Chapter 20: In the Ramu Valley

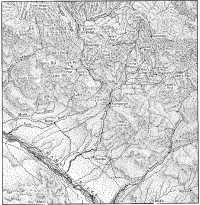

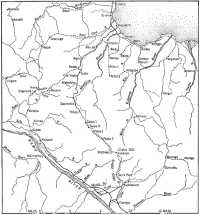

WHILE the 9th Division was locked in fierce and decisive conflict with the main striking force of the 20th Japanese Division, the 7th Australian Division had been fighting its own smaller campaign far to the west in the Ramu Valley and the foothills of the Finisterres. Both opposing commanders in New Guinea, General Mackay in Port Moresby and General Adachi in Wewak, had been watching the outcome of the Finschhafen operations with grave anxiety. While it was going on, the subordinate commanders in the Ramu Valley, Major-General Vasey and Major-General Nakai, were each instructed to hold what they had, to patrol extensively and attempt no big advances.

These orders were conveyed to Vasey in a Corps instruction the day Dumpu fell-4th October. They confirmed verbal instructions given to him by General Herring at Lae on the 1st. The 7th Division would now concentrate in the Dumpu-Marawasa area, but would make no advance “in strength” beyond Dumpu without reference to Corps headquarters. One battalion would be left for the protection of the Kaiapit airfield area and “adequate” troops would remain on the Bena Bena-Garoka plateau to guard the American air installations and radar equipment. Responsibility for the protection of Nadzab and control of the 15th Brigade passed to Major-General Milford of the 5th Division on 3rd October.

Late on the 4th, after a company of the 2/16th Battalion had secured Dumpu, Brigadier Dougherty of the 21st Brigade received an order from Vasey to “prepare to move in strength to Key Point 3”. This was a point shown on captured Japanese maps and seemed to be on the line of communications along which the Australians thought the enemy was withdrawing. From the little information available Dougherty believed that Key Point 3 was where the Japanese track crossed the Uria River but, because the maps of this area were very sketchy, he could not be sure. Actually, what the Japanese called “Key Points” were really staging points and supply dumps.

On 5th October there was a general move forward – the 21st Brigade into the Dumpu area and into the foothills and the 25th Brigade into the Kaigulin area. By midday the 2/16th Battalion in Dumpu was digging a defensive position. Among the equipment captured at Dumpu was a crate of silk lap laps; later in the day one company paraded in the coloured lap laps while their newly-washed jungle-greens were drying. A patrol moved out with Major Duchatel of Angau who reported a suitable area for a landing strip about 2,000 yards long which could be made ready by the morning of the 6th. Other patrols moving out from Dumpu in all directions met no Japanese. One returned laden with zebu steaks but, said the battalion’s report, “the spirit in which the steak was tackled was willing enough but on this occasion the flesh was far too strong”.

Dumpu was about 3,000 yards from the Ramu River and south of the Uria. To the newly-arrived battalion it seemed an ideal spot for an air supply point.

Dumpu was destined to be of major tactical importance in the later stages of the campaign (said its report). The primary object of the current operations had been to clear the enemy from the valley and establish (and protect) a fighter strip as a base for air operations against Bogadjim and Madang on the north coast of New Guinea. This fighter strip was already in process of development at Gusap and the role of 21 Brigade now was to assist in its protection. This would entail taking up defensive positions north of Gusap and in the Finisterres. To maintain these protective forces an air supply point was vital – and even more so if later attempts were to be made against the Jap roadhead at Daumoina about fourteen miles away.

Dougherty planned that Lieut-Colonel Bishop’s 2/27th Battalion would lead the advance into the Finisterre foothills. Before doing so, however, it had to be relieved from its task of making a road from Kaigulin to

the Surinam River. The 2/14th Battalion was therefore recalled from the Wampun area, scene of its stiff fight on the previous day, and relieved the 2/27th Battalion on the 5th. The 2/6th Independent Company relieved the 2/14th in the Wampun area, and in the afternoon its patrols skirmished with an enemy force between Koram and the valley of the Surinam. As the enemy held the favourable ground the Independent Company withdrew for the night to the west bank of the Surinam. Dougherty’s other reconnaissance unit, “B” Company of the Papuan Battalion, moved during the day to a position 600 yards west of Dumpu. Dougherty recommended on the 5th that the Papuans should have a complete rest as the native soldiers were suffering from foot trouble. Officers and NCOs were also feeling the strain: the company had marched from Bulldog and fought through the Salamaua campaign and onward to Dumpu.

Dougherty hoped that the 2/27th would reach Kumbarum in the Finisterre foothills on the 5th. By 3.20 p.m. the battalion reached the timber on the bank of the Uria River and began to advance north along the difficult valley of the Uria. By 4.30 p.m., led by Major Johnson’s1 company on the left, and Captain C. A. W. Sims’ on the right, it was ready to attack the area which seemed from the map to be Kumbarum. In a heavy storm the infantrymen advanced steadily, and by 5.30 p.m. the Kumbarum area was overrun without opposition.

Bishop had advanced up the river valley fully deployed, with picquels on the surrounding foothills These were able to see that the enemy was occupying the key feature guarding the exits of the Faria and Uria Rivers from the mountains North-west of Kumbarum. Under cover of the continuing rain Lieutenant King2 and eight men scrambled up this feature (subsequently known as King’s Hill); the enemy panicked and fled thus abandoning an important tactical position and observation post.

Because of the heavy rain on the previous day Duchatel’s landing strip was not ready on the morning of the 6th. The activities of the 21st Brigade that day were therefore confined to patrolling, for the 2/27th Battalion could not move forward until more supplies had been flown in. Patrols from the 2/16th Battalion and the 2/14th, now led by Major Landale,3 went as far west as the Mosia River without seeing any enemy.

The artillery was now beginning to play its part. Headquarters of the 2/4th Field Regiment and the 8th Battery had moved to Nadzab on the 4th and the 54th Battery to Kaiapit. A light section under Lieutenant Pearson, who had led the paratroop gunners over Nadzab, was forward with the infantry at Dumpu, and in the advance to Kumbarum Bishop had used Pearson’s No. 511 wireless set, which proved to be light, easily handled and very efficient. “It is noticeable,” wrote the battalion’s diarist,

“the number of favourable comments made by our troops re this US paratroop wireless set model.” This praise was in striking contrast to the universal condemnation handed out by battalion diarists to the No. 208 set.

At 11.30 a.m. on the 6th Lieutenant King reported seeing 20 Japanese moving North-west along the Faria River Valley and Bishop asked for artillery support. Pearson directed 35 rounds on to a Japanese-occupied village near the position subsequently known as Guy’s Post4 in the Faria Valley. Later King’s men killed two Japanese moving down the Faria; their papers showed that they had been members of the 78th Regiment.

On the 6th the 25th Brigade had patrols out in all directions to the north of the Ramu Valley. Captain Milford’s5 patrol from the 2/25th into the Boparimpum area was out for three days and found many signs of the enemy once having occupied the area. Captain Cox’s6 patrol from the 2/33rd into the area north of Koram had similar experiences. Only Captain Rylands’ patrol from the 2/31st made any contact. In the hills north of Koram Rylands encountered what he believed was an enemy company in well-dug positions with numerous outposts on high ground from which snipers were active. While guides went back to the battalion to bring up reinforcements, Rylands worked slowly round to the northeast to capture an enemy outpost. A small patrol forced the enemy to keep their heads down while the company continued to the North-east. Next morning it was found that the enemy had disappeared during the night. This was probably one of the last Japanese outposts in the foothills east of the valley of the Surinam and was the position encountered on the previous day by the 2/6th Independent Company.

While the 7th Division was consolidating in the Dumpu area, Major Laidlaw’s 2/2nd Independent Company was patrolling its vast area from the Sepu to the Waimeriba crossings of the Ramu, and was proving that the enemy was either evacuating the valley or else thinking of doing so. Captain Nisbet’s platoon from bases forward of Bundi had several patrols across the swirling Ramu early in October.

One small patrol which crossed on the night of the 4th–5th met a small enemy patrol on the track between Saus and Usini and killed two Japanese. A second patrol crossed the Ramu at Yonapa on the 5th and went east along the main Ramu Valley track to Kesawai; it found indications that the Japanese had used this area extensively but had recently evacuated it. Another patrol found that the area between Saus and Urigina had recently been deserted by substantial enemy forces.

