Chapter 11: The Salamaua Magnet

AFTER the success of the 3rd Division round Komiatum and Mount Tambu in mid-August the 51st Japanese Division fought back stubbornly and limited the Allied advance. On 23rd, 24th and 25th August the Japanese launched unsuccessful counter-attacks against the Americans at the junction of Roosevelt and Scout Ridges and at the junction of Roosevelt and “B” Ridges. The Americans tried hard to push along Scout Ridge to secure Scout Hill and Lokanu headland, but their advance slowed down.

On 24th August Brigadier Monaghan’s 29th Brigade took over from Brigadier Moten’s 17th which gathered at Nassau Bay before returning to Australia in September. Patrols of the 47th Battalion next day killed their first two Japanese in the Komiatum area.1 By 23rd August most of the 15th Battalion (Lieut-Colonel Amies2) arrived at Tambu Bay, where it was retained as divisional reserve.

Meanwhile Captain Cole’s company of the 42nd Battalion had repulsed attacks on Bamboo Knoll on 22nd August. The Japanese were mown down by the entrenched defenders who saw 20 bodies outside their perimeter. Cole and Private Deal3 crept outside the perimeter to hunt snipers and killed three more Japanese. When the artillery shelled the attackers the Japanese decided they had had enough and withdrew. The company had a welcome reward when a transport aircraft mistaking Bamboo Knoll for another dropping ground, showered the incredulous troops with rice, powdered milk, custard powder, tinned fruit, prunes, jam, margarine, dehydrated potatoes and onions, fresh bread, buns and tobacco.

Under Lieut-Colonel Davidson’s plan for the drive north along Davidson Ridge after the enemy evacuation of Mount Tambu, Captain Pattingale’s4 company became responsible for the battalion’s rear and for flanking patrols. On the morning of the 22nd two platoons from this company were on patrol and only about 20 men were at company headquarters receiving stores and tightening up the defences. Suddenly they were attacked by about 40 Japanese making their way from the direction of Mount Tambu between Davidson and Scout Ridges. Pattingale and two men were killed immediately, and Lieutenant Friend5 with 16 men concentrated in the South-east corner of the defences and attempted to hold off the charging

enemy. With his ammunition running low, Friend sent Private Brown6 and then Private Ricks7 to battalion headquarters to ask for assistance. Both got through but no help was available. Late in the afternoon the Japanese ceased trying to break the resistance of Friend’s small band and disappeared leaving 10 dead inside the defences.

They had also been unable to stomach the fire from the machine-gun platoon of the 2/5th still with Davidson’s battalion on a hill overlooking Friend’s position. These Japanese, believed to be remnants of the gun raiding force, blundered into Captain Jenks’8 company and rapidly retired in face of heavy fire leaving eight dead.

The 42nd now had only Charlie Hill between it and the flat country round Nuk Nuk. On 24th August, as Jenks’ company began to advance towards Charlie Hill, it could see that the hill was separated from Davidson Ridge by a deep gorge through which rushed a creek. After slithering down the precipitous slope to the creek, the men began to climb the hill. Towards dusk they reached a part of the hill where it was possible to move without clinging to the foliage. Here the company camped for the night and Jenks reported that he would probably capture Charlie Hill next day.

On the left flank the 15th Brigade prepared for the pursuit. Brigadier Hammer ordered that his troops should move by night, that supplies should be pushed forward by day and night using all available resources, and that the enemy should be harassed. He hoped to strike before the Japanese could reorganise and consolidate their rear defences.

Although the enemy returned Hammer’s harassing fire during the night 20th–21st August and engaged in a fire fight at the Orodubi-Komiatum track junction, the strong points at the northern track junctions and at the Komiatum-Orodubi track junction were vacated by first light on 21st August. In spite of the 15th Brigade’s pressure the enemy had succeeded in breaking off action after a skilful withdrawal. One pocket in the area of the track junctions contained the bodies of a Japanese captain, two lieutenants and 20 men who had fought to the death.

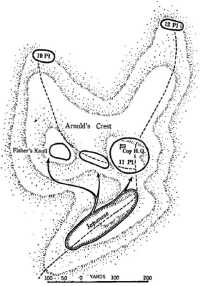

It was now obvious that, to hold Salamaua, the Japanese must occupy Scout Ridge, Charlie Hill and Kunai Spur south of the Francisco and the Rough Hill-Arnold’s Crest area north of the river. Hammer’s previous action north of the river had been limited to patrols designed to ensure that the enemy was not encircling his northern flank. He intended now to gain the high features shown on captured maps as part of the inner defences of Salamaua, before the enemy could establish himself there. However, after learning that Salamaua must not fall before the invasion of Lae, Savige restricted Hammer to securing the Camel Ridge area north of the Francisco and patrolling from it.

Knowing that he held the initiative Hammer was anxious to press on. Before dawn on 21st August his sub-units set out in pursuit. North of the river the leading platoon of the 2/7th climbed the razor-back to Rough Hill, but was pinned down. Major Dunkley then brought up the rest of his company and drove out the Japanese from the position which they had been occupying only about 12 hours.

South of the river a platoon from the 2/7th on the trail of the Japanese retreating from the track junctions was ambushed. All five men of the leading section were wounded and forced to remain within twenty yards of the enemy ambush. Hearing of these casualties the medical officer of the 2/3rd Independent Company, Captain Street, moved quickly north and under heavy fire gave first-aid and helped to carry them out. By evening Captain Cramp’s company of the 2/7th Battalion was astride Buirali Creek while the enemy was holding a line south from the Francisco up Kunai Spur. At 3.30 p.m. on the 21st Lieutenant Bethune’s company of the 58th/59th Battalion advanced up Kunai Spur along the ridge which was 40 yards wide and heavily timbered. Near the north end Bethune was fired on from north and east. With one flank on the Francisco and the other on Charlie Hill the Japanese were in a splendid defensive position and Bethune, with eight casualties, withdrew.

On 22nd August the attempt to prevent the enemy from organising his defences continued. Bitter fighting prevented the 2/7th from breaking the enemy line from the Francisco to Kunai Spur; Dunkley climbed farther up Rough Hill but was stopped by an enemy position near the top; Captain Arnold’s company routed two small Japanese forces on the lower slopes of Arnold’s Crest. Hammer now decided not to worry about his sub-units becoming entangled but to preserve the momentum of the pursuit by urging on companies and platoons wherever they happened to be. He therefore created two special forces: “Picken Force”, comprising all troops north of the river,9 and “Warfe Force”, comprising all troops south of it.10

As it was now apparent that the Japanese had used another escape route from Mount Tambu, the Komiatum Track ceased to be the important life-line it had been throughout the year, and Hammer could move his troops north to the Kunai Spur area and on both sides of the Francisco. With the pursuit so rapid Hammer received a message from Savige on 22nd August stating:–

Situation most satisfactory but on no account undertake any operation which may influence the enemy to evacuate Salamaua.

Having sent this message in accordance with higher policy, Savige considered that it would be a shame to ease the pressure which Hammer was applying so skilfully to the disorganised enemy. Savige knew that Hammer would be unable to keep up the pace, and therefore sent another message on the 23rd that “in view of apparent demoralisation of enemy

on your front pursue your advance to the fullest extent possible without jeopardising the security of your force”.

For three days the troops of the 15th Brigade had kept the Japanese on the move. The men, though very tired, had maintained a remarkable speed of movement in such wretched country by moving at night. Hammer had ordered moonlight advances, but even he was unable to make the moon shine when it should. The men then moved under cover of darkness using torches, although one company commander commented later that “the cursing that was maintained constantly should have lit up the area”.11 While the Japanese were sleeping the Australians were moving. Caught above ground the Japanese did not stay to fight.

