges and then forming the Markham River on the extreme southern edge of the valley. The valley, being almost completely gravel, is infertile and covered with a stunted form of kangaroo grass, except where silt, deposited by smaller streams failing to reach the Markham, enables tall kunai to grow. It presents few obstacles east of Nadzab, although to the west there are Garambampon Creek and the Leron, Rumu and Erap Rivers, which could form natural obstacles during the rainy season. Militarily the Markham and Ramu Valleys were very important for they formed the easiest land route whereby Japanese reinforcements and supplies could reach Lae and Salamaua from Wewak and Madang, and were also suitable for the development of air bases needed to control Vitiaz Strait and to provide air cover for the land advance.

In a signal to Lieut-Colonel Smith of the 24th Battalion on 23rd August Herring had given an inkling of pending operations: “Essential for success our future plans that enemy Markham Point area be contained there and also any Japs withdrawing from Salamaua be prevented from joining this force.”

Captain Chalk, whose company of Papuans was patrolling northward from the Wampit towards the Markham, had been summoned to Port Moresby where he received his orders from Vasey on 25th August. Before Z-day the Papuan company would patrol the south bank of the Markham from Mount Ngaroneno to the junction of the Watut and Markham to prevent natives seeing Australian activity on the track between Babwuf and Kirkland’s Dump surveyed by Kidd’s patrol. On Z-day Chalk would cross the Markham and ensure adequate warning of any enemy movement towards Nadzab from the west or north. To preserve secrecy Chalk was instructed not to discuss operations in the hearing of his native soldiers but to tell them that a Japanese crossing of the river was feared. When Chalk returned from Port Moresby on 27th August he carried also secret instructions for Smith to attack Markham Point with at least one company at first light on Z-day with the object of destroying the enemy south of the Markham and preventing any Japanese from the Salamaua area using the river crossings near Markham Point.

Meanwhile the air and naval forces were playing their parts in weakening the enemy. During August the air force attacked Lae, Salamaua and Finschhafen as well as flying deep into enemy territory to attack Wewak and Madang. Along the coast they hunted Japanese barges. Whitehead informed Kenney at the end of July that over 100 barges had been sunk that month, that the pilots were becoming expert at finding them in spite of elaborate camouflage, and that he expected good hunting in August. The tempo was set for the month when, on the 2nd, 23 Mitchells claimed 13 barges along the Rai Coast and the coast of the Huon Peninsula.

Kenney pointed out to MacArthur that, as he did not have enough air strength to handle the Japanese air forces at both Wewak and Rabaul, he proposed concentrating on the airfields in the Wewak area until the landing of the 9th Division. This policy culminated in the pulverising raids on 17th and 18th August which crippled the Japanese air force in New Guinea for the time being. Although barge hunting was not quite so profitable in the last two weeks of August, the aircrews reported the destruction of 57 and damage to about 60 others.

Barbey’s patrol torpedo boats, from their forward base at Morobe, took over the barge hunting from the airmen at sunset each day. They were particularly active in Vitiaz Strait and in ambushing the Finschhafen-Lae supply line. These small venomous craft became so expert at finding the enemy barges that a Japanese diarist at Finschhafen wrote that on 29th August he had made the only trip “when barges were not attacked by torpedo boats”; his barge was sunk on its return journey. However, in spite of the vigilance of the PTs (as the torpedo boats were known) seven Japanese submarine missions managed to land, in July, 195 men and 238 tons of supplies, while on 2nd and 5th August two destroyer-transports landed 1,560 troops and 150 tons of supplies at Cape Gloucester, a good springboard for New Guinea.

MacArthur informed Blamey on 20th August that there was evidence that the Japanese were planning to reinforce Salamaua, using landing barges that had recently arrived at Finschhafen, and that he had ordered the naval forces to make a sweep through the Huon Gulf. That day Vice-Admiral Carpender ordered Captain Jesse H. Carter to take four destroyers to “make a sweep of Huon Gulf – during darkness 22-23 August and follow this with a bombardment of Finschhafen”.26 For the first time in the New Guinea ground fighting a naval bombardment was scheduled. Although any damage caused by 540 shells fired by Carter’s destroyers into Finschhafen was not observed, one of Carpender’s staff remarked: “It will be worthwhile to prove the Navy is willing to pitch in, even if we get nothing but coconuts.”

