Chapter 22: Torpy Sits on Sat

WHEN it came, the Japanese counter-attack on 22nd November was no surprise to the Australians. It will be recalled that on 3rd November General Katagiri had issued orders for the 80th Regiment to concentrate in the Sattelberg area and the 79th Regiment in the Nongora area with 20th Division Headquarters. General Wootten knew the general dispositions of these units and also that the II/238th Battalion (of the 41st Division) had recently arrived in the Gusika area. The 80th Regiment, withstanding the assault of the 26th Brigade, was incapable of launching a counter-attack. The 79th Regiment, however, was in a different situation and the battalion from the 238th Regiment was relatively fresh. The Australians estimated, fairly correctly, that there were about 6,200 Japanese front-line soldiers in the area: 2,400 from 79th Regiment, 2,000 from 80th Regiment, 800 from II and III Battalions, 26th Artillery Regiment, 1,000 from the 238th Regiment.

Documents captured by the 2/32nd Battalion soon confirmed Wootten’s deduction that attacks could be expected from the north, North-west and west. The Japanese encountered along the coast by patrols on the preceding days were the vanguard of the II/238th Battalion preparing to attack south “to annihilate the enemy north of the Song River”. A second and heavier attack by the main portion of the 79th Regiment was being launched over difficult country from the North-west. The third and smallest prong of the enemy attack, also consisting of elements of the 79th Regiment, crossed the Song near Stinker and was preparing to attack Scarlet Beach, once again from the west. The counter-attack would thus again fall on the 24th Brigade.

At Pabu small parties of Japanese continued to use the main track on the 22nd and were killed by the machine-gunners. Towards dusk, Japanese mortars and a 75-mm gun from Pino Hill began to shell Pabu, and in a few minutes 19 casualties were sustained by “A” Company whose commander, Captain Walker, was mortally wounded; while dressing his wounds, two stretcher bearers – Corporal Ridley1 and Private Langford2 – were killed. Two others, including a platoon commander, Lieutenant Lewis,3 were badly wounded and died later. As fast as possible the wounded were carried back to Major Dorney’s4 medical post, but when it became too dark to move the last three men Captain Kaye,5 the battalion

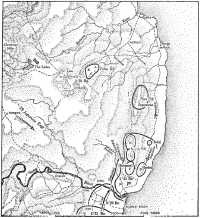

The Japanese counter-attack on the 24th Brigade, 22nd-23rd November

medical officer, came down the rough and slippery track and did what he could in pitch blackness to alleviate the suffering of the wounded, crawling round with a morphia syringe guided only by the sounds of the wounded.

“We were now an Australian island in a Japanese sea,” wrote one participant later.6

The presence of the 2/32nd Battalion on Pabu was a piercing thorn in the side of the enemy counter-attack. The continuous toll of casualties inflicted on his carrying parties, the damage done by the artillery, and the enemy’s surprise at finding Keley’s company so far west must undoubtedly have disconcerted him and upset his time-table. Mollard’s

telephone line had been cut, repaired and cut again several times. The repair team which went out on the 22nd to find the break was astounded to find what looked like a Japanese battalion staging in the exact area where the 2/32nd Battalion had been on the 17th.

In the coastal area north of the Song the 22nd was a day of close contact with the enemy for the men of Captain Gordon’s company of the 2/43rd Battalion. This company and Sergeant Pedder’s7 machine-gun platoon were stationed on the main coastal track about 1,100 yards north of the mouth of the Song and bore the brunt of the attack by the II/238th Battalion. To the west was a company on the jungle fringe south of the two companies on North Hill. Gordon had stationed Lieutenant Foley’s platoon north along the track near a waterfall where, on the 21st, one section had become separated from the platoon during a clash and had withdrawn to the company.

At first light on the 22nd the 2/43rd Battalion could hear the Japanese moving and yelling to one another just to the north of the company positions. By 8 a.m. Gordon reported about 15 Japanese trying to get by between his right flank and the sea, and Captain Richmond reported a few Japanese trying to infiltrate between his company and Gordon’s. Infiltration could not, of course, be prevented as the companies were not stretched out in a thin red line. Indeed, it was a relief to Brigadier Porter and Colonel Joshua to find that the Japanese were wasting their strength thus.

In whatever direction the company listened there seemed to be enemy sounds – talking and chopping trees mainly. Several Japanese were shot. It was not therefore surprising when, soon after 9 a.m., Gordon’s telephone line to headquarters was cut. For an hour and a half the Australians took pot shots at a few infiltrating Japanese. At 10.40 a.m. another of Foley’s sections reported in after having been separated from the platoon on the previous afternoon; and at 12.15 p.m. Foley and the remainder arrived, having spent the night hidden on high ground overlooking the enemy.

For the rest of the day there was a series of skirmishes with the Japanese foolishly dissipating their strength by sending in their attackers in ones and twos. For instance, at about 1 p.m. the anti-tank platoon (Warrant-Officer Bourne8) guarding battalion headquarters immediately north of the Song, saw a few Japanese on the right flank; a line party from the 2/28th Battalion killed four Japanese south of Gordon’s position; at 2 p.m. three Japanese were killed in a creek west of battalion headquarters; an hour later a prisoner was captured behind Gordon’s company.

This prisoner, from the II/238th Battalion, stated that the attack by two companies of his battalion was to be coordinated with artillery fire from Pino Hill. Actually a small Australian and Papuan patrol led by Lieutenant Cawthorne9 had been observing Pino Hill on the 21st and

22nd. At first light on the 22nd, as the patrol was about to move off, the Japanese artillery opened up and Cawthorne’s men were able to pinpoint roughly the positions of two guns, a machine-gun, and a mortar.

All day small bands of Japanese were seen on all sides and most were cut down by the defenders’ fire. By 5 p.m., when there seemed only a few odd Japanese in the area, Gordon decided to regain the initiative, and sent out patrols. One of these under Lieutenant Glover10 found about 10 Japanese slain by the Vickers. While the Australians searched the bodies two more Japanese leapt to their feet firing. Both were shot. When his patrols returned Gordon reported that there were no Japanese within 100 yards of his position to the front and to the right, although there were still a few on the left.

