Chapter 19: The Japanese Counter-Attack

EVEN before General Wootten had informed his subordinates of General Katagiri’s intention to attack with the 20th Division, fierce fighting had occurred along the Sattelberg Road. Before dawn on 16th October the 2/17th Battalion at Jivevaneng was heavily attacked. By the time the Japanese order of 12th October had been translated it was obvious that this thrust was part of the main plan.

At 4.45 a.m. on the 16th the Papuan platoon (Lieutenant Macfarlane1) with the 2/17th heard movement and was fired on as it withdrew into the 2/17th’s positions. By this time the enemy had crept to within 20 yards of battalion headquarters on the eastern edge of Jivevaneng and now launched a series of fierce attacks. Most of them were beaten back by components of Major Maclarn’s Headquarters Company as well as battalion headquarters. For two hours after 7.30 a.m. the main track and positions occupied by a platoon of machine-gunners and one of mortars were subjected to severe shelling from a 70-mm and a 75-mm gun. Throughout the day four more attacks were made on the battalion’s positions but all were repulsed. At 3.15 p.m. battalion headquarters was heavily mortared and, indeed, a hail of mortar bombs and grenades from cup dischargers descended upon the battalion’s positions during the day; it suffered 19 casualties including 5 killed or died of wounds. Judging from the squeals and groans many casualties were inflicted on the enemy although only six bodies were left in the area.

Colonel Simpson estimated that the attacking force was probably larger than a company. Paybooks were taken from the Japanese corpses and it was not long before it was known that the 80th Regiment was opposing the 2/17th.

There was no other heavy fighting on the 16th, but there were indications of the approach of the counter-attacking division. North-east from the 2/17th three companies of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion were holding the high ground south of the Song and the Katika-Palanko track about 1,500 to 2,000 yards west of Katika. On three occasions a forward platoon exchanged shots with parties of Japanese, apparently heading east, and a patrol skirmished with an enemy force moving east during the afternoon. Elsewhere the divisional front from Gusika to Dreger Harbour was quiet.2

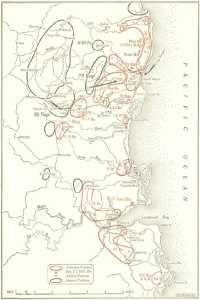

Australian and enemy dispositions, Finschhafen area, 16th–17th October

It now seemed that a Japanese force might have infiltrated between the widely dispersed companies of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion and that the expected counter-attack was imminent. “[You] must patrol vigorously,” Brigadier Evans ordered Colonel Gallasch of the Pioneers, “to prevent enemy getting in close in force.” Actually the full strength of the 79th Regiment had been infiltrating through the Pioneers and Colonel Hayashida was preparing to attack to the east.

General Wootten believed that 16th October must be the “X-1-day” referred to in General Katagiri’s order, even though there was no sign yet of the “diversion” from the north. Worried by the lack of an adequate reserve he yet felt that his two brigades were disposed as efficiently as possible to meet the threat. During darkness on the 16th, when rain was pelting down, all the Australians were watching Sattelberg for the signal fire. It seemed impossible that a fire could be lit in the steady downpour, but at 8.30 p.m. a company of the 22nd Battalion at Logaweng reported observing a large fire on Sattelberg’s dominating crest, and, according to its war diary, reported it “to Division”. For some reason, however, no report of this fire reached divisional headquarters. Indeed the divisional Intelligence summary stated categorically against 17th October that “none of the pre-arranged signs for D-day were observed by our troops”.

All along the coast occupied by the Australians, and particularly at Scarlet Beach, eyes and ears were strained seawards waiting for the threatened seaborne attack. The night was quiet until 3.15 when a heavy Japanese bombing raid began on the Finschhafen area and lasted for about two hours. Although 66 bombs were dropped there was little damage and few casualties. This heralded the seaborne attack, however, for at 3.55 a.m. on 17th October the lookout of Captain D. C. Siekmann’s coast-watching patrol at Gusika reported four Japanese barges heading south. Brigadier Evans was immediately informed and the 2/43rd stood to. A quarter of an hour later three barges almost hidden in the rain and darkness and with muffled motors were seen approaching Scarlet Beach from the north.

As planned, the Japanese in the three barges were the remnants of the 10th Company of the 79th Regiment and picked platoons from the 20th Engineer Regiment and the 5th Shipping Engineer Regiment. General Adachi himself has left the best description of what the Japanese raiders intended to do:–

“The above units, having received orders to prepare to attack the enemy’s rear by boat in connection with the division’s operations to annihilate the force which has landed north of Finschhafen, undertook intensive training for about 20 days under command of company commander 1st-Lieutenant Sugino at Nambariwa base. The men all awaited the appointed day firm in their belief of certain victory. On 16th October 1943 at the time of the attack by the division’s main strength to annihilate the enemy north of Katika, the unit received orders to penetrate the shore south of the mouth of the Song River. After drinking the sake graciously presented to the divisional commander by the Emperor, the unit vowed anew its determination to do or die and departed from the base boldly at dusk on the same day. Repulsing the interference of enemy PT boats on the way, the unit arrived at the designated point at 0230 hours on the 17th.”

It is probable that the “interference of enemy PT boats” dismissed so lightly by Adachi cost Sugino more than half his force. It will be recalled that PT boats in the early morning of 15th October reported having sunk four barges laden with troops heading South-east from Sio. It seems that Sugino’s force had originally embarked on seven barges and that three or four of these were sunk on the 15th or 16th. Thanks to the Japanese habit of carrying operation orders to the front line, the Allies were ready for the seaward attack. Wootten’s staff were right in their deduction that it would take place between 6 p.m. on the 16th and 8 a.m. on the 17th. Between these times American small craft had been forbidden to move in the area and all craft moving along the coast were to be treated as hostile.

On Scarlet Beach were two companies of the 2/28th Battalion, Captain Coppock’s3 on the north and Major Stenhouse’s4 on the south; a detachment of Captain Harris’5 10th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery (a Bofors gun); detachments of the 2/28th’s anti-tank platoon with two-pounder anti-tank guns, and of the machine-gun platoon; and a detachment of the 532nd EBSR manning two 37-mm and two Browning .50 calibre machine-guns.

At 4.10 a.m. the spotter for the light anti-aircraft detachment saw three barges coming round the north point. He immediately called, “Take post, barges” and the detachment manned the gun. At the same time Sergeant John Fuina, in charge of the American beach detachment, manned his 37-mm gun 40 yards south from the Bofors. The Americans tumbled out of their hammocks and into their weapon-pits.

It was very dark and the barges were moving quickly and quietly towards the north end of Scarlet Beach. When they were about 50 yards from the shore the 37-mm and the Bofors opened fire simultaneously, firing three and five rounds respectively. The Bofors commander saw that his rounds were high of the target, and, as he could not depress his gun, he ordered his men into their weapon-pits.

Two of the barges had now beached and were being attacked by the 37-mm, a Bren manned by two men of the 2/28th Battalion, and small arms fire from the anti-aircraft detachment. About fifteen yards from where the barges landed was a .50 Browning, manned by Private Nathan Van Noy, Junior, and his loader Corporal Stephen Popa. While the other guns of the beach defenders were firing, Van Noy held his fire until the Japanese, led by a bugler and two flame-throwers, were almost under the nose of his camouflaged gun as they leapt from the ramps of the first two barges to the shore. As they charged the Japanese threw grenades ahead and one lucky toss landed in Van Noy’s gun emplacement, shattering one of Van Noy’s legs and wounding Popa. At that moment Van Noy pressed the trigger and stopped the Japanese charge. The Browning caused great slaughter and pinned down the enemy at the beach’s shelving edge.

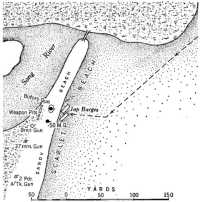

Japanese seaborne attack on Scarlet Beach, 17th October

Here the Japanese could be seen only when they moved. Grenades were now hurled by both sides, and, naturally, most damage was inflicted upon the raiders as they were exposed.