Captain Turton’s patrols meanwhile were searching for the enemy across the Ramu from the Maululi area and were on their way to join the 21st Brigade in the Dumpu area. On the night of the 4th–5th October

Turton led a section across the river and early next morning entered Kesawai, once an important Japanese position but now abandoned. While Turton examined the Kesawai base, and tunnels containing a large amount of supplies, ammunition and equipment, Lieutenant Fullarton led five men towards Dumpu. After marching all day along the hot valley, the men slept that night in the kunai and at first light continued their journey. One of the men later reported the junction with the 21st Brigade on the 6th as follows:

When we were nearing Dumpu we stopped to have a pawpaw and while we were eating we heard rifle fire. We could then see Aussie soldiers so waved our hats to show we were Australians. We were able to tell them the Ramu Valley was clear of Japs as far as Kesawai. We were looked after very well by the 7th Div and had eggs, butter, bread and jam, the first of that diet we had had for weeks, as our ration was bully beef and biscuits, dehydrated potatoes and margarine, and not a lot of any of it.

These linking patrols proved conclusively that the Japanese had left the actual valley of the Ramu and had retreated into the foothills. As far as Bena Force was concerned the days of the enemy raids across the Ramu were over, and fighting would henceforward be confined to the mountains north of the valley.

It was on 6th October that Generals Vasey and Wootten received a signal that the 2/2nd, 2/4th, 2/6th and 2/7th Independent Companies “will be re-designated forthwith” 2/2nd, 2/4th, 2/6th and 2/7th Australian Cavalry (Commando) Squadrons. Since the beginning of the year the term “commando” had been increasingly used to describe a member of an Independent Company. The term was an alien one for the Australian Army, and the tasks undertaken by the Independent Companies since the beginning of the war against the Japanese had little in common with the tasks carried out by the British commandos, although on some occasions there were some striking similarities with those of the original Boer commandos. In the short space of two years the Independent Companies had built up a proud tradition. The men regarded the term “Independent Company” as a much better description of what they did than the terms “cavalry” and “commando”, and they resented the change of title. There was little they could do about it, however, except to record their displeasure in their war diaries and to call themselves in their private correspondence cavalry squadrons, leaving out the term commandos. The report of the 2/6th probably summed up best what everyone felt.

It is submitted that the name “commando” as applied to these units is unfortunate. British “commandos” are the flower of the British Army; our personnel are, at the moment, merely a cross-section of the Australian Army. In common usage in Australia a “commando” has come to mean a blatant, dirty, unshaven, loud-mouthed fellow covered with knives and knuckle-dusters. The fact that the men in this unit bitterly resent the commando part of their unit name speaks highly for their esprit de corps. It is obvious, however, from the attitude of many of the

reinforcements received that the blatant glamour of the name is being used to attract personnel into volunteering for these units. Personnel acquired in this manner are always undesirable.7

By 7th October documents captured by the 2/27th at Kumbarum were translated. They were orders for delaying actions in the foothills round the valley of the Surinam and for the blocking of the Uria River Valley by the I/78th Battalion. This was further evidence that General Adachi intended to fight delaying or holding actions in the Finisterres while he tried to win a decisive battle at Finschhafen. From their bitter experiences on the Papuan coast Vasey and Dougherty knew just how difficult it was to root out an entrenched and determined enemy. Despite their superiority in numbers, fire power and air support, therefore, the Australian leaders expected no easy successes.

All identifications found by the 7th Division confirmed that the 78th Regiment was opposing the advance of the 21st Brigade. The III/78th Battalion, battered at Kaiapit, had withdrawn towards Yokopi near the head of the Bogadjim Road and Kankiryo Saddle. The I/78th Battalion had clashed with the 2/14th Battalion in the Wampun area and was now east of the Uria River ready to contest any Australian move there. The II/78th Battalion was either still in reserve as suggested by one prisoner or was carrying supplies forward to the I/78th Battalion. Except for the I/78th Battalion the 78th Regiment had therefore withdrawn early in October to the rugged area south of the Bogadjim roadhead.

The supply problem would also limit the Australian advance, for the 7th Division was supplied from the air and the Fifth Air Force had many commitments. Thinking about these limitations and the order given to him to move “in strength” to Key Point 3 when the “administrative situation” permitted, Dougherty found it difficult to decide what “in strength” meant. Key Point 3 was more than a day’s carry each way from the jeep-head and with his available native carriers he could maintain only one

battalion a day out from the jeephead. He therefore decided that his move “in strength” would be limited to sending one battalion a day’s carry away whence the battalion would send a company patrol to find Key Point 3 and harass the Japanese there. On the afternoon of the 6th Vasey drove through the fast-flowing Surinam in his jeep and told Dougherty his plan would suit admirably.

On the 7th, when Australian and American Army and Air Force commanders were deciding in Port Moresby to build airfield groups in the Nadzab and Gusap areas, patrols from the 7th Division were active all along the Ramu Valley. To achieve extra security on the western flank Dougherty sent Lieut-Colonel Sublet’s 2/16th Battalion to occupy a defensive position at Bebei. Here the battalion dug in, sent out patrols north and east, and provided large working parties to assist on the Dumpu strip.

On the 7th Captain Christopherson’s8 company of the 2/14th was sent to Kumbarum, where “B” Echelon of the 2/27th was established, and was instructed to patrol along a track running east towards the Surinam River. On this occasion the Australians were accompanied by a small American patrol with trained dogs.9 Christopherson’s task was also to provide escorts for the native carrying parties moving forward to the 2/27th Battalion.

The 2/27th Battalion was now cautiously investigating the upper reaches of the Uria and Faria River Valleys. As Dougherty thought that “administrative arrangements could be made sound enough” by 8th October for the 2/27th to move on that day, Colonel Bishop sent Captain Fawcett’s10 company to reconnoitre the route up the Faria River Valley so that the rest of the battalion could follow on the 8th. Twenty-six native carriers were allotted to the company but even so the Australians were each carrying up to 80 pounds. After bivouacking for the night on a shelf above the Uria River, Fawcett moved forward at 8 a.m. on the 7th following the Faria River with the high ground on his east side. Soon after 1 p.m. his rear section in the narrow area between the two rivers suddenly met a party of eight Japanese also on the move and killed three of them with no casualties themselves.

Fawcett pushed on during the afternoon past the saddle between the Uria and Faria River Valleys where he found many Japanese camp sites

7th–8th October

with the fires still warm in some of them. The Japanese had obviously just left, and had made no attempt to prevent the Australians from moving up the Faria towards a plateau on the east bank opposite a spot where a stream flowed into the Faria from the west. The company camped for the night on this plateau with a picquet opposite the spot known later as Guy’s Post. About 5 p.m. the Australians noticed some enemy positions just opposite on the east bank, on a small feature later named Buff’s Knoll.11 When they attacked the Japanese again withdrew.

That afternoon Dougherty was with the 2/27th Battalion. On King’s Hill Dougherty told Bishop that he should move into the mountains and occupy an area selected by him as a base about a day’s carry away. His route would be along the Faria River Valley to somewhere beyond Guy’s Post and then he would take the line of a suitable spur running North-east towards Key Point 3. From this base he would patrol to, and harass, the enemy at Key Point 3. Above all, Bishop was to regard the 2/27th as a battalion fighting patrol; he need not necessarily regard his base as a fixed place that he must hold. The 2/6th Commando Squadron would occupy King’s Hill when the 2/27th Battalion moved on, and the 2/14th Battalion would provide escorts for Bishop’s carriers.

Meanwhile, the Japanese commander south of the saddle at Kankiryo must have been perturbed at the ease with which Fawcett’s men had captured such an important feature as Buff’s Knoll. It was a dark rainy night but the position must be regained. An hour after midnight a strong Japanese attack, probably of platoon strength, was suddenly launched on the knoll. The first attack lasted for about half an hour before petering out, and in the dark the section on the knoll slipped down into the river bed, almost a precipice. Fawcett decided that it would be necessary to concentrate his company on Guy’s Post and this was done about dawn, after a slide down to the Faria and a climb on hands and knees up the other side.

On 7th October there had been a change in high command when, as mentioned, General Morshead’s II Corps relieved General Herring’s I Corps. Next day the corps role was re-defined by New Guinea Force. The first stated task given to the 7th Division was something of an anachronism; “as soon as practicable after seizure of [Kaiapit] area the [Dumpu] area will be secured”.12 The second task was a more topical one and outlined the role to which the 7th Division would actually be committed throughout.