While the Japanese coastal attack was being shattered by the resolute defence of Gordon’s company the 79th Regiment was approaching the Australian positions from the Nongora area to the North-west. The Japanese did not use the main trail, which was being watched by the 20th Brigade, but advanced over country extremely difficult not only for movement but for control and coordination. Nevertheless, a Japanese attack coming from that direction, if powerful and determined enough, could break the Australian defences from North Hill to the Song. The 2/32nd Battalion had now been out of communication for 24 hours, and Brigadier Porter was arranging for it to be resupplied by air.

Porter was not happy about the plan for the defence of Scarlet Beach as he found it. It was based on a chain of section posts with little depth to the forward companies, and the defenders by cutting fields of fire had made it easy for the enemy to pinpoint the Australian positions. Porter could not do much, in the time and in the circumstances, to reorganise the defences, but he made some small adjustments, posted standing patrols forward of the perimeter, and had provided himself with a reserve of two companies, one from the 2/28th and one from the 2/32nd.

From dawn sporadic artillery fire falling over a large area came from the Pino Hill area; about 10 enemy planes bombed and strafed in midmorning, but wounded only one man. At 10.30 a.m. a listening post north of the Song exchanged shots with seven Japanese and then withdrew. As Stinker had been out of communication for over 24 hours Lieutenant Browning11 led out a patrol from the 2/28th to lay an alternative telephone line.

Porter decided that, as the 2/32nd needed reinforcing on Pabu, he could no longer afford the luxury of a two-company reserve. He therefore ordered the company of the 2/32nd in reserve forward from the Katika area to Pabu. Thus by 10.30 a.m. when the first Japanese were seen by the 2/28th’s listening post, Browning was on his way North-west

towards Stinker, Captain Lancaster’s12 company of the 2/32nd was across the Song and moving north towards the jeephead, and Hayashida’s spearhead was approaching the Australian positions from the North-west. Later in the morning both Browning and Lancaster skirmished with Japanese patrols. By 1 p.m. it began to appear that Lancaster’s company and the Japanese vanguard had crossed one another’s tracks, an easy thing to do in this wild country. Captain Coppock’s company of the 2/28th on the Song drove back a few Japanese, but the enemy managed to force the anti-tank platoon of the 2/43rd to the east of Coppock to withdraw slightly. This platoon had been under heavy fire during the day. On several occasions the enemy tried to break through but was driven back. In a weapon-pit on the right of the platoon’s position three men were doggedly defending an area where the enemy was persistently attempting infiltration when a mortar bomb fell into the pit. With the supreme courage which an emergency breeds, Private Grayson13 who was between his two companions placed his foot on the lethal bomb. He was grievously wounded, but the other two were able to continue the defence.

It was at this point that the movement of Lancaster’s company like the movement of Keley’s earlier, helped to disorganise the Japanese. At 1 p.m. Lancaster had just resumed his progress when, directly west of North Hill, the leading platoon (Lieutenant Smith14) saw the enemy in force near some huts. Artillery fire was brought down on them. The other two platoons were then passing through the 2/43rd’s anti-tank platoon. Lancaster sent Lieutenant North’s15 platoon to the left and Sergeant McCallum’s to the right to help the anti-tank platoon. As the Japanese advanced they were confined more and more towards the creek bed by pressure from both flanks. The RQMS of the 2/43rd Battalion, Crellin,16 from his pit on the bank of the creek killed four Japanese who stepped into the shallow water. McCallum’s men crept to within eight yards of the enemy’s position and killed five. Heavy enemy fire prevented any further advance but the platoon dug in and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy as he tried to reconnoitre. Lieutenant North’s platoon on the left also inflicted casualties but, despite two fierce attacks, was unable to dislodge the now strongly entrenched Japanese. The Japanese had used captured anti-tank mines as booby-traps, and one man was killed and four others, including North, were wounded, by them.

Lancaster then recalled Smith’s platoon which rejoined the company at 3 p.m. Joshua ordered that 200 2-inch mortar bombs be directed at the enemy now bottled up in the Surpine Valley. At 5.40 p.m. Smith’s platoon attacked and captured the whole area. Here the company dug in for the night, having blunted the main Japanese counter-attack. The

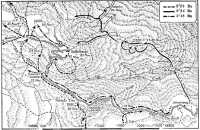

The capture of Sattelberg, 16th–25th November

enemy withdrew in the night from his uncomfortable position in the Surpine Valley leaving 43 dead. Lancaster’s arrival could not have been more fortunately timed.

It was fairly obvious to Wootten and Porter at the end of the 22nd that the Japanese counter-attack could be held and that it might already have been defeated. This counter-attack had nothing like the ferocity of the October one and seemed perhaps to be General Katagiri’s last attempt to turn the tide of battle. Like General Nakano he had contributed to his own defeat by the piecemeal nature of his attacks. Infiltration could never win a battle against the tactics employed by the Australians in the last year or more. This day 89 Japanese had been killed but the Australians lost only one killed and a few wounded.

Meanwhile, the advance had been resumed in the main battle area along the Sattelberg Road. Having captured Steeple Tree Hill, his immediate objective, Brigadier Whitehead, late on the 21st, issued orders for the capture of Sattelberg itself. The 2/48th Battalion accompanied by a troop of tanks would continue along the road; the 2/23rd would advance west along the road to the position subsequently known as Turn Off Corner and then north to the 3200 Feature, North-west of Sattelberg; the 2/24th would continue to advance from the 2200 Feature via the saddle towards Sattelberg.

The road to Sattelberg now became steeper, cutting into the side of the hill with high ground to left or right. With Captain Hill’s company leading, the 2/48th on the 22nd advanced north from Turn Off Corner without

opposition. The 2/23rd then moved past the corner to the west. After about 150 yards the leading men of the 2/48th came to what was at first thought to be the ford across Siki Creek but was later found to be another crossing farther south. Although the Japanese could be heard in the general area there was no opposition as the men carefully pushed forward for about another 100 yards to the real ford. At 3.25 p.m. they came to a landslide and four mines laid by the Japanese. Colonel Ainslie reported that it would be impossible to use the tanks further because of the landslide and the honeycomb of shell holes.