The Japanese were now becoming more active in the air, and since the beginning of September their planes had been met in substantial numbers over Wewak and Cape Gloucester. At noon on the 3rd 9 enemy bombers and 6 fighters attacked Morobe, but without damage and with only one casualty. Because Lae and Cape Gloucester bad been heavily bombed

that day, the Allied air force was mystified as to where these aircraft came from. Kenney would have been surprised had he known that, in spite of what he termed “a farewell slugging with 23 heavy bombers, unloading 84 tons of bombs” on Lae, 3 bombers and 6 fighters had slipped undetected into Lae that afternoon and remained there for the night, apparently destined for Morobe next day.

Final discussions between the navy and the air force, hampered by the absence from Milne Bay of any air force representative with sufficient authority to make definite decisions, centred on Barbey’s desire for an “air umbrella” or continuous coverage. Kenney undertook “to place the maximum number of fighter aircraft in the Lae vicinity on a continuous wave basis”, and promised that reserve aircraft would be held on ground alert to support Barbey. Pressed further by the navy, Kenney finally agreed to provide a 32-plane cover over the task force as continuously as possible through daylight hours.

The two fighter control sectors, based on Dobodura and Tsili Tsili, did not have a complete radar coverage of the seas through which the convoy would proceed. It was believed that enemy aircraft could fly behind the mountains from Wewak and Madang towards Lae and others could fly across Vitiaz Strait from New Britain without being picked up until too late. To cover this gap the RAAF suggested that a destroyer, equipped with radar and radio, should be posted between Lae and Finschhafen to give adequate warning. This suggestion was adopted and the American destroyer Reid sailed to take up its station 45 miles South-east of Finschhafen.

In preparation for the coming offensive the machinery for the command of the forces in New Guinea was overhauled. Early in August the main part of New Guinea Force headquarters had been at Port Moresby with an advanced headquarters at Dobodura. On 25th August Blamey separated the two headquarters. Herring would remain at Dobodura, but now as commander only of I Corps, which would comprise the 7th, 9th, 5th and 11th Divisions, the 4th Brigade, and Wampit Force.27 The command of New Guinea Force would pass to Blamey himself. It would control, in addition to I Corps, the 3rd Division, Bena Force, Tsili Tsili Force, the Port Moresby and Milne Bay bases, the advanced base ready to move into Lae, and Angau.

Blamey evidently decided that it would not be advisable for the Commander-in-Chief, Allied Land Forces, to act also as commander of New Guinea Force and soon again brought forward the veteran Mackay as “temporary GOC New Guinea Force”,28 and revived the device of ap-

pointing his own Deputy Chief of the General Staff, General Berryman, to be also Mackay’s Chief of Staff.

Under the new organisation General Morshead, recently returned from the Middle East, remained at Atherton commanding II Corps which had originally comprised the three AIF divisions but now consisted of little more than two brigades of the 6th Division. Meanwhile at Toowoomba another senior commander – General Lavarack of the First Army – and his staff still languished. The First Army had been established in April 1942. Its responsibilities, like those of the Second Army, had steadily diminished.29

However, these changes in organisation were not the outcome of sudden decisions. A big offensive was looming and it was natural that Blamey should choose Mackay and Herring who had experience of New Guinea conditions rather than Morshead and Lavarack who had no such experience. Herring wrote later that, early in 1943, during his leave in Australia, Blamey had made it clear that “the best way of handling things would be for me to carry on with operations to a certain stage and then when my staff had borne their share of the heat and burden of the day Morshead and his staff would relieve me and my staff and take over the next phase of ops and I would go back to Atherton and get on with the reconditioning and training job there. ... The division of responsibility and time of changeover was only roughly worked out, but it was contemplated quite

early that I Corps would carry on till Salamaua, Lae and Finschhafen were taken and II Corps would then carry on to Madang.” This division was well understood by those concerned (Blamey, Herring and Morshead) by the time that Herring flew into Atherton on his way back to Port Moresby in May, and it was on this basis that Herring had invited Morshead to look around New Guinea in June.