Soon after the first two barges landed the anti-tank guns farther south joined in and holed each barge, rendering them completely unserviceable. The third barge, under concentrated fire from all the defending weapons along the north shore of Scarlet Beach, made off with a number of 2-pounder shells in it.6

The enemy on the beach kept throwing grenades despite the casualties which were being inflicted on them. Van Noy put a second magazine on his gun which “traced patterns among [the Japanese] forms as they tried to crawl forward”.7 Another grenade landed in the pit, but still the gun which had done so much damage to the raiders continued to fire, although one of Van Noy’s legs was almost blown off and the other badly damaged. A third grenade landed in the pit and the gun went silent. With his finger still on the trigger the gallant American youth was dead.8 The wounded Popa managed to grab a rifle and fire a bullet into the head of a Japanese coming at him with a bayonet. When found he was alive but unconscious with the body of the dead Japanese sprawled across him.

With the light improving the Japanese were in a precarious position. Sergeant Sitlington,9 commanding the section of Bofors anti-aircraft guns, who was in the best position to see what was happening on the northern end of the beach, had already telephoned to Captain Harris and asked if more troops could be sent up as there were about 60 Japanese on the beach. He also stated that the Japanese now seemed to be trying to cross

to the north bank of the Song. Harris immediately went to Captain Cop-pock of the 2/28th, who was in charge of the beach defences, and Coppock sent a detachment northward. At first light Lieutenant Cavanagh led his platoon of the 2/28th Battalion north along the beach. In the two wrecked barges and just above the water line were 39 dead Japanese. The Allied defenders had lost one killed and four wounded. The armament carried by the raiders included flame-throwers (but their operators were shot before using them), demolition charges, mines and bangalore torpedoes. It was estimated that about 70 Japanese had landed and therefore approximately 30 must have succeeded in crawling north along the spit and across the Song.

The Japanese who escaped across the Song were seen by a coastwatching patrol of the 2/43rd stationed at the mouth of the river; they said the Japanese numbered about 30. Joshua spoke to Evans who said that the Japanese might number 100 and were to be hunted down by the company of the 2/43rd, under Captain Fleming,10 stationed on the coastal track North-east of North Hill. Between 1.30 and 2.15 p.m. Fleming’s company killed 24 Japanese and about 4 were known to have escaped. Bad security had doomed the attack from the start. The defeat of the actual landing, however, was due to the alertness and courage of a handful of gunners, engineers and infantrymen on the northern shore of Scarlet Beach.

Wars breed exaggeration. Adachi wrote in his report:–

Defying fierce artillery crossfire, the troops landed from the boats immediately. Taking up positions indicated beforehand the three platoons advanced in columns in different directions. The infantry and engineers advanced as one body creeping through the jungle. They annihilated the panic-stricken enemy everywhere, and achieved glorious and distinguished success. They killed more than 430 of the enemy, destroyed seven AA guns, five machine-cannons and MG’s and five ammunition and supply dumps. Moreover they blew up the enemy headquarters and bivouac tents, thus destroying the centre of command [these were in fact the tents of the casualty clearing station]. Raiding the area at will and with raging fury, they surprised and overwhelmed the enemy. By disrupting his command organisation they established the foundation for the victory of the division’s main strength. With the company commander as the nucleus, the entire group put forth a united effort and demonstrated the unique and peerless spiritual superiority of the Imperial Army. ... All those who fell severely wounded committed suicide by using hand grenades, and, of the total of 186 men, all except 58 became guardian spirits of their country.

To the west of Scarlet Beach the headquarters and scattered companies of the 2/3rd Pioneers heard the noise of battle from Scarlet Beach, but Colonel Gallasch had little time to wonder about it because soon after first light Japanese began to appear around his headquarters.

Unknown to the Pioneers, Colonel Kaneki Hayashida’s 79th Regiment was now assembled in strength about one mile west of Katika. The Pioneers’ skirmishes of the preceding day had really been with the advance and flank guards of this large Japanese force. Except for his companies of the I/79th Battalion detached for the diversion in the north Hayashida had the whole of his relatively fresh regiment as well as part of the III/26th Artillery Battalion. He divided his regiment

into two – the Song attacking force consisting of Major Takehama’s II/79th Battalion and the Katika attacking force consisting of Major Uchida’s III/79th Battalion. Hayashida’s intention was “to charge in and attack and annihilate the enemy located north of Arndt Point”. The general plan was for the Song force, followed by the Katika force, to penetrate “an enemy gap in the Katika-Song sector”. While Katika force held the gap Song force would attack along the right bank of the Song and then swing south. “Depending upon the progress of the Song attacking force,” stated the order, “Katika attacking force will attack and surprise the enemy in Katika from the rear and annihilate them.” Hayashida would then link up with the raiders from the sea and take them under command. Song force would attack at 4 p.m. on the 16th.

By the early morning of the 17th Hayashida’s plan had met with some success and some failure. His Song force had penetrated the gap on the preceding afternoon, a relatively easy task because of the distance between the Pioneer companies; but the landing force had been almost wiped out.

During the 17th the men of the 2/3rd Pioneer headquarters were called upon to face the 79th Regiment. The Japanese were behind the three Pioneer companies, and, if they only knew it, there was little to stop a bold and immediate attack reaching Scarlet Beach. The battalion’s armourer sergeant, Glasgow,11 and six men constituted the first patrol from battalion headquarters against a band of Japanese who were seen near a creek early in the morning. Glasgow was killed and the patrol withdrew, heavily outnumbered. A section patrol came across a strong party of Japanese decorating themselves with leaves for camouflage. In an exchange of fire the section leader was wounded and the patrol withdrew. A platoon set out for this party of Japanese who were near the battalion’s isolated “C” Company. The Japanese were found forming up for an attack on battalion headquarters. After a heavy exchange of fire the opposition proved too strong and the patrol withdrew.

At 11 a.m. the Pioneers’ headquarters on the high ground west of Katika was heavily attacked by at least one enemy company. Some of the attackers reached as close as ten yards from one platoon’s position but all attacks were repulsed. Forward of this position, which was on a hill, Warrant-Officer Curby12 watched a party of Japanese climbing upwards, and when they were about ten feet from the top, rolled grenades among them, killing at least three.

The firing then slackened and patrols scoured the area within 100 yards of headquarters in accordance with an order from Evans to “ensure vigorous patrolling to find out position of infiltration with object of bringing down artillery fire”. Soon after midday another heavy attack developed on battalion headquarters and lasted for an hour. As the impetus of the attack began to peter out Curby led 15 men armed with extra grenades round to the rear of the Japanese. Unfortunately this patrol walked into some booby-traps. After returning to headquarters with the casualties, the patrol set out again and got behind about 20 Japanese whom they showered

with grenades. The Japanese replied with heavy fire, then scattered and fled.

During the day Gallasch’s headquarters had lost 9 including 3 killed. The telephone line to his three forward companies had been cut. Gallasch needed all possible support for the Pioneers but had few automatic weapons and no mortars. His headquarters positions were slightly divided with elements of one platoon only on the steep hill overlooking the whole position. Soon after last light, at 7.20 p.m., about a company of Japanese launched what the battalion diarist described as “a furious attack” on this hill. Very heavy fire continued for ten minutes when three badly wounded men were sent down from the hill for medical attention. Another man whose own rifle had been smashed by enemy fire was also sent down with an urgent request for more ammunition and another rifle. While he was waiting for the ammunition the remainder of the platoon came down from the hill because they were short of ammunition and thus felt unable to hold on.

Whenever soldiers withdraw forlornly from a position which has previously defied enemy attempts to capture it, and which might have been held a little longer, a certain amount of consternation is bound to follow. This is particularly so if rumours accompany withdrawals to the effect that the enemy is following closely. So it was in this case and, when the Japanese appeared cheering and yelling on top of the newly-captured hill, the headquarters of the Pioneers, laden with the bulk of the reserve ammunition and rations, withdrew to Katika “to strengthen 2/28th Battalion positions”. The three forward companies were thus left on the high ground farther west without telephone communication and without a secure supply route.

During daylight battalion headquarters and part of Headquarters Company of the 2/3rd Pioneers had withstood the Japanese attack and had gained some respite for Brigadier Evans to redispose his forces. By 9 p.m. they were passing through the forward positions of Captain Newbery’s company of the 2/28th Battalion. Colonel Norman ordered Newbery to place in position all men of the Pioneers whom he wished, including those with automatic weapons, and to send the remainder to his headquarters.

In this crisis General Wootten’s divisional reserve was very slender – only part of the 2/32nd Battalion. It would certainly be beyond the capacity of the small craft of the 532nd EBSR to move his third brigade from Lae and maintain the entire division at Finschhafen. Back in Dobodura General Morshead had read General Katagiri’s captured order and had followed the early fighting as well as he could from “sitreps”. On 17th October he waited no longer and sent a message to Admiral Barbey which he repeated to Generals Mackay and Wootten.