The next two days were a repetition of the previous three. South of the river the 2/7th12 was still bogged down east of the track junctions, but across the river the battalion met with some success. On the 23rd Dunkley, aiming for surprise, grouped his Brens forward in pairs. Covering the Bren gunners with Owen gunners he arranged for supporting fire from his mortars and sent his attacking sections round the flanks. The Japanese were overwhelmed by this fire and by such individual acts of bravery as that performed by Corporal Hare13 who charged the enemy’s forward weapon-pits and killed the occupants with his Bren gun. It required only the use of grenades by the flanking sections attacking up precipitous slopes to rout the enemy, who left nine killed. Arnold’s company on the 24th occupied Kidney and Steak after the enemy had vacated their ambush positions.14

Lieutenant Egan’s15 platoon of the 24th Battalion, attached to Captain Newman’s company of the 58th/59th north of the Francisco, moved up Sandy Creek for about 600 yards on 23rd August and ran into a dozen Japanese who disappeared too quickly to be engaged. On the same day Captain Baird’s company of the 2/7th moving up Sandy Creek through Newman’s firm base found the enemy’s signal and kai line running east and was then attacked by a force of about 60 Japanese. After a short fight the enemy withdrew, and later in the day a patrol from Arnold’s company got through to Baird and reported that there were no enemy in between. Egan patrolled east towards Rough Hill along the course of the enemy’s signal wire which had been cut and rolled up by Baird. Suddenly coming upon about 30 Japanese cleaning their rifles and rolling their tents Egan’s men accelerated the enemy’s preparations for striking camp.

Captain Hancock’s patrols from the Independent Company on 23rd August found two more tracks to the north running parallel with the Francisco. The most northerly of all had signal cable laid along it and was thought to be the main Salamaua Track. At 10 a.m. Lieutenant Allen’s platoon, astride this track, drove back a party of 30 Japanese towards Salamaua, killing 7. At 6 o’clock the next morning two Japanese patrols, each about 15 strong, met in front of Lieutenant Lineham’s16 section on the main Salamaua Track and had a chat. Eight were killed before the remainder dispersed into the jungle.

Meanwhile, two companies of the 58th/59th Battalion were concentrating for an attack up Kunai Spur from the west. Kunai Spur rose like a cliff-face from the Buirali and the logical way of approach was from north or south along the razor-back. Yet this way would draw the heaviest fire. On the 23rd there were three separate attacks. First Cramp’s company of the 2/7th Battalion unsuccessfully attacked from the west up precipitous slopes on the north end of the spur. Then one of Bethune’s platoons also attacked unsuccessfully from west to east. The third attack was made by Captain Jago’s company of the 58th/59th from east to west. Although the Japanese defences were not pierced, Lieutenant Mathews’ platoon actually reached the crest and engaged in a fierce grenade fight until the Australians’ grenades were all used. When probing for a weakness to the south Corporal McFarlane17 was killed and Mathews wounded. As it was obvious that the platoon could not capture the strongly entrenched position on Kunai Spur, Mathews withdrew.

“Harass the Jap day and night,” signalled Hammer to his troops, “spoil his sleep, lower his morale, keep him jittery and when you strike hit with all your strength.” The momentum of the pursuit, however, was now petering out because of the wear and tear on the pursuers and stiffening enemy resistance. Determined to keep the enemy unsettled even to the extent of pushing his men to the limit of endurance, Hammer asked Savige to relieve his brigade of all responsibility south of the Francisco. Savige agreed and ordered Monaghan to take over responsibility south of the Francisco and east of the Komiatum Track.

When General Milford relieved General Savige at one minute before midnight on the 25th–26th August he knew that his task was to “continue offensive operations against Salamaua with the object of drawing maximum enemy strength away from Lae”, but not to carry the threat to such an extent as to cause the enemy to withdraw to Lae. As soon as operations against Lae were begun by the 7th and 9th Divisions Milford was to capture Salamaua and destroy its garrison.

Milford was now on active service in the field for the first time since the war began. Four years younger than Savige, he was a regular soldier.

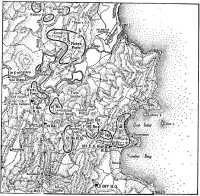

Australian and American dispositions, Salamaua area, 25th–26th August

He had graduated from Duntroon in 1915 and had been a major on the staff when the first war ended. Between the wars he had gained high qualifications as an ordnance and artillery expert and his special training had led to his recall from a command in the Middle East in 1940 to become Master-General of the Ordnance. In the crisis of early 1942 he was appointed to command the 5th Division then deployed in north Queensland and preparing for a possible invasion. The headquarters of the 5th Division had been at Milne Bay since January 1943.

The day after his arrival at Tambu Bay on 21st August Milford, a great walker of the Guinn class, set out to see the 15th and 29th Brigade areas, where he soon came to the same conclusion as his predecessor, namely, that planning purely from a map would be impractical in such difficult country.

The tasks set (he wrote in his report) were tempered by first-hand knowledge of the effort and of the difficulties which might be encountered. At the time of

taking over, a visit from Divisional HQ to HQ 15 Aust Inf Bde required two days each way – a total of four days. Unless traversed in person this would scarcely be believed, but it was unquestionably so in fact; a true appreciation of such difficulties was essential to successful planning.

The country surrounding Salamaua was shaped in the form of a rough bowl with Salamaua as the centre and the enemy holding the lip, but as the enemy’s defence line became shorter, it became more difficult for the attackers to infiltrate and encircle his positions, as they had done earlier in the campaign. The Japanese were bitterly defending these inner defences.

Milford’s resources were dwindling. His units, with the exception of those of the 29th Brigade, had been engaged in severe operations for periods varying from two to six months. The strength of the American battalions was about 33 per cent of their normal establishment and was continuously falling away because of illness. The units of the 15th Brigade were at about half strength. The 29th Brigade was fresh, but untried except for the brief experience of the 42nd Battalion. Many of the native carriers were very tired, having been carrying since the Owen Stanleys campaign, and the sickness rate averaged about 25 per cent. The line of communication from Tambu Bay led over Mount Tambu and down the Komiatum Track, thus entailing a two-day carry to the 29th Brigade. The 15th Brigade was still being supplied by air.

Charlie Hill, midway between Scout Ridge and the Komiatum Track was, in Milford’s opinion, “obviously the keystone of the enemy’s defence structure”. If he could capture it, he would have a downhill run to the Francisco and Salamaua. He believed that a determined thrust by the fresh brigade might bring results. Thereupon he gave the main task to the 29th Brigade, which was ordered to “exert pressure along its entire front in order to ascertain the enemy’s strength and location with a view to finding the best means to break through in this area and exploit down into Salamaua”. Hammer would maintain his present positions, and patrol towards Kela Hill. This, it was hoped, would deceive the enemy as to the ultimate direction of the main drive and would induce him to reinforce his right flank to the detriment of his left and centre. Hammer would also conserve his strength and prepare plans for a drive towards the coast as soon as a break-through appeared imminent. Captain White-law’s company of the 24th Battalion would prepare to seize a position astride the Lae–Salamaua track when ordered. The 15th Battalion was retained as divisional reserve at Tambu Bay. Monaghan was upset

because he was “deprived” of its services but Milford, as well as having to keep a reserve, doubted his ability to keep up supplies to any more battalions west of Scout Ridge.

As the day for the offensive approached it became the more necessary to reduce air supply droppings. With the withdrawal of surplus troops from the Bulolo Valley and the firm establishment of the Tambu Bay line of communication, General Herring hoped that the 5th Division could soon be supplied almost entirely from the sea. Between 24th and 28th August the kai bombers dropped enough supplies to keep the division fighting for another five days. Milford knew that after 28th August he would be supplied by sea, except that the most inaccessible forward troops would still have supplies dropped to them. He decided that a new line of communication, which would avoid the tortuous crawl over Mount Tambu, must be established direct from Tambu Bay to the two brigades. The task of preparing this track was given to Major Colebatch18 and the 11th Field Company and by 3rd September the new track was open.

In Colonel MacKechnie’s area preparations were being made by the II/162nd Battalion to break the enemy’s defences north of Roosevelt Ridge. This battalion, now led by Major Armin E. Berger, had been successful in capturing Roosevelt Ridge. After being relieved on Roosevelt Ridge by a Provisional Battalion of various sub-units, it was now ordered by MacKechnie to cut the Scout Ridge Track at the junction of Scout and “C” Ridges and to establish there a “trail block” on what appeared to be the enemy’s line of communication. Companies from Major Morris’ III/162nd Battalion were established on both sides of the enemy positions at the junction of Roosevelt and Scout Ridges and near the junction of Roosevelt and “B” Ridges; while Colonel Taylor’s I/162nd Battalion was south and west of the junction of Roosevelt and Scout Ridges. In most enemy areas from 26th August MacKechnie’s patrols heard sounds of digging and chopping, sure signs that the Japanese were strengthening their defences.