After the capture of [Dumpu] operations north of [Dumpu] will be so conducted as to avoid a logistic commitment outside resources of I [II] Aust Corps. Operations against the village on coast (Bogadjim) 17 miles SSW of [Madang] will be restricted to patrol activities until other orders are given by [NGF].

Other parts of the 7th Division’s role included establishment and guarding of air installations, radar and air-warning stations in the Ramu Valley and on the Bena plateau, the construction of a road from Nadzab to Dumpu and the supply of the division from Lae and Nadzab rather than from Port Moresby and Dobodura. The “priority of establishment of airfield facilities” would be first – Lae and Nadzab; secondly – Finschhafen; thirdly – Kaiapit; fourthly – Dumpu.13

There was much improvement all along the Ramu Valley on the 8th. In the main battle area Bishop did not know what had happened to Fawcett’s company until communication was re-established. As a result of his discussion with Dougherty, however, Bishop and the 2/27th were already moving forward early on the morning of the 8th. At 2 p.m. they arrived at Guy’s Post but, surveying the rugged country before him, Bishop decided that he would need to picquet the hills on each side of the Faria before advancing farther and that it would take the afternoon for the picquets to get into position.

On the previous night a patrol under Lieutenant R. D. Johns, advancing up the Uria and laying signal wire, had come to a creek junction and camped for the night about 700 yards up the western creek. Just after dusk the telephone line was cut, and at 8.30 a.m. on the 8th one of the sections, moving to investigate this break, was fired on from high ground above the creek junction. Failing to find any sign of the enemy’s lines of communication up the creek Johns then moved North-west to some high ground whence he could see enemy positions and shelters at the top of the kunai ridge about half a mile up the eastern branch of the creek. Continuing on a semi-circular route, the patrol reached the Uria River again 500 yards below the creek junction about 4.40 p.m. just as firing began from there.

Meanwhile, in accordance with Dougherty’s instructions, the 2/6th Commando Squadron had moved to King’s Hill. At 2 p.m. on the 8th

Lieutenant Graham’s14 platoon from the commando squadron, believing Johns’ patrol to be in position ahead of them, advanced up the river from Kumbarum following Johns’ signal wire. At 4.40 p.m. a fierce burst of firing was heard but no information was available about the cause of it until, at 5.55, a trooper arrived almost exhausted and reported that Graham’s patrol had been ambushed. It was only later when the remnants of Graham’s patrol and Johns’ patrol arrived back that it was possible to report what had actually happened.

At 4.40 p.m. Graham’s leading scout, Trooper Mudford,15 saw a Japanese squatting on the track ahead near the creek junction cutting telephone lines. As Mudford fired at him the Japanese jumped for cover. Graham then sent Corporal Brammer16 and three men up the steep jungle bank on his right to cover the patrol and himself stood up directing the remainder to close up and move on. From positions some 70 yards away and about 40 feet above the patrol on a kunai spur, there was a sudden heavy burst of fire. In this first burst Graham was killed instantly and Mudford was wounded. Trooper Eddy,17 trying to cross the creek for a better shot at the enemy, was also killed, while the rest of the troops, sheltering under the creek bank, returned fire as best they could.

Brammer then scrambled back to rejoin the patrol and ordered the men to withdraw while he himself, assisted by two of his men, covered the withdrawal with a machine-gun. Then he went forward and found that Graham and Eddy were already dead. Although under heavy fire, he secured their papers and personal effects and withdrew his covering party. During its withdrawal Trooper Tyter18 suffered a compound fracture of the leg but, assisted by Trooper Little,19 Brammer carried Tyter for a little while and then floated him downstream for about 400 yards where his leg was dressed and splinted. Johns’ patrol had now arrived to see what all the firing was about.

It seemed fairly certain that the Japanese who had ambushed Graham’s patrol were those who had fired on Johns’ patrol earlier in the morning. It was also evident that this ambush party of about 20 Japanese were an outpost for a stronger body located on the spur seen by Johns’ patrol farther up the left arm of the creek, probably to protect a key point on the enemy’s lines of communication reported by reconnaissance aircraft as passing through this area. Despite the 2/27th’s spearhead being thrust into their main position north of Guy’s Post, the Japanese had by no means yet retreated wholly from the area east of the Uria River Valley.

The fact that they were still in this eastern area was confirmed by a company patrol led by Captain Power of the 2/33rd Battalion on the 8th and 9th October. Power set out at dawn on the 8th to patrol the area from Koram to the Surinam River, and north as far as possible. He bypassed Koram and went towards the Surinam passing through many old Japanese positions which had been deserted within the last few weeks. In the afternoon the patrol came across three bridges which had been blown up by the retreating enemy, and a small patrol to the North-east found an extensive well-dug position where there had recently been about 200 Japanese. Next morning Power pushed on along a well-graded, three foot wide track running along the west bank of the Surinam up into the foothills. At midday his men captured a prisoner and saw immediately ahead a well-dug position on a razor-edged spur occupied by about a company. As this position would have been too costly to attack Power withdrew for the night. The enemy was occupying a dominating feature shown on the map as being 4,100 feet high, about one mile South-east of where Boganon was thought to be and about four miles east of Kum-barum.

On the 9th Bishop began to move his battalion forward to try to get astride the main Japanese route from the east towards Kankiryo Saddle. Fawcett’s company moved off from Guy’s Post at 8 a.m., the remainder of the battalion following about an hour later. At 8.30 the leading platoon commander, Lieutenant Trenerry,20 reported that three Japanese were coming towards him along the track. Two of these were killed and one wounded and, about 100 yards forward, the patrol saw about 20 Japanese scattering in all directions. Trenerry waited in ambush for about an hour and was then recalled. This area, about a mile along the river north from Guy’s Post, was subsequently known as Beveridge’s Post, after Private Beveridge21 who was wounded there.

When Trenerry first struck the enemy Fawcett sent a section to the high ground to the right to get flanking fire on the enemy. Bishop came forward and told Fawcett to send a platoon out to this section with instructions to get as high as possible and Lieutenant Macdonald’s22 platoon climbed up the ridge on the right subsequently known as Trevor’s Ridge.23

The Japanese were on the high ground ahead of the battalion up the Faria and Bishop decided that the valley was too much of a defile, where a platoon of Japanese could hold up the advance of the battalion. He therefore decided to take his battalion round on the high ground to the east side of the river. At the same time Bishop consulted Lieutenant Snook (as mentioned earlier, he was an engineer with experience in New Guinea before the war), now attached to the battalion. Snook knew the

area well and he had with him a houseboy who also knew it and who had been forced into service by the Japanese but had run away. It seemed clear to Bishop that his battalion was very near the Japanese lines of communication. Before the 2/27th actually started to move to the high ground on the right Bishop beckoned to some men, on a point to which he had sent a picquet, to come down and follow the battalion. The men did not come and later proved to be a Japanese force which had beaten the Australian picquet to the point by half an hour. Behind the advance, platoons were left at Guy’s Post and at Beveridge’s Post.

The 2/27th was ready to move off soon after 10.30 a.m. east from the rugged slopes of the Faria River Valley. By midday the men were clambering up towards the crest of the ridge where Macdonald’s platoon and another were now in position. Captain Toms24 had now taken over the lead from Fawcett’s company. On the other side of the ridge could be seen a well-defined track, obviously much used by the enemy. Lieutenant Snook and Corporal Lundie,25 manning an observation post watching this Japanese track, heard a rustling on both sides of the hillside below them. As one section of Australians climbed up one side of the ridge a soldier was heard panting as he climbed up on the opposite side. The soldier turned out to be a Japanese who panicked when he saw the Australians and jumped over a steep cliff about 100 feet high. Toms came forward to the observation post and saw 14 Japanese moving along the track in the gully below. The track seemed to run from the Faria River North-east across a saddle about 400 yards away and separating Trevor’s Ridge from a knoll to the South-east.