When Herring left Port Moresby for Dobodura on 28th August he received his final instructions from Blamey’s headquarters. As well as capturing Lae and Nadzab and establishing airfields, he would “without diverting means from the above role, threaten Salamaua and if opportunity occurred, occupy it and establish aerodrome facilities therein”; deny the enemy use of the Markham Valley in the Sangan area and the plain north of the Markham and east of the Leron, and prevent enemy penetration into the Wau–Bulolo valley by routes from the Buang or the Wampit Rivers. Herring’s own operation order of 9th August had been followed by an amplifying instruction on 25th August.

It was during August that certain differences in doctrine and temperaments between the Australian and American planning staffs became evident. General Chamberlin in particular was very critical of Australian planning and it was largely due to his activities that a serious controversy between MacArthur and Blamey manifested itself in an exchange of letters four days before the invasion of Lae. In letters and notes to MacArthur, Sutherland, Kenney and Barbey, Chamberlin had criticised the Australian planning staff as “undoubtedly new to the game”.

Anxious about the lack of detail apparently supplied by the Australian planners Chamberlin had conferred with Berryman on 4th August. Reporting this conference to Sutherland, Chamberlin wrote that “G3 was given the impression that the Chief of Staff, Allied Land Forces, knew nothing of the progress of the detailed planning of this operation”. Berryman who got on well with Chamberlin noted the result of the conference.

He [Chamberlin] wanted to know our detailed plans for “Postern” and arrangements for coordination. ... I explained our system was to allow commands concerned to work out plans together with Air and Navy on the spot in accordance with the general outline plan. ... The difference is we work on a decentralised basis whilst GHQ have a highly centralised one.

In this last remark Berryman had summed up the difference in a nutshell. Chamberlin’s desire to know every detail led to pungent criticism of the two long Australian orders of 9th and 25th August. Summarising his criticisms in a memorandum for his superiors on 28th August Chamberlin wrote: “The missions omitted are more numerous than those covered. In addition, there are numerous defects ... varying in importance.” Referring to the basic Australian order of 9th August he wrote:–

Judged from our standard of the preparation of combat orders it is elementary and incomplete. ... It is extremely lacking in vision of the function this force is to perform. It decentralises control along with execution. Generally speaking, only the initiation of the operation is covered. The most serious defect is the total lack of appreciation of the logistic problem. ...

This outburst was all the more remarkable in that it was directed at men with at least as much academic staff training as their American opposite numbers and vastly more battle planning experience than the officers at GHQ, and was written at a time when the two Australian divisional commanders were working out detailed logistical plans in cooperation with their American colleagues.

As the result of Chamberlin’s worries MacArthur wrote to Blamey on 30th August about “three items of major importance which are not clear to me and which should, I believe, be clarified”. The first point was the silence of New Guinea Force’s orders of 9th and 25th August regarding the consolidation of the Huon Peninsula and the seizure of Finschhafen as ordered in a General Headquarters’ instruction of 13th June. Secondly he asked for information about the means to be employed and the specific agency to be charged with the “arrangement of overwater transportation for elements of the Allied Air Forces and Lae – USASOS Advance Base Command and, by inference, Australian lines of communication elements which are to follow into Lae to activate airfields and port areas”. MacArthur’s third point was that only the Commander-in-Chief himself was in a position to coordinate the activities of New Guinea Force, Allied Naval Forces and Allied Air Forces, and that therefore it was not right for the New Guinea Force order of 25th August to delegate to the Commander of I Australian Corps “the authority to arrange details of air support and naval support for the operation”.