Under cover of darkness on 26th August Captain Ratliff’s company of the II/162nd led the advance from Dot Inlet to a position half way up “C” Ridge. Supported by artillery and mortar fire the company reached the highest point of the ridge before 9 a.m. and found that the ridge came to a dead end. About 200 yards across a deep re-entrant to the right was Berger Hill, while on the left was high ground which first appeared to be the North-west end of “B” Ridge, but was later found to be a separate hill. Directly in front was a deep gorge which contained a Japanese watering point. Ratliff sent a patrol to investigate Berger Hill. Near the water-hole the patrol killed two thirsty Japanese and spotted defences on Berger Hill. Later in the day another patrol met an enemy party near the water-hole and claimed to have killed eleven before withdrawing under heavy fire.

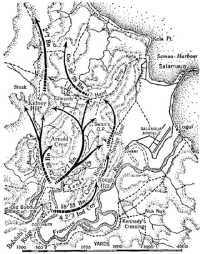

Operations of the 29th Brigade and 162nd US Regiment, 26th August–10th September

For the next three days the battalion continued to patrol from “C” Ridge towards the two hills confronting it. As there was a great deal of surmise about the strength and location of Japanese positions on these two hills Colonel Daly, Milford’s chief staff officer, who was on the spot, persuaded Major Berger to send out a patrol to examine them. The patrol, led by Lieutenant Munkres and accompanied by Daly, penetrated to the southern knoll and discovered a strongly-held enemy position. In the centre a patrol from Morris’ battalion moving up “B” Ridge on 27th August found an enemy position containing about 50 Japanese and after a fight returned convinced that 24 Japanese had been killed.

Taylor’s job on the left was to help Morris clear Scout Ridge but the enemy at the ridge junction prevented any progress. Taylor then sent two companies to the west to encircle these positions, but they were held up by Japanese positions on Bald Hill, a spur running North-west from the ridge junction. One of the companies (Captain George’s) now made a wider encircling movement to the north through jungle-clad and precipitous country. After making contact on the 27th with two companies of the 42nd Battalion who were attempting to find a way round Charlie Hill, George found the main Scout Ridge Track about 1,000 yards northeast of Bald Hill, and ambushed an enemy patrol, killing about eight. These Japanese were fresh and carried new equipment and were apparently marines – ominous signs for the weary Americans. Next day George dug in astride the Scout Ridge Track about 300 yards north of the ambush position thus cutting the enemy’s supply route to Bald Hill.

Early on the 29th patrols found the Japanese position on Bald Hill vacated, and later found an adjacent position unoccupied in an area of about 500 yards just south of Scout Ridge Track near the ridge junctions. Each position could hold 150 men. In the southern one the Japanese had left quantities of rifles, machine-guns and a 70-mm mountain gun. There were 80 dead Japanese in the area, mostly buried by artillery. Thus the strong ridge junction position which had held up progress since 24th July was cleared.

Milford now decided to put in fresh troops to harass the enemy further. First he ordered Captain Hitchcock to send a patrol from the Papuan company, now under direct divisional command, to reconnoitre “D” Ridge and Lokanu Ridge. A patrol set out on 28th August and managed to reach Lokanu Ridge, where they heard talking and shouting from a Japanese position about 100 yards down the south side of the ridge on the western slopes. After this reconnaissance Milford felt able to agree to the plan which Daly had been advocating – to send the 15th Battalion into the American area; Milford felt that a blood transfusion in the form of a fresh Australian battalion might aid the Americans to make more speedy progress. He was also anxious to divert the attention of the Japanese from the fast approaching assault on Lae and to establish himself in a good jumping off position to hit hard when the Lae operations started. If the 15th Battalion could seize the junction of Scout and Lokanu Ridges they would be in a favourable position either to join the rest of the brigade

to the west or press along the ridges towards Salamaua. The 15th Battalion, if on Scout Ridge, could be supplied along a very short route from Dot Inlet.19

North of Davidson Ridge, the 42nd Battalion was stalled before Charlie Hill. Captain Jenks’ company was unable to make any headway on 25th August and suffered several casualties. Realising that it was futile to adopt battering-ram tactics against the well-defended Charlie Hill, Monaghan and Davidson decided to try encirclement. They also had another motive for at 9.6 a.m. on 25th August Savige had signalled his commanders:

Three heavily laden vessels reported leaving Salamaua 0900K/25 in direction of Lae. All units will intensify patrol activity to ascertain if any indication of general withdrawal.

Major Crosswell was therefore ordered to lead two companies of the 42nd to the south and east of Charlie Hill to ascertain if the Japanese were evacuating, and to cut their supply route to Charlie Hill if they were not.

On 26th August the artillery kept pounding Charlie Hill, and patrols of Jenks’ company tried to pinpoint the enemy’s positions. One patrol led by Corporal Hogan20 saw six Japanese robbing the bodies of two Australians, killed the previous day too close to the enemy position to be carried out, and killed four of them.

A more detailed map of the area had recently been received. On it was marked a track running from Scout Ridge north down the next main ridge east of Davidson Ridge, then to the east of Egg Knoll and down towards Nuk Nuk and the Francisco. Another track from the top of Charlie Hill ran east along a saddle connecting Charlie Hill with Egg Knoll and joined the first one near Egg Knoll. Monaghan and Davidson recognised this track junction as a key point. Crosswell was therefore ordered to seize it as part of the plan to isolate and capture Charlie Hill, and also to assist Captain George’s Americans dug in south of the track junction along the track to the east.

Crosswell’s men experienced unpleasant conditions. At 6 a.m. on 26th August they set out from Bamboo Knoll along a very poor track which ran along the steep southern slope of Charlie Hill. After hanging on to the sides, dodging miniature landslides and crawling round jutting rocks for several hours, they descended to a creek junction south of Charlie Hill and then moved east up the main creek. Here a few shells, probably destined for Charlie Hill, landed near them. To avoid the artillery fire, and as darkness was approaching, the companies turned South-east up a steep spur and, almost exhausted, reached the top, where they dug in and had their meal of bully beef and water.

Soon after 8 a.m. on the 27th the two companies set out North-east. At 10.30 a.m. they met a patrol from George’s company in the wild and rugged country between Charlie Hill and Scout Ridge. The telephone wire connecting the companies with Davidson’s headquarters, now on Bamboo Knoll, had been severed by Allied artillery, and Davidson did not know what was happening to his two companies until news of the meeting was sent along the chain of communication from George to MacKechnie, to Milford, to Monaghan, to Davidson.

After parting from the Americans the two companies, about 3 p.m., came to a series of ridges running down to a creek east of Charlie Hill. Lieutenant Ramm’s platoon approached a Japanese track, waited until six Japanese with full packs passed to the South-east and then moved on to the track and cut the signal wire. Platoons from the two companies then crossed the track in succession. During the move shots were fired by the Japanese from above and below. The troops went to ground and wriggled like eels into defensive positions, a not very difficult procedure, according to the historian of the 42nd Battalion, as they were moving through soft mud.21 Digging holes in mud in a prone position was a backbreaking and filthy job, but by dusk the men were established astride the track 400 to 500 yards south of Egg Knoll and the track junction which was their objective. The position was actually between two Japanese posts which had been holding up the Americans. The enemy mortared the Australians and wounded seven.

After a night of tension and expectancy, and a breakfast of bully and water, Crosswell sent a patrol to find the track junction. It found vacated Japanese positions on the southern slopes of Egg Knoll 150 yards from the two companies’ perimeter. Nearby was the track junction, which Crosswell considered unsuitable for occupation because it was dominated by the enemy on higher ground. The telephone line had now been mended, and Davidson was thus able to order Crosswell to occupy the vacant Japanese position, place a standing patrol at the track junction during daylight and withdraw it that night.

That day Milford, Monaghan and Davidson were conferring on Bamboo Knoll. From patrol reports and experience of previous attempts to take Charlie Hill Davidson was convinced that it could not be taken by frontal assault from the south. He therefore proposed that a company should be sent round the western slopes of Charlie Hill to occupy a position on the northern slopes, thus isolating the Japanese, as had been done at Mount Tambu. Milford, however, decided on a frontal attack and promised Davidson 2,000 rounds from the 105-mm guns for the attack. As a result, Davidson warned Jenks that his company would attack Charlie Hill from the west on the 29th, and Crosswell, that one of his platoons would attack up the track from the east towards Charlie Hill in support of Jenks. Zero hour would be 3.20 p.m., and from 11.30 a.m. until that time the artillery would fire nearly 2,000 rounds, the mortars 450 bombs, and the machine-guns 6,000 rounds. The object of this lengthy fire program

was to accustom the enemy to the concentration so that he might be off guard at 3.20 p.m.