Strong enemy attack developing Finschhafen. Desire move 26 Aust Inf Bde and one Field Ambulance from Lae to Finschhafen earliest possible. Require 14 LCIs to load personnel “G” Beach. ... Require also 6 LSTs load Buna ammunition and supplies urgently needed Finschhafen.

Without further ado Morshead warned Generals Milford and Wootten that the 26th Brigade would immediately revert to Wootten’s command and prepare for an urgent move to Finschhafen. In Port Moresby Mackay received Morshead’s signal and also Wootten’s latest report saying that the enemy was within 3,000 yards of the beach-head. He immediately repeated the request and the information to Generals MacArthur and Blamey and to Admiral Carpender. At 9.30 p.m. on the 17th, when the Pioneers were withdrawing through the 2/28th’s positions, Morshead’s senior staff officer, Brigadier Wells, rang through to General Berryman in Port Moresby and asked for the latest information about the move of the 26th Brigade. Just before midnight Berryman learnt that Barbey’s Task Force 76 would provide the 14 LCIs and 6 LSTs and would leave Buna for Lae at 2.30 p.m. on the 18th to transport the 26th Brigade to Finschhafen.

The initiative and cooperation of the senior Allied commanders in New Guinea had ensured that there would be no nonsense about reinforcement this time. Indeed, MacArthur’s signal authorising and ordering the use of Task Force 76 was received some time after arrangements had been made by the local commander. In his order to Admiral Carpender and Generals Kenney and Mackay, MacArthur stated that at the “earliest practicable date” the reinforcement would take place; the navy would transport and protect, and the air force would support “irrespective of present commitments”.

Opposite Katika and Jivevaneng the night of 17th–18th October was quiet. Indeed the 2/17th Battalion had enjoyed a relatively peaceful day – “a quiet day judging by yesterday’s standard” was the comment of the battalion diarist. During the mid-afternoon 9 Mitchells and 9 Bostons accurately bombed and strafed the Sattelberg area. Soon after dusk several units reported a large fire on Sattelberg, but the signal, if such it was, had now lost its point.

As he contemplated the battle situation in his northern area Brigadier Evans was worried by the dispersal of his troops. His companies were thinly spread from the Bonga-Gusika area in the north to the Katika area in the south; there was little depth from east to west; and moreover three of his companies were out of contact. He decided, therefore, to use part of his brigade reserve – two companies of the 2/28th Battalion – early on the 18th to clear up the situation west of Katika and to reestablish communications with the isolated companies. Thus at 10.45 p.m. on the 17th Evans ordered Norman to recapture the Pioneer headquarters position recently lost to the Japanese.

In order to keep some reserve Evans also decided to withdraw his forces from the Gusika, Bonga and Pino Hill areas, and to hold at least two companies ready to move south of the Song if required. It will be recalled that Wootten had described the area of the Bonga Track junctions as “vital ground to be held at all costs”. By 9 p.m. Joshua received orders to move his two northern companies to the mouth of the Song.

During darkness the northern companies moved south. It was hard for any commander to give up so much important and hardly-won ground, but Evans believed that he must shorten his lines and present a continuous front to the enemy. The beach-head itself between the Song and Katika was very thinly held. The five miles’ journey of the northern companies in darkness and in rain along a track ankle-deep in mud was extremely difficult and tiring, but by first light on the 18th the two companies had reached the mouth of the Song.

Because the night of the 17th–18th was quiet and because the enemy’s main attacks west of Katika and Jivevaneng appeared to have been stopped, Wootten decided to regain the initiative. At 8.15 a.m. on the 18th his operation order stated “9 Aust Div will resume the offensive immediately”. The 24th Brigade would “regain effective control of area held by it on 16th October and any posts vacated will be re-established in strength”, and would also take the first steps to capture the high ground north of the Song in the Nongora area, ready for an advance on Wareo. The 20th Brigade would “exert pressure with 2/15th and 2/17th Battalions along previous lines of advance and gain ground wherever possible”.

At 7.30 on the morning of the 18th Norman of the 2/28th gave his orders – Stenhouse’s company to lead, followed by Newbery’s, and Cop-pock’s company to move from the beach into Stenhouse’s old position on the right of Katika to protect the flank. The start time of 8.45 a.m. was delayed for 45 minutes because Coppock’s company was unable to relieve Stenhouse’s in time. At 9.15 a.m. as the companies were forming up for their counter-attack Newbery’s company on the left fired on two Japanese scouts moving down the Katika Track. A quarter of an hour later a party of Japanese was reported on the left of the track and Lieutenant Vanpraag’s13 platoon was sent out to counter any attempt at left flank encirclement. By 9.45 a.m. it was quite obvious that the West Australians would have to postpone any idea of an advance because the enemy savagely attacked Stenhouse’s company on the right. The attack was repulsed but Norman informed Evans that the attack was being made by at least two, if not three, enemy companies.

Intermittent fighting continued in the Katika-Siki Creek area. The first intimation that the enemy were thrusting south of Siki Creek was supplied by Captain Kimpton’s14 troop of anti-aircraft gunners protecting the field gun area south of Siki Creek when at 10.5 a.m. they reported that about 20 Japanese were attacking troop headquarters and one of the Bofors guns. Firing over open sights the isolated anti-aircraft and field gunners repulsed the enemy thrust. Typical of the determination of the gunners not to budge despite their lack of infantry support was Lance-Bombardier Kirwan,15 a Bofors gunner, who not only remained on the job though wounded but later went forward to reconnoitre enemy positions.

In an attempt to forestall further attacks Norman ordered Stenhouse to send out a platoon (Lieutenant Wedgwood’s16) at 10.30 a.m. to move north to a creek, west for about 500 yards, and attack the enemy on the north side of the Katika Track. While the platoon was moving forward another determined enemy attack, this time on the left flank, was beaten back.

With the Japanese attack gathering momentum Evans hastened to strengthen Scarlet Beach by arranging a semi-circle of infantry companies between the Song and Siki Creek. By the time Wedgwood’s patrol was on its way Coppock’s company together with 15 men from the machine-gun platoon had reached a position north of the Katika creek, thus closing the immediate right flank of the other companies. At the same time Fleming’s company of the 2/43rd Battalion crossed the Song and took up a position west of brigade headquarters. Although very weary, Gordon’s company of the 2/43rd which had hurried the previous night all the way from the junction of the Gusika and Wareo Tracks, known as Exchange,17 was ordered at 10.45 a.m. to close the gap south of the Song between Fleming and Coppock. Just as Gordon’s company was beginning to fill the gap the Japanese attacked. As the battalion diarist expressed it: “As D’ Company were moving into their positions just west of the old MDS position they were fired on, they went to ground and fought where they stood.” The attack was beaten off but the Japanese now seemed to be aware of the 70 yards gap between the two companies of the 2/43rd. There was also a large gap between Gordon of the 2/43rd and Coppock of the 2/28th which the latter company was ordered to fill by patrolling.

The tide of battle was summed up in the late morning by brief messages from the 2/28th Battalion to the 24th Brigade; at 11.5 a.m. “attack still going on and still determined”; at 11.50 a.m. “attack repulsed CO estimates more Japanese than own strength, he thinks they are coming in again”. Most of these attacks were made with great determination down the Katika Track but all were repulsed with very heavy casualties by the steady, controlled fire of the 2/28th Battalion whose own losses were remarkably light.

By 11.55 a.m. Wedgwood’s platoon reported being astride the track after an outflanking move in which it had killed 33 Japanese but had suffered 11 casualties. During the advance Padre Holt18 had acted as a tireless stretcher bearer. Thinking that the ground gained was hardly worth the cost Norman ordered Wedgwood to withdraw, but the platoon commander asked leave to remain as he was dominating the track from a good position. It was undoubtedly the presence of Wedgwood’s little band astride the track, together with the resolute defence of the other West

Australians and Pioneers farther west, which caused the Japanese to pause. Soon after midday there was a lull in the fierce fighting and the thrust of Hayashida’s attacking Katika force was slowed down.

His Song force which was really to lead the attack had not yet come up against such stubborn opposition. Light anti-aircraft guns of the 10th Battery were disposed in the kunai south of the Song for the protection of Scarlet Beach and also south of Siki Creek covering the position of the 24th Battery. One troop had two guns on the beach and two in the kunai about 300 yards west of it. The other troop had four guns in the kunai south of Siki Creek and two at Launch Jetty. This latter troop had already beaten back one enemy attack, firing 60 rounds over open sights.