The 2/23rd Battalion had studied aerial photographs to determine the best route to the 3200 Feature after leaving the main road. Colonel Tucker decided that it might be possible to use a bypass route from the turn off a short distance to the west and then north parallel with and above the road. The 2/23rd left the main road and after about 300 yards struck the enemy in occupation of a ridge directly west of the 2/48th and running steeply up to the 3200 Feature. Soon after midday this position was captured after the leading company (Lieutenant Gray) had encircled it. It was now difficult for the 2/48th to determine exactly where the 2/23rd was, but by 2 p.m. it was thought to be approaching the crest of 3200. It was in fact not anywhere near the crest but was close to the 2/48th. Whitehead was disturbed and ordered the two battalions to maintain close contact so as to avoid shooting up one another. The diarist of the 2/48th wrote:

Once again identity was established by the officially-condemned “Ho, Ho” call. This was the second time on which it saved the battalions inflicting casualties on each other. It has come to stay. The troops are all wondering if it has any meaning in Japanese.

After gaining a little more ground and reaching a position overlooking the ford Gray’s company was pinned down by enemy fire. The two battalions withdrew slightly for the night to more favourable ground. The country ahead was New Guinea jungle at its worst. The battalion commanders considered that, unless some means of outflanking the Japanese defences could be found, a full-scale attack supported by artillery and tanks would be necessary.

In the late afternoon the Japanese artillery, in the course of its regular evening bombardment of headquarters areas, enjoyed a success similar to that on Pabu when several officers of the 2/32nd had been put out of action. Shells falling on the 2/48th Battalion headquarters inflicted 7 casualties, including 3 mortally wounded (the second-in-command, Major Batten, the adjutant, Captain Treloar,17 and the Pioneer officer, Lieutenant Butler18), and four wounded, including the medical officer, Captain Yeatman.19

The 2/24th Battalion continued its slow progress over very tough country on the 22nd. Colonel Gillespie sent Captain Harty’s company in an outflanking movement to the north and Captain McNamara’s to join Captain Bieri’s at the saddle connecting the 2200 Feature to Sattelberg. That morning Bieri was attacked from three sides. Gillespie’s plan was for Harty’s company to attack from the north while Bieri’s or McNamara’s companies cut the main track on the east and west sides of the saddle respectively. After the attack McNamara’s company would press on towards Sattelberg. At this stage Whitehead ordered Gillespie to make a more concerted attack and send both McNamara and Bieri towards the re-entrant on the west to block the track. Both companies worked round the ridge towards the track, and by 5.30 were in position near the track with a Japanese encampment in front on the high ground and another below in a gully. Further progress to the west was barred by a gorge.

By this time Harty was in position north of the Japanese originally encountered by Bieri. Harty attacked at 5.50 p.m. but the leading platoon was pinned down and so was the second which attempted an encirclement. Thus, by nightfall three companies of the 2/24th Battalion were more or less on the saddle and the Japanese on the 2200 Feature were in danger of being cut off. If only the promised tanks could arrive the progress of the 2/24th Battalion might be more spectacular.

Up the Sattelberg Road from the east day after day a procession of jeeps carried forward rations, water, ammunition and men. Down the road empty jeeps, or jeeps loaded with men hitch-hiking back trundled busily along. Now and then a jeep would come along the road at little more than walking pace carrying a bandaged and blanketed wounded man lying on a stretcher, or with a less seriously wounded man sitting in the seat beside the driver, grinning bravely, cigarette in mouth. Along the track on many days climbed parties of sweating reinforcements, loaded like packhorses. “Chuck it away, you’ll never carry all that up there,” advised the old hands.

Graders were at work on the road which, despite the fine weather since the opening of the Sattelberg campaign, still needed corduroying with tree trunks in the lower stretches where there was sticky black soil. Higher up where the coral was nearer the surface and the grey soil a mixture of black topsoil and coral, the road was firm and dry except where hidden springs soaked across it.

Up the road too from Jivevaneng went another lifeline – the native carriers, moving at a slow easy pace which made the gait of the soldiers look stiff and awkward. One native could carry three 3-inch mortar bombs or a case of rations. Cheerful but grave, expressionless but watchful, they had already proved many times over how vital was their role. A few would say “Good day” to the soldiers they passed, and receive a “Good day, George” in return.

Early on the 23rd Ainslie visited Tucker’s headquarters. Both went forward to Gray’s position whence Sattelberg could be seen. After studying the rugged jungle-clad ground towards Sattelberg they agreed that the

2/23rd should try to find a way round on the left flank and the 2/48th on the right. While the patrols were out mortars and machine-guns harassed the Japanese defences, and for the fifth successive day Allied aircraft attacked the general area – this time Sattelberg itself. A few Japanese planes also attacked between Kumawa and the Sattelberg Road causing the diarist of the 26th Brigade to comment on the “strange spectacle” offered to the men on the ground when Allied and enemy bombers and fighters, Allied supply planes for the 2/32nd Battalion, and two Boomerangs for artillery reconnaissance all appeared over the target area within ten minutes of each other. The artillery, increased since 20th November by the 2nd Mountain Battery, also kept up an intermittent bombardment.

There seemed little hope of finding a satisfactory route through the wild country on the right, and it was therefore a pleasant surprise when a patrol of the 2/48th penetrated to the hairpin bend without opposition although the enemy was heard digging in to the west. From here it seemed that the enemy might have neglected the precipitous country on the right on the grounds that it was too rugged for operations. It might just be possible therefore for a company or even the whole battalion to attack Sattelberg from the direction of Red Roof Hut spur. Wootten had suggested to Whitehead earlier in the day that the assault “seems like a two-company show for each battalion”. He visited Whitehead later that day to discuss the latest reports. The last hour of daylight was spent by the leading company commander, Captain Hill, in poring over aerial photographs and issuing the necessary warning orders for an advance and possible attack on the right.