From 11.30 a.m. on the 29th the concentration came down on Charlie Hill. In the morning Crosswell sent Lieutenant Winter’s22 platoon to reoccupy the track junction. On the way to its objective the platoon was attacked by about 15 Japanese on its right flank astride the east-west ridge. The platoon killed six, but in doing so lost two killed, and was unable to make further progress. Until this position could be cleared Crosswell held back Lieutenant Steinheuer’s23 platoon which had been selected for the attack on Charlie Hill from the east.

Just on zero hour an American patrol, led by Lieutenant Williams, met Crosswell’s men, and informed them that the Japanese had evacuated the knoll to the south, that resistance confronting the Americans about 800 yards South-east had disappeared, and that he had advanced unimpeded through several Japanese perimeters to meet the Australians. The Americans had pushed north to join with the Australians as the result of a telephone call from Monaghan to Daly asking that an American fighting patrol occupy Scout Camp and test out the knoll south of Crosswell’s position.

On the western side of Charlie Hill as zero hour approached and while the artillery concentration was at full blast, the padre held a moving but unheard service for the assaulting company. Jenks then said quietly: “It’s time to go up lads.” Lieutenant Garland’s24 platoon led the attack, but was fired on after moving only 100 yards. Jenks sent his other two platoons to the right and left flanks but after going only a few yards each platoon found itself faced by precipitous slopes. The approach to Charlie Hill from the west was up a very steep thickly clad razor-back. Without seeing any enemy Garland had five men hit. Two hours after the attack began Jenks signalled Davidson that he could make no progress because of the gorges on either side; the hill was as “steep as side of house” and “every move brings fire which cannot be seen”. Realising that it was useless to batter at Charlie Hill from this side, Davidson recalled Jenks to his original position.

With the brigadier ordering that Crosswell’s two companies must be “pushed hard and fast” with the “utmost aggression”, Davidson at dusk on the 29th issued orders that they move next morning to positions immediately north and North-east of Charlie Hill. Davidson himself set out next morning and arrived at Crosswell’s headquarters soon after 10 a.m.

The decision that Monaghan’s brigade would take over responsibility south of the Francisco and east of the Komiatum Track involved the 47th Battalion. Having relieved the 2/5th Battalion on 24th August the 47th next day took over the positions occupied by Warfe Force. Before the relief, however, sub-units of Warfe Force made further determined efforts

to shift the stubborn enemy from Kunai Spur and the northern track junctions.

For the attack on Kunai Spur Warfe placed two companies from the 58th/59th under Hancock who had to decide whether to mix the two forces or to keep them independent. He decided to mix them under his own commanders. On 25th August he sent out two forces led by Lieutenants Allen and R. S. Garland of the 2/3rd Independent Company to attack Kunai Spur from the east.

Allen made repeated attempts for two hours and a half to reach the crest of Kunai Spur but heavy fire from the flanks forced his withdrawal to a position forty yards below the crest of the ridge where he dug in after inflicting seven casualties. Garland, attacking farther north, encountered two Japanese forces, each about 50 strong, one moving north and the other south; the Australians killed about 20 but were unable to reach the crest of the ridge because of heavy fire from both flanks. Garland tried again farther north but found stronger defended positions, and dug in 30 yards from the crest of the ridge on the line of his original approach. In these actions two were killed, including Sergeant Sides25 killed while leading an assault up the steep slope. The two forces withdrew and Hancock sent out a reserve force under Lieutenant Lineham to attack from the South-west; but this attack met the same fate as the others: heavy enemy fire, precipitous slopes, untenable ground and inability to make any progress.

On the same day Cramp’s company of the 2/7th Battalion made its last attack on the enemy position near the Komiatum-Salamaua track junction. One platoon succeeded in outflanking the enemy and shot three Japanese but when the enemy strongly counter-attacked the platoon was unable to hold its ground. Finally the whole company was forced to withdraw to its original line. During the withdrawal the enemy launched several counter-attacks from the high ground in an attempt to cut off the company’s retreat. Two Bren gunners, Privates Finn and Bayliss,26 decided to hold off the enemy attacks. While Finn took up a suitable position Bayliss ran to an ammunition dump and filled his shirt with grenades. For over an hour the two courageous Bren gunners held off the enemy attacks and enabled the company to withdraw intact. By the time the company was safe Finn had 12 rounds left and Bayliss 15, and all the grenades had been used. With about 50 Japanese casualties to their credit the gunners withdrew. After the failure of these two attacks the sub-units of Warfe Force began to move north and the 47th Battalion began to occupy their positions in the area of Kunai Spur and the track junctions. On 26th August Warfe and Picken Forces ceased to exist.

That day the two forward companies of the 47th began patrolling and probing the enemy’s defences, and both had their first successful

encounters with enemy pill-boxes. A patrol led by Lieutenant Barnett27 climbed to within 40 yards of the main enemy position on Kunai Spur before being seen by the enemy in a forward pill-box. Barnett’s Bren gun team now came into action, but because ferns and tall grass prevented good observation, the Number 2 gunner, Private Domin,28 stood up and allowed the Number 1 gunner, Private Tobin,29 to use his shoulder as a rest. From this human bipod four magazines were fired into the opening of the pill-box; several Japanese ran from it and five casualties were inflicted. Disregarding the bullets which whistled about them, Domin and Tobin coolly kept their unusual position until Barnett withdrew the patrol unscathed.

On the morning of 28th August Barnett was reconnoitring the right flank of the enemy-held spur where he found a large pill-box. He informed his company commander, Captain McWatters,30 who sent forward a field telephone with which Barnett was able to direct accurate fire on to the pill-box. At 5.10 p.m. two platoons led by Barnett attacked the strong Japanese pill-box area from both flanks. One platoon on the right flank advanced north along the eastern side of the spur, and, climbing the crest, got in among the pill-boxes out of which swarmed yelling Japanese. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued. Seizing a machine-gun from a Japanese gunner, Barnett hurled it over a cliff. As his last grenade was faulty because the pin was too widely splayed he rushed a trench and clubbed a Japanese to death. Unable to reload his own weapon because of the fierce fighting Barnett grabbed a rifle held by a Japanese. In the tug-of-war he was wounded when the Japanese pulled the trigger, but this Japanese was clubbed to death also. Under such “cave-man” leadership the platoon killed 31 Japanese for the loss of 4 men wounded before being forced to withdraw. The platoon on the left flank was unable to make any headway up the precipitous slope because of intense fire, and after suffering four casualties it withdrew.

After the failure of this frontal assault, Colonel Montgomery ordered a company to occupy the track junction North-east of Kunai Spur and immediately south of the Francisco River by first light on 30th August. By dusk, however, it was stalled about 800 yards south of the track junction although one patrol did actually reach the junction at 4.30 p.m. and fired on the enemy there. Montgomery ordered Major Leach31 to take command of the company and press on with the task next morning.

In Hammer’s areas as in Monaghan’s the enemy were now fighting back from well-sited and heavily-defended positions. North of the Francisco the 2/7th Battalion was attempting to keep the enemy on the run. Major Dunkley’s company, after harassing Rough Hill during the previous

night, attacked the Japanese position on 25th August, but found it too extensive and well-sited. Pelted with grenades as it lay in unfavourable ground, and unable to reach the pill-boxes, it withdrew. From Captain Arnold’s company Lieutenant Herrod’s32 platoon occupied Steak; while Lieutenant Edwards’33 platoon, accompanied by three of Herrod’s men who were to return next morning, occupied the feature named after its platoon commander. Captured Japanese documents and maps of the area north of the Francisco showed their anxiety about this area. In orders to the Japanese No. 2 Sentry Group at Arnold’s Crest (Calabash Mountain) the Japanese commander stated:

The enemy is in Bobdubi, Komiatum and Grass Hill [Charlie Hill] and apparently 20 enemy are in the upper reaches of the Buiris Creek. Our troops will soon arrive at the position. There is now a sentry group of ours in Ogura Mountain [Camel Ridge–Rough Hill]. About 300 metres to rear of this group is a larger sentry group. About 600 metres behind that is No. 1 Sentry Group.

Later orders to No. 2 Sentry Group stated:

Main enemy body appears to be attacking from track leading to Buiris Creek whilst a portion are attacking from the direction of Mount Ogura. Defend the present position to the death while the main body counter-attacks on left flank and rear.