Bishop, who was with the leading company, now sent Macdonald’s platoon forward to move on to the saddle and find the track, at the same time setting an ambush. As they approached the saddle at about 3 p.m. through pit-pit cane the Australians “heard a lot of noise such as tins rattling and a lot of talking going on in the centre of the track”. Fifteen Japanese were already on the saddle but they were quite unaware of the Australians’ approach and were preparing their meal. Without pause Macdonald attacked and killed eight of the Japanese while the remainder escaped; the Japanese each carried seven days’ rations. It was now about 3.30 p.m. but as the Australians began to withdraw their wounded a further party of 14 Japanese were seen approaching up the track. One section held the saddle while two sections, led by Corporal Sullivan,26 went to intercept the Japanese force. Although wounded Sullivan led his small force with such determination that a possible Japanese counterattack was beaten off. For 5 men wounded in these two actions Macdonald’s platoon killed 11 Japanese and captured 20 rifles, 3 machine-guns, 3 mortars, as well as maps and papers. Bishop believed that his battalion was now right in the centre of Japanese territory. He was astride

a well-used track, and he had gained a good base position. The battalion therefore dug in along Trevor’s Ridge leading up to the saddle, on the saddle itself and on the small knoll later known as Johns’ Knoll, on the other side of the track.

Just after dawn on the 10th a small enemy force, after yelling for about four minutes, attacked straight along the track towards the company on Trevor’s Ridge. The attack was beaten back. Describing this fight the battalion’s diarist wrote:

Tojo startled the early morning air with his usual heathen chorus, known to so many as a prelude to an attack; however, 13 Platoon showed him the error of his ways by killing two and wounding one of the six noisy intruders.

In the morning the Australians fired at some enemy seen climbing a steep ridge on the west side of the river about 600 yards from Beveridge’s Post. One of the Japanese was seen to throw up his arms and disappear over the eastern side of what later was known as Shaggy Ridge.

During the afternoon of the 10th Lieutenant Macpherson’s27 platoon from Beveridge’s Post patrolled north along the Faria seeking the body of a man killed the previous day about 300 yards north. The covering party moved off within 20 minutes of the burial party, but was ambushed when examining Japanese dead. One man was killed and another wounded. The casualties would have been heavier but for Private Simmons,28 a member of the ambushed party, who worked his way under fire up the steep bank of the river and found a position across a ravine facing the enemy. He shot two Japanese and quietened the rest, thus enabling the remainder of his party to escape. Simmons then returned to Beveridge’s Post and guided a small band to his firing position, whence several more Japanese were killed.

In the afternoon also two Japanese guns opened fire on the battalion from the Faria River area at very close range. The first shell passed close to the top of Trevor’s Ridge, causing the native carriers to disperse, and exploded some thousands of yards farther on. By 2 p.m. Bombardier Leggo,29 acting as FOO, noticed the gun flash and brought down counter-battery fire from the force’s one short 25-pounder at a range of about 8,000 yards. He was successful in silencing the mountain guns for a while. When the Japanese guns fired again later in the afternoon at almost point-blank range, the shells began to land in the battalion’s area and caused eight casualties, but Leggo again silenced them.

On the morning of the 10th Brigadier Dougherty sent the 2/14th Battalion from Dumpu to the Kumbarum-King’s Hill area to relieve the 2/6th Commando Squadron. The 2/14th was already providing escorts for the 2/27th’s carrier line, and by moving the whole battalion to the Kumbarum

area Dougherty believed that more effective support could be given to the 2/27th in case of need.

The 2/16th was on the flat ground to the west of Bebei where malaria was taking its toll much to the concern of the commanders. The Ramu Valley was very malarious for hosts of anopheles mosquitoes bred in the swampy low-lying country. Although occupying a defensive position the West Australians were patrolling vigorously into the hills on the western flank of the 2/27th Battalion’s advance. A patrol led by Warrant-Officer Young30 had established a valuable observation post two days previously. From this position, known as Young’s OP, a report arrived on the 9th that an unidentified patrol had been seen on a feature about 1,200 yards north of the position. Lieutenant McCullough’s platoon immediately set out from Bebei to investigate. Looking ahead from Young’s OP over the rugged and precipitous country of the Finisterres McCullough estimated that it would take his patrol at least four days to reach the objective. Nevertheless, they set out, for the country was seldom as bad as it looked, and there was usually a way, however rough. The patrol camped for the night near a large Japanese defensive position vacated about four days before. Progress was slow on the 10th for the terrain was so steep that much of the climbing had to be done on hands and knees. Mc-Cullough’s men were seen by the enemy who fired on them from a position subsequently known as Don’s Post (after Lieutenant Don McRae31). McCullough wished to attack the position but he was instructed to withdraw. The patrol occupied Bert’s Post (after Lieutenant Bert Sutton32) about 500 yards North-west of Young’s OP This patrol was typical of several others carried out by the 2/16th Battalion in the mountains north of Bebei.

Meanwhile to the east the 25th Brigade was entering the fight. Brigadier Eather instructed Colonel Cotton of the 2/33rd Battalion to clean out the Japanese who opposed Captain Power’s company patrol. The 2/33rd left the Ramu Valley soon after dawn on the 10th and followed the track of Power’s company into the hills. By 1.30 p.m. the battalion reached the leading company which was below the 4100 Feature overlooking the track. Cotton immediately placed his battalion in position for the attack and at 4 p.m. Major MacDougal’s33 company led the ascent up the south end of the high feature, while Captain Mitchell’s34 company climbed the high ground on the left flank to give protection and covering fire for MacDougal’s advance.’ The pace was slow and the amount of ground covered in the first hour was small because of the precipitous nature

of the feature. For the next three-quarters of an hour, from 5 p.m., Kitty-hawks strafed the top of the Japanese-held ridge. A Boomerang flew off to drop a message on Eather’s headquarters – that the Japanese were in foxholes and trenches immediately overlooking the 2/33rd. During the air attack the enemy replied to the planes with machine-gun and rifle fire and also fired on Power’s company. The Japanese apparently did not see the approach of MacDougal’s company, perhaps because the planes were keeping them busy.

At 7 p.m., three hours after the start, MacDougal was still pushing steadily towards the top. “Country terrific – very hard going,” reported the diarist. The slope towards the top of the feature was almost sheer but Eather and Cotton were determined that, although a night attack was unusual in jungle fighting, the 4100 Feature must be captured before the morning. Under cover of darkness MacDougal’s men reached the top of the ridge at 9.30 p.m. and moved straight towards the highest point to try their luck against whatever opposition was there. The Japanese defenders were surprised, probably because they did not expect the Australians to attack by night. As the Australians loomed out of the darkness on the flank the Japanese first panicked and fled, then tried to stop and fight, and were finally driven from the feature.

On the 10th General Vasey’s three commando squadrons were also patrolling extensively or moving to new areas. While the 2/6th moved back to Dumpu from Kumbarum, the 2/7th was on its way from the Kaigulin-Bumbum area, where it had been resting, towards the Mosia River on the left flank of the 21st Brigade. Two days previously Vasey had warned Captain Lomas of the 2/7th that his squadron would eventually take over the Kesawai area. The 2/2nd would then be able to concentrate in the Faita area to the west, at the same time watching the air and radar installations on the Bena-Garoka plateau.

In these early days of October there were several savage fights for supremacy in which the Australians strove to secure dominating positions in the foothills of the Finisterres. The 11th was no exception. Early in the morning Lieutenant Robilliard’s35 platoon of the 2/27th patrolled from Trevor’s Ridge towards the Faria River to seek out the enemy protecting the guns north of Beveridge’s Post, and also to cover a renewed attempt to bring in the body of the man killed there on the 10th. Under cover of three mortar bombs on the enemy who were still strongly entrenched the dead man was carried in, but, because of the rugged nature of the country and the limited time, Robilliard was unable to reach the spot where the guns were thought to be.

At 1.15 p.m. the Japanese guns opened fire again, this time from a more distant range. Their second shell unfortunately put out of action Leggo’s wireless set. By 2.30 p.m. a short 25-pounder had been sent as far north as possible and was ready to fire. Leggo remained in his observation post and shouted his orders about 30 yards to the battalion’s

Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Reddin,36 who told them to Colonel Bishop, who sent them on through his No. 11 wireless set – hit but not put out of action by the shelling – to Dougherty’s headquarters whence they were passed by telephone to the guns. Throughout the afternoon Leggo stayed in the forward area observing the enemy gun flashes, and although the enemy guns stopped firing at 4 p.m., it could hardly have been the Australian short 25-pounders which forced them to do so, for their range was about 2,000 yards short.

As mentioned, Bishop’s task was to establish a forward base and patrol to find Key Point 3. The base was now established and Captain Toms’ company was sent out to complete the allotted task. At 3 p.m. on the 11th Toms moved off towards the high ground on the right flank. He also had to seek a suitable position in which to locate a counter-attacking force based outside the battalion’s position; and to discover whether it would be possible to move round this high ground to the Kankiryo Saddle – the divide between the South-flowing Faria and the North-flowing Mindjim. After a five-hour climb, in which two miles were covered against slight opposition, Bishop instructed Toms not to move farther except on small reconnaissance patrols.