The engineers of the 2/13th Field Company were given the task of preparing a track for tanks, to the left, known later as Spry Street (despite an instruction from New Guinea Force forbidding the bestowal of such names “without reference to GS Branch, NGF”).20 Believing that the 2200 Feature might be the site of an enemy base for a push to the east, particularly as large Japanese patrols and carrying parties had been seen moving thence from Sattelberg, Wootten decided that 2200 must be “absolutely freed”, and ordered the making of a track to carry tanks towards the feature. At the same time Whitehead ordered the withdrawal of Bieri’s and McNamara’s companies to enable the artillery and mortars to pound the Japanese positions without danger to their own men. At 12.15 p.m. Major Hordern, with a bulldozer, arrived at 2/24th Battalion headquarters, and arrangements were promptly made to bulldoze a route for tanks from Katika forward.

While the 26th Brigade was inching closer to Sattelberg the Japanese counter-attack against the 24th Brigade was finally shattered on the 23rd. On the coastal track Gordon’s company of the 2/43rd was fired on from

high ground about 250 yards to the North-west. Further attempts to infiltrate round the company’s left flank were broken up and the retreating Japanese were harassed with mortar fire. From the northern company of the 2/43rd Corporal Redman21 led a small patrol of Australians and Papuans early in the day to reconnoitre Pino Hill. In the mid-afternoon they came “hot-footing” back to the company lines reporting that the Japanese were in strength on Pino.

The 24th Brigade was still expecting a main enemy attack from the North-west as it had now, as usual, captured the Japanese operation orders. It soon became apparent, however, that the 79th Regiment was a spent force as far as this counter-attack was concerned. The Japanese had obviously become disorganised and disheartened by the Pabu surprise, the resolute Australian defence of the previous day, the vigorous Australian patrolling leading, as it did, to a constant hammering by artillery and mortars, and the supply difficulties created by the foul nature of the country.

Over 1,000 hastily dug foxholes were found in the areas near the company of the 2/43rd on the coast and the company of the 2/28th on the Song. Before the latter company there were 60 enemy dead, 112 rifles, 2 machine-guns, 2 mortars, one flame-thrower, bombs and ammunition. Japanese patrols were still in the area, however, for Papuans reported seeing about 40 of them 1,000 yards north of the 2/28th.

On Pabu the 2/32nd Battalion now had only two companies; but Lieutenant Keley’s, which had withdrawn to the jungle fringe after its sharp encounter on the evening of the 22nd, set out for Pabu at first light next morning. The respite of the night enabled Keley to bury the dead and construct two bush stretchers. The journey back to Pabu by an indirect and tortuous route took the company a day and a quarter; the two Papuans on the previous evening took three quarters of an hour. About 2 p.m. on the 23rd some 15 Japanese, who may have been tracking the company, approached from the rear but were quickly dispersed. The company was within 500 yards of Pabu when night fell and once more camped in the jungle.

The two companies on Pabu – Captain Thornton’s22 and Captain Davidson’s – and particularly the machine-gunners, went on killing Japanese carrying parties and reinforcements who continued to use the same track regardless of the fate of their comrades – further evidence of the primitive nature of Japanese communications and staff work. By the end of this day 82 had been killed round Pabu. As serious casualties had been inflicted on the Australians by enemy gunfire the previous night Mollard instructed his men to build log roofs over their slit trenches. Although the telephone line to this isolated position had been cut in several places and could

not at present be repaired, Mollard’s two wireless sets continued to work, and Captain Mollison was able to call for artillery support in an attempt to silence the three enemy field guns on Pino Hill. One opened up again at 8.55 a.m., but it soon seemed to be silenced by counter-battery fire. Actually the Japanese guns, which here as elsewhere would fire only about 20 shells in one bombardment, were cunningly hidden at the bottom of natural cliffs when not firing, and were almost impossible to hit except during their short bursts of activity.

On the 23rd Major Dorney became anxious about his wounded and stressed the importance of evacuating them. Porter ordered the 2/43rd to repair the line to Pabu from North Hill and guard the lines of communication, but realised that any such re-establishment of communication would be purely temporary while the Japanese occupied Pino Hill. After the 2/43rd Battalion re-established the telephone line at 6 p.m., Porter came on the line and told Mollard that an effort would soon be made to capture Pino. Early that day five Mitchells dropped supplies by parachute, but scattered them over a wide area including that occupied by the Japanese. Eighteen capsules were recovered, 14 of them from no-man’s land. Unfortunately none contained rations and the battalion was now very hungry. Worse still, the Japanese were found near the place whence the battalion had been drawing its water.

There was always a lighter side, however. Mortar bombs were dropped. The fuses were not in the bombs but were delivered in pieces ready for assembly, with a roneoed document directing the recipients to ensure that the fuses were not assembled except under the supervision of an ordnance officer. Only the shortage of batteries for the wireless sets prevented the adjutant from sending a signal requesting that an ordnance officer also be dropped. Sergeant Anderson23 assembled the fuses and tested the first bomb successfully with the aid of a forked stick and a long string. Using these bombs the mortarmen scored direct hits on a machine-gun post and an artillery observation post which had been overlooking Pabu. (After its relief the 2/32nd found that all the occupants of these two enemy posts had been killed.)

Round Sattelberg, meanwhile, Brigadier Whitehead’s three battalions were closing in. All knew that the kill would not be easy. If the Japanese defenders were alert the Australian attackers would have little chance of capturing the rugged and towering fortress without a protracted siege and much bombardment. As a result of splendid reconnaissance patrolling on 23rd November, however, it was decided that the 2/48th Battalion might be able to sneak a force across the headwaters of Siki Creek and attack Sattelberg up the escarpment from the South-east.

At first light on the 24th Hill’s company moved down into the deep ravine formed by Siki Creek on the east of the road. Brocksopp’s company was ready to follow in case Hill struck opposition. As everything

depended on surprise and silence, however, Hill’s men began their journey towards Sattelberg unsupported. “It was appreciated,” wrote the 2/48th’s diarist, “that if resistance was anything but light the almost impassable nature of the country would prevent the company taking the feature and that if the noise of the company advance was heard from Sattelberg itself, a handful of enemy could make it impossible for the company to climb the precipitous slopes.”