Blamey replied next day. Referring to the first point he wrote: “The resources and facilities available do not permit of a simultaneous action against Lae, Markham Valley and Finschhafen. The Lae and Markham Valley areas have therefore been selected as the primary objective and the order was designed to secure the capture of these areas. ... On the other hand Commander I Corps ... has been warned to be prepared to take advantage of any early opportunity to seize Finschhafen should one arise.”30

Regarding the other two points Blamey pointed out that his orders had in fact provided for the transport of the rear elements mentioned by MacArthur; and (with regard to command) that “it was not intended, nor could it be read, by an Australian commander, to mean that the arrangement of details in any way affected the ‘coordination’ of the work of the three Services on the level of the higher command”.

There was no time for further argument as the invasion was pending. To the American staff it had seemed that the Australians were following a faulty staff procedure and resented inquiries about details: the Australian staff on the other hand was following principles employed with success

in many campaigns and thoroughly understood at every level of the force which would actually carry out the offensive.

This misunderstanding underlined the weakness whereby since April 1942 an American general headquarters on which there was quite inadequate Australian representation reigned from afar over a field army that was, for present purposes, almost entirely Australian, and whose doctrines and methods differed from those of GHQ. It was evidence of the detachment of GHQ that, after 16 months, its senior general staff officers had little knowledge of the doctrines and methods of its principal army in the field.

It is interesting that only a few days before the Australian orders were written, Major-General S. F. Rowell, a former commander of New Guinea Force now Australian liaison officer in the Middle East, was writing a letter to General Morshead in which he set out some lessons of the landings in North Africa and Sicily, and confirmed two principles by which the Australian commanders were now standing. He wrote from Cairo on 25th July:

(a) Planning

It is essential that the people who carry out the operations should do the detailed planning. There will always be the tendency for those above to try and work out the plans, but I’m sure that this is wrong. Alexander gave Montgomery and Patton the broadest outline plan and the two Army Staffs then broke it down for Corps, Divisions, and Brigades to do the details.

(b) Mixture of Allies in Task Forces

The outstanding lesson of the original North African landings was the failure of mixed task forces. Had the French really fought, there would have been a hell of a mess. That lesson was applied to the full in Sicily where the two Armies were completely self-contained right down to personnel for manning landing craft. For example USN looked after 7 US Army and RN after 8th Army. This gives the freest rein for national characteristics. In your case, a lot will depend on the confidence you and your people have in the Allied organisation which is to transport you to battle and look after your shore organisation. But I’m convinced the principle is basically unsound and, as this war develops, I feel sure that we will see an ever-increasing tendency for us and the Americans to work in our own boxes. I’m talking, naturally, of land forces, as the problem is by no means so acute in the case of naval and air forces.

(c) Beach organisation

Closely allied to (b) is the thorny problem of the beach organisation. In the early stages here, this was found to be the greatest weakness, but, by dint of intensive training and frequent rehearsals, the beach organisation was brought up to a high standard. I think its worth has been proved in Sicily. As I see it, the vital period on a beach is the first few hours, the period when the enemy has the advantage. Again it is all a question of the Australians having confidence in the capacity of the Americans to deliver the goods on the beaches and I feel that no number of liaison officers, with no executive capacity or authority, can replace our own administrative organisations which have trained with assault brigades and have lived with them until they have come to be regarded as part of the brigades themselves.

I don’t want to labour this point, or appear anti-American. Such is far from my mind. But it’s much easier and more effective to lay down the law to our own people than to an Ally.

On 31st August, the day on which he had replied to MacArthur’s complaint about Australian planning, Blamey wrote again to MacArthur criticising a proposal in GHQ’s forward planning. Blamey had just received an outline plan from GHQ which provided for an advance to Madang before the seizure of western New Britain. He thereupon sent MacArthur a four-page memorandum in which it was “strongly urged” that “since the capture of western New Britain is already decided upon, every advantage, and no disadvantage, appears to be on the side of capture of this area prior to the capture of Madang”. Blamey’s covering letter concluded: “It seems to me ... that the Land Forces might anticipate much more vigorous assistance from the Naval Forces if we control Vitiaz Strait from both sides.” Inevitably the events of the next few weeks would show whether Blamey’s misgivings about naval support were justified.