While the attacks on the 2/28th Battalion were growing in intensity 10th Battery Headquarters and several of its guns, unscreened by infantry, were twice heavily attacked in the kunai west of Scarlet Beach. Here again the gunners fired over open sights and the attackers were halted, but not before one Bofors was abandoned and the others withdrawn under a heavy mortar bombardment. Some time afterwards Captain Harris led a party to the abandoned gun and, under fire from the Japanese 100 yards away, rendered it unserviceable. In the afternoon this Bofors was recovered undamaged and withdrawn to Scarlet Beach. Two other Bofors from the same area which had been ordered south, took the wrong turning and arrived at Scarlet Beach, making a total of eight Bofors in the beach-head area.

The guns of the 2/12th Regiment had played a big part in the battle. For two days they had been in continuous action, and had created havoc among the Japanese, particularly when shelling the massed attacks on the 2/28th Battalion. Harassing fire at night had also upset the Japanese. Katagiri had no effective counter as he had been able to bring only a few mountain guns in his trek from the north. The raiders from the sea would have done a great service to the Japanese cause had they been able to disable the Australian guns.

After two hours and a quarter of almost continuous fighting the two forward companies of the 2/28th Battalion were glad when the lull came, particularly as they were short of ammunition. At 12.35 p.m. Norman informed them that he was unable to get ammunition up from the beach apparently because of enemy infiltration down Siki Creek. Lieutenant Giles19 was therefore sent east with a patrol and at 1.50 p.m. reported the track to the coast clear. During his absence the enemy again attacked down the track towards Katika but not as heavily as before. Ten minutes before Giles’ return Wedgwood reported the track clear back from his position to the forward companies. His platoon had also taken a prisoner. It seemed that the enemy might have drawn back or that they might be trying some other plan.

Evans was anxious to plug the gaps. The fog of war was very thick over Scarlet Beach that day. Communications with the forward companies were difficult and flanking patrols from the forward ring of companies were unsure whether they would encounter friend or foe. In addition three companies of the 2/3rd Pioneers and one company of the 2/28th Battalion were isolated well behind the Japanese forward troops. The noise of near-by battle, the stray shots flicking over Scarlet Beach and rumours such as those of the beach signallers who reported hearing a grenade and machine-gun fire on the beach at 1 p.m., all helped to create uncertainty.

The Main Dressing Station established by Colonel Outridge’s 2/8th Field Ambulance about 300 yards west of Scarlet Beach and about 200 yards south of the Song had been under intermittent fire and on the 18th Outridge thought it best to move it. On the afternoon of this day, when the 2/43rd had dug in to the west, mortar bombs and machine-gun fire really began to trouble the MDS, where about 80 battle casualties were being held. One mortar bomb landed beside the dispensary and another between trenches where patients were sheltering. On his own initiative Outridge moved to the south end of the beach, his men carrying stretchers and patients, but being unable to move technical and personal gear. Evans’ staff meanwhile arranged for LCMs bringing up ammunition to take the patients to the 2/3rd Casualty Clearing Station at Langemak Bay. The beach Advanced Dressing Station and the surgical team were also sent south to assist, leaving the bulk of the MDS and one ADS (a total of eight medical officers) on the beach and one MDS on North Hill. After returning to their original position with some of the equipment next day, Outridge’s men set up the MDS below the beach embankment. Here it remained for a week treating wounded and sending some out by barge.

At 2.50 p.m. on the 18th Evans received a signal from division that the 24th Brigade must hold Scarlet Beach and as much of North Hill as would control the beach. “If any withdrawal must be to Scarlet Beach,” stated the order.

At 3.30 p.m. a report came in from the Papuan Infantry that the Japanese were 1,000 yards up the Song. Ten minutes later when attacks on both the north and south sectors of the front between the rivers had been repulsed Evans asked Joshua whether he could both hold North Hill and supply more troops for the defence of the beach-head. When Joshua replied that he could supply troops but in that case could not be responsible for holding North Hill, Evans left the forces north of the river intact, even though he was fairly certain that attacks there were of a diversionary nature.

During the late afternoon fighting was sporadic, as though the Japanese had given up trying to break through the semi-circle of the West and South Australian companies. It was soon evident, however, that they had succeeded in outflanking the 2/28th Battalion by moving to its south down Siki Creek and reaching the sea at Siki Cove. The enemy had

suffered heavy casualties – 202 dead had been counted by the 24th Brigade on 17th and 18th October – but they had reached the sea and, if they could exploit this success, the 9th Division would be in danger of disorganisation. In fact the Japanese forces, who had attacked like a bull at a gate, were now mostly bruised and bewildered, but the Australians did not yet know the extent to which their sturdy defence had disorganised the attackers.

When the Japanese reached Siki Cove Wootten signalled to Evans to “hold at all costs area inclusive North Hill and Scarlet Beach to inclusive Siki Creek”. Evans informed Wootten, however, that because of the threat to Scarlet Beach itself from west and south, he would be unable to include Katika in his defences. At 3 p.m. he sent a message to Norman saying that Scarlet Beach must be held at all costs, if necessary by a withdrawal from Katika and a strengthening of the beach perimeter extending from North Hill southwards with a depth of only 400 to 500 yards west from Scarlet Beach and having its southern flank resting on the small promontory just north of Siki Cove.

Thus at 3.30 p.m. Wedgwood’s gallant platoon was withdrawn after a long period in which it not only deflected the attack on to what was for the enemy the worst approach but commanded the track and gave warning of further attacks. At 4.45 p.m. the 2/28th began to withdraw. It must indeed have been distasteful for the men of the 2/28th to give up, without a fight,20 such a dearly held and dominating position as Katika for the sake of sitting in a tight perimeter round the beach. Uncounted piles of Japanese dead lay before the battalion’s Katika position. It was the brigadier’s belief, however, that withdrawal was necessary to prevent infiltration of the supply route, and he had the courage of his own convictions, even to the extent of not carrying out the suggestions of his divisional commander.

By last light the battalion anti-tank platoon had closed the gap between the two companies of the 2/43rd Battalion. The defensive semi-circle then ran from the Song in the north to the headland north of Siki Cove. By 8 p.m. Lieutenant Head’s21 company of the 2/28th reported in from its uneventful task north of the Song and became Evans’ slender brigade reserve. Division, brigade and battalion staffs were all busy pushing ammunition, supplies and particularly communication equipment up to the front line. By 7 p.m. the telephone line had been cut and Evans was out of communication with the rest of the division. Wireless, not always reliable, remained the only means of communication, apart from the small craft of the 532nd EBSR which continued to run to Scarlet Beach throughout the battle.

Unaware of the withdrawal from Katika, Hayashida issued an order to his 79th Regiment at 6.30 p.m.:

“1. The enemy north of Arndt Point [24th Brigade] is retreating to Finschhafen. The enemy in front of II Battalion [2/28th Battalion at Katika] is stubborn.

2. Main strength of the regiment will advance to the area south of Katika and demolish the retreating enemy.”

This was exactly what Wootten feared. Evans was now confident of being able to hold the enemy and prevent any penetration to Scarlet Beach but, as far as Wootten was concerned, by dusk a wedge was driven between the 24th and 20th Brigades. “They’re screwing the scrum,” he said to Windeyer. There were three routes into the beach-head area – the Sattelberg Road, the back track through Katika, and the line of Siki Creek – and the Japanese were now obviously advancing down the Siki. The greatest danger now, Wootten believed, was that the enemy would swing south from Katika and South-east from Siki Cove and attack through the gun and headquarters area at Heldsbach towards the supply area at Launch Jetty. This move, if successful, would isolate Windeyer’s battalions along the Sattelberg Road. In this case, the precariousness of supply and difficulty of control, added to the onslaught by the 80th Regiment might produce a grave situation.

At 10.30 a.m. on the 18th while two of his companies were patrolling towards Gurunkor and Quembung respectively, Colonel Colvin received a warning order that his headquarters and half the 2/13th Battalion should be ready in an hour to move to Heldsbach Plantation. By midday, when the diarist of the 20th Brigade commented, “There are now no troops between brigade headquarters and the enemy to the north”, two companies of the 2/13th were approaching Kedam Beach. Here they embarked on LCMs, and at 2.30 p.m. disembarked at Launch Jetty and marched to Heldsbach where the company commanders – Captains Deschamps and Fletcher – reported to Windeyer. He directed Deschamps to block the main road to the north and to protect the guns in the kunai south of Siki Creek; and Fletcher to occupy the area from the Katika Track south of Siki Creek to the coast. Windeyer also placed Captain Walker’s22 company of the 2/32nd Battalion under Colvin’s command as a reserve.