At this stage it was becoming obvious that it would be difficult to maintain and supply a sizeable Australian force in the mountains where the Japanese had a far easier supply route along the Bogadjim Road. The supply position was worrying Bishop for he had received little since leaving Kumbarum. Late in the afternoon of the 11th he received a report from Lieutenant Clampett,37 whose platoons were at Johns’ Knoll, Beveridge’s Post and Guy’s Post, that the stretcher party which had left Guy’s Post for Kumbarum early in the morning had returned after being ambushed north of King’s Hill. Also there was no news from Lieutenant Crocker’s38 platoon which was escorting forward a supply train of about 300 natives.

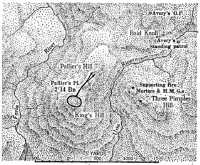

The 2/27th had actually been in peril of being cut off on the 11th. Lieutenant Pallier’s39 platoon of the 2/14th Battalion had occupied King’s Hill the previous day. Soon after first light on the 11th Lieutenant Avery’s standing patrol in the hills to the North-east reported seeing figures digging in on a high feature west across the Uria from the Three Pimples feature and north from King’s Hill. When Crocker’s escort and carrying party for the 2/27th was fired on by these Japanese near the Faria, the natives dumped the supplies and “went bush”. It was thus established that about 30 Japanese had moved there during the night and were now digging in, not only on the high feature subsequently known as Pallier’s Hill, but also astride the ridge over which the 2/27th’s line of communication

11th October

ran to the north. Pallier’s Hill had been occupied by the 2/27th but was not occupied by the 2/14th when it relieved the 2/27th.

Soon after the startling discovery of the enemy’s determination to block the supply route to the 2/27th, the 2/14th’s adjutant, Captain Bisset, climbed the rugged Three Pimples feature on the right, found a position between 700 and 1,200 yards from the enemy on Pallier’s Hill, and by wireless sent back accurate information about their positions.

Learning of the Japanese threat, Dougherty sent forward his brigade major, Owens, carrying orders for prompt action by the 2/14th to clear the 2/27th’s lines of communication. Major Landale of the 2/14th realised that there was only one way to attack Pallier’s Hill – from King’s Hill. He sent Captain O’Day with two platoons to take command on King’s Hill, and decided not to attack until mortars and machine-guns could be dragged up into the very difficult country near the Three Pimples on the right whence they could give supporting fire. This was done in the late morning. Dougherty was chafing at the delay and sent Major A. J. Lee40 across from the 2/16th Battalion to take command of the 2/14th.

On the Three Pimples feature a nine-man mortar detachment was already in position overlooking the enemy on Pallier’s Hill when Bisset arrived back, and suggested that the only possible course was for Pallier’s platoon to attack from King’s Hill supported by fire from the Three Pimples – as Landale had planned. During the late morning a section with Vickers guns, a mortar control party and one infantry platoon climbed the Three Pimples so that covering fire could be brought to bear at right angles to any advance from King’s Hill. While two other platoons were climbing King’s Hill to relieve Pal-lier’s platoon for the attack, Vickers machine-gun fire from the low-lying Kumba-rum area and artillery fire from the Ramu Valley harassed the enemy on Pallier’s Hill.

All was in readiness for the attack to begin at 4.50 p.m. “From the point of view of supporting fire it was an ideal text-book attack”41 because the medium machine-guns from Three Pimples were firing at right angles

to the line of advance of the assaulting troops and were able to fire within a few yards of them. The mortars and artillery also had excellent observation. The situation confronting the attacking platoon, however, was not encouraging. King’s Hill and Pallier’s Hill were about 1,000 yards apart and connected by a knife-edged ridge with a small pimple about half way between the two hills. Sloping down slightly to this pimple the ridge then sloped up to the summit of Pallier’s Hill. On the right side the ridge was very steep and fell almost sheer to a swift stream hundreds of feet below. Apart from kunai grass which had been burnt in patches along the ridge, the only vegetation was a small patch of jungle near the pimple. It did indeed look a difficult, if not impossible, task and the men prepared for battle realising that there must be heavy casualties.

Pallier’s plan was to advance with one section on the right and one on the left and the third section in reserve to give covering fire. The ridge was so narrow and the sides so steep, however, that it was difficult for the advance to be other than in single file, with some scrambling along the sides. At 4.50 p.m. the platoon left the protection of King’s Hill and formed up as the Australian artillery, mortars and machine-guns stepped up their bombardment; this was so effective that the platoon reached the pimple without opposition. Here one man was stationed with a Bren gun and two with a 2-inch mortar to give close supporting fire.

To the incredulity of the platoon there was still no opposition as they moved rapidly up towards Pallier’s Hill. When they were near the summit the artillery stopped, leaving mortars and machine-guns as the only support. The ridge now became even steeper and one false step could have meant sliding down the steep slope to hurtle into the creek below. Twenty yards from the Japanese on the summit the last of the covering fire ceased and then the expected opposition came with a vengeance. The Japanese, about a company of them, fired everything they had. They killed two of the three men left at the pimple, but not before the small band had given valuable supporting fire in the vital stages. The critical moment came when the Japanese raised their heads from their weapon-pits and rolled grenades down on the Australians some 20 feet below – Corporal Silver’s42 section on the right and Corporal Whitechurch’s43 on the left. Some of the grenades landed above the men, rolled down among them and were speeded on in many cases by a hearty push or kick. Most of them rolled too far down and did not do much damage. Hurling their own grenades up into the Japanese positions, the men began to scramble up the last few yards. Fortunately the artillery fire had loosened the soil enabling them to gain a foothold.

Most of the enemy fire was concentrated on the right-hand section where the platoon sergeant, L. A. Bear, was with Corporal Silver. Several casualties were suffered here as Bear and Silver led their men in a spirited

and almost perpendicular charge straight up into the enemy position. Reaching the top Bear fired his rifle among the Japanese defenders and, as he and Silver scrambled over the ledge, they saw a Japanese in a foxhole at the same instant as he saw them coming above the ledge. The Japanese tried to fire at each of the Australians in turn and they at him point-blank but nothing happened for all three had emptied their magazines. “Bear heaved himself straight up over the ledge, lunging with the bayonet in the same movement. He hurled the Japanese like a sheaf-tosser, then he sprang clear to meet the next foe.”44 As the rest of the section followed Bear and Silver up, the left-hand section, led by Whitechurch firing his Owen gun from the hip, came charging in. Whitechurch reported later:

We could see them now and opened fire on their heads as they bobbed up above their foxholes. Their fire began to slacken off. One of our chaps gave a shrill bloodcurdling yell that startled even us, and was partly responsible for some of the Japs running headlong down the hill in panic. Unable to stop at the edge of the cliff, they plunged to their doom hundreds of feet below.45

The covering fire of the third section had helped the others during their advance and when they were scrambling up to the crest.

The valour of this platoon had carried all before it and a Japanese company, entrenched in a seemingly impregnable position, had been routed. Despite the heavy bombardment from the Australian supporting arms, the Japanese should have been able to hold their natural fortress. For the loss of 3 men killed and 5 wounded, including Pallier and Bear, the platoon had killed about 30 Japanese and captured the vital ground astride the lines of communication to the 2/27th. The capture of Pallier’s Hill was a great relief to Dougherty who was watching the fight. Had it been held much longer by the Japanese, the 2/27th, with little ammunition and few rations, would have found it almost impossible to hold their positions in the fight looming ahead.

The Japanese were really nettled on 11th October and were fighting vigorously for their mountain trails. East of the valleys of the Faria and Uria Rivers the 2/33rd Battalion was patrolling forward from the 4100 Feature captured the previous night. While MacDougal’s company guarded the feature, the battalion set out with Power’s company leading to join the forward standing patrol established on the previous day by Lieutenant Haigh.46 At 11.30 a.m. Power’s company was ambushed. The enemy position was on a narrow kunai-clad spur about a mile long. By 1.20 p.m. the battalion’s mortars were on high ground and opened fire on the enemy seen moving along the forward ridge. The Japanese replied with a mountain gun which did no damage, but Power’s company had now lost several men and could show no other results. Colonel Cotton, who considered he was on the outskirts of Boganon, estimated that it would take about a day to encircle the high feature by the right flank. Towards dusk he

was ordered by Brigadier Eather to continue seeking a line of attack. By 9 p.m. the battalion, again during darkness, managed to take up more favourable positions so that its mortars and machine-guns could worry the enemy.