While Ainslie went back to discuss the day’s plan with Whitehead, Hill’s company advanced slowly and cautiously down to the Siki and up again on the other side trying to avoid the breaking of a branch or the dislodgment of a stone. The plan and subsequent activity of the 2/23rd Battalion out on the left flank was well summarised in a signal from brigade to the 2/48th:

Gray [“C” Company] is going to put on a Chinese attack [much noise] to confine the Nip. Lyne24 [“B” Company] is moving around the left flank and Tietyens25 [“D” Company] will be prepared to move along behind should the necessity arise.

To the north, along the bulldozer’s new track from Katika to the 2/24th Battalion on the 2200 Feature, a troop of tanks rumbled forward over the most difficult country they had yet encountered. With all this concentration of effort towards the one dominating objective it was not surprising that Whitehead, having been visited by the divisional commander yesterday, was visited by the corps commander today. General Berryman’s understanding of the historic moment and his instinct for being in at the kill were remarkable.

Despite all this power blocking up behind, the battle was yet dependent on the ears and eyes of Hill’s forward scout. Slowly the tortuous advance continued. The 26th Brigade began to send irritable signals to the 2/24th Battalion such as: “Perturbed at no information. Enemy are only 100 yards in front and a patrol has been out for 3 hours.” The truth was that the departure of the patrol had been delayed for a mortar shoot, and, as the 2/24th replied tersely, “although enemy only 100 yards ahead patrol had to go a long way round, otherwise it was suicide”. By 10.20 a.m. Colonel Gillespie reported that his first patrol thought that the enemy had “pulled out” from the top of 2200.

At the same time, on the left flank, Lieutenant Lyne’s company of the 2/23rd, carrying only essential gear but the largest possible amount of ammunition, crept as quietly as they could through rugged jungle to get behind the Japanese holding up Gray’s progress. At 11.10 a.m. Tucker signalled to brigade: “Lyne has got round on top of Gray – enemy between the two – going to deal with them now.”

Hill now began the stealthy climb up towards Sattelberg: Brocksopp’s and Isaksson’s companies then moved along the road to the hairpin bend and Brocksopp’s continued to the Siki. Out on the left the 2/48th

Battalion heard a sudden storm of fire. This began as Gray’s support fire for Lyne’s attack. It rapidly developed into something else, however, when Lyne at the end of his left flank encirclement ran into Japanese defences higher up the ridge. A hail of machine-gun fire from these positions and then from others to the west forced the company to withdraw. At 11.10 a.m., just as Tucker received Lyne’s signal saying that he was ready to attack, the telephone line was cut and a pandemonium of firing broke out from up the slopes of the 3200 Feature.

The fight was one of steps and stairs. Highest up the ridge were Japanese of the 80th Regiment, then came Lyne’s company, then more Japanese of the 80th Regiment, and finally Gray’s company. The noise of battle was only equalled by the depth of the confusion on the slopes of the 3200 Feature. That the position was baffling to all concerned was apparent from Tucker’s signal to brigade at 5 p.m.:

Japanese counter-attacked the company which moved in after Lyne moved out. Then Lyne moved in again. Position confused. Tietyens on good high ground on razor-back but has Nips in front of him and perhaps behind. Flanks secure.

Tietyens’ company had occupied a deserted Japanese position on the spur during the morning and thereafter he had steadily pushed forward. Lyne’s men were forced to return in small groups with 22 casualties. Soon after Lyne’s return the Japanese sharply attacked from higher up the ridge but the two companies drove them back.

This fight was over by the time Hill’s men approached their objective – the edge of the Sattelberg plateau. The ground from the Siki rose at an angle of never less than 45 degrees and, over the last stages, of about 60 degrees. So steep was the slope at the end that the men could not even crawl up unaided, but moved in single file and dragged one another up. It was not until a few minutes after 4 p.m. that the enemy became aware of the approach of the Australians. To those behind, anxiously awaiting news, the situation was obscure for the telephone line was severed one minute before the first Japanese were encountered.

Towards the top of the spur on which Red Roof Hut was situated were about 20 Japanese deeply entrenched in two-man pits with head cover of logs and earth and weapons firing through slits. This force was considered sufficient by the Japanese commander to guard against so unlikely a move as an attack from the South-east. As soon as these Japanese heard movement to the east they began firing in that general direction.

Hill now sought ways up the spur. Sergeant Daniels26 tried to move up the western slopes but failed because the Japanese rolled down grenades and fired machine-guns at short range. Another attempt was made from the south but failed for the same reason. Hill then ordered his third platoon commander, Sergeant Derrick,27 already a famous leader, to try from farther

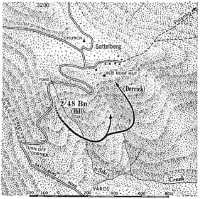

Sattelberg, 24th November

round on the right flank. Derrick’s platoon met the same precipitous country and was also held up by machine-gun fire and grenades. Soon after the firing started from this quarter a runner came back from Derrick and gave Hill a message: “I can’t get forward and the slopes are so steep I can’t hold the position for more than five minutes.”

Hill was by now convinced that he could not reach the objective or even hold his position. The company was spread around three sides of the feature and the enemy was able to prevent practically any movement. If the enemy ran out of grenades Hill believed they could use rocks effectively. “ ‘B’ Company has struck M.G’s and grenades on 3 sides 50 yards from the top,” signalled Ainslie to Whitehead at 5.50 p.m. “Will probably have to come back.” Whitehead replied ten minutes later: “Plan for tomorrow. 2/48 with tanks to go through Lyne’s company. 2/23 to hold firm.” With hope abandoned for an assault up Red Hut spur, Ainslie ordered Hill to withdraw. Within three minutes of the receipt of this order the left-hand platoon came back. Hill then ordered Derrick to withdraw under covering fire from the remaining platoon on the left. It was then 6.18 p.m.