Wootten now phoned Windeyer that the loss of Katika was the most serious threat yet. Wishing to contain this threat at the bottleneck where the main road crossed the Siki, Wootten instructed Windeyer to move the three companies under Colvin to the south bank of the Siki. When Windeyer pointed out that he would then have no reserve to keep open the main track back to division, Wootten said he would make troops available if the necessity arose. Walker’s company was therefore sent forward to support the other two companies.

At 5.45 p.m. Deschamps reported that his men were in position south of the Siki. Soon afterwards Fletcher, with four platoons, was in position astride the track from Katika and thence eastward to the coast. Later in the night Fletcher reported firing from the direction of the coast but was unable to give any further information as the telephone line to his

right platoon had been cut. Firing was also heard across the cove from the 2/28th’s positions.

It was during this night – at 11 p.m. – that Hayashida, having found Katika vacated, issued another order to the 79th Regiment.

1. The night attack on the Katika position was successful with great fighting of the front line units, who captured it at 2000 hours.

2. 79th Infantry Regiment will mop up the Song and Arndt Point area as already planned. A portion will secure firmly Arndt Point and Katika against the enemies in the direction of Heldsbach. The main strength will be concentrated one kilo NW and make preparations for the future attacks.

Hayashida’s main strength was to be assembled and reorganised northwest of Katika for an assault on Heldsbach and then Finschhafen. When Fletcher re-established contact with his right platoon (Lieutenant Suters23) early on the 19th, Suters reported that he had repulsed two attacks from Siki Creek during the night. These proved to be the last attempts by the enemy to strike south. But for Wootten’s skilful generalship and the rapid advance north by half the 2/13th Battalion the Japanese might have been able to seize important ground south of the creek that night.

The enemy was also active on the other side of the creek and cove. Half an hour before midnight a platoon of the 2/28th in an outpost position forward of the left flank – Lieutenant Vanpraag’s – reported hearing Japanese voices. Just after midnight fresh movement was heard and at 1.30 a.m. an enemy force of about 50 began to attack Vanpraag’s positions. The attacks consisted of a series of short hard thrusts and continued for two hours. When the platoon’s listening post was overrun and one man killed, Norman ordered Vanpraag to withdraw to the high ground on the right flank of a detachment of the 532nd EBSR overlooking the cove.

Meanwhile the attacks by the 80th Regiment against the 2/17th Battalion at Jivevaneng had met with little success, although, as the battalion’s diarist noted on the 18th, “this morning revealed that the enemy had cut the main Sattelberg Road to our east and was sitting astride the track”. A patrol early in the morning estimated that about a platoon of Japanese was on the track east of Jivevaneng; at 1.15 p.m. another patrol reported that the position was stronger than that. The area was shelled and small skirmishes took place west, north and east of Jivevaneng. Japanese snipers, mortar bombs and grenades from cup dischargers made things unpleasant for the defenders. As the main route was cut, there was some anxiety about a supply route for the 2/17th Battalion.

At Kumawa all was quiet and the 2/15th Battalion was ordered to patrol aggressively towards the Siki and the Sattelberg Road. Patrols scoured the area on the 18th but only one saw any Japanese. Although the 2/15th’s part in the battle on this and succeeding days was not a spectacular one, the threat to its rear caused the 80th Regiment to detach a considerable proportion of its strength to watch the southern flank

with a resultant decrease in the force available for use against the 2/17th. About this time a route into the 2/17th’s positions from Kumawa was found and thereafter a 2/15th platoon escorted a native carrying party to the 2/17th each day until the Sattelberg Road was opened.

The Japanese of the 80th Regiment in this more static fight along the Sattelberg Road and Kumawa Track had more time for contemplation and therefore for diary writing than did their more hard-pressed comrades of the 79th Regiment to the north. “I eat potatoes and live in a hole,” wrote one infantryman, “and cannot speak in a loud voice. I live the life of a mud rat or some similar creature.” “What shall I eat to live?” wrote another. “What has happened to the general attack ... the enemy patrol is always wandering around day and night.” A third was more sanguine: “Heard that [79th Regiment] has forced the enemy in the sector of Arndt Point to retreat. This is the first good news I have heard since I left for the front.”

To the south two companies of the 22nd Battalion came under command of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion on arrival at Kakakog, thus giving Wootten a slightly larger but still inadequate divisional reserve. Two companies of the 2/13th Battalion were watching the Mape River track junctions and Tirimoro and were now part of “Kelforce” – under the command of Major Kelly24 at Simbang.

The three missing companies of the 2/3rd Pioneers had been seen by Tac R planes waving to the aircraft, still in the positions they had been ordered to hold, and apparently not in difficulties. As they had three days supply of rations and ample ammunition, there was little cause for anxiety on this score, although there was a scarcity of water. Wootten decided, however, that as they were no longer in a position to affect the course of the battle they should be withdrawn. At 4.30 p.m. he ordered Windeyer, whose headquarters could make contact with one of the companies, to arrange for them to move south to the Sattelberg Road, where they would come under his command.

Actually, the three Pioneer companies had carried out the tasks allotted to them. It was not their fault that the 79th Regiment had been able to infiltrate to the east. Rather was it due to the extensive gaps covered by thick country between the companies, and to skilful Japanese fieldcraft All day long on the 18th the companies had heard the noise of battle behind them seeming to get nearer to Scarlet Beach. The northern company – Major P. E. Siekmann’s less one platoon on standing patrol 2,000 yards away on the Song – had been out of communication since last light on the 17th. At 7 o’clock next morning the company opened fire on five Japanese approaching from the east. Two of them were killed, one proving to be Major Takehama, commander of the II/79th Battalion. As usual, detailed operation orders for the landing and thrust towards the beach were found on the dead officer.25 When the Pioneers approached to

examine the body they found a Japanese watching over it. He promptly killed himself by exploding a grenade in his face. At midday the Japanese, doubtless surprised at finding a strong Australian position astride the line of advance of their Song force, attacked but were repulsed. The Australians, now on only two meals per day, stood to throughout the night.

Captain Knott’s company – farthest west along the Katika–Palanko track – spent the day patrolling to find the company to the east and to pinpoint the Japanese attacking the 2/43rd Battalion. As the company was out of communication with all 24th Brigade formations, Knott signalled Windeyer late in the afternoon outlining his situation. The third isolated company (Lieutenant Dunn’s26) was out of communication with all other units and sub-units.

Thus, by 19th October, the 20th Japanese Division had succeeded in splitting the 9th Division into two groups divided by Siki Creek. But the Japanese, depleted and disorganised by the defenders, for the next three days failed to follow up their success. For their plan to succeed it was essential that the thrust to the coast should be vigorously exploited before the Australians, with their more secure lines of supply and reinforcement, could reorganise and regain the initiative. Wootten now fixed the brigade boundary as Siki Creek, the creek being inclusive to 24th Brigade, and ordered Evans to re-establish contact with the 20th Brigade and drive the enemy from the Siki Cove–Katika area.

While Evans at 6.30 a.m. on the 19th was instructing Norman by telephone to patrol to the Siki, the enemy in the creek made several more sharp attacks on Newbery’s positions to the north. All were repulsed, and then the battalion’s mortars bombarded the general area of the enemy positions near Siki Cove. After this action had died down, Evans ordered a vigorous patrolling policy to gain information for the attacks ordered by divisional headquarters. Patrols were to leave Coppock’s and Sten-house’s companies of the 2/28th and reconnoitre to the west for between 1,000 and 1,500 yards, while another patrol from Head’s company was to try to make contact with the 2/13th Battalion across the creek. The patrols were to depart at 10 a.m. and return with information about 3 p.m., and none was to become involved in heavy action. Just before they moved out Evans informed Norman that he expected that the main enemy force had withdrawn to the west, because of the high casualties suffered on the 18th, and because of the effectiveness of the artillery fire.

The patrol from Coppock’s company returned within an hour after a skirmish with about twenty Japanese 350 yards to the west. A patrol led by Sergeant Stark27 returned at 12.15 p.m. after penetrating a considerable distance to the west without making any contact with the enemy. Norman then asked permission to attack Katika. He believed that the enemy had suffered about 50 per cent casualties and considered that if

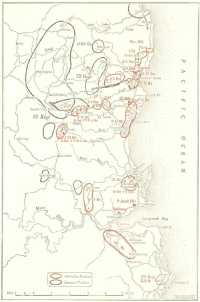

Australian and Japanese redispositions, last light 18th October

the high ground west of Katika were harassed by mortar and artillery fire, the enemy would probably move down to the village. He felt that the Japanese would not expect an attack over the difficult northern route reconnoitred by Stark. Evans agreed to the plan.