That day General Morshead flew from Lae to Dumpu for a conference with Vasey. They visited Dougherty, whom Vasey told that the 25th Brigade would look after any enemy east of the Uria River and the 21st Brigade need concern itself only with operations west of it. From the conversations of the three leaders it was again clear that, because of “administrative limitations”, there would be no question of a farther advance into the mountains for the time being.

During the night of the 11th–12th the Japanese were again on the move. Two hours after midnight they tried what they had already tried unsuccessfully to do at Sanananda and Salamaua – raid the guns. Six Japanese armed with 15 pounds of gun cotton, 50 feet of detonating fuse, small arms and grenades, crawled into the gun area 1,000 yards south of Kumbarum where two guns were protected by the gunners and a section from the 2/14th Battalion. Shots and grenades were exchanged between the Australians and Japanese before the raiding party dropped their bundles and fled.

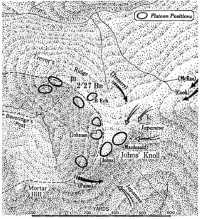

At dawn on 12th October two incomplete companies of the 2/27th were stationed in the Trevor’s Ridge area, with battalion headquarters and portions of Headquarters Company. Because of damage caused by the Japanese mountain gun, Bishop considered moving his battalion to a wooded ridge which adjoined the saddle on Trevor’s Ridge. At 10.30 a.m. he sent a small patrol which immediately encountered about 18 Japanese moving astride the track from this ridge. After firing at the Japanese the patrol returned and at 10.45 a.m. the enemy attacked in strength. The attack was supported by five Woodpeckers; two mountain guns, mortars and light machine-guns also joined in the attack. The enemy plastered the ridge and the knoll with grenades from grenade-throwers and under very heavy supporting fire they attacked Johns’ position with bayonets. They gained the lower easterly part of the ridge proper where the defenders were all wounded, but this lower slope could be brought under heavy fire from a section on the crest above, and was untenable by the enemy.

Immediately after the first attack Major Johnson sent across a section from Trevor’s Ridge to reinforce Johns, and Bishop sent forward also Lieutenant Macdonald’s platoon. About 11 a.m. Macdonald’s men reached the knoll and raced through heavy enemy fire to fill the pits vacated by Johns’ casualties. Macdonald arrived just after the second attack had been beaten back. “This arrival,” reported Johns, “improved the situation considerably and claims to ownership of the ridge swung in our favour.”

By this time Bishop was becoming very worried at the depletion of his ammunition, for there was no sign of the expected supply train. He had in this forward area only two Vickers guns and one 3-inch mortar. The Vickers were used to counter the fire from an enemy machine-gun on the plateau across the Faria River, which was really firing into the backs

Defence of Trevor’s Ridge and Johns’ Knoll by 2/27th Battalion, 12th October

of the defenders, and the mortar, for which there were only 18 bombs, was placed in support of Johns’ Knoll. When the enemy had reached within 20 yards of the Australian positions in the first assault, Sergeant Eddy47 went forward and directed 12 mortar bombs at the enemy 20 yards in front of the Australians. The bombs caused havoc among the enemy and Bishop kept 6 as a last reserve. The two enemy mountain guns seemed to have been moved closer than on the previous day and Bombardier Leggo, late in the afternoon, managed to bring his own gunfire down near the enemy guns.

There were two more Japanese attacks on Johns’ Knoll but both were thrown back with heavy casualties. By 3 p.m. four separate attacks had been defeated. Although there were many enemy dead before Johns’ Knoll the position was dangerous, and the dogged infantrymen realised that they would have to pull out if no ammunition arrived. Teams were collecting ammunition from headquarters and even from the platoon on Trevor’s Ridge and racing it forward to the two beleaguered platoons. On the knoll itself were many examples of gallantry. Although wounded Private Fisher48 remained on duty and set a good example by making many trips under heavy fire to supply his section with such ammunition as he could obtain. Private Barnes49 raced out under heavy fire to retrieve a Bren gun and ammunition from a dead gunner.

When, at 3 p.m., Bishop informed Dougherty by wireless that the ammunition situation was critical, Dougherty replied that if the ammunition actually ran out Bishop should leave Toms’ company to fight its way back by a circuitous route to Guy’s Post where the battalion would concentrate. Bishop did not like leaving the company “out in the blue” and hoped that Toms would attack downhill in the enemy’s rear. An hour earlier he had ordered Johnson to launch a counter-attack to relieve the pressure on Johns’ Knoll. Johnson promptly sent out two platoons, one

to attack the enemy’s right flank and one to attack his left. Lieutenant Paine’s50 platoon from a position astride the track was sent round the right to attack the Japanese left flank and Lieutenant Trenerry’s from the company on Trevor’s Ridge round the left. After giving his orders quickly and instructing his men to stuff a meal in their pockets, Paine set out about 1.45 p.m. and the platoon fought its way to a knoll on the right of the track. Thence Paine sent two sections round the right of the knoll and one round the left. Working their way up to about 20 yards from the top of the razor-back ridge, the men fired at a number of targets as they came into view but, in the words of one of them, “things got a bit sticky so we withdrew down the hill a little then made our way back to the end of the razor-back”. As he thought that his orders were to stay out for only a short time, Paine withdrew to his own original positions, keeping close to the side of the hill. He arrived back at about 3.30 p.m. only to be sent out again with orders to stay out all night if necessary as the situation was so serious.

On the left, Trenerry, with two sections, set out soon after 2 p.m. Moving cautiously the platoon was ready by 4 p.m. to take advantage of heavy rain and raced for the track about 150 yards to the rear of the Japanese forward troops. The men could see six or seven groups of Japanese near by who were attacking Johns’ Knoll. Suddenly Trenerry’s men threw sixteen hand grenades into these groups. Many Japanese were killed and, in confusion and terror, the others dispersed very quickly running mainly into the Australians’ fire. With five men Trenerry cleared the track to Johns’ Knoll while five men cleared the track in the opposite direction and the remainder took up covering positions just below the crest of the ridge. “Both groups clearing the track ran backwards and forwards shooting at opportune targets,” reported Trenerry. Private Blacker,51 firing his Bren from the hip, killed five Japanese who tried to withdraw along the track. Private May52 killed four Japanese before being hit himself and most of the other men killed at least two Japanese each. By the time Trenerry’s men joined Johns they knew that they had killed at least 24 Japanese with small arms fire apart from those originally killed in the grenade bombardment. This successful counter-attacking patrol ran out of Japanese just before it ran out of ammunition.

It was raining heavily at 3.50 p.m. as Paine’s weary men – literally taking a dim view of things – retraced their steps up the ridge. After killing a sniper, the platoon worked its way up the razor-back to the enemy positions attacked earlier. As there was still heavy firing along the razor-back they moved through the kunai grass just below the top, and attacked straight up the hill towards the Japanese positions, but were greeted with so much fire and so many grenades rolled down on them

that they withdrew down the hill for a little while behind some cover, and waited. Here nearly every man had successful shots at Japanese moving along the razor-back. Just as dusk was gathering, Privates Green53 and Searle,54 with the wounded Corporal Box55 who “said he would carry on as there weren’t many in his section”, moved back to the track along the razor-back and reconnoitred it towards Johns’ Knoll.

The two counter-attacking platoons had relieved much of the pressure on Johns’ Knoll, and Bishop now thought that if the battalion could only hold out until nightfall he would be able to find his missing company and defeat the enemy, provided the ammunition train reached the battalion during the night. Dougherty told Bishop that Lieutenant Crocker’s platoon should rejoin him during the night with the ammunition, and that a company from the 2/14th would move to Guy’s Post to be at Bishop’s immediate call: Christopherson’s company arrived at Guy’s Post one hour before midnight.

On the knoll Johns’ and Macdonald’s depleted platoons could hear firing all around them during the late afternoon both from the enemy and from the counter-attacking platoons. Soon after 5.30 p.m. more firing was heard from the high ground east of the ridge; all hoped that this was from the missing company, and so indeed it turned out to be.