Derrick climbed down towards Hill who clambered up to meet him. Derrick said: “I think we can get forward, we’ve done over about 5 posts.” Hill hesitated and explained his orders, but agreed when Derrick said, “Tell the CO I’m pinned down and can’t get out – give me another 20 minutes.”

Derrick had decided that the only possible way of approach was through an open kunai patch situated directly beneath the top of the cliff. During the advance from Jivevaneng this kunai patch, a third of the way down the steep face, and two big bomb scars near the bare summit, had ingrained themselves into the minds of the attackers. When his platoon was held up Derrick had clambered forward and with grenades had knocked out the post holding up the leading section (Corporal Everett’s28). He then led forward the second section (Lance-Corporal Connelly’s29) to attack

on the right and when it was halted by fire he scrambled ahead to within six yards of the enemy and threw grenade after grenade at the weapon-pits above him.

Now fortified by Hill’s agreement, Derrick led his platoon up the slope with the three sections following one another. It was about 6.45 p.m. Derrick and his men soon took two more posts. The platoon fired with Brens and Owens into the openings of these covered posts at 10 or 12 yards’ range and then one man – Derrick in one instance, Private “Slogger” Sutherland30 in the other – rushed forward and dropped a grenade in the slit of a post. The Japanese then ran from several other posts; two were shot scrambling down the slope to the right and the others – about eight – made off towards Sattelberg. Two of them threw grenades at their pursuers and wounded three men. Then Private Washbrook31 moved forward firing his Bren from the hip and killed both Japanese. Fifteen had been killed since the attack opened.

Derrick was now in the bush at the edge of the grass-covered plateau. In front of him the Japanese were in strength round some buildings 140 yards away and were firing with three machine-guns. Darkness was setting in. The platoon was only 18 strong. Derrick sent a runner back to Hill with this information, and soon the whole company was in position in Japanese weapon-pits along the fringe of the kunai. The Japanese fire died down about 7.15 p.m. Soon Brocksopp’s company which had been waiting at the Siki climbed up. The two companies spent the night in these positions about 150 yards from Sattelberg itself.32

For the commanders the situation had changed dramatically. One main problem was to supply the two companies clinging to the side of Sattelberg. In darkness men of battalion headquarters and Headquarters Company and others set out with water, ammunition and rations. Although they travelled only some 500 yards, the round journey took about eight hours. The new tank track – Spry Street – was ready; a third company was preparing to support the two forward companies in the final assault on the morrow. “There were very few men in the battalion who had any sleep that night,” wrote the battalion diarist.

After last light on the 24th the 2/24th reported that the position on the crest of the 2200 Feature seemed to have been “knocked out or evacuated”, and that it would be attacked early the next day. At first light on the 25th, brigade signalled to the 2/24th, “Important and urgent that tanks should get to 2/24th immediately. ... Necessary to put the pressure on from your side as early as possible.”

The morning was overcast. Registration by the artillery assisted by mortar smoke began at first light, but the close nature of the country

necessitated the separate registration of each gun.33 This took some time, and it was not till 8.25 a.m. that patrols from Hill’s company of the 2/48th could push forward to see if the enemy were still in the positions which they occupied at last light. Forty minutes later the patrols reported that these positions were unoccupied. At 9.15 a.m. the leading men of Hill’s company entered the abandoned shell of Sattelberg which had at one time been a health resort for the Finschhafen and other Lutheran Missions in New Guinea. Because of previous experience the withdrawal of the Japanese during the night was not altogether unexpected. At 10 a.m. the Australian flag, hoisted on to a tree by Derrick, was flying over Sattelberg. The battalion’s diarist commented:–

It was rather an inglorious end to the days of hard fighting where the difficult terrain made it possible for a very small force of the enemy to hold up a complete battalion. The advance of “B” Company had been made over heavily timbered country rising almost vertically at times and at no time less than 45 degrees. The Japanese might well be excused if he considered that line of approach impossible.

On the right the bulldozer and the troop of tanks crawled up towards the 2200 Feature, which the 2/24th Battalion at 10.30 a.m. found unoccupied; a patrol from the 2/24th during the afternoon found Palanko empty. On the left a company of the 2/48th occupied the 3200 Feature without opposition. Farther to the left patrols from the 2/23rd Battalion and the 2/4th Commando Squadron found Mararuo deserted and evidence (from wheel marks) that the Japanese had dragged a 75-mm gun towards Wareo. Another commando patrol found Moreng empty.

There was evidence that the Japanese were eating ferns and the core of bamboo. The state of their corpses and the many documents and diaries captured all stressed the Japanese supply difficulties. The prisoner captured by the 2/43rd on 22nd November said that even the main barge point of Nambariwa was supplied only by fishing boat, air dropping and submarine, as barges were too vulnerable to the air and naval attacks. The supply of Sattelberg from such bases as Nambariwa had recently become a nightmare for the Japanese commanders. The supplies which the Australians had seen dropping from aircraft over Sattelberg were insignificant.

“Every day just living on potatoes,” wrote a diarist of the 79th Regiment. Later he wrote: “Divided the section into two groups, one group for fighting and the other to obtain potatoes. Unfortunately none were available. On the way back

sighted a horse, killed it and roasted a portion of it. ... At present, our only wish is just to be able to see even a grain of rice.” One diarist of the 80th Regiment jubilantly wrote in mid-November: “Received rice ration for three days. ... It was like a gift from Heaven and everybody rejoiced. At night heard loud voices of the enemy. They are probably drinking whisky because they are a rich country and their trucks are able to bring up such desirable things – I certainly envy them.”34

Many Japanese dead were found-59 in front of the 2/24th Battalion alone. Two 75-mm guns were captured bringing the total of captured weapons during the Sattelberg campaign to two 75-mm guns, three 37-mm guns, 18 Woodpeckers and large numbers of light machine-guns, mortars, and rifles. The Australian casualties had not been excessive during the period 17th to 25th November – 49 killed and 118 wounded – considering the rugged nature of the country between Jivevaneng and Sattelberg. The 80th Regiment retreating towards Wareo was a broken force.