Meanwhile, a patrol led by Lieutenant George,28 had been attempting to make contact with the 2/13th Battalion. It moved west for 200 yards, then south to the creek on the east side of Katika. George returned at 1.40 p.m. after meeting an enemy party near the creek. The enemy, who were using a telephone line, were warned of George’s approach by a native and withdrew hurriedly towards the coast. Four other small parties of Japanese were observed along the creek. One Japanese was killed and the patrol was fired on twice. Although George did not join the 2/13th Battalion, the skilful fieldcraft of his men had pinpointed several enemy positions which could now be engaged by artillery and mortars. Half an hour before, the Japanese had disclosed more of their positions when they fired on American barges off Siki Cove.

At 3.50 p.m., after Major Rosevear’s29 composite company from the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion had taken over the positions of the attacking companies, Coppock’s company of the 2/28th followed by two of Head’s platoons set out along Stark’s difficult route. The artillery shelled the track well to the west of Katika while the battalion’s mortars concentrated on Katika and the near-by spur. The Japanese defenders were completely surprised when the Australians attacked from the north, and doubtless were also surprised by the speed with which the Australian counter-attack followed withdrawal. Soon after 4 o’clock Lieutenant Rooke’s platoon brushed aside the slight opposition encountered and by 5.45 p.m. the high ground immediately west of Katika was recaptured for the loss of one man killed. The battalion diarist commented gleefully: “Enemy ... appear slightly peeved and evidently had not appreciated the possibility of our reoccupation of these positions.” The attack, based on information from excellent patrolling, had come in to the west of Katika and the two companies had regained the vital area so reluctantly vacated by the other two companies on the previous day.

After two hectic days the companies of the 2/43rd Battalion were glad of an easier one on the 19th. “Position seems a little better this morning,” wrote their diarist. North of the Song the front was quiet. West of the perimeter from the Song to the 2/28th Battalion a patrol skirmished with a small Japanese party soon after midday. In the late afternoon another patrol found 14 dead and 27 sets of equipment in front of its company’s positions.

Elsewhere along the divisional front the situation was reasonably quiet while the Japanese paused and reorganised. Later in the afternoon Lieu-

tenant Suters of the 2/13th took a patrol to the mouth of the creek but was fired on from the north bank. Returning to his platoon overlooking the Japanese track to the Siki, he was able to report by 5.30 p.m. that his men had sniped twelve Japanese moving west from the creek towards Katika. Brave though they were the Japanese often displayed incredible stupidity. In this case they followed the same track each time and crossed the open ground stopping to look at their dead comrades. Thus they were easy targets.

On the southern front the commander of the Japanese 80th Regiment must have been feeling very frustrated at this stage, for the 2/17th Battalion simply refused to budge. By this time it was no new experience for the battalion to be surrounded by Japanese, or at least to have its main supply route severed. The battalion was annoyed, rather than alarmed, that the Japanese had established a strong post to the east between Captain Rudkin’s company of the 2/17th and Captain Richmond’s company of the 2/43rd. At midday artillery shelled the troublesome Japanese pocket but the Japanese moved closer to Rudkin’s company during the shelling and afterwards hopped back into their holes. The 2/17th’s worry about supply was reduced when at 4 p.m. Sergeant Allman30 of the Papuans guided a patrol across country from Tareko 2 to Jivevaneng. In the patrol was Major Broadbent, now released from his duties at the beach. By this route stretcher cases and walking wounded were evacuated to Tareko 2 by last light despite a Japanese patrol which chased them for half the way.

During these days of uncertainty Captain Gore’s Papuan company had been playing a notable role. His third platoon – Lieutenant Bruce’s – had rejoined the company after harassing the stragglers of the 51st Division in the ranges north of Lae, and was now helping to patrol the Heldsbach area. Lieutenant Macfarlane’s platoon was patrolling mainly for the 2/17th Battalion, while Lieutenant Rice’s had been reconnoitring the Fior-Wareo area for three days. It reported on 18th October that there were heavy Japanese troop concentrations near Palanko, that strong positions were dug east of Sattelberg and along Siki Creek, and that the enemy was heading for Katika. On the 19th this platoon reported the coast track clear as far north as Bonga, although it saw two Japanese patrols in that area.

Meanwhile the isolated companies of the 2/3rd Pioneers, who had not yet received Wootten’s order to move south, had been playing their parts in forcing the Japanese to pause. Richmond’s company of the 2/43rd Battalion on the track to the east of the 2/17th was keeping contact with the Pioneers. At 12.45 p.m. on the 19th a combined patrol from Richmond’s company and Knott’s company of the Pioneers attempted to destroy the enemy blocking the track to the 2/17th, but were forced back under fire from eight machine-guns. In the afternoon Knott’s company moved south and took up a position near Richmond’s.

With the other two Pioneer companies, however, there was no communication. At first light a booby-trap set in front of Lieutenant Dunn’s company on the Katika Track exploded and heralded an attack. After a pause during which the Japanese held what the battalion diarist termed a “corroboree” the company was heavily attacked. It held its fire until the Japanese were close and then opened up, killing at least 20 and causing the attackers to withdraw to a gully on the right. Grenades hurled by the defenders into the gully caused more casualties and another withdrawal. At 10 a.m., when Dunn was about to send back a patrol to make contact with his battalion headquarters, which he imagined to be in its original position, the Japanese came charging again up the steep slope of the gully, yelling. They were again easily repulsed, mainly with grenades. On the high ground to the north Major Siekmann’s company repulsed an attack in the morning, largely by mortaring the enemy’s forming-up place south of the Song. Documents and maps were later taken from dead Japanese, and swords, which were later given to pilots of the supporting Boomerangs.

The night 19th–20th October and the 20th were quiet and there was no interference with the 26th Brigade which loaded into Admiral Barbey’s landing craft at 6 p.m. on the 19th and arrived in Langemak Bay from Lae just on midnight. Japanese bombers came over a little later, but they did no damage. South of Langemak Bay the landing craft were fired on from an enemy submarine but it did not come close enough to do much damage.

Accompanying the 13 LCIs of Brigadier Whitehead’s brigade were 3 LSTs, one carrying a squadron of the 1st Tank Battalion.31 Major Ford32 of this battalion had investigated the Finschhafen area on 9th October and reported that “tanks could have operated in small numbers”, and that “infantry enthusiastic and require tanks to deal with strong points”. Referring to the coastal crossing of the Bumi he reported: “Six tanks would have dealt successfully with strong enemy bunker positions, would have reduced infantry casualties and speeded up advance.” Early in October, however, there was no indication that the tank squadrons would be used. Normal training continued. Then events best described by the battalion’s diarist began to occur:

The event of the month has been the departure of “C” Squadron group to Finschhafen. On the 18th, the squadron was put on six hours’ notice to move and they left by LST the next day at 3 o’clock. Nine officers and 136 O.R’s embarked. The orders strictly limited the number of vehicles to be taken to 18 tanks, 5 jeeps and trailers, 1 slave carrier33 and 1 fitter’s carrier. Ten days supply of rations, ammunition and POL had been taken on at Buna and the loading of vehicles and personnel was completed in fifty minutes.

An LST with Major S. Hordern’s “C” Squadron aboard sailed in convoy at 3.30 p.m. on the 19th and at 3.30 next morning with steady rain falling the ship began to unload at Langemak Bay.34

An unloading party met the ship (said the battalion’s report) but appeared to have little or no organisation and showed a desire to watch the tanks rather than unload, and squadron personnel unloaded the greater bulk of the stores which were packed in the tank deck, and some confusion was caused by unloading both tanks and stores together. The narrow strip of beach and the track from the beach was soft and muddy. Operations were done under blackout conditions as enemy aircraft were attacking shipping farther out in the bay. The ship’s commander had expressed his intention of leaving in one hour irrespective of whether all stores were off. Stores were being dumped at the unloading point causing much congestion. A number of tanks got off, then one bogged on the track just clear of the beach, and the remainder had to be diverted and a detour made through thick secondary growth necessitating a sharp turn on the soft beach. Despite these difficulties all vehicles were unloaded and moved off the beach. ... At 0430 the LST commenced to move away with large quantities of POL, ammunition and rations still on board. Men were still throwing ammunition off, and jumping into the water themselves with the ramp half up.