Toms first had an inkling that something was wrong when his telephone line was cut; then in the mid-morning firing started below him. He immediately sent Lieutenant McRae’s platoon to find and repair the break in the telephone line but when McRae reached the foot of the hill on which the company was camped, he discovered that the ridge joining the feature with battalion headquarters was occupied by Japanese. McRae telephoned this news to Toms who sent out the Pioneer platoon under Lieutenant Cook56 to clear the Japanese from the ridge. A few days later Cook wrote:

I met Mac and he gave me all he knew so I pushed forward to contact the enemy. I handed 5 Platoon over to Sergeant Underwood,57 commonly known as “Underpants”. The laps were expecting us for they opened up with their Woodpecker and did they whistle but the boys kept pushing on. I sent Sergeant Yandell58 round on the right flank while a section from B Company and Corporal Fitzgerald’s59 went around on the left; well, Lum’s [Yandell’s] section on the right did a wonderful job and made it possible to wipe out the Woodpecker. The boys must have killed 20 or more Japs on the first knoll and by the way they bawled you would think they were killing a hundred of them. We continued on along the ridge for another 100 yards when 3 LMGs opened up on us and inflicted our first casualties, 2 killed, 4 wounded. One of the killed was Dean60 who had done a fine job killing several

Japs while firing his Bren from the hip as he advanced. At about this time I found [a young soldier] of B Company alongside me so asked him what would win the Goodwood whereupon he told me not to be so bloody silly, it was no time to talk about races. Well, we had to shift these gunners so Lum kept moving his section forward on the right flank and two of the gunners got out while the other covered them. Then Lum volunteered to go over the top after the remaining one himself so I slipped up behind him to give him covering fire, but as Lum went over the top the Japs cleared off into the kunai.

The Japanese had almost had enough. At 5.25 p.m. Crocker’s supply train had arrived at Guy’s Post and went forward full speed ahead. About 6 p.m. Paine, on the razor-back to the right, sang out to Johns to ask if he could move up to his position. When Johns gave a cheery OK, Paine moved up and found that the Japanese had disappeared from the area between his platoon and the men on the knoll. Paine reported that the area south and South-west of the knoll was clear of live Japanese and Trenerry, who moved back to his company area about this time, through Johns’ men, reported that the saddle east of the knoll was also clear. The two patrols – Paine’s and Trenerry’s – actually met along the razorback on their way back to their respective companies. All along the ridge were many small holes dug by the Japanese.

By nightfall the enemy attack had ceased and the battalion had not yielded one inch of ground. Just before dusk Bishop sent two men to try and find a way round the Japanese lines to Toms and tell him to remain on the ridge for the night and counter-attack in the morning. Later, under cover of darkness, Lieutenant Cook sent three volunteers – Sergeant Yandell, Sergeant O’Connor61 and Private Napier62 – to try to reach the battalion with the news that the company had two men killed and four stretcher cases. At 7.40 p.m. they reported in to Johns’ Knoll having found the area in between clear of all except dead Japanese. The three men went on to battalion headquarters and were also given the message for Toms. A medical orderly accompanied them carrying morphia for the wounded. McRae mended the wire and passed on the message from battalion headquarters to Toms who immediately began to move straight down to Cook’s platoon, arriving there at 5.30 a.m. on the 13th.

Two hours after midnight on the- 12th–13th the native supply train arrived with the supplies, including the much-needed ammunition. The wounded were carried out by the returning native train, and the tired but triumphant unit waited confidently through a long wet night.

By its decision to sit tight and hope for the best the 2/27th Battalion had won a notable success. The battalion had lost 7 men killed and 28 wounded and had killed about 200 Japanese. The enemy’s attack on the knoll coupled with his bold occupation of Pallier’s Hill and vigorous defence against the 2/33rd Battalion farther east seemed to be all part of a move to push the Australians from the vantage points they had won.

The counter-attack had failed, not because the Japanese were in the minority nor because they were less adequately armed and supplied, but because they had no counter for the spirit of Pallier’s attack and Bishop’s defence. Just before the supply train arrived the 2/27th had enough ammunition for about another quarter-of-an-hour’s fighting, but when the ammunition had been distributed rapidly, in darkness, Bishop felt secure and informed Dougherty that he would not withdraw.

Dougherty was now confident but, as an extra measure of security, ordered Christopherson’s company of the 2/14th to move from Guy’s Post up the spur leading to the high ground south of the 2/27th. There is little doubt that the 2/27th Battalion was now astride the main Japanese carrier route although, farther north, there was another well-used track which was bench-cut around the hills and had a good grade. Originally it was probably intended to continue the motor road from Bogadjim along this route. As far as they could ascertain the 2/27th were at Key Point 3 and east of them were the remnants of two battalions of the 78th Japanese Regiment.

Prisoners and documents confirmed that the assault on the 2/27th Battalion had been made by the II and III Battalions of the 78th Regiment which had moved down from the north for this purpose. Because of sickness and casualties the battalions were below strength; prisoners estimated that the 78th Regiment was less than half strength. Defending the hills north of the Surinam against the 25th Brigade was the I/78th Battalion. Pressure by the 25th Brigade and the Japanese decision to withdraw farther was probably responsible for the fight at Pallier’s Hill where a company of the I/78th Battalion withdrawing from the east found itself in the midst of Australian positions.

At first light on the 13th Lieutenant Cook of the 2/27th led a fighting patrol through to battalion headquarters from the east to clear the track of any remaining Japanese, but all were gone. At 6.45 a.m. a Woodpecker opened up from a new position just above the plateau across the Faria and Cook was sent to reinforce the company now facing that area. At 8 a.m. Johnson discovered that six Japanese were dug in about 200 yards to the South-east of his company – probably covering a burial party. Bishop decided to leave them there for the time being and save his battalion the task of burying the many enemy dead.

The Japanese artillery continued to fire from the plateau across the river and was occasionally aided by long distance fire from Woodpeckers. “The lads treat this Japanese action with great respect and are feeling the strain after yesterday’s hard fighting,” commented the battalion’s diarist. One difficulty was that the native carriers disappeared each time the enemy guns opened up, giving the quartermaster, Captain J. D. Lee, a hard job rounding them up again. The spirits of the natives rose, however, when, at 2.20 p.m., Airacobras were led in by Boomerangs to attack known Japanese positions in the Faria River Valley.

On the morning of the 13th Vasey visited Dougherty and told him that he could move the 2/16th Battalion from the river flats; the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion would be brought in to take its place. Dougherty decided

to relieve the 2/27th Battalion with the 2/16th and to move his own headquarters to Kumbarum. The 2/6th Commando Squadron reverted to divisional command and was ordered by Vasey to maintain two troops in the Bebei area and probe the surrounding country.

By 5 p.m. on the 13th Christopherson (of the 2/14th) was on top of a wooded knoll and could see Johns’ Knoll about 100 yards away on a bearing of 50 degrees. Bishop instructed him to continue his encircling move along that bearing and wipe out the Japanese pocket reported earlier in the day before joining the 2/27th. At 5.45 p.m. the company reached the 2/27th but had missed the Japanese pocket. Half an hour later Lieutenant Paine was sent out with two sections, found the Japanese position, and grenaded it. Unfortunately a grenade rebounded from a tree and killed Paine, an original member of the battalion. The patrol withdrew, but the Japanese had also had enough, and next morning had disappeared.

Meanwhile the 2/33rd Battalion, trying to move north from the 4100 Feature, had a frustrating and costly day. In the morning Boomerang aircraft reported that whenever the planes were overhead the Japanese left their foxholes rapidly and retired into the timber. The Boomerangs could give almost a ball to ball description of the movements of Japanese in threes and fours on the spur. After directing mortar fire to the ridge the aircraft strafed it while Captain Connor’s63 company moved forward to attack along the open ridge. Progress was slow and the attack costly because the enemy, on the steep ridge above, could throw down grenades on the attackers. During the morning Colonel Robson of the 2/31st Battalion arrived and carried with him a report from the 2/33rd’s company on the 4100 Feature that the enemy could be seen on a ridge approximately North-west of Major MacDougal’s company. To MacDougal there appeared to be about a company dug in on this ridge – and a company could hold up a battalion in this precipitous country.

By midday Colonel Cotton realised that his attack was unsuccessful. His leading company had lost 3 men killed and 21 wounded including 2 officers. As soon as he received news of the 2/33rd’s unsuccessful attack Eather informed Vasey that any further attempt to capture this enemy feature without artillery support would be very costly. Vasey agreed and at 5.30 p.m. signalled Eather to “maintain contact” but not to become heavily engaged until he received artillery support. Late at night the 2/31st relieved the 2/33rd which prepared to return to Kaigulin.