The Sattelberg campaign was the first continuous and fierce action against the Japanese by the 26th Brigade and its reactions as listed by one of the battalion diarists were interesting. “Many of the lads consider it to have been harder and more nerve-racking than any 10 days at Tobruk or El Alamein,” wrote this diarist. “Whether that is so or not is doubtful.” He then listed the main difficulties; the precipitous country and bamboo, the close contact, the lack of hot meals, the scarcity of water, the fitfulness of sleep, the necessity to carry everything on one’s back, and the enervating climate. “Against these matters,” he concluded, “must be weighed the comparative lack of enemy shelling or mortaring; the absence of the khamsin, etc. But whatever the answer one almost invariably gets the reply, ‘It’s not as bad as we were told’.”

The 26th Brigade knew how much of its triumph was due to the work of the 24th Brigade in the north. The courage and determination to advance displayed by the 26th was equalled by the courage and stubborn defence of the 24th. This brigade had repelled a fierce counter-attack during the critical days of the 26th Brigade’s advance, and by the sudden thrust to Pabu it had not only disorganised this counter-attack but had cut the enemy supply line to Wareo and Sattelberg and thus weakened the Japanese resistance there.

The Japanese counter-attack on the northern front had been broken by the 24th Brigade in one day – the 22nd – but the Japanese were still in evidence throughout the 24th Brigade’s area two days later and the men were anxiously expecting attack from any direction. From Pabu several large parties of Japanese were attacked along the main track. Unlike those

encountered inland by the 2/4th Commando Squadron these Japanese had plenty of rice and tinned rations. Again the 2/32nd’s machine-gunners mowed them down. Mollard himself has left the best description of the Japanese reaction to the fate of their comrades:

During all this fighting Japanese soldiers kept walking up and down the Bonga-Wareo track. They were supply parties, either carrying food and ammunition to Wareo, or returning for a new load. The most astounding thing was their complete lack of protective measures. They walked along the track as though they were strolling in a park back at home, despite the fact that corpses of their comrades were piled along on either side. Our Vickers gunners were almost hysterical with joy as these successive parties kept offering the machine-gunner’s dream target – a line of men one behind the other who could be fired on at ranges of less than 400 yards. As for ourselves, we were speechless with astonishment and kept thinking that each successive party must be the last. Why the Japanese infantry who were attacking us so relentlessly did not warn their comrades of the danger is something that none of us can answer.

One of Mollard’s most pressing problems was how to evacuate the wounded. The sight of so many wounded and dying in the centre of the perimeter had a depressing effect on the men, and it now became imperative that something should be done. Boomerangs had already dropped morphia and bandages right into the centre of the area and bush stretchers were ready. Now that there were three companies on Pabu, Porter decided that a risk should be taken and the wounded evacuated in the care of one of the companies. Thus Davidson’s company, guided by the line party from the 2/43rd Battalion, set out at 12.30 p.m. with twelve stretcher cases and the walking wounded. In an hour it travelled only about 400 yards as the jungle ahead had to be cleared for the stretchers. A platoon from the 2/43rd went out to meet the newcomers and helped them into their area, whence the wounded were rushed south in jeeps.

Meanwhile the 2/43rd was patrolling in search of Japanese. North of Gordon’s company patrols found hundreds of foxholes and about 40 dead Japanese, many wearing Australian steel helmets and carrying Australian grenades. In the afternoon of the 24th Papuan and Australian patrols encountered Japanese rearguards about 800 yards north. To the left patrols from the 2/28th and 2/15th Battalions met, with mutual surprise, near Stinker.

Four tanks arrived in the brigade area on the 24th when Porter and Colonel Scott, of the 2/32nd, who had now returned from hospital, reconnoitred Pino Hill from the North Hill area. As mentioned, Porter’s plan was to secure the supply line to Pabu by occupying Pino Hill. He decided to use the two companies of the 2/32nd Battalion not on Pabu, but, because of the fatigue of Davidson’s company, postponed the attack until the 26th.

Guided by a patrol of two Australians and six Papuans, two platoons of the 2/43rd set out towards Pabu at 9 a.m. on the 24th guarding the carrier line. The journey was a long and difficult one and late in the afternoon of the 25th the telephone line to the 2/32nd was found severed

again. Sergeant O’Riordan35 of the Papuan Battalion, two signallers (McMahon36 and Farrelly37) and two Papuans went forward to repair it. They were half way across a kunai patch when several light machine-guns and a Woodpecker opened up from about the 700 feet contour line. All were killed except one of the Papuans who managed to get back.38 The two platoons probed the area but because the Japanese were in some strength they withdrew after cutting the telephone lines of the Japanese who in turn cut theirs.

On Pabu itself on the 25th the 2/32nd experienced a quiet day for a change. A Boomerang at 10.20 a.m. dropped parcels containing batteries, and later four Mitchells dropped much-needed rations. Twenty-four parachutes were recovered this time. In the afternoon communication by Lucas lamp was established between Pabu and North Hill whence the 2/43rd Battalion signalled that the carrier train could not get through. At last light a 75-mm gun and mortars bombarded the 2/32nd Battalion for about twenty minutes. The tide was running strongly in the Australians’ favour, however, causing the diarist of the 2/32nd Battalion to rejoice: “Our spirits were given a lift when we heard that 2/48th Battalion had occupied Sattelberg.” The signal to the 2/32nd was, “Torpy sits on Sat.”39

Since 11th November the Australians had counted 553 more enemy dead, making a total of 1,848 since the Scarlet Beach landing. The Japanese loss of Sattelberg was a serious blow to their chances of holding the vital straits area between New Guinea and New Britain.

A Japanese NCO left the following message at Sattelberg addressed to “Australian soldiers”:–

We were not successful in our attack against enemy north of Song River due to heavy enemy fire power and subsequently had to withdraw. Our fire power is not strong enough. The Japanese army is really strong but at present we have no fire power and therefore have lost this battle. Just wait and see. Hundreds and thousands of Japanese soldier comrades have died and we will avenge them. We will definitely recapture Finschhafen and Lae. You Australian soldiers have been fooled by Roosevelt. Think it over. New Guinea is a stepping stone to Australia for Japan in the South Seas.