On 26th August Hammer planned the redisposition of his brigade. The 2/7th Battalion would occupy an outer perimeter extending from Savige Spur-Hand-Edwards’ Spur-Kidney Hill-Steak, with a reserve on Swan’s OP; the 58th/59th would occupy an inner perimeter extending from Camel Ridge–Rough Hill–Sandy Creek area–Arnold’s Crest; and the Independent Company would be brigade reserve and protect Bobdubi Ridge in the Bench Cut–Coconuts area. For the first time in two months Hammer felt able to afford the luxury of a substantial reserve. While the units were on the move the kai bombers arrived over the area and distributed ammunition and rations over the countryside, mainly among the Japanese. Soon afterwards a company of the 2/7th was mortared with Australian 3-inch mortar bombs collected by the Japanese after the dropping, but the Japanese did not know of the disarming measures taken when dropping mortar bombs and none exploded.

Colonel Picken began to have misgivings next day that his troops were not actually in the positions reported, and eventually Dunkley found that his company was not on Savige Spur as reported previously and had not passed Rough Hill; the rugged nature of the country and the unreliability of the map made it extremely difficult to pinpoint positions accurately. It was evident from the appearance of Japanese in clean clothes that the enemy, who had been off balance since 20th August, were now being reinforced in an attempt to push back the weary Australians.

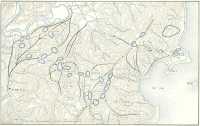

15th Brigade operations, 26th August–10th September

Indeed, the Japanese were suddenly becoming very active north of the Francisco, and at 4.40 p.m. on the 27th Baird’s company in Sandy Creek was heavily attacked by a large and determined enemy force attempting to move round his flanks. The Australians gave the enemy a hot reception. Taking up a position between the two forces Sergeant Sinclair34 directed mortar fire on to the Japanese and thus helped to take the sting from their attack. In order to keep the troops supplied with ammunition Private Blythe35 moved back and forth carrying boxes of ammunition to the hard-pressed troops. During one of his trips forward Blythe noticed an enemy force gathering on a spur to the left of the forward platoon Completing his journey with the ammunition he returned with the grenade discharger and accurately grenaded the enemy, causing them to disperse. Enemy pressure continued, however, and after a telephone conversation in which Baird, Warfe, Picken and Hammer were all on the line together, Baird extricated his company.

By dusk on 26th August the 58th/59th Battalion had occupied their positions as ordered by Hammer. Three companies were in the Camel Ridge area and Lieutenant Bethune’s was on Arnold’s Crest. At 9 a.m. on the 27th the carrier line to Bethune’s company was ambushed south of Arnold’s Crest and Bethune was out of communication. Relieving patrols from the 58th/59th were ambushed by strong Japanese forces. Bethune’s first intimation that anything was wrong came at 6.15 a.m. on 27th August, fifteen hours after he had taken over, when he heard firing from the direction taken by a patrol sent to find why the telephone line between his company and Arnold’s had been severed. An hour later his men saw Japanese moving along the track 100 yards south of company headquarters. At the same time line communication with battalion headquarters was cut. Arnold’s Crest was a triangular-shaped feature. In

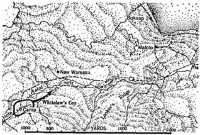

Arnold’s Crest, 27th August

the centre company headquarters was established with one platoon. The other two platoons were situated on the northern right and left hand spurs, about 400 yards from headquarters and from each other.

To counter enemy movement seen to his south Bethune sent out six men to investigate, but after 75 yards they met heavy opposition and were driven back with casualties. The Japanese, under cover of night, had reoccupied some of their former positions. Noticing movement to the west Bethune feared encirclement and sent five men to occupy a knoll west of his headquarters. This patrol met opposition on the knoll but, due to the determination of the company cook – Corporal Fisher36 – it gained its objective. In the afternoon small enemy parties tried to stalk company headquarters. They were all repulsed, but by 1.30 p.m. Bethune was becoming anxious about his ammunition supply and sent three men west to battalion headquarters to report. As the Japanese were apparently in large numbers on most sides of him Bethune at dusk withdrew his two outlying platoons and occupied two positions – the present headquarters position and Fisher’s Knoll with a connecting section along the linking saddle. Throughout the night the noise of enemy movement, voices, and harassing fire convinced Bethune that the Japanese were being reinforced.

At 5.30 a.m. on the 28th the Japanese attacked strongly from east, south and north. Using fixed bayonets, throwing grenades, and yelling they came on in greatest strength from the east. Here the Victorians, fighting stubbornly, were forced back. Determined enemy attacks continued, and when it became obvious that his ammunition would not last another quarter of an hour Bethune reluctantly decided to withdraw. By 7 a.m. when the company reached a creek junction west of Arnold’s Crest, Bethune tapped the

signal wire and reported to Warfe. In this fighting Bethune had 8 casualties and estimated that his men killed at least 40 Japanese. Had sufficient supplies been available Bethune was sure he could have held the feature.

It would probably be fair to say that the enthusiasm of the forceful Hammer had led him to outreach himself On 29th August he decided on a less ambitious plan – the holding of a line Rough Hill-Savige Spur-Arnold’s Crest-high ground west of Buiris Creek. The 2/7th Battalion would occupy the area from Sandy Creek through Arnold’s Crest to the high ground west of the Buiris; and the 58th/59th the Camel Ridge-Rough Hill-Savige Spur feature. Before carrying out this plan Arnold’s two forward platoons were extricated from their scattered forward positions behind the enemy on Edwards’ Spur and from Hand. Both platoons had remained in their areas until lack of food and ammunition forced them to return through enemy territory.

The Japanese were aggressive in their patrolling but they were unable to surpass the patrolling skill of the active Australians who, on the narrowing front, actually began running into one another. Reconnoitring ahead of a patrol Corporal Webster37 saw 57 Japanese moving down the track with picks and shovels. Soon afterwards 20 returned and half an hour later they came back again carrying picks and shovels. Webster had just returned to his men when unexpected and heavy fire forced the patrol to take cover. Later it was found that a patrol led by Corporal Gibbons38 was also watching the track. Gibbons and his men had taken up a favourable position behind a log on the side of the track. Six Japanese came up the hill puffing and sweating, and carrying full packs. Thankfully they sat down on the log. Politely allowing the panting Japanese to slip off their packs Gibbons’ incredulous men arose from behind the log, killed five Japanese, sent the other down the track at high speed, and put Webster’s patrol to ground.

North of the main theatre of operations Captain Whitelaw’s company of the 24th Battalion was meeting stiffer resistance along the Hote-Malolo track. Moving south, to link up with the 2/7th in the Buiris Creek area, Lieutenant Looker’s platoon on 26th August ran into an enemy position defended by about 50 Japanese astride the track and lost three men including one killed. The next day Looker unsuccessfully but persistently attacked the enemy, who had been reinforced during the night. It now appeared that the Japanese were holding a western defence line from New Wamasu south to Looker’s Ridge, but this did not prevent Corporal Leslie’s39 patrol from killing eight Japanese washing in a small creek about three-quarters of a mile from Malolo.

By 29th August eight Allied infantry battalions, one Independent Company and one infantry company were struggling bitterly to gain the last

high semi-circle of ground before Salamaua. On all the key features – Scout Ridge, Charlie Hill, Kunai Spur, Rough Hill, Arnold’s Crest – the enemy was fighting a desperate last ditch battle with skill and determination and some success. Both sides had some fresh troops but the majority were battle-worn and tired. In an endeavour to crack the Japanese defences General Milford brought his ninth infantry battalion into the line. On 30th August he ordered Colonel Amies to move the 15th Battalion round the right flank of the Americans and penetrate the enemy’s main line of defence at all costs and with the least possible delay. On reaching the top of Scout Ridge one company would advance North-east to seize Scout Hill, while the remainder of the battalion would be ready to advance to Nuk Nuk. If strong resistance was met Amies would encircle the position and not commit his battalion to a frontal attack.

At first light on 31st August the leading platoon (Lieutenant Matthew40) of Captain Provan’s41 company struggled up the precipitous slopes and at 11.45 a.m. reached the Bamboos, a kunai patch with a clump of bamboos on a razor-back at the junction of “D” and Lokanu Ridges. There the advance was detected by the enemy and Matthew was halted by mortar and machine-gun fire. To Milford, hoping that surprise would enable the battalion to reach the crest of Scout Ridge, this check seemed the missing of a golden opportunity. He considered that “the enemy was given time to occupy strong positions on the crest of the ridge overlooking the Bamboos”.42

At midday Daly obtained permission from Milford to go forward and try to push things along. Milford and Daly had hoped that the battalion would “go hell for leather” up the ridge with at least one company, and were certain that a swift punch would have got astride Scout Ridge before the Japanese could reinforce that particular position. The enemy obviously could not be strong all along the ridge.