Farther down the Ramu Major Laidlaw’s 2/2nd Commando Squadron – now the only remaining operational unit of Bena Force – was patrolling the Ramu Valley and the foothills with two troops from Kesawai on the right to the Sepu area on the left. The third troop (Captain McKenzie’s) had arrived in the Guiebi area on the extreme left flank on 6th October, leaving one section at Chimbu to continue patrolling the Mount Hagen plateau.64 McKenzie was ordered by Laidlaw to patrol across the Ramu,

to harass and raid the Japanese, and, if possible, to establish a position north of the Ramu. McKenzie sent two sections across the river under Lieutenant Rodd65 to remain there as a standing patrol and to prepare extensive diggings on the high ground in front of the Sepu crossing overlooking Glaligool.66 Laidlaw’s three troops soon found that the enemy had left all his positions from Kesawai to Usini and Glaligool, although there was a clash with a Japanese patrol on a razor-back ridge two miles west of Egoi on the 13th.

The changeover between the 2/27th and the 2/16th Battalions was a smooth affair. By 2 p.m. on the 14th the 2/16th reached the Johns’ Knoll area. Half an hour later Bishop sent Lieutenant Clampett’s company to occupy Shaggy Ridge, so named after Clampett’s nickname. This rugged feature dominating Guy’s Post had not previously been occupied but Bishop thought that Guy’s Post would be insecure unless he had at least a company on Shaggy Ridge. Soon after Clampett’s departure Bishop set out with the company which had had the task of finding and burying the enemy dead. The final estimate of enemy killed on the 12th was about 190. The battalion’s return journey was made in heavy rain and the Faria River was in flood, necessitating the formation of a human chain for the crossing. Even so, one of the signallers was swept away and drowned in the raging torrent.

East and west of the main Australian thrust – if such it could be called – there was evidence on the 14th that the Japanese intended to play a more passive role. There was minor contact only in the main area. To the east the 2/31st Battalion found that the enemy had left the powerful two-company position which had been holding up the 2/33rd and they occupied it. To the west a patrol of the 2/2nd Commando Squadron, led by Captain Turton, fought a spirited action with the Japanese four miles North-east of Kesawai. Having failed in their major thrust on 12th October the 78th Japanese Regiment seemed now content to pull farther back into the hills leaving outposts against the forward Australian positions.

After the vigorous fighting and anxious moments of the preceding days the 15th set the tempo for the succeeding days. Only on the eastern flank where Captain Jackson’s company of the 2/31st Battalion were following the trail of the retreating Japanese was there any contact. The trail led towards the Gurumbu area where three Japanese stragglers were killed during the day.

From Guy’s Post, which Vasey visited on the 16th, Clampett’s company was reconnoitring Shaggy Ridge. A patrol found a Japanese outpost wired with four strands of barbed wire to which were attached tins which would undoubtedly rattle as a warning on Green Pinnacle about 1,500

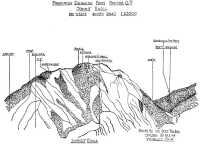

Reproduction of sketch in war diary of 2/16th Battalion for October 1943

yards up the ridge. Later another patrol heard movement behind the wire.

In the daily situation reports from now on appeared brief accounts of the work of the innumerable patrols sent out by the division. Sometimes “contact” was made and sometimes not. Clashes with the enemy were numerous, sudden and often bloody. If no enemy were encountered patrols were able to add to the division’s topographical knowledge by pointing out that such and such a track did not exist or such and such a mountain was in the wrong place. The “front”, such as it was, was now becoming more or less stabilised; the Japanese were clinging to Shaggy Ridge, Kankiryo Saddle and the area of the upper Faria River with several outposts in a wide semi-circle among the foothills protecting approaches from the west to Madang and Bogadjim. It was understandable that both sides wished to stabilise the position in the Ramu Valley for the full might of the Japanese counter-attack round Scarlet Beach was now being met.

The period was also one of administrative consolidation. Lieut-Colonel Tompson, the CRE, pressed on with the construction program in the Dumpu area, using the 2/5th and 2/6th Field Companies to build airstrips, roads, bridges, culverts and buildings. Tactical reconnaissance by aircraft, particularly along the Bogadjim Road, supplemented the topographical reports of patrols and helped the staff to prepare the basis for better maps. Realising the danger from malaria a determined effort was made to increase anti-malarial precautions.

Two patrols from the 2/31st Battalion on 17th October attempted to contact the 21st Brigade to their west. A small lightly-equipped patrol led by Major Hall67 set out from the battalion’s position at 8.30 a.m. north to a track junction three miles ahead. For three hours it followed this track which was about four to five feet wide, graded, well-used and with mud up to about a foot deep in patches. Generally it followed the contours round the headwaters of the Uria River and there were many signs of recent use by the Japanese. Some saddlery and a horse were found. Uphill and down and over several streams the patrol continued until, near Young’s Post, it met a patrol from the 2/14th under Lieutenant N. H. Young which had moved about three miles east along the Japanese track. Thus contact was at length made between the two brigades in the rugged country separating them and it was proved that along this track at least there were now no Japanese.

The other patrol – Captain McKenzie’s company – set out at 7.30 a.m. to try to contact the 2/16th. Along the track were signs of very recent use by the Japanese: bivouac positions, discarded gear, supply dumps, bridges destroyed within the last 48 hours and areas fouled by human excreta. After camping for the night the company made further attempts on the 18th to reach the 2/16th, but, although they must have been very close, they were unable to do so before they were due to return.68

Now that Vasey was sure that there was no substantial body of Japanese to the east of the 21st Brigade, he instructed Eather to bring the 2/31st out of the mountains to Dumpu. He intended eventually to move the 25th Brigade to the western flank but, because of supply difficulties, he told Eather that the brigade would stay in its present position for a time. To watch the immediate western flank Vasey sent two commando squadrons into the Kesawai area on the 18th – the 2/7th to Kesawai 1 and the 2/6th to Kesawai 2. The area was not suitable for landing strips. It would therefore be necessary to supply these western squadrons, either by pushing the jeep track through to the Kesawai area or by using native carriers.

It was imperative for the enemy to hold Shaggy Ridge which led directly to Kankiryo Saddle, the gateway to the Bogadjim Road. In accordance with Vasey’s suggestion Dougherty prepared for a limited advance and on the 17th reconnoitred the area in a Wirraway. That day Bishop also reconnoitred Green Pinnacle and prepared to attack this southernmost peak of Shaggy Ridge on the 20th with Clampett’s company, supported by Toms’. Bishop’s main concern was to discover whether the Japanese strongpost on the Pinnacle, deeply entrenched and wired, could be encircled. For three days from the 17th his patrols crept as near as they could, and early on the 20th, Captain Whyte,69 the FOO of the 54th Battery, directed the fire of his guns on to the Japanese position. Before the attack Clampett

was actually on the southern extremity of Shaggy Ridge and Toms was on the saddle between Bert’s Post and Shaggy Ridge.70

At midday Clampett reported that his men were within five yards of a four-strand barbed-wire fence; the Japanese position on the kunai-covered Pinnacle was about 30 yards away and overlooked his own troops. Between the enemy position and his men, there was a steep gully about 100 feet deep with precipitous slopes on both flanks. The Japanese had cut fire lanes through the kunai and were dug in and heavily bunkered from the cliff face on Clampett’s right flank round to his left. The original plan was for Clampett’s men to rush the position with artillery support. At this stage Lieutenant Crocker’s platoon was sitting quietly within 20 yards of the Japanese wire on the steep left slope of Shaggy Ridge. As the position was astride a narrow razor-back with almost sheer sides, an attack would probably have been suicidal. Bishop therefore decided to pause and to send a company round to the North-west to see whether the Japanese position could be outflanked. The artillery would, meanwhile, bombard the Pinnacle with the object of tricking the enemy into retiring temporarily to gain shelter. The artillery fire program for the night of the 21st–22nd, the 22nd, and the night of the 22nd–23rd was varied so that the rate of fire was never the same and the fire never at the same hours. However, it continued for an hour after first light to enable the platoon to get into position near the wire. If the platoon commander saw that the enemy had taken shelter north along the ridge he was to cut the wire and get on to the Pinnacle as quickly and quietly as possible.