Evans was now mainly concerned to strengthen his positions at Katika and to eliminate the Japanese pocket in Siki Cove and North-east of Jivevaneng. In support of the infantry the artillery pounded the Japanese positions. About midday the men of the 2/28th’s forward companies watched the shells falling among the Japanese again massing west of Katika. Late on the 19th Norman issued orders to Stenhouse’s company to mop up the enemy positions between the battalion’s forward localities and Siki Creek next morning. The idea was that this company should advance South-east across the track joining the beach and Katika and reach the cove, where it would reorganise and advance South-west.

At 8.38 a.m. on the 20th, with two platoons forward, Stenhouse moved out to attack the Japanese position on the razor-back ridge south of Newbery’s company overlooking the cove. By 9.26 Lieutenant Giles’ platoon was heavily engaged with the enemy on the ridge and was pinned down by machine-gun fire. Lieutenant Wedgwood’s platoon then attempted a left encirclement, but was stopped too. Despite the example set by leaders such as Lance-Corporal Nankiville,35 who was seriously wounded but continued to lead the point section, all further attempts to dislodge the enemy were unsuccessful. Losses mounted and by the time that Sten-house had only 42 men left, Norman decided to withdraw the battered company.

Although the attack was unsuccessful the enemy machine-guns had been located and they were now subjected to a merciless bombardment. At 2.30 p.m. the Vickers were placed forward to harass the cove. “This caused considerable retaliation by the enemy,” wrote the 2/28th’s diarist, “and terrific fire-fight ensued causing mild panic amongst beach defence

personnel who thought enemy were breaking through.” Eventually the Japanese machine-guns were silenced, mainly by 3-inch mortar fire. Across the cove Captain Fletcher’s company of the 2/13th heard the fight and at times could see Stenhouse’s men. The 2/13th had located machine-guns on each side of the main track on the north bank of Siki Creek and let the 2/28th know by the only means possible at this time – wireless.

As the two battalions-2/28th and 2/13th – were now so close it became more imperative to re-establish telephone communication. Back in his headquarters at Langemak Bay Wootten had been unable to follow the battle for Scarlet Beach as clearly as he would have wished since the severing of the telephone line to the 24th Brigade. At 3.30 p.m. Lieutenant Cavanagh led a patrol from Coppock’s company of the 2/28th in an attempt to make contact with the 2/13th. While the patrol was away the battalion ration party, returning from the forward companies to battalion headquarters, was ambushed at a spot described by the brigade diarist as a “nasty position”; it was indeed nasty as this small Japanese party “controls water of ‘A’ and ‘B’ “. An hour and a half after leaving Katika, Cavanagh arrived without incident at Lieutenant Hall’s position south of Siki Creek. He was taken to see Colonel Colvin who suggested that Cavanagh should return to Katika laying line behind him, and that Stenhouse should push down the coast to the mouth of Siki Creek and join his own company there. Cavanagh explained that Stenhouse had been trying to do just that. At 6.15 p.m. Cavanagh returned to Katika laying the line behind him and thus re-establishing contact between the 20th and 24th Brigades. Evans promptly asked Wootten for his third battalion – the 2/32nd – then divisional reserve in the Heldsbach area.

Around the remainder of the front the pressure of the past few days was not so fierce on the 20th. The Japanese pocket east of Jivevaneng was attacked by Knott’s Pioneer company after supporting mortar fire had missed the pocket and landed in the 2/17th’s positions. Starting at 2.30 p.m. it took the two forward platoons an hour and a half to bash their way 100 yards through the thick jungle. Forward scouts were just below the Japanese position before they were pinned down. There Private Minter36 stood up and fired two magazines at the Japanese, thus allowing his comrade to escape. The company then withdrew after the wounded Minter had pinpointed the enemy positions on the track. At 7.40 the enemy attacked Knott’s company, but were repulsed.

Five minutes later the Japanese attacked the two companies of the 2/28th in the Katika area. At 9.10 Coppock’s company reported that the enemy had dug in all round the Australian positions and that an attack was expected during the night.37

Meanwhile, what of the two lost companies of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion? Lieutenant Dunn’s company was still in position along the Katika Track. It had given no ground and had repulsed all attacks. By the 20th the men were on quarter rations. At 11.45 a.m. a Boomerang dropped a message which stated: “Stragglers instructed to come in moving south to road Sattelberg to Heldsbach or direct to Scarlet Beach. Destroy weapons abandoned. Carry all possible.” Resentful at the unfortunate term “stragglers”,38 the company marched out at 1.30 p.m. with all its weapons. On the way to the beach it met several Japanese parties and killed four men. At nightfall it bivouacked on the side of a valley just off the Katika Track.

Major Siekmann’s two platoons had also maintained their positions without wavering, and, judging by the odour of death wafting in from the south side of their position, they had caused many casualties. At first light on the 20th the company was subjected to Australian artillery fire. Siekmann therefore made a huge sign with bandages and blankets: “AIF, SOS” At 11.15 a.m. a Boomerang spotted the sign and dropped cigarettes and tobacco. Half an hour later the Boomerang dropped an identical message to “stragglers”. Siekmann and his men were riled by this message, and decided to stay where they were as they did not regard themselves as stragglers. A new sign was displayed: “C.140 (the company serial number) here awaiting orders.” Though the company was shelled again by its own artillery it refused to move, and at 4.45 p.m. its message was seen by an aircraft.

These two resolute companies of Pioneers had given an admirable example of what Wootten was constantly drilling into his infantry battalions, namely, that in holding defended localities the Japanese might be behind the Australians but the Australians were also behind the Japanese. The Pioneers had not borne the brunt of the main attack, but their very presence in the rear caused concern and uncertainty to the enemy. In some quarters it became fashionable to blame the Pioneers for letting the 79th Regiment through without notice, but it was too much of a tall order to expect the three companies, situated as they were, to cover the whole area between the Song and the Siki.

The Japanese counter-attack had been halted, and Wootten now had his third brigade on hand. He believed therefore that he had a chance to regain the initiative and issued orders aimed at achieving this. One battalion from the 26th Brigade (2/23rd Battalion) would become divisional reserve near the Quoja. In accordance with Evans’ request, the 2/32nd Battalion would move by sea to Scarlet Beach to rejoin the 24th Brigade. All elements of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion would be sent to Finschhafen. As soon as the Pioneers reached Finschhafen the two companies of the 2/13th Battalion at Kakakog would rejoin the remainder of the battalion, which, in its turn, would be relieved by the 26th Brigade, and would move up the Sattelberg Road to support the 2/17th. The

26th Brigade, less one battalion, would take over the sector from south of Siki Cove to the bend on the Sattelberg Road north of Heldsbach. Evans and Whitehead would then cooperate in driving the enemy from the Katika-Siki Cove area and advance west of the main coast road. Two troops of the tank squadron were allotted a defensive role in Timbulum Plantation south of Langemak Bay and the third was moved in LCMs to Kedam Beach and thence to near Pola.

By first light on the 21st the attacks expected by Norman on his two forward companies had not taken place. At 7.30 a.m. Lieutenant Hindley led his platoon from Newbery’s company to “clean up” the Japanese ambush position astride the supply route to the two companies overlooking Katika. A quarter of an hour later Newbery’s men fired on a party of 15 Japanese heading west from Siki Cove and killed 6. At 7 a.m. Captain Davidson’s39 company of the 2/32nd Battalion left for Scarlet Beach aboard an LCV and arrived about three hours later. Evans told Norman that if Hindley’s patrol got through Davidson’s company would be placed in “three platoon localities” between Katika and the beach.

At 11.45 a.m. Coppock reported that Dunn’s company of the 2/3rd Pioneers had come in. Moving out at 7 a.m. the Pioneers had skirted a Japanese position and then advanced through an area pock-marked by Australian shells. Here they killed two Japanese and then bashed a track through the jungle until they again came to the main Katika Track at their old battalion headquarters position. Several enemy and one Australian dead were lying there. Pushing farther east they came to the battalion’s former “B” Echelon area and were chagrined to see abandoned mail strewn about.