This was a normal enough reaction from divisional headquarters, but the fact was that Matthew, who had learnt his soldiering with the 2/5th Battalion, knew the value of surprise and the effect of determined action when surprise is lost. He had no artillery or mortar support because the American signallers had been outstripped in the rapid advance and did not reach the forward area until late in the afternoon. He had been warned to avoid frontal attack and therefore tried to encircle the enemy. The precipitous slopes of “D” and Lokanu Ridges at their junction with Scout Ridge, however, rendered movement impossible on more than a one or two-man front. Despite heavy opposition Matthew did manage to advance another 75 yards, but at 12.50 p.m. was met with a shower of grenades from the enemy on a crest above. He therefore decided to await the arrival of some added fire support for an attack straight up the ridge.

Provan arrived with the rest of the company soon after 1 p.m. and organised a company attack, which, however, could only be on a one platoon front. There was still no artillery or mortar support as Matthew’s platoon led the attack up the slope. The Japanese, well entrenched in heavily timbered country, reacted violently and inflicted 11 casualties, including Matthew who was mortally wounded. By 4 p.m., however, Provan secured a precarious foothold and dug in for the night about 150 yards from the main Japanese positions on Scout Ridge. Captain Proctor’s43 company dug in 300 yards down the slope to support and supply Provan.

During the night Allied artillery shelled the Japanese above the Bamboos. At first light a detachment of mortars and a section of machine-guns were sent from the beach and manhandled into position at the Bamboos. In the morning the enemy above Provan’s position made two determined attacks on the company which were repulsed by the defenders aided by artillery fire. Provan suffered heavy casualties: 21, including three officers wounded – himself, his second-in-command, Captain Struss,44 and one of his two remaining platoon commanders, Lieutenant Rattray.45 A stretcher bearer, Private Sallaway,46 although wounded himself, tended the wounded men and arranged their evacuation to the beach.

The ranks of Provan’s battered but still defiant company, now led by the remaining platoon commander, Lieutenant Thirgood,47 were so depleted that Proctor moved his company late on 1st September and combined with Thirgood’s men who were still clinging to the ground gained the previous day by Matthew’s platoon. The rest of the battalion, blocking up behind, was kept busy bringing up supplies. At 6.55 p.m. the enemy made his third attack for the day but was again repulsed. Ten Japanese were seen to have been killed during the day and several others were seen falling down the steep sides of “D” Ridge. The defenders also captured three enemy LMGs and ammunition, which they used that night.

At first light on 2nd September patrols sought routes to Spout Ridge across the precipitous ravines to pinpoint the flanks and the depth of the enemy position. Lieutenant Best’s48 platoon climbed to the east and then approached the enemy from the North-east. After artillery fire they reached the Japanese defences and found them smashed by the fire, but discovered that the real crest of Scout Ridge was one ledge above this position. They were forced to withdraw, but not before 12 Japanese were killed. Artillery and mortars immediately registered the new Japanese positions, while the area of the false crest became no-man’s land. On 3rd September the mortar platoon sergeant, Whitlam,49 crawled to within 100 yards of the

crest to register his mortars on to the enemy position. In the afternoon he led a small patrol up a re-entrant to the west; it reached the real crest of Scout Ridge, and reported that the enemy positions were a smoking ruin and that the crest of the ridge was a small plateau about 100 yards deep.

Expecting no opposition a platoon led by Lieutenant G. N. Matthew (brother of D. H. Matthew) followed the same route with another platoon in support. Matthew negotiated the almost perpendicular climb and had reached the lip of the plateau when his 24 men were heavily attacked by Japanese with mortars, grenades and machine-guns. The enemy was strongly established on the plateau, some of the barricades being made of trees felled by the artillery, and could only be reached on a one-section front. As it was obvious that further artillery preparation was necessary Matthew returned to the Bamboos.

Meanwhile Amies was paying attention to Lokanu Ridge, which, if occupied by the enemy, would command and threaten the battalion’s right flank and supply route to the forward companies. As the entire Lokanu Ridge, as well as Dot Inlet and the battalion’s beach-head were dominated by the eastern end of Lokanu Ridge Amies decided to seize it. He gave the task to Lieutenant Cavenagh’s50 company which had been patrolling to Lokanu Ridge since its arrival in Dot Inlet. On 3rd September Cavenagh sent Lieutenant Byrne51 to occupy the eastern end of the ridge.

Byrne set out with three men, Privates Rose and Dehne52 (of the 2/6th Battalion who were experienced scouts) and Private Kane,53 up a spur to the north of Lokanu village. Scouting ahead of the other two, Rose and Dehne noticed, about 20 yards ahead along the track, a broken limb hanging from a tree and partly obscuring the track. Both leapt for cover as Japanese machine-guns opened up. Moving through the jungle the two men crept up to a pill-box into which Rose threw three grenades and Dehne fired his Owen. Inside they found three dead Japanese marines. Under cover of artillery fire Byrne’s men crept up towards the knoll near the east end of the ridge hoping that the Japanese would vacate their positions during shelling. About 100 yards from the knoll the artillery ceased and Byrne dashed to grab the knoll before any Japanese could return. As anticipated he found freshly dug trenches, weapon-pits and foxholes, which had been recently occupied. As soon as the four men had occupied the position as adequately as they could Byrne sent Kane back for reinforcements.

The fresh Japanese marines encountered by the Americans and Australians on Scout Ridge were members of the 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force. Commander Takeuchi, in charge of these marines, had landed at Salamaua on 1st July. On 17th August two large MLCs landed some of his marines at Salamaua and

four others landed the remainder at Lae. On 28th August Takeuchi, now apparently commander of the Salamaua garrison, recorded that a naval force was defending the Lokanu positions. The army force there had been reinforced with fresh troops and was counter-attacking: Takeuchi ordered the marines to organise raiding units and attempt to wipe out the enemy in one week.

On 4th September reports began to come in from observation posts about the Allied landing fleet east of Lae. This landing, however, did not lead to any immediate lessening of the enemy’s resolve to defend the ridges and knolls he was occupying.

In the early afternoon of the 5th Byrne, whose booby-traps had already claimed several victims, repulsed two attacks from the east and northwest. By this time patrols had found three Japanese positions on Lokanu Ridge – the Pimple, the Knoll and a pocket east of Byrne’s OP. Amies ordered Lieutenant Farley’s54 company to wipe out the Japanese opposition at the Pimple which threatened the rear of Proctor’s company. About 2 p.m. a platoon attacked south down Lokanu Ridge from Proctor’s position, but heavy machine-gun fire commanding the razor-back approach gave little hope of success and the platoon withdrew.

The enemy really tried to remove Byrne on 6th September. Several small attacks from first light were repulsed with the aid of the mortars. The platoon was in an arrow-shaped perimeter with the forward gun-pit at the tip of the arrow pointing down the narrow precipitous ridge towards the sea. Soon after 4 p.m. a booby-trap exploded. The Queenslanders, alert, waited. Suddenly screaming Japanese charged up the ridge with fixed bayonets. From the forward gun-pit, Private Troughton55 and Private Gill56 greeted the charging enemy with rapid Bren gun fire. Many of the Japanese fell but the charge continued and some reached within five to ten yards of the pit. One Japanese threw a grenade which landed on a mound in front of Troughton, showering him with earth and dazing him for a few seconds. The Japanese could not take advantage of this lull in the fire from the deadly Bren because of fire from other members of the platoon and because Gill hurled grenades which kept them at bay until Troughton recovered and fired the Bren again. The fight lasted about half an hour before the Japanese withdrew leaving 20 to 30 dead near the Bren gun-pit. Four of the dead Japanese were dragged into the Australian perimeter before dark and proved to be marines. After this seventh attack had been repulsed by the platoon, the remainder of Cavenagh’s company joined Byrne in the Byrne’s OP area.