Despite this fine spirit which had been drilled into the Japanese soldiers, their commanders knew that the writing was indeed on the wall. General Adachi said later that after the loss of Sattelberg he realised that the Finschhafen area was lost. He said:–

However, local resistance in small pockets continued in order to keep the Australian troops in action and prevent the 9th Division from being free to make an attack on Cape Gloucester and Marcus Point (east of Gasmata) should resistance cease altogether. While delaying action was being fought at Finschhafen the 17th Division was being moved by land and sea from Rabaul to Cape Gloucester to resist the anticipated attack in that area.

Thus the capture of Sattelberg was a turning point in the New Guinea campaign. Until then the Japanese still hoped to stem the advance by the green-clad Australians, but now they began to look to the rear. And of all the causes of the Japanese defeat at Sattelberg and subsequent Japanese despondency, perhaps Pabu was one of the prime ones. General Adachi himself later described the effect of the loss of Pabu:

The most advantageous position for the launching of a successful counter-attack was given up; also Pabu provided excellent observation for artillery fire, and after its capture the position of the Japanese forces was precarious. Even after the failure of the attack on Scarlet Beach we still retained some hopes of recapturing Finschhafen, but at this point the idea was abandoned.

In November, Admiral Halsey’s forces in the Solomons and Admiral Nimitz’s in the Central Pacific had made further advances. In the Solomons the next objective was Bougainville, the largest island in the group and, politically, part of Australian New Guinea. On it were some 65,000 Japanese, one-third of them being naval men; but the Allied estimate was lower than this. The Japanese had been there since March and April 1942 and had established airfields and naval stations. They were deployed in four principal areas: Buka, Kieta, Buin and Mawaraka. Their XVII Army Headquarters was in the Buin area and the fighting formations included the 6th Division, 38th Independent Brigade and two naval landing forces each with a strength somewhere between that of a battalion and a brigade group. Few aircraft were now on the island, and in October the Japanese ceased sending surface ships to Bougainville.

Admiral Halsey decided to land on the northern shore of Empress Augusta Bay near Cape Torokina using the 3rd Marine Division. As a preliminary operation the 8th New Zealand Brigade group (Brigadier Row40) was given the task of taking the Treasury Islands south of Bougainville. It landed on 27th October with little opposition (there were fewer than 300 Japanese in these islands). Organised resistance ceased on the 2nd–3rd November; a total of 223 Japanese had been killed and 8 captured.

The Japanese expected a landing on Bougainville but the choice of Torokina surprised them, and only a company, with one field gun, was deployed in the area on 1st November. The gun sank four landing craft but, in spite of two air attacks, one of them by about 100 carrier aircraft, about 14,000 men were ashore and firmly established by the end of the day. A Japanese cruiser squadron was at Rabaul and, when news arrived that the American convoy was moving north, it was sent out to intercept but missed the American force and returned. On 1st November it was

sent out again, escorting 1,000 troops in destroyers. When aircraft were seen the troops were sent back but the escort continued and, on the night of the 2nd–3rd, the 4 Japanese cruisers and 6 destroyers were intercepted in Empress Augusta Bay by an American force of 4 cruisers and 8 destroyers. In the ensuing battle the Japanese lost a light cruiser and a destroyer; no American ship was sunk.

By 5th November the marines had established a beach-head extending inland about a mile, having lost only 78 killed and 104 wounded. By the 14th 33,000 men, including the 37th Division, were ashore. The Americans extended their perimeter, in the face of ineffective enemy attacks, until it was about 15 miles long and reached about five miles inland at its deepest point. On 15th December command was taken over by Major-General Griswold of XIV Corps and in December and January the Americal Division replaced the 3rd Marine.

The offensive in the Gilbert Islands proved a tougher one. It was the first of a series of large-scale amphibious operations that were to carry the Allied forces almost to Japan itself. The plan was to assault Makin and Tarawa with the V Marine Corps, one regimental team of the raw 27th Division landing on Makin and the 2nd Marine Division on Tarawa. Early in November a convoy carrying 35,000 troops escorted by a huge naval force began to converge on the Gilberts from Pearl Harbour and the New Hebrides. Makin was defended by only about 500 men mostly engineers and air force. On 20th November the attackers landed 6,400 men supported by battleships and carrier aircraft. At the first landing place the troops met only friendly natives but at the second there was some opposition. The attackers made slow progress but, by 23rd November, the little atoll had been secured. The Americans lost 64 killed, and, in enemy air and submarine attacks on the escorting fleet, lost an escort carrier, with 644 of its crew, and many aircraft.

Tarawa is an atoll with a radius of about 18 miles. The first American objective in the area was Betio, an island of about 290 acres where an airstrip was defended by about 3,500 Japanese including the 7th Sasebo Naval Landing Force who had built very strong defences and had many guns, ranging from 8-inch to 37-mm. On 20th November after a heavy naval and air bombardment, in which the naval ships shot 3,000 tons of projectiles, the first waves of Americans advanced towards the island in amphibious tractors designed to clamber over coral reefs or beaches. The bombardment had not been effective – far heavier ones were employed in later operations – and tractors and men were under severe fire during the landing. By midday the attackers had lost heavily and the situation was dangerous.

Most of the amphtracs had been knocked out; and owing to the tide’s refusal to rise no landing craft could float over the reef. Everything was stalled; reinforcements could not land and some 1,500 Marines were pinned down on the narrow beach under the coconut-log and coral-block wall, unable to advance or retreat ... the beach-head was almost nonexistent.41

By the end of the day about 5,000 men were ashore but 1,500 of them had been killed or wounded. A reinforcing battalion landed next day, came under heavy fire on the beach and soon had lost as many men as the two battalions already ashore had lost on the first day. About midday, however, the marines advanced, and captured three guns which had commanded the beach; reinforcements were landed. On the 22nd the marines held most of the island. By the afternoon of the 23rd the 3,500 defenders had been wiped out. In the four days 980 marines and 29 sailors were killed and 2,101 wounded.