Just west of Katika they were challenged by the 2/28th Battalion. They replied with a password several days old. It was not immediately accepted, but all doubts were removed when one of the 2/28th whistled “Waltzing Matilda”, and the Pioneers replied and thankfully entered the positions. Having been without rations for the past day the men were affected by strain, hunger and thirst. They were made as comfortable as possible by the West Australians who at this time were short of rations themselves because of the enemy ambush position astride the supply route. The outcome of Hindley’s patrol was therefore awaited with interest.

At 12.35 p.m. Hindley reached Coppock’s company of the 2/28th without opposition and was ordered to return immediately escorting a ration party. Two hours later a formidable patrol left for Katika – David-son’s company of the 2/32nd escorting the 2/28th’s ration party. By 5.10 p.m. the rations arrived in the forward area. Davidson’s company now occupied the gap between Norman’s two forward companies and Stenhouse’s company.

Siekmann’s missing company of the 2/3rd Pioneers reported in to Evans’ outposts at 6.25 p.m. At 9.15 a.m. a Boomerang had dropped another message: “You will rejoin main body North Hill, Scarlet Beach

or Zag. Suggest route crossing Song River moving along it to North Hill.” A quarter of an hour later a plane dropped three canisters of ammunition. Siekmann already had plenty of ammunition and was hoping for some rations. The company-80 men strong with one 3-inch mortar and two Vickers guns besides the usual weapons of two infantry platoons – then buried the surplus ammunition and marched out to the north in single file after a meal of hot stew and with only one tin of bully beef a man left. Since the mortar was too heavy its firing pin and sights were removed and it was buried. To facilitate carrying, the Vickers belts were cut in halves; 400 grenades were carried. Through the kunai and jungle the company marched to the Song River, which was reached at 3 p.m., when it was bombarded by a mortar of the 2/43rd Battalion. A shout of “Ho, ho, ho, ho” caused the mortarmen to cease fire. Because the area was strewn with booby-traps the company moved down the centre of the Song to brigade headquarters, where the men were well fed and the two Vickers used to thicken the defences.

In Windeyer’s sector south of Siki Creek preparations were made for Brigadier Whitehead’s two battalions to relieve the 2/13th Battalion. At 9 a.m. the company commanders of Colonel Ainslie’s 2/48th Battalion left to reconnoitre the positions occupied by Colvin’s companies. Colonel Gillespie’s 2/24th reconnoitred the Heldsbach area and the 2/23rd, now commanded by Lieut-Colonel Tucker,40 remained in divisional reserve. By 1.30 p.m. the 2/48th began relieving the 2/13th, and the 2/24th took over in Heldsbach.

The 21st was a fairly quiet day for the 2/17th and 2/15th at Jivevaneng and Kumawa respectively. The Japanese force astride the Sattelberg Road east of the 2/17th Battalion was well entrenched and had been reinforced. As Simpson was unable to deal with this enemy pocket to the east as well as counter the main enemy attack from the west, Windeyer decided to send the 2/13th Battalion up to open the Sattelberg Road to Jivevaneng.

By last light on the 21st the tide of battle seemed to have turned in the Australians’ favour. Had the enemy not allowed three days to pass without making a major move the tale might have been different. On most fronts during the night the enemy were heard digging in; fires and flares, probably signals, were seen from the direction of Sattelberg. It seemed possible that the enemy might make another attack on the 22nd, but the Australians, reorganised and redisposed, would be ready for him. Already the 24th Brigade estimated that about 500 Japanese had been killed by it since 15th October. Round the valiant 2/28th there were literally piles of dead.

As expected there was much activity on the Katika front on the 22nd. From early morning the 2/28th was alert. At 8.50 a.m. forward companies reported enemy movement to the west. As all reports seemed to indicate a Japanese withdrawal, Norman prepared to push his defences farther west. At 10.10 a.m. Dunn’s company of the 2/3rd Pioneers was sent

to establish a firm base on the track and creek junction. By 11.45 a.m. a patrol from Newbery’s company reported that the area of the cove and the creek was clear and that they had met the 2/48th Battalion across the creek. The patrol found that the area previously attacked by Sten-house’s company had been occupied by at least 200 Japanese!

By 12.30 p.m. Brigadier Evans ordered the 2/28th to move about 500 yards. to the west. Coppock’s and Head’s companies were hardly settled into their new areas when at 7.45 p.m. the Japanese made a determined charge straight down the track from the west. Although under cover of machine-guns mounted about 150 yards forward of the Australian positions, and urged on by a bugle call, the Japanese were driven back with heavy casualties. The brunt of the attack was borne by Lieutenant Rooke’s platoon astride the track. Ably assisted by his section commanders, Corporal Isle41 and Lance-Corporal Broun,42 Rooke and his platoon heavily defeated the enemy attack.43 A similar attack but less bold was beaten off 20 minutes later. Five minutes before midnight they attacked again but were easily repulsed. The 2/28th Battalion had played a key role at a crucial time in the defence of Scarlet Beach.

The moving of the 2/28th Battalion 500 yards west had dislocated the Japanese plans for an attack on positions near Scarlet Beach by the II/79th Battalion. An operation order issued after the 2/28th Battalion’s move stated that at dusk “II Battalion will attack the enemy [2/28th Battalion] in front of 8 Company before attacking the enemy boat landing point”. As already described the three attacks made on the 2/28th Battalion were all easily repulsed.

Elsewhere in the 24th Brigade’s area the day was reasonably quiet. An Australian and Papuan patrol from Captain Grant’s company of the 2/43rd Battalion on North Hill reached Bonga and Oriental and found them deserted and undistributed stores abandoned. The remainder of the 2/32nd Battalion arrived at Scarlet Beach and at 1.30 p.m. Lieutenant Denness’ company left for Katika, where at dusk it dug in.

At last light on the 22nd General Katagiri changed his tone somewhat, and brought two companies of the I/79th Battalion into the battle to support the battered II and III Battalions.

“1. The enemy is gradually increasing his strength in Arndt Point area. The enemy has increased his strength in R. Song area. They have their eyes towards Wareo. A portion of the enemy in Kumawa area is advancing towards Sisi–Sattelberg heights. ...

2. The [79th Regiment] will attack the enemy in the east of Katika at daybreak of the 23rd and secure the line firmly. From 1000 hrs execute an attack on the enemy [2/32nd Battalion] constructing the position. Direct the main strength to the right flank and attack.

3. Other units will continue their present duty.”

With enemy confidence and morale waning the stage was set on 23rd October – the anniversary of El Alamein, as various diarists noted – for a further reorganisation of the Australians in preparation for a resumption of the offensive. The 20th Brigade was now compact in the Kumawa and Jivevaneng areas; the 26th also had a specific task in the area from the Siki to Heldsbach. In the 24th Brigade it was imperative to sort out the battalions whose locations and tasks had become mixed during the Japanese attack. Thus orders were issued for the 2/43rd Battalion to hold the area on the right from the coast through North Hill to the Song; the 2/28th, aided by a mixed force of Pioneers under Major Rosevear, to hold the centre from the Song for 1,000 yards south; and the 2/32nd thence to the Katika and Siki areas where it would link with the 26th Brigade.

The two leading companies of the 2/32nd were hardly in position on an excellent feature 300 yards west of Katika when the Japanese arrived hoping also to occupy it. Indeed, just before arriving in one position, the point section, led by Corporal Scott,44 routed an enemy patrol of fifteen. At 3.15 p.m. the Japanese attacked. This attack and several others which came intermittently during the late afternoon, were repulsed. Soon after dusk at 6.20 a heavy attack developed along the track, but as the enemy made no change in his tactics or in his line of approach this also was driven back. The enemy’s only fire support was from machine-guns while the Australians had mortars and machine-guns, and the artillery had registered the area. All this meant more casualties for the Japanese round Katika; before its departure the 2/28th had counted 308 corpses on the north side of the track alone. The enemy continued his attacks during the night, but none had the slightest success.

On this day, 23rd October, General Morshead visited General Wootten at Finschhafen. They decided that before the 9th Division could resume the offensive a further brigade (probably the 4th) was needed. Wootten said that he would have to attack Sattelberg and Wareo before advancing to Sio, and would like to attack them simultaneously. He would probably be able to do so if the extra brigade were available, but if not, he would have to attack the two strongholds in succession. Morshead then signalled Mackay in Port Moresby: “At present am wholly disposed along northern sector. Langemak Bay area inadequately held against possible seaborne attack. Present average strength battalion 600. To enable resumption of offensive at first opportunity and to provide effective defence Langemak area consider another brigade required.” Mackay quickly decided that it would be best to send the remainder of the 4th Brigade, and he also decided to send General Berryman forward to investigate.