Patrolling continued on the 7th and 8th when Amies probed enemy positions on Scout Ridge and Lokanu Ridge. Artillery and mortars softened up the Japanese positions. By 9th September Amies felt able to carry out a two-pronged attack on the crest – Proctor’s company from the Bamboos and Captain Leu’s company by an outflanking movement from the enemy’s right rear along a newly-discovered track. Both attacking forces

were limited by confined approaches to a one platoon front; Best’s from the Bamboos and Thirgood’s round the flank. Thirgood set out at 10.10 a.m. and reached the crest of Scout Ridge without opposition at 2.40 p.m. One section remained at the track junction in the old Japanese perimeter at the false crest while the remaining two sections moved North-east up the crest of Scout Ridge. At 3.35 p.m. Thirgood reached the South-west edge of the Japanese position facing the Bamboos. After an artillery bombardment arranged by Lieutenant Johnson,57 the OPO for the 25-pounders, and mortar concentrations, Thirgood and Best attacked the position simultaneously. The enemy fired a green flare and withdrew. After minor skirmishes Thirgood and Best met in the enemy perimeter which contained many dead and much equipment. The Australians patrolled North-east up the track without encountering any opposition.

On Lokanu Ridge Lieutenant Turner’s58 platoon, with artillery and mortar support, attacked east towards the last Japanese strongpoint at the eastern tip of the ridge overlooking the sea. The Japanese hastily evacuated the position, fleeing into the jungle below and leaving their dead and equipment. Patrols from the Bamboos completed the happy picture when they found the Pimple and the Knoll on Lokanu Ridge unoccupied. Perhaps the Japanese had withdrawn from both positions when the green flare was fired. After a successful 10-day initiation in the battle area Amies was able to signal Milford late on 9th September that the 15th “now holds line of (Lokanu) Ridge complete from sea at Lokanu to crest of Scout Ridge”.

To the left of the 15th Battalion the 162nd Regiment’s II and III Battalions now concentrated on the enemy pocket between them on Scout Ridge, while Captain George’s company from the I Battalion occupied Grassy Spur on the main Scout Ridge Track, thus completing the encirclement. George’s company on Grassy Spur killed 20 Japanese on 29th and 30th August, most of them escaping North-east from the evacuated perimeters at the ridge junction. This aroused the enemy, who established strong positions east and west of George’s company and severed his connection with battalion headquarters. Patrols were unable to break through to the beleaguered company on the 31st, and it was not until the afternoon of 1st September that George’s runner, who had wormed his way out, was able to tell Colonel Taylor that during the previous day and night the Americans had repulsed nine determined bayonet attacks on Grassy Spur. The 84-man garrison estimated that it had killed 80 of 250 attacking Japanese for the loss of 8 casualties. The defenders’ ammunition was almost exhausted as George awaited the rifle shot which was to be the signal to withdraw.59 He then thinned out his troops, and managed to

evacuate all, including his wounded, through the encircling Japanese to the I/162nd Battalion.

Meanwhile the II and III Battalions were trying to disperse the Japanese pocket. After a mortar bombardment two companies (Colvert’s and Ratliff’s) attacked the pill-boxes from two sides and by dusk their forward patrols were within 100 yards of each other, but were unable to make further progress. Patrolling and heavy bombardments by American mortars continued for the next few days.

By 4th September Commander Takeuchi was more defensively minded about his southern flank than a few days previously when he had ordered his marines to defeat the Allies “in one week”. Now he ordered his No. 1 company commander to “use one of his platoons to fill up the gaps between the army and the navy forces at Lokanu”.

By 8th September the Japanese had begun to withdraw. The pill-boxes and also the ridge between the II and III Battalions were empty; and on 10th September it was found that the Japanese had withdrawn also from Berger Hill.

In the central area the enemy was grimly hanging on to Charlie Hill and Kunai Spur. East of Charlie Hill Davidson met Crosswell’s two companies on the morning of 30th August, and instructed Crosswell to establish his force astride the track running along the saddle between Charlie Hill and Egg Knoll. When approaching the saddle Crosswell met strong enemy positions. Lieutenant Winter’s platoon supported by Lieutenant Ramm’s attacked but could not dislodge the Japanese before dark although they cleared several foxholes. Crosswell therefore withdrew to a perimeter position. During the fighting Captain Cole arrived to resume command of his company as Davidson required Crosswell as second-in-command. After dark the Japanese mortared the Australian position, wounding six men including Cole who remained on duty. The skirmishing continued on the 31st with the two companies unable to make any headway against strong well-camouflaged positions commanding both flanks.

At this time there was a race between Hammer and Monaghan to see who would reach Salamaua first. In idle “chipping” Hammer stated that Monaghan had come in at the death knock, and Monaghan told Hammer that he could relax and leave the battle to the 29th Brigade who would “clean it up for you”. There was great rivalry between them about their brigades’ performances and this tended to make them drive their men hard.

After the failure of Jenks’ attack on 29th August Davidson decided to cut the enemy’s supply route and try to encircle Charlie Hill by moving round the western flank of the hill instead of the east. This had been his original plan. Thinking of the tactics successfully employed at Mount Tambu he rang Captain Greer and said: “I want you to go around the other side of Charlie Hill and sit on the Nips’ kai line.” Artillery harassing fire was brought down during the day to keep the Japanese in their foxholes, and thus enable the company to move undetected.

On 2nd September at 3.45 p.m. Greer reported that he was north of Charlie Hill commanding a well-used track about 200 to 300 yards from the crest of the hill. He was jubilant about his position, from which he had a good view of Salamaua, but it was a three hours’ job to fetch water. “Well done,” signalled Monaghan to Davidson. “Now let him know you are there. Plenty of water on Charlie Hill.”60 Although he did not know it, Greer had dug in only 30 yards below the enemy perimeter on Charlie Hill. After he had completed his defensive preparations, the Japanese attacked three times but were repulsed each time with heavy casualties.

On 2nd September Captain Ross’ company was ordered to establish contact and cut the remaining Japanese tracks running North-east from Charlie Hill. It had dug in on the saddle by 4.30 p.m., cut the enemy signal wire and set booby-traps. During this move Ross made contact with the I/162nd Battalion, and on 3rd September Davidson ordered him to link with Greer as soon as possible. After dispersing four Japanese examining their booby-traps, the company was preparing to move off about midday when the Japanese bombarded it with mortar bombs, among which were the usual percentage of duds. An attack followed, but after losing 15 killed in 10 minutes the Japanese withdrew.

The company then set off around the eastern slopes of Charlie Hill to link up with Greer who had already repulsed two enemy attacks that day. As soon as Ross’ last section moved off, the Japanese moved in behind, occupied the position just vacated by the Australians and cut the Australians’ communications. Moving slowly along the precipitous slopes of the hill Ross was forced to make an early halt for the night as his water supplies were getting low. A patrol obtained some from the bottom of the gorge at a stream obviously used also by the Japanese. As digging would have made too much noise the company perched for the night among the tree roots.

At 7.30 a.m. on 4th September Ross, still out of communication, continued his move. Searching for the main track, the leading platoon (Lieutenant Birch61) reached one Japanese supply track, and then crossed the main Japanese line of communication with signal wire running along it; 40 yards beyond this Birch met Greer’s outposts. Only 500 yards separated the companies. Lieutenant Winter’s supply train for Ross’ company was fired on from the position at the saddle which the Japanese had reoccupied. The natives dropped their loads and went bush and Greer was instructed to supply Ross with rations from his own meagre store.

On 4th September Monaghan informed Davidson that he intended to visit the company position north of Charlie Hill to enjoy the view extolled by Greer and to watch an artillery bombardment on the 47th Battalion’s area. Next morning Monaghan, accompanied by a British Army observer, Lieut-Colonel G. N. C. Smith, reached Greer’s position just before midday. Soon afterwards misfortune again befell the ration train which this time was moving round the western slopes of Charlie Hill to supply

Greer. From a newly-established position on a ledge commanding the supply route the Japanese fired on Lieutenant Harvey’s62 ration train with the same results as on the preceding day. Sergeant Blow,63 leading the next ration train, decided to bypass the Japanese. Moving 100 yards down the ridge to the west, he travelled parallel with the track above and then turned east on to the track again. Unfortunately he came back too soon, and under enemy fire the carriers again went bush. Davidson then made arrangements for the ration train on 6th September to bypass the ambush more widely. Meanwhile the companies went hungry, and Monaghan and Smith were forced to spend the night in the perimeter.64

Soon after Birch’s platoon met Greer’s outposts, Ross and one of his men were mistaken for Japanese by Greer’s men and wounded. The adjutant, Captain Frainey,65 was then sent to take command. On the 5th Birch patrolled up Charlie Hill and reported that the enemy had a post 50 yards from the top. At 10.30 a.m. Corporal Dwyer66 met a lone Japanese and shot him from the hip. To the delight of planners this Japanese was carrying a sketch of the defences of Charlie Hill. By the early afternoon the company had dug in between the old and new tracks. To the South-east Winter reported that the Japanese had a chain of positions 150 yards long astride the creek running north and south between Charlie Hill and Egg Knoll.

On the morning of 6th September, Davidson ordered Jenks to attack the ambush position and gather into a dump the rations discarded by the boy-line on the previous day. Monaghan also sent out Birch’s platoon to try to clear the track. Under cover of these attacks a carrying party laboriously carried the dumped stores to the two hungry companies, bypassing the ambush position, and Monaghan and Smith returned with the carrying party, much to the relief of the various headquarters.

Although the night was cold and rainy and the platoon was miserably cold, Birch felt some compensation because his platoon had captured three maps during the afternoon’s fighting. These were rushed to Boisi for interpretation; they showed three large Japanese perimeters on Charlie Hill.

In command of the Japanese defences on Charlie Hill was Lieutenant Usui of the II/66th Battalion. After fighting his way out of the Mubo trap up the Bui Kumbul Creek, Usui had fought on Ambush Knoll, whence he was forced to withdraw to Timbered Knoll. His disheartening series of withdrawals continued when Lewin drove him from Timbered Knoll at the end of July and reduced the effective strength of his company to 31. One of the captured messages said that the Japanese were planning to cut the supply and communication lines of the Australians at the

rear of Charlie Hill as soon as reserves arrived, and were also planning to set fire to the kunai. In a second message written on the back of the first, Usui reported the disappearance of his line maintenance section after encountering the enemy on the way, the arrival of only one of his runners, and the killing or wounding of several others by the encircling Australians.

Unfortunately by the time the translation was received by Davidson the kai line had been cut and two of Greer’s platoons had been forced to change their positions because of kunai fires.

At night on 6th September Monaghan warned Davidson to prepare for an attack on Charlie Hill in three days’ time. The maps captured by Dwyer and Birch enabled the attackers to know exactly what they were up against. At 9.30 a.m. on the 9th after a mortar barrage, two of Frainey’s platoons crossed their start-line on the northern slopes of Charlie Hill. Fifteen minutes later the first platoon occupied the first Japanese perimeter without opposition. The second platoon, passing through, occupied the other two Japanese perimeters. Charlie Hill was in Australian hands. The Japanese had moved out the night before leaving fresh uneaten food (including grapefruit), automatic weapons, mines and grenades. They had also dismantled and buried a mountain gun. The occupying platoons counted 30 dead Japanese mostly killed by artillery and mortar fire. The hill, as with most captured Japanese positions, was nauseatingly filthy and the stench overpowering. The habits of some Japanese soldiers in occupation were worse than those of many animals; and this poor sanitary discipline no doubt accounted for the enemy’s high rate of sickness.

With Charlie Hill secured at the track junction between Egg Knoll and Charlie Hill and a link formed with the Americans, “B” Company, now led by Captain Ganter,67 set off in pursuit towards Nuk Nuk at 10.20 a.m. and spent the night in an old Japanese position farther down the hill.

To the left of the 42nd Battalion, the 47th on 30th August was preparing for another attack on the Kunai Spur and pill-box area. Advancing over very rugged country Major Leach’s company reached a position astride the main track west of the junction by 10.35 a.m. Here they were pinned down, and Leach and Sergeant Eisenmenger,68 reconnoitring near the track junction, were killed by sniper fire. Patrolling to find the enemy’s left flank continued but at 5.30 p.m. Captain Pascoe, having lost 9 casualties, reported that because of “intense enemy opposition” he was withdrawing to his firm base South-east of Kunai Spur.

After further skirmishes on the 31st Colonel Montgomery decided that the defences of Kunai Spur were known as well as they could possibly be from the outside, and he ordered Captain Lewis’69 company to capture it. Next morning the artillery fired 600 rounds, mortars fired 120 bombs, and machine-guns 8,000 rounds. The platoons attacked vigorously, driving many of the panicking and screaming enemy from their positions. Others

who remained in their holes were killed with Owens and grenades. By 5.20 p.m. Lewis’ men held positions facing the next Japanese defences on the north end of the spur.

Sound planning and determined execution by an untried company had resulted in a success equal to that expected from more experienced and battle seasoned men. For the loss of two casualties, including the leading platoon commander, Lieutenant Walters,70 who was killed, Lewis’ company counted about 60 dead Japanese on Kunai Spur, about 40 of whom had been killed by the artillery fire which had scored five direct hits on pillboxes.

Montgomery decided to make another attempt to cut the enemy’s line of communication to the pill-box area north of Kunai Spur, now renamed Lewis Knoll. On 2nd September he ordered Captain Yates’ company to occupy a base 500 yards east of the Salamaua Track junction which the battalion had previously been unable to capture. The company was held up by Japanese opposition ahead and on the flanks. A patrol cleared the enemy immediately ahead, killing five and sending the others fleeing into the dense jungle, but it was too late to go any farther that day; at 7.15 next morning the company again moved forward and managed to reach a razor-back running up to a strongly-held enemy position on Twin Smiths. Leaving their defences in an attempt to drive Yates off the spur, the Japanese lost 20 killed. Returning to their entrenchments they then waited for the Australians to advance. When the company did so, heavy fire and the difficulty of countering it from the Australians’ precarious hold on the razor-back precluded the company from even digging in, and Yates withdrew. The Japanese resisted any further moves in this area and on 6th September drove back an attack by Lieutenant Edwards.71

After more reconnaissance by Lewis’ and Captain Muston’s72 companies and small but successful ambushes, Montgomery ordered Lewis to capture the ridge north of Lewis Knoll on 8th September. For two hours the mortars and machine-guns fired on the Japanese positions and at 10.30 a.m. two platoons began to make their way up precipitous slopes to the Japanese position on the crest, through bamboo, undergrowth and timber felled by the mortars. Soon one of the supporting medium machine-guns was hit and put out of action, a light machine-gun was wrecked by grenades and another two developed stoppages at critical times. Japanese snipers on the left and heavy cross-fire from the pill-boxes helped to cause Lewis’ withdrawal after getting within grenade and Owen range of the crest.

On the 8th, however, four pill-boxes on a knoll between Charlie Hill and Lewis Knoll were abandoned by the enemy. Indications of a general Japanese withdrawal from the area facing the 47th Battalion were still more apparent when, on the 9th, three forward companies found unoccupied pill-boxes facing them.

By the end of August any movement by 15th Brigade patrols aroused immediate and determined opposition from fresh and well-equipped troops – a readily understandable reaction in view of the 15th Brigade’s close proximity to the enemy’s most vulnerable areas. Japanese maps captured on 23rd August estimated that the brigade’s strength was 4,000; actually it was only 1,227, not all of them fighting troops.

In his report Hammer summed up the brigade’s feeling of dogged determination to see the job through:

Our troops at this stage were magnificent, many sick refused to be evacuated – they knew the unit strengths were low and they preferred to remain and continue the fight. Gallant determined actions were fought day after day as our troops progressed on their encircling move along the high ground north of Salamaua but the strain of continual day and night moves and the heavy fighting over tortuous terrain began to tell. The needs of reorganising and the establishment of sound supply lines as well as rest forced a halt. ... All troops were exhausted.

Tinea, recurrent malaria, general exhaustion and lack of fresh food were some of Hammer’s main problems. Captain Millikan, the medical officer of the 58th/59th Battalion, stated that for his weary battalion “relief from the front line is necessary”. With the campaign in its closing stages, however, relief was not possible. Examining the brigade’s health at the end of August Lieut-Colonel Refshauge of the 15th Field Ambulance made an interesting comparison: from the 2/7th, between 19th August and 1st September, 137 men were evacuated sick, while the 58th/59th sent out only 59 sick in the same period. This was despite the fact that the 2/7th had enjoyed a good rest in the salubrious Bulolo Valley after its operations in the Mubo area, whereas the 58th/59th Battalion had been continuously in action for over two months. The 2/7th Battalion, however, had been longer in the tropics and malaria had taken a stronger hold.

From the end of August the brigade began a welcome period of less strenuous activity. This included harassing the enemy, discovering whether his intention was offensive or defensive, finding his strong and weak points, obtaining information regarding tracks and terrain, reconnoitring for future attacks on Rough Hill and Arnold’s Crest, improving the line of communication, signposting the area, establishing fool-proof communications, building up supply and salvage dumps, and sending out to rest camps those who most needed rest. Patrolling never ceased, nor did the steady stream of casualties inflicted